|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

THE BEGINNING ERA OF CONCERN ABOUT NATURAL RESOURCES, 1873-1905

Following the devastating Civil War, the United States experienced tremendous change, especially in the West. American Indians, buffalo, trappers, and pioneers had already given way to homesteaders, miners, timber cutters, and other people bent on exploiting the land and resources of our quickly growing, resource-rich Nation. Herds of cattle and sheep soon spread over the grasslands of the Great Plains and Southwest.

Yet, even these uses were beginning to be replaced by homesteading farmers who broke the sod and sowed the grain on the prairies and plains. Hard-rock and hydraulic mining were a major industry in the Sierra Nevada, the Cascades, and the Rocky Mountain ranges. Mining extracted valuable minerals, but often severely eroded the land. Railroads had just finished linking the far West (California) with the rest of the Nation, and plans were being made to connect all of the West's major population centers by rail. Congress gave massive land grants to many railroads, especially along the northern tier of States (from Minnesota to Washington) to encourage the railroads to build rail lines connecting cites and towns, as well as spawn growth in the West. Timber companies, which had exhausted the virgin forests of the East, were quickly clearing the great pine forests of the Lake States (Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan) and were contemplating moving their operations to the South and far West.

|

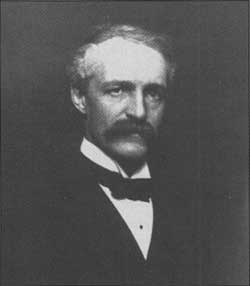

| "Log Stacks"-Michigan White Pine Before 1900 (USDA Forest Service) |

Acquisitiveness and exploitation were the spirit of the times, with little regard for the ethics of conservation or the needs of the future. The reaction to the abuse of the Nation's natural resources during this period gave rise to America's forestry and conservation movement.

The Visionaries

The beginning of America's concern about the conservation of land for the people can be traced back to George Perkins Marsh, who in 1864 wrote the book Man and Nature: Or Physical Geography as Modified by Human Action. This influential book drew on the past to illustrate how human actions had harmed the Earth—leading to the demise of earlier civilizations. Marsh wanted not only to warn his contemporaries against this fate, but also to initiate actions to prevent it. One measure that Marsh advocated was the protection of forests—yet few heeded his important message.

|

| Erosion-Effects of Deforestation in Colorado, 1915 (USDA Forest Service) |

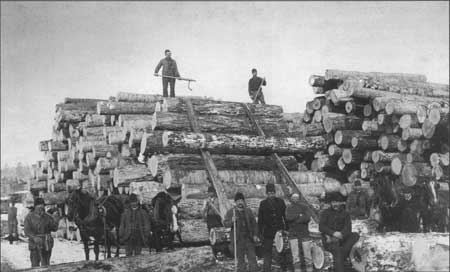

Two other influential persons in the early conservation movement were John Wesley Powell, who surveyed and reported on large portions of the West and its major rivers for the U.S. Geophysical and Geological Survey and F.V. Hayden, who made several important investigations of the Rocky Mountains—especially the Yellowstone area—for the U.S. Geological and Geographical Survey (predecessors of the U.S. Department of the Interior's Geological Survey). Several landscape photographers of the era—Timothy H. O'Sullivan, William Henry Jackson, and Carlton E. Watkins—were also important in generating concern about the marvelous and unusual features of the unpopulated West. The impressive images they produced informed Americans of the stark beauty and impressive majesty that abounded in the western mountains and valleys. These elements came together to protect the Yellowstone area in northwest Wyoming. Hayden's scientific reports of its remarkable features accompanied by O'Sullivan's spectacular photographs swayed Congress to establish Yellowstone National Park in 1872—the first such park in the world.

|

| Half Dome, Yosemite National Park (Carlton E. Watkins - Williams Collection) |

Others became convinced that the more ordinary forested areas, which were still in public ownership, also needed protection. This effort was spearheaded by Dr. Franklin B. Hough—a physician, historian, and statistician. He noticed that timber production in the East would fall off in some areas, while building up in others, which to him indicated that timber supplies in some areas of the United States were being exhausted. As a result of his study, Hough presented a paper, "On the Duty of Governments in the Preservation of Forests," to the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), held at Portland, Maine, in August 1873. The following day, AAAS prepared and approved a petition to Congress "on the importance of promoting the cultivation of timber and the preservation of forests." They sought congressional action, but no legislation was passed for 3 years.

|

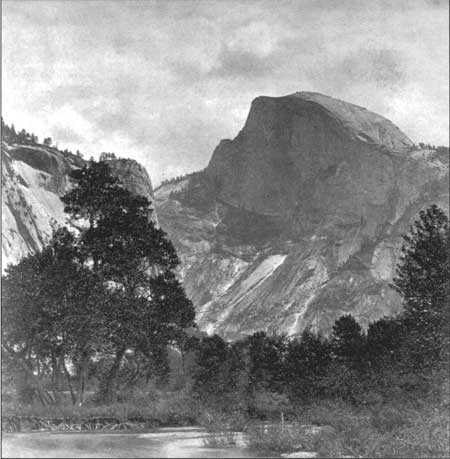

| Franklin B. Hough (USDA Forest Service) |

Federal Involvement in Forestry

On August 15, 1876, a rider (amendment) was attached to the free-seed clause of the Appropriations Act of 1876. This amendment provided $2,000 in funding for a person with "...approved attainment, who is practically well acquainted with methods of statistical inquery [sic], and who has evinced an intimate acquaintance with [forestry matters]...." This was the first Federal appropriation devoted to forestry. Dr. Hough received congressional appointment to undertake a study encompassing forest consumption, importation, exportation, national wants, probable supply for the future, the means of preservation and renewal, the influence of forests on climates, and forestry methods used in other countries. In 1878, his 650-page report, titled simply "Report on Forestry," so impressed the Commissioner (later the Secretary) of Agriculture and Congress that they authorized the printing of 25,000 copies.

Thus, a new governmental "organization" was formed that consisted solely of Dr. Hough, as the first forestry agent, and was placed under the supervision of the Commissioner of Agriculture. However, Hough as the forestry agent did not have any authority over timbered areas that remained in public domain. In 1881, the Department of Agriculture Division of Forestry was temporarily established to study and report on forestry matters in the United States and abroad; Hough was named its "Chief."

|

| Bernhard E. Fernow (USDA Forest Service) |

In Hough's 1882 report, he recommended "that the principal bodies of timber land still remaining the property of the government...be withdrawn from sale or grant." His idea was that this protected Federal timber would be cut under lease and that young timber growth would be protected for the future. In 1883, Nathaniel H. Egleston, who had also played an active role in the American Forestry Association, replaced Hough.

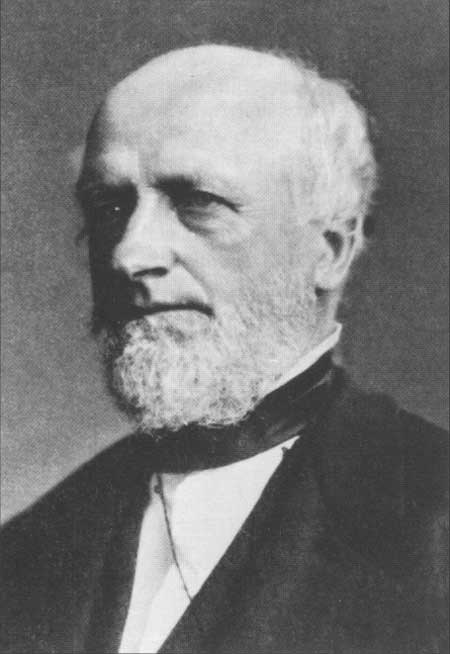

Egleston served uneventfully until the spring of 1886, when he was replaced by Dr. Bernhard E. Fernow, who was trained in forestry in his native Germany (there were no American forestry schools at the time). Fernow was a leader in the new field of forestry and a founder of the American Forestry Association. As Chief of the Division of Forestry, he brought professionalism to it. He set up scientific research programs and initiated cooperative forestry projects with the States, including the planting of trees on the Great Plains. On June 30, 1886, the Division was given permanent status as part of the Department of Agriculture. This provided the needed stability for the fledgling organization.

|

| Nathaniel H. Egleston (USDA Forest Service) |

In early 1889, Charles S. Sargent, professor of arboriculture at Harvard and editor of Garden and Forest, wrote an editorial for his magazine that took to heart Hough's 1882 recommendation to not permit the sale or grant of Government timberland. Sargent proposed three things: The temporary withdrawal of all public forest lands from sale or homesteading; use of the U.S. Army to protect these lands and forests; and Presidential appointment of a commission to report to Congress on a plan of administration and control of forested areas. As Gifford Pinchot pointed out, "the first suggestion was politically impossible, the second practically unworkable, but the third, in the end (some 7 years later), put Government forestry on the map."

In April of the same year, the law committee of the American Forestry Association, consisting of Fernow, Egleston and Edward Bowers of the U.S. Department of the Interior's General Land Office (GLO), met with President Benjamin Harrison. The committee recommended that the Nation adopt an efficient forestry policy. In 1890, after the President took no action on the matter, the American Forestry Association petitioned Congress to make forest reservations and provide a commission to administer them. Again, no noticeable action took place, but there was a strong groundswell to retain the forest-covered public domain for the people. The Boone and Crockett Club rallied around the issue of protecting Yellowstone National Park, as well as other forested areas in the West. This sportsmen's club was founded in 1887 with members such as Theodore Roosevelt, Gifford Pinchot, George Bird Grinnell, Henry Cabot Lodge, Henry L. Stimson, and many others. Their influence in national politics substantially helped the fledgling national forest movement in the early 1890's and the decades to follow.

The weight of the data and the recommendations of Hough, Fernow, Sargent, the Boone and Crockett Club, and the American Forestry Association led to the genesis of the National Forest System as we know it today. In the early 1890's it was apparent to many that the remaining forests represented a great, but vulnerable, national asset that needed to be protected from unbridled despoliation for the sake of posterity.

|

| John Muir (USDA Forest Service) |

The Forest Reserve Act of 1891

In the spring of 1891, when Congress was debating the issue of land frauds (the illegal purchase or deceit in the homesteading of Federal land) related to the Timber-Culture Act of 1873 and several other homestead laws, a rider was attached to a bill to revise a series of land laws. This small, one-sentence amendment (Section 24) allowed the President to establish forest reserves from public domain land:

SECTION 24—The President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, in any state or territory having public land bearing forests, in any part of the public lands, wholly or in part covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations; and the President shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservations and the limits thereof.

Since referred to as the "Creative Act" or the Forest Reserve Act of March 3, 1891, it was used by President Harrison on March 30th of the same year to set aside the first forest reserve—the Yellowstone Park Timberland Reserve (now part of the Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests in Wyoming). By the end of Harrison's term as President in the spring of 1893, he had created 15 forest reserves containing 13 million acres. These forest reserves were the White River Plateau, Pikes Peak, Plum Creek, South Platte, and Battlement Mesa all in Colorado; the Grand Canyon in Arizona; the San Gabriel, Sierra, Trabuco Canyon, and San Bernardino in California; the Bull Run in Oregon; Pacific in Washington; and the Afognak Forest and Fish Culture Reserve in Alaska.

On September 28, 1893, his successor, President Grover Cleveland, added two forest reserves—the huge Cascade Range Forest Reserve and tiny Ashland Forest Reserve—totaling 5 million acres—in Oregon. Cleveland did not add any more forest reserves for almost 4 years, until Congress was willing to pass legislation to allow for the management of the public forests.

The National Forest Commission of 1896

Meanwhile, there were efforts in Congress to change the procedure for establishing Federal forest reserves. In the summer of 1896, the National Forest Commission, the brainchild of the National Academy of Sciences, was funded by Congress. The commission, which consisted of Charles Sargent (chair), Henry L. Abbot, William H. Brewer, Alexander Agassiz, Arnold Hague, Gifford Pinchot (secretary), and Wolcott Gibbs (member ex-officio) traveled throughout the West touring existing forest reserves and areas where new reserves were proposed. John Muir and Henry S. Graves accompanied the commission on parts of their investigations. Although members of the commission disagreed with one another much of the time, they did agree on the need for Mt. Rainier and Grand Canyon National Parks and on a number of new forest reserves.

On February 22, 1897, President Cleveland, as a result of the Commission's recommendations, proclaimed 13 new forest reserves in the West, known thereafter as the "Washington's Birthday Reserves." The following forest reserves were established: San Jacinto and Stanislaus in California; Uintah in Utah; Mt. Rainier (renamed from Pacific and enlarged) and Olympic in Washington; Bitter Root, Lewis and Clarke, and Flathead in Montana; Black Hills in South Dakota; Priest River in Idaho; and the Teton and Big Horn in Wyoming. The furor of opposition to these forest reserves was unprecedented, and the outcry resulted in Congress passing certain amendments to the 1897 Sundry Civil Appropriations bill.

|

JOHN MUIR John Muir (1838-1914) left his native Scotland in 1849 to start a new life on the Wisconsin frontier. He attended the University of Wisconsin in his mid-twenties. After recovering from a serious accident to his eyes, he felt compelled to undertake a 5-month, 1,000-mile walk from Indiana to the tip of Florida. The following year, Muir voyaged to California, living at times in the wondrous Yosemite Valley, where he studied botany and the geology of the new State park. Muir was a strong advocate of the need to preserve the public forests and prohibit sheep grazing in the alpine meadows. He married in 1880, settling in Martinez, California, where he became a successful farmer. Returning to his work as an advocate for wilderness and forest preservation, he wrote many articles about the need to transfer Yosemite back to the Federal Government and rename it as a national park. The effort was successful in 1890. Two years later he helped to organize and become the first president of the Sierra Club. The club gained national recognition for its efforts to reserve and preserve scenic and forest areas first in California then across the Nation. Muir lost his last major battle, when, in 1913, Congress authorized the Hetch Hetchy reservoir in the valley adjacent to Yosemite Valley. Both were part of the Yosemite National Park, but forces from San Francisco, especially after the 1906 earthquake, were successful in having a dam built to supply clean water and power to the city. Muir died 2 years before the dam was constructed. His efforts at trying to have the national forests be more like national parks were countered by Gifford Pinchot with the notion that forests were to be used, while parks were to be preserved. Their disagreement was especially evident over grazing in the forest reserves. Muir did not want any; Pinchot felt that restricting grazing would be better than no grazing or unrestricted grazing. Both men were part of the 1896 National Forest Commission, which traveled through the West looking at existing and potential forest reserves. Despite their differences over sheep grazing and eventually Hetch Hetchy, they remained friends and often wrote to each other about their wonderful experiences together in the western mountains. Muir was an eloquent spokesperson for the preservation movement in the late 1800's and early 1900's. Even today his name evokes a deeply felt admiration and resolve that characterizes many environmental organizations. He wrote many articles for national publication, as well as several books including: The Mountains of California (1894), Our National Parks (1901), and My First Summer in the Sierra (1911). His writings addressed many controversial issues, including the notion that the Earth and its resources had been made for people to use up for the benefits of society. Muir argued that all living things were equally important parts of the land and that animals and plants have as much right to live and survive as people. Unlike many of the nature writers of his time. Muir tended to write about the environment through his own experiences. In an 1897 article for the Atlantic Monthly, Muir wrote: Any fool can destroy trees. They cannot run away; and if they could, they would still be destroyed—chased and hunted down as long as fun or a dollar could be got out of their bark hides...God has cared for these trees, saved them...but he cannot save them from fools—only Uncle Sam can do that. |

The Organic Act of 1897

On June 4, 1897, President William McKinley signed the Sundry Act. One of the amendments, the so-called "Pettigrew Amendment" (later referred to as the "Organic Act") provided that any new reserves would have to meet the criteria of forest protection, watershed protection, and timber production, thus providing the charter for managing the forest reserves, later called national forests, for more than 75 years. The act also suspended the "Washington's Birthday Reserves" for 9 months. This suspension was seen as a clever tactic to overcome western demands for totally eliminating the new forest reserves.

|

| GLO Division "R" Staff With Filibert Roth (L) and H.H. Jones (R) in Washington, DC (Library of Congress) |

Basically, the Organic Act allowed for the proper care, protection, and management of the new forest reserves and provided an organization to manage them. One of the first, if not the first, GLO employee was Gifford Pinchot, who was hired in the summer of 1897, as a special forestry agent to make further investigations of the forest reserves and recommend ways to manage them. The Department of the Interior's GLO was able to politically appoint superintendents in each State that had forest reserves. The following summer, 1898, saw the appointment of forest reserve supervisors and forest rangers to patrol the reserves.

|

| Bill Kreutzer - 1st GLO Forest Ranger, 1898 (USDA Forest Service) |

For 7 years, until 1905, forest reserve superintendents, supervisors, and rangers were appointed by the U.S. senators and the GLO from the affected States through the Department of the Interior rather than the Department of Agriculture, where all the forestry experts were located.

One of the first men appointed as a ranger was Frank N. Hammitt, a native of Denver, Colorado. He went to work in the summer of 1898 on the Yellowstone Park Timberland Reserve. Prior to his appointment with the GLO, he had been chief of the cowboys in Colonel William F. Cody's Wild West Show. Like many of the old-time GLO rangers, he was selected from the local area, but he had no knowledge of forestry. Yet he was a "rough-and-ready," practical man with great knowledge of the mountains. He stayed with rangering until his untimely death in the summer of 1903 after falling from a cliff on that reserve (now the Shoshone National Forest).

Meanwhile, back East at the national level, Bernhard Fernow performed his duties as Chief of the Division of Forestry with great distinction until April 15, 1898, when he resigned to become the Director of Cornell University's new forestry school. In the 25 years since Hough had presented his paper "On the Duty of Governments in the Preservation of Forests," the Nation had made significant progress in its movement from the frontier exploitation of the natural resources in the forested areas toward a policy of wise use and conservation.

|

| GLO Ranger on the Battlement Mesa Forest Reserve (USDA Forest Service) |

Fernow's replacement was Gifford Pinchot—America's first native-born professional forester. He had been schooled at Yale, then spent one summer in France and Germany studying forestry, gained experience in managing George Vanderbilt's Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, and became personally familiar with many of the new forest reserves through serving on the National Forest Commission. As the new and charismatic Chief of the Division of Forestry, Pinchot was in charge of 60 enthusiastic and dedicated employees. The headquarters was on the third floor and a small place in the attic of the Department of Agriculture building in Washington, DC. Pinchot changed his title "Chief" to "Forester," as there were "many chiefs in Washington, but only one forester." The title of "Forester" would remain in use until the 1930's.

|

| Forest Service Office in Washington, DC, 1901-1938 (USDA Forest Service) |

Pinchot was instrumental in obtaining full bureau status for the Division of Forestry. It became the Bureau of Forestry on March 2, 1901. In 1902, the Minnesota Forest Reserve was the first reserve created by Congress rather than by Presidential proclamation. Strong support by the Federation of Women's Clubs, which had 800,000 members in 1905, made the establishment of this forest reserve possible.

|

Gifford Pinchot—First Chief of the Forest Service, 1905-1910

Born on August 11, 1865, in Simsbury, Connecticut, Gifford Pinchot's New England family was made up of well-to-do, upper-class merchants, politicians, and landowners. He became involved with the National Forest Commission during the summer of 1896, as it traveled through the West to investigate forested areas for possible forest reserves. After the passage of the Organic Act of 1897, Pinchot was hired as a special forest agent with the General Land Office to report on the forest reserve management situation. The following summer, the Secretary of Agriculture invited him to become "Chief" of the Department of Agriculture's Division of Forestry. During the same period, the assassination of President McKinley in 1901 elevated his friend, Theodore Roosevelt, to the Presidency. Pinchot, with Roosevelt's willing approval, restructured and professionalized the management of the national forests, and greatly increased the area and number of these national treasures. In 1905, the management of the forest reserves was transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture and Pinchot's new Forest Service. In 1907, the forest reserves were renamed national forests. During Pinchot's era, the Forest Service and the national forests grew spectacularly. In 1905, there were 60 forest reserves covering 56 million acres; in 1910, there were 150 national forests covering 172 million acres. A pattern of effective organization and management was set during Pinchot's administration, and the "conservation" (an idea or theme he invented) of natural resources in the broad sense of wise use became a widely known concept and an accepted national goal. He was the primary founder of the Society of American Foresters, which first met at his home in Washington, DC, in 1900. He served with great distinction, motivating and providing leadership in the management of natural resources and the protection of the national forests. He was replaced in 1910 by Henry "Harry" S. Graves, Dean of Forestry at Yale. Gifford Pinchot wrote:

|

|

CARIBBEAN NATIONAL FOREST—FIRST IN THE WESTERN HEMISPHERE Adapted from Terry West's Centennial Mini-Histories of the Forest Service (1992) Fifteen years before President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed the first Federal forest reserve in the United States—the Yellowstone Forest Reserve in 1891—the Spanish Crown established reserves in Puerto Rico—then part of the Spanish Empire. The present Caribbean National Forest was formed from parts of these reserves. In the 19th century, increased population accelerated the rapid and widespread destruction in Puerto Rico's forest resources as trees were cleared for agricultural land—the economic base of the Nation. In 1816, colonial wars of independence and illegal timber trade led the island's Governor to restrict the sale of wood considered important for naval use. If military concerns led to the first conservation measures. In 1824, alarmed by the extent of deforestation that government-sponsored farming caused, Governor Miguel De La Torre issued Puerto Rico's first conservation law (circular 493)—a decree to stem harm to watersheds by planting trees. Puerto Rico remained under the dominion of Spain, which drafted the first comprehensive forest laws (1839) and set up forestry commissions that led to the first island-wide forest inventory in 1844. These inventories were conducted by ingenieros de montes (forest engineers) for the cuerpo de montes (forest corps), a department directed by the minister of public works and staffed by graduates of the Spanish forestry school. The Puerto Rican government's protection of the forest resources eroded in the next decades as Spain's ability to fund distant programs faded along with its economic status. Yet, in 1876 King Alfonso XII strove to ensure continued conservation of soils and water quality and flows in Puerto Rico by creating forest reserves. Because the forests were sources of roofing material, fuelwood, and sawtimber for people, regulations for extraction needed to be enforced by the servicio de monteros (forest service). As part of the settlement of the Spanish-American War of 1898, control of Puerto Rico passed to the United States. The Luquillo Forest Reserve was declared by Presidential proclamation in 1903. It became the Luquillo National Forest in 1907 when all the forest reserve names were changed to national forest names. (It has the distinction of being the only early forest reserve that was not established under authority of the 1891 act. Instead, the luquillo reserve was established under a 1902 act of Congress that gave the President 1 year to reserve "Crown lands" ceded to the United States by Spain in the Treaty of 1898.) In 1935, additional land was purchased and the Luquillo National Forest name was changed by executive order to become the Caribbean National Forest. In 1939, the Tropical Forest Experiment Station (now the International Institute of Tropical Forestry) was established in Puerto Rico. The Caribbean National Forest is the only tropical ecosystem in the National Forest System and serves as an international management model for tropical forests. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008