|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

THE EARLY FOREST SERVICE ORGANIZATION ERA, 1905-1910

During the early 20th century, the administration of the Federal forest reserves was divided between the supervisors and rangers of the GLO and the surveyors and mappers of the Geological Survey (USGS), both in the Department of the Interior. The forestry experts in the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Forestry were limited to technical forestry advice and assistance. Pinchot was the primary advocate (with the strong agreement of his friend President Theodore Roosevelt) of moving the responsibility of forest management away from the Department of the Interior.

The Establishment of the Forest Service in July 1905

On February 1, 1905, Pinchot was able to unify all Federal forest administration under the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Forestry. The Forest Service was finally established on July 1, 1905, replacing the Bureau of Forestry name. The creation of the Forest Service was followed by a change—the custom of GLO forest rangers gaining employment via political appointments ended, and selections were made through comprehensive field and written civil service examinations. These new standards helped create a workforce that was well-qualified, satisfied, and inspired by Pinchot's leadership.

|

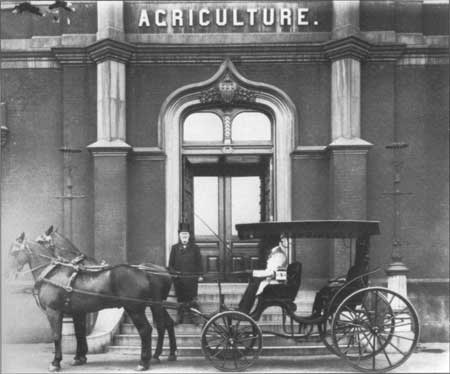

| Agriculture Secretary James Wilson at the Department of Agriculture Building in Washington, DC (USDA Forest Service) |

The Forest Service's early years were a period of pioneering in practical field forestry on the national forests. Forest rangers were directed from Washington, DC, and by local national forest supervisors. A Use Book, written in 1905 and updated yearly, contained all the Forest Service laws and regulations used by the rangers. Today of course, the laws require a book of 1,163 pages, while the regulations required to manage the national forests fill several bookshelves. The Forest Service manuals and handbooks are now available on the Forest Service's computer system.

|

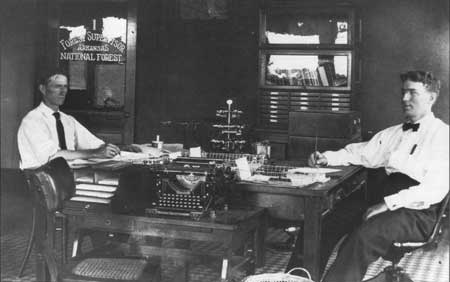

| Arkansas National Forest Supervisor's Office (USDA Forest Service) |

Much of the ranger's activity centered on mapping the national forests, providing trail access, administering sheep and cattle permits, and protecting the forests from wildfire, game poachers, timber and grazing trespass, and exploiters. In other words, they acted as custodians of the national forests during this "Stetson hat" era. An important and controversial land management decision was made to charge user fees for sheep and cattle grazing on national forests. A law was passed in 1906 to transfer 10 percent of the forest receipts (through grazing fees and some timber sales) to the States to support public roads and schools. Two years later, payments to the States were increased to 25 percent.

|

| Sheep on the Way to Summer Range on the Beaverhead National Forest (Montana) in 1945 (USDA Forest Service) |

|

FOREST RANGERS After the passage of the Organic Act of 1897, the General Land Office (GLO) established a forestry unit—later called Division "R" (Forestry)—to administer the new forest reserves. State superintendents were appointed first, then in the summer of 1898, more men were politically appointed as summer forest rangers, usually to fight forest fires. These appointments were made by the GLO State superintendents, the GLO in Washington, DC, or by a U.S. Senator, who was appointed by the State legislature. There were great temptations and opportunities for political favoritism and graft in these appointments, resulting in many GLO rangers being less than competent in managing the land and resources. There are many stories of these early GLO rangers not doing the jobs they were assigned, going home every day to work their farms or businesses, being unwilling or unable to undergo the rigors of living in the wilderness for long periods of time, or simply not having any knowledge of what they were doing. In a few cases, GLO rangers were actively involved in land frauds committed by their friends or in accepting money to "assist" homesteaders in obtaining forest land that was immediately sold to speculators or timber companies. In the spring of 1905, management of the forest reserves (later called national forests) was transferred from the Department of the Interior's GLO to the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Forestry. On July 1, 1905, the Forest Service name came into being. Gifford Pinchot, as the first Chief of the agency, was intent on building a force of forest rangers who were trained in or had good knowledge of practical forestry. He considered the words on the "Invalids Need Not Apply" poster (circa 1905) to be "a slap at the Land Office...and certainly well deserved." Pinchot was determined to transform the negative stigma of the GLO's region from 1897 through 1905 to a positive image of professional Forest Service employees, dedicated to "scientific forestry" and public service. When the forest reserves were turned over to the Forest Service, with a few exceptions, the GLO rangers quite Government service. The GLO rangers who did transfer to the new agency were very practical and greatly experienced men who helped form a cadre of highly talented rangers. Beginning in the summer of 1905, the new Forest Service required that applicants for the forest ranger position (now under Civil Service rules) take practical written and field examinations. The written test, although not highly technical, was quite challenging. Questions were asked to determine an applicant knowledge of basic ranching and livestock, forest conditions, lumbering, surveying, mapping, cabin construction, and so on. The field examination, held outdoors, was also quite basic. It required applicants to demonstrate practical skills such as how to saddle a horse and ride at a trot and gallop, how to pack a horse or mule, how to "throw" a diamond hitch, accurately pace the distance around a measured course and compute the area in acres, and take bearings with a compass and follow a straight line. In the field examination's early years, the applicants were also required to bring a rifle and pistol along with them to shoot accurately at a target. At some ranger examinations, the applicants were required to cook a meal, some ranger examinations, the applicants were required to cook a meal, then EAT it! The applicants, as well as the rangers themselves, were not furnished with equipment, horses or pack animals—they were required to have them for the test and for work, at their own expense. They pay was $60 per month. The forest ranger job changed little for several decades, with the practical forester serving the agency well. University-trained foresters, or "technical foresters," began to enter the agency after 1910, coming from the few colleges and universities offering degrees in forestry. By the 1920's, job specialization was becoming common. The changing needs of society after World War II prompted the agency to open the national forests to timber harvesting, which meant that the role of the general practical forester was outdated—university-trained specialists would take this agency into a new era. Today, agency employees are no longer required to take practical tests for employment and university-trained specialists are everywhere, but practical experience still "counts" highly in the Forest Service. |

|

FOREST SERVICE BADGES AND PATCHES Adapted from Frank Harmon's 1980 Article "What Should Foresters Wear?" in the Journal of Forest History and other sources As chief of the Bureau of Forestry, Gifford Pinchot began thinking about the need for a unique badge of authority for his agency employees even before the forest reserves were transferred from the Department of the Interior to Agriculture. When the shift finally took place early in 1905 and the bureau was designated as the Forest Service in the summer of the same year, Pinchot set about at once to get a new official badge for the forest rangers (the earlier General Land Office used a nickel-plated, round badge). For creation of the badge, Pinchot announced a contest among Washington Office employees. A highly varied collection of tree-related designs resulted, including scrolls, leaves, and maple seeds. Although the judges appreciated the employees' artistic merits, they were dissatisfied because none of the designs included generally recognized symbols of authority. The group agreed that the vast responsibilities of the new Forest Service required such a symbol to help assure public recognition of the agency and respect for its officers and their authority, both in Washington, DC, and in the field. A reliable symbol was especially needed for those men in the field who were charged with applying and enforcing Federal laws and regulations in the face of an often suspicious and hostile local populace. Edward T. Allen, one of the judges, strongly believed that a conventional shield was the best authority symbol. As it turned out, he and an associate, William C. Hodge, Jr., (who, like Allen, worked both in the Washington Office and in California between 1904 and 1906) came up with the design that became the official badge. In the spring of 1905, the two men were together in Allen's office or, perhaps, at a railroad depot in Missoula, Montana. Allen, who was attracted by the type of shield used by the Union Pacific Railroad, began tracing an outline of the shield (from a Union Pacific timetable) on a sheet of paper. He inserted the large letters U and S halfway from the top to the bottom of the shield, leaving a space between them. Hodge, looking on, was inspired to sketch a fir tree on a sheet of "roll-your-own" cigarette paper he took from his pocket. He then laid this between the U and S. The two men then quickly wrote "FOREST SERVICE" across the top and "DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE" across the bottom. The placement of the two names was probably dictated by available spaces. Whether this design had any influence on the soon-to-develop and still widely used but unofficial expression "U.S. Forest Service" is debatable. In any case, Pinchot and his assistant, Overton Price, were pleased with the design and called off a planned second contest. BRONZE BADGES A large bronze badge—about 3 inches in diameter, slightly convex with raised letters and tree—was issued to all field officers by July 1, 1905. Less than 2 years later, Pinchot issued an order on the wearing of the badge: "Hereafter the badge will be worn only by officers of the Washington Office when on inspection or administrative duty on the national forests, by inspectors, and by supervisors, rangers, and guards and other officers assigned to administrative duty under the supervisors." The present bronze badge, first issued in 1915, is smaller than the original. Badges for fire guards were nickel-plated bronze with the words "FOREST GUARD" across the top. "U.S." on the left of the tree, "F.S." on the right, and badge type was made with "FOREST GUARD" across the top, "U.S." left of the tree, "D.A." on the right, and "FOREST SERVICE" at the bottom. Neither of these Forest Guard badges had a raised edge around the border of the badge. The words were stamped into the surface and the tree was highly symmetrical. Another badge was issued, probably to forest guards or lookouts, that was the same as the regular Forest Service bronze badge, only nickel-plated. Around 1922, a smaller 1-inch bronze badge was authorized for uniform wear. This badge was a smaller version of the larger badge. It was used on dress uniforms until around 1972. Finally, a flat bronze badge has been recently issued. In addition to the three size variations and three forest guard variations, there were two other minor image changes: In 1920, the large letters U and S were lengthened, but the tree remained the same and, in 1938, Chief F.A. Silcox approved revising the tree image in the middle to make it longer/taller. The tree and root shapes on the shield also changed slightly—the tree became more symmetrical and the roots became slightly shorter. Since the late 1930's, there have been no additional changes to the image on the official badge. These changes were evident on both the badges and Forest Service shields everywhere. Forest Service law enforcement, however, has a different official badge. This unusual shield stylistically resembles the regular Forest Service patch in shape, but it has several variations: An additional point at the top of the badge, an eagle with wings outspread and head facing to the left sitting on the top, and a slightly "fatter" main body. The badge was designed by Agent Dixon from Region 8 in the 1970's. It is similar to other law enforcement badges of different agencies. At the top of the silver badge are the words "FOREST" and "SERVICE." The words are separated from the remaining words by a bar across the narrow part of the badge. The round USDA symbol is in the center, including the words "UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE" in the upper three-quarters of the circle. On each side of the round symbol are the highly stylized letters "U" on the left and "S" on the right. Immediately above these letters, between the letters and the word "SERVICE" are two five-pointed stars, one each on each side. At the bottom of the patch are the words "LAW ENFORCEMENT" on one line and the "& INVESTIGATIONS" on the second line, both inside a raised banner. CLOTH PATCHES Since the early 1960's, a cloth shoulder patch was authorized for wear on the left shoulder of official uniform shirts and jackets. The first authorized patch, issued in 1962, was flat on the bottom and sides, but rounded on the top. A curved overhead bar was added to designate which national forest of other office the wearer was from. In 1974, the current the Forest Service shield patch was authorized. The new patch, in the same shape as the badge, has the shield outlined in yellow, with the words and tree also in yellow against a green background. There are two variations: An older, smaller 2-inch Forest Service flat bottom patch, sometimes called the women's patch, which is identical to the larger 4-inch patch and the newer, smaller 2-inch Forest Service shield patch, also referred to as the women's uniform patch, which is identical to the larger 4-inch patch except that the word "DEPARTMENT" is abbreviated to "DEPT." and the word "AGRICULTURE" is abbreviated as "AGRIC." There were also two shoulder patches that are distinctly different from the other patches: A color variation—that of the Forest Service patch for winter snow ranger uniforms—orange border with black letters and tree on a white background and another snow ranger patch with a slightly smaller black-bordered shield with a larger orange shield outline. Apparently, the snow ranger patches were worn during the 1960's and 1970's. Several reasons for this unusual patch were: The patch could be worn on the outside of heavy winter clothing (the bronze badge could be underneath layers), it was highly visible against a dark green jacket, and when the ranger feel in the snow, the bronze badge would not be lost or cause injury. Another special patch is that of Forest Service law enforcement. This resembles the regular Forest Service patch in shape, size, and color with the following variations: At the top of the patch the words, in yellow thread, "FOREST" and "SERVICE" are on two lines. In the middle is a round symbol of the USDA in the center (outlined in yellow) and a larger circle with the words (in green) "DEPT. OF AGRICULTURE" circling the upper two-thirds of the yellow circle. On each side of the round symbol are the letters "U" on the left and "S" on the right. Immediately above these letters, between the letters and the top word "SERVICE" are two five-pointed stars - one on each side. At the bottom of the patch is the word "ENFORCEMENT" (in green) inside a yellow thread ribbon. A very different shoulder patch has been authorized in recent years for Forest Service volunteers. This off-white patch is somewhat like the older Forest Service uniform patches: About 3-1/4 inches tall and 2-1/4 inches wide, with a flat bottom and rounded top. The patch is outlined in an olive green thread. The off-white background has sewn with olive green thread the words "FOREST SERVICE" with the word "VOLUNTEER" underneath. Above the words is a shallow "V" in a pea-green color which has two olive green evergreen trees (without needles) having three branches on each side of the main stem. The trees overlay a pea-green sun. |

Land Frauds

|

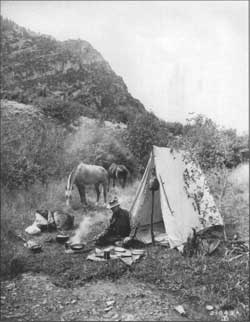

| Forest Ranger Camp in Logan Canyon, Cache National Forest (Utah) 1914 (USDA Forest Service) |

As some of the forest reserve boundaries had been hastily drawn, the Forest Homestead Act of June 11, 1906, allowed homesteading inside forest reserve boundaries on land that was considered primarily agricultural. However, there were many instances of land fraud on agricultural and State school lands. To meet the intent of the law, unscrupulous speculators would pay people to fraudulently claim that they were making a home on the land. After such "ownership," when the homesteaded land was transferred from the Federal Government, the new owners would immediately transfer that land's ownership to a land speculator, timber, or mining company. The terms "land-office business" and "land-office rush" came about during this period—reflecting the legitimate and not-so-legitimate people lining up to secure land claims at the local GLO's.

Federal investigations about land fraud were started in several States, and a few elected officials were indicted. The first successful fraud prosecutions, involving land speculators and various State, county and GLO employees, occurred in Oregon between 1905 and 1910. GLO head Binger Hermann resigned after being indicted, but was later found innocent; Oregon's Senator Mitchell was convicted. Many minor Federal and State officials spent time in jail over such wrong doings.

New Forest Reserves

In January 1907, there was considerable opposition to a Presidential proclamation that reserved thousands of acres of prime Douglas-fir timberlands in northern Washington State. The local press, chambers of commerce, and the Washington State congressional delegation protested that the reserve would cause undue hardship on residents by taking away homestead and "prime" agricultural lands (the land, in fact, was not agricultural, but heavily forested) as well as impeding the future development of the State. After considerable pressure, Pinchot and President Roosevelt relented, by saying that the reserve had been a "clerical error." Soon thereafter, Senator Charles W. Fulton of Oregon, who had been implicated in the land frauds in that State, introduced an amendment to the annual agricultural appropriations bill. This amendment, the Fulton Amendment, prohibited the President from creating any additional forest reserves in the six Western States of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado; took away the President's power to proclaim reserves, established under the Forest Reserve (Creative) Act of 1891; and gave Congress alone the authority to establish reserves. However, before this bill could be signed into law on March 7, 1907, Gifford Pinchot and the President came up with a plan.

|

| Forest Ranger Tying Equipment and Supplies on a Horse, Umpqua National Forest (Oregon), 1923 (USDA Forest Service) |

On the eve of the bill's signing, Chief Forester Pinchot and his assistant Arthur C. Ringland used a heavy blue pencil to draw many new forest reserves on maps. As soon a map was finished and a proclamation written, the President signed the paper to establish another forest reserve. On March 1st and 2nd, Roosevelt established 17 new or combined forest reserves containing over 16 million acres in these six Western States. These included the Bear Lodge in Wyoming; Las Animas and Ouray in Colorado; Little Rockies and Otter in Montana; Cabinet, Lewis & Clark, Palouse, and Port Neuf in Idaho; Colville and Rainier in Washington; and the Blue Mountains, Cascade, Coquille, Imnaha, Tillamook, and Umpqua in Oregon. These have been since referred to as the "Midnight Reserves." The President defended his actions by claiming that he had saved vast tracts of timber from falling into the hands of the "lumber syndicate." The Fulton amendment, at the suggestion of Pinchot, also changed the name of the "forest reserves" to "national forests" to make it clear that the forests were to be used and not preserved. The first national forests established east of the Mississippi River were the Ocala and Choctawhatchee National Forests in Florida in November 1908.

Decentralization

|

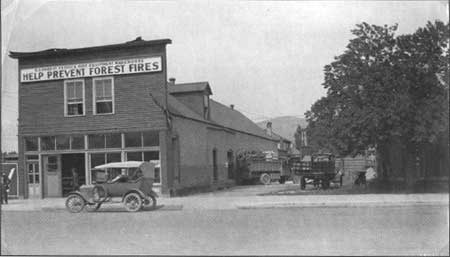

| Fire Equipment Warehouse in Missoula, Montana (USDA Forest Service) |

During the same month, six district offices were established in various sections of the country: Denver, Colorado; Ogden, Utah; Missoula, Montana; Albuquerque, New Mexico; San Francisco, California; and Portland, Oregon. They were part of a successful effort to decentralize decisionmaking from Washington, DC, to the districts, which were closer to and more familiar with local and region-wide problems. These new districts were staffed the following December and January by employees from the Washington Office and various supervisor's offices.

Decentralization was carried further with the creation of the Ogden (Utah) Supply Depot in 1909. This new depot was centrally located in the West and took advantage of the reduced shipping costs and shortened time that it took remote ranger outposts to receive supplies. To respond to local conditions, local national forest supervisors were given greater fiscal responsibilities. A seventh district, covering the administration of the national forests in Arkansas and Florida, was added in 1914. Alaska was made a separate district in 1921; then a new district was created in 1929 to cover the Eastern States. All the districts were renamed regional offices on May 1, 1930. (Region 7 was eliminated in 1966, leaving nine regions today)

Pinchot recognized the need to continue cooperation with the States and the private sector when in 1908 he organized the Division of State and Private Forestry (S&PF) within the Forest Service. The new division immediately began a cooperative study with the States to look at forest taxation. With the passage of the Weeks Act of 1911, the S&PF focused on working with State forestry and fire prevention associations—a cooperative relationship that continues to this day.

|

| Perry Davis on Early Speeder Looking for Railroad Fires, Pisgah National Forest (North Carolina), 1923 (USDA Forest Service) |

|

STATE AND PRIVATE FORESTRY The Forest Service and its predecessors have been involved with cooperative assistance to forest landowners since 1876. Several forest reserves were created to protect city water supplies (such as the Bull Run Timberland Reserve in 1892, Portland, Oregon's water supply). Since the early USDA Division of Forestry and later Bureau of Forestry did not directly manage the forest reserves, the main duty of USDA's forestry experts was to assist private landowners—including writing plans for millions of acres of private timber land. After 1905, when management of the forest reserves transferred to the USDA and the new Forest Service, the Department's foresters were quickly moved to field positions in the West. However providing "practical forestry" assistance to private landowners remained one of the agency's most important missions. In 1908, Gifford Pinchot recognized the Forest Service's obligation to the private sector when he formally established the Branch of State and Private Forestry (S&PF) in the Washington Office. This was the second "leg" of the agency—the other being the National Forest System. Cooperation was ongoing with the USDA's Bureau of Entolomology for pest control work and with the Bureau of Plant Industry on forest tree diseases. One of the new S&PF Division's first efforts was to aid States in the study of forest taxation. The agency published wholesale lumber price lists and supported lumber industry efforts to retain a tariff on lumber—with the understanding that these efforts were in the public interest. The lumber industry wanted the Forest Service to keep Federal timber off the market. With the vast "storehouse" of national forest timber (much of it inaccessible), selling the trees before they were needed in the housing market would reduce private timber prices and generally weaken the lumber industry. Yet the Forest Service continued to sell small timber tracts to ensure that the national forests were used, not set aside as parks. Chief Henry Graves noted that cooperation fell into three categories. Advising States in establishing forest policies, assisting them in surveying their forest resources (mainly timber), and finally helping forest owners with practical forestry problems. Section 2 of the Week's Act of 1911 codified Chief Graves' ideas. It authorized the Forest Service to work together with its State counterparts to fight fire on Federal, State or private land. (Previously, if a fire started on private or State land, the Forest Service could not help until the fire entered national forest land.) With the Weeks Act in place, it did not matter where the fire started or ended, main premise was to put it out and take care of the money later. The Weeks also authorized $10,000 in matching funds for State fire protection agencies' local fire prevention programs. The Clarke-McNary Act of 1924 greatly expanded the Weeks Act. The new act used cooperation and incentives to improve conditions on private for land. Fire and taxes were the primary components of the act—which allowed Federal, State, and private interests to work together. Section 3 the Clarke-McNary Act authorized the Forest Service to study tax laws their effect on forest land management. Because of concerns over the Nation's future wood supplies related to capital investments, activities, and even fire, the Forest Service assumed a responsibility in the tax matter. However, when Professor Fred R. Fairchild's 1935 report on tax matter failed to find any relationship between taxes and management, the report quickly fell into obscurity. Based on the Lea Act of 1940, which was designed to unify and coordinate efforts to control the white pine blister rust problem, irrespective of property boundaries, the Forest Pest Control Act of 1947 recognized a Federal responsibility for forest insect and disease protection on all ownerships. This law also offered technical and financial assistance to State forestry agencies to control insects and disease outbreaks in forested areas. The most famous cooperative effort, which continues to this day, the forest fire prevention program (see the Smokey Bear sidebar) during the first few months of 1942, cooperation between the Service, State foresters, and the Advertising Council continue to fire prevention program across the country. The Cooperative Forest Management Act of 1950 expanded the Forest Service's cooperative efforts of the post-war decade, provided for technical assistance, and extended management assistance to all classes of forest ownership. The Forest Service gave priority to assisting small forest landowners. In 1952, the Forest Service initiated a major field inventory, the Timber Resources Review (TRR), to analyze forest conditions on small forest landownerships. Although drafts of the report were circulated within 2 years, the forest products industry protected its results so much that the final report was not published until 1958! The TRR report found that forest practices would need to be intensified to meet future demands and that small ownerships were in the greatest need of assistance. Although the Forest Service made efforts to institute a program to remedy this situation, it proved to be too controversial and expensive. The Small Waterhsed Program (Public Law 566) in 1954 expanded the Forest Service's authority to include flood protection on farmland watersheds not exceeding 250,000 acres. The program covered flood prevention structures, upstream protection, and livestock control. The Forest Service worked closely with the United States Department of Agriculture's Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resources Conservation Service) and Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the States to implement such projects. The primary statutory authority for many of the current S&PF program activities is the Cooperative Forestry Assistance Act of 1978, as amended by the 1990 farm bill. In the past, the cooperative forestry program has been based on timber production, wood utilization, fire protection, and insect and disease control, but the emphasis is changing. Cooperative forestry is now involved in urban forestry to maintain trees in the inner cities. A new forest stewardship program seeks to help, both technically and financially, nonindustrial private forest owners to manage all the resources on their forest lands based on their own objectives. The rural development initiative is designed to help small communities diversify and strengthen their local economies. Regional foresters are responsible for the S&PF programs with the exception of the Northeastern Area, which is located in Newtown Square, Pennsylvania. The Northeastern Area is a reflection of the large number of nonindustrial private woodland owners who reside in the Northeastern States. |

Forest Service Research

|

| Regional Office, Southwest Region (Region 3) in Albuquerque, New Mexico, circa 1916 (USDA Forest Service) |

The first forest experiment station was established in 1908 at Fort Valley on the Coconino National Forest, Arizona, followed by other research stations in Colorado, Idaho, Washington, California, and Utah. Today, there are 20 research and experimental areas in the National Forest System.

Prior to 1910, the Forest Service undertook major efforts to evaluate sites for possible on-the-ground forest management camps called ranger stations. Ranger stations were established because of the need to have local control on many of the national forests. About the same time, many of the larger forests were divided into smaller, easier-to-manage national forests.

|

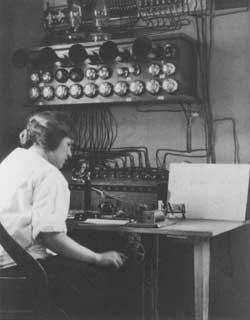

| Oakridge Ranger Station Telephone Operator, Cascade National Forest (Oregon) (USDA Forest Service) |

The height of the nationwide conservation movement was between 1907 and 1909, just before and after Theodore Roosevelt's National Conference of Governors met at the White House in May 1908 to consider America's natural resources. The President told conference attendees that "the conservation of natural resources is the most weighty question now before the people of the United States." The conference recommended that the President appoint a National Conservation Commission to "inquire into and advise him as to the condition of our natural resources." The commission returned with a three-volume report, which Roosevelt used in the effort to conserve the Nation's natural resources. Roosevelt left office in 1909 and was succeeded by William Howard Taft. Pinchot ran into problems with the new Taft Administration's Secretary of the Interior, Richard A. Ballinger, over coal leasing in Alaska. After months of national debate and personal attacks from both men, Taft fired Pinchot for insubordination in January of 1910. Pinchot was replaced as "Forester" by Henry Graves, his long time associate and personal friend.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008