|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

FOREST PROTECTION OR CUSTODIAL MANAGEMENT 1910-1933

The next 23 years was the Forest Service's era of forest protection through custodial management. Most important was a system for detecting and fighting forest fires. During the summer of 1910, when extremely dry conditions prevailed in the West, widespread fires flared in the Northwest and the northern Rocky Mountains, burning over 3 million acres in Idaho and Montana alone. Seventy-eight forest firefighters lost their lives nationwide trying to protect the national forests and remote communities from these devastating fires. Soon the Federal Government made firefighting funds available to combat such fires. As a result of the 1910 fires, cooperation between the various State foresters and the Forest Service became a driving force.

During this era, the Forest Service also began several important programs to better manage the national forests, including an extensive system of basic and applied research, timber management, recreation, and highways to better provide to the forests.

|

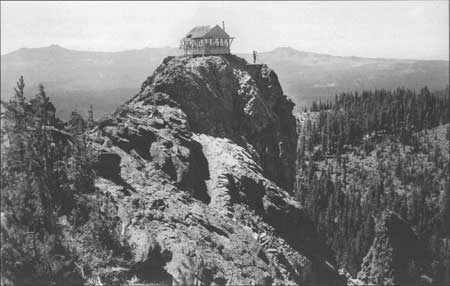

FOREST FIRES AND FIREFIGHTING Control of forest fires has long been considered as one of the most important aspects of forestry. Very large scale forest fires are primarily a North American phenomena, although many countries face serious forest and brush fire conditions. Early European-trained foresters, under whose tutorage Pinchot and others learned the basics of forestry, had not dealt with large fires potentially covering hundreds of thousands of acres in one fire. As a result, forest fires in the United States were much more serious than those they had ever encountered. Fire has long been used to clear land, change plant and tree species, sterilize land, maintain certain types of habitat, and for many other reasons. Indians are well-known to have used fire as a technique to maintain certain pieces of land or to improve habitats. Although early settlers often used fire in the same way as the Indians, major fires on public domain land were largely ignored and were often viewed as an opportunity to open forest land for grazing. If fires were fought at all, they were fought with shovels, brooms, rakes, fire lines, and backfires. When near farms, plows could be used to make fire lines in crops or near houses. Especially large fires raged in North America during the 1800's and early 1900's. The public was becoming slowly aware of fire's potential for life-threatening danger. The first very large fires were the Miramichi and Piscatquis fires of 1825 that burned around 3 million acres in Maine and New Brunswick. Other large and deadly fires were in the Lake States, including the Peshtigo fire of 1870 that covered over 1 million acres and took over 1,400 lives in Wisconsin. At the same time, fires were burning in Michigan, cindering about 2.5 million acres. Ten years later, these devastating Michigan fires were followed with another 1 million acres going up in smoke. In 1894, a large fire around Hinckley, Michigan, took the lives of 418 people. In 1903 and 1908, huge fires burned across parts of Maine to Upstate New York. In response, the first State fire organization in the East was established in Maine. Federal involvement in trying to control forest fires began in the late 1890's with the hiring of General Land Office rangers during the fire season. Largely ineffectual, the rangers were at least aware of many remote fires and could notify towns and settlers if a fire was heading their way. When the management of the forest reserves (now called national forests) were transferred to the new Forest Service in 1905, the agency took on the responsibility of creating professional standards for firefighting, including having more rangers and hiring local people to help put out fires. Of great importance to this cause were the devastating fires in the West. The first one was the 1902 Yacolt fire in southwestern Washington, which burned more than a million acres in Washington and Oregon and cost the lives of 38 people. A result of the fire was the formation of the Western Forestry and Conservation Association in 1909, led by the Edward T. Allen. In the previous year, Allen had been appointed as the first Forest Service Regional Forester in the Pacific Northwest Region. One year later, in the northern Rockies, some 3 million acres were burned in the "Big Blowup of 1910," and another 2 million acres in other areas. Within a year, Congress passed the Weeks Act of 1911 which, in part, allowed the Forest Service to cooperate with the various States in fire protection and firefighting. The Forest Service also began a program of fire research, which continues to this day. Lookout houses (many starting just as platforms atop trees) were used to locate fires from mountain tops during the fire season. The houses varied from low ground houses to very tall towers, sometimes over 100 feet tall. Just after World War I, the Forest Service contracted with the Army Air Service (Corps) to provide airplanes and pilots to spot fires from the air. This program worked successfully for more than 10 years until a comprehensive network of lookout houses and telephone systems were in place. Today, a computer network tracks every lightning strike and aerial patrols monitor for active fire sites after lightning storms. The few remaining lookouts still operating are valuable for locating human-caused fires. The Clarke-McNary Act of 1924 allowed the Forest Service to administer grants-in-aid to equal the amounts contributed to firefighting by the States and to set standards for firefighting and equipment. During the 1930's, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) program offered a change from just having Forest Service employees or hired people to fight fires. CCC enrollees were sent by the thousands to help fight fires throughout the West. The CCC's successfully tested and then used a 40-man (there were no women firefighters at this time) fire suppression crew. The CCC program also built and staffed thousands of lookout houses and towers across the country. Near the end of the 1930's, another new tactic was employed—having firefighters jump from airplanes to remote locations to put out fires before they become too large to fight. In 1939, smoke jumping was tested on the Okanogan National Forest in Washington. The first smoke jumping on a forest fire took place July 12, 1940, on the Martin Creek fire on the Nez Perce National Forest of Idaho. The two smokejumpers were Rufus Robinson and Earl Cooley. In 1935, the Forest Service developed the "10 a.m." policy that stipulated that a fire was to be contained and controlled by 10 a.m. following the report of a fire, or, failing that goal, controlled by 10 a.m. the next day, and so on. Faced with the necessity of controlling a fire overnight, the Forest Service was compelled to call out massive numbers of firefighters to try and control these blazes in the initial attack. A new division of forest fire research began operation in 1948, with three laboratories opening soon thereafter. On August 5, 1949, 13 smokejumpers lost their lives when a fire in Mann Gulch on Montana's Helena National Forest suddenly flared in high winds, leapt out of control, and enveloped the firefighters. This tragic event prompted the Forest Service to establish centers in Montana and California that were dedicated to developing and testing new firefighting equipment. By the mid-1950's, the Forest Service gradually assumed the primary responsibility for coordinating wildland and rural fire protection in the United States. During this time period, more than $200 million worth of World War II surplus equipment was passed to State and local cooperators. By 1956, air tankers, often military surplus B-17's filled with a borate mixture, and helicopters for transport were in use. By 1971, the Forest Service modified the 10 a.m. policy to handle fires in wildernesses by using a 10-acre policy as a guide for planning. Thus, some fires were allowed to increase in size to 10 acres only if they did not destroy or threaten to destroy private property or if they endangered life or property adjacent to the wilderness. Another so-called "let burn" policy came into being in the 1980's, it essentially allowed some fires, as in wilderness, to burn on the national forests depending on conditions. The 1988 fires in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem were devastating to large areas in and around the national park. In 1944, a forest fire claimed the lives of 10 hot shot crew firefighters when they tried to escape the fast moving South Canyon Fire on Storm King Mountain in Colorado. |

|

| Result of the 1910 Fires Along St. Joe River on the Coeur d'Alene National Forest (Idaho) (USDA Forest Service) |

|

Henry S. Graves—Second Chief, 1910-1920

Pinchot's close friend, Henry "Harry" Solon Graves born on May 3, 1871, in Marietta, Ohio, was also one of the seven original members of the Society of American Foresters. Graves, an eminent professional forester, served as the first professor and director of the newly founded Yale Forestry School. In 1910, he was selected to take over the reins of the 5-year-old Forest Service. His 10-year stint as Chief of the Forest Service was characterized by a stabilization of the national forests, the purchase of new national forests in the East, and the strengthening of the foundations of forestry by putting them on a more scientific basis. His great contribution was the successful launching of a national forest policy for the United States—a permanent and far-reaching achievement. During his tenure as Chief, the Forest Products Laboratory was established at Madison, Wisconsin; the Weeks Law of 1911 was enacted—allowing for Federal Government to purchase forest lands (mostly in the East); and the Research branch of the Forest Service was organized. Henry Graves wrote:

|

Forest Products Laboratory and Research

Chief of the Forest Service Henry Graves noted that with the forest practices of this era, loggers were typically leaving as much as 25 percent of the trees on the stump or ground and more than half of the trees that reached the mill were either discarded as waste products or burned on the site. In cooperation with Wisconsin State University (now the University of Wisconsin), the Forest Service established the Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) in 1910 at Madison, Wisconsin. The FPL was to be a "laboratory of practical research" that would study and test the physical properties of wood; develop and test wood preservation techniques; study methods to reduce logging waste; improve lumber production methods in sawmills and devise new uses for wood fiber; distribute wood product information to the public; and cooperate with the wood products industry. FPL research made utilization of forest products an important element in the greater use and production of wood from public and private forests.

The Weeks Act of 1911 allowed the Government to purchase important private watershed land on the headwaters of navigable streams, which may have been cut over, burned over, or farmed out. As a result, this act indirectly supported the creation of new national forests through land purchases in the Eastern United States where there was little public domain land left. It also provided cooperation with, and Federal matching funds for, State forest fire protection agencies. By 1920, more than 2 million acres of land had been purchased under the Weeks Act—by 1980 over 22 million acres in the East had been added to the National Forest System.

|

| Forest Products Laboratory, Madison, Wisconsin (USDA Forest Service) |

The Forest Service Research Branch, known earlier as the Office of Silvics, was established in 1915 to investigate better ways of managing the national forests, as well as to study the hundreds of tree species and to explore methods to reseed and replant forests. This period saw a great expansion of the number of national forest timber sales; the construction of numerous ranger stations, lookout, trails, and trail shelters; and the first use of telephones on national forests.

|

FOREST PRODUCTS LABORATORY— MADISON, WISCONSIN In 1907, McGarvey Cline, head of the Forest Service's wood use section, proposed that all wood product scientists be brought together under one roof. As a consequence, the University of Wisconsin constructed a special laboratory for its use in Madison, Wisconsin, and the Forest Products Laboratory (FPL) began operations on October 1, 1909, and was officially opened on June 4 of the next year. Scientific research on wood and wood products began in earnest, with FPL scientists receiving a large number of patents over the years. Some of the first work at FPL involved drying wood through a dry kiln process. Hundreds of species of wood were tested for their fiber strengths. A pulp and paper research unit was formed to study the mechanical and chemical from trees, and the development of chemicals used to stabilize and moisture-proof wood products. During World War I, the FPL was instrumental in efforts to produce lightweight, but very strong, airplanes. They tested the strengths of fuselages, wings, and propellers, and developed effective ways to use wood, cloth, and paint (dope) to strengthen the new airplane airframes. During World War I, FPL's workforce rose from fewer than 100 to about 450. Paper was in short supply during World War I, so FPL scientists began research on tree species not commonly used for paper production. In 1928, the McSweeney-McNary Act made special provisions for continuation of research at the FPL and, by 1931, the FPL had completed construction of a new laboratory building. In 1932, FPL gained notoriety as the place where the wooden ladder used in the Lindbergh child's kidnapping was analyzed. The advent of World War II caused the number of FPL employees to rise again, to around 700. They conducted research and development work on many wartime needs and uses, such as airplanes, ships, buildings, containers, paper, and plywood. FPL became the model for national laboratories around the world. After the war, the FPL began to shift emphasis from old-growth, high-quality wood, such as pine and Douglas-fir, to the lesser-used species and more efficient uses of existing timber supplies, including second and even third-growth timber. The private sector became active after the war, funding smaller laboratories to conduct research on wood products, manufacturing techniques, and consumers. Many of these small private laboratories conducted their research on proprietary products with the research results not released to the public. FPL's research findings are in the public domain. Today, FPL conducts basic research work on many wood-related topics, including wood fiber recycling and better utilization of wood products, while continuing the testing of wood fibers and better ways of manufacturing wood products and training wood technology researchers from all over the world. |

|

WEEKS ACT OF 1911 Adapted from Terry West's Floods, fires, and Forest Service foresters all contributed to the passage of the Weeks Act of 1911, which marked the shift from public land disposal to expansion of the public land base by purchase and was the origin of the eastern national forests. The role played by floods, wildfires, and foresters goes back to the beginnings of the conservation movement and professional forestry in the United States. The importance of forests in watershed protection, for example, was an early subject of concern among those who argued for forest reserves. The place of forest in moderating stream flow was unclear in the early stages of the forest conservation movement, but gained enough credence that "security favorable conditions of water flows" was defined as a primary function of the newly formed Federal forest reserves in the Forest Management (Organic) Act of 1897. It may have been the memory of the disastrous Johnstown (PA) flood in 1889 that helped dramatize the consequences of watershed deforestation to people in the East. Foresters, largely based in the USDA Forest Service, recognized the importance of forests in flood protection—the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did not. The Corps' idea of flood control was dams and levees. Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot felt that the Corps of Engineers' position undermined one of the key arguments for creating additional forest reserves. Most of the over 150 million acres of forest reserves established by 1907 were in the West. The issue of flood control became important to gain political support for purchase of lands for national forests in the East. Rain was important to irrigators in the arid West, and urban residents wanted pure drinking water, so these two groups supported watershed protection through creation of forest reserves. It was recreationists in the East, however, who sought creation of additional Federal forests—with supporters of the proposed White Mountain reserve of New England (Maine and New Hampshire, now the White Mountain National Forest established in 1918) working with the regional advocates of Appalachian reserves (who later managed to get a series of national parks for the area in the 1920's). Enlisted in the effort was Congressman John Weeks (of Massachusetts), who, in 1906, made a motion in Congress to authorize Federal purchase of private lands for the purpose of forest reserves. The notion of spending public money on recreation sites did not appeal to the powerful Speaker of the House, Joe Cannon, who declared "not one cent for scenery" in the debate against the proposal. In 1905, the American Forestry Association endorsed the proposal to establish eastern national forests through Federal purchase, and Congress's defeat of the bill led them and other advocates of forest reserves to shift their argument from nature preservation to utilitarian concerns over flood protection. In the meantime, a need for fire control offered a second reason for the shift of ownership of forest lands to the Federal Government. The lack of fire protection efforts on the part of the private sector and even States made it a national program for the new Forest Service, the reason being that when scientific forestry began in North America its practitioners regarded fire protection to be a fundamental mission of the forestry profession. With the massive western fires of 1910 accelerating the trend, U.S. public opinion gradually moved toward the forester's view of the need for wildfire control of forested lands. The 1910 fires in Idaho and Montana burned over 3 million acres and killed over 80 firefighters. Combating these fires cost the Forest Service more than 1 million dollars. Spurred by the costly fires, Chief Graves initiated a program or scientific research on fire control. Passage of the Weeks Act on March 1, 1911, added to the Forest Service's fire work. Section 2 of the Weeks Act authorized firefighting matching funds for State forest protection agencies that met Government (Forest Service) standards. This was the first time that Congress allowed direct funding of non-Federal programs, and since it was busy developing cooperative fire control programs, the action greatly increased the task of the agency's recently formed (1908) State and Private Forestry Branch. Passage of the Weeks Act led to the Federal purchase of forest lands in the headwaters of navigable streams—expanding the National Forest System east of the Great Plains—a region of scant public domain. The Pisgah National Forest, the first national forest made up almost entirely of purchased private land, was established on October 17, 1916. The core portion of the new forests came from the privately owned Biltmore Forest—once managed by Gifford Pinchot. Land purchases for the Pisgah began in 1911, soon after the passage of the Weeks Act. By 1920, the end of the Graves administration, more than 2 million acres had been purchased; by 1980, purchases and donations based on the Weeks Act added over 22 million acres to the National Forest System. |

|

RESEARCH ON THE NATIONAL FORESTS Adapted from Terry West's 1990 Conference Paper Gifford Pinchot found it necessary in his first year (1898) as Chief of the Division of Forestry to establish a Section of Special Investigations (Research). By 1902, it was an agency division directed by Raphael Zon with 55 employees and accounting for one-third of the $185,000 budget. Zon proposed creation of forest experiment stations to decentralize research. The first area experiment station was established in 1908 at Fort Valley on the Arizona Territory's Coconino National Forest. These stations were Spartan operations designed to serve the needs of the local forest. One exception, however, was the Wagon Wheel Gap Watershed Study in Colorado, a cooperative project with the U.S. Weather Bureau to study the effect timber removal on water yields. In 1909, the second pioneer, Carols Bates, chose a remote site near the Rio Grande National Forest in Colorado for the Nation's first controlled experiments on forest-streamflow relations. Little is known of the hydrology of mountain watersheds until Bates' innovative research on how water moves through soil to sustain streams during rainless periods. Research's importance to forest management was formalized in 1915 with the creation of a Branch of Research in the Forester's (Washington) Office, with future Chief Earle Clapp in charge. It was felt that Research needed to be based out of a central office to ensure project planning on a national scale. This move made Research co-equal to the administrative side of the agency. Forest Service Research's original function was to gather dendrological and other data needed to manage the national forests. Independence from administrative duties allowed scientists to dedicate more time to research projects, but required the agency to develop a staff of specialists to transfer Research's technical information into field operations. Range research began in the USDA Department of Botany (1868-1901) and later in the Division of Agrostology: USDA's Division of Forestry became interested in range research in the summer of 1897 when Frederick Coville carried out the first range investigation on the impact of grazing on the forest reserves of the Oregon Cascades. This important study, the Coville Report (Division of Forestry Bulletin No. 15), was published in 1898 and resulted in Oregon's forest reserves being reopened to grazing. In 1907, James Jardine and Arthur Sampson conducted studies to determine the grazing capacity of Oregon's Wallowa National Forest. The bulk of range research, whoever, took place in the Intermountain Region at the Great Basin Experiment Station on Utah's Manti National Forest. By the 1920's, the Forest Service had 12 regional research stations with branch field (experimental) stations. Congress passed the McSweeney-McNary Research Act on May 22, 1928, which legitimatized the experiment stations, authorized broad-scale forest research, and provided appropriations. One impetus for forestry research in the United States was the limited applicability of European models to the management of U.S. forests, especially in dealing with the threat that fire posed. European forests simply did not experience the fire danger that U.S. forests did. The Forest Service began its research program with Chief Greeley writing that "firefighting is a matter of scientific management just as much as silviculture or range improvement." California District Forester Coert DuBois directed tests of light burning and fire planning and, in 1914, published his classic Systematic Fire Protection in California. By 1921, the Forest Service dedicated the Missoula, Montana, headquarters of the Priest River Forest Experiment Station to fire research. Research head Earle Clapp personally arranged for Harry Gisborne to be assigned to the station. From then until his death during a fire inspection trip of the Mann Gulch fire in 1949, Gisborne worked on fire research. Fire research during the 1920's was subordinate to administration—research focused on fire control rather than fire itself. Under this pragmatic approach, fire researchers were expected to leave their field plots and statistical compilations for the fireline. Fire research in the Southern United States focused on the fire rather than fire control, since "light burning" (human-set fires) was still an industrial practice. Thus, research on fire and wildlife management and longleaf pine silviculture was carried on in the Southern Region. When the Forest Service created a separate Division of Fire Research in 1948, one objective was to have a national fire research agenda supervised by forester-engineers and forest-economists. Although research funding declined in the 1930's, this was an era when facilities expanded. Programs such as the Civilian Conservation Corps and Works Progress Administration provided labor and materials to construct research facilities. By 1935, there were 48 experimental forests and ranges, and their physical plants were being further developed. Forest genetics research received a boost in 1935 when James G. Eddy deeded the Eddy Tree Breeding Station to the Government. Inspired by the work of Luther Burbank, lumberman Eddy founded the station in 1925. It is now part of the Forest Service's Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station in California. Research did not really expand until the post-World War II economic boom and cold war generated funding increases. Employment of large numbers of professional scientists allowed projects in pure research—such as forest genetics and fire spread. In the late 1950's, the structure of Forest Service Research changed from one of centers to one of projects. Under the new system, a senior scientist led a project and supervised its staff. Relative to Forest Recreation Research, Chief Cliff noted that the agency was only beginning to explore this new field. In his words, "a rapid expansion of the relatively new and unexplored field of research...will provide a better basis upon which to handle the problems of policy and management of forest recreation...it is long overdue." At first, the recreation research program operated within the Division of Forest Economics; it was then shifted to the Division of Range Management Research. In 1959, Harry W. Camp was appointed to be the first head of Forest Service Recreation Research. Between 1963 and 1983, Forest Service recreation research became more clearly defiined and gained in popularity and scientific significance. The Forest and Rangland Renewable Resources Research Act of 1978, which supplanted the McSweeney-McNary Act, revised Research's charter. Outside groups put increasing pressure on Forest Service Research to develop baseline studies to guide management of national forest resources. Research became more complicated and, at times, isolated from local needs—a situation that is now changing with the new emphasis on ecosystem-based management and collaborative stewardship. |

Recreational Developments

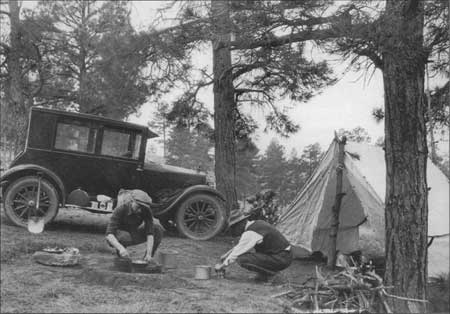

In the Forest Service's early days, it was against legislation to create a National Park Service (NPS) to manage the national parks (the act passed Congress in 1916). To counter the recreation component of the new NPS, the Forest Service initiated an extensive outdoor recreation program, including leasing summer home sites and building campgrounds on many national forests. The first Forest Service campground was developed in 1916 at Eagle Creek on the Oregon side the Columbia River Gorge on the Mt. Hood National Forest. Apparently, the first cooperative campground was constructed in 1918 at Squirrel Creek on the San Isabel National Forest near Pueblo, Colorado, at the time Federal funding was lacking and communities saw the need for better camping and picnicking facilities on the national forests.

|

| Campground on the Cibola National Forest (New Mexico), 1924 (USDA Forest Service) |

|

RECREATION ON THE NATIONAL FORESTS Adapted from E. Gail Throop's 1989 Conference Paper and L.C. Merriam, Jr.'s article in Encyclopedia of American Forest and Conservation History (1983), Vol. 2: 571-576. Although recreation was not specifically included in the Forest Reserve Act of 1891, it could be reasonably inferred to be included among the compatible uses of the forest reserves. The Organic Act of 1897 and implementing regulations allowed many activities on the forest reserves (renamed as national forests in 1907), including camping and hunting. Most important was the potential for these visitors to start fires: "Large areas of the public forests are annually destroyed by fires, originating in many instances through the carelessness of prospectors, campers, hunters, sheep herders, and others, while in some cases the fires are started with malicious intent. So great is the importance of protecting forest from fire, that this Department will make special effort for the enforcement of the law against all persons guilty of starting or causing the spread of forest fires in the reservations in violation of the above provisions." Before the first forest rangers of the General Land Office (GLO) took to the woods in the summer of 1898, picnickers, hikers, mountain climbers, campers, hunters, and anglers—individually and as families and other groups—were among the regular users of the forest reserves. The first legislation to recognize recreation in the Forest Reserves was enacted February 28, 1899. The Mineral Springs Leasing Act permitted the building of sanitariums and hotels in connection with developing mineral and other springs for health and recreation. The act stated the regulations will be issued "for the convenience of people visiting such springs, with reference to spaces and locations, for the erection of tents or temporary dwelling houses to be erected or constructed for the use of those visiting such springs for health and pleasure." The revised GLO regulations set forth in the 1902 Forest Reserve Manual stipulated to the right of the public to travel on the forest reserves for pleasure and recreation. However, recreation was considered to be secondary to the need for forest management, especially through grazing opportunities and later through timber harvesting. In the 1905 Use Book there were statements noting that the national forests served many purposes, some of which were related to early recreationists: "The following are the more usual rights and privileges...(a) Trails and roads to be used by settlers living in or near forest reserves. (b) Schools and churches. (c) Hotels, stores, mills, stage stations, apiaries, miners' camps, stables, summer residences, sanitariums, dairies, trappers' cabins, and the like..." The 1907 The Use of the National Forests book (public version of the Use Book), included such statements as: "Playgrounds.—Quite incidentally, also, the National Forests serve a good purpose as great playgrounds for the people. They are used more or less every year by campers, hunters, fishermen, and thousands of pleasure seekers from the near-by towns. They are great recreation grounds for a very large part of the people of the West, and their value in this respect is well worth considering." By 1913, the annual Forest Service report raised the issue of the need for sanitary regulation to protect public health. The report also listed 1.5 million "pleasure seekers," of whom a little over 1 million were day visitors, in the 1912-1913 fiscal year. Campers, including those who engaged in hunting, fishing, berry or nut picking, boating, bathing, and climbing totaled 231,000 and guests at houses, hotels, and sanatoriums came to 191,000. The Forest Service undertook development of recreation facilities in the national forests as early as 1916. The first official campground was the Eagle Creek Campground along the Columbia River Highway in Oregon's Mt. Hood National Forest. It was a "fully modern" facility with tables, toilets, a check-in station, and a ranger station. In the summer of 1919, nearly 150,000 people enjoyed the Eagle Creek facilities. At the same time, the Forest Service was opposed to the creation of a National Park Service to administer the national parks. At one time, the Forest Service proposed that it could manage all the national parks, but, obviously, this was not approved by Congress. When the United States Department of the Interior National Park Service was established in 1916, it was given a dual role—preserve natural areas in perpetuity and develop the parks as recreation sites. Early in 1917, the Forest Service hired Frank A. Waugh, professor of Landscape Architecture at Massachusetts Agricultural College, Amherst (now University of Massachusetts) to prepare the first national study of recreation uses on the national forests. Recreation Uses in the National Forests, Waugh's 1918 report on the status of recreation noted that some 3 million recreation visitors used the national forests each year. He summarized the types of facilities found in the forests—publicly owned developments consisted almost entirely of automobile camps and picnic grounds, while the private sector provided fraternal camps, sanatoria, and commercial summer resorts. In addition there were "several hundred" small colonies of individually owned summer cabins. With the first crude recreation use figures, collected during the summer of 1916, he figured a recreation return of $7,500,000 annually on national forest lands. Waugh did not address winter sports, as it was just beginning on the national forests—as early as 1914, the Sierra Club was conducting cross-country ski outings on California's Tahoe National Forest. Although the development of recreation on the national forests was a slow progress during the period from 1919 to 1932, it was not an era without controversy and change. Responsive to the need for improved public service, the agency generally supported the idea of professional planning and design. To this end it hired a "recreation engineer," landscape architect Arthur Carhart, in 1919, to begin recreational site planning. The year 1920 marked the competition of the first forest recreation plan for the San Isabel National Forest in Colorado. Carhart proposed that summer homes and other developments not be allowed at Trappers Lake on the White River National Forest in Colorado. In 1921, he surveyed the Quetico-Superior lake region in Minnesota's Superior National Forest where he recommended only limited development. It eventually became the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness. In 1921, while attending the first National Conference on State Parks, Carhart discussed national forest recreation uses. He was challenged by Park Service Director Stephen Mather who stated that recreation was the work of the National Park Service, not the Forest Service. Differences of opinion over recreation has been a source of controversy between the agencies for decades. The National Conference on Outdoor Recreation in 1924 criticized the two agencies for over development of their recreation programs. The conference went so far as to accuse the National Park Service of swapping the concept of preserving the Nation's natural wonders for the concept of the creating a "people's playground." Arthur H. Carhart and Aldo Leopold believed that wilderness was a recreational experience unmatched by the drive to develop areas for heavy recreation use. The Gila Wilderness—the Nation's first wilderness—was established on the New Mexico's Gila National Forest in 1924. Carhart later wrote that "there is no higher service that the forests can supply to individual and community than the healing of mind and spirit which comes from the hours spent where there is great solitude." Early in the decade, while ground was gained on the budgeting front, professional expertise in planning and design was lost. Arthur Carhart resigned because of what he perceived as a lack of support for recreation in the agency—he was not replaced by a person trained in the landscape design disciplines. At the time, only three regions—Northern, Pacific Southwest, and Pacific Northwest—had personnel assigned to recreation duties. Other regions either indicated too little recreation activity to merit specialized personnel or a determination to develop their own forester-recreationists. Throughout the decade of the 1920's, the Forest Service pursued a cautious conservative recreation site development policy. Generally, that policy held that the recreation role of the national forests was to provide space for recreation. Publicly financed recreation facilities remained limited in number and usually simply in nature. Yet by 1925, there were some 1,500 campgrounds in the national forests. This policy of limited development of national forest recreation sites fit both the philosophical outlook of the forest managers and the budgetary goals of the Coolidge and Hoover Administrations and of Congress. A National Plan For American Forestry (the Copeland Report) was prepared by the Forest Service in 1933. The section on recreation was written by collaborator Robert Marshall. In May 1937, Bob Marshall filled the new position of Chief of the Division of Recreation and Lands. He had a strong and long-lasting influence on recreation policy an development, especially that of wilderness. Using mainly Civilian Conservation Corps labor, the Forest Service built recreation structures from coast to coast. Under Marshall's guidance, a tremendous variety of facilities were built, many of them elaborate, that were unprecedented in the Forest Service. Facilities such as bathhouses, shelters, amphitheaters, downhill ski areas, and playgrounds were part of large recreation complexes. Recreation was established as a national administrative priority of the Forest Service. Following World War II, Americans aggressively sought an improved quality of life that included active participation in all forms of outdoor recreation. The socioeconomic influences of the post-war baby boom, increased affluence, increased leisure time, and improved transportation systems and population mobility led to unprecedented growth in demand for outdoor recreation. Visitors to the national forests were seeking hunting and fishing opportunities, developed campgrounds, downhill ski areas, picnic areas, wilderness experiences, water access, and hiking trails. The supply of recreation sites was soon overwhelmed by this demand. In 1958, Congress created the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission to review the overall outdoor recreation opportunities in the United States. When the final report was printed in 1961, the commission made a number of recommendations that have affected forest recreation. The commission recommended passage of the Wilderness Act—which was signed into law in 1964—and the creation of a Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in the Department of the Interior. Interior Secretary Stewart Udall appointed Edward Crafts, former Forest Service Assistant Chief, as the agency's first director. As the start of the 1960's, there was another surge in the national interest in the "great outdoors." This ushered in the era of growing national recreation interests and the desire for preservation of lands and history. This was also an era when America looked to the Federal Government to solve the Nation's problems and provide for social needs of the citizens. The Wilderness Act of 1964 created the National Wilderness Preservation System. National Recreation and Scenic Areas, Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Scenic Trails legislation followed throughout the next two decades. In 1985, President Reagan established the President's Commission on America's Outdoors to review existing outdoor recreation resources and to make recommendations that would ensure the future availability of outdoor recreation for the American people. The thrust of this commission was away from Federal centralism and strongly toward public-private partnerships. The Forest Service response to socioeconomic changes of this period took the form of an exciting and imaginative national initiative, the National Recreation Strategy. The preferred tool to meet this strategy was the development of partnerships between other public and private providers of outdoor recreation. This strategy is operational and significant progress toward the objectives has been made. |

Railroad Land Grants

When the Southern Pacific Railroad Company failed to live up to the terms of its 19th century land grant to the Oregon and California (O&C) Railroad (purchased by Southern Pacific), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the remaining unsold grant land must be returned (revested) to the Federal Government. Extensive congressional hearings in 1916 resulted in the return of 2.4 million acres of the heavily forested O&C lands, which today are managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the Forest Service. The Northern Pacific Railroad land grant, across the northern tier of States from Minnesota to Washington, also came under scrutiny by Congress, but ownership remained with the railroad. Interestingly, when Mount St. Helens exploded in 1980, the top of the mountain was owned by the railroad—part of the old land grant—and was traded with Forest Service land to establish the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument in 1982.

The Pisgah National Forest, the first national forest that was from almost entirely purchased private land, was established on October 17, 1916. The core portion of the new forest came from the privately owned Biltmore Forest (once managed by Gifford Pinchot). Land purchases for the Pisgah began in 1911, soon after the passage of the Weeks Act.

World War I and Aftermath

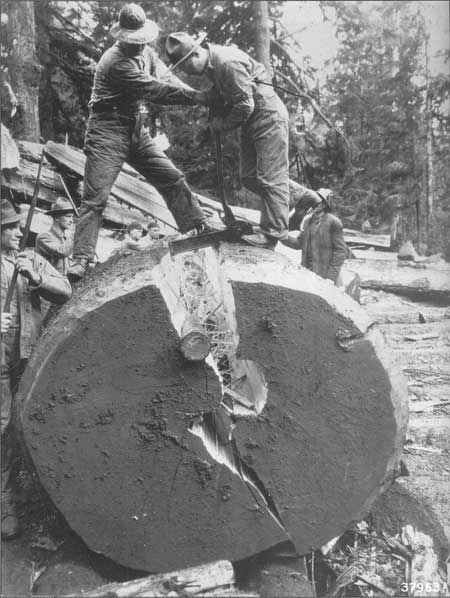

Two U.S. Army Engineer Regiments (10th and 20th Forestry) formed in 1917 and 1918 to fight in Europe during World War I. Many Forest Service employees joined these regiments and after arriving in France were assigned to build sawmills, to provide timbers for railroads and to line trenches. One of their leaders, Lt. Colonel William B. Greeley, later became the third Chief of the Forest Service. Another unique organization formed during the war was the U.S. Army Spruce Production Division. Some 30,000 Army troopers were assigned to Washington and Oregon to build logging railroads and cut spruce trees for airplanes and Douglas-fir for ships. Although the Spruce Division lasted only 1 year (1918-19), it affected private and public logging operations and unions for the next two decades. Remnants of the spruce railroads can still be found on the Siuslaw National Forest in Oregon and the Olympic National Park in Washington State, which was then part of the Olympic National Forest.

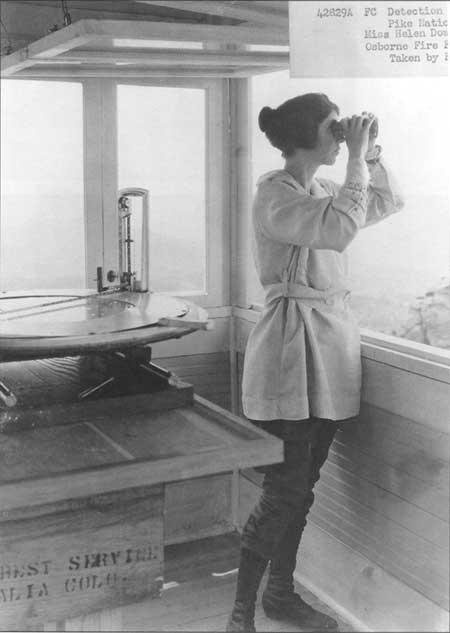

While the men were off fighting the war in Europe, women were employed outdoors as fire lookouts on many national forests. Women had worked in clerical positions for many years, but working outdoors was unusual.

In 1919, soon after the war, cooperative agreements between the Forest Service and the Army Air Corps led to experiments using airplanes to patrol for forest fires in California; this use was quickly expanded to the mountainous areas of Oregon, Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

|

| U.S. Army's Spruce Production Division Riving (Splitting) Tree, Washington, 1918 (USDA Forest Service) |

Before, and for a while after World War I, there were no radios—communications between the lookouts and the ranger station were limited to messages on foot, horseback, and carrier pigeon. Soon, however, an extensive (and expensive) system of field telephones, connected by miles and miles of telephone wires, was used to communicate between the lookouts atop the mountain peaks and the ranger stations in the valleys below.

|

| Helen Dowe, One of the First Female Lookouts, on the Pike National Forest (Colorado) (USDA Forest Service) |

These phone systems along major forest trails needed continual maintenance and repair as trees often fell on the No. 9 wire, breaking the connections. Many new forest fire lookout houses and towers using standardized construction plans were built during the 1920's. Two-way radios were invented during World War I, and there were many experiments after the war using the new two-way radios in fire detection. These radios eventually made communication much easier and less costly.

|

| Forest Service Air-Patrol Airplane at the Eugene, Oregon, Airfield with Lt. DeGarme (Pilot) and Mechanics, 1925 (USDA Forest Service) |

|

| Ranger Using a Heliograph in California, 1912 (USDA Forest Service) |

|

| Mr. Adams Demonstrating the First Wireless Radio Used in the National Forests at the Montana State Fair, Helena, Montana, 1915 (USDA Forest Service) |

|

HALLIE M. DAGGETT—WOMAN LOOKOUT Although women have been Forest Service employees since 1905, for many decades very few were hired for field work. Yet as early as 1902, during the General Land Office days, wives (who were not employees) sometimes accompanied their forest ranger husbands into the wild forests. One of the first accounts of women employed as forest fire lookout comes from California on the Klamath National Forest. The lookout was Hallie M. Daggett who worked at Eddy's Gulch Lookout Station atop Klamath Peak in the summer of 1913 (and for the next 14 years). A 1914 article in the American Forestry) magazine described her work. Few women would care for such a job, fewer still would seek it, and still less would be able to stand the strain of the infinite loneliness, or the roar of the violent storms which sweep the peak, or the menace of the wild beasts which roam the heavily wooded ridges. Miss Daggett, however, not only eagerly longed for the station but secured it [the lookout job] after considerable exertion and now she declares that she enjoyed the life and was intensely interested in the work she had to do. Some of the [Forest] Service men predicted that after a few days of life on the peak she would telephone that she was frightened by the loneliness and the danger, but she was full of pluck and high spirit...[and] she grew more and more in love with the work. Even when the telephone wires were broken and when for a long time she was cut off from communication with the world below she did not lose heart. She not only filled the place with all the skill which a trained man could have shown but she desires to be reappointed when the fire season opens this year [1914].... [In describing her life as a lookout, Hallie said that] "I grew up with a fierce hatred of the devastating fires and welcomed the [Forest Service] force which arrived to combat them. But not until the lookout stations were installed did there come an opportunity to join what had up till then been a man's fight; although my sister and I had frequently been able to help on the small things, such as extinguishing spreading camp fires or carrying supplies to the firing line. "Then, thanks to the liberal mindedness and courtesy of the officials in charge of our district, I was given the position of lookout...with a firm determination to make good, for I knew that the appointment of a woman was rather in the nature of an experiment, and naturally felt that there was a great deal due the men who had been willing to give me the chance. "It was quite a swift change in three days, from San Francisco, civilization and sea level, to a solitary cabin on a still more solitary mountain, 6,444 feet elevation and three hours' hard climb from everywhere, but in spite of the fact that almost the very first question asked by everyone was 'Isn't it awfully lonesome up there?' I never felt a moment's longing to retrace the step, that is, not after the first half hour following my sister's departure with the pack animals, when I had a chance to look around....I did not need a horse myself, there being, contrary to the general impression, no patrol work in connection with lookout duties, and my sister bringing up my supplies and mail from home every week, a distance of nine miles." |

|

William Buckhout Greeley was born in Oswego, New York, on September 6, 1879. After Greeley was appointed Chief in 1920, he faced a number of challenges, including the acquisition of new national forests east of the Mississippi River, making cooperation with private, State, and other Federal agencies a standard feature of Forest Service management; fighting the Government's renewed efforts to return the Forest Service to the Department of the Interior; and "blocking up" the national forest (exchanging or purchasing lands inside or near the forest boundaries to simplify management). During his administration, the Clarke-McNary Act of 1924, which extended Federal authority to purchase forest lands and to enter into agreements with the various States to help protect State and private forests from wildfire, became law. This time, the "Roaring Twenties," was when prosperity brought about tremendous growth in recreation on the national forests and led to the need to develop and improve roads for automobile use, campgrounds for forest visitors, and summer home sites for semipermanent users. During this era, the Forest Service also began several important programs to better manage the national forests, including an extensive system of basic and applied research, timber management, recreation, and highways to provide better access to and across the national forests. William B. Greeley wrote:

|

Timber Sales

The economic boom of the "Roaring Twenties" vastly increased the need for wood products. Many extensive national forest timber sales were authorized, including a 1921 sale of 335 million cubic feet of pulpwood on Alaska's Tongass National Forest. Within a few years, scores of huge timber sales were being made, including a 1922 sale on the California's Lassen National Forest that topped 1 billion board feet. Previously, most timber sales had been for rather small volumes—many of them related to timber beams for mining and ties for railroads. A considerable number of the new sales were large railroad logging operations that were geared for lengthy harvesting periods of several decades or longer. The national forests began to play an increasing role in providing timber for the United States.

|

Although the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 established Presidential authority to create forest reserves, there was no provision for their management. One of the underlying premise of the act was that the private timber lands were being cut at rates that could not be sustained, especially since reforestation was mostly a dream. The Organic Administration Act of 1897 was written, in part, to "furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States..." However, the congressional debate and the 1897 Act's implementing regulations made it clear that timber cutting was always considered to be permitted, not a required part of forest management. The Organic Act also allowed the General Land Office (GLO) to manage the forest reserves. The first timber sale by the GLO (Case No. 1) was to the Homestake Mining Company for timber off the Black Hills Forest Reserve in 1898. Fifteen million board feet were purchased at a dollar per thousand board feet. The contract required that no trees smaller than eight inches in diameter be removed and that after the harvest the brush left behind had to be "piled." Thus began the effort to remove billions of board feet of timber from the national forests. When the management of the forest reserves was moved from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture in 1905, Chief Gifford Pinchot was concerned that the reserves (renamed national forests in 1907) should pay for themselves, that is, not be a drain on the U.S. Treasury. The most direct way of showing a profit was by charging for grazing and selling timber. By 1907, timber sold from the national forests amounted to just 950 million board feet, which was only 2 percent of the Nation's 44 billion board feet cut that year. Pinchot finally gave up by stating "the national forests exist not for the sake of revenue to the Government, but for the sake of the welfare of the public." From the late 1910's and through the 1930's, there was an emphasis by the Forest Service and outside groups to "sell" the idea of a coming "timber famine." Based on overcutting in the Great Lake States and elsewhere came the widely espoused notion that that Nation was running out of trees, which would lead to rising cost of housing, mining shutdowns because of lack of mining timbers, railroads without wooden ties, and water diminished for crops. A 1920 Forest Service ("Capper") report to Congress also warned of forest depletion as a major national problem. Ironically, forest net annual wood growth actually rebounded nationally in 1920, with total forested area about constant from that date, after its severe decline in the 19th century and first two decades of the 20th. Only 3 years later the Senate passed a resolution (SR 398 on March 7, 1923) to provide for an investigation "relating to problems of reforestation, with a view to establishing a comprehensive national policy for lands chiefly suited to timber production, in order to insure a perpetual supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizen of the United States." Through the 1920's there were few timber sales, those that were made were usually quite large, selling entire drainages at one time. Other than small operations, the timber sales were designed for railroad logging operations that would harvest the drainages over decades. The timber sales program collapsed in the 1930's with the advent of the Great Depression. A pamphlet entitled "Deforested America" (1928) by Major George P. Ahern warned of the risks of depending on private forests and the forest industry for future supplies of timber. Instead, Ahern argued, government control was required to ensure that sustained-yield forestry would be practiced on commercial forest lands. The argument for Federal regulation of private forestry was codified in Article X of the Lumber Code effective on June 1, 1934. Although the code was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court less than a year later, the timber industry was generally supportive of efforts at self-regulation to end widespread forest devastation and to develop cooperation between industry members and a closer cooperation with the Forest Service. Due to the defense needs during World War II, timber sales increased in the early 1940's. The Forest Service began to think about the needs after the war, which saw passage of the Sustained Yield Management Act of 1944. This act allowed the agency to sign agreements with the timber industry and communities to establish either cooperative sustained yield units or Federal units. Only one cooperative unit was ever established (Shelton on the Washington's Olympic National Forest). Five Federal units were established in Washington, Oregon, California, Arizona, and New Mexico. With the return of the veterans after the war, a baby boom took place (60 million births from 1946 to 1964) during a period of economic growth. This was fueled by low interest rates and massive housing starts. Other Federal agencies answered this call for goods as well. The rapid depletion of old growth timber on private timber lands in the 1950's further reinforced the need for increased harvests on Federal lands. During the 1950's, timber harvests on national forests almost tripled going from about 3 billion board feet in 1950 to almost 9 billion at the end of the decade. The impact was felt most in Pacific Northwest Region, the major producer of softwood timber in the National Forest System. The Multiple Use Act of 1960 set new priorities for the agency, essentially giving equal footing to the five major resources on the national forests: timber, wildlife, range, water, and outdoor recreation. By the late 1960's, the Forest Service felt increasing opposition because of major controversies on the Bitterroot National Forest in Montana—involving clearcutting and terracing—and Monongahela National Forest in West Virginia—also involving clearcutting. A lawsuit (Izaak Walton vs. Butz) was filed on the Monongahela controversy by the Izaak Walton League. A court ruling in 1973 on the case was against the Forest Service practice of timber harvesting under the rules of the Organic Act of 1897. Congressional action was necessary to "fix" the law. Congress passed sweeping legislation called the National Forest Management Act of 1976 that pushed deep into the agency's traditional autonomy with many new requirements and substantive restrictions, almost all of which revolved around timber harvesting. By the early 1980's, the findings of decades of important scientific forest research provided much needed clues to the long-term health and productivity of the coniferous forests of the Northwest. Because of extensive research carried out on the H.J. Andrews Experimental Forest (part of the Willamette National Forest), Jerry Franklin and Chris Maser were able to make some preliminary conclusions that indicated there was more to the forest than the trees. They briefly led the Forest Service into "new forestry" and "new perspectives" in the search for alternative ways to manage the Federal forests. In the summer of 1992, the Forest Service embraced a new concept called ecosystem management. Ecosystem management was not a reinterpretation of current field practices to fit a new national agenda, as multiple use generally was. Rather, it is a new goal for the national forests that was more philosophical and addressed the larger societal questions and values surrounding the management of the national forests. |

|

| Campers at Feralta Canyon near the Superstition Mountains, Tonto National Forest (Arizona), 1938 (USDA Forest Service) |

Recreation and Wilderness

In the early 1920's, there was an increasing need for improved recreational facilities on the national forests. A good part of this need was caused by the increasing use of the forest roads and trails by recreationists' automobiles. As more cars became cheaper, reliable, and available, more people were willing to spend some of their free time in the mountains, at lakes, and along streams—as long as these areas were easily accessible. Existing roads and highways had to be improved. In this same era, the Forest Service began to use trucks and automobiles—a significant change from the days of the horse, packhorse, and mule.

|

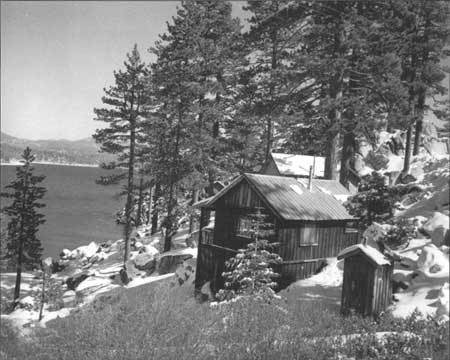

| Summer Home Along Big Lake on San Bernardino National Forest (California), 1946 (USDA Forest Service) |

Numerous special-use recreation resorts, which provided for developed recreation facilities in popular areas, began operation on the national forests. Long-term summer home leases were allowed to give people greater use of the national forests. Hundreds of new campgrounds were opened as many thousands of people now owned or had access to automobiles.

One of the Forest Service's first wilderness advocates was Arthur H. Carhart, a landscape architect. In the late 1910's and early 1920's, his innovative ideas, which involved leaving some forest areas intact (no development) for recreational use, received limited support. He proposed that an area around Trapper's Lake on Colorado's White River National Forest remain roadless and that summer home applications for that area be denied. He developed a functional plan for the Trapper's Lake area to preserve the pristine conditions around the lake and convinced his superiors to halt plans to develop the area. Later, he recommended that the lake region of the Superior National Forest in northern Minnesota be left in primitive condition and that travel be restricted to canoe. This plan was approved in 1926 and the Boundary Waters Canoe Area was dedicated in 1964. Carhart, however, frustrated by what he felt was a lack of support from the Forest Service, resigned in December 1922.

|

| Arthur Carhart in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness, Superior National Forest (Minnesota) (USDA Forest Service) |

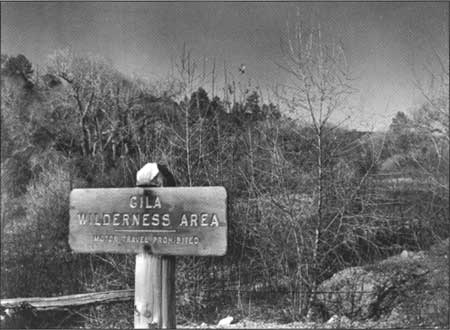

Aldo Leopold, author of the Sand County Almanac, however, took up where Carhart left off. In 1922, Leopold made an inspection trip into the headwaters of the Gila River on New Mexico's Gila National Forest. He wrote a wilderness plan for the area, but faced opposition from his own colleagues who thought that development should take precedence over preservation. His plan was approved in June 1924 and the 500,000-acre area became the first Forest Service wilderness—the Gila Wilderness. Leopold transferred to the Forest Products Laboratory, the same year, and then resigned from the Forest Service in 1928. Five years later he began teaching at the University of Wisconsin, where he had a profound influence on students and the public.

|

| Forest Service Ranger Boat, Tongass National Forest (Alaska) (USDA Forest Service) |

In 1929, the Forest Service published the L-20 Regulations concerning primitive areas that were basically undeveloped areas, many of which would later become wildernesses. Regional Offices were required to nominate possible "primitive areas" that would be maintained in a primitive status without development activities—especially roads. Within 4 years, 63 areas, comprising 8.7 million acres were approved. By 1939, the total acreage in primitive classification had increased to 14 million acres.

Many new forest fire lookouts (houses and towers) were built in the early 1920's, while two-way radios were becoming more practical and used extensively to communicate during forest fires. The Clarke-McNary Act of 1924, an extension of the Weeks Act, greatly expanded Federal-State cooperation in fire control on State and private lands. Many States formed fire protection associations.

|

| Gila Wilderness Sign, Gila National Forest (New Mexico), 1960 USDA Forest Service |

Forestry research came into "full swing" with the establishment of two new experiment stations in 1922. Today, there are seven experimental stations scattered across the country, with 72 research work unit locations.

The natural resource controversy of the early 1920's was over a huge increase in the number of mule deer on the Grand Canyon Federal Game Preserve (established in 1906) on Arizona's Kaibab National Forest. In 1906, the deer herd numbered only about 3,000, but after almost 20 years without being hunted and with predator control, the herd exploded to more than 100,000 animals. The Forest Service sought to reduce the number of deer on the refuge to prevent many from starving. In 1924, the case went to the U.S. Supreme Court—that ruling allowed the Forest Service to hunt excess deer to protect wildlife habitat.

|

| Sleeping Beauty Lookout, Columbia National Forest (Washington), 1937 |

|

Adapted from Terry West's Arthur H. Carhart was a national leader of the early 20th century conservation movement, especially in advocating wilderness areas. He was born in Mapleton, Iowa, in 1892, and received his bachelor's degree in landscape architecture and city planning from Iowa State College in 1916. He served in the U.S. Army Medical Corps during World War I, then joined the Forest Service as its first landscape architect in 1919. Arthur Carhart viewed wilderness as a recreational experience and proposed that summer homes and other developments not be allowed at Trappers Lake on the White River National Forest in Colorado. After surveying the Superior National Forest in the Quetico-Superior lake region in 1921, he recommended only limited development and became a strong advocate for wilderness recreation for that roadless area. Carhart later wrote that "there is no higher service that the forests can supply to individual and community than the healing of mind and spirit which comes from the hours spent where there is great solitude. It is significant that people who have experienced the fullness of wilderness living, specifically men of the forests [Forest Service], have initiated and labored for keeping some parts of them as wildland sanctuaries." Carhart resigned from the Forest Service in 1922 to practice landscape architecture and city planning in the private sector. His dream to protect wilderness recreation areas from development took the Forest Service 4 more years to accomplish. With Aldo Leopold's successful effort to have an administrative wilderness established in 1924 on the Gila National Forest, time was ripe for additional wilderness designations on the national forests. Secretary of Agriculture William H. Jardine signed a plan to protect the Boundary Waters area in 1926, and it was dedicated as the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in 1964 with it finally becoming a wilderness in 1978. Chief William Greeley was willing to endorse the concept of wilderness areas and, in 1926, ordered an inventory of all undeveloped national forest areas larger than 230,400 acres (10 townships). Three years later, wilderness policy assumed national scope with the promulgation of the L-20 regulations. Commercial use of the areas (grazing, even logging) could continue, but campsites, meadows for pack stock forage, and special scenic "spots" would be protected. It would take many years until a national wilderness policy, set by Congress, would be enacted as the Wilderness Act of 1964. In 1938, Carhart was appointed director of the Colorado program for Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration. He wrote numerous articles, many for the American Forests, the publication of the American Forestry Association. He also wrote a number of books on conservation matters including: The Outdoorsman's Cookbook (1944), Fresh Water Fishing (1950), Water—or Your Life (1951), Timber in Your Life (1955), Trees and Game—Twin Crops (1958), and The National Forests (1959). |

|

Rand Aldo Leopold was born on January 11, 1887, in Burlington, Iowa. Aldo—he never used his first name—was the oldest of four children. He loved to hunt, fish, and explore the bluffs, forests, marshes, lakes, and fields along the nearby Mississippi River. His father, Carl Leopold, taught Aldo different ways to see nature firsthand. Aldo's love of the out-of-doors did not sit well with his grades during the second part of his high school years that he spent at the Lawrenceville Preparatory School near Princeton, New Jersey. Writing to his mother, Clara, in 1904, Aldo mentioned that "I have flunked Geometry..." However, he did finish prep school and went on to attend Sheffield Scientific School at Yale in New Haven, Connecticut, the following year. In 1906, Leopold began his forestry course work at the Yale School of Forestry, which had been founded by a grant from James Pinchot. Leopold received his B.S. degree in 1908 from the Sheffield School and then graduated in 1909 with a masters in forestry. Soon after graduation he joined the Forest Service and was assigned as a forest assistant to the new Southwestern District (now region). A month later, he was in charge of a timber reconnaissance crew on the Apache National Forest in the Arizona Territory when he saw "a fierce green fire" in the eyes of a dying old wolf. He never forgot that haunting look and it affected his thoughts for the rest of his life. By 1911, Leopold had been promoted to deputy forest supervisor and, a year later, he was promoted to Supervisor of the Carson National Forest in the New Mexico Territory. In 1912, Aldo married Estella Bergere from Santa Fe, New Mexico (they would have five children together—Starker, Luna, Nina, Carl, and Estella). In 1913, he almost died of an attack of acute nephritis. It was during his almost 17-month recovery that he wrote about setting aside remote areas for special protection based on wilderness as part of the national heritage and the importance of studying nature in a pristine setting. In 1914, Leopold was assigned to the Office of Grazing in the Forest Service Southwestern District Office (D-3) in Albuquerque, New Mexico. While working on recreation, fish and game, and publicity for the district (Arizona and New Mexico) less than a year later, he wrote a report recommending that game refuges be established in the district and, then, a Game and Fish Handbook—the first such direction in the Forest Service. Leopold's growing concern about studying nature in natural, undisturbed settings arose through his exposure to the new science of ecology. (Ecology as an area of academic study was formed in 1915 when the Ecological Society of America was founded.) He began his life's work on wildlife management issues, including game refuges, law enforcement, and predator control, as well as founding a number of big game protective associations in New Mexico and Arizona. Because of these interests, he won the W.T. Hornaday's Permanent Wildlife Protection Fund's Gold Medal in 1917. In 1918, Leopold took a leave of absence from the Forest Service and served as the Secretary of the Albuquerque Chamber of Commerce. He returned to the Forest Service the next year as Assistant District Forester for Operations in the Southwestern Region. While in this role, Leopold developed new and efficient procedures for handling personnel matters, fire-control methods, and forest inspection procedures over some 20 million acres of national forest land. He made a number of important contributions to the soil erosion problems in southwestern watersheds. Concerned with the rapid pace of road construction after World War I, Leopold recommended that roads and use permits be excluded on the Gila River headwaters on the Gila National Forest in 1922. In the early 1920's, he was responsible for laying the groundwork for the Gila Wilderness. Established in 1924 as a 500,000-acre wilderness area, the Gila Wilderness was the first administrative wilderness in the National Forest System. Although his plan was approved, it was only a local policy, not national. Leopold left the Southwest in 1924 to serve as the assistant, then Associate Director of the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin. Leopold was unhappy at the Laboratory and resigned from the Forest Service in 1928 to take the lead in establishing a new profession—game management—which he modeled on the profession of forestry. His game survey of nine Midwestern States was funded by the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers' Institute. These surveys were summarized in his 1931 Report on a Game Survey of the North Central States. Leopold's book Game Management, published in 1933, was based in part on his game survey work and helped define a new field of managing and restoring wildlife populations. Soon after the publication of his book, Leopold accepted an appointment to a new chair in the Department of Agricultural Economics at the University of Wisconsin. Although Leopold spent the next several decades with wildlife management issues, his interests expanded to the field of ecology, where he is most revered today. In January 1935, Aldo Leopold, Bob Marshall, Benton Mackaye, Harvey Broome, Barnard Frank, Harold Anderson, Ernest Oberholtzer, and Sterling Yard founded the Wilderness Society. Leopold spent the fall of that year in Germany on a Carl Schurz fellowship studying forestry and wildlife management. During that same year he purchased a small, worn-out farm along the Wisconsin River—north of Baraboo, Wisconsin, in an area known as the "sand counties." This was where the family (wife Estella and their five children) rebuilt the only standing structure on the property—the chicken coop—into a small cabin. This cabin became famous as "The Shack." Trying to restore the health of the land, he planted thousands of trees on the property, slowly changing abandoned fields to a growing forest and restoring a low area into a wetland where waterfowl came flocking in to feed and rest. Daughter Dina wrote "as he transformed the land, it transformed him. By his own actions and transformation, Aldo Leopold instilled in his children [and students] a love and respect for the land community and its ecological functioning." He used the farm to observe and write about nature. Graduate students were brought to "The Shack" many times to observe and discuss ecological matters. In 1936, Leopold helped found a society of wildlife specialists (it became the Wildlife Society in 1937). His philosophy began to shift to a more ecological approach in the late 1930's. Susan L. Flader, in a biography of Leopold, characterized this shift: "Originally imbued like other early conservationists with the belief that man could rationally control his environment to produce desired commodities for his own benefit, Leopold slowly developed a philosophy of naturally self-regulating systems and an ecological concern with the land and a land ethic." It was a new way of thinking and acting toward the land. Leopold wrote about nature and people and that living with the land required a new or complete understanding of the interrelationships among all creatures. Author Amy McCoy noted that he "added unprecedented insight into the world of ecology and naturalism. He moved from believing in partial participation in nature, to the view that total integration is absolutely necessary to the healthy existence of the natural world, and of humans." This would become the basis, still with us today, of a profound reverence for nature and the role that people play in the environment—a land ethic for people. In 1939, the University of Wisconsin created a new department, the Department of Wildlife Management, with Leopold as its first chair. He held this position until his death. The new science and profession of wildlife management wove together the related fields of forestry, agriculture, ecology, biology, zoology, and education. He believed that people, who often destroyed landscapes, could use the same tools to help rebuild the land. Just before World War II, Leopold began working on a manuscript of ecological essays. It took several attempts to write and rewrite the volume, entitled Great Possessions, which was finally accepted for publication by the Oxford University Press on April 14, 1948. While at "The Shack" vacation home, smoke was spotted across the swamp on a neighbor's farm. Leopold gathered his family, handed out buckets and brooms, and went with them to put out the fire. While fighting the fire, Aldo Leopold died of a heart attack at the age of 61 on April 21, 1948. His ecological essays book was retitled and published as A Sand County Almanac in 1949. Over his lifetime, Leopold was involved with more than 100 organizations, many of which he served as an officer, president, or chair. Although Leopold, a gifted writer, wrote more than 350 articles, it was the books that he wrote—two of which were published posthumously (edited by Luna B. Leopold)—that have influenced today: A Sand County Almanac (1949) and Round River, from the Journal of Aldo Leopold (1953). A Sand County Almanac has sold millions of copies and is regarded as a classic with well-worn paperback copies in backpacks and book shelves across the country. Leopold has gained the status as a prophet of the environmental movement and his legacy continues to the present, with scores of new books and articles appearing every year about him and his work. |

|

Robert Young Stuart was born in the Southern Middleton Township, Cumberland County, Pennsylvania, on February 13, 1883. He was appointed Chief in 1928 after the resignation of Chief Greeley. During his tenure, the McSweeney-McNary Act of 1928 promoted forest research, while the Knutson-Vandenberg Act of 1930 was designed to expand tree planting on the national forests. Stuart was instrumental in preparing the Forest Service to deal with the crises caused by the stock market crash of 1929. He led the Forest Service in creating job opportunities for the unemployed on national forests, especially those working on Forest Service road systems. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt created the Civilian Conservation Corps in the spring of 1933 to relieve the severe economic stress among young unemployed men, the Forest Service was ready with a long list of projects. Robert Y. Stuart wrote:

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec3.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008