|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

THE GREAT DEPRESSION ERA, 1933-1942

The Great Depression is generally thought to have started in the fall of 1929 with the New York stock market crash. It did not take long for the entire country to be hard hit by the crash. Because of low wood prices and lack of demand, timber sales declined, hundreds of timber companies went bankrupt, and tens of thousands of employees lost their jobs. Federal Government workers took pay cuts, but remained working.

|

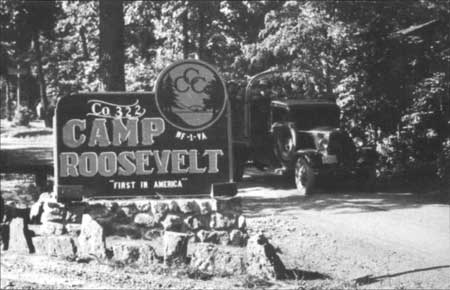

| CCC Camp Roosevelt, George Washington National Forest (Virginia), 1933 USDA Forest Service |

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), brainchild of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's "New Deal," began in April 1933 to revive the lagging economy and marked a renewed interest in the conservation of natural resources. The CCC, founded to provide outdoor work for millions of young unemployed men, later was expanded to include World War I veterans and American Indian tribal members. The first CCC camp, appropriately named Camp Roosevelt, began operation in the late spring of 1933 on Virginia George Washington National Forest. Thousands of other camps were established in national and State parks and refuges, national monuments, soil conservation districts, and other areas.

Fortunately, the Forest Service was prepared for these conservation workers. The massive 1,677-page, A National Plan for American Forestry (also called the Copeland Report), published a few months previously, had suggested a comprehensive plan for more intensive management of all the National Forest System lands. Included in the report were hundreds of projects that needed money or people to complete them. The CCC program was the ideal opportunity for young men (there were no women's camps) to be engaged in outdoor projects that would help improve the recreation potential and management of the national forests. Through the entire 9-year program, more than 3 million men enrolled for 6 months or longer in the over 2,600 camps (200 men per camp). Each national forest had at least one CCC camp. That enabled hundreds of work projects to begin, many of which were recreational facilities, especially trails, trail shelters, campgrounds, and scenic vistas. The CCC'S also worked on truck trails (roads), guard and ranger stations, lookouts, and telephone lines, and they fought many forest fires (nearly 6.5 million person days).

|

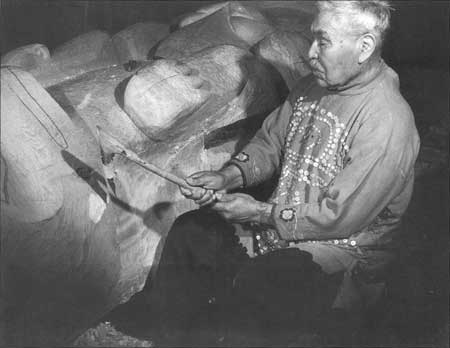

| CCC Tlingit Alaska Native Enrollee Joe Thomas Working on Baranof Pole at Wrangell, Alaska, Tongass National Forest, 1941 USDA Forest Service |

|

The year was 1933. The Nation was floundering in an economic depression, deeper than any it had ever known. Over 13 million Americans, about one-third of the available workforce, were out of work. People had nothing to do, nowhere to go, and often felt hungry, bewildered, apathetic, and angry. Young men were especially vulnerable as they were often untrained, unskilled, unable to gain experience, and often without an adequate education. They had little hope for the future. In this sad, tumultuous time, Congress passed an act that was to have great impact for unemployed young men and natural resource management. On March 4, 1933, Franklin D. Roosevelt was inaugurated as President. His "New Deal" program helped put people back to work. He quickly placed legislation before Congress to put ten of thousands of unemployed young men to work in the public forests and parks. On March 31, 1933, just 10 days after Roosevelt proposed it, Congress passed the Emergency Conservation Work Program (Public Law 73-5) popularly known as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Four years later, on June 28, 1937, the CCC name was officially attached to an act that continued the program. (Similar Federal work programs were established during the 1930's, including the Works Progress Administration which focused on arts, music, literature, history, and other related activities.) The act establishing the CCC had two purposes. The most important was the need to find immediate and useful conservation work for millions of unemployed young men; the second was to provide for the restoration of the country's depleted natural resources and the advancement of an orderly program of useful public works projects. The CCC also provided educational training, and beginning in 1940, vocational training, to its enrollees. The program was directed by Robert Fechner, until his death in January 1, 1940, thereafter by James McEntee. Eligibility requirements to join the CCC were handled by the U.S. Department of Labor and State selection organizations. CCC enrollees were required to be—

These young men were officially referred to as juniors. There were three other categories of CCC enrollees:

There were no camps for women, although Eleanor Roosevelt suggested that there should be. Black enrollees were generally separated from white enrollees with segregated CCC companies and camps. In any case, the enrollees were required to set aside $25 of their monthly $30 paycheck to assist their dependents (usually their parents). The CCC enrollment period was for 6 months, with options for renewal. The CCC "boys" were often assigned, initially, to the Forest Service or National Park Service to work on conservation projects. Later, a number of CCC camps were established for the Bureau of Indian Affairs, State forests and parks, Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resources Conservation Service), Biological Survey (later Fish & Wildlife Service), Bureau of Reclamation, General Land Office (now Bureau of Land Management), U.S. Army and Navy, and even some private demonstration forests. The U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Army handled CCC monthly pay, as well as travel to and from the often remote CCC camps. A CCC company usually consisted of 200 enrollees, with most of them coming from one city or county within a State. When the CCC men arrived, usually by train then truck, at their assigned CCC camp, they lived in comfortable World War I surplus pyramid tent frames or wooden barracks. The camp commander was usually a career military officer, or, later in the program a reserve officer. On various projects, smaller work camps (called side or spike camps) were established so that the men did not spend all of their project time getting to or from the work site. The CCC men ate plain but wholesome food, which was purchased locally. They worked 40 hours per week and were required to keep their camps neat and orderly. Beyond that, they were free to study or enjoy any outdoor recreation opportunities such as swimming or fishing. During the summer months, the CCC boys were often treated to weekend trips to beautiful mountain lakes, national parks, or the coast. At other times, the local communities took pleasure in providing facilities for meeting the local citizens, dancing, and having good times. Some of the young men, products of the Great Depression and coming from all parts of the country and all walks of life, later stayed in or returned to the community that had served as their temporary home away from home. Many of the CCC men who stayed went on to become prominent foresters, businessmen, and even State legislators. Throughout the CCC history (1933-1942), the number of conservation projects completed across the Nation was staggering; 48,060 bridges; 13,513 cabins and dwellings; 10,231 fire lookout houses and towers; 360,449 miles of telephone lines; 707,226 miles of truck trails (forest roads); 142,102 miles of foot and horse trails; 101,777 acres of campground development; 35.8 million rods of fences; 168 emergency landing fields; 13.3 million acres of insect control work; 6.4 million man-days of fighting forest fires; over 2.6 million acres of planting and seeding; and almost 1 billion fish stocked. As national economic conditions improved in the late 1930's, enrollment quotas became more and more difficult to fill. Then on December 7, 1941, America became directly involved in the war that had been raging in Europe for more than 2 years. Within 6 months, the CCC era came to a close as enrollees flocked to join the military and the remaining camps were shut down. The program's funding was terminated on June 30, 1942. So ended one of the most successful work recovery programs in the history of the United States. The CCC was the most popular and successful of Roosevelt's New Deal programs. Perhaps the most significant product of the CCC program was the profound and lasting effect it had on the 3 million enrollees. CCC work provided a turning point in the lives of many of the Nation's youth and it brought much-needed financial aid to their families. In addition, it created a new self-confidence, a desire and capacity to return to active work, a new understanding of a great country, and a faith in its future. The national forests, national parks, and State parks decades later still enjoys benefits from many of the CCC projects. |

|

Ferdinand Augustus Silcox was born on Christmas Day in 1882, in Columbus, Georgia. The Great Depression was in full-swing when Silcox took over as Chief in 1933; he led the Forest Service during some of its most difficult times. He was able to effectively help millions of unemployed workers thrive during the Depression through the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration projects on the national forests. The Forest Service provided space to 200-man CCC camps (there were no women in the program), thousands of work projects, and experienced project leaders. More than 2.5 million unemployed young men enrolled in the CCC during its 9-year existence. Silcox's contributions to the forest conservation movement were many, but especially significant was his success in focusing public attention on the conservation problems of private forest land ownership. During his tenure, the Forest Service studied western range use and surveyed forest watersheds for flood control. Ferdinand A. Silcox wrote:

|

|

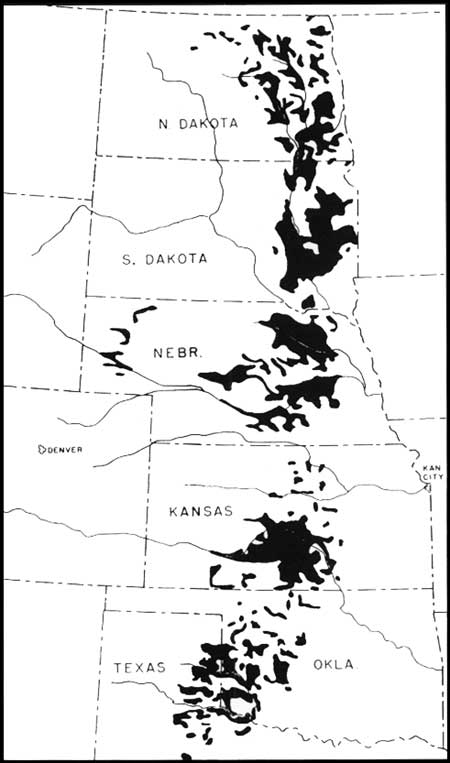

| Major Planting Areas of the Prairie States Forestry (Shelterbelt) Project, 1935-1942 USDA Forest Service |

Shelterbelt Project

In response to the "Dust Bowl" conditions in the Great Plains between Texas and North Dakota during the early 1930's, the cooperative Prairie States Forestry (Shelterbelt) Project was begun. This unique windbreak project, an idea of President Franklin Roosevelt, began in 1934. In March 1935, the first tree was planted on a farm in Mangum, Oklahoma. The project involved extensive cooperation between the USDA Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resources Conservation Service); various State, county, and local agencies; and hundreds of farmers. Legions of Works Progress Administration (WPA) relief workers, many of whom were unemployed farmers, accomplished the work. In the spring of 1938, they planted approximately 52,000 cottonwood trees in one severely sand-blown area south of Neligh, Nebraska.

The Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 ended unregulated grazing on the national forests and remaining GLO-administered land. The act authorized the creation of 80 million acres of grazing districts and the establishment of a U.S. Grazing Service—combined with the GLO in 1946 to form the BLM in the Department of the Interior. In 1935, the title "Chief" of the Forest Service came back into use.

|

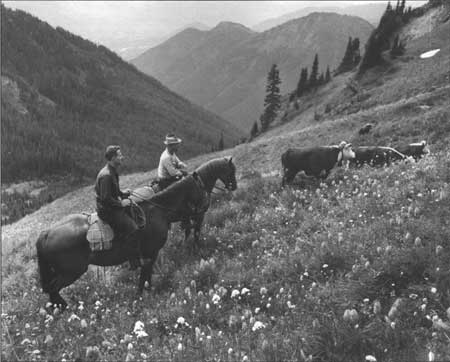

| Ranger and Permittee on an Inspection at the Tatoosh Mountain Range, Gifford Pinchot National Forest (Washington), 1949 USDA Forest Service |

|

During the great "Dust Bowl" of the 1930's on the Great Plains, millions of acres of farm land were literally being blown away. In the dry, rainless condition, soil was lost at a horrendous rate and many farmers and ranchers were forced from their land. Dust and dirt filled the air and sands were drifting across fields, covering fences and houses, and killing animals. By the early 1930's, one of many practices the Great Plains Agricultural Council proposed to slow or halt the damage was the planting of trees to reduce wind and drought-caused soil erosion. In the summer of 1932, then Presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed that the Federal Government begin a program of planting trees in belts across the hardest hit farm lands on the Great Plains. To reduce wind erosion and protect crops from wind damage, millions of trees were planted on private property or "shelterbelts," as they became known. Under Roosevelt's Administration from 1934 to 1942, the program both saved the soil and relieved chronic employment in the region. The Forest Service was responsible for organizing the "Shelterbelt Project," later known as the "Prairie States Forestry Project." The project, headquartered in Lincoln, Nebraska, was directed by Paul H. Roberts from the Research Branch. The Sheltebelt Program included the States of North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and the northern part of Texas. Trees were usually planted in long strips at 1-mile intervals within a belt 100 miles thick. It was felt that shelterbelts at this spacing could intercept the prevailing winds and reduce soil and crop damage. The project used many different tree species of varying heights, including oaks and even black walnut. Shelterbelts, with trees and shrubs of varying heights, could reduce wind velocities on their leeward sides for distances of 15 times the height of the tallest trees. Reduced winds tended to create more favorable conditions for crop growth, reduce evaporation of water in the soil (and thus reduce the need for irrigation), reduce soil temperatures, stabilize soils, protect livestock, increase wildlife populations, and provide a more livable environment for farm families. One of the project's first tasks was to obtain tree and shrub seeds and then to establish nurseries to grow the stock for replanting. Funding for the project almost ended in 1936, but Agriculture Secretary Wallace pushed Congress for a continuation. On May 18, 1937, the Norris-Doxy Cooperative Farm Forestry Act expanded the shelterbelt project by requiring greater Federal-State cooperation. Although Works Progress Administration and Civilian Conservation Corps workers planted the trees and shrubs, landowners were responsible for their long-term care and maintenance. During 1939, the peak year of the project, 13 nurseries produced more than 60 million seedlings. Over the project's duration, over 200 million trees and shrubs were planted on 30,000 farms—a total length of 18,600 miles in all! The shelterbelts worked amazingly well and the results can be seen even today, although many of the shelterbelt trees have been cut for their highly valued wood. Since 1942 tree planting to reduce soil losses and crop damage has been carried out by local soil conservation districts in cooperation with the Soil Conservation Service (now Natural Resources Conservation Service). |

|

Adapted from Terry Wests's From the beginning of European settlement along the eastern and southern coasts of what was to become the United States, domestic livestock has been a prominent part of farming and grazing activities of New World settlers. For many decades, stock animals were free to roam over the unsettled areas along the edge of farm lands newly cleared from the forests. As the settlers moved westward, the size of the unsettled forest area was much reduced and public domain land "taken up" by homesteaders. Controversy soon erupted when cattle interests sought to have sheep and homesteads prohibited from "open ranges" (public domain). Conversely, sheep owners and farmers wanted cattle restricted from grazing and trampling their crops and destroying their water sources. The situation was similar on the public domain timberland, but that changed after forest reserves were created in 1891. Western ranchers were some of the strongest opponents of the creation of the forest reserves because they feared that grazing would be prohibited on them, perhaps rightly so. Concerned with erosion and other problems caused by overgrazing, the Secretary of the Interior banned grazing on Federal forest reserves in 1894. After a rapid growth in cattle ranches in the 1870's and 1880's, the industry had declined so much by the year 1900 that sheep outnumbered cattle in most Western States. The woolgrowers were the West's best organized interest group. The battle of grazing pitted sheep raisers and their supporters in Congress against the Department of the Interior and the cattle ranchers—dependent on upland forest watersheds. Although John Muir (founder of the Sierra Club) referred to sheep as "hoofed locusts," he acknowledged that regulated grazing was better than unregulated grazing. As early as 1896, Gifford Pinchot favored regulated sheep grazing on the forest reserves. Frederick V. Colville's independent study of sheep grazing in the Oregon Cascades during the summer of 1897 left no doubt that regulated grazing was less destructive to the forests than left no doubt that regulated grazing was less destructive to the forests than unregulated grazing—especially to young trees. Pinchot had similar investigations made in the Southwest. The official Federal policy, developed in 1898, allowed restricted sheep grazing in the Oregon Cascades and extended eventually to all the other forest reserves. Cattle and horses were allowed to range freely. In 1900, the Department of the Interior established a free permit system to control the number of animals on the forest reserves and remaining public domain land. Grazing continued the same after the transfer of the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture and the new Forest Service in 1905. In 1906, the Forest Service announced that fees would be imposed: 25 to 35 centers per head of cattle and horses, with a lower rate for sheep and goats. Although free-ranging hogs were a problem in some areas, there was no fees announced for hog grazing. Forest rangers set up new grazing allotments with set dates for entering and leaving the forest reserves. The grazing revenues exceeded those from timber every year between 1906 and 1910, and periodically until 1920. In 1910, the Forest Service established an Office of Grazing Studies, which began studying the effects of grazing on the national forests. In 1917, with the United States' entry into World War I, the number of animals that grazed on the national forests increased dramatically. Grazing was even allowed in Glacier and Yosemite National Parks. Studies of the increasing numbers of sheep and cattle being grazed on national forests during the 1917-1919 period showed severe overgrazing. Range conditions were so poor that sheep permittees were unable to produce the amount of lamb meat that they expected. The issue of carrying capacity of the range was controversial because it determined how many animals a rancher could place on Government land. The bulk of the research on range management took place at the Great Basin Experimental Station (Intermountain Research Station) on the Manti National Forest outside of Ephraim, Utah. Historian Thomas Alexander claimed that professional range management emerged in the Forest Service largely as the result of the Intermountain Station's grazing research staff. The typical district ranger was often concerned about the social and economic costs to local ranchers if they were forced to reduce stock numbers; while range researchers focused on the condition of the land. Over time it was the condition of the land that determined the policy, based on their research findings on carrying capacity. In the end, the numbers of animals on the national forests were reduced, except during World War II. Controversy over grazing fees (which continues to this day) resulted in a 1924 Forest Service report on public and private fees. Stock owners immediately expressed objections to the study, leading to congressional hearings and passage of the McSweeney-McNary Act of 1928, which enhanced research activities on public and private forest and range land. During the Great Depression grazing fees were lowered by 50 percent. The western drought in the early 1930's and the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act of 1934 tightened public land grazing regulations. An interagency rivalry over which agency could best administer and regulate grazing led to the creation of the U.S. Grazing Service in the Department of the Interior to "counter" Forest Service attempts to take over grazing management on all public lands. World War II saw another attempt to expand the number of animals grazing on the national forests. The Forest Service resisted this effort. The Forest Service reduced the number of animals allowed on the national forests in order to increase the quality of the grazing lands. This plan met strong opposition and the controversy resulted in the Granger-Thye Act of 1950. In essence, Granger-Thye recognized the Forest Service's authority to collect fees for grazing privileges and endorsed grazing advisory boards, as long as fees for grazing privileges and endorsed grazing advisory boards, as long as representatives from the State game commissions were members, allowed cooperative range improvements, and allowed 10-year grazing permits to be issued. In the 1960's, controversy was again stirring over grazing fees. By the late 1970's, this resulted in the "Sagebrush Rebellion" in the Western States. Supporters of the Sagebrush Rebellion wanted all Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management grazing lands transferred to the States. They assumed that if such lands were under State control, the ranchers would have more influence and thus get their own way over fees, allotments, and number of animals grazed. Because of local and national opposition, the Sagebrush Rebellion lost momentum, then stalled, and finally died by the mid-1980's only to be revived in the 1990's. This movement today is called the "wise use," "county supremacy," or "property rights movement." |

Wilderness

Robert Marshall, founder of the Wilderness Society and author of the recreation portion of the National Plan for American Forestry (the Copeland Report), worked for the Forest Service in the mid-1930's. He proposed that the Forest Service inventory large unroaded areas that might be suitable for wildernesses or primitive area designation. Shortly before his untimely death in 1939, Marshall and several others made a tour of the western national forests, performing this inventory and making recommendations to regional foresters to greatly increase the number of wilderness and primitive areas.

|

| Bob Marshall Examining Pine and Larch Seedlings, Priest River Experimental Station, Kaniksu National Forest (Idaho) Wilderness Society |

|

Adapted from Terry West's Robert Marshall (1901-1939) was the son of Louis Marshall, one of the Nation's most prominent constitutional lawyers, social reformers, and defenders of the Adirondack State Park in New York. As a young man, Robert Marshall spent his summers at Lower Saranac Lake at his family's estate. His first book, High Peaks of the Adirondacks, was published in 1922. His love of nature and exploration influenced his college studies in forestry. Marshall received his B.S. degree from the New York State College of Forestry at Syracuse University (now called the State University of New York, College of Environmental Science and Forestry) in 1924, then a Masters of Forestry from Harvard Forest (part of Harvard University) in 1925, and a Ph.D. in plant physiology from John Hopkins University in 1930. Bob Marshall worked for the Forest Service at the Wind River Forest Experimental Station near Carson, Washington, during the summer of 1924 as a "field assistant." After earning his masters in forestry degree, he worked for the Forest Service, again, from 1925 to 1928 at the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest Experiment Station at Missoula, Montana. After leaving the Forest Service to earn his doctorate, he again joined the Forest Service in 1932 to 193, working on the recreation portion of the National Plan for American Forestry (the Copeland Report) (1933). In that report, Marshall foresaw the need to place 10 percent of all U.S. forest lands into recreational areas—ranging from large parks to wilderness areas to roadside campsites. In the same year, he became the Director of Forestry for the Office of Indian Affairs, where he supported roadless areas on reservations. In 1937, Bob Marshall returned to the Forest Service as Chief of a new Division of Recreation and Lands in the Washington Office. In his short tenure at the Washington Office, he drafted the "U Regulations" that replaced the "L-20 Regulations" for primitive areas and wildernesses. These regulations gave greater protection to wilderness areas by banning timbering, road construction, summer homes, and even motorboats and aircraft. Marshall checked recreational development plans for the national forests to see if they included access for lower income groups—a very real concern during the Depression years of the 1930's. He also thought that protection should be granted to large areas over 200,000 acres—that they should be reclassified as primitive areas. In 1938, he and others made a trip through the western national forests to map and propose millions of acres of national forest lands for primitive or wilderness status. Marshall was an eccentric and maverick who was famed at the time for both his vigorous 40-mile hikes and radical political opinions. Marshall was famous for his hiking speed—once walking 70 miles in a 24-hour period to make connections for a trip—while at other times easily outdistancing his companions on trips into the mountains. Bob Marshall was a leading writer on the social management of American forests, both public and private, combing conservation with social theory. He, along with Gifford Pinchot, George P. Ahern, and three others, signed a letter in 1930 that recommended increased Federal and State regulation over private forests and transfer of private lands to public ownership and control. For the next 15 years, this issue would be raised by various Forest Service Chiefs, but Congress would not approve. Unable to endure the diplomacy of working within the bureaucracy, he had planned to resign. While on a train from Washington, DC, to New York City, he had a heart attack and died on November 10, 1939. The following year, the Forest Service reclassified and renamed a 950,000-acre area (comprised of three primitive areas) on the Flathead and Lewis and Clark National Forests in Montana as the Bob Marshall Wilderness. A prolific writer, Marshall published a number of articles and pamphlets, as well as several books, including The People's Forests (1933), Arctic Village (1933), and Arctic Wilderness (1956). Marshall was the principal founder and financial supporter of the Wilderness Society in 1935. |

Timber Salvage of 1938

Timber sales, which practically disappeared during the Great Depression, started again just before World War II. Millions of trees were blown down by the Great New England Hurricane of September 1938. The Forest Service directed massive salvage operations on national forest, State, and private lands. More than 50 CCC camps and 15,000 WPA enrollees worked feverishly to salvage the downed trees to prevent insect and disease infestations and prevent fires from starting in the dried trees. During the 3 years that followed, the Northeastern Timber Salvage Administration was able to salvage 700 million board feet of timber.

|

| New England Hurricane Results, New Hampshire, 1938 USDA Forest Service |

Smokejumping and National Defense

Because many of the forest fires in the West were started by lightning in inaccessible locations, the Forest Service experimented with firefighters parachuting to fires before they became large and out of control. The first experimental "jumps" began in 1939 at Winthrop, Washington, on the Okanogan National Forest. By the summer of 1940, the smokejumpers, as they became known, were operating out of Winthrop and the Moose Creek Ranger Station on Montana's Bitterroot National Forest and made their first jump on a fire on the Nezperce National Forest in Idaho. The successful operation proved that smokejumping into remote, rugged areas was feasible. The lessons learned from smokejumper training methods and actually jumping into heavily forested areas would prove useful to the new military paratrooper units like the 101st Airborne during World War II.

National defense became important in the late 1930's and early 1940's. The first conscientious objector camps were established at abandoned CCC camps in 1941. World War II started for the United States on December 7, 1941. In early 1942, the CCC's were disbanded because fewer men were signing up and national attention (and money) was being diverted to the war effort.

|

| Smokejumpers Ready for Experimental Jumps, Chelan National Forest (Washington), 1939 USDA Forest Service |

|

Earle Hart Clapp, born in North Rush, New York, on October 15, 1877, was appointed Associate Chief in 1935, then Acting Chief in 1939 after Chief Silcox died. Clapp was never officially Chief, apparently because President Roosevelt did not want to approve his appointment. Clapp served in this acting capacity until 1943 when Lyle Watts was appointed the Forest Service's seventh Chief. During Clapp's time as Acting Chief, he faced the continuation of the Civilian Conservation Corps projects on the national forests, meeting the need for forest experts to help in the aftermath of the disastrous New England Hurricane, opposing transfer of the Forest Service from the Department of Agriculture to the Department of the Interior, and mobilizing the Nation's forest resources behind the World War II effort. The cutting of national forest timber was stepped up, special studies and tests were made for the armed forests, and forest lookout stations were staffed along both the east and west coasts in 1942-1943 to detect enemy aircraft. Try as he did, Clapp was not successful in supporting Federal regulation of timber cutting on private forest land, adding 150 million acres of mostly cutover land to the national forests, or in alleviating poverty in depressed communities by means of reforestation projects. During his last 2 years, he was responsible for preparing a new appraisal of the Nation's forest situation. Earl H. Clapp wrote:

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec4.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008