|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

THE FULLY MANAGED, MULTIPLE-USE FOREST ERA, 1960-1970

In the early 1960's, a new wave of national concern about the conservation of natural resources began. It resulted in several controversies over the management of the national forests and in the passage of many environmental protection laws.

Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960

The first of the environmental protection laws was the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960. Its purpose was to ensure that all possible uses and benefits of the national forests and grasslands would be treated equally. The "multiple uses" included outdoor recreation, range, timber, watershed, and wildlife and fish in such combinations that they would best meet and serve human needs.

|

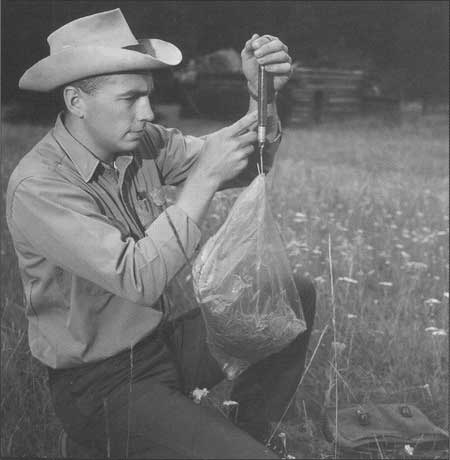

| Wildlife Biologist Bernie Carter Measuring Seed Production, Umatilla National Forest (Oregon), 1964 USDA Forest Service |

This act was necessary because many members of Congress and interest groups felt that the Forest Service was giving too much attention to timber harvesting on the national forests—just 15 years after the huge post-war development push to open the national forests for needed timber to be used in the national housing boom. Multiple-use forestry was in "full-swing," with an increasing emphasis being placed on nontimber resources, while timber production increased to the maximum in the private sector and approached that for the national forests.

|

| Hiker at Indian Peaks Wilderness on the Roosevelt National Forest (Colorado) USDA Forest Service |

In the early 1960's, the family of Gifford Pinchot donated Grey Towers, the family home and surrounding land in Milford, Pennsylvania, to the Forest Service. Extensive stabilization and repair work was needed on the magnificent building. Grey Towers is one of two Forest Service buildings listed as a National Historic Landmark. The other is the Timberline Lodge on the south face of Oregon's Mt. Hood on the Mt. Hood National Forest. The newly formed Pinchot Institute for Conservation Studies was dedicated at Grey Towers by President John F. Kennedy on September 24, 1963. The Pinchot Institute currently resides in Washington, DC.

|

| President Kennedy and Chief Cliff at Pinchot Institute Dedication (Pennsylvania), 1963 |

|

| Oregon Governor Mark Hatfield and Astronaut Water Cunningham Talking During Moon Walks Preparation on Lava Beds, Oregon, Wilamette and Deschutes National Forests USDA Forest Service |

The passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, opposed by the Forest Service as being authorized by MUSY, set the stage for strident antagonism expressed by the old conservation organizations and new environmental groups that would be felt by the Forest Service to this day. One important aspect of the MUSY was the creation of multiple-use planning, which brought a number of new specialists such as soil scientists and wildlife biologists into daily land management decisions.

|

Edward Parley Cliff was born in the tiny community of Heber City, Utah, on September 3, 1909. Serving as Chief from 1962 to 1972, Cliff experienced a decade of rapid change within the agency and around the country. He devoted much time to promoting a better understanding of public forest management problems with grazing interests and the timber industry—and especially with the general public. Public interest in the management of the national forests, as well as demands for numerous forest resources, expanded during this era. He helped the Forest Service develop a long-range forest research program. Important for the national forest recreationists was Cliff's vision of moving the Forest Service into more recreational improvements and programs—caused by an "explosion" in outdoor recreation—hiking, camping, wilderness travel, mountain climbing, and many other national forest outdoor activities. The Wilderness Act of 1964 gave congressional blessing to a new National Wilderness Preservation System and established more than 9 million acres of previously "wild" or "wilderness" areas as the core. The Forest Service hosted the new Job Corps program, which operated over 50 camps on national forest lands. The agency also became involved in the nationwide natural beauty campaign, rural area development, and the war on poverty. Edward P. Cliff wrote: As the population of the country rises and demands on the timber, forage, water, wildlife, and recreation resources increase, the national forests more and more provide for the materials needs of the individual, the economies of the towns and States and contribute to the Nation's strength and well-being. Thus the national forests serve the people. |

|

The Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of June 12, 1960 (MUSY), was the congressional embodiment of 55 years of Forest Service management and policy. The Organic Act of 1897 guided the agency for decades with the management ideas of protection of the forests and water and the production of timber. For the most part, Federal forest management was not controversial during this period, but major changes were on the horizon. Part of the reason for the act was a realization that everyone could not get everything they wanted or needed from the national forests' finite resources. Even an equal balancing act between the available natural resources was not possible. By the mid-1950's, the first inkling of a shift in management philosophy came with the congressional debates about multiple-use bills. The first was introduced by Senator Hubert H. Humphrey of Minnesota. Basically, there was a growing concern that in the decade of rapid development of the national forests since the end of World War II, the Forest Service was learning so much toward managing of timber that other resources, especially recreation, were getting short shrift. Initially, the Forest Service was opposed or neutral to a multiple-use bill. However, the Forest Service was beginning to feel the heat from growing opposition to its policies about logging in or near recreation sites. One focus of this contention was in California's Deadman Creek area. The 3,000-acre site contained a stand of old-growth Jeffrey pine. When the Forest Service announced plans to do "sanitation salvage" in the area, reaction was swift and allegations were made that the recreation and scientific values were being ignored for the timber value. Similar conflicts arose in many parts of the West. By the late 1950's, the conservation groups generally supported the Humphrey bill, with the exception of the Sierra Club, which felt that support of the multiple-use bill would jeopardize its efforts to pass a wilderness bill. During the spring of 1960, agreements were made with various groups to clarify wording in the act so that timber would not dominate, that recreation would be equal to other resource uses on the national forests, and that the Organic Act of 1897 would only be supplemented, not replaced. After the act was signed in 1960, the Forest Service was active in managing the national forests where all resources (timber, wildlife, range, water, and outdoor recreation) were treated equally. Many rangers did their utmost to embody the principles of multiple use into their management. For some, however, the act simply redefined what the Forest Service had been doing for decades. Timber harvesting and road construction. Many people outside the agency saw that forests were not managed any differently under MUSY—it was still just a road leading to an ugly clearcut. This example of redefinition of the old ways was rather than managing differently on the ground had implications for the forest management controversies of the 1970's, 1980's, and 1990's. The passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, opposed by the Forest Service as being authorized by MUSY, set the stage for strident antagonism expressed by the old conservation organizations and new environmental groups that would be felt by the Forest Service to this day. One important aspect of the MUSY was the creation of multiple-use planning, which brought a number of new specialists such as soil scientists and wildlife biologists into daily land management decisions. |

Work Programs

In 1963, the Forest Service became involved with the Accelerated Public Works (APW) program that was designed to put unemployed men (there were still no women on these projects) to work on projects to develop or improve national forest resources. The 1963-64 program provided immediate work for over 9,000 men on more than 100 national forests in 35 States. It also brought increased business to many communities adjacent to national forests—providing much-needed boosts to their economies. APW projects included working on camp and picnic areas; planting trees; thinning timber stands; improving fish and wildlife habitat; and constructing or improving roads, trails, fire lookouts, and other facilities.

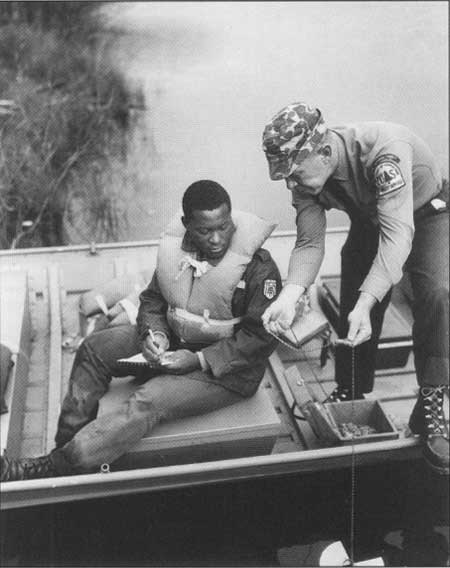

A new work program for young, unemployed youth began in 1964 and was called the Job Corps. The Job Corps was designed to give young men (young women were admitted later) from deprived backgrounds basic schooling, training in skills, and valuable job experience before they returned to their home communities. It resembled the older CCC program of the Great Depression—participants were involved in firefighting, community work, building construction, and forestry activities on the national forests. In 1989, the job Corps program celebrated its 25th anniversary, having served more than 1.4 million youths.

|

| Ojibway Job Corps Enrollee and Ottawa National Forest Fish Biologist Taking Water Samples, Ottawa National Forest (Michigan), 1967 USDA Forest Service |

|

| John Muir Wilderness, Sierra National Forest (California), 1963 USDA Forest Service |

Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Acts

After years of struggle, the Wilderness Act of 1964 was signed into law. This unique law established a National Wilderness Preservation System of more than 9 million acres—incorporating the existing Forest Service wilderness areas and creating several new ones. One provision in the Wilderness Act called for evaluation of any national forest areas that were without roads (hence the name "roadless areas") that might be considered for future wilderness status. In 1967, the Forest Service undertook a Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) to identify and study these "de facto wildernesses."

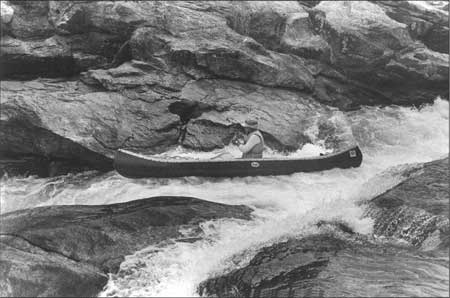

The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act of 1968 authorized a number of important, distinctive rivers to be classified as wild, scenic, and recreational. Today, the Forest Service manages more than 4,000 miles of such rivers on nearly 100 rivers or river segments.

|

| Canoeing on the Wild and Scenic Chattooga River, Sumter National Forest (South Carolina), 1986 |

|

Passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964 involved decades of work on the part of many people both inside the Forest Service and from a variety of interest groups. As early as the 1910's and 1920's there were several important proponents of wilderness designation in the national forests. Three men are considered pivotal in these early year and all were Forest Service employees: Aldo Leopold, Arthur H. Carhart, and Robert Marshall. Their efforts were successful at the local level in creating administratively designated wilderness protection for several areas across the country. At the national policy level, there was a series of policy decisions (L-20 and U Regulations) in the 1920's and 1930's that made wilderness and primitive area designation relatively easy, but what was lacking was a common standard of management across the country for these areas. Also, since these wilderness and primitive areas were administratively designated, the next Chief or Regional Forester could "undesignate" any of the areas with the stroke of a pen. Howard C. Zahniser, executive secretary of the Wilderness Society (founded by Bob Marshall), became the leader in a movement for congressionally designated wilderness areas. As early as 1949, Zahniser detailed his proposal for Federal wilderness legislation in which Congress would establish a national wilderness system, identify appropriate areas, prohibit incompatible uses, list potential new areas, and authorize a commission to recommend changes to the program. Nothing much happened to the proposal, but it did raise the awareness for the need to protect wildernesses and primitive areas from all forms of development. In 1955, Zahniser began an effort to convince skeptics and Congress to support a bill to establish a National Wilderness Preservation System. He sought to rally public opinion through writing in The Living Wilderness and other publications, as well as organizing many talks to citizen groups across the country. Drafts of a bill were circulated the next near. By the late 1950's, it seemed that the wilderness bill would eventually become law, but there were still many legislative battles to be fought. At the same time, the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act (MUSY) was also being pushed through Congress. Some have suggested that the Forest Service strongly supported MUSY to counteract the wilderness legislation. After the passage of MUSY in 1960, there were also many who felt that there was no need for a separate wilderness bill because wilderness was one of the many multiple uses allowed in the act. Senator Hubert H. Humphrey (D-MN) became a major supporter of the wilderness bill, but State water agencies, and mining, timber, and agricultural interests were very much opposed. The Forest Service and, ironically, the National Park Service were also both initially opposed to the bill. The wilderness bill, which was stalled for several years in Congress, finally came out of committee with a compromise that allowed mining in national forest wilderness until 1984. Ironically, Howard Zahniser, who pushed so hard for the act, died on May 5, just a few months before the bill became law. Doug Scott, policy director of the Pew Wilderness Center recalled Howard's last days. "Zahnie [as he was affectionately known] wasn't there to see it [the wilderness bill]...Just 2 days after testifying at [the final congressional hearing], Zahnie died at the age of 58...But, his widow, Alice, and Olaus and the incomparable Mardy Murie stood at Lyndon Johnson's side when the wilderness law was passed." President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill into law on September 3, 1964. Because of Zahniser's relentless efforts, he has often been called the "Father of the Wilderness Act." The act designated 9.1 million acres of wilderness, mostly from national forest lands. Overnight, all of the existing Forest Service wildernesses became part of the National Wilderness Preservation System. A team of Forest Service wilderness managers met soon afterward in Washington, DC, to come up with implementing regulations for these new congressionally established wildernesses. What they thought would be an easy task took many months as they found that there were no consistent or agreed-upon ways to manage the existing wildernesses. Part of the Wilderness Act of 1964 also set up procedures to evaluate existing primitive and roadless areas for possible inclusion into the wilderness system. For the next 20 years, the roadless areas reviews (RARE and RARE II) would play an important and controversial role in Forest Service management of the national forests. |

Using Litigation To Settle Disputes With the Forest Service

A controversy erupted in the mid-1960's in the Sierra Nevada mountain range of California. Walt Disney Enterprises proposed a ski development on the Sequoia National Forest that was designed to make the Mineral King area a destination resort. Several organizations fought the development, which would also have affected the nearby Sequoia National Park. A lawsuit was filed by the Sierra Club (Sierra Club v Morton), but the organization eventually lost the case, yet it set precedent that organizations could use litigation in settling disputes with the Forest Service. The ski area was never developed.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec7.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008