|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

THE ENVIRONMENTALISM AND PUBLIC PARTICIPATION ERA, 1970-1993

There was growing, widespread public concern that new laws and regulations were needed to preserve and protect the environment. Several of these laws derived from a new environmental awareness brought about by Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring in 1962, which documented the overuse of pesticides, especially DDT. The use of chemicals, such as herbicides and pesticides, came into contention on the national forests, leading to numerous demonstrations, lawsuits, and occasional violence by those in favor and those opposed. These controversies led the Forest Service to reconsider many of the agency's land management practices.

|

| Public Participating in Forest Planning, 1989 USDA Forest Service |

National Environmental Policy Act of 1969

The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA), signed into law January 1, 1970, mandated that environmental impacts of proposed Federal projects be comprehensively analyzed. An important part of the act made it mandatory that agencies seek public participation on projects, from the planning stage to the review-of-documents stage. These requirements were quickly incorporated into the many projects that were underway on the national forests. Earth Day on April 22, 1970, foreshadowed the beginnings of a new and fundamentally different conservation-environmental movement.

|

On January 1, 1970, President Richard M. Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA)—the culmination of years of struggle by special interest groups and the authors of the act—Senator Henry M. Jackson and Congressman John D. Dingle. The act required that an environmental impact statement (EIS) be prepared when any Federal agency proposed a "major Federal action significantly affecting the quality of human environment." The bill had not provoked any major controversy in Congress, and it only received cursory comment from legal journals and the public. But it was to have profound implications for every Federal land management agency. NEPA established a three-member Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) as a part of the Executive Office of the President. The CEQ is required to assess the Nation's environmental quality annually and review all Federal programs for compliance with NEPA. Section one of NEPA states that the Federal Government's policy will be "to use all practical means—to create and maintain conditions under which man and nature can exist in productive harmony and fulfill the social. economic and other requirements of present and future generations of Americans." The NEPA requirement for producing EIS's on major Federal projects was felt to be the minimum necessary to describe all the planned activities, alternatives to each proposed action, and consequences of implementing each alternative to the affected Federal agencies and the public. Provisions of the act, as well as its implementing regulations, recquire public involvement, opportunities for the public to comment, and the agency's responses to these comments in the EIS. After more than 25 years of NEPA, Federal agencies have published thousands of EIS's running from a few pages to many volumes on environmental projects. NEPA's driving force today is through the EIS process. While some have criticized the NEPA process as long and costly, its public involvement and participation have resulted in more informed decisions and agencies now employ new natural resource specialists to help the agency and the public understand the implications of its decisions on the natural and human environments. Court challenges to Federal decisions have caused an increase in litigation. From the standpoint of special interest groups, NEPA has been both a burden and a godsend: A burden in terms of cost and time for project startup and a godsend in terms of better decisions based on expected consequences and impacts. NEPA has opened a whole new avenue for citizen involvement in Federal land management planning and decisionmaking. The NEPA process has been so successful that processes patterned after it are being used in other countries such as Australia and the Philippines. |

Controversies Over Clearcutting

Although intensive forestry and protection of the land had taken on even more importance with the adoption of many new forest practices and procedures, certain intensive forestry practices became a problem. In the late 1960's, a controversy developed over the management of Montana's Bitterroot National Forest, when residents became concerned about the scenic and reforestation problems being caused by clearcutting and terracing on steep slopes. In 1970, Montana's Senator Metcalf called on Arnold Bolle, Dean of the Forestry School at the University of Montana, to investigate the allegations and prepare a report. Bolle's committee report was critical of Forest Service operations, which was consistent with several internal reports by the regional office in Missoula.

|

| Aerial Spraying USDA Forest Service |

|

| Skycrane with Logs, Willamette National Forest (Oregon) USDA Forest Service |

On the other side of the country, a legal decision against the Forest Service for clearcut logging on the Monongahela National Forest (Izaak Walton v. Butz) called the interpretation of the Organic Act of 1897 into question. The results of this legal decision caused an extensive review of forest management by the Forest Service and later by Congress in 1972. Congressional bearings would later set the stage for the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA).

|

Clearcutting (felling and removing all the trees from a specific area) has been a long-standing technique used extensively in the United States and most other countries. During the late 1800's and continuing through today, many people opposed to logging, in general, have focused on clearcutting. It has also been the focus of intensive discussion about the proper method to harvesting trees for their wood. It was at George Vanderbilt's Biltmore Forest Estate (now part of the Pisgah National Forest) in the 1890's that Gifford Pinchot first harbored ideas about "new forestry"—clearcutting vs. selective logging and leaving young trees standing during harvesting, as recounted in Pinchot's 1947 autobiography Breaking New Ground: "The old way of lumbering at Biltmore, and everywhere else, was to cut out all the young growth that would interfere with cheap and easy logging, and leave desolation and a firetrap behind...We found that large trees surrounded by a dense growth of smaller trees could be logged with surprisingly little injury to the young growth, and that the added cost of taking care was small, out of proportion, to the result. To establish this fact...was of immense importance to the success of Forestry in America." Thus from the beginning of professional forestry in America, there was concern about logging methods that involved both ecology and economics. The first major controversy involving clearcutting erupted in the Adirondacks of New York State in 1900-03. As the Cornell Demonstration Forest, Bernhard Fernow, chair of the Cornell School of Forestry, intended to convert the broadleaf forest into a conifer forest. The Adironacks case came under public scrutiny, with Fernow eventually losing his position at Cornell as a result of the controversy, and the school of forestry closing. During the 1910's and 1920's, clearcutting was emphasized as the most desirable method of logging on national forests. As most logging operations were then either railroad or river log drives, the clearcutting decision was practical for the timber purchaser. At the time, huge blocks of national forest were sold to timber companies with the idea that extracting the standing timber from a watershed would take decades. But there were researchers, especially in the dry pine forests and elsewhere, who were advocating selective logging. In October 1934, after reviewing several research studies, Regional Forester C.J. Buck directed the national forests of western Oregon and western Washington to begin timber harvesting by selective logging, rather than by clearcuting in Douglas-fir areas. Basically, there was a fundamental disagreement among Forest Service and academic researchers over the clearcutting issue. Two University of Washington forestry professors, Burt P. Kirkland and Axel J.F. Brandstorm, argued that "selective timber management" was economically advantageous as loggers did not have to take every tree and that selective logging did not lay the landscape bare. Forest Service researchers Leo Isaac and Thornton T. Munger, however, argued that selective logging was a short-term economic gimmick used during the Depression that would, in the long run, deplete the forests as only the prime trees would be taken from a stand, leaving the less desirable species on site. They also argued that selective logging practices damaged the trees that remained on the site and that clearcutting was much better. The selective logging method was used in the Pacific Northwest Region Douglas-fir area until the early 1940's, when C.J. Buck was forcibly transferred to the Washington Office and the policy changed to clearcutting. Research work continued in the Pacific Northwest and by the early 1950's there was enough evidence to convince most professional foresters that clearcutting was the most desirable method to harvest trees in the Douglas-fir region. These data were compelling from both the economics standpoint and the ecological standpoint that the seedlings required direct sunlight to grow. However, the research work overlooked several important aspects or consequences of clearcutting. The visual disruption of the forest for at least a decade until the young trees grew tall and the aspect of having a monoculture of genetically similar trees. Even "hiding" clearcuts behind a row of standing tall trees and an effort to "educate" the public to the advantage of clearcutting did not overcome the ill feelings toward this method of tree harvesting. Many people, then and now, believe that clearcutting is of economic advantage, rather than an ecological or tree regrowth necessity. In the late 1960's, Montana's Bitterroot National Forest, in a burst of timber harvesting in response to the national needs for wood, began clearcutting then terracing the cutover steep slopes for better seedling regeneration. This caused a controversy. The Bitterroot's retired Forest Supervisor led protests, the Missoulian carried a series of news articles, and Senator Metcalf commissioned a University of Montana Study team to study the alleged mismanagement. The university team—led by Arnold Bolle, dean of the school of forestry—was instrumental in bringing the Bitterroot's clearcutting issue to national attention. Another clearcutting controversy on West Virginia's Monogahela National Forest contributed significantly to the management debate. The Izaak Walton League, an outdoor and fishing organization, filed a lawsuit on behalf of several turkey hunters, on the premise that the 1897 Organic Act did not allow clearcutting. In 1973, the Federal District Court ruled against the Forest Service. After the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals also ruled against the agency in August 1975, the Forest Service and Congress decided that something had to be done to change the old law to allow timber harvesting. These two battles resulted in a series of congressional hearings over clearcutting and forest management in general. Senator Frank Church of Idaho offered an analysis report on clearcuting that resulted in the "Church Guidelines" for limiting the size of clearcuts. The Forest Service voluntarily agreed to stay within the guidelines. Clearcuts would not exceed 40 acres. The final result of the controversy was passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA). The problems with clearcutting have persisted. The Forest Service is still trying to back away from this controversial method. In 1992, the Chief of the Forest Service proposed a policy, with seven criteria, that would eliminate clearcutting as a standard practice and reduce clearcutting by as much as 70 percent from the 1988 level. However, backlash from environmental groups and the timber industry continue to make headlines over clearcutting and this policy. Ivan Doig in his classic 1975 article: "The Murky Annals of Clearcutting" wrote: "Professional foresters were honestly disagreeing about silvicultural alternatives, but mostly on economic grounds...All in all, [it should]...serve as a classic lesson that disputes over the use of our forests are not going to be decided on ecological merit alone. Nowhere near it." |

Youth Conservation corps, Young Adult Conservation Corps, and Related

Programs

In 1970, a 3-year pilot Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) program began—it became fully established in 1974. It was designed to further the development and maintenance of natural resources by America's youth between the ages of 15 and 19. The young male and female YCC members, from all parts of the country and all walks of life, spent the summer months working on conservation projects on the national forests.

|

| YCC Members Prepare a Lake Area for Public Use USDA Forest Service |

|

| Woodsy with Children USDA Forest Service |

During 1977, another new youth employment program arrived—the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC). This program was intended to further the development and maintenance of natural resources by America's young adults (both male and female) between ages 16 and 23. The Forest Service provided many opportunities for enrollees to work on important projects on the national forests. This program was short-lived because its funding was eliminated in 1981.

Woodsy Owl, the symbol of antipollution and wise use of the environment, was introduced in 1971 with the slogan "Give a Hoot, Don't Pollute." Just as with Smokey Bear, the Woodsy symbol and slogan are protected by law except as authorized for antipollution programs. In 1997, Woodsy's image was updated and his message became "Give a hand, Care for the Land."

In 1971, the President signed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act that authorized the transfer of 44 million acres of land in Alaska from the Federal Government to various Alaska Native corporations in exchange for the Natives extinguishing aboriginal title to the remaining lands Alaska Natives traditionally used and occupied.

|

John Richard McGuire was born on April 20, 1916, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. While serving as Chief from 1972 to 1979, McGuire made changes to strengthen State and Private Forestry's and Research's role in implementing the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA) of 1974 and the National Forest Management Act (NFMA) of 1976. McGuire faced increasing opposition for forestry practices being carried out on the national forests. Most notable were the congressional hearings over clearcutting on the national forests—a result of controversies on Montana's Bitterroot National Forest and on West Virginia's Monogahela National Forest. McGuire was instrumental in requiring the Forest Service to review, and then change, forest management practices and modify and integrate its methods of land management. Major issues facing Chief McGuire were the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) and RARE II decisions; mounting controversy over the management of the national forests; new congressional direction that mandated planning at the forest, region, and national levels through RPA and NFMA; and special interest groups' increased reliance on litigation to influence the management of the national forests. John R. McGuire wrote:

|

National Forest Volunteers

The Volunteers in the National Forests Act of 1972 authorized the Forest Service to recruit and train volunteers to help manage the national forests. A highly successful and visible program, many of the volunteers are retired people who enjoy working outdoors and with the public in a wide variety of capacities ranging from being campground hosts to assisting with archaeological digs.

|

| Volunteer Helping Hikers, Sumter National Forest (South Carolina), 1986 |

|

| Senior Community Service Employment Program Enrollee Uses a Dado for a Sign on the Colville National Forest (Washington) USDA Forest Service |

RARE and RARE II

As the Wilderness Act of 1964 provided, the draft Roadless Area Review and Evaluation (RARE) report was completed in 1972. This controversial wilderness review process evaluated some 55.9 million acres of land and 1,449 roadless areas for possible inclusion into the National Wilderness Preservation System. The final report was published in 1973, with 274 of the roadless areas (12.3 million acres) selected for possible wilderness designation by Congress. The decision became immediately embroiled in controversy. A lawsuit in California over a roadless area that had not been selected resulted in the Assistant Secretary of Agriculture and the Chief of the Forest Service ordering a new study of all roadless areas, called RARE II, in 1977.

|

| French Pete Drainage Wilderness Controversy, Willamette National Forest (Oregon) USDA Forest Service |

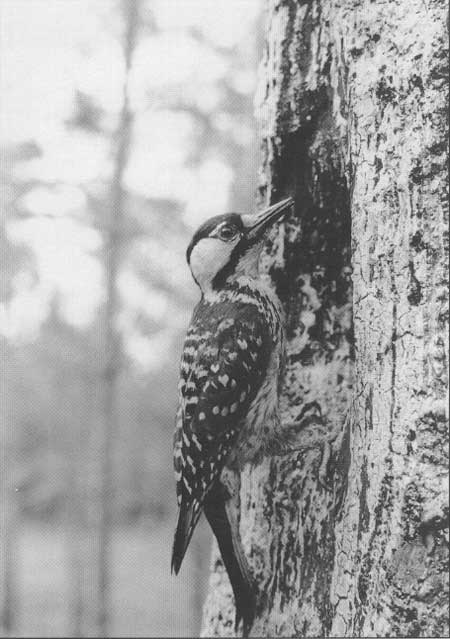

Endangered Species Act of 1973

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 provided for protection of rare, threatened, and endangered animal and plant species. It established Federal procedures for identifying and protecting endangered plants and animals in their native, critical habitats. It declared broad prohibitions against taking, hunting, harming, or harassing the listed species. The intent of the act was to restore endangered species to levels where protection would no longer be needed. Implementing this act would have drastic consequences on the management of national forest timber and road construction programs during the 1980's and 1990's.

|

| Northern Spotted Owl USDA Forest Service |

National Forest Planning

The early to mid-1970's saw a continued major national forest planning effort under the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act of 1960. By the mid-1970's, unit plans (ranger district level) and several forest plans were being developed. Many national forests created planning teams to assist in the multiple-use planning of their many resources. New Forest Service specialists were hired because of the planning needs—wildlife biologists, soil scientists, landscape architects, and hydrologists.

|

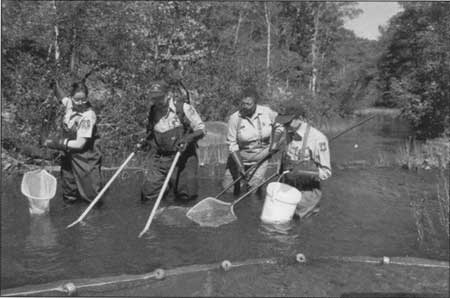

| Monitoring Fish Populations, Ouachita National Forest (Arkansas) USDA Forest Service |

In 1974, the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act (RPA) became law. The act provided that beginning in 1976, the Forest Service would develop a program or assessment every 5 years that outlined the proposed expected national forest production of various resources. With the RPA program in hand, the Forest Service would go to Congress to obtain the necessary funding to implement its program. This act represented Congress's first legislative recognition that management of our natural resources could only occur with long-range planning and funding—not planning and funding on a year-to-year basis.

|

| Hydraulic Monitor Mining Nozzle USDA Forest Service |

|

| Clearcutting Patterns on the Shelton Ranger District, Olympic National Forest (Washington), 1957 USDA Forest Service |

The Bolle Report (about Montana's Bitterroot National Forest) and a court decision against the Forest Service in the Monongahela National Forest clearcutting case spawned the NFMA. The NFMA amended RPA and also repealed major portions of the Organic Act of 1897. NFMA mandated intensive long-range planning for the national forests—the most comprehensive planning effort in the western world. NFMA specifically incorporated public participation and advisory boards, various natural resources, transportation systems, timber sales, reforestation, payments to States for schools and roads, and reporting on the incidence of Dutch elm disease.

A committee of scientists created NFMA'S implementation regulations, which became final in 1979, and an intensive new forest planning effort began. The Forest Service hired many new specialists, many of them women, to address the various provisions of NFMA—including public affairs specialists, economists, archeologists, sociologists, geologists, ecologists, and operations research analysts. The Forest Service also began an extensive public involvement effort to prepare the new plans. In 1997 and 1998, a new committee of scientists met to evaluate and recommend changes to NFMA and the revised forest planning regulations.

|

| Regional Forester Dick Worthington at RARE II Press Conference, Pacific Northwest Region (Portland, Oregon), 1979 USDA Forest Service |

In the late 1970's, RARE II once again launched the Forest Service into the public arena. The draft RARE II report, published in 1978, led to many public demonstrations and letter-writing campaigns. The final RARE II report, published in January 1979, recommended that Congress add 15 million acres (only 12.3 million acres were recommended in RARE) to the National Wilderness Preservation System. However, roadless decisions and wilderness legislation would have to wait until Congress acted. Today after a series of congressional acts that established new wildernesses, the Forest Service manages over 35 million acres of wilderness. This is approximately 18.4 percent of the entire National Forest System.

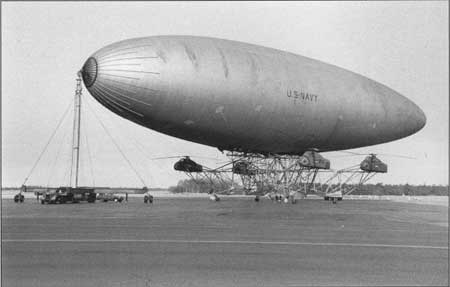

Bidding for national forest timber reached an all-time high in 1979 and 1980, just before a wood-products "depression" hit the timber industry. Because of very high interest rates, the new-home market became very depressed, with the demand and price for lumber products falling to almost record lows. Timber companies could not economically harvest the timber they had purchased at high prices. Nationally a number of timber companies struggled, some going bankrupt, until the economy picked up in the mid- to late-1980's. The Forest Service experimented with a lighter-than-air balloon and tethered helicopter mix, which was referred to as a "helistat," to transport logs from remote areas. After many attempts, the effort failed.

|

| Experimental Helistat Balloon with Four Helicopters, Oregon USDA Forest Service |

|

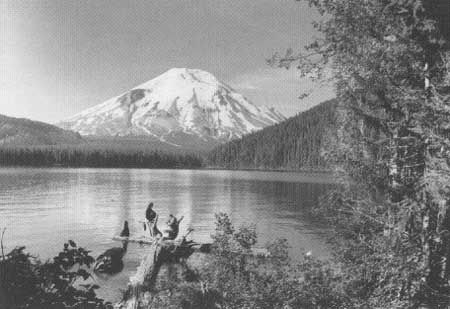

| Mount St. Helens Before and During the May 18th Eruption, Gifford Pinchot National Forest (Washington), 1980 USDA Forest Service |

In the late 1970's and early 1980's, the illegal growing of marijuana on the national forest lands caused numerous management problems. Many of the national forests responded to this problem and other lawlessness by hiring law enforcement specialists, who have worked closely with other Federal, State, and local authorities.

In the Pacific Northwest, Mount St. Helens on Washington State's Gifford Pinchot National Forest rumbled to life with a huge volcanic explosion on May 18, 1980, that sent ash around the world. President Jimmy Carter visited the Forest and was instrumental in establishing the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument in 1982.

The Forest Products Laboratory designed a new strong, lightweight system for wood construction. Called the timber truss-frame, the system has been widely used by the home construction industry since the 1980's.

|

| Forest Products Laboratory's Timber Truss-Framed Construction USDA Forest Service |

|

Congressional hearings began in the early 1970's on the clearcutting controversies on the Bitterroot and Monogahela National Forests, as well as a Federal court decision over the Organic Act of 1897. By the mid-1970's, arguments in Congress revolved around how specific any new law should be to direct the Forest Service in the management of the national forests. Some members wanted broad statements that would give land managers discretionary authority that would cover any possibility, others wanted language to mandate specific actions on the ground. In 1989, former Chief R. Max Peterson would say: "It became obvious to most that neither Congress nor anyone else could possibly write management prescriptions that would fit the many physical situations on national forests... This led to a recognition that the legislation would have to set forth a process rather than specify answers." NFMA was signed into law on October 22, 1976. NFMA amended Resources Planning Act of 1974 (RPA) to provide a comprehensive blueprint for managing the national forests. One of the NFMA's provisions was that the Secretary of Agriculture appoint a committee of scientists—not officers or employees of the Forest Service—to provide scientific advice and counsel on how to implement its intent. It took almost 3 years for these implementing regulations to become final. The regulations required the beginning of a long-range planning process for each national forest. Other NFMA requirements mandated public involvement in the planning process, a redefinition of sustained and nondeclining yield, and clearcutting, which the act defined as an acceptable practice. Another requirement was to "preserve and enhance the diversity of plant and animal communities...so that it is at last as great as that which would be expected in an natural forest." NFMA also gave full statutory status to the National Forest System—many of the national forests had been established in a series of Presidential proclamations from 1891 to 1907. An act similar to NFMA was passed and signed into law for the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). This 1976 act, the Federal Land Policy and Management Act, has similar provisions requiring long-range planning on the BLM-administered lands. In 1998, a second committee of scientists was formed to rewrite the NFMA regulations, which were felt by many to be outdated. The committee recommended many changes to the regulations. Draft regulations were announced in the summer of 1999, along with a public review period. The final regulations were printed in 200. |

|

The first nonforester Chief since Gifford Pinchot, Ralph Max Peterson was born near Doniphan, Missouri, on July 25, 1927. Peterson was the first engineer to hold the position. He served as Chief from 1979 to 1987, during a time of increasing turmoil and criticism of the Forest Service. Major accomplishments during this era were establishing regulations for implementing the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA), dealing with the aftermath of the RARE II decision, addressing the "timber depression" and housing slump of the early 1980's, responding to a rapidly rising concern about the use of herbicides and pesticides on the national forests, supporting various wilderness bills before Congress, addressing a growing concern about the logging of old growth and below-cost timber sales (especially Alaska), and developing ways to meet the needs of threatened and endangered species. Agency funding was reduced, which resulted in a substantial reduction in the number of employees. Although the public's trust that the Forest Service could effectively manage the national forests fell because of multiple issues, Peterson was able to oversee the changing management of the national forests during these trying times. R. Max Peterson write:

|

|

| Geri B. Larson, First Woman Forest Supervisor |

Internal Struggles

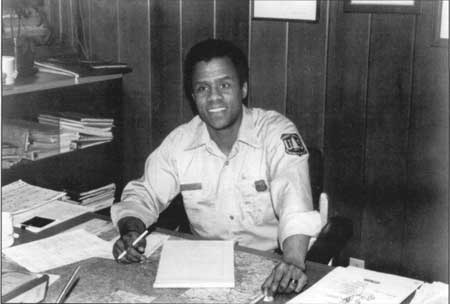

A sex discrimination lawsuit against the Forest Service's Pacific Southwest Region (California) resulted in a 1980 "consent decree." The decree accelerated advancement of women and minority employees to management and line officer positions. In 1985, Geri B. Larson was named the Forest Supervisor of the Tahoe National Forest in California—the first female forest supervisor in Forest Service history.

|

| Charles "Chip" Cartwright, First Black District Ranger on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest (Washington), 1983 USDA Forest Service |

|

| Forester Lea Dotson Examines New Growth on Loblolly Pine, Sumter National Forest (South Carolina), 1986 USDA Forest Service |

Budget cuts in the mid-1980's reduced the number of Forest Service employees and eliminated a number of positions that were created in the late 1970's. In the 1990's, reducing the national deficit became a priority of the Clinton administration. There have been several attempts over the years to reorganize the agency but little came of them. The most recent attempt was to revamp most of the regions, as well as to reduce the organizational complexity and number of employees. The reorganization of the regions was not accomplished because of congressional opposition, while other aspects were implemented. Today the Forest Service has around 28,100 permanent employees, down from 35,400 in 1992.

Much of the long-range land and resource management planning was placed in the hands of forest specialists. Public controversy erupted over the management requirements for wildlife, water and soils, old-growth timber, disposition of remaining roadless areas, road construction costs, and below-cost timber sales in the NFMA planning process. The Forest Service made a decision in the early 1980's to use a particular linear programming model, FORPLAN, on each national forest for the new forest planning effort. The Forest Service adopted the Data General computer system, which electronically linked all agency locations—Washington Office, research stations, regions, national forests, and ranger districts. It has recently adopted an IBM/UNIX-based system to replace the Data General.

|

| Regional Forester James Torrence Using the Data General Computer System, Pacific Northwest Region (Oregon) USDA Forest Service |

Beginning in 1984 with the Oregon and Washington Wilderness Acts, which contained much-sought-after "release language" for remaining roadless areas, a number of State-by-State wilderness bills passed Congress (16 additional Statewide wilderness bills were passed in 1984). Still long awaited are wilderness bills for the important States of Idaho and Montana, which contain millions of acres of unroaded lands.

In 1985, to stall the so-called "Sagebrush Rebellion," the Reagan Administration proposed that the Forest Service and the BLM interchange certain lands in the West for ease of management. This proposal aroused great public outcry even after a major revision, and was tabled by Congress. In the 1990's the new "Wise Use" or "Property Rights" or "County Supremacy" movement replaced the Sagebrush Rebellion. County commissioners in Nye County Nevada, and Catron County New Mexico, have put new emphasis on local control over Federal land. There have also been a rash of bombings and threats to Forest Service facilities and employees. However, following the Oklahoma City bombing, this violent extreme has seemingly cooled.

|

F. Dale Robertson was born in Denmark, Arkansas, on July 17, 1940. Soon after his appointment as Chief in 1987, Robertson had to face a public wary of everything the Forest Service had to say or proposed to do. Especially troubling was the growing controversy about the harvest of old-growth timber (ancient forest) tree in the Pacific Northwest and the protection of several species of animals and plants fell under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. He appointed several task forces to consider all options, but when the decisions were made, they did not satisfy everyone. Several new resource programs were developed under Robertson's leadership, including the highly successful "Rise to the Future," a program designed to enhance the production of fish on the national forests. Robertson led the Forest Service's effort to find new and creative ways to manage the national forests especially by emphasizing the noncommodity (nontimber) resources, new forestry, new perspectives, and the new era of ecosystem management. Robertson, and his Associate Chief, George Leonard, were reassigned from the Forest Service to the Department of Agriculture on October 29, 1993, after they faced increasing criticism by the Clinton Administration that the Forest Service was not changing fast enough. F. Dale Robertson wrote:

|

Owls and Other Wildlife

There has been growing public concern over unique wildlife, several species of which were threatened or endangered, that lived or nested on national forests around the country. In the West, spotted owls, marbled murrelets, grizzly bears, caribou, Pacific salmon, and wolves caused concern, while Texas and the Southeast were concerned about the red-cockaded woodpecker. Other regions have different species of wildlife and plants that are unique to certain areas. In 1987 and 1988, various environmental groups sought to have the spotted owl listed with the Department of the Interior's U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as a threatened or endangered species. A judge later declared that the Fish and Wildlife Service had not provided sufficient information about its decision not to list the bird. Subsequently the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared its intent to restudy the issue, and in June 1990, it declared the spotted owl threatened in western Washington, western Oregon, and northern California.

Other plant and animal species inhabiting the national forests have joined the spotted owl as species to be considered for threatened or endangered status. Considerable controversy has arisen over the reintroduction of the wolf into the Yellowstone ecosystem. Other concerns have been expressed over many animal and plant species in various parts of the national forests, including the bald eagle, peregrine falcon, eastern timber wolf, Puerto Rican parrot, Mount Graham red squirrel, steelhead trout, bull trout, and other species.

|

| Red-Cockaded Woodpecker USDA Forest Service |

|

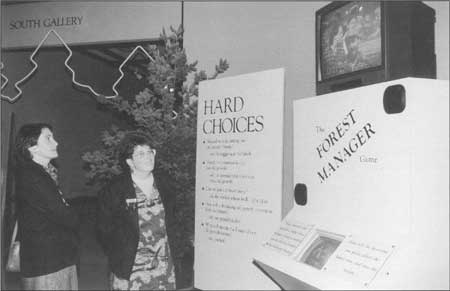

| Visitors at Old Growth Exhibit "Playing" the Forest Manager Game, 1991 USDA Forest Service |

The latest round of forest planning, in which every Forest Service region and national forest developed comprehensive, NFMA directed forest plans, was basically completed by the end of 1990; however, numerous appeals and lawsuits by the timber industry and environmental and other groups have delayed the implementation of many of these plans. On some national forests, appeals and lawsuits have been successfully resolved through a negotiation process in which the contending parties sat down and discussed options and eventually came to an agreement.

|

Adapted from Terry West's Interest in wildlife was an important part of the conservation movement in the late 19th century. Although wildlife did not have the economic importance of other resources such as timber, forage, and water, nor did it capture the public's attention as much as efforts to preserve scenic waterfalls or geysers, big game species were perhaps the most endangered resource of that period. Reformers such as George Bird Grinnell, founder of Field and Stream magazine, and Theodore Roosevelt, a cofounder of the Boone and Crockett Club, were alarmed by the fate of big game in the Western States. When Roosevelt sponsored Gifford Pinchot for membership in the club, Pinchot was able to expand the notion of forest conservation to embrace the cause of big game protection. Yet, when the Federal forest reserves were transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture in 1905, the Forest Service apparently did not see much of a relationship between national forest administration and wildlife. An emphasis on timber resources set the future tone of the agency. Moreover, the agency had to be cautious about regulating game animals and birds on the forest reserves (which were renamed national forests in 1907) for fear of trampling States rights and giving its western critics reason to disband the reserves. The policy of the Forest Service was to "cooperate with the game wardens of the State or Territory in which they serve..." according to the first book of directives issued by the agency in 1905 (The Use Book). Two years later, a provision in the Agricultural Appropriations Act of 1907 made it a law that "hereafter officials of the Forest Service shall, in all ways that are practicable, aid in the enforcement of the laws of the States or Territories with regard to...the protection of fish and game." The agency helped pioneer the field of wildlife management and stimulated many of the States to begin or improve their own programs. Hunters and anglers were the largest group of recreationists visiting the national forests, so it was natural for the Forest Service to focus its attention on fish and game animals. Federal game refuges created on national forests to conserve wildlife were helpful in increasing populations of game animals, and these animals could then be hunted on adjacent lands. The growth of deer populations led to conflicts between hunters and ranchers. Recreational hunters wanted more game animals; ranchers, concerned with forage depletion, wanted fewer. In the 1920's, the Forest Service effort to reduce the overextended mule deer populations on the Grand Canyon Federal Game Preserve (Kaibab National Forest) went to the Supreme Court. The agency won a limited victory in 1924 when the Court found that Forest Service employees could hunt excess game to "prevent property damage," that is, to protect the forage resource from overgrazing by deer. It was there, in the Southwest, that Aldo Leopold, a Forest Service employee from 1909 to 1928, developed his concept of wildlife management that led to the first textbook, Game Management (1933). Leopold favored the eradication of predators as a step in bringing back big game populations. However, after killing a wolf he realized that predators were important to the natural balance of deer populations. In 1929, the Forest Service hired its first wildlife biologist, Barry Locke, who was stationed in the Intermountain Region. He left 2 years later to serve as Director of the Izaak Walton League. At first, the economic depression of the 1930's halted wildlife programs for lack of budgets. The public works programs later developed to provide employment in areas such as natural resources conservation, including wildlife habitat improvement. Much of this work was done by the millions who served in the Civilian Conservation Corps. By 1936, the year Dr. Homer Shantz became first director of wildlife management, 61 people were assigned to wildlife work in the Forest Service. The national forests in the Southeast grew rapidly in number during the Depression through Federal purchase of severely cutover and eroded private lands. The management challenge for these lands was to make the recovering forests suitable places for wildlife. From this goal came the slogan, "Good timber management is good wildlife management." In the Pacific Northwest, the Forest Service found the public concern over elk protection superseded demand for timber production. It involved a lengthy battle with the Park Service over the management of Mt. Olympus National Monument, which was established in 1909 to protect the Roosevelt elk (named after Teddy Roosevelt). Forest Service officials argued that the best use of the monument, then managed by the Forest Service, and surrounding national forest land was to open the area to forest (timber) management, which would provide employment and recreation for the local population. The controversy came to a boil during the mid-1930's when the elk population in the monument was reduced by shooting to prevent overgrazing, disease, and starvation. Citizens were outraged, especially the editor of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, whose wife was the daughter of President Franklin Roosevelt. When Roosevelt visited the area in 1937, he had already decided to include the monument and adjacent national forest system lands in a new Olympic National Park (established by Congress in 1939). In the late 1940's, agency involvement in wildlife was reduced following the improvement of State fish and game programs and the rise of timber harvesting on national forests. Program areas surfaced as squirrel hunters in the Southern Region, upset over losses of oak trees exclaimed in 1956: "You kill the hardwoods, we'll kill the pine." In the 1960's, turkey hunters on the Monogahela National Forest complained of clearcuts in their favorite hunting areas. The result was a lawsuit, congressional hearings, and passage of the National Forest Management Act of 1976. This law required the Forest Service to conduct its planning to ensure a diversity of plant and animal species and, therefore, is responsible for the rapid increase in wildlife personnel in the late 1970's. The Forest Service was not created to protect wildlife, but its rangers realized that if they did not manage these animals' habitats, nobody else would. Thus, the agency became an early leader in the field of game management. Passage of the Endangered Species Act of 1973 gave additional authority to land managers to protect individual species and habitats for threatened and endangered wildlife, fish, and plant species. The Forest Service caught up with this new reality with publication of Wildlife Habitats in Managed Forests—The Blue Mountains of Oregon and Washington (1979), edited by future Chief Jack Ward Thomas. It was the first agency book to provide "concrete direction for the management of game and nongame species alike." |

|

| Hell Roaring Fire in Yellowstone National Park, 1988 USDA Forest Service |

Yellowstone Fire in 1988

As a result of the terrible fires that spread through Yellowstone National Park and adjacent national forest lands in the summer of 1988, the Forest Service and the National Park Service received considerable public pressure to change their policy of letting some fires burn naturally (the so-called "let-burn" policy). After much public and scientific debate about fire's proper role in the environment, and after viewing the subsequent "rebirth" of the park and adjacent national forests, the agencies have modified their policies to put out fires more quickly but still to allow some natural fires to burn under strictly controlled conditions.

|

| Pisgah National Forest Scenic Byway (North Carolina) USDA Forest Service |

Development of Partnerships

A series of new programs were developed at the Forest Service's national level in the late 1980's and early 1990's. The Challenge Cost-Share Program, established by Congress in 1986, has provided the means for the Forest Service and the private sector to share management and financial costs for projects on the national forests.

Currently several thousand cooperative wildlife habitat enhancement projects on the national forests are carried out by the Forest Service, other Federal and State agencies, and nonprofit organizations—like Ducks Unlimited, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, and many others. The habitat enhancement program grew from $2.5 million in fish and wildlife habitat improvements in 1986 to more than $17 million in Federal funds that were matched by $23 million from partners in 1996 to accomplish 2,135 projects.

The Presidential initiative "America's Great Outdoors" was designed to encourage cooperation between the Forest Service and the private sector in developing and improving recreational facilities and opportunities for the public. Another popular program, in conjunction with other Federal agencies, is the "Scenic Byways" program, which has designated about 7,700 miles of national forest roads and highways for recreational pleasure—often scenic roads that have ample opportunities for scenic vistas, unusual geologic and forest features, bicycle and hiking trails, rest stops, picnic areas, campgrounds, boating, fishing, and wildlife viewing. In Alaska, the Alaska Marine Highway (the Alaska Ferry System) has also been designated a Scenic Byway.

|

| Joe Meade and Guide Dog "Missy," Deschutes National Forest (Oregon), 1977 USDA Forest Service |

International Forestry

Several other initiatives have been developed to encourage recreational pursuits on the national forests, as well as to improve the natural resources. One of these has been the successful "Rise to the Future" program, which was designed to enhance fish production and encourage fishing on the forest lakes and rivers. Others include "Taking Wing," a waterfowl and wetland program to enhance habitat on national forests and support the North American waterfowl plan; "Animal Inn," a program to communicate the importance of managing dead standing timber and fallen trees for wildlife habitat; and "Join Us," a program to strengthen public-private partnership in fisheries and wildlife management.

|

| Institute of Tropical Forestry, Puerto Rico USDA Forest Service |

International Forestry

In 1990, Congress directed the Forest Service to assume a greater role in international environmental affairs. International Forestry a new "leg" of the Forest Service (along with the National Forest System, Research, and S&PF), was established in 1991 to coordinate and cooperate with other countries on matters dealing with forestry and the environment. Although previous programs had worked closely with other countries to provide expertise and experience in these matters, the International Forestry program area has given higher priority to engaging in dialogue and cooperation with other countries to solve global resource problems. The 1992 signing of the Forest Principles and Agenda 21 at the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED)—the "Earth Summit"—was coordinated by this new branch of the agency. Due to reorganization of the Forest Service and funding cuts, the International Forestry program was reduced from a Deputy Area to a Staff that reports directly to the Chief in 1997 and renamed the Office of International Programs. The program continues to work with countries on natural resource management internationally. It focuses current programs on Indonesia, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, the newly independent states since the breakup of the former Soviet Union, and Russia.

International Programs is also the home of the Disaster Assistance Support Program (DASP), which assists with support personnel and humanitarian relief on international disasters, both natural and human-caused.

|

Adapted from Terry West's 1991 Paper: It may be said that Forest Service's involvement with foreign forestry began after the Spanish-American War of 1898. U.S. Army Captain George P. Ahern organized the Philippine Bureau of Forestry in 1900 and invited USDA Bureau of Forestry director Gifford Pinchot to visit and offer advice in 1902. Creation of Luquillo (now Caribbean National Forest) forest reserve in Puerto Rico in 1903 further involved the Forest Service in tropical forestry. The Forest Products Laboratory (Madison, WI) began a program of tropical wood research shortly after being founded in 1910, with employed Eloise Gerry writing the first of a series of research reports on South American forests and woods of commerce in 1918. In 1928, the McSweeney-McNary Forest Research Act authorized the establishment of a forest experiment station in the "tropical possessions of the United States in the West Indies." That act and wording led to the establishment of the Tropical Forest Experiment Station in Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico, in 1939. Today, the expanded International Institute of Tropical Forestry (IITF) has responsibility for programs in international forestry, State and private forestry, and research and development. It was the onset of World War II that set the basis for increased U.S. involvement in international forestry. During the war, U.S. Government defense needs led the United States to foster studies of forest conditions in selected Latin American countries. Teams of foresters were dispatched to South America in search of sources of cinchona bark to meet wartime quinine needs to treat malaria. After World War II, foreign aid projects became the concern of international forestry in the Forest Service. During that period, two organizations involved U.S. foresters in forestry projects: The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). FAO was born in 1943 when President Franklin D. Roosevelt convened a conference to consider ways to organize international cooperation on agriculture. FAO's agenda excluded forestry until a group led by the Forest Service managed to get it added during FAO's first conference in 1945. For years, foresters struggled to persuade developmental agencies that forestry was a critical element in land use planning. The basic problem was that most of these agencies were concerned primarily with agricultural production to feed the world's growing population. It was left to the Forest Service to promote forestry wherever its staff could find a forum. There were other forestry opportunities with the International Cooperation Administration (ICA), a semi-autonomous agency with the U.S. Department of State. Early ICA forestry work was small-scale—one person assigned to a country. For example, in the early 1950's Forest Service employee Eugene Reichard served as forester for Columbia and Bolivia. Nonetheless, this agency was a primary conduit for Forest Service participation in international forestry. In 1950, President Truman announced bilateral technical assistance to newly independent countries and to other developing nations. The Forest Service was called upon to provide two kinds of help: 1) Recruiting foresters and technical leaders for assignment overseas, and 2) receiving foreign nationals for academic studies or on-the-job training in forestry and related areas. Over the next two decades (1950 to 1970) the Forest Service furnished over 150 professionals for long-term assignments or short-term details to technical assistant programs overseas; in the same period over 2,500 foreign national went through Forest Service training programs. In 1958, the unit became known as the Foreign Forestry Service in the Office of the Deputy for Research, with A.C. Cline designated as its director in 1959. Two new sections were added in 1961: 1) Technical support of foreign programs, and 2) training of foreign nationals. In 1987, the program filled over 800 requests for technical consultation from 50 countries. The same year, 35 Forest Service employees served on 1-year assignments in 20 foreign nations, with 8 others on short-term projects rendering technical assistance in such areas as recreational planning, range management, land use planning, forest industries, and nursery development. Following publicity over the environmental impact of tropical deforestation, the 1980's saw an increased public interest in international forestry. Chief R. Max Peterson in 1980 wrote of "our increasing need for involvement in forestry problems beyond our own domestic programs." The movement accelerated with a flurry of publications. USAID acted early with its Forest Resources Management Project in 1980 that led to the Forestry Support Program (FSP) in the Forest Service and a joint USAID/Peace Corps Initiative. A decade later, the 101st Congress passed legislation—the Global Climate Change Prevention Act and the International Forestry Cooperation Act—that greatly expanded the role of the Forest Service in international resource management. The Global Climate Change Prevention Act directed the Secretary of Agriculture to establish a Office of International Forestry under a new and separate Deputy Chief in the Forest Service. Jeff Sirmon was selected as the first Deputy Chief. Since 1985, International Programs have included the Disaster Assistance Support Program (DASP) and Disaster Assistance Response Teams (DART). DASP assists with support personnel and humanitarian relief on international disasters—both natural and human-caused—including fires, floods, famine, earthquakes, and civil strife. DART are deployed by the U.S. Agency for International Development's Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA) to assist OFDA in providing disaster prevention, preparedness, and emergency response to developing nations in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Caribbean, and the Pacific regions. The objectives of the DART response teams, which are comprised of volunteers, are consistent with the Strategic Plan for International Forestry Cooperation signed by the Forest Service in 1995, the International Forestry Cooperation Act of 1990, and the Global Climate Change Act of 1990. Over the last 15 years, many relief teams have been sent to African countries, including Angola, Namibia, Somalia, Rwanda, Sudan, and South Africa, as well as to assist with disasters occurring in Peru, Yugoslavia, and many other nations throughout the world. In 1997, the position of Deputy Chief for International Forestry was eliminated and International Forestry became the Office of International Programs, reporting directly to the Chief. The program continues to work with countries on natural resource management issues internationally and to support DASP and DART. It focuses current programs on Indonesia, Brazil, Canada, Mexico, the newly independent states in the former Soviet Union, and Russia. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec8.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008