|

THE USDA FOREST SERVICE— The First Century |

|

ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT AND THE FUTURE ERA, 1993-PRESENT

The foundation for ecosystem management, based on the ecology of the land, air, water, plants, animals, and people, was introduced by Chief Dale Robertson in 1992. It was a logical conclusion to the earlier management ideas called "new forestry" and "new perspectives." Although the ideas had been talked about for decades, this was the first effort to apply the principles to the 191 million acres of the National Forest System.

In early April 1993, President Clinton and Vice President Gore, along with five cabinet members, met representatives of the public in Portland, Oregon, to discuss the spotted owl and timber harvest situation in the Pacific Northwest and northern California. Never in the history of the agency had the administration put such emphasis on resolving problems in the national forests and adjacent BLM districts. The result of the Forest Conference was the calling of the top forest researchers to develop in 60 days a credible scientific solution to managing the Federal forests under a comprehensive ecosystem management plan for the Pacific Northwest.

The Federal scientists and managers, also known as the Forest Ecosystem Management Assessment Team (FEMAT), produced a comprehensive ecosystem management assessment (FEMAT report) and management plan (Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement) for the Pacific Northwest. Similar analyses are being worked on for forest areas in other Forest Service regions. The Interagency Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project (ICBEMP) in 1997 included an assessment and plan for managing the Federal forest and grazing lands of a huge area covering much of central and eastern Washington and Oregon, northern Idaho, and western Montana. Other large-scale assessments have been produced, including the Sierra Nevada Ecosystem Project (SNEP) in the Pacific Southwest Region (1996) and the Southern Appalachian Assessment (1996). Other long-term assessments, like the Greater Yellowstone, are in the process of study.

The Forest Service, under the leadership of wildlife researcher Chief Jack Ward Thomas, quickly adopted ecosystem management—where the long-term sustainability of ecosystems was the management goal for the National Forest System rather than board feet of timber, dollars in the Treasury or counties, and jobs in the communities.

Chief Mike Dombeck, after his appointment as Chief in 1997, changed the emphasis of ecosystem management through the "Natural Resource Agenda." Basically the agenda emphasized four areas of management: 1) watershed health and restoration, 2) sustainable forest management, 3) national forest roads, and 4) recreation. In keeping with the intent of the Organic Act of 1897, this new agenda put protecting the national forests as the primary goal of management, followed by providing abundant, clean water, and finally allowing multiple-resource management on the areas that can sustain intensive activities. On October 13, 1999, President Clinton announced that the Forest Service would study the road/roadless area issue again and provide a solution for public review.

|

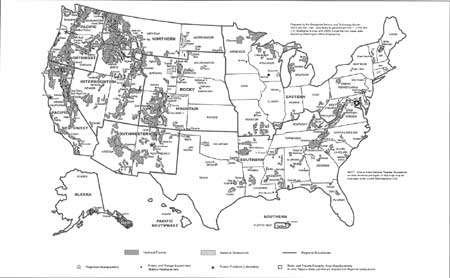

| (click on map for a PDF version) |

|

Ecosystem management, the driving force behind current policy of the Forest Service, USDI Bureau of Land Management, and other Interior agencies, combines philosophy, conservation, ecology, environmentalism, and politics. Although the term "ecology" has been around since the 1800's, management using an ecological framework is relatively recent. Aldo Leopold's book A Sand County Almanac (1949) and Rachel Carson's book Silent Spring (1962) influenced many people to look at the broader picture of the interaction between people and the environment. In 1970, Lynton Caldwell published an article that perhaps for the first time advocated using an ecosystem approach to public land management and policy. Then in the late 1970s, Frank and John Craighead pioneered efforts to use broad ecosystems in the management of grizzly bears in the Yellowstone National Park and surrounding national forests. By the late 1980's, many researchers and public land managers were convinced that an ecosystem approach to manage public lands was the only logical way to proceed in the future. The following 10 elements contain what ecosystem management means for public and private land management (thanks to the work of Edward Grumbine): 1. Multiple Analysis Levels—Use different levels of analysis, from the site-specific location to the broad watershed perspectives or even larger. 2. Ecological Boundaries—Define ecosystems by analyzing and managing them across political and administrative boundaries. 3. Ecological Integrity—Protect the total natural diversity, ecological patterns, and processes. Keep all the pieces. 4. Data Collection and Data Management—Require more research, better data collection methods, and up-to-date information. 5. Monitoring—Track results of management actions. Learn from mistakes. Take pride in successes. 6. Adaptive Management—Use adaptive management, a process of taking risks, trying new methods and processes, experimentation, and most of all remaining flexible to changing conditions or results. Encourage better public participation and involvement in planning. 7. Interagency Cooperation—Work with agencies at the Federal, State, and local levels, as well as the private sector, to integrate and cooperate over large land areas to benefit the ecosystems. 8. Organizational Change—Change how the various agencies work internally and with partners to encourage cooperation and understanding, as well as advance training for on-the-ground employees. Expand partnerships and cooperation with other agencies and the public. 9. Humans Are Part of Ecosystems—People are a fundamental part of ecosystems, both affecting them and affected by them. Involve people at all stages in the analysis and decisionmaking phases. 10. Human Values—The human attitudes, beliefs, and values that people hold are significant in determining the future of ecosystems as well as the global environment. Seek balance and harmony between people and the land with equity across regions and through generations by maintaining options for the future. |

|

Jack Ward Thomas was born in Fort Worth, Texas, on September 7, 1934. Amid controversy about how new Chiefs would be appointed, Thomas was given the job on October 1993 as a political appointee with the assurance that he would be converted to a career appointment through the Senior Executive Service (through which Chiefs Peterson and Robertson were appointed). Soon after his becoming Chief, Thomas had to address a demoralized agency, with the public in opposition to practically anything that the Forest Service proposed to do. The controversy about the Northwest Forest Plan for the spotted owl region (western Washington, western Oregon, and northern California) was especially troubling. Yet Thomas, a Forest Service wildlife researcher his entire career, led several efforts to resolve conflicts over management under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, especially relating to spotted owls. Chief Thomas was greeted with suspicion by some, but was hailed by others. During his relatively short tenure as Chief, he moved quickly into implementation of ecosystem management for all the National Forest System lands. Jack Ward Thomas wrote:

|

|

Michael P. Dombeck was born on September 21, 1948, in Stevens Point, Wisconsin. He spent 12 years with the Forest Service primarily in the Midwest and West. In his last Forest Service post before he became Chief—National Fisheries Program Manager in the Washington Office—he was recognized for outstanding leadership in developing and implementing the fisheries programs and forging partnerships. He then spent a year as a Legislative Fellow working in the U.S. Senate with responsibility for natural resource and Interior appropriations issues. Dr. Dombeck was named Acting Director of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in February 1994. After less than 3 years as Acting Director, he was selected as the new Chief of the Forest Service in January 1997. During his tenure, he focused on two major objectives: Creating a long-term vision to improve the health of the land through the "natural resource agenda" and improving customer service through a program entitled "collaborative stewardship." Mike Dombeck wrote:

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

FS-650/sec9.htm

Last Updated: 09-Jun-2008