|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 2 |

|

October 1955

MEMORIES

By Theodore Shoemaker

(Retired 1938)

Beaver Ridge Fire — Lolo National Forest, Idaho, August 1931. I took 100 men as reinforcements, carrying tools, by trail, 11 miles and a 3,000-foot climb; then down through the burn to bottom of fire on steep mountain side; "cooled" our way to the outside of burn; built a mile of line; went back inside the burn to an alder swamp that men had cleared ready to set up kitchen when the pack strings arrived (only possible campsite). No food, no beds; instead, a note from the ranger: "Both strings rolled, scattering cargos all down the mountainside. Some horses killed or maimed and one packer injured. No relief till 2:00 tomorrow. Carry on till then."

Questions: How did those tired, hungry and begrimed men react to this situation? Should the man who had gotten them into it be allowed to go on living? Answer: The fire was controlled next day before the food arrived, and the man who might have been made to face a firing squad is writing this "short-short" 23 years later.

Sheep Mountain Fire — Clearwater National Forest, Idaho, July 1925. I took 30 men with a pack string carrying beds only and hiked 60 miles in 3 days, over trails that were hot and dusty much of the way and rocky and steep the rest. Men had been hastily picked up from the streets and pool halls in Missoula, Montana. I met them at the N P. Depot about 3:00 p.m., and took them by train and trucks to the end of the road up Cedar Creek. Here arrangements had been made to feed the men supper and breakfast and provide each with a "sacked lunch" to eat on the trail to Chamberlain Meadows where they would be given the same treatment the second night. The third night we were to reach a fire on the North Fork of the Clearwater River, but didn't due to change of orders sent to us from Wallow Mountain Lookout late in the afternoon.

Men were, with few exceptions, soft; some poorly shod, having been furnished new shoes to break in that had not been well fitted in the rush to get the men to the train in time. They began to have blisters soon after we started the first day, and in spite of all the bandages, tape and chiropody we could bring to their aid at Chamberlain that night, it is true to say that several men virtually limped their way to the fire.

Change of plans took us to a packer's camp and corral on the river where food and mess equipment were to have been delivered, but were not, so we went supperless to bed and hit the trail at day break for a 7 mile hike to the Canyon Ranger Station for breakfast. Two of the men who made that last stretch barefoot had to be left there, while the others hiked on dowmriver, crossed on a flimsy raft and climbed up 2,000 feet in about 4 miles of trail, finally to reach the fire.

It was then late afternoon and the men were fed and directed to find places to bed down. A camp had been established near the trail by a small crew already on this fire, and our pack string with beds had arrived ahead of us.

I met Renshaw, who was in charge, and went around the fire to plan the action. With 10 men to work through the night, and the rest with Renshaw's crew to come on at daylight, it looked as though we could put that fire under control and be ready to move on to the really bad fire a few miles further around the mountain. This we did, cutting trail to the big fire, where we took over a dangerous sector above the fire, cleared and fire proofed camp and controlled the fire in two days. We then hiked out over the top of Sheep Mountain down to and forded the river stripped naked and on to Bungalow Ranger Station at dark, had supper and on by trucks to Orofino.

This entire trip of 10 days replete with incidents depicting human behavior under trying circumstances; how men respond to leadership and sympathetic treatment, adjust themselves to each other's widely varying personalities, and develop a spirit of helpfulness and camaraderie that goes far toward restoring one's respect for that element of society we are in the habit of dubbing "down-and-outers." In this crew were two Negroes, old Sam Lundy, a Spanish War veteran, and his stalwart son, Bud. Not once did I detect any sign of race prejudice, whereas on different occasions I noticed marks of special respect for Old Sam shown by younger whites when he became noticeably weary or seemed a bit slow in the kitchen, to which I assigned him, partly because of his years and partly because of his having been an army cook.

On the long pull up out of Cedar Creek the first morning, I taught the men how to regulate their breathing to keep from becoming winded, and how to smoke safely only when seated with their feet in the dust of the trail where they would drop their matches and butts and grind them into the dirt with their heels. They took to these examples of my interest in their comfort very well, and it furnished them a sound basis for "sizing up" the boss on what I am sure, for most of them, was to be the great adventure of their lives.

This was probably the longest trek fire fighters were ever asked to make to get to the job. Such a venture will likely never be repeated. Few of these lightning-caused fires will reach crew-size because, within am hour or two, men will be on them by truck from one of the networks of roads built since them, or smokejumpers will come winging and swinging their way down from above to land nearby, and these men will apply a degree of expertness in stopping the spread of fires that was not known 30 years ago. Progress in all angles of fire control have truly been outstanding, but that is too broad a topic to be more than hinted at here for purposes of comparison of then and now.

|

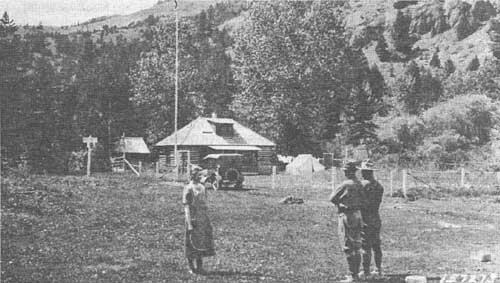

| Fish Creek Ranger Station, Nezperce National Forest. 1925. |

|

| Big Creek Ranger Station, Gallatin National Forest. 1925. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/2/sec13.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |