|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 2 |

|

October 1955

MUSSELSHELL REMINISCENCES

By K. D. Swan

(Retired 1941)

The year was 1913. District One of the Forest Service had tightened its belt and gone to work with renewed vigor after the great fires of 1910 which took such a heavy toll of human lives and timber in the Northwest. Fire killed trees were being salvaged. Foresters were busy with planting projects which would help reforest the burns. New ideas in forest fire control were being worked out. We were just beginning to hear of the Pulaski, the Koch tool, the Jack Clack pack frame — gadgets which were to become standard equipment in the district.

And with all this activity came a growing awareness of the timber resources of the forests, and a realization that as more accessible stands were depleted in providing for the expanding economy of the Northwest, reservoirs of potential lumber farther back in the hills would be drawn on.

Just where were these stands, and how much timber did they contain that could be made accessible to the logger? Silcox, Stuart, Mason and others were seeking data to answer these questions. And so were launched a series of timber reconnaissance projects which, in the passing years, have become almost fabulous in the annals of the region. One tries to imagine how much material connected with these jobs has gone into the files of the regional office — material gathered with blood and sweat (a timber cruiser had to be too tough for tears), but imagination fails. Though the notes and maps have passed into oblivion via the closed files, it is safe to say that the homely details of those jobs still live in the memories of the men who took part in them. I was one of those men.

One of the important jobs planned at that time was a reconnaissance of the Musselshell watershed of the Clearwater Forest in Idaho. Here was one of the finest mature stands of virgin white pine on national forest.

Intermixed was much western red cedar, Douglas fir, grand fir and western larch. It was a stand ripe for cutting — a stand which would prove very saleable in the opinion of those who were acquainted with it.

I remember well my first impressions of this magnificent forest as I first saw it after sundown in early March: the tall, straight pines reaching toward the sky, still flushed with sunset colors, the cedar trunks massive in the gathering darkness. It was with a feeling of awe, mixed with a pleasant expectancy, that I realized I was to live in this forest environment for the next several months.

Men assigned to the job were told to report in Orofino, the forest headquarters. It was on the board sidewalk that fringed the muddy main street that I first met a member of the Musselshell crew. He was Eldon Myrick, fresh from the forestry school at Moscow. We had a brief talk concerning what might lie ahead in the months to come, and them went over to the supervisor's office where we had more talk with Charlie Fisher, the supervisor. Through the years Eldon Myrick has retained that cordiality which I so well remember from the day of our first encounter.

Transportation, especially in winter, from Orofino to the Musselshell Ranger Station, was in those days tedious to say the least. One took the afternoon train to Greer, where lodging was had in the hotel, a venerable structure even in those days. Next morning began the long ascent up the Greer grade in a horse-drawn vehicle known as the "stage," but better described as a cross between a surrey and a mountain wagon. From the comparatively low elevation at the river where snow seldom came, the climb was made to the more wintery climate of the Weippe Prairie. At Fraser, reached about dinner time, passengers were transferred to a sled. Over the prairie, through the little hamlet of Weippe, and so into the long aisles of snow-filled woods beyond. Brown's Creek the way led, until about an hour after sundown the lights of the Musselshell Ranger Station twinkled from the meadow. Today one makes the trip from Orofino by car in not much over an hour!

It was in the big room on the second floor of the Musselshell Station amid a reek of Bull Durham and drying clothes that I first met chief of party Fred Mason and was introduced to other members of the crew — Shaw, Miller, Richardson, Parker. Myrick was also there.

Fred Mason, stocky, taciturn, but friendly, was brother to Dave Mason of the district office. Not given to frivolity or boisterous talk, he kept his mind strictly on the work in hand winning the respect and confidence of his men because of fair dealing and avoidance of playing favorites. His was a tough job and he did it well.

In a few days Lloyd Fenn and Alfred Hastings came in from the field. Fenn left for other work after a brief period, but Hastings stayed with the crew as assistant to Mason. Later a boy named Miles joined us - Clark Miles, who later worked for many years in Region Four. In about a month Jim Yule was assigned to our project as camp draftsman. This, I believe, accounts for all members of the Musselshell crew.

An engineer named Buckner, assisted by Fenn and Hastings, had run a traverse around the exterior boundaries of the area to be cruised. This control line was marked by blazes on the trees. Inasmuch as the traverse was run when the snow was deep, these blazes were left far above the ground when the snow melted and were sometimes hard to find. A liberal outpouring of uncomplimentary remarks directed at the control crew resulted when a cruising party overlooked the blazed line and found itself far out of bounds in the adjoining watershed.

The country close to the ranger station was used as a training ground for the crew - very few of the men had had any previous experience in this sort of work. Until the first part of May, snowshoes or "webs", were a must for getting around, and learning to manage this footgear was am important item in the training of some of the men who were not used to winter travel in the woods. This presented no problem at all to me as I had been on many snowshoeing trips to the woods of northern New England in my school years.

The tailless "bearpaw" shoe was the favorite type, although a few including myself, preferred the conventional Canadian shoe. Some made their own webs, using pliable cedar limbs for the frames and rawhide "filling" for the mesh. As spring advanced bringing warmer weather, the snow became soft and mushy before noon making snowshoe travel arduous and at times just about impossible later in the day. We went to work at daylight so as to "catch the crust" which had formed during the might.

The method used in cruising was simple enough, but much practice was required to gain a reasonable amount of accuracy in results. Mapping was done with a small Forest Service box compass, an aneroid barometer, and a pair of legs trained in the art of "pacing" for distance. Biltmore sticks were used by the timber estimators. Trees within a distance of one-half chain of the line were tallied. There is considerable variation in barometric pressure throughout the day, and readings from an aneroid barometer to determine elevations are useless unless allowance is made for this variation. Therefore, a barometer was kept in camp and readings taken at stated intervals throughout the day. This data was used by the mappers to correct readings taken along their lines during the day.

In about two weeks the crew had worked the country which could be reached easily from the ranger station and all hands moved to some old cabins belonging to the Musselshell Mining Company on Gold Creek. On the move each man carried his own bedroll in which were wrapped such belongings and extra clothes as he felt he would need. Grub was supplied to this camp, and several subsequent ones by packers who used packboards and toboggans. Our diet was mostly ham, bacon, dried beans, evaporated potatoes, prunes, cheese, baking powder bread, coffee with evaporated apples and cranberries and a cheap grade of chocolate for luxuries.

Conversation of an evening would invariably drift into a discussion of grub and the prospects of getting more palatable meals when packhorses could be used to supply the camps. We later found to our disgust that with the exception of fresh potatoes and a meager supply of canned tomatoes and corn there was little improvement in food when the trails were open. I doubt if a crew would stay on the job today with a cookhouse as poorly supplied as was ours at that time.

This paucity of cuisine led to some queer situations. One morning the cook reported that there had been a raid on the chocolate which was stored in the cabin loft. Before going to work chief of party Mason called the crew together into solemn conclave and announced that there would be no more chocolate for lunches for a week, and there wasn't!

This, of course, brought down the ire of the crew on the cook, a rather naive individual who was out of his element among such a bunch of ruffians as we believed ourselves to be. Two of the men spent one evening whetting an enormous butcher knife which they found in an old meat house at the camp, meanwhile making remarks in a low tone of voice as to what was going to happen to a certain cook. The cook quit as soon as another man could be found to take his place. The new man's name was Wilson - he stayed with us until the end of the job.

Spring brought a few warm, sunny days, but also long periods of cloudy weather with much rain and snow. Easter Sunday found us camped at a cabin on Eldorado Creek, and a more dismal place would be hard to imagine. The cabin itself was still buried in smowdrifts. It was too small to be used for anything but a cookhouse. Sleeping tents for the crew were set up nearby, and a huge fire kept burning constantly for warmth and drying out clothes. This fire eventually melted through five feet of snow until it at last rested on the ground. Then a base of green logs was built so as to bring it up to the level of the hard packed snow around the tents.

But at last came longer periods of sunny weather and the snow rapidly disappeared from the steaming woods. By mid-May much of the work could be dome without snowshoes. Our first comfortable camp was at the Day Cabin.

This structure, built by a miming concern, was nicely located in a dry, sunny situation, and was far more spacious than the hovel on Eldorado Creek which we had just left. Several of the men slept in the loft inside, several others including myself, jungled out in small tents, improvised from tarpaulins. A tent in front of the cabin provided dining quarters and extra room for storing supplies. A galvanized washtub filled with water heated over an open fire gave us a chance to bathe, as well as to wash our clothes. It was here that Charlie Farmer appeared on the scene. Charlie was assistant to the Chief of Engineering in the district office, and was in charge of the preparation of maps. Genial and friendly, a ready talker with a fund of stories, a prankster par excellence, inventive, a man with real ability who took unusual problems as a challenge - Charlie was one of the most talented and likeable men with whom I made friends in my early days with the Service. Charlie's appearance in camp was always the signal for an open season of practical jokes. This visit was no exception.

Jim Yule was well established in the routine of camp draftsman and Charlie spent some time in checking methods of correlating topographic sketches turned in by the mappers, and placing such data on the base map. Finding things in satisfactory shape, Charlie was left more or less free to play a few practical jokes of a minor nature - just what they were I do not remember, but at any rate they were such as to call for retaliation, and they touched off one of the most amusing episodes of the entire job.

It was a balmy spring evening with the moon near full. We had spent an hour or so swapping yarns around the sheet iron stove in the cabin before turning in. Charlie was to sleep in one of the cabin bunks reserved for visiting guests. The cook made some preparations for breakfast and then left the cabin to go to his sleeping quarters.

When it was certain that all inside the cabin were sound asleep, which must have been a half hour or so later, two figures emerged from the shadows into the moonlight. One carried a flat rock, the other some fir boughs. The latter went inside the cabin and stuffed the boughs in the stove. When it was certain a good rousing fire was kindled the other man climbed on the cabin roof and put the rock over the stove pipe. Then the cabin door was wired shut from the outside.

It was only a matter of minutes before there were signs of life inside the cabin. Smoke was pouring out from beneath each shake, which made a weird sight in the moonlight. Coughing and sputtering mixed with intemperate language and pounding on the closed door created pandemonium. The tumult attracted all who were sleeping outside the cabin. The climax occurred when someone inside had the presence of mind to take out one of the small windows through which the men made their escape one by one.

While camped at the Day Cabin two of the men - I think they were Shaw and Miller - killed a bear, which provided fresh meat to vary the ham-bacon diet. We had it fried, boiled, in stew, and ground to hamburger. We had it for breakfast, lunch and dinner. Never did any of us care if we ever ate bear meat again.

Those who know of the strong resemblance between the bones of the front leg and paw of the bear and the skeleton of the human arm and hand will appreciate the effect that was achieved by nailing this skeletal appendage of bruin over the cabin door as a hint of what would occur to a certain ranger should he appear in camp! This ranger was supposed to be the man responsible for the quality of the grub furnished us. We later learned the supervisor's office and not the ranger was to blame. But anyway, word of our doings reached the ranger via the grapevine and when he was forced to visit camp he brought the supervisor as bodyguard. Over the same grapevine came the report of his remarks on getting safely back to the ranger station:

"They're a tough lot those boys, a bunch of young cutthroats. They say they'd kill a man if they caught him alone, and by Gawd I think they would!" Poor old Bob Snyder, kindly and loveable, a man who tried to do his job as he saw it. May we be forgiven for the rough time we gave him in those far-off years!

There is much more of an amusing nature that could be told, incidents that will come to mind as one reads this brief narrative - the evening song fests, the terrifying groans of the boss as he struggled with a nightmare, the no-see-ums and the mosquitoes that came in due season, the evening expeditions after venison, the side camp excursions to remote areas, walking the footlogs over swift water, and bucking the wet brush after a rain. There were few, if any dull moments that I can recall!

Early summer found us working in the Mud Creek drainage, the most southerly part of the Musselshell area. Here the topography was not as diversified as farther north; there was much comparatively level country and few land marks. Mapping became more of a problem due to the inefficiency of aneroid barometers in measuring slight changes of elevation. Then, too, the fluctuations of pressure because of thunderstorms every afternoon made it still more difficult to determine elevation with even a fair degree of accuracy.

To correct a series of readings taken in the field by a check on the curve made from the camp barometer was a tedious job. We often talked among ourselves of better methods of mapping, and sure enough a better method was being devised, although we did not know about it at the time. The very next year the steel tape and Abney level were tried out and found to be practical and to give far better results than were obtained under the old system.

Probably no man on the job played a more important part than Jim Yule in his role of camp draftsman. His was the job of taking the sketches turned in daily by the mappers and fitting them together to form a topographic map with contours -- streams and ridges in proper position. A man of infinite patience and great resourcefulness to whom regular hours of work meant nothing, Jim made a notable contribution to the success of the Musselshell job. It is pleasant to think that those days when he burned the midnight candles over some mappers' notes, in an effort to make contours jibe, marked the beginning of a career which has been of inestimable value to the Forest Service in its program of formulating better methods of mapping the national forests.

The job came to an end the last of September. Before the windup, I had been assigned to a reconnaissance crew on Cedar and Cougar Creeks of the Coeur d'Alene Forest as camp draftsman. With the completion of this project late in the fall my timber cruising experience ended and I began a seven - year period in the Missoula office of Engineering as a topographic draftsman, an assignment which brought me great satisfaction.

Over forty years have passed since we cruised the Musselshell. With the lapse of time memories of the hardships of that pioneering job have lost their sharp edge. We remember instead those things which made living in the Idaho woods a priceless experience to all of us - things we shall never forget; the murmur of the wind in the treetops breaking the stillness of the forest, sunlight filtering into the dim aisles among the trees, the full moon casting patterns on the winter whiteness about our camp, powdery snow cascading from some overloaded forest veteran, a water ouzel singing above the sound of rushing water, the pungent smell of ceanothus on a warm hillside, lush fern gardens among giant cedars. Yes, these are things we would not forget - ever!

|

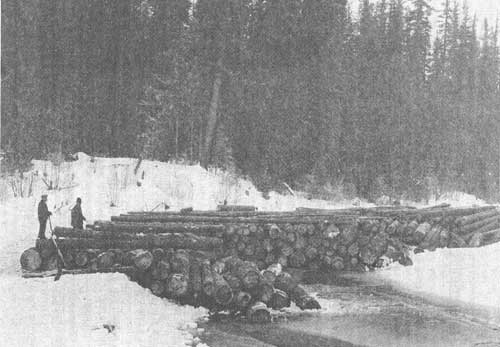

| Landing on Priest River, the end of the sleigh haul. Logs were driven in the spring to the mill. Kaniksu National Forest. 1923. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/2/sec14.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |