|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 2 |

|

October 1955

REMINISCENCES OF EARLY DAYS IN THE FOREST SERVICE

By Ryle Teed

(Retired)

I reported for duty in the Forest Service on July 1, 1911. This was at the Gleason Ranger Station on the Kaniksu National Forest in extreme northern Idaho. I came as a student assistant from the University of Idaho, being a charter enrollee of the School of Forestry organized in the fall of 1909.

Gleason Ranger Station, God knows why, was named for a filthy old hermit who was shacked up a couple or three miles away. The district ranger was Martin Murray, who had a jug cached in a hollow log not far from the station. Allie, his wife, was a strict one. If she'd known where the jug was, it would have been smashed right now. I was not reporting to Murray though, but to Forest Assistant Meyer H. Wolff who had a reconnaissance and stem analysis crew camped there. Wolff's assistant was Forest Assistant Arnold Benson. Dr. Charles H. Stattuck, head of the school at the University of Idaho was also there, temporarily and heading up the stem analysis job.

The stem analysis job went like this: We would find us a good western white pine (there were plenty within range of the station), fall it, swamp it, buck it up into 16-foot logs, horse the logs apart from each other and make a ring count with measurements. The mosquitoes were hell. The procedure was: Count ten rings, dot; count ten rings, dot. Actually, it was a tough guy who could count ten rings without stopping to bat at the mosquitoes, in spite of the fact that we covered up much of our exposed areas, like wrists with paper stuck on with balsam pitch.

The Gleason Station was in dense and utterly primitive forest. Allie Murray had a brother, Archie Newcomb, who, with his wife and two kids, lived within a mile of the station. We used to marvel at those kids. I'd say the boy was maybe seven and the girl five. They went anywhere and everywhere in that dense forest without fear, or even attention. They would show up out of the brush around the station from any direction, except by the road, and take off again the same way. When we were on stem analysis, maybe a mile or so away, we would hear their incessant chatter and here they would come, to hang around a bit before starting out again.

We wound up the season at the Pelke Ranger Station, an undeveloped station, named for Al Pelke, a real old time trapper who was then living at Coolin on Priest Lake. One of Al's tiny trapper cabins still stood and in front of it was a cedar with a big blaze on it. In the blaze was carved a cross. After Al's pardner was killed by Indians the Fathers told Al to carve the cross there and that the Indians would not bother him, and that is the way it worked out.

Now this brings us, with some more generalizations and introduction of a few more characters.

THE WRECK OF FIREFLY

In 1911 the headquarters of the Kaniksu Forest were in Newport, Washington, but in those days the essentials of a supervisor's office could be hauled in a lumber wagon, so that is just what was done each summer. The office was loaded up and hauled to Coolin, Idaho. Coolin was a city of maybe fifteen year-round residents, two summer hotels (one of logs), a tiny general store, but located at the foot of Priest Lake, a beautiful lake in beautiful and untouched mountains and forests. The lower lake was some eighteen miles of navigable water, then came the Thoroughfare, sometimes navigable, and then the upper lake, another four miles and extending nearly to the Canadian line. In all this extensive drainage there were at this time only two yearlong residents on the lake north of Coolin. These were the Sniders, about six miles up the west shore, and Sam Byers, the District Ranger at Byers Ranger Station on the Thoroughfare. There were no settlers anywhere on the east side. At that time there were no recent burns and no logging. There were a few, four or five only, summer residents, and occasional campers.

The forest office was a two-story, board-and-bat shack on the lake shore, with a dock and boathouse. The pride of the forest was the Firefly, a 2 foot launch which was good for about ten knots when running free. With the available waterway the trails naturally radiated from the lake. The pack train would come down to the shore, telephone the office, and the Firefly, with the barge lashed alongside, would go pick up the horses and either bring them to Coolin or move them to their next point of departure.

The prize seasonal job on the forest was that of "Commodore," the operator of the launch. This was, you might say, a job in name only, for the Supervisor, Willis N. Millar, practically always went along on trips, and when he was along he always handled the boat from the bow controls. There were also controls, including a steering wheel, alongside the engine.

Now it so happened that the day we of the reconnaissance crew reached Coolin to be disbanded for the season, Commodore Paul Clemmens, also from University of Idaho, quit. Mr. Millar asked me whether I would take the job. Now I was raised in the Snake River desert south of Boise and the Firefly was probably the first launch I had ever seem, but since the question of qualifications was not raised I jumped at the job. It was a wonderful job, although a busy one. We had no hours, often were out at 5 a.m., and might cast off again right after supper The pack train was going hither and yon, bringing in equipment for the season. Rangers were doing the same. We were running taxi service for a Mr. Lantham of the Department, who was doing soil survey work out from the lake on foot. Millar practically always came with me, regardless of the hour. And then it happened: It was getting pretty close to suppertime of a perfect fall day when Willis (Millar) came down to the launch. He said Clarence Swim (ranger from the Sullivan Lake District on the Washington side) had just pulled in at Sniders (about six miles up the lake), and that we would go up and get him. We were just lashing the barge alongside when someone called from the office that Lantham was ready to be picked up at the Outlet, which was a short run of less than a mile. So Willis said we would get him first and then go for Swim after supper, and we did.

It wasn't far from dark when we got to Snider's, where Swim and his five horses and their loads were hungrily awaiting us. We had a cistern pump on the foredeck of the barge. We tested this and there seemed to be no water in the barge, and we were in a hurry, so we got the horses on board and in the well deck which was down about to the waterline. The packs and saddles we piled on the bow and stern decks which were about a foot higher. I believe there were five horses, with three tied to the rail on the Firefly side, and two on the far side. We pushed off and started down the lake. There was still some light. Anyway, soon little plumes of fog began to rise from the lake the first ones a foot or three or four feet high. It was a queer and beautiful effect, but they were coming thicker and taller, until they had us fenced in and we couldn't tell where we were going. We had about five miles to go and, with the loaded barge, were making maybe two knots. There was an acetylene searchlight mounted on the canopy top, but it didn't help a bit. We left it lit but turned it backward out of the way. There was a marine box compass and we broke it out, but it turned out to have a floating dial, which was so confusing to us, all experienced compassmen, that we didn't fool with it.

The fog wasn't very deep and much of the time we could see straight up and hold some kind of a course by the stars. Millar was at the bow controls and I was at the engine controls near the stern. Whichever one could see at the moment would take over.

Now there were some light rushes in Priest Lake at a few points. One of the places was along a bad stretch of shore, precipitous and rocky, right across the lower end of the lake from Coolin, our destination. All of a sudden we were in rushes. It looked like we were going ashore right now. Willis, who had the wheel at the moment, threw the wheel hard over and we started a sharp but slow and cumbrous swing.

Just then Swim yelled, "The barge is sinking. The horses are climbing in the launch," and they sure enough were. Millar yelled, "Cut 'er adrift. Untie the horses."

Suiting action to the word, Millar jumped onto the sinking barge, then about up to the horses' bellies in water and started cutting then loose. Swim cut the bowline and I cut the stern line. We got Millar off the barge and it, the horses and the packs were lost in the fog. We couldn't pick it up with the searchlight, but knowing that we were close to shore, we left the light directed ahead.

We weren't left long to wonder whether the horses would succeed in getting ashore or would swim aimlessly in the fog and drown. Very quickly we heard the bell of the bell mare and knew she, at least, had made it. We eased the engine in gear and she stalled. The reason: We had a tent in the propeller. We worked it out of the prop and got it aboard — that much salvaged anyhow. And to Swim's lament that there went his new $30 saddle, we started the engine, began a slow swing which we hoped would head us toward Coolin, and swept our searchlight right across the open door of our own boathouse. "And so to bed," as Dr. Pepy says, but with a five o'clock date for the next morning to run down the barge, which was all wood and wouldn't stay sunk, once it had dumped its load.

The morning broke clear, but no barge anywhere in sight, so we manned the Firefly, Millar taking her out from his place in the bow. I was in my usual place alongside the engine, idly looking down through the the clear water. Suddenly I saw a pack saddle on the lake bottom. I yelled, and Millar said, "Mark something on the shore, and I will, too. And I did and he did, but that's all the good it did us for each of us had noted only one thing, instead of two, in line to give us an intersection. Well, we cruised around for a while, even ran out and in the boathouse, but no luck so we went to breakfast. After breakfast we rousted out all hands, including Miss Jackson, the summer stenographer, whom Meyer Wolff was ardently pursuing and eventually captured, and perhaps Earle Clapp, already a big shot in the Service, who was at the lake for quite a spell, and maybe Nelson A. Brown, the Deputy Supervisor, although I believe he had already gone to his teaching job in the East. With six or eight rowboats out we still weren't finding the spot and so decided to cross section that part of the lake with floats and go at it systematically.

Meyer Wolff was dumping Tyee Baking Powder at the corner of the office so we could use the cans for floats when Al Pelke, the old-timer trapper previously mentioned, came down to the shore, stood in the back of his canoe and paddled right to the spot where I had yelled and there was the stuff, scattered over an area of an acre or so and in 16 feet of water. Al was high on the ridge back of Coolin when my yell ca to him in the still, clean air, and he naturally did what Willis and I failed to do. He picked him plenty of line markers.

We recovered everything except Swim's new $30 saddle, and spent a lot of time looking for it. The barge had headed up the lake. One of the severed hawsers had left a trail on the lake bottom until the water got too deep. That afternoon when Walter Slee, a parapalegic who made a trip around the lake with his steamer every day, got in, he reported that he had seem the barge in Soldier Bay. As I recall it, this was about 2-1/2 miles, and quite a trip for a waterlogged barge to make overnight. We went up and got the barge. And here, in the well deck which was awash with water, was Swim's saddle. Incidentally, the tracks showed that the horses took the shortest possible course from where they were dumped to the shore, clearly indicating that when it came to navigating in the fog, all our technical training, experience and instruments were nothing compared to a little horsesense.

* * * * *

An incident which shows the primitiveness of the Kaniksu in 1911-1912:

Toward the end of the 1911 season Mike Ne was handling the pack train. He needed a horseman assistant for a trip where we were doing some impossible packing, so I was chosen. At this time there were just two settlers in the vast country from Priest Lake west to the divide. One was a Swedish family, name forgotten, but I believe it was Swanson. The other was Mr. and Mrs. Tony Lemly. Mrs. Lemly was quite a character, which is beside the point. The point is, Mike and I stayed there overnight and then went on. This was probably late September.

In 1912 I was on the Kaniksu again, but in a different capacity. I was now under appointment and working out of the district (now regional) office. I had picked up Mike in Spokane as assistant. Eventually we got around to Lemly's. Mrs. Lemly led us straight to the bed we had occupied the year before and showed us Mike's necktie hanging on the head of the bed. We were the first people she had seen, other than Tony, since we had been there with the pack train the fall before. Tony had been out as far as Snider's once.

Mrs. Lemly told us why her elderberry wine was good while Mrs. Snider's was, according to her standards, no good. She wormed her berries while Mrs. Snider did not. Now you can have all of my elderberry wine either wormed or wormy, but just in case someone is interested in the technique this is the way Mrs. Tony described it: It seems that elderberries are infested with tiny white worms which most of us never notice and here's the way to get them, if you want them. Put the berries in a big kettle and let them slowly come to a simmer. There will be a quarter inch of white scum on the top of the water and that is worms. Skim 'em off. It's as simple as that, although it seems to me this just impoverishes the wine.

During the 1912 season Mike and I had occasion to board with the Swedish family for a while. The meals were a bit limited, and identical. They consisted of boiled potatoes — no butter or anything — and corned bear meat. Now I have no squeamishness about bear neat, although I have never eaten any that was any good. But this at Swanson's was much worse.

We paid 25 cents each for those meals and I reckon that money was the first those poor people had seen in a long time. This was long before per diem and we supported our expense accounts with subvouchers. I fixed up a subvoucher for my meals and lodgings for Mrs. Swanson and asked her to sign it. She did and then seemed a bit embarrassed and uncertain. I asked what was the trouble and she indicated the line following the signature:

_________________Title. She apologetically admitted, "We have no title. We're just common people."

* * * * *

I do not know whatever became of Mike (Albert H.) Nee. He was quite a character himself. He was listed as a District Ranger on the Gallatin for years but has been missing from the directory for a long time.

The summer guard at Priest Lake was Fred Greene. I picked up a number of important points concerning nature and forestry from him. For instance:

That a forest guard should grease his shoestrings, carry a canteen, and smoke Westover (a plug smoking tobacco of that day). Then he always has something to do.

That Squaw Fish are so called because they give up so easily when you catch them.

That forked logs in the drive are called "schoolm'ams" because they won't roll over when you ride them.

That to make fireline coffee you take a cup of coffee to a cup of water, boil till it will float a wedge, strain it through a ladder, and eat it with a fork.

Unfortunately, Fred wasn't to spend much more time educating young foresters. He had a stump ranch adjoining Lemly's. He and Tony didn't see just eye to eye about some trifle and he was too slow on the draw. The result was Tony left that part of the country, but not soon enough, he had to accept a contract do to Walla Walla on a rather confining job.

* * * *

The real cut-up of that country was Ralph Sparks, the cook. We had to watch that guy all the time. Not that all his tricks were bad. One day in huckleberry season two cruising crews of us played hooky just to see if the berries on Old Baldy were as grand as we had heard, and darned if we didn't run into Benny (Arnold Benson) up there. Well, the berries were even better wonderful—so we filled every container we had, or could improvise, and took them to camp. We wouldn't have dared take any in if we hadn't run into Benny. The next might when we went into supper here was a whole huckleberry pie on each of our plates. I know I polished mine off.

One time we needed a bench mark in a valley for aneroid control. The nearest BM was on a mountain plenty far away. Benny decided to go get it. As I had had a couple years in the Reclamation Service between high school and college I was the logical candidate for rodman and was elected. We would have to make the trip on foot, carrying the surveying equipment, plus bedding, plus food. It wasn't killing but it was fairly tough and we couldn't take any surplus dried stuff except one can of tomatoes. With Sparks' shenanigans in mind we stopped out of sight of camp and looked into our packs. Sure enough Benny had two nice sticks of firewood and I had a five-pound rock that I wouldn't really need. Those articles were just smokescreen, though. When we reached the point of desperation where we opened the tomatoes it was pumpkin.

Another time I took a string of horses into a camp where Ralph was cooking for one of the "squirrel camps." I dropped some of the string and was going on with the rest to the next camp. As all the horses would be needed for packing, I was riding a pack saddle, and on a horse that I couldn't trust -- that's why I was riding him. I had thrown some canvas alforjas across the saddle, but you can't be comfortable on a pack saddle. After I left Sparks' camp the saddle was even worse, and then remembered. Two nice pine knots from the woodpile worked under my alforjas cushion.

* * * * *

Yes, I know. "Squirrel camp" sounds like maybe a field party, for a nuthouse. That wasn't it, though. The year 1911 was a wonderful seed year and the Service really stocked up on western white pine seed. Several camps were organized and worked the area between Priest Lake and the Pend d'Oreille River. All available labor from the forest and farm communities was used, and in addition many laborers from the Spokane market—and they weren't all woodsmen. The camps were squirrel camps because the principal method of gathering was to prowl more or less aimlessly through the woods watching for squirrels. The squirrels would lead you to their caches, which you would rob, not without objection from the rightful owners. The cones were sacked and stood along the trail for pickup by the pack trains which were covering the country being worked. I believe the pickers were paid $1.50 per sack. The payoff was finding all the pickers at the end of the day. Some were lost nearly every day and had to be rounded up. Most of the nonwoodsmen would lose their heads and then trails and telephone lines meant nothing to them whatever. A pair of them actually waded across Priest River, although they couldn't help knowing that they were all camped west of the river.

* * * * *

Getting lost in the forest is nothing to look forward to. Lone wolfing as much as I did on boundaries, classification, appraisal work, etc., I was lost a number of times. I was never panicked at all, though, and so always got out with nothing worse than temporary discomfort. Some do not do so well. I remember one fellow in Montana. This was on the West Fork of the Flathead in 1914. The country was then utterly primitive. We were camped at Lion Creek. There were several cruising teams of us. One pair, who represented the State of Montana, were what you might call town woodsmen. I mean they knew their stuff reasonably well and were competent but they were Butte boys and their personal lives centered in Butte. Well, one night they didn't get in, and didn't get in. We finally decided they had got lost but that was nothing to worry about. The weather was fine and they would straggle in the next morning. As it turned out, though, they had separated.

The cruiser had found a cabin and holed up for the night. The compassman, who was 6 feet 4 inches, had just torn through the brush harder and faster as night approached — a long process up there against the Canadian line in midsummer. We had 3 or 4 tents in a clearing not 50 feet from the trail.

Also, we had a brisk fire in the open and were gathered around it. It was just beginning to get fairly along toward dark, possibly nine o'clock when we saw Murph coming up the trail with huge and frantic strides, his eyes as big as saucers. Naturally we said nothing as he approached until it was obvious that he wasn't going to stop at all, but to tear right on, practically through the camp. Then we tried to holler him down, but without any more impression on him than our blazing fire had made. Looked like we would have to shoot him to stop him. Some of the boys ran him down and brought him in. That man was a wreck and he hadn't been lost over five hours.

* * * * *

On our field trips from school we sometimes used a canvas-bound, pocket— test Woodsman's Handbook. On the Kaniksu I was gratified to meet the old grizzly bear who wrote it. Afterward I was associated with him for a few years in Region 6. I never got to know Austin Carey particularly, though, and doubt if there were many who did. However, one story lingers on: In those days, and perhaps yet, Washington, D.C. girls who wanted jobs in Washington had to establish residence in some state to make the apportioned roll. The western states were the ones with frequent vacancies, so many girls came west for the specific purpose of qualifying and returning in the Departmental service. Two such girls came to Seattle in the summer of 1914. One got ajob downtown and, before her year was up was married, as frequently happened, and swapped her interest in Civil Service for domestic service. The other got a temporary job on the Smoqualmie Forest. She didn't get married but by the time she was qualified for the exam she wouldn't have gone back to Washington if she could have had it all, so she took the Field exam instead of the Departmental - and accepted an appointment in Alaska. She went to the Snoqualmie office to tell the crowd "Goodbye." When, in the supervisor's office, she offered her hand to Smitty (Stanton G. Smith), the supervisor, a handsome young devil with a sharp glint in his eye. He said, "Don't think you are going to get off that easy." He grabs her and is kissing her with mucho gusto when Austin Carey walks in. Austin doesn't say a word. He just glares, gives with one of his snorts and strides through a succession of three empty rooms. In the far back room Andrew G. Jackson, afterward the first Public Relations man in Region 6, had just caught and was similarly treating the attractive and provocative Miss Ferbrush when Austin broke in there. "Looks like a good forest. Guess I'll stay here," he said.

* * * * *

LAND EXCHANGE I am the only veteran of the first big land exchanges, in fact, the only forester who was shifted from region to region on these jobs. The basic idea was to clarify the State's title to school sections unsurveyed at time of withdrawal of the forests, and to consolidate their holdings. Special laws were required and these were on the basis of equal areas and equal values. The pilot exchange was with South Dakota. It was small, around 20,000 acres, I believe, and was cleaned up in 1910. I had nothing to do with this exchange.

In the spring of 1912 I visited the office of the Boise Forest to see whether Supervisor Emil Grandjean could keep me occupied pending appointment. He introduced me to Charles L. (Deaf Charlie) Smith, who had been a trouble-shooting supervisor on a number of Region forests but was now detailed to organize an exchange with the State of Idaho. I was the first man hired for the job, on a 6-months' Timber Estimator appointment, the only one retained after the end of the season, and did not get away from land exchange work until the fall of 1927.

In those early years the lumbermen did not regard our professional attainments very seriously, and so our reconnaissance methods were not used. With the exception of myself all the fieldmen were regular commercial cruisers and compassmen and each used whatever cruising method he preferred. The general difference from our method was that in all cases a two chain strip was tallied and usually the average tree method used. Notes were usually posted at each tally (5 chains) only. All employees were investigated, and approved, by both sides. These conditions, established on the Idaho exchange, or possibly the South Dakota exchange, held also for the Montana, Washington and Oregon exchanges which came along in that order.

One of the candidates on the Idaho job, a charming chap named Ben McConnell, was looked at very much askance by the Forest Service selection board, for reasons of suspected instability of character. However, he was the son of Idaho's first Governor, one of his sisters was married to Ben Bush, the State Forester, with whom we were working, and another was married to a young Boise attorney by the name of William E. Borah, even then in his second term in the U.S. Senate. With these factors properly weighed Ben qualified with a high score. In the final analysis it developed that Ben had us all sunk for the superb quality of his reports and maps. They should have been good. He had borrowed the forest's extensive reconnaissance report and worked his reports up from that in the backroom of a saloon at Kooskia, Idaho. As a generalization: The fieldwork on these early exchanges suffered seriously, so far as any individual tract was concerned, from the lack of time and money available. Practically all the school sections were still unsurveyed, and were sometimes 25 or 50 miles from a survey. Nothing less than an official GLO survey could say where a section might fall. The plan used was to take the projection as shown on forest maps and locate the individual sections from cultural, drainage, or topographic features as shown on the best maps available. A thoroughly unsatisfactory system to all of us, but one presumed to average up over the job as a whole.

The Idaho exchange was pushed through to completion in 1912. Since two Regions (1 and 3) were involved, it was handled directly from Washington for the most part. Associate Forester Bertie Potter made it his baby and Charlie Smith, in charge, corresponded directly with Washington. Quincy Craft, Fiscal Agent at Ogden, handled the funds. Both regions naturally took quite an interest in the project, and in the final phases we saw quite a bit of E. A. Sherman, then District Forester of Region 4, Ferdie Silcox, District Forester of Region 1, Ovid Butler, Chief of Silviculture at Ogden, and of both Mr. Graves and Mr. Potter. In fact, Bertie stayed a week or more and dug right in on compilations and tabulations with the rest of us in preparing the proclamation winding up the job.

By the time the Idaho exchange was out of the way the Montana exchange was authorized. This was handled in the same manner as the Idaho job. Charlie Smith was in charge, but now entirely under the regional forester. Through the accident of being the only other career forester attached to the project, I was after only six months on permanent appointment, in effect, assistant to Smith - a job a deputy supervisor should have had. I did handle a field party both years in Montana, however. In 1913 we cleaned up the state base sections on all forests. I cruised out some tag ends on the Missoula Forest in December in 12-below-zero weather. In 1914 I ramrodded a party which cruised out the selection area on the West Fork of the Flathead River in the Flathead Forest. This was fairly remote at that time. To reach it we traveled by Model T stage from Kalispell to Big Fork, some 20 miles. Then 8 miles by lumber wagon to the foot of Swan Lake, 7 miles up the lake by boat, then 20 miles or so by pack train. I went in in April and came out in October. But it wasn't bad. We had mail every week or so. A few sessions like that would do wonders for some of these modern J.F. sissies who cry if they have to stay out over the weekend.

Smith and I did not see the Montana exchange through. Having finished the fieldwork in 1914 we were sent on to Region 6 in the spring of 1915 and got the Washington exchange under way. Charlie Smith was soon withdrawn for a detail over around Yellowstone National Park and another Smith — Stanton G. (Smitty) — Supervisor of the Snoqualmie National Forest at Seattle, replaced him. Smitty did not give up his supervisorship, however, but commuted between Portland and Seattle, so I was "acting" much of the time and did no detailed fieldwork. This exchange, which was a big job, was caught by World War I, and by changing state administrations, and dragged for many years. I do not know whether it is all cleaned up yet. Before the Washington exchange was out of the way we organized a similar but relatively small one with Oregon. A primary objective of both the Washington and the Oregon exchanges was to provide state forests contiguous to the forest schools. I do not now recall the acreages involved in these early exchanges, but it seems to me that Idaho's was around 100,000 acres, Montana's 250,000 acres, Washington's over 600,000 acres. These early exchanges at least cleared the air of the notion of "equal area and equal value" and built toward the more practicable policies of equal value and of timber for land.

As private exchange legislation became available and policies began to shape up we came to feel in Lands that it was time for a handbook. Since we conceded that we in Region 6 were way out ahead in exchange activity it looked to us like our job. Therefore, C. J. Buck, then Chief of Lands, wrote an outline. I wrote the bulk of the text, with help from him and from his secretary, Althea Wheeler, while George Drake, recently president of SAF, helped with the timber appraisal section. We sent it in. Leon F. Kneipp wrote us that our handbook was received with three rousing cheers - that it was exactly what was needed. In due course came back the official text. We examined it with interest. There wasn't a line or a paragraph that we could recognize.

* * * * *

Some of the later land exchange acts permitted us to take over isolated tracts of public land within what had been set up as our ultimate boundaries. These were generally small tracts, 40 acres to 120 acres. It was usually my job to examine these tracts and report them. As they were widely scattered I worked them alone - a job I always liked. One year I had a bunch of these tracts to pick up contiguous to the south unit of the Umatilla National Forest in eastern Oregon. Associate forester E. A. Sherman was in the region and wanted to see how we were handling that work so he came over there from Portland with C. J. Buck and joined Johnnie Erwin, the supervisor, and me in the field. We had occasion to stay at Heppner one might, a small town off the beaten track. C. J., who had been on a trip to Alaska with Sherman, had filled Johnnie and me up on what a terrible snorer E.A.S. was, and how sensitive he was about it. He was sure sorry for anyone who got stuck to bunk with Mr. Sherman, as might be necessary in that small town hotel. Johnnie, Sherman, and I went to the hotel to register, while C. J. proceeded with bedding down his Franklin — a meticulous process. Johnnie and I were each looking to doublecross the other, or better yet, C. J., when the clerk asked us how we wanted to double up. Sherman took the play right away from us. "I don't know about you boys," he said, "but as for me, I always say I'll sleep with no man, and with damn few women."

I had some scattered tracts to examine on the Lostine drainage of the old Wallowa Forest in extreme eastern Oregon. I got some dope on lines and corners from a rancher who had a ranch right where the Lostine comes out of the mountains. The river spread out a bit here with quite an area of gravel bars with stringers of willow. His horses, including a white bell mare, grazed over this land. A couple of months after I left came the deer season. Some railroad men from LaGrande were camped there on the Lostine, with the rancher's permission. One evening he thought he would visit them so he hops on this mare and hazes her over to their camp. As he rides into camp one of the hunters shoots him dead, off this white mare with a bell on her. No, I presume nothing happened to the hunter. He didn't mean to. He was drunk.

A hunter above Sunset Falls on the Columbia Forest tied his horse and to protect the horse spread his red jacket over the saddle, then circled through the forest. When he got back the horse had been shot dead. Maybe he shot it himself, I don't know.

So many hunting fatalities I have been in on one hunter will say, "You go up this ridge and I'll go up that one and we will meet in yon pass." And the one who gets there first sits down and wait and then when the other one comes bursting out of the brush he up and shoots him.

Sam Ward, an amigo of mine on the Gila Forest, was sitting down sounding a turkey call when a kid from Las Cruces shot him right through his red cap. The kids, there were three of them, took a look at him and hightailed for home - no report.

I have never understood why people who have conclusively demonstrated their incompetence to handle firearms, or cars, are not grounded for life — not as punishment, but just for the protection of the rest of us.

* * * * *

Among the early foresters in Region 6 were the Allen brothers, G. F. and E. T. E. T. (I never heard another name for him) was one of only two forest officers who addressed my class at Idaho. He was the black sheep of his scholarly Harvard faculty family. As I recall it, he did not even finish grade school but ran off to the South Sea Islands. Of course, he didn't ever amount to anything. He was only the first - no, I guess second - district forester. I think C. S. Chapman was the original one. E. T. is credited with having designed the pine tree badge. By the time I got out to Region 6 in 1915, E. T. had already gone to a job with the Western Lumbermen's Association at just twice the salary the forester was to receive for many years to come. G. S. was supervisor of the old Rainier Forest with headquarters at Tacoma.

One night C. J. Buck and I, seeing a light in his window, went up to Allen's office. In the course of the evening he told a story which impressed me:

George Griffith, the silver-tongued orator of Region 6 and an excellent man in PR, was then forest clerk on the Rainier - but that wasn't where his heart was as Allen told it. George, who was spending entirely too much time away from his desk and on his real love, took advantage of a time when he could sign as "acting" to instruct each ranger to submit an essay on how the forest officer could best advance public relations. It was the height of the field season and an inopportune time for writing compositions, but eventually all the rangers came through, with the exception of John Kirkpatrick of the Randle District. John, the father of Dahi Kirkpatrick, now chief of TM in Region 3, seemingly was unimpressed. George waited until again he was "acting" and then he put a sharp prod to John. He got results. John replied to this general effect:

"In my opinion, the best way for a forest officer to promote public relations would be for the forest clerk to quit gallivanting around and clear the 5A (now 10314) vouchers for payment. Everybody is complaining."

I was in the Missoula office two years, 1913 and 1914. Missoula is said to be in "banana belt" of Montana since it seldom drops below 20 degrees below zero, night and day. It seemed pretty tough for me, raised in the Boise Valley, which is exceptionally mild for that latitude. When my transfer to Region 6 (Portland) was requested, I was glad of the chance to get away from Montana's winters. The fellows in Missoula, though, all thought that I was crazy to go. Two adverse factors developed:

1. Everybody in Portland wore derbies - all colors - because it rained all the time and the derby was the only hat which would take it. This was not true. The derby was still extant in 1915, but there were no more of them worn in Portland than elsewhere.

2. All the parkings in Portland were occupied by huge piles of cordwood. This was essentially true. All through the dry summer the wood haulers would be delivering 14-foot second growth fir, much of which would now go for good, grade lumber. These piles, often 8 and 10 feet high, would season until along toward the rainy season, then portable wood saws would come along and saw them in the street. Then the stove wood went to the basements. The firewood sellers would stencil their names repeatedly on the ends of the stacked cordwood. One of the best known companies was "Neer and Farr."

The one forest officer to address us at Idaho, other than E. T. Allen, was Bill Weigle, then supervisor of the Coeur d'Alene Forest, but soon to go to Alaska. Bill was in Alaska many years but eventually came back to Seattle. As he told it himself, he wasn't entirely happy in Seattle for the reason that he had been a big frog in a small puddle in Alaska, and in Seattle he found that he was a very small frog in a big puddle.

Bill was, and no doubt still is, a pretty keen investor and he was better off than the run of us. One year he brought a brand mew Buick sedan to supervisor's meeting, while most of us were still driving Model T touring cars. Naturally he was proud of it and kept it immaculate. On a field trip Cy Billings, the rough-hewn old supervisor of the Wallowa Forest was riding in the front seat with Bill. He knew how Bill hated smoking so in deference he confined himself to a big mouthful of "Horseshoe." He held it as long as he could, but when he reached the limit he had to let fly - out the window. Only trouble was, the glass was up. Cy just wasn't used to cars with glass windows, and spotlessly clean ones at that.

Bill, now up in the eighties, is living in Pasadena. I believe the next time I am in Los Angeles I'll go see him - just to see what a really old forester looks like.

* * * * *

Amy Jane McGuire, long since transferred to her Unitarian heaven, was quite a figure in the old days in the Portland office. She would get in the elevator and say, "Central, please," or board the streetcar and say, "Fourth floor, please." There were always new "Amy Jane" stories, and they were always true. You don't have to believe this one, but it is true, and typical: There was a long-carriage typewriter on an ordinary typewriter stand against the wall in the room occupied by Mineral Examiner M. W. H. Woodward and myself. Amy came in with some odd job which she put in the machine. Then she sat down in the chair which was out maybe 3 feet from the table. She looked rather bewilderedly at the machine, which she could not reach, and then the solution came to her. She got up and moved the stand out to the chair, typed the job, moved the stand back to the wall and went back to her own branch.

In our offices in the old Beck Block (prior to 1919) there was a room clear around the corridors to the right. This room was about the size of the average office, but different: There were closed booths with swinging doors along one wall and open booths, very shallow, along the opposite wall. It was known as Frank Law's library. One morning Adam Wright was standing in one of the shallow booths contemplating the wall immediately ahead of his nose when he heard a gasp behind him. Here stood Amy Jane, right in the middle of the room, hands clasped on her chest and a definitely stricken look. Adam turned back to his own project to give her a chance to escape. To his amazement she waited for him and went out with him. She said, "Isn't that the queerest thing? You know, I did that once before, too."

In the early twenties I was driving a Model T with a factory built "sportster" body. As the new building was down by the river and I went right through town; I seldom rode alone. Somebody always wanted to go to "Olds 'n Kings." One evening it was a very young girl from Amy's office. She was telling me how specifically Amy had warned her against accepting any rides in autos with men whether she knew them or not. This rather amused the girl because those were just the rides she was rather inclined to accept. Now it so happened that the very next night when I got in my car alongside the lower park block I saw Amy Jane heading toward town on the diagonal path through the block. Also, for once, I was alone. I wanted to see just what kind of a rebuff she would dish out so I timed myself to reach the far corner just as she did, and invited her to climb in. Much to my surprise she did and, from her manifest pleasure, it was obvious that she had had a few rides in automobiles. As we approached "Olds 'n Kings," the usual destination, I asked, "Where would you like to get out, Miss McGuire?" Her reply floored me: "You just go wherever you want to, Mr. Teed, and I'll walk back." I didn't though. It would have looked bad in my personnel record. But she was having so much fun that I did take her the long way around.

Along in those same early twenties the Portland Journal had a girl reporter named Henrietta McCoughan (pronounced McCoin), who was nuts about nature and specialized in that field. She did much valuable work for us in the way of publicity in those days when our recreational policies were incubating. Naturally, Lands was her hangout and she depended on Woodward, Fred Cleator, and me for photographic instruction. One time C. J. Buck and Fred Cleator had her up to Eagle Creek camp on the Columbia River highway. As anyone knows who has been there, this exceptionally beautiful gorge is practically always deep-shaded and very damp. It is never comfortably warm. As C. J. told the story the next day: They had a fire, against the chill, and they and Albert Weisindanger, the ranger, were standing with their backs to it when a caliber .22 cartridge in the fire exploded shooting a fragment of the copper shell into the southern exposure of the gal reporter. This, according to C. J., raised the delicate question whether she should continue to suffer or should submit to assistance for an operation she could not perform alone. Now, as was typical of C. J., he left this story hanging up in the air right there, and would tell us no more. Within the last 4 or 5 years Reader's Digest had a story about a rather famous editor and his newspaper of Anchorage, Alaska, and doggone if his sidekick these last many years isn't Henrietta! She is now a full-fledged sourdough. I wrote her a letter and asked her what was the end of that story. She ethphatically denied the whole thing, while recalling those old times and C. J. and Fred, and Albert. Only one thing - she doesn't recall me at all. That's not so strange, though. I never did take her on a field trip.

* * * * *

Albert Weisendanger, for many years the ranger at Eagle Creek on the Mt. Hood Forest, unquestionably had a wider acquaintance and more influential friends than anyone else in the district. He was a natural at PR work as he was a gifted entertainer - especially for school kids, as well as a truly enthusiastic salesman of forestry and protection. Albert had already been promoted from messenger to mail clerk when I reached Region 6 in 1915. According to the story then extant, this is how Albert got his first appointment: Always aggressive when as a school kid he was called for an interview by Charley Flory, then chief of Operation. Albert did the interviewing. He learned that he was No. 3 on the eligible list and that he would be reached for appointment only in case both Nos. 1 and 2 turned the job down. Then he got the names and addresses of Nos. 1 and 2. He sought out No. 1 and convinced him that he would be crazy to quit school for a mere messenger job, which probably would peter out in a short time anyhow. Then he hunted up No. 2, but he couldn't talk No. 2 out of accepting the job so he beat the whey out of him, won the argument that way, became the No. 1 eligible by elimination, got the appointment and embarked on a long and valuable career in forestry.

* * * * *

By 1927 a health condition in my family made it imperative that I give up the long periods away from home, so with the greatest professional reluctance but with gratitude to C. J. Buck, Chris Gran and A.O. Waha for making it possible, I crossed that great abyss which separates the forester from the clerk and became administrative assistant on the Columbia National Forest at Vancouver, Washington. There, chair borne, I sat out the New Deal and the multiple alphabetical agencies.

The CCC would be a book in itself, but I will leave someone else to write it. How we missed the boat at first, figuring that it would only last 6 months, when it lasted as many years! One thing which particularly amused us was the embarrassment which the D.D. qualification for facilitating personnel evidently caused Washington, and how it eventually stumbled upon the clumsy substitute: "Departmental Designee" to justify the initials.

In southwest Washington we had a representative, Martin Johnson, who took the "deserving Democrat" requirement in his stride. He just put anybody on his list who sent him a postcard. We had from his list the longtime Washington district highway superintendent who was a bred-in-the-bone Republican and no small figure in the party; also, several good men from the Portland territory who didn't even reside in Washington.

In the fall of 1942 the regional office contacted me. Would I be willing to go to Salinas, California, on the huge Guayule Project. I told them no, that that was a better place for the young guys, if it was alright with the regional office, and it was. I was 55 years old and had over 30 years' service. We owned our home in Vancouver, had lived there 15 years, and expected to retire there in a few more years. Then, the day before Christmas, Arnold Standing, Chief Personnel, called me and told me that I was being transferred to the Guayule Project, not in California, but to El Paso, Texas, and that I was leaving the day after Christmas. Some notice, huh, for a 2,000-mile permanent transfer. Well, I left, but, of course, I couldn't do a thing about the family.

Months later, when my wife had disposed of the place and was ready to move, I told her just not to have a concern about the household goods. The Government would pay the costs and the Mayflower boys would take care of everything. They did alright - even to about a hundred empty mayonnaise jars, several outdated mail order catalogs, and a considerable assortment of Model T parts the kids had dragged in over the years. My personal share of the cost was $333. That hurt. But, I thought that the payoff came several months later when Fiscal Agent Edd billed me for an additional $9.99 tax.

* * * * *

In my observation, Guayule - the emergency rubber project - was a proven success and reflected great credit on Evan Kelley, Paul Roberts and the many others who gave of themselves on a war emergency basis. However, by mid-1944 it was obvious that the banker-farmers of Kearn County, California, and the synthetic rubber interests had us licked politically. I found, though, that after two years in the southwest I had become a sun worshipper and had no desire to follow my "line of retreat" back to the west side of Region 6. Region 3 was willing to absorb me so I put in my final stretch on the Gila National Forest in southwestern New Mexico, with headquarters at Silver City.

In the spring of 1952, after several years of prodding by the Regional Retirement Board, I finally sent in my application for retirement, dated for May 31, the day following my 65th birthday.

Shortly after my application went in, Eddie Tucker, the supervisor, came to my office with that little smile of his which showed that he had been in the cream again, or was headed that way. He had a letter in his hand. The regional office, it seemed, wanted rough drafts for three letters, one each for the signature of the regional forester, the forester, and the secretary. I could read it in his face - it was his sense of the fitness of things that I, who had prepared so many of these sets, should prepare this last set as well. I thought it, was a good touch, too. "Sure I'll write 'em I told him. And I called in Mayme Duncan, who did the "confidentials," and dictated one with a warm personal touch for Otto Lindh, the regional forester with whom I had long been associated in Region 6, and one with a friendly but less intimate tone for Lyle Watts, the forester who knew me only casually in Region 6 where he had been regional forester, and one on a basis of formal cordiality for the secretary, whom ever he might be. In due course, I received a farewell letter from the regional forester, one from the forester, and one from the secretary, and each was word for word as suggested. The copies went to my personnel folder, and after 41 years, 4 months and 15 days, another folder went to the closed files.

* * * * *

No account of the early days of Region 1 is complete without a chapter devoted to the Ammen sisters - Eva and Matilda. They were the daughters of an admiral, back in the days when admirals were very rare. They came out with the district organizations in 1908. Eva was librarian and Matilda was in the steno pool. I knew them only slightly during my two years in Lands, Region 1.

In the spring of 1915 the girls bought them a place. Matilda was working with me at the time. We were writing "Secretary letters withdrawing June 11 listings." Soon after the girls bought the place they began receiving seed packages in the mail, and they were big; pounds, half pounds, quarter pounds — even of fine seeds like carrots — all kinds of vegetables and flowers. Ranch-raised, myself, it staggered me to think of these frail spinsters with all this gardening to do. Finally, I asked Miss Ammen how much acreage they had. They just had one city lot with a house on it.

These girls seemed awfully old to me when I knew them in 1915, and I was 28. On my first visit to the Albuquerque regional office in 1915 Mrs. Dick Hillery asked me whether I knew them. I replied that I did, but that they must be long since dead. But no. Retired, of course, they had built themselves a picturesque house on the mountain overlooking Santa Fe where they were busily engaged in the translation of ancient Spanish documents; also, the Government had taken them on a trip to Mare Island to christen a destroyer honoring their dad.

Another of the old Region 1 small fry was John Quinn, the peppery mail clerk. John was a New York foundling and a confirmed bachelor. One time I went down to the stockroom and asked John for a couple of No. 2 pencils. He threw up his hands and yelled, "J—— C— ! How the h— would I have a No. 2 pencil in the house, and school starting Monday?" I had no kids at this time, myself.

I ran into John many years later when stationed at Vancouver. He had finally been hooked, married a widow with children. He was custodian for the B.P.R. at Vancouver. He was found on the floor of the office one morning with a fractured skull. He did not regain consciousness. Apparently he had fallen from a high stepladder while changing a ceiling light.

* * * * *

It was my fortune to know most of the Fenn family who had a considerable part in the early days of forestry in Utah, Idaho, and Montana. Major Fenn was supervisor of the Boise in my high school years. The older girl, Rhoda, was a classmate. Lloyd, past high school age, did some coaching in track work. At University of Idaho, Lloyd and I were charter members of the first forestry class, organized in 1909. Arlene, another daughter, was also a classmate there. Afterward either Rhoda or Arlene married George Ring, then supervisor of one of the North Idaho forests. While I was in Lands, Region 1, Dick Rutledge went to Ogden as regional forester and Major Fenn came in as Chief of Lands. Lloyd was there for a while, too; he was then under a ranger appointment. We had him coloring land classification maps. He had a lot of timber type areas colored bright red before we discovered it was all the same to Lloyd. Lloyd soon left the Service for a career as editor and school principal at Kooskia, Idaho.

Homer Fenn was Chief of Grazing while I was in Region 4. This was in 1912. I saw quite a bit of him at Boise. He had a famous saddle, made to his order by Frazier at Pueblo. Homer felt that, since he was in Grazing, it would be a good touch to have cattle and sheep included in the stamping design so he wrote Frazier and suggested a sheep for one stirrup fender and a cow for the other. We were rather delicate in those days and he didn't like to dictate a coarse word like "bull." He got a cow alright, a dairy cow, right side, with her hind leg back in milking position. This was a big hit with the stockmen. Homer left the Service early to become a sheepman.

|

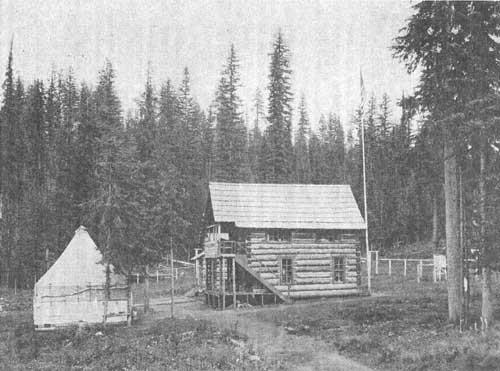

| Adams Ranger Station, Nezperce National Forest. 1925. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/2/sec15.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |