|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 2 |

|

October 1955

THE SNOWY MOUNTAIN FIRE OF 1900

By David Lake

(Retired 1940)

In order to better understand the conditions then existing, I will first explain how I came to be in the Snowy Mountains at the time of the fire.

For the three years previous I had been working for the 79 Ranch, officially known as the Montana Cattle Company. They had four ranches - one located on the White Beaver Creek near the Yellowstone, one on Painted Robe Creek, one on Big Coulee and one on the Musselshell near the present town of Barber. In the fall of 1899 I was working on the Musselshell Ranch. Since this was before railroads, everything used in this country was brought in by freight teams from Billings, and as I had been working for the 79 on and off for the past three years, I had not only learned the country but also how to handle four-and six-horse teams. The Company was planning on doing some bridge building, and as there was a small sawmill on Careless Creek on the south side of the Snowy Mountains some 30 miles distant, I was sent up to the sawmill to get the timber. During November and December I made three trips to this mill, bringing down the required amount of lumber. When the hauling was completed, since I was the youngest man at the Ranch in terms of service, I was one of the group that was laid off. Knowing that this was to happen, I had arranged for a job at the mill when I made my last trip up there for the Ranch.

Prior to coming to Montana, I had put in one winter in the lumber woods in northern Michigan, and I was glad to get a job in the woods again. The owner of the mill, W. S. Stranahan, was also a rancher and an old timer there. He had built this mill, a water power affair, and did his logging during the winter, hauling logs to the mill on sleds. He sawed the logs into lumber in the spring while there was plenty of water. He had built a small pond on the hillside, filling it by means of a ditch from Careless Creek. At his mill he had built a 40-foot pen stock with a flume extending to the pond. He would fill the pond and saw lumber as long as the water lasted. As a rule he could run about two hours, then close the gates and pile the lumber while the pond was filling. Lumber was in good demand as this was the only mill in that locality.

During the winter of 1899-1900, we cut and hauled to the mill around 100,000 feet of logs. We had an average snowfall that winter and good sledding all the way to the mill, a distance of about four miles.

The spring turned out to be dry. Little moisture in April and May and almost none in June. It therefore became apparent that there would be a shortage of water for sawing, so after spending a short time putting in some crop, Mr. Stranahan decided to outfit a freight team and send one man out with it hauling wool, and that he and I would do what we could at the mill. So, the ranch was stripped of wagons, teams, harness and saddles. One light team was kept at home, together with one light buckboard, and I, of course, had my own horse and saddle. The man sent out with the freight team to haul wool had a wife and daughter on the ranch, and they remained while he was away. Mr. Stranahan was not married at this time.

We sawed a little lumber, put up a little hay and did what else we could. The weather got hot, the grass dried up and everything had a bad look. It was about July 12 that we saw the first smoke. It seemed to be about northwest of the ranch, somewhere west of Timber Creek, approximately sec. 20, T. 11 N., R. 18 E., and like all unattended fires it burned up big some days and would then go down. Being far away we paid little attention to it. My boss, Stranahan, said that since he seemed to be in no danger he didn't aim to spend any time on it.

During a trip I made to the Halbert ranch, I met Ralph Skellen who had just come from Timber Creek. He had been working for the Halbert brothers, but that winter he and another man named William Williamson, had been getting out a setting of logs in Timber Creek. Skellen said they had been trying to save their logs, but that they had lost about one-half of their cutting. I was never able to learn just where the fire did actually start or what started it. For several days we had an east wind, just hard enough to move the fire westward. As long as it moved westward no one gave it any concern. (Many years later I found it did go west as far as Blake Creek - sec. 6 and 7, T. 11 N., R. 18 E.)

On or about July 15 a black smoke was seen on the Timber Creek ridge about sec. 20, T. 11 N., R. 18 E., and it came over the ridge and burned down the hillsides, threatening the Weber homestead on Little Careless Creek. Stranahan then decided we had better do something, so we started to the fire, leaving the ranch about 3:00 p.m. We both had a horse to ride, one man saddle (mine), and one side saddle. I took the side saddle. And here allow me to suggest to anyone similarly situated -- walk, in preference to any side saddle.

Each of us carried an axe and shovel. Bill, my boss, lined right out and I had to follow. At long last we arrived at the fire. We fought it until dark, saved the Weber homestead, and as it seemed to be dying somewhat we went home. The next day we filled the pond and again started to make some lumber. As I recall, we continued sawing for two more days, when the black smoke showed up. The wind by now had changed to the west, and the fire was at the head of the West Fork of Little Careless Creek, about sec. 16, T. 11 N., R. 18 E.

Bill now began to be worried. He saw that if the wind held he would soon be in danger. So, back we went. This time he took the little team and buckboard. I took my own saddle horse, rode over and got Len Weber, and the three of us started backfiring up a coulee (later called the Franklin Coulee). We first unhooked the team and turned the horses loose, leaving the buckboard. We worked until about 12 midnight backfiring, whipping out the east side and allowing it to burn westward. The main fire was getting close by now. We could see and hear it up on the bench to the west. (Here I want to note that we backfired that night as long as the grass would burn. This was on July 17. Later on this area was part of my ranger district. I watched it carefully and during the 20 years that I had charge of it, never again did I see the grass dry enough to burn on that date. This gives one an idea of how dry it was in 1900.)

At midnight we went to the Weber place and tried to get some sleep. By the next morning a 40-mile wind had come up, blowing straight from the southwest, and the day was one of the hottest I have seen in this country. We went up the coulee to see the effects of our backfiring. We didn't get far before we determined that it was of no value. The fire went over it and beyond. The benches were very thickly timbered, running heavy to Douglas-fir. Flames were shooting hundreds of feet in the air and the black smoke was reaching thousands of feet. While we were watching, the fireline grew to about three miles in length, and in a few minutes the line was way ahead. I saw one place where the fire jumped at least a mile and spread from there. Those big firs would actually explode. Lew Weber, who is still living and is at present a neighbor of mine here in Harlowton, had a piece of land nearby with a haystack and cabin on it. The fire was falling all over it. We found a spring and carried water, and as fire fell on the haystack we would put water on it. Within an hour the worst was over and the fire had gone on east and north. The few men who had assembled then began to scatter out, going east and keeping as close to the south edge of the fire as possible. Stranahan and another man nearly got trapped and had to run for it — and just did make it. I kept a little further down and came out at the top of the grade that led down onto the Stranahan ranch. Other than burning the fences, the ranch had suffered but little. By this time the sun had gone under the smoke cloud and it became so dark that traveling was very unsafe. The two women at the ranch had become frightened and moved all their belongings out in the center of the garden. They figured the ranch was doomed. The mountains were no longer visible, and while the fire could plainly be heard, we could not see it. The thousands of big firs exploding sounded like a great battle.

By noon the worst seemed to be over, and when darkness fell the smoke had blown away somewhat. Thousands of fires were to be seen on the mountain sides, one of the greatest sights ever witnessed. Another lad and I watched it until long after midnight. A light rain came in the latter part of the night, so in the morning there was nothing to be seen but smokes everywhere.

The Swimming Woman portion of the mountains had burned in 1885 and left a sharp fire line from the top of the mountain running south to the edge of the timber on the bench. So, when our fire reached the old burn it died out. This old burn being only 15 years old had not gone down enough to burn readily. So ended the first fire; the next was to come two weeks later.

The names that I remember of those men who attended the fire were;

| Name | Year Settled |

| William S. Stranahan | 1884 |

| Tom Halbert | 1883 |

| Bill Halbert | 1883 |

| Ed Marsing | 1880 |

| Ed Taylor | 1890's |

| Charles Ayers | Recent settler |

| Lew Weber | 1890 |

| Troy Porter | 1895 |

| Joe Healy | Native (half-breed) |

| David Lake | 1899 |

The fire in Timber Creek Canyon and Careless Creek Canyon continued to burn slowly, creeping up each side of the canyon, some days burning up quite big and then dying down. It could easily have been controlled, but as we had no leaders nothing was done about it. Both canyons contained heavy stands of mature Douglas-fir sawtimber.

Careless Creek Canyon contained about three sections. Well, things went along in this manner for about two weeks, or until August 8. Weather was still very hot and dry, and on this day we had a hard south wind and about noon someone at the ranch looked up and said, "Boys, the canyons are going up." These canyons opened up to the south and the wind had a good sweep.

Within an hour the whole canyon was like a furnace, the flames shooting to the top of the mountains and a huge column of smoke rising thousands of feet and drifting off to the east. The heaviest volume of fire lasted for about two hours, and then began to die down.

Careless Creek Canyon burned out completely. Something happened in Timber Creek, as only a portion burned, leaving around 15 million feet of mature Douglas-fir which is still green, and still being sold. And 20 years later (1920) it became my job to start the sale of this timber.

On the mountainsides where the fire was the hottest, the soil burned off completely, and practically no reproduction has ever started. On the benches and in the canyon bottoms where some soil was left, a good stand of young timber is now growing.

During the years of 1910 and 1912 the Forest Service did considerable planting on the South Snowies burned areas, most of which was successful. In 1920 or 1922 I made the last and final progress reports on these plantations.

There were several old-time settlers at the Stranahan sawmill on the day of the Canyon fire, and I am giving their names as a matter of record:

William S. Stranahan

P. J. Noule

W. A. Hedges

Tom Halbert

David Lake

I am sure that I am the only one now living.

|

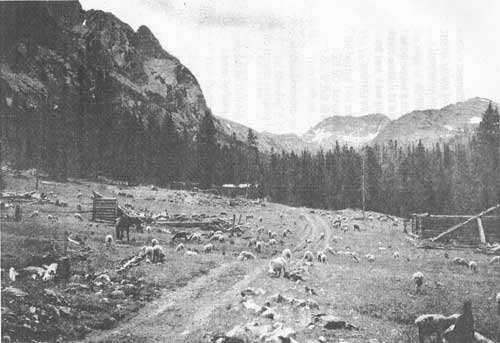

| Sheep on their way to summer range, grazing at the ghost town of Independence, near the head of Boulder River, Absaroka National Forest, 1936, now the Gallatin National Forest. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/2/sec6.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |