|

Early Days in the Forest Service Volume 2 |

|

October 1955

RECOLLECTIONS

By Roy A. Phillips

(Retired 1951)

To record experience factually over a period of 41 years is a big job and one that can well be approached with some measure of humility and trepidation. For anyone who put forth an honest effort to do his work conscientiously and well, the early years of the Forest Service represented a very grueling and at times an exceedingly discouraging life, requiring courage, patience, and fortitude in an exceptional measure. It was a lonesome life, and to work alone under severe physical and many times mental handicap was a part of the daily routine. As few trails and almost no roads existed, it was necessary to work a way through heavily timbered, rugged mountain terrain for days on end to gain a familiarity with the territory for which responsible.

A fire guard in those days often had to patrol areas the size of present-day ranger districts, and the task of getting around over his district represented days of severe physical effort. No lookouts existed and the patrolman viewed his area from high vantage points as he traveled around on his beat. If he sighted a fire he went to it and if true to his trust, stayed with it until it was out, with the hope uppermost in his mind that nothing would happen elsewhere until he again got back into circulation. Sometimes with hands and feet blistered and even his body galled by sweat he kept on day by day with little to eat and almost no sleep.

Although I had worked and held down a man's job from the age of 13, at the age of 20 the life was so hard that I often thought of going back to a job where, as a rule, they worked only from daylight until dark. I well remember what Ranger Frank Haun, my first boss, used to say when someone became dissatisfied and wanted to quit, "Well, you hired out to be a tough man, didn't you? Then what are you beefing about; who the hell wants to be a quitter!" This thought braced me many times in later years and I would grit my teeth, cinch up my belt and keep on going.

To be resourceful and self-reliant and overcome obstacles no matter how overpowering they might seem was another trait essential in an early day ranger. For example, when a forest fire broke out in the vicinity of Taft, Montana, Frank could not get anyone to turn out to fight the fire so he went up on the mountain back of the town and put in a fireline exposing the town to the fire, with the intention of stopping the fire after it had consumed the town. When the local people saw what was going on they turned out with a will and helped subdue the flames.

Another time a couple of hombres with bad reputations decided to file a squatters claim on a bar having agricultural possibilities and Frank took me along to help move them off. They were busy building a cabin and scarcely paused to talk to us, but told us in no uncertain terms to get the hell off their land before they put us off. Frank sat down on their coats, which at the time I thought was strange, and after we had talked and argued with these fellows for a couple of hours their activity on the cabin gradually ceased, and finally one said, "You win," and to his partner, "These persistent s-of-b's won't leave us alone; let's go," and picked up their coats under which were two 45 colts. Frank had suspected this so sat down on their coats to make sure. The exploits, of Frank Haun would fill a volume. He was one of the colorful early day rangers. I was fortunate indeed to serve as his assistant for about two years and consequently got some very good training that was of great value many times in later life.

The patience, fortitude and will power to overcome human and physical obstacles, a la Frank Haun, was indeed necessary in the repertoire of an early day ranger. In those days the public was very antagonistic toward, the Forest Service, since it was generally believed by those with whom we came in contact that with the creation of the national reserves, resources that were heretofore free to the public had been locked up from entry and exploitation. I learned that to mingle with these people and to avoid heated arguments would almost always get the desired result, and that once you gained their respect and confidence you could get them to do anything within reason. Therefore, over the nearly 30 years that I was a supervisor, I tried to instill within the rangers under my direction the lessons taught me by Ranger Frank Haun. As a result, very few complaint cases ever got past us and those so settled, with few exceptions, will ever become known to a higher authority.

In the early days of the Forest Service a great deal of weight was given to the way a man did his job and of his standing in the community. In late years, however, it does not seem that this is always true, but that if a man stirs up a lot of trouble and even if his morals are a little out of line, he is considered as a go-getter and shoved up above more deserving men and the condition of the resources for which he is responsible has not, to my observation, been given very much consideration.

Rangers and supervisors have become office bound and paperwork drudges. As foresters they are getting farther and farther away from the trees, and consequently, very far away from the people they serve. It seems to me that effort in recent years has been concentrated on people living away from the forest in an effort to educate the public as a whole, mainly to financial needs. The reaction by permittees and forest users generally has not been too good, and there has been some pointed criticism of show-me trips even by some of the people who have been taken on these trips. I do not make a point of this to discourage the present I&E programs, but wish to emphasize the need to get back down to earth, practice forestry on the ground, and deal more closely with the forest users as a class.

That I ever made the grade as a Forest Service employee was due to the fact that I served under such men as Frank Haun, Elers Koch, Glen Smith and Fred Morrell. Perhaps I should mention Major Kelley but he came along after the time I had emerged from the quenching bath and was by then pretty much tempered metal as far as the final stages of development are concerned.

Elers Koch, my first supervisor, while a hard taskmaster, was a fair man and delegated authority to a greater degree than any of my other Forest Service bosses. As long as you redeemed this responsibility you were O.K., but God help you if you didn't. Once I reproached him for not having been on my ranger district for two years. His reply was that he considered that I had been doing a good job other wise he would have been around. One night we were sitting around a campfire and his conscience probably bothered him as he told me that I had been offered charge of the Savenac Nursery the year before but that he had turned it down as he did't think I would want it. He said that when a ranger was doing a good job that he should not be moved, and I don't believe he ever recommended a man for promotion or transfer unless he felt that he would lose him anyway. Three times when I worked under him I got a promotion only when I expected to resign. However, I never enjoyed working under a man as much as I did for Elers. Only on two occasions did he seem critical of my efforts:

When I took over the Superior and Iron Mountain Ranger Districts in 1914, a pretty bad fire year, a fire occurred on Seigel Creek. Koch sent me to suppress this fire. It was across a corner of the Ninemile District over on the St. Regis District. We could only get within 4-hours hike of the fire with a packstring so it was necessary to spend 8 or 9 hours a day in travel. The crew was played out and all but 3 men were quitting. I told them if they would stay until we got a line around the fire I would give them travel time out. This they did but the fire was largely in slide rock, a severe fire day came on and the fire blew out of a snag over the line and we lost it after almost superhuman effort to hold it. We then built a trail to the fire with a new crew. I don't think Elers ever quite forgave me for letting this fire get away. He felt that I should have somehow held the first crew.

That same year a fire broke out on Landowner Mountain while we were fighting the Seigel Creek fire and spread to about 200 acres before we got men on it. I went to this fire with 10 men. We hiked in from Superior and carried the tools. Three head of horses packed all the other supplies, provisions and camp equipment. The fire was controlled with this 10-man crew, and 2 men were left to mop it up at the end of a week. No more grub or supplies were needed. The success of this venture probably means that the Trout Creek drainage was saved from being burned out as 1914 was a bad fire year. The Diamond Match Company is now logging the timber that might have burned.

An incident occurred in connection with this fire that is worthy of note. The crew, to a man, was outstanding. As much as a quarter of a mile of the fire boundary was given to individual men to control, and as I recollect there was no lost line although bad burning conditions existed. When we got back to Superior I could not satisfy myself to let this crew go, so made a deal with them to stick around and I would feed them and they would get paid only while on a fire. This went on for a week or more while several small fires up and down the valley were put out. One day Koch came out and seeing that this crew seemed to be under my supervision wanted to know "how come." When I explained the arrangement he was pretty angry and made me lay them off. Three days later a fire broke out that required 200 men to control. I always felt this would not have been necessary had my trusty standby crew been available. I believe this to be the first crew employed under similar circumstances.

The year 1914 was a historic year for the Lolo Forest as lookout stations were first established then. The only equipment was a map mounted on what is known as a Koch board, as he designed it. Dave Olson, later Chief of Planting in Region 1, was the first lookout man on Illinois Peak. An incident of interest that year was the checking of lookouts by setting test fires. F. A. Silcox and R. Y. Stuart, I believe, set such a fire on Eddy Creek, a distance of over 20 miles from Illinois Peak. When they returned to Missoula they wanted to know if this fire was sighted and if not, why. As I had a horse patrolman in that locality I checked with him at the first opportunity. He informed me that he had ridden up Eddy Creek on the morning the fire was set and saw 2 men engaged in watching the fire but as they had a good trench around it he decided they knew their business and rode on. The fire, he said, was making a lot of smoke but lay close to the ground and did not rise above the tree tops. I reported this fact to the supervisor but heard nothing more about it.

Another time that Elers Koch was provoked with me was when he and Jim Girard planned a trip to look over the timber on Upper Trout Creek. At that time, I had the supervision of 20 bands of sheep ranging in Clearwater, St. Joe and Lolo areas and got so tangled up with routing these sheep out from the embarkation point that I could not go with Jim and Elers. I did meet them at the train with saddlehorses and pack outfit and directed them out of town. However, they had bad luck and dumped the pack horse in Trout Creek and lost so much time that they had to camp as a place known as the Pump, not a very good camp spot. Jim went after water and fell off an old flume throwing his shoulder out of joint. Elers came into town next morning on the dead run on my saddle horse. The horse was a dark bay but he looked like a gray from sweat and foam. We got the local doctor and a bottle of whiskey and started up Trout Creek. After we left an old man took my horse out and walked him around until he cooled off, and probably saved me a good horse. When we got to the Pump, the doctor threw Jim's shoulder back in joint and we handed him the whiskey. He took a good swing, put the bottle in his pocket and started off down the trail. Some years afterward Jim walked up to Mrs. Phillips at a dance and said, "Are you Mrs. Roy Phillips? Well, I am old Jim Girard. Roy saved my life with a bottle of whiskey one time."

I worked with Jim on several occasions and learned quite a bit about timber.

The last time I worked with him we cruised 20 million feet of timber in Ninemile in two days. The timber was sold to the A.C.M. Company and cut out remarkably close to the estimate, I was told.

Probably more humorous stories could be-told about Glen Smith than any other man who ever worked in Region 1. When I went to the Nezperce as supervisor in 1928, there was a rush of grazing complaint cases in the making. I told Glen that I thought most of the trouble was due to the permittees going over the ranger's head with their grievances. I suggested that we let the ranger sit pretty much as a judge, present each case, and give the decision that he thought was just and proper. The ranger was briefed in advance of the conference. I can see Ranger O.V. Clover yet as he sweated it out in each case. We, of course, supported his decision which in each instance was the proper one. After that I do not recollect that Clover let very much get past him.

We had a lot of trouble with a sheepman by the name of Cleveland, and Glen and I went over to Snake River to adjudicate the case. He refused to handle his sheep so as to prevent damage to the range. In spite of the fact that he had previously been cut from three bands to two he still persisted in poor handling of the stock. We sat in the 100 degree shade at Pittsburg Landing, and argued all day. Every time we had about reached an agreement he would blow up and a fresh start would be made. Finally, we had to stay over night, and he put us upstairs on a bed with no mattress and one thin cotton blanket. Next morning Glen had the print of coil spring all over his back and I suppose I did, too. (Glen then told me about a trip he had made on the Custer with J. C. Whitham when they had spent all day lifting the front end of Whitham's Ford out of the road ruts and he had the word FORD burned on his back at the end of the day.) After futile argument most of the day, we pulled out, apparently defeated in reaching any agreement. However, within the next few weeks Cleveland sold out, so our troubles were ended. I suppose he was as much discouraged as we were.

Perhaps to those who went through the 1910 fire season that experience is the highlight of their Forest Service experience. It was so to me, and I had had very little training and experience along that line, other than that I had handled small crews of men since I was 15 years old. When I went in to see Elers Koch about a job, he blinked a few times and said I could have a job at $75 a month if I would provide two horses and equipment. I would, of course, have to subsist myself. I went to work on a timber survey crew April 4, and about June 1 at the Savenac Nursery. I helped put in the first seedbed there. We also did some experimental planting with corn planters and in seed spots.

After June 15 the fire situation became critical and Haun sent me to a flag-stop called Borax on the Coeur d'Alene branch of the Northern Pacific Railroad for fire patrol duty. The job consisted of patrolling the territory from Saltese to the Montana-Idaho state line and particularly the Northern Pacific and Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroads. As coal was the fuel used by all locomotives and the rights-of-way were highly inflammable, the job was not an easy one. I had no previous training whatever in fighting forest fires and only instructions from Ranger Haun to put out any fires that might occur on my district. Also, none of the railroad section crews, of which there were three on my district, had fire training; so, as fires occurred, I proceeded to train them on the job. About the only directive given me by Haun was that results were all that he was after, and that the guard the previous year had not gotten them so he had had to fire him.

Many and varied were the experiences of that 1910 season, performed at first on foot and later on a railroad speeder. The crucial test perhaps came on the first fire, a 10-acre blaze near Drexel on the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad on a hot June afternoon. Seeing it was beyond one-man stage I went to the nearest section gang and got them into action. These men were Bulgarians under an elderly Irish foreman. The crew was recently from the old country and could speak very little if any English. The foreman turned the crew over to me and immediately found a spot in the shade. Two big black fellows, the cream of the crew, had selected the names of George Washington and Abraham Lincoln. I gave Abe my axe, informed him that he was the crew boss and that the job was to trench the fire. He sure "poured it on" to the other Bulgarians. We got in front of the fire and tried to stop the forward run, which was bad tactics as it repeatedly jumped over our heads, when we would back up and make a fresh start.

At sundown we were still frantically battling the fire, which had not gained appreciably in size but had caused a lot of sweat and blisters. About that time Ranger Haun appeared on the scene, having seen the smoke from down the river. When he observed how worn out we were, he suspended operations for the day, took me back to Saltese with him and the next morning detailed Ranger Jack Breen to assist me. With the Bulgarians again on the job we quickly got the fire corralled and Breen gave me some valuable pointers in fire fighting.

This section gang, as well as the others, became efficient fire fighting units, as circumstances required that I train them since I could not hope to do the job alone. One of the crews, however, persisted in burning tie piles and caused me considerable trouble. One day one of these fires occurred just west of Saltese on the edge of town. Thinking to give old Tom a lesson, I trenched the upstream spread of the fire and left the town end untended. As there was a slough on one side and the railroad track on the other, there seemed only a remote possibility of the fire spreading except in the one direction. This it did, and by late afternoon had spread into the limits of Saltese and burned one building. This made a "good Indian" of Tom Hanlon and years afterward, when he had a section on my old ranger district, he would go long distances from the railroad to put out lightning fires and never charged the Forest Service one red cent for his services.

Some 30 fires along the two railroads were suppressed during the summer and none of these fires exceeded 10 acres in size. Many and varied were the experiences in that connection but success was dictated entirely by force of circumstances. When I left my cabin there was no certainty that I would return that night or perhaps for several days. Hoboes cleaned me out of most of my worldly possessions so I boarded up the windows and put a sign on the door, "Look out for the gun." This was a bluff but it worked. When lumberman John Baird and Ranger Charles Vealey later came into camp enroute with a fire crew for the Bullion fire on the Coeur d'Alene Forest, they got a long pole and shoved the door open after unlocking the Forest Service padlock.

A lightning fire occurred on Denna Mora Creek and Guard L. H. Foote was given charge. It burned an area of about 40 acres and Harvey Polleys, of the Polleys Lumber Company of Missoula, was killed on that fire by a falling snag. I reached the fire at about the time this happened and assisted in removing the body. At that time Polleys had started operation on Randolph Creek and had purchased the timber in the upper St. Regis drainage. This was the timber we had cruised that spring in six feet of snow.

As Elers Koch has written up my experience in connection with the big blow of August 1920 and 1921 there is no need to recount that here. I consider this experience as a red-letter event in my Forest Service career, and with a sincere feeling of humility have been a little proud of the fact that I was able to stand the acid test at a time when close to 100 lives had to depend on what I might decide. While I have had many close shaves on the fireline and have had occasion at times to deal with panicked men, I am glad to say that I never lost a man, as the result of my decisions, and have always kept foremost in mind the need for safety on the fireline.

The year 1910 was pretty much a one-man show and that will be as I will always remember it. Foresters as a class had very little if any training as firefighters. Trails were few and those that did exist had been blazed out by trappers, prospectors, miners, and others having some interest or investment in forested areas. Discovering of fires was the result of patrols, often seen only after fires had burned several days and columns of smoke had drifted high into the sky. Patrolmen tried to make some high point immediately after lightning storms but this often meant fighting dense brush up a steep mountain for hours at a time. Often when men reached a fire they were too worn out to fight it and had no food supplies or effective tools to work with.

Ranger Bill McCormick told of going to a fire on the old Blackfeet Forest. The whole mountainside was ablaze. There was an old ranger with long gray whiskers on the fire. He didn't seem to be very much concerned with anything at all so Bill finally said, "What are we going to do?" The old man answered, "We, h—l, this is my fire; go find one of your own."

George Ring, Supervisor of the Nezperce, was on a large fire all alone. When a board of review asked George what he did to get this fire under control, he answered, "Nothing, I went looking for a fire my size."

George was truly one of the pioneer rangers. He first worked in 1897, under the old political appointment system. His supervisor ran a saloon in Grangeville. It was his daily custom to go out on the porch of the saloon, where he could see the mountain back of Grangeville, and then go back into the saloon and write in his diary, "Viewed the forest today." All the rangers had ranches or other occupations and spent very little time out on the forest.

George said that his first summer was spent in a camp where he thought the forest should be, but when the boundary was surveyed he found that he ate on the forest and slept off of it, as the boundary line established a year later ran right through the camp. George worked at the job and familiarized himself with the forest. He was the only man on the forest who survived an inspection by a Washington Office inspector. When I went to the Nezperce in 1928, I found old boundary notices posted by George Ring in 1908. In all the early day photographs George is characterized by a derby hat and a big chaw of tobacco that bulged out a cheek.

Following 1910, I look at all accomplishment as pretty much a matter of teamwork and the inspirational ability of men in getting the most out of others was for many years the criterion of ability to advance in the Service. Men who were individual workers or who would not cooperate as members of a team just didn't get anywhere. It was surely and simply the survival of the fittest, and there was no such thing as trying to find a place for the square pegs that happened to be in round holes.

Through the years, there are some accomplishments for which I feel I can claim individual credit: An all-time record in the cost of planting trees and in the development of the present Region 1 planting tool. I did not invent the tool, but did take it on after it had been turned down by tree planters elsewhere, and perfected the design and planting techniques in the use of the tool.

Likewise, after D. L. Beatty had given up in despair over getting his trail grader in use as trail construction equipment, I demonstrated that it could be used to advantage on practically all trail construction projects at a great saving in trail construction costs in comparison with hand labor.

I organized the first fire overhead unit in 1920, and successfully demonstrated the efficiency of this unit in manning large fires.

I also organized and successfully used plow units on large fires, and in 1931, established a record of 30 miles of firelines constructed and held by plow crews.

I designed and equipped the first Region 1 tractor with bumper for clearing road right-of-way. With this equipment we constructed the motorway from the Red River Ranger Station to Green Mountain Lookout at a cost of $512 per mile, which is believed to be a record for road construction cost.

In 1934, with ERA and NIRA crews and one CC camp, constructed 200 miles of forest protection roads. This was accomplished in the face of a bad fire year, and we detailed many men to the Selway Forest which had tremendous fire losses. Although these fires burned next door, as it was, Nezperce losses were small. As I recollect, the largest fire was about 200 acres.

There are many other accomplishments that I sponsored and carried out, but the foregoing were examples of projects that were initiated where the most opposition was encountered in developing and putting across to a successful conclusion. For that reason perhaps they register most forcibly as something to be proud of.

All through the years it has been apparent to me that to meet any material measure of success a man must have the cooperation and support of the men under him. I started to hold down a man's job at 13 years of age and by the time I reached 15 I was made a boss over other men. It requires considerable tact and pretty sound judgment to issue orders to men old enough to be your father, and men must, above all, have confidence in you to carry out orders and do the job well. Teamwork and competitive spirit go hand in hand, and this I have tried to instill in the various organizations with which I have worked.

Furthermore, I have tried always to give a full measure of credit to the individual, even though it was necessary for me to set up the play and back it up to the finish. When a chance for promotion came to a man I have always supported it if worthy, and have never withheld support because he was in a key position and hard to replace. Always I have insisted on men assuming much responsibility and tried to train them in the essential qualifications of the next step up the ladder. And I have never recommended transfer or promotion for people merely to get rid of them. Loyalty to the organization and a keen sense of stewardship for the resources with which entrusted has been the goal for which to strive. Perhaps the tendency to be outspoken may at times have spoiled the chances for advancement in the organization, but it has been my experience that constructive criticism is good for the soul, and the individual as well, and I encouraged the people in my charge to criticize if it proved to be of a constructive nature.

My 41 years of service are full of pleasant memories, and the only regret perhaps is that, at the zenith of ability and knowledge, I should be put on the shelf. The only redeeming feature is that it gives the younger men in the organization a chance to step up. However, the top men do not always follow the rule of voluntary retirement. Often those who seek to stay on are the least essential, and the man who does not train someone to take over the responsibilities of his job at any time is not a good organizer. After all, those who demonstrate the quality of leadership which sparks an organization, and by precept and example blaze the way for the followers, are the ones who gain the greatest accomplishment and the utmost in public respect and appreciation.

You have asked me not to be overly modest in recording personal experiences, and I have tried not to be so. However, this is the first time I have brought much of this together in any sort of chronological order and the fact that I am now retired eliminates the chance of any repercussions as they may affect anyone. You are entirely welcome to use any of this that may seem appropriate.

Throughout my career I have endeavored to be a loyal and conscientious member of the organization, and while I may have had differences of opinion and even heated arguments with the boss, I have always fallen in line and tried to do a good job of following out orders when they were given as a definite commitment as opposed to my personal views.

Finally, it would be amiss if I did not in some measure pay tribute to the many fine men and women with whom it has been my privilege to associate down through the years, and I realize fully that the destiny of the Forest Service is in good hands; also, that I will have no occasion to regret that I was once a part of this truly fine outfit.

|

|

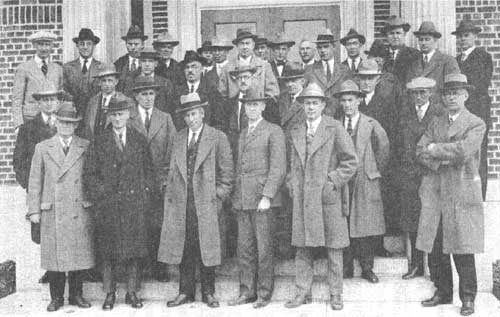

Forest Supervisors Meeting, Missoula, Montana, March 1925. Back row, from left to right: W. M. Nagel, M. F. Wolff, C. D. Simpson, K. Wolfe, R. T. Ferguson, Theodore Shoemaker, John W. Lowell, R. A. Phillips, Paul Redington, Lloyd Hornby, Dr. Carl Schenck, F. J. Jefferson, C. K. McHarg, W. J. Derrick, Glen A. Smith, J. C. Whitham, J. E. Ryan. Middle row, from left to right: John Somers, John B. Taylor, Paul Al Wohien, E. H. Myrick, A. H. Abbott, Elers Koch, G. E. Martin, Alva Simpson. Front row, from left to right: W. B. Willey, Arthur H. Baum, Burr Clark, W. W. White, Ernest T. Wolf, Howard Flint, Fred Morrell. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/early_days/2/sec7.htm Last Updated: 15-Oct-2010 |