|

Trails of the Past: Historical Overview of the Flathead National Forest, Montana, 1800-1960 |

|

THE FUR TRADE

Introduction

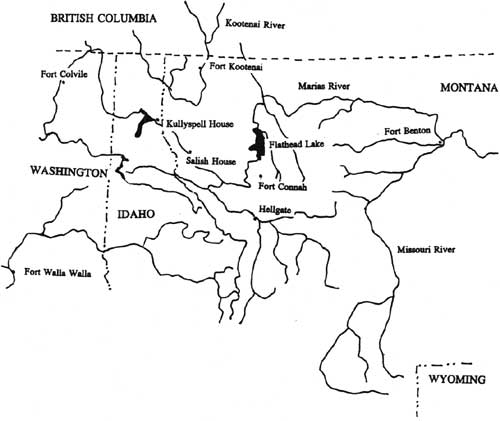

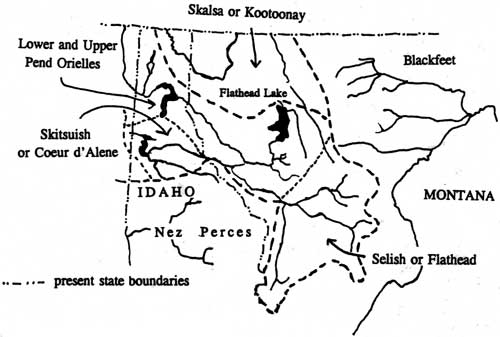

Northwestern Montana was one of the last regions of the lower 48 states to be settled by Euroamericans. A fashion in gentlemen's hats made of beaver skins led Europeans to the northwestern reaches of the continent, including the area now known as Montana. Fur traders entered the northern Rockies wilderness to make profits for capitalist companies chartered by the governments of western Europe. Along the western slope of the northern Rockies, British companies were the dominant force in exploiting the fur-bearing resources. By the 1830s, however, due to the whims of fashion in Europe and to the depletion of the beaver, the fur trade was declining. Settlers had not yet entered the Inland Empire in any considerable numbers. Despite the decline, in 1847 the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) founded a trading post in the Mission Valley called Fort Connah. They also operated a seasonal post in the Tobacco Plains area for about 15 years, and possibly one near the head of Flathead Lake for a short time (see Figure 2). Kootenai and other Native Americans traded furs and buffalo products at these posts (see Figure 3). While they were active in the area, the fur traders discouraged Euroamerican settlement in western Montana.

|

| Figure 2. Approximate locations of fur trading posts in northwestern Montana and vicinity. |

|

| Figure 3. Approximate geographic locations of Native American tribes in northwestern Montana and vicinity ca. 1853, based on a map prepared under the direction of Governor Isaac I. Stevens (from Fahey 1974:52). |

Physical remains of the fur trade era are difficult to verify on the Flathead National Forest. To the south, in the Mission Valley, the site of Fort Connah is well documented, and sites of other trading posts have been tentatively identified, such as Fort Kootenai near Eureka.

The Fur Trade

In the early 1800s, President Thomas Jefferson sent two American explorers, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, on a cross-country journey west to the Pacific Ocean. The Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-1806 did not pass through the Flathead Valley, but their trip influenced its later development. The journey of these men and their companions helped ensure American control of the entire area by strengthening U. S. claims to the Pacific Northwest and by establishing relations with many powerful Indian tribes. It also ended speculation about a possible Northwest Passage. Attention soon turned to the abundant natural resources in the area traversed and described by Lewis and Clark. Entrepreneurs and adventurers alike were attracted to this newly "discovered" region (Baker et al. 1993:18, 22).

The hostility of the Blackfeet and others on the plains east of the Rocky Mountains led to a relatively slow exploration of northwestern Montana by the large fur companies and independent trappers. Seeking a safer route, the Canadian-based fur companies reached Oregon Territory by crossing the mountains north of the border and traveling up the Columbia and Kootenai Rivers from Canada, avoiding the hostile Blackfeet. As a result, the fur trade first entered the western slopes of the northern Rockies from British territory in the north (Athearn 1960:32; Sheire 1970:66, 68-69).

Two British companies, the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) and the North West Company, had been competing for the fur trade east of the Rockies since about 1784. Each had continually expanded westward across what is now Canada. The latter company reached the Rocky Mountains by 1799 (Biggar 1950:39; Schaeffer 1966:1).

In 1807 Manuel Lisa built the first fur post in what is now Montana, at the junction of the Yellowstone and Big Horn Rivers, for the Missouri Fur Company. The first American post west of the Rockies was established two years later on the north fork of the Snake River but was abandoned soon after. American fur traders on the Missouri River did not penetrate the northern Rockies, however (Toole 1959:43-45).

In the 1800s these large fur companies obtained furs by several methods. One method was trading overseas goods for furs with Native Americans. Another was employing hunters and trappers who worked for fixed wages. The third was to trade for furs from free hunters and trappers at trading posts, rendezvous, or in St. Louis. "Free hunters" and "free trappers" worked as private individuals, generally dealing only in the finer kinds of fur.

It did not take the British fur traders long to discover the resources of the upper Columbia River drainage, which includes present-day northwestern Montana. Two French-Canadian traders working for the North West company were reportedly the first to cross the Rocky Mountains into the western interior. They spent the winter of 1800-1801 with a number of Kootenai, probably in the Tobacco Plains area (Schaeffer 1966:1, 9). According to fur trade historian Hiram Chittenden, the upper Columbia River was a profitable region for the North West Company and the HBC. The Flathead Lake area, he commented, had "hundreds of the finest streams in the mountains. It was the home of those staunch friends of the whites, the Flathead Indians, and was a favorite haunt of the hunter and trapper" (Chittenden 1954:787).

The North West Company was managed by a group of Scottish men who employed French traders. The company hired Welsh geographer David Thompson to explore the country in the vicinity of the 49th parallel (now the international boundary) and to identify suitable locations for the company's trading posts. Thompson traveled up the Kootenai River into Montana several times between 1808 and 1812, establishing his first trading post in the vicinity of present-day Libby, Montana. In 1811, he returned to the Columbia River headwaters to recruit a few "free hunters" who were already operating in the Rockies. Most were Iroquois, but some were of mixed French-Canadian and Native American descent or of European descent. Iroquois traders were in the region by 1800 or so; they may have been the first traders to anger the Blackfeet by taking arms across the Rockies into Flathead-Kootenai country. Some of Thompson's men remained in the area that later became Montana. Jocko Finlay, for example, later traded in the Mission Valley (Chittenden 1954:89; Bergman 1962:12, 15; Rich 1959:239; O. Johnson 1969:49).

Although the Columbia River fur trade was dominated by the British companies, some Americans attempted to compete in the region. John Jacob Astor's men established a trading post at the mouth of the Columbia River in 1812, but the War of 1812 forced the sale of the fort to the rival North West Company. Astor's Pacific Fur Company also established competing trading posts in the interior near Spokane and among the Kootenai and Flatheads, but soon the North West Company bought out the Pacific Fur Company (M. C. White 1950:149-150; Historical Research Associates 1977:4).

The rival fur companies watched each others' movements closely. In 1810 the HBC sent clerk Joseph Howse to report on David Thompson's movements (and the North West Company likewise sent a man to shadow Howse). The location of Howse House, built by Howse and occupied 1810-1811, has not been confirmed. Some argue that it was located at the head of Flathead Lake, based on an 1814 map, but other evidence points elsewhere. The cabin (the first HBC post west of the Rockies) was probably built in the vicinity of Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho, on the Kootenai River near the later town of Jennings, or along the Clark Fork River in Montana. After Joseph Howse's trip into the area, the HBC abandoned the western slope of the Rockies to the North West Company (Biggar 1950:46; O. Johnson 1969:214 fn; Braunberger & White 1964:29; Campbell 1957: 182).

In 1812 David Thompson ascended the terminal moraine that dams Flathead Lake near Polson. After looking across the lake, which he called Saleesh Lake, he wrote, "all the ranges have many hollows, swellings - & Lawns more or less sloping." Thompson retired later that year to Montreal and never returned to the Pacific Northwest (Thompson 1985:25).

Although Thompson was the first Euroamerican of record to see Flathead Lake, it is likely that others had visited it before him. Finan McDonald spent the winter of 1808-09 on the Kootenai River above Kootenai Falls and the summer of 1810 on the Flathead River near the mouth of the Jocko. One of the earliest recorded trips into northwestern Montana was that of Finan McDonald, two French-Canadians, and 150 Flatheads. McDonald later became an important HBC fur trader in the lower Flathead Valley. In 1810 the large group crossed the Rockies at a "wide defile of easy passage" (probably Marias Pass) from the west and hunted buffalo on the plains. They were attacked by Piegans but held their position with firearms. The McDonald party would have traveled along Flathead Lake to reach the pass (M. C. White 1950:214; Buchholtz 1976a: 17, 19; Robinson 1960:8).

In 1821 the two rival companies in the area, the HBC and the North West Company, combined under the name of the former. This merger invigorated the fur trade in the Flathead area. Before the combination, the North West Company had had a highly organized transportation system from the mouth of the Columbia River but had not shown profits in proportion, and the HBC "had little to its credit west of the mountains" (Rich 1959:563).

American companies again moved into the Rocky Mountain west and challenged British interests by 1820. Only a few Americans came into the lower Flathead, however, and they were just traveling through. Most traveled along the Flathead-Jocko River trail. In 1828 the Missouri Fur Company, an American company, sent Joshua Pilcher and others to the lower Flathead. They probably wintered at Flathead Lake, but in the spring of 1829 they left the area because of unsuccessful trading; the British were too firmly entrenched in the area. In addition, by this time the fur trade in the Northwest was beginning to decline (Biggar 1950:53-54; M. C. White 1950:149-150; Buchholtz 1976a: 19).

Competition was further reduced in 1833 when the HBC and the American Fur Company each agreed to limit their areas of activity. In 1834 the Rocky Mountain Fur Company went out of business, but American adventurers continued to invade the lands west of the mountains and force more liberal treatment of both Native American and Euroamerican trappers (Lewis & Phillips 1923:46).

Between 1813 and 1823 the British companies practiced the brigade system of trapping, sending out groups of at least 50 men to trap entire areas. After the merger with the HBC in 1821, the new HBC discouraged American intrusion in the area by expanding the brigade system in the northern Rockies to create a buffer zone free of beavers. HBC company agent John Work led the "Flathead Brigade" during the 1820s and trapped much of the area west of the Divide in today's Montana, hoping to deplete the beaver resource and discourage Americans from entering the area (Biggar 1950:51; Baker et al. 1993:24-25; Buchholtz 1976a: 19).

The North West Company, on the other hand, used Native Americans rather than voyageurs to trap furs. The Native Americans of the area were considered to be "not vigorous fur hunters." The North West Company brought in some Iroquois to teach the local population how to hunt and trap (Burlingame 1957:I, 81; Chittenden 1954 I:xvi).

The HBC enjoyed a good trade relationship with the Flathead, Pend d'Oreille, and Kootenai. These tribes hunted buffalo regularly and received a fair trade for buffalo products. The latter half of October generally marked the opening of beaver trapping season (if taken in the summer, the pelt would be inferior). In the 1820s the trade with the Native Americans in Flathead and Kootenay country was mostly in guns, ammunition, kettles, knives, and tobacco. Other items traded included cloth, buttons, beads, vests, axes, flour, salt, pepper, coffee, tobacco, and liquor (Wright 1966:13; Partoll 1939:405; Alexander Ross' Flathead Journal, B.69/a/1, HBC; Robbin 1985:18).

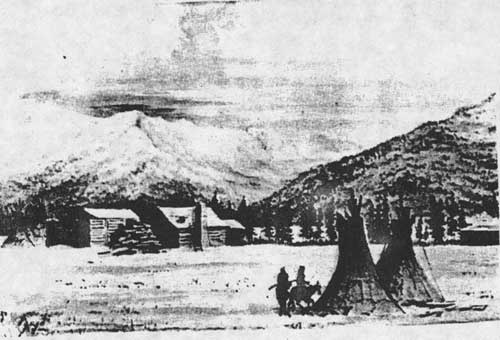

The HBC operated a trading post in the Mission Valley called Fort Connah from 1847 until 1871 (see Figure 4). The post replaced the Flathead Post near today's Thompson Falls; it was located farther east in order to counter competition with American fur traders. Like other trading posts, it was strategically placed at the junction of major travel routes where aboriginal territories overlapped. The British company opened the post on American territory the year after the 1846 treaty was signed defining the international boundary as the 49th parallel. It took many years, however, to arrange for the post to be closed and the HBC to be compensated for its property on American soil. For a number of years Fort Connah supplied the Colvile (Washington) district with certain products not easily obtained elsewhere, including dried buffalo meat, pemmican, buffalo fat, tallow, horse accessories, par-fleches, saddle blankets, dressed skins, and rawhide and buffalo hair cords. These items were important since they were necessary for travel on horseback and were not easily available elsewhere (Partoll 1939:402-404; Biggar 1950:57).

|

| Figure 4. Reproduction of Peter Peterson Tom's water color of Fort Connah on the Flathead Indian Reservation, 1865 (courtesy of Mansfield Library, University of Montana, Missoula). |

When Fort Connah was established in the lower Flathead, the population of the area was relatively low and was almost totally Native American. In 1846 a clerk at Fort Connah noted that the Euroamerican population in the region was about 15, and the Native Americans in the Flathead Confederacy included about 450 Flatheads, 600 Kalispels, and 350 Kootenais. Trade, however, was brisk. Duncan McDonald reported that Fort Connah annually purchased about 5,000 beaver pelts, plus other skins such as otter, badger, fisher, and buffalo products. In 1834 the beaver harvest from HBC domains totaled 57,393 pelts, of which about 21,000 came from the Columbia River system (Robbin 1985:17; McCurdy 1976:75; Lewis 1923:47).

Within a few years, Fort Connah faced competition and increased settlement of the area, both damaging to the fur trade. In fact, the HBC actively opposed settlement of the areas in which they traded. In 1850 John Owen established a trading post in the Bitterroot at the site of St. Mary's Mission (which had been closed largely due to Blackfeet hostility). Fort Connah became less secluded because of the Stevens railroad survey of 1853-1854 and the founding of St. Ignatius Mission about six miles south of the fort in 1854. The 1855 treaty with various tribes reduced the tribes' dependence on hunting and trapping. The building of the Mullan Road 40 miles to the south and the founding of Hellgate in 1860 and Frenchtown in 1862 also reduced Fort Connah's isolation. In the 1860s the discovery of gold in British Columbia brought miners through the lower Flathead Valley and revived trade, but only briefly. The HBC claims were settled in 1869, and Fort Connah closed its doors permanently in 1871 (Partoll 1939:403, 405-409, 412).

The HBC operated one other trading post in the area, about 90 miles north of Fort Connah. Fort Kootenai was only open seasonally, and it operated late in the fur trade period. The company traders operated in various places in Tobacco Plains just south of the Canadian boundary beginning in approximately 1846. The post was moved north of the line in 1860, where it served the Wild Horse miners in British Columbia until it closed in 1871. An HBC trader would come in from Fort Colvile in the fall, trade throughout the winter, and return to Colville (a 16-day journey with packs) in the spring. The post was quite isolated in the winters; during the winter of 1858-59 trader Scotty Linklater reported seeing only 3 parties of Euroamericans in the area. In 1859, about 300 Kootenai were reportedly living in the Tobacco Plains area, and about 700 elsewhere (Partoll 1939:405; Blakiston 1859:334; "Diary" 1940:329).

In 1859 Fort Kootenai trader Linklater transported to Fort Colvile the skins of 220 bear, 800 marten, 500 beaver, and 2,000 muskrats, plus moose, elk, and buffalo hides. The Kootenai, every spring and fall and sometimes in late winter as well, would cross the mountains to the plains to hunt buffalo. Some examples of the exchanges at Fort Kootenai are as follows: a three-point blanket for 3 bear skins or 12 marten skins, one charge of powder and ball for a muskrat skin, a file or knife for a beaver skin, and 40 charges of powder and ball for a buffalo skin. Linklater reported that the net profit for the trading at his post was about 90% ("Diary" 1940:328-329; Blakiston 1859:334).

Other short-lived HBC trading posts have been reported in the Flathead Valley. These include one located on the lower west side of the upper Flathead (operated in 1844 by Angus McDonald and later transferred to Fort Connah) and another at Red Meadow in the North Fork. In 1867 Laughlin McLaurin was reportedly running a trading post on Ashley Creek (near today's Kalispell) for the HBC (Flathead County Superintendent 1956:17; Schafer 1973:2; Shaw 1967:3). Although the fur traders tended to discourage settlement of western Montana by Euroamericans, they could not, in the end, prevent the exploration and gradual settlement of the area by miners, ranchers, and others.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/1/flathead/history/chap1.htm Last Updated: 18-Jan-2010 |