|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 2

The Alexander Archipelago And Tongass National Forests Through 1910

Take the Sierra Reserve and place it directly on the coast, sinking it down until the highest peaks are from three to four thousand feet above sea level. Let the Pacific break through the main divide in three or four big straits making as many islands out of the principal range. To seaward, at distances of from ten to fifty miles, sprinkle in innumerable islands of all sizes and drop a few also to the eastward. In place of rivers, creeks and canyons let the reserve be cut in to on all sides by countless deep water ways with soundings of from ten to one hundred fathoms, the shores rising abruptly. Throw in many small streams with precipitous falls and cascades. Then strip off the whole surface down to bedrock and boulders. In spots put on a thin layer of muddy soil and cover the whole with moss. Over all except the highest elevations plant a dense forest of spruce, hemlock and cedar, leaving some of the flat places as swamp or "muskeag" dotted with a scrubby growth of pine. Throughout this forest, cover the ground with an exceedingly dense and often almost impenetrable undergrowth of all kinds of brush (chiefly devilsclub) and let the ground be as rough as possible. Spread patches of brush, grass and meadow on the higher tops and let the bare rock stick out occasionally. On this area of over 5,000,000 acres imagine a population of only 1,500 Indians and about 500 whites, industries represented by a dozen small copper mines, as many salmon canneries and half a dozen little sawmills. Then consider that, practically speaking, there are no roads or trails and that travel by land is out of the question. Remember that communication is by water only and very uncertain at the best. Picture three or four work horses, a couple of cows and one mule in the whole region. To the climate of the Sierras add perpetual rain in the summer and rain and snow in the winter and the characteristics of the southeastern Alaskan forest may be partly understood. To be thoroughly understood, they must be felt.

—F.E. Olmsted Inspection Report, 1906

The National Conservation Movement,

1891-1909

The years from 1891 to 1897 were an interim period for the forestry movement in United States. Presidents Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland set aside as forest reserves 17.5 million acres of land, largely at the request of local interests. These areas were reserved from use, however, rather than for use; their creation of the reservations not only withdrew them from sale and entry but from any type of use. A number of bills were introduced in Congress between 1891 and 1896 for administration of the reserves, but all failed to pass for one reason or another. Meanwhile, the presence of large reserved areas, and the failure of Congress to provide legislation for their production or management, stirred up vigorous protest among those who normally used them. These included four groups: stockmen, primarily sheep grazers, who used the mountain meadows of the Cascades and the Sierra Nevada for summer range; settlers, who desired to establish farms in mountain valleys and wanted a supply of firewood; lumbermen, who claimed that too much of the timbered area was in government hands; and politicians, who sought a popular issue. [1]

In order to reach a solution to the problem, Secretary of the Interior Hake Smith was persuaded by Gifford Pinchot and others to request that the National Academy of Sciences make an investigation in the field and recommend specific legislation. [2] A committee of eminent scientists was appointed, $25,000 was appropriated to defray their expenses, and the committee made an extensive western trip in the summer of 1896. [3] Pinchot and some other members of the committee favored both submission of a plan for management of the reserves and recommendations that new reserves be created; but a majority of the commission recommended creation of the new reserves immediately, prior to perfecting a scheme of administration. Cleveland heeded the latter's recommendations and created thirteen new reserves with an area of 21 million acres—without a management plan.

Creation of the new reserves stirred up a storm of protest and precipitated congressional action. Congress passed the Forest Reserve Act of June 4, 1897, which stated the purposes of forest reserves and provided for their administration. (Often known as the Organic Act, it was actually an amendment to the Sundry Civil Appropriations Act.) Its major feature authorized the Secretary of the Interior to protect the forest reserves against fire and depredations and to "make such rules and regulations and establish such service as will insure the objects of such reservations, namely to regulate their occupancy and preserve the forests thereon from destruction." [4]

Within a month the Department of the Interior issued rules and regulations for administration of the forest reserves. A forest supervisor was placed in charge of each reserve, and fieldwork was handled by forest rangers. The reserves were divided into eleven districts, each under a superintendent who reported to the General Land Office in Washington. There were one or two roving inspectors. The system was not a success, since the superintendents and rangers were political appointees, not foresters, and the General Land Office was ridden with corruption. Therefore, in 1901, a forestry agency, Division "R," was set up in the department under a trained forester, Filibert Roth. [5]

Meanwhile, Bernhard Fernow resigned in 1898 as head of the Division of Forestry, in the Department of Agriculture, and was succeeded by Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot had been educated in forestry abroad, in France and Germany, and had become a consulting forester on the Vanderbilt estates in North Carolina and New York. He was independently wealthy and had access to men of influence and power. His own idealism captivated the imaginations of young men seeking careers of public service, and he became so adept at learning the wilderness skills that many westerners accepted him as one of their own. Above all, he was a personal friend of Theodore Roosevelt, who would become vice-president in 1900 and president the following year. [6]

Roosevelt's interest in resources and conservation stemmed originally from his hobby as a naturalist and his delight in hunting. In 1887 he organized the Boone and Crockett Club, which played an important role in wildlife conservation. Influenced by Pinchot, Frederick H. Newell, and W J McGee, this interest was extended into other areas—notably into forestry and reclamation. In addition, his own experience in life played a part. He had been a rancher in the Badlands of North Dakota during the 1880s and had developed a firsthand acquaintance with the problems of the West. His own political career as a reformer and his belief that the president should be a steward of the people led him to bring leadership to the conservation movement. Through executive action, seeking appropriate legislation, and personal leadership, he was able both to lead and direct the first conservation movement.

Once in office, Roosevelt created new national forests and national parks, implemented the Antiquities Act of 1906 to preserve areas of significant historic value, established wildlife refuges, progressed toward a satisfactory water policy, modernized old departments and agencies, and created new commissions. He did so in the face of opposition from both political parties, but he was aided by some support in Congress, by capable administrators, and by general support from the people. [7]

The story of the Pinchot-Roosevelt forestry and conservation movement is a familiar one and need not be repeated here. Nevertheless, some aspects of it related to the development of resource management in Alaska and hence require mention. These include, first, Pinchot's administrative philosophy and techniques; second, his relationships with other agencies; and third, the general climate of opinion in which the conservation movement worked.

The years from Roosevelt's accession to the presidency in 1901 until 1905 were marked by the evolution of the Division of Forestry to the Bureau of Forestry to the Forest Service. During this period jurisdiction over the forest reserves was divided. The commissioner of the General Land Office had general control over the public domain, but Division "R," under Filibert Roth, exercised actual control over the forest reserves. In the Department of Agriculture, the Division of Forestry (from 1901 to 1905, the Bureau of Forestry) provided technical advice on the forests. There developed a symbiotic relationship between the Division of Forestry and Division "R." Some men, including Edward T. Allen and Harold D. Langille, held dual appointments in both bureaus. The General Land Office, on the other hand, had the duty of disposing of the public domain. The position of commissioner of this office was a political one, usually given to a man from a public land state. The registers and receivers of the local land offices were also political appointees, and the field men were not all of high caliber. There was often friction between the resource-managing agencies and the Land Office. This friction was a constant theme in the resource history of western states, and nowhere was the friction greater than in Alaska. [8]

|

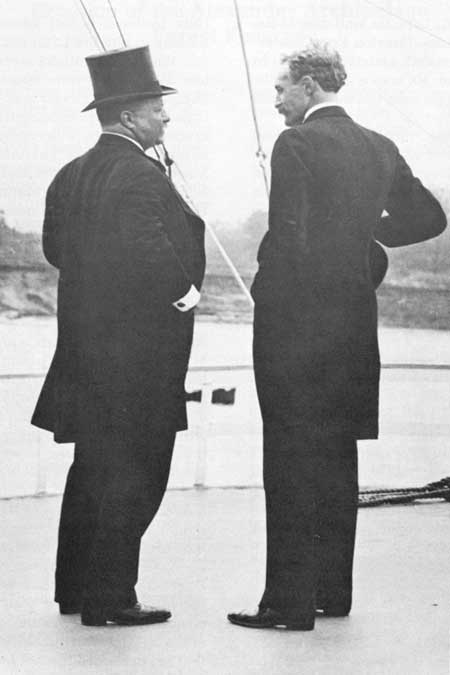

| President Theodore Roosevelt and Forester Gifford Pinchot, here photographed in 1907, collaborated to establish a vast national forest system and to bring it under management, but not without political controversy. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Pinchot desired transfer of the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture, a goal achieved in 1905. Another act a month later designated the Bureau of Forestry as the Forest Service. Two years later, the term forest reserves was changed to national forests. In 1908 an important administrative change was made, decentralizing the administration of the national forests so that all but the most important decisions could be made on the regional level. The national forests of Washington, Oregon, and Alaska, for example, were made part of District 6, with Edward T. Allen as district forester. Allen was the son of a Yale professor who became tired of the academic life and homesteaded in the wilderness of the upper Nisqually River in Washington. Young Allen became a reporter for the Tacoma Globe. Pinchot met Allen on his 1896 trip west and interested him in forestry. Allen served with both the Department of the Interior and the Department of Agriculture forestry bureaus and became the first state forester in California. A unique combination of public relations man, philosopher, writer, and forester, he was an able administrator. [9]

Several features of Pinchot's administrative ability should be mentioned. He was fortunate in his close relationship with Theodore Roosevelt, who gave him the strong political backing he needed against a conservative Congress and powerful and hostile pressure groups. Pinchot was a good judge of men, and much of his success came from his skill in picking the right men for the right jobs. This related to the field officers, such as E. T. Allen and William A. Langille, and also to the men in the Washington Office—Overton Price, his associate forester, and F. E. Olmsted, assistant forester in charge of general inspection. He was a good administrator in that he gave his field men full authority and backed up their decisions. [10]

The field men working for Pinchot were composed of two different groups. One was the "easterners," trained foresters who had received their education from forestry schools abroad or the American schools at Yale, Biltmore, Cornell, or Michigan. They were technically competent but knew little of the West. The others were "westerners" who knew the country and the environment in which they worked but had little "book learning" in the relatively new profession of forestry. They were practical men, concerned with making forestry work, and impatient of theory when it did not coincide with facts.

At first there was some friction between the westerners and the easterners. Thornton T. Munger, who went west from Massachusetts, resented the fact that trained foresters often found themselves working for men who knew less about forestry. E. T. Allen regarded his first task as getting the college men into the woods "to rub the Harvard off them." Melvin Merritt found himself regarded with suspicion by a supervisor whose education had come from the "University of Hard Knocks." Seth Bullock quit as supervisor of the Black Hills National Forest when a young forester began quoting to him the Latin names for pine beetles.

|

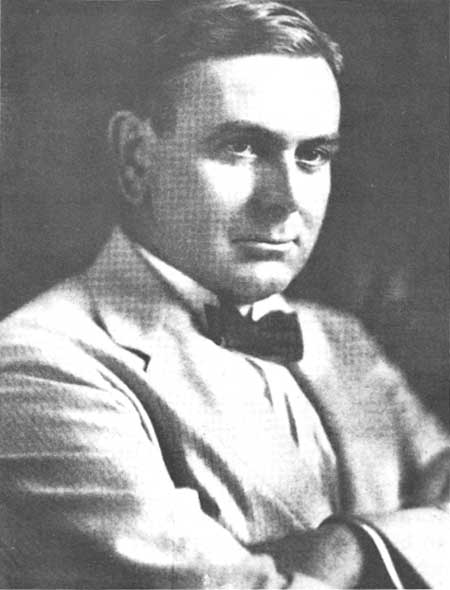

| Edward Tyson Allen was made district forester for the Pacific Northwest and Alaska in 1908. Pinchot's policy of decentralization gave much authority to Allen, who was determined to put college men into the woods, "to rub the Harvard off them." |

Pinchot and others were well aware of this problem. Westerners were necessary to the program, particularly at the ranger and supervisor levels. Americans have always been distrustful of "carpetbag" government, and the westerners were necessary to make national programs palatable to local communities. Meetings of supervisors and rangers, intensive inspection work, directives relating to interpretation of the Use Book, and establishment of ranger schools at state colleges—all of these helped the westerners gain the technical skills needed for forestry. At the same time, the easterners, with residence in the West, learned local folkways and practical skills and became accepted by the local communities. [11]

Pinchot adopted a program of cooperative federalism in his relationships with other agencies and units of governments. Some examples may be cited. The Geological Survey, between 1898 and 1904, surveyed and mapped the reserves, preparing the results in a series of illustrated volumes. The Forest Service cooperated with the Biological Survey in studies of animal distribution and with states in enforcement of game laws. Cooperative agreements were made with state universities and land-grant colleges for ranger schools where men could learn forest skills during the off-season. The Indian Bureau made cooperative arrangements with the Forest Service to manage forests on Indian reservations. An abrupt change came in 1910 with the appointment of Richard Achilles Ballinger as the secretary of the interior. Ballinger insisted on a strict "chain-of-command" administration, and his abrogation of several such agreements were links in a chain of events that led to Gifford Pinchot leaving government service. [12]

The forestry and conservation program of the federal government was controversial, and the attitudes of Oregon and Washington are of significance as they applied to Alaska. Oregon, under the Roosevelt-Pinchot conservation program, became a model of cooperative federalism. Its major use problem, that of grazing rights on the national forests, was settled early. Publicity surrounding the Oregon land frauds of 1904-1908 made Oregonians decide to do better. The leading recreational group, the Mazamas, worked closely with the Forest Service. A number of prominent public servants came to office and made Oregon a showplace of conservation activity. Washington presented a different picture. Although many lumbermen cooperated with the Forest Service against the common enemy, fire, the Puget Sound area provided the Forest Service with its bitterest critics. Julius Hanford, Wesley Jones, J. J. Donovan, Richard Ballinger, and many others expressed the frontier "grab-and-get" philosophy. Their interests often extended to Alaska, which they regarded as an economic dependency of Washington. [13]

Creation of the Alexander

Archipelago Forest Reserve

In Alaska, the period from 1891 to 1902 was marked by slow growth in the lumber industry, due primarily to increased mining activity. Handlogging was the rule; as late as 1902 there were only three steam donkeys in all of southeastern Alaska. On the Afognak Forest and Fish Culture Reserve, the Fish Commission put up a hatchery in 1907 and a few buildings made of planks whipsawed from knotty spruce trees. [14]

Knowledge of and interest in Alaska also increased during this period. As early as the 1880s, scenic tours of the Inland Passage were promoted, and ships began to carry tourists as well as freight and prospectors. Propagandists like Sheldon Jackson, Hall Young, and John Muir wrote of Alaska's scenic beauties, and a host of lesser talents wrote of the area for newspapers and magazines. A standard Alaskan tour developed. Ships put out of West Coast ports—Portland, Tacoma, Seattle, or Port Townsend—stopped at Victoria and Nanaimo, British Columbia, and then included in their Alaskan itinerary Wrangell, Juneau, and Sitka, as well as Indian villages and some of the coastal glaciers. The number of tourists increased: in 1884 there were 1,605 sightseers; in 1886, 2,753; and in 1890, 5,007. [15] In addition, the gold rush of 1898 brought up thousands of miners to Skagway, Wrangell, Valdez, and Nome. A large number of guidebooks—most of them inaccurate or of ephemeral value—were published for the benefit of those bound for the Klondike. Finally, business magnates traveled in their private steam yachts to view the country and investigate business investments. [16]

The most elaborate and significant of these expeditions was that of E. H. Harriman, the railroad magnate, in 1899. Harriman chartered an Alaskan steamer, the George W. Elder, and made what a scholar has called "the most luxurious reconnaissance in the history of nineteenth-century Alaskan scientific investigation." The expedition had cooperation from the Smithsonian Institution and the National Academy of Sciences. The group traveled to Metlakatla, Wrangell, Juneau, Sitka, Prince William Sound, the Aleutian Islands, and up to the Bering Strait, stopping periodically to explore, collect, and investigate—and on one occasion to enable Harriman to shoot a bear. The results of the expedition were published in a series of elaborate volumes that contain a mine of information on Alaska. [17]

Bernhard E. Fernow, who had just resigned as head of the Division of Forestry, accompanied the expedition and wrote a report on the Alaskan forests. He knew of the interior only by hearsay and reported the forests as poor by the usual standards. They were, however, an important source of mining timbers and of fuel for steamboats, and he stressed the need to protect these forests from fire. The coastal forests, though dense and merchantable, could not rival the forests of the Puget Sound area because of their distance from markets, difficulty in logging them, and the preference for Douglas-fir lumber. He thought their best economic use would be as a source of pulpwood. During the tour he examined and photographed the spruce plantation established by the Russians in 1805; he also examined plant succession in the Glacier Bay area. [18]

Henry Gannett, head of the Geological Survey, also made the trip and wrote on the forests. He disagreed with Fernow as to the value of the interior forests: "In this enormous region there must be a very large supply of coniferous trees, sufficient to supply our country for half a generation in case our other supplies become exhausted." On the scenery he wrote: "Its grandeur is more valuable than the fish or the timber, for it will never be exhausted. This value, measured by direct return in money received from tourists, will be enormous; measured by health and pleasure it will be incalculable." [19]

This turn-of-the-century period was marked by increasing activity on the part of the federal government to gain knowledge of the geography and resources of Alaska. The Army, the Coast Survey, and the Navy carried on active programs of exploration and reconnaissance during this period to aid reckless, improvident, or distressed miners, locate routes to the interior, and chart the coast and harbors. Most of this work came as a result of the gold rush of the 1890s. To this should be added the work of the Geological Survey, which carried on dozens of reconnaissances in Alaska. A tremendous mass of material was collected dealing with the resources, including the timber resources, of Alaska. [20]

In forestry, tangible results of this interest began shortly after Roosevelt succeeded to the presidency in 1901. Roosevelt desired information as to the possibility of creating forest reserves in Alaska, and he asked a well-known authority on Alaska, Lieutenant George Thornton Emmons, to write him such a report. Emmons, although at the beginning of his long career as a collector, was already well known as an authority on Indian culture and art. In 1886, as lieutenant on a Navy gun boat, he had furnished transportation for the Princeton-New York Times expedition to climb Mount St. Elias, and had collected Tlingit artifacts for the American Museum of Natural History and the United States National Museum. He later collected for the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, for the Columbian Exposition of 1894, and collaborated with Franz Boas on some anthropological studies. It is reasonable to suppose that Roosevelt, with his wide-ranging interests, became personally acquainted with Emmons and asked him to carry out this assignment, just as three years later he asked Emmons to carry out another Alaskan investigation. [21]

Emmons's report, sixteen handwritten pages in length and titled "The Wood Lands of Alaska," was sent to Roosevelt in February 1902. The report is a careful and scholarly document. Emmons thought that the forests of the interior Alaska were primarily of value for local use.

While the timber is generally small and of an inferior quality, yet from an economic standpoint, it is of incalculable value to the placer miner, who in the process of melting and sluicing the auriferous gravel deposits—which form the natural wealth of the region—requires wood of almost any character. And it is also very evident that at such inaccessible points fuel and lumber for the necessities of life must be at hand, while the light draft steamboats that ply the thousand miles of shallow river channels must depend on the local wood depots, at short intervals along the shores.

Emmons evaluated the forests of southeastern Alaska, including yellow-cedar (the most prized wood), Sitka spruce, and western hemlock. He remarked that the coastal area had much the same type of forest as did the islands of the Alexander Archipelago but that the timber was not of as good quality, due to the colder climate caused by the immense glaciers. There had been, he wrote, no inroads on the timber. Government regulations forbade the export of timber, so it was cut only for local use.

In making his recommendations, he wrote:

In setting aside of Government timber reservations, I understand that it is the department's desire to interfere as little as possible with the settlement and development of the country, and where conditions are equally favorable to select islands—the limits of which are clearly defined by nature—which are the more sparsely inhabited, and to this end I would suggest the following list of localities fulfilling these conditions:

(1) The Prince of Wales Island and associate islands to seaward

(2) Zarembo Island

(3) Kuiu Island

(4) Kupreanof Island

(5) Chichagof Island and associate island to seaward.

He wrote of the conditions on each of the islands. Prince of Wales Island, the largest, contained an abundance of timbered land, including substantial quantities of redcedar and yellow-cedar as well as spruce and hemlock. There were only about 800 Natives and no white settlement of any size. There were small sawmills at Howkan, Shakan, Kasaan Bay, and Hetta Inlet, and a few canneries. Zarembo Island was an uninhabited island west of Wrangell. Kuiu had a Native population of about 100 and no white settlement. Kupreanof had a Native population of about 500 with no white settlement. Chichagof Island, to the northwest, was heavily forested; it had a mission at Hoonah and a small settlement in Tenakee Inlet. The report was accompanied by a copy of the General Land Office's 1898 map of Alaska, with the islands recommended for a reserve marked by shading. [22]

Roosevelt transmitted this report and map to Secretary of the Interior Ethan Allen Hitchcock on April 15, 1902, with the following note:

This Alaska forest reservation strikes me favorably. Let us look into it and if it is proper have it done. Ought not the proclamation to be made to conform a little more fully to the real objective of the case? I have been told that at present they have rather the effect of scaring, and of conveying the idea that we are trying to drive all the people out.

The department took no immediate action. On August 9, 1902, Roosevelt's secretary, William Leob, sent a personal note to the secretary.

My Dear Sir:

The President wishes to know what has been done in reference to the forest reserves of Alaska, which reserves were indicated on the map which he forwarded to the Department with a full report of Lieutenant Evans (sic). It is the President's desire that those reserves be established at once.

Ten days later Secretary Hitchcock sent to the president a draft of the proclamation. The following day, August 20, the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve was established by presidential proclamation. [23]

There were early protests about the creation of the reserve. Representative J. T. McCleary of Mankato, Minnesota, asked reassurance that the sawmills on Prince of Wales Island—some of which were owned by Mankato residents—would be able to continue operating. James O. Rountree of Baker City, Oregon, who had mining interests on Prince Wales Island, carried the idea of forest influence on rainfall to its logical—or illogical—conclusion. "It is well known," he wrote, "that rain is attracted by large bodies of timber. The rainfall in southeastern Alaska is excessive. If the commercial timber on Prince of Wales Island were cut off, the miners would have the wood they needed for operations, the ground would be rid of its encumbering trees, the climate would become more livable, and prospecting would be easier." He claimed some support of his views by the citizens of Ketchikan, including Alfred P. Swineford, formerly governor of Alaska and at that time editor of Ketchikan's Mining Journal. However, the files of the Mining Journal do not bear out this claim. The paper noted editorially that the claims of the Daily Alaskan and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, that the reserve would prevent development of the country, were without substance. While the reserve was probably not necessary, noted the Mining Journal, regulation of lumbering would do no harm.

Protests also came from Protestant missionary groups. Harry P. Corser, who operated a mission at Wrangell, protested on behalf of the Tlingit and Haida Indians. The reserve would hurt the Indians, he wrote, because they were "loggers by occupation" and, with timber cutting regulated, would have to "revert to primitive conditions or else starve." The reserve would hamper their search for firewood. The mission was trying to persuade Indians to live in individual homes, rather than in communal houses; the reserve would hinder this effort. Corser also thought the reserve would aid monopoly and injure the small lumber operators of Alaska. It would benefit only the "millionaire lumber trusts of Puget Sound." The reserve was not needed, moreover, due to the rapid growth of timber in southeastern Alaska. Some of the areas, he wrote, had been logged over two or three times since transfer to the United States. The loggers took only the mature timber, which otherwise would die of old age. Finally, the Indians considered the land theirs by right of occupancy and inheritance, and Corser regarded the reserve as an immoral confiscation of property. [24]

The commissioner and secretary sent out reassuring letters, and the protests were short-lived. It was left to William A. Langille, one of Pinchot's westerners, to bring the reserve under administration and to handle the protests on local grounds.

|

| William A. Langille "dressed in his best suit of clothes" when called to Washington in 1902 to discuss his Alaskan duties with Gifford Pinchot and Theodore Roosevelt. The young man from Oregon pioneered federal forestry in Alaska. (Mrs. Ivan Langley Collection) |

W. A. Langille

The Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve was created late in 1902, but management of the reserve was slow in developing. Langille made some examination of the reserve in the spring and summer of 1903 and in the summer of 1904, but not until 1905 did it come under any real management. For the first six years of its management, the story of the Alexander Archipelago and of the Tongass national forests is essentially the story of one man—William Alexander Langille.

Langille came of a family that played an important part in the history of forestry and conservation in Oregon. He was born in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, in 1868. His family moved to Hood River, Oregon, in 1880. The Langille family became interested in mountaineering. Will and his younger brother, Harold Douglas Langille, made winter trips to the north side of Mount Hood on skis, dispelling the myth that the winter climate at timberline could not be endured. Their father, James Langille, helped construct Cloud Cap Inn, and in 1891 the Langille family took over its management. At that time it was one of the most attractive alpine inns in the country.

Will and Harold became guides on the mountain, taking part in such patriotic rituals as illuminating the summit with red fire on the night of the Fourth of July. They pioneered many new routes to the top of the mountain, were charter members of the Mazamas (the first mountaineering organization on the Pacific Coast), played a part in the creation of the Cascade Range Forest Reserve, and guided the Forestry Commission when it visited the Mount Hood area in 1896. [25]

At Cloud Cap Inn, the Langilles became acquainted with professors and scientists who visited the area, including William H. Brewer, Henry Gannett, J. G. Lemman, Frederick V. Coville, and C. S. Sargent. Years later, Will Langille wrote, "These men were the inspiration that awakened better things in our young lives."

In 1897 Will joined the gold rush for the Klondike. He summarized his Alaskan experience as follows:

Left Cloud Cap Inn July 23, 1897. Left Portland on S.S. G. W. Elder July 27, 1897 Left Lake Bennett for Dawson Sept. 11, down Yukon in an open boat. Arrived at Dawson Sept. 25, 1897. Left Dawson for Nome Jan., 1900, with dog team. Arrived Nome March 26, 329-1/2 hours travel time. Left Nome Nov. 10, 1902. Left Washington D.C. for Ketchikan April 6, 1903. Left Washington D.C. April 1, 1904. To Nome July 1904 via Prince William Sound and Dutch Harbor. Left Seward January 1905 to Fairbanks via Matanuska Pass & Mt. McKinley region. Left Fairbanks May 10 walked to Circle City arrived May 14. Then to Dawson, Juneau & Wrangell. Left Alaska September 1911.

Thus, briefly, Langille summarized a northern career with enough adventure in it to fill a book. In the Klondike, he shared a cabin with Jack London and became acquainted with the dog "Buck," the hero of London's story, The Call of the Wild. He hunted game for the market an the Stewart River, cooked in a restaurant in Dawson, and later became night man for the Alaska Commercial Company. Finally, feeling his "string had played out," he traveled over the winter ice to the black sands of Nome. He was prospecting there in 1902 when he received word that Pinchot wanted him to work in Alaskan forestry. Langille went to Washington to confer with Roosevelt and Pinchot on the Alaskan forests. [26]

Pinchot employed Langille as a forest expert. In April of 1903, Langille returned to Alaska to report on the administrative needs of the forests. There he made his headquarters at Yes Bay, a cannery settlement near Ketchikan. He traveled up the Stikine River by canoe to the Canadian boundary, visited mills on or near the reserve, and sailed up Portland Canal, the southern boundary with British Columbia, to investigate timber theft by Nass Indians on the American side. He returned to the states in the fall. Early in 1904, he examined and reported on a proposed addition to the Sierra (North) National Forest in California. Then in April he made a long reconnaissance from Juneau to the Controller Bay and Prince William Sound areas and thence north to Norton Bay. He returned to Valdez in the fall and spent most of the season and early winter making an examination of the Kenai Peninsula and writing up reports. Between January and March of 1905, Langille traveled by dog team from Seward to Fairbanks to examine the forests of the interior. He then returned to Ketchikan to take on new duties as forest supervisor of the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve. [27]

Langille was a man of magnificent physique, an accomplished mountaineer, and a skilled hunter. On his long overland reconnaissances, he lived off the land on rabbits and ptarmigan shot with his .22 rifle or grayling caught with improvised flies. He was a good field botanist and mammologist, an expert on mining law in Canada and the United States, and an able cartographer. His skill as a photographer dated back to his Oregon days when he took many scenic views of Mount Hood. He had a bluff, hearty manner, highly acceptable to most Alaskans. He was utterly honest and carried out his work in the face of attempted intimidation. His letters to reserve users were blunt, forceful, and at times undiplomatic. A perfectionist, he was impatient of shortcomings in others, found it hard to delegate authority, and at times seemed to his subordinates to be overbearing. Like his brother Harold, he was an accomplished writer, having a keen sensitivity to natural beauty coupled with a somewhat sardonic sense of humor. His reports are the best sources available for an accurate picture of forestry in a unique setting. [28]

In Alaska, he had as many duties as Poah-Bah of Gilbert and Sullivan's Mikado. "I can tell you of the travels of Langille and Wernstedt," wrote Melvin L. Merritt; "these stories read almost like those of the early explorers, as indeed they were." Langille traversed and mapped boundaries for the reserves, traced down timber trespass, made timber sales, acted as disbursing agent, examined mining claims, made out special occupancy permits, enforced game laws, and did cooperative work with such federal agencies as the Biological Survey, the Fish Commission, and the Geological Survey. He kept a meticulous set of books and records under the most difficult of circumstances. In addition, he explained to the Alaskans the purposes and uses of the reserve, and he kept the Washington Office informed of its needs—all on the magnificent salary of $1,800 to $2,000 per year.

Langille first set up headquarters at Wrangell, but he soon moved to Ketchikan, which was a larger trade center and where the mail boats stopped more often. He shared offices with a customs collector at first but within a month wrote, "Quarters are scarce, but I have secured a good isolated place built on pilings for twenty dollars a month, heat light water and caretaker furnished." [29]

His main problem was to secure a boat for travel around the islands and to use as an office afloat. Much of the correspondence between Langille and the Washington Office dealt with the need of a boat and its specifications, but not until 1909 was one obtained. Meanwhile, Will improvised. Records show that he traveled by mail boat a goad deal and at times chartered boats at $10 per day. During the Olmsted inspection trip of 1905, he rented a launch, the Walrus. For much of his work he chartered a sloop, the Columbia, from Peter Makinon, a Nova Scotian, at $5 per day; it had no engine. Langille was often stormbound and sometimes he and Makinon had to row the vessel for long distances because of adverse winds and tides. In 1908, however, a large gasoline launch, the Tahn, was built to Langille's specifications; it was put into service the following year. [30]

Langille worked alone during much of his stay in Alaska, but there were many companions, too. His letterbooks show that he occasionally hired scalers on a day-to-day basis. In 1905 he acquired an assistant ranger, Richard Dorwalt, a former Navy man, but he was unsatisfactory and resigned in 1906 at Langille's request. In 1908 W. H. Babbitt, a ranger from California with two years' experience, was brought up and stationed in Chomly Sound to handle timber sales there. He had a small rented launch, the Elk. A man named Howard M. Conrad also served between 1908 and 1909 as deputy forest supervisor. James Allen and George Peterson both came to the forest in 1909, and Roy Barto came to Alaska in 1910. With the creation of the Chugach National Forest, Lage Wernstedt came to assist Langille in handling the northern area. Lyle Blodgett was hired as engineer of the Tahn; he was a native of Iowa who worked his way north to Alaska by 1904 and served the Forest Service for many years. Langille also acquired a clerk named Bush in 1908. [31]

|

| Lyle Blodgett (in cook's cap) and unidentified companions aboard the Tahn. (George Drake Collection) |

The population of the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve was mainly engaged in mining and fishing. There were several types of mines in the area, located principally on Prince of Wales Island. These included copper prospects in the Hetta Inlet area and at Niblack; and marble quarrying on both the northwestern and southeastern coasts of the island. Most of the mining claims had not passed to patent. There were dozens of fisheries and salteries within the reserve limits. Both the mining companies and the fisheries used the timber—the miners for buildings, tramways, and timbering, and the fishermen for their docks, buildings, fish boxes, and dory construction.

There were only a few small sawmills on the reserve in 1905. These included a mill on Kasaan Bay with a 25,000 board-foot capacity per day, but idle in 1905; one at Hunter Bay, capacity 10,000, owned by a fishing company; a small mill at Howkan, capacity 5,000; a waterpower mill at Coppermount that cut 600,000 feet in 1905; one at Shakan, then being rebuilt to have a capacity of 50,000; and two small mills of limited capacity in Wrangell Narrows. The larger mills, which used timber rafted from the reserve or from the mainland, were those at Juneau, Douglas, Wrangell, and Ketchikan. [32] They were not located on the reserve.

Sentiment toward the reserve in the beginning was mildly hostile. Langille wrote to Pinchot in 1903 that he found Wrangell the main center of discontent. Some hostility flared up when Langille became supervisor in 1905, because the inattention of the government since 1902 had given many people the idea that nothing would be done in reserve regulation. General Land Office officials were frankly hostile toward the reserve. Recorders of mining districts claimed that they had never been officially notified of its creation and, as late as 1906, were recording any land claim even though they knew its location was a trespass on the reserve. [33]

The "bellwether" of the antireserve forces was U.S. Rush of Kasaan Bay. Rush was one of the owners of the Rush and Brown Copper Mine at Karta Bay, an arm of Kasaan Bay. Powerful in local politics, he had been U.S. commissioner for the area but resigned his post in order to attend the Republican territorial convention and introduce a plank calling for abolition of the reserve. Writing to Theodore Roosevelt on October 17, 1905, he asked for abolition of the reserve for a variety of reasons. He claimed that, first, there was not enough good timber to justify a reserve; second, timber was not necessary to insure rainfall in the area; third, the country was chiefly valuable for minerals; fourth, all available timber would be needed for development of the country; fifth, use of timber and occupancy of the land should be a right, not a privilege; sixth, inability under the law to gain title to the land retarded development; and seventh, the rules for forest management when applied to Alaska were not suitable for the territory. A man of many grievances, he elaborated on them in letters to Pinchot, Langille, and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. [34]

|

| U.S. Rush, mining entrepreneur of the Ketchikan area and archfoe of the Forest Service. (Tongass Historical Society) |

Faced with these protests, Pinchot sent Frederick E. Olmsted, assistant chief in charge of general inspection, to examine the Alaska forest situation in 1906. He was to examine not only administrative problems but also the possibility of creating new reserves. Olmsted discussed Rush's problems with him in Alaska; toward the end of their discussion, Rush remarked that the system was one "perfectly constructed for the intrusion of graft." Thereupon, Olmsted wrote, "The small amount of self-control which still remained with me gave out, and I at once refused to discuss the forest reserve system with him any further." [35]

Olmsted made a detailed study of public sentiment toward the reserve. He found sentiment friendly in Ketchikan and Juneau, where the largest mills and users of lumber were located. Ketchikan's Mining Journal strongly supported the reserve. At Shakan, sentiment was also friendly. Wrangell and Petersburg were centers of the opposition, with the Wrangell Sentinel the strongest antireserve paper. There was also hostility at Coppermount and Kasaan. Many, however, were indifferent to the reserve and its policies. Governor Wilford B. Hoggatt, as time went on, became a supporter of the reserve, but both the Republican and Democratic parties, in their 1906 territorial conventions, adopted planks calling for its abolition.

There were many reasons for favoring, or failing to favor, the reserve. The proprietors of the Dunton & Inman Shingle Mill and the Ketchikan Power Company obtained some of their lumber from the reserve; they favored it and desired to see all the country in a forest reserve. If this were the case, they argued, they would know just what to pay for timber and where to cut it, instead of having it settled as a trespass case. The manager of the Treadwell Mine and of the mill at Douglas (owned by Treadwell interests) favored the reserve on the same grounds and advocated its extension. On the other hand, mill owners at Petersburg and Wrangell objected to the reserve on the ground that timber on the public domain was cheaper. Mining companies at Niblack, Dolomi, Sulzer, and Coppermount complained about slowness in negotiating sales and in scaling. Many believed that the mines should have free timber, and others objected to Langille's examination of mining claims.

Boundary Work in Southeastern

Alaska

As a result of his 1903 explorations in southeastern Alaska, Langille recommended creation of a reserve on the mainland, as far north as Lynn Canal, to include Wrangell, the Sumdum mining district, and Native villages. Pinchot conferred with him on these reserves during the winter of 1903-1904, but no action was taken at that time. [36]

In 1906 Olmsted strongly recommended putting the whole area from Mount St. Elias to Portland Canal into a reserve. Olmsted gave a number of reasons for this sweeping recommendation. [37] One was the anomalous situation in regard to timber sales on the unreserved and unappropriated public domain, as opposed to the forest reserves. Although the secretary of the interior had full authority under the act of May 14, 1898, to sell timber in Alaska to mill operators, no timber had ever been sold under this law. [38] Instead, the standard procedure was for the logger to go where he pleased and cut whatever he wanted, without getting permission from anyone and without notifying any official of the action. Once a year each mill was visited by a special agent of the General Land Office who would inquire how much timber had been cut. Settlement was made on the basis of innocent trespass, at twenty cents per thousand board feet for sawtimber, one-half cent per linear foot for piling, and twenty-five cents per cord for firewood. There was no supervision of the cutting or allocation of cutting areas. Further, Olmsted thought there was an element of hypocrisy in having all mill owners regarded not as trespassers but as "innocent thieves." They had no assurance that trespass would not be looked upon at some future time as deliberate trespass—and triple damages assessed. The need for a businesslike management of sales was, in Olmsted's opinion, a strong reason for bringing the area under Forest Service supervision.

Forest Service jurisdiction, Olmsted believed, would not interfere with legitimate development of the area. Mining claims would be examined by the Forest Service, but this would not prevent legitimate claims from coming to patent. There would be little use of the Homestead Act, since arable lands are scarce in southeastern Alaska. There was need, Olmsted felt, for the Trade and Manufacturing Act to be applicable on forest reserve lands, as it was on the public domain in Alaska.

Another reason for creating a reserve, in Olmsted's opinion, was the fact that sawtimber on the reserve sold for fifty cents per thousand feet, while across the channel on the public domain it sold for twenty cents. The timber was worth fifty cents and more, and Forest Service management would bring in more revenue. In fact, Olmsted thought, it would make the reserve self-supporting. Finally, Olmsted wrote, though there was at present no danger of large bodies of timber falling into the hands of corporate interests, Puget Sound interests might look eventually to Alaska with the intention of making speculative investments. The land could be best preserved in federal hands by creating a forest reserve including all of southeastern Alaska, "bounded by the international boundary on the south, east, and north, and by the 141st meridian and the open sea on the west." [39]

Olmsted's recommendation and those of Langille were studied in detail, and in 1907 plans were made to withdraw most of southeastern Alaska into a forest reserve, or national forest, as they were called beginning that year. A map was prepared, marking the area to be withdrawn under the name of the Baranof National Forest. But at this point the Forest Service came up against the opposition of the commissioner of the General Land Office, Richard A. Ballinger. Ballinger strongly opposed the creation of any national forests in Alaska, and he was already exasperated by plans to create the Chugach National Forest. A conference involving Ballinger, the Forest Service, and the law officers of the Forest Service and the Land Office resulted in the map being withdrawn. Meanwhile, Langille prepared an alternative, and less controversial, suggestion. [40]

Langille's recommendation was a 2-million-acre tract of land on the mainland, with natural geographic boundaries, from Portland Canal on the south along Behm Canal to the Unuk River and up the river to the international boundary. The area, he reported, was rough, unfit for agriculture, and had no permanent habitations except a mining company on the Unuk River. "The only objection to creation of the reserve, he wrote, "will come from those who oppose the national forest policy on general principles." The area was well forested, through much of the area available for handlogging had been partially cut over since 1905. In the future, he believed, cable logging would be the general practice.

There was local support for the proposed national forest. The Ketchikan Power Company favored Forest Service control in order that it might export its lumber. Governor Hoggatt and the businessmen of Ketchikan favored the addition. Moreover, the Alaskan timber along the Portland Canal would be protected against Canadian depredations. Langille stated that while it was not known that timber theft was occurring at that time, it had happened in the past, and the rapid development of recent mineral discoveries in British Columbia would create a demand for timber and induce someone to take it from the Alaskan side. [41]

|

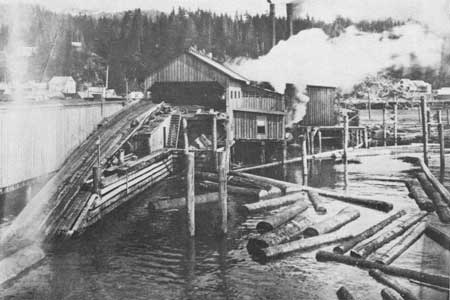

| Original mill of the Ketchikan Power Company, about 1905 to 1910. (Tongass Historical Society) |

Ballinger, commenting on Langille's report, remarked that he was opposed to the creation of any national forests in Alaska because the forests were not needed to preserve the water supply, there was no fire hazard, and there was no need for artificial reforestation. His assistant commissioner, Fred Dennett, was highly critical. Citing Langille's report to the effect that the Ketchikan Power Company wanted the national forest in order to be able to export timber, he termed the project a "conspiracy" designed to evade the law forbidding export of timber from Alaska. Notwithstanding these objections, a draft of the proclamation was prepared in July of 1907, and the formal proclamation creating the Tongass National Forest was made on September 10, 1907. [42] On July 1, 1908, the Alexander Archipelago and the Tongass were consolidated into a single national forest, the Tongass, with a total area of 6,756,362 acres.

The Forest Service continued studies of further national forest extensions between 1907 and 1909. There was general agreement that the remaining islands of the Alexander Archipelago and the mainland from Skagway south should be reserved. The resignation of Ballinger in 1908 as commissioner of the General Land Office eliminated a major enemy of such an enlargement.

Consideration was given during this time to the area between Yakutat Bay and Dry Bay. Langille had traversed this area in 1904 and had reported commercial forests on the coastal plain, extending sometimes three to five miles back from tidewater, of Sitka spruce, hemlock, mountain hemlock, and yellow-cedar. The timber, particularly the hemlock, tended to be defective and overmature, but there were numerous isolated bodies of sound timber. The only lumbering activity in the area was at Yakutat Bay, where the Yakutat and Southern Railway Company had a mill capable of cutting 35,000 board feet a day and was engaged in cable logging. In 1903 the mill cut 13 million board feet. Langille reported that a great deal of the land was alienated, much of it filed on as placer claims, although "the individuals making them have not the slightest intention of ever doing a cent's worth of assessment or development work. In most cases the persons in whose names they were staked never saw the land nor did they ever think of seeing it." Many of the claims covered forest land. Langille thought that a national forest would be needed for future use and to prevent waste in its utilization, but, due to the large amount of alienated land, he recommended in 1904 that no reserve be created at that time.

In 1908, at Pinchot's request, Langille reviewed his recommendations for the area near Yakutat Bay. He noted that the General Land Office, in June of 1903, had initiated a timber sale policy instead of settling on the basis of innocent trespass. The Land Office sold the timber at $1 per thousand board feet—after examination and approval of the tract by a special agent. But whereas the Forest Service distributed 25 percent of the proceeds of a sale to the district in which the timber was cut, all proceeds of Land Office sales went to the U.S. Treasury, except 1 percent as a fee to the register and receiver of the local office. The Forest Service, moreover, had trained men to handle the sales and could handle them more economically and promptly than the Land Office. In regard to the Yakutat area, Langille noted that there had been little change since 1904, except that the placer claims had been abandoned. The Yakutat and Southern Railway was extending its line to the south in order to reach timber bodies on the Alsek River. Langille recommended creation of a Yakutat National Forest to include the west side of Yakutat Bay to Cross Sound and from the ocean to the international boundary. To the south, he recommended addition of all the area between the 141st parallel and the international boundary to the Pacific Ocean, except for areas around the towns of Haines and Skagway and the major cities in the Alexander Archipelago and the mainland. [43]

In 1909 the Forest Service made recommendations for withdrawal of the remaining islands, the mainland to the south of Skagway to Icy Strait, and the area from Dry Bay to the south shore of Yakutat Bay. On February 16, 1909, the second proclamation relating to the Tongass added 8,724,000 acres to its area. [44]

|

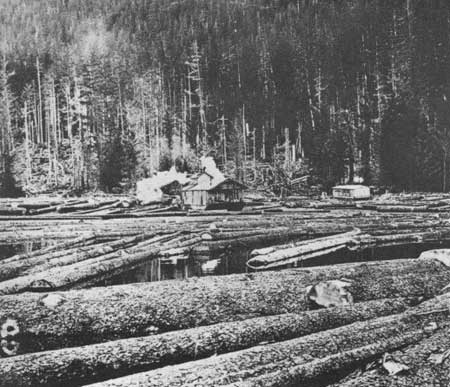

| National forest timber sales were claimed to furnish labor to Native tribes. This typical logging camp was located on the Tongass, and handlogging was the rule. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Timber Sales

Timber sale problems and policy in the Alaskan national forests differed from those in the states. In the older states and territories much of the timber was in private hands; in southeastern Alaska virtually all the timber was owned by the national government. In the states the reserves were isolated and largely remote from population centers. They were used to supplement settlement and development in their vicinity. In southeastern Alaska, with creation of the national forests, the miners, fishermen, and lumbermen were already living within the newly created reserves.

Moreover, there was an immediate need for the timber. In the states Pinchot encouraged timber sales to persuade Congress that the national forests were reserved for use, rather than from use, and to bring in revenue. He faced two obstacles. First, many men in regional offices—among them E. T. Allen, Fred Ames, and Thornton Munger—believed that silvicultural studies and a preliminary forest inventory should take precedence over sales. Second, once private companies had title to the most accessible timberlands, they were not particularly interested in national forest sales. [45] In Alaska, on the other hand, there was a continuous demand for timber for local use, and the only local source of such timber was the national forest.

There were other anomalies in the timber situation. Federal law forbade the export of lumber from Alaska, but, on the other hand, lumber cut on national forests could be exported. Forest Service timber sold at fifty cents per thousand board feet, and General Land Office timber at twenty cents. The policies were contradictory and confusing. In addition, the Forest Service Use Book, designed to establish sales rules in the West, did not always apply to Alaskan conditions in regard to slash disposal, marking of trees, and scaling regulations. There were many questions unanswered. To whom did driftwood or unmarked logs belong? What free-use provisions applied to users of the national forest? What were the rights of the Indians?

Langille's first efforts at timber sales management in 1905 were concerned with settling timber trespass cases. Cutting had continued on the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve in the interim period between its creation in 1902 and the time it came under active management in 1905. With characteristic zeal and energy, Langille tracked down and settled trespass cases. Most of the cases settled in 1905 involved cutting in 1903 or 1904 and were settled on the basis of unintentional trespass. In each case, the trespassers denied any intention of wrongdoing. They professed that they did not know reserve regulations applied, or thought they might cut for their own use, or assumed canneries had free use of timber for cordwood. Langille assessed them the stumpage value of the timber: fifty cents per thousand for sawtimber, one-half cent per linear foot for piling, and twelve and a half cents per cord for cordwood.

|

| Logging operation at Whitewater Bay, ca. 1909. (U.S. Forest Service) |

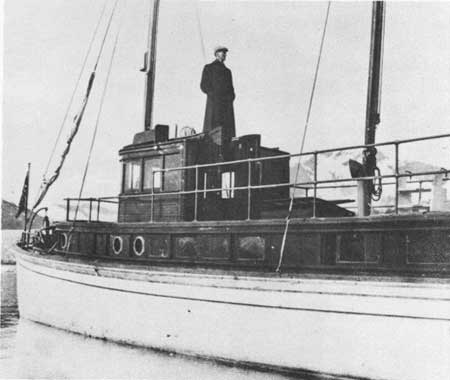

|

| Fred Ames on the deckhouse of the Tahn, flagship of the "Tongass Navy." Ames made an inspection tour of Alaska in 1909. (Mrs. Ivan Langley Collection) |

There were, however, two cases of intentional trespass; in these Langille took strong and drastic action. One case involved the Alaska Copper Company at Coppermount, one of the centers of antireserve sentiment. Langille seized the logs at the mill, shutting down operation for the time being. Of this action Olmsted wrote, "I believe that strong and decided action was necessary in order to convince this company that a certain respect far law and the officers of the Forest Service were matters not to be overlooked, and that Mr. Langille's action was quite justified." The other case involved the Wilson and Sylvester mill at Wrangell. Timber cut by one A. M. Tibbets on Zarembo Island was towed in a raft to Wrangell by the Wilson and Sylvester tug. Tibbetts at first denied, then admitted, cutting the timber, but all persons connected with the mill, in Langille's words, "denied any knowledge of the logs coming from reserve land, denied ownership of the logs, or making payment when in their possession, and payment had been made on them." Langille seized the logs, scaled them, and posted warnings to all persons against removing them. He recommended to Pinchot that the Wilson and Sylvester Company pay full value on the logs at time of seizure ($4 per thousand board feet) and that Tibbetts pay fifty cents per thousand stumpage value. On the authorization of the secretary of agriculture, Langille posted notices offering the logs for sale to the highest bidder—the sale to take place before the Wrangell courthouse at 2 P.M., November 20, 1905. At this point the Wilson and Sylvester firm acknowledged ownership of the logs, and settlement was made on the basis of intentional trespass ($3 per thousand). [46]

In 1905 Langille made sales of 526,371 board feet of sawtimber, 976 cords of wood, and 93,820 linear feet of piling. Twenty-two cases of trespass were settled, amounting to 1,173,528 feet of sawtimber, 43,186 feet of piling, and 733-1/4 cords of wood. Sales for 1906 (from January until October) amounted to 6,881,070 feet of sawtimber, 35,600 feet of piling, and 2,310 cords of wood. With the additions to the reserve in 1909, sales exceeded 15 million board feet. [47]

Operations were primarily handlogging; as late as 1905 there was only one cable operation on the reserve. The loggers, Indians and whites alike, cut trees under contract with the mill, mining company, or cannery concerned. Trees were cut close to the coast—in almost every case so close that the tops reached the water. Hemlocks eighteen inches to two feet in diameter were felled to use as skids to ease the logs into the water. Logs were rafted and towed in rafts of up to 200,000 board feet to the mill. In the raft they were priced at $4.50 per thousand; stumpage was fifty cents and towage from fifty cents to $1 per thousand. The cutting was wasteful; there was a great deal of breakage and poor utilization of the tops. The hemlocks cut for skids were left in the woods. There was no attempt to clear up the debris from logging, but there was also no fire danger. Logs were scaled in the raft, usually at the site of cutting.

Langille was concerned with the effect of logging on the fishing industry, and in 1909 he worked out regulations with the Bureau of Fisheries to preserve salmon runs. These regulations included prohibiting logging on streams with established salmon hatcheries, such as the Naha River, McDonald Lake and stream, and rivers and creeks in the Boca de Quadra, Klawak, and Hetta Inlet areas. On all other streams with runs of salmon, logging was prohibited between August 1 and December 1. No logging would be permitted in stream beds and no debris or obstructions should be left in the water. [48]

In his inspection report of 1906, F. E. Olmsted recommended various changes in the Use Book to apply to Alaskan conditions. He recommended, for example, a liberal interpretation of the free-use clause. He felt that the confusion in the law, with one law forbidding export of lumber from Alaska and another permitting export of lumber cut on forest reserves, should be clarified. He advised that it be advertised widely that timber cut on the reserves could be sold outside Alaska, and that the Treasury Department instruct its collectors to clear timber from any point on the reserves to foreign ports or those in the United States. He saw no need to mark trees for selective cutting, since the hand-loggers took single trees located on the shores of a beach or inlet. Rather, the forest officer should only designate the general area in which the trees were to be cut. Olmsted suggested that cutting small trees to be used as skids should not be considered as unnecessary damage, provided that spruce not be used when hemlock was available.

By 1910 Forest Service cutting policies were becoming accepted by logging interests on the Tongass National Forest. Governor Walter E. Clark, investigating a complaint by F. S. Wilson on the handling of timber sales, found no complaint as to the charge for stumpage, or in general to Forest Service management policies. He found the only justifiable complaint to be that which Olmsted had noted: inadequate transportation, resulting in delays in cruising and scaling the logs. Aside from this, Clark felt the Forest Service did an adequate job. Fred Ames, in his inspection tour of 1909, noted that the sale sites were characterized by high stumps and inadequate utilization of tops. Like Olmsted, he recommended more boats. Ames noted an increased amount of cable logging, largely limited to areas within a thousand feet of the beach. Most of the cutting was still for local use, though the Ketchikan Power Company had found a market for clear spruce in Seattle. George Cecil, in a 1910 inspection, felt that the main needs were for long-term sales and establishment of a pulp mill. He suggested revision of the land laws and regulations to suit Alaskan conditions, including that of permitting purchase of land for business purposes. Scaling, he said, should be at the mill rather than at the place of cutting. [49]

|

| A crowd gathers at the dock in Ketchikan. (Tongass Historical Society) |

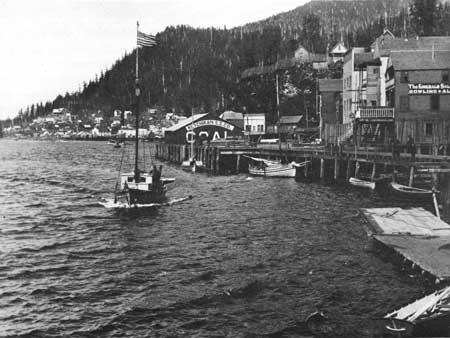

|

| Early view of the waterfront in Ketchikan. (Tongass Historical Society) |

Land Titles

The question of land title was complex. It involved the status of alienated land within the national forest, the validity of land titles, the manner by which land could be acquired within the forest boundaries, and the relationship of the Forest Service to the General Land Office.

When the reserve was established in 1902, there were no perfected land claims within its borders. Some of the lands were held through squatters' rights, still others through purchase or intermarriage with Natives, and others through application of the Trade and Manufacturing Act—largely for speculative purposes. Law permitted application of the soldiers' additional homestead scrip (a benefit for veterans), but the scrip was expensive and apparently was not used. There was virtually no use of the Homestead Act (though later the Forest Homestead Act of 1906 was extensively used), and the Timber and Stone Act did not apply in Alaska. Many tracts had been filed on as mineral claims by 1906, and two islands were operated as fox farms under Interior Department leases. The Trade and Manufacturing Act had not, by 1906, been applied to the national forests of Alaska. [50]

One of the first needs, then, was establishment of rules governing occupancy of national forest lands. This gave Pinchot the opportunity to establish a precedent for charging grazing fees for livestock in the national forests, a plan sure to meet with opposition from western stockmen. He needed a legal opinion from the attorney general as to the right of the Forest Service to charge such a fee, but he hesitated to raise such a controversial issue. Early in 1905 an application came for a permit to occupy an area on Grace Harbor for a salmon saltery. Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson sent a letter, prepared by the Forest Service, asking the attorney general if the Forest Service could issue such a permit or lease for the occupancy of forest reserve land, and whether the Forest Service could require compensation for the occupancy. Attorney General William H. Moody replied that such leases or permits could be given and a fee charged. This precedent permitted Pinchot to charge for occupancy of the range, as well as for the shoreline. [51]

Given the authority to issue such permits, Langille received fifteen special occupancy requests in 1905 and granted five. The requests involved land for tool-sheds, stores, mineral springs bathhouses, fox ranches, houses, fish canneries, a powder house, a cold-storage plant, gardens, and rights-of-way for tramways. A lease was usually granted for a year; it was renewable and terms were nominal. [52]

The question of mining claims became vexing. Alaska operated under United States mining laws. Previous to the creation of the reserve, it had been an easy matter to get any claim patented. Officials of the recording districts considered it desirable to allow patent whether or not a claim contained mineral—and without regard to assessment work. The creation of the reserve changed all that.

Because surface rights, including timber, went with the mineral rights, Langille made his own examinations and reported actual conditions as required by law and regulation. This stirred up opposition to the reserve. Olmsted wrote:

I have carefully looked at his [Langille's] reports on mining claims and believe them to be just in every way. The difficulty is that the mining laws are not complied with and Mr. Langille so reported. To put it plainly, and to touch on a delicate subject, the Deputy Mineral Surveyors made reports which were not in accord with the facts, and the local Land Office took favorable action on these reports. Mr. Langille reported actual conditions, and upon his recommendation the General Land Office refused patent. In most of these cases it was desired to secure lands for purposes other than those contemplated by the law under which entry was made. [53]

Two cases may be cited. The Alaska Copper Company was refused patent on a mill site claim at Coppermount, and the claim was cancelled. There were two saloons an the claim. One was, in Olmsted's words, "an exceeding low down resort in every way; it may be called, in polite language, a saloon, but in actual fact it is nothing but a house of ill fame." The saloon was on ground occupied by a squatter in 1900. He had sold whatever right he had to the land in 1902, and the new owner in turn sold out to the saloon owner in 1906. The company claimed that the squatter's rights extended to present occupants. The other saloon occupied land under a lease from the president of the Alaska Copper Company—a company that had not title to the land. [54]

A second case resulted in the elimination from the forest of a tract of 11,878 acres on the Kasaan Peninsula. The background of this matter involved the claims of the Brown-Alaska Company and its subsidiaries. This company had established Hadley, a mining town, at Lyman Anchorage on the Kasaan Peninsula. On the mining claim were a hotel, store, and smelter. Langille, on examining the claim, recommended that it be refused patent because there had been no discovery of minerals or assessment work on the claim. An additional complication was that one Hans Anderson ran a saloon on a mining claim leased by the company. Robert Pollock, an employee of the Brown-Alaska Company, also had established claims and done the necessary assessment work but was using the claims for purposes not wholly consistent with their development. In addition to the mining, Olmsted reported, "there are two cabins on the claim, which are inhabited by various and sundry women of ill repute from whom, it is reported, the claimant receives a rental of $100.00 per cabin." [55]

In February 1907 the Brown-Alaska Company began to put pressure on the Forest Service to eliminate the area from the national forest. The officers of the Brown-Alaska Company and its subsidiary, the Alaska Smelting and Refining Company, made solemn affidavit that there was little timber on the area and that they needed the land to develop their claims. Langille informed Pinchot in March that he opposed any elimination. The sole purpose of the Hadley interests, he wrote, was to avoid a forest officer report on the claims soon to come to patent. The company, he asserted, wanted the claims for townsite purposes, not mining. He believed that the Brown Alaska Company was violating the law and opposed the elimination of any area from the reserve until the right of the company to the land was determined.

The company brought political pressure to bear. Attorneys Brown, Leckey and Kane of Seattle protested Langille's action in filing information with the General Land Office that there had been insufficient assessment work to bring the claims to patent. This was, M. C. Brown wrote, "a piece of officious intermeddling." The company apparently protested to Senator Francis Warren of Wyoming, a leading foe of the reserves, and he protested to Pinchot. In May Pinchot recommended reducing the reserve area by eliminating most of the Kasaan Peninsula. Apparently he thought the value of the timber involved was not great enough to risk a political battle. [56]

There is a sequel to the episode. In 1924 the claims and town were abandoned. In that year, J. M. Wyckoff, Ketchikan district ranger, recommended that the area be restored to the Tongass National Forest. On June 10, 1925, the area was reacquired. [57]

Grazing, Game, and Totem Poles

Grazing was a major problem in reserves in the West, but in southeastern Alaska the problems were nonexistent. F. E. Olmsted's report on grazing in 1906 deserves to be quoted in full:

Foxes are the only live stock on the reserve, and they graze on salmon at the rate of 4 cents an acre.

There is a trespassing mule somewhere in the Klawak region but he cannot be located.

Attempts at grazing cattle have absolutely failed on account of the ruggedness of the country and the prohibitive cost of winter feeding. The same holds true for sheep. [58]

In southeastern Alaska, as in the north, Langille knew that the game laws were shamelessly abused. Many camps hired men to hunt deer, and these men killed does in and out of season. On occasion Langille took drastic action; at Shakan he seized two does killed by Indians for the Alaska Marble Company. When the company denied any knowledge or responsibility for killing them, Langille turned the deer over to some poor Indians. He believed that the forest officers should be deputized to enforce game laws and also be made assistant fish commissioners. At Indian villages, he warned Natives that any dogs caught running deer would be shot. [59]

Langille also played an important part in the preservation of American antiquities. The Antiquities Act of 1906 permitted the president to set aside as national monuments areas containing natural wonders or historic and prehistoric sites if they were on federal lands. Administration of such monuments was to be in the hands of the agency having jurisdiction over the lands. The secretaries of the interior, agriculture, and the army agreed to allow the Smithsonian Institution to pass on all applications for archaeological excavation or collection. Gifford Pinchot, in his Forest Reserve Order No. 19, required all field personnel to report on natural curiosities in their districts and to recommend suitable sites as national monuments. [60]

F. E. Olmsted examined many such areas during 1906 on his inspection trip through the West. When Olmsted arrived in Alaska, Langille recommended to him that the totem poles and community houses at Tuxekan and Old Kasaan be set aside as monuments. [61] Olmsted strongly supported the recommendation and further suggested that the poles be preserved in situ rather than be removed to another place, even though the Indians had lost interest in them. Title to the poles rested with the individual owners or clans, though the land belonged to the United States. Olmsted's recommendations were put in a letter from the secretary of agriculture to the secretary of the interior, but no action was taken for a decade. [62]

Langille later played an important part in the creation of Sitka National Monument. The governor of Alaska had recommended in 1890 that the site of the Indian village at Sitka, where the Russians won a battle in 1804, be set aside as a public park. It was so declared on June 21, 1890, but the lands were not protected from vandalism. The Arctic Brotherhood, Sitka Post No. 6, desired better protection and in November 1908 asked Langille's advice. He recommended that they prepare a petition asking for national monument status, together with photographs. He volunteered to prepare a sketch map of the area and see to its transmission to the president. These were duly prepared. Langille then sent the petition and illustrated report to the district forester, who transmitted the documents to Pinchot with an approving note. The area was not within the national forest, but rather within the Sitka elimination. Langille called the project to the attention of Governor Walter Clark, and he heartily approved it. Secretary of Agriculture Wilson submitted the reports, recommendations, and photographs to the secretary of the interior, and on March 23, 1910, Sitka National Monument was created by presidential proclamation. [63]

Inspections—Olmsted, Ames,

and Kellogg

As mentioned earlier, Pinchot sent F. E. Olmsted on an inspection trip to Alaska in 1906. Olmsted had graduated from Yale in 1894 with a degree in engineering and went to work for the U.S. Geological Survey. He met Pinchot while the latter was forester for the Vanderbilt estate in North Carolina, and Olmsted too decided on a career in forestry. He studied at the Biltmore Forest School and at the University of Munich and then went to work for Pinchot in the Division of Forestry in 1900. He was in charge of boundary work from 1902 to 1905. He then wrote The Use of the National Forest Reserves and the Use Book, the latter a manual of information, directions, regulations, and instruction for forest officers. [64]

Olmsted was the first professionally trained forester to make a detailed examination of the forests of southeastern Alaska. His inspection report of 1906 is a mine of information on the forest. [65] It is also basic source material on the social, economic, and intellectual characteristics—the "political ecology," to use the terminology of George Rogers and Ernest Gruening, of the region. [66] Cruising in the launch Walrus, Langille and Olmsted visited all the settlements in the area. They made a special effort to see everyone connected with the forest reserve and to discuss relevant matters with them.

Olmsted, a strong proponent of decentralization, praised Langille highly as an able, conscientious, and trustworthy forest officer who had been criticized much the same as forest reserve officers had been in the western states a few years earlier.

He has had to contend with just the same opposition, due largely to ignorance and misunderstanding of the objects of the reserve, and besides this has had to meet the universal feeling that still clings in Alaska to some extent that all laws are pretty well out of place "north of fifty-three" and that the people should be left alone to do as they like. I believe that the "Pioneer" plea is somewhat unduly cherished in southeastern Alaska and that the industry and energy of the people have already lifted the people out of that stage in a great many ways.

Criticisms of Langille had centered around his reports on mining claims and timber trespass. Olmsted thought Langille's actions were proper and thoroughly justified, but his "abrupt, outspoken and occasionally mildly terrifying manner" sometimes antagonized people. Olmsted recommended that Langille be commended for his work and given a salary increase of from $1,800 to $2,000 per year—but be urged to be more diplomatic. [67]

At the time of Olmsted's visit in 1906, Langille was running the reserve single-handedly. Olmsted recommended the appointment of a deputy supervisor to handle matters in the northern part of the reserve, from headquarters in Juneau. There were, he wrote, "none of the ordinary ranger duties of those officers in the states; no road or trail building, no fire patrol nor fire fighting, and no stock to look after. Their chief duties are to sell timber, scale logs and report on mining claims (together with a good deal of special privilege work) and they must be able to do these things well and without help." He emphasized, however, that the key was not men but transportation. He echoed Langille's plea that the proper running of the reserve depended upon the acquisition of satisfactory boats, writing, "Spike the supervisors of the Sierra Reserve to a rock at the top of Mt. Whitney and instruct them to run the reserve; that's the position of the officer in Alaska without a boat." He recommended a sixty-foot boat, with an engineer and a cook, to be used by the supervisor both for transportation and as an office afloat. The vessels for his deputies, he thought, could be auxiliary-engine yawls, but they must have sleeping quarters on board. The costs ordinarily put into reserves with roads, trails, cabins, telephone lines, and protection should be put into transportation in Alaska. The candidate for deputy supervisor should be able to demonstrate skill in boat handling and navigation, which, in coastal Alaska, were the equivalent of horsemanship in the states. [68]

In administrative use, Olmsted advocated extending the Trade and Manufacturing Act to land within the national forests, so that fishermen, settlers, and canneries could obtain title to the land they occupied. Regulations should also permit settlers to take up home lots. No permits would be required to build trails within the national forest, and the free-use clauses in the Use Book should be liberally interpreted. [69]