|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 3

The Chugach National Forest Through 1910

Regarding this country I have this to say that it suits me to perfection and I am going to stick to it right here as far as this depends on myself. Here we have an absolutely virgin country, unscarred by fires and uninhabited and unexplored except for those little spots where man has put up a few shacks. The land is covered by timber, snow and glaciers, and in the wilds there roam the bears, and the porcupines, the mosquitos, the crab, the shrimp and the whale. The rainfall is amazing. It rains 24 hours a day and after the rainy season is over the snowy season begins. We do not mind that, however. Imagine a country where for a thousand miles—from Cook Inlet to Ketchikan—there is not, nor ever was, a dry spot large enough to set a weary ass on.

—Lage Wernstedt to Arthur Ringland,

August 20, 1908, in Historical File,

Cordova Office, U.S. Forest Service.We're too slow for the new breed of miners,

Embracing all classes of men,

Who locate by power of attorney

And prospect their claims with a pen;

Who do all their fine work through agents

And loaf around town with the sports,

On intimate terms with the lawyers,

On similar terms with the courts.

—Sam C. Dunham, "The Lament of the Old Sourdough,"

quoted in S. A. D. Puter and Horace Stevens,

Looters of the Public Domain (Portland, 1908), p. 439

Boundary Work: The Norton Bay

Area

In 1904 W. A. Langille received his field orders for the year from Pinchot:

Dear Sir:

During the season of 1904 you will undertake the examination of the forest lands contiguous to the coast of western Alaska from Lynn Canal to the Alaskan Peninsula, including Kodiak Island and other islands lying in the forest region; then proceed to the Norton Bay country via Dutch Harbor and Nome to examine the lands included in the withdrawn area designated as the "Proposed Norton Bay Forest Reserve." Upon the conclusion of this examination you will return to Dutch Harbor and proceed to the Sushitna Valley, make an examination of this and the tributary valleys, and return to this office upon the conclusion of the season's work unless otherwise ordered.

Your route of travel will be to Juneau, Alaska (via Seattle, Washington), where you will procure, if possible, a small seaworthy sailing craft with an auxiliary gasoline engine to be used in case of emergency, and will cruise along the western Alaska coast. You will confine your observations to the coastal line in the glaciated region, but will penetrate the valleys of the larger streams. Note particularly the extent, quality, and accessibility of the forests in the vicinity of the mines, salmon canneries, saw mills, oil fields, and contemplated railroad terminals.

Special attention should be paid to species, age, and distribution of the forest bodies in different sections, noting relative sizes, etc., in reference to geographical, physical, and altitudinal position.

In the absence of any surveys in the Norton Bay region, you will determine approximate positions and boundaries by the use of the plane table stadia or other means, mapping streams and prominent topographical features as accurately as possible.

Very truly yours,

(Signed) Gifford Pinchot

Forester [1]

|

| Gifford Pinchot gave W.A. Langille detailed directions for reconnaissance work in Alaska but allowed him great latitude in the administration of the new forest reserves. |

Langille's letters illustrate the difficulties of transportation in Alaska at that time. He was able to obtain a suitable vessel in Juneau, so he traveled up the coast to Orca on the Santa Anna. At Kayak Island he secured a launch to make a reconnaissance of the shore, but the launch ran out of fuel and he left it at Ellamar. At Ellamar he was unable to take the steamer Dora to Dutch Harbor. There he made connection with the Victoria for Nome, where he was delayed in landing for five days until July 15 because of storms. Storms again delayed his departure for the Norton Sound area until after July 20. There he acquired a camp hand, A. A. Eubanks, and one pack horse and set out from Council City on July 26. [2]

"I met me Waterloo in the Norton Bay region," Langille wrote:

Most of the time the weather was intolerable. My camp hand proved incompetent, and to make bad matters worse I cut my instep with the axe, laid up ten days, traveled too soon, opened the wound, it developed proud flesh, we got out of supplies then had to raft down the Tubutulik, found some Scandinavian fishermen who took us in, were stormbound on Norton Bay six days, but arrived in Nome in time to catch this ship for Unalaska.

For 26 days we never saw a soul, white or Eskimo, until we reached the coast, then I couldn't get a native to cross country with my man—"too much wet"—he never would have found his way alone, I couldn't walk, so it forced me to trade the horse for passage up the coast, all regulations to the contrary not withstanding, very joyful. [3]

He took the St. Paul from Nome to Unalaska Island but missed passage on the Dora to Valdez by a day, thus facing the prospect of laying over at Dutch Harbor for thirty days. Rather than do this, he persuaded the captain of the St. Paul to take him all the way to Seattle, from which he could take passage to Valdez in the Santa Ana. [4]

The Norton Bay area had been withdrawn from settlement on June 30, 1903, pending an investigation to determine its suitability for forest reserve purposes. [5] The area involved was the southeastern portion of the Seward Peninsula, covering Norton Bay, Norton Sound, Golovnin Bay, and extending inland approximately fifty miles. This encompassed an area of 3,497,611 acres. The area is of mixed topography, with the Darby Mountains reaching elevations up to 3,000 feet. The many stream valleys are swampy and filled with a great deal of detrital material. There are poorly drained sloughs, numerous ponds and swamps, and, in addition, there are areas of high land and tundra.

The trees were restricted in area, poor in quality, and limited to a single species, white spruce. The timber bodies existed in the lower stretches of the Koytuk and Tubutulik rivers, in the meanders of the streams, and on the better-drained slopes. The trees were of almost equal height and diameter throughout, with slim, tapering outlines and short, scraggy limbs reaching nearly to the ground. The crowns were light, the rapid taper giving them strength to withstand winter winds. Hence, there were relatively few windfalls. In addition, a few stands of cottonwood, some reaching heights of sixty feet and diameters of eighteen inches, were found east of the Darby Mountains. The gross volume of spruce he estimated at 1,500 board feet per acre. Allowing for decay, this gave 900 feet per acre of spruce over eight inches in diameter. The total volume for the area he estimated at 30,127,000 board feet of commercial forest and 1,071,508 cords of wood.

|

| The waterfront at Nome. (University of Washington Library) |

There had been no lumbering in the area of the proposed reserve, and the only sawmill on the Seward Peninsula was at Council City. The mill had cut 30,000 to 50,000 board feet per year from 1902 to 1904, for local mining purposes and house logs. Logging was done by horse during the winter months when miners were idle. Although the logging operations were near the border of the proposed reserve, Langille thought that completion of a railroad in the area would make "outside" lumber in a position to compete favorably with that locally produced.

Langille realized that there was grave danger of fires in the area:

While there is a general absence of the usual forest litter, and the trees are not close, there is a period in the early summer of each year when the prevailing north winds dry the surface of the tundra and forest mosses to such an extent that they readily ignite, and once caught, fire spreads rapidly, generating sufficient head to take hold of the resinous bark, the thin sap trees being easily killed. Where burned, every living thing, even to the heavy sphagnum moss was killed, the moss being succeeded by a scattering growth of grass, one variety, similar to the western bunch grass, much liked by the pack animal, in places the blueberry bushes (V. uliginosum), then loaded with fruit, were renewing themselves as were the willows and dwarf birches: but not a single spruce seedling was seen in the areas burned four years before. [6]

A further danger in fire was the slowness of reproduction. The trees were not prolific cone barers, and many of those cones that did develop were immature. In addition, small seedlings were often killed by the browsing of the Arctic hare.

In considering whether there should be a forest reserve made from the area, Langille weighed the various factors and recommended against it. Mining, he wrote, was the only occupation that would ever attract a population to this cold, inhospitable area or create a demand for timber. Placer mining locations would, under existing laws, absorb most of the timber along the streams, in gulches, and ravines. On the other hand, if no mining development occurred, the forest would not be destroyed. On these grounds, therefore, Langille recommended that the Norton Bay Forest Reserve not be created. [7] The area remained withdrawn until 1907 and then was restored to the public domain.

|

| Logging along the line of the Alaska Central Railroad, 1905. (University of Washington Library) |

Boundary Work: The Kenai

Peninsula, 1904

Langille made an examination of the Prince William Sound area during September of 1904. He traveled from Valdez to Seward on the steam launch Annie in late September and made a short trip to Kenai Lake, returning October 7. October was spent in examination of the Kenai Peninsula. Purchasing a twenty-foot dory at Kenai Lake, he floated down the river. From Kenai he proceeded to Seldovia, hired a native, Alsenti Roman, as guide and packer, and traveled to the head of Coal Bay by boat, thence overland to Tusttumena Lake and back. He then went by boat from Seldovia to Resurrection Bay, arriving at Seward on the Dove on November 27, 1904. Later he made a trip up the Resurrection River to investigate homesite locations. [7]

The Kenai Peninsula at the time was just beginning a twenty-year boom period involving land, resources, and railroad building. In 1903 Seattle capitalists had formed the Alaska Central Railroad Company with plans to build inland across the peninsula and then north to tap the Matanuska River coalfields and eventually to reach the Yukon. It was one of several such projects to reach interior Alaska by rail from the coast. Like most of the others, its promoters were high in optimism and low in capital. In the wake of the railroad, there had come a group of mineral and land speculators who hoped to gain from the railroad venture. In addition, the Kenai area had become famous for its population of the larger carnivores and herbivores of the North American continent; members of the Boone and Crockett Club and similar sportsmen's groups came to shoot bear, Dall sheep, caribou, and moose. The permanent human population was sparse—200 at Seward, mostly connected with the railroad; 200 at Kenai; 100 at Hope; and a scattering of smaller settlements inland and fishing villages along the coast—but it was a time of great expectations, with a boom-town atmosphere at Seward.

On the peninsula Langille found a region of transition between the coastal type of forest and that of the inland area. The topography was divided between rugged mountains on the east, heavily glaciated, and a central and western plateau, poorly drained and with a network of streams, marshes, and lakes. Here were forests of mountain hemlock, white spruce, birch, aspen, and cottonwood, with some Sitka spruce and western hemlock near the coast. He found the forests bordering Prince William Sound to be of poor quality. At Port Wells he found a woodland type of forest that would be suitable for railroad ties but not for sawtimber. West of Kings Bay the timber improved. In Resurrection Bay there was an overly mature stand of spruce; the best stands along the railroad line were being cut rapidly for railroad purposes. Inland he found evidence of early forest destroyed by fire before the Russian occupancy. There the swamp had steadily encroached on what had formerly been forestland. Reproduction in the forests on the coast was good, though the new trees were not so clear of limb or free from defect as the old had been. In the interior and the mountains, on the other hand, he found the reproduction of conifers after fires "almost hopeless." There were very few spruce seedlings in the burns; reproduction consisted of deciduous shrubs and trees. [8]

Fire was an ever-present menace. As in the Norton Sound area, the forests were particularly susceptible to fires, and on the Kenai Peninsula they had taken their toll. Fires were prevalent for a number of reasons. One large fire had been set to get rid of mosquitos. The timber was destroyed, but the mosquitos remained. Some fires, set to free the land of dry grass, had spread into the forest. The railroad was a particular threat. In cutting ties and timber, wood crews left a great deal of slash, and the locomotives were wood-burning engines without spark arresters. [9]

Much of the lumber used in the area was imported from Puget Sound. Local wood was consumed as firewood. At Homer, a Philadelphia coal company had established a dock and facilities, although the quality of the coal was poor. Two sawmills had been established at and near Hope—one of 10,000 feet capacity per day, the other cutting 20,000. They had evidently been established in the hope of profiting when the railroad reached the area. The Alaska Central Railroad had in 1904 completed eleven and one-half miles of track, established a sawmill and a cable logging operation, and had cut about 13,000 feet per day, with a great deal of waste in the milling. Most of the timber was cut from land claimed by homesteaders, over the strong objection of the claimants. Their protests, however, were to no avail. The chief engineer and manager of the Alaska Central Railroad said he had been informed by the register of the General Land Office that he could cut on any location. The U.S. commissioner had told the claimants that there was no legal resource. A large number of the entries had been made for the timber alone, Langille observed, with the intention of holding up the railroad. [10]

Much of the land on the Kenai had been alienated under various land laws. The Alaska Central Railroad had a right-of-way franchise, but it had difficulty building the required amount of track each year to keep its franchise. It also had permission to take timber from the public domain to build bridges, trestles, and to make ties. At the Land Office the practice was to record homestead and mineral locations, even though the descriptions were incomplete. Langille listed 32 homestead entries, 32 coal land entries, 340 gold placers, 80 quartz mines, and 240 placer oil claims. However, no assessment work had been done on the oil claims. Groups of twelve to twenty men would associate to file on claims, let them lapse, and then refile under a new name, having no oil rigs or developments of any kind. The Alaska Colonization and Development Company had been organized to establish a Finnish colony on Coal Bay, acquiring the land by use of soldiers' additional homestead scrip. Langille condemned the venture as purely speculative. No paying gold prospects had been found, and Langille reported abandoned workings and unused hydraulic outfits. [11]

Big game, Langille noted, was an important resource of the Kenai Peninsula. The moose range was in the white spruce area near Coal Bay, that of the few remaining caribou in the same area, sheep were in the Sheep Range, and bear were scattered throughout. According to Langille, the settlers in the area killed little game, but Indians were wanton killers and visiting trophy hunters were wasteful. The latter stayed for a short time, killed as many good heads as they saw, and then took out the best. Traders also hired Indians to kill trophy-sized heads for sale to sportsmen. Langille recommended a stricter permit system, with all game bagged reported, permits recorded, and licensed guides to prevent abuse of the game laws. Settlers, he reported, believed that a bounty on wolves would help the game to survive. "The game of the region," Langille wrote, "should be a source of revenue to the people and of pleasure and sport to the outsiders who wish to hunt, and there should be some meeting place where the game can be conserved, clashing interests harmonized and trophy hunting permitted." [12]

Public sentiment on a forest reserve in the area varied. "Old-timers" feared restrictions on their frontier privileges, but they recognized the need for timber conservation and prevention of fire. Of the railroad followers, some were transients but others who lived in the immediate area were interested solely in developments that offered immediate profit. They opposed a reserve. A few people recognized the importance of the forestry movement, but most were indifferent. [13]

With many qualifications, Langille recommended creation of a reserve encompassing most of the Kenai Peninsula. Although there were no large settlements in the area and the timber was not of high quality as compared with that in the coastal area, he thought that the needs of the future, plus the necessity of protecting the area from fire, justified its creation. He recommended that its boundaries run from Passage Canal to Prince William Sound, thence southwest to Cape Puget, thence west to Coal Inlet, and north to Turnagain Arm, and across the portage to Passage Canal. He said a portion of the reserve should be made a game preserve, stating:

...it is further recommended that certain portions of the area included in the bounds of the recommended Kenai Forest Reserve be made game preserves, for perpetuating the game species of the region, one to be located so as to include the favored habitat and breeding ground of the mountain sheep (Ovis dalli kenaienses), another to include the year round haunts of the moose (Alce americanus gigas) and the range of the few remaining caribou. For the first, I would respectfully suggest an area to include the headwaters of both branches of Sheep Creek Valley, extending ten miles in an easterly direction from the timber line at the east side of Sheep Creek Valley; for the second I would suggest an area 20 miles long by 13 miles wide, the center of its northern end about opposite the T spit, one mile south from the shore line of Kasiloff Lake, to include the Caribou Mountains. [14]

Langille's report is an important document from several points of view. First, in making one of the first recommendations that game preserves be established in the region, it is closely connected with the history of wildlife preservation in Alaska, particularly with establishment of the Kenai Moose Range. In this, as in his efforts to preserve the totem poles, Langille played a pioneering role.

A second matter, which came to be of major importance, was that of agricultural land. Langille doubted that the area would have agricultural possibilities. Writing to Pinchot in November 1904, he stated:

In my reports I shall hold these glacial valleys with a covering of alluvial sediment supporting a forest growth, forest lands, and not classify them as possible or actual agricultural lands, considering the possibility of anyone using them for farm lands or grazing purposes is so small as to preclude their possible classification in this way. [15]

Besides an uncertain climate and thin soil, there was no market for farm produce or any forseeable growth of such a market. Yet, the matter of land classification troubled Langille. In the established states and territories, he wrote Pinchot, there was a precedent, based on experience, for classifying agricultural land. But in the Kenai area, where no one had ever made a living by farming and the agricultural possibilities of the land, when cleared, were unknown, there was no precedent to follow. Who, in such circumstances, was to make the decision? Langille operated on the assumption that all well-forested lands were better for timber growing than for agriculture, but he recognized that the question of agricultural land in national forests would arise not only in the Kenai area but also in the Matanuska and the Susitna valleys: "I don't know where to begin to call timbered lands cultivable and should like to know who will settle the question finally."

Another question raised in the same letter, one that was to have repercussions for the future, was that of revenue. Langille asked what the policy of the government was in regard to making money. Should revenue cover only the cost of administration, or should it be based on the value of timber in the reserve? Should the value of the timberlands be based on the costs of their production and protection, or on the value of the timber as set by competitive bid? In an area of sparse volume per acre and a high cost for protection, the problems were far different from those in the wet forests of the south. [16]

Boundary Work, 1905: From Cook

Inlet to Circle

During the late fall and early winter of 1904-1905, Langille enthusiastically made plans for his winter trip from his headquarters in Seward. He wrote his reports on Norton Bay, Prince William Sound, and the Kenai Peninsula and mailed them to F. E. Olmsted, who at that time was chief of the Section of Reserve Boundaries. He sent specimens of plants, cones, and leaves to Chief of Dendrology George Sudworth. He straightened out his accounts with Chief of Records James B. Adams and wrote to Pinchot of his reflections on forestry in Alaska. The injured foot, which had given him trouble during the Kenai reconnaissance, had an opportunity to heal so that by November 30 he could write, "its in ability to do its work is but a faded memory." He secured the services of an old friend, James Watson, as a trail companion on the journey. During early winter he began to collect the equipment for the trip—tents, a sled, film, snowshoes, mapping equipment, and a .22 rifle which, he wrote to Adams, "though unusual in your accounts, is a most necessary part of a winter outfit, it being a large item in the sustenance of a winter trip." He had difficulty acquiring suitable dogs, writing, "The Tanana stampede has created a great demand and raised the price of good dogs out of reason, almost as bad as Dawson's palmy days, when I paid $300 for a yellow hound, but he was worth it then." [17]

Langille's winter campaign involved travel up the Matanuska River in advance of the railroad survey and timber speculators, exploration of the Susitna and the Talkeetna river valleys, and travel on to Fairbanks and Circle to look at the interior forests. Watson set out early in January, and Langille joined him at Kenai Lake on January 26. One incident illustrates the spirit of the place. Langille had purchased a quart of Hennessey brandy for trail emergencies. On the day he left, every saloonkeeper and storekeeper saw Langille to wish him farewell and each brought a parting gift, a quart of the finest brandy available. He departed with thirteen bottles. Langille and Watson were accompanied as far as Knik by two Indians who had been accused of murdering a white man in the Kuskokwim Valley and brought to Seward for trial. No evidence had been found against them, so the deputy marshal asked Langille to take them as far as Knik in exchange for their assistance on the trail.

Langille and Watson explored the Cook Inlet area for a time, then traveled up the Matanuska Valley and down the Tazlina River to Copper Center, traveling under excellent trail conditions. From Copper Center Langille mailed film to the Forest Service in Washington and samples of coal and fossils to Alfred Brooks of the Geological Survey. They then traveled up the Gakona and down the Delta and Tanana rivers to Fairbanks, which they reached on April 14, and from there made the trip to Circle. [18]

The Cook Inlet area was geographically and topographically an extension of the area Langille had examined on the Kenai Peninsula. Cook Inlet, Knik Arm, and Turnagain Arm are flanked on the eastern side by a spur of the Chugach Mountains. On the north shore of Turnagain Arm, the mountains approach closely to the water. Rounding Point Campbell, he found a limited amount of plateau land along the shore, narrowing as the head of Knik Arm is approached, until below the Knik River the Chugach Mountains rise abruptly from the water's edge. The Knik River, in its lower reaches, is a narrow glacial floodplain, devoid of timber or even soil. The Matanuska River, with sources in both the Chugach and the Talkeetna mountains, broadens in its lower stretches, varying from seven to eight miles wide further downstream. The valley is of uneven surface, with traverse tributary streams and valleys, and has a gravel and sandy surface soil that assumes a loamy character near the foot of the mountains. Climatically, it is the most favored section of the Cook Inlet area, with warmer and drier winter seasons than are found in other parts of the valley. From this standpoint, Langille regarded it as the area best suited for agricultural purposes of any part of Alaska.

The area was virtually uninhabited in the winter of 1905. The only settlements were a few small Indian villages and the trading post at Knik, with a population of four white men. George Palmer, the trader at Knik, purchased skins from the Indians and also grew a garden, which, Langille observed, demonstrated the agricultural possibilities of the area. Unlike those of the Kenai Peninsula, the Indians were not wanton slaughterers of game, living instead mostly on rabbits. Langille feared, however, that the coming of the railroad would encourage market hunting and debauch the Indians.

The timber in the Cook Inlet area was of varying quality and quantity. On the north shore of Turnagain Arm were excellent stands of black hemlock and spruce. These were on or near the railroad right-of-way, however, and Langille feared that "indiscriminate cutting" by the railroad threatened the existence of the forest. There was, he wrote, immediate need to protect this forest in order that the mining interests might have lumber. Beyond Point Campbell the timber deteriorated. Both sides of Knik Arm were devoid of commercial forests, and there was a large amount of fire damage on the eastern side. In the vicinity of Knik Station, there was a 2,000-acre stand of pure birch containing 1.5 million board feet. The rest of the forest in the area consisted of typical mixed inland stands of white spruce, black spruce, birch, and aspen, not suitable for sawtimber. Stands in the Matanuska Valley were essentially of the same type, but with some good growth of cottonwood on the river bars. There had been extensive fire damage, both recently and in the remote past. In view of the need for fire protection, Langille suggested cutting or burning fire lines around the better tracts to protect them.

In 1905 there were few alienated lands except for the coal land locations on the Matanuska and its tributaries. The coal locations covered a large part of the western side of the main valley, especially on Granite, Moose, King, and Chickaloon creeks. The claims, Langille reported, were of questionable legality, having been recorded "by and without power of attorney," and the locations "lapped and overlapped on the ground and the recorded descriptions are so indefinite that it is impossible to determine the located area until surveys and amended location have been made." [19]

In the Susitna and the Yentna valleys, Langille found swampy floors having black spruce; the higher ground had white spruce and birch. The forests were of the woodland type, with the best stands carrying 1,000 to 2,000 board feet of spruce and 300 to 500 board feet of birch to the acre. Reproduction, he reported, was slow, with development of willow, alder, and birch before the spruce reproduced itself. [20]

Near Fairbanks Langille visited the lumber camps on the upper Chena, from which 10 million board feet had been cut in recent years to supply the needs of the city. There were at the time eight sawmills in Fairbanks, cutting from 5,000 to 20,000 board feet each day. Many homestead locations had been made for speculative purposes on the timbered land. Finding a high fire hazard and slowly growing timber, Langille regarded restocking burned areas as hopeless. On the question of reserves, he found opposition to any extension of the system into the interior. He hoped other methods than the reserve system could be used to protect the forests. [21]

|

| Wood cut along river banks in the interior fueled the steamboats during the gold rush era. The Prospector takes on a load on the Stewart River in Yukon Territory. (University of Washington Library) |

The Forests of the Interior,

1905-1911

The problems of Alaska's interior forests, with their high vulnerability to fire and the failure of the government to establish a sale or management policy, concerned the Forest Service continually for many years. F. E. Olmsted, in his 1906 report on the Alexander Archipelago, described the forests of the interior as being scattered in strips along the streams and promiscuously over the hills and mountains. The timber was small and scrubby but of great local value in connection with the mining industry. The interior was so large and so little known, however, that it would be impossible to establish reserves without including great areas that should, from the timber-producing viewpoint, be left outside. The innumerable mineral locations would create chaos in reserve administration.

Olmsted compared the American and Canadian systems of handling the boreal forest. In Canada the timber was sold for revenue at a minimum cost of $2 per thousand, a figure based on the assumption that the average life of a placer district is from five to fifty years and that it would be foolish to provide for a future supply of timber when the area would later be abandoned. Assuming that the locality would be abandoned, Olmsted wrote, this policy made sense. On the other hand, in the United States the General Land Office had the same policy in the interior that it had in southeastern Alaska; namely, that of allowing cutting without supervision and settling at twenty cents per thousand on the basis of innocent trespass. Olmsted believed it was foolish of the government virtually to give away its timber, particularly in an area where common lumber sold at $50 to $70 per thousand and finished lumber at $100. It was also foolish to be unable to sell the timber without making a trespass case out of the transaction. Olmsted recommended that the secretary of the interior appraise the timber of the Tanana and Yukon watersheds, set one price for the district, and call for bids, thus ending the "innocent trespass" fiction. He assumed that such power could be legally delegated to the local Land Office agents. [22]

A large number of scientific reports during this period also gave the Forest Service a better evaluation of the interior forests. These included reports by members of the U.S. Geological Survey, such as Alfred Brooks, Fred Moffitt, W C. Mendenhall, and E. C. Barnard; Wilfred Osgood of the U.S. Biological Survey; Joseph Herron of the War Department; and Judge James Wickersham. One report, that of E. C. Barnard of the Geological Survey, on the forest conditions in the Forty-mile Quadrangle, was made at the request of the Division of Forestry, which had under consideration a forest reserve there. These reports gave the Forest Service a better knowledge of the forest conditions in the interior and aided it in planning for future reserves and recommendations for forest policy. [23]

|

| Royal S. Kellogg of the Forest Service and A.S. Hitchcock of the Bureau of Plant Industry, on the trail between Rampart and Hot Springs in the interior. Kellogg's bulletin, The Forests of Alaska (1910) was the first Forest Service publication about the territory. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Royal S. Kellogg, in preparation for his monograph on the forests of Alaska, examined the forests of the interior in 1909 and reported them to be of the woodland type, covering about 80 million acres, of which probably half had timber of a size suitable for cordwood or sawlogs. The better stands, he reported, might carry twenty cords per acre of birch and aspen, or several thousand feet of sawtimber. The major use of timber near Fairbanks was for fuel, with an annual consumption of 15,000 to 20,000 cords. Steamboats on the Tanana and the Yukon also consumed much fuel. Fairbanks at that time had three sawmills, two with a capacity of 20,000 feet per day and one smaller. They were supplied by loggers who did their cutting on the Chena River, seventy-five miles above Fairbanks, and floated the logs down. In the interior there were mills at Council, Rampart, and on the Copper and the Susitna rivers, but Kellogg estimated that the total cut of saw-timber in the interior did not exceed 4 million board feet per year. The Land Office, by 1909, had raised its price on stumpage to $1 for sawtimber and twenty-five cents per cord for fuelwood.

Fire was a major hazard. As Kellogg wrote, "It probably would not be far from the truth to say that in the Fairbanks district ten times as much timber has been killed by fire as has been cut for either fuel or timber." Fire was caused by miners and hunters leaving campfires or mosquito smudges burning, by miners clearing land so they could follow the rock outcrops, and by others who deliberately set fires to secure dry timber. All of this loss was aided by the dry hot summers and by trees particularly susceptible to fire. The greatest need in the interior, Kellogg wrote, was for some system of fire protection. [24]

During the early fall and winter of 1903-1904, Langille had pondered the problems of forest administration and protection in the inland forests. On the basis of his own observations and experience, he later presented Pinchot with a provocative plan for the management of the Alaskan forests, adapting the law to Alaskan conditions. The letter deserves to be reproduced in its entirety. It summarizes the dilemma of the Alaskan resource manager in reconciling the need for conservation with the necessity of development. His plan for the forests of Alaska foreshadowed those developed later by Harold Ickes and the Bureau of Land Management.

Seward, Alaska, Jan. 10, 1905

Chief Forester

Bureau of Forestry

Washington, D.C.Dear Sir:

In a recent letter I intimated sending to you my reasons for asking the setting aside of all forest lands of Southeast Alaska as a forest reserve. I will even go farther now and say that all the forest lands of Alaska if not set aside as forest reserves, should at least be placed under the control and care of foresters, and the cutting carried on under their supervision, with such regulations as the different districts with their varying conditions demand.

It is difficult for one not acquainted with the forests of this region to comprehend their generally impoverished condition and the small amount merchantable timber that really exists in a territory so generally forested as this is. In moving to the north and west the study of the forest always results in favor of those previously seen, there being a constant decadence in size and quality, but still of relative value to the community where it exists and needs the same attention. Observations on the Kenai Peninsula this fall, coupled with previous experience on the Yukon, brings to mind a realization of the really small amount of saw timber which exists away from the coast and this subject to fire which is generally fatal to the thin barked white spruce whose slow reproduction—in places almost hopeless—with the slow growth of the trees after they do start, puts the time that they will attain a size suitable for use so far in the future that it makes a forester's arguments for forest protection seem farcical to the layman with utilitarian tendencies who sees only the need of the hour. It is these conditions of slow reproduction and growth which emphasizes the necessity of cutting timber under regulations and demands the protection of the living trees whose existence represents so many years of time and though small are invaluable to the people where every new resource is a new demand far timber and at the same time an added menace to the living forest.

The existing forest reserve law does not exactly meet the requirements of Alaska. It is too restricting and in a measure unjust to so new a country to include in a forest reserve an entire region with its latent possibilities so little developed or understood which at the same time is so much in need of forest protection to maintain its forests.

I would propose a measure placing every foot of timber in Alaska under government control and provide for its disposition and care under forest reserve regulations, without withdrawing the land from settlement, the one drawback to the present reserve law. The Alaska Code, Carters Annotated Alaska Codes, Sec. 11 P.460 provides: "That the Secretary of the Interior under such rules and regulations as he may prescribe may come to appraise the timber or any part thereof upon public lands in the District of Alaska and may from time to time sell so much as he may deem proper for not less than the appraised value thereof, in such quantities to each purchaser as he shall prescribe to be used in the District of Alaska but not for export therefrom."

This law makes no provision for cutting under regulations nor for the classification of the lands to segregate the agricultural areas as would be necessary under a new measure nor does it provide for the administration of the forest lands in any specific manner.

It strikes me that the withdrawal of large areas of wild land with no development to demonstrate its possibilities, especially in this region with its future all before it, there is a weakening of the reserve policy if reserves are created, administration provided for and, later it is found necessary to reopen to settlement any part of them, whereas my idea would prepare for this and at the same time protect the forests for the future settler and care for those which would surround him.

I would be pleased to have an expression of your view on this matter and if you thought it worthy of consideration, the earlier it could be brought about the better it would be for all concerned.

The time for a sentimental consideration of the time honored privileges of the pioneer has passed, the conditions which have brought about a relaxation of law in his favor are no more. Civilization in Alaska anyway, follows too closely in his footsteps with an element who abuse every right and privilege ever granted in his name without them deriving any of the benefits and he should no longer be considered a factor in the enactment of the laws for frontier communities or regulations under such laws. [25]

The Chugach National Forest,

1907: Initial Proclamation

In accordance with Pinchot's instruction, W A. Langille made an examination of the Prince William Sound area in 1904 and made recommendations to the chief of reserve boundaries in January 1905. He stated in an accompanying letter that the report was incomplete and was only intended to give an idea of conditions there. [26] A year later he discussed the area with F. E. Olmsted when the latter came to Alaska on his inspection trip. Olmsted was indifferent about the proposed reserve at the time. There were, he said, no strong reasons either for or against creating the reserve. [27] In 1907, however, there came a flurry of activity within the Forest Service regarding new reserves, partly because of a movement within Congress to curb the president's power to create reserves by executive proclamation. The Alaska reserves came up for consideration, and by March the Forest Service had decided to create new reserves both in southeastern Alaska and in the Prince William Sound area.

The proposal met with strong opposition from Richard Ballinger, commissioner of the General Land Office. In a meeting with Forest Service officers, he discussed the reserves, succeeded in cutting down on the size of that in the Panhandle, and objected strongly to that in Prince William Sound. [28] He quoted Langille's report to the effect that there was relatively little sawtimber in the Prince William Sound district in proportion to its area and that there was no danger that the forest would fail to perpetuate itself. Ballinger expounded at length on his belief that the reserve would nullify most of the laws used to acquire land in the area and would render the existing laws more difficult to enforce. He quoted Langille's statement, in his 1905 report, that creation of a reserve might be premature and inconsistent with the sparse population and lack of economic development in the area. He referred to Langille's assertion that it would be better to regulate the forest lands in Alaska by forest officers, without withdrawing the area from settlement "when the resources are entirely undeveloped and might be retarded by reservation." [29]

Despite Ballinger's objections, the Chugach National Forest was proclaimed on July 23, 1907; it extended from the Copper River on the east to the borders of the Kenai Peninsula on the west and inland to the Chugach Mountains. [30]

Langille received news of the proclamation at his headquarters in Ketchikan. He made plans to visit the area but had his usual difficulties with transportation. The Alaska Coast Company steamers did not stop in Ketchikan, so he had to arrange for transportation to Juneau. He left Ketchikan on August 7, caught the Portland at Juneau a week later and arrived at Valdez the morning of August 20. There he spent a week interviewing people and explaining forest policy. He caught the Portland on its return from Kodiak on August 28, reached Juneau on September 2, and Ketchikan on September 6.

The Chugach National Forest, comprising 4,960,000 acres, consisted of the narrow coastal plain and extensions back from the coast to the crest of the Chugach Mountains. It was located on Prince William Sound, a magnificent body of water, protected from ocean swells and storms by large offshore islands—Montague, Hinchinbrook, Hawkins, Latouche, and many smaller ones. The largest river then marking the eastern border of the reserve was the Copper, a glacial stream with a wide delta. The Lowe River, at the head of the Valdez Arm, was next in size. The principal mountain range was the Chugach, rough and rugged, with peaks up to 13,000 feet and many glaciers. There was but little level land, and this mainly on the flood plains of glaciers. The climate was one of excessive rain in the summer and fall and heavy snow in the winter; in the winter of 1906-1907, Valdez reported twelve feet of snow on the level.

Valdez was the most important town. Located on an excellent harbor, it had been the scene of a major mining rush in 1898-1899, when thousands of men crossed the Valdez Glacier in search of gold in the interior. In 1907 it had a population of 500 to 700. It was the coastal terminus of the all-American mail route to the interior, the connecting point of the U.S. cable with the telegraph lines that kept interior Alaska in touch with the world. Valdez was the supply point for fishermen and for prospectors working toward the headwaters of the Copper River.

There were a few other settlements. Cordova had experienced a railroad boom a few years before but had declined in population until, in 1907, it had only a half-dozen inhabitants. Ellamar, a post office twenty-eight miles from Valdez, had a few miners in residence. Latouche and Reynolds were small towns on Latouche Island. Orca, near Cordova, was a cannery site, inhabited only in the summer. There was, in addition, Langille reported, a floating population of 500 to 1,000 miners and prospectors. [31]

Langille went to Valdez during a railroad boom. In this area, as in Seward, projects were under way to reach the interior by railroad. Also, just outside the eastern edge of the reserve, two railroads, one controlled by the Bruner interests and the other by the Guggenheims, were planned to reach the interior by way of Copper River from Katalla. The Valdez and Yukon Railroad had an established right-of-way from Valdez about twenty miles inland and had completed about five miles of grading by 1907. Just prior to Langille's visit in that year, however, another promoter entered the race to the interior. H. D. Reynolds, of the Reynolds-Alaska Development Company (a company backed by Boston capital and with Governor Wilford B. Hoggatt as one of the directors), announced his plan in August to build an electric railroad to the interior. He asked the town for moral and financial support. The Alaska Home Railway Company was formed, stock issued, and construction begun an a narrow-gauge railway with the intention of reaching the summit of the Chugach Mountains before winter. The H. D. Reynolds interests also purchased copper properties and formed subsidiary companies to control virtually every business in town, including the sawmill and roadhouses. Local men whose businesses were absorbed were generally put in charge of their former concerns if they purchased sufficient stock. With all these fireworks, Reynolds lacked a right-of-way across the newly created national forest. Langille gave him tentative permission to go ahead on construction of the line, pending a formal application.

The chief economic activity of the Prince William Sound area was copper mining. Four mines were active in 1907 at Landlocked Bay, Ellamar, and Latouche Island. The Reynolds interests also had developed properties at Landlocked Bay, Boulder Bay, and Latouche Island. There were, in addition, many mineral locations "made for all sorts of purposes." Fishing was carried an principally near Orca, where there was a cannery, and, prior to 1907, there had been fox farming on some of the islands. Transportation, as in the Alexander Archipelago, was mostly by boat. The Northwestern Steamship Company, owned by the Guggenheims, carried mail to Katalla, Valdez, and Seward. The Alaska Coast Company's steamers, owned by the Reynolds interests, carried mail to the same ports and also to Seldovia and Kodiak. Local transportation was by small boat, costing far charter $60 per day for short trips and $45 per day for charters of ten days, everything furnished, or $15 to $20 per day if the charter party furnished everything. There was relatively little alienated land in the forest, since most of this land had been excluded by the proclamation creating it. Langille reported, however, that there were some homestead entries evidently designed to control the timber sought by the railroads.

The timber in the area was largely Sitka spruce, black spruce, and black hemlock. Good bodies of timber were infrequent and largely confined to the settled bays of the islands. But, while not abundant or of the best quality, the timber was needed to supply the mines. There was a dense undergrowth, as was typical of the coastal forests. Reproduction was spontaneous; forest fires were unknown. Though good sawtimber was limited, there was an abundance of material for ties, piling, and mining timbers.

Only a limited amount of lumbering was being carried on in 1907. Most of the lumber used was imported from Puget Sound. The Copper River Lumber Company operated a mill in Valdez and also sold Puget Sound lumber. The mill was a fairly modern circular-saw outfit, with combination planer, edger, and cutoff saw, and a capacity of 14,000 board feet per day. There was an inactive mill near a cannery on Galena Bay, and a permit was pending to set up a mill on Latouche Island to supply local mining needs. Handlogging was the common practice. The Copper River Lumber Company owned the only steam logger on the sound; it operated from a scow and moved from place to place. The loggers received $7.50 per thousand for logs at the place of cutting, ready for rafting; towage was about $3.50 per thousand. Spruce was the sawtimber most sought; hemlock was little used. In scaling logs and observing the mill operation, Langille noticed that the timber was free from heart shake, unlike that further to the south, and that the spruce, though small, was sound.

Langille found that creation of the reserve had not brought about much antagonism in Valdez. Mining interests regarded control of cutting by the government as a right and preferred the businesslike handling of sales by the Forest Service to that of the Land Office. There was an undercurrent of hostile feeling among the mining men on the Sound, based on a rumor that the reserve was created at the request of the Guggenheim interests and that the timber would not be sold or disposed of until the big operators could use it. Langille made a "complete and emphatic" denial of this rumor and secured the miners' support. H. D. Reynolds also supported the reserve idea.

Langille's recommendations regarding the reserve reflect the dominant political and social tenets held by the Roosevelt conservationists. Langille claimed that a national forest was justified in "the surveillance the Forest Service will maintain over the location and usage of its public lands by vested interests, who would exploit them for their own selfish interests to the exclusion of the individual. While it is true," he wrote, "[that] the mineral resources of such a region cannot be brought to the producing stage by the individual, he still has his rights and should be encouraged in his efforts; no less should capital in its efforts at development be protected from unscrupulous individuals who seek by every known method of extortion to obstruct and hinder every enterprise undertaken." Roosevelt himself could not have expounded more eloquently the tenets of his "Square Deal."

Langille believed that Latouche and Knight islands might be excluded from the reserve in view of their mineral locations. He anticipated that the railroad boom would lead to large sales of sawtimber, ties, and piling. In such cases, the settlements for trespass should be on the basis of those then charged in the Alexander Archipelago; later, when the forest was organized, prices should be based on accessibility and local needs. He recommended that headquarters for the forest be established in Valdez, which had cable connections with Ketchikan, and that a powerboat be purchased for transportation. [32]

With characteristic energy, Langille settled timber trespass cases in the area before he left. He made a settlement with the Valdez and Yukon Railroad Company for 10,000 feet cut in trespass, with the Valdez Dock Company for 3,170 feet of piling, and with the Copper River Lumber Company for 560,290 feet. In addition, he made sales amounting to 403,000 feet of sawtimber. [33]

Additions and Eliminations in

the Chugach, 1907-09

Shortly after the initial proclamation of the Chugach, some areas were eliminated in the vicinity of Valdez. Made at the request of business interests, they included an area one mile back from tidewater on Valdez Arm, amounting in all to 83,000 acres, on which mineral locations had already been made. [34]

|

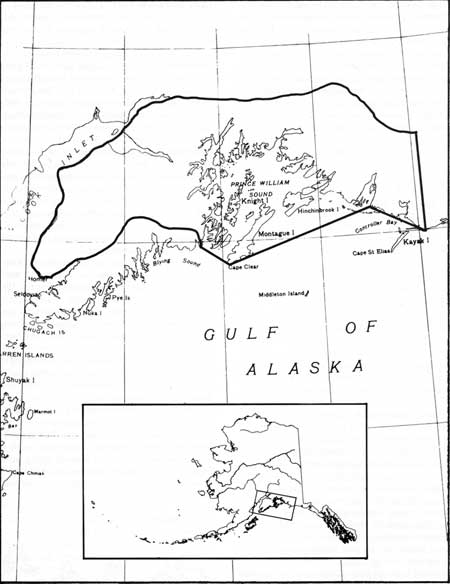

| IV. Chugach National Forest boundaries in 1909. |

In his 1907 report on the Chugach National Forest, Langille also recommended that additional areas be withdrawn from entry and added to the forest: the north shore of Turnagain Arm; Knik Arm; and up the Knik River to the junction with the Chugach. His reason was wasteful cutting by the Alaska Central Railroad, notably in the Rainbow, Indian, Bird and Glacier creek areas. Excellent stands of spruce and black mountain hemlock were located in these areas. The Alaska Central Railroad, between 1905 and 1907, had set up two sawmills and cut 3 million feet of timber, which had been left in the woods to decay. The railroad itself would need timber for construction purposes, and it was also the most available sawtimber in Alaska for the coal mines to be developed on the Matanuska River. Failing other means of preventing such "wanton waste" of timber, Langille recommended addition of this area to the Chugach National Forest. [35]

In another change, President Roosevelt added the Afognak Fish Culture and Forest Reserve to the Chugach National Forest by executive order July 2, 1908. Afognak Island, however, remained under joint jurisdiction of the Forest Service and the U.S. Fish Commission, with the dominant use of the island being for fish culture. [36]

In 1909 Langille submitted to E. T. Allen, the district forester of District 6, further recommendations on the Cook Inlet area. He reported that since 1905 there had been little general development in the area except on the tributaries of the Yentna, where gold had been discovered. In consequence, there was some interest in steamboat transportation on the Yentna and the Susitna. He warned that the rush of prospectors for gold and the need of timber by coal miners made an additional threat to the forests. "This year is an opportune time," Langille advised, "to begin a system of forest production that will so far as possible save the live timber." He ended his report by writing:

This is a region vast, isolated, almost uninhabited, possessing a rigorous climate and meager forests, but it has latent possibilities, and although it may seem a far cry to their development and the interests of the intervening period unworthy with little hope of a sustaining income, the project is nevertheless a worthy one.

His recommendations for a Talkeetna National Forest included a 10,294,720-acre tract, including the valleys of the Talkeetna, Yentna, Susitna, and the Matanuska rivers from Cook Inlet to timberline along the divide. [37]

With the creation of the Chugach National Forest, Langille received additional help. A man named H. M. Conrad, a Forest Service employee from Wyoming, was sent to Valdez in January 1908. More important, Lage Wernstedt came to Ketchikan in 1908 and was stationed at Cordova. Wernstedt, a graduate of Yale University, had studied in Sweden where the forests resembled those in Alaska. He had great physical endurance, liked Alaska, and was a good physicist and mathematician, as well as a capable forester. He was also the bane of government inventory and property clerks because of carelessness with both personal and government property. His major duties in Cordova were to administer a large timber sale on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway, do boundary work, and make silvicultural reports. [38] In 1908 Wernstedt reported on a proposed addition to the Chugach National Forest along the coast between Copper River and Icy Bay. This area was one in which there had been a great deal of speculative interest. Langille had reported in 1904 that everything was staked well up the side of the range, wherever free from ice, including most of the forest area of the region. It was held as coal lands or placer oil claims, much of it not recorded but restaked from time to time to avoid paying recording fees. Recorded claims were renewed under new company names by the same individuals to avoid payment for assessment work. The recording was done by agents, operating under powers of attorney given them by individuals who never saw the land.

|

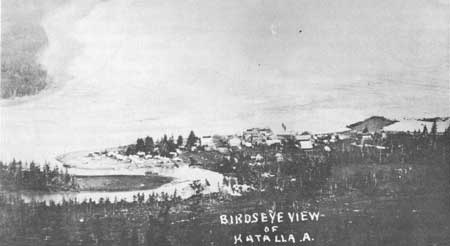

| Katalla, a center of mining speculation on the Chugach National Forest. |

Near Katalla, where some oil wells began to produce, timber was being cut on the oil claims and disposed of to the sawmill there. The situation had not changed by the time Wernstedt made his examination and wrote: "It is understood that irregularities have occurred in the location of a number of these claims. The claims, it is said, were staked for other interests than those of the claimants." [39]

Railroad speculation affected Katalla, as it did Valdez. In 1906 and 1907 Katalla had been chosen as the terminus for two rail lines, one backed by the Bruner interests, the other by the Guggenheim-Morgan interests. Both had projected rail lines to reach the Bering coalfields and inland. The Guggenheim interests shifted their activities to Cordova. The Bruner interests, after spending a fortune in building a breakwater that a storm destroyed, went out of business. By 1909 Katalla had lost its period of prosperity. [40]

Along the coastal strip, Wernstedt found good commercial forest made up of spruce and hemlock, the spruce growing lower in elevation than the hemlock. Trees three feet in diameter were not uncommon, and at Yakataga he found some six feet in diameter. He estimated volumes at from 15,000 to 25,000 board feet per acre, with better timber at Yakataga than Katalla, and at Katalla better than at Prince William Sound.

Cutting for the projected railroads had led to much waste. At Clear Creek and at Martin Creek, 2 million board feet had been cut in the expectation that Katalla would become a railroad terminus. When the bubble burst, the fallen trees were left in the woods to rot. Because of the commercial value of the timber and in order to eliminate wasteful cutting, Wernstedt recommended creation of an extension of the Chugach, to extend as far south as Cape Yakataga. [41]

Action on the proposed additions to the Chugach National Forest was delayed for some time, though E. T. Allen strongly urged that Langille's recommendations be followed. [42] Finally, in the closing days of Roosevelt's administration, the Chugach National Forest was enlarged by executive proclamation. The new area included most of the timbered area of the Kenai Peninsula, plus the Turnagain Arm and Knik areas. It also included an extension to the east along the coast to Cape Suckling, and thence north to the mountains. By Roosevelt's proclamation of February 23, 1909, the Chugach reached a total of 11,280,640 acres.

Ballinger and

Pinchot

The years of 1909 and 1910 were crucial in the history of the Alaskan forests. They were marked by the transition of power from Roosevelt to Taft, the affair involving Ballinger and Pinchot, and the replacement of Chief Forester Pinchot by Henry S. Graves. The crisis in conservation during the first year of Taft's administration has been variously evaluated by historians. Some, like John M. Blum, have dismissed it as sound and fury, signifying nothing. Others have treated the matter as one of profound political significance. [43] It is appropriate in this study to deal with the matter from the standpoint of resource management and forestry in Alaska. Seen from a regional rather than a national viewpoint, the affair marks a watershed in Alaskan conservation history.

The changing of the guard led to concerns about conservation policy. Conservation work had been carried on smoothly with Roosevelt as president, Pinchot as chief forester, and James Garfield as secretary of the interior. The two departments, Interior and Agriculture, had a working arrangement and cooperative agreements regarding examination of claims within national forests, forestry on Indian reservations, and the like. Pinchot became concerned over the possibility that Taft would fail to follow the Roosevelt-Pinchot policies. He became even more concerned when he learned that Garfield would be replaced by Ballinger as secretary under Taft. One result of this concern was an effort to secure the gains already made. Administrative withdrawals of ranger station sites were made to protect power site possibilities. In view of Ballinger's hostility to the creation of the Tongass and the Chugach national forests, it may be conjectured that additions to them in February 1909 were made to consolidate the position of the Forest Service in Alaska.

With the acquisition of Ballinger's papers by the University of Washington, historians have tried to get at the roots of his personality and ideology. The interpretation that emerges, and which is probably correct, pictures Ballinger as a self-made man. He came from humble beginnings, went west, and grew up with the country, becoming a successful lawyer, a reform mayor who cracked down on gambling and prostitution in Seattle, and a capable and efficient administrator. Though he enjoyed the company of men of power, position, and wealth, he was without personal political ambition. He was reticent, controlled, self-righteous, proud, and considered himself a good Republican in the Roosevelt tradition. He managed the Land Office with efficiency from the ousinessman's point of view, removing superannuated clerks and inefficient employees, replacing pens and ink with typewriters, simplifying forms for homestead applications, and reorganizing where necessary.

The Roosevelt tradition embraced elements other than business efficiency. In resource management, Ballinger's ideas represented reaction rather than progress. He believed in the traditional function of the Land Office—that it existed to get the public domain in to private hands. He was ignorant of resource problems and management and tended to misinform himself. In the Pacific Northwest's major struggle for fire control—which involved state, federal, and private cooperation—Ballinger actively opposed such cooperation. He believed in departmental autonomy and a chain-of-command administration, and he disliked what he considered to be Pinchot's empire-building and close association with Roosevelt. He had the distrust of the self-made westerner for the easterner of inherited wealth, and of the common-sense businessman for the expert. [44]

There are other aspects of Ballinger's environment and character that deserve further research. He was a Republican, but a Puget Sound Republican. Puget Sound was the center of opposition to Pinchot and to the Forest Service. Cornelius Hanford, John Wilson, William Humphrey, J. J. Donovan, E. W. Ross, and others were among the men with whom Pinchot and E. T. Allen had to battle in order to implement their programs. These doctrinaire opponents to the Forest Service were Ballinger's customary associates, and they undoubtedly told Ballinger what he wanted to believe. [45]

Historian James L. Penick has stressed economic colonialism as a factor in Ballinger's opposition to Pinchot. His thesis is that the Puget Sound area became frustrated at the invasion of eastern capital—the Hills, the Weyerhaeusers, and others, and at the draining of the West's wealth by the East. Ballinger emerged as a champion of the small local businessmen and capitalists who desired their own opportunities to expand. [46] Whether or not Penick's thesis is true, the fact should be noted that Puget Sound protests against economic colonialism did not extend to their own activities in regard to Alaska. Since the gold rush of 1898 (and even before), Puget Sound entrepreneurs had looked upon Alaska as an area for their own exploitation. Some of these have already been noted—the Rush and Brown group and the promoters of the Alaska Central Railroad—and others will appear on the scene. Ballinger knew these men as friends and colleagues, and he shared their views. Evidence of this affinity include his statements protesting creation of the Chugach and the Tongass national forests, his approval of the law that forbade export of Alaska timber (it would compete with that of Puget Sound), and his concern for speeding up patent for the Cunningham claimants.

As Ballinger came to office as secretary of the interior, a series of clashes with Pinchot arose. Some involved administrative matters and interdepartmental cooperation. One of significance was that of land claims within the national forest. Although the reserves were transferred to the Forest Service in 1905, land titles still remained within the jurisdiction of the General Land Office. The Forest Service wanted authority over titles so that mining claims could not be used to gain control of forest or grazing land. Pinchot and Secretary of the Interior E. A. Hitchcock had worked out an agreement whereby the Forest Service would investigate, report on, and make recommendations on claims within the national forest. This agreement was formalized in May 1905 and was the authority by which Langille worked in examining land claims. Ballinger objected to this arrangement, however, arguing that the Forest Service interfered with Land Office prerogatives and duplicated the work of his agency. A compromise formula was arranged whereby the Forest Service could investigate but could not recommend.

Other clashes involved Ballinger's desire for change in reclamation and irrigation policy, a cooperative arrangement between the Indian Bureau and the Forest Service regarding cutting practices and fire control on Indian lands, the "ranger school," a cooperative arrangement between the Forest Service and state universities for technical training of rangers on the off-season, and withdrawal of power sites in the West. Ballinger abrogated both cooperative arrangements on legal grounds. All of these matters led to a worsening relationship between Pinchot and Ballinger. Taft, a completely inept politician, lacked Roosevelt's skill in the management of differing men. The problem came to a head over the Cunningham claims in the Controller Bay area of Alaska. [47]

|

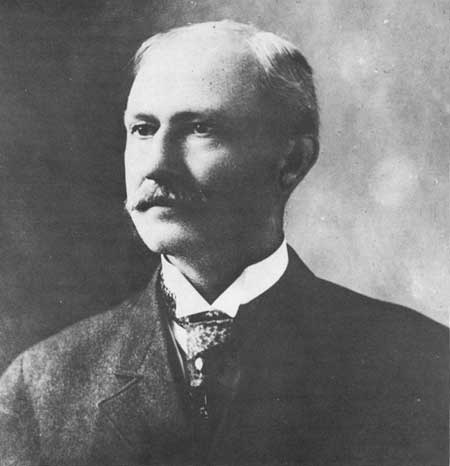

| Richard Achilles Ballinger, a Seattle lawyer here photographed in 1907 as commissioner of the General Land Office, became President Taft's Secretary of the Interior in 1909. Ballinger's clash with Pinchot over Alaskan issues marked a turning point in American conservation history. |

The Cunningham

Claims

As early as 1904, Langille noted that most of the Controller Bay area, from the coast back to the glaciers, was blanketed by coal and oil placer claims, many of questionable legality. Several groups of claims were located in the area tributary to Bering River, an area bounded by Bering Glacier, Martin Glacier, Martin River, and Bering Lake. At least 1,100 separate groups of claims were involved, most of them staked in the names of men who never saw them but gave power of attorney to some prospector or agent. The English Syndicate, Harling group, Chezum group, Hunt-Harriman group, and Green-Young group are among those that appear on the records.

The Cunningham claims were a group of thirty-three claims situated near the 144th meridian and inland from the coast about twenty-six miles. Of these, twenty-one were included within the Chugach National Forest under the 1909 addition. The claimants were businessmen, many from the state of Washington, for whom Idaho mine owner Clarence Cunningham had staked claims under power of attorney. The plan of the Cunningham interests was, in addition to working the claims, to take up sufficient timberland, as mining claims, to supply their construction timber and stulls and to utilize the waterpower of Bering Lake and Bering River. Plans were also made to acquire more timber by use of scrip. Access to the claims was by the Bering River and by a series of trails through a jungle of devilsclub and willow. Elevations on the claims ran from 200 up to 2,500 feet, and the terrain was dissected by steep-bank streams, including the Stillwater, Canyon Creek, and Trout Creek.

The claims had first been explored in 1903. Prospecting was done on some of the claims, a survey run, and a wagon road built. But no actual mining was carried on. In due time, the claimants paid $10 per acre for their parcels and applied at the Juneau branch of the General Land Office for entry of all thirty-three claims. All that remained was the clearlisting of the claims and issue of patents. [48]

Meanwhile, rumors of possible fraudulent practices in obtaining Alaska coal lands reached the General Land Office. In 1907, when Ballinger was commissioner of the General Land Office, he received conflicting reports on the claims from field agents. Horace Jones recommended a rigorous investigation on rumors that the claims were tending to the Guggenheims; H. K. Love said the claims were bona fide. Meanwhile, the claimants did sign an agreement with the Guggenheim-Morgan group, agreeing to consign a partial interest in the claims when they came to patent.

During Ballinger's period of private law practice, between his term as commissioner of the General Land Office and his appointment as secretary of the interior, he advised the claimants. A question remains as to whether he consulted with them as a friend or as a lawyer with clients. On becoming secretary of the interior, Ballinger requested the clearlisting of the Cunningham claims. Louis Glavis, the field officer of the General Land Office in Seattle, wished to delay clearlisting of the claims pending field examination in the summer of 1909. He became convinced that Ballinger and his successor as commissioner, Fred Dennett, were erecting a roadblock to his investigation. James Sheridan, another agent appointed to look into the Alaskan claims, supported this view.

Glavis's objections to clearlisting the claims rested on three major grounds: first, that the claims would be worked as a unit rather than as individual holdings; second, that the coal mine laws applicable were violated; and third, that the mining laws were being used to obtain timber. [49] In regard to the last matter, the administrative decision pertinent was Grand Canyon Railway v. Cameron, a case involving fraudulent claims on the rim of the Grand Canyon. The decision stated: "Lands belonging to the United States cannot be lawfully located or title thereto by patent legally acquired, under the mining laws, for purposes foreign to mining or the development of minerals." Pinchot had felt this decision to be of such importance that he had it printed in the Field Program of the Forest Service for 1908. [50]

The Forest Service became concerned with the Cunningham claims through a series of circumstances, accidents, and mishaps. In 1908, with the establishment of a regional system of administration, District Forester E. T. Allen initiated the practice of conferring with the chief of the Field Division of the General land Office for the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. This practice was necessary for the transfer of timber sales from Land Office jurisdiction to that of the Forest Service, as well as to keep the Forest Service informed on land claims within the boundaries of national forests. [51]

On July 13, 1909, a disturbed Louis Glavis met with Allen in Portland. Five days earlier Glavis had sent his superior, H. H. Schwartz, a letter stating the necessity for a field examination of the Cunningham claims before clearlisting them for a patent. The letter was referred to the wrong file and did not reach Schwartz until July 17. Meanwhile, Glavis received orders to proceed with the hearings. Allen asked Glavis for information on claims work within the national forest and became alarmed at his account. Allen's alarm stemmed, first, from the intimations of fraud, which tended to substantiate previous reports by Lage Wernstedt and W. A. Langille on speculative activities in the area. Second, the Land Office had failed to inform him of the pending hearings, an omission of established practice. Third, Glavis reported that the claimants were taking up four of the claims for timber rather than mineral values—a violation of the law. Allen realized that a field examination of the claims was necessary, with Forest Service participation to determine the truth of the allegations. He decided to write a letter to Pinchot, requesting a field examination, and he asked Glavis to send a supporting telegram to A. C. Shaw, the Forest Service law officer, to make certain that there was no misunderstanding.

Allen wrote the letter on Thursday, July 15. It could not have arrived in Washington before Saturday, and probably not until Monday, July 19. Glavis, meanwhile, waited until Friday, July 16, and then sent his telegram to Shaw. Therefore, the first word that the Forest Service in Washington received of the matter came from Glavis. The result was very much of a mix up. Shaw, much alarmed, requested the Land Office to hold off any further hearings and asked Allen for further information. Allen was out of the office on July 16, and George Cecil, acting district forester, knew nothing about the situation. The Land Office, meanwhile, was deeply alarmed and affronted. It appeared to the Land Office that Glavis's telegram was designed to initiate action by an appeal to another department. [52]

The misunderstanding was never cleared up. Glavis was removed from charge of the Alaska coal cases. His visit with Allen and the telegram to Shaw were among the charges on which Ballinger asked for his dismissal. Ballinger wrote:

I call attention to the fact that Glavis went in to conference with the office of the Forest Service in Portland, who are his subordinates, and wired Mr. Shaw, of the Forest Service in Washington, without authority from the Chief of the Special Agent Service, Mr. Schwartz. [53]

In a long letter to Pinchot, which deserves to be quoted in full, Allen explained the matter:

September 4, 1909

The Forester

Washington, D.C.Dear Sir:

The newspaper stories about the Cunningham Coal cases seem to agree pretty well on one point which I fear may be an injustice to Mr. Glavis. Certainly it will be if he fails to support his contentions. This is the statement which, if not originally made by the Forest Service, at least has not been challenged by it, that the first information received by it of the true and acute situation came from a personal telegram by Mr. Glavis to Mr. Shaw of July 16. It may easily be charged that such action by Glavis was both wrong and irregular and in itself showed questionable motives.

Mr. Glavis told me personally the whole story on July 13. It came about as the result of our discovery that some of the claims involved were in the Chugach National Forest. We discussed the best method of delaying the precipitate action which seemed imminent and agreed that I should notify you officially, while in the meantime he sent a telegram to Shaw to make sure there would be no misunderstanding. In short, my official notice to you was to be used as a means of securing delay and hence would probably have to be shown in its entirety to the Department of the Interior and require cautious wording. This was particularly true because Mr. Glavis requested protection against the very sort of compromising charge which has actually resulted—that he acted irregularly in an attempt to enlist the Forest Service against his superiors. The real truth is that as Chief of Field Division in charge of the cases, he gave their status upon the request of the District Forester, responsible for the Chugach National Forest, who demanded this information immediately [when] he found that the Forest was involved, and Glavis could not refuse to give it to him without official discourtesy.

I had no opportunity to write to you the following day, being obliged to attend a lumberman's meeting, but did so upon the 15th. I also added a personal letter to Mr. Shaw explaining Glavis request that we make it very clear how he came to give me the information.

In spite of all this, the public impression has been given that Glavis wired Mr. Shaw personally and that as a result, I was informed of the case and instructed to help him.

I think it should be made very plain that the way the whole thing come to us was through my taking it up with Glavis as a District Forester naturally would with the Chief of Field Division when he found that a case in a National Forest under his jurisdiction was soon coming to hearing and desired all possible knowledge as to how the Forest interest was being taken care of. Any other public impression is very unfair to Glavis under the circumstances and consequently weakens his position and ours.

Very truly yours,

E. T. Allen

District Forester

However, the matter was never clarified. In a letter dated September 4 to Associate Forester Overton Price, Allen explained that the position stated in his letter was the true one and tactically the strongest for the Forest Service. In view of the existing situation, however (Glavis had just presented his case to President Taft on September 3), Allen feared that it might be too late. If the record was to be called for, it might look like a frame-up. Allen asked Price to treat the letter to Pinchot as a personal letter and to decide for himself whether to put it in the record. Later, in a telegram to Pinchot dated September 13, he asked him to disregard the letter and to take it as a personal one, because Glavis had said that it would only complicate affairs. [54]

The failure to clarify the relationship of Allen's letter and Glavis's telegram was unfortunate from several points of view. It has led generations of historians to believe that Glavis behaved in an unorthodox or questionable fashion in telegraphing Shaw; that he acted, as Pinchot's biographer put it, "in a mood of desperation," rather than being a victim of the communications system. [55] The interests of the Forest Service in the affair were not made clear at the subsequent investigation. Though mentioned, they were lost in a mass of extraneous material, to the extent that the most recent account of the affair does not clarify the matter. [56]

Had E. T. Allen's testimony been called for, he would have been an ideal witness for the Pinchot forces. A westerner who strongly supported the Pinchot policies, he became secretary of the Western Forestry and Conservation Association in 1910. Allen was popular in the business community of the Northwest and could have effectively countered Ballinger's claims that the Forest Service hindered development in the West and in Alaska.

During the time that the Glavis misunderstanding developed, Fred Ames of the Portland office was in Alaska on his inspection trip. On July 29, 1909, he received a letter at Ketchikan from George Cecil, acting district forester, who wrote:

There is considerable evidence that the claimants in the above cases are not only trying to get valuable coal land fraudulently, but are attempting to secure in addition to the coal claims, timber land for the purpose of supplying timber to work their mines. Clarence Cunningham, in one of his reports to the stockholders, admits that four of the claims are more valuable for timber than coal, so the department has secured a continuance in the cases in order to investigate this more thoroughly.