|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 4

The Weigle Administration, 1911-1923

The Politics of National Conservation, 1911-1923

The years from 1910 to 1923 were crucial for the Forest Service. It was subjected to stronger attacks than in any previous period in its history, and its very existence was threatened. Much of the storm centered over Washington, but the regions were subjected to their own attacks—Alaska more than most.

When Gifford Pinchot was removed as chief forester in 1910, he was succeeded by Henry Solon Graves, dean of the Yale Forest School and Pinchot's close associate for many years. Graves had planned at first to return to his post as dean after a year of service. Events changed his mind, however. A strong sense of duty and the need for professional management of the national forests led him to continue in office for a decade. [1]

Graves, a graduate of Yale in 1892, had studied forestry abroad at the University of Munich. He had accompanied Pinchot on the National Academy of Science's tour of forest reserves in 1896 and, later the same year, worked as consulting forester for the Cleveland-Cliffs Iron Corporation in Michigan. He was assistant chief of the Bureau of Forestry under Pinchot from 1898 to 1900. With the establishment of Yale Forest School, he became its director and later dean.

Graves became an outstanding chief forester and was a worthy successor to Pinchot. He broadened the scope of Forest Service activity into the fields of research and recreation. He was able to maintain morale in the agency and did much to professionalize the regional and field forces by replacing many old-time foresters, whose education was in the "University of Hard Knocks," with academically trained men. He concentrated on internal affairs rather than publicity. At times he tended to underestimate the strength of local public opinion in favor of the forests and hence made sacrifices of forestland where none were needed, but in the larger issues he was a shrewd promoter of good public relations. [2]

Both Graves and his successor, William B. Greeley, took a deep and personal interest in the Alaskan forests. Pinchot had, for the most part, delegated authority to Langille and followed his recommendations to the letter. Graves not only inspected the forests of Alaska himself—and wrote well and wisely about them—but also sent a series of inspectors from the Washington Office (Earle H. Clapp, James B. Adams, and Arthur Ringland) to bring him recommendations and information to supplement the regional and district reports. He believed, as had Langille, that the Forest Service should be a force for the orderly, rather than haphazard, development of the country. He fought fearlessly for the forest interest in Alaska against forces in Congress, the General Land Office, and the Alaska Railroad. His trip to Alaska was a successful goodwill tour, and he strongly supported Langille's ideas in regard to recreational management in Alaska.

In Washington he faced a great deal of political and bureaucratic infighting. When he took office, he had some difficulties with Secretary of Agriculture James Wilson on determining the sphere of his authority, and only by appealing personally to President Taft did he obtain the authority he thought necessary. After this episode his relationship with Secretary Wilson was excellent. David F. Houston, President Woodrow Wilson's secretary of agriculture, strongly supported Graves and the Forest Service. In the Department of the Interior, Ballinger was succeeded in 1911 by Walter L. Fisher, a strong conservationist who made a trip to Alaska and settled the Bering River coal claims but felt that the Forest Service might logically rest in his department. President Wilson believed that the post of secretary of the interior should go to a westerner and so chose Franklin K. Lane of California. Lane was reputed to be a friend of conservation, but his record was indifferent. His main accomplishment was the creation of the National Park Service, an agency at first opposed, then favored, by Graves. A greater enemy of the national forests was Clay Tallman, commissioner of the General Land Office. Like Dennett and Ballinger before him, Tallman was suspicious of the Forest Service's actions and motives. [3]

In the political realm President Wilson was indifferent to conservation. He had carried some of the western states in part because of the assumption that he would be friendly toward a states-rights philosophy in regard to resource management. In the Congress, Representative William E. Humphrey of Washington and A. W. Lafferty of Oregon, along with Delegate James Wickersham of Alaska and Senator Albert Fall of New Mexico, were all highly critical of the Forest Service. Graves and William B. Greeley spent a great deal of time testifying before congressional committees. Bills were introduced to turn the national forest lands over to the states, or to cut appropriations. But there were countervailing forces. Conservation had good friends in Congress, such as Senator Miles Poindexter of Washington and Senator Charles L. McNary of Oregon. Of the several good pieces of legislation passed, one of particular importance to Alaskan forests was the Agricultural Appropriations Act of August 10, 1912. One part of the act provided that 10 percent of all receipts from national forests should be used for the construction of roads and trails within the forests. Another part of the act authorized the secretary of the interior to select, classify, and segregate all lands that might be opened to settlement under the homestead laws. Even more important, however, were court decisions in support of conservation. In a series of decisions between 1911 and 1920, the Supreme Court gave constitutional validation to most of the Roosevelt-Pinchot conservation policy. [4]

|

| Henry Solon Graves replaced Pinchot as chief of the Forest Service in 1910 and served for a decade in that position. Graves, a great forestry educator at Yale University before and after federal service, took a special interest in Alaska and made a much publicized tour in 1915. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The Politics of Alaskan

Conservation, 1911-1919

The backlash against the national forests during Graves's administration took different forms in different regions of the United States. Thus, grazing problems in Colorado and Wyoming, timber claims in Washington, agricultural lands in eastern Oregon, and light burning in California all represented local crises for Graves and for the district foresters. [5]

Guild-group resolutions and public land conferences all served as forums from which to publicize grievances. Alaska had its own peculiarities. The rhetoric involved in most cases was the time-honored cry of the frontiersman against the "Broad Arrow" policy of the government: locking up resources that rightly belonged to the farmer or the miner, red tape in getting land, faulty allocation of resources (favoritism showed to the big interests, the Morgans and Guggenheims), and lack of self-government for Alaska. Selfish personal interests were involved, as well as misinformation. The strained relations between the Interior and the Agriculture departments, and between the General Land Office and the Forest Service, were often reflected in their field divisions. [6]

Attitudes toward the national forests and the Forest Service varied from place to place in Alaska. Generally speaking, the people living on or near the Tongass National Forest were not unfriendly. They had no particular grievances; timber sales flourished and were satisfactorily managed, and there was a boom in salmon fishing after 1914. The staff in the area—Supervisor William G. Weigle, George Drake, Roy Barto, George Peterson, Kan Smith, and William Babbitt—were generally liked. Farther north, on the Chugach, there was sporadic hostility. In the Bering River country the Forest Service was unjustly blamed for cancellation of coal claims and lack of development. There were timber trespass difficulties in the Katalla area. Inland, Andrew Christensen and C. W. Ritchie of the General Land Office pursued a vendetta against the Forest Service, and by 1915 the Alaska Engineering Commission (predecessor of the Alaska Railroad) had begun its long era of bad feelings with the Forest Service in the Kenai area. Yet, public opinion is difficult to evaluate. The Service had such disparate friends as Jack Dalton, the Cordova bad man, and John E. Ballaine, the Seattle-Seward capitalist. There was certainly no monolithic wave of ill-feeling against the Service, and after 1915 general relations tended to improve.

Opposition to Alaska national forests took many forms. In Congress a bill was introduced to abolish the Chugach National Forest and another to eliminate funds for its operation. The argument was made that the national forest held up development, was unnecessary, had no commercial timber, and had valuable agricultural land. Graves and Greeley spent many hours at committee hearings defending the Forest Service and its policies against the uninformed questions of Senators Wesley Jones and Thomas Walsh, and the hostile questions of Delegate Wickersham. The annual reports of Alaskan governors also called for abolition of the Chugach, as did the first territorial legislature.

|

Nine National departments, through twenty-three separate offices or bureaus, deal with the public business of Alaska. Their several duties and responsibilities are graphically shown below: DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE Forest Service. Controls use and sale of lumber, homesteads, mineral rights, power sites, etc., in Chugach and Tongass National forests, with combined area of more than 25,000,000 acres. Biological Survey. Has charge of bird reserves; controls scientific investigations and experiments in propagation and development of animal life. Experiment Stations. Maintained for encouragement of agriculture, experiment and demonstration of farming methods, crops, battle breeding, etc.; sells crops grown on experimental farms. NAVY DEPARTMENT Maintains buildings, conducts coaling station, and makes tests of native coal; sends vessels to coast in course of cruises; maintains and operates wireless telegraph stations along coast. WAR DEPARTMENT Road Commission. Controls building of roads and trails with funds appropriated by Congress and set aside from license receipts. Engineer Corps. Controls surveys, estimates, and work on river and harbor improvements. Signal Corps. Controls construction, maintenance and operation of cable between Alaska and the United States and inland telegraph lines and wireless telegraph stations. The War Department also maintains barracks and troops in Alaska. TREASURY DEPARTMENT Controls collection of customs duties, internal revenue, income tax; supervises and plans construction of public buildings; maintains revenue cutter service; makes public health regulations; maintains life-saving service. POST-OFFICE DEPARTMENT Controls mail service. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Bureau of Fisheries. Protects seals and foxes and sells sealskins and fox skins on Pribilof Islands; controls leasing of certain islands in Aleutian group for fox ranching; employs wardens and makes regulations for protecting fur-bearing animals; supervises and regulates fisheries, canneries, etc. Census Bureau. Takes the decennial census. Bureau of Lighthouses. Constructs and maintains lighthouses, fog and light signals along coast. Coast and Geodetic Survey. Charts and channels rocks and obstructions to navigation along coast. Steamboat inspection Service. Inspects and licenses steamboats, engineers and officers of steamboats. Navigation Bureau. Makes and enforces navigation rules and regulations. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE Controls court machinery, marshals, United States attorneys and commissioners, and generally administers law and justice in the Territory. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR General Land Office. Controls entry, patent, and disposal of public domain; controls and disposes of timber on public lands outside the National forests; disposes of applications for homesteads, mill sites, mineral claims, trade and manufacturing sites, town sites, coal and oil sites, and rights of way in public lands; controls water power and power sites outside of National forests; handles accounts and returns of Surveyor-General's office. Geological Survey. Investigates mineral formations, coal and oil fields, water supply and stream flow, hot springs, etc.; makes topographical and geological maps of the Territory. Bureau of Mines. Supervises inspection of mines and mining; enforces mining laws. Bureau of Education. Supervises education of Eskimos and other natives and reindeer industry among natives. Secretary's Office. Supervises care and custody of insane; handles general correspondence as to Alaskan affairs; disburses appropriation for protection of game by wardens appointed by the Governor under rules and regulations of Departments of Commerce and Agriculture; acts as clearing-house for general Alaskan matters, and performs other functions not specifically charged to other departments. |

from Franklin K. Lane (Secretary of the Interior), "Red Tape in Alaska," The Outlook. January 20, 1915. p. 139

A greater threat was the suggestion of Secretary Franklin Lane of the Interior Department that an Alaskan Commission, similar to the Philippine Commission, be set up to manage all resource matters in Alaska. The commission would consist of five members, including the governor of Alaska, the surveyor general, and three others, to replace the federal agencies. In a 1914 article in the National Geographic, Lane blamed all the trouble of Alaska on the numerous uncoordinated agencies with overlapping functions in the area. Graves opposed the commission and enlisted the aid of Herman H. Chapman in fighting it. Chapman, a Yale professor of forestry and a noted fighter for forestry and conservation, enlisted the support of the American Forestry Association, which passed a resolution protesting the idea. The commission idea had a hardy life; it was revived again during the Harding administration by George Curry of New Mexico. [7]

A minor furor arose over a proposed elimination in Controller Bay; for a time it gave reporters a field day. Richard Ryan, a Seattle capitalist, wanted to have 320 acres on the west side of the Bering River eliminated from the national forest to be used as a site for a railroad terminal, pipeline, and docks for his projected Controller Bay Railway and Navigation Company. He planned to use soldiers' additional homestead scrip to obtain the land. In December 1909 Ryan made the request to Pinchot, who referred it to the local officers. Langille conferred with Ryan, examining Ryan's maps and the intended elimination. The area consisted solely of untimbered mudflats, and Langille had no objection to the elimination. However, the Catalla and Carbon Mountain Railway Company had already applied for a special-use permit to set up a terminal in the same area. The Alaska 80-Rod Law provided that a settler or manufacturer could not take up more than 80 rods of the coast or a navigable stream, and a space of 80 rods was required between each occupant. Under this law, a 320-acre elimination would have given Ryan a monopoly on the tract. Langille recommended a larger elimination, that of twenty square miles of mudflats. The Forest Service at that time was in the process of eliminating untimbered land from the Chugach Forest, and the larger tract would avoid giving Ryan a monopoly. Langille also insisted that the Navy be consulted, but the Navy had no interest. Ballinger consulted with the Forest Service and, after consideration, recommended a 12,800-acre elimination. This was made in 1910.

Unfortunately, the newspapers, their appetites whetted for scandal after the Ballinger-Pinchot affair, printed erroneous reports on the elimination to the effect that it was a scheme to aid the Guggenheim monopoly. The Senate passed a resolution asking for an investigation. Miss M. F. Abbott, a newspaper writer, was given permission to examine Land Office files. She claimed to find a letter showing a fraudulent connivance in the elimination involving Ryan, Ballinger, and the president's brother, Charles P. Taft. An investigation was held, and in the end Congress decided that the Abbott letter was a hoax. [8]

Gifford Pinchot became concerned with the Controller Bay incident and decided to make a trip to Alaska to see for himself the area that figured importantly in his recent firing. In September 1911 he traveled to Ketchikan, where the Forest Service impressed him with the size of large spruce logs brought into the Ketchikan Power Company mill. At Ketchikan he met U. S. Rush, who he characterized as a "kicker against the Forest Service." He traveled to Cordova and acquired Jack Dalton as a traveling companion or, the less charitable said, a bodyguard. Dalton was a colorful character; he had traveled to Alaska in the 1880s. During the gold rush of 1897, he had established a toll road to the interior, the Dalton Trail, over much of what now is the Haines cutoff. In an early encounter Dalton had threatened to shoot Langille, but the unarmed ranger had faced him down. Since then Dalton had become a friend of Forest Service policy. Pinchot then went to the Kenai, where he traveled on the Alaska Central Railroad—a "badly built and badly laid line"—and spent some time in and around Katalla, inspecting the Cunningham claims. He helped W. G. Weigle, George Johnson, and T. M. Hunt get the Forest Service launch Restless off the beach where it had suffered one of its frequent mishaps. He traveled on to Chitina and explained Forest Service policy at a mass meeting there, returning to the states in October. [9]

The attacks on the Alaskan forests prompted a large number of inspections from the Washington Office. James B. Adams and Earle H. Clapp made inspections in 1913. Graves himself, with E. A. Sherman, traveled around the national forests and inspected the forests of the interior in 1915. Arthur Ringland made a reconnaissance of the Kenai Peninsula in 1916. In addition, there were inspections from Portland. To a large extent, the inspections concerned Forest Service efforts to eliminate untimbered areas from the forest and to classify agricultural land. They were also concerned with administration, timber sales (especially pulp possibilities), recreational development, game refuges, settlement, and personnel.

Graves went to Alaska to get firsthand information with which to meet attacks from the Department of the Interior. He obtained copies of Langille's reports, especially those dealing with the Chugach and the interior of Alaska, and also reports from Adams and Clapp. His journal of the Alaskan trip is a fascinating account of the state of the region and of Alaskan forest conditions in 1915; it deserves publication. He started his journey by train to Portland, where he conferred with the district office and the Portland Chamber of Commerce about recreational development in the Mount Hood area and along the Columbia River Highway. He went by steamer to Ketchikan, boarded the Tahn, and, with Supervisor W. G. Weigle, E. A. Sherman, and Lyle Blodgett, visited the fish canneries and the Thorne Arm area, where there was interest in a pulp proposition. They visited Metlakatla, saw the totem poles at Cat Island, the Ryus homestead on Duke Island, inspected Sulzer and Coppermount and the woods of Prince of Wales Island, inspected the quarries of the Vermont Marble Company on Marble Island, and reached Wrangell on July 23.

|

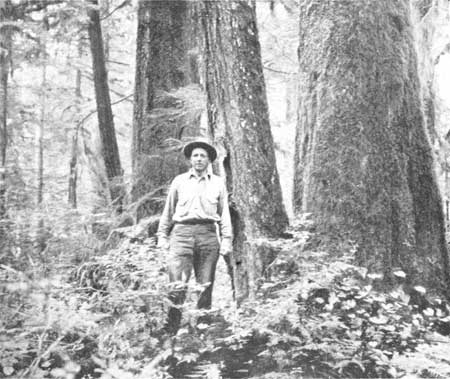

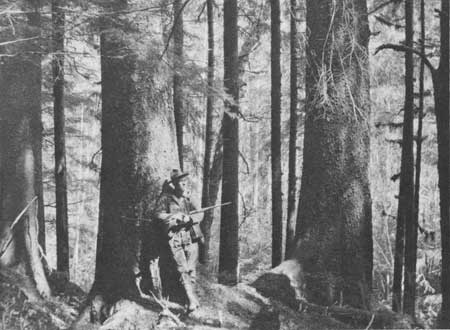

| Chief Henry S. Graves examined heavy stands of timber on the Tongass in 1915. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Graves went from Wrangell to Petersburg and was struck by the beauty of the Wrangell Narrows. Along the shores of Frederick Sound, he looked over the timber, visited Kake, inspected totem poles, and talked with Charley Grant, the village's totem carver. Then he went to Warm Springs Bay and between Chichagof and Baranof islands to Sitka. At Sitka he inspected the experiment station and the timber sale at Silver Bay. He then visited Tenakee and Hoonah and traveled to Juneau, where he visited Taku Glacier and took the newly constructed road to Mendenhall Glacier.

Graves desired to see the forests of the interior, so they set sail for Haines and Skagway. He traveled over the White Pass Railroad to Lake Bennett and Whitehorse, then took a riverboat down the Yukon and up the Tanana to Fairbanks. From Fairbanks he traveled by Ford stage down to Valdez, where he boarded the launch Restless for trips around Prince William Sound. He took the Copper River & Northwestern Railway up to Chitina, inspected the Alaska Railroad and the new town of Anchorage, and then headed home in September.

|

| Chief Forester Henry S. Graves photographed Main Street in the new city of Anchorage during his 1915 trip to Alaska. (U.S. Forest Service) |

There are themes in the Graves journal that illuminate both his personal interests and his character. He had a keen aesthetic appreciation of the Alaskan landscape, both in the Inside Passage and in the interior. He gives a striking description of a sunset over Mount McKinley:

At nine P.M. we stood on the bridge and saw Mt. McKinley, The sun was setting, red, and with a marvelous setting of thin strata clouds, giving a pink glow to the mountain. High above the horizon, it rose with its three peaks, snow covered and monumental, though 130 miles away, It was one of the rare moments when one catches his breath, looks hard and eagerly, for fear the sight will vanish. There is an unreality about the scene, making it seem a vision, not a fact. And as the boat swung round a point blotting out the mountain, I turned to the flaming clouds, still colored by the sun that itself had sunk below the horizon. And as the colors faded to slaty blue I felt that rare elation one sometimes experiences after hearing a wonder strain of Music.

Sights of the Indians in their birchbark canoes on the Yukon evoked memories of his early reading of James Fenimore Cooper. He was also impressed with the beauty of the Copper River near Childs Glacier, where Langille had desired to establish a national monument.

Graves had a keen interest in human nature as well. He was delighted by Weigle's large fund of mildly Rabelaisian frontier stories and recorded a number of them in his journal. The journal abounds with vignettes of the men he met. Graves was particularly critical of Woodrow Wilson's political appointees. He was shocked by the recreational management of the mineral warm springs at Warm Spring Bay and Tenakee. Of Tenakee Springs, he remarked: "It is a dirty, unsanitary place and sure to carry diseases. A public bath tub, with no one to look after it, is a dirty filthy improper affair and must be changed."

Graves was impressed with the large timber values on the Tongass, and with the waterpower and possibilities for pulp development. He also remarked favorably on the timber on the Chugach; though it was not as great in volume as the Tongass, he noted "This reminds me of the miner at Nome who complained of certain diggings because it was half dirt." The vast destruction of timber in the inland, both on the Yukon side of the boundary and in Alaska, distressed him. Graves noted that the General Land Office men did a satisfactory job in claims and timber work but did nothing toward fire prevention or suppression. He also noted that many of the fires were set by railroads or the Alaska Road Commission. This reinforced his desire that the Forest Service take over the task of fire protection for the entire territory.

Graves examined agricultural possibilities both inland and in the southeast. In the coastal area, he noted, farmers usually cultivated gardens to supplement fishing. He felt that the Forest Service could render service to farmers by building farm-to-market roads, using proceeds from timber sales. He was interested in the possibilities of farming combined with ranching in the interior. [10]

Graves's visit, as well as his recommendations, had a salutary effect. One of his purposes was to make a goodwill tour; this he achieved. He talked with influential men, explained Forest Service purposes, and succeeded in persuading people that Washington had their welfare at heart. His success was particularly marked in the interior, where his visit had a good press. Under Pinchot, concern with the national forests in Alaska had been largely delegated to Langille, whose recommendations were usually accepted in the Washington and Portland offices. Under Graves and his successor, W. B. Greeley, Washington took a direct interest in the national forests of Alaska.

One of the men not impressed by Graves's visit was Andrew Christensen. He had grown up in Nebraska during the homestead era, had become a railroad attorney, and was favorably impressed with the land and immigration policies of the land-grant railroads. He joined the General Land Office in 1908, first working near Portland, and then coming to Alaska as chief of the Field Division. He believed sincerely that the Land Office should hold to its historic function of disposing of the public domain. He believed that the future of Alaska was in agriculture and felt that the Forest Service hindered Alaskan development. His views in these respects were similar to those of Ballinger, but with two exceptions: Christensen was concerned with the local settlers, rather than with keeping Alaska an economic dependency of Puget Sound, and he was highly self-assertive, in contrast to the reticent Ballinger. Aggressive, loquacious, self-righteous, and sometimes unscrupulous, Christensen was a highly effective adversary of the Forest Service and an able propagandist for disposal and development. [11] His battles with the Forest Service are revealing and deserve consideration at length.

On August 15 and 29, 1915, C. W. Ritchie, special agent of the General Land Office in Fairbanks, sent Christensen letters relating to the Graves journey and clippings from the Fairbanks Daily Times. Ritchie was under the impression that Graves and his party were planning to establish national forests in the Yukon and the Tanana valleys. The Daily Times, he reported, was impressed by their plan to hire men to fight fires and by the fact that local districts in Alaskan national forests participated in funds from timber sales. Graves had advocated setting up a chief of fire protection, or fire warden, in each of the judicial districts, paying men to fight fires, and following the California plan of allowing wardens to draft men to fight fire.

Ritchie referred to Graves's trip as "a junket pure and simple." Christensen wrote to Clay Tallman, commissioner of the General Land Office, on October 18 and 19, enclosing Ritchie's letters and clippings. He stated that the Forest Service did nothing to protect the forests that could not be done at less expense by the General Land Office, that the Forest Service delayed settlers who wished to get title to land, and that much of the land was better for agriculture than for growing timber and should be burned off, both to clear the land and because the ash would be good fertilizer.

Probably at Tallman"s request, Robert Leehey, of a Seattle law firm, wrote to Tallman urging abolition of the Chugach National Forest, both to open it up to agriculture and to open up the Bering and Katalla coal fields. Leehey asserted that the land could be better handled by the General Land Office. Tallman gave the fie to Secretary Lane, who forwarded it to Secretary of Agriculture Houston, asking for his comments.

Houston's response was firm support of the Forest Service and of Graves. He felt that there were three questions involved: requests for abolition of the Chugach National Forest; fire protection in the interior of Alaska; and the propriety of Graves's visit. On the first, he stated firmly that the Chugach should not be abolished. He felt that there was need for further decentralizing authority but pointed out that 95 percent of the problems were settled locally—and most of the others in the Portland office. Only a small percentage of the problems came to Washington. There was, he wrote, apprehension as to the extent and value of the Chugach. The rugged terrain and glaciated mountains gave the impression of an untimbered land, but below the timber line there were 6 to 8 billion feet of commercial timber of great potential value as sawtimber, ties, and piling.

Secretary Houston then turned to the Christensen protests. He denied Christensen's statement that the Forest Service did little to protect the forest and that the General Land Office could do a better job. He pointed out that the Forest Service had a fire suppression force, though it was inadequate in size, and that the Land Office had no suppression force whatsoever. He suggested that there might be cooperative fire control in the Lynn Canal area, where Graves had seen untended fires on the public domain adjacent to the national forest. "The handling of forests is not mere routine administration," Houston stated. "Practically all the work involved specialized knowledge and experience." Scaling, cruising, and timber-sale work involved skills and education that the average Land Office employee lacked. He denied that the Forest Service held up settlement or hindered individuals from taking up forest homesteads. "The existence of the Forest does head off timber speculators," Houston wrote, "but it substitutes orderly and permanent development for hasty and ill-considered occupancy." Finally, as to the Graves trip being lacking in propriety, he asserted that it was made "with my entire sanction and partly at my suggestion." Commenting on the letter, Tallman wrote to Christensen that he was "more or less impressed by it."

But Christensen was not impressed, as he explained in a forty-two-page letter to Tallman. He dealt with his boyhood in Nebraska and how he had witnessed the drama of the railroad, under liberal land laws, opening up the West and conquering the frontier. Acknowledging that the General Land Office had no timber sale officers, he stated that they could hire some and do the job more cheaply than the Forest Service could because of a unified administration. He denied that the cruises had really showed 6 to 8 billion feet of timber on the Chugach; the volume, he stated, had been grossly overestimated. The land, moreover, would produce more revenue if put to potatoes instead of raising spruce. In regard to fire protection, he felt that there was no need for a withdrawal into a national forest for fire protection; the Land Office could do the job on the public domain. Christensen took exception to Houston's term, "ill-considered occupancy"; the history of the West showed that the liberal land policy of the government had resulted in creation of prosperous farmers and thriving industrial communities. There was, he stated, more ill-considered occupancy within the national forest than without. He cited the report of Hugh Bennett on agricultural land on the east side of Cook Inlet, suggested that the answer to cooperation in fire control on Lynn Canal was to abolish the national forest in that area, and stated that if the forests were to be opened to homesteading, they should be abolished. Finally, he regarded Ritchie's statement on Graves's "junket" as unfortunate.

Christensen continued his attacks during 1916. Supervisor Weigle reported to the district forester in Portland that Christensen had asked C. B. Walker, register of the General Land Office in Juneau, to submit a statement showing how "the National Forests of Alaska interfered with the development of Alaska." He had also requested a letter from Charles E. Davison, the surveyor general, on the same subject. Walker drew up a rather mild statement, a copy of which he submitted to Weigle. The statement ended, "I have seen no friction or want of cooperation between the Land and Forest Bureaus since I have been in Alaska, or any just reason for it."

On March 26, 1916, a conference was held in the office of Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Carl Vrooman to deal with the problems of Alaska. Attending were representatives of the Forest Service, Bureau of Mines, General Land Office, and Alaska Engineering Commission. Christensen was one of those in attendance. The conference was too short for him to say all that he wanted, so he wrote a 150-page statement to supplement his spoken remarks. He delayed submitting it to the Land Office, because the next day, March 27, he was appointed land manager to the Alaska Engineering Commission. [12]

Christensen's magnum opus, entitled "A Statement of Facts Relating to the Chugach National Forest Reservation with Reasons Why the Lands Within it Should be Restored to Entry So as to Encourage Development," is an interesting piece of work. He dealt with the creation of the reserve, citing Langille's doubts and speculations in regard to the Kenai and the Knik Arm areas and Langille's statements that the area might well be preserved without withdrawal. Christensen expounded at length on the idea that the purpose of the railroad was to develop the country and that there was a conflict between the railroad and the reserve ideas. He cited local petitions criticizing the reserve and the committee hearings of 1914, which had been highly critical of the Chugach. He felt that the reserve should be abolished on many grounds: there was no danger of fire or of timber monopoly; no need for grazing regulations or watershed protection; there was a large amount of agricultural and mineral land in the national forest; the existing eliminations from the reserve had been of no value to the public; and the railroad needed traffic from agricultural and mining lands to make it a success. He questioned the estimates of Langille and Graves as to the commercial timber in the area and substituted estimates of his own from reports of Alfred Brooks and George A. Parks, mineral examiner of the Land Office in Alaska. He pointed out that the Alaskan timber was poor for construction purposes, as compared with that of Puget Sound, and that Alaska imported a large volume of timber. He cited the recent studies of Hugh Bennett and E. C. Rice on agricultural land in the Knik Arm area, claiming that if the timber were burned over the land would come up with grass and be suitable for agriculture. [13]

Arthur Ringland of the Forest Service was assigned the task of answering Christensen. Ringland had been in Alaska the year before and had been very much impressed with the possibilities of the Kenai for recreation and for photographing of wild game. He answered Christensen with a 150-page report of his own. About Christensen he remarked, "He has designedly conveyed wrong impressions, with no doubt the purpose of stirring up prejudice." Ringland stated that Christensen had ignored the Forest Homestead Act of 1906 and the Agricultural Appropriations Act of 1912 in his claims that the Forest Service hindered settlement. He pointed out that Alfred Brooks, whose timber estimates Christensen cited, had not visited the area. He asserted that the General Land Office did not protect the timber and that the Tanana Chamber of Commerce had protested about the agency's indifference to fire. He questioned Surveyor Parks's competence to make timber surveys, pointed out counterreports about the durability of Alaskan timber, and demonstrated that the federal Alaska Railroad, then under construction, was using local timber. Ringland's report was a point-by-point refutation of the Christensen report. [14]

|

| Arthur C. Ringland of the Forest Service was assigned the task of answering the charges of An drew Christensen of the General Land Office. Ringland had made a reconnaissance of the Kenai Peninsula in 1916. Here photographed at Albuquerque, New Mexico, in 1912, Ringland was at the time of this writing (1979) the oldest living veteran of the Forest Service. (U.S. Forest Service) |

With Christensen's appointment to head the Land Department of the Alaska Engineering Commission (then building the Alaska Railroad), he gave his attention to promoting agriculture in the area tributary to the railroad, and his vendetta against the Forest Service took other forms. [15] His successor as head of the Field Division of the General Land Office in Alaska was George A. Parks, later governor of Alaska. He was also hostile to the Chugach but easier for the Forest Service to get along with.

The divergent views of Christensen and of the Forest Service, particularly as expressed by Langille (and later by W. B. Greeley), show in sharp contrast two aspects of the relationship of the frontier to conservation. Christensen idealized the farming frontier, with its hardworking, self-reliant homesteader. Langille admired the trapping and mining frontier of the past, with its self-reliance and individualism, but he felt that the frontier's lack of controls must make way for regulation in the public interest. Christensen had an optimistic view of the future of agriculture in Alaska. Langille was skeptical, pointing out lack of markets and uncertain weather conditions. Christensen desired a promotional development, with the railroad serving to further a hot-house colonization of the area. There might initially be some chaos, but order would develop out of it, as it had on other land-boom frontiers. Langille desired an orderly and guided development, with the government preventing the waste in men and resources inherent in haphazard and speculative development. Christensen saw the forest as an obstacle to settlement and an encumbrance on land that could be put to more productive uses. Langille saw the forest as the building material for miners, fishermen, trappers, and farmers as they slowly developed the resources of the country. Christensen saw the area as a future Dakota or eastern Oregon, with full-time farmers harvesting bountiful crops. Langille envisioned its future as one of mining, fishing, subsistence agriculture, and as a vacationland for the hunter and photographer.

|

| William G. Weigle, 1910-1919. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Supervisors, Rangers, Boats,

and Sporting Women

During this period of interdepartmental and interagency infighting, the basic work of the Forest Service went forward. Much of the infighting appeared primarily as froth and bubbles, while real work of substance was going on.

William G. Weigle was the successor to Langille, who resigned from the Service on July 31, 1911. Weigle, like Langille, came to Alaska with a varied career behind him. In age a contemporary of Langille, he had taught in a normal school and worked on a railroad before being attracted to forestry by an advertisement for a course at the Milford Summer Forest School of Yale University. The school was run on the Pinchot estate at Milford, Pennsylvania. He took the course there and then continued at Yale. He worked as a student assistant for the Bureau of Forestry in New Hampshire in 1903, spent 1904 examining woodlots in Ohio with Raphael Zon, and gave lectures in forestry at the state universities of Utah and Ohio. He became a member of the Forest Service in 1905, making pulp mill studies in Pennsylvania and examining woodlots in New York.

Later in 1905 Weigle took charge of a timber sale to the Anaconda Copper Company in Montana and then a railroad tie sale in Wyoming and Colorado. He subsequently did timber sale work in Wisconsin and had a series of assignments in western New Mexico, Nevada, Oklahoma, and southern Oregon. In 1909 he became supervisor of the Coeur d'Alene National Forest at Wallace, Idaho. One of his first jobs was to clear saloons and other unlawful dives from the national forest land—a task that foreshadowed later work at Anchorage. He was a hero of the famous 1910 fire in Idaho and Montana. Early in 1911 he went to Alaska. Langille gave him in-service training in running boats and navigation until Weigle succeeded him as supervisor.

Weigle was a large, powerful, redheaded man of German ancestry. He was a man of action rather than a philosopher, a practical forester who liked fieldwork. He was well liked by his staff, and inspection reports give him good ratings. Graves had him as a student and later enjoyed his rough frontier humor and store of jokes. Arthur Ringland wrote of him: "He has served for five years in Alaska under adverse and often trying conditions. He is a very human type of man, well liked and respected. Above all, he has the essential quality of aggressiveness tempered with push."

To the men who worked with him, Weigle was often a figure of fun. Langille had the capacity for unbending, but at times and places of his own choosing; his relations with men under him were somewhat formal, with the exception of such intimates as Blodgett and Wernstedt. Weigle, on the other hand, was on more relaxed terms with his men. His foibles, stubbornness, bachelorhood, style of doing his job—all were matters of comment, and a large number of stories and legends have grown up around Weigle. George Drake remarked of him:

I learned a lot about how to get along. I didn't push things. If I wanted to do things a certain way, I'd talk to him and if he'd rebuff it, I'd just clam up and wouldn't say any more; then I'd just go ahead and do things as I thought it ought to be done, and he could see the results. If they worked, he never said anything. But if you asked him, he'd have to tell you how to do it. [16]

Forest Service staff in Alaska increased during Weigle's tenure. George Drake came to Ketchikan in 1914 as forest examiner. A New Englander who was educated at Penn State, he was a highly competent surveyor and the only man in the Service in Alaska who could run a transit. In the Kenai area, Thomas M. Hunt came in 1911 as deputy supervisor. He had several assistants and scalers and rangers at Cordova and at Katalla. George Peterson became ranger at Sitka in a large district that extended to Yakutat. His diary has a great deal of unconscious humor in it. Some men came on special assignments, as did Kan Smith, a timber expert who examined pulpwood shows, or Asher Island, who came from eastern Oregon to classify land. [17]

|

| George Drake, here photographed in Alaska about 1916, later became president of the Society of American Foresters. (George Drake Collection) |

Alaska remained under the jurisdiction of District 6, with headquarters in Portland. The district forester during this period was George H. Cecil. A native of Baltimore, Cecil had graduated from the Biltmore Forest School and went to Wyoming and Montana, where in 1906 he did some of the first roadside beautification work in the Forest Service near Yellowstone National Park. He came to the Portland district in 1909 and succeeded to the post of district forester in 1911, when C. S. Chapman resigned to work for the Weyerhaeuser Timber Company. Redhaired, freckled, and youthful in appearance, Cecil was an able and popular district forester. He had a deep interest in Alaska and made several inspection trips to the area. [18]

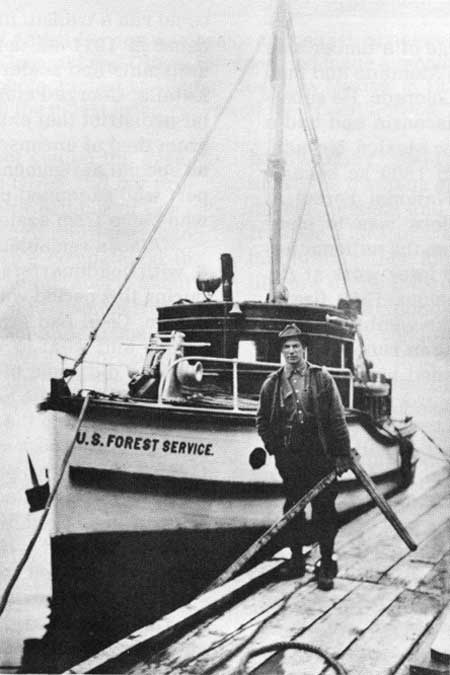

With additional staff came more boats. The beloved Tahn remained the supervisor's boat and the flagship of the Tongass navy. For the Prince William Sound area, the thirty-three-foot launch Restless was built at Ketchikan and sailed up. A tender, the Prospector, was also used there. The Restless was an unfortunate boat, highly accident-prone. Its log and the diaries of rangers carry many accounts of broken propeller shafts. Once the Restless drifted helplessly for three days until it was taken in tow by a fishing vessel. In 1911 Weigle made a miscalculation and ran the Restless onto rocks near Katalla, punching three holes in the hull. Temporary repairs were made with canvas, thin boards, and tar, but it cost the Forest Service $50 to have it pulled into the water again. In Anchorage, while being loaded with gasoline, the boat caught fire and was damaged. The Restless was taken out of commission in 1919, having completely worn out.

|

| Boats served as homes and offices in the field. (Rakestraw Collection) |

Three boats of the Ranger class, thirty to sixty feet long, were purchased and brought up from Puget Sound. They were of good construction but underpowered. The original motors were 12-horsepower engines, "as the result," wrote Ray Taylor, "of a decision made by some clerk or accountant somewhere in the states." For this reason they sometimes went backward in a "skookum-chuck" or when faced by strong winds, ending up on the beach in some isolated inlet. The motors were replaced with 25- or 30-horsepower engines. The Ranger 4 was built in Ketchikan, according to George Drake, "by some house carpenter from a knockdown plan you could get out of Detroit." It had a good motor, but the hull construction was such that it shipped water in a headwind. With these boats, the rangers were at least mobile.

In addition, a wanigan house scow was built in 1909 as a portable field station. It was towed around by the Tahn or one of the other boats to timber sales and other projects that involved a stay in one place for a period of time. It was much more comfortable for a small crew than tents on the beach. As fieldwork increased, the small wanigan could no longer take care of large crews and equipment; in 1920 a much larger one was built. The smaller one was taken over in 1948 by the Alaska Forest Research Center. [19]

Handling the boats called for special skills. "In the administration of the forests," Weigle wrote, "the motorboat takes the place of the saddle and pack horse, hip boots and a slicker the place of chaps, and it is much more essential that a ranger know how to adjust his spark plug than be able to throw a diamond hitch." E. A. Sherman wrote:

With its 12,000 miles of shoreline the Tongass National Forest is completely equipped with an admirable system of waterways. The Forest Ranger in most of the National Forests in the United States depends usually upon his saddle and pack horses for travel and transportation. Not so the Forest Hanger in Alaska. Here...he rides a sea-going motor boat. His steed may do just as much pitching and bucking, but this is prompted not by a spirit of animal perversity but by the spirits of climatic adversity. He guides his steed by means of a wheel instead of reins; feeds it gasoline instead of oats; tethers it at night by means of an anchor in some sheltered cove instead of a picket rope in a mountain meadow, and uses a paint brush in lieu of a curry comb....

The Alaskan ranger is just as proud of his boat as the Bedouin horseman is of his steed, and the Ranger boats in Alaska are the most distinctive craft sailing the waters of the Alexander Archipelago. They are named Ranger No. 1 to 5, consecutively, have yellow sides and decks, with carmine trimmings. They are staunch boats, several of them having been built at the Bremerton (Washington) Navy Yards according to a special design which gives strength, seaworthiness, and special ability for the particular service expected to them. In case of any trouble or disaster in southeastern Alaska, shipwrecks, sickness, or sorrow, the public appeals to the nearest Ranger boat, and if the request is a proper one or a reasonable one, the appeal is never in vain. [20]

The fieldwork of the men varied a great deal. Usually in pairs, sometimes with a cook if several men were in a party, the Forest Service men did a tremendous variety of work and put in a good deal of "coal oil time" in addition to the regular day's work. They surveyed occupation sites, or sites of June 11 homestead entry (Forest Homestead Act), mapped power sites, set up gauging stations, marked timber sales, cruised timber, scaled log rafts, and taught the loggers to abide by Forest Service cutting rules. They enforced the fishing regulations, especially preventing fishermen from setting nets at the mouths of streams. They surveyed and mapped fox farms, rabbit farms, saltery and cannery sites, an aerial tramway, cabin sites, hay meadows, net racks, pastures, powder houses, residences, sawmills, railroads, whaling stations, town-sites, roadhouses, hot springs, and Indian villages. They furnished transportation for a large number of individuals on business or on junkets, including inspectors for the district or Washington offices, the governor of Alaska, the head of the experiment station at Sitka, senators and representatives from the Lower 48 and the Alaska legislature, employees of the Lighthouse Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Fisheries, Geological Survey, Bureau of Soils, General Land Office, National Park Service, and businessmen looking for pulp prospects.

The men did a great deal to break down the isolation of the scattered villages and settlements and cabins around Alaska. A ranger, going into one of the larger settlements would carry with him a shopping list "as long as a peace treaty," one ranger wrote, "and involving about six months pay." Usually the individuals didn't know what the items cost, promising to pay the ranger when he got back. Tobacco, whiskey, 45-70 shells, materials for making a dress, toys and books, nursing bottles and nipples, stovepipes, nails, hip boots, net floats—all were typical of the items ordered. They carried on rescue work, towing in boats whose engines had broken down and organizing search missions for men missing or lost. When a flu epidemic hit Hoonah, George Peterson ran nonstop from Hoonah to Juneau and back to get serum, going seventy-two hours without sleep. Sometimes they found tragedy. Ranger J. M. Wyckoff once found a lonely handlogger who had got his foot pinned by a log and had starved to death while waiting rescue. [21]

Work was hazardous, with danger from storm, tides, and accidents in isolated areas. There were other difficulties as well. "The ground cover is mostly mosquitoes," Asher Ireland remarked of his classification work in the Kenai. Though the men wore veils and gloves, the mosquitoes were active during most of the long daylight hours. Bears were a hazard in many areas, particularly in the thick forests of the Tongass; there were many close calls.

Cruising timber on the Tongass was difficult. There was a thick undergrowth of skunk cabbage, huckleberry brush, and, above all, devilsclub. Trees had huge buttressed roots, so the traditional method of taking the tree's diameter at breast height (DBH) was difficult if not impossible. Here is one forester's description:

To correctly measure the DBH of a tree, one must locate the ground, a point 4-1/2 feet above it on the bole, and finally the calipers or diameter tape. This is so simple a procedure that all seems hard to apply. Many of us have missed too many boats, it is agreed, but it is also a fact, that S. E. Alaska as a whole has rather a weird appearance.

The man with the calipers in D.8 must be a man of courage and resourcefulness. He must be able to climb great heights on slender roots; he must cling with his knees to the bark of trees and jump 12 feet from DBH to the ground. He must exercise judgment and know where the ground is. He must be able to land from great heights with one foot on a down log and the other extending through it three feet, retaining the calipers in one hand and the scribe in the other, and a smile on his lips; all the while repeating aloud the diameter obtained so the tallyman will finally get it. He must know that moss covers abysmal caverns, and how to fall easily on his face in the mud when slipping from a log with only devil's club to grab. He must learn to walk mostly on his knees and be able to pull himself up out of slimy rock-strewn chasms hand over hand on a devil's club.

The tallyman must be a man of great judgment and patience. He must be able to stand poised on one foot on a slippery log with no-see-ums in each ear while receiving diameters from loft. He must be able to pick diameters from streams of adjectives heard in anguish from the line of battle. He must know, as a gymnastic teacher does, the little touches necessary to land a man properly on his stomach when falling from DBH in awkward positions. He must be able to jump from rotten log to mossy rock with eyes glued to note book, and without hesitation or oaths tally the numbers as they come, even while hysterical, cold and wet and full of devil's club thorns,—and when no-see-ums are exploring the tonsils.

If there were any known ground and the trees grew anywhere near it, DBH could be reached on stilts or with a step ladder, and foresters in Alaska wouldn't have to visit the States so often to recuperate. [22]

Another major problem of the national forest was "sporting women." Prostitution flourished on the Alaska frontier, and policies ranged from setting up restricted areas, as in Ketchikan and Juneau, to having a highly permissive society, as at Tenakee. George Peterson, whose ranger district included Tenakee, had many difficulties with the whores. A typical diary entry reads:

Dec. 10, 1919

Went to Mr. Flory to see U.S. Attorney in regard to sport. Ladies and bootleggers at Tenakee.

Dec. 11, 1919

Told Mr. Ed. Snyder, Tom Turke, Lewis Thompson and could not find Nels Pherson that they would have to clean up other place of sporting ladies dives and bootleggers. Ed Snyder said that it was up to the Marshal. And I told them it was not up to Marshal but up to property holders or that we would cancel their permits and left Tenakee at 1:30 P.M. Arrived at Chatham at 5:30 P.M. Very rough out in Chatham straits.

One problem that occurred was that some madams tried to take up land in order to practice their profession. Though the Forest Service had regulations regarding a great number of special-use permits, it had none to fit this type of goods and services. The result was what the Service emphatically called "nuisance trespass." One woman tried to take advantage of the Forest Homestead Act. George Drake recalled:

We had a ranger at Juneau named Babbitt who came into the Forest Service in the early days....When he asked his supervisor what his job was, he was told to go out and range....I had a tough time to get Babbitt to submit reports, especially June 11 reports. We had a flood of applications for June 11 claims come in from several fishermen around Auke Bay—no report from Babbitt so I set a deadline. In came a single page report with all the claims listed. The substance of the report was as follows:

"These applicants are fishermen who were attracted to Auke Bay by Mrs. X [a well known lady of easy virtue], who was living there. Mrs. X has moved back to Juneau and there is no more interest. The Gordian Knot is cut. I recommend these applications be cancelled and the cases closed." [23]

The most embarrassing problems in regard to "sporting women" came in Anchorage. In 1914 the federal government began work on the Alaska Railroad. At Ship Creek, on Knik Arm, a construction site was set up and a townsite laid out by the General Land Office, with Andrew Christensen in charge. Lots were sold under Alaska townsite regulations, which provided, among other things, that lots and payments for them would be forfeited if "used for gambling, prostitution, or any other unlawful purpose."

With the construction work came a large number of pimps, gamblers, and sporting women. They formerly had occupied land at the mouth of Ship Creek, along with others, before the Alaska Engineering Commission formally took possession of the area. The commission notified the trespassers that all available land at the mouth of Ship Creek would be needed for headquarters and railroad terminal purposes and ordered the trespassers to move. Meanwhile, the new city of Anchorage had been located on a flat bench above the valley, at the mouth of the creek, and those with legitimate occupations purchased lots and began improvements. The first sale of lots was in mid-July 1915.

The question arose as to the prostitutes, who, under terms of the sale of lots, were barred from purchase. Deputy Supervisor T. M. Hunt was emphatic that under no circumstances would they be allowed to occupy national forest land. (The Forest Service still maintained administrative control of the area inside of the Ship Creek withdrawal, but outside the specific Anchorage elimination.) This left the question up to Christensen. The women had to be moved but could not be admitted to Anchorage. The group reached no solution for the moment and left it temporarily until the commission had need of the land they occupied. Hunt, meanwhile, plotted a free campground outside the Anchorage elimination to take care of the transient workers who followed construction and could not be expected to purchase lots.

Hunt soon left Anchorage for another section of the national forest. During his absence Christensen took advantage of the situation. In conjunction with the deputy U.S. marshal, who himself owned a lot on which a gambling house was located and who lived with a lady bootlegger not his wife, Christensen had a blind street built to the area adjacent to the campground. He permitted the sporting women to set up their establishments there, on land under jurisdiction of the Forest Service.

Henry Graves, with E. A. Sherman and W. G. Weigle, visited the red-light district in 1915. It had been named "Hunt's Addition" or "Huntsville." Graves was furious, but Christensen thought it solved their problem. Deputy Marshal Wardell assured Graves that his office would police and maintain order in the two areas and that proper sanitation would be maintained by two doctors, one a public health officer. Graves protested strongly, but the situation remained during the fall and winter.

In July 1916 the Alaska Engineering Commission ordered the area vacated, so that the land could be surveyed into lots and sold. All persons occupying the campground and the lots where the prostitutes had their cribs were ordered out before October 1. The women sold their houses, the buildings were torn down, and practically all the women left the area, some going to Seattle, some to other parts of Alaska. The Forest Service considered the problem solved. In early fall, however, word was quietly passed to the scattered women that they could return. It is not known who passed the word, but it was evident that those in charge of the complicated administrative structure in Anchorage knew of the invitation. Hunt knew nothing of the matter, nor did the local ranger.

This time an area under Forest Service jurisdiction was openly selected as the red-light district. Two streets a block or so long, with twenty-five lots, were plotted. This was immediately south of the area recently vacated and close to the south boundary of the reservation, beyond which the land had been taken up by homesteaders. By November 1916 there was an established settlement, with houses going up, community wells, and plank sidewalks. There were no telephones, but an electric signaling system had been set up connecting each house with the railway station and restaurant. Lots were distributed among the women at a public drawing. There were about sixty houses in all, most of them cribs but two of substantial size.

When Hunt discovered the plot, the Forest Service was faced with administrative control of a large red-light district. Though innocent as a party to the condition, it could be subject to public criticism. The problem of removing the district as a nuisance trespass was also difficult. Navigation to Anchorage had closed in November, and it was impossible to send the women out overland. Drastic action by the government in trying to remove them by force would result in fights with the unsavory elements and, at best, would lead to unfavorable publicity. The U.S. deputy marshals in the area were allies of the pimps and prostitutes and would be of no aid. Christensen admitted that Hunt had "caught him with the goods" but offered no remedy.

Weigle and Charles Flory, chief of operations for District 6, discussed the matter. They finally agreed that the Forest Service would formally and immediately renounce all jurisdiction over the withdrawal area of the original Ship Creek Townsite and ask for its elimination from the forest by presidential proclamation. There was little timber in the area and little land available for homestead purposes. Elimination of the specific nuisance area would be interpreted as a slap at Christensen and thus the Alaska Engineering Commission and General Land Office; but elimination of the entire area from the forest would not be so interpreted and thus could be handled as regular departmental procedure. The Forest Service could "quietly withdraw from the scene without scandal." The Forest Service renounced jurisdiction over the area, but not until 1919, with the Ship Creek elimination, was the Service free from this embarrassment. [24]

Boundary Work

Boundary work was a major task of the Forest Service during the period 1910-1920. During the spring of 1909, Secretary of the Interior Ballinger and Secretary of Agriculture Wilson agreed to classify land with in the national forests and remove agricultural land. Generally speaking, the lands to remain within the forests would include timbered land, land necessary to check erosion, cutover or partly timbered land more valuable for timber production than agriculture, and land above the timberline in the mountains. Lands not timbered and not in the above categories would be eliminated from the forests. In 1912 appropriations were made for classification of the lands within the forests and the U.S. Bureau of Soils did the work. [25]

Langille, in laying out the boundaries of the Alaskan national forests, had been working on unsurveyed lands. Rather than the usual legal descriptions by township, range, and section, he had established easily recognized boundaries such as watersheds, crests of mountain ranges, streams, mountain ridges, and latitude and longitude lines. There was, therefore, a considerable amount of tundra, barren mountain ridges, and some agricultural land within the forest boundaries. The task, particularly in the Chugach, was to reduce these areas and at the same time protect national forest objectives. A second aim was to eliminate areas around villages and towns, so that they could grow.

Two eliminations were made from the Chugach during Langille's administration. The first was the 12,800-acre elimination by presidential proclamation in Controller Bay, already mentioned. Also, near Cordova, a townsite of Nelson Bay was eliminated from the national forest by congressional action. A town and railroad terminal were projected, but neither materialized. [26]

In a report on the Chugach in early 1911, Langille stated that the national forest had no agricultural land worth note, save for a few points on Cook Inlet and Knik Arm. Areas of tillable land, he noted, existed in isolated areas of a few acres each. There was no market for the produce, and the hardy vegetables that might be raised could be imported more cheaply than they could be grown. The areas of land were not large enough or contiguous enough to permit close settlement and development of villages and schools. Subsistence agriculture, as a supplement to fishing, was probably the greatest development that could be expected. Such agricultural land as was available could be listed under the Forest Homestead Act of June 11, 1906.

Langille expanded on this in a letter in May. There was, he wrote, some agricultural land at Knik Arm that might be eliminated from the forest. There was also some agricultural land around Tustumena Lake and the Kenai River. The cost of clearing land, however, was $800 per acre, the season was short, and agriculture did not have a great future. Langille also pointed out the unique value of the Kenai as a wildlife and hunting preserve, writing, "There is room for the frontier settler and fishermen on the shore land; there let them abide in peace and prosper, but keep out the fire and wanton game destroyers."

On the 1909 addition to the Chugach, from Copper River to Cape Suckling, then under attack, he pointed out that it had been made to preserve the timberlands. "If this action ultimately prevented non-resident claimants from fraudulently acquiring coal lands and kept a guileless public from investing huge sums in the many claims that will never produce coal, this work was well done." But all this had no bearing on the real reason for the addition. "It was alone to control the use and prevent wasteful destruction of the limited supply of not too good, but most necessary timber and hold it available for future citizens and operators."

Langille's formal recommendations included eliminations along the northern boundary of the Chugach National Forest, including mountains above timberline, tundra, and glaciers. He also recommended eliminations around some of the towns, such as Cordova, and enlargement of the Controller Bay elimination to include more of the mudflats and tidelands in that vicinity. He also suggested some additions to the forest; these included the southern shore of the Kenai Peninsula from near Seward to the head of Kachemak Bay, Kayak Island, Shuyak Island, and Marmot Island.

In the Tongass, Langille reported on a petition for elimination of the settlement of Hyder at the head of Portland Canal. There had been a mining boom at Stewart, located at the head of the canal on the Canadian side, and a rush to the area began in 1909. On the American side, a man named Dan Lindeborg had patented a homestead in 1905. Americans joined the rush, and a settlement named Hyder grew up near the Lindeborg homestead. When Langille visited the area in the winter of 1910, a settlement had grown up of fifteen to twenty tents, three or four rough lumber buildings, a house scow, and four cabins—all on the Lindeborg claim. Plans were made to erect buildings on the pilings. Langille was critical of the Alaska Boundary Commission for its decision on the boundary line. It ignored, he wrote, the Russian Ukase of 1821 and the English-Russian convention of 1824-1825 in drawing the boundary. The decision, wrote Langille, gave the Bear Creek Valley with its mineral resources to "our Canadian cousins," leaving to the United States barren granite. However, Langille recommended building a wagon road up the Salmon River to divert business to the United States. For the present, he wrote, the tide-flats and the Lindeborg homestead would be sufficient land for the mining settlement, and he recommended that the proposed elimination be rejected. [27]

Intensive boundary work began in 1913, following the provision of funds by Congress. The Forest Service was under particular attack at this time from the Senate Committee on Territories. Graves asked George Cecil, district forester of District 6, for all available material on Alaska, including commercial timber areas, maps, reason for establishment of boundaries, probable alienation of lands if they had not become national forest, and present and prospective uses of the forests. Cecil replied that there were large untimbered areas in the west Kenai, both muskeg and areas burned by prospectors in 1898. The west Chugach, west of the Valdez trail in the mountains, had never been explored and had no inhabitants. He estimated the total volume of timber on the Chugach at 8 billion feet of commercial timber. These boundaries had been set up on the basis of natural features, so well defined that they could not be mistaken. The addition in the Kenai of February 23, 1909, had been planned to include the south coast, but commercial interests in Seward objected, so the crest of the range to Kachemak Bay was used. It should have included the south coast, Cecil reported, since there was more timber south of Kachemak Bay than to the north. Two thousand acres had been located near Katalla with the use of soldiers' additional homestead scrip, and about 1,000 acres near Seward. More scrip would have been used near Knik Arm if the national forests had not been created. He reported some agricultural lands near Knik Arm and in the Cook Inlet area. Finally, he suggested that the Forest Service reexamine timber values in the Susitna, Matanuska, and Chitina areas for a possible new national forest. [28]

James B. Adams of the Washington Office travelled to Alaska in 1913 in company with George Cecil and E. H. Clapp. They travelled over the right-of-way of the Alaska Northern Railroad to the east end of Kenai Lake, explored the Kenai area, examined Prince William Sound, and then returned to the Panhandle. Clapp recommended elimination of an area east of Seward and another in the Tustumena Lake area. He also recommended elimination of the Elllsworth Glacier and Chugach Mountains, the lower Copper River, the lower Kenai, the Susitna, Matanuska, and Chitina areas, and also Afognak Island. Clapp recommended additions to the Tongass. These included reannexation of the Kasaan elimination of 1907, an addition of the Mansfield Peninsula on the northern end of Admiralty Island, the area on the mainland to the west of Lynn Canal, as far as the mountains, and the area to the north of Icy Strait and Cross Sound, as far north as the Yakutat and Dry Bay additions to the Tongass. [29]

The problems of boundaries were particularly complicated on the Kenai Peninsula, west of the rail line, and in the Cook Inlet area. The nature of the timber was different here from that in the Prince William Sound area and in the Tongass. The yield was sparser, and it was of poor quality—comparable with that of the Rocky Mountain West rather than the Pacific Northwest. This relative lack of timber was a favorite reason given by Delegate Wickersham and Senator Walsh for their efforts to eliminate the Chugach National Forest.

The boundary examinations, moreover, took place in an era of economic and social change. In 1915 the federal government got into the business of railroad building and set up the Alaska Engineering Commission. Andrew Christensen, formerly with the General Land Office, became head of its Land and Industrial Department, a promotional agency for encouraging settlers to come into the area. It was similar to the land boards of the transcontinental railroads. The work of Christensen's department was to propagandize the values of the area for homesteads. His efforts to establish a permanent agricultural colony were largely unsuccessful, but he did bring a nucleus of settlement into the Matanuska Valley and along Knik Arm, which created more pressure for elimination of national forest lands in that region. Christensen's constant barrage of propaganda about agricultural possibilities stimulated the Forest Service's land classification work, though it had been authorized as early as 1912.

To aid in this classification effort, the U.S. Bureau of Soils sent Hugh H. Bennett to Alaska. Bennett, who would later gain much fame as a soil conservationist, made two trips, one in 1914 and another in 1916. On the first trip Bennett was accompanied by Thomas D. Rice, a fellow employee of the Bureau of Soils. They began their soil reconnaissance along Knik Arm, travelled up the Susitna and Matanuska valleys, visited the Kenai Peninsula, and concluded with studies of the soils of interior Alaska and adjacent areas of Canada. They worked closely with the Forest Service, the Alaska Engineering Commission, and the Alaska Agricultural Extension Station.

In 1916 Bennett made a detailed reconnaissance of the Kenai Peninsula and the Prince William Sound area. He traveled through Cook Inlet with Keith McCullagh of the Forest Service on the launch Wilhelmina, hiked through the interior of the Kenai with Arthur Ringland, examined the soils work that T. M. Hunt and Asher Ireland were doing between East Foreland and Kachemak Bay, and took Lage Wernstedt to Afognak Island for topographical mapping. Bennett's reports are valuable historical documents, not only for the soil maps but also for descriptions of other aspects of the country—its timber resources, game and fish, hunting practices, and scenic and recreational values. [30]

The net effect of Bennett's soil studies and land classification work was to give the Forest Service more reliable information about agricultural possibilities. Thus, eliminations could be made on a sound basis, rather than in response to Christensen's propaganda.

The Forest Service conducted much other field work between 1913 and 1918 in an effort to redraw boundaries of the Chugach National Forest. H. W. Fish made a reconnaissance of the Cape Suckling area in 1913. He found good stands of spruce and recommended additions to that far southeastern part of the forest. [31] Asher Ireland, a dry, humorous, laconic man from Oregon's Umpqua National Forest, came to the forest in 1916 to further the land classification effort. He recommended a small addition of 8,641 acres of land on the Resurrection River, adjacent to the southern border of the Chugach, near Seward, as being of value for both timber and protective cover. [32] The area contained 42 million feet of spruce and hemlock and was, in Ireland's opinion, "the best body of timber in southwestern Alaska." The tract was within the Land Office withdrawal for Seward, but Ireland felt that the land was needed to prevent the timber from falling into the hands of speculators. Weigle and Cecil both endorsed this proposal.

Ireland and T. M. Hunt also examined an area to the north, between Indian Creek and Bird Creek and beyond the Knik River and Knik Arm. They found an area of great fire danger along the right-of-way clearing for the railroad and believed that it should be retained within the national forest. The soil values were as yet untested, and the timber was of potential value for the railroad and building. "The seemingly poorer stands of today may become the valuable stands of tomorrow," they noted. Later, with intensive classification, the area might be eliminated. They thought that such classification might take place when the Alaska Railroad's free-cutting permit expired on July 1, 1919. Cecil and Weigle, however, believed that the area might be eliminated because of the low timber values. [33] Charles Flory, to the contrary, felt that the area should be retained for pulp and timber needs. [34] Weigle favored an elimination from Knik Arm to Potter Creek and along the Knik River, as well as the area already homesteaded. [35] He favored a new survey of the Matanuska and Susitna rivers for possible reserves, as well as reserving the timber along Indian, Rainbow, and McHugh creeks. Ireland also examined the land to the head of Knik Arm, between the Matanuska and the Knik rivers, an area of 169,240 acres. He found the land to be primarily agricultural in nature, with settlement on the increase, and recommended that the area not be included in the national forest. [36]

To the southwest, a major area of controversy was Kachemak Bay and the coastland up to Kenai. Lage Wernstedt and H. Nilsson examined the area in 1916 and recommended elimination of a three-mile-wide coastal strip from East Foreland to the head of Kachemak Bay, totalling 205,670 acres. The area was timbered with spruce, birch, and aspen, with a volume of 80 million feet of spruce suitable for sawtimber and piling, and 315,000 cords of wood. The area had been heavily culled, however, and tie timber was not of the best quality. Bennett and Rice had classified the lands as having agricultural possibilities, and Wernstedt and Nilsson recommended its elimination from the forest. [37] George Cecil also recommended its elimination. [38] In all, 581,274 acres in the Chugach were classified as agricultural land by August 1920. These were largely in the Ship Creek, Turnagain Arm, and Kachemak Bay areas. [39]

|

| The agricultural prospects of Alaska were hotly debated and had some effect on eliminations from the Chugach National Forest. Above is a Matanuska farm photographed in 1941. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The Forest Service also made studies regarding eliminations around towns and villages in both the Chugach and Tongass national forests. These involved increasing the areas of village eliminations and making the eliminations rectangular to conform with the existing system of survey.

The series of eliminations made between 1915 and 1919 reduced the total area of the Chugach from 11,268,140 to 5,232,250 acres. The two major eliminations were those made in 1915, reducing the forest by 5,735,235 acres of untimbered land, and in 1917, involving Ship Creek and Kachemak Bay, an area of about 300,000 acres. The other eliminations included townsite areas around Ship Creek, Kenai, and Potter. [40]

On the Tongass National Forest, a number of small eliminations were made by executive order. These included bird reservations, Indian reservations, dock sites, the Old Kasaan National Monument, and eliminations at Petersburg, Craig, and Ketchikan. [41] Of more importance than the eliminations were Asher Ireland's reconnaissance at Lituya Bay. He reported heavy stands of spruce and hemlock averaging 15,000 board feet to the acre. He found one stand of pure spruce, the best in Alaska, with a volume of 200 million feet. Ireland estimated the total stand of all timber in this area at 5 billion feet. There were no towns or settlements, and he recommended addition of the area to the national forest. During World War I the military withdrew the Lituya Bay area as an important source of spruce for airplane construction. [42]

|

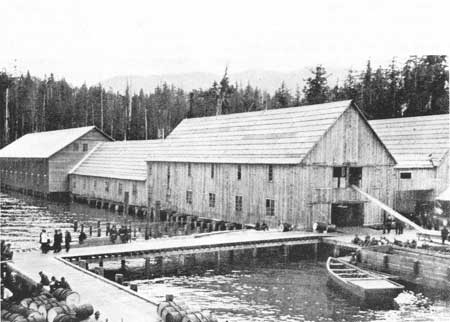

| Some lumber was exported from Alaska during the years before World War I, but even more had to be imported from the Pacific Northwest. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Timber Sales

Timber sale activity in Alaska increased during Weigle's years as supervisor. Wartime demands for fish increased the sale of timber for piling, fish boxes, and construction timber. Some Sitka spruce in Alaska was logged for airplane construction, and a mill was established at Craig for cutting it. The Alaska Railroad also used several million feet of Forest Service timber per year under a free-use agreement. The amounts varied as follows: 1916, 2,267,000 board feet; 1917, 7,358,000; 1918, 5,576,000; 1919, 5,758,000; and 1920, 4,067,000. [43] The total national forest cut grew from 9 million board feet in 1909 to 20 million feet in 1920, with a large amount for free use by the railroad and others.

Cable logging had largely replaced handlogging by the 1920s, and stands of spruce near the shore were diminished in most areas. "Most of the timber accessible to tidewater," Kan Smith wrote, "has been culled over at least once, so that the remaining stands do not make practical hand logging areas....The hand loggers as a class invariably waste as much timber as they get into a raft." Logs were usually cut by contractors, many of them Indians, for mills. They were scaled in the raft by scalers using large calipers. [44]