|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 5

Team Management: Flory, Heintzleman, Merritt, 1919-1937

December 4, 1930

Reference is made to your letter relative to butter received in the lost Seattle purchase. The brand received here is marked Montequilla Marc. Brookfield. Was probably made some years ago for export to Mexico but the Mexican government refused it. I believe it is butter, or would prove to be on analysis, but it has been removed from the cow for too many years. There are rust spots through and on it, it does not taste very good, and has a queer grainy effect when placed in the mouth. It looks more like tallow than butter but this is probably an optical illusion. Never saw butter like this before.

Chas. Burdick to R. A. Zeller, quoted in

Sourdough Notes, October 1, 1951

Politics of Forestry: The

1920s

The Taft and Wilson administrations had been marked by political battles over forestry and conservation—battles in which Alaska was prominently involved. This was also the case for the first three years of the Harding administration. Harding chose Albert B. Fall of New Mexico to be his secretary of the interior. Fall had as a goal the transfer of the Forest Service to the Department of the Interior. As an opening wedge, he testified in 1922 before the Senate Committee on Territories in favor of transferring the Forest Service in Alaska to the Interior Department. This would, in his opinion, make mining and homesteading in the territory much simpler and would at the same time allow forest use. The project found some friends in Congress, particularly in Fall's successor in the Senate, Holm O. Bursom, and from George Curry, a former congressman and governor of New Mexico, now Bursom's "private secretary." However, it was characterized by the American Forestry Association as a land grab. Pinchot used his considerable political influence against it, as did Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace. Dan A. Sutherland, Alaska's delegate to Congress, also opposed the transfer. This controversy was probably a factor in Harding's decision to visit Alaska in 1923. The president became a convert to Forest Service views while in Alaska, and in a Seattle speech he strongly supported Forest Service management and advocated development of a pulp industry in Alaska. [1] The political threat to Alaska's forests disappeared during the 1920s, and it was in general a period of quiet but steady progress.

Calvin Coolidge, Harding's successor, was pledged to economy in government and to noninterference with the existing governmental departments. He provided no leadership to conservation, but he offered no obstacles. Herbert Hoover was more knowledgeable regarding resource administration. His philosophy involved businesslike efficiency, scientific management, cooperation with the states, and decentralized administration. These were not antithetical to the Forest Service objectives. Hoover was unfortunate in the time in which he served, however, spending much of his energy explaining and dealing with the economic depression.

In Congress there emerged a strong leadership for forestry and conservation. Senator Charles L. McNary of Oregon, with his strong personal interest in forestry, his legislative skill, and his working alliance with E. T. Allen, was the notable leader. Others included Louis C. Cramton and Arthur H. Vandenberg of Michigan, Henrik Shipstead of Minnesota, and George W. Norris of Nebraska. The decade witnessed important legislation, especially in the area of state and federal cooperation. The Clarke-McNary Act, the General Exchange Act, the McSweeney-McNary Act, the Knutson-Vandenberg Act, and the Copeland Report were among the accomplishments.

|

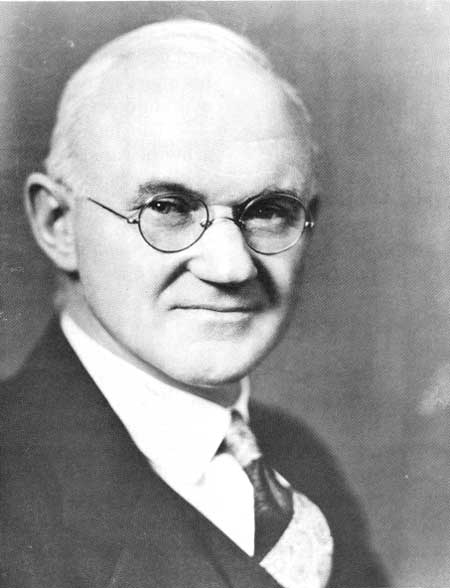

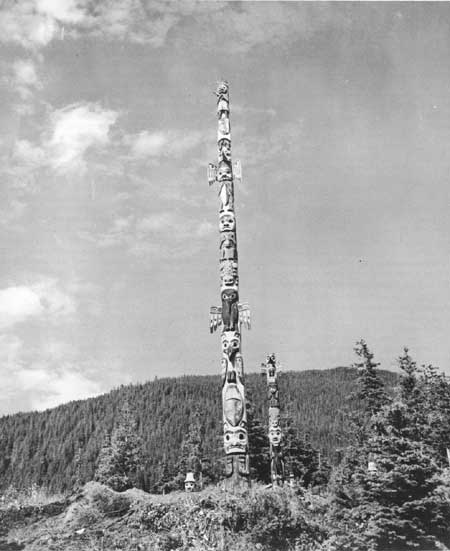

| William B. Greeley, chief from 1920 to 1928, served during an era of relatively "good feelings" and built a record of solid accomplishments. He traveled to Alaska and made a firsthand examination of its forests. (U.S. Forest Service) |

|

| Forest Service Chief William B. Greeley visited the Tongass National Forest in 1921. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The two chief foresters of the period, William B. Greeley (1920-1928) and Robert Y. Stuart (1928-1933), built substantial records. Greeley was a graduate of Yale who came to Washington after service in California and Montana. A capable, competent man who had earned the respect of the lumber industry, he had a good relationship with both the administration and the Congress. He rejected Graves's idea of federal regulation of private cutting, preferring voluntary cooperation. He gave high priority to fire control—the result of his personal experience in the big fire of 1910 in Montana. He continued Grave's emphasis on recreation in the national forests, which involved both road building and reserving of primitive areas. Scientific research was advanced greatly during his term as chief. In all these areas, except the regulation issue, he followed the views of his predecessor. Graves had been denied full achievement of his goals by political hostility. Greeley, on the other hand, took advantage of the era of good feelings in politics to get through the legislation he wanted. Greeley faced minor clashes with the grazing interests over the matter of fees, and there was some infighting with the National Park Service in recreational areas, but his was an administration of substantial accomplishments. He retired from the Forest Service in 1928. [2]

|

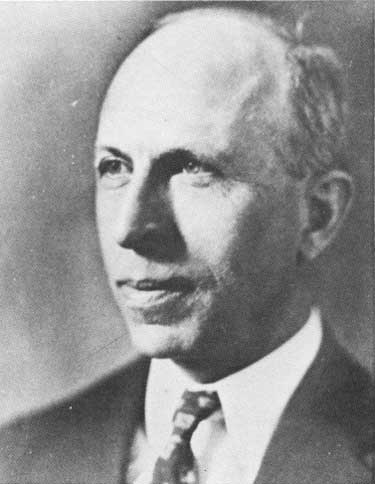

| Robert Y. Stuart, chief of the Forest Service from 1928 until his death in 1933, continued the policies of his predecessor, William B. Greeley. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Robert Y. Stuart, successor to Greeley, was another Yale man. He entered the Forest Service in 1906, served until the United States entered World War I, became a major in the 20th (Forest) Engineers, and returned to the Forest Service in 1920. Shortly thereafter, he went to Pennsylvania to serve as assistant commissioner of forestry; Pinchot was commissioner. When Pinchot was elected governor of Pennsylvania in 1922, Stuart was advanced to commissioner and then to secretary of forests and waters, when the name of the state agency was changed. Stuart returned to the Forest Service when Pinchot's term as governor expired in 1927, and in 1928 he became chief. During Stuart's administration, the important legislative accomplishments of the Greeley era were continued; he made no real break with the Greeley policies. In the latter part of his term, Stuart pushed for emergency relief work on the national forests in order to carry out projects primarily in construction and recreational areas. He died in office on October 23, 1933.

|

| Ferdinand A. Silcox, yet another Yale forester, was chief of the Forest Service from 1933 until 1939. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Stuart was succeeded as chief forester by Georgia-born Ferdinand A. Silcox. After graduating from Yale, he went into the Forest Service, serving as district forester in Missoula. He served in World War I and then went into labor management for the government. He was called back from his assignment to be chief forester. Silcox was intensely sympathetic with and loyal to the New Deal—so sympathetic that Ickes sought to have him transferred to the Interior Department. He favored public ownership and management, public cooperation, and public regulation. In addition to the existing relief and reform work during his term, several new pieces of legislation were passed, including the Norris-Doxey Cooperative Farm Forestry Act. He supervised the Shelterbelt Project in the prairie states, ordered a study of the western range, and established a timber salvage project after the great blow-down of 1938 in New England. Silcox favored federal regulation of cutting and devoted much time to working for this, until his death in 1939. [3]

In Alaska, the 1920s were a period of transition for the Forest Service. Recommendations for creation of a separate administrative district appear all through the inspection reports of the Weigle administration. Graves favored the change, and in 1919 the area was divorced from the Portland office and made District 8, later to become Region 10. Part of the pressure came from within the Forest Service, but part of it came from outside demands for further decentralization of the agency. [4] With this transition, Charles H. Flory, who had succeeded Weigle as supervisor in 1919, now became Alaska's first district forester.

The Alaska District had a curious relationship with the Washington Office. Chief Forester Greeley traveled to Alaska and made a firsthand examination of its forests. Early annual reports are filled with plans for Alaska, particularly plans for pulp mills that did not materialize. Meanwhile, Alaska's national forests were underfinanced and understaffed; transfers of personnel out of the forest were infrequent. It was the most neglected of all districts, but there were many who liked the Alaskan way of life and completed long terms of service there.

|

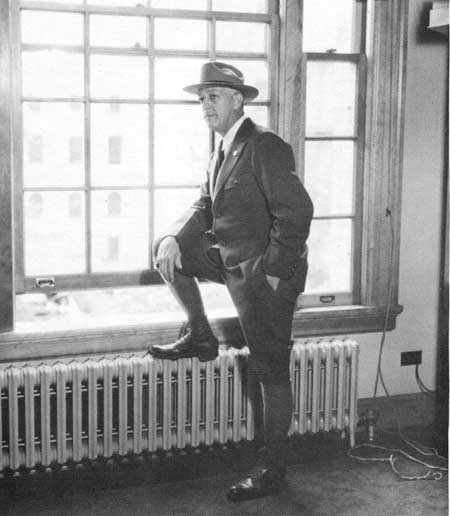

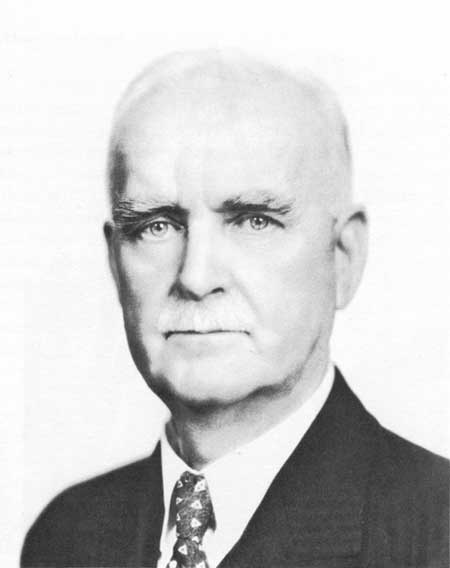

| Charles H. Flory, district and regional forester from 1919 until 1937. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Charles H. Flory, the first district forester in Alaska, had a curious career. He was a Yale graduate who went out to District 6 and served as chief of operations in Portland until coming to Alaska in 1919. His title was superintendent of Alaska forests until 1921, when Alaska was made a separate district, District 8. Though he had been a good lieutenant for George Cecil, he proved to be a poor captain. He was too imaginative and had too low a boiling point to be an outstanding administrator. He had many sideline activities that took time away from his regular duties, and his health was not robust. He was generally looked upon as a man of great qualities that were not fully realized. [5]

Flory had two close and able associates. Melvin L. Merritt, assistant district forester in charge of operations, was the very model of a career forester. Born in Iowa in 1870, he became a professor of horticulture at Iowa State University. After deciding that he should devote his life to public service, he went to the Philippines as a member of the Philippine Bureau of Forestry in 1905. He returned to the states in 1909, served in District 6 in various capacities, and then came to Alaska at Flory's request in 1921. After a long tenure in Alaska, he returned to Portland in 1934 and was assistant regional forester in the Pacific Northwest for the remainder of his Forest Service career. A man of deep religious convictions, he usually taught Sunday school in the communities where he served. In Juneau he also served several elected terms on the school board. Merritt was a hardworking, competent, and conscientious public official. [6]

The second associate was B. Frank Heintzleman, born in Pennsylvania in 1888 and educated at the Pennsylvania State Forest Academy and Yale. He served with the Forest Service in the Pacific Northwest for some years and then went to Alaska in 1918 as a deputy forest supervisor. He was attracted to Alaska from the first, and he dedicated his life to its affairs. Heintzleman was short in stature, tremendously energetic, an able public speaker, and devoted to community affairs. He gave much time to the promotion of timber sales, to waterpower surveys, and to the establishment of pulp cutting areas, but, he was also interested in the recreational potential of the area, particularly in fishing and tourism. A lifetime bachelor, he loved social life and the amenities. He was a poor administrator by technical standards, somewhat hostile to organized labor and politically conservative, an inept politician, and occasionally indiscreet in speech and writing. But his energy, intelligence, and professional ability greatly overshadowed some of his human weaknesses. [7]

The decade of the 1920s in Alaska was one of quiet growth. Alaska was not directly involved in the major controversies of the period. Since the forestland was nearly all government owned, the question of federal regulation of cutting did not affect the area. Neither did the controversies over grazing. Conflict between Forest Service and Park Service over recreation areas did not greatly affect Alaska; the movement for the Glacier Bay National Monument had Forest Service support. The General Land Office and the Forest Service reached accommodations over boundaries during the early part of the decade.

There were efforts during this period to increase interagency cooperation in Alaska through both formal and informal methods. One aspect of this was the establishment of formal commissions of the various bureaus and departments. The Forest Service rejected both Franklin Lane's idea of a development board to take the place of the established agencies and Albert Fall's idea of having the Department of the Interior take over all functions. However, the Forest Service did take part in a number of ventures.

In April 1920 an Interdepartmental Alaska Advisory Board was set up, consisting of members of the various federal departments with interests in Alaska. The board recommended establishment of an Interdepartmental Alaska Committee to coordinate the work of the various departments in the field. E. A. Sherman of the Forest Service strongly opposed establishment of the committee, but it was set up nevertheless in 1920. [8] It had a large membership, and Charles Flory was the Forest Service representative. Greeley spoke on the need for cooperation, pointing out that in fur farming there were three agencies involved: the Forest Service, the Biological Survey (in the Aleutians), and the General Land Office. There was need for a coordinated policy. In settlement there was no conflict, but the General Land Office was too inefficient. The Land Office in Alaska was the office of record, but the other steps—allowance of entry, acceptance of final proof, survey, issuance of certificate, and final patent—all had to go through Washington. The Land Office had three branches—the Land Office proper, with its registers and receivers, the surveyor general, and the Field Division in charge of inspection—and all operated independently. [9]

The Alaska Committee was abolished by the president on April 1, 1922. It probably had no great effect, but it may have helped to get Flory together with the Land Office on boundary matters.

In 1930 an Alaska Commission was set up to coordinate activities of the Department of Agriculture, Department of Commerce, and the Land Office in Alaska. Charles Flory served as chairman of the commission for a time. He was listed in the Forest Service Directory as ex-officio commissioner for the Department of Agriculture for Alaska, as well as regional forester. (All districts were renamed regions in 1930; all district foresters became regional foresters.) Flory accepted the commission post feeling that it would not interfere with his regular duties. From a study of inspection reports, however, it is evident that the job did take Flory away from his office a great deal, constituted about half of his work load, and may have contributed to his reputation as a weak administrator. [10]

Of more importance than any of these things, however, was Forest Service membership in the Alaska Game Commission, which was established by act of Congress in 1925. This participation helped to coordinate the work of the Forest Service and the Fish and Wildlife Service in regard to fish and game management. W. A. Chipperfield, as a member of the commission, gave outstanding service. [11]

The Politics of Conservation

and the 1930s

The 1930s and the New Deal marked the revival of conservation as a crusade. Aside from the Republican Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt probably had more firsthand experience with forestry than any other president. He had operated a tree farm at Hyde Park, New York, and had a practical knowledge of forestry in all its technical and economic aspects. He had served in the New York legislature as chairman of the Senate Committee on Forestry, and as governor he had pushed a program for reforesting and managing abandoned farmlands. Roosevelt's presidential programs took many forms. They involved the emergency conservation work of the early 1930s and later the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), with its philosophy of using relief funds both to rehabilitate men and for socially desirable conservation work. The Shelterbelt Project, the NRA Forest Conservation Code, and the Taylor Grazing Act were other monuments to his administration. He pushed creation of national parks and monuments, and with the Reorganization Act of 1933 put all national monuments under the Department of the Interior. In the national forests, primitive areas were established and fish and game sanctuaries set up.

Roosevelt had his personal quirks and idiosyncracies in conservation. Some advisors outside of the ordinary chain of command influenced his decisions, as did Rex Beach in regard to mining in the Glacier Bay National Monument, John Holzworth with the proposed Admiralty Island National Monument, and Irving Brant regarding the Mount Olympus National Monument. He alternately pleased and tormented Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes, probably relying on him more for advice than on any other single cabinet officer but frustrating Ickes's desire to transfer the Forest Service to the Interior Department. He had a weakness for parkways—possibly because of his physical infirmity—and probably had more of them built than was desirable.

Roosevelt surrounded himself with outstanding men. Ickes, a Bull Moose Republican turned Democrat, was one of the strong men in the cabinet. Irascible, honest, suspicious, committed to democracy and minority-group rights, and hungry for power, he was the most colorful of the Roosevelt group. Henry A. Wallace, as secretary of agriculture, was a quietly capable individual. The son of Henry C. Wallace, who had served so well in Harding's cabinet, he was very different from his hard-drinking, somewhat flamboyant father. Inclined to be mystical in beliefs, sometimes openly radical in his thinking, he was an odd combination of qualities.

Congress continued its good bipartisan legislative record. Senator Charles McNary played a responsible role as minority leader, and other helpful pieces of legislation were passed. It was a period of great progress also in regard to state forestry and to forest industry. Though the National Industrial Recovery Act was invalidated by the Supreme Court in 1935, private owners continued its conservation features. States, meanwhile, established good forestry practices and enlarged their park systems through purchases of land. [12]

Alaska had been out of the mainstream of forestry development until the Great Depression; after 1933, it was in the middle of things. The Depression placed special responsibility on the Forest Service, which was put in charge of all emergency conservation work and later of the CCC program in the entire territory. The addition of a large area to Glacier Bay National Monument involved the Forest Service directly, as did Ickes's machinations regarding Admiralty Island and Indian claims. The Forest Service played a direct part in the development of a forest fire program for the interior of Alaska, and, by the end of the decade, it was deeply involved in matters of defense. It was a period of planning and of preparation for the approaching shift from custodial to intensive management of the 1940s and 1950s.

|

| President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes were the principal architects of federal conservation policy during the New Deal era. Ickes visited Alaska in 1938. (Roosevelt Library) |

Boundaries

Boundary problems on the Chugach continued after the 1917 eliminations. Associate Forester E. A. Sherman wrote in 1921 that he considered the chief timberland of value to be in the Prince William Sound area and in the area east of 150 degrees of longitude and south of Turnagain Arm. These areas, he wrote, should be retained. North of Turnagain Arm, from the head of the arm to Indian Creek, the values were low. There was some timber near Bird Creek and Indian Greek, but these areas were isolated. Sherman suggested eliminating Turnagain Arm and all the area north of Turnagain Arm and west of 150 degrees of longitude; he also questioned the value of retaining Afognak Island. Answering his letter, Heintzleman favored keeping the "fishhook" from East Foreland to Kasilof River. He felt that the south side of Knik Arm could be eliminated, but not the area south of Turnagain and west of 150 degrees until more was known of the area. [13]

In 1923 efforts were made to reach a final settlement on the boundaries. On the way back from Alaska on the Harding trip, William Greeley conferred with Secretaries Henry G. Wallace and Hubert Work and Land Office Commissioner William Spry on boundaries. The Forest Service was particularly interested in the Icy Straits-Lituya Bay area. The Land Office, on the other hand, wanted eliminations from the Chugach National Forest in the Kenai and the Copper River areas. An agreement was reached that Charles Flory of the Forest Service and George Parks, head of the General Land Office's Field Division in Alaska, would meet and work out boundary adjustments on a give-and-take basis. Parks apparently went on the erroneous assumption that Flory would be given a free hand to make additions in the Tongass, while he would be given a free hand in the Kenai. [14]

The Forest Service carried on investigations in 1924 and 1925. Wellman Holbrook made a reconnaissance of the Chickaloon Flats area and the strip along the coast from East Foreland down to Kenai, recommending its elimination. Melvin Merritt recommended elimination of the Knik Arm area because of its inferior timber, settlement, and fire danger. Chief Greeley was opposed to these eliminations from the forest, but he finally agreed. W. J. McDonald, supervisor of the Chugach, made a trip to Afognak Island and reported favoring retention of this area and adding to the national forest some of the adjacent islands, including Raspberry, Shuyak, Whale, and Marmot. There was an increase in demand for use of the islands. These included a saltery application on Redfox Bay and two fox farms. The Bureau of Fisheries had no objection to Forest Service administration on Afognak, but there was no agreement between the Forest Service and the Commerce Department over administration of fox farm islands. Parks objected to the proposed addition on the ground that the General Land Office had timber sales on Raspberry Island, so the plans for additions were dropped. However, Latouche Island was added, and fox farmers on Wingham and Wooded islets petitioned for annexation by the national forest. Langille had already recommended the addition of Kayak Island. In addition to these, the Orca and Ellamar eliminations were cancelled. Also, at Eyak and Tabulik rectangular eliminations were substituted for circular ones. In the Copper River Delta there were no changes; McDonald and Merritt examined the area and felt it should be held for recreational purposes. These changes were made by proclamation on May 29, 1925, and the boundaries were stabilized. [15]

From time to time, there was some demand that the Anchorage Ranger District, the 1,063,673 acres along the Alaska Railroad, be eliminated. Charles Flory, in a report of February 19, 1931, declared against it. By that time, however, public sentiment had changed. The Forest Service was managing the area not only for its timber values but also in cooperation with the Alaska Game Commission for game and recreational values. George Parks, by now governor and head of the Alaska Commission, favored Forest Service management. [16] There was also some local support for establishing national forests in the interior, particularly around the Susitna River area where John Ballaine was making plans for a birch veneer manufacturing plant. [17] In 1938 Heintzleman recommended an addition for recreational purposes in the Russian River drainage, and he was supported by Ernest Gruening, who was then director of the Office of Territories in the Interior Department. There was need for the addition, Heintzleman said, to reduce fire danger and to check fishing regulations. But the addition never came through. [18]

In the Tongass, a major addition was made to the north of the existing forest. In 1917 Asher Island had made a reconnaissance of the area to the north side of Icy Straits and up as far as Cape Fairweather. He reported good stands of spruce and hemlock and an excellent stand of pure spruce at Lituya Bay. This latter area with withdrawn, on Weigle's request, as a military reservation in 1918. Heintzleman examined the area in 1923, taking with him a group of the Seattle Mountaineers, and was impressed with its recreational as well as economic value. At the time of Harding's visit to Alaska, Wallace, Greeley, and Work conferred on the matter; Greeley urged addition of Lituya Bay, the north side of Icy Strait, the west side of Lynn Canal, and the Mansfield Peninsula to the national forest. [19] In 1924 Flory and Parks conferred on boundaries. The main task was to determine the relative boundaries of the Glacier Bay National Monument, now being planned, and the new national forest area. Meanwhile, on their return from Alaska, Greeley, Leon Kneipp, and E. A. Sherman conferred with officials of the Interior Department. Lituya Bay was restored to the national forest in 1924, and on June 12, 1925, the Icy Straits addition to the Tongass was proclaimed.

There were also numerous small additions and eliminations. These included changing the boundaries in Sitka, Wrangell, Skagway, Ketchikan, Hydaburg, and Juneau from circular to rectangular survey. Later, there were numerous small boundary changes within the national forest. These included a military reservation near Sitka, an administrative site near Petersburg, lighthouse eliminations, and townsite eliminations in Hoonah, Tenakee, Hyder, and Warm Springs Bay. [20]

State of the Region,

1920-1937

During its first years as a separate district of the Forest Service, Alaska was one of many anomalies. As in forestry nationwide, there was a shift from the use of westerners (who had gained their experience in the "University of Hard Knocks") to professionally trained foresters from Yale, Penn State, the University of Washington, and other forestry schools. The old-timers became boatmen, as did George H. Peterson of Sitka, or trail and road construction foremen. The number of personnel increased, both in the field and in the office staff.

The Alaska District was poorly financed. In the Tongass, timber sales were more than the cost of forest administration. Promotion was slow and transfers difficult. There were, consequently, some feelings of frustration and a large staff turnover. Annual leave was hardly sufficient to permit trips to the states, considering the poor transportation. The work schedules were difficult, with long hours in the field. On the other hand, there were compensations. Alaska offered a unique way of life for those who loved the out-of-doors. Some of the problems of the states were lacking, particularly fire (except in the Kenai area) and grazing problems. It was good country for those who liked to live off the land and who were interested in photography and outdoor sports. There was also a large degree of independence for men in the field; ranger districts were large, as large as some national forests in the states, and inspections were few. The result was the growth of a core of men who remained in the Forest Service and who became devoted to Alaska—men like G. M. Archbold, W. A. Chipperfield, and Lee G. Pratt. [21]

Administration after 1921 was based on a system of a forest supervisor for the Tongass in Ketchikan and a forest supervisor for the Chugach in Cordova. When Alaska became District 8 in 1921, Flory's office was moved from Ketchikan to Juneau, which has remained headquarters for the district and region ever since. From a technical standard, the Alaska District was poorly administered. Flory spent a great deal of time serving on the Alaska Commission. He also had a great number of sideline activities, including rock collecting. He was a founder of the Juneau Garden Club, then a largely male organization. He spent much of 1928 compiling a history of the Ballinger-Pinchot dispute from sources in Alaska; the manuscript is now unfortunately lost. Merritt was an extremely capable and tireless field man as assistant district forester, but he left Alaska in 1934. Heintzleman spent much of his time in the states promoting pulp sales and in the 1930s was called there to assist in NRA work. Fortunately, the caliber of the field men was high, and there was probably less need for formal supervision than in most districts in the states.

There were also localized administrative problems. Before 1921, both the Tongass supervisor and Flory were stationed in Ketchikan, and the latter took on some of the former's functions. The supervisor was not given full responsibility, as on other national forests. Later, Tongass Forest Supervisor Robert A. Zeller was not consulted about road plans, the proposed pulp sale to Alaska Pulp and Paper Company, or land classification work; the supervision of timber sales was given to B. F. Heintzleman. There was no orderly planning. Assistant Forester E. E. Carter wrote in 1924 that the state of the Chugach "averaged with that on most national forests about 1907 or 1908, with the work in some lines not even on standards which would have been regarded as suitable then." Carter did not blame it on the staff—Supervisor W. J. McDonald, Deputy Supervisor Pratt, and Rangers John G. Brady and Thomas E. Murray were excellent men—but rather on the district and on Washington, which "failed to ascertain or take proper action on the Chugach in regard to such fundamental matters as fire protection, the administration of timber cutting, and the adjustment of boundaries." Carter felt the need for both fire control and timber management in the area tributary to the Alaska Railroad and questioned the need for the Anchorage Ranger District as an administrative unit. [22]

|

| Forest Service employees W. J. McDonald, E. M. Jacobsen, and L. G. Pratt on the Copper River and Northwestern Railway. (Rakestraw Collection) |

In order to assign duties more clearly and to get a better administration, a new scheme was set up in 1931. Field divisions were established to replace ranger districts. These included the Southern, with headquarters at Ketchikan; the Petersburg, with headquarters at Petersburg; the Admiralty, with headquarters at Juneau; the Kenai, with headquarters at Anchorage; and the Prince William Sound, headquartered at Cordova. Headquarters for the Kenai Division were later established at Seward. [23] In the meantime, though not related to the aforementioned reorganization, there were other changes in terminology. All districts became regions in 1930; district foresters like Flory became regional foresters. Alaska became Region 8; in 1934, through renumbering, it became Region 10.

The Washington Office conducted several inspections during the period. Assistant Forester E. E. Carter made a searching general inspection in 1923; R. H. Headley and C. H. Squire came in 1925. E. W. Loveridge made an inspection in 1930 that was marked by highly strained feelings between him and members of the Alaska force, particularly Melvin Merritt and G. M. Archbold. Assistant Chief G. M. Granger made a detailed inspection in 1936 and had high praise for the general quality of the local administration. [24]

The year 1936 was also marked by a visit of the Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Personnel, headed by Frank Russell, and a highly disruptive report. The Russell report revealed an investigation rather than an inspection; it contained as much gossip and as many unsubstantiated accusations as an FBI file. Harold E. Smith, district ranger in the Prince William Sound Division, was criticized because of discrepancies in vouchers of shipments with the Alaska Transfer Company. Accusations were made that he had used a local lawyer's office to study law on official time. Administration of payrolls was criticized; overtime was the rule, with no compensatory time. Wellman Holbrook, assistant regional forester, had taken some condemned, worn-out blankets home to his wife, who had donated them to charity. Hearsay evidence was used to accuse one man of using government labor to build a private house. Russell condemned the use of Forest Service boats to take families on picnics. The region was held to be lax in the use of annual leave and travel on official time; some personnel had taken a trip to the interior and not charged the time properly. Finally, Regional Forester Flory was criticized for inefficiency, for being a "playboy," and there were hints of "woman trouble." He was soon transferred to Washington State, where he became supervisor on the Mount Baker National Forest.

Heintzleman, the new regional forester, was infuriated by the charges. He wrote:

The striking feature of this examination was its dissimilarity from the Forest Service "official inspection" which is always welcomed because of its constructive criticism and suggestions for betterment which are its primary purpose. This, however, was an "investigation" conducted along the lines employed by judicial agencies to obtain evidence in cases involving definite and serious charges of law violation. I know of no such charges having been placed against any member of the Region 10 organization in justification of such an investigation.

The constant questioning of subordinate Forest officers about supervisors; of officers of one Federal Agency about those of another Federal Agency; of merchants from whom purchases were made, and of all classes of the local public with respect to possible infractions by Forest officers of specific laws and regulations (whose breach involves grave consequences) leads to an inference, both inside and outside of the organization, of serious misconduct on someone's part and that a search for evidence to ensure the conviction of the culprit is being conducted. The point needn't be emphasized that in Alaska, as elsewhere, Forest officers are almost invariably outstanding and highly respected members of their small communities, and such investigations are embarrassing to them and detrimental to their standing with the public and with their subordinate Forest Service employees. I strongly urge that such type of investigation be restricted to serious charges and not be made a routine practice in the Department.

On the specific charges, he pointed out that it was desirable for the field men to see the country outside the national forest. He termed false the charges against Smith, those relating to the vouchers, house building, and lax office hours. He pointed out that the Forest Service had always permitted field officers to take their wives to see the country and that the privilege was not abused. Such travel was also used to check the winding of streamflow recorders, saving a special trip to do this on official time. He acknowledged the charges involving the condemned blankets but felt it trivial at best. As far as the charges against Flory were concerned, it was not necessary to meet them. Flory had just been transferred, but Heintzleman implied nonetheless that the charges were false.

Chief Forester F. A. Silcox supported Heintzleman on several of the points. In regard to leave, he wrote, "I think there is sometimes a tendency on the part of auditors to forget that the humanities of certain situations merit some consideration in applying the rules as to leave or similar matters." On the boats: "If occasional water trips are denied Service residents in Alaska, one of the few sources of pleasure they will have will be taken from them." On Flory, he "questioned the wisdom of such interrogations by inspectors or auditors," while he dismissed the charges against Smith as "gossip." [25]

Inspections notwithstanding, the work of the rangers and supervisors was ordinarily in the field. W. A. Chipperfield reported that his usual routine was three weeks in the field followed by one week in the office writing up reports. Hours were long, with twenty-hour days not uncommon. It often took a long time to go by boat from the ranger station to work. George Peterson noted that he had worked 291 hours and traveled 700 miles by boat in March 1921. The men faced the hazards of storm, shipwreck, and inclement weather. The work itself involved scaling, cruising, surveying town lots, patrolling, and the like. During the 1930s an increasing amount of time was spent on CCC projects. They also did rescue work, as revealed by a typical entry from the diary of Harold Lutz:

July 16, 1925

Found a scow boat from the Nellie Juan cannery wrecked just outside of the skookum chuck. Men intended to go in late p.m. before the high tide, wind rolled boat, broke mast and boom. Men camped on beach lagoon. Gave coffee, bread, matches, etc.

As before, the boats were put to the service of a variety of people—members of the Game Commission, Park Service men, visiting dignitaries, archaeologists, researchers, and the like. [26]

Boatmen accompanied the rangers on their work. They were responsible for seeing to the upkeep of the boats and also aided the rangers. Boatmen were a distinctive breed of men, as individualistic as the old-time packers of the Forest Service in the states. Their logs are a good source of information on day-to-day activity. They vary in content. Bernie Aikens, in the logs of Ranger 1, comments cheerfully on a colleague's sobriety and on the quality of Ranger Kane's profanity. On the other hand, there is occasionally stark tragedy, as in the log of the Weepose dealing with the death of Jack Thayer:

Oct. 16

Elija Harbor. Thayer killed by bear. Thayer and Fred (Herring) left about 8.15. Fred back at 3 p.m. Report bear got Jack about 2.10. Carl Collins of Weepoose and Fred left to get Thayer and found him at dusk. He was pretty bad. Passed on at 10.30 p.m. Tried packing him out and got 1/2 miles and had to leave him and go for help. Too much for two men. To Weepoose.

Oct. 17

Weepoose left Elija Harbor 11.15 a.m. Went to Pybus Harbor for help, got 5 men.

Oct. 18

Left Pybus Bay 4.30 a.m. got to Elija at 7.10 and 5 men left at 7.30 and got back with Thayer's body at 11.30 p.m.

Oct. 19

Arrived Juneau at 8:30 p.m. running all night. [27]

The number of boats in use on the Tongass increased. By 1921 there were five boats of the Ranger class, from thirty-five to forty feet long, powered with 20-25 h.p. engines; these were the workhorses of the Forest Service. The Tahn continued in service. A ninety-eight-foot yacht, the Hiawatha, was purchased in 1921; it had twin 80 h.p. motors. It had been a patrol boat for the Navy. The Hiawatha was a bad investment; the engines were in poor shape, and it was too large and expensive to run regularly. It was used to some extent to take visiting dignitaries around and as a floating camp, but eventually it was traded for the sixty-five-foot Chugach. The Weepose was also purchased in 1921. It was a sixty-five-foot boat with an 80 h.p. motor. Its log indicates that there was continual trouble with its engines and toilets. There was also a tender, twenty-two feet long with a 5 h.p. engine. The marine station on Gravina Island near Ketchikan was a busy place, and its facilities for boat building and repair had to be enlarged. [28]

Skiffs with Evinrude outboard motors were used for station work and for work on the rivers. This, too, had its hazards, as one diary entry indicates:

August 2

Started up river after noon and found river overflowing banks, making progress very slow. Caving banks fill the river with sweepers. At 3 p.m. the boat swamped and entire outfit washed away. Succeeded in rescuing Mr. Ball after narrow escape. Beached the boat and recovered tent, bedding and a few other articles. Lost rifle, all clothing, ax, tools for engine, oars and all provisions, notebooks, papers, etc. Cached recovered property in trees near lake and walked to lake, where we found an old skiff, in which we crossed to south shore, where there is an old trail. Walked to Ray's cabin and camped without food. Mr. Nettleton and Mr. Ball will return for the boat when river falls again. [29]

Air travel came to be of increasing importance during this period. The Navy played a major role in the development of the region before 1928 by making aerial photographs, which were of tremendous importance in developing the timber resources of the country. As accurate as ground surveys, the photographs located bodies of timber, waterpower sites, streams, lakes, and logging shows, and were a major asset in planning. Airplanes were also used increasingly for inspection trips by supervisory personnel. A several-day inspection trip over enormous areas—the Juneau Ranger District alone covered 9 million acres—could be done in a day by plane. Planes also supplied CCC camps, especially those on the inland lakes of Admiralty, and isolated trail crews. They began to be used in the Kenai for spotting fires. [30]

Motorized transportation also became more important in the forests. After the building of roads, trucks were used to haul equipment within the forests. Trucks became a key part of the protective picture in the Chugach, where roads to Moose Pass and Hope made it possible to move men more quickly than by railroad.

The public relations of the Forest Service also improved during this time. The road-building program was particularly popular in the coastal cities, where the highways gave breathing space to the people, and in the Kenai with the development of that region's enormous recreational possibilities. [31] The CCC programs were well liked, particularly the totem pole program. The Forest Service took an active part in National Fire Prevention Week in the Anchorage area. Both the overhead and the rangers were well liked as individuals and as members of the community.

Forest Research

(written by Raymond F. Taylor)

When Frank Heintzleman was put in charge of forest management in the new District 8, he was well aware that the Tongass lacked many technical tools. The volume tables used for cruising were those used for spruce and hemlock in Oregon and Washington. There were no growth tables to show what second growth stands would do after the decrepit and ancient climax forest was cut. How best to get reproduction of desired species or to treat cutover areas was more or less unknown.

Efforts had been made to get funds for forest research, but not until 1928, when a pulp operation on the Tongass looked very promising, did Congress authorize a forest experiment station for Alaska. Then, when the Depression caused the pulp company to lose interest, no funds were appropriated for the station. That's the way it stood for twenty years. Heintzleman, in the meantime, using timber management money, had started studies of forest reproduction on small cutover areas and of growth of young stands of various age. Measurements were taken of trees being cut for saw timber and piling in order to make local volume tables.

James M. Walley and Harold J. Lutz, young technical assistants, were assigned to this work in 1924. No transportation was furnished, so they had to descend on the local ranger and crowd into his boat for short periods in order to work on promising areas in his district. Sleeping under a tarp draped over the boom in wet weather or lying alongside a leaky gas engine did not put the researcher in the best of moods to go forth with enthusiasm. But they did, and they ate wet sandwiches, standing up, at noon.

In 1925 Lutz transferred to the Chugach, and Raymond F. Taylor took his place on the Tongass. There was some "boarding out" with rangers, to their disgust, but later a boat was assigned for research and a boatman hired for the summer. Some of these men knew how to start an engine and steer but not how to lay a course. A few liked to take wild chances, hoping the bottom would miss the rocks the chart showed so plainly. The boatman was also supposed to cook, and he made valiant efforts.

|

| Harold Lutz photographed the Paxson Roadhouse along the Richardson Highway in the Interior. (Harold Lutz Collection) |

The researchers would tie up at a logging show, measure logs by sixteen-foot lengths, take diameters with sixty-inch calipers, measure lengths with an 8.3-foot bamboo stick, and the top length with a steel tape. Age was counted at the stump. Sometimes, to get good distribution of sizes, they would wait for certain trees to be felled, and occasionally, due to poor judgment as to which direction the tree was to fall, there was a good deal of leaping from log to log. In those days of the long two-man saw and springboards, fallers were often ten feet in the air and had their own problem getting the saw out and themselves out of the way when the tree began to go. Researchers in the area were expendable.

Studies of second-growth had to be made wherever there were such stands. Since logging by cable was relatively new, many areas studied were where wind-storms had leveled the old trees. There were also abandoned Indian villages or mining towns, as at Hollis and Sulzer, growing up to trees. A few acres had been burned. The idea was to get a range of sites from poor to good and a range of ages of stands. Plots were laid out, usually from a quarter-acre to one acre in size, and some trees were bored for age of stand. All trees were measured for diameter, and sample heights were taken. From this basal area, volumes in cubic and board feet were computed.

[32]Walley transferred to the Lake States in 1928, and Taylor moved to Juneau to take charge of research. He was assigned a boat, usually one that was ready to be condemned, and a summer assistant was hired. Taylor and Lutz had both gone back to Yale in the fall of 1926 for master's degrees. Lutz remained to teach, but Taylor returned with a little more know-how in research.

During the years from 1924 to 1934, research continued in this manner—fieldwork from about April to October and working up results in the long dark days of winter. Permanent plots were established in second-growth stands to be remeasured at five-year intervals, and the total of all plots brought up to the number required to construct a set of yield tables. This same sort of work was going on at newly established forest experiment stations in the states. Richard E. McArdle was working in Douglas-fir and Walter H. Meyer in spruce-hemlock stands under Thornton T. Munger, director of the Pacific Northwest Forest Experiment Station. Leo A. Isaac of the same station was deep in studies of reproduction. Experimental forests were being established at all stations. In Alaska, however, one man with one assistant worked like crazy to get basic information for management under a pulp cutting regime. While still a bachelor, Taylor found time during evenings to write and illustrate a Pocket Guide to Alaska Trees.

In 1929 Taylor returned to Yale under a Charles Lathrop Pack Fellowship to work on a doctorate. He finally received it in 1934, the delay being mostly caused by his insistence on working on a dissertation titled "Available Nitrogen As a Factor Influencing the Occurrence of Sitka Spruce and Western Hemlock Seedlings in the Forests of Southeastern Alaska." [33] Fieldwork for this study was in addition to the regular studies of reproduction. Also in 1934, Taylor's work on growth and yields of future stands was published as a technical bulletin. [34]

The dissertation was published in Ecology in 1935 and pretty well summarized what had been revealed in the reproduction studies; namely, that clearcutting and tearing up the raw acid humus resulted in a good stand of new young trees with adequate stocking in about ten years. There were other reports on the details. The growth and yield bulletin summarized the work often years and showed that the climax forest, in which decay and mortality offset any growth, would be replaced, when cut for pulp, by a new stand of fast-growing trees, which in about a century would have twice the volume of the climax stand. The tables, charts, and manuscript for these were all worked up in the Juneau office. On the side, new volume tables were issued for the main species. The figures for the yield tables were borrowed by the Pacific Northwest Station to add to Walter Meyer's yield tables for the Pacific Northwest.

It was lucky that all this work was completed by 1934, as emergency conservation work had taken over in Alaska and there was no money for research. Taylor, not wanting to boss CCC crews, transferred to the Washington Office as assistant chief of the Division of Silvics. He escaped to the newly formed Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station a year later, and, after fourteen years at three stateside stations, returned to Alaska in 1948.

This research work, though old, is still of great value. Old reports and publications should be studied. There has always been a tendency for new researchers to discard as valueless anything that is over ten years old. Because of that, they "discover" that seeding cutover areas by helicopter is, after all, not necessary. That was known in 1930, but using helicopters and treated seed is wonderful public relations.

CCC Projects

General Projects

The Civilian Conservation Corps was one of the major accomplishments of the New Deal. During the closing days of the Hoover administration, funds were made available for putting men to work in conservation projects, largely road and trail and construction projects. Incoming President Roosevelt called for full-scale use of manpower in work relief to conserve, protect, and renew natural resources. The Emergency Conservation Act was passed on March 31, 1933. Roosevelt used the term "Civilian Conservation Corps" as an equivalent for the emergency conservation work, and the name gained currency. The act was extended by Congress and in 1937 was supplemented by formal establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps, set up for a period of three years.

The CCC program was administered by resource agencies in the Departments of the Interior and Agriculture. The Department of Labor did the recruiting, the War Department operated the camps and ran the educational program, and the resource agencies carried on the field activities. Enrollment was open to young men from eighteen to twenty-three years of age. Foremen were largely local men, often loggers or Forest Service retirees.

The venture was a new and a challenging one for the Forest Service. As Chief Robert Y. Stuart pointed out, the Forest Service had always been able to be selective in choosing its personnel. With the establishment of the Forest Service, the old Land Office policy of allowing political appointees had been dropped for the merit system and for standards for retention and promotion. The new men in the CCC program were chosen by another agency, on criteria other than merit; they were untrained and unmotivated. The Forest Service had the test of giving both technical and vocational training and working with somewhat refractory human material.

The program proved highly successful, and it is generally regarded as one of the most successful of the New Deal efforts. It achieved its basic goal of relieving unemployment; it gave 3 million young men a new start and a new outlook; it awakened the public to a new concern for conservation; and it aided in its main objective of conserving and renewing natural resources. There were many factors that accounted for its success. The Army career officers, in the doldrums and out of public favor because of the isolationist temper of the times, found the work challenging and brought great professional ability to bear on the project. The Forest Service worked with imagination and judgment. It developed new techniques, such as the progressive method of fire fighting in which it was able to make maximum use of untrained men. [35]

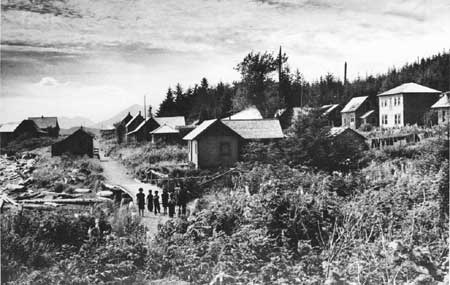

In Alaska the CCC program was unique in many ways. There was unemployment in Alaska, and the Forest Service was given authority by the government to handle disbursement of relief funds voted by Congress in the national forest area. The first of these were Federal Emergency Relief Act funds to care for unemployed people. In the beginning, these allotments had few strings attached and were used to relieve unemployment by local projects. In Craig, a water system for the village was put in; in other areas, roads and trails were built. [36]

When the CCC program started in 1933, there were no federal troops in Alaska except for an infantry contingent of 200 men at Chilkoot Barracks near Haines and a nearly equal number of Signal Corps men stationed at the many telegraph and wireless stations throughout the territory. It was therefore impossible for the Army to carry out its function as it did in the states. Consequently, Regional Forester Flory secured the president's permission for the Forest Service to take charge of all CCC activity in Alaska. This included enrolling, clothing, housing, transportation, as well as supervision of projects—everything, in fact, except disbursement of funds. The Army paymaster at Chilkoot issued the checks; the Department of Labor selected the enrollees. Unemployment in Alaska was not primarily of the young, but of the middle-aged. It was also seasonal, involving men who did not have a winter "stake." Age restrictions on enrollees were dropped, therefore, as were restrictions on re-enrolling. This latter provision made it difficult to keep leaders and cooks, but it met Alaskan conditions. A one-year residence requirement was established to eliminate young men who had come to Alaska for seasonal work and became stranded. [37]

The problem of clothing, which had to be adapted to a variety of climates, mostly bad—including rainy, snowy, and cold—was worked out through the Army Quartermaster's Office in Seattle. A list of clothing necessary for Alaskan conditions was prepared. The Seattle purchasing agent for the Alaska Railroad, who already handled Alaskan purchases for the Forest Service, prepared specifications and called for bids. The plan worked well. [38]

Charles Burdick was put in charge of the CCC work for all Alaska. He held the post until about 1938, when he was transferred to the reindeer project. After that, Heintzleman managed the project. Because of the distances and slow travel, small camps were set up instead of the large camps characteristic of the states. By the end of 1934, the Forest Service had 325 men enrolled: 125 in the Southern Division out of Ketchikan; 25 at Petersburg; 130 in the Admiralty Division working out of Juneau; 25 in the Prince William Sound area; and 20 in the Kenai.

Their work in the early years was varied. In the Kenai it consisted of building trails and truck roads for recreational and protective purposes, stream-gauging stations, bridges, a warehouse, and small boat facilities; burning on the right-of-way of the Alaska Railroad; and most important of all, fire suppression. Around Ketchikan and Petersburg, truck roads and trails were built, and log jams from the Unuk River were removed. The greatest work was in recreational planning, including the building of campgrounds and water systems.

In the Admiralty Division some roads were built, but the prime work of the men was planning and building recreational areas. These included a shooting range and skaters' shelter cabin near Mendenhall Glacier and shelter cabins and trails on Admiralty Island in the lake area. Near Sitka, by 1934, twenty-two miles of trail and several log cabins were built and the beginnings made, under both Forest Service and Park Service personnel, of archaeological exploration on the site of the Russian settlement at Old Sitka. [39]

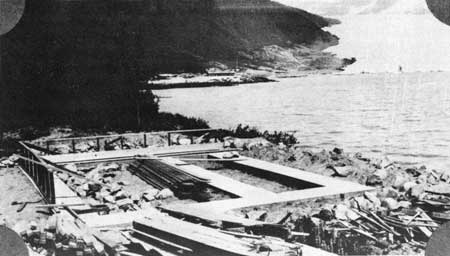

|

| The Civilian Conservation Corps put young men to work on the national forests during the Depression. Recreational facilities built at Mendenhall Glacier near Juneau included a skaters' shelter cabin (foundation being laid in this 1936 photo) and a rifle range in the center background. (U.S. Forest Service) |

|

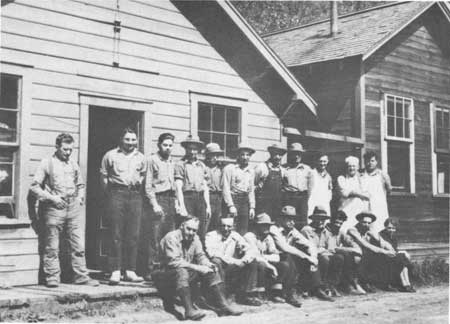

| The CCC crew, posing in front of rented quarters, worked on the Basin truck trail near Juneau. (U.S. Forest Service) |

|

| CCC crew at Quartz Creek Camp in the Kenai Division. Middle-aged men served along with younger fellows. (U.S. Forest Service) |

By 1937 there were 1,037 men enrolled in the national forest area: 262 in the Southern Division working out of Ketchikan; 101 at Petersburg; 245 in the Admiralty Division working out of Juneau; 77 in the Prince William Sound area; and 240 in the Kenai. In addition to continuation of the work projects noted earlier, there were many special projects. These included a trout hatchery at Ketchikan to provide trout to plant in near by lakes; at Sitka, landscaping the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey station, restoring the old Russian cemetery, and building trout traps and floats in cooperation with the Bureau of Fisheries; building a dock and a small boat harbor in Cordova; building a bear observatory on Admiralty and skiffs for use on the inland lakes; and wing dams for channel control and a suspension bridge on Eagle River near Juneau. At Little Port Walter, houses were built for the Bureau of Fisheries, along with shelter cabins, floats, a salmon weir, and a fifteen-room biological laboratory.

In the Kotzebue area Heintzleman worked out plans with the Office of Indian Affairs for the wolf-reindeer project. He conferred in September 1927 with officials of the U.S. Biological Survey and the Indian Office. The program emphasized trapping, shooting wolves, and teaching the Natives to close-herd reindeer. Logan Varnell was put in charge as foreman. One hundred-eighteen Natives were hired in the Kotzebue area; their salaries were paid from November to July by the Biological Survey and the rest of the year by the Forest Service.

The wolf-reindeer project was not particularly successful. Varnell felt that the Eskimo community ownership of the reindeer lessened their feeling of individual responsibility. Many herds were unattended. The wolves were not under control, reindeer would elope with caribou, and there was need of a few large herds, rather than many small ones, for control to be effective. Varnell recommended putting the herds under individual ownership, building line cabins or igloos for the herders, and giving the Eskimos formal training in range management. The project was abandoned in September of 1938.

Other work in the Kotzebue area was more successful and lasting. This included building drainage ditches, community wells, landing fields, herders' shelter cabins, and cold-storage facilities. [40]

Nowhere was the work of the CCC more appreciated than in the isolated Native villages and missions in the interior. Seventy-six enrollees worked on the lower Yukon. The CCC built a muskox corral on Nunivak Island. They razed the Army barracks at St. Michael. Lumber from the barracks was used to build a workshop for Father P. G. O'Connor's mission at Kaulurah. At Galena there was extensive flood damage; the debris was cleared away, the land cleared, and prepared for a garden. Community houses and sanitation drainage projects were common. A telephone line was built between Nulato and Unalakleet. These projects broke down isolation and supplied some amenities. Letters written to the regional forester from the teachers and missionaries are among the most touching documents in the entire history of this enterprise. [41]

A forty-man camp was set up in Fairbanks, and W. A. Chipperfield was placed in charge of it. A variety of work was carried on, including salvaging twenty miles of fence that had been used to enclose muskox pasture before the herd was moved to Nunivak. Landing fields were built, and fire and flood control was introduced on the Ghena. [42]

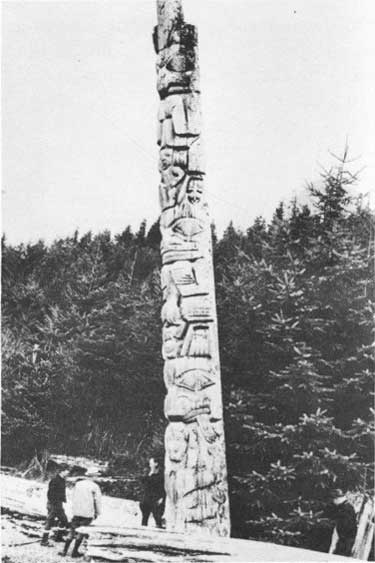

Totem Pole Project

The CCC work took on other aspects by 1938. The Forest Service had always been interested in Indian antiquities. W. A. Langille had been partly responsible for the creation of the Sitka National Monument, and he and F. E. Olmsted had initiated the movement toward setting aside Old Kasaan. Boat logs contain some accounts of early efforts to preserve Indian antiquities under the provisions of the 1906 act. [43]

Between the creation of Old Kasaan National Monument and 1938, a great deal of planning for totem pole preservation took place. Flory visited the national monument in 1921 and suggested the necessity of getting an overall plan of preservation to prevent artifacts from being looted and to protect totem poles from the weather. He felt that the most practical thing would be to move the outstanding poles in Old Kasaan and elsewhere in the Tongass National Forest to Sitka National Monument and there to set up a primitive Native village. The Smithsonian Institution favored the program, as did the Bureau of American Ethnology. Territorial Delegate Dan Sutherland introduced a bill to finance the operation, but it died in committee. Other attempts failed for lack of funds. After the Reorganization Act of 1933 transferred jurisdiction over all national monuments to the National Park Service, that agency's officials sought appropriations to move the best totems in Old Kasaan to Sitka. This effort also failed for lack of funds.

In 1934 the Forest Service and the Park Service developed new plans to move the Old Kasaan poles to Sitka. Flory pointed out that although the Sutherland Bill for a special appropriation to move the poles had not been approved, he nevertheless hoped to get the project funded through the general appropriation bill. It would be a waste of time, he thought, to try to rehabilitate Old Kasaan. The poles should instead be shipped to Juneau or Sitka and Native labor used to rehabilitate them. Meanwhile, Wellman Holbrook examined the Sitka poles and found them in bad condition. Some sections had rotted away, and there was a great deal of decay in the wood, particularly at the bases of the poles. He recommended that expert help be brought in to rehabilitate the poles, with the CCC furnishing manual labor, and that action be started in Washington.

In Washington, Associate Regional Forester Melvin Merritt called on Harold G. Bryant, head of the Park Service's Branch of Recreation and Education. Merritt urged the abandonment of Old Kasaan, the assembling of the good totems at Sitka, and the transfer of qualified men to the area for the repair work. The Forest Service pledged its cooperation. Merritt supported Flory's recommendation that a community house be constructed out of the remains of existing ones. Forest Service photographs and descriptions of Old Kasaan were transferred to the Park Service. In June W. J. McDonald examined Old Kasaan and estimated that there were about twenty serviceable totems. He recommended repairs on the poles to consist of cutting them off at ground level, replacing rot with sound wood, and replacing the poles on concrete bases. He estimated costs would be from $5,000 to $7,000.

By the fall of 1934, the Park Service had made plans to move four of the best totems to Sitka. These were large poles, about fifty feet high, three and one-half feet at the base, and one and one-half feet at the top. Native owners were sought out. They asked $125 for each pole, saying that they had originally cost $2,000 at the potlatch in which they were erected. The Forest Service estimated that the cost of shipping the poles to Sitka would be about $2,500. The Park Service abandoned the project for lack of funds.

The Forest Service became involved during this time, both directly and indirectly, in archaeological work. In 1932 Frederica DeLaguna made the first of her many expeditions to Alaska. She sought an archaeological permit to do work in the Tongass and the Chugach national forests, and the Forest Service aided her in transportation to the archaeological sites. Flory, in commenting on her work, complained that too much of the material recovered from such excavations went out of the territory; he suggested that half the Indian artifacts recovered be donated to the University of Alaska. No agreement was reached, and after the exploration was over, Flory again commented unfavorably on this failure.

The second enterprise involved using CCC money to excavate Old Sitka, site of a fort established by Baranov in 1799. A stockade, bath house, and various buildings had been built at the site, on a bay to the north of Sitka, but the settlement had been wiped out by Tlingit Indians in 1802. The site had been occupied by a cannery in 1878 and a smokehouse in 1910. In 1907 it became part of the Tongass National Forest. In 1914 Father Sergius George Kostrometinoff of the Sitka Cathedral was issued a special-use permit by the Forest Service to erect a cross at the burial site of the Russians.

Charles Flory had a deep interest in Alaskan history. In the fall of 1934, he used CCC funds to start archaeological excavations on the site of Old Sitka. W. A. Chipperfield supervised the project; it was directed by John Maurstad, CCC foreman. A fifteen-man camp was set up in the vicinity. Bancroft's History of Alaska and a translation of an account of the massacre by George Kostrometinoff were used as background. The area was mapped, with notations as to the sites of the buildings from postholes, relics, and Native traditions. In the year's work about 1,000 artifacts, some Russian and some Indian, were located. The most important find was a copper plate bearing a cross and an inscription claiming the land for Russia, probably buried there by Baranov in 1795.

The artifacts were first stored in the basement of the capitol building for safekeeping. On Flory's suggestion, they were transferred to the University of Alaska in 1937. They remained there until 1963, when they were shipped to the Western Regional Office of the National Park Service for study by the regional archaeologists. They were then transferred to the museum at Sitka National Monument, where they are now located.

Recent critics have stated that this operation was not carried out by trained archaeologists, and indeed the work lacked some of their refinements. The records show, however, that Chipperfield and Maurstad exercised all the care and skill one could reasonably expect of the intelligent layman. In any event, the excavation was carried out in the nick of time. During the war a Navy installation was planned for the area, and extensive bulldozing was carried on.

There was a lull in the planning between 1934 and 1937. The first two years of CCC work revolved around badly needed recreational work in the southeast and the archaeological work on Old Sitka. In 1937, however, there was a revival of interest in totems. It came partly from requests by the Alaska Native Brotherhood, through William Paul, Sr., that more Indians be employed on relief projects. Also, Charles Flory was transferred to the Mount Baker National Forest and was replaced by B. Frank Heintzleman, a skilled public relations man who dedicated his entire life to Alaskan interests and gave the movement more momentum than it had had previously. Heintzleman found support in the higher echelons through Chief Ferdinand A. Silcox of the Forest Service; Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes; Ernest Gruening, director of the Office of Territories in the Department of the Interior; and Arno Cammerer, director of the National Park Service. Through their efforts, most of Flory's dreams were realized. Early in 1937 a series of letters was exchanged and conversations held among Silcox, Gruening, and Heintzleman. Silcox informed Gruening that the poles, including those on the national monuments, were private property and that the Indians asked large sums ($1,000 each) for them. Ownership was also often in dispute, so the validity of a given purchase was unpredictable. Silcox suggested use of CCC work on villages on deserted shorelines along the lines of travel, building totem villages, and buying totem poles at public subscription.

During 1937 and 1938 field examinations were made of villages. Forest Service men photographed poles and community houses, evaluated their condition, talked with Indians over matters of title, and outlined plans to get title to the poles and move them to central locations. To support this work, Heintzleman borrowed a large number of books and photographs on the Indians of southeast Alaska from the Smithsonian Institution, American Museum of Natural History, National Museum at Ottawa, and American Geographical Society. Meanwhile, he kept the mails and wires to Washington busy, seeking money for the project. He initially sought $51,760 in WPA money for rehabilitating poles and constructing community houses. But these applications failed, and most of the money spent was from CCC funds, except for the Sitka project.

Eventually, the Sitka project got started when the Forest Service made an agreement with the National Park Service to restore the Old Kasaan poles. This involved their removal from the site and restoration with WPA money. The Park Service recommended that a trained ethnologist be in charge of the work. Meanwhile, Heintzleman conferred with the head of the Office of Indian Affairs, Claude Hirst, who recommended that meetings be held with the Indians and that blanket authority be given by all claimants of the poles, making them the property of the entire community. The poles could then be set up on a public site dedicated to that use. The Forest Service, for its part, agreed to meet costs of inspection, transportation, reconditioning, and erection from CCC and Forest Service funds. With all the concerned agencies in agreement, the Forest Service experiment in totem pole preservation and restoration was ready to begin. [44]

Sitka National

Monument

In January 1939 the Forest Service secured a WPA allotment for totem pole restoration. Heintzleman wrote to Arthur Demaray of the National Park Service, offering to use the funds to restore the poles at Sitka National Monument. He asked if the Park Service could furnish a technically trained foreman. The Park Service had no specialist available and suggested that Heintzleman hire one from the University of Washington or the University of Alaska; it told him to go ahead with the project if he found none available. Support came from other institutions. The Alaska Road Commission gave the Forest Service use of its dump truck, and the Forest Products Laboratory sent advice on the use of Permatox D, a flat, colorless preservative similar to spar varnish. It directed that the poles be soaked in the solution when dry; if soaking were impracticable, the poles should be brushed with the solution. The purpose was to prevent moisture from entering the pole and causing rot. Charles Burdick, associate regional forester, made a survey of the poles in March, sending pictures and reports on the condition of each pole. With the expiration of WPA funds in the same month, CCC funds were used to complete work.

The project was carried on with nine Indians as workers, John Maurstad as foreman, and George Benson as chief carver. Some of the poles were badly deteriorated; they had for years been held together by wire and were hollow shells under the ground. A complete photographic record was kept of all poles, both originals and duplicates. A community house designed by Forest Service architect Linn Forrest was built, and most of the work at Sitka was completed by March 1940.

Sitka National Monument received a full-time superintendent for the first time in 1940 when Ben Miller arrived from Glacier National Park. Miller was highly enthusiastic about the totem restoration and the caliber of the work being done, writing, "After we have Sitka National Monument in the shape it should be in, there should be erected a monument to the Forest Service and Regional Forester Heintzleman." There was some debate as to the fate of the old poles. Frank Been, regional park superintendent, wrote, "Personally, I don't think they are worth building a shed for, especially after we have exact duplicates." Even if they had a shed, he noted, it would be hard to guard them against theft, and poles so rotten could be destroyed. Pending design of a shed, however, it was decided to store the old totems in the open on skids.

Been and Forrest thought that a new historical totem giving the history of Sitka would be appropriate. A pole was commissioned to show Baranov and his dealings with Chief Keeks-Sady. This was planned to be placed at the Sitka dock site, an area set aside for national forest use by executive order in 1920 and amended by executive order in 1933 to establish a public park. The Baranov pole was duly commissioned, but it ran into all sorts of difficulties. George Benson, the head carver at Sitka, took another job. The cedar log was taken to Wrangell and fashioned by another carver using the Benson design. But Sitka Natives protested when it was erected; it did not, they said, repeat the true story of the peace between Baranov and Keeks-Sady. Baranov was placed on top of the pole, dishonoring the Indian chief. Also, the double eagle given Keeks-Sady, now in the Alaska Museum, was to have been on the pole. There were threats by the Indians to burn or mutilate the pole, but eventually the dissension died down.

The Sitka venture would rank among the highest accomplishments of the project. The poles were very old; they had been old when Governor John Brady collected them for showing at expositions in St. Louis and Portland. Later returned to Sitka, they were badly deteriorated. About half the poles were restored and the rest duplicated. The quality of the carving was, in general, good. The community house was new, following the design of the old dwellings, and was well constructed. [45]

|

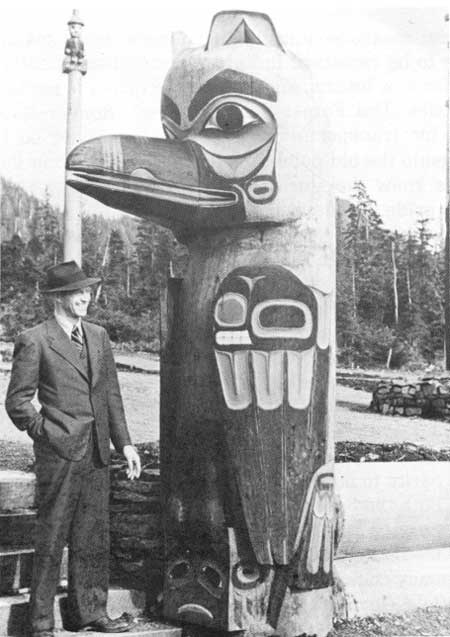

| Linn Forrest with an entrance pole at Saxman Park, which he designed and laid out during the 1930s. (Linn Forrest Collection) |

Linn Forrest and CCC Totem Pole

Work

Linn Forrest was put in command of the totem pole project, and he remained in charge as long as the project lasted. Forrest was educated at the University of Oregon and Massachusetts Institute of Technology, majoring in architecture. As an architect for the Pacific Northwest Region of the Forest Service, he had been in charge of the construction of Timberline Lodge on Mount Hood. This alpine lodge, designed to give work to artisans, was built with WPA funds and was a show place of alpine architecture. The lodge featured a great deal of hand carving and hand-wrought iron work, and building it was good training for the totem pole project. Forrest came to Alaska in 1935 to build alpine lodges at Sitka and in the Kenai. Instead, he was given charge of the totem pole project.

The work was set up as a year-round project. At each of the sites selected for totem parks, large open sheds were built to serve as workshops and later as sheds in which to store the old totems. These were built near school playgrounds so that they could better be used as shelters for children and as recreation centers. The workers were chosen from local villages, eliminating problems of transportation. Carvers were chosen from among the older men who had retained such skills; the carvers in turn trained younger men.

Tools for carving were handmade, modeled after older tools used before the coming of the white man. The Indians demonstrated much skill in making these, using car springs and old files, and showed an astonishing knowledge of metallurgy. Samples of the Native paints were made, using ancestral techniques. Black was made from veins of graphite, white from clam shells, yellow from lichen and yellow stones, and green from copper pebbles. The Indians knew where to locate the veins of rock from which the colors came. These were ground up in mortars with pestles. Then salmon eggs were wrapped in cedar bark and chewed; the saliva was spit out and ground up with the coloring. The paint made was authentic and permanent, but, for a project of this proportion, larger quantities were needed. So Forrest duplicated the colors with commercial pigments. Following is the estimate of material necessary to preserve and paint forty totems:

| Dutch Boy white lead soft paste | 750 lbs. |

| Boiled linseed oil | 20 gal. |

| Turpentine | 15 gal. |

| Pale Japanese drier | 45 gal. |

| Chrome yellow light color in oil | 1 gal. |

| Italian burnt sienna in oil | 5 gal. |

| Chrome green medium color in oil | 2 gal. |

| Prussian blue color in oil | 2 gal. |

| Bulletin stay red color in oil | 2 gal. |

| Refined lamp black color in oil | 12 gal. |

This would make 10 gallons of white, 10 yellow, 10 bluegreen, 20 frog green, 20 red, 20 bear brown, 20 beaver red, and 20 of black paint. In addition to this, 40 gallons pentrared, 120 gallons permatox, and 20 gallons avenarious carbolienum were needed for the preservative work. Permatox B was a preservative developed by the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin.

The poles were carried into sheds to be worked on. They were transported whole—none were ever dismembered, except the Seattle pole, of which more later—and placed within the sheds on skids. If the pole was to be restored, it was worked on there. If the old pole were badly deteriorated, a new pole would be carved. Careful measurements, with calipers, were taken of parts to be replaced. Indians felled cedars of suitable size for new totems, and these were rafted to the totem worksite. The Forest Service vessel, Ranger 7, was used for transportation. The new log would be laid alongside the old pole to be copied. The old men themselves knew the stories of the totems, and they took great pride in their work, making every effort to strive for authenticity. They, inspired the younger men, too, with much of their own pride in craftsmanship, and the communities became devoted to the project. As one carver, Charles Brown, said:

The story of our fathers' totems is nearly dead, but now once again is being brought to life. Once more old familiar totems will proudly face the world with new war paints. The makers of these old totems will not have died in vain. May these old poles help bring about prosperity to our people.