|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 6

The Heintzleman Administration, 1937-1953

National Conservation Background

In 1937 B. Frank Heintzleman succeeded Charles H. Flory as regional forester in Alaska. He served until 1953, when he became governor of Alaska. His tenure as regional forester coincided with the second and third terms of Roosevelt's presidency, and that of FDR's successor, Harry S. Truman. It would be well to examine the trends of national politics and the development of forest administrative policy during this period.

|

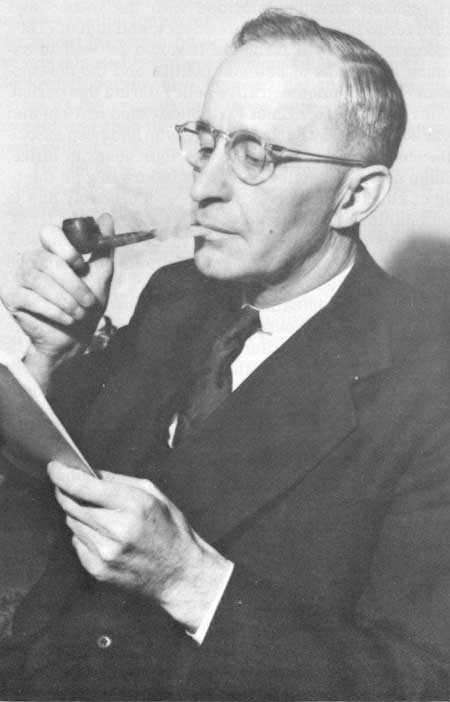

| Earle H. Clapp was acting chief of the Forest Service from 1939 to 1943. He fought for public regulation of the forest industries and struggled to keep his agency from being transferred to the Department of the Interior. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Forest Service Chief F. A. Silcox died in 1939 and was succeeded by Earle H. Clapp, who had been associate chief since 1935. During his four years in office, Clapp served as acting chief. His failure to gain the title of chief of the Forest Service was probably due to his militant resistance to the efforts of Harold Ickes, secretary of the interior, to have the Forest Service transferred to his department. Clapp fought the move vigorously, aided by Pinchot and by friendly members of Congress. In defeating Ickes, the Forest Service had to spend time and energy it would have liked to devote to more important matters. Clapp had headed the Office of Research when that branch was founded in 1915, and he had been a capable administrator. He and Silcox had been dedicated to public regulation of the forest industry. He carried on an uncompromising program for regulation, even asking the president to force compliance with Forest Service regulations under the presidential war power authority, but these efforts failed.

|

| Lyle F. Watts, chief from 1943 to 1952, was the last in a series of chiefs to advocate federal regulation of cutting practices. (U.S. Forest Service) |

In January 1943 Clapp was succeeded by Lyle Watts. Watts was a graduate of Iowa State University who had worked both as a director of a research station and as a regional forester. He served as chief until June 1952. During this period much of the Forest Service's work was devoted toward the war effort. Procurement of timber, cooperation with other agencies, work with the Aircraft Warning Service program, and close cooperation with the War Production Board on a variety of projects occupied Watts during the war years. With the end of the war, he took a major part in helping to organize the Forestry Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, participating in a number of international conferences on conservation.

Watts had other achievements to his credit. The Timber Resource Review, a comprehensive appraisal of the forest conditions in the United States, was started by Watts early in 1952. The six-year study was completed by Assistant Chief Ed Cliff in 1958; it examined in depth the current status and projected future of the nation's wood supplies. Also during his term of administration, the Sustained-Yield Forest-Management Act of 1944 was passed, calling for federal-private sustained-yield units under which federal stumpage could be sold to responsible bidders without competitive bidding and thus support communities and industries dependent on federal forests. The Cooperative Forest Management Act of 1950 expanded the Norris-Doxey Act. The Forest Pest Control Act of 1947 established the principle that the government had responsibility to protect all forestlands from destructive insects and diseases.

Like Silcox and Clapp, Watts was an advocate of public regulation of cutting. His program called for federal acquisition of timberlands, federal cooperation with state and private owners, and federal regulation. By this time, however, the states had passed laws regulating forest practices, including cutting, and the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of a Washington State law. After Watts's administration, the campaign for federal regulation of cutting was dropped, and state regulation took its place.

Ickes resigned from his post in 1946, and his successors, Julius Krug (1946-1951) and Oscar Chapman (1951-1953) were less troublesome to the Forest Service than Ickes had been. Truman, Roosevelt's successor, was a man of the soil and made a creditable record in conservation. His secretaries of agriculture, Clinton P. Anderson and Charles Brannan, were capable administrators. Nevertheless, political attacks threatened the Forest Service once again. This time the agitation came from western members of Congress—Pat McCarran of Nevada, Frank Barrett of Wyoming, Wesley D'Ewart of Montana, and others—who planned to destroy the Grazing Service of the Department of the Interior, to remove grazing lands within the national forests from the jurisdiction of the Forest Service, and eventually to turn national forest land over to the states. The movement was exposed by a group of writers—Bernard De Voto, Arthur Carhart, and Wallace Stegner were the most prominent—who published the plan and mobilized public opinion against it. When some of these members of Congress lost in the Democratic victory of 1948, the threat was removed for a time.

These were crucial and exciting years for the Forest Service. Under two capable chiefs, it carried out great tasks, both foreign and domestic. Abroad, the Forest Service began to play a role of world leadership in forestry and conservation. Men like Tom Gill, Hugh M. Curran, and Walter Lowdermilk contributed to this giant task. In the United States the Forest Service experienced a period of transition from a policy of extensive management to one of intensive management. [1]

In Alaska there was a transition from the old order to the new. Alaska became directly involved in the production of lumber for the war effort and even more directly involved in the revival of Japan as an industrial nation. New problems arose in regard to Indian rights, recreation, and wilderness. The rising aspirations of Alaska for statehood created a series of new interagency problems and relationships.

The new regional forester, B. Frank Heintzleman, was an interesting and complex individual. A builder and dreamer, his major interest was to recruit capital and big industry for Alaska, for without capital the region could not develop. Much of his time was spent in the states attempting to interest outside capital to invest in lumbering and power development. A political conservative, he was liked and trusted by the business community. From a purely technical standpoint, he was not an outstanding administrator. He was hard on the men, expecting a full day's work and more for each workday. He was slow to give raises in pay and reluctant to give transfers. Soft-spoken and modest in manners, he liked to deal with men in individual meetings rather than in group conferences. As the Russell report indicates, however, he fought like a lion for his fellow workers in the face of unjustified criticism. He was a visionary, anxious to move ahead and impatient of details in planning. In his 1939 inspection report, Silcox wrote of him: "My impression is that love of Alaska and determination to help solve its problems are perhaps his strongest motivating forces. It is also my distinct impression that he does a good administrative job." [2]

Heintzleman was not a politician and was at times indiscreet in written communications. One example may be cited. In May 1939 he wrote a letter to Secretary Harold Ickes, writing directly rather than clearing the letter through the chief forester. In it he suggested the need to coordinate action by the various federal agencies in Alaska; he recommended a coordinator, or "Resident Federal Secretary for Alaska," to be appointed by the president. His duties would be to act as a clearinghouse through which the federal bureaus in Alaska could deal with Alaskan matters and report directly to the executive office. He also recommended a Committee of Alaska, made up of cabinet members with the secretary of the interior as chairman. Ickes was at this time deeply committed to transferring the Forest Service to the Interior Department, and the Washington Office of the Service did not receive the suggestion with good grace. Christopher Granger wrote to Silcox:

It seems to me Frank let loose all holds in his letter to Secretary Ickes on coordination. Frank's love for Alaska and his intense interest in its welfare leads him to get out of focus on Alaska's importance and its problems.

Ickes and Granger felt that a planning council, with periodic meetings of bureau heads, would accomplish the same thing. [3]

Heintzleman was highly involved in the cultural and community life of Alaska. He was active in the work of the Presbyterian Church and of the Masonic Order. His interest in the totem pole project has already been pointed out. He was a patron of the Juneau Public Library, buying many books for it and instituting a loan system through which books could be taken by Forest Service boats to isolated settlements. He was instrumental in securing the books and manuscripts of Judge Wickersham for the Alaska Historical Library and Museum. A lifetime bachelor, Heintzleman was a dapper dresser and something of a bon vivant, besides being a collector of Alaskan books and artifacts.

|

| Regional Forester B. Frank Heintzleman (U.S. Forest Service) |

Alaska Spruce Log

Program

World War II brought many changes to the Forest Service in Alaska. A large number of the staff were called to the armed services. Forest Service men cooperated with the military by reporting suspicious boats or planes or submarines. Army installations brought about an increase in wood production. At Yakutat a large airstrip was constructed, and the building of the base there increased timber sales from the national forests. With the building of a military base on Kodiak Island, a nearby source of timber was needed, and for the first time Afognak Island was used as a source for lumber. [4]

Probably most important of all, however, was the Alaska Spruce Log Program. One of the planes used by the British in raids over Germany during the early years of the war was the Mosquito bomber, a medium bomber made of plywood. It carried little armament but used speed and maneuverability for defense against flak and fighters. Spruce for these planes were logged on the Queen Charlotte Islands of British Columbia, just south of the Alaska Panhandle. As the war went on, however, demand exceeded supply and the War Production Board sent a request to the Forest Service for more spruce. The accessible supplies of airplane-quality Sitka spruce in Washington and Oregon had become depleted during World War I. James Girard, a Forest Service man who was an authority on spruce grading, went to Alaska to look for spruce stands. He reported that the Alaska forests contained enough spruce of high quality for a large-scale operation. Heintzleman asked the advice of Edward H. Stamm, logging manager of Crown Zellerbach, about the feasibility of the operation. He replied favorably, recommending that, rather than having the Army run the show as it had in the World War I spruce program, experienced loggers should get out the logs and sell them to mills specializing in spruce sawing and the production of airplane lumber.

|

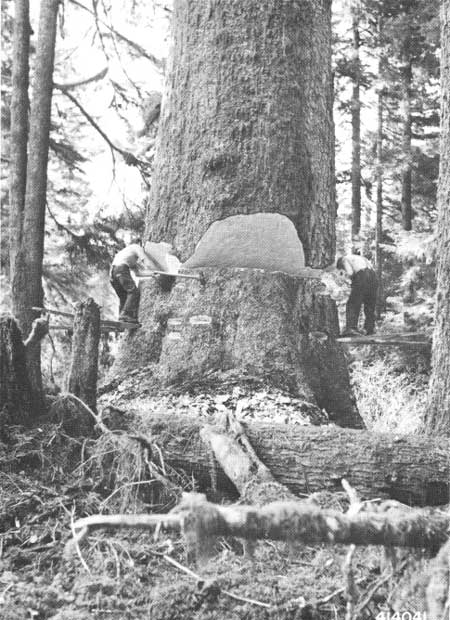

| James W. Girard, a cruising genius of limited education, visited Alaska in 1942 and reported that its Sitka spruce stands would support a vital wartime program for airplane lumber. The Alaska Spruce Log Program resulted. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The Alaska Spruce Log Program (ASLP) was set up as an agency on June 4, 1942; it was administered by the Forest Service and financed by the Commodity Credit Corporation. Its immediate objective was to produce 100 million feet of airplane lumber per year. Heintzleman headed the operation as regional forester, and Charles G. Burdick acted as general manager. William B. Ihlanfeldt was put in charge of the Seattle office as an assistant general manager. J. M. Wyckoff was made assistant manager in Alaska; C. M. Archbold, division supervisor, was put in charge of cruising; and R. A. Zeller, a former supervisor of the Tongass, acted as chief cruiser. The Forest Service kept four three-man parties in the field and, using Wanigan 12 as headquarters, cruised timber and located logging chances. Ray Kidd and Clarence Cotterell were scalers.

|

| Falling a giant spruce, 1941. (U.S. Forest Service) |

|

| Log pond at Coning Inlet sale, Long Island, August 1945. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The Seattle office was set up in the Joseph Vance Building. It furnished supplies of all kinds. Fred Brundage made timber sales to the mill men. Recruiting was done through the War Manpower Commission. Equipment was supplied by the ASLP and purchases expedited through a central purchasing office.

Field headquarters were set up at Edna Bay on Kosciusko Island, to the west of Prince of Wales Island. The Nettleton Logging Company brought in prefabricated wooden dwellings and laid out a two-mile truck road system—Spruce Street, Hemlock Street, and Alaska Way.

Burdick called on gypo loggers (small, independent contractors) in the Northwest, and they began moving to Alaska by the winter of 1942. Ed Buol, the first, brought with him six, 110-by-40-foot scows loaded with goods and machinery. These included two rock crushers, five 10-ton logging donkeys, six diesel donkeys, a village of prefabricated buildings, fifteen miles of steel cables, and fifty tons of food.

|

| Davis raft of high grade spruce logs nearly completed, 1944. (U.S. Forest Service) |

|

| J. M. Wyckoff photographed the Roamer taking Camp 9 in tow during the Alaska Spruce Log Program in 1942. (U.S. Forest Service) |

For this operation, the Forest Service contracted for logging, towing, and rafting. The operator got the logs to tidewater and towed them in flat rafts to Edna Bay, where they were made into Davis rafts 250 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 30 feet deep, each raft containing nearly a million feet of timber. (A Davis raft is an ocean-going log raft, more or less square in cross-section, not tapered like the Benson raft.) The rafts were towed by tug to the Puget Sound mills, hundreds of miles to the south.

At first the operation was planned for selective logging, high-grading only the better spruce that was suitable for airplane stock. However, Archbold recommended that the hemlock and lower-grade spruce be taken as well and shipped to local mills for use in defense construction in Alaska.

Nine camps were established, four of them A-frame operations and the others truck or tractor and arch. Four were floating camps with bunkhouses, cook-shacks, and washrooms. The others were built on shore. One was on the site of the old Indian village of Tuxekan, with totem poles and the chief's grave in the settlement. Buildings were prefabricated, insulated with Celotex, and set on stilts to keep them off the wet ground. Coal was used for fuel so that time would not be wasted in cutting wood.

|

| Preparing donkeys for loading on logging trucks, 1943. (U.S. Forest Service) |

In the camps, a horn awakened the loggers at 6 A.M. and the gut hammer sounded at 6:15. By 7, loggers were on their way by truck to the woods. Falling was done by power saw, usually on the hourly basis. Logs were yarded and loaded by donkey engine. At the A-frame operations, logs were brought in as far as 1,000 feet from a spar tree to the A-frame mounted on its raft.

At Edna Bay large headquarters were set up for the operation. These included houses for Forest Service personnel and for loggers and their families, a two bed hospital, a machine shop, and a radio-telephone link. At least 250 people lived in the village.

A fleet was assembled for the Edna Bay operation. The Forest Service vessels, Forester and Ranger 7, were used for administrative purposes. The Relief and Beaver were used as boom boats and the Pearl Harbor as an oil boat. For towing the flat rafts to the point where the Davis rafts were assembled, the Elsinore and Salmon Bay were used. For the Seattle run, the Gloria West and the Roamer, boats rented by the Forest Service, were put into duty. The Forest Service also chartered planes for inspections and for travel to Juneau or Ketchikan.

In March 1943 the first Davis raft loaded with airplane spruce reached Anacortes, Washington, towed in by the tug Sandra Foss. It contained more than 900,000 board feet of logs, including about 50,000 feet of western hemlock for experimental purposes. The logs averaged thirty-four feet in length and three feet in diameter at the small end, scaling about 2,000 board feet each. Around 38 percent of it was of top grade.

|

| J. M. Wyckoff photographed a crib raft of high-grade Sitka spruce embarked from Annette Island to Puget Sound in 1943. (U.S. Forest Service) |

For Angela C. Janszen, a young Forest Service statistical clerk, this was a period of high adventure. She had transferred from Washington, D.C., to the Seattle office of the spruce program and then, at Burdick's request, took a job as accountant and clerk at Edna Bay. She was initially the only woman on the Forest Service payroll there. Angela went to Edna Bay toward the end of March 1943 and lived in a twelve-by-twenty-four-foot prefabricated house consisting of living room, kitchen, and bath. Hers was one of the few bathrooms in camp, so it was frequently used by guests. She ate at the mess hall with the loggers and Forest Service staff. Her work was varied; in addition to clerical work, she helped out in the hospital and made a good photographic record of the operation.

Angela's "Sprucelogue"—letters home to her family—gives a singularly fresh and vivid account of the work, through the eyes of discovery. She learned the technical vocabulary of the loggers and what they meant by a schoolmarm, widow-maker, flunkey, cold deck, corks, A-frame operation, spar tree, and wanigan. She acquired a skiff and rowed around the area. She accompanied the brass when they arrived on official trips to the camps, took the loggers' children for walks, or went into the woods to watch the topping of a spar tree. There was a lively social life at Edna Bay, with poker a favorite pastime and dancing to music from an old nickelodeon. High points were the arrival of the mail boat with letters and packages from Sears or "Monkey Wards," the occasional visits of Father Matthew E. Hoch on the Coast Guard boat to celebrate mass, the unloading of barges carrying machinery, and rafts taking off for the south. Occasionally, she was able to take a flight in to Ketchikan where she visited Ward Lake, then an evacuation center for the Aleuts. Angela took an active part in the jokes and horseplay that mark any Forest Service community. She and others who ate at Table 5 in the mess hall formed the Order of Poland China. Here is one of their typical verses:

EDNA BAY

(Written by the cook after one of the loggers on the Alaska Spruce Log Program complained about burned bacon.)

Oh! The dark clouds frown

And the clouds swoop down

On the shores of Edna Bay,

While the Bull Cook's song

Rings loud and strong

In the wild Scottish way.

If the loggers howl,

And the loggers scowl

For each my heart is achin';

But who in hell

Would dare to tell

Who burned the breakfast bacon.

If the boss gets drunk

With the Whistle Punk

And the Buckers hold a meeting

Who gives a rap

For Wop or Jap

If we can have good eating.

We are sick of fish

For a Friday dish

And hot cakes in the morning.

Grouch on! Good Friend!

The bitter end

May come without warning.

It was, for Angela and the others who took part in the enterprise, a period of high purpose and high adventure.

By February 1944 the program began to come to an end. The War Production Board said that metal would take the place of spruce planes and that the cutting was to cease on March 15. The last rafts of logs were shipped out to Puget Sound or towed away by tug to the local mills, and the camps began to close down. By August 1944 Edna Bay, which formerly had a population of 250, was a ghost town, down to 15 men and 1 girl. Equipment was sold off—cats, miles of cable, donkeys, floating camps, buildings, mess halls, and the like. By October 1944 the operation was closed. In about a year and a half of existence, 38.5 million board feet of high-grade spruce was sent to the states, and 46 million board feet of grade 3 spruce and hemlock went to local mills. Heintzleman, meanwhile, once the operation was finished, renewed his search for investors in pulp production. [5]

Possessory

Rights

During Heintzleman's term of office, his ambition to establish a pulp industry in Alaska was badly complicated by the question of Native claims and possessory rights. This issue had come up during the administrations of Langille and Weigle. By Flory's administration, it became a major concern. The story is complicated, involving as it does legal questions, administrative policies, ethnic aspirations, and personal ambitions. It involved relationships of the Forest Service with the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANE), Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS), and the changes that took place within these organizations.

Theodore Roosevelt had been interested in the status of the Native Americans in Alaska and asked Lieutenant George Thornton Emmons to make a report. Emmons did so, stating that the Indians in southeastern Alaska were a relatively advanced class of people, capable of self-support and mainly needing supervision, education, and moral support. They worked in mills, mines, and lumber camps and were able to bridge the gap between civilization and tribal life. They needed, however, technical education, hospitals and dispensaries, and legal status to acquire land and practice professions. Roosevelt echoed these recommendations in his State of the Union message in 1904. [6]

Several land laws were passed with application to Indian rights. Indians were entitled to take up land under the Forest Homestead Act of June 11, 1906. In addition, an act of May 7, 1906, permitted the secretary of the interior to make allotments of up to 160 acres to Indian family heads. No money was appropriated, however, to carry on the survey work. Secretary of the Interior James R. Garfield urged its implementation in 1908, and Richard A. Ballinger, in 1911, secured a new bill repeating the principles of the old and setting up machinery for acquiring land through the General Land Office. In 1915 some Land Office surveys were made for this purpose in the Tongass National Forest, and Land Office officials worked out arrangements with the Forest Service to avoid conflicts with the surveys made under the Forest Homestead Act. [7]

The Forest Service men concerned with Indian claims developed common-sense practices. Native villages were surveyed and roads built under both revenue-sharing statutes and special appropriations. Indian claims of prior occupancy and consequent title were based on physical evidence, such as garden spots, graves, fish houses, and smokehouses. Such occupancy did not need to be continuous. Areas occupied by Indians prior to creation of the Tongass National Forest, and then abandoned, could be reopened for entry if the Indian allotment were valid. If a tract had no history of prior use, it could be opened for settlement under the Forest Homestead Act. [8]

During the 1920s there was a great deal of classification but little real difficulty in regard to Indian land claims. Two crises did arise. One, relating to the J. T Jones claim to a pulp mill site, has already been described. Another related to a fox-farming project on the west side of Prince of Wales Island.

In 1921 a petition reached District Forester Flory, signed by 180 people in the Anguilla Island area. They protested the leasing by the Forest Service of the island for fox farming, alleging that they had used it as a campsite and garden spot. Flory called for a field investigation. Meanwhile, H. H. Butler, vice-president of the Anguilla Island Fur Company, protested the trespass of individuals on the island. He stated that the leasee could not physically prevent people from landing but that he had a right to have his fur farming free from interference. The Forest Service suggested that he post trespass notices. At the same time, E. W. Nelson, chief of the Biological Survey, informed Chief Greeley that he was having similar reports from islands leased by his agency.

In a long letter to Greeley, Flory outlined the problem. Alaska, he reported, was overrun by a "thieving class of whites and natives who seem to make their living by robbing fish traps, slaughtering game for sale, bootlegging, robbing launches, poaching on fox farms and similar acts of depredation." Flory felt that the problem was one for the Justice Department. The Forest Service could give aid but already had too many demands on its boats. The governor, attorney general, and U.S. marshal, he complained, insisted on the right to use Forest Service boats for bringing to justice people accused of civil offenses. Flory recommended that the fox farms keep armed guards on duty, as did fish-trap owners, and that the fur raisers organize for mutual protection. J. M. Wyckoff made a field examination and recommended that the leases be cancelled. The San Lorenzo group of islands, of which Anguilla was one, was, Wyckoff reported, an Indian fishing site with 2,000 seasonal campers and 20 buildings. It was the only safe anchorage in the vicinity. Merritt, meanwhile, suggested that the fur company fence off Indian garden sites on the island. The lease was canceled on the basis of prior Indian use. [9]

By the 1920s some Natives were playing parts in territorial politics, electing one of their own to the territorial legislature. The Alaska Native Brotherhood acted as a pressure group to insure civil and political rights for Indians. Territorial Delegate Anthony Dimond, who served from 1933 to 1944, was particularly interested in Indian affairs. The Wheeler-Howard Act of 1934 and supplementary legislation in 1938 gave to the secretary of the interior the right to set up reservations and to enlarge existing ones but forbade ownership in severalty. The creation of a reservation, however, had to be endorsed in a special election by 30 per cent of the Indian residents thereon.

|

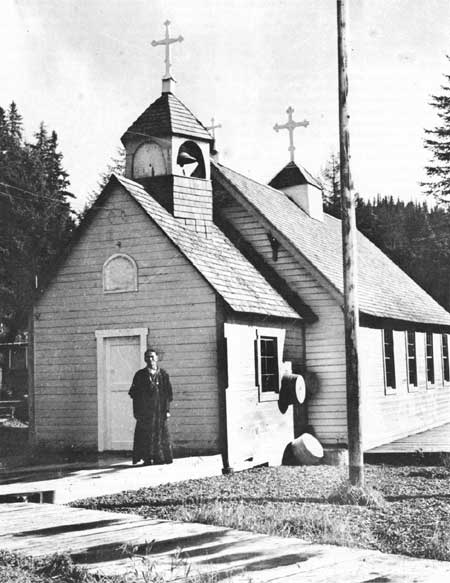

| A. W. Blackerby photographed Steve Vlacoff, lay priest, in front of the Greek Orthodox Aleut Church at Chenega, Chugach National Forest, 1946. (U.S. Forest Service) |

In southeastern Alaska local reservations were used largely for school purposes. Native villages were governed by tribal councils, and self-government, rather than wardship, was their goal. During the 1940s, however, a new concept of Native rights was adopted by the Department of the Interior. This was an interpretation of possessory rights giving to the Indians lands or waters on which their ancestors had hunted or fished; these would include virtually all of southeastern Alaska. Ickes appointed R. H. Hanna, a former judge of the Supreme Court of New Mexico, to hear the testimony on native possessory rights, especially in regard to Kake, Klawock, and Hydaburg. Hanna's report did not support the departmental views, but Ickes reversed Hanna and in a July 1945 ruling declared that the public domain was both land and water and that submerged lands were available for Native possession. He asked that land to the extent of 176,000 acres be reserved for three villages. Decision on an additional 2 million acres was postponed. Ickes further affirmed the rights of the Indians to sue under the Haida-Tlingit Jurisdictional Act of 1935, which entitled Indians to sue in the court of claims for any claims they might have against the United States. [10]

The judgments of the Department of the Interior were alarming to the Forest Service. If Ickes's views were realized, the whole timber industry in southeastern Alaska would be jeopardized. Pulp companies would be discouraged from making investments, since the right of the Forest Service to make timber sales would be in doubt. Heintzleman expounded his views in a letter to Harold Lutz. The effort to give Indians title to southeastern Alaska, he wrote, was "under the theory that they are the owners of all the lands and resources through their heredity of aboriginal rights and that these rights have never been extinguished by the federal government." Heintzleman blamed the Department of the Interior for the matter, particularly Secretary Ickes. "With the assistance of the Interior Department, and on the basis of some legal opinion given by the Secretary of the Interior by the Solicitor's office of that department," he wrote, "each village, as S. E. Alaska has never had a tribal organization, has made application for hundreds of thousands of acres of land and tidewater fishing areas that blanket all the fishing sites and large areas of trolling grounds." He went on to summarize the existing laws under which the Indians could acquire land. He concluded, "The thought is often expressed by private citizens that the move to set up vast Indian reservations in S. E. Alaska is based, in large part, on a desire to eliminate the National Forests in Alaska." [11]

In order to permit timber sales without danger of the sales being terminated because of clouded title, a Tongass timber bill was introduced into Congress. It provided that the secretary of agriculture might make contracts for timber sales but that receipts from the sales be put in a special fund to remain untouched until the issue of Native claims was settled. Senator Warren Magnuson of Washington and Delegate E. L. Bartlett of Alaska played a major part in developing the bill. The draft bill was agreed on by the departments concerned—Agriculture, Justice, Interior, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The Tongass Timber Act was finally passed on July 27, 1947. [12]

Pulp Mills at

Last

During Heintzleman's administration the timber cut increased from 43 million board feet in 1936 to 60 million in 1950. Heintzleman continued his search for pulp investers, and his efforts were finally successful. American Viscose Corporation, the largest manufacturer of rayon in the United States, became interested in the possibilities and formed a combination with a Bellingham firm, Puget Sound Pulp and Timber, to form the Ketchikan Pulp Company and to set up an operation at Ward Cove. There were numerous obstacles to circumvent. The site of the mill was the former location of a real estate speculation called Wacker City, after its founder Eugene Wacker. When in need of money, Wacker had sold lots, sometimes selling and reselling the same lots numerous times and letting each purchaser think he had clear title. Local attorneys were retained by the company, titles were finally cleared up, and options on the land obtained. A preliminary award was made on August 2, 1948, and the final contract was signed on July 26, 1951. The mill agreed to purchase 1.5 billion cubic feet of timber on a fifty-year contract, which called for 85 cents per cubic foot for wood cut for the manufacture of pulp prior to July 1, 1962, and for review by the Forest Service every five years. The company also agreed to pay $3 per thousand board feet for spruce, $1.50 for cedar, and $2 for other species. [13]

Water pollution was a major concern for the Forest Service, and intensive studies of this problem were made on each of the sites examined for possible pulp mills—Sitka, Ketchikan, and Wrangell. These studies were carried on from 1948 to 1956. Heintzleman worked closely with the Alaska Water Pollution Board. Edward G. Locke, a chemical engineer from the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, and Gardner H. Chidester, chief developer of pulp and paper for the Forest Products Laboratory, gave him advice. Raymond Taylor of the Alaska Forest Research Center and officials of the Fish and Wildlife Service were consulted about the possible effect of logging on the salmon streams. Locke and Chidester reported that if a magnesium-base process were used at Ketchikan, there would be no damage. But they recommended that the effluent pipeline extend into the Tongass Narrows. They saw little possibility of ecological damage at Wrangell and felt that the projected site in Sitka was a good one. The question of water pollution was also raised by Samuel Ordway of the Conservation Foundation; he called on C. M. Granger for information and later wrote to Heintzleman about the matter. Heintzleman told of his conference with the Alaska Water Pollution Board, and Ordway was apparently satisfied. [14]

The first pulp mill was the fruition of long-standing dreams. These included the early suggestions of Bernhard E. Fernow, made after his first trip to Alaska on the Harriman expedition; the recommendations of William A. Langille after his long and lonely trips through the archipelago; the studies made by William Weigle; the arduous work of George Drake and Roy Barto, who set up stream-gauging stations; the timber estimates of Kan Smith; the aerial mapping of the Navy; and above all, the efforts of B. Frank Heintzleman. They included frustrations, such as the failure of the Speel River plant. The mill was a major triumph for Ketchikan. But Heintzleman's administration saw new developments in timber and pulp production that arose from immediate political, trade, and economic conditions.

As a result of World War II, Japan lost a major part of the timber resources (namely, Manchuria and Sakhalin) on which she had relied for domestic use and manufacturing. The postwar military government in Japan set up a system of forestry within the country, but the amount of available timber was insufficient. Japanese interests first turned to the Philippines as a source of round logs, but the Philippine government curbed export in order to develop its own industrial forestry. In 1951 Japanese groups approached the Forest Service for sales in Alaska. Their suggestion was that the Japanese furnish the labor and build the logging facilities. The Forest Service refused on the grounds that it wanted to use Alaskan timber locally. The next year, on February 22, a formal petition was made to the supreme commander of the allied powers, asking again for softwood timber from Alaska to be harvested by Japanese workers. It was pointed out that the timber deficit for home industry amounted to 3 billion board feet, plus 400 million cubic feet of timber needed for fuel. The plea was considered by the Defense, Interior, Agriculture, Labor, and State departments, but it was turned down on a variety of grounds.

In October 1952 a Japanese mission came to the United States to investigate the possibilities of a mill to export sawed timber and of a pulp mill in Alaska. They were told that the enterprise must meet specified conditions. It would have to fit into national and regional Forest Service timber-sale policy and meet sustained-yield standards. It would have to aid in the economic development of the territory, which meant compliance with the primary processing requirement. The enterprise would also have to be an American corporation and get the timber required by competitive bidding.

By 1953 the Japanese were ready to act. They sent a team of technical experts to the United States to examine alternative mill sites. The Japanese were well received in southeastern Alaska and were given highly favorable publicity in the press. They particularly liked Sitka because it had a good location at Sawmill Creek, a power site, and a climate and atmosphere attractive to the Japanese. They were astonished at the waste in American wood processing and asked if the waste could be baled and shipped instead of being discarded. Public sentiment in Alaska grew in favor of the venture; Charles Burdick made talks before the Chamber of Commerce in Juneau and O. F. Benecke, president of the chamber, was one of its strongest supporters. He performed yeoman service by writing to other chambers of commerce in Alaska, informing them of the project and giving reassurance. Only from the Pacific Northwest came objections. Representative Walter Norblad of Oregon protested the project. In a public letter to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, he characterized the affair as "improper," and "an outgrowth of a secret agreement FDR had made at Yalta" to give the Russians Sakhalin Island. Development of such a mill, he said, would hurt the Oregon economy, since Oregon mills needed the Japanese market. However, the Alaskan press backed the project, and the territorial Senate supported it by resolution.

In September 1953 the contract was finally made. A Japanese company, Toshitsugu Matusi, formed the Alaska Pulp Development Company, incorporated in the United States and financed in part by a loan from the Export-Import Bank. The plan called for building a large sawmill and a pulp mill at Sitka. Meanwhile, by the end of 1953, wood scraps were being compressed and shipped to Japan. By 1959 the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company was in operation. [15]

Research

Forest research in Alaska got under way during this period. In 1928, at the time Crown Zellerbach was considering pulp production in Alaska, Congress passed an authorization for a research center in Alaska. No funds were appropriated, however. In 1948, when prospects were bright for a pulp mill, Congress appropriated $50,000 to be used for research in Alaska. The Forest Service decided to set up the Alaska Forest Research Center, and Raymond F. Taylor won the job of director.

As noted in the previous chapter, Taylor had first arrived in Alaska in 1925. Working as a scaler, he began research on defect analysis and extended the research interest, shared with Jim Walley, to growth and yield studies on Admiralty and Prince of Wales islands. These early years of forestry work enabled him to travel widely over southeastern Alaska. He wrote several articles for forestry journals and published a pocket book of Alaska trees. After holding research positions at several forest experiment stations and in the Washington Office, Taylor returned to Juneau in 1948 to take up the job of director of the new research center in the regional office.

An early problem was to keep the research center under the Branch of Research. There were several who wanted the regional forester to be in charge—among them B. Frank Heintzleman. Upon arrival, Taylor discovered that Frank had just found out that Ray Taylor's nearest boss was to be in Washington, D.C. This may have caused the sudden unavailability of a ranger boat that had been promised for research use. One of the older boats, however, the Ranger 7, was provided for the cost of running and maintaining it. After a brief interval to store equipment and files in a corner of the sign shop, and to find living quarters for the family, Taylor started fieldwork.

No new boats had been built during the fourteen years Taylor had been away, so he knew the Ranger 7 well. It was the first diesel boat built for the Alaska Region. A skipper-cook was hired, and Richard M. Godman was transferred to Alaska from the Massabesic Experimental Forest in Maine. In October, Betty Corey, a secretary in the Division of Forest Management in Washington, D.C., transferred to the research center. By then, two rooms in the "crewhouse" at the sub-port, a part of the Admiralty Division set of buildings, was loaned to the research center. The U.S. Geological Survey shared the quarters. These frame buildings were on a gravel fill, formerly part of the tide flats. The CCC had laid the sewer lines level; when the spring and fall tides came, the toilets backed up. During the war, the National Guard had occupied these buildings. Whether "crewhouse" refers to them or to CCC groups is unknown.

As the Alaska Forest Research Center grew, it gradually took over the whole crewhouse and then moved to a leased office uptown. Soon after Taylor's retirement in 1959, the new Federal Office Building was constructed, and all Forest Service agencies moved into it. The name was changed to Northern Forest Experiment Station, and the forester-in-charge became a director. Later still, the station was taken over by the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station in Portland and renamed the Institute of Northern Forestry.

According to Taylor, research organizations are most productive when they have small staffs, simple quarters, and are hard up for money. When expansion comes, overhead grows and the "idea-men" are promoted to an overheated office with good-looking secretaries and have no time for fieldwork.

The first job was to bring old work up to date. Old sample plots, transects, and reproduction study areas were revisited. At Traitors Cove reproduction plots established on land clearcut in 1924 were remeasured. Rod-square plots that had hundreds of two-inch tall seedlings in 1926 now had one or two trees, but they were ten to twelve inches in diameter. The yield tables on which the cutting rotations were to be based were checked by actual growth on the plots over a twenty-year period, and the tables were found to be fairly accurate. Areas clearcut in the early 1920s were almost impenetrable stands of second-growth, with trees six inches to a foot in diameter.

During the next few years, the Maybeso Experimental Forest was established at Hollis, where the first pulp timber cutting was to start. Here studies of regeneration before and after cutting of a large area were begun. Regional Forester Heintzleman wanted an answer to one question as soon as possible: would clearcutting on watersheds of salmon streams ruin these streams for spawning? There were many who were certain that this would be the result of any logging near such streams. The Hollis area had three salmon streams—Maybeso Creek, Indian Creek, and Harris River. A study was set up with the cooperation of the Water Division of the U.S. Geological Survey, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Fisheries Research Institute of the University of Washington. After five or six years, it was apparent that the salmon were still spawning in as great numbers as ever, although the usual variations due to unknown causes occurred. At the conclusion of logging in these large watersheds, a yes or no answer should have been broadcasted, but by then there were many detailed minor studies—siltation, egg hatch, etc.—and the main theme seemed to have been forgotten. It could be that caution prevailed until the last site-study was concluded, and these have a way of expanding into smaller and smaller fields.

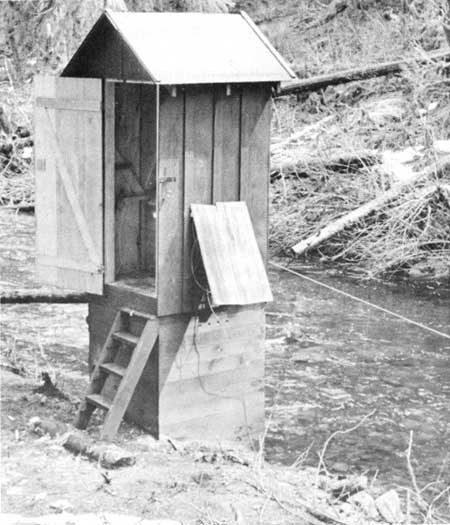

In the first years the men of the research center constructed their own wanigan on a small scow loaned to them by the Southern Division. Materials were scrounged, and the plumbing and electrical work was done by the technical foresters, boat skipper, and summer helpers—ingenious men who made a little money go a long way. Larry Zach, formerly a division supervisor, ramrodded these jobs. Stream-gauge houses and cable cars for measuring flow were built by putting in long days.

After the Ranger 7 become worn out from long service, a twenty-six-foot "speedboat" was bought, but its twin engines could not force it against a light wind. It rode like a duck. This was sold and money was finally obtained to build a good work boat, the Maybeso. It was the size of the Ranger boats, built for hauling materials, towing, and living. Harold Andersen, formerly division supervisor at Petersburg and with long Alaska experience, designed it, supervised its construction, and ran it up from Seattle when it was ready.

The research center was not expected to do work in Alaska's interior, but some research on the effects of fire, which burned at least a million acres per year, seemed necessary. A field analysis was made by Taylor and R.R. Robinson of the Forestry Division of the Bureau of Land Management. Professor Harold Lutz of Yale, who had made a study of this nature in southern New Jersey, was employed for summer work. The study ran four seasons with the cooperation of the Bureau of Land Management's Fire Division.

Results of research were published as articles in technical journals, station notes and papers, and in annual reports. The report for 1955 described work on the Forest Survey, which eventually covered all of Alaska's forestland; a black-headed budworm survey and study of the hemlock sawfly; silvicultural studies of seed dispersal, seedbed types, and soil temperatures in relation to seedling growth; and miscellaneous work on long-log scaling, fire weather, and chemical brush control. [16]

|

| The Forest Service has studied the effects of logging on salmon streams for many decades. This stream gauge on the Old Tom Creek Natural Area (part of the Society of American Foresters' system), here photographed in 1950, has been in operation since about 1940. (Forest History Society) |

|

| A fish-counting wier at Old Tom Creek Natural Area, August 1951. A gate in the wier is raised to allow adult salmon to pass up stream; fry that pass downstream are counted in order to determine survival rates. Research here has been conducted since about 1940. (Forest History Society) |

Administration, Lands, and

Amenity Values

As an administrator, Heintzleman clung to the old ways of keeping the division system and a relatively small staff. The old familiar officers—C. M. Archbold (who played an important part in helping to develop the pulp mill sales), Alva Blackerby, Charles Burdick, Spencer Israelson, and Ralph Ohman—were the mainstays of the staff. Some retired—J. P. Williams, who had been a tower of strength in the organization, both in timber cruising and in wildlife management, and E. M. Jacobsen, who served long in the Chugach as ranger and boat skipper. His district suffered from the usual chronic lack of funds, especially needed in recreational planning. The boats were growing old, and planes were not always available. In the period between 1934 and 1948, not a single new boat was added to the Forest Service fleet.

In 1931 the regional office in Juneau was moved from the Goldstein Building to the Federal and Territorial Building. In addition, more land was acquired for a warehouse site at Juneau, on the tidelands. In 1921 the Forest Service had acquired some property from the Alaska Road Commission and had built a wharf, which was used not only by the Forest Service but also by the Coast Guard and other boats. CCC labor was used to raze the old buildings and to build a rock fill, construct a garage, and a warehouse. These were loaned to the Army in 1942 but came back to Forest Service ownership in 1946. [17]

A variety of problems relating to lands arose during the Heintzleman administration. One has already been dealt with, that of possessory rights and Indian reservations. In addition, a series of bills was introduced in Congress, usually sponsored by Representative William Lemke of North Dakota and designed to give war veterans homesteads in the national forests. Title would be granted on seven-month habitation and the building of an eight-by-ten-foot cabin. They were similar to other bills introduced in the period after World War I. None of them passed. [18]

A major change came in 1941 with the establishment of the Kenai Moose Range. The proposal had been initiated by W. A. Langille in his 1904 report on the Kenai. The attempted agricultural boom of Andrew Christensen at Anchorage, however, stopped this movement and helped force the Forest Service to relinquish a great share of the area. But agriculture did not thrive there. Ira Gabrielson, as head of the Fish and Wildlife Service (successor to the Bureau of Fisheries and the Biological Survey), pressed for creation of a game refuge in the area and was successful in getting it by 1941. There was close collaboration with the Forest Service in the Kenai, as well as with the Alaska Game Commission, in regard to fire control study of the moose habitats, regulation of hunting, and apprehension of poachers. [19]

Fire remained a continuing problem in the Kenai. The Alaska Railroad by this time had become more cooperative than in the past. Right-of-way burning was controlled, and section gangs were given suppression and presuppression training. However, the main problem was the coal-burning locomotives. The locomotives were old and decrepit; they had barely enough power to get over the summit under the best of circumstances and could not do so with spark arresters. There was no diesel equipment; the railroad officials stated that the roadbed was not heavily enough ballasted to carry the heavier equipment.

Another problem in the Kenai, one that grew with the war, was that of mining claims. The government had declared a moratorium on assessment work on claims for the duration of the war, and the moratorium was extended. Consequently, fraudulent or dubious mining claims flourished, not only in Alaska but also in the states. Those in Alaska were commonly located on the Kenai River and served as fishing cottages or summer homes for the claimants. They were also used for commercial purposes. Afognak Island was used increasingly as a recreation center for Army personnel during this time. The buildings of the Afognak salmon hatchery were utilized by the Army as fishing or hunting camps for the troops stationed at Kodiak. [20]

Some eliminations were made from the Alaskan national forests during this period, mostly at the recommendation of the secretary of agriculture or for transfer to the Bureau of Land Management. In the Tongass these included areas for suburban development, highways, small homesites, public services, and the like—places where national forest values were outweighed by settlement values. Such areas were recommended for elimination by the secretary of agriculture in June of 1950 and eliminated on January 25, 1952. The amount eliminated from the Tongass amounted to 29,000 acres, mostly on the outskirts of Juneau, along the Glacier Highway, and near Ketchikan, Craig, Petersburg, Wrangell, and Sitka. At the same time 76,000 acres were eliminated from the Chugach. These included areas along the railroad, on the highway, and on the north side of Turnagain Arm, for disposal under public land laws and the Small Tracts Act. [21]

There were a few sporadic revivals of the Admiralty Island affair. Writer John M. Holzworth did not give up his struggles to make the island a bear sanctuary. The issue came up from time to time between 1944 and 1947, but the reports of Victor Cahalane, Joseph Dixon, and Frank Been of the Park Service were instrumental in preventing any real new flurry of interest in the matter. During Heintzleman's administration, other national parks were also considered by the Forest Service and the National Park Service. Newton Drury, director of the Park Service, gave some consideration to creation of a national park in an area south of Juneau involving Tracy Arm, Endicott Arm, and Fords Terror. At Governor Gruening's suggestion, studies were also made of the areas around Mount St. Elias and in the Aleutian Islands. [22]

|

| A homestead along the Unuk River on the Tongass National Forest, 1941. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Still other areas were considered for special treatment. The Skagway Chamber of Commerce suggested that a tract in its vicinity be added to the national forest, primarily for recreational values. The area was rich in history from the gold rush days of 1898, when the two main trails to the interior started from Skagway and Dyea. Wellman Holbrook and W. A. Chipperfield suggested that the area be added because of its historical value, containing trails, Indian antiquities, and the like. The plan was backed by Leon S. Kneipp in the Washington Office but finally was abandoned because there were no real timber values in the area. Harold Lutz, during his research in the interior in 1952, recommended to inspectors passing through the creation of national forests to the north of the mountains in the Prince William Sound area and in the birch area along the Talkeetna River. He also recommended that areas be set aside as an experimental forest on the Chugach National Forest. [23]

During Heintzleman's administration there was much discussion of primitive areas, amenity values, and natural areas. In planning his timber sales, Heintzleman had taken into detailed consideration matters of pollution, game management, and commercial fishing. A further consideration was preservation of scenery along the steamboat lanes. He recommended that cutting zones be established along the main steamship lanes that were less than 2.5 miles wide. Narrows less than 1,000 yards wide would be closed entirely to cutting. He felt that these areas should have special treatment in order to preserve scenic values for travelers. The method would depend on the terrain. [24]

There was continuing interest during this period in classifying wilderness and natural areas. In 1949 the Society of American Foresters, through its Committee on Natural Areas, recommended that such areas be set up in Alaska by the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management. [25] Wilderness areas, however, were much larger in size. The idea was given impetus by the Department of the Interior under its aggressive secretary, Harold Ickes. But the wilderness idea had been under consideration for some time in Region 10. Flory's reply to Chief William B. Greeley was that there was no problem in Alaska; there was enough de facto wilderness to last indefinitely, especially above the timberline. Chiefs Stuart and Silcox also requested consideration for wilderness, the latter emphatically stating that public sentiment was for wilderness areas and that the Forest Service would have to recognize the fact. He urged each region to begin classification work. [26]

In Alaska consideration turned to the Tracy Arm area south of Juneau and to the Walker Cove area south of Ketchikan. Heintzleman was told by the Washington Office that it favored wilderness classification. But W. A. Chipperfield, who was in charge of lands, objected on the grounds that transportation by water was necessary. After the waterways were excluded, he argued, there would not be enough land left to create both buffer zones and wilderness areas. He recommended instead that scenic areas be established, giving the same protection. He said that classification as wilderness wouldn't "get to first base with the Wilderness Society." Heintzleman agreed with this reasoning, and the two units were classified as scenic areas under Forest Service regulation U-39a. [27] The Walker Cove Rudyerd Bay Scenic Area would become part of a larger Misty Fiords National Monument in 1978.

Throughout this period the Forest Service cooperated closely with the Alaska Game Commission and with other federal agencies on matters of wildlife and fisheries. A major problem over the years had been protection of the Dolly Varden, a fish commonly thought of as a trout, though actually a char. As early as 1917, W. G. Weigle had protested the taking of Dolly Varden by seine without permit. Fishermen defended the practice on the grounds that the Dolly Varden ate salmon eggs, but Weigle felt that there was overfishing nonetheless. On Karta Lake one fisherman took 1,600 pounds by seine. Regulations were set up permitting such fishing only on salmon streams. The question arose again two decades later when there was an increase in commercial fishing for Dolly Varden. Heintzleman reported to Delegate Anthony Dimond that the Forest Service was not responsible for fish—that was the job of the Bureau of Commercial Fisheries and the Congress of Sport Fisheries. Heintzleman believed, however, that the Dolly Varden was a game fish desirable for future recreation. He wanted to discontinue the use of fishtrap permits on the national forests, holding that cutthroat trout and steelhead, as well as Dolly Varden, were all being caught and sold. Dimond intervened in the matter, and commercial fishing for Dolly Varden was discontinued on January 19, 1940. [28]

Fish and game matters came up in other areas, too. The bear management program on Admiralty Island was continued successfully—the Forest Service working closely with the Alaska Game Commission. Lloyd W. Swift, chief of the Forest Service's Division of Wildlife Management, worked out guidelines for pollution control in regard to projected pulp cutting and mills. W. A. Chipperfield became the Forest Service representative on the Alaska Game Commission. Its discussions involved a variety of problems: the effect of multiple-use management on wildlife habitat; disposal of pulp-mill waste to prevent damage to aquatic life; studies on predators and predator-prey relationships; management of the Afognak elk herd; and cooperative studies with the Fish and Wildlife Service on the management of the Kenai moose herd. [29]

|

| Trail to Winstanley, 1958, now part of Misty Fiords National Monument on the Tongass National Forest. (Rakestraw Collection) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

10/history/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 06-Mar-2008