|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 7

The Greeley, Hanson and Howard Administrations, 1953-1970

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way.

Charles Dickens, A Tale of Two Cities

The Politics of Conservation,

1953-1968

The historian who tackles the recent history of the Forest Service—that is, the history of the period during the last twenty years—finds himself in strange terrain, where the bearings are confusing, the topography rough, and the lay of the land hard to determine. It was a period of transition from extensive to intensive management, with both a larger amount of money spent and a greater productivity; science and technology were reaching new levels in their application to the management of natural resources. It was a period of brilliant legislative achievements, such as the Wilderness Act and the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act—both efforts to formalize the goals and achieve the aims of the new era. It was also a period of bitter political and administrative infighting in which the integrity of the Forest Service, and even its very existence, was threatened by small-minded politicians, administrators, and powerful pressure groups.

New forces on the American scene made themselves known. The "grab-and-get" element, desiring removal or reduction of controls so that they might achieve unchecked exploitation of the public land, lobbied in Congress and placed national and regional officers under great pressure. On the other side, recreational groups also harassed the resource managers. Mass recreation came of age after 1952, and the land under control of the resource agencies was placed under increased pressure by the users of the land. During the previous era, the CCC had done a great deal of work providing campgrounds, roads, and other recreational facilities. These served well during the war years, when travel and use of the national forests and parks was light, and during the period immediately after the war when these had little use. With the 1950s, however, outdoor recreation vastly increased, and pressure on aging facilities became intense. In addition, the new generation of recreationists had grown up during the Depression and the war; it had little acquaintance with the outdoors and outdoor etiquette. Vandalism increased, and there was increased need for interpreting the outdoors to the public.

Another force was the wilderness elite. Concerned with the preservation of wilderness areas in pristine condition, the advocates formally separated themselves from the general run of recreationists and sportsmen. Learning that noneconomic groups flourish in times of crisis, they managed to establish an almost continual crisis atmosphere. There was a tendency toward polarization among the groups themselves: the mass recreationists demanded increased facilities, and the wilderness elite opposed them. There were the old type of recreational groups, such as the Mazamas and the Mountaineers, who had worked with the Forest Service as advisory groups, and the newer and more militant bodies, such as the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth, who rejected the advisory group approach and sought remedy through legislation and the courts. The emotional geology of the era would show a complex combination of factors: the slow sedimentations that represent continuity with the past, and the violent eruptions that change the structure of the landscape and leave behind them craggy outlines persisting even after the immediate disturbance has passed.

Dwight Eisenhower's election in 1952 marked the end of a long period of Democratic domination. Eisenhower came to office pledged to economy in government and governmental reorganization. He utilized a staff system and delegated authority to a greater extent than any president before him. His cabinet members in the area of resource management reflected the conservative views and the businessman's attitude of the new regime.

The secretary of the interior was Douglas MacKay, chosen largely because he came from a western state (Oregon) and was a staunch and conservative Republican. Eisenhower's secretary of agriculture was Ezra Benson, an honest, narrow conservative whose main effort was trying to find an alternative to the farm price support policies that would be both economically respectable and politically acceptable to the farming community.

To many conservationists, the new regime seemed determined to turn the clock back. "Conservation: Down and on its Way out" was the title of an article by Bernard De Voto in Harpers, and his summary indicated his thesis. The Tidelands Act had given millions of acres of oil land to the states; the Soil Conservation Service had been reorganized and weakened; and many career men had been put on "Schedule C," which weakened their tenure under civil service. Plans were made to alter the wilderness areas and national parks by dam building. Stockmen continued their pressure on the Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). Governmental reorganization was discussed, with recommendations to take some of the research functions from the Forest Service and to remodel and transfer the agents to the Interior Department.

|

| Richard E. McArdle, a Ph.D. forester, headed the Forest Service from 1952 to 1962. Immensely popular, he charted new directions dictated by postwar circumstances—notably more intensive forestry and better relations with the forest industries. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The Forest Service was fortunate in having the right man in the office of chief in the person of Dr. Richard E. McArdle. A professional forester of great experience, equable in disposition, with both firm adherence to principle and a great bargaining ability, he was precisely the right man for the time. He dropped his predecessors' plan for federal regulation of private cutting, a plan that tended to antagonize the lumber interests, thus ending a controversial issue that had been before the forest interests for thirty years. He fought successfully the efforts to reorganize the Service and transfer it, enlisting the aid of senators and representatives in this task. He increased the number of wilderness areas in the national forests and encouraged regional foresters to extend their recreational activities, especially in new directions such as winter sports. A Research Advisory Committee was set up, research activities were enlarged, and control over research on forest insects was transferred from other agencies of the Department of Agriculture to the Forest Service. The Timber Resource Review, a national study started in Watts's administration, completed its findings in 1958 with publication of the monumental Timber Resources for America's Future. McArdle wrote, "The report should convince the reader that the United States is not faced with an acute timber shortage. There is no 'timber famine' in the offing, although shortages of varying kinds and degrees may be expected."

As sustained yield had been a major emblem of the Watts administration, so multiple use became that of McArdle. Articles and memoranda on multiple use as a solution to the national forests' response to increased pressure of man on resources became a major concern of the Forest Service administration. The culmination was the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of June 12, 1960; signed by Eisenhower, it became Public Law 86-517. [1]

As chief, McArdle was aware of the increased use of the national forests during the 1950s. Timber sales increased as private land was cut over. Mining claims were pegged out in many of the national forests, endangering timber as well as water flow. That water for domestic use and irrigation was needed in greater quantities was a matter of growing concern to the Forest Service; more than half of the water in the western states originates in the national forests. There was also growing pressure among user groups, including those who wanted priority or exclusive use for one group. These included wilderness lovers, recreationists, town fathers interested in city watersheds, stockmen, and lumber interests. There was also pressure to overuse the resources. Some overgrazing and overcutting had taken place during the war years, and there had been many questionable mining claims that went unchallenged. Other pressures in regard to Forest Service administration came from outside. McArdle sought advice from both outside and within the agency, and eventually he decided on legislative action. [2]

Edward C. Crafts has told in fascinating detail the story of the Multiple Use Act. There was difficulty with the timber interests because the act failed to give priority to timber and water. The Sierra Club fought the bill vigorously because it failed to give wilderness an equal status with recreation. Several senators, notably William Proxmire, Hubert Humphrey, and Philip Hart played important parts in getting the bill passed. Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society, Ira Gabrielson, former head of the Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bernard L. Orell of the Weyerhaeuser Company played large parts in helping the bill through Congress.

The act is a legislative directive to the Forest Service to give equal concern to all the resources mentioned—recreation, timber, watershed, range, and wildlife—in planning for use of the forests. Mining was deliberately omitted. It does not forbid single or dominant use but simply asks that in planning the Forest Service give equal consideration to all these resources in combinations that will best serve the people. McArdle's interpretation, expressed at the Fifth World Forestry Congress in Seattle in the fall of 1960, stressed giving equal weight to each of these uses and to planning and coordinated activity. [3]

As Eisenhower's term of office continued, the pressures on the Forest Service lessened. MacKay left Interior in 1956 to run for Wayne Morse's senate seat; he failed to be elected and left public life. He was replaced by Fred Seaton of Nebraska, a man with a fair conservation record. The Republican dominance in Congress continued for only two years. Several senators and representatives who were markedly friendly toward forestry and conservation came into office.

A bill of almost equal importance, ultimately the Wilderness Act of 1964, was also begun during this period. Concern for wilderness had grown up with the movement for forest conservation. Groups like the Mazamas, Oregon Alpine Club, Appalachian Club, and Sierra Club had played a large part in the creation of the early forest reserves. Gifford Pinchot, in his rhetoric of conversation, had deemphasized the wilderness and recreational element, probably to get the support of economic groups for the forestry program. Like Alexander Hamilton, he needed to attract the "rich, the able, and the well-born" to the program. However, despite his rhetoric, he also supported Langille's suggestion for creation of wilderness areas in the national forest system. His successor, Henry S. Graves, stressed such recreational uses. Men like Arthur Ringland, Robert Marshall, and Aldo Leopold demanded wilderness areas, free from roads and development, and a number of them were established in the national forests during the 1920s. Robert Marshall persuaded the Bureau of Indian Affairs to establish recreational areas and helped to formalize regulations on their creation and use. There was, of course, pressure on both the national forests and the national parks from developers and recreationists over the extent and use of such areas. The Park Service and the Forest Service both attempted to hold a middle-of-the-road view between the extremes in each group.

Serious agitation for a national wilderness preservation system began in 1956. It was dramatized by a bill to let the Reclamation Service build a dam in Echo Canyon in the Dinosaur National Monument of Utah and Colorado. The bill met organized opposition from wilderness lovers and was defeated in Congress. The success of the opposition encouraged wilderness advocates to develop a legislative approach to the problem, analogous to the Multiple Use bill, making the Forest Service and National Park Service legally responsible for preserving wilderness areas under their jurisdiction. Howard Zahniser of the Wilderness Society, Senator Hubert Humphey of Minnesota, and Representative John P. Saylor of Pennsylvania played a large part in drafting such a bill in 1954. It provided for continuous preservation of existing wilderness areas, the inclusion of others by act of Congress, and that a council be set up to keep records and make recommendations. The bill had a long legislative history. The council was eliminated and some areas were excluded, but the bill was finally passed in 1964. [4]

Both acts were of value to the agencies involved and to the public. The Multiple Use Act formally put into operation what the Forest Service had practiced for years. It was no new innovation but rather a formal statement, updating the principles of previous laws and practice. However, it did speed up and sharpen planning and inventories. Each region and each ranger district drew up multiple-use atlases and plans for coordinated development of each area. It was well designed to aid in the shift from extensive to intensive management. The Wilderness Act, on the other hand, focused attention on the need to preserve some remaining scenic and primitive areas. It dramatized the issues and spurred on Congress and the public to work out plans balancing development, recreation, and wilderness preservation.

Neither of the bills was a panacea; both were subject to misinterpretation and both gave rise to unexpected problems. By statute and by McArdle's statements, multiple use was clearly defined. But the phrase became a rationale for proposed raids by mining and lumber interests on land dedicated to recreation. On the other hand, the Sierra Club carefully misinterpreted the act to be favorable to lumber interests, as opposed to wilderness recreation; it claimed that the training of foresters made them inadequate to make good judgments in the field.

The Wilderness Act also created new problems. Resource managers generally were dedicated to the wilderness concept but wondered about the effect of the designation on particular areas. The Huron Islands, for example, had a fragile environment, were accessible by powerboat, and were apt to attract hordes of people who might destroy the very values the bill was intended to protect. Wilderness hearings indicated a growing gap between local interest groups and recreational clubs, which used an area on a continuing basis, and occasional visitors, who were often associated with large and powerful national organizations. Accustomed as it was to working with local advisory groups, but under increased pressure from national groups, the Forest Service was caught in the middle. The term de facto wilderness became popular for areas not under the wilderness designation, and recreational organizations began to resort to litigation in an effort to achieve their ends, or to create a body of environmental law. Lumbering interests, on the other hand, became critical of the new regulations. C. M. Archbold, formerly a Forest Service officer in Alaska, wrote:

Our timber industry is being squeezed out of business by these young foresters who devote more time to planning how to care for the increasing recreational use (from now to the year 2000) than they do to caring for an industry that provides employment to many hands when in the woods. One old time industry man has aptly described it as "we are being Forested out of existence." [5]

With the end of the Eisenhower administration, a political climate more friendly to conservation came in. Both John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson were activists in the area of conservation. The Peace Corps, under Kennedy, carried forestry and park-making to other lands; the Job Corps aided in community projects. In Alaska the latter's work was similar to projects carried on in the interior under Chipperfield's direction during the CCC days. New parks and recreational areas were created, and a concerted effort was made to save the nation's shoreline for the future. As heads of the departments most concerned with conservation, Kennedy chose Orville Freeman as secretary of agriculture and Stewart Udall as secretary of the interior. Both were capable in their respective fields. Udall brought to the administration of his department much of the energy that had characterized Harold Ickes, but without Ickes's irrascibility.

McArdle continued as chief of the Forest Service until 1962, when he resigned. He will rank as one of the best chiefs—Arthur Greeley thought him the greatest. Secretary Freeman chose as his successor Edward P. Cliff, who had been assistant chief in charge of national forest resource management. Cliff, who had thirty-two years of service at the time he was appointed, was a native of Utah and had served in the Pacific Northwest, Colorado, and his home state before going to Washington. Some of his achievements included helping to write, pass, and implement the Multiple Use Act; aiding in Operation Outdoors, recreational planning for vastly increased use of national forests; and increasing the cut on the national forests from 4.5 to 8.5 billion feet. [6]

State of the Region,

1953

In the years 1953-1954, Alaska underwent striking changes. This brief period marked a shift from an extensive to an intensive type of management. In no region of the Forest Service did the change occur so dramatically.

In 1953 B. Frank Heintzleman resigned as regional forester to become governor of Alaska. Appointed by President Eisenhower, he was something of a compromise candidate among the several factions of Alaskan Republicans. His credentials were impeccable—he was conservative from the businessman's viewpoint, devoted to the interests of Alaska, and well known from his long Forest Service tenure in the territory. No appraisal of his work as governor has been published, but throughout his four-year term he remained a staunch friend of the Forest Service and aided the officers in their work. At about the same time, Charles Burdick, who had been Heintzleman's right-hand man, retired. W. A. Chipperfield became head of lands in the territorial government. A new team of men came into the Juneau Office in the persons of Arthur Greeley, John Emerson, and W. Howard Johnson. Assistant Chief E. W. Loveridge wrote:

They will appreciate that this office now knows about the tough tightening up, as well as forward looking job they have inherited—following the extremely poor administrations of more than 25 years of Heintzleman and Flory—without belittling Heintzleman's other accomplishments. The report cries out clearly that the region is on the verge of passing from a custodial stage to one of active management. [7]

A survey of the area, at the eve of this transition, may aid in pointing out its accomplishments. In southeastern Alaska, large-scale timber production was on the verge of getting under way. The Ketchikan Spruce Mills had enlarged its plant and production. The Ketchikan pulp sale had been completed, and the mill was under construction by fall of 1953. The Japanese plant at Sitka was in the planning stage, and there was talk of setting up a mill at Wrangell to ship hemlock cants to Japan. In addition, there were other sawmill and pulp interests looking over the Juneau area as a site of operation. Debate had begun over how many pulp mills could be established in southeastern Alaska. Ray Taylor claimed that the territory could not support five pulp mills, as Heintzleman had originally estimated.

Much attention was given the question of side effects from the pulp mill operations. Heintzleman had worked closely with research agencies and the Alaska Water Pollution Board to get satisfactory conditions of water purity. The problem was not so great in Alaskan waters—with twelve to twenty-four-foot tides—as it was in lakes or estuaries of the states. [8]

Raymond Taylor, meanwhile, also worked on research at Hollis. By 1953 he had located on a wanigan, built on a scow. He busied himself on a variety of projects, but silviculture and the effects of logging on salmon runs had the highest priority. Criticisms had been made that the large pulp sales, with clearcut logging, would injure the salmon runs. So Taylor and his crew set out to find the answers, working in cooperation with the University of Washington and the Bureau of Fisheries. They found that logging had no discernible effect on the spawning of salmon. Barriers formed by debris were easily bypassed. Since the streams came from the snowy heights, the water temperature was not raised materially by clearcutting, and viscosity remained low. The studies had been started in 1949; by 1953 Taylor had a body of information on which the Forest Service could act. Regrettably, the results of his studies were not widely circulated, and questions continued to be raised as to the damage done by clearcuts. [9]

Amenity values had not been neglected. Tentative cutting arrangements had been made to protect views along steamer lanes. The work of the CCC had been largely in recreational development, and the existing facilities were ample to satisfy existing needs. W. A. Chipperfield, as head of recreational planning, had developed several other areas, particularly around the cities—Totem Bight at Ketchikan, picnic areas at Wrangell and Petersburg, and Auke Village at Juneau. Studies had been made of lands to be reserved as scenic and primitive areas.

In the Chugach National Forest a number of small mills were in operation. These included a small mill at Seward, using timber from the national forest, and one at Whittier, an army base, using timber floated in from Prince William Sound. The Valley Lumber Company had a small operation on Afognak Island and shipped the lumber to Kodiak. This operation was unique in that the Forest Service did not get to Afognak more than once a year by boat; it accepted the mill records as scale. The sale, however, was carefully laid out and cruised.

In the Kenai, new highways from Anchorage to Seward and to Homer had opened up the peninsula. Though the roads were rough, people could use them for access to recreational areas. There were as yet few Forest Service facilities aside from a few picnic grounds. There were numerous five-acre plots taken up under the Small Tracts Act, and there was a townsite elimination at Moose Pass. There were also numerous mining claims that were actually used for summer homes. Chipperfield had laid out some good, well-designed summer home locations on Quartz Creek, with large lots and plenty of elbowroom, as well as concern for aesthetic values. Fire was the main problem. In 1947, 400,000 acres on the edge of the national forest in the Moose Range had burned; the fires were set by road construction crews. In the forest itself the main offender was the Alaska Railroad, which had nothing but disdain for fire protection measures. Coal-burning locomotives were the main problem.

In the Cordova area use centered around the numerous shanties or hunting camps in the Copper River flats, one of the greatest wildfowl nesting and feeding grounds in the nation. The camps were on national forest land, and many users had only squatters' rights. The military airport in Cordova had been put to civilian use, and a road was pushed out to the airport and beyond, built on the old roadbed of the C.R.&N.W. Railway. Travel was a major factor. Clyde Maycock, supervisor for the Prince William Sound Division, not only had to cover his own area but scale at the Whittier mill and make periodic trips to Afognak Island as well. The Chugach, an old but reliable wooden boat, was used for travel from Cordova to the outlying areas. It was the most isolated and least used of the districts. [10]

In a letter to Chief McArdle, written just before he resigned to become governor, Heintzleman mentioned some of the main problems of Alaska. Stands in the past had been highgraded, he said, and the pulp mills would aid in the increased utilization of hemlock. Cutting rules along steamer lanes had been established. A major need in administration was finance—more venture capital must be attracted into the area. Indian claims on the Tongass and mining claims in the Kenai remained problems. In a separate set of recommendations on the Cordova area, Heintzleman advised that scattered claims be consolidated into a few localities. [11]

Administration

There are many paradoxes in the history of the Forest Service as seen from a regional basis. In the Service as a whole, the period from 1953 to 1956 was one of trial. In Region 10, on the other hand, these were years of fulfillment in which the dreams of past foresters were realized and to which the problems of modern times had not yet come.

|

| A. W. Greeley, 1953-1956. (U.S. Forest Service) |

With Heintzleman's resignation, a new administrative team came to the Juneau Office. Arthur W. Greeley was appointed regional forester. Forty-one years of age at that time, he had been born in Washington, D.C., the son of former Chief W. B. Greeley. In physical appearance he resembled his father very much. He had served as ranger, timber sale assistant, assistant supervisor, and as forest supervisor in Montana, Idaho, and California. With him as assistant regional forester in charge of administrative management and engineering came John L. Emerson. He had been a supervisor on the St. Joe National Forest in Idaho and had served as an assistant to the Department of Agriculture representative on the Columbia Basin Commission. William H. Johnson, formerly supervisor of the Snoqualmie National Forest in Washington, became assistant regional forester for forest resources. Not one of these men had ever served in a regional office. In addition, a new fiscal agent came with them, Theodore Rollins.

The Greeley administration was marked by major administrative changes. The Alaska Region had been undermanned, having, in 1953, a smaller staff than that of the Snoqualmie National Forest. The men were hired to meet the shortage. The old divisional system of administration, set up years before by E. W. Loveridge, was changed in 1956 to a standard Forest Region organization. In the north, Malcolm E. Hardy, who had been a ranger at Petersburg, was made supervisor of the Chugach National Forest, with headquarters at Anchorage. He rented office space over the Malemute Saloon. Because of the light work load in the Chugach, he did a great deal of field as well as office work. Cordova and Seward were made ranger districts, and Afognak Island was attached to the Anchorage office for administrative purposes instead of to Cordova. Boat transportation was found to be inefficient, so charter planes were used to transport men. [12]

In the south, two supervisor divisions were established in the Tongass, the North Tongass and the South Tongass. The northern area was under Clare M. Armstrong at Juneau, the southern under C. M. Archbold at Ketchikan. Greeley found costs higher for plane travel than for boats; therefore, new boats were bought for the southern district to take care of pulp sales. The W A. Langille and W E. Weigle were purchased in 1954; they were thirty-eight-foot vessels, sleeping four. Another vessel, the Almeta was bought; the Maybeso, a forty-two-foot diesel boat, replaced the Ranger 6. The Ranger 9 was given an overhaul. [13]

Ray Taylor had helped to compile figures for the Timber Resource Review, but the estimates in Alaska had been made on the basis of incomplete data. A more complete timber inventory was needed, both to determine the number of pulp mills the region could use and for management purposes. In 1948 the Navy had completed an aerial survey of southeastern Alaska, and the photographs were used to develop a timber inventory. Road building had been delayed since Congress had not given the territory its full share of federal funds since 1931. Now Congress appropriated special funds to make up the deficit and road planning continued. [14]

Greeley described the region in 1956 as being in transition. Timber sales had gone up from 60 million feet in 1952 to 200 million in 1956, and would go up to 600 million in the near future. He spoke of the continuing forest inventory, carried on with the cooperation of the Ketchikan Pulp Company; the growing use of the Kenai for recreation; and the need for further recreational planning. [15] Greeley's stay in Alaska was brief, but his record was exceptional. He had a keen sense of history and the vision needed for planning far ahead. He was well liked in the region; his competence and integrity earned him the respect of the lumbermen. Greeley moved to Milwaukee to be regional forester of the North Central Region. Eventually he retired from the Forest Service and began a new career in the ministry.

|

| P.D. Hanson, 1956-1963. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Percy D. Hanson succeeded Greeley in 1956. He had been regional forester in Missoula. Under Hanson the process of moving from forest protection to management was continued. During his term of administration, new mills were established and timber production went up. Money was made available for buildings, and a large number of substandard units were razed. New facilities—ranger stations, warehouses, and the like—were built. Forest highways, planned under Greeley's administration, were finally built: the Portage Glacier Highway; the Hope Road relocation; the Sitka-Henry Cove Road; the Mitkof Highway out of Petersburg; and roads in Yakutat. Game-management planning was important, and there was a large development of hunting during Hanson's term of office, especially of elk on Afognak and moose in the Yakutat area. Cabins and trails were built for the convenience of hunters. Research progressed at the Hollis station. Recreational planning made great strides under Hanson's administration. The Visitor Information Center at Mendenhall Glacier was built. And with Alaskan statehood in 1959, state-federal cooperation came to be of great importance. Greeley and Hanson had played major roles as planners; Johnson carried their plans to fruition.

|

| W.H. Johnson, 1964-1971 (U.S. Forest Service) |

When Hanson retired in 1963, he was replaced by W. Howard Johnson. Johnson already had a long and interesting career in the Forest Service, serving under each chief from Bill Greeley to Edward Cliff. His experience had included recreational and wilderness management in the Olympic National Forest, CCC educational work, experience with timber sales in the Columbia, Olympic, and Snoqualmie national forests, further work as ranger and supervisor in the state of Washington, and service in the Washington Office. Like Langille, he was so varied a man as to defy easy analysis. A practical forester of the George Drake type, a wilderness lover, concerned with civic affairs, and with a strong sense of justice, he was a worthy successor to the previous regional foresters.

Johnson's term was one of both achievement and controversy. It marked the fruition of the planning and devoted work of men of the past. New sales were started, and Heintzleman's dream of a pulp-producing empire became a reality. Forest research by this time had secured the data that justified cutting on a continuous basis and the replacement of old decadent forests by new ones. Wilderness planning and recreational development came of age during his term, and the interpretive program of the Forest Service flourished with new and imaginative ideas.

There were problems, however; some falling off in cooperation with the state conservation agencies occurred because of the increased incursion of politics into state management. State land selection rights provided that 400,000 acres from the national forests would go to the state. A new Admiralty Island controversy arose, and a suit by the Sierra Club threatened the latest pulp sale. Johnson's administration resembled Weigle's, being marked by both accomplishments and controversy.

A host of new Forest Service officers came to Alaska during this period and many of the old-timers retired. It brought about greater efficiency in the work of the Service, but some of the old-timers noted the changes with regret. In the past, wrote C. M. Archbold, one of the old-timers now working for industry, there had been a small group of career employees with many years of experience in Alaska. Now there was a greatly expanded force of less experienced men. The changeover, he felt, was too rapid; the men were spending more time in group training sessions than in serving logging operations. In the judgment of some, this made for less intimate relations between the Forest Service and industry. [16]

|

| Aerial view of experimental block-cutting near the Hollis camp of the Ketchikan Pulp and Paper Company, 1958. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Timber Sales

Timber sales flourished during this period, going from 219 million board feet in 1955 to 405 million in 1965. There was a diversity of activities and new cutting and milling techniques. There were the large mills, such as the Ketchikan Pulp Company mill, and other new mills—the mill at Wrangell—and smaller, established operations like the Ketchikan Spruce Mills.

Harvesting followed the clearcut pattern. The first camp of the Ketchikan Pulp Company was established at Hollis, and Ray Taylor was able to use its logging as the basis for silvicultural experiments. Timber cuttings were large, often covering entire watersheds, as Taylor had found that the light seeds of the hemlock and spruce provided 95 percent natural regeneration within a period of three to five years. Some of the cutting was done by employees of the company, but gypo operations were frequent. When completed, the timber inventory indicated that there was more timber than had at first been estimated. The initial sale to Ketchikan Pulp had been on a cubic-foot basis. This proved unsatisfactory and was changed to the board-foot basis.

|

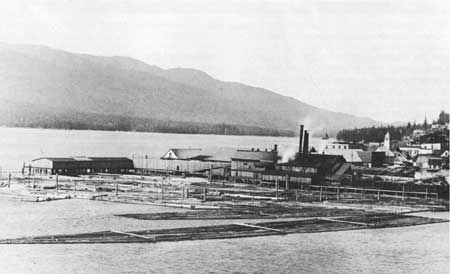

| Plant of the Ketchikan Spruce Mills, Kectchikan, Alaska. (Tongass Historical Society) |

The Ketchikan Spruce Mills had some difficulties with the Forest Service. This was the old Ketchikan Power Company that had reincorporated in 1923 as the Ketchikan Spruce Mills. It had flourished during World War II, cutting spruce and hemlock for defense purposes. Its problems were complex and not all related to the Forest Service. The difficulties included high taxes, high stumpage, high shipping costs, and lessened profits. Basic protests against the Forest Service included poor scaling because of poor measurements and failure to allow for defects. This complaint was probably justified. There was some fear that the Wrangell sale might take timber that would properly lie within the Ketchikan Spruce Mills area. The major protests, however, came from the West Tuxekan sale. It involved alleged overestimation of grades and volume of logs, poor road location, faulty engineering, and "too rigid standards" set for road building by the Forest Service. Strong language was bandied about by Milton Daly, manager of the Ketchikan Spruce Mills, and P. D. Hanson, C. M. Archbold, and C. T. Brown of the Forest Service. Eventually the sale was cancelled. There were similar protests against scaling and grading at the Whittier mill, against Clyde Maycock's scale. Once again, strong language was used. The majority of these complaints disappeared, however, when Ray Taylor prepared volume tables for scaling logs in long lengths and Howard Johnson established a school for scalers. [17]

Elsewhere, a new large sale was negotiated at Wrangell. During World War II there was a call for more lumber by the Army Corps of Engineers, and a firm called the Wagner Lumber Company was established. The engineers were persuaded to put money in to the Wrangell sawmill, now in need of repairs and new machinery. The money was provided with the agreement that the mill would sell lumber to the corps at a fixed price. The mill, however, ran for only a short time; Wagner left the country and the Army Corps of Engineers reacquired the property through default. It sold the mill to an American Japanese named C. T. Takahashi. He operated it for a time and eventually sold it to the Japanese group planning to build a mill in Sitka. The Japanese formed a corporation, the Wrangell Lumber Company, as a subsidiary of the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company.

|

| Sitka, 1958. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Meanwhile, another mill was built at Wrangell. The Forest Service offered for bid 3 billion feet of timber in the area with a provision that a 100-ton pulp mill be built in connection with the sawmill within three years. The sale was made to the Pacific Northern Timber Company. This company had been formed by a son of Oregon lumberman C. D. Johnson. Later, an Oregon attorney, C. Girard Davidson (formerly an assistant secretary of the interior in the Truman administration), reorganized the company, set up a mill, and got the operation going. In 1968, however, it was sold to the Wrangell Lumber Company. The pulp mill was never built because of economic reasons, and the sale reverted from a fifty-year tenure involving 3 billion board feet to a fifteen-year sale of 790 million feet. [18]

The Japanese interests, formed as the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company, began preparing their Sitka site. It was the first major foreign investment made by Japan after World War II. In 1957 the company started work on the camp site at Silver Bay. The land was acquired under the Tongass Timber Act of 1947, which contained provisions for such acquisitions. Blue Lake was planned as a source of process water, and here the city of Sitka entered into partnership with the company. The city helped construct the dam for hydroelectric power as well as for storage. The road was financed by the Alaska Road Commission, the city of Sitka, and the Forest Service. Construction of the plant was completed early in 1959. A pleasing aspect of the situation was the good feeling evident between the Americans and the Japanese, all the more amazing since the war had not been over long.

Another aspect of the Japanese development was concern about water pollution. It had received priority before, but the sensitivity of the Forest Service and others was more acute because of the foreign ownership. Agencies of the state and federal governments studied the effects of the plant. The University of Washington Oceanographic Laboratory made studies, gathering data on both high and low water conditions during the year. These studies were the basis of subsequent approval of the Alaska Water Pollution Board. They were the most comprehensive studies of receiving waters made up to that time. [19]

In August 1955 the Georgia-Pacific Corporation made a successful bid for 7.5 billion feet for pulp manufacture, most of the timber being on Admiralty Island. The sale, however, was not completed. The company failed to comply with regard to the full obligation, asked for delays, and finally dropped the project, forfeiting a $100,000 deposit made in 1961. There were a number of factors involved, including its decision to build another mill at Toledo, Oregon. [20]

Small mills continued operations during this time. One-eighth of the timber cut on the Ketchikan Pulp Company sale was cedar. There was no local market for cedar, so a small mill was set up at Ketchikan to manufacture lumber for export to the states. The small mill at Yakutat continued its operations, based on railroad logging. In the birch timber district near Anchorage, where John Ballaine had once entertained dreams, a small mill was finally established.

In September 1965 the Forest Service advertised 8.75 billion feet of timber for sale, with provisions that a pulp mill be constructed by July 1971. For the first time, a number of large paper producers were interested in the area, including the Weyerhaeuser Company, St. Regis Paper Company, MacMillan Bloedel, the Canadian giant, and other firms. St. Regis, which bid $5.60 per thousand with plans to cut 175 million feet per year, was the winner. St. Regis spent 1966 examining the area and layout of tentative road locations. It examined various plant sites and selected one near Sitka.

The St. Regis sale fell through, however, for a variety of reasons. These included the costs of labor, transportation, and building the plant. The company forfeited its bond and gave up the sale. In 1968 the sale was offered to the second bidder, U.S. Plywood-Champion Papers, Inc., and was accepted on the same terms. This sale was noteworthy for the fact that the company hired an advisory commission of eminent scientists to give it advice on avoiding damage to the environment. It was the first time industry had appointed such a committee to advise it on ecological matters. The company picked out a plant site at Katlian Bay, near Sitka, but the site was rejected on ecological grounds. Then construction of a plant at Echo Cove, north of Juneau, was delayed by the Sierra Club suit, a subject that will be considered later. [21]

Logging techniques in Alaska had progressed from primitive handlogging to sophisticated tractor and cable methods. In the late 1960s experimentation was begun on balloon logging, using techniques developed in British Columbia and in Oregon by Bohemia Lumber Company. During the summer of 1968, Regional Forester Johnson spent eight days by boat and plane examining balloon logging shows in the South Tongass. In November 1970 the fieldwork was completed, and it was determined that balloon logging was a feasible technique for Alaska. It allows the logger to reach back 4,000 feet to previously inaccessible stands on high slopes. In addition to making more timber available, it reduces the impact of logging on the soil. Study was also made during this period of converting plant residues to chips for sale to pulp plants. Another technique studied was moving chips from the field to the mill or onto barges using pipelines and water pressure. [22]

|

| Fish wheel in the Yukon River at an Indian village east of Eagle, Alaska. Note the timber on the far shore, which is near the Canadian boundary. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Research and

Cooperation

Raymond Taylor continued to push studies at the Alaska Forest Research Center in Juneau. He established field headquarters on a wanigan at Hollis, logging camp of the Ketchikan Pulp Company. After two years he was able to secure transportation in the Maybeso, a forty-two-foot boat with galley and shower, sleeping four and making a top speed of nine knots. It was ideal for his purposes. Harold E. Andersen, formerly of the Prince William Sound Division, and Richard M. Goodman, formerly from the Northeastern Forest Experiment Station, were hired as assistants, with Elizabeth A. Corey as secretary.

Taylor's early work related to pulp mill operations. He developed accurate long-log volume tables for scaling at the mill. Since the first cuttings of the Ketchikan Pulp Company were at Hollis, he was able to have silvicultural and mensuration studies conducted on the spot. He carried on yearly studies of the effect of logging on the salmon runs. In some of this work he had the cooperation of the Fisheries Research Institute of Seattle, the Geological Survey, and the Fish and Wildlife Service. He worked with the Forest Survey in the 1950s, studying old plats and aiding in interpretation of the photographs on which the Forest Service based its estimates. He carried on research in entomology and pathology. During the years 1948-1955, there was damage done by the blackheaded budworm and the hemlock sawfly, causing a loss of 268 million feet. He also studied the occurrence of spruce bark beetle on Kosciusko Island. [23]

In 1957 the studies were extended into the interior. Taylor traveled to Anchorage to meet Roger Robinson, the Alaskan head of the Bureau of Land Management. Robinson had gone to Alaska from the Forest Service when the BLM absorbed the General Land Office and the Alaska Fire Control Service. Robinson faced a discouraging task. Although, on Heintzleman's advice, the Department of the Interior had set up a fire control office in Alaska in 1939, the appropriations were pitifully small. From 1939 to 1942, CCC labor had aided in combating fire, but the war put an end to the CCC. In 1947 Congress failed completely to appropriate funds for fire control on the BLM lands in Alaska. That year was marked by a disastrous 400,000-acre fire on the Kenai Moose Range that swept up to the border of the Chugach National Forest. In 1957 fires destroyed timber worth $15 million and many acres of wildlife and wildfowl habitat.

Robinson was curious about the effects of fire on the ecology because of its destruction of trees, reindeer moss, swamp vegetation, and game habitat. He traveled with Taylor around Alaska, and both became interested in the ways in which fire affected the ecological succession of plants and the subsequent effects on animal life. Robinson felt that knowledge of this kind would be a good selling point to people in his campaign for fire prevention. He felt that a study conducted from outside the Bureau of Land Management would be particularly valuable. Taylor suggested Harold Lutz of Yale as the best man. Lutz had previously conducted studies of plant succession in New Jersey, and he had worked in Alaska. Funds were raised and Lutz took summer leave from Yale to make a series of studies. He traveled about the country in a truck, sometimes with Taylor and sometimes alone. It was an enjoyable time for both men. Lutz was the best of camp companions and was fascinated with the work, so much so that, even though they were working in bear country, he would frequently become preoccupied, lean the rifle against a tree, and only hours later remember to go back and recover it. Taylor had ample opportunity to gratify his keen interest in nature and in human nature. [24]

Since the 1920s, there had been periodic shipments of seed from Alaska to Iceland. Conditions of climate and soil were such that the Icelandic government felt that plantings of birch, spruce, and hemlock from Alaska might be used in afforestation projects. After World War II, the forestry branch of the Food and Agriculture Organization became interested in the project. Taylor was invited to go to Iceland under FAO sponsorship; he made the trip, examined plantations, and later gave a paper in Rome on the project.

In 1959 Taylor retired from the research center management. He was another of those men who contributed much to the course of Alaskan forestry in the area of research. An able, humorous, talented, and occasionally sardonic realist, he helped bridge the gap between the old and new eras in Alaska.

|

| Mixed farm and forest land near Fairbanks, 1958. (U.S. Forest Service) |

After an interim appointment, Taylor was succeeded by Richard M. Hurd, who served from 1961 to 1970. The center became the Northern Forest Experiment Station between 1961 and 1967. Hurd's major achievement was establishing a branch of the experiment station for the study of the interior forests. The major decision involved was whether to establish it on the administrative site of the BLM or on the campus of the University of Alaska. He finally decided on the University of Alaska in order that researchers might be a part of the academic community. In the southeast there was continued study of regeneration of clearcuts, soil erosion on logged areas, and the like.

Under Hurd's management there was increasing research on fisheries. A fisheries biologist was added to the staff of the station in cooperation with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and the habitat of fish streams was improved. One of Hanson's achievements as regional forester was the development of a gravel-cleaning machine (riffle sifter), a device that travels up the streambed to clear sediment from the gravel, thus improving the fish spawning grounds. Road locations were carefully planned to minimize the washing of sediment into salmon spawning streams. [25]

Cooperation among government agencies was an old story in Alaska, and it continued during this period. It involved Forest Service cooperation with the BLM in fire control on the public domain, particularly in the Kenai. It also involved cooperative work with the Bureau of Public Roads and Fish and Wildlife Service. The National Park Service and the Forest Service continued their cooperation, particularly in regard to Glacier Bay National Monument, and the planning of recreational or wilderness areas. New dimensions of cooperation were entered into, however, when Alaska became a state.

Statehood involved both conflict and cooperation. Alaska state government got into the business of forest management and recreational use. The story of the state government's forest and recreational policy from 1959 to the present would make a book in itself. However, the part played by the Forest Service in aiding the development of this policy should be mentioned.

The Alaska State Constitution provided for the use and maintenance of renewable natural resources "on the sustained yield principle, subject to preference among beneficial uses." It involved the Forest Service principles, therefore, of sustained yield and multiple use. A Department of Natural Resources was set up in 1959. Under it was established a Division of Lands, which in turn supervised the state forester and the state parks and recreation officer. [26]

The state had the right to select 102.5 million acres under the General Statehood Act, 1 million acres under the Mental Health Grant, 400,000 acres from national forests for community expansion and recreational use, 400,000 acres from the public domain for these purposes, 100,000 acres for the benefit of the University of Alaska, and about 108,000 acres for school land from surveyed areas. This area was to be selected within twenty-five years, which meant an area about the size of Rhode Island every two months. [27]

Cooperation with the Forest Service came under three headings. First was the technical advice, which involved a wide variety of activities. Clarke-McNary aid and fire control were given to Alaska for fire protection as early as 1961. For its fire prevention and suppression program, the state relied heavily on an agreement with the BLM, which had a protective organization, paying it an assessment per acre for suppression, detection, and presuppression costs. The Forest Service set up the Forestry Sciences Laboratory at the University of Alaska to study forest conditions in the interior on a continuing basis. It aided in making the state's forest inventory in the Susitna Valley, the lower Tanana Valley, the Haines area, and on islands near Kodiak. Forest Service personnel conducted classes in log grading in the Susitna Valley. The Bonanza Creek Experimental Forest of 8,000 acres was set up under Forest Service direction near Fairbanks. [28] The state also obtained aid from the Forest Products Laboratory for hardwood grading and mill efficiency at Wasilla, for use of small logs for veneer, and the seasoning of paper birch to avoid checking.

Recognizing the need for coordinated planning for recreation, State Forester Earl Plourde took the initiative in organizing the Alaska Outdoor Recreation Council. Its membership consisted of the state departments dealing with natural resources, including the Departments of Natural Resources, Economic Development and Planning, and Fish and Game, the University of Alaska, and representatives of the various boroughs; along with federal agencies involved: the Forest Service; National Park Service; Bureau of Indian Affairs; Bureau of Reclamation; Bureau of Land Management; and Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. Beginning in 1964 the council had periodic meetings to discuss matters of common interest: the Wilderness Act; efforts of the BLM and the Forest Service to classify their lands; and the development of a state park system. The Alaska Outdoor Recreation Council was essentially a planning and a coordinating group for all federal and state agencies concerned with outdoor recreation, and it acted to lessen friction among the participating bodies. [29] Its reports are of great value for sketching progress toward a coordinated recreational development of the area.

Other aspects of state and governmental agency relations have been less harmonious. To some extent this had included the drive for development. Discovery of oil in the Kenai National Moose Range led to suggestions by Senator Ernest Gruening that the moose range and the Chugach National Forest be returned to the public domain. The more recent claim of the state to 400,000 acres of national forest land has led to difficulties.

State selection lands were for the purpose of community development and recreation. However, the state and the Forest Service did not see eye to eye on justification of the areas, and the Forest Service made its own recommendations and analyses. The procedure followed for transfer of land to the state was by recommendation of areas, survey by the BLM, and transfer of title to the state for use or disposal. The state continued its selection of lands largely on the public domain until 1968, when Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall put a freeze on further selections pending settlement of Native claims.

Native claims, a burning issue on the national forests since the 1930s, came closer to settlement. In January 1968 Governor Walter Hickel established a Native Land Claim Task Force with representatives of all ethnic subgroups. They met with members of the Forest Service and BLM and developed a legislative proposal to meet native needs. About the same time, a Federal Field Committee for Development Planning for Alaska studied the matter, and in Alaska Natives and the Lands produced a comprehensive socio-economic report. Bills on Native claims were introduced in Congress in 1969 and again in 1970. Senate Bill 1830 was passed in midsummer 1970; it provided for a payment of $500 million and 10.5 million acres of land to settle Native Claims. Action was not taken in the House. Applied to the national forests, the formula was one township to each Native village. There were nine such villages in the Tongass and one in the Chugach, though one was too small to qualify. Ironically, in 1968 the Court of Claims had made a settlement of the Haida-Tlingit claim on the Tongass; it created a curious legal problem as to whether the court judgment or the proposed congressional legislation were valid. [30]

Totem Poles, Amenities,

Recreation, and Wilderness

Interest in preserving Indian antiquities in the Alaska region has had a long history. As early as 1888, Ensign Albert Parker Niblack of the U.S. Navy had recommended preservation of the Indian antiquities. Governor John Green Brady had been interested in setting up a park for their preservation, and W. A. Langille had succeeded under the Antiquities Act of 1906 in getting preservation of one village, Old Kasaan, as a national monument and in giving the totem pole park in Sitka protection under the same act. During the CCC days, Heintzleman, Flory, Linn Forrest, Viola Garfield, A. W. Blackerby, and others had succeeded in restoring and creating replicas of a larger number of poles. [31]

Totem pole work had been a function of the CCC, largely using Native labor. The CCC was phased out during the war, however, and activity in regard to the totems ceased. The Park Service had no boat to police Old Kasaan or to carry on maintenance, so it was phased out as a national monument in 1954. Regional Forester Greeley felt that some protection should be given to the site, so in 1964 he proclaimed it a historic site, under Forest Service protection. In other areas, however, existing poles were left to the elements. The poles were private property with ownership resting in the individual or the village; the Forest Service had no jurisdiction over them nor funds to take on the task of totem pole preservation or restoration. [32]

In 1946 an art historian and writer, Katherine Kuh, made a confidential report on the totems for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. The report was both critical and ill-informed. Kuh was highly critical of the CCC for carving new poles; because of the "native conviction that copies can replace originals," she wrote, "much of the greatest Indian art of Southeastern Alaska has been totally destroyed or lost." She reported inaccurately that the Forest Service had no archaeologist or trained museum technicians to advise and direct the preparation of totems for rehabilitation and restoration. The Forest Service, she declared, had been guilty of scandalous neglect at Mud Bight, where poles had been left to the mercy of the elements. Meanwhile, the CCC work had not been continued, and at Hoonah a fire had destroyed a house and its contents. She recommended that the National Park Service control the totem parks and that archaeological aid be used in restoration work. [33]

During a twenty-year period, little new work was done. Carl W. Heinmiller of the Alaska Indian Arts Council kept up an interest in totem restoration work. Linn Forrest continued his interest in Indian legends. There were some attempts to purchase poles from individuals in the states, but the Forest Service itself had no authority to deal with such requests and referred the questions to the Alaska Native Sisterhood (ANS) and the Alaska Native Brotherhood (ANB). The Coast Guard, denied permission to buy a pole, stole one for its establishment. In 1960 the poles located in villages were classified in the National Forest Recreation Survey as historical or archaeological sites. [34]

In 1966, Katherine Kuh wrote an article in the Saturday Review, a national magazine of literature and the arts. Like her 1946 report, it was sensational and inaccurate. She dealt with the neglect and loss of Native art in Alaska. Destruction, she said, came from the climate, from fire, and from governmental neglect. All governmental agencies were attacked. She described the abandonment of Old Kasaan as a national monument and reported that no one in the National Park Service in Juneau could explain, or indeed, had ever heard of Old Kasaan. As for the Forest Service:

Some twenty-odd years ago, the Forest Service, without benefit of archeological or anthropological advice, instituted a program in which the local Civilian Conservation Corps undertook to rehabilitate—but, alas, more often to dismember or copy—old poles in Ketchikan, Wrangell, Sitka, Kasaan, Klawock and Hydaburg. [35]

No official reply was made to the Saturday Review, though Regional Forester Johnson explained the situation in a letter to the chief forester. [36]

Despite its inaccuracies, the article brought action. The wife of Secretary of the Interior Udall read the article and called it to her husband's attention. George Hall of the National Park Service was brought into the picture. In Alaska the state legislature had passed an act dealing with artifacts and archaeological sites, essentially extending the same protection to such sites on state lands that the Antiquities Act of 1906 extended to antiquities located on federal land. [37] The result of all this was a Conference of Southeast Alaska Artifacts and Monuments held in Juneau on July 13-14, 1967. The meeting included representatives from the Universities of Alaska, California, and British Columbia, the National Park Service, the Alaska State Museum, the Alaska Native Brotherhood, Alaska Indian Arts, and the U.S. Forest Service. C. T. Brown of the regional forester's staff and Jack C. Culbreath of Information & Education represented the Forest Service. Their councils were somewhat divided. As Carl Heinmiller wrote to Brown, the arts and craft group wanted restoration as a minimum, the Bureau of Indian Affairs was not for anything unless it could do it, and the archaeologists were not for restoration on the site or for reproduction. The Forest Service explained the terms of the Antiquities Act, giving the Department of Agriculture responsibility for protection of the poles and site. Another factor was that the poles were considered by the Forest Service to be private property, not to be removed or reconstructed without consent of the owners. [38]

A series of meetings was held, with Jane Wallen of the Alaska State Museum and Erna Gunther of the University of Alaska as moving spirits. An inventory of the remaining poles was taken by the Forest Service and the Alaska State Museum, and in 1970 a project was funded for removal of the better poles from isolated villages or sites and for their preservation. [39]

Amenity Values—Steamship

Lanes

A major problem, growing more difficult as time progressed, was that of preserving scenic or aesthetic values and reconciling them with economic use. Since the controversy is a continuing one, some background on Forest Service policy may be useful.

Forest Service regulation of cutting near roads for aesthetic purposes began in 1906 when George Cecil adopted such practices on Forest Service roads near Yellowstone Park. Under Henry S. Graves and William Greeley formal regulations were adopted, applicable to all regions, to preserve the recreational and scenic values along roads. These included leaving a scenic strip of timber along the roads to keep unsightly structures or disturbances such as borrow pits from the sight of travelers, and having permittees build their houses or garages back from the road behind a tree screen. On the forest highways under their jurisdiction, the Forest Service enforced such regulations. [40]

The steamer lanes created a new problem. Clearcutting is silviculturally the best method of harvesting timber on the Tongass. But the relief of the Alexander Archipelago is rugged, and cutting areas are visible for long distances. The cuttings met with adverse comment from travelers. (At the same time, clearcuts in the states also met with increasingly adverse criticism because of increased recreational travel off the beaten path, and logging shows at higher elevations were often visible from the lowlands.) [41] Heintzleman set up cutting regulations for the steamer lanes; these called for no clearcuts along lanes 1,000 yards or less wide and for special treatment for those lanes more than 1,000 yards but less than two and one-half miles wide. Heintzleman's recommendations were refined by Greeley in 1954 and by Hanson in 1958. [42]

The policy, however, did not do all that it was intended. As tourism increased, clearcutting areas met increased criticism from the travelers. Part of it came from mistaking large blowdowns, such as the one in 1968, for destructive logging. Part stemmed from ignorance; people who know nothing of logging practices tend to equate clearcutting with strip-mining. There were also many sensational and usually inaccurate articles and letters to the editor in such diverse publications as Field and Stream, Sierra Club Bulletin, and American Forests. [43]

A major factor here, as in other national forests, was the failure of the Forest Service to adopt an interpretive program appropriate to the changing American society—urbanized, with leisure time for recreation, and conditioned to the "hard sell." In an earlier age the Forest Service had displayed great skill in working with local and regional advisory groups, both recreational and economic. Gifford Pinchot, for example, was an able public relations man; the CCC work of the 1930s had a good press; and publicists like Bernard De Voto, Richard Neuberger, and Arthur Carhart kept the accomplishments of the Service in the public eye during the early 1950s. As time went on, however, the Forest Service failed to publicize its aims or best accomplishments, such as the silvicultural benefits of clearcutting or Taylor's studies of logging and fish culture in Alaska. Not until 1961 did the agency adopt an interpretive service similar to that of the National Park Service. The delay was unfortunate.

By 1968 the Forest Service in Alaska took corrective action. Under D. Robert Hakala, a Forest Service naturalist who had had experience with the National Park Service, plans were made to introduce an interpretive program on the Alaskan ferries similar to that used by the National Park Service in its aquatic parks. The program was worked out in cooperation with the state of Alaska and the Alaska Ferry System. Forest Service information desks were set up in the forward lounges of the vessels; seasonal employees, fresh from training sessions, give descriptive lectures and slide shows, interpreting the changing scenes to the visitors. The program has been highly successful and should do much to interpret the forest to the visitor. [44]

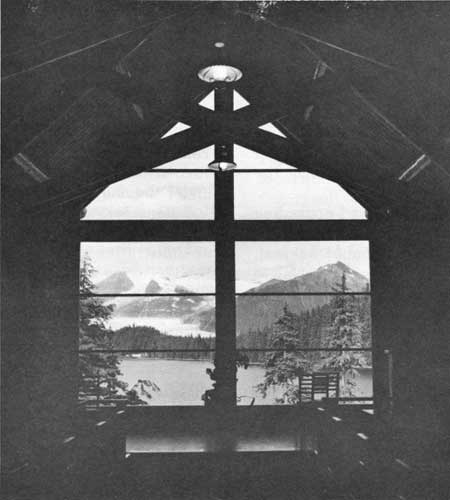

There were other ventures in interpretation and visitor amenities. Under Percy Hanson, a well-designed visitor center was established at Mendenhall Glacier. Nature trails were built and interpretive talks given. Assistant Regional Forester Johnson, on his first trip to the Chugach, was impressed by the possibilities of a similar program at Portage Glacier. A road was punched in to the area and an interpretive center was later set up. Both sites were highly popular with the public. [45]

|

| Mendenhall Glacier near Juneau has been a popular tourist stop for decades. In 1958 a Forest Service engineering crew surveyed the right of way for a new road to an overlook point. (U.S. Forest Service) |

|

| Auke Lake and Mendenhall Glacier through the picture window behind the altar of the Chapel by the Lake, 1958. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Since 1957 a large amount of money has been spent in planning and building recreational facilities. Two major study programs—Operation Outdoors, designed to restore facilities that had deteriorated from age or overuse, and the National Forest Recreational Fund, based on studies and estimates made to the year 2000—were both carried on in Alaska. In the Kenai new campgrounds were built and old ones restored. Some facilities damaged by the 1964 earthquake were restored. Under Forest Service permit, lodges were built in the forest and some ski tows were constructed.

On the Tongass National Forest, campgrounds were built near the cities; the campground near Mendenhall Glacier was especially outstanding. Because of the inclement weather in the area, however, cabins were built on inland lakes and near harbors. There was some experimentation with three-sided Adirondack shelters, but there were not suitable and were replaced by four-sided cabins or A-frame shelters. With increased demand, reservations for the use of the cabins was required and a small fee charged. Access to the cabins was by boat or plane; trails were still relatively few.

Road building involved a number of factors, some unique to Alaska. Forest Service standards in forest highways were maintained. The Forest Service was aware, however, of the increased popularity of motor camping and the desire of campers to be able to go from place to place for sight-seeing, sports, and recreation. The lack of roads near the communities made opportunities limited. During Hanson's administration studies were made regarding the building of a series of integrated forest roads in southeastern Alaska to connect with state highways and ferry routes. They would involve roads used initially for timber access but would later link communities and be part of the highway system. Over the years, Hanson, C. T. Brown, G. W. Van Gilst, R. O. Rehfeld, and Vince Olson worked over the plans.

The plan as finally developed involved upgrading timber access roads to meet higher standards than were customary. It involved planned timber harvest, roadside protection, connection with towns and Native villages, and docks from which ferries could carry tourists from island to island. It also involved the construction of trails to recreational areas and the planning of campgrounds. The road system would extend north from Ketchikan along the west side of Prince of Wales Island, through Kupreanof Island, along the west coast of Admiralty Island, and on the west side of the Lynn Canal to Haines. [46]

Recreation is related to game management, which came to be of increased importance in the region. Before statehood the Forest Service cooperated with the Alaska Game Commission, the Biological Survey, and its successor, the Fish and Wildlife Service. With statehood the Forest Service became increasingly involved with state officials in game management and its relation to timber harvest. Agreements were made for joint cooperation of the Forest Service, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the state of Alaska in the management of the great wildfowl breeding grounds on the Copper River Flats and the delta of the Stikine River. The elk herd of Afognak, planted there in 1929, came to be of increasing interest to sportsmen. The Forest Service built trails and cabins in the area for the convenience of hunters. Moose were transplanted into the Copper River country, and the herd flourished. Here, transportation was largely by air, using the commercial airfield. In the Yakutat area, P. D. Hanson became intensely interested in the management of the moose herd. He conducted a study, using planes and helicopters, and found that the moose harvest should be increased because of overgrazing. The Forest Service built a number of small landing strips for the convenience of charter planes carrying hunters, as well as some cabins and trails. [47]

During Heintzleman's administration there was considerable discussion over natural areas and wilderness areas. With the administrations of Greeley, Hanson, and Johnson came concern for multiple-use management. Before going out of office, Heintzleman received suggestions from Ray Taylor and Charles Forward on potential natural areas, including central Prince of Wales Island, Whipple Creek, Limestone Inlet, Hilda Creek, and several areas on the public domain. Limestone Inlet, Old Tom Creek, and Rock Creek were established in 1951, under regulation U-4, through Taylor's recommendation. By 1957 a series of other areas had been created or were under consideration, including Excursion Islet, Esther Island, Bell Island, Manzanita Bay, Telegraph Creek, Lake Shelokom, Taku River, and the Juneau Ice Field. Between 1964 and 1970 a large number of these areas were reserved under the multiple-use district plans. [48]

Consideration also grew for reservation of wilderness areas. As has already been noted, Heintzleman's administration gave protection to the Tracy Arm and Fords Terror area. There was also consideration of the College Fiord area on the Chugach. During the administration of Greeley, there was continued correspondence on these as well as the Walker Cove-Rudyerd Bay area near Ketchikan. [49]

With the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, there were renewed efforts to set up wilderness study areas. [50] Johnson had discussions with interested local groups, including the Alaska Conservation Society, the Sierra Club, and the Wilderness Society. A wilderness workshop was held at Juneau in February 1969, in which the objectives of the Forest Service were explained and the areas discussed. Plans were made to prepare complete studies of the major wilderness areas before the end of June 1970. Johnson also made a speech to the Sierra Club in San Francisco on March 14, 1969, stating the objectives of the Forest Service in Alaska. There he announced that the chief had approved consideration of the Nellie Juan area—700,000 acres on the west side of the Kenai Peninsula. The proposal was received by the Sierra Club—by this time somewhat at odds with the Forest Service—with a notable lack of enthusiasm. Other area proposals included the Tracy Arm-Fords Terror area south of Juneau, the Walker Cove-Chickamin River area, and Russell Fiord, near Yakutat. Another area was under consideration at the end of the year. Vince Olson, supervisor of the North Tongass, and R. O. Rehfeld, of the Ketchikan office, played a large part in preparing the plans. The areas under consideration were far larger in extent than the areas considered at an earlier date by Heintzleman. They would total well over 2 million acres in areas presenting a unique relationship of water and land beauty. They would present special problems in management. Completion of the work would depend on thorough field examinations of the areas concerned, including examination by the Geological Survey as well as a search for minerals by the Bureau of Mines. [51]

The chief also had under consideration a plan to create a national recreation area in the Kenai Peninsula. The area considered has little value for timber harvest, but is preeminently suited for recreation. Management proposals for the area were drawn up. Another consideration was that if Congress passed a Scenic Highway Act, the Sterling and Seward-Anchorage highways would come under immediate study; in the national forest portions of these highways, there would be special management to preserve aesthetic qualities. [52]

Other matters have been more controversial. Conservationists in Sitka proposed that the Chichagof-Yakobi islands area be made a wilderness. Records show that a great deal of handlogging and mining activity had taken place there around the turn of the century, but, with the passage of time, the area had been deserted. The idea was supported by articles in National Parks Magazine and the Sierra Club Bulletin. The chief of the Forest Service, however, rejected the plea on the grounds that the entire proposed wilderness was included in the sale area of the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company and that there were other conflicting uses. Also, near Petersburg, a local group protested plans of the Forest Service to build a timber access road up Petersburg Creek to connect Petersburg with Portage Bay on Kupreanof Island. [53]

Admiralty Island has been the source of almost perpetual controversy. The controversy begun by John Holzworth flared up during the 1950s; in 1964 the Forest Service developed a thorough and far-reaching plan for the island. It involved protection of the 800 to 1,000 brown bear through sanctuaries at Pack Creek and Thayer Mountain, making population studies, and controlling the harvest. It also involved the protection of Sitka deer. Timber harvest was planned on the basis of a past record of seventy to eighty years of cutting 0.5 percent of commercial timberland per year and modifying previously studied clearcut areas to conform with recreational use; the continued building of cabins was planned for the lake area. [54]

Despite these plans, attacks on Forest Service policy on Admiralty were revived. Ralph Young, a Petersburg guide, wrote a sensational article for Field and Stream titled "Last Chance for Admiralty." Another article dealing with the area had as its theme the "rape" of the land, in particular mistreatment of land around Whitewater Bay. The articles were sensational in tone and were not hampered by rigid adherence to the facts. They stirred up national interest. The Forest Service answered hundreds of letters on the subject and printed many brochures, but the stories were, and still are, widely believed. [55]

People writing conservation history in the future will find much to write about Sierra Club activity during the 1960s and 1970s. With a growing militancy in the leadership of the club, it fought to make itself the dominant environmental organization in the country. There was an internal struggle for leadership, and the more militant wing split off into a separate organization called Friends of the Earth. One aspect of their new approach has been litigation. A series of challenges to the multiple-use philosophy in national forests has occurred in separate cases from California to Michigan. These have presented new problems to the Forest Service, accustomed since 1905 to dealing with local and regional groups as well as local communities. One result of the litigation has been the development of a body of environmental laws.

Sierra Club activity was not noticeable in Alaska until the late 1960s. The Sierra Club Bulletin had published an article by Stewart Edward White on the bear situation on Admiralty during the 1930s, but the club took no active part in either the movement to create Glacier Bay National Monument or to create a national monument on Admiralty. Its interest in Alaska, therefore, has been a recent development.

In February 1970 the Sierra Club brought suit against the Forest Service, declaring the Juneau sale to U.S. Plywood-Champion Papers illegal. Its charge was that the sale violated administrative procedures and the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. The Sierra Club was joined by local conservationists—the Forest Service by U.S. Plywood-Champion and the state of Alaska.

Sierra Club v. Hardin had the effect of stopping action for both the Forest Service and the company. The Forest Service was stalled on perfecting its detailed multiple-use plans for the west side of Admiralty, while the loss to the company was enormous. The trial was originally set for August 17, 1970; the Sierra Club asked for a postponement, and it was finally set for November fourth. [56]

|

| Tracy Arm on the Tongass National Forest is part of the Tracy Arm—Fords Terror Scenic Area. (U.S. Forest Service) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

10/history/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 06-Mar-2008