|

A History of The United States Forest Service in Alaska

|

|

Chapter 8

Epilogue: 1971-1979

The application of the conservation principle necessarily moved in different directions as one or another problem became important.

—Gifford Pinchot, "How Conservation Began in the United States," Agricultural History 11 (October 1937): 264.

Perhaps the biggest organizational change during my present assignment in Alaska has been the emphasis on bringing fisheries, wildlife, and other specialists into the organization. Early in my assignment, I met with Governor Hammond and other state officials to propose a special fisheries-wildlife program emphasis under the provisions of the Sikes Act and other authorities. The governor and his key staff and the congressional delegation enthusiastically supported this program. Forest Service Chief John McGuire and Assistant Secretary of Agriculture M. Rupert Cutler also strongly supported this emphasis, and we were able to obtain additional funding and manpower ceilings to get this program emphasis underway. Thirty fishery and wildlife biologists have been added to our planning and program staffs during the past three years, compared to four on board in 1975. This emphasis has also had substantial public support.

—John A. Sandor, letter to the author,

December 12, 1979

Introduction

The history of the Forest Service in Alaska during the 1970s is one of dramatic change and heated controversy. A series of problems, accumulating over the years, came to culmination during this period. Alaska, a peripheral area in land management over most of its history, now became the center of national interest. The historian finds himself confronted with masses of contradictory and confusing data, but four themes may be stated.

First, it was a period of strong and sometimes enlightened leadership on the part of both Congress and the presidents. The legislative record of the successive Congresses ranges from correcting deficiencies in the Organic Act of 1897 to establishing new agencies. Presidential leadership, following in the paths of John Kennedy and Lyndon Johnson, was also strong, and sometimes drastic. State leadership was strong, culminating in good legislation that furthered state-federal cooperation in game management and timber management.

Second, Alaska became the proving ground for environmental law. Just as the Roosevelt-Pinchot policies met a series of legal tests in the administrations of Roosevelt and Wilson, so the legislation of the Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon eras underwent legal tests during this era. Sierra Club v. Hardin was but the opening gun of a series of cases and controversies, ranging from business monopoly and environmental concern to the interpretations of the president's power under the Antiquities Act.

Third, attitudes toward federal policy and state land policy and use reflected the growing socio-economic changes and power structure within the state. "Environmental" groups had in the previous eras been small in number and moderate in approach. In the period from 1968 to 1979, they burgeoned and proliferated. Like those in the Lower 48, they were noisy, often ill-informed, litigious, and hell-bent on confrontation. Their tactics and sense of responsibility varied from group to group, and they deserve intensive analysis. They reflect the growing economic diversification within the state and an increasing willingness to engage in participatory democracy. A second power group were the Alaska Natives. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 gave Native groups both money and land, and with this increased power, rather than operating on a tribal basis, they organized into corporations, which became a base for political and economic power.

Fourth, there was some loss of power in the Forest Service as an administrative agency, both on the national and regional levels. Under Chiefs Edward Cliff and John McGuire, the Service had to brace itself against numerous attacks from pressure groups like the Sierra Club, face lawsuits attacking its basic methods of operation, and ward off interagency fights by empire builders and ambitious politicians. In addition, legislation stressed accountability and congressional oversight at the expense of administrative discretion. These struggles were carried on within the region as well, as Charles Yates and John Sandor fought to adjust local goals to national objectives.

Within the region there were fundamental administrative changes. Multiple use, an article of faith in the Forest Service since its inception, gave way in many areas to single use or dominant use. The pattern of ownership in the Alaska national forests became diversified with the great land rush of the 1970s. In the post-Civil War period in the western states and territories, there was a land rush by corporations and settlers to take full advantage of a generous policy of disposal of the public domain. A similar rush is now taking place in Alaska. But the similarity is imperfect, since the early rush was by absentee capitalists, largely from the East, carpetbaggers bent on getting rich and making money. The present corporations are resident capitalists with varying views. There is some irony in the fact that the Bering River coalfields, first filed on by absentee capitalists under the pernicious Alaska Power-of-Attorney Law, are now sought by Chugach Natives. The net result of this, and of continued state selections, will be a diversified pattern of forest ownership such as has existed in the states since the Forest Service was established. The new diversified ownership is both a challenge and an opportunity. The Pacific Northwest might serve as a model for Alaska. In the beginning the Forest Service found the diversified ownership a source of conflict, but District Forester E. T. Allen formed a "Triple Alliance" of private, state, and federal timberland ownership in the Pacific Northwest to work on common problems and establish a model of cooperative federalism. Alaska may well follow the same pattern; both the state and Native groups seem at this writing to be moving in that direction.

Those who have followed the history of the Forest Service through the years will perceive a variety of ironies in the course of Alaskan forestry. Afognak Island, reserved primarily as a fish and forest preserve, became a multiple-use area after World War II. Now much of it may go into private ownership. The mud-banks of Controller Bay, once the scene of another controversy that removed it from the national forest, are now reserved as a refuge for the trumpeter swan. Admiralty Island, conceived by the Forest Service as a multiple-use area, and the scene of some of the bitterest controversies, is now a national monument. Misty Fiords National Monument, the first addition to the southeastern Alaska national forest system, was originally proposed by Will Langille as a source of timber. The process of scientific investigation has become steadily institutionalized, from the early recommendations of Will Langille, applying such scientific principles to the forest as he had learned from John Gill Lemmon and Wilfred Osgood, through the gifted Harold Lutz and the many-sided Raymond Taylor, to team research and interdisciplinary investigation.

|

| C.A. Yates, 1971-1976. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Personnel and

Planning

Howard Johnson was succeeded as regional forester by Charles A. Yates. Yates was a Californian who had spent much of his professional career in his home state. He began as a CCC employee (1934-1936) in the Trinity National Forest. He attended junior college from 1937 to 1938, then worked for the Forest Service in the Shasta National Forest until 1941. His work was interrupted by the war; he entered as a private in the 82nd Airborne Division, served as a paratrooper officer in the United States, England, France, Belgium, Holland, and Germany, and then ended the war as a captain in 1946. He then continued his education, graduating from Oregon State University in 1948.

From 1947 to 1971, Yates worked on a variety of jobs in California—fire control assistant on the Plumas, assistant ranger on the Cleveland, ranger on the Six Rivers, fire control officer on the San Bernardino, and forest supervisor on the Klamath. In 1962 he shifted his sphere of responsibilities briefly to the Rocky Mountain Region as assistant regional forester. He returned to California as deputy regional forester in 1966 and came to Alaska in February 1971. [1]

Yates came at a time of change and turmoil. He endured trial 1 and 2 of Sierra v. Hardin and other environmental suits, and he answered a series of magazine articles attacking the Forest Service. He stopped the Alaska Lumber and Pulp Company from logging until a thorough study of the West Chichagof-Yakobi area was completed. Ranger districts were ended during his term. He carried out a reorganization plan initiated by his predecessor, moving headquarters of the North Tongass from Juneau to Sitka and creating headquarters for the Stikine Area in Petersburg. He created the Alaska Planning Team and carried on a host of other activities. His administration was one of change and controversy.

|

| J.A. Sandor, 1976-present. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Yates was succeeded by John A. Sandor in 1976. Sandor, a native of the state of Washington, served in World War II, then attended Washington State University to receive a bachelor's degree in forestry and range management in 1950. Later on, he took educational leave from the Forest Service and did graduate work at Montana State University and at Harvard. He had a conservation fellowship at Harvard and earned a master's degree in public administration there in 1959.

Sandor worked for the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment in various capacities in Oregon, Washington, and Alaska. He came to Alaska when Arthur Greeley was regional forester and stayed for some years. He served in personnel management for the Southern Region in Atlanta from 1965 to 1968; assistant to the chief in Washington, 1968-1971; and deputy regional forester, Eastern Region, in Milwaukee, 1971-1976. Active in the Society of American Foresters, he helped form the Alaskan chapter and section. He also was national chairman of the Natural Resources and Environmental Administration Section, American Society for Public Administration, and serves on the section's Board of Directors. [2]

Sandor brought organizational changes to Alaska. Robert H. Tracy was appointed as deputy regional forester. Tracy was a 1951 graduate of the School of Forest Management at Colorado State University. He served from 1951 to 1967 in the Pacific Northwest—on the Rogue River National Forest in timber management, on the Gifford Pinchot National Forest in timber management, on the Malheur as district ranger, and on the Mount Hood in the supervisor's office. From 1967 to 1969 he was in California on the Shasta-Trinity National Forest as deputy forest supervisor. In Region 4 he served from 1969 to 1973 as a supervisor. He came to Alaska in 1973, serving first as assistant regional forester for resources, then from 1977 on as deputy regional forester.

Substantial administrative changes were made in the Alaska Region, and more are pending. Three supervisor districts were established on the Tongass. These are the Ketchikan Area (Ketchikan), the Stikine Area (Petersburg), and Chatham Area (Sitka). However, the ranger districts, dropped in 1973, were to be reestablished in 1980-81, ten to twelve in number. [3]

Both Yates and Sandor gave much energy to land-use planning. The statutory and administrative bases of each of these should be briefly stated, since they constitute a series of interrelated directives.

1. The Wilderness Act of 1964 called for classification of all roadless areas of more than 5,000 acres for wilderness study, with wilderness status to be determined by act of Congress rather than by administrative decision of the Forest Service.

2. The Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 (RPA) called for intensive planning and direction. This was modified and clarified with the National Forest Management Act of 1976 (NFMA), made necessary because the Monongahela decision invalidated part of the Organic Act of 1897. It revises that act, focusing on land-management planing, timber management, research, public participation in decision making, and state and local forestry. It makes no break with the past acts, such as the Act of 1897 or the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960, but stresses intensive work and review, legislative oversight on the conduct of management, and the following of policy guidelines. Management should involve interdisciplinary teams to provide integrated land-management plans and revisions to overall plans every fifteen years. In timber management, "even flow" policy was affirmed by law. In silviculture it involved emphasizing production of sawtimber size and quality rather than pulp, scheduling final harvests in stands that had reached the culmination of growth, preservation of a diversity of plant communities and tree species, and preservation of wildlife habitat. Clearcutting was permitted if it was the optimum silvicultural method and consistent with other objectives of the act.

3. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) established the Council on Environmental Quality and provided for interdisciplinary examination and review of any action that might effect the natural environment. Broadly worded and far reaching, it has served as the basis for much litigation.

4. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 (ANCSA) provided for the classification of federal lands in interior Alaska into national interest lands, and it settled Native claims by giving them money and land, some of it on national forests.

5. Two acts were important in cooperation between state and the Forest Service. One state act provided for increased cooperation between state and Forest Service in forest management and protection. The Sikes Act of 1974 provided broad authority for the states to plan and carry out fish and wildlife management programs on national forest lands, and to control off-road vehicle use on these lands. [4]

Land-management planning, under the RPA and the NFMA, required work on four different planning levels, each of which deals with different aspects of the decision-making process. First was the directional planning level—defining Forest Service responsibilities, legislative mandates, and other binding mandates. On this level, a Southeast Alaska Guide was distributed, including sections on land management, planning direction, land-management policies, and the RPA. Second was the land allocation level, complying with directional decisions to define where combinations of land use would be made available. Six interagency task forces amassed information to determine how each of about 800 watersheds on the Tongass should be managed. Four categories of designations were applied. This, as the first step, involved public participation and cooperation with the University of Alaska. A tentative plan was developed for the Chugach in 1974 and for the Tongass by December 1978. Closely associated with this was the RARE II examination, identifying which areas were to be recommended for instant wilderness, wilderness study, special management, and multiple uses. A third level was the prescriptive level, determining how management activities were to be coordinated and controlled. This involved training of interdisciplinary teams and a socio-economic study to be carried out with the University of Alaska. A fourth was the implementation level, involving project plans, contract permits, and the like.

The planning process was long and complicated, both because of the complexity of the task and because of the turbulent political context—state and national—during which the task was carried out. Categories of land were divided into four land-use designations—LUD I, II, III, and IV. LUD I was wilderness, excluding mining exploration (after 1983), timber harvest, water projects, and roads, but permitting boat and air access. LUD II was wildlands, to be managed in a roadless state, but permitting wildlife and fisheries-habitat improvement and recreational facilities. LUD III would involve multiple-use management, including commercial production; and LUD IV emphasized production of commodity and market resources. [5]

Several distinct pressure groups can be identified in relation to the land-management plans and the RARE II program. The Alaska Loggers Association favored multiple use of forests, with limited wilderness. Two other groups supported them: the Citizens for Management of Alaska Lands (CMAL) and the Organization for Management of Alaska Resources (OMAR). CMAL was made up mostly of resource users and businessmen; OMER had more of the chamber-of-commerce development type. Both supported limited wilderness and submitted alternative plans. On the side of wilderness and nondevelopment, a variety of "environmental" and "conservation" groups were active. Environmental and conservation have become shorthand for those favoring reservation of land for noneconomic use. The terminology turns on its head Pinchot's definition of conservation as wise use. A group in the Panhandle formed the Southeastern Alaska Conservation Coalition (SEACC), with strong support in Juneau, Sitka, Petersburg, and Ketchikan. SEACC submitted an alternative plan. Other conservation groups focused their attention on the interior and the Prince William Sound—Cook Inlet area. [6]

The administration in Washington, through the secretary of agriculture, also submitted its own alternatives in regard to the Alaska lands, stressing the wilderness viewpoint. In addition, the state of Alaska worked closely in the planning process through the Department of Natural Resources and the Department of Fish and Game. In this, as in other resource matters, Governor Jay Hammond took a deep personal interest.

The RARE and RPA studies, however, represented only one aspect of the land-use controversy in Alaska. It was only one ring of a four-ring circus. Another was the allocation of land to Alaskan Natives, still another the national interest lands, and still another the state interests. As time went on, Congress increasingly played the role of ringmaster, and at times, some thought, the clown.

Alaska Native Claims Settlement

Act

The Wilderness Act and the RPA related to identification of wilderness and overall management. A second act related to land transfer to two owners—first, Alaskan Natives, and second, national agencies. The story is long and complicated.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANCSA) was passed on December 18, 1971. It has been subjected to several amendments, and more are proposed in 1979 (at this writing). It dealt with an overall settlement of land claims of Alaskan Natives, and also with classification and allocation of the public lands of Alaska. In regard to the Alaskan Natives, the act gave them a cash payment of $962 million and some 44 million acres of land, including 2 million acres for cemetery and historic sites. Native corporations were set up to manage the assets. In regard to other lands, it authorized the secretary of the interior to withdraw public lands (mostly BLM lands) to ensure that the public interest be protected, and in section 17 (d) 2, withdrawal not to exceed 80 million acres as units of Forest Service, National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service lands, or units of wild or scenic rivers. The act provided for the formation of a Joint Federal—State Land-Use-Planning Commission, with broad powers to recommend on land-use planning and allocation. A series of old acts was repealed, including the Native Alaskan Act of 1906, giving Natives allotments on the ground of past occupancy (like the early squatters' rights or Preemption Act). Applications pending at the time ANCSA was passed would be approved, but the Natives concerned would lose their rights to land otherwise available under section 14/h.5 of the act. In 1974, 7,500 claims were pending, and at this writing 230 are outstanding on national forest land.

To some in the Forest Service, the "highgrading" of land by Native corporations was a cause for alarm. They believed that it was obviously the intent of Congress to minimize, to the extent possibly consistent with achieving the intent of ANCSA, the impact of the act on wildlife refuges and national forests. Such intent was implicit in section 12 (2), which limited selection on the Chugach to 69,120 acres per village and on the Tongass to 23,040 acres per village, with no regional corporation selections on either forest except for historic sites and cemeteries. This would have limited selections on the two forests to 577,760 acres, plus cemeteries and historic site selections. However, amendments had increased national forest selections on the Tongass from 253,440 to 546,480 acres, which increased total national forest selections to 880,000 acres. At present, proposed amendments would triple the acreage to 1,600,000, three times that arrived at in 1971. The stated objectives of the involved Native corporations, "to consolidate ownership and to obtain land of like kind and character to land traditionally used," may be very persuasive. However, since the 605 individuals enrolled to Chugach National Forest are already receiving the equivalent of 343 acres of land of "like kind and character traditionally used," it would appear reasonable to believe that corporate economic interests rather than traditional interests are the motivating force behind these proposals. This is supported by the fact that of the 2,106 individuals enrolled to the Chugach region, only 871 or 41 percent reside in the region and would have occasion to use "traditional" lands). [7]

Management of the land would be by two levels of corporations: regional, based on the geographical region; and village, based on the settlement. Selection of village lands would be contiguous to the village, in a compact tract. In regard to cities, urban corporations were formed, with a larger area in the hinterland to select from, dependent on historical associations. Regional corporations had a larger area to choose from.

In the Tongass the regional corporation Sealaska was created, with headquarters in Juneau. Nine village corporations were formed and two urban corporations, Shee Atika in Sitka and Goldbelt in Juneau. Sealaska was entitled to select 270,000 acres, mainly from national forest lands; each of the village and urban corporations were allowed 23,040 acres (one township). This was in addition to a grant by the Court of Claims of 23,040 acres, affecting nine villages.

The allocations were subjected to some changes, and the following chart may indicate the major ones. Acreages, as regarded by the national forests, were as follows (provided by ANCSA and later amendments):

| 11 Southeastern Villages (includes Sitka and Juneau) | 253,400 acres |

| 3 Chugach Villages | 207,360 acres |

| 4 Koniag Villages (includes Kodiak) | 116,280 acres |

| 577,040 acres | |

|

PL 94-204 and 94-156 amended ANCSA and increased national forest selections as follows: | |

| 12 Southeastern Villages | 276,480 acres |

| Sealaska 14(h) (8) | 270,000 acres |

| 3 Chugach Villages | 207,360 acres |

| 4 Koniag Villages | 116,280 acres |

| 870,120 acres | |

|

Proposed increased in 1979 legislation included: | |

| 12 Southeastern Villages | 276,480 acres |

| Sealaska Region | 279,000 acres |

| 3 Chugach Villages 12(a) + 12 (b) | 264,000 acres |

| Chugach 14 (a) 8 | 30,000 acres |

| Chugach 12 (c) study, up to | 350,000 acres |

| 4 Koniag Villages | 116,280 acres |

| Koniag Exchange | 340,000 acres |

| 1,655,760 acres | |

This does not include the involved regions' share of the 2 million acres for cemeteries and historic sites. [8]

A series of questions developed, particularly in regard to the selections of regional and urban corporations. Much controversy centered around Admiralty Island. Angoon, the only Native village on the island, had adopted a way of life based on fishing and traditional means of livelihood. On the other hand, Goldbelt, Juneau's Native corporation, also had historical claims to Admiralty, as did Shee Atika, the Sitka Native corporation. Both desired timber production. Kootznoowoo, Angoon's Native corporation, feared that timber harvesting would disturb the traditional way of life. After a long negotiation, Goldbelt agreed to off-Admiralty lands. It was conceded a value-for-value exchange, with a premium to Goldbelt for the public interest involved. Negotiations with Shee Atika are proceeding. The recent creation of the national monument, however, makes it likely that their selections will be off Admiralty. In addition, Kootznoowoo has proposed that it be given off-Admiralty cutting rights, in order to preserve natural habitat on the monument. This matter is still under negotiation.

There were other problems. Sealaska had purposely overselected its 14/h.5 estimated acreage. To protect itself from loss of selection opportunity, the corporation overselected by about 100,000 acres. This acreage will be returned to full national forest status. In addition, part of Sealaska's priority selection lay close to the Yak-Tat-Kwaan selection near Yakutat. The act grants Sealaska selection rights near Yakutat only after concurrence by the governor of Alaska. The area chosen is in a tract that the governor feels should be in public ownership, and he has agreed to the Sealaska selection only if the corporation and Forest Service agree to exchange these lands for others within the Tongass. There was also some attempt by Chugach Natives, Inc., to select lands on the Tongass to compensate for other land selections that might be included in the proposed Wrangell Mountains National Park. The Forest Service objected to this, and the matter has been dropped. [9]

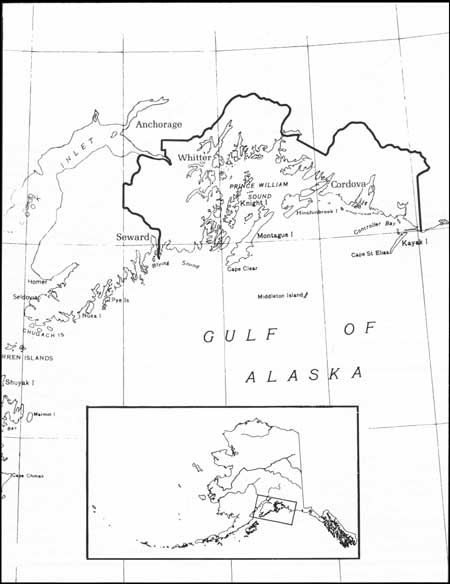

Selection in the Chugach underwent the same process. Two regional corporations, Koniag and Chugach Natives, were formed in the region. The corporations had, by 1978, identified about 15 percent of the Chugach National Forest for selection. Village selections accounted for 638,150 acres, mainly on Afognak Island and Prince William Sound. An additional 70,000 acres was sought on Prince William Sound. Native historical and cultural sites totalled 38,365 acres, with yet another 30,000 acres susceptible to selection. In addition, Chugach Natives sought to exchange land on the Bremner River for economically valuable land on the shore, including the Bering River coalfields, Icy Bay shoreline, and Montague, Knight, and Latouche islands. This would, in effect, exchange an area of mainly scenic value for one of great economic value.

The net effect of the selections in the Chugach have been loss of most of its economic base in regard to timber and recreation. Afognak, once reserved as a forest and fish culture reserve and then used as a multiple-use area by the Forest Service, seemed likely to revert to Native ownership. In addition, some of the other areas were specialized management areas, and others were subject to state selection.

In regard to state selection, in 1977 the state had applied for 104,907 acres in the Chugach National Forest. They were mostly scattered throughout the Prince William Sound area and concentrated near population centers of Cordova, Whittier, Seward, Moose Pass, and Cooper Landing. On the Tongass, 142,700 acres were selected, mostly near population centers of Juneau, Ketchikan, Sitka, Petersburg, and Wrangell. The total amount the state can select from the national forests is 400,000 acres. [10]

(d) 2 Lands

The (d) 2 land question, which still is unsettled, is also complex. Briefly, the question of Native lands and state claims raised conflicts about who got what. In 1966 Secretary Stewart Udall put a "freeze" on all transfers of title to public land in Alaska in order to get a breathing spell for legislative settlement. In addition to the Native settlement land, it laid out a planning procedure for public easements and transportation corridors and continued the land freeze for ninety days, during which time the secretary would determine which of the public lands would be temporarily with drawn in the public interest, i.e., (d) 1 lands. Section 17(d)2 allowed the secretary to select up to 80 million acres deemed suitable for national parks, national forests, wildlife refuges, or wild and scenic rivers systems in Alaska. Congress would decide to which system each area of the (d) 2 lands would belong by the end of 1978.

In March 1972 Secretary of the Interior Rogers Morton designated 80 million acres as (d) 2 lands and withdrew 47 million acres as (d) 1 lands for future study. He asked that a clear distinction be made between the public interest lands [(d) 1] and the national conservation system lands [(d) 2]. He asked that plans be recommended to him by September 1972.

The Forest Service set up the Alaska Planning Team, headed by Bernard A. Coster and including Verner W. Clapp, John A. Leasure, Carol B. Hutcheson, and Hatch Graham. They prepared a series of recommendations for new national forests in the interior. Eight new national forests were proposed in September 1972—Wrangell Mountains, Fortymile, Porcupine, Susitna, Lake Clark, Kuskokwim, Yukon, Koyukuk, as well as extensions of the Tongass and Chugach national forests. [11]

Study teams also were created for the National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. The NPS efforts were directed toward areas of outstanding scenic, recreational, or scientific interest; the Fish and Wildlife Service, toward waterfowl and seabird nesting and staging areas and big game range; the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, toward the rivers for wild or scenic value. All worked closely with the Institute of Northern Forestry at Fairbanks in the collection of data, and all presented volumes of elaborate studies. In addition, the Soil Conservation Service identified 20 million acres of agricultural land, plus more than 18 million acres of grazing lands. The Bureau of Mines and Geological Survey made reports on mineral resources. [12]

In December 1973 Secretary of the Interior Morton announced his decisions and sent to Congress proposed recommendations for the four federal systems in Alaska. The recommendations included creation of three new national forests, plus additions to the Chugach. These were the 5.5 million-acre Porcupine National Forest, including the Yukon Flats and some substantial forestland; the Yukon-Kuskokwim National Forest, 7.3 million acres in area with about 2.8 billion board feet of commercial timber; and the 5.5-million-acre Wrangell Mountains National Forest, in two units flanking the proposed Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. Two areas were proposed as additions to the Chugach, both of them glaciated areas—185,760-acre College Fiord and the 395,400-acre Nellie Juan region. These would be managed primarily for recreation.

With these recommendations made, the Forest Service planning team made detailed studies of the proposed areas. The planning team, over the years, had a mixed membership, as some were transferred and others came on. Barney Coster was transferred to Washington. Those working on the team over the years included Marcus W. Petty, Gerald J. Coutant, John Galea, Hatch Graham, Carol B. Hutcheson, Adela G. Johnson, Michelle M. Michaud, E. Jane Mullings, Sigurd T. Olson, Ray T. Steiger, and Pamela D. Wilson. Elaborate area guides were prepared for each of the national forest areas considered. Other agencies had similar planning groups and made studies of proposed national parks, wildlife refuges, and wild and scenic rivers. There was obvious competition among the agencies as to, first, how the area was to be used, and second, boundaries between different agency lands. [13]

From the clear fresh air of the taiga and forest, we may shift to the toxic atmosphere of Washington. Between 1974 and 1978 a large series of bills was introduced annually. Their sponsors included Senator Henry Jackson of Washington, who generally favored balance of multiple-use and park lands; Representative Morris Udall of Arizona, the spokesman for the preservationists in Alaska; and Representative John Dingell of Michigan, whose chief interest was in wildlife refuges. Both the state of Alaska and the Joint Federal-State Land-Use-Planning Commission favored setting up a new system of lands, under joint federal-state study and classification for primary use. Representative Don Young and Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska also introduced bills, strongly stressing multiple-use areas and also favoring some areas under joint federal-state management. They also recognized the need for transportation corridors.

After 1977 there occurred important shifts in the alignment. One was the fact that an Alaskan Coalition, made up of groups such as the Sierra Club, Defenders of Wildlife, Environmental Defense Fund, Friends of the Earth, Western Federation of Outdoor Clubs, Wilderness Society, and National Parks and Conservation Association, formed a strong and well financed lobby to push for the maximum acreage in single-use rather than multiple-use units. Those favoring multiple use could not get a countervailing force. The Society of American Foresters and the American Forestry Association came out for a balanced bill, but it failed. The second shift was in administration, with the accession of President Jimmy Carter. Rogers Morton, as secretary of the interior, had been a suave and skillful politician, adept at reaching compromises; and Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz had strongly defended his department. Cecil Andrus, the new interior secretary, had what one Forest Service officer called a "bulldozer approach" to matters and was therefore harder to bargain with. Secretary of Agriculture Bob Bergland seemed to lack the decisiveness of Butz, and Assistant Secretary Rupert Cutler was also weak in protecting the aims of the Forest Service in the area.

|

| Secretary of Agriculture, Earl Butz, discussing D-2 with Congressman Don Young. (Office of Congressman Young) |

With 1977 came hearings on the alternatives. Udall had succeeded in introducing to the House a bill strongly weighted in favor of the parks. Hearings were held in Alaska on the proposed bills by the Subcommittee on General Oversight and Alaska Lands of the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. The hearings showed a deep division among Alaskans as to the uses of the lands and their administration. Admiralty Island status; subsistence hunting and fishing; transportation corridors; the amount of timber harvest necessary to the economic well-being of the southeast, and the interior as well; snowmobiles, airplanes, and powerboats in wilderness areas; "rape" of the land, "tying up" of resources, mining activities versus scenic beauty; development of previously undeveloped areas; the role of local people, and of the state, in management; relationships of Indian lands to park enclaves—all these issues were discussed in mass meetings in Fairbanks, Sitka, Juneau, and Anchorage, and in town meetings in the interior and on the coast, such as at Fort Yukon, Bethel, Dillingham, and Kotzebue.

The Alaska Coalition united on HR 39, representing the strongest support of the National Park Service and Fish and Wildlife Service. Skillfully presented in the House by Representatives Udall and John Seiberling, it was brought to a vote in 1978 and passed the House by a large margin. In the Senate, also, it gained ground, despite opposition by Senators Mike Gravel and Ted Stevens. However, the deadline for a decision on the (d) 2 lands was approaching; the Alaska senators apparently had difficulty in agreeing on tactics and strategy, and increasing support grew for the Senate version of the House bill. Debate on the bill ended, however, when Senator Gravel threatened a filibuster, and the session ended without any decision. [14]

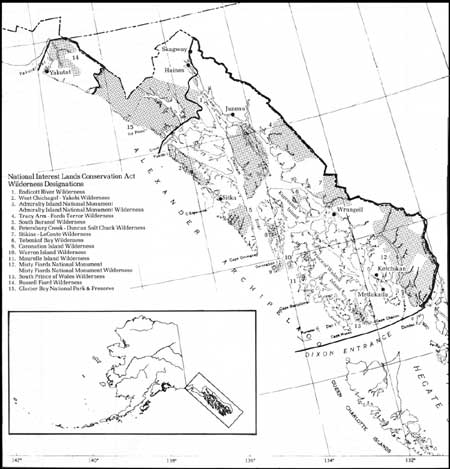

Failure to act led to presidential action. One hundred and forty-six members of the House urged presidential action; both Bergland and Cutler supported action, also. Consequently, On December 1, 1978, President Carter used his power under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to set up seventeen national monuments, totaling 55,975,000 acres. An additional 38,930,000 acres were designated as national wildlife refuges. It was a clear triumph of single-use designation over multiple use, and it was a victory of the Alaskan Coalition.

Two proclamations in the Tongass effected the Forest Service. Both Admiralty Island and Misty Fiords were designated as national monuments, to be administered by the Forest Service. This represented a break with tradition, since the Transfer Act of 1933 had given the National Park Service sole jurisdiction over national monuments. It ended a forty-year controversy over the status of Admiralty. Misty Fiords represents one of the ironies of history, since this was the first addition to the Alexander Archipelago National Forest and the first unit of the Forest Service in Alaska to be designated "Tongass." Its original creation was not because of its scenic beauty, but as a timber reservoir for the Ketchikan lumber industry and to curb Canadian log theft across the Portland Canal. So far as the Chugach is concerned, some of the additions are adjacent to the forest. They are of recreational and wildlife value and will represent a new area of cooperation between the Forest Service and the Park Service. [15]

|

| Congressman Young gives testimony on leg hold traps before the Interior and Insular Affairs Committee. (Office of Congressman Young) |

Legal Struggles

The administrations of Yates and Sandor were marked by an unending series of legal cases and controversies. A large number of issues involving the Forest Service and other resource agencies continued during this decade. Many pressure groups evolved in Alaska.

Several things account for this phenomenon. One was the vast amount of legislation passed during this term. Some acts, such as the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, were complex and, hence, controversial. The National Environmental Policy Act lent itself to litigation and was as deadly, and occasionally as random, in its operation as was the Allen Pepperbox in the hands of the frontiersman. Old statutes, such as the Organic Act of 1897, came under attack. The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act of 1971 lent itself to land-grabbing and pressure-group action.

A second factor was changes in the composition of the courts. Court decisions have gone through cycles, and courts have played important parts in shaping federal conservation policy. The courts in the 1970s became as important in the development of environmental law as was the Taft-Wilson court in interpreting Pinchot-Roosevelt conservation policies. Traditionally, the court had recognized "standing" as primarily economic standing; in other words, individuals would have to show direct personal injury before being allowed to sue. The present courts give standing to noneconomic groups and individuals, and hence broaden the base of those who can litigate. Second, the court has taken the bare meaning of words, rather than congressional intent or administrative discretion, in interpreting statutes. Third, the court has leaned in favor of participatory democracy rather than expert opinion. [16]

A third factor contributing to legal disputes and controversies has been changes in the nature and tactics of pressure groups. The Sierra Club, as noted earlier, had begun as a California organization. It began its expansion about 1940 when it took over the Western Association of Outdoor Clubs and made that organization a sounding board for its own policies. By 1960 it had begun a program of national expansion. Carefully misunderstanding the term multiple use, it alone, of all major outdoor organizations, opposed the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act of 1960. Aided by grants from the Ford Foundation, the club began a series of litigations against the Forest Service, beginning in California and by 1968 moving to Alaska. Noisy, unscrupulous, and adept in using the big lie and the glittering generality as publicity gimmicks, the Sierra Club epitomized the idea that the ends justify the means. [17]

The club's establishment of an Alaska chapter spawned a large number of other organizations. Some were apparently affiliated with the Sierra Club and followed its lines fervently; some remained independent. At least nine organizations formed chapters of the Alaska Conservation Society, claiming as its objectives wise use of renewable resources, preservation of the scenic, scientific, recreational, wildlife, and wilderness values of Alaska. The Sitka branch, established in 1968 and apparently the one with closest ties to the Sierra Club, succeeded in obtaining a five-year moratorium on logging in the West Chichagof-Yakobi Island areas. The Kodiak-Aleutian branch sought court action against a timber sale on Afognak Island. A coalition of clubs in southeastern Alaska kept up a constant barrage of criticism of Forest Service policies. [18]

The major cases and their dispositions may be summarized as follows:

Sierra Club v. Hardin. As noted in the previous chapter, the Sierra Club challenged a Forest Service timber sale on environmental and other grounds. It was tried in federal district court in Alaska, and the Forest Service won its case. Although the court said that the Sierra Club had "standing" in the case, the court felt that the Forest Service had shown compliance with the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act. Laches—unreasonable delay—in bringing legal action was one factor in the decision.

Then came a long series of delays and appeals. The Sierra Club waged a war of attrition, using all of law's delays to postpone action, with the aim of putting the involved company to continued expense in the matter. An appeal was held in federal circuit court in California. However, new evidence was presented. A. Starker Leopold and Richard Barrett, in a study on the effect of clearcutting on wildlife, argued that large clearcuts destroy the habitat of the Sitka deer and that cutting would endanger bald eagles. The case remanded to the district court. Revision of clearcut areas would lessen the timber base for the sale. The Forest Service and Champion Plywood agreed to a bilateral cancellation of the sale in 1976. [19]

Izaak Walton League v. ButzZieske v. Butz. Over the years there had developed some criticism of clearcutting practices. These attacks were not new; C.J. Buck, regional forester in the Pacific Northwest during the 1930s, had been opposed to clearcutting. However, determined attacks on the Forest Service clearcutting policy came after studies by foresters at the University of Montana and a propaganda campaign by the Sierra Club. The matter came to a head in the case of Izaak Walton League v. Butz. A loophole was found in the Organic Act of 1897, in which the secretary was authorized to sell dead or mature timber, marked. In 1973 the court took the literal words, rather than the meaning and practice used by foresters, and held clearcutting illegal on the Monongahela National Forest of West Virginia, and by implication elsewhere. The Sierra Club immediately added this to Sierra Club v. Hardin. Meanwhile, in Zieske v. Butz, a suit brought by the Sitka branch of the Alaska Conservation Society and residents of Point Baker, the court ruled that only mature trees on Prince of Wales Island could be cut under a contract by Ketchikan Pulp Company, holding that the actual legality of clearcutting was a matter for Congress to decide. However, the court rejected charges by Point Baker residents that the company violated four other federal laws, including the National Environmental Policy Act. The prohibition of clearcutting applied only on the island. [20]

Alaska Conservation Society, Kodiak-Aleutian Chapter v. Forest Service. This controversy related to the Perenosa sale on Afognak Island. A sale there was made in 1968 for 525 million board feet. No activity took place on the sale for five years. With the agreement of the purchaser, the Forest Service made an environmental modification that reduced the volume to 332 million board feet. The modification reduced clearcut sizes, protected streams and wildlife values, and in general was more sensitive to resource values. The modification was accepted by the purchaser in 1974. In the same year, however, the Kodiak-Aleutian chapter of the Alaska Conservation Society brought suit in federal court at Anchorage, alleging that the sale was a violation of the National Environmental Protection Act, that the existing environmental impact statement (EIS) was inadequate, and that the sale would violate the Federal Water Pollution Control Act. Meanwhile, however, Alaska Natives in the claims settlement obtained title to about one-third of the island, and the suit was dropped. [21]

Not directly related to the national forests was the controversy over the Copper River Highway. This involved a highway connection to Cordova from the interior. As mentioned before, there was a road built on the old railroad bed that before 1938 carried copper ore out from the Kennecott mines. The 1964 earthquake, however, knocked out the bridges, and Cordova still sought a road connection with the interior. With the revival of a proposal to create a national monument in the valley of the Chitina River, the state made studies of a projected road and selected a route. A clause in the Transportation Act of 1968, however, called for studies of alternative routes over potential park lands. The state made its own study and filed a 4 (f) statement and a state EIS. The Alaska Conservation Society and the Sierra Club claimed that alternative routes by ferry and by air had not been fully considered and that the state EIS was not adequate to satisfy federal standards. They sought an injunction in March 1973. The projected road also went through proposed (d) 2 lands. The issue at this writing remains unsettled. [22]

U.S. Borax and Chemical Corporation and Pacific Coast Molybdenum Company v. Bob Bergland and M. Rupert Cutler. This case was filed on May 17, 1979, and is described in some detail since it is apt to set important precedents.

In 1974 U.S. Borax made some molybdenum discoveries at Quartz Hill, forty-two miles from Ketchikan. A number of claims were established, and some were transferred to Pacific Coast Molybdenum. The companies asked for an access road eleven miles in length to take out ore for analysis. The forest supervisor in Ketchikan sent a team of specialists to examine the proposed road site. They were aided by a state task force, appointed by Governor Hammond. The completed EIS was submitted to the Council on Environmental Quality on July 18, 1977, and the permit was issued on November 4, 1977.

A group headed by the Sierra Club and including the National Audubon Society, Wilderness Society, Alaska Conservation Society, Tongass Conservation Council, and representatives from several fishermen's societies and the Ketchikan Native corporation made an administrative appeal. Regional Forester Sandor held public hearings on the matter in Ketchikan on February 1, 1978. On March 31, 1978, he supported the supervisor's decision and issued a road permit. The Sierra Club and its supporters appealed to Chief John McGuire in written and oral statements, but on October 4, 1978, he supported the regional forester's decision. However, Assistant Secretary of Agriculture Cutler reversed the decision, holding that helicopters could be used for getting ore out for bulk sampling. Meanwhile, the area was withdrawn within the Misty Fiords National Monument. U.S. Borax and Pacific Coast Molybdenum brought suit, alleging that helicopter access was not feasible. [23]

Finally, with Carter's creation of national monuments in the closing days of 1978, the state of Alaska brought suit against the federal government. Summarized, the suit had the following points:

1. The established national monuments conflicted with state land selections.

2. The National Environmental Policy Act requires environmental impact statements and disclosures of the effects of the action. This was not done.

3. Creation of national monuments by proclamation violates separation of powers.

4. Withdrawal should not stop the state from filing on its land selections and getting state patent.

5. Failure of government to act on state selections violated the Statehood Act.

6. Failure to promptly convey Native lands impedes the state's rights to select land.

7. Rejecting state land selections exceeded governmental authority.

The outlook for the future is full employment for the legal profession in cases involving Alaskan lands. The cases will involve several areas—land selection, land fraud, and land use.

It was obviously the intention of Congress to minimize, consistent with terms of the act, the impact of the Alaska Native claims settlement on national forests and wildlife refuges. However, much more land will come from the national forests than was originally intended. Also, the land has been "highgraded"; the areas most suitable for timber production, recreation, trade, and the like have been taken. This creates a series of problems for the Forest Service in regard to access to isolated areas, management of cohesive economic or recreational units, and so on. It will place many areas best suited for public interest lands in the hands of private corporations. [24]

Many cases will involve fraud. Land legislation in the United States, no matter how well intended, has been used by the greedy or unscrupulous for private gain, and laws passed for the highest of motives may be perverted. Such was the case with the Alaska Power-of-Attorney Law for locating copper, oil, and coal mining claims, or the Forest Lieu Section in the Forest Reserve Act of 1897 (Organic Act). The ANCSA was no exception. Villages entitled to land, based on a population of at least twenty-five by the 1970 census, quickly increased in number as it became apparent that living there would be financially advantageous. Frauds have allegedly occurred on the North Slope, where abandoned settlement sites would suddenly blossom out with mobile homes and snowmobiles, helicopter-lifted into the area. Other areas, with few or no people, suddenly became populated. It is alleged that photos of Army personnel at a rest camp on Afognak Island were presented as evidence of Native population; and Chenega, wiped out in the 1964 earthquake, became the basis for land claims. There are allegations of BIA complicity, and congressional acquiescence, in these frauds. These phenomena will undoubtedly receive congressional and legal investigation. [25]

A third area, already touched on, will be controversies over whether areas are reserved for use and from use. The U.S. Borax case will probably be followed by others. The legality of Secretary Bob Bergland's action in closing wilderness areas in Alaska to mining, five years in advance of the statutory date under the Wilderness Act, will come under scrutiny. A fourth serious challenge will arise under the NEPA in regard to hydroelectric development, mining, lumbering, and road building. For the next decade, Alaska will be a key area in the testing and development of environmental law. [26]

Research

These controversies consumed much time and energy, but the routine work of the Forest Service went on. The 1960s and 1970s saw new directions and new points of view in research. The Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, the parent unit of the Alaska establishments after 1967, shifted in the direction of environmental concern. With the passage of the words ecology and environment from their customary use in the biosciences and forestry into the national vocabulary, the reconciling of environmental quality with industrial and economic considerations began in earnest. This battle, as we have seen, was fought out in the political and managerial areas. It became a matter of concern for the research arm of the Forest Service as well. This involved new studies on alternative means of logging, such as helicopter and balloon logging; questioning of the clearcutting method of handling Douglas-fir and hemlock forests, and experiments with shelterwood or other types of management; studies of the residual effects of pesticides and studies of silvicultural or biological ways to control insects; use of computer programming to give different perspectives to the landscape and to show the visual impact of timber cutting; use of fertilizer to increase growth; and retooling of research projects into interdisciplinary teams. As an elite corps, with a fair degree of independence, research scientists provided factual information on which managerial judgments could be based.

Much of the basic research in Alaska was like a new edition of earlier projects carried out in Washington and Oregon. These included surveys of timber stands. In the southeast it meant refining earlier figures arrived at by first observers like Weigle, Heintzleman, and Flory, as well as later scientists. In the interior it meant a cooperative study with the state over a period of years. Soil classification in Alaska had lagged, as well as study of the relation of soil to timber growth. Erosion was a particular problem. It was found in the interior, for example, that firelines used to control forest fires in areas of permafrost grew into ruts.

The research covered two separate regions, the coastal and the interior, with work coordinated by the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station in Portland. The areas may be studied separately. [27]

The Interior

During earlier years forest research in Alaska's interior was carried on by scientists based in Juneau. The work of Raymond Taylor and Harold Lutz, for example, has already been treated. Others who traveled from Juneau to study interior forests included Austin E. Helmers and Robert A. Gregory. Gregory moved up to Fairbanks about 1960 to head up a silviculture research project. In 1962 Von J. Johnson came to lead a fire research project. Personnel in Fairbanks at this time comprised a field unit of the newly independent Northern Forest Experiment Station, with headquarters in Juneau. After several years in temporary offices, the personnel moved out to a new building on the campus of the University of Alaska. Initially this building was called the Forestry Sciences Laboratory; it was dedicated, along with the Bonanza Creek Experimental Forest, in the summer of 1963. (To confuse historians the Forest Service downgraded the Northern Forest Experiment Station in 1967, returning Alaskan operations to the jurisdiction of the Pacific Northwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. For several years after that, both Alaska project locations were known as the Institute of Northern Forestry. In 1970 this designation was used only for the Fairbanks unit, and the Juneau unit was termed the Forestry Sciences Laboratory. There were several further changes in terminology in the 1970s, but it need not distract us from the actual research carried on.)

In 1966 Richard J. Barney replaced Von Johnson as fire research project leader, and LeRoy C. Beckwith came as project leader for forest insects in interior Alaska. Gregory left in 1970 and Leslie A. Viereck took over as leader of the silviculture project, now called "Ecology of Subarctic Trees and Forests." In 1971 the decision was made to combine all three projects in Fairbanks into a single, multifunctional, research work unit titled "Ecology and Management of Taiga and Associated Environmental Systems in Interior Alaska." Charles T. Cushwa was the program leader until 1974, when C. Theodore Dyrness, the present program leader, took over. [28]

The work of the Fairbanks unit was multi-faceted. A major part of its work was in regard to wildfire, and here it worked closely with the BLM and the state of Alaska. Staff took part in a number of professional meetings and symposiums on the fire question. [29] Second in importance to fire was the inventory of timber resources in the interior. Of the 220 million acres inventoried in interior Alaska, the station found 105.8 million acres of forestland, with 22.5 million acres of forest of potential value in stands of white spruce, paper birch, quaking aspen, and balsam poplar. The potential of the stands compared favorably with that of the Lake States; stands in Minnesota average 574 cubic feet per acre as compared with 634 cubic feet per acre in interior Alaska. [30] The Institute of Northern Forestry also furnished much of the scientific data for the Forest Service and other agencies investigating and making recommendations on (d) 2 lands in the interior. It hosted a study team of forest researchers from Norway, Sweden, and Finland, who provided the state of Alaska and the Forest Service with an analysis of interior Alaskan forestlands, as compared with those of Fennoscandia. [31]

The general approach to research in Fairbanks is to study entire ecosystems and their environments, utilizing skills of scientists from many fields of expertise. Since management activities affect the entire forest ecosystem, research is aimed at determining management impacts on the system as a whole. Therefore, the scientists form multidisciplinary teams to study all aspects of the forest environment, forest protection, and timber management on the taiga and tundra. [32]

Coastal Alaska

In 1972 the Forestry Sciences Laboratory in Juneau came under the leadership of Donald C. Schmiege, who was transferred up from Berkeley. Schmiege, who had obtained his doctorate in entomology, fisheries, and wildlife at the University of Minnesota, had also done extensive work with the Wisconsin Conservation Department in the area of forest insects and diseases. Indeed, Schmiege had first come to Alaska in 1962 to do research on insects. Now, as program leader in the 1970s, Schmiege coordinated the multifunctional projects of fisheries, insects, and silviculture in a project titled "Ecology of Southeastern Alaska Forests." Some of the main tasks were (and are) to provide management with means of predicting growth and yield of even-aged stands of Sitka spruce and western hemlock in order to meet various objectives; to provide guidelines for avoiding windthrow in old-growth stands of these two species when harvested, so as to protect all researches; to provide a system for predicting damage by defoliating insects to all tree species; to provide technology for determining the role of small streams in producing juvenile anadromous fish, and the means of improving habitats for anadromous fish through stream channel structures.

The Juneau unit is also the center for the Forest Survey of Alaska, part of a national effort set up under the McNary-McSweeney Act of 1928. This involves a continuous timber inventory, study of how it is increased through growth and diminished through both use and natural causes. The survey, headed in Alaska by O. Keith Hutchison, also determines consumption of forest products and uses these data in helping formulate public and private forest policies. The survey project is responsible for implementing the above on all land in Alaska, except for federal and state parks.

The Juneau laboratory has a professional staff of thirteen. They work closely with other Forest Service personnel in the managerial areas, particularly wildlife and timber management, and with biologists of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). They also supervise a larger series of research grants to universities on various specialized projects. There were fourteen such grants, 1977-1979, involving the universities of Washington, Minnesota, and California, as well as Oregon State, Montana State, and Case Western Reserve universities. Current studies include six separate programs in fisheries, varying from evaluation of debris removal in small-stream ecosystems to spawning criteria for coho salmon. There are seven in pathology, several dealing with control of dwarf mistletoe, three in insect research, six in forest-wildlife habitat, and eleven active silvicultural studies. [33]

The studies have had immediate effects on management criteria. The record has been most satisfactory, probably, in regard to fisheries and management. [34] Both the ADF&G and the Forest Service found through research that logging can be conducted without having any great impact on fish runs. The commissioner of the ADF&G corrected erroneous statements on this subject during hearings on HR 39. [35] On the other hand, wildlife researchers found need to study modification of existing timber-harvest methods in order to protect the deer habitat in old-growth timber. There is no total agreement on this point at present; the effects of changes in timber-harvest practices will require continued study. [36]

Recreation

Recreation management during the 1970s reflected the trends of the times. Planning was modified by statutory changes, particularly RPA recommendations on dispersed recreation. Planning was also modified by conflicting views on land use, as expressed in actions by pressure groups and in public meetings.

Over the years there had come a variety of socio-economic changes that had their effect on recreational preferences. Both the environmental movement and the rise of the larger leisure class increased pressures for preservation of large areas in their natural state. A countervailing force was the desire for organized mass recreation, such as picnics, skiing, snowmobiling, and conducted tours. Boating has always been popular, but there has developed a new interest in sailing and kayaking. New interest grew in the heritage of the Alaskan Natives, as well as in the history and natural history background of the state. Communities underwent changes. Tenakee Hot Springs has been pictured in these pages as a sink of iniquity, inhabited by whores, pimps, and bootleggers, where the major recreation was of the bedroom variety. It has now become a retirement village with well-to-do seniors superimposed on the local population. [37]

In the Forest Service, the Visitors Information Service was shifted from the Division of Information and Education to Recreation. The Visitors Information Service continued its interpretive work on vessels of the Alaska State Ferry System, and it plans to extend services to cruise ships of other lines. It remains one of the most praised and valuable programs. Visitors centers also remain popular, and plans are made to build one at Portage Glacier.

The network of trails within both national forests was expanded, partly with aid from the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) and Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC). Trail shelters built during the 1930s by the Civilian Conservation Corps were found to be suitable after forty years, though some needed repair. YACC trail work included building a canoe trail across Admiralty Island, connecting lakes with portage trails, a program begun by the CCC. Campgrounds were also improved. Cabins in isolated areas, accessible only by trail, boat, or plane, continued to be popular; their number increased to 187 by 1977. Despite rampant inflation, rent on these Forest Service cabins remained at $5 per day. Sixteen campgrounds, twenty-seven picnic areas, and seven private lodges on Forest Service land also helped meet the needs of recreationists.

As noted previously, one of the major miscalculations of the Forest Service was to underestimate the visual impact of clearcuts and other disturbances on visitors. Under both Yates and Sandor, efforts were made to alleviate disturbances by dispersal and size, blending impacts with natural contours of the land and requiring prompt cleanup of debris left by economic operations. Starting about 1973, the Forest Service began using landscape architects to work with management, helping to inventory, evaluate, and set visual quality objectives for all areas of the forests. In cooperation with the University of Alaska's Institute of Social and Economic Research, detailed studies have been made to determine recreational preferences of visitors.

Two projects developed under previous administrations were delayed. Plans for the Seward Recreation Area, developed under Howard Johnson's administration, were postponed because of the land question. The proposal is not dead and is included in one of the current bills on Alaska lands (S. 9). Also, plans for a road and ferry system, connecting the islands from Ketchikan to Haines, were postponed—again because of the unsettled land question.

|

| One of the many National Forest cabins built for recreational use. (U.S. Forest Service) |

The Forest Service acquired its first archaeologist in 1974 and now has one on each national forest. They work closely with the Alaska Division of Parks in evaluating historic areas and buildings for the National Register of Historic Places. In the field they work in areas destined for timber harvest, identifying areas of archaeological significance. Their work is primarily confined to identifying sites to prevent their destruction. Archaeological excavations are rare, though the agency has carried on some on Prince of Wales and Baranof islands. [38]

A problem that will continue to grow is that of foraging and collecting on historic sites. Special targets are World War II airfields and wrecked planes. Many planes were flown across the interior to Russia during World War II, and several wrecks have been salvaged illegally. Another enthusiastic collector took out an abandoned plane from Afognak Island. Areas accessible by water are hard to protect, and this problem will likely increase.

The two new national monuments proclaimed by President Carter—Admiralty Island and Misty Fiords—remain under Forest Service management and under guidelines established in June 1979. The management plans are based both on the president's proclamation and on the wilderness character of the areas. The Alaska Department of Fish and Game continues to manage fisheries and game on the monuments, but under the overall supervision of the Forest Service.

Admiralty has one Native village, Angoon, which has been dependent on the island for subsistence hunting and fishing, firewood, water, gravel, and the like. Land adjacent to the village, selected under the ANCSA, would suffice for some of their needs. During the interim period, the monument management plan would disrupt their lives as little as possible, but, as mentioned before, the problem of Native lands in the area remains unsettled.

Admiralty continues to be accessible by air and powerboat. Mineral land entry is forbidden under the Federal Land Management Act, and the island has been withdrawn from entry under mining laws for a period of two years. Existing mining claims, however, can be developed according to an approved operating plan. On the Noranda claim, the problem of access threatens to become a matter of controversy. No commercial cutting of timber is permitted, but residents have free-use permits.

Publicity and educational material on Admiralty Island National Monument are being developed under manager K.D. Metcalf. These include illustrated brochures, studies of visitations made during the 1979 season, and plans for an interpretive conference in 1979. The YCC, YACC and CETA programs will be used for interpretive purposes as well as for constructing camps. The area will become a scientific laboratory for research in natural history. The Forestry Sciences Laboratory in Juneau already has two projects under way, one to study the brown bear population and a second to study migratory patterns of deer with the aid of radio transmitters.

|

| Hiking in the Herbert Glacier Area on the Tongass. (U.S. Forest Service) |

Misty Fiords, a larger and more rugged national monument, occupies about the same area that Langille recommended as the first addition to the Tongass National Forest in 1907. Included in the monument are several special areas already established by the Forest Service—the Walker Cove-Rudyerd Bay Scenic Area, the Granite Fiords Wilderness Study Area, and the New Eddystone Rock Geological Area. General regulations regarding hunting, trapping, and mining are about the same as for Admiralty, except that there is no Native village in Misty Fiords National Monument. The manager, James C. Kirschenman, has begun setting up an information service. Other plans include trail building and maintenance; care for the safety of visitors, especially boaters; use of "Volunteers in the National Forests" to aid in taking an inventory in natural history; and resolution of land-use conflicts. [39]

The proposal for preservation of totem poles, started under Howard Johnson, was brought to a successful conclusion in the 1970s. With Forest Service help and under Alaska State Museum supervision, the poles were collected and brought to Ketchikan. The preservation project there was delayed, in large part because of a complete change in museum personnel, but it was finally created. Joe W. Clark of the Forest Products Laboratory in Madison, Wisconsin played a key part in aiding the Forest Service, Alaska State Museum, and Sitka National Monument (renamed Sitka National Historical Park) to develop techniques for arresting decay and fungi growth in the totem poles, which were finally housed in the Totem Heritage Center operated by the City of Ketchikan. [40]

As noted earlier, the Forest Service cooperated closely with the Alaska Division of Parks, particularly in the location of historic sites and in plans for their interpretive and preservation programs. The historic sites included the route of the Copper River and Northwestern Railway, areas associated with the mineral rush to Katalla, the gold rush history of Juneau, and old trails and buildings in the Kenai. Forest Service archaeologists collaborate in this work. [41]

Wildlife and

Fisheries

Wildlife management has always been an important aspect of national forest management in Alaska. It has evolved over the years from W. A. Langille's recommendations for game refuges in 1905, through the work of the agency with the Alaska Game Commission, the work of L. C. Pratt with sportsmen's clubs in the Cordova area, bear management on Admiralty Island, elk management on Afognak Island, transplanting of deer on Hinchinbrook Island, and continuous study of the relationship of logging to fisheries. A series of trends marked the era of the 1970s. One was statutory. The Sikes Act of 1974 directed the secretary of agriculture to develop comprehensive fish and wildlife habitat studies in cooperation with state management agencies. This led to closer cooperation between the Forest Service and the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G). A five-year program was developed, with twenty-three cooperative projects involving fish habitat, eleven big game, eleven small game, six nongame (rodents, seabirds, and other bird communities), three threatened or endangered species, and two aquaculture. Second, the National Forest Management Act and the RPA reenforced the Multiple Use Act with respect to wildlife management. Third, the YCC and YACC offered a source of labor to carry out the projects.

The Forest Service had previously established a specialized management area at Pack Creek on Admiralty Island. New ones were now established, including the Stikine Management Unit on the Tongass, meant for waterfowl primarily but including other species, such as moose. Seymour Canal on Admiralty Island was set aside as a bald eagle management unit. The Copper River Delta was set aside as a waterfowl management unit. The Bering River-Controller Bay area, scene of the famous Controller Bay sensation in 1911, now became a special area for trumpeter swan. The portion of Chickaloon Flats in the Chugach National Forest was also recognized as a waterfowl management unit. Caribou were also given special attention on the Chugach, having spread to Resurrection Creek after being reintroduced to the Kenai Peninsula by the state. The Portage Wildlife Habitat Management Area was established in 1976 under cooperative management of the Forest Service, BLM, Alaska Department of Highways, and the Alaska Railroad. In a number of these areas, YCC and YACC help was used extensively—for example, in prescribed burning to improve moose habitat.

In regard to fisheries, the habitat improvement project instituted in 1962 under Regional Forester Hanson has already been mentioned. It was continued, and through 1975 more than 200 separate projects were completed on the Chugach and Tongass national forests. Costs of these projects were split between the Forest Service and the ADF&G. At the present time a complete inventory of fish habitat is being carried on in cooperation with the ADF&G. Also, the National Marine Fisheries Service is completing a survey of deactivated log transfer sites to determine persistence of bark accumulation and its effects on estuarian life.

A long list of separate projects, some with very high cost-benefit ratios, were planned. These included fishways on Irish, Navy, Dean, and Thetis creeks to open up spawning and rearing areas for chum and pink salmon, enlarging such areas many times over. Projects also include removal of natural barriers and logging obstructions in the streams of the Chugach, clearing of stream channels and conversion of borrow pits for road construction into coho breeding grounds, and cooperative studies of potential aquaculture sites.

The relationships of logging to commercial fishing and to wildlife habitat was long a matter of concern to the Forest Service. In regard to fishing, this involved the decision to retain a vegetative canopy over the streams to protect them against extreme temperature changes; construction of culverts and bridges that would not impede movement of fish; removal of logging debris or other obstructions in the streams; and study of the relationship of clearcutting to increase of nutrients added to the streams.

Although relationships of timber harvest to fisheries had been a matter of concern from the earliest days, that of logging to wildlife had not. Early wildlife management had focused on game refuges, closed seasons, and predator control. A shift in emphasis came during the 1930s through the influence of such men as Aldo Leopold, P. S. Lovejoy, and Durward Allen, who stressed preservation of habitat as a management tool and developed sophisticated studies of predator-prey relationships. Coastal Alaska lagged in development of game management, largely because the basic research had not been done on the relationships of old-growth forests to game habitat. Very few studies on the effect of logging on wildlife resources other than fisheries had been carried on.

A case in point is the winter range of Sitka deer. Research in the coastal forest in the south—Washington and Oregon—had indicated that the clearcut areas, because of rapid growth of brush and other browse, made good deer habitat. This assumption was held by earlier managers. Studies in the 1970s indicated that this was possibly not the case in southeast Alaska, where old-growth forests were superior to cut over areas or new forests for winter range, partly because the canopy prevented heavy snow from penetrating the forest and partly because of the abundance of browse in the understory of old-growth forests. Tentative conclusions were that deer fare better in old-growth forests (over 200 years old) than in new ones. Studies also were made on the need of cover for mountain goats during the winter and on the effects of harvest of old-growth timber on birds and small mammals.

Wildlife management will continue to be of increasing importance in Alaska. This will be particularly true with the establishment of large wilderness areas on the Tongass and with the increasing orientation of the Chugach toward recreation. It will involve the Forest Service in closer relationships and possibly conflicts with the "subsistence hunting" rights of Indians, as more and more land comes into the hands of Native corporations. [42]

Human Resources

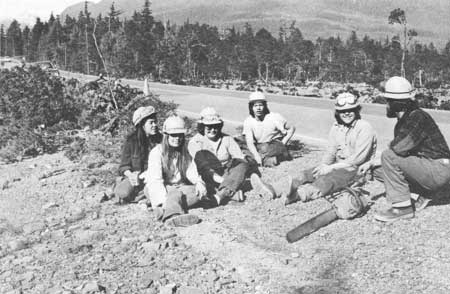

Forest Service work in human resources has intensified during the 1970s. This work is comparable to that of the CCC during the 1930s. Under Public Law 93-408, the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC) and the Young Adult Conservation Corps (YACC) made much the same kind of contribution.

The YCC was designed to give work to youths fifteen to eighteen years old, providing employment and at the same time giving the enrollees conservation education. A pilot project was established in 1970 with 48 enrollees. By 1978 the number increased to 153. These young people built recreation cabins and trails, engaged in fish-habitat improvement activities, worked in the Kenai to improve moose habitat by prescribed burning, and improved campgrounds. Highly motivated and energetic, they made it possible for the Forest Service to carry on activities that otherwise would have been too costly.

The YACC furnished jobs for 16-24 year olds, giving them gainful employment for a year in conservation work and training in general work skills. They have been active in heavier work, such as building a canoe trail across Admiralty Island. In planning this work, the Forest Service cooperates closely with the Native corporations, the governor's office, and private corporations. The plan is to offer more than 450 man-hours per year over a five-year period.

YCC and YACC enrollees were stationed in camps, some of them restored CCC camps. These were of three types—residential, nonresidential, and spike. Residential camps were seven-day-per-week, live-in camps. In nonresidential camps, the enrollees lived at home and reported to work on a five-day-per-week schedule. Spike camps were those out in the remote country; they were temporary, largely tent camps where enrollees resided for ten-day work periods, followed by four-day periods at home. In 1977 there were seven residential camps with total enrollment of 473, fifteen nonresidential camps with 230 enrolled, and nine spike camps with 179 enrolled. Camps were managed by directors, and work crews were led by young persons chosen from the enrollees.