|

The Early Days: A Sourcebook of Southwestern Region History — Book 1 |

|

PERSONAL STORIES

Mr. O. Fred Arthur started as a Forest Guard on the Prescott National Forest in 1907, and retired as Supervisor of the Cibola National Forest in 1945. His well-written autobiography entitled, "Then: 1907, to 1945: Now, In the United States Forest Service," is in the Library of the Museum at the Continental Divide Training Center [now located at Sharlott Hall Museum, Prescott, Arizona]. Every student of the history of the Forest Service would enjoy the informative and exciting incidents related by Mr. Arthur. Space limitations prohibit the inclusion of his entire manuscript in the record. One incident, from his Chapter X, however, is quoted verbatim:

|

| Figure 11. "Hinderer Ranch", headquarters for Forest Officers on the Prescott District January 1914. |

THE SHOEMAKER FIRE

There were many noteworthy occurrences during these years such as the shutdown of the Sacramento Mountain Lumber Company operation, which included the logging trains, etc., because of the company's failure to observe requirements of the government: the Shoemaker incendiary fire which resulted in the killing of Shoemaker and Executive Assistant W.C. White; Ranger Galt's performance in moving Ed Pfingston, (fatally injured in a rock slide en route to a fire) from White Mountain through rough and inaccessible country. Galt's action which required three days of effort was rewarded by a letter of commendation from the Forester.

The story of the Shoemaker fire which occurred in 1927 may best be related by quoting my report to the Regional Forester:

In further connection with this case, reference is made to 'O-Fire-Lincoln, Capitan Pass Fire,' and 'O-Fire-Lincoln, Dry Canyon Fire.

On the evening of March 15, another fire occurred in the immediate vicinity of these two cases. Mr. Strickland left for it the following morning, reaching Capitan about 6:00 a.m. Later on that morning I received a telephone communication from Mr. J. A. Brubaker, formerly a Forest Ranger, to the effect that there had been shots fired, supposedly by T. H. Shoemaker, at certain fire fighter engaged in taking tools out of a car which was left near his house: that a little evidence had been collected already identifying Shoemaker with this fire. I then called Mr. French, Assistant Solicitor at Albuquerque, and told him in a general way what had happened and requested that he come down and assist in the collection of additional evidence and prosecution of the case in the event such action proved warranted.

Later I decided to go to the fire and left about 1:00 p.m. in the government truck, taking with me Executive Assistant, W. C. White, in order that he might assist in time and expense records and perhaps with incidental work on the fireline itself. Mr. White had previously served as Ranger on that District and knew the conditions and country thoroughly. We reached Capitan about 5:00 p.m. and met Mr. Stickland who gave us further particulars as regards the shot fired at fire fighters. The circumstances were as follows:

Ranger Bond had left the Baca Ranger Station with Mr. A. R. Dean, and Lloyd Taylor, a son-in-law of Mr. Dean's, and foreman of the Block Cattle Company, whose range was on the north side of the mountains, and extended over the fire area. In addition to chuck and fire tools, it appears that Ranger Bond had taken his rifle and Mr. Dean a six shooter which he borrowed in Capitan. They drove Mr. Dean's car. They met Ranger Beall in Capitan in his car, also loaded with supplies and some men. They drove together and left the main highway, taking a side road up to the fire area. After leaving the main highway and traveling a short distance they stopped on account of a closed gate, which I believed they noticed to be directly in front of T. H. Shoemaker's house. They left the cars standing and went on across the hills to the fire. Later, I presume about 2:00 a.m., Ranger Bond went down and moved Ranger Beall's car to the point where the fire camp was established, about two miles to east. Toward morning Lloyd Taylor, Charles Pepper and Apoliano Romero were sent to the remaining car to get some supplies. Pepper carried a lantern and was standing at the rear of the car: Taylor was engaged in getting some things from the front seat, when two shots were fired from the vicinity of the Shoemaker house. Pepper was hit in the back of the neck by a sliver from a rock struck by one of the bullets. He dashed out the lantern and they all went for the brush. Taylor afterward coming back and getting what equipment they needed and then returned to the fire.

Mr. White returned to the fire with Mr. Strickland and I remained in Capitan to await the arrival of Mr. French, who showed up about 11:00 p.m. We remained at the hotel until 5:00 a.m. (the 17th) when we pulled out to the fire area in Mr. French's car. We went over the fire lines and interviewed a number of parties. Evidence was insufficient in material information for a government case. We also learned that the guns which had been left in Mr. Dean's car had been taken, this being discovered by Mr. Dean shortly after daylight when he and Lloyd Taylor returned to move his car to the fire camp. About this time it was found that the shots fired the night the fire occurred had struck the car, one entering through the right front curtain, passing out at the rear end through the back cushions: the other hitting the running board and damaging the wiring directly underneath the car. They apparently missed Lloyd Taylor just a few inches above and below his body. There was considerable talk to the effect that the Government should do something. So far as a government case went, justifying immediate action, we were in rather a helpless position.

Mr. French and I decided that in the event complaints were made and search warrant issued for the stolen firearms, the matter could be turned over to the local authorities, which would provide sufficient time for the Government to go ahead in the collection of evidence. We approached Charley Pepper in the matter and he refused to take any action. While we secured the testimony of Romero we did not ask his views in regard to the complaints. Lloyd Taylor, the remaining member, we thought was at the Block Ranch Headquarters. Ranger Bond said he was anxious to recover his rifle, and stated that on his own responsibility he would make complaint and request a search of Shoemaker's premises. We, therefore, left with him and drove to the Block Headquarters, where upon inquiry we learned that Lloyd Taylor was thirty miles away engaged in repair of a windmill and would not likely return for three or four days. We drove on into Carrizozo, reaching there about 6:00 p.m. and talked the matter over with the Justice of the Peace and the Sheriff, Sam Kelsey. Ranger Bond made complaint and a search warrant was issued which Mr. Kelsey said would be served the following day, (the 18th).

As we were about to leave the Sheriff's office and return to Capitan, I received a telephone communication from Mr. A. R. Dean, who stated that he, Lloyd Taylor and Charley Pepper were coming to Carrizozo, that they meant business, and for us to await their arrival. It appears that upon Mr. Dean's return to the fire camp from the fire the damage to his car was pointed out to him. Lloyd Taylor had also unexpectedly returned from the fire. Mr. Dean immediately approached them on the matter of the search warrant with the result that they decided to take action on their own initiative and make the necessary complaints. This was the reason for their hurried trip to Carrizozo. This latter phase was discussed with the Justice of the Peace, A. H. Harvey, and Sheriff Kelsey. Mr. Taylor also conferred with Mr. T. A. Spencer, Manager of the Block Company, with whom I had conversed that afternoon relative to the whole situation. The Block Cattle Company was not a disinterested party, since they had received many threats from Shoemaker, culminating apparently in the shots directed the previous day at their foreman. Complaints were made, and warrant for arrest was secured on the charge of Assault with Deadly Weapons. We returned to Capitan after receiving assurance from Sheriff Kelsey that he and his Deputy would arrive in Capitan around 8:00 a.m. the next morning. Before leaving he stated that the Forest Service was an interested party to this whole affair and that he would want our assistance.

The following morning, March 18th, Mr. Kelsey and his Deputy, Pete Johnson, arrived in Capitan. General plans were discussed and action started on the following basis:

Kelsey and A. R. Dean were to go to the Dixon Ranch on the opposite side of the mountain from where Shoemaker lived. (Dixon was supposed to be on friendly terms with Shoemaker) and this trip was to be made with the object of having Dixon intercede and have Shoemaker give himself up to the officers. Newt Kemp and Lloyd Taylor were to place themselves in the vicinity of the Hipp Ranch about one mile north of the Shoemaker place. Deputy Sheriff Pete Johnson, an ex-service man, with someone I was to select, was to be stationed near the Koprian Ranch. At this time I requested information from Sheriff Kelsey as to the extent of assistance he desired from the Forest Service. I wished to learn also the status of our men before engaging in any program. Kelsey replied, 'I'm deputizing you right now.' I stated that this was satisfactory to me, and he again informed me that so far as any of our other men were concerned he would leave the matter in my hands: that he thought there should be some assignments made for patrol of the country between the fire and the Shoemaker Ranch. In addition to the above, Deputy Sheriff, Billie Sevier, was to be stationed at the Fire Camp and keep familiar with our movements and to give out information as to our whereabouts. This program was outlined with the various men concerned with the definite understanding, however, that the primary objective would be to determine the whereabouts of Shoemaker. Once this was accomplished, and if Dixon failed to give material assistance, Kelsey and Dean were to return to the vicinity and make the arrest. The only conceivable deviation from the general scheme was in the event the opportunity presented itself and could not be overlooked for the immediate arrest of Shoemaker by some other member of the party. In other words, should any of the deputized parties see him or run into him, an arrest was to be made. We immediately proceeded to enter upon our assignments. French and I, with Deputies Sevier ad Johnson, together with Reuben Boone, a Ranger on annual leave from the Manzano visiting his mother in Capitan, drove to the fire camp.

The previous night when we returned from Carrizozo, Ranger Bond proceeded on to the fire, with instructions from French and myself to have Mr. Strickland, then in charge, assign two men at daylight to overlook the Shoemaker Ranch and determine whether or not he was at home. Shortly after we reached the fire camp, Strickland and White came in, stating that they had been watching Shoemaker from a distance, that he was at home.

I told Deputy Sheriff Johnson that if a Forest Officer was to accompany him, I would do it myself, but rather than walk two miles across country to our station near the Koprian ranch, it might be best to take the Government car and drive around, about four or five miles. In the meantime, arrangements had been made that Messrs. French, Strickland and Ranger Boone would patrol the country between the fire line and the Shoemaker ranch, to be on the lookout against additional incendiary fires and at the same time provide for locating Shoemaker should he leave the ranch for the mountains.

As we were getting ready to leave, I noticed White coming from the cook shack, having just finished his breakfast. I asked him if he had any sleep during the night, and he replied that he had. I said, 'How would you like to go along to the Koprian Ranch?' He said, 'All right. fine!' I said, 'Well, come go with us, get in the Ford and drive us around.' We left the camp, White driving, and Deputy Sheriff Johnson at his side. I sat in the truck on an extra tire. Johnson gave me his coat to sit on in which he said his six-shooter was wrapped. I took a rifle which I had borrowed in Capitan and which contained five or six cartridges, but none in the barrel. I laid it down at my side. The other men had their rifles on the front seat. Reaching the highway about a mile and a half away we turned west toward Encinosa. As we rode down a hill, at the bottom of which a side road leads down from the Shoemaker Ranch and passing the Hipp Ranch joins the highway, I looked ahead and saw two horses at the mail box, on one of which was a woman. I do not recall seeing anyone else, but the thought occurred to me that possibly the other horse belonged to Shoemaker. Because of their position and, also, because of mine in the rear of the car, we drove past them I before I noticed the other party, who proved to be Shoemaker. He was standing alongside of his horse, near the butt end of his rifle which was in a scabbard banging on the left side of the saddle, the butt in a forward position. Going about 100 or 150 feet, the car stopped and Johnson got out and started walking back on my left side: my back being toward the front end of the car. My attention was concentrated on Shoemaker to see that he did not make any movement. I cannot say exactly how far Johnson had gotten when Shoemaker reached for his rifle. Johnson whirled and started back. I then noticed that he carried no firearms. He said, 'Look out, he is going to shoot.' My gun was on the bottom of the car at my side. I grabbed it and jumped out on the right hand side and ran around in front of the car. White remained in the seat. Shoemaker started shooting. I fired also. Johnson grabbed his rifle quickly, took his position on his knee in front and at the left hand side of the car. I recall his saying, 'Throw up your hands, Shoemaker.' Johnson was directly in my line of fire at Shoemaker. I could not do much shooting without exposing my entire person, while Johnson remained in a way protected. I did not fire over three shots if that many. Shoemaker was firing rapidly. My time was spent trying to shoot from underneath the car. During this time my attention was distracted from our main purpose twice: once seeing White slip down into the seat and it occurred to me that he was shot. Immediately afterward I decided that he was slipping down out of the way of the bullets; the other time was when he pitched forward on his face in the rut of the road directly in front of the car. I further noticed during that time that the woman on horseback had pulled out to the north side of the road, sitting on her horse and viewing the entire scene. The firing stopped and I saw Shoemaker laying face downward on the ground. Johnson started toward him. I returned to White. Immediately upon going back I saw Shoemaker crawling for his rifle. Johnson hurried back and asked if I had any shells left in my gun. I replied there was, he said, 'Give it to me', which I did.

He ran back and when about half way, Shoemaker was within five or six inches of his rifle and reaching for it. Johnson fired a shot which ended Shoemaker's life. The saddle horse had been shot and was staggering around on the north side of the road. Johnson went over and finished him.

Johnson came back and we gave our attention to White. His face was terribly mutilated, and I saw no hopes for him. Johnson said we would load him in the truck and rush him to Ft. Stanton, 25 miles distant. I replied that there was no use, that the radiator had been shot to pieces and that we could not go over a mile, but for him to remain there and I would rush back to camp and get another car. Before leaving I want over to the woman and asked her to please ride to the Hipp Ranch and tell them to come down. I got out and started running to camp when I met French and Strickland and others who had not left the camp. We got French's car and went to the shooting and found that Johnson had left with White in the mail car which had passed along directly after I left. Newt Kemp was at the scene. We let out one or two parties and Strickland, Boone, French and I drove on. They drove immediately to Ft. Stanton: I got out at Camptan and telephoned District Forester Pooler and asked him to send someone or come himself at once. An inquest was held over Shoemaker's body, at which time the woman's testimony was secured. She proved to be the wife of Mr. Guy Hix, a Block cowpuncher. I was not present at this hearing, but my testimony and that of Mr. Johnson was taken that night before the coroner's jury.

In closing I might add that the guns covered by the search warrant were afterwards found in the Shoemaker house. Further that Kemp and Taylor, stationed at the Hipp place, had seen Shoemaker pass on his way to the mail box, too late to intercept him, but with the agreement that they would meet him on his return."

* * * * * * * * * *

From the Use Book, 1906: "The Secretary of Agriculture has authority to permit, regulate, or prohibit grazing in the forest reserves."

* * * * * * * * * *

Mr. Leon F. Kneipp was appointed Forest Ranger on the Prescott Forest Reserve in 1900. He was transferred to Santa Fe in 1904, and by 1907 was in the Washington Office where he held many important positions and contributed significantly to the development of Forest Service grazing policies and procedures. He had a most distinguished career. The following is quoted directly from a letter written in 1963 by Mr. Kneipp to a friend:

I never was in charge of the Crown King District. What happened was that early in 1902 my salary was raised from $60 to $90 per month, which put me right next to the Supervisor and by tacit consent I became somewhat of a head ranger whose duties extended over all parts of the Reserve. One job was to take the novices out and show them the districts they were to supervise and inculcate in them some comprehension of their duties and how they were to be performed.

Crown King was a hardship job because it was completely isolated from all centers of production or distribution. Horses had to be fed hay and rolled barley which sometimes soared to $30 per ton and $2.75 per 70 lb. sack. There were lots of vacant mining shacks but all other items were high, so a $60 per month Ranger salary, which had to keep a horse as well as the Ranger, had no attraction for men who could get $3.00 per 8 hour day, minus $1 per day for board and $1 per month for the contract doctor. Accordingly, the Rangers changed with considerable frequency.

The District embraced the entire southern end of the Prescott Reserve as it then existed; the Bradshaw Range, extending from Minnehaha Flat easterly toward the town of Mayer. The next gulch south of Crown King had a couple of good-sized mining operations and the Horsethief country had quite a stand of Pine. There was quite a little grazing, to which little attention was given, but mining operations were the principal problems of the Ranger.

The two Rangers who were on the Prescott Reserve when I was appointed in April 1900, both made their headquarters in the town of Prescott and I doubt whether either had ever visited Crown King. The first man I remember thee was named Howd, who had been a desk clerk in a Denver Hotel but had been advised by his doctor to get outside work in a warmer climate than Denver. He was a good man, who knew how to meet and deal with people, had a sense of responsibility, kept a good saddle horse and worked. But when he regained his health he yielded to the allure of a more attractive job.

The other names that occur to me were Newbold, Blackburn, Bushnell, Gaines, Roach, Cokely, et al. The most important was Frank C. W. Pooler, whose first assignment was to Crown King. When I returned early in 1904 from a temporary detail to the Pecos River Reserve in N. M. during the suspension of the Supervisor, I was detailed to accompany Lou Barrett in his inspection of the Prescott Reserve and when we got to Crown King we found Pooler in charge. He had spent some months at the old Grand Canyon hotel, then through Senator Proctor had been offered the Ranger job on the Prescott. I recall, we were standing on a timber sale area when Barrett discovered a rattlesnake right near his foot, so he stamped on its head with his heel and killed it. Evidently it was a new experience for Pooler and he were visibly alarmed. But he was too good a man to stay long at Crown King. Another star was Roscoe G. Willson who was at the King for a year or two. Roach went berserk, killed a man, was sentenced to be hanged, but committed suicide.

Cokely was the most picturesque. He claimed a sponsor who knew where some of the residue of the Government camel herd was still running loose and had hired him to corral them. Meanwhile he was willing to take a job as Ranger. He was a superb horse-breaker and rider, so instead of buying horses he talked local ranches into turning some of their young horses over to him, later to be returned as well broken and gentle, which they were. However, he thought he saw the need for a hotel, so he built one of board and batten type with sackcloth walls between the rooms. He also instituted a hauling service. All of a sudden he disappeared, leaving nothing but debts to mark his memory.

When introduced to Cokely, Lou Barrett said, 'Hello Cokely, remember me?' Cokely looked at him suspiciously, so Barrett added, 'Gut-robber, Troop B.' Then Cokely lost his caution, 'Why Lou Barrett, you such-and-such so-and-so!' He didn't try to fool Barrett or me, but made a frank statement of all his machinations. He and Barrett had soldiered together in the Philippines, chasing Auguinaldo.

In the good old days, whenever a considerable number of virile males was brought together by a new mining development or railroad or reservoir construction a coterie of feminine charm was soon in nearby residence. When asked by what right they were occupying the area, the stock reply was, 'Come out and I'll show you my mining location and discovery shaft.' The case would then be reported to the General Land Office in Washington and the consistent result was instruction to serve a notice for the vacation of the area in ten days. When nothing had happened following such service the G.L.O. was so advised and the usual instruction was to serve another ten-day notice. Some of the places had three or four such notices pasted on the bar mirrors.

When the railroad was constructed to Crown King, Bernice Schwanbeeck established such a place half-way between the King and Mayer. In due time Cokely was ordered to serve another ten-day notice on her. The talk was pretty rough but Cokely could be about as vitriolic as any, so that he didn't mind. However, something happened to upset him. He was riding a half-broken bronco and he was somewhat careless in mounting him, so the horse dumped him headfirst in a rainwater barrel at the corner of the building. According to an eyewitness, he was upended in the water and one of the male habitues declared: 'He got in by himself, let the s.o.b, get out by himself.' But Bernice declared she didn't want a charge of murder added to her other complications and made them haul Cokely out."

* * * * * * * * * *

Mr. Richard H. Hanna (early forest officer in Santa Fe, now a prominent Albuquerque attorney) prepared the following write-up in December 1941:

by Richard H. Hanna

Santa Fe was headquarters for the superintendent of all the forest reserves in New Mexico and Arizona in 1900. I arrived on June 30 of that year after having served a year as ranger on the old Prescott Forest Reserve in Arizona.

In those days, forest officers were not, as a rule, trained men, but were usually selected because of political considerations. In my case, appointment resulted through friendship of my father, the late I. B. Henna, with the late Congressman, "Uncle Joe" Cannon of Illinois, then chairman of the powerful committee on appropriations. Our family home was in Kankakee, Ill.

When I started as ranger, the superintendent of forest reserves in the Southwest was William B. Buntin. In May 1900 he was succeeded by my father, who called me into Santa Fe as he thought I might be of some help to him because of my year's experience as ranger. I stayed six months and then left to go to law school.

The Pecos River Forest Reserve had only recently been established, and was in charge of Supervisor McClure, a Kentuckian. It was mainly undeveloped then. Access was largely by trails. The town of Pecos was old, even then.

The practice was to appoint rangers for the summer, when fire hazard was present, and lay them off in October, except for one or two officers who stayed on through winter. During summer months, as many as 400 men were employed on the Southwestern forest reserves. Among them, as I recall, were Mariano Sans, brother of the Jose E. Sans in Santa Fe who was for so many years Clerk of the Supreme Court; James J. Goutchey, now Federal Building custodian; and John W. Kerr, a very efficient officer who started on the Pecos and later became chief of range management in the Southwestern region.

Fire fighting was the most responsible work of the early forest officers. Forest fires seemed to be unusually prevalent. We used to think people set them purposely. Sheep and cattle growers were fighting a good deal over livestock range, and when one of them was routed from an area, he perhaps would be careless about his fires.

Fires would sometimes burn over large areas and require hundreds of men to fight them. I recall one in the summer of 1900 that extended over 40,000 acres. Then there is the big burn still noticeable on the mountains near Santa Fe, resulting from a fire that started before the forest reserves were created. People in Santa Fe tell me that fire burned for weeks and was just allowed to burn itself out. That was a terrible waste of natural resources.

Little value was attached to forest resources then. Generally, however, when we asked people in the neighborhood of a fire to help us, they would cooperative effectively. Lots of times they would put out a fire before notifying us. Sometimes those who helped us were paid, and sometimes they weren't.

Among our duties was the regulating of grazing and logging, for which permits were issued. The only serious opposition I recall was from contractors undertaking to supply timber needed by the larger mining companies for fuel and mine timbers. They had been accustomed to cut large quantities where they pleased, without payment. When the forest reserves were created, the contractors didn't even attempt to get permits or purchase the timber from the Government, but would help themselves. That kept my father and the rest of us busy.

Rangers of that time built no roads, but worked a lot on trails. For a long time they had no power to make arrests in cases of grazing or logging trespass, although that power was received later on.

They had to be self-reliant, and self-sustaining when they traveled wild forest land and endless mesas, often far from any habitation. My father had a painful and almost tragic experience once, on a field trip from Santa Fe. He was riding by buckboard from Flagstaff to Lee's Ferry. He hobbled his team at night, but they slipped their hobbles and got away. He was still 30 miles from Lee's Ferry, but started there on foot. Father had a bad knee, resulting from a baseball injury in younger days, and after ten miles of walking, the pain in his knee became unbearable.

He crawled the remaining 20 miles on his hands and knees. It was summertime, and he ran out of water, but had a few cans of tomatoes that kept him going. When he finally reached Lee's Ferry at night, the ferry boat was tied up across the river: his shouts failed to arouse the people over there. He emptied his revolver before they heard and came after him.

Father remained superintendent of the reserves until he died in office in January 1905. He had gone up on the Pecos River Forest Reserve and contracted a bad cold which developed into pneumonia.

In the years since I returned to New Mexico to practice law, I have witnesses marked improvement in the efficiency of forest officers and their work. Among other things, I have observed that political considerations do not enter into forest work at the present time, as they did in the early days.

* * * * * * * * * *

Tom Stewart, "Mr. Pecos" to oldtimers in the Forest Service, related the following story to Bob Kelleher in March 1942:

BLAZING TRAIL ON THE PECOS

By Tom Stewart, as told to Bob Kelleher

The notice that arrived by mail at Windsor's ranch on the Upper Pecos River, telling me I was appointed a ranger on the old Pecos River Forest Reserve, was accompanied by a map, some stationery and a letter which ended with the order, "Get busy."

It only took a few hours to learn that the order was superfluous. When I rode to the top of the mountains that day to look at my district, the first thing I saw was smoke from two forest fires. One was on Sapello Creek and the other on Agua Negra. I scratched my head and cussed and decided to handle them one at a time. For help on the Sapello fire I rode fast to Rociada. Ranchers there were already gathering tools when I arrived, so we hit for the Sapello and had the fire controlled by next morning. I left a few men to finish the job.

Without any sleep, I rode to the Agua Negra fire, sized it up, went to Agua Negra placita two miles away, and asked the alcalde (Justice of the Peace) to help me get men. At first he curtly said, "I don't give a d__n if the whole forest burns up." I found out they had known the fire was burning for four or five days. But having learned to speak Spanish fluently, I convinced him that he and other people around there were forest users and it was their duty to help put out the fire. The alcalde gave in, got on his horse, and in no time we had 15 or 20 men. We worked from about 3 p.m. to 3 a.m., and got that fire under control. The alcalde agreed to stay in charge. After that he was the best cooperator I had on my district, to the day of his death.

That first day as a ranger (It was May 1, 1902) had stretched into two days and nights without sleep. My bay horse, "Borrego," had carried me 45 miles. My district covered about 150,000 acres. There were only three other rangers on the Reserve then, and when winter came we were laid off temporarily except for Supervisor McClure and Ranger R. J. Ewing.

Salary was $60 a month (in the months you worked), and out of that you had to furnish two horses, subsistence for yourself and horses, and your own tools for trail building and other work. Men you hired to fight fires had to bring their saws and shovels.

I can distinctly remember receiving a munificent allotment of $20 to build a cabin. I cut the logs by myself, skidded them to the cabin site with a reata tied to my saddle horn, and hired a man for $5 to help lay up the logs. The balance was spent for roofing, nails, etc. Even so, the Supervisor wrote me later, asking how I could have spent all that money on a cabin, and asking for an itemized account.

Forest rangers today have a lot more responsibility, and more fires and other work resulting from heavier use of the forests, and they earn their $150 to $200 a month, but I can't help envying them with their good cabins and barns, pick-up trucks and horse-trailers, and other modern equipment to work with.

Some of the supervisors I worked under during the first years were political appointees, without practical experience. One had been a bandmaster, another a school teacher. The last two I worked under were practical men. One was Don Johnston, now president of a big lumber company down South. The other. L. F. Kneipp, is now a high official in the U. S. Forest Service at Washington, D. C. After the Forest Service was created in 1905 and we went under Civil Service, and with men like Kneipp and Johnston, we commenced to get somewhere.

|

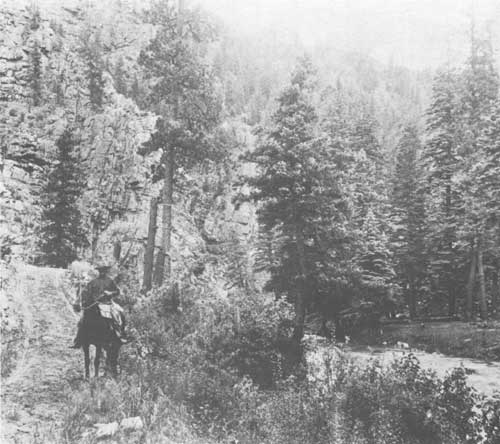

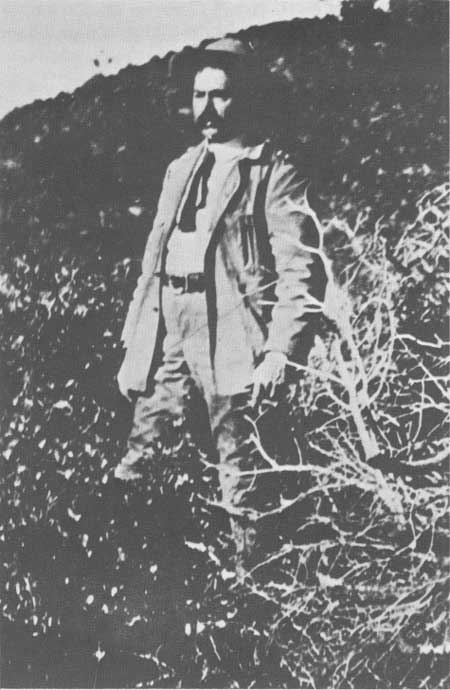

| Figure 12. Ranger Tom Stewart on the road in Pecos Valley in 1903. |

I put in the rest of the summer of 1902 chasing trespassing herds of livestock off the forest, fighting several small fires, trying to establish some sort of boundary on the west side of my district (that side had never been surveyed), and getting acquainted with the district and the people in or near it. There were homesteads and other private land inside the forest, just as there are today.

To know whether logging or grazing trespass was occurring inside the eastern boundary, I finally bought a pocket compass and ran my own line over the rough country. It wouldn't stand in court, but it helped me find and report many trespass cases.

Boundary disputes and political influence kept all but two of the cases from standing up in court. That embarrassed me, and at times I felt discouraged to the extent of giving up the job. But I liked the work and determined to stick.

Figuring I couldn't do anything through the courts, I used an educational plan of my own. Eighty per cent of the people in that locality were Spanish-Americans. I had a knack of making friends of them, so I attended their fiestas and dances, held meetings when the chance allowed, and explained the purpose of the forest reserves. Before long I had the better and influential element seeing the light, and from then on my job was somewhat easier.

That did not stop all the trespass, of course. One case I found out about involved the taking of considerable un-purchased timber from the reserve, by a prominent politician who had a small sawmill on the upper Gallinas River, north of Las Vegas. I'll call him Don Carlos though that isn't his name. He claimed title to the land, but through my Supervisor I obtained General Land Office records, checked section lines on the ground, and determined the timber land involved was inside the forest reserve. I offered Don Carlos a chance to pay the Government for the timber he had out. He got mad and refused, but stopped cutting in the reserve. Despite his influence he was brought to trial in Federal Court at Las Vegas. He finally settled, paying something over $1,000.

One of the worst fires I ever fought came up while the case of Don Carlos was still in court at Las Vegas and I was there as witness. A freighter going through town looked me up and told me a fire had been burning two or three days on the Tres Ritos. That was in early November 1902. The season was dry and windy, and when I rode up to the fire I saw it was spreading rapidly through an area with considerable dead timber on the ground. I got about 50 men and their tools from nearby settlements, made my plan of attack and we got busy in late afternoon. The wind had died down, and by daylight next morning the blaze seemed well under control. But the wind came up strong in the morning and embers from some burning snags flew across the fireline we had cleared. Now we had several small fires to contend with. It went on that way for seven whole days and nights. Under control, then break out again. All the men in the valley were on that fire. We were about done in, when the weather clouded up and in a few hours snow began falling. That ended the danger, and at daylight next morning we hit the trail for our homes.

We were the sorriest looking mess you ever saw. Those seven days and nights I never took off my clothes, and at the end I had few left to take off. The only sleep I had was when I could go no longer: then I would go to camp, wrap up and snooze a few hours, and start fighting fire again. Many of us came away with clothes and shoes half-burned, and all of us blacker then the ace of spades.

After two big fires in 1904, in the Rio Pueblo and Rio LaCasa Districts, I was promoted from third-class ranger to second-class ranger with pay of $75 a month. It wasn't a lot, but a dollar bought more in those days.

As long as rangers had no power to make arrests, our trouble with sheep herders trespassing (grazing their herds on the forest without permits) kept up. Some herders were bad hombres, and the life of a ranger driving them off the forest was not too safe. Whenever it would take several days to drive a band of sheep out to the boundary, I would pitch my camp at night two or three miles from the herders' camp, and just to make sure they wouldn't try sticking a knife in me while I slept, I would sleep several hundred yards away from my camp.

Things changed when rangers finally received arrest power, and I got sweet vengeance. A band of sheep which belonged to somewhat of a politician in Rio Arriba County had been trespassing regularly in the Santa Barbara vicinity in the Forest. It had got to be a joke among the herders because I would chase them off and in a few days I would find them back again. As soon as we got power to make arrests, I sent to Las Vegas for handcuffs and a padlock and ten feet of chain and started making tracks for the Santa Barbara country. Sure enough, I found three herders (two men and a boy) with sheep and no permit. They gave me the horse laugh, but I disclosed the joke was on then this time. I arrested the men and sent the boy home on a burro to get other herders.

Camping for the night, I handcuffed the prisoners to a tree. I felt certain their case would be dismissed in Santa Fe, so I decided they should get their justice on the way. After the new herders arrived and I gave the prisoners breakfast, I handcuffed each of the two, got on my horse and marched them 25 miles on foot to Windsor's ranch. From there we traveled by buckboard and train to Santa Fe. Their case was dismissed but it was soon rumored around that rangers had police powers, and the trespass troubles became less numerous.

Shortly after this, I was promoted to first-class ranger at $90 a month. In 1907 the forest reserve became the Pecos National Forest and I was boosted to deputy supervisor. In 1909 I was promoted to forest supervisor. After five years, I resigned to go into private business in Santa Fe, where my wife and I still live.

Now the old Pecos River Forest Reserve is the Pecos division of the Santa Fe National Forest. The original area of about 300,000 acres has grown to about 625,000 acres as the result of additions made to include land of high value for the protection of watershed and forest resources.

In the old days I wondered if there would be anything left of the forest, what with fires and trespassing going on right and left, but the good Lord and the forest rangers have got things under control. The Lord saw to it that the rugged and remote nature of much of this area made roads impractical except for a few necessary routes, and the men of the U. S. Forest Service are doing the rest.

Boundaries are well marked now, range allotments have been fenced, and grazing and logging under permit seem to be well in hand. The old wagon road along the Pecos River, up into the Forest, has been developed into a good gravel highway for use of fire crews and forest users, but it still stops at Windsor's ranch, now the settlement known as Cowles. Here and there you find a fire lookout tower or a fire telephone line, but the trails we blazed forty years ago are still being used in an improved condition. By and large, the forest is still wilderness.

I am proud to say that I was one of the pioneers and blazed the way for others to follow.

* * * * * * * * * *

Mr. Frank E. Andrews, a pioneer Forest Ranger on the Gila Forest Reserve, later an official in the District Office, was for many years the Supervisor of the Santa Fe National Forest. He prepared the following paper in 1942 while on the Santa Fe:

By Frank E. Andrews, Supervisor

Santa Fe National Forest

New Mexico has right to be proud of having the first forest reserve in the Southwest, one of the first few established in the United States — the Pecos River Forest Reserve, now the Pecos division of the Santa Fe National Forest.

Establishment of this reserve on January 11, 1892 was part of America's answer to the question of dwindling forest resources. It resulted from a movement growing out of decades of agitation throughout the nation. In the last century, logging was universally a "cut out and get out" business, and no thought was given to selective cutting or leaving reserve stand to produce future crops of timber.

The lumberjack had devastated the forests of New England: he had decimated the great forests of the Lake States, and moved on to the virgin forests of the West. An early "voice crying in the wilderness" against desolation of the forests was Dr. Franklin B. Hough, and when Congress established a forestry agency in the Department of Agriculture in 1876. Dr. Hough was appointed Commissioner of Forestry. His work, however, was only investigative; forested lands remained part of the public domain, without special supervision.

To preserve the great beauty of the Yellowstone country in Wyoming, President Harrison established the first forest reserve — the Yellowstone Park Timber Land Reserve — on March 30, 1891. On October 16 of the same year he established the White River Plateau Timber Land Reserve in Colorado. The Pecos River Forest Reserve, established in the following January, was the third in the nation. The Grand Canyon Forest Reserve in Arizona was established in 1893.

|

| Figure 13. Santa Fe Forest Supervisor Frank E. Andrews, August 6, 1932. Photo by S. F. Wilson. |

There was a lag until 1901, when President Theodore Roosevelt, lover of the West and friend of conservation, began to make the dirt fly. Between 1901 and 1909 he set aside over 148,000,000 acres of National Forests, as they are now known.

Forestry work was consolidated by an Act of Congress on February 1, 1905; forest reserves were transferred from the Department of the Interior to the Department of Agriculture and were given the name of national forests; the U.S. Forest Service was launched on its long career.

Watershed and forest values of the Pecos River forest area were recognized from the very first, being cited in the Presidential proclamation which established the first reserve. The areas covered approximately 300,000 acres, mostly in the drainage of the Pecos River.

Various adjustments in boundaries since then to include other land with high watershed and timber values, have increased the area of the Pecos division to approximately 625,000 acres.

It is notable for including the Truchas Peaks, whose elevation of 13,306 feet make them the highest mountains in New Mexico; and the Sangre de Cristo Range, which forms the headwaters of the Pecos River and a portion of headwaters of the Rio Grande and the Red River.

While the timber, grazing and recreational values are all important, the watershed value stands out supreme. Protection of the Pecos division against fire, destructive logging or overgrazing is important to farmers hundreds of miles away in irrigation areas along the lower Pecos River and the Rio Grande.

The Pecos division provides excellent summer range for 3,500 head of cattle and horses, and 4,000 sheep and goats. Livestock in actual use by local residents, not exceeding 10 head, is allowed to graze under free permit.

The great forested mountains have a stand of timber capable of sustaining a cut of 2,000,000 feet of sawtimber a year, or the equivalent in mine props, railroad ties or similar products. In place of the "cut out and get out" logging of early days, timber of commercial value in the National Forests is harvested under close supervision. Away from areas of important scenic or recreational value, mature timber that would decay if left to stand is marked by forest officers and advertised for sale on competitive bids. The Forest Service marking and supervision assure that a reserve stand of young, healthy and fast-growing trees is left to keep the forest productive.

Recreation values of the Pecos division are well known to the people of New Mexico, but if we sometimes take them for granted, visitors drawn to it from many other States show its drawing power. The Pecos area ranks high among the attractions supporting the tourist industry, which has been one of the leading industries of New Mexico.

The great appeal of the Pecos division lies in its high, rugged mountain country, magnificent forests, numerous permanent streams and great scenic beauty. No wonder this is Mecca for the fishermen, the hunter, the camper or hiker, or the "dude" who seeks repose, away from a world at war.

Those who can afford it have the dude ranches to choose from. For people of modest means the Forest Service has developed eight free forest campgrounds. And away from the campgrounds the forest offers myriad natural campsites.

The Pecos forest area has changed little with the passing of years, even though many changes have come about in forest administration. True, here and there is a fire lookout tower, or a Forest Service telephone line. The old wagon road up Pecos Canyon has been improved by the Forest Service into a good motor highway. The forest ranger of today has a sturdy pickup truck for travel where roads are available. But he still needs a trailer behind the truck, to carry his horse and equipment for riding on after the road ends.

The roads do not extend much farther today than they did when Tom Stewart and other pioneers traveled their arduous way. The Pecos highway, in fact, still ends at Cowles. The trails that Stewart and other early rangers blazed have been improved. but they mainly follow the same routes.

There is still practically as much wilderness land here as in the early days. Part of this is in the Pecos Wilderness, formally set aside by the Forest Service in order to perpetuate natural conditions. The wilderness area covers 137,000 acres.

Fifty years of protection against fire and abuse of the resources have given Nature an opportunity to work unhampered in its mission of making the Pecos forest area fruitful for this and coming generations.

* * * * * * * * * *

Mr. Roscoe G. Willson, a pioneer in the Forest Service in the Southwest, tells his story in an interview at his home in Phoenix:

I was born in Minnesota, southwestern Minnesota, in a little town named Granite Falls. When I was two years old my family moved to Grand Forks, North Dakota, in 1881, and in '83 we moved up near the Canadian line on the Great Northern Railroad which had just been built through to Winnepeg, and stopped at a little town named Bathgate. There my father went into the agricultural machinery business and later into the newspaper business. I was raised there, and there in my father's office I learned the printing trade and developed what writing sense I have.

When I was about 15 I got the idea of picking up the farmers' cattle and taking them back into the Pembina Mountains and herding them during the summer. I did that for two succeeding summers. I would take 100 or 150 of the local cattle and would take them out for the summer and herd them up there in the Pembina Mountains and bring them back in the fall. I had three Indian ponies to use in the herding, and I had another man helping me.

In 1898 I went to Minneapolis and spent a year there: worked part time in the Minneapolis Tribune office and part of the time in my uncle's job printing business. Then I went back to Dakota and rented my father's paper for a year. The lease expired on that in late September 1899. I had these horses left over from my former cattle business and I questioned whether to start out on them going to Mexico. I wanted to go south and than to the Latin-American countries. I finally decided the horse would be too slow and too much trouble, so I turned them over to my younger brothers.

I started out on my bicycle and I rode it clear down to Monterey, Mexico. that fall. I reached Monterey in late October 1899. I spent three years in Old Mexico on various jobs, railroad construction, worked on a coffee and rubber plantation and made a side trip into Guatemala. I bought a horse on the Isthmus and made this side trip on the west coast into Guatemala and came back along the top of the mountain range to the place where I had started, and then sold my horse there.

I went to the City of Mexico and while I was there I met a man who was to be Chief Engineer for a Boston firm who had a contract to put in a water and sewage system in the City of Tampico, on the Gulf. And he had with him an engineer who had been with him in Cuba, cleaning up Havana, cleaning it up in a sanitary way, to get rid of mosquitos, and all that. They had come together here to take this job at Tampico for the Mexican Government. Well, we waited there a couple of months and finally the job was ready and we went down to Tampico and I spent the winter there. I had charge . . . well, first I had a gang digging ditches and filling in, and later I had charge of pipe-laying, sewer pipe. We spent the winter there.

Along in the spring we had torn up old cesspools, Spanish cesspools, — we had run into them — and they flooded out down the streets, and caused yellow Fever so badly that by the time we could get our business closed in the spring there were over 3,000 cases of yellow Fever in Tampico. They put on a quarantine. And of course we wanted to get out: the Americans wanted to get out.

It happened that I knew the conductor on the train that ran from Monterey down to Tampico, so I asked him if we walked out about two or three miles from town to a bridge on the Tamesi River, if he would slow the train down and let us on. He said he would, so the three of us walked before daylight and were waiting when the train came along and Old Butler stopped it and we all jumped on and went up to Monterey.

We found that in Monterey they had yellow Fever also. I thought, well, one of the men that I had worked with was an Arizona miner — or had been a miner in Arizona — and he kept talkin' about Arizona all the time. So I said, "Well. we've got to get out of here; I'm goin' to Arizona."

I came up through El Paso and into Albuquerque and I worked on some little jobs there: I worked in the roundhouse at Albuquerque, the railroad roundhouse. And then I came over here and went right to the Crown King Mine. I really came over on a labor ticket to work on building the railroad into Crown King. I worked just one day and started to work the next day and the boss bawled me out and I threw down my pick and walked away and never asked for my money. I caught a man with an extra horse going up to the Crown King Mine and he let me take the horse and go on up there. I spent nearly five years in the Crown King Mine industry, prospecting and mining.

I went into the Forest Service through Frank C. W. Pooler who, as you know, was District Forester up to the time, or shortly prior to the time, of his death. Frank and I were very good friends. His brother and I roomed together in the Tiger Gold Company's warehouse. Frank brought his family out from Vermont. He was a protege of Senator Proctor of Vermont. I had been knocking around in mining and prospecting and I just decided I wasn't getting anywhere and that I'd better get into something that had a future in it. Frank Pooler suggested that I take a job first as Guard, and then take the examination. So I did, and went on in December 1905 — late December 1905 — and in the spring of 1906 I took the examination, ranger examination, and passed it, under Frank C. W. Pooler, out at Thumb Butte.

Frank was detailed back to Washington in a short time, and while he was back there a demand developed for Supervisor material for different newly created Forests. The man in the office with me, who had been left there as Acting Supervisor, Cad Henderer, was sent to the Alamo in New Mexico, and I became Deputy, or Acting Supervisor, on the Prescott for about two or three months. Then an opening came on the Border Forest that they called the Sneeze-Cough Forest. It was composed of the Huachuca, the Tumacacori, and the Baboquivari — and that is where they got the "Sneeze-Cough" name. That was in May of 1907 that I went down there. There is where I met my wife, who had just come down from Canada at the same time.

That was in May 1907 and, by the way, it was there that I first met Will C. Barnes. He came down there to make an inspection of the Forest and among other things I took him out to the old Tumacacori Mission. He became interested, and it was through him that they sent me an engineer to go out and survey ten acres around the Mission to have it withdrawn as a National Monument. That was in 1908, early in 1908.

Then in the fall, somehow or other they got to thinkin' I was quite a fellow. I guess, and they asked me to come back to Washington to cram for a job in the new District office. I think it was actually through Barnes that I was recommended for that. So I went back there in November 1908. Spent a month there, and then came to Albuquerque and helped open the District office, in the old Luna Building.

Ringland was District Forester; they called him "Ring." I was made Assistant Chief of Operations with A. O. Waha. But I was essentially an outdoors man; always had been, knocked around all my life. After having spent the winter there, and wanting to be out. I asked for a Forest, to go back and be stationed on a Forest, and they gave me the Tonto.

In the meantime, in January, I had gone back to Nogales and married, and took my wife to Albuquerque and she spent the winter there with me. We had a home there in Albuquerque, out near the University. In fact, I used to go to the University grounds and play tennis once in a while. Then, as I say, I had asked for a Forest and they gave me the Tonto.

So I went to the Tonto. I think it was in May of 1909. Took over from Johnny Farmer who was Acting Supervisor at the time. It was a little unpleasant there for me at that time because Farmer had been hoping for and expecting to be made Supervisor himself. He was assigned to special range work, and they gave me the supervisorship. I stayed on the Tonto for four years until the spring of 1913.

After four years, in the spring of 1913, I got the idea that I wanted to get into publication, writing, etc. So I came down to Phoenix and bought The Southwestern Stockman and Farmer, and it broke me very quickly. There just wasn't enough circulation; that kind of paper wasn't well enough thought of in the country to be made a success of. So I closed out in late July and went down to Nogales, where we'd been married, and stayed about a month and then got back into the Forest Service.

I was assigned as Deputy Supervisor on the Clearwater, with headquarters at Orofino, Idaho. I spent the winter there. Then in the spring, they needed a man on the Madison Forest and someway both Potter and Barnes recommended me. So I was sent to the Madison in March of 1914 and I stayed there until the fall of 1918 — four years — and then I quit the Forest. I resigned and went into the livestock Commission business and real estate dealing in ranches and cattle and sheep, and also as a wool buyer for a Boston firm.

To get back to that "Cough-Sneeze" group of Forests, the headquarters was at Nogalas. At first there was no one name for the group; the individual Forests were the Huachuca Mountains, the Patagonia Mountains, the Tumacacori Mountains, and the Baboquivari Mountains. I met with the Chamber of Commerce in Nogales and told them that we wanted a name for the Forest: wanted something that applied to the history of the region. Well, one of them suggested Padre Garces, a missionary who had been in that region quite a good deal. I recommended that it be called the Garces National Forest, and that was done. It was called the Garces. This Father Garces was the first missionary to come into the Arizona or Southwest region after Father Kenoe [Kino].

Father Kenoe came to the Arizona region and had little missions at Tumacacori and at Tucson, where the Tucson Mission is now — San Xavier. Garces was the first man after him, to come into Arizona. He was killed over at Yuma by the Indians. He established a couple of missions there and for some reason he aroused antagonism among the Indians and they killed him and a number of Spanish soldiers with him. It was from that missionary that the Forest derived its name.

As Supervisor of those areas of course we had the office to keep open and records to maintain. At first I was alone. There had been one of the rangers — they had temporarily put in rangers — and a man by the name of Rogers was in charge. He had rented a building for an office and he had correspondence and what records there were scattered all around on the floor. I got permission to buy some office equipment; filing cabinets, desks, a typewriter and things like that, and also permission to hire a clerk for half time. He put in half time in the office there with me, but later on the work became so heavy they had to have a permanent man.

Now, my having been in Mexico, you see, for three years, I had learned Spanish. I could speak it quite well and could write what was necessary. That was one reason they assigned me to the border Forest; we had a great deal to do with Spanish-speaking people, Mexicans along the border there. A number of them were in the cattle business on the American side and they were, in general, forest users, wood-cutters, and so on.

* * * * * * * * * *

From the Use Book, 1906: "All timber on forest reserves which can be cut safely and for which there is actual need is for sale."

* * * * * * * * * *

Among our first cases was an immense trespass against one of the big mining companies. They had been cutting thousands of cords of wood. At the time I went there they had long stacks of it, several hundred cords piled up. I was instructed to start trespass proceedings against them to collect damages. It was nice live oak wood that they used in the mill in the boilers. So I started suit against them, and they settled without going to Court.

Another case I had there that was of considerable interest was that of the San Rafael Land Grant which was owned by a brother of Senator Cameron of Pennsylvania. His name was Colen Cameron. The grant called for six square leagues. He interpreted this to mean six leagues square, which made a vast difference. The cattlemen there told me that he had run his fences way outside the grant, taking in a lot of land which now was included within the forest. So it was up to me to do something about it.

I went to Mr. Cameron and got him up to the office and talked it over with him. All I could get out of Cameron was the threat that he would take my job away from me. I told him, "Well, all right, go ahead and get my job, but you're going to have to take your fence down and put it back on the real lines of the grant, which calls for six square leagues, not six leagues square."

Well, he was going to fight it by law. He didn't do anything and finally I went out there and I told him, I said, "Now. Mr. Cameron, if you haven't started to take that fence down by Monday I'm going to come out with the rangers and we're going to take it down." Well, I went out on Monday and I saw he had a crew of men taking the fence down and putting it back on the line. I had a man named Fred Crater who had run the boundary and had marked it, so he was putting his fence back on the true line of the San Rafael grant. That was one of the most interesting things that happened while I was down there on the border.

What was the attitude of the livestock people toward establishment of the forest down there? [Note: Hereafter, questions asked by Mr. Tucker during the interviews are left-justified and underlined to clearly distinguish then from the narrative.]

They were "agin'" it very much. Very much against it, and this Cameron was a very influential man and was head of the State Livestock Board, too.

I would like to drop the Nogales section and go to the Tonto. After I had been on the Tonto a while I found that the cattlemen were not applying for anywhere near the number of cattle that they owned. The rangers I had there were mostly local boys, men, and they knew the situation pretty well. They knew about what each individual had. I tried to raise the permits when it came time to make the grazing applications and I didn't do very well. I couldn't get much increase out of them so I started in and organized cattle associations in each ranger district.

I got the cattlemen a little interested in getting to the meetings and I told them, I said, "Now, you fellows get together among yourselves and decide how many cattle each of you is going to apply for." "Well," they said, "darn it, there's the County tax assessor's records: we don't want to show up too many cattle at tax time." I said, "Of course that's true, but you are going to have to pay the grazing fee on approximately the number of cattle you have here." Well, they were in a great stew over that, having to pay the County tax fee on that basis, but I did manage to get a little raise out of them. I couldn't get them to agree to talk it over among themselves and put down how many each one would apply for. They would look at each other and say, "Hell, I'm not going to tell how many John's got, and he's not going to tell how many I've got." So there was not a great deal of increase, although I did get some. But it was a good try; by organizing those cattle associations.

|

| Figure 14. Pack burrows loaded and ready to go. Tumacacori Mountains, Coronado NF. Photo by R.C. Salton, April 17, 1937. |

I think I can be credited with making the first recommendation for fencing individual ranges or combinations of small owners; fencing areas so the cattle could be handled to better advantage. I recommended that, I think, in my first year on the Tonto. Nothing came of it at that time but I do know now that has been adopted everywhere — to have individual or cooperative ranges fenced. It made the individual allotment, with drift fencing or total fencing or some in combination of the smaller owners; you couldn't make an allotment for everybody. A man with only a hundred head of cattle could't be allowed an exact area; he would have to go in with somebody else.

Sheep were an item on the Tonto. They had a great deal of trouble, too. As you know, there were in the neighborhood of 100,000 sheep that came down from the mountains in the fall and went out onto the desert. They came down here to lamb and to shear, then went back over the trail. My predecessor there, Reed, (I have forgotten his initials) had laid out a sort of trail. He and his rangers had put posts along, laying it out, but they hadn't marked the sides or anything, and hadn't gone into it very thoroughly. One of my first jobs on the Tonto was to go out with the boys and lay out this sheep trail. One reason that it was advisable was that the year before I went there a cowman had killed a sheep man.

There was a great deal of disturbance on the Tonto and the cowboys were constantly threatening the sheep herders. In fact, I remember George Scott taking his sheep down through Johnny Tillson's ranch. A couple of men came out to stop him. Scott had his rifle across his saddle. He just turned his horse sideways so that the rifle would point right at Johnny Tillson's belly and he said: "Now Johnny, you know we don't want to eat anymore of your range than we possibly have to. I'll get the sheep out of here just as quick as we can but we've got to get through here and there's no use in saying anything more." Johnny looked at the rifle pointing at his belly and he said, "All right George, you get out as quick as you can."

We had some trespass cases which nowadays they don't have because everything is clearly marked out and time apportionment on the forest is decided and everything. The Babbitt Brothers were among the biggest sheep owners in Arizona at that time. I don't think they have any today. They leased out a good many of their sheep to other people, some Basques and others. Anyway, one of their outfits had been out on the desert during the winter and came back into the forest near the Superstition Mountains and just spread out and started lambing, you know they break them up into little bunches and get extra herders when they're lambing to take care of each bunch. They put up little tents and put the lambs in with their mothers when they won't recognize each other.

Well, a cattleman came to me right away and said, "Here, they are camped on my range and are eating up my feed and what are you going to do about it?" "Well," I said, "I don't suppose I can move them if they are lambing now, but I'll go down there and try to give them a lesson anyway." So I got Jim Girdner (Jim is dead now) and we went down there. I consulted the United States Attorney and he told me what to do. So Jim and I went down there and we arrested three or four different herders. We didn't take enough men away to leave the sheep neglected, you understand, so that they could not possible bring suit for allowing their sheep to be destroyed. We took the herders down to Phoenix and had a trial in the U. S. Court.

Babbitt Brothers came down there. Dave and George. The first man that was brought in was the foreman, Avilla, a Basque. Judge Knave, I think it was, fined him $400. We had five or six other men under arrest. I was standing at the back with Dave Babbitt and he said, "My God. are you going to soak all those fellows like that?" I said, "Well, I don't know. That's strictly up to the Judge." The others were just common herders, you know, and the Judge just fined them a dollar and gave them a good talking to. He told them they must pay the dollar and said that their desires couldn't come ahead of Government regulations; that they couldn't do as they pleased on the National Forest. The Babbitt's were greatly relieved when they found that the other fellows were fined only a dollar each.

I remember in 1910 we had a fire up under the Mogollon Rim above Pleasant Valley. It was at the time that Halley's Comet was showing clear in the sky. I went up there from Roosevelt and got the boys. We got some cowboys too. It was mostly a ground fire. We never had any top fires in there. There wasn't heavy enough timber that could be ignited and carried by the wind. Fires were practically all in the duff, you know. I remember fighting the fire there with the boys. They were keeping it under control. I took an old quilt and rolled up and laid down there. I looked up and could see this Halley's Comet just as plain; it was streaking the whole sky.

While I was on the Tonto the forest headquarters was at Roosevelt Dam. We had free electricity, free water, and free ice. We had an icebox. The Forest Service office was then in the Reclamation Service Building, which had been built while Roosevelt Dam was being constructed. After the dam was completed, this big office building was practically vacant, so we took over what room we needed. After I left there, they built a couple of extra houses. They had the house that my wife and I lived in, then they built a couple more, one for the local ranger and another with two rooms for the girl clerks. They had two girl clerks. Charley Jennings was the Deputy Supervisor and he later became Forest Supervisor on the Sitgreaves.

There was a spirit among the early-day Forest Service boys; all they thought about was the Forest Service. You could get three or four of us together and all we could talk about was the Service. Free uses and special uses, how to handle the cattle, grazing permits, how to treat the permittees, and all that. I don't know whether that same feeling exists today as warmly as it did in those earlier days.

I can recall an incident that occurred while I was at Nogales. Gifford Pinchot came out to Tucson. The cattlemen had written in to him complaining about Forest Service conditions along the border on the border Forests and on the Coronado, which headquartered at Tucson. No, the headquarters was in Benson at that time. So Pinchot arranged to come out to Tucson and meet the cattlemen. They had a banquet in the Santa Rita Hotel there — I've forgotten the exact date — but I think it was in the fall of 1908. The cattlemen came from all over and the Supervisors were called in, too. As the cattlemen brought up questions that Pinchot couldn't answer, he referred them to local Supervisors.

We had one oldtimer down there, a good old fellow but kind of hot-headed, George Atkinson. They called him the dynamiter. George got up and made a big ruckus about the Forest Service letting other people's cattle come in and use the water that he had developed. Mr. Pinchot turned to me and asked me what I knew about it, and I said, "Well, I don't know too much about it except that it seems to be the common practice in the country there; the cattle all mix, you can't keep them away from one watering place any more than another when they are mixed." "Well," he said, "Mr. Atkinson, does that answer your question?" And Mr. Atkinson said, "Hell no, I want those cattle kept away from my water." He kind of dropped it then and went on to something else, but he was a very fine man, Pinchot was, I liked him immensely. He was a completely dedicated man.

By the way, I met Teddy Roosevelt back in Washington and also when he came out to dedicate the dam at Roosevelt. He came into my office while he was there. That was on March 18, 1911. That's when the dam was dedicated and we were there. I lived there during the last two years of the work on the dam.

One time three of us went up into the Huachuca Mountains and the boys had forgotten to pack most of the food. All we had was a sack of flour and some salt. We stopped to camp in Ramsey Canyon. We made some dough gobs with this flour. Well, they were just terrible. They clung to your hand and they clung to your teeth and you could hardly eat them.

The next morning we woke up and our beds were covered with snow. One of the boys — I think it was Arthur Moody — said, "Well, I'm going to make some real biscuits." He went over to the sack of flour and put the water in and put the salt in and stirred them up. He took a couple of tin pans, tin dishes, you know, and put the two of them together and put the biscuits in them and put two more tins inverted on the top and put them on the coals and heaped more coals on the top. He said, "Now we will have some biscuits." In about 10 minutes he took a stick and poked the top off and there were the prettiest biscuits you ever saw. He didn't have anything to make them rise, nothing except salt you know. We joshed the other fellow about his gummy biscuits that nobody could chew.

When we were on the Border we used to contact the U. S. Customs Service people there, the Border Riders, as we called them. We were in contact with them all of the time, back and forth: not only myself, but the rangers as well. If we were on the Border we would often stop and stay overnight with these Border Riders. At that time they just had horses.

I remember one night I started out from Nogales late. I was going to Oro Blanco about 25 miles west. I didn't get away from town until close to dark but I didn't mind riding in the night. I started out and came to what was called Bear Valley, about 20 miles from town. It was getting pretty well into the night by that time. There was a spring there and an old adobe house they called the smugglers' haven. As I came down the hill, which was very steep, I got off the horse and led him. I was kicking rocks and making quite a noise. When we got down there I took the bridle off his head and the bit out of his mouth and hung it over his head and let the horse drink, and I got myself a drink too. As I got up I saw something white coming out from under a walnut tree there up off the ground about four feet high perfectly white, and it kept coming toward me. I thought, well that's the nearest thing to a ghost that I ever saw. I started wiggling sideways up off the ground. I couldn't imagine what in the Devil it was. My horse snorted and pulled back and knocked rocks all over the place.

Then I heard the click of a gun and I said. "Hi, who is that?" And a man said, "Who are you?" I said, "I am Willson from the Forest Service: who are you?" He said, "I'm George Sears, a line rider camping here for the night." I said, "Damn you George, you scared the hell out of me! I'm going to come over and bunk with you for the night." "All right," he said, "come right up." So I stayed all night and he fixed up a breakfast in the morning, and I went on. Oh, we had a lot of incidents like that.

I was one of the pioneers in the Forest Service, going in in late 1905 and I can emphasize that everybody in the Service was taken up entirely with it. They devoted their whole life to the Forest Service and to Forest Service work. I never saw such an enthusiastic bunch of men as the men in the early-day Forest Service. Later on I think it became more matter of fact to the personnel, as it became more established. But everything was new to us.

* * * * * * * * * *

Mr. Henry L. Benham, who started work for the Forest Service on the Black Mesa National Forest, relates some of his early-day experiences, in an interview at his home in Williams, Arizona.

Mr. Benham, when did you start on your ranger job?

I went to work in Pinedale, Arizona, in November 1907. I went in as a Forest Guard, and until I took the examination I was classified as a Forest Guard. I took my examination — I forget just when it was, but I think it was in 1908, in Denver. I had been riding for Will C. Barnes until he sold out and moved away from New Mexico. Mr. Barnes went into the Forest Service and he wrote and asked me why I didn't apply for a job. I did and was sent to Pinedale.

I went out from Holbrook to Snowflake on a buckboard that carried the mail. Had to sit on a trunk in the back and it was a pretty dusty ride. The next day I caught the side route to Pinedale. From Holbrook it was the Holbrook to Fort Apache mail route. They carried passengers too once in a while, when they had room.

A. J. McCool was the Supervisor. They sent him down to open up the San Francisco Peaks Forest Reserve. They sent him to Show Low, but he stayed in Pinedale a couple of weeks before heading for his headquarters at Show Low. I had a district that ran from about 13 miles east of Pinedale, west to Heber, and over into the Chevelon and Wildcat Canyons, and down to the Mogollon Rim. I spent the bigger part of the winter looking after the cattle and sheep, going up and down the trail trying to get control of the grazing.

Now, before we get into that, tell us about the examination: how they handled Forest Ranger examinations then.

Well, we had a little written test to find out what you knew about surveying, if anything, and mining. It wasn't too big a test. What they wanted to know mostly was whether a man was able to ride the range and see that the cowmen and the sheep men stayed on their own allotments. They gave you a paper about the duties of a Forest Ranger, and it was a pretty good description. You had to ride and be able to take care of yourself out in the open in all kinds of weather.

How did they test for that?

After they gave me the written test I had to saddle a horse and ride out a certain distance in a walk, then trot over to another station that they had set up there, and then lope your horse back to the starting point. After punching cows for six years, didn't have any trouble qualifying.

Then they tested to see what you knew about handling a gun, so you didn't go out and shoot somebody with it the first day. And you had to put a pack on a horse, a bunch of cooking utensils, bedding, bedrolls, and a tarp to cover it with, and a rope to tie it on with. I'd learned all that before I went into the Forest Service. I didn't have much trouble. Some of the boys had an awful time, winding their ropes under the horse and around his belly.

What kind of men were taking the examination in those days?

Well, in this class in Denver they were mostly right out of college. I remember one boy didn't get through the written examination before he walked out. In the olden days they wanted cowpunchers, or men who were used to being out of doors and knew they could get along in the open. Another kind of job they had was to locate section points. There were few maps. When I came to Williams there was a very poor map of this Forest here. Lloyd Sevier was the Ranger with me, and he and I spent days and days just riding around through the Forest to see if everything was going all right.

If we saw a monument we'd check to see if there was a circle on it and if there was we'd follow it up until we found section points and then we'd set up the old monument if it was torn down, and make a rough sketch of it, and some of our sketches were pretty rough, sure enough. And then we'd locate springs with water in them and find a section corner and step it off and see what direction it was. We'd take a compass and sight across to the spring and step it off and see how far it was from that section point, and put that down on our Proclamation maps.

When you came back from Denver, did you come back to Pinedale?

No, I came in to Flagstaff and I ran into a fire there the first thing. It was a fire up in Schultz Pass on San Francisco Peak, and Acting Supervisor Willard Drake asked me if I could find that fire. I told him I thought I could. So he said, "Go over to the livery stable and get a horse, go to the fire and report to Ranger Tom Dusick." That was about the first of June 1909. So I left and rode up into Schultz Pass and found the fire, and I stayed there the rest of that afternoon and all night, and got back to Flagstaff the next afternoon. I figured I'd spent about 28 hours or better on that fire.

I went to Schultz Pass and after I got there the fire had broken out, and I rode down to Fritch to the railroad. The foreman and a laborer came up with a wagon and team. I worked those Mexican section hands all night on the fire, and the next morning they had to go back to work on the railroad. In the meantime we had got the fire pretty well under control.

As I understand it, you were the first ranger on the old Tusayan?

I was one of them. There was Lloyd Sevier, Bert Stratton, Ed Kirby, Lou Banger at Ash Fork, the Supervisor, and myself. Sevier and I were here, Stratton at Chalender, and Ben Doak was in Ash Fork.

Did you have a regular, permanent station?