|

Logging Railroads of the Lincoln National Forest, New Mexico

|

|

THE LOGGING COMPANIES

Alamogordo Lumber Company

The Alamogordo Lumber Company (ALCo) was organized by the same interests as the EP&NE and the A&SM railroads for the purpose of operating a lumbering industry in the Sacramento Mountains. Incorporation took place on May 19, 1898, in New Jersey. The major investors were the same as for the two railroads, and F. L. Peck of Scranton, Pennsylvania, was the first president of the company. The firm's capital was initially set at $200,000, later increased to $400,000 (Neal 1966:53; N. M. Corp. Comm. 1912).

Arrangements between the ALCo and the A&SM were defined in a lengthy agreement signed on December 6, 1898, by F. L. Peck and C. O. Simpson, respectively presidents of the two corporations. The terms of the agreement included the following provisions:

I. Lumber Company would build and equip a sawmill capable of sawing 50,000 board feet per day (11 hours).

II. Lumber Company was to supply energy, capital and labor to keep sawmill running.

III. Lumber Company would deliver all timber accessible to railroad lines which went to mill in Alamogordo.

IV. Lumber Company would build necessary laterals and tramways to deliver maximum amount of logs to railroad.

V. Lumber Company would provide suitable and sufficient number of cars (110).

VI. Railroad Company would have right to build line over Lumber Company land.

VII. Railroad Company would construct and provide a railroad from mill to summit of Sacramento Mountains and would extend it, if necessary, for supplies of timber. Would not build extensions over any route of over 5 percent maximum grade; or which required expensive bridges, fills, cuts, tunnels or other structures.

VIII. Lumber Company had right to acquire from Railroad Company necessary connections between its laterals and tramways and the railroad lines. All switches were to be under Railroad supervision and expense.

IX. Railroad agreed to receive all logs delivered to it and loaded safely, and to transport to mill at Alamogordo. Railroad would return empty cars to points designated by Lumber Company. Log cars had to have braking appliances as required by Railroad. Railroad was to pay no mileage or rental on cars.

X. Charges:

1. Logs — $2.00 per 1000 board feet

2. Shingles, laths, etc. — fair rate according to selling price of merchandise

3. Materials and supplies used by Lumber Company in mountains and at mills — $1.00 per ton in carload lots, 24,000 pounds minimum.

XI. Smaller lots for materials going rate — 50 percent rebate given.

XII. Statements to be sent 10th day of month.

XIII. Disputes to be arbitrated by chosen board (quoted in Neal 1966:53, 54).

Several significant elements are not specifically brought out in this agreement. One was that the ALCo owned a large amount of timber Land in the mountains. During August 1901, the ALCo filed deeds for 26,080 acres of timberland, in 489 parcels purchased at $3.00 per acre, or a net cost of $78,242 (Alamogordo News 1901e). This land had been public land, held in trust by the Territory of New Mexico. As much as 30,000 additional acres was acquired using government land scrip. Another hidden element in the agreement was the expense and difficulty of constructing and operating the A&SM to the summit of the mountains, as it was quaintly termed. This clause resulted in the spectacular climb to Cloudcroft, but it also resulted in a railroad that was forever terrifically costly to operate (New Mexican 1907).

During 1899 the ALCo build up its own plant. A mill site was selected in Alamogordo, on the west side of the railroad yards. On October 5, the new sawmill began operation. The mill was equipped with the usual collection of support shops and outbuildings, including a two-story 40 room boarding house (Alamogordo News 1899d, 1901f).

Out in the woods, the lumber company was loading logs at Toboggan, where a short spur may have extended into the timber. A steam loader was on hand later in 1899. Two Shay gear-driven logging locomotives arrived during 1899, followed by a third at the beginning of 1900. During June and July 1899, ALCo constructed its first logging spur out of Toboggan. It appears likely that this spur line up into Bailey's Canyon became the first two miles or so of the Cloudcroft extension of the A&SM a few months later (Alamogordo News 1899a, 1899b). At the point where the A&SM line curved back across Bailey's Canyon, two ALCo spurs continued up the increasingly steep canyon. There was also a logging camp built in this vicinity. The shorter of the spurs ran a third of mile or so to the north, while the other extended a mile or more to the northeast to upper La Luz Canyon. There is a possibility that this line ran further into La Luz Canyon. Around 1920, long after ALCo had departed, J. A. Work had a sawmill in Bailey's Canyon near the railroad (Alamogordo News 1899a).

As soon as the A&SM reached the head of Cox Canyon in June 1900, work began on the next set of logging spurs. One line took off eastward down Pumphouse (Hawkins) Canyon and another ran southeast down Cox Canyon (Neal 1966:55) (Figure 8).

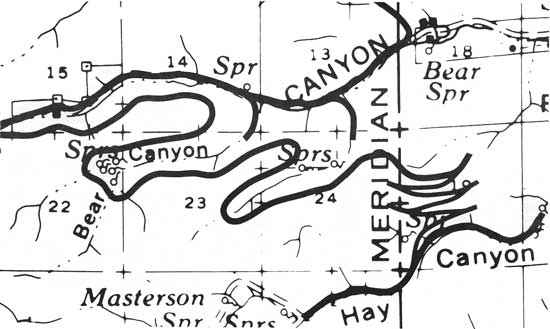

|

| Figure 8. Railroads (shown by heavy black lines) in the vicinity of Cloudcroft. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The line down Pumphouse Canyon dropped downgrade to James Canyon. Here a logging camp was built, including a four-track engine-house and a crude elevated water tank (Figure 9). Spur lines continued up and down James Canyon. The western spur extended about 1-1/2 miles. The eastern line ran 1-1/2 miles and split with spurs going into Orr Canyon and Young Canyon. The Cox Canyon line extended about 2 miles from the junction with the A&SM, and included a short spur up Pierce Canyon (Alamogordo News 1901a, 1901d).

|

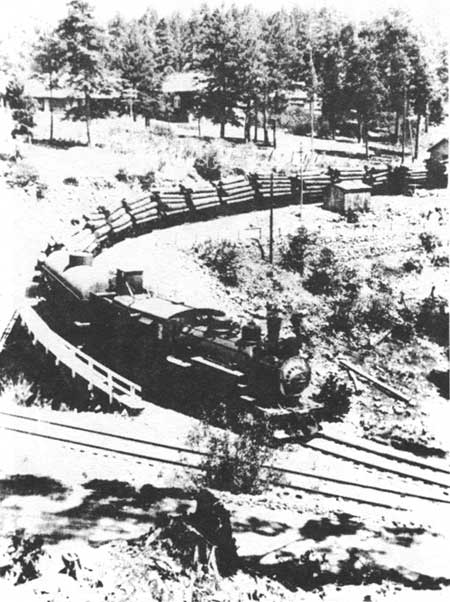

| Figure 9. Water tank and engine house at the Alamogordo Lumber Company camp in James Canyon, ca. 1900-1902. All four of the lumber company's Shay geared locomotives may be seen. (By Green Edward Miller. Museum of New Mexico) |

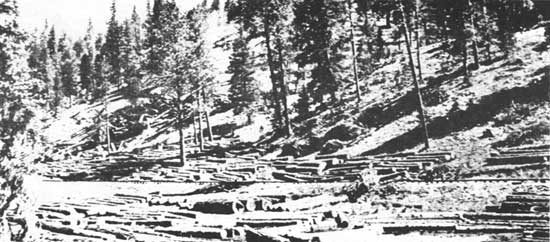

In these early years, logging was done with handsaws and animal hauling using horses and mules. Logs were skidded to landings along the railroad spurs, where they were loaded by steam loaders on the log cars (Figure 10). Usually the logs would be accumulated until an entire trainload could be loaded (Figure 11). Typically, the ALCo Shay locomotives worked on the logging spurs, and, when necessary, up and down the A&SM as well. The A&SM locomotives tended to stay on their own rails, because of their more rigid construction and their greater weight.

|

| Figure 10. Alamogordo Lumber company steam log loader at work ca. 1889. (By Green Edward Miller. Museum of New Mexico) |

|

| Figure 11. Alamogordo Lumber Company Shay geared locomotive and train loading logs. n.d. (By Green Edward Miller. Museum of New Mexico collection) |

Later in 1900, work began on a box plant at the Alamogordo mill site. It was to be 44' x 88', two stories in height, and would employ 25 to 35 men (Alamogordo News 1900h).

The following year continued the pattern of activity and prosperity. Operations had settled into something of a routine. The railroad handled 850 cars of logs during May 1901. This represented two trains a day, including Sundays, throughout the month. In terms of running the railroad, it meant that locomotives, cars, and crews had to be found for two empty log trips and the passenger train, as well as for two loaded trips. All of the 110 log cars had to be kept in serviceable condition, for that number was none too many for the level of traffic.

In December 1901, ALCo ordered $15,000 worth of equipment for a wood preserving plant. By June 1902 the plant was in operation, producing treated ties and timbers. Over the years to come, this was to prove one of the most useful and productive investment the company made (Alamogordo News 1901c, 1901g, 1902b).

By this time, the work of cutting trees and skidding them down to the rail spurs was being done by a contractor, the New Mexico Tie and Timber Company. Incorporated in Colorado on July 5, 1900, this enterprise included among its directors William Ashton Hawkins, who was Charles Eddy's very capable attorney. Another director was George Laws, an experienced lumberman from the Chains and Canadian River districts of northern New Mexico (Alamogordo News 1900g). This company used horses for logging, as well as a lot of manpower. Other services provided to ALCo included building railroad spurs and operating the log trains (Ibid. 1900d, 1901b, 1902a, 1905).

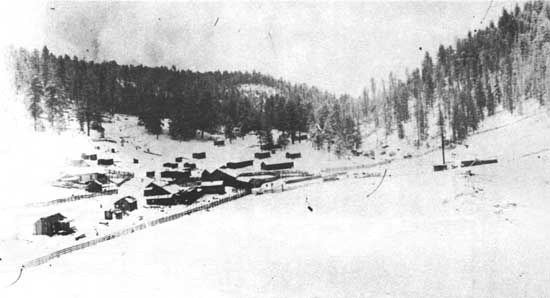

In May 1903 the A&SM was completed to Russia at the head of Russia Canyon, where a logging spur connected with the A&SM. It switched back down the canyon and headed east. About a mile east of the junction the logging camp of Russia was built. It ultimately consisted of about a hundred wooden cabins and a few larger buildings (Figure 12). Included were the New Mexico Tie & Timber Company commissary, a railroad shop, a "roundhouse" for the four Shays, post office, school house and two cook shacks with mess rooms—one for the loggers and the other for the railroaders (New Mexican 1904).

|

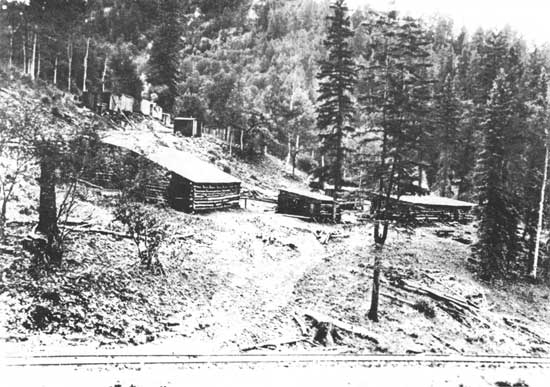

| Figure 12. Alamogordo Lumber Company logging camp, probably in Russia Canyon, April 21, 1907. (By Green Edward Miller. Museum of New Mexico collection) |

By the end of 1903, the Logging railroad and camp in James Canyon had been dismantled, and about eight miles of track laid in Russia Canyon. The rails in Cox Canyon had been left in place, and in August 1906, a logging outfit was moved back into the canyon. A new camp was established in Cox Canyon near the "old Traversey mill site" (Alamogordo News 1903a, 1906b) (Figure 13).

|

| Figure 13. The A&SM ended at Russia Canyon. Logging lines of the ALCo extended down Cox, Russia, and Penasco Canyons. (click on image for a PDF version) |

The ALCo had its successes and its failures. It had a ready customer in its affiliated railroads, both during the construction period and later as ties and timbers needed replacement. Other customers appeared to be more difficult to please. The Arizona mines, especially those at Bisbee and Morenci, were obvious customers for pine timbers, yet that trade was slow to develop. There is an indication of some early problems with improper grading, but by 1903 the mines were buying timbers in million board foot lots. Late in 1903 the ALCo operations were enumerated at eight to eleven miles of logging railroad, four 65-ton Shay geared locomotives, a payroll of 650 men, and eight to ten million board feet of timber in stock (Alamogordo News 1903b).

The desired well ordered routine was punctuated at frequent intervals by the problems of railroading in raw mountain country. The new roadbed softened with the summer rains, resulting in delays for land slides and derailments. Once in a while whole lengths of track would slide down the slope, stopping trains for a day or longer. Accidents involving trains or log loaders were frequent. Simple derailments were so common as to cause little comment, but runaways did enough damage to merit more detailed reporting.

On April 30, 1904, Shay locomotive number 4 blew up at Russia camp. The boiler flew through the air to land on the bunkhouse nearby. Fortunately the loggers as well as the train crew were at dinner in the dining hall next door, and no one was injured. The locomotive, however, was not so lucky and was junked (Alamogordo News 1904).

On a few occasions, such as in May 1905, railroad problems resulted in a shutdown of the Alamogordo mill due to a shortage of logs. This time it was a lack of locomotives that was the cause. Later in the year heavy rainfall was the cause of a similar shutdown. In the best of times it required constant effort to cut enough logs to keep the mill going (Alamogordo News 1903b, 1907b; New Mexican 1905a, 1905b).

But the problems of railroad logging were minor compared to the catastrophe that struck the ALCo in 1907. The situation began to take shape in May 1906 when one E. P. Holcombe, a special agent of the Department of the Interior, appeared at the Federal Building in Santa Fe to open an office. Holcombe was about to begin an investigation into alleged irregularities and fraud in the sale of timber and coal lands in the New Mexico Territory. In particular, he was interested in sales of public lands held in trust by the Territory of New Mexico which had been sold to the ALCo, the American Lumber Company, and the Pennsylvania Development Company (Alamogordo News 1906a). The lengthy investigation resulted in the filing of a lawsuit by the United States government in early February 1907 against the Alamogordo Lumber Company alleging the fraudulent purchase of timberlands from the Territory of New Mexico. The basis of the charge was that the company had purchased the parcels of land in the names of individuals in its employ in violation of the requirements of the law.

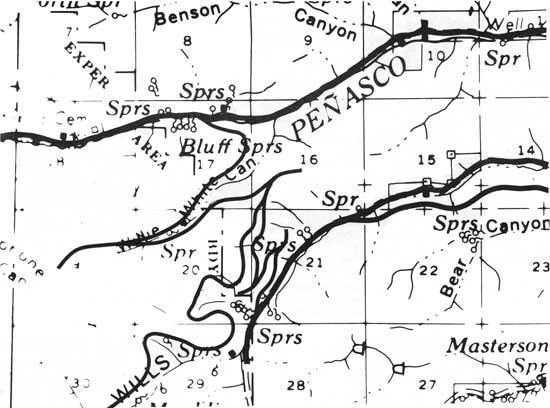

One of the immediate results of the suit was the issuing of an injunction prohibiting the ALCo from logging on the lands in question. Although the company had as much as 30,000 acres of timber with a clear title, they were evidently not prepared to log immediately. Logging continued along Russia Canyon until the end of 1907. During the fall, the company began building an eight mile railroad down Penasco Canyon. The route ran directly south from Russia station to the head of the canyon, then continued down the canyon. If completed, the railroad would have ended in the vicinity of Marcia. Only four miles of the Penasco line were completed before the company ran out of money. Construction ended near Johnson Canyon (Alamogordo News 1907f, 1908).

The Alamogordo mill shut down in late 1907 and all logging operations ceased (Alamogordo News 1907d, 1907e, 1911, 1913). During April 1909 the railroad tracks in Russia Canyon were removed, and the steel was salvaged. Immediately afterward, the tracks in Cox Canyon were taken up, leaving only the stub of the Penasco line (Alamogordo News 1909).

During the next few years it appears that only occasional logging took place along the ALCo railroads. Odd shipments of poles and ties were cut by small operators and shipped out by rail. During 1909 and 1910 much of the sawmill machinery was sold off, including the main steam engines which were nearly new (Alamogordo News 1908, 1910a, 1911). During 1910 the management of Phelps Dodge and Company, which had picked up the land and timber interests along with the railroad, announced their intentions to extend the logging railroad down the Penasco Canyon and to build a new sawmill in the woods, if and when the Federal suits were dismissed. The mill site was to be in Will's Canyon in the high timber country (Ibid. 1910b, 1910c, 1910a).

Around the end of 1911, rumors of the dismissal of the suits began to be heard, but little happened until 1913. Following statehood in 1912, the state courts assumed jurisdiction of the Federal suits and promptly dismissed them when they came up for action. By this time, of course, the business of the ALCo had become thoroughly disorganized and the property had deteriorated substantially. The company was no longer competitive, even for close customers in Arizona. By this time, most of the southwest mines had become accustomed to using timber from the northwest shipped via raft and rail (Alamogordo News 1913).

On the other hand, the EP&SW railroad, under the same ownership as the lumber company, remained a good customer for treated timber products from the creosoting plant at Alamogordo. The ties and bridge timbers were cut by small private mills scattered through the mountains, and hauled by wagon or rail to the treating plant. The plant was kept particularly busy during 1912 supplying new ties for the Tucson extension of the EP&SW (Alamogordo News 1912a, 1912b).

There is no doubt that the ALCo was seriously damaged by the lawsuits. In spite of coming to nothing in the end, the suits had denied the company access to its most useful timber for an extended period, with the accompanying loss of markets. In order to bring the situation back to normal, a new company was formed and the business built anew.

Sacramento Mountain Lumber Company

Incorporated in Arizona on August 7, 1916, the Sacramento Mountain Lumber Company (SMLCo) took over the half-dismantled mill and part of the timber holdings of the Alamogordo Lumber Company. The latter firm continued to function, but only as a landowner and holder of timber rights on a mixture of National Forest and state lands. The logging railroads, locomotives and Loaders went to the new company as well (N. M. Corp. Comm. 1916) (Figure 14).

|

| Figure 14. Sacramento Mountain Lumbar Co. camp at Hudman's, 1.8 miles north of Russia. May 1919. (By Quincy Randles. USDA Forest Service photo 162831) |

By this time the market for ties and timbers was recovering. The SMLCo decided to replace the old horse and mule logging method with heavy machinery. They chose the Lidgerwood overhead logging system. Typically the Lidgerwood system utilized a multi-drum steam skidder with a steel boom and a system of overhead cables extending out from the skidder to a series of tall trees. A skidding carriage riding on the cables hauled the logs in to the skidder, which then used some additional cables and booms to load the log cars. The skidder itself was ponderous but movable by rail when it had finished logging the surrounding area (Bryant 1923: 215-232). SMLCo owned one Lidgerwood skidder with a 74 foot steel tower, two without towers (presumably using spar trees at the skidder sites), and one Clyde skidder (The Timberman 1927). In practice the skidders were located at points along ridge lines or high on the side slopes of large canyons. Logs were gathered in piles near the skidders for loading (Bryant 1923:215-232).

New SMLCo railroads were built starting in late 1916 from the end of the ALCo line in Penasco Canyon, near the upper end of Benson Ridge. One line followed the canyon slope high on the west side of Penasco Canyon. A longer line wandered out of Benson Ridge, overlooking several heavily wooded valleys. This line served a logging camp and then split to follow ridges along both sides of Benson Canyon (Figures 15 and 16).

|

| Figure 15. Sacramento Mountain Lumber Co. railroad through Douglas fir cutting on Benson Ridge. July 1921. (By. S. Strickland. USDA Forest Service photo 163264) |

|

| Figure 16. Sacramento Mountain Lumber Co. logging railroads south of Russia. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Rail operations remained much as before with the Shay locomotives gathering up short strings of log cars and hauling them up the steep climb to Russia. From the terminal, full trains were taken by the EP&SW down the mountain to Alamogordo (Weekly Cloudcrofter 1917a, 1917b).

The SMLCo was never able to achieve a sustained operation. Troubles seemed to dog the company in every way possible. The year 1917 saw fires destroy timber and railroad equipment. The newest of the Shay locomotives was wrecked and out of service for several months. During the summer the company shut down completely. The published reason was "threatened labor troubles" but there was little sign of problems in the camps. The company spent a leisurely winter overhauling its equipment and resumed operations early in 1918. The following year was a better one and the company announced in August 1918 that it would add a box factory to its sawmill and planing mill in Alamogordo (New Mexican 1918).

The prosperity brought by regular operation in the wartime market was not to last. In January 1919 the sawmill was destroyed by fire. And, at nearly the same time, the boom markets ended. The entire operation was shut down at this time. The company's interest in further development of the property ended, and in July 1920 the business was sold to the Southwest Lumber Company (Neal 1966:61; Alamogordo News 1919).

Southwest Lumber Company

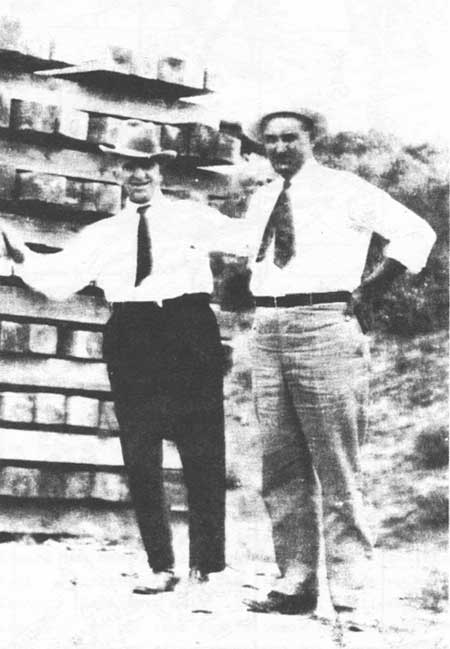

The next outfit to try its hand at lumbering in the Sacramentos was the Southwest Lumber Company (SWLCo), a New Mexico corporation organized by Louis Carr (Figure 17). Carr was an experienced lumberman from North Carolina, who brought with him the ample financial backing needed for such an enterprise. The SWLCo was initially capitalized at $300,000, this figure was increased to $400,000 during 1921, and finally to $600,000 in mid-1922 (N. M. Corp. Comm. 1921, 1922). With Carr in the SWLCo were S. M. Wolfe, John T. Logan and C. W. German.

|

| Figure 17. Louis Carr (L.), owner of Southwest Lumber Company and Lincoln N.F. Supervisor Arthur standing by stacks of untreated cross ties at Alamogordo. July 2, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233470) |

In July 1920, SWLCo bought out the interests of the Sacramento Mountain Lumber Company. It took until the end of the year to get things moving once more. At that time it was reported that the debris of the burned sawmill had been cleared and new machinery was being installed. The capacity of the mill pond was to be doubled, which was one way to smooth out the erratic delivery of logs over the railroad. It was planned that logging and milling would begin sometime during February 1921.

The EP&SW was overhauling its log cars, and a crew of 15 or 20 men was repairing and extending the logging railroad trackage (Alamogordo News 1921b, 1922a, 1922b). Operations began as planned and the output of SWLCo increased steadily through the year. Beginning in February 1921 SWLCo commenced logging as planned using the heavy overhead logging equipment obtained from SMLCo. Logging progressed along Benson Canyon, with the rails being removed when logging was completed in late 1922. This was the last use of the skidders and overhead cables (Alamogordo News 1921e, 1922a). Subsequent logging would utilize the newly practical Caterpillar tractor in ever increasing numbers.

During 1921 SWLCo began a new railroad down Penasco Canyon from the end of track near Benson Ridge. The first two miles or so of this line were built over the deteriorating roadbed of the old ALCo line started in 1907 (Alamogordo News 1921d). To supplement the well worn Shays, a new Shay locomotive was purchased during 1921. October 1921 saw a production of one million board feet, with a ten percent increase predicted for November. This pace continued into 1922, and was apparently based on the general recovery of the Arizona copper industry following the post-war depression. The railroad was using three Shay locomotives in the woods and was moving an average of 15 or 16 loads daily and an equal number of empties (Ibid. 1922a, 1922c).

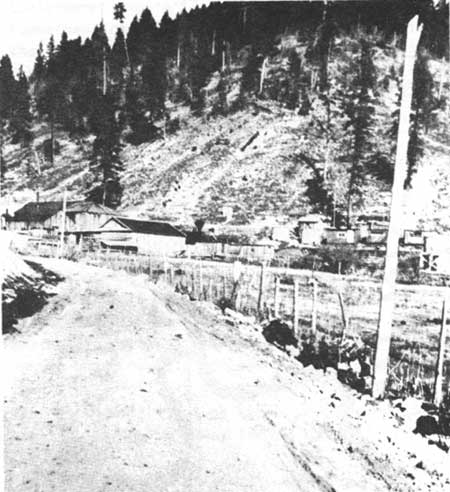

During 1922 SWLCo built its new permanent camp at a place called Marcia (Spoerl 1981). This became the terminal point for logging railroad operations with the woods engines bringing in loaded cars from the outlying areas to be consolidated into longer trains to be taken up to Russia.

During early September 1922, SWLCo purchased the remaining timberland of the Alamogordo Lumber Company. SWLCo had already bean cutting timber on these lands under the supervision of an ALCo employee. Other timber purchases had been made by SWLCo on the National Forest and on state land. These lands were to the southward and eastward of the SMLCo lands (The Timberman 1927).

SWLCo extended its new logging railroad following Penasco Canyon down from Russia. The line passed by the camp of the Penasco Lumber Company at Longwell (see the Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Company section), and for a time ended near the permanent camp being established at Marcia. Water was plentiful here, and the canyon was wide enough for the numerous camp buildings and dwellings needed to support the logging crews. A locomotive shop, called the "roundhouse", and a machine shop were built and equipped to perform the necessary maintenance on the locomotives and steam loaders used in the woods (Spoerl 1981).

During 1923 and 1924 SWLCo continued to expand. The railroad was pushed to the south and east of Marcia. The decision was made to climb up and over the intervening ridges rather than build twenty miles of track in the canyons to reach the timber in Wills and Hay Canyons (Figure 18). The new line climbed the south slope of Penasco Canyon and curved around the point into Willie White Canyon. Toward the head of this canyon, the track switched back and climbed to the ridge overlooking Wills Canyon. From this point the track followed the contours of the land and followed the slope southward for several miles. Logging in these distant canyons proceeded through the 1920s (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1923a; The Timberman 1924a).

|

| Figure 18. Southwest Lumber Company railroads around Penasco Canyon show sidehill construction and switchbacks for crossing ridges between canyons. (click on image for a PDF version) |

In the meantime, the company had been receiving logs from Ben Longwell's Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Company, which was logging on the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation. Logging along Penasco Canyon slowed somewhat but did not stop altogether. Then, as the Mescalero logging slowed to a halt due to a lack of capital, Longwell built his short rail spur up Water Canyon, west of Marcia (Alamogordo News 1925). In late 1926, SWLCo began operating log trains over Longwell's trackage in Water Canyon, which had been built during the preceding year (Figure 19). This line was extended beyond its initial three mile length between 1926 and 1928, with some switchback spurs heading up side canyons. The entire line was gone by 1930 (Alamogordo News 1925, 1931).

|

| Figure 19. Logging crew with horses going into the woods from Water Canyon. The skidway disappearing up the side valley and the neatly stacked "cold decks" of logs are typical of the railroad reload points. June 28, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233051) |

During the next few years logging continued without disruption. The logging locomotives ware converted from coal to oil fuel starting in May 1928. This was both a fire prevention measure as well as an economy measure based on the rapidly dropping cost of oil (Alamogordo News 1928b). In April 1929 logging engineer E. C. Owens was injured when his locomotive fell through a weakened trestle near Marcia. The upkeep of the railroad was getting expensive. Three section crews of six men each were occupied with track maintenance. They were also organized as fire crews in addition to their routine tasks (Alamogordo News 1928c, 1929a).

By 1927, SWLCo had disposed of the heavy steam skidders and had retained the services of Cooper and Otey, logging contractors who had worked on the Mescalero Reservation and for various logging companies out of Flagstaff, Arizona. Logging with horses continued in the steep canyons, but the newly matured Caterpillar tractor found a place as well. The tractors were used with hydraulic steal arches, the successor to the oak "big wheels" used for years in the pine woods (Figure 20). The use of tractors proved to be effective and very efficient, and their numbers grew accordingly (The Timberman 1927) (Figure 21).

|

| Figure 20. Caterpillar tractor and hydraulic arch hauling logs for George E. Breece Lumber Co. on Mescalero Apache Reservation. (By J. D. Jones, USDA Forest Service photo 230661) |

|

| Figure 21. Skidding logs to railroad landing with Caterpillar tractor. June 1928. (Probably by E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233022) |

During May 1929 a fairly large quantity of state timber was advertised for sale. Located in Dark and Wills Canyons, the timber was just to the east of the current SWLCo logging shows. An estimated 15,344,000 board feet of pine and fir was involved. To everyone's apparent surprise, this sale brought to light a number of strong objections. Most of them came from the Roswell area from people involved in the growing tourist trade. They feared for the degradation of the scenery along the increasingly busy roads into the mountains. SWLCo, the high bidder, bought the timber in August 1929, the sale having continued in spite of the objections (Alamogordo News 1929b, 1929c).

During this period of expansion, the logging railroads were extended in two directions. One line continued down Penasco Canyon into Cox Canyon and back up Dark Canyon. The other route was a spectacular series of switchbacks dropping down into Wills Canyon from the "high line" between Willie White and Hubbell Canyons (Figure 22).

|

| Figure 22. The SWLCo extension south of Penasco Canyon used a series of switchbacks to reach Wills Canyon. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Construction of most of the new SWLCo railroad south of Marcia involved much more earthmoving and preparation than the earlier routes. In 1921 a Marion Modal 21 gas-electric power shovel had been purchased for just this kind of work. It saw plenty of use during the next several years building cuts and fills and side-hill roadbeds. In spite of the ability of a sharply curved logging railroad to follow the contours of the canyon slopes, a number of sizeable timber trestles were needed to carry the line across side canyons. As the rail lines grew in length, it became necessary to keep the running speeds up by eliminating switchbacks and rough spots in the track. This, in turn, required more expensive construction in the form of earthwork and trestles. The cost of log transportation was becoming an increasingly significant part of the overall cost of doing business (The Timberman 1924b).

At some time in the late 1920s, SWLCo decided to use switchbacks in a descending series to drop its tracks down into Wills Canyon. This arrangement accomplished the job with a couple of miles of steeply graded track hung on the canyon side. A sawmill with sidings was installed about a mile below the switchbacks. The line continued further down Wills Canyon for about four miles with short spurs going up several side canyons (The Timberman 1930; Rasmussen n.d.).

A second rail line from the Wills Canyon sawmill climbed the south side of the canyon. Using a gradient exceeding four percent the line wound along the ridge, looped up Bear Canyon and finally ended up overlooking Hay Canyon. From this point the line descended six well-engineered switchbacks to reach the floor of the canyon (Figure 23 and 24). A small camp was set up on an open spot about halfway down the slope. From the foot of the switchbacks, the tracks extended both up and down the canyon, covering about a three mile stretch.

|

| Figure 23. The SWLCo railroad climbed Out of Wills Canyon and wound along the ridges until it reached the switchbacks down into Hay Canyon. (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| Figure 24. Aerial photo of Hay Canyon switchbacks. |

The Hay Canyon line was well designed but rugged. Curves were sharp in many places. Grades were no greater than four percent and less in many places, easy enough for geared locomotives with short trains of logs. This kind of "switchback railroad" represents perhaps the high point of logging railroad development, used where high lead overhead cable or inclined planes were not practicable.

The national depression struck the Sacramento Mountain logging business during 1930. The Breece mill closed for an indefinite period in June 1930, and the SWLCo continued on an order to order basis. Their steady customer was the Southern Pacific Company, which bought cross ties for their Alamogordo treating plant (Figure 25). Louis Carr and J. A. Tatum of SWLCo took to the road to sell their lumber, a carload here and a carload there. Although the western mines remained their beset customers, lumber was sold as far away as Detroit. For a time in 1933 and 1934, lumber for the new Civilian Conservation Corps camps was also an important sale (Alamogordo News 1930b, 1932a, 1933a, 1933b).

|

| Figure 25. Southwest Lumber Co. yards at Alamagordo, with railroad ties stacked awaiting creosoting at Southern Pacific Co. treating plant nearby. July 2, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233474) |

During the depths of the depression, SWLCo continued to operate, although at a reduced level. In general only about half the number of men was employed during the 1930s as during the peak years.

The Wills Canyon and Hay Canyon switchback railroads apparently operated into the 1930s (The Timberman 1924a). In July 1935 SWLCo was the successful bidder on an estimated 29,800,000 board feet of timber located in twelve sections called the Agua Chiquita unit. During 1936 a railroad was pushed up Wills Canyon and over the summit to reach the upper Agua Chiquita. From the high point at over 9420 feet elevation the line dropped down upper Scott Able Canyon, skirted the Sacramento Rim, and finally worked its way into Agua Chiquita Canyon. A camp with sidings was built close to Rogers Ruins overlooking the Sacramento River Canyon. The long rail extension brought the SWLCo total to 30 miles (Alamogordo News 1936b).

At about the same time, SWLCo purchased the timber on the Cloudcroft Reserve from the Southern Pacific Company. The SP was the successor to a series of corporations which had preserved the heavily forested environs of the village of Cloudcroft for decades. After considerable controversy, SWLCo built a logging railroad around the south and east sides of town and logged under highly restricted conditions (Alamogordo News 1935, 1936a, 1936b).

The routine of logging was interrupted suddenly when, on November 2, 1937, SWLCo Heisler locomotive number 3 exploded at Marcia. The boiler was blown about 200 feet from the frame of the locomotive. Tommy Wilcox, the hostler and night watchman, was fatally injured. A nearly identical Heisler, number 15, was purchased from George E. Breece Lumber Company as a replacement (Alamogordo News 1937).

The timber resources available to SWLCo improved in 1940. Prestridge & Seligman, operating as the Valencia Company, began furnishing logs to the SWLCo mill. This was timber logged on the Mescalero Reservation as a continuation of the earlier Breece contracts. The timber was hauled by truck all the way to Alamogordo, using six new trucks purchased that year (Alamogordo News 1940a, 1940b). In addition, SWLCo purchased an estimated 30 million board feet of timber on the C. M. Harvey holdings between James and Cox Canyon. Special agreements protected the scenic and watershed qualities of the tract, and logging was done under Forest Service rules and supervision. Logging began in December 1940 (Alamogordo News 1940c).

Railroad operation continued into the war years. As trucks became more practical, they proved to be much cheaper than running trains over the tortuous logging railroad, now extended to thirty miles in length and requiring four locomotives. In late 1942, it all came to an end. The locomotives, cars and loaders were stored at Marcia, and all the wood spurs were taken up. The rail was sold for scrap and only the "main line" from Marcia to Russia remained (Neal 1966:65-66).

In spite of the wartime demands for lumber, it was clear that the SWLCo under Louis Carr was running down. The constant demands for higher wages, the long timber hauls and the aging sawmill all contributed to the decline. In 1943 Carr closed the main sawmill but continued to operate the planing mill finishing rough lumber shipped down from a small sawmill in the Agua Chiquita Canyon (Alamogordo News 1945).

It was not until 1945 that the railroad and logging equipment remaining at Marcia was brought up to Russia. One of the rusty Shay locomotives was fired up for the chore. During 1946, several SP trains carefully traversed the now little used track to Russia to bring out the SWLCo equipment for salvage.

P. S. Peterson, an SP engineer, and brakeman Wilbur Fifer had the job of bringing the remaining SWLCo locomotives down the railroad to Alamogordo. With locomotive 2510, they formed a train at Russia, with ancient logging locomotives separated by empty flatcars for added braking power. Peterson pulled the cumbersome affair down to Cloudcroft, and coasted right on by the water tank. The 2510 needed water, but lacked the power to back up the train to get back to the tank. And there was not time, under the Hours of Service Act, to cut off the locomotive and run down to Wooten for water and return. So he chained the whole outfit to the rails at the Cloudcroft depot and left with the 2510 for Alamogordo. In consideration of the risk in bringing the decrepit string down the steepest part of the mountain by rail, it was decided to leave the train where it stood. The entire outfit was cut up at the depot and trucked out (Neal 1966:66).

With the dismantling of the remaining logging locomotives at Cloudcroft in 1946, the era of railroad logging in the Sacramento Mountains came to en end. Although SWLCo was the largest such operation and was the longest lived, two other companies had operated logging railroad in the mountains as well. Their stories follow.

Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Company

In the Cloudcroft country in the 1920s, Ben Longwell was a man to be reckoned with. During a few short years he put together three complete businesses involving all aspects of lumbering from contract logging through sawmilling. Having worked for a number of Sacramento Mountain logging outfits since 1899, Longwell knew the business thoroughly, and the country as well (Neal 1966:14).

One of Longwell's independent enterprises was the Penasco Lumber Company, incorporated in New Mexico on August 24, 1918. During 1919, a sawmill was set up about 5 miles south of Russia, which milled about 25 to 30 thousand board feet a day. The lumber was hauled by wagon to Russia, using a road improved by the Forest Service. A logging camp grew up around the sawmill site (Figure 26) (Weekly Cloudcrofter 1918, 1919a, 1919b).

|

| Figure 26. Lumberyard and sawmill of Penasco Lumber Co., four miles south of Russia. May 1919. (By Quincy Randles. USDA Forest Service photo 162862) |

In 1921, Longwell and C. M. Pate, his partner from Louisville, Kentucky, organized the Cloudcroft Lumber & Land Company (CL&L) in New Mexico. Apparently the company had been incorporated several years earlier in Kentucky, and it was registered in New Mexico in 1921 as a foreign corporation (Alamogordo News 1921c).

The basis of the CL&L business was a contract between Longwell and the Bureau of Indian Affairs for the purchase of timber on the southern portion of the Mescalero Apache Indian Reservation. The area concerned was only a few miles northeast of Cloudcroft, amounting to some 30,000 acres of timberland in the Elk and Silver Creek drainages. About 160 million board feet of pine and fir was involved. The contract was advertised for sale during early 1920. Longwell, through CL&L, bid the minimum permitted and obtained the contract, which was finally approved on December 17, 1920, following some controversy over scenic values along the highways in the area (Kinney 1950:151-153).

It took a long time for Longwell and Pete to finance the development of their logging operations. During 1921 and 1922 Longwell was busy putting everything together. Among his activities was the surveying of a logging railroad north from Cloudcroft and east along Silver Creek to Silver Springs, a distance of about 8 miles. It was a well laid out line, with reasonable curves and a maximum grade of 3-1/2 percent (Alamogordo News 1923a). There was one major trestle of 346 foot length, with a maximum height of 36 feet. Grading of the railroad began in April 1923, but progress was slow. Longwell made arrangements to purchase a locomotive from the EP&SW, and rail began arriving for the new track (Alamogordo News 1923a, 1923b). Although 1-1/2 miles was laid during July 1923, the line was not completed to the cutting area until nearly a year later. Various problems delayed the work, but the greatest was a lack of strong financing. Wet weather, fire at a tie mill, and delays in bridge building were typical causes of the delays (Alamogordo News 1923c, 1924a, 1924b). In the meantime, lacking a large sawmill of his own, Longwell contracted to deliver his logs to the Southwest Lumber Company mill at Alamogordo. With this market for his timber, he rushed the railroad to completion during the spring of 1924, making the first shipment during the week of July 14, 1924. The Cloudcroft Lumber & Land Company was at last in business (Alamogordo News 1924).

The "new" locomotive of the CL&L was in fact one of the first four used on the A&SMRy. Rebuilt and equipped to burn oil fuel, it was well suited to its work (Howes 1965). The only other machinery of importance on the operation was a new steam shovel and log loader. Purchased in 1923, it was used initially to build the railroad grade, and later to load logs on the rail cars. Cars of the EP&SW were used (Albuquerque Morning Journal 1923b).

The CL&L property included a camp and maintenance buildings in Cloudcroft, located just above the wye junction with the EP&SW (Figure 27). A woods camp was established in upper Turkey Pen Canyon, north of Cloudcroft just over the Mescalero Reservation boundary. At this point the railroad turned east to run down to Silver Springs Canyon.

|

| Figure 27. Log train passing the wye track in Cloudcroft leading to the George E. Breece Lumber Co. railroad. The wye tracks were built to connect with the Cloudcroft Lumber and Land Co. railroad. (O. Rasmussen collection) |

By all accounts the timber on the Mescalero Reservation was of good marketable quality. But the cost of logging and shipping were high, with a 35 mile rail haul. In a little over a year after it began shipping logs, the CL&L was in receivership. On October 25, 1925, Longwell and Pate filed a petition of voluntary receivership in the District Court, and William Ashton Hawkins was appointed to be the receiver (Breece Papers 1935).

The assets of CL&L were of considerable value, especially the Mescalero timber contract. It was not long before some of the better financed timbermen were showing interest in it. By the spring of 1926, it became known that George E. Breece was negotiating with Longwell and Pate. At this time, Breece was logging in the Zuni Mountains to supply a big sawmill in Albuquerque. He operated three mills in Louisiana and Virginia, and he had a major interest in the new White Pine Lumber Company sawmill at Bernalillo, New Mexico (Alamogordo News 1926a, 1926c). Breece was successful in his dealings with Longwell and Pate and on June 3, 1926, the George E. Breece Lumber Company (GEBLbr) took over the assets and properties of the CL&L (Alamogordo News 1926c; Breece Papers 1935).

In the meantime, Longwell and Pate had become involved in another logging operation, which may have contributed to their financial strain. During June 1925 Longwell began laying railroad track along a three mile stretch of Water Canyon, connecting some timber he had bought about 1921 with the SWLCo logging railroad in Penasco Canyon (Alamogordo News 1921e, 1925). His development was slow and it was not until late 1926 that logging began. He made a deal with SWLCo to use their locomotives and the EP&SW log cars to haul his logs down to the SWLCo mill. About one million board feet per month were produced by this operation, which continued for several years (Alamogordo News 1926f). The railroad was extended further southward between 1926 and 1928, with a couple of spurs up side canyons. A camp was built at the confluence of Cathay and Brown Canyons (Figure 28). When C. M. Pate died on May 2, 1928, management of the logging was taken over by his son-in-law, C. K. Carron. Logging proceeded rapidly, and by 1930 the railroad and camp had been removed (Alamogordo News 1928a, 1931). While this small operation was going on, the former CL&L enterprise, now under the control of George E. Breece, was being transformed into a very substantial business.

|

| Figure 28. Logging camp at confluence of Brown and Cathey Canyons operated by C. K. Carron in partnership with Ben Longwell. June 27, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233517) |

George E. Breece Lumber Company

Colonel George E. Breece brought with him to Alamogordo an expansive style of operation and enough capital to see the job through. In addition to purchasing the CL&L on June 3, 1926, he dealt with the Southern Pacific Company for rail and equipment to extend his logging railroad. And he was dealing with the Texas-Louisiana Power Company on a proposition to use the waste from his new sawmill to fuel a new steam power plant, which would supply Alamogordo and nearby towns with an expanded supply of electricity. And all of this was to be built as quickly as possible (Alamogordo News 1926a, 1926b, 1926d).

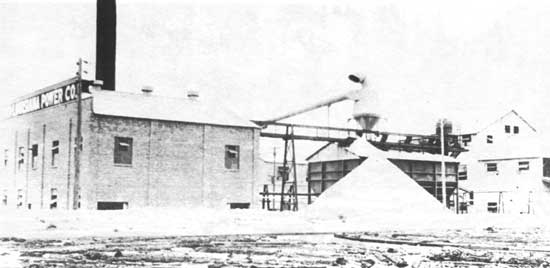

Within a month of the purchase of the CL&L, Breece had let contracts for a graded earth mill pond 300 x 600 feet, and for the structural work on a new steel and concrete sawmill. At the same time, the Texas-Louisiana Power Company began construction of its new steam plant. Both plants were located on a site purchased from George Carl, northwest of the SP depot. In that simpler era construction moved rapidly, and on February 23, 1927, the power plant supplied steam to the sawmill for the first time to test out the equipment (Figure 29). And on February 27, 1927, the sawmill began cutting timber (Alamogordo News 1926a, 1927a, 1927b).

|

| Figure 29. George E. Breece Lumber Co. sawmill (right) and Texas-Louisiana Power Company steam power plant. The mill waste fed the steam boilers of the power plant, which in turn powered the sawmill as well as an electric light plant for the towns of Alamogordo and La Luz. June 30, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233358) |

Up in the woods above Cloudcroft, Breece had been equally energetic. The railroad had been extended several miles eastward along Turkey Canyon to Cienega Canyon, and a camp had been set up in that vicinity. The old locomotive of the CL&L was refurbished and prepared for operation. The actual logging was contracted out. C. H. Cooper had two tractors at work and employed 150 men. He would soon add two more tractors (Figure 30). J. C. Tarkington logged with another craw of 150 men. Between them, the two contractors were delivering 75,000 to 80,000 board feet to the railroad daily. They began work about October 1926 (Alamogordo News 1926g) and had approximately four million board feet ready when the mill opened in February 1927.

|

| Figure 30. Skidding logs with hydraulic arch and Caterpillar tractor on the Mescalero Apache Reservation. George E. Breece Lumber Co. June 30, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233084) |

As soon as the sawmill was completed and in operation, work began on the planing mill and box plant at the Breece mill site in Alamogordo. These new plants went into operation around June 1, 1927. The Breece enterprise was not without its problems. The sawmill was suddenly shut down in early 1927, soon after opening, when it was found the mill pond would not hold water. The solution came quickly if expensively in the form of a concrete lining. By July 11, 1927, the mill resumed operation (Alamogordo News 1927c, 1927d, 1927e).

Breece continued to operate at an intense pace (Figure 31). The railroad was extended to the east from time to time, following Silver Springs Canyon and then turning northward into Elk Canyon. It ultimately went about two miles up Elk Canyon. The national economic depression caught up with GEBLbr during 1930, and in early June the entire operation was shut down for an indefinite period. At this time, the operation employed from 350 to 400 men. The railroad included 25 miles of track, both main line and spurs, with four locomotives and two loaders (Alamogordo News 1930a; The Timberman) (Figure 32). There was a logging camp in Silver Springs Canyon with a machine shop, engine house, water and fuel tanks, and a large number of dwellings (Gilbert 1965) (Figure 33).

|

| Figure 31. Log landing and cut over slope on Mescalero Apache Reservation, George E. Breece Lumber Co. contract. February 26, 1932. (By M. M. Cheney. USDA Forest Service photo 265477). |

|

| Figure 32. George E. Breece Lumber Co. loader working at landing on Mescalero Apache Reservation. The loader moves from car to car on rails permanently mounted on each car. June 30, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233085) |

|

| Figure 33. Cooper's logging camp in Silver Spring Canyon, Mescalero Apache Reservation, operated for Geoege E. Breece Lumber Co. June 26, 1928. (By E. S. Shipp. USDA Forest Service photo 233313) |

An interesting and damaging result of the Breece shutdown was the immediate stoppage of the waste wood fuel supply to the Texas-Louisiana Power Company. The utility was forced to use more expensive fuels and, finally, installed two diesel generator sets to supply Alamogordo and La Luz. The diesels were placed in use in late December 1932, at which time the steam plant was shut down permanently. To recover some of the unexpected expenses, Texas-Louisiana sued Breece for breach of contract, asking $10,610.51 in damages for the failure to deliver fuel. Texas-Louisiana was itself in receivership at the time (Alamogordo News 1932b, 1932c).

Recovery was slow. Breece remained shut down until 1935, when a number of small circular sawmills were installed at various woods locations. Green rough cut lumber was shipped down to the planing mill at Alamogordo, but it appears that the logging railroad was little used, if at all, following the 1930 shutdown (Neal 1966:65). Breece sold the logging railroad for scrap to Walter B. Gilbert of Albuquerque in 1938 or 1939. Two of the locomotives were trucked out for use elsewhere, but Gilbert salvaged everything else on the railroad as wall as most of the equipment and tools remaining at the logging camp (Gilbert 1965).

During the summer of 1940, Prestridge and Seligman bought the Mescalero timber contracts from Breece and began shipping logs to the SWLCo mill at Alamogordo by truck. This operation was conducted under the name of the Valencia Company (Alamogordo News 1940a, 1940b).

The Breece mill at Alamogordo remained idle until 1941. In March it was announced that Prestridge and Seligman had purchased the mill and would reopen it as quickly as possible. On June 3, 1941, the mill whistle blew for the first time in 11 years and 100 men went back to work. Another 100 were logging on the Mescalero Reservation. Twenty-five trucks were used to bring the logs down from the mountains, bypassing the railroad system in its entirety (Neal 1966:65; Alamogordo News 1941).

Epilogue

With Prestridge and Seligman established in the old Breece mill, and using trucks for log hauling, SWLCo was left with an aging sawmill, and a long expensive rail haul to feed it. Much of the rail system was older than the sawmill, and it was vulnerable to mountain weather and high maintenance costs. It came as no surprise when SWLCo shut down its logging railroad in 1942, ending the era of steam railroad logging in the mountains.

SWLCo continued a troubled existence during the war years. Strikes resulting from attempts to obtain better wages were a regular occurrence. Louis Carr protested in response that the money was just not available to pay better wages. Carr closed his ancient main sawmill in Alamogordo but continued to run the planing mill. It was fed with green lumber cut at the Frank Carr mill in Agua Chiquita Canyon.

In early September 1945, M. R. Prestridge, the head of Prestridge and Seligman, announced the purchase of all the assets of SWLCo, including a timber contract on the largest stand of private timber remaining in the Sacramento Mountains. It was stated that Prestridge and Seligman planned to build their own railroad into the timber from the connection with the SP at Cloudcroft (Alamogordo News 1945). This never came about and trucks were used for all subsequent log hauling to the Alamogordo mills. It was likely that this decision, which removed the primary economic justification for the continued operation of the SP Cloudcroft branch, that set the stage for the abandonment of the branch.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

lincoln/cultres4/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 02-Sep-2008