|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 1

Settlement and Resource Use in the Intermountain West

The Creation of Region 4

After the creation of the first forest reserves in 1891, the Federal Government centralized responsibility for administrative decisions in Washington, DC. Inspectors and forest supervisors reported directly to the administration—first to the Interior Department's General Land Office and then, beginning in 1905, to the Agriculture Department's Forest Service. Decisions on virtually all questions from the number of livestock to the establishment of a sawmill to the authorization of a small timber sale had to have Washington approval.

The adoption of a new policy in 1908 changed that. In that year, the Forest Service created six administrative regions (then called districts) each supervised by a regional (district) forester to whom the Washington Office delegated substantial authority. Under the new system, responsibility for such matters as reports and plans for the individual forests passed to the regional forester. Most importantly, regional foresters were authorized to exercise administrative discretion over a number of functions. Over time, their authority was extended: indeed, the forest supervisors themselves amassed considerable autonomy in making decisions for the forests under their administration.

The 1908 reorganization created the Intermountain Region (District) or Region 4, with headquarters at Ogden, UT. This region covered national forest lands in Idaho south of the Salmon River, Wyoming west of the Continental Divide, Utah, Nevada, a small portion of western Colorado, and Arizona north of the Grand Canyon. The configuration of the region has changed somewhat in the period since its creation. The region has lost northern Arizona, gained a portion of eastern California, and experienced some readjustments in Wyoming. Nevertheless, the general outlines have remained.

Geography and Geology

Geographically, the largest portion of Region 4 is the Basin and Range province of Nevada and western Utah. [1] The Basin and Range province consists of mountains of between 7,000 and 13,000 feet in elevation separated by intermountain plains generally formed by alluvial fans of eroded waste. Typical mountain ranges run on a north-south axis for 50 to 75 miles and may be 6 to 15 miles wide.

South and east of the Basin and Range lies the Colorado Plateaus province. The term "plateau" may seem misleading, as the highest physical features, which appear from the nearby valleys to be mountains, rise more than 11,000 feet above sea level. Occupying the eastern third of Utah and the southern fifth of Nevada, the province can be divided into the High Plateaus, which continue south and eastward from the termination of the Wasatch Mountains at Mount Nebo near Nephi in central Utah, the Canyon Lands south and east of the High Plateaus, and the Uinta Basin north of the Canyon Lands.

|

| Figure 1—View of Dixie National Forest from Strawberry Point. |

Curving in a northwesterly trending semicircle from the Colorado Plateaus lie the Middle and Northern Rocky Mountain provinces, which form the highest elevations in Region 4. With the exception of the Uinta Mountains, the ranges all trend north and south. The highest mountains, including the Wasatch and Uinta Mountains of Utah, the Wind Rivers and Tetons of Wyoming, and the Salmon River and Sawtooth ranges of Idaho, reach from 11,000 to nearly 14,000 feet above sea level. Most of the Northern Rockies in central Idaho consist of the loose granitic intrusions of the Idaho batholith. The mountains and high plateaus are very steep and easily eroded.

North of the Uinta Mountains lies the Bridger Basin, a part of the Wyoming Basin province. This basin stretches in a triangular fashion from an apex at the Gros Ventre and Wind River Mountains to the north and east and the Wyoming range to the west to its base at the foot of the Uinta Mountains on the south.

Sandwiched between the Northern Rocky Mountains in Idaho, the Middle Rocky Mountains of Wyoming, and the Basin and Range province of Nevada and western Utah are the Snake River and Payette sections of the Columbia Plateaus. The areas of this physiographic province range from generally below 5,000 feet in elevation to the Owyhee Mountains stretching into Idaho from the Nevada border that reach elevations of more than 8,000 feet.

|

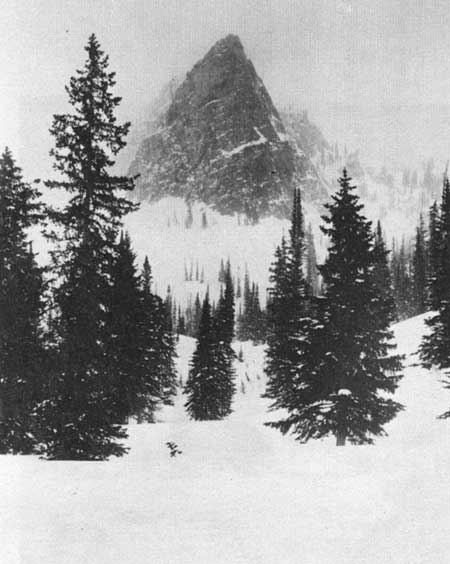

| Figure 2—Winter storm at Sun Dial Mountain, Big Cottonwood Canyon, Wasatch National Forest, Utah. |

Finally, on the western border of Region 4 lies the Sierra-Cascade Mountains province. This province is a virtual mirror image of the Wasatch range in Utah—volcanic in origin with extensive faulting along its eastern edge.

The principal watersheds of the Intermountain West originate in the region's mountains and high plateaus. Like giant icebergs, the mountains pierce the sky, cool the air, and precipitate rain or snow. Most of Region 4 is watered by storms moving on the prevailing westerly winds from the Pacific Ocean. The region lies in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada-Cascade range, although the Bermuda High in the Gulf of Mexico influences rainfall in the forests of southern Utah during July and August. Though some rainfall occurs from summer storms, precipitation is generally heaviest as snow in the late fall and winter months. The snow melts and flows into the valleys during the late spring and early summer. The valleys of the Basin and Range include some of the driest country in the United States, with less than 3 inches of rainfall per year. Runoff in the basin drains entirely into its interior. On the west, the Walker, Truckee, and Carson Rivers drain into Walker, Pyramid, and Carson Lakes. Runoff from central Nevada drains into the Humboldt River and eventually into the Humboldt sink. In Utah runoff drains either into the Sevier River or the Great Salt Lake.

|

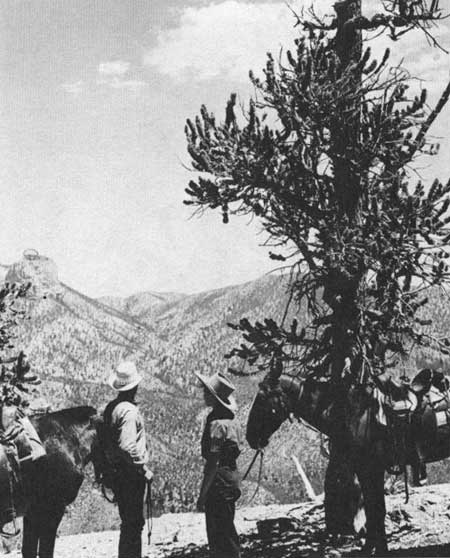

| Figure 3—View from trail leading to Charleston Peak, Toiyabe National Forest, Nevada. |

Drained by the Colorado River and its tributaries to the east and south and the Sevier to the west, the Colorado Plateau on the average is only slightly less dry than the Basin and Range. Although some portions of the High Plateaus may receive more than 40 inches of precipitation per year, the Canyonlands and Uinta Basin may receive less than 6 inches.

The Middle and Northern Rocky Mountain Provinces experience the highest precipitation in the region, ranging to over 50 inches per year, while the Payette and Snake River sections of the Columbia Plateau Province experience low precipitation, ranging from 16 inches in the highest portions of the Owyhee Mountains to less than 8 inches in parts of the Snake River plain. Runoff from these mountains drains into the principal systems of the region including rivers feeding the Great Salt Lake, the Green and eventually the Colorado River, the Snake River, and the Salmon River.

Because of the heavier precipitation, the mountains and high plateaus of the Intermountain Region produce the best stands of timber and the grass and forbs most valuable for summer grazing. Timberline ranges from about 9,500 feet in the north to 11,000 feet in the Uinta Mountains. Englemann spruce and subalpine fir dominate the highest elevation of timber stands throughout the region. Douglas-fir ranges slightly below or is intermingled with the spruce-fir forests. Next lowest is the lodgepole pine, which predominates in northwestern Utah, western Wyoming, and eastern Idaho. At still lower elevations one finds ponderosa pine stands, especially important in the Boise and Payette River drainages of western Idaho and in southern Utah. At the lowest elevations, particularly in the Colorado Plateau Province and in the Great Basin, pinyon-juniper forests dominate. The latter constitute the largest acreage of forest lands in the region. Dispersed among the spruce-fir forests throughout the region and to a lesser extent in the lodgepole and ponderosa pine, quaking aspen adds measurably to the game forage supply.

Region 4's national forests encompass important sources of both hard-rock and organic minerals. Pressure between overlapping plates of the earth's crust created an overthrust belt that passes through the Middle Rocky Mountain Province and the high plateaus. The pressure squeezed organic sediments laid down in ancient seas and transformed them into oil and gas. The overthrust belt also has exhibited an inordinate amount of geothermal activity, much of which is found in the national forests. The Canyonlands and Uinta Basin are also important sources of uranium and coal; coal, like other hydrocarbons, developed from sedimentary formations. Extensive phosphate deposits occur near the intersection of the Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming borders. Gold, silver, lead, and copper were deposited in the mountains of the region by volcanic intrusions. Major deposits occurred in the Wasatch and Oquirrh mountains of Utah, in the Idaho batholith, and in the ranges of the Great Basin.

|

| Figure 4—Autumn aspens. |

Native Americans of the Region

In this diverse land many Native Americans had located themselves before the arrival of Euro-American settlers. [2] With the exception of marginal penetrations by the Nez Perce on the northwest, some Algonkian-speaking tribes on the northeast, and the Navajo on the southeast, the aboriginal people of Region 4 were Shoshonean-speaking peoples belonging to the broad groups of Shoshoni, Ute, Bannock, Paiute, and Gosiute. [3]

In his comprehensive study of Western Indians, Joseph Jorgensen groups the Shoshoneans of Region 4 into what he calls the "Great Basin" environment. Jorgensen further subdivides the area into the northeastern section in the upper Snake and Colorado River drainage systems, where the Utes and Northern Shoshonis lived, and the Great Basin proper, which includes the Indians of the Basin and Range, the lower Snake River Plain, and the Colorado Plateau, particularly the Western Shoshonis, Northern and Southern Paiutes, and Gosiutes. [4] After studying the habitat of the various peoples, he concluded that the key factor separating the environments was aridity. [5]

The Indians of Region 4 had developed satisfactory means of adapting technology to the problem of subsistence. Utes and Northern Shoshonis used bows and arrows that they made themselves or acquired through trade with the Plains Indians. Great Basin Shoshoni and Paiutes made stationary fences of stone or wood or portable nets into which they drove antelope, rabbits, and even larger game and killed them with clubs, spears, or arrows. On the Snake and Green Rivers and in the lakes of Utah, the Indians used nets and seines as well as weirs and traps and spears to catch fish. Indians used native plant and animal materials to manufacture housing, clothing, cooking utensils, and weaving frames. Indians of the Great Basin region harvested seeds and nuts by knocking them from the native plants. Many dug roots, such as the camas plant. Some of the Paiutes cultivated corn. [6]

Moreover, the Indians used fire for a number of purposes. They burned dense undergrowth of grass and shrubs to stimulate desired plants, to improve the soil, and to kill insects and remove unwanted plants. They drove animals with fire. They were aware, however of the destructive force of fire and tried to contain it. [7]

Since these people lived almost entirely off native resources, one wonders why they did not devastate the land as extensively as their successors did. Two reasons are the Indians' relatively lower demand on resources and the relative sparseness of their population. Their technology was primitive. Within the area of Region 4, Jorgensen estimates that the population ranged from 0.2 to 1 person per square mile. [8] By comparison, in 1982 the density was 14 per square mile, and the technology and living standard made much greater demands upon natural resources. [9]

Vegetation and Wildlife

At the time of the Euro-American penetration, a rich diversity of lush foothill and mountain meadows, tall timber, and sagebrush covered or barren flats peppered the mountains and valleys of Region 4. The best sources on primeval condition are the records of early explorers. In 1776, Fray Francisco Atanasio Dominguez and Fray Silvestre Velez de Escalante passed through the Uinta Basin across the Wasatch Mountains into Utah Valley and southward to the Arizona border. On the Green River, south of the present Ashley National Forest, they found "a lot of good pasturage." [10] Along the Duchesne and Lake Forks they found timber and pastures. In and near Strawberry Valley, in what is now the Uinta National Forest, they found "a dense forest of white poplar, scrub oak, chokecherry, and spruce." [11] Southwest of Scipio on the fringes of what is now the Fishlake National Forest however, they found barren flats with poor pasturage. [12] They encountered pinyon-juniper forests together with "much pasturage" as they moved down the slopes in the present Dixie National Forest into the valley north of present day Cedar City. [13] To the south they found "a great source of timber and firewood of ponderosa pine and pinon, and good sites for raising large and small livestock." [14]

From the 1820's, trappers, traders, and explorers invaded the region from the East and Midwest, the Northwest, and New Mexico. Osborne Russell in 1835 found conditions in western Wyoming and eastern Idaho quite diverse. He described the Salt River Valley as "beautiful," covered with "green grass and herbage," grazed by "thousands of buffaloe," and surrounded by mountains "spotted with groves of tall spruce pines." [15] He reported Jackson Hole as "covered with wild sage," while the "alluvial bottoms . . . produce a luxuriant growth of vegetation." [16] The Teton Basin he described as a "smooth plain . . . thickly clothed with grass and herbage [abounding] with Buffaloe Elk Deer antelope etc." [17] Near Blackfoot Creek, he reported "dry plains covered with wild sage and sand hills." [18]

In 1843 and 1844, John C. Fremont also found vegetation to be quite diverse throughout the region. The country around Black's and Ham's Forks of the Green River, the Malad River of southern Idaho, the Bear River of northern Utah, and the Snake River plain near Shoshone Falls, he found covered with sagebrush. On the Malad plains, his party had only sagebrush for firewood. [19] About 40 miles southeast of Boise, at the foot of the Sawtooth Mountains, he saw verdant plains of grass, which he found quite inviting after "the sombre appearance" of the sage that they had looked at for such a long time. [20]

After traveling on to Oregon, Fremont returned to western Nevada, moved south, then returned via the Old Spanish Trail to Utah Lake. From there, he returned through the Wasatch Mountains and Uinta Basin to Colorado. In northern Nevada, he found sagebrush "the principal plant," with grass in the bottom land. [21] In the mountains near Reno, he reported principally pinyon. [22] He was quite depressed by the deserts of southern Nevada. The abundant vegetation of Utah Valley, the Wasatch Mountains, and the Uinta Basin impressed him. [23] J.H. Simpson in the 1850's commented on conditions in the Great Basin and Wasatch Mountains, essentially corroborating Fremont's findings. [24]

Travelers on the Old Spanish Trail in parts of what is now the Manti-LaSal and Fishlake National Forests indicated similar conditions. Orville C. Pratt camped on the Sevier River in 1848 and reported "the grass very good . . . water is fine, but no wood." [25]

Early diaries indicate that wildlife was quite unevenly spread over the eastern and northeastern portions of Region 4. Dominguez and Escalante found bison near the Green River in eastern Utah, abundant trout in Strawberry Valley, and waterfowl, fish, and other small animals in and around Utah Valley. The Indians told them of buffalo nearby to the north and northwest. [26]

During the 1820's, Jedediah Smith and Peter Skene Ogden visited portions of the intermountain region. Smith found his colleagues wintering in Cache Valley "living fat on the abundant fish and game." Ogden described the area between the Humboldt River and Ogden Valley "a gloomy barren country." In the Ogden Valley, however, he found tracks leading him to believe that elk were "plentiful in this locality." [27]

Between 1824 and 1826, Ogden directed trapping operations in the Snake and Humboldt river drainages of Idaho and Nevada. From near the Montana border north of present-day Salmon, ID, south into the Bear Lake region, he reported numerous herds of buffalo and elk, and a great many beaver. [28] As he descended the Bear River into Cache valley, he found buffalo scarce, but reported grizzly bear "in abundance." [29] His party found a similar abundance of buffalo in the Henry's Fork area. [30] In the area near Shoshone, ID, they found a great many deer. [31] On the Raft River, they discovered "large herds of Buffalo." [32]

As early as 1825, Ogden's journal indicates that the Henry's Fork region was "formerly rich in Beaver" but "now entirely destitute." [33] He discovered similar depletion north of present-day Bruneau, ID. [34]

In 1833 Joseph R. Walker led a party through western Utah and across Nevada. On the advice of Indians, they first dried 60 pounds of buffalo and antelope for each man, since they had been rightly warned they would find no big game between the Great Salt Lake and the Sierra Nevada. [35]

By 1835, other species had disappeared from areas where they had previously abounded. Osborne Russell found Cache Valley "entirely destitute of game," and he and his party were forced to "live chiefly upon roots for ten days." [36]

Russell still found considerable diversity in other areas. Between 1834 and 1841, he saw plentiful supplies of buffalo, antelope, elk, and deer on Ham's Fork of the Green, near Fort Hall on the Blackfoot River, and north of the Portneuf. While he found a great many waterfowl on Utah Lake and Great Salt Lake, northern Utah had little game. [37]

By 1843, Fremont found conditions had changed even more. Most of the Indians in western Idaho were subsisting on salmon and insects rather than larger wildlife, which was generally absent. [38] He found most of the buffalo gone from the portions of Region 4 they had formerly inhabited. He attributed the eradication to the work of fur traders who killed them for their hides in the mid- to late-1830's. [39] He was impressed with the abundant game of the Sierra west of Reno and Carson Valley, but found game extremely sparse in the Great Basin, except watercourses and near lakes such as Pyramid, where he noted some mountain sheep. He commented on the poor condition and sparse fare of Great Basin Indians. [40]

J.H. Simpson's exploration of the Great Basin in 1859 added additional information to Fremont's. He sited antelope near Meadow Creek, Utah, and near Butte Valley, and repeated reports of those animals, deer, and mountain sheep in Ruby Valley. [41] His party was particularly impressed with the waterfowl in Steptoe Valley and on the Reese River and Carson Lake. He commented on the fish and Reese River and Carson Lake as well. [42]

|

| Figure 5—Steelhead migrating up Camas Creek, Idaho. |

Wildlife and Plant Depletion After Settlement

Because of the uneven distribution and depletion noted by explorers, wildlife was irregularly situated at the time of settlement by Euro-Americans. When Thomas McCall and his family arrived in 1891, they found numerous fish in Payette Lake, and Weiser River was still an important salmon spawning stream. [43] The Salmon River mountains were plentifully stocked with deer, elk, moose, black and grizzly bear, bighorn sheep, and mountain goats. Beaver were plentiful in the valleys of the Payette and Weiser. Elk had disappeared from the Weiser and Little Salmon River, though beaver were plentiful. [44] Migratory game fowl were still plentiful on the Bear River in the 1880's. [45]

Other areas exhibited similar patterns. By 1890, the supply of big game in and around the Boise Basin had declined seriously, in part because of overgrazing by sheep, and in part because of heavy commercial hunting. [46] Meat hunters supplying Warren and hide hunters near New Meadows took a heavy toll in the Payette forest region. [47] The deer herds in the Wasatch-Cache forest area shrank in part because of excessive hunting by Indians. Elk had disappeared everywhere in Utah except the north slope of the Uintas by 1900. [48]

Because of extensive overgrazing and subsequent undesirable plant succession, by the end of the nineteenth century local writers tended to accept as typical the barren character of all the land at the time of settlement rather than the diversity that the explorers had found. As Orson F. Whitney put it in 1892, in Salt Lake Valley the settlers found a "broad and barren plain hemmed in by mountains, blistering in the burning rays of the mid-summer sun. No waving fields, no swaying forests, no verdant meadows to refresh the weary eye, but on all sides a seemingly interminable waste of sage-brush bespangled with sunflowers—the paradise of the lizard, the cricket, and the rattlesnake." [49]

Settlers viewing that valley for the first time in 1847, however, tell a much different story. Thomas Bullock reported that "the Wheat grass grows 6 or 7 feet high, many different kinds of grass appear, some being 10 or 12 feet high." Timber in the valley was limited, but exploring parties found some groves of "Box-Elder and Cottonwood" along the creeks on the well-watered eastern side of the valley. [50] On the west side, beyond the Jordan River, they found sagebrush and poorer soil. [51]

The situation in and around Salt Lake Valley was not unique. Settlers in Utah Valley found excellent grass and trees along the creeks and in canyons like Hobble Creek. [52] On an exploration trip down the plateau front and across to the area of present-day Panguitch in 1851, Parley P. Pratt found abundant pastures and forests of pinyon-juniper in the valleys and foothills south of Scipio, and "lofty pines" in the mountains. In other places, such as the region between Cove Fort and Beaver, he found barren table lands "nearly destitute of pasturage." [53]

The situation in southwestern Idaho at the time of settlement was quite similar to what the Mormons found in Utah. Early settlers in Emmett Valley found grass rather than sagebrush on the foothills adjoining the valley. They found little brush in the valleys between Emmett and Boise. [54] In various valleys on what is now the Payette National Forest early settlers reported verdant pastures of grass, sedges, and rushes. [55]

As trappers and traders adversely impacted on the vegetation and wildlife they also disrupted the economy of the Native Americans who occupied the land. Recent research by Victor Goodwin and Archie Murchie, focusing especially on Nevada, suggests that livestock over-grazed the depleted fragile grasslands thereby interrupting the Paiute-Shoshone food-gathering cycle except for pine nut gathering. [56] They also eradicated the buffalo from the Intermountain West, depleted beaver populations in certain areas, and initiated the destruction of a number of game populations in northern Utah. In this activity they also were aided by some of the Native Americans. As Calvin Martin put it, once contact and accommodation with Euro-American culture had "nullified" spiritual sanctions against overkilling animals, "the way was opened to a more convenient life-style." [57]

On the other hand, scientific and governmental explorations seeking information about topography and resources did not seriously damage the ecological balance. Thomas Nuttall and John Bradbury accompanied the overland Astorians in 1811, later to publish contributions on the flora and fauna of the region. Others included William Gambel and Frederick Wislizenus who crossed the Old Spanish Trail to California in 1841. They named several species, including Utah scrub oak and Gambel quail. John C. Fremont, under the auspices of the Corps of Topographical Engineers, conducted two expeditions in 1843-44 and 1845, described the country, and cataloged specimens of a number of plants and animals including the singleleaf pinyon. Other government explorations, including those by Howard Stansbury, John Gunnison, E.G. Beckwith, J.H. Simpson, Clarence King, George M. Wheeler, Ferdinand V. Hayden, and John Wesley Powell, each contributed to information and interpretation of portions of Region 4.

Settlement and Resource Use

These explorations, like the adventures of the trappers and mountaineers, served to advertise the intermountain country and to bring in more settlers. First were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) who occupied the Wasatch Front in Utah beginning in 1847. The Mormon expansion led to the settlement of substantial portions of the eastern Great Basin in Utah and Nevada, the Colorado Plateau and Uinta Basin, the Bear Lake and Snake River valleys of Utah and eastern Idaho, and the valleys of western Wyoming. By 1900, the Mormons had established more than 450 communities in the Western United States. [58]

These settlements established a pattern of community ownership and regulation of certain resources together with individual entrepreneurship in farms and businesses. Brigham Young decreed neither "private ownership of the streams that come out of the canyons, nor the timber that grows on the hills. These belong to the people," he said, "all the people." [59] County courts (predecessors of county commissions) regulated water use by cooperative irrigation districts. The county courts or prominent Mormons regulated timber use for "socially desirable ends." [60]

|

| Figure 6—Sheep grazing on Boise National Forest. |

Hard-rock mining in Utah followed after the Mormons began their settlements. Most centered in the Wasatch and Oquirrh Mountains near the Salt Lake Valley, and mining towns such as Alta, Park City, and Bingham spotted the Utah landscape.

After the abandonment of the Mormon settlement at Genoa in western Nevada, Carson Valley and the surrounding area emerged as a mining district. [61] During the 1850's, gold mining had begun on Mount Davidson. In 1859, the silver mines of the Comstock were opened, producing $300 million between 1860 and 1880. [62] On the heels of the Comstock, other Nevada mining camps sprang into prominence. Names like Eureka, Pioche, Treasure Hill, and Austin are indicative of expansion outside the Comstock area. [63]

Patterns in Idaho and Wyoming were similar to those of Utah and Nevada. Outposts like Fort Hall, Fort Boise, and Fort Bridger were established on the overland route in the 1830's and 1840's either to facilitate the fur trade or to protect migrants. Mormons moved north to establish a settlement on the Lemhi River south of its confluence with the Salmon in 1855. The Latter-day Saints abandoned Fort Lemhi, but made permanent settlements in the late 1850's in northern Cache Valley, and Bear Lake and Malad Valleys, before pushing into the Snake River Valley late in the nineteenth century.

In parts of southern Idaho, gold became the magnet drawing settlers. Beginning in 1861, miners poured into the Salmon River country and the Boise Basin. The north Salmon River diggings around Florence and Warren bad produced nearly $16 million by 1867. By 1864, an estimated 16,000 people lived in the Boise Basin, and Idaho City itself boasted a population of more than 6,000. The basin was producing between $60 million and $100 million. [64] In 1870, a gold rush to the Caribou Mountains opened portions of that country. [65] After 1879, the Wood River mines attracted people to south-central Idaho. [66] In 1876 and 1877, quartz mining for gold opened in Custer and Bonanza on the Yankee Fork southwest of Challis. [67]

Though a short-lived mining boom attracted people to the South Pass area in 1867-68, southwestern Wyoming received its greatest push from the overland traffic. In 1843, James Bridger and Louis Vasquez established a fort on Black's Fork of the Green River to serve the overland immigrants. Settlements like Green River and Evanston owed their prosperity to the Union Pacific railroad as crews constructed it through Wyoming in the late 1860's. [68]

|

| Figure 7—Cattle grazing on Challis National Forest. |

Cattle ranching drew additional settlers to Idaho. In what later became the Boise National Forest area, grazing began in 1862, soon after mining started. [69] In the Payette country, William J. McConnell and John Porter located a ranch in April 1863 above Horseshoe Bend, settlers moved into Garden Valley by 1870, and the tall grass of Long Valley attracted ranchers during the 1880's. [70] Weiser was settled in the early 1870's, and Thomas Cooper and Bill Jolley moved 50 to 60 head of horses into Meadows Valley in 1877. [71] Ed O'Neal and others drove cattle into the Pahsimeroi Valley northeast of Challis. [72]

Cattle ranching followed hard on the heels of mining in Nevada as well. As early as 1863, stockmen drove cattle from California into the country near Austin, NV. [73] Alexander Toponce herded 6,000 head of cattle from Salt Lake City to the Comstock mines in 1867. [74] In the early 1880's, ranchers moved into the Jarbidge area of the present Humboldt National Forest. William Hodges, the Estes family, Neal Beaton, W.S. and Richard Clark, and others began ranching after 1880. By the late 1880's, the "71" outfit grazed most of the southern portion of what is now the Jarbidge Ranger District. [75]

Early settlement of Wyoming's western slope was also cattle-related. By the early 1870's, William A. Carter of Fort Bridger ran some 2,000 head of cattle in Uinta County. He became a vice president of the Wyoming Stock and Wool Growers Association at its organization in 1871. In 1879, Daniel B. Budd and Hugh McKay drove about 750 Nevada cattle to the upper Green River valley. By 1885, extensive cattle ranching had become an important industry in Wyoming. [76]

In Utah and southeastern Idaho, the grazing situation was somewhat different. Excepting southeastern Utah, where a conflict developed between a Mormon cattle pool and ranchers who had moved in from the southwest, most grazing operations were adjuncts of small farming. [77] Farmers in most towns ran cooperative herds in the nearby mountains and deserts. The large herds owned by Mormon leaders and entrepreneurs like Brigham Young, Heber C. Kimball, and William Jennings and the large cooperative herds of Brigham City were the exception. [78] In some cases, ranchers and their families operated mountain dairies during the summers, producing butter and cheese for sale in the valleys. [79]

Sheep raising, which generally came later than cattle ranching, enjoyed a much more spectacular growth. Between 1870 and 1890, herds from Oregon, Washington, and California stocked the rangelands of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana. [80] During the 1880's, sheep raising became very important on what is now the Payette National Forest. [81] The arrival of the Oregon Short Line Railroad in the Boise area in 1884 made markets for lamb, mutton, and wool quite accessible. By 1890, sheep had become so plentiful that settlers in the Boise Basin accused sheepmen of spoiling game herds in the surrounding area. [82] In about 1889, drovers trailed the first large band of sheep from Oregon into Oneida County, ID. [83] Extensive sheep ranching in San Juan County, UT, dates from the mid-1880's when the San Juan Co-op brought sheep in. [84]

Cattle and sheep competed with one another for forage, and stockmen vied for the best herd grounds. Under those conditions, overgrazing soon became a noticeable problem in many parts of the region. [85]

Table 1—Cattle and sheep population in Idaho, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, 1870-1900

| State | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

| Idaho | ||||

| Cattle | 10,456 | 84,867 | 219,431 | 369,217 |

| Sheep | 1,021 | 27,326 | 357,712 | 3,122,576 |

| Nevada | ||||

| Cattle | 31,516 | 172,221 | 210,900 | 386,249 |

| Sheep | 11,018 | 133,695 | 273,469 | 887,110 |

| Utah | ||||

| Cattle | 39,180 | 95,416 | 200,266 | 356,621 |

| Sheep | 59,672 | 233,121 | 1,014,176 | 3,821,838 |

| Wyoming | ||||

| Cattle | 11,130 | 278,073 | 685,956 | 689,970 |

| Sheep | 6,409 | 140,225 | 712,520 | 5,099,765 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1890 Census of Agriculture, 3 parts, 1:100, 101, and 109; 1900 Census of Agriculture, 2 vols, 1:318 and 320. Because these are census figures, they include all animals in the states rather than just the Region 4 portions. | ||||

Ranching, mining, and farming, together with the urban, commercial, and transportational development that both preceded and accompanied it, generated demands for timber. The miners of Carson valley logged first in the nearby pinyon-juniper forests, and the opening of the Truckee Railroad between Virginia City and Carson City allowed loggers to range further into the Sierra Nevada. Miners created an almost insatiable demand for wood which was used for ore reduction, heating, and mine props. By 1880, the mines and mills of the Comstock had consumed an estimated 2 million cords of wood. [86]

Within a short time after settlement in the Salt Lake valley began, the pioneers constructed sawmills low in the nearby canyons. Gradually, as they harvested the lower timber, loggers moved the mills into the upper reaches of the canyons. Brigham Young and daniel H. Wells organized the Big Cottonwood Lumber Company, which opened three large mills, and for several years in the late 1850's they sawed more than 1 million board feet annually. The mills used a variety of power including saw pits, water, steam horse and ox. The lumbermen cut with hand axe and saw. [87]

In general, small operators did most of the logging. typical was the David K. Stoddard company on what is now the Targhee national Forest. [88] Located first in Logan canyon, Stoddard moved his operation to Beaver Canyon, between Spencer, iD, and the Montana border in 1879. Over the next 23 years, he moved his mill to 26 different locations in the canyon. Stoddard did all his skidding and hauling to the mill and from mill to market with oxen and horses.

Because of the limited capacity and the time consumed in horse and ox skidding, Stoddard had to move his mill quite often. He used four sets to complete cutting in Stoddard Creek and seven in the headwaters of West Camas. In the period before 1900, Stoddard operated in every canyon on the west slope from Idaho Hollow south.

In the early 1860's as mining opened in the Boise basin and other parts of central Idaho, lumbermen moved into the area as well. Whipsaws provided lumber for cabins, flumes, and sluice boxes. In some cases water-powered mills were used, but as early as 1863, lumbermen had opened a steam mill powered by machinery brought by ox team from the Columbia River. One sawmill on Bear Run above Idaho City operated a quartz mill from the same drive mechanism. one enterprising businessman constructed a small steam-driven railroad to haul cordwood from his mill to the main street in Idaho City. [89] As operations expanded throughout western idaho, settlers built log improvements on mining claims. Miners used wood at smelters, most of which loggers clearcut on the hillsides near the towns. [90]

Utah businessman David Eccles earned a fortune, in part from lumber operations. A Scottish immigrant, he took his first lumber job at age 21, when he contracted to skid logs near the junction of Wheeler Creek and the Ogden River. Moving his operations to Monte cristo in 1872, he joined with several others in purchasing a sawmill in 1873. As his undertaking prospered, he opened lumber yards in Ogden and sawmills near Scofield in Carbon County. Later, he expanded into idaho and the Pacific Northwest as well. [91]

Reports indicate the Eccles operations near Scofield used "very destructive methods." Loggers would burn the side hills during the heat of the summer to kill the timber and remove the undergrowth. They then moved in to "high-grade" or "harvest only the choicest trees," leaving the rest to rot. The burning made it easier and cheaper to get the best timber out, but the ecological devastation was a high price to pay. [92]

As the railroads moved into the intermountain region in 1868, tie hacking became one of the most rugged and lucrative businesses in the area. Loggers cut on the north slope of the Uintas as the Union Pacific built its tracks through Wyoming and eastern Utah. In 1873, the Utah and Northern Railroad extended its line from Ogden to the mines in Montana. In the mid-1880's, as the Oregon Short Line was built across the Snake River plain, loggers moved into the North Fork of the payette. [93]

Methods of bucking the timber varied. A large tree would yield two 8-foot ties, and on occasion the treetops were made into mine props. [94] Some operators, however, were interested only in the ties and made no attempt to process other portions of the trees. Like David Eccles's operations, this left the forests devastated after the loggers moved out. Slash and litter covered the ground, leaving wasted wood and fire hazards. [95]

Union Pacific came to dominate the tie market in the eastern and northern portions of the Intermountain Region. Prices for number one ties deflated from $1 each to 30 to 40 cents. On the north slope of the Uintas and in the Payette's North Fork, William A. Carter, of Coe and Carter, became the major supplier. Alexander Toponce, an active western businessman, together with John W. Kerr, a Salt Lake City banker, and Charles S. Durkee, a former Utah governor, contracted to cut 100,000 ties on the north slope. [96] During the 1870's, the Evanston Lumber Company, owned in part by Jessie L. atkinson, handled most of the river traffic for the tie operators from headquarters at its Evanston, WY, sawmill.

Reminiscences of logging operations evoked considerable nostalgia among participants. Alexander Toponce recalled the Temple sawmill in Logan Canyon, saying that for him the sound of the saw "eating its way through a pine log, or the odor of fresh pine saw dust," generated particularly vivid memories. He remembered the bull whackers dragging heavy logs, bucked into 16-foot lengths. The whacker could pop a whip over the head of the ox with "a report as loud as a 38 pistol." [97]

|

| Figure 8—Sawlogs being loaded aboard flatcars by oxen, August 1888. |

Loggers used a number of methods of getting the logs out. They hauled them out by mule, drove them on spring floods, rafted them on rivers, or floated them on flumes. [98] lumbermen drove the timber for the Logan LDS Temple down the Logan river to a boom built about 3 miles from the canyon mouth. [99] In the 1880's, crowds thronged the banks of the Provo River near Woodland, UT, to watch boom after boom of logs ridden by dare-devil drivers float down the river. [100] On the north slope of the Uintas, a flume carried timber from the Hayden Fork 26 miles to Hilliard, with a 6-mile branch from the headwaters of the Stillwater Fork. [101]

On the South Fork of the Payette River, lumbermen decked the logs along the river bank then drove them during springtime floods to the sawmill at Horseshoe Bend. They used boats to carry food, bedding, and other equipment for the "river rats" who followed the logs downstream. A risky business, this. At least seven men drowned at a falls below Lowman where they had to let boats down by ropes from the shore. [102]

Not all people remembered the logging operations with the same nostalgia as Alexander Toponce. Joseph Rawlins found the task of securing fuelwood time consuming and arduous. The loggers started for the canyons early in the morning. They drove their wagon as far as possible over the steep roads, and made camp. They spent the rest of the first day cutting the pines and skidding them out with horses, single-trees, and drag chains. The next day, they bucked the logs into cord-wood lengths, secured the wood to the wagons with chains, and that afternoon took it down the canyon. It required as many as 20 such trips to supply wood for winter stoves. [103]

In some areas, the loggers developed a distinctive culture. Asa R. Bowthrope recalled the lumbermen living in Mill Creek and Big Cottonwood Canyons. A deeply religious folk, they reported mysterious disappearances of tools and nocturnal manifestations including the repeated automatic starting and stopping of the mill. Approaching Brigham Young for guidance, they were advised to move the mill, because the ground where it stood was sacred to the spirits of the people who once lived there. They seem to have placated the spirits since after they moved, the mysterious events stopped. [104]

Operators found markets for their lumber in the towns and cities, in the mines, and on the farms of the inter-mountain region. By the 1870's, lumber yards had opened in major cities. An Ogden lumber yard owned by Bernard White hauled lumber from Paradise in Cache Valley. In some cases, the yards manufactured specialty products like laths, shingles, pickets, sashes, doors, blinds, moldings, tongue-and-groove boards, and lathe and scroll work. [105]

Except in Idaho, lumber production did not grow steadily. The logging business peaked in Utah, Wyoming, and Nevada between 1870 and 1880 as railroad construction and mining boomed, then declined during the 1880's and 1890's. Wyoming's lumbering recovered and flourished by 1900. Utah's lumbering stabilized at a lower rate. Nevada's previously flourishing lumber industry had virtually died by 1900. In Idaho, with its more extensive timber resources, the lumber industry showed rather consistent growth to 1900 (table 2). [106]

Table 2—Lumber mills and volume and value of lumber produced in Idaho, Nevada, Utah, and Wyoming, 1870-1900

| State | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 |

| Idaho | ||||

| No. of mills | 10 | 48 | 44 | 117 |

| Million bd. ft. lumber | — | 18.2 | — | 54.8 |

| Value of product ($) | 56,850 | 349,635 | 631,790 | 937,665 |

| Nevada | ||||

| No. of mills | 18 | 9 | 0 | 4 |

| Million bd. ft. lumber | — | 21.5 | — | 0.73 |

| Value of product ($) | 432,500 | 243,200 | 0 | 7,060 |

| Utah | ||||

| No. of mills | 95 | 107 | 32 | 81 |

| Million bd. ft. lumber | — | 25.8 | — | 12.1 |

| Value of product ($) | 661,431 | 375,164 | 249,940 | 214,187 |

| Wyoming | ||||

| No. of mills | 8 | 7 | 17 | 52 |

| Million bd. ft. lumber | — | 3.0 | — | 88.5 |

| Value of product ($) | 268,000 | 40,990 | 124,462 | 831,558 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Compendium of the Tenth Census (1880), pp. 1162-63; and idem., 1900 Census Vol. 9, part 3 Manufactures, pp. 808-810 and 817. Because these are census figures, they include all portions of the states indicated rather than simply the Region 4 portions. | ||||

Local timber shortages developed in some areas. As early as 1880, lumber operations had stripped the west base of the Wasatch Mountains, and various areas of northeastern and north-central Utah were short of timber. Between 1880 and 1884, Utah became a net importer of lumber. [107] In 1890, Nevada reported no lumber production, and by 1900, its production had recovered only marginally. [108]

The development of ranching and lumbering exacted a high price from the land. Orson Hyde observed in 1865 "the longer we live in these valleys that the range is becoming more and more destitute of grass: the grass is not only eaten up by the great amount of stock that feed upon it, but they tramp it out by the very roots: and where the grass once grew luxuriantly, there is now nothing but the desert weed, and hardly a spear of grass is to be seen.... [On the benches] there was an abundance of grass: . . . they were covered with it like a meadow. There is now nothing but the desert weed, the sage, the rabbit-brush, and such like plants, that make very poor feed for stock," [109]

By 1890, range and forest deterioration had become even more noticeable in many parts of the intermountain west. Denuded watersheds above some of the towns produced flooding, and less desirable but hardier plants had replaced the grass and trees in canyons and on benches where they had previously flourished. Environmental change made much more of the region look like the sagebrush plains Fremont had seen in the Snake River and Malad valleys or the alkali flats Dominguez and Escalante had described west of Scipio. Large game species had virtually disappeared from many northern Utah ranges. Under those conditions, it became easy to generate demands for resource conservation.

Reference Notes

1. The following discussion of the physical geography of Region 4 is based on: Nevin M. Fenneman, Physiography of Western United States (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1931): Charles B. Hunt, Physiography of the limited States (San Francisco: W. H. Freeman, 1967): Wallace W. Atwood, The Physiographic Provinces of North America (Boston: Ginn and Company, 1940): Colin W. Stearn, Robert L. Carroll, and Thomas H. Clark, Geological Evolution of North America (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979): Mary Moran, "The West was formed by Clashing Crustal Plates," High Country News, June 25, 1984, pp. 11-12: Deon C. Greer et al,, eds., Atlas of Utah (Ogden and Provo: Weber State College and Brigham Young University Presses, 1981): and U.S. Geological Survey, The National Atlas of the United States of America (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1970).

2. For a discussion of the Indians of Region 4 see: Brigham D. Madsen, The Northern Shoshoni (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1980): idem., The Lemhi: Sacajawea's People (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1979): idem., The Bannock of Idaho (Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Printers, 1958): Robert A. Manners, Paiute Indians I: Southern Paiute and Chemehuevi: An Ethnohistorical Report (New York: Garland, 1974): Julian H. Steward and Erminie Wheeler-Vogelein, Paiute Indians III: The Northern Paiute Indians (New York: Garland, 1974): Julian H, Steward, Ute Indians I: Aboriginal and Historical Groups of the Ute Indians of Utah (New York: Garland, 1974): Anne M. Smith, Ute Indians II: Cultural Differences and Similarities Between Uintah and White River (New York: Garland, 1974): Carling Malouf and Ake Hultkrantz, Shoshone Indians: The Gosiute Indians, The Shoshones in the Rocky Mountain Area (New York: Garland, 1974): Virginia Cole Trenholm and Maurine Carley, The Shoshonis: Sentinels of the Rockies (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1964): and Floyd A. O' Neil, "A History of the Ute Indians of Utah Until 1890" (Ph.D. diss.: University of Utah, 1973).

3. On the native peoples of the region see Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., The Indian Heritage of America (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1968): The following discussion of cultural attributes of the Shoshonean tribes of Region 4 is based on Joseph G. Jorgensen, Western Indians: Comparative Environments, Languages, and Cultures of 172 Western American Tribes (San Francisco: W.H. Freeman and Company, 1980).

4. Jorgensen, Western Indians, pp. 95-96.

5. Jorgensen, Western Indians, pp. 23-28.

6. Jorgensen, Western Indians, pp. 105-28, 334-51, and 381.

7. Stephen J. Pyne, Fire in America: A Cultural History of Wildland and Rural Fire (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1982), pp. 71-83: Stephen W. Barrett, "Indians and Fire," Western Wildlands 6 (Spring 1980): 17-20 (copy in historical files, Payette National Forest).

8. Jorgensen, Western Indians, pp. 161-64, and 445-47.

9. U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1984 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1983), p. 10.

10. Ted J. Warner, ed. The Dominguez-Escalante Journal: Their Expedition through Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and New Mexico in 1776 trans. Fray Angelico Chavez (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1976), p. 43.

11. Warner, ed., Dominguez-Escalante Journal, pp. 48, 50-51.

12. Warner, ed., Dominguez-Escalante Journal, pp. 65-72.

13, Warner, ed., Dominguez-Escalante Journal, p. 74.

14. Warner, ed., Dominguez-Escalante Journal, p. 78.

15. Osborne Russell, Journal of a Trapper, ed. Aubrey L. Haines (Portland: Champoeg Press, 1955), p. 12.

19. John C. Fremont, The Expeditions of John Charles Fremont, Vol. I Travels from 1838-1844, ed. Donald Jackson and Mary Lee Spence (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1970), pp. 494-95, 516, and 528.

20. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:535.

21. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:598, 600.

22. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:615-16.

23. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:684-86, 697-98, 704-09.

24. J.H. Simpson, Report of Explorations Across the Great Basin of the Territory of Utah (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1876), pp. 30, 47-50, 64, and 87.

25. Information on Your National Forest: Fishlake National Forest (n.p., 1964), p. 1.

26. Warner, ed. Dominguez-Escalante Journal, pp. 44-45, 50, 60.

27. Cited in Orange A. Olsen, "Big Game in Multiple Land Use in Utah," Journal of Forestry 41 (1943):792.

28. Peter Skene Ogden, Peter Skene Ogden's Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, ed. E.E. Rich and A.M. Johnson, Publications of the Hudson's Bay Record Society vol. 13 (London: Hudson's Bay Record Society, 1950), pp. 18, 20-22, 24, 30, 42.

29. Ogden, Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, pp. 45, 152-53.

30. Ogden, Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, pp. 60-61, 65.

31. Ogden, Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, p. 177.

32. Ogden, Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, p. 159.

33. Ogden, Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, pp. 60-61, 65.

34. Ogden, Snake Country Journals, 1824-26, p. 92.

35. Olsen, "Big Game," pp. 792-93.

37. Russell, Journal, pp. 3, 5-7, 9, 11, 13, 123, and 125.

38. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:538.

39. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:490-92.

40. Fremont, Expeditions, 1:599, 605, 607-09, 617, 702.

41. Simpson, Explorations, pp. 62, 64, and 78.

42. Simpson, Explorations, pp. 59, 85, and 78.

43. History: Payette National Forest (n.p.: Intermountain Region, Forest Service, n.d.), p. 9.

44. History: Payette, pp. 10-11.

45. Charles S. Peterson and Linda E. Speth, "A History of the Wasatch-Cache National Forest," (MS, Report for the Wasatch-Cache National Forest, 1980), p. 250.

46. Elizabeth M. Smith, History of the Boise National Forest, 1905-1976 (Boise: Idaho State Historical Society), p. 99.

48. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," pp. 249-50.

49. Cited in Richard H. Jackson, "Righteousness and Environmental Change: The Mormons and the Environment," in Thomas G. Alexander, ed. Essays on the American West, 1973-1974 (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), p. 23.

50. Journal of Thomas Bullock, July 22, 1847, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah, cited in Jackson, "Righteousness and Environmental Change," p. 27; Journal of Henry Bigler, October 1848, Brigham Young University Library, ibid.

51. Jackson, "Righteousness and Environmental Change," p. 29.

52. Utah's First Forest's First 75 Years ([Provo, Utah: Uinta National Forest, ca. 1972]), p. 5.

53. Excerpts from Life and Travels of Parley P. Pratt, historical files, Fishlake National Forest.

55. History: Payette, pp. 11-12.

56. Victor Goodwin and Archie Murchie, History of Past Use and Management Precendents and Guidelines, Pinyon-Juniper Forest Type, Carson-Walker RC &D Area: Western Nevada (n.p.: Nevada Division of Forestry, 1980), p. 38.

57. Calvin Martin, Keepers of the Game: Indian-Animal Relationships and the Fur Trade (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978), p. 154.

58. This figure is an estimate based on Lynn A. Rosenvall, "Defunct Mormon Settlements: 1830-1930," in Richard A. Jackson, ed. The Mormon Role in the Settlement of the West (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1978), pp. 51-52 and 54-55. I have tried to exclude settlements outside the Mountain West from the total.

59. Cited in Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1958), p. 52.

60. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, p. 54, citing Feramorz Fox.

61. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom, pp. 85-86 and 176-78.

62. Rodman W. Paul, Mining Frontiers of the Far West 1848-1880 (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963, pp. 56-61.

63. Paul, Mining Frontiers, pp. 102-08.

64. F. Ross Peterson, Idaho: A Bicentennial History (New York: W.W. Norton, 1976), pp. 57-58: Smith, Boise, pp. 11-13: History: Payette, p. 15.

65. G.L. Garr, "Talk Given to the Bannock County Historical Society on April 16, 1968," File 1650: Contacts and Other, I, Historical Data, National Grasslands, 6/1/60-4/30/64, Caribou.

67. Nancy Carol Luebbert, "History of the Yankee Fork Mining District, Custer County, Idaho," (Honors thesis, Dartmouth College, 1978), pp. 13-17

68. For a discussion of the impact of the Railroad see Robert G. Athearn, Union Pacific Country (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971), especially pp. 298-99.

72. Julia Furey, "Pahsimeroi Valley" in J.W. Deinema to Forest Supervisor, November 6, 1952, Black Folder, historical files, Challis National Forest.

73. Ivan Sack, "History of Toiyabe National Forest," MS, historical file, Toiyabe.

74. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 176.

75. "History of the Jarbidge Ranger District, Humboldt National Forest," File: Prior to Establishment of Forest, historical files, Humboldt.

76. T.A. Larson, History of Wyoming 2nd ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1978), pp. 165, 167, and 177

77. On the situation in Southeastern Utah see: Charles S. Peterson, "San Juan in Controversy: American Livestock Frontier vs. Mormon Cattle Pool," in Thomas G. Alexander, ed., Essays on the American West, 1972-1973 (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), pp. 45-68; Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," pp. 177-78.

78. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 177.

79. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 177.

80. Lawrence Rakestraw, A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest, 1891-1913 (New York: Arno Press, 1979), p. 25.

81. History: Payette, pp. 12-14.

83. Caribou History, p. 27, Typescript, historical files, Caribou.

84. Albert R. Lyman, History of San Juan County 1879-1917 (n.p., 1965), p. 44.

85. History: Payette, pp. 12, 14; Lyman, History of San Juan, pp. 44-45.

86. Goodwin and Murchie, Pinyon-Juniper Forest Type, pp. 38-43.

87. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 113; Charles S. Peterson, Look to the Mountains: Southeastern Utah and the LaSal National Forest (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1975), pp. 208-10.

88. The following is based on : 1, Information, Historical Data (Stoddard Lumber Co.), MS, 1951, Targhee NE History, File 4, Targhee.

91. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 120.

92. James L. Jacobs oral history interview by Thomas G. Alexander, February 6 and 15, 1984, p. 39, Historical Files, Regional Office. See also L.J. to George L. Burnett, January 27, 1961, folder: I-Reference File, Fiftieth Anniversary, Manti Division, 1953, Manti-LaSal.

93. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 123: Smith, Boise, p. 82.

95. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 129.

96. The information on the Payette River comes from Smith, Boise, p. 82. That on the Uinta and most of the following comes from Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," pp. 124-29

97. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," pp. 130 citing Toponce's reminiscences.

98. Sherry H. Olson, The Depletion Myth: A History of Railroad Use of Timber (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), pp. 23-24.

99. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 121.

101. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 127.

104. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," pp. 115-16.

105. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 121.

107. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 113.

109. Cited in Jackson, "Righteousness and Environmental Change," pp. 37-38.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region/4/history/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 11-Feb-2008