|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 2

Resource Management in the Intermountain West Before 1905: The Interior Department Phase

Acquiring Land and Regulating Disposal

Although westerners could file claims on mineral lands and purchase or homestead crop lands, they made customary rather than legally sanctioned use of grass and timber on the public lands. In the arid Intermountain West, if settlers could irrigate and farm land, they could purchase or homestead it in farm-sized tracts. If they wanted title to land suitable only for grazing or lumbering, they could get it only by fraudulent or inadvertent entry, or with land scrip until 1878. Thereafter they could only purchase such lands in 160-acre lots and in limited areas. [1]

Until the mid-1870's, the General Land Office (GLO) did little to try to regulate the customary use of grazing and forest land in the West, except to require trespassers to pay stumpage fees when they were caught with illegally harvested timber. In 1876 and 1878, GLO Commissioner James A. Williamson ordered employees to obtain approval from Washington before accepting such payments, and he appointed special timber agents to investigate illegal cutting on the public domain. [2] The policy was not popular in the West, but it had some curbing effect. [3]

In 1878, Congress passed the Timber Cutting Act, which allowed residents of the West to cut trees on public mineral lands for domestic purposes. Westerners thought this would solve the problem of access to needed resources at first, but Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz and Commissioner Williamson interpreted the law so narrowly that they forbade lumber companies legal access unless they had specific authorization from customers. [4] Schurz and Williamson understood the unpopularity of their interpretation, but felt bound to enforce the law, though they did propose to modify it. [5]

Later, Interior Secretary Henry Teller of Colorado, a westerner himself, tried to make the law more palatable to the West. He construed "domestic" purpose to include lumber dealers, mill owners, and railroad contractors and allowed limited export of lumber from one territory to another. [6] Nevertheless, Teller continued vigorous prosecution of those harvesting public timber in trespass. [7]

The Cleveland administration moved to a policy even more restrictive than that of Schurz and Williamson. In 1885, Interior Secretary L.Q.C. Lamar and GLO Commissioner William A.J. Sparks ordered employees to allow only small settlers and miners to cut timber. Calling Teller's views a "misinterpretation," Sparks said that the previous policy tended "to promote and protect trespass upon public timber." [8] Westerners, however, thought Sparks's policy would retard growth. [9]

Cattle ranchers experienced similar disfavor. In general, until the Lamar-Sparks administration, customary grazing on the public domain continued without interference after settlement. Sparks, however, refused to recognize ranching as a legitimate industry. In a letter to John Wasson, surveyor general of Arizona, he said that herders "of cattle will not be considered as settlers or permanent residents." [10] He could not stamp out the customary use, but he made it clear he was opposed to it.

These policies and prejudices did not eliminate ranching and lumbering from the public lands of the Intermountain West. By 1890, stockraising had become a leading industry in all of what was to become Region 4, and a larger percentage of the population was engaged in lumbering everywhere in Region 4 except Utah than in the remainder of the United States. [11]

Westerners made numerous suggestions for changes in policy, and sentiment grew for permitting the sale of timber and grazing lands. As early as 1874, the Commissioner of the General Land Office proposed that the Federal Government sell "timber bearing lands for the purpose of placing the timber under the protection of private guardianship," a proposal Williamson renewed in 1876. [12] LaFayette Cartee, surveyor general of Idaho, agreed, suggesting that the government sell "small tracts of eighty or one hundred sixty acres," which he believed would "prevent destructive fires and the fearful waste and destruction of timber now going on." [13] Some of the most creative proposals on cattle ranching came from John Wesley Powell and John Wasson, who favored large stockraising homesteads. [14]

Given the general fear of land monopoly so pervasive in late 19th-century America, such sentiment was always in a minority; most wanted some provisions only for limited sale or lease of the resources. Some, like Secretary Schurz and John Wesley Powell of the Geological Survey, preferred that the Federal Government retain ownership of the public timber lands under a system of regulated logging. Secretary Lamar recommended provisions for sale of timber on the public lands for domestic purposes "with proper provision for designating the lands from which such timber is sold." [15]

In the Far West, opinion divided between those who favored unrestricted access and those partial to protection under some system of utilitarian conservation. [16] In 1885, for instance, both Colorado and California appointed forest commissions to investigate the condition of local timber supplies, with a view to both utilization and protection. [17] Governor Francis E. Warren of Wyoming favored "leasing of timber lands under certain restrictions." [18] Governor George Shoup of Idaho recommended the creation of timber protection districts throughout the States, particularly to guard against forest fires. [19]

In an attempt to deal in a limited way with the timber problem for some States of the Far West, in 1876 Aaron Sargent of California introduced a bill to allow individuals to purchase 160 acres of unreserved but surveyed nonagricultural timberland for $2.50 per acre in Washington, Oregon, California, and Nevada. Supporters limited the plots to 160 acres to try to prevent speculation, while at the same time making lumber available for legitimate uses. Sargent's proposal was finally passed as the Timber and Stone Act in 1878; Congress extended it to all Western States in 1892. The act also included a clause prohibiting the cutting or destruction of timber on any public lands with the intent of exporting or disposing of it. The law excluded supplies for miners, farmers, and ranchers from this provision. [20]

A major problem in the development of policy allowing judicious use of timber from the public lands for domestic purposes was a pervasive fear of eventual timber shortage. Influential observers in the nineteenth century tended to think of absolute volume of timber rather than accessible volume as the determinant of timber availability. [21]

In part, the attitude can be attributed to the influence of German forestry schools and practitioners, but the belief was much too pervasive to have originated entirely from that source. [22] Its supporters included both the practical and the romantic. [23] The list embraced scientists such as George Perkins Marsh and John Wesley Powell, politicians such as Carl Schurz and L.Q.C. Lamar, bureaucrats such as Franklin Hough and Edward A. Bowers, and foresters such as Bernhard Fernow and Gifford Pinchot. Influential organizations, for example, the Boone and Crockett Club, the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, the American Association for the Advancement of Science, and the American Forestry Association, supported this position. [24] Fear of a timber famine led, in part, to the creation of the Bureau of Forestry in the Agriculture Department in 1876. [25]

Considerable justification existed for this point of view. Forest fires tended to burn uncontrolled in many areas. [26] Tie hackers and others wasted timber. [27] Local shortages occurred in eastern metropolitan and midwestern areas before the Civil War. On the plains with an absence of trees, consumers had to import lumber long distances at considerable expense. [28] Still, by the 1880's, most markets had sufficient lumber at a reasonable unit price. [29] As Sherry Olson has pointed out, improved transportation and technology made declining actual volume irrelevant and accessible volume the proper determinant of timber availability. [30]

In the Far West, however, policies like those of the GLO under Williamson and Sparks caused difficulties because of the restrictions on division of labor through business enterprises. In 1890, Senator Wilbur F. Sanders of Montana proposed that the Federal Government allow free use of timber in the Far Western States for general agricultural, mining, manufacturing, or domestic purposes. He pointed out that the West Coast and the Lake States contained the nearest legally obtainable timber, making transportation unnecessarily expensive. Sanders's proposal failed by three votes in the Senate, largely because of opposition from eastern and midwestern interests. [31]

The general attitude about the relationship between watersheds, rainfall, soil conditions, and timber resources created another problem. Instead of recognizing that vegetation consumed water, most people thought that it stored and released more water from a given area. Although many stockmen in the West did not believe this, Henry Gannett of the Geological Survey was one of the few public officials to contradict the conventional wisdom. Fernow challenged him, arguing that heavy vegetation produced more water. [32]

|

| Figure 9—Railroad tie jam on Green River near Kendall Guard Station, 1900. |

Creating and Administering Forest Reserves

By the early 1890's, the sentiment for protection of some timber resources and preservation of vegetation to enhance water production prevailed. In April 1889, the law committee of the American Forestry Association, consisting of Fernow, Edward A. Bowers, and Nathaniel Egleston, presented their supporting views to President Benjamin Harrison, Interior Secretary John Noble, and USGS Director Powell. Others, including Edgar Ensign of Colorado, John Muir of the Sierra Club, and Congressman Richard E. Pettigrew of South Dakota, lobbied for protection as well. The result was an amendment to the General Revision Act, generally called the "Forest Reserve Act," authorizing the President to set aside forest reservations for the protection of timber and watersheds. [33]

The Federal Government moved rapidly to protect certain public timber. Harrison created the Yellowstone Timber Reserve, now part of the Bridger-Teton and Shoshone National Forests in Wyoming, as the first reservation in 1891. By the time he left office in 1893, Harrison had created 15 reserves covering 13 million acres. Grover Cleveland added an additional 5 million acres the same year. [34]

The process for securing the designation of reserves in the early 1890's was quite similar. Ordinarily, settlers, residents, associations, or individuals would petition for the protection of timber or a watershed. They usually cited protection from wanton destruction by lumbermen or fire, or the perceived "rapid and permanent diminution of the water supply." Thereafter, a GLO special agent would inspect the area and recommend its acceptance or rejection. [35]

Congress provided no mechanism for administration of the forest reserves until 1897. Nevertheless, the Forest Reserve Act saddled the GLO with three tasks in the field of timber management. First, the GLO administered the sale of the open public lands covered by the revised Timber and Stone Act. Second, it protected the forest reserves against any public use. Third, it regulated access to timber on the public lands under the Timber Cutting and the Timber Permit Acts. The basic difference between the two acts was that the Timber Cutting Act restricted unregulated logging to mineral lands, whereas the Timber Permit Act allowed cutting under regulation on nonmineral lands. [36]

In practice, between 1891 and 1901, the GLO combined the second and third functions into one—administration of the public timber—under Division P (the Special Service Division), which bore responsibility for investigating infractions of all public land laws. Actual administration fell to a corps of special agents. Ranging in number from 38 to 55, the agents reported on cases and recommended civil or criminal suits or compromises, depending on the severity of the infraction. [37]

A circular of May 5, 1891, outlined the methods of securing timber from the public lands under the 1878 and 1891 acts. By the 1890's, the GLO had abandoned Sparks's interpretation of these acts and allowed individuals and businesses to cut for the local market. Under the Timber Permit Act, anyone could apply to cut timber either for his own use or "for purposes of sale or traffic, or . . . manufacture" as long as the trees grew on nonmineral lands. The applicant had to demonstrate to the satisfaction of the GLO that the timber was "a public necessity" and that harvesting would not damage the watershed. [38]

Though the special agents of Division P had originally investigated all breaches of the public land laws, by 1892, increasing demand for lumber turned their attention almost exclusively to investigating alleged depredations under the timber statutes. Their reports formed the basis for determining whether to issue permits or not. Usually, the GLO reviewed the permit applications quite carefully. [39] Perhaps as a result, and because of the depression of the early 1890's, the number of applications declined from 425 in 1892 to 50 in 1895. By 1895, Commissioner Silas W. Lamoreaux believed that the permit act had "failed to meet, to an appreciable extent, its purposed end. viz., that of providing for the legitimate . . . necessities of people dependent on public timber in settling and developing the country." [40]

Typical of the cases the special agents had to investigate was that of Mansfield, Murdock, & Company of Beaver, UT. Through contracts with a sawmill owned by Louis W. Harris and James E. Robinson, between 1892 and 1894 Mansfield and Murdock had bought timber cut in and near the abandoned Fort Cameron Military Reservation for resale to a mining company. After an inquiry of special agent J.H. Scales, the company determined that the timber grew on mineral land and believed that they could get it under the Timber Cutting Act. [41]

By 1895, however, Scales had changed his opinion, and the GLO dispatched special agent John L. Anderson to investigate the alleged trespass. After looking into the matter and securing affidavits from several disinterested parties, Anderson said the land was indeed mineral. [42] The two contradictory reports did not satisfy the Interior Department, and the GLO sent special agent Jesse E. Mercer to investigate. Mercer concurred in Scales's revised view that the land was nonmineral and said that Mansfield and Murdock had "purchased with guilty knowledge," charging that Harris & Robinson "were wilful trespassers." When the businessmen refused to offer a settlement, Commissioner Lamoreaux referred the case to the Justice Department, recommending a civil suit to recover the value of the timber. [43]

Attorney General Judson Harmon wrote to J.W. Judd, United States attorney for Utah, who investigated, then recommended against prosecution. Judd pointed out that the loggers had cut most of the trees on land within a designated mining district. Moreover, two special agents had said the trees grew on mineral land and one of them had produced corroborating affidavits from disinterested parties. Judd said that it had been his experience that juries in such cases were reluctant to convict. He pointed out that his record in timber trespass cases had been "exceedingly successful," and he felt this was a poor case to prosecute. [44] A reference of the case again to the Interior Department led to Commissioner Binger Hermann's opinion that "it would seem a useless expenditure of time and money to bring suit." [45]

Agent Anderson's work in the Mansfield & Murdock case was quite typical. During 1896, Anderson investigated allegations of timber trespass, failures to meet the terms of timber cutting permits, questions of validity connected with requests for such permits, and various recommendations for compromises or civil or criminal prosecution in timber trespass cases. In general, reasons Anderson gave for recommending rejection of permits included a sufficient supply for the local market, possible damage to the local watershed, the unreliability of the logger, or the proposed transport of the lumber across state lines. [46]

Often the GLO handled apparently routine applications without a special agent's investigation. Such applications, usually submitted through the land office, included affidavits from local citizens that the timber grew on nonmineral land, and evidence sufficient to satisfy the Commissioner that local businesses and individuals needed the lumber. They included evidence that the logging operations would not trespass on the rights of others, and that the removal of the trees would not injure the watershed. [47]

While the system of special agents provided a minimum of regulation, it furnished no permanent administrative organization. By the mid-1890's most who favored more effective administration, including the American Forestry Association, supported a bill drafted by Thomas G. McRae of the House Public Lands Committee. Introduced first in 1893, the McRae bill provided for Interior Department administration of the forest reserves. Under the bill, protection and utilization of timber and protection of watersheds were recognized as legitimate reserve functions. [48] Edward Bowers and others believed that the regulations of the McRae bill ought to be extended to all timber on public lands as well, repealing acts that allowed free use and the purchase provisions of the Timber and Stone Acts. [49]

This was not, however, the majority view. In commenting on the bill in 1896, Commissioner Lamoreaux agreed with McRae's version that allowed free timber to "settlers, miners, residents, and prospectors for minerals, for firewood, for fencing, building, mining, or prospecting purposes." He also opposed the extension of the bill to all public lands. [50]

In the meantime, however, other events were taking place that short-circuited the enactment process. By 1895, various people and groups from throughout the United States, including the New York Chamber of Commerce, the Los Angeles City Council, the American Forestry Association, leading periodicals of opinion, and influential conservationists like John Muir and Gifford Pinchot, supported the establishment of a national forestry commission to survey the public timber lands and recommend new forest reservations. [51]

Fernow's prescient argument, that without a system of forest administration and public education the creation of such reserves would antagonize people, carried little weight, and the Cleveland administration, with congressional support, appointed a commission. [52] On the recommendation of Wolcott Gibbs of the National Academy of Sciences, Cleveland chose Charles S. Sargent, director of the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard, General Henry L. Abbot of the Corps of Engineers, William H. Brewer of Yale, Arnold Hague of the Geological Survey, Alexander Agassiz of Harvard, and Gifford Pinchot, then forester at the Vanderbilt estate at Biltmore, NC.

Submitting its preliminary report on February 1, 1897, after a whirlwind trip through the Far West, the commission recommended 16 new forest reserves totaling 17-1/2 million acres. Parts of three of the reserves—the Uinta (then spelled Uintah) in northeastern Utah, the Teton south of the existing Yellowstone Timber Reserve in Wyoming, and part of the Stanislaus in California—were later included in Region 4. The commission's trip had more the character of a junket than a thorough investigation, since the members did not visit 5 of the 13 reserves they recommended, including the Teton. [53]

Nevertheless, moving with haste, Interior Secretary David R. Francis submitted the commission's preliminary report on February 6, recommending that Cleveland proclaim the reserves 16 days later to commemorate George Washington's birthday. [54] Cleveland's action, taken precipitately and without congressional or local consultation only 10 days before he relinquished the White House to William McKinley, evoked immediate negative response from the Far West. With a stroke of the pen he had created the first reserves since 1893, nearly doubling the existing acreage. Moreover, since Congress had approved no administrative procedures, the reserves were legally closed to any use.

Prominent in their opposition to Cleveland's action were Senators Joseph L. Rawlins of Utah and Clarence Clark of Wyoming. The Utahan called Cleveland's action "as gross an outrage almost as was committed by William the Conqueror, who, for the purpose of making a hunting reserve, drove out and destroyed the means of livelihood of hundreds of thousands of people." [55]

Maneuvering began almost immediately on the floor of Congress. Western senators introduced an amendment to the Sundry Civil Appropriations bill of 1897 to revoke the proclamations. Heading off the amendment, USGS Director Charles D. Wolcott, with the concurrence of Interior Secretary Cornelius Bliss and GLO Commissioner Binger Hermann, convinced Richard Pettigrew, by that time Senator from South Dakota, to introduce virtually the entire wording of the McRae bill as a substitute. In addition, the Pettigrew amendment suspended the proclamations for 9 months to allow the Forestry Commission to complete its report and the USGS to provide proper surveys of the reserves. While the members of the Forestry Commission recognized the need for some administration, with the exception of Pinchot and Hague they generally opposed the Pettigrew amendment because it seemed a temporary expedient. [56] In Congress, principal opposition came from a small group of southern, midwestern, and eastern Senators and from Representative John Lacey of Iowa, chairman of the House Public Lands Committee, who had apparently prevented enactment of the McRae bill previously by bottling it up in his committee. [57]

Contrary to popular myth, most westerners were not initially opposed to the creation of forest reserves. In a petition to the President on March 18, 1897, Senators Lee Mantle of Montana and Frank J. Cannon of Utah outlined their reasons for opposing Cleveland's proclamations. First, they pointed out, westerners would have to ignore the hastily designated reservation lines, or suspend the mining and grazing industries "in whole regions." Since the Forestry Commission had conducted only a cursory investigation, Cleveland's proclamation embraced "whole townsites and other improvements . . . so as to cut off the sole and natural supply of timber for domestic uses necessary to the existence of thousands of settlers on the public domain." Western opinion, they said, favored "preserving the sources of water supply and the maintenance of such restriction as will wisely preserve and enlarge the forest domain in the mountains. But it is certainly," they added, "an absurdity to make a forest reservation under a law and a proclamation which absolutely forbid forever the cutting of a stick of timber; because under such a law and proclamation the final purpose of forest reservation is destroyed." Instead, they favored the creation of reservations after a "well informed and carefully prepared report by the Geological Survey [and] due consultation with local authorities and the representatives in Washington of the states to be affected." [58]

Under the Pettigrew Amendment, now generally called "The Forest Service Organic Act," the USGS began an intensive survey of conditions in the reserves. Henry Gannett assumed general supervision of the investigations, the GLO detailed Gifford Pinchot as a special timber agent to draw together the USGS reports, and Dr. T.S. Brandegee of San Diego, a botanist who had worked on the northern transcontinental survey, went to Wyoming to examine the Teton and Yellowstone Park reserves. [59]

From July through September 1897, using maps prepared by the Hayden Survey, Brandegee moved through the two reserves. On the Teton reserve he found about 785 square miles of the 1,300 square miles capable of producing timber. Trees—largely lodgepole pine, quaking aspen, and Engelmann spruce—grew on about 38 percent of the acreage, but only about 3 percent of the timber was merchantable, largely because of previous forest fires. At the time of the investigation, loggers operated three sawmills in the Teton reserve, cutting mainly Engelmann spruce. Local settlers used dead lodgepole pine for log houses and fences. In addition, Brandegee found 40 ranches in the area, 19 on the eastern edge of the Teton Basin and 21 in Jackson Hole. Most were small cattle operations. Because of hostility of the ranchers, no sheep grazed in the reserve. Already, Jackson Hole had developed a reputation as a mountain resort for sportsmen, and many in the valley furnished supplies and outfits for tourists. [60]

Brandegee found conditions much different on the Yellowstone reserve. A reserve of about 510 square miles, it contained a larger percentage of timber than the Teton. He found no sawmills and little demand for the lodgepole pine and Engelmann spruce because of the distance from settlements. [61]

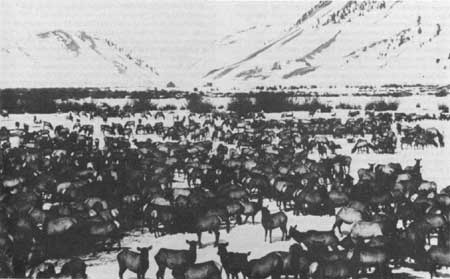

In 1897, the Forest Commission, Pinchot, and USGS investigators addressed a much more serious immediate problem than the potential loss of timber to the logger's saw. That was the extensive overgrazing by sheep and cattle on the western public lands.

The commission report said that as sheep outfits moved from Oregon and Washington across Idaho and Wyoming, the animals ate everything bare, carrying ruin in their path. They charged that the sheepmen were the principal cause of forest fires and that sheep hooves destroyed sod and undergrowth. [62]

Influenced apparently by Frederick Coville's careful studies in Washington and Oregon, in 1897 Pinchot presented a somewhat different view. He indicated that experience had shown that cattle, horses, and sheep could all graze without serious damage on the public forests provided herders kept them away from particularly fragile areas. He argued for 5-year grazing permits issued on the basis of traditional grazing patterns, stockmen responsibility, and established penalties including revocation for permittees who did not show "good faith in the protection of the forests." He recommended that permittees bear the cost of the administration through grazing fees. [63]

Currently available evidence suggests a disparate pattern of range conditions on lands ultimately included in national forests in Region 4 by the late 1890's. [64] Contemporary reports indicate the worst situation on the ranges in Utah, [65] the Bridger division of the Bridger Teton in Wyoming, [66] and the Caribou, [67] Boise, [68] Payette, [69] southern portion of the Sawtooth, [70] and the southwestern portion of the Targhee in Idaho. Conditions were relatively good on the Teton, the Salmon, and the Challis and the northern portion of the Sawtooth in Idaho. Evidence on the Toiyabe and Humboldt in Nevada is mixed, but it appears that in southeastern Nevada, the Ruby Valley, Humboldt Valley, and Paradise Valley were overgrazed. Western Nevada was not overgrazed, and northern Nevada did not become so until after 1900. [71]

Overgrazing combined with trampling and forest destruction contributed not only to the elimination of native plant communities but also to the introduction of less desirable plants. Studies have shown that in southern Idaho, grazing lands previously covered by sagebrush with an understory of perennial bunch grasses were replaced by Russian thistle, mustards, and cheatgrass by 1900. The invasion of cheatgrass was particularly serious because it burned so easily in range and forest fires. [72]

Even though Pinchot and Coville had argued that sheep could successfully graze under regulations to protect the environment, the prejudice against the "hooved crickets" led to an 1897 order excluding them from the forest reserves. [73] The GLO commissioned a study into the advisability of changing this regulation, but for the time being it stood in spite of sharp and vigorous protests from western livestock interests and congressmen. [74] Protests by Albert F. Potter and E.S. Gosney of the Arizona Wool Growers Association led to an investigation by Pinchot and Coville in 1899, who concluded that their 1897 recommendations had been correct and that grazing could be carried on under restrictions. [75]

|

| Figure 10—Overgrazing by sheep on Maple Creek drainage, July 1940. |

Since no sheep grazed on the Teton reserve in 1897, and the Federal Government created no new reserves in Region 4 until the Fishlake in 1899, the prohibition applied initially only to the Uintah. Petitions from the Utah Wool Growers Association and the Wool Growers Protective Association of Uintah County, WY, led to an investigation by Forest Superintendent W.T.S. May of Denver. [76] The petitions said that the sheep did not interfere with the water supply, that most sheep owners were among the leading citizens of the country, and that the sheep herders did not burn the grass, since it was contrary to their interest to destroy their own feed. [77] Support for their position came from John Henry Smith and Joseph F. Smith of the Council of Twelve Apostles and the First Presidency of the LDS Church. [78]

May recommended against allowing sheep on the reserve, but in a report on sheep grazing on the Uintah submitted on July 13, 1899, GLO Commissioner Binger Hermann recognized the contradictory opinions and evidence on the question. The only support for May's position came from the Utah Forestry Association, whereas numerous petitions from stock raising groups and the opinion of former Uintah supervisor George F. Bucher favored opening the reserve to sheep grazing. [79]

After reviewing the Pinchot-Coville recommendations, considering the view of the petitioners, and referring the question to various superintendents, including May, the GLO changed its position. A directive of July 20, 1899, permitted 200,000 sheep from Utah to graze in the open parks on the reserve during the 1899 season. [80] At the close of the season, Bucher reported that little damage had resulted and recommended that grazing continue. Moreover, in August 1899, the Interior Department issued a provisional regulation permitting sheep grazing on any reserves "in which it has been found, . . . after due investigation, that no injury will result to the reserve by reason of such pasturing." [82] The regulation became permanent in December 1901. [83]

The Forest Commission and others addressed the serious problem of competition and damage from transient herds, mostly of sheep. During the 1890's, the range near Scipio in central Utah, according to J. Wells Robins, had been overrun "with transient stock, migratory herds, trail herds, and surplus stock." As a result, his father and others petitioned for the creation of a forest reserve in the area. [84] Petitions in favor of the proposed Fishlake forest reserve said it was necessary "to protect the timber from fires and vandalism, and its vegetation from destruction by various agencies now going on." [85] It was the "various agencies"—probably a euphemism for transient herds—that concerned the local ranchers the most.

When the proposal to increase the size of the Fishlake reserve reached his desk in 1903, J.H. Fimple, acting commissioner of the GLO, quite reasonably raised some serious questions. After reviewing Albert Potter's report, he said that while "it is reported that the proposed addition is an exceptionally good grazing section, and that a large number of cattle, horses and sheep have been pastured within its limits, and recommendation is made as to the proper division of the area into grazing districts, the report contains no statement bearing upon the value of the area in question for forestry purposes, strictly speaking, exception that the proportionate distribution of forest and brush lands" is given. [86]

Clearly, however, such objectives were beside the point to western livestock interests. They wanted local control of the ranges. In Wyoming, Leonard Hay and William D. Thompson pointed out that numerous outfits from Utah and Idaho had invaded western Wyoming by the early twentieth century. This problem led to the infamous Raid Lake massacre. As Thompson told it, the issue was transient versus local herds rather than cattlemen versus sheepmen. According to Thompson, the Peterson brothers brought large nomadic sheep herds into western Wyoming from Utah. Their sheep mixed with the Thompsons' near Raid Lake where William and his brothers Joe and John worked as herders. After a warning, the cattlemen came in, tied up the Petersons' herders, and drove their sheep into one of Thompson's corrals. Significantly, they let Thompson's sheep loose because the Thompsons were local residents. Then, when they failed in an attempt to drive the Petersons' transient herds into Raid Lake, the cattlemen clubbed the interloping sheep to death. [87]

Like the Fishlake addition, the forest reserve in northern Elko County, NV, later part of the Humboldt National Forest, was created because of transient herds. As C. Syd Tremewan, a long-time resident and former forest supervisor put it, "flocks of transient sheep had become so numerous that the local ranchers were almost forced to quit trying to raise cattle with the public land as a summer range. . . . The mad race to get to the summer range first resulted in the intervening ranges being made into a dusty trail." Tremewan estimated that more than 500,000 sheep grazed on what became the northern division of the Humboldt National Forest. Later, reflecting on the situation, he wrote, "I often thank God that we moved [to take action] in time." [88]

Prior to 1897, the major problem in reserve administration had been the lack of a regularly organized force of forest officers. In his 1891 report Bernhard Fernow recommended the creation of a forest service to administer the newly designated reserves. These reserves required protection against theft, fire, and other damage, regulation of public use, and plans for cropping and marketing timber. He recommended relatively small ranger districts and the appointment of forest supervisors and rangers on the basis of demonstrated competence rather than political preference. He called also for the appointment of a group of centrally directed inspectors on the Prussian pattern. [89] Agreeing that Germany and France had provided more effective forest management than the United States, Interior Secretary Hoke Smith cited these countries as models for future practice. [90] In a December 1897 report, Pinchot recommended a plan for administration. Apparently recognizing budgetary realities, Pinchot's proposal was much less ambitious than Fernow's. [91] Nevertheless, the Fernow and Pinchot recommendations, both modeled on the Prussian system, formed the basis for the GLO Forestry Division and later, the Forest Service.

The actual organization was somewhat different than the model. Subject first to GLO Division P (the Special Service Division) and beginning in March 1901 to Division R (the Forestry Division under Filibert Roth), the administrative structure consisted of superintendents, with jurisdiction over an entire State or group of States; supervisors, who directed the work on individual reserves; and rangers, who directed districts within the reserves. In addition, a small corps of forest inspectors visited the reserves to examine various matters.

|

| Figure 11—Elk at Jackson Lake, 1905. |

Over time, the GLO Forestry Division tended to look more and more like Fernow's and Pinchot's Prussian-model forest service. The tendency in GLO administration over time was to decentralize by emphasizing the field force of supervisors and rangers and reducing the intermediate administration by superintendents. In 1898 there were 11 forest superintendents and a small force of supervisors. By 1904, that force had changed to 5 superintendents and 50 supervisors.

At the same time, the GLO upgraded the status of rangers. [93] At first the supervisors hired rangers as temporary employees, furloughed during the winter. Increasingly, however, responsible supervisors like Adolph W. Jensen of the Manti reserve asked permission to keep part of the ranger force over the winter and furlough the other rangers late in the season to complete necessary work. [94] In 1899 the GLO furloughed all rangers by October 15. By 1904 more than two-fifths were retained all year around. [95] Moreover, in 1902, the Forestry Division recognized the importance of the rangers by instituting the position of forest guard for temporary employees, especially those responsible for fire detection during the summer. [96]

The GLO emphasized the field force because of its own experience and because of changes made in consultation with Pinchot's Forestry Bureau. During late 1901, the two bureaus outlined increasing decentralization, codified in regulations in 1902. The policy granted forest supervisors greater autonomy by allowing them to report directly to Washington instead of through the superintendents. Increasing the responsibility of inspectors to investigate alleged improprieties provided checks on the system. [97]

Since the United States boasted fewer than 10 professional foresters in the late 1890's, those appointed to administer the forestry work were generally drawn from other occupations. [98] John Ise was highly critical of this tendency in the GLO Forestry Division, but seemed to see nothing wrong with it in the Forest Service. [99] Some of Pinchot's top subordinates like Albert Potter and Will Barnes were Arizona stockmen rather than professional foresters or range managers.

In practice, even in the GLO, with few professional foresters, the competence of the employees had little to do with their previous occupations. Adolph W. Jensen, for instance, served from 1903 as supervisor of the Manti Forest Reserve, continuing after 1905 in the USDA Forest Service. A graduate of Snow Academy, he attended Brigham Young Academy (later Brigham Young University) before becoming a schoolteacher and principal. He also served as Sanpete County Clerk and completed a law degree by correspondence. After the creation of the Forest Service's Regional Office at Ogden, he was appointed general counsel, eventually resigning to enter private practice. [100]

All of Jensen's rangers came from the local area, and a number of them had previous experience in ranching or logging before joining the division. Beauregard Kenner, for instance, had grown up in Manti and operated a sawmill in Manti Canyon before becoming a ranger. [101] David H. Williams had 2 years' experience with the Coast and Geodetic Survey and had worked in the livestock business before his appointment. [102]

Most of the difficulty in the GLO seems to have been in its corps of special agents rather than among the forest officers. Between February 1903 and April 1904, 22 special agents (nearly half the force) resigned "for one cause or another." Some left because of lack of capability, intemperance, or infirmity, others because they were caught in dishonesty, usually relating to the misappropriation of money, accepting bribes, or releasing confidential documents. [103]

Some difficulties existed in the GLO Forestry Division. Until late 1903, forest officers were political appointees, not covered by civil service regulations. This meant that they served at the pleasure of their superiors. After 1903, as merit employees, they were appointed after examination and could not be removed except for cause.

Perhaps the worst case of misadministration in what was to become Region 4 was that of George E. Bucher, supervisor of the Uintah Forest Reserve. Appointed in 1898, he was reduced to the rank of ranger in 1899, reinstated, furloughed, reinstated again. He finally resigned while under investigation in April 1902, largely for providing inaccurate reports of forest conditions and for placing the interests of individual forest users above that of the government. [104]

Most rangers and supervisors in Region 4 under the GLO were generally competent and diligent. Adolph W. Jensen reported in 1904 that of six rangers on his staff, four had proved "conscientious, industrious and willing." Another was newly appointed and had not yet proven himself, and the other had resigned under a cloud, but Jensen thought that he "did the very best in most cases according to his understanding," though he seriously "misjudged the work of ranger." [105] By late in the year, Jensen was apparently quite well satisfied with the work of the new ranger. [106]

While some of the early forest reserves like the Yellowstone were very large, after 1897 the Interior Department tended to create smaller reserves. Having learned its lesson from the intense objections to the cursory examinations associated with the Washington's Birthday proclamations, the Department undertook rather intensive surveys before recommending the creation of new reserves.

In the investigations, the GLO cooperated closely with the USGS, the USDA Forestry Bureau, and local people. By 1901, various Presidents had proclaimed three reserves in Utah: the Uintah, the Payson, and the Fishlake. From October 1901 through January 1902, the General Land Office sent papers to the Interior Department proposing the creation of 11 new reserves and an addition to the Uintah, stretching along the Wasatch Mountains and the high plateaus to the south. The subsequent creation process involved interaction between the agencies and parties mentioned.

A number of activities took place simultaneously. The GLO sent Superintendent May from Denver to look into matters relating to the proposed reserves. The USGS made its initial examination and recommendations. Senators Thomas Kearns and Joseph L. Rawlins and Congressman George Sutherland received numerous petitions both for and against the proposed reserves, some petitions went directly to the GLO, and others ended up on the desk of President Theodore Roosevelt. In the meantime, the General Land Office withdrew the lands within the proposed reserve boundaries from disposal, including State selections for schools and other purposes. [107]

As the agency most concerned with the new reserves, it fell to the GLO to make the final recommendations. After an initial investigation by the USGS and Superintendent May, Commissioner Hermann found that areas of several of the proposed reserves overlapped portions of the existing reserves and that the GLO had insufficient data to determine "the disposition" of some of the cases. He then recommended a "further, full and more detailed" report from the USGS. [108]

The subsequent investigation did not resolve all questions, [109] so the Interior Department called upon the Forestry Bureau for expert help. Pinchot sent Albert F. Potter, a former Arizona sheepman, to investigate. During the months from July through November 1902, Potter crisscrossed a north-south slice through the high country of Utah, hitting the principal towns and traversing the Wasatch Mountains and high plateaus. [110]

His comments covered the types, size, and density of trees, the condition of grazing lands, the protection of the water supply, and the attitudes of people. He found the most destructive grazing practices, timber cutting, and watershed damage in canyons and on mountains and plateaus nearest the settlements and in areas of greatest competition. Control by either private or public agencies minimized the destruction. The Ireland Land and Cattle Company managed a large area including possibly 40,000 acres of Federal land west of Emery in the mountains and on Quitchupah and Neotch creeks. There he found "good grazing land," and "a good stand of grass." [111] On nearby Salina and Clear Creeks outside Ireland's control, he found the lands "overgrazed and trampled by sheep," and the grass "all eaten off very close." [112] On the Uintah Indian Reservation, he saw "good grass and plenty of weeds and browse," because of controlled stocking. [113]

Most important, Potter's diary reveals a great deal about the attitudes of the people toward the creation of the forest reserves. In a letter to Interior Secretary Hitchcock, USGS Director Wolcott argued that the attitudes in Utah divided into two—on the one side being the farmers who are apparently, without exception, in favor of reserving the mountainous regions which are the sources of streams upon which they are dependent for irrigation: on the other hand are the cattle and sheepmen who are desirous of using these mountainous regions as a summer range for stock." This explains, he wrote, "the petitions and counter-petitions of which we are in receipt." [114]

Potter, however, found an ideological rather than occupational division. The division was not between farmers and ranchers, but rather between those who favored unrestricted resource use and those who wanted regulated use. Potter found more of the stockmen favoring than opposing the reserves. Their reasons included overgrazing and the need to reduce competition from transient herds. Townspeople mentioned the same things, but also noted damage to watersheds and excessive logging of small trees. [115] Moreover, many of those who opposed the reserves were not opposed to good land management, but believed that private owners could provide it as well as forest reserve officers. Potter agreed. [116] Virtually all thought that the Interior Department ought to make the decisions on the extent of the reserves as rapidly as possible, since land withdrawals in anticipation of reserve creation had proved disruptive to normal economic activities. [117]

All proposals did not require investigations as complex as the interrelated reserves in Utah. In the case of the Pocatello Forest Reserve, the city council and leading citizens of Pocatello petitioned for the reserve because of stream pollution from livestock in the nearby mountains caused by forest and range destruction. An investigation by GLO special agent C.L. Hendershot and another by the Forestry Bureau recommended establishment, and the GLO concurred. [118]

In western Wyoming, conditions differed. The boundary between the Yellowstone and Teton Forest Reserves had been arbitrarily drawn. Increasingly, by 1900, transient sheep herds began to challenge long-standing cattle operations. An investigation by F.V. Wilcox of the Forestry Bureau in 1901 tended to side with the cattlemen. In addition, he expressed concern about possible watershed damage and potential forest destruction from man-caused fires. [119] The GLO followed with an investigation by Special Forest Superintendent A.A. Anderson who recommended the union of the two reserves. [120]

On the basis of these considerations and the various investigations, the Interior Department recommended the disposition of various proposals. In Idaho, Utah, and Wyoming during 1903 and 1904, presidential proclamations designated the Pocatello, Aquarius, Manti, Grantsville, Salt Lake, and Logan forest reserves; enlarged the Payson, Fishlake, and Uintah reserves; and consolidated the Teton, Yellowstone Absaroka reserve under the name Yellowstone Forest Reserve. [121]

Moreover, cooperation between the Interior Department's GLO and USGS and the Agriculture Department's Forestry Bureau continued in the designation and administration of reserves. Some employees, for example, inspector Harold D. Langille, held appointments in both the GLO Forestry Division and the USDA Forestry Bureau. [122] Gifford Pinchot assigned employees to assist the GLO in developing working plans for forest reserves "so far as their other duties will permit." [123] The GLO could use such help only to the limit of its rather meager budget considering the demands for money by the force of supervisors and rangers. [124]

The two most serious problems faced by the GLO Forestry Division were the management of forest and grazing lands. In managing timber harvests, the GLO developed a body of regulations based on interpretation of the Organic Act. Initiative for a timber sale rested with the public rather than with the forest officers. The general procedure was outlined in a circular issued in January 1902. Individuals wishing to purchase timber applied to the forest supervisor. He had the area examined, marked, and mapped, and provided guidance in filling out the application and filing a bond. He then submitted the application to the GLO. If the GLO approved the sale, the supervisor advertised it in the local papers. Anyone could then bid on the timber sale, and the contract went to the highest bidder. [125] In order to regularize the sale procedure, the GLO devised a formal contract and bond in December 1901. [126] Regulations adopted in 1900 allowed the supervisor to sell the timber to the applicant at the appraised price, upon GLO approval, when he received no other bids. Supervisors were allowed to grant free use of timber worth less than $100, but were required to secure permission for a larger volume. [127] In January 1902, the Department published an application blank and a simple sheet of rules for use in applying for free use. [128]

One of the major problems was the general rule that lumbermen might not transport timber from one state to another. Opposition to this rule was especially strong in regions of Wyoming near the borders of other States. Congressman Frank Mondell, Secretary Hitchcock, and Commissioner Hermann all favored modifying the law to allow administrative discretion. [129] Technically, timber operations on the Uintah Reserve in Utah from Lonetree, WY, violated the law, since the timber had to be moved across State lines, but the GLO apparently ignored the technicality because of the proximity of the Reserve and the shortage of nearby timber in Wyoming. [130]

In administering the forest reserves, the GLO faced an immediate problem of educating both its own personnel and the forest users about proper land management. Of the reserves created in Region 4 in the 1890's, the most serious problems undoubtedly occurred on the Uintah. By 1903, although the greatest demand for timber was on the combined Yellowstone Reserve, the Uintah Reserve was close to the largest population centers, mining districts, and transportation routes in the region. [131] Unfortunately, its first supervisor, George Bucher, was a man of limited administrative ability who neglected the public interest in timber trespass and slash disposal. [132]

In the period before 1905, companies logged on the Uintah Forest Reserve from three bases. The largest group where those operating out of Summit County, UT—most from Kamas to supply mining companies like the Ontario, Silver King, and Daly-West at Park City. [133] A second group centered in Vernal just off the south slope of the Uintah. [134] The third, and much the smallest, was located in Lonetree, WY, just across the Utah border on the north slope. [135]

In general, these logging operations employed few people—often just a single family—usually based at a small sawmill. Typical perhaps was the Pack family of Kamas. [136] The Packs became the victims of bad advice during the Bucher administration, but an investigation by Inspector Langille and Bucher's replacement, Daniel S. Marshall, cleared them of culpability. According to Commissioner Hermann, Bucher and his rangers "alike believed that miners and residents have a right to the timber, and rules, regulations and instructions are troublesome formalities to be disregarded wherever possible." [137] After Bucher's removal, much of the work of the forest officers involved educating loggers in proper forest management, particularly in cutting in designated areas, taking only marked timber, and properly disposing of slash.

It should be emphasized that the Bucher fiasco was unusual and generally the result of the administrative incapability of one supervisor. A survey of available correspondence has turned up no similar situation in Region 4 under the GLO Forestry Division. Adolph Jensen's correspondence on the Manti, for instance, reveals a man concerned with possible irregularities, who also took time to instruct his rangers on their duties and forest users on their responsibilities. [138]

The GLO Forestry Division and Grazing Administration

If anything, grazing problems on those reserves created before 1905 were more serious than those involving timber. In line with Pinchot's views, in February 1900 Hermann recommended that the GLO charge fees for grazing in the forest reserves. [139] He withdrew the proposal, however, when Assistant Attorney General Willis Van Devanter ruled that the charge exceeded the Interior Department's authority under the Organic Act. The major change in supervisory regulations was a December 1902 amendment that allowed the GLO or even the "local officer, subject to revocal by the Department" to take care of "clerical details of issuing permits to the numerous applicants," rather than securing approval of the Department. [140]

The general unwillingness to allow sheep to graze on the same basis as cattle and horses caused considerable friction with parties from the West. At the annual meeting of the National Live Stock Association in Salt Lake City in 1901, Salt Lake sheepman John C. Mackay seems to have summed up the majority sentiment when he called for a liberal national land policy giving each sheep or cattleman with "permanent headquarters" access to the country "tributary to his interests." [141]

In responding to this problem, the GLO proposed general principles to govern range administration in November 1901. A number of these incorporated Pinchot's 1897 recommendations. These included delegating responsibility to the local woolgrowers association, granting 5-year permits, and regulating rather than prohibiting grazing. In meeting the demands of local graziers, the GLO gave preference to local rather than transient herds. [142] Provision was to be made for stock driveways. [143]

In January 1902, Hermann proposed regulations to implement the general principles, and to codify rules for grazing all stock. [144] The regulations established four classes of graziers: actual residents of the reserve, those residing outside the reserve who owned permanent ranches within the reserve, other persons living close to the reserve, and those with "some equitable claim." Secretary Hitchcock approved all except the proposal to allow 5-year permits. [145]

At the end of the 1902 season, however, the Forestry Division abandoned the attempt to delegate regulatory authority to the livestock associations. While it might have seemed a good idea in theory, in practice the associations had failed "to undertake the work of enforcing the rules under which the grazing was allowed." [146] In the case of the Uintah Reserve, for instance, the Utah Wool Growers Association failed to allot the range by units and actually permitted 39,800 more sheep than the 150,000 GLO limit. Supervisor Marshall had recommended a reduction from the 200,000 allowed the previous year, but the association failed to accept this recommendation. [147] In some States, such as Wyoming, the GLO could find no qualified association to work with and had to make the allotments itself anyway. [148]

Moreover, the regulation by sheep associations tended to discriminate against certain stockmen. In the case of the Uintah Reserve, for instance, the Utah Wool Growers Association, who controlled the reserve, were reluctant to allow sheepmen from southwestern Wyoming, even those with property in Utah, to graze on the reserve because of the limitation on numbers imposed by the Forestry Division. In responding to complaints, the Interior Department ruled that "if the owners [of the sheep] . . . pay taxes on them in the State of Utah, their habitat is in that State and no discrimination is to be made between [Utah and Wyoming residents] . . . in applying the [four classes under the] regulations." [149]

In practice, the creation of new reserves caused difficulty because the application of grazing regulations disrupted customary grazing operations, particularly for transient sheep. Prior to the grazing season in 1902, for instance, proclamations added more than 6 million acres to the reserve system. Two enlarged reserves—the Teton and Yellowstone—included more than half of that area. As a result, the Forestry Division agreed generally to allow customary grazing patterns to continue. [150] On the Teton extension, however, Supervisor W. Armor Thompson and Special Superintendent Anderson reported that stockmen had trailed in sheep, cattle, and horses, and that owners were transporting livestock from Texas and New Mexico. Hermann wanted to keep the sheep off the range, but President Roosevelt ordered the supervisor not to interfere for a year. [151]

The pre-existing conflict between cattlemen and sheepmen in the area created additional difficulty. Sheepmen wanted continued access to grazing grounds and cattlemen wanted them kept off the reserve. As a temporary expedient in 1903, the GLO agreed to open to sheep the portion of the recent addition not obviously needed either for timber or to protect the watersheds. [152] In 1904, 282,000 sheep grazed on the combined Yellowstone Reserve. [153]

The number of sheep seeking pasture on the Uintah Reserve was variously estimated at 300,000 to 2 million. The GLO agreed to allow only 200,000. [154] The reductions coupled with the preference categories established in 1902, effectively eliminated some including transient herds. In 1903, for instance, Supervisor Marshall reported that he had petitions for 300,000 sheep. He would allow only 200,000 to graze, and he excluded some Wyoming ranchers. Furthermore, other things being equal, the Forestry Division gave a preference to those who had been grazing in the recent past. [155] By 1904, the Uintah had been reduced to 124,995 sheep. [156]

In addition, the GLO began to eliminate common use between sheep and cattle. In 1902, for instance, in response to a petition of citizens from Summit County, they reserved a portion of the Uintah Reserve for cattle. [157] On the Uintah Reserve, the Interior Department allowed 10,000 cattle and horses in 1903 on specified allotments. [158]

The tendency to allow concerns over economic welfare to outweigh potential environmental damage caused considerable difficulty. A 1902 investigation of the Payson Reserve by Inspector Langille showed that Supervisor Bucher had allowed sheep where none were to have been permitted and that they had created "the appearance" of "utter destruction and injury." [159] For 1903, Langille recommended no sheep and only 1,000 cattle. An appeal by Bucher, supported by his replacement Dan S. Pack, argued that it "would be impossible to keep [the nearby livestock] . . . out." This led to the approval of 5,500 cattle and horses and 30,000 sheep. [160] On the Grantsville Reserve, Albert Potter had recommended no more than 2,000 horses and cattle and no sheep. His recommendation with regard to the sheep was observed, but 2,500 horses and cattle were allowed. [161] On the Aquarius Reserve, however, Inspector R.H. Charlton recommended 12,500 cattle and horses, but only 10,617 were admitted. [162] By 1904, in spite of Charlton's recommendation that none be allowed, however, 75,000 sheep grazed on the Aquarius. [163] On the Logan Reserve, Charlton at first recommended 25,000 head of sheep and 7,000 cattle and horses. The GLO disregarded this recommendation as well, but the final number was lower than had previously grazed. [164] Since the Pocatello Reserve had been created to protect the water supply, no sheep and only 482 cattle and horses were allowed to graze. [165]

In retrospect, Pack and others were probably right in recognizing that it was difficult to control stockmen's access to the reserves, at least until attitudes disregarding damage to the land changed. Stockmen had access to congressmen who could in turn influence the Interior Department not to reduce numbers if the reductions caused what they perceived to be economic hardship. In 1901 a southern California Federal district court ruled that regulations restricting access were an illegal delegation of legislative authority to the executive. [166] On the Fishlake reserve in early 1903 a Federal court in Utah ruled the same way in the case of U.S. v. Martinus. On the Fishlake, Frank Martinus brought his sheep into the reserve after Supervisor C.T. Balle had ordered him not to do so. Martinus had financial backing from the Utah Wool Growers Association, which opposed the rule forbidding sheep from grazing on the reserve while cattle and horses were allowed to do so. [167]

Following the Blasingame decision, the Justice Department recommended that forest supervisors secure injunctions through civil suits rather than charging criminal trespass. [168] The Federal courts declared the use of injunctions valid in the Dastervignes case in 1903, but such injunctions were difficult to secure. They seem to have had some effect since Pack secured one on the Payson reserve in 1903. [169]

Perhaps the worst grazing conditions existed on the Manti reserve. Sanpete residents claimed that a million head of sheep had used the range before the reserve was created. In general, as with other sheep in Utah, they trailed from the west desert where they spent the winter onto the Wasatch plateau to graze during the summer. Some passed on into Idaho, Wyoming, or Colorado, and some went on to the east desert. In addition, transient herds trailed through the Manti into the east desert. [170]

On the basis of Potter's evaluation and a subsequent investigation by R.H. Charlton, the GLO recommended in 1903 that 100,000 sheep and 15,000 cattle and horses be allowed on the Manti. Protests from local citizens and Senator Reed Smoot and a reconsideration by Albert Potter led to a recommendation of 175,000 sheep. Further pressure led to the approval for 1904 of 19,500 cattle and horses and 300,000 sheep. [171] Supervisor Jensen and his rangers had a great deal of difficulty keeping herds within even these seemingly generous limits. [172] The one redeeming feature on the Manti reserve was the absolute closing of the forks of Manti Canyon to protect the city's water supply. [173]

Perhaps the most salutary effects of grazing regulations under the Forestry Division were the imposition of quotas on number of animals allowed on the reserves and the closing of some extremely fragile areas like Manti Canyon. Although the permitted numbers were still large, by present standards, they were generally quite reduced from previous usage.

Other Aspects of Forest Reserve Administration

Special uses on the reserves covered a broad range of activities. Applications included constructing wagon roads, establishing road houses, hotels, and stores, and cutting hay. A number of reservoirs and canals were located on the forest reserves, subject to regulation by the forest officers and approval by the Interior Department. [174] Logan, UT, got permission to operate a power plant, including the dam and canal facilities, on the Logan Forest Reserve. [175] Boulder UT, erected a schoolhouse on the Aquarius Reserve. [176] The Teton Telephone Company constructed and operated a telephone line through the Teton Reserve. [177] The GLO also approved an application to operate an art studio on the Teton reserve. [178]

On the average, perhaps half of the petitions were granted. [179] The Interior Department rejected some applications, usually on the ground of lack of public need or because the applicants proposed an exclusively private use believed to be inconsistent with the public lands. A proposal to establish a "public stopping place" on the Uintah Reserve near Vernal, UT, was denied. [180] The Department also disapproved a private hunting and fishing resort at Big Springs, ID. [181]

Often, individuals and cities did engineering work under special use permits. This was especially true of road construction. [182] On the Manti reserve, for instance, until December 1904 only 4 miles of road and an enclosure were constructed by forest officers; private parties had constructed virtually everything else. [183]

Rangers did some engineering work on the reserves, but there appears to have been no contracting. Perhaps the major work done by forest officers was in helping to set some survey corners. [184] Officers did some work in clearing old trails and building new ones, constructing fire breaks clearing debris from roads, and building bridges. [185]

While the GLO perceived overgrazing and timber depredations to cause considerable damage, Forestry Division officials saw fire as the paramount danger, "in comparison with which damage from all other sources is insignificant." [186] An 1897 act was designed to help in the prevention of forest fires by authorizing the forest officers to post fire warning signs throughout the reserves and to investigate and report on the origin of fires. [187] By 1899, the GLO had developed a system of fire classification, including three classes: 1. small fires (usually campfires left unattended); 2. fires which had gained considerable headway; and 3. large fires requiring an extraordinary effort to extinguish. [188]

By 1901, the GLO had issued specific regulations for handling fires and had begun keeping records. Although the GLO did not authorize rangers to spend any money in fighting fires, they were expected to take "intelligent and prompt action," then to notify the supervisor who was to arrange for payment. The statistics gathered in 1901 indicated that fires caused by campers and hunters were the largest single group. Next were locomotive and engine sparks. [189] In 1901, the USDA Forestry Bureau began an extensive study of the relationship between forest fires and reproduction. [190]

Fire conditions in Region 4 were not particularly good, though they were not as bad as some other areas. In 1902, Albert Potter found a number of areas in the region which had been burned. [191] Perhaps 1903 was the worst fire year during the period of GLO administration, since large fires on the Teton and Uintah Reserves burned 32,600 and 6,500 acres. [192]

Supervisors were expected to use their ingenuity in fighting fires. In 1903, John Squires, supervisor of the Logan Reserve, complained that the only firefighting equipment he started with was a wet blanket. Quite inexperienced—he had been a barber for the past 35 years—he turned to the GLO manual. There he learned that he could use $200 to purchase tools and hire firefighters. After the outbreak of a large fire, he gathered an untrained crew from the Logan LDS Fifth Ward and left for the fireline. Fortunately for the neophyte smoke chasers, a rainstorm quenched the fire. Squires seems to have spent the bulk of this time in connection with that fire in securing the money to pay the firefighters. [193]

Although the proclamation of a reserve generally suspended all except pre-existing claims, it did not affect mining. The Organic Act had specifically prohibited the Federal Government from stopping "any person from entering upon such forest reservations for all proper and lawful purposes, including that of prospecting, locating and developing the mineral resources thereof." Thus, mining on the forest reserves went on as before. [194]

Another area of importance on the reserves under the GLO was the interrelated topics of recreation and wildlife management. In his 1891 report Bernard Fernow said that the forests should be objects of interest and places of "retreat for those in quest of health, recreation, and pleasure." Forest management, he said, "does not destroy natural beauty, does not decrease but gives opportunity to increase the game, and tends to promote the greatest development of the country." [195]

By about 1900, the number of wildlife in the Western United States had deteriorated to perhaps its lowest point. As indicated in Chapter 1, certain areas were particularly hard hit. Catfish and carp tended to replace trout, because they could tolerate warm murky waters. [196] Hunting for hides, disregard of game regulations, and range depletion led to the decline of big game herds, especially in Utah. [197] Settlements in the Teton Basin and Jackson Hole occupied the former winter range of large elk herds. It was estimated that in the winter of 1897-98, "a thousand died from starvation in Jackson Hole." [198]

The GLO responded to the game problem. By an act of 1899, forest officers were directed to "aid in the enforcement" of laws "in relation to the protection of fish and game." The Commissioner ordered forest officers to do everything possible to cooperate in prosecuting offenders, and in one case dismissed a forest ranger for violating State game laws. [199] A legal opinion held, however, that States had jurisdiction and that Federal officers could assist, not regulate. [200]

Local citizens showed a considerable interest in recreation and wildlife. Camping and summer resorts had developed in various canyons along the Wasatch Front, [201] and campers ascended to the wilderness of the Uinta Mountains. [202] An enterprising madam even brought her girls to Hatties Grove in Logan Canyon. [203] Sportsmen's clubs in cities like Logan began to press for the enforcement of game laws and the promotion of recreational activity. [204]

In summary, by the time the GLO Forestry Division relinquished control of the forest reserves to the Forestry Bureau—renamed the Forest Service—in 1905, it had accomplished a great deal. It carried basic responsibility for setting patterns of resource management. Beginning with the establishment of the reserves, it succeeded in addressing—though not in solving—problems such as wasteful logging practices, excessive numbers of livestock on the reserves, the stabilizing of nearby communities by excluding transient herds, and the protection of watersheds. In setting these patterns, GLO personnel worked closely with USGS and Forestry Bureau employees.

Moreover, the GLO established the basic organization assumed by the Forest Service in 1905. Forestry Division personnel were generally industrious and competent. Recent research by Michael McGeary indicates, however, that many of the supervisors and inspectors who transferred to the Forest Service with the reserves left the organization within a few years. Moreover, the Forest Service grew very rapidly in its early years, leaving those who remained from the Forestry Division in a minority. [205] Nevertheless, the GLO Forestry Division established patterns, some of which have continued to the present.

|

| Figure 12—Boundary posting and surveying party of Geological Survey before 1910. |

Reference Notes

1. Paul W. Gates and Robert W. Swenson, History of Public Land Law Development (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1968), p. 550.

2. Thomas G. Alexander, A Clash of Interests: Interior Department and Mountain West, 1863-1896 (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1977), pp. 80-81; Annual Report of the Commissioner of the General Land Office for the Year 1878, pp. 117-119. Hereinafter, these reports will be cited as General Land Office Report with the pages. Ibid., 1879, pp. 556-61.

3. General Land Office Report, 1879, p. 28; ibid., 188 1, pp. 370-704.

4. Alexander, Clash of Interests, pp. 81-82; Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior, 1880 3 vols. (Washington: GPO, 1880) 2:550. (Hereinafter, these reports will be cited as Interior Department Report, volume [if any]: pages.

5. Gates and Swenson, History of Public Land Law, pp. 554-55.

6. Alexander, Clash of Interests, p. 82; General Land Office Report, 1885, p. 235.

7. Interior Department Report, 1883, 2:248-49.

8. General Land Office Report, 1885, p. 235-36.

9. Alexander, Clash of Interests, pp. 82-83.

10. Cited in Alexander, Clash of Interests, p. 91.

11. Leonard J. Arrington, The Changing Economic Structure of the Mountain West, 1850-1950 (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1963), p. 43.

12. General Land Office Report, 1879, p. 20.

13. General Land Office Report, 1878, p. 296.

14. Alexander, Clash of Interests, p. 83.

15. Interior Department Report, 1886, p. 29.

16. Alexander, Clash of Interests, p. 81.

17. Lawrence Rakestraw, A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest (New York: Arno Press, 1979), pp. 14-15.

18. Interior Department Report, 1889, p. 587.

19. Interior Department Report, 1890, p. 408.

20. Gates and Swenson, History of Public Land Law, pp. 485, 550-52; Gates is quite negative on both the Timber Cutting Act and the Timber and Stone Act. For an alternative view, which seems to reflect positive western opinion on the acts, see: Alexander, Clash of Interests, p. 81.

21. Sherry H. Olson, The Depletion Myth: A History of Railroad Use of Timber (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), p. 71; John Ise, The United States Forest Policy (New York: Arno Press, 1920), p. 31.

22. Ise, Forest Policy, pp. 22-32: Michael Frome, The Forest Service 2nd ed. (Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1984), pp. 13-14; Harold K. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service: A History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976), pp. 11, 13, 15, 18.

23. Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, pp. 11-13.

24. Frome, Forest Service, pp. 14-20; Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, pp. 12-13.

25. Olson, Depletion Myth, p. 32.

26. Interior Department Report, 1879, 1:28-29, 2:418-20: 1880, 2:528.

27. Interior Department Report, 1880, 1:581.

28. Olson, Depletion Myth, pp. 30-33.

29. Olson, Depletion Myth, pp. 33-35.

30. Olson, Depletion Myth, pp. 43-47, 52-53, and 181.

31. Ise, Forest Policy, pp. 67-68.

32. Steen, Forest Service, pp. 41-42; Report of the Chief of the Division of Forestry in U.S., Department of Agriculture, Annual Report of the Secretary of Agriculture (Washington: GPO, 1893, p. 313. Hereinafter cited as: Report of the Forester in Agriculture Department Report until 1905 when they will be cited as Forest Service Report in Agriculture Department Report until 1927 when the Brigham Young University Library begins the separate series and they will be cited as Forest Service Report.) Note: with the 1902 report, the title of the agency was changed to "Bureau of Forestry." In 1905 it was changed again to "Forest Service," the title it has retained to the present. From 1899 through the 1934 report, the title of the report was Report of the Forester, from 1935 through 1976, the report was titled Report of the Chief of the Forest Service, from 1977 to the present it has been titled Report of the Forest Service.

33. Steen, Forest Service, pp. 26-27; Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, pp. 19-22: Frome, Forest Service, p. 14.

34. Steen, Forest Service, pp. 27-28; Frome, Forest Service, p. 14.

35. General Land Office Report, 1893, pp. 78-79.

36. Compare 26 Statutes at Large 1093 (1891) and 20 Statutes at Large 80 1878.

37. See various annual reports of the General Land Office from 1883 through 1896.

38. General Land Office Report, 1891, p. 329.

39. General Land Office Report, 1892, pp. 46, 392: 1893, p. 76.

40. General Land Office Report, 1895, pp. 85 and 402.

41. Charles Woolfenden to Commissioner of the General Land Office, October 2, 1894, Interior Department, Lands and Railroads Division, letters received, RG 48, National Archives, Washington, D.C. (hereinafter cited as ID, L and R, letters received): Silas W. Lamoreaux to Secretary of the Interior, October 9, 1896, ibid.

42. J.L. Anderson, Special Report of Timber Cut from Mineral Land, May 21, 1895; Anderson to Commissioner GLO, September 26, 1895; and P.O. Puffer, H. Harry Harris, and George H. Leonard, Mineral Affidavit, September 14, 1895, ID, L and R, letters received.

43. Lamoreaux to Secretary of the Interior, October 9, 1896, ID, L and R, letters received.

44. J.W. Judd to Judson Harmon, February 15, 1897, ID, L and R, letters received.

45. Binger Hermann to Secretary of the Interior, March 26, 1897, ID, L and R, letters received.

46. See for instance: Commissioner of the General Land Office to Secretary of the Interior, March 27, April 4, 6, May 29, June 4, 13, September 14, October 6, 12, 16, 23, December 7, 1896, January 30, 1897, ID, L and R, letters received.

47. See for instance: Commissioner of the General Land Office to Secretary of the Interior, May 18, 23, July 9, 20, 31, 1896, ID, L and R, letters received.

48. Steen, Forest Service, pp. 29-30; Edward A. Bowers to Secretary of the Interior, May 10, 1894, in Interior Department Report, 1894, p. lxxix.

49. Edward A. Bowers to Secretary of the Interior, September 25, 1893, in Interior Department Report, 1894, p. lxxx; ibid., p. 95.

50. Lamoreaux to Secretary of the Interior, February 7, 1896, with attachments ID, L and R, letters received. The attachments include a copy of the McRae bill marked by Lamoreaux and other correspondence.

51. Interior Department Report, 1895, p. xxii.

52. Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, p. 60.

53. Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, p. 65; Ivan Sack, "History of the Toiyabe National Forest," 1897, n.d., Historical Files, Supervisor's Headquarters, Toiyabe National Forest, Sparks, Nevada. (Note: Each Forest Supervisor's headquarters had its own files including some historical files. Hereinafter, instead of the long citation, I will merely cite the name of the forest. In this case, then, the citation would be: Historical Files, Toiyabe).

54. David R. Francis to Grover Cleveland, February 6, 1897, with enclosures, ID, L and R, letters received; see also Steen, Forest Service, pp. 32-33.

55. Ise, Forest Policy, pp. 131-34.

56. Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, p. 61.

57. Ise, Forest Policy, pp. 137-40; Steen, Forest Service, pp. 134-36; "Remarks of Members of the Forestry Commission before the Honorable Secretary of the Interior," April 5, 1897, ID, L and R, letters received; Rakestraw, Pacific Northwest, p. 57.

58. Lee Mantle and Frank J. Cannon to the President March 18, 1897, ID, L and R, letters received.

59. Charles D. Wolcott to Secretary of the Interior, January 31, 1898, ID, L and R, letters received.

60. Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey, 1897-98 6 parts (Washington: GPO, 1898), 5: 191-211. Hereinafter, these reports will be cited in this form: Geological Survey Report, 1898, 5:191-211.)