|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 3

The Beginnings of Forest Service Resource Administration in the Intermountain West: 1905 to 1909

Transfer From Interior to Agriculture

As early as 1899 the McKinley administration had considered transferring the forest reserves from the Interior to the Agriculture Department. [1] Early in 1901, the House Agriculture Committee debated the transfer, but the matter came up too late for floor consideration. In the absence of congressional action, the departments worked out a formal agreement for a division of labor by which the GLO administered the reserves, the Forestry Bureau directed the technical aspects of investigation and planning, and the USGS made surveys. [2]

In December 1901, Interior Secretary Hitchcock formally recommended the transfer. A 1902 bill proposed to effect the change, reserve by reserve, as the boundaries were surveyed and land claims settled. GLO Commissioner Hermann and several congressmen, including Frank Mondell of Wyoming, opposed the bill, since it seemed to them to promote duplication of effort, and, although both Secretaries and the President supported the bill, it did not pass. [3]

By early 1905, conditions had changed. William A. Richards of Wyoming had replaced Hermann as commissioner; many in the West, particularly those in mining and grazing, and Mondell, favored the transfer. [4] Many had come to realize that the existing arrangement fragmented responsibility while joining administration and expertise in a single department would overcome this deficiency. [5] With this support, on February 1, 1905, President Roosevelt approved the transfer of all functions except cadastral surveys and land disposal. On July 1, the Bureau of Forestry became the United States Forest Service. [6]

The popular appeal of the Forest Service grew, in part, because Pinchot supported resource use under utilitarian conservation rather than preservation as game reserves or public playgrounds. In various addresses and most particularly in a letter which he wrote for Agriculture Secretary James Wilson's signature outlining his duties as Chief Forester, he emphasized that "the resources of forest reserves are for use . . . under such restrictions only as will insure the permanence of these resources." Moreover, he wrote, "the continued prosperity of the agricultural, lumbering, mining, and livestock interests is directly dependent upon a permanent and accessible supply of water, wood, and forage, as well as upon the present and future use of these resources under businesslike regulations, enforced with promptness, effectiveness, and common sense . . . Where conflicts exist they must be decided for the greatest good of the greatest number in the long run." [7]

Creation of New Reserves

Creation of reserves accelerated under the Forest Service. Between 1905 and 1907, when they were redesignated "National Forests" the acreage in the United States increased two and a half times, from 63 million to 151 million acres. [8] Although this growth may seem excessively rapid, much of it consisted of completion of work begun under the GLO.

Many of the reserves in Utah derived from proposals based on the Potter survey of 1902 or on local initiatives to protect watersheds. The best examples from the Potter group are perhaps the Sevier and Beaver. The former, proclaimed May 12, 1905, had been recommended early in 1903, but was held up apparently because of a protest by citizens of Beaver, UT, and the need to deal with State land enclosed within the proposed reserves. [9] The Beaver was proclaimed January 24, 1906. [10] The Dixie Reserve, also delayed until 1905, was established principally to preserve "the water supply of St. George and neighboring towns," and the future potential timber supply. [11] Citizens of Fillmore wanted to guard their watershed, but the GLO put this reserve on hold in 1903 at the request of the Geological Survey so Henry Gannett could complete "a comprehensive plan of dealing with the whole subject of water protection and sheep grazing in Utah." The Fillmore Reserve was not established until 1906. [12]

Many other reserves in Utah were not part of the Potter survey. These included the Vernon Reserve in Tooele County created in 1904 for watershed protection. [13] The 1906 proclamation of the La Sal Reserve resulted from an examination made by Inspector Robert R.V. Reynolds in 1904. [14] Creation of the Monticello Reserve in southeastern Utah had been considered as early as 1902, largely at the instigation of the Geological Survey, since Henry Gannett, who had explored the area with John Wesley Powell, knew it quite well. The actual proclamation in 1907, however, awaited a petition from people in the area and an examination by R.B. Wilson. [15] Delay in the creation of the La Sal and Monticello reserves apparently resulted from initial lack of interest on the part of most people and opposition from sheepmen in the region.

A number of reserves in Idaho were created to protect watersheds and regulate grazing, and only incidentally to protect timber lands. A 1905 addition to the Yellowstone Reserve above the Teton Basin and Swan Valley and the designation of the Henrys Lake, Cassia, and Challis reserves are examples. [16]

The old Sawtooth, Weiser, and Payette reserves were originally examined by Forestry Bureau personnel in 1904. Although protection of stockmen from "alien" sheep and overgrazing with its consequent watershed and forest damage were primary motives, the examiners also recognized the timber production potential. Cutover forests on the Weiser were reported "in a very poor condition," [17] while acquisition of "timber lands for speculation" had begun to threaten the remaining uncut timber areas and the Forest Service feared that the results "would be most unfortunate for future consumers in the surrounding valleys and especially so for the resident miners." [18] The Payette Lumber Company, a Weyerhaeuser subsidiary, had acquired or leased timbered foothills above Long Valley. [19] The proposed Sawtooth Reserve contained more than 1.3 million acres of commercial forest. [20]

The reserves of Nevada were created principally to protect watersheds from overgrazing or to promote an orderly use of scarce pinyon and juniper needed for mining. A report by Franklin W. Reed on the proposed Ruby Mountain Reserve in 1905 emphasized the importance of watershed protection and the virtual lack of any commercial timber. [21] Reports on the Monitor and Toiyabe reserves emphasized the need to regulate use by mining companies to prevent "friction that may arise from such source." [22] In 1906, an estimated 96,000 transient sheep ranged the length of the Toiyabe Range, eliminating access by local ranchers. [23]

As executive proclamation of the reserves continued, people in the West divided sharply on Forest Service management practices. [24] Generally favoring Pinchot's approach, which included conservation coupled with development and consideration of state interests, were senators such as Reed Smoot of Utah, Francis E. Warren of Wyoming, Key Pittman of Nevada, and Fred T. Dubois of Idaho. Senators opposing virtually all FS regulation included Weldon B. Heyburn of Idaho, John F. Shafroth of Colorado, and Clarence D. Clark of Wyoming.

As chief spokesman for the opponents, Heyburn attacked Pinchot and the policy of withdrawing lands for forest reserves. Denying that the volume of timber was diminishing, Heyburn argued that these forests ought to be open to unrestricted access. These lands belonged to all the people, Heyburn said, and the Federal Government had no right to limit use.

Smoot on the other hand feared destruction of timber resources through indiscriminate use. Free use, he pointed out, had destroyed forests in States like Wisconsin. Smoot agreed with Pinchot that the policy of controlled access provided businesslike and economical management.

A clear division came in consideration of the Agricultural Department Appropriations Act of 1907. The Delegations of Oregon, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado insisted upon enacting an amendment prohibiting the President from creating any forest reserves in their States without congressional approval. He could still proclaim reserves in Utah, California, Washington, and Nevada without such concurrence.

Decentralization and Reorganization

As the Forest Service continued the creation of forest reserves within Region 4 it also took steps toward greater decentralization. In 1906, after consultation with Henry Gannett, Frederick E. Olmsted, and others, Pinchot decided to organize the field service into inspection districts. He announced that as rapidly as possible the service expected to reduce the duties of the Washington Office to those of general administration, scientific investigations, inspections, and record keeping. [25] The 1906 configuration included three districts, each headed by a chief inspector. They were: the Northern, including national forests in Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, South Dakota, and Minnesota; the Southern, including national forests in Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, Nebraska, and Oklahoma; and the Western, including forests in Washington, Oregon, California, and Alaska. At the same time he created an inspection section in the Washington Office. Inspectors in charge of the districts reported directly to the Chief Forester. Inspectors conducted supervisor's meetings and assessed and reported on the efficiency and integrity of personnel. [26]

In 1907, the Service expanded the number of inspection districts to six. Headquarters were located at Missoula, Denver, Albuquerque, Salt Lake City, San Francisco, and Portland. District 4 with headquarters at Salt Lake City had jurisdiction over southern Idaho, western Wyoming, eastern Nevada, Utah, and northern Arizona. [27]

While his principal responsibility was inspection, Chief Inspector Raymond E. Benedict at Salt Lake City also worked with supervisors and proposed new forests and reorganizations of existing national forests within the district. The final decisions in each case were made by Pinchot. [28] Benedict also worked with forest supervisors in public relations efforts, such as holding meetings to promote understanding between communities and the Forest Service. [29]

Working under Washington's instructions, Benedict began the reorganization of the national forests within the region. The first steps included placing adjoining small forests under a single supervisor, and dividing some of the larger forests for administrative efficiency and convenience (Table 3). [30]

Table 3—Configuration of Inspection District 4 at its reorganization in 1907

| Unit or National Forest | Headquarters | Inspector or Supervisor |

| Inspection District 4 | Salt Lake City, Utah | Raymond E. Benedict (Chief Inspector) |

Arizona | ||

| Grand Canyon (North) | Fredonia | Selden F. Harris |

| Trumbull | St. George, Utah | Chas. C.Y. Higgins? |

Idaho | ||

| Bear River | Logan, Utah | W.W. Clark |

| Caribou (South) | Afton, Wyoming | J.T. Wedemeyer |

| Yellowstone (Salt River) | Afton, Wyoming | J.T. Wedemeyer |

| Cassia | Pocatello | P.T. Wrensted |

| Pocatello | Pocatello | P.T. Wrensted |

| Port Neuf | Pocatello | P.T. Wrensted |

| Raft River | Pocatello | P.T. Wrensted |

| Henry's Lake | St. Anthony | Homer E. Fenn |

| Yellowstone (Idaho) | St. Anthony | Homer E. Fenn |

| Caribou (North) | St. Anthony | Homer E. Penn |

| Lemhi (North) | Salmon | Geo. C. Bentz |

| Salmon River | Salmon | Geo. G. Bentz |

| Lemhi (South) | Mackay | Guy B. Mains |

| Payette | Van Wyck | unknown |

| Sawtooth (Boise) | Boise | unknown |

| Sawtooth (Wood River) | Hailey | Emil Grandjean |

Nevada | ||

| Charleston | Las Vegas | David Barnett |

| Las Vegas | Las Vegas | David Barnett |

| Independence | Elko | Clarence H. Woods |

| Ruby Mountains | Elko | Clarence H. Woods |

| Toiyabe | Austin | Mark G. Woodruff |

| Toquima | Austin | Mark G. Woodruff |

| Monitor | Austin | Mark G. Woodruff |

Wyoming | ||

| Yellowstone (Wind River) | Pinedale | unknown |

| Yellowstone (Teton) | Jackson | Robert E. Miller |

| Caribou (South) | Afton | J.T. Wedemeyer |

| Yellowstone (Salt River) | Afton | J.T. Wedemeyer |

Utah | ||

| Bear River | Logan | W.W. Clark |

| Aquarius | Escalante | Geo. H. Barney |

| Beaver | Beaver | William Hurst |

| Fillmore (South) | Beaver | William Hurst |

| Dixie | St. George | Chas. C.Y. Higgins |

| Fillmore (North) | Nephi | Dan S. Pack |

| Payson | Nephi | Dan S. Pack |

| Fish Lake | Salina | N.E. Smell |

| Glenwood | Salina | N.E. Smell |

| Grantsville | Grantsville | C.F. Cooley |

| Vernon | Grantsville | C.F. Cooley |

| Manti | Ephraim | Adolph W. Jensen |

| Salt Lake | Salt Lake City | E.H. Clarke |

| Wasatch | Salt Lake City | E.H. Clarke |

| Sevier | Panguitch | Timothy C. Hoyt |

| Uinta | Provo | Willard I. Pack |

| LaSal | Moab | Orrin C. Snow |

| Monticello | Moab | Orrin C. Snow |

Source: James B. Adams to R.E. Benedict, May 25, 1907, File: O— Supervision—General, 1907-1915, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC; Charles S. Peterson, Look to the Mountains: Southeastern Utah and the LaSal National Forest (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1975); and comments by Gordon Watts. | ||

The organization of inspection districts served principally as a prelude to the more extensive and thorough reorganization that took place the next year. On December 1, 1908, the inspection districts were recast into field headquarters called "districts" under the direction of a district forester. Each district was organized under substantially the same system as the Washington Office, with experts supervising the law office and four divisions: operations (including organization, occupancy, engineering, accounts, and maintenance), grazing, products, and silviculture (including timber sales, planting, and silvics). [31]

The Forest Service established headquarters for districts 1 through 3 and 5 and 6 in the cities where the inspection district offices had been located. The situation in District 4, however, was complicated because of a Washington Office decision to decentralize supply operations as well. Prior to this time, the service had purchased supplies and filled orders from the Washington office. This practice caused inordinate delay since all the national forests were then located in the Far West. It was expected that locating a supply depot at a rail point in the West would provide more efficient and prompt service.

The Forest Service administration decided to link the headquarters of District 4 with the location of the supply depot for all six districts, and the advantage of Ogden as a shipping point led to its choice as the district office. After investigating the possibility of Salt Lake City, the administration realized that delays in shipments of broken carloads would result and that some shipments would have to be rebilled. Moreover, living expenses, drayage, and storage costs were higher in Salt Lake, the city lacked warehouse space, and it had experienced a recent labor shortage. On the other hand, the railroads had designated Ogden as the starting point for shipments to the east, west, and north, and there would be no additional shipping charges. [32]

The final recommendation on district headquarters's location was left to Clyde Leavitt, then serving as chief of the Branch of Operations in Washington. [33] After an investigation, he recommended the acceptance of an offer made by Ogden businessman Fred J. Kiesel to construct a new building at the corner of Lincoln Avenue and 24th Street that could house both the supply depot and the district headquarters for 5 to 6 years, after which Leavitt expected a Federal building to be completed into which the district office could move. In the meantime, Leavitt located the office—his office, since he was appointed district forester—in temporary quarters on the fourth and fifth floors of Ogden's First National Bank building at 2384 Washington Boulevard, approximately where ZCMI is now located. [34] The arrangement with Kiesel allowed the Forest Service to set minimum construction standards and a rental price of $425 per month for 10 years on an annual lease. [35]

|

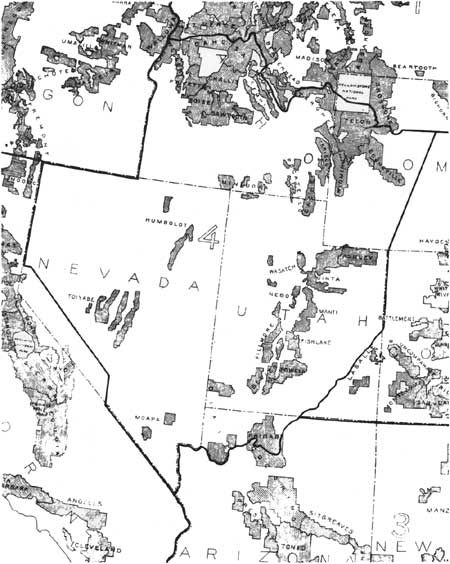

| Figure 13—Map of district 4 of the National Forest System, 1908. (click on image for a PDF version) |

Much more thoroughgoing than the organization of inspection districts, the 1908 district reorganization involved a qualitative as well as a quantitative change from the GLO system. The GLO had used an inspection system, but under the Forest Service system all correspondence, reports, and papers that supervisors previously sent to the Washington Office were handled at district headquarters. Moreover, the district foresters, unlike the inspectors, could exercise considerable administrative discretion without Washington Office clearance. In order to facilitate this, administrative and financial records and clerical force were transferred from Washington to the districts. [36]

At the same time, the Service continued the rationalization of its local organization, begun under the inspection district system, by combining forests, transferring some between regions, and changing forest headquarters (table 4).

Table 4—Configuration of District 4, 1908

| National Forest | Former Names | Headquarters | Supervisor |

| District 4 | Ogden | Clyde Leavitt (District Forester) | |

| Idaho | |||

| Weiser | Payette (north) | Weiser | J.B. Lafferty |

| Payette | Payette (south), Weiser, | Meadows | H.A. Burgh |

| Sawtooth (west) | H.A. Burgh | ||

| Boise | Sawtooth (southwest) | Boise | Emil Grandjean |

| Challis | Sawtooth (northeast), Salmon | Challis | David Laing |

| Salmon | Lemhi (north and south) and Sawtooth | Salmon | George G. Bentz |

| Sawtooth | Hailey | Clarence M. Woods | |

| Lemhi | Mackay | C.L. Smith | |

| Targhee | Henry's Lake (north) | ||

| Yellowstone (Idaho) | St. Anthony | Homer E. Penn | |

| Teton (Palisade?) | Henry's Lake (south) | St. Anthony | Homer E. Fenn |

| Caribou | Caribou (north and south) | Idaho Falls | J.T. Wedemeyer |

| Cache | Bear River (except Malad Division) | Logan | M.G. Woodruff |

| Pocatello | Pocatello, Port Neuf, Bear River (Malad Division) | Pocatello | P.T. Wrensted |

| Minidoka | Raft River, Cassia | Oakley | William McCoy |

Nevada | |||

| Humboldt | Ruby Mountains, Independence | Elko | C.S. Tremewan |

| Toiyabe | Toiyabe, Toquima, Monitor | Austin | D.L. Barnett |

| Moapa | Charleston, Vegas | Charleston | H.E. Matthews |

Wyoming | |||

| Yellowstone (Teton) | Yellowstone (north Teton Division) | Jackson | Robert E. Miller |

| Bonneville* | Yellowstone (Wind River Division) | Pinedale | Jones? |

| Wyoming | Yellowstone (south Teton Division) | Afton | John Raphael |

Utah | |||

| Cache | Bear River | Logan | M.G. Woodruff |

| Wasatch | Salt Lake, Wasatch, Grantsville | Salt Lake City | E.H. Clarke |

| Uinta | Uinta (west) | Provo | Willard I. Pack |

| Ashley | Uinta (east) | Vernal | William M. Anderson |

| Nebo | Payson, Vernon, Fillmore (north) | Payson | Dan Pack |

| Manti | Manti (north) | Ephraim | A.W. Jensen |

| Fillmore | Fillmore (south), Beaver | Beaver | William Hurst |

| Fishlake | Fish Lake, Glenwood, Manti (south) | Salina | N.E. Smell |

| Powell | Aquarius | Escalante | G.M. Barney |

| Sevier | Panguitch | Timothy C. Hoyt | |

| Dixie | Dixie, Trumbull | St. George | C.G.Y. Higgins |

| La Sal | La Sal, Monticello | Moab | John Riis |

Arizona | |||

| Dixie | Grand Canyon (north) | St. George, Utah | C.G.Y. Higgins |

| Kaibab | Trumbull | Kanab, Utah | W.W. Clark? |

*Transferred to District 2, 1909. Source: Memo for OB, April 24, 1908, File: 1680 History—Historic Documents—Washington Office Changed Administrative Units, 1908, Challis; Overton Price to Clyde Leavitt, May 10, 1909, File: O— Supervision— General, 1907-1915, Regional Office Records, KG 95, Denver FRC. Rationalized on the basis of comments by Gordon Watts. | |||

In addition to shifting their line of accountability from the Washington Office to the district forester, the decentralization had some impact on the work of supervisors and rangers as well. Paperwork increased, both for supervisors and rangers, as they worked on surveys for administrative withdrawals and tried to settle range disputes. Supervisors became more responsible for policy judgments. [37] Previously, supervisors had worked with the chief inspector in making recommendations on pay, but, with the change, they made the recommendations to the district forester themselves, after which he exercised his judgment. [38]

Rangers' duties changed and expanded. Previously they were assigned to districts organized along the line of the grazing allotments. With decentralization they worked on trails, roads, and fences, built ranger stations, strung telephone lines, and fought fires. Under the GLO they had done little timber management, since all sales had been made on application of private parties, and the Forestry Bureau had drafted working plans. Under decentralization, they drafted their own timber sales plans after conducting a timber reconnaissance.

Duties, Salary, and Training

Rangers, at that time, were expected to furnish their own board and lodging, plus their horses, saddle, pack outfits tent, and wagons and harnesses when necessary. [39] One estimate set the annual expenses for all these items at between $400 and $485 per year. Most rangers who talked in retrospect about the system said their salaries were about $60 per month or $720 per year; however, records indicated the salaries ranged from about $900 per year for an assistant forest ranger to $1,200 for a ranger. A deputy forest supervisor earned $1,300 to $1,400 per year, the supervisor got $1,600, and the clerk earned $1,000 per year. Orrin C. Snow believed that the salaries compared "favorably, or probably exceeded slightly that which could he earned by each working for wages outside the Service, except in the case of rangers who are on a salary of $900 per annum." The reason for the exception was that, since rangers had to work full time in the field during the summer, they could not operate another business on the side as many others with similar capabilities did. [40]

Since most supervisors, deputies, and rangers joined without prior formal training, the Service took measures to educate them. In 1909, of 192 supervisors and deputies in the entire Forest Service only 48 or 25 percent had any technical training. The percentage among rangers seems to have been even lower. In order to provide needed expertise, the Service instituted a short course in forestry at Utah State and Colorado State agricultural colleges in 1908 and at the University of Washington in 1909. [41] In 1908, also, the Service began 5-week in-service training sessions in Washington, DC. [42]

Typical of the minority who entered the Service with some training were a number of foresters from District 4. J. Wells Robins, born at Scipio, ran cattle in the Sevier River area and on the Arizona Strip before moving to Ogden to work in a feedlot. He left for a proselytizing mission for the Mormon Church, then returned to take the short forestry course at Utah State. After passing the examination, he was appointed to the Fishlake National Forest. [43] Better educated than most who entered, Moses Christensen had grown up in Cache Valley, the son of a Mormon immigrant family. He attended Utah State, where he majored in agriculture, before moving to the Umatilla Indian Reservation where he handled land and grazing matters and taught practical agriculture. He entered the Forest Service in 1908 on the Malad National Forest. [44] Carl Arentson had spent 5 months in business college and taken correspondence courses in surveying, bookkeeping, and range management before joining the staff on the old Payette. [45] Emil Grandjean was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, to a family of foresters, and he had studied forestry under tutors. [46]

Since the number of employees grew rapidly under the Forest Service, most supervisors and deputies had not worked for the GLO. Those like Clarence N. Woods and Adolph W. Jensen, who transferred from the GLO Forestry Division to the Forest Service, were the exception. Nevertheless, most new recruits had similar backgrounds. Most had some livestock experience, like Orrin C. Snow, who became supervisor of the La Sal National Forest. Or they had done some ranching and logging like William M. Anderson, first supervisor of the Ashley National Forest. [47] It should be noted, however, that turnover in the early years of the Forest Service was comparatively high.

Entrance into the Forest Service came after passing an examination that emphasized practical knowledge. Carl B. Arentson remembered applying to Guy B. Mains for a ranger's job. Mains asked him for references from at least three men who knew of his good reputation and experience in handling livestock. [48] C. Syd Tremewan indicated that the written examination lasted 2 to 3 hours. The practical portion was much longer—candidates had to pack a horse using swing and diamond hitches, demonstrate the use of a compass and elementary surveying, and prove cooking skills. Tremewan had to estimate the number of telephone poles that could be cut from an acre of Nevada pinyon-juniper. Given the small size of most such trees, this was no mean feat. "Some of the answers," Tremewan said, "were really ridiculous." [49]

In the early years, promotions came very rapidly for competent personnel. William R. Hurst rose from assistant ranger to forest supervisor in 2 months. [50] David Laing, a temporary forest guard in September 1905, was supervisor of the Challis National Forest by 1908. [51] Leon F. Kneipp, a man from the Chicago waterfront with no forestry training and little formal education, became district forester in 1915 at age 26 after serving as assistant chief of the grazing division in Washington. [52]

Virtually all employees during the early years were males of northern European extraction. Beauregard Kenner hired a couple of Native Americans, but Inspector Benedict fired them. Few Mexican-Americans, Orientals, or southern Europeans found positions. There were a number of immigrants, but like Grandjean of Denmark and John E. Squires from Scotland, virtually all were from northwestern Europe. [53] Some women were hired as clerks, but none held senior positions. More typical was Margaret Jensen of Mendon, UT, clerk of the Cache National Forest for 20 years starting in May 1907. [54]

The staff of the Sevier National Forest in 1909 seems to have been fairly typical. The forest had 10 salaried employees including the supervisor, deputy, and clerk in the supervisor's office, and two rangers, two deputy rangers, and three assistant rangers on the six ranger districts. Supervisor Snow used one of the deputy rangers in what today would be considered a timber staff position. Of the staff all except the clerk had been stockmen, two had worked in lumbering, and one had been in clerical work before entering the Service. Two still owned property and livestock outside the forest. Most were good workers, though two were deficient in clerical ability and education and did not do well with paper work. [55]

Many rangers and their families lived a hard life, but probably not harder than others living in the back country during the early twentieth century. The Dixie National Forest reported difficulty in finding rangers willing to work on the Trumbull division on the isolated Arizona Strip. [56] On some forests, the ranger might have to live in a tent, an old miner's cabin, or a log cabin he built with materials furnished at government expense. He might spend the winter snowbound with his family, and a move could become a significant adventure.

Rangers' wives served essentially as unpaid employees in addition to their household and other duties. Some worked in the communities where they lived, in some cases as postmistresses or telephone operators. For the wife, household chores resembled those of other rural women, with their sadirons, wood stoves, and washboards. In addition, however, they often had to check firefighters in or out or count sheep and cattle onto the forest. [57]

The forest supervisor's life, on the other hand, was much different. Instead of enduring the hardships of the back country, they and their families could experience the advantages of rural town or city life. Moreover, while they undoubtedly spent more time in the field than supervisors today, much of their work consisted of correspondence with the Washington Office or the district forester about such matters as the interpretation of the "Use Book" (the pocket-size manual of Forest Service procedures first published in 1905), preparing and transmitting reports, and hiring and evaluating employees. [58]

The supervisor kept card files on temporary personnel. These cards listed for each person the name, address, age, marital status, occupation, type of work, reputation, sobriety, and record in Forest Service employment. If a sample from the Caribou National Forest is representative, the supervisors were very frank in their assessment of the record. One was listed as "too heavy for light work and too light for heavy work, but mighty good with a spoon," another was said to be "poor, didn't know how to work," and a third was reported to be "good, does very good work as far as knowledge extends." [59]

Public Relations and Cooperation

A substantial part of the supervisor's time involved public relations with the forest users. On the Boise National Forest, Supervisor Frank Fenn delivered lectures on the value of the Forest Service. [60] On the Nebo, Dan S. Pack got one of his rangers to help out a disgruntled forest user with a survey so his forest homestead could go to patent. [61]

Perhaps the most important cooperation took place on the old Payette under Guy B. Mains. Between 1905 and 1908, crews from a number of lumber companies including the Payette, Boise, Barber, and A.W. Cook, together with Boise and Payette National Forest employees, had worked together a number of times in firefighting. After controlling a fire on Buck Creek in 1908, Mains and Harry Shellworth, Payette Lumber Company land agent, discussed the possibility of sharing responsibilities, the use of State fire wardens, and other related matters. By 1911, out of the discussions grew the Southern Idaho Timber Protective Association (SITPA), said to have been the third such organization in the United States, and perhaps the most successful cooperative effort in District (later Region) 4. Mains became the first president of the organization. Through SITPA's influence, State fire wardens were removed from political appointment, and areas of responsibility between the State, private owners, and the Forest Service in prevention, detection, and suppression were spelled out. [62]

Forest Policies

In managing the forests, the Service operated under a number of general policies. As outlined by Pinchot in 1908, these policies covered: 1. Protection against fire and trespass, 2. Harvesting of mature timber under policies assuring sustained yield and watershed protection, 3. Improvement of timber stands, 4. Protection of the water supply, 5. Utilization of the forest's forage crop for grazing, 6. Improvement of range conditions, and 7. Development of adequate means of housing, communication, and transportation. [63]

|

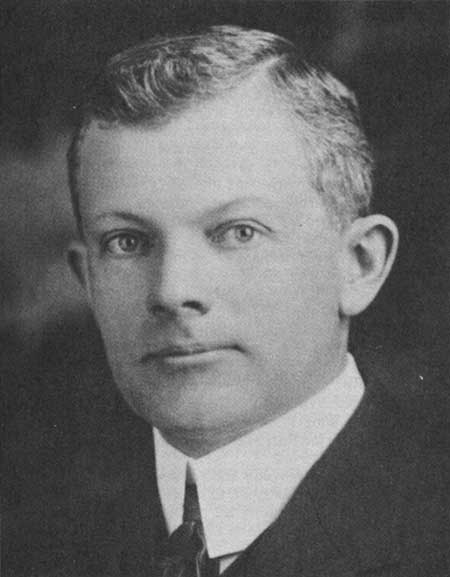

| Figure 14—P.T. Wrensted supervisor of the Cassia, Pocatello, Port Neuf, and Raft River National Forests, at the Bannock Guard station, ca. 1908 or 1909. |

From the point of view of the States, perhaps the most important pieces of legislation were the laws of 1906 and 1908 that provided for payment to the States of first 10, then 25 percent of the forest receipts. The money was to be used for public schools and roads and was perceived by the westerners as a means of compensating for tax revenues lost to the States through Federal ownership of the lands. [64]

Inspections

The district forester exercised judgment on the implementation of general policy and on evaluating the work of supervisors and their staffs. The work of inspection and recommendation previously performed by the district inspector now fell to the district forester, who became the eyes and ears of the Forest Service in its fieldwork. Since Washington had to approve many of the supervisors' proposals, they were first considered by the district forester, whose judgment carried considerably more weight than the district inspector.

|

| Figure 15—Clyde Leavitt, Regional (District) Forester, 1909-10. |

The notations on an inspection report on the Dixie National Forest that Homer E. Fenn, District Chief of Grazing, made in 1909 indicate the way in which District Forester Clyde Leavitt operated. [65] He made many decisions himself. When questions arose as to the disposition of duplicate correspondence and forms, Leavitt wrote the Washington Office for a clarification. He authorized the Dixie supervisor to secure larger quarters for his office and accepted Fenn's recommendation that no deputy supervisor be appointed at present, as none of the staff had enough experience to take the position and morale had suffered from the importation of too many officers from outside the Dixie area. He also accepted Fenn's recommendation that the current acting Supervisor be promoted to supervisor at the end of his probation.

Range Management

Grazing administration was undoubtedly the most difficult and time-consuming problem in District 4. In spite of the efforts of the GLO, overgrazing had continued in the Intermountain West and the forest officers had the unenviable task of weighing the need to protect and improve the condition of the land against the short-run economic interests of range users. The Forest Service's organizational structure and its reporting and inspection systems provided some internal cohesion and support for the supervisors and rangers in their efforts to control grazing. By 1910, however, grazing problems were far from solved.

In general, the Forest Service retained preference classes—named A, B, and C and based on base ranch holdings and distance from the national forest—much like the GLO. [66] The major modification came in an attempt to help owners of small herds. Protective limits—the number of livestock below which graziers would not be required to reduce permitted numbers—were established by each national forest, rather than for the Service as a whole. Applicants owning stock above the protective limit had to be classified as B or C, and only small owners could be class A, the most preferred. [67]

In retrospect, two things seem to have been most important in the development of patterns of range management. One was the European forestry system, inculcated by the GLO and furthered by the Forest Service under Pinchot, which included a strong emphasis on inspection and evaluation. Second, and equally important, was the capability of the district office staff, particularly Homer E. Fenn, with a background in ranching, who moved from his position as supervisor of the Targhee National Forest to serve as the first district chief of grazing during the early years of District 4.

Fenn's appointment was particularly important, since both District Forester Clyde Leavitt and Assistant District Forester Franklin W. Reed lacked experience in forest administration, though they had technical training. For his deputies, Fenn chose A.C. McCain and George G. Bentz, both of whom had worked on the ground in eastern Idaho and western Wyoming.

While Fenn was extremely competent in the administration of the district grazing division, his views did not always coincide with Service policy. Some of the differences were apparent in a meeting with the district officers and Washington Office personnel in 1909.

In Fenn's view, Forest Service grazing regulations had six purposes. These purposes were: first, to prevent injury to "stands of timber" and to avoid interfering with reforestation: second, to protect watersheds "against damage by livestock:" third, to accomplish "a complete utilization of the forage crop within the National Forests;" fourth, to prevent "range monopoly:" fifth, to avoid "unfair competition in the use of the range;" and sixth, to accomplish "a more equitable distribution of the grazing privileges." [68]

All except "the last purpose," Fenn said, had met "with the unqualified endorsement of users of the Forests." The attempt at equitable distribution had generated considerable dissatisfaction, since it brought about a reduction toward the protective limit in the herds of the larger users in favor of new permittees. This produced uncertainty for the larger users and reduced "stability and permanency" in their business operations. Moreover, because stockmen invested in base property and equipment in proportion to the number of permitted stock, a reduction in the permit size reduced "the value of their property . . . in exact proportion."

Though Fenn followed the Service's distribution policy, it was clear that he did not like it. In his view, the Forest Service ought to "confine its efforts to the regulation of grazing to prevent damage to the timber or watersheds, the prevention of range monopoly and unfair competition." Thus, he argued that "when the number of stock on the Forest has been reduced to a point where there is no further danger to the range, timbered areas, or watersheds, the Service would have done its principal duty in the administration of the grazing business."

In regulating grazing, Fenn thought that the Service ought to recognize "the regular occupant as having an equity in the range to the extent of his permit." Then, he said, "any one who wishes to secure a permit, except a new settler on new land, should be required to do so by purchase." He was "willing to defend so far as it is actually true," the proposition that under such a policy the Service was "granting to large outfits on the Forests their privilege in perpetuity," believing that if they "maintain a normal economic condition by preventing range monopoly and unfair competition in its use, the distribution of the grazing privilege" would "take care of itself."

In this connection, he objected to the policy that required the owner to provide hay from his own land for his stock during the winter in order to be eligible for a permit—the so-called "commensurability" rules. This, it seemed to him, flew in the face of the "object of the grazing Regulations," which was "to assist in the development of the country and add to the prosperity of the community in the vicinity of the Forest." If the policy were dropped, the rancher could graze his stock on winter range and "turn a neat profit" from the sale of hay he might otherwise have fed his stock.

Assistant Chief Forester Albert Potter disagreed. Forest Service policy had a social as well as an economic component. Policy included favoring the small stockman, as well as reducing the number of livestock to the carrying capacity of the range. [69] He rejected Fenn's views, believing that in accepting them the Service would have to recognize that the permittee held a property right in the range. He feared that recognizing such a right might make it difficult "to exclude stock from any of the lands" even if this became necessary for range protection. He recognized, however, Fenn's concern about keeping the "large owner continually in an unsettled state of mind as to which range he is going to be allowed to use," but considered that a less serious matter than the social purpose and range protection.

He was willing to put Fenn's views to a vote, recognizing that they represented a "change in the principle upon which our present regulations are based." The results were somewhat inconsistent. A majority of 15 to 2 believed that the Service should continue the policy of making sliding scale reductions to take care of beginning stockmen and new owners. By a majority of 10 to 5, however, they held that exceptions should be made "from reduction to the protective limit in cases where there is an unusually large investment in ranch property."

Those present then proposed a compromise by issuing 5-year term permits to the stockmen. This had the advantage of guaranteeing 5 years of stability to continuous and larger users, while allowing distribution after a 5-year term to allow new stockmen to enter. Only 2 of 17 voting—one of whom was presumably Fenn—opposed the idea of permitting reductions to help new owners at the expiration of the 5-year period. All agreed, however, on allowing reductions for silvicultural improvement and range protection even during the 5-year term. [70]

At the same meeting, E.W. Reed outlined the procedure by which the Service allowed some continuity, through a system apparently originated on the Uinta that allowed the actual—though not the legal—transfer of permits between a seller and purchaser of base property and livestock. Under the system, the seller relinquished his permit to the government and the government transferred it to the purchaser. Reed pointed out that the system had avoided a great many complaints. All agreed with Fenn's proposal that to protect against speculation and instability, the purchaser had to stay in business for 3 years before he could transfer the permit on the sale of his property.

The entire process indicated the openness of the Washington Office to suggestions and decentralization. Those present supported the Service system of having the Secretary of Agriculture designate only the maximum number of animals allowed on each national forest rather than specifying the details of distribution, which was left to the supervisor's discretion. Under the GLO system, the Interior Secretary had itemized the number in each grazing district. [71]

It is one thing to develop and review general policy in the office, and quite another to apply it in the field. Ranges throughout virtually all of District 4 were badly overgrazed and until the late 1950's, such improvements as were made were generally only relative. Nevertheless, in practice, though the forest officers had to work hard in implementing policy, they could sometimes be somewhat more successful if they could develop a good relationship with stockmen. In addition, the chances for success in relations with stockmen in District 4 were somewhat better than in some areas: unlike the situation in District 2, there is no evidence of general opposition among graziers to the imposition of grazing fees. This was, however, only a minor advantage compared with the massive problem of overgrazing. [72]

Even on some of the best ranges, the situation was extremely serious, and in retrospect, even major attempts at reduction can be perceived as little more than holding operations. More sheep and cattle grazed on the Humboldt National Forest than any other in the Intermountain District. In 1908, 560,000 sheep grazed in the northern portion of the forest on what are now the Jarbidge and Mountain City Ranger Districts. As the result of a meeting with stockmen in March 1909, Supervisor Tremewan reduced permits by 38 percent to allow 350,000 sheep, several thousand cattle, and 2,000 horses. [73]

An inspection by E.H. Clarke found that stockmen had not observed Tremewan's limits and 400,946 sheep and 41,020 cattle had actually grazed on the forest during 1909. [74] Moreover, Clarke faulted Tremewan for his distribution of the livestock. He found that the Copper Basin and Jarbidge areas had been overgrazed while some areas like the Marys River, Little Salmon, and Sun Creek were not used to their full capability. He also found difficulties with trespass on the north fork of the Humboldt.

In Tremewan's defense, it should be pointed out that stockmen were generally pleased with Humboldt administration and conditions on the Humboldt, while extremely bad, were relatively better than on other forests in the district. In general, reports indicated the stock came from the forest "in better condition than stock grazing on other areas."

In practice, however, Tremewan's recommendations promised little improvement in the future. In 1909, basing reductions on a protective limit of 5,000 sheep, Tremewan recommended the same number of sheep (350,000) as the year before and an increase to 40,000 cattle and horses for 1910. [75]

On the Wyoming National Forest, in contrast, in 1908 the forest was not only overgrazed, but public relations with stockmen were quite unfavorable as well. The forest had been separated from the Teton division of the Yellowstone in July 1908, and Teton Supervisor Robert Miller had never inspected that area. Moreover, Forest Supervisor John Raphael headed a young and inexperienced ranger force. On two of the grazing districts, stockmen failed to observe allotment boundaries, and the forest officers had not been present to see that the animals went on the proper allotments. They had succeeded, however, in separating the cattle and sheep ranges. This was sorely needed owing to the long-standing conflict between the two groups of stockmen. One hopeful sign, however, was the cooperation of the Advisory Board of the Wyoming National Forest Wool Growers Association in counting stock on to the forest. [76]

Supervisor John Riis on the La Sal paid little attention to public relations. His predecessor Orrin Snow had encouraged graziers to organize the Southeastern Utah Stockgrowers' Association in 1907. Although Riis's staff was too small to control trespass, he had apparently ignored Assistant District Forester Reed's suggestion that the association could help him. [77] Some of the outfits like Lemuel H. Redd, Carlisle and Gordon, and the Indian Creek Cattle Company exceeded permitted numbers, but Riis's obvious distrust of the stockmen's association was hardly calculated to promote good feeling. [78]

Supervisor Anderson on the Ashley, on the other hand, tried to handle his problems somewhat more astutely. He set a protective limit of 2,100 sheep per permittee and proposed plans to increase or reduce all permittees to that level. He found some difficulty in securing proper salting for cattle, but proposed specifying regulations in the permits. He developed an effective public relations and education program by working with stockmen's associations at Vernal, UT, and Lone Tree, WY, and in educating graziers on the need for permits. [79]

Problems on the Dixie were caused in part by poor range and livestock management by the stockmen. According to Homer Fenn, the Utah division was "only about one-half stocked," though it had been overgrazed in the early 1890's and scrub-oak browse had replaced the grasses. Stockmen allowed their animals to drift on the forest with "practically no attention throughout the grazing season." Salting and water improvement had been badly neglected. On the Arizona division, which Preston Nutter used almost exclusively, the situation was the worst. In one place, Fenn found water troughs "completely filled with dead cattle, and many cattle . . . choking for water." [80]

Fenn's proposals for dealing with problems on the Dixie indicate his generally practical bent of mind. In spite of his previously professed opposition to joint ventures, he proposed cooperation with the St. George Commercial Club and the Mt. Trumbull and Parashaunt Cattle Growers' Association Advisory Board in the construction of drift fences in Utah and Arizona.

On the Uinta National Forest the situation was extremely serious because a number of badly overgrazed watersheds rested above the cities of Utah Valley. By 1907, forest officers recognized that drastic reductions were necessary to protect and restore the drainages. Lambing grounds were moved from the west side of the Hobble Creek and Diamond Fork drainages to Strawberry Valley. After lambing, sheep were allowed to return for a shortened period from September 10 until late October. The range began to improve, but quite slowly because of extensive past damage. [81]

In some cases, attempts to control grazing resulted in disputes between forest officers. Supervisor Robert R.V. Reynolds of the Wasatch argued with his deputy, William M. McGhie, about overstocking on the Pleasant Grove District. McGhie believed that the permittees had done all in their power to reduce the number of stock and did not feel justified in making further reductions because they had "exhibited such a good spirit." Reynolds, however, insisted that the numbers be reduced, in order to protect the resource under his stewardship. McGhie finally agreed, but refused to accept any responsibility for recommended reductions. [82]

In general, range deterioration in Idaho, though serious on the Targhee, Challis Sawtooth, and Boise, had not been as bad as in Utah. [83] The major exception was in eastern Idaho on the Caribou National Forest. After a number of the other forests in western Wyoming and eastern Idaho were created, the Caribou area became, as Forest Supervisor John Wedemeyer put it, "the general dumping ground for sheep . . . as men [came] who could not get on reserves elsewhere or who were cut down." [84]

Wedemeyer had to hustle to keep the numbers down during 1907, since the forest had just been created. He received applications for 740,000 head of sheep, and he allowed 450,000 sheep and 12,000 cattle and horses in 1907. By 1909, he had succeeded in reducing the number of sheep to 340,000 head, at least on paper, since most of those using the forest lived in Utah or Nevada and many had no base property. [85]

Still, N.E. Snell, who replaced Wedemeyer in 1909, believed that the former supervisor had left an intolerable situation. In order to get the numbers down, Wedemeyer had induced some of the larger outfits to relinquish portions of their permits for a year with the promise that he would restore them later. Then, to help beginners, he promised new allotments. The total of 340,000 head he requested would not cover both sets of promises, so Snell had to secure special permission to allow 375,000. Contrary to Wedemeyer's previous allegations of good feelings between the permittees and the Service, Snell found himself standing "on the firing line, day and night, in defense of the Forest policy," largely because of Wedemeyer's promises and the "state of confusion," in which he found administration. [86]

Snell undertook several measures, which were undoubtedly necessary to provide successful management and to reconcile the forest users to his administration. These included the organization in August 1909 of the Caribou Sheepmen's Association, constituting its principal officers as an advisory board, and granting 5-year permits. [87]

In contrast to the situation on the Caribou, by 1909 conditions on the Weiser were perceived to be very good. Leon F. Kneipp noted few problems in an inspection of 1909. The forest was grazed principally by cattle. [88] In 1909, grazing associations were formed on the Weiser and the old Payette. [89] In some cases, the areas covered by some of the national forests seemed far too large for effective administration with the available manpower. In 1907 when Emil Grandjean took over as supervisor of what was then the Sawtooth National Forest, it included the present Boise, and parts of the present Payette, Sawtooth, Salmon, and Challis. The range was allotted to 575,000 head of sheep and 15,000 head of cattle, and Grandjean held meetings in various towns from Hailey and Mackay on the east to Payette and Boise on the west to meet with permittees. [90]

By 1909, the forest had been divided into a number of smaller units, on which conditions varied. On the old Payette, Guy Mains reported in 1908 that the cattle allotments were in good condition, but the sheep allotments had been overgrazed, and he recommended a reduction from 100,000 to 90,000 for 1909. [91] Emil Grandjean thought conditions so good on the Boise in 1909 that he recommended a 3-percent increase in sheep. [92]

Conditions on the newly created Sawtooth were not completely favorable. Supervisor Clarence N. Woods said that the forest furnished "excellent forage for sheep," but could not satisfy the demand for grazing allotments, and that antagonism existed between the Forest Service and some of the more outspoken permittees. Part of the problem, he acknowledged, was the inexperience of the field staff, but some of the difficulties resulted from an inability to meet the demand on an inadequate resource. [93]

In what seems in retrospect to have been a serious misperception, the supervisor thought conditions on the Targhee were so favorable that he actually recommended increases in the number of sheep, cattle, and horses between 1907 and 1909. A special report in 1907 listed 205,000 sheep and subsequent increases raised the number to 217,000 in 1909. Similar increases from 9,450 to 11,750 for cattle and horses also were reported. [94] In his 1908 report the supervisor opined that conditions were generally satisfactory, with the exception of one district on which he found insufficient water. [95]

Wedemeyer, Snell, and perhaps many of the other supervisors in District 4 had been lucky in 1907 and 1908, when the summers had been unusually wet. Nevertheless, undoubtedly writing out of inexperience and misinformation, District Forester Clyde Leavitt said in December 1908 that "the grazing lands on nearly all Forests in District 4 have been brought to approximately their permanent carrying capacity, and a point has been reached which demands the establishment of a system of permit allotments in no immediate need of revision, and which will be consistent with the future requirements of the livestock industry and the best interests of the National Forests." Henceforth, Leavitt believed, the main problem would be to determine the extent to which beginners would be allowed on the forest, and the establishment of beginners, Class A, and maximum limits. [96]

Range and Watershed Studies

A careful study of the condition of the Caribou by E.R. Hodson in 1909, together with what we know of conditions on a number of other forests in Idaho by that time, however, demonstrate how faulty the district forester's projections were. Hodson pointed out that the forest had been burned over a number of times over the past 100 years and that excessive sheep grazing like that of the previous decade could only be sustained during unusually wet years. "With a dry season," he argued, "half the present number would be . . . dangerous." In 1909, the rate of grazing there was approximately 1 sheep to 1.5 acres, which was much higher than on the Weiser where 1 sheep to 4 acres was considered too high. Considerable watershed and seedling damage, especially to Douglas fir, had resulted from overgrazing. [97]

Fortunately, Leavitt's misplaced optimism did not prevent the inauguration of efforts to improve range conditions. Perhaps the most important were several experiments with the reseeding of overgrazed areas begun in 1907 in cooperation with the Bureau of Plant Industry. [98] In 1909, these efforts were expanded on the Wallowa Forest in Oregon and the Manti in Utah, and included research into methods of seed collection, eradication of poisonous plants, and range examination. [99] On the Malad district of the Pocatello National Forest, Moses Christensen plowed and seeded about 300 acres with smooth brome and slender wheatgrass. Late in 1909, a supply of different sorts of domestic grass seed was sent to several forests including the Sawtooth, and Supervisor Woods was asked to keep records of the results of reseeding efforts. [100]

In 1909, District 4 took the first tentative steps in what would be called trend and reproduction studies today. In May, Leavitt wrote to the Sawtooth National Forest, asking Woods to establish one or two sheep-proof enclosures of 1 to 3 acres each, "substantial enough to last 5 years or longer," on a suitable area such as "a burn with scattered reproduction." The enclosures were to "show the natural recuperation of the range on the removal of stock or they may be used for sowing native grasses and forage plants or to test those introduced from foreign countries." The primary purpose of the enclosure, however, was "to determine the precise effect of sheep grazing on natural forest reproduction." Behind these experiments was Leavitt's conviction that "the real purpose . . . of the Forests is to grow trees and it is quite possible that the present allotment of sheep on many of our Forests is detrimental to natural reforestation and certain restrictive measures on grazing may therefore be necessary for the proper protection of our timbered areas." Since opinions on the subject were conflicting, the enclosures were designed to provide "conclusive evidence of the effect of sheep grazing on natural reforestation before any restrictive measures on grazing are adopted." Woods agreed to undertake the experiment on the Sawtooth. [101]

Another major area of experimentation, the determination of water production, also came about in an attempt to resolve with empirical evidence a difference of opinion on the relationship between streamflow and forest growth. The point of view that a dense forest growth released a greater and more orderly streamflow persisted into the twentieth century. In 1903, Supervisor A.W. Jensen, commenting on the effect of the closure of the Forks of Manti Canyon from grazing, said that "it is noticeable in riding on the reserve that in Manti Canyon the springs are flowing a greater quantity of water than the springs on the same level, and in the same earth formation" in Ferron, Six Mile, and Ephraim Canyons. Moreover, during a heavy rainstorm, floods occurred in all four of the canyons except Manti. [102]

In a paper delivered to the American Society of Civil Engineers in September 1908, Lt. Col. Hiram M. Chittenden of the Army Corps of Engineers challenged the conventional wisdom, as Henry Gannett had earlier. The forests, Chittenden argued, could not maintain any great regulating influence on streamflow in times of great floods or of extremely low water. Moreover, he said, forests did not induce precipitation, and he questioned whether deforestation had any appreciable effect on the silting of river channels. Chittenden made it clear that he was not hostile to the creation of national forests, he merely wanted to challenge the more extreme supporters who claimed too much. [103]

In order to test these conflicting views, the Washington Office's division of silviculture wrote the various district foresters trying to locate two similarly situated areas on which water production could be measured, one heavily timbered and the other virtually denuded. [104] The areas finally selected were in District 2 at Wagon Wheel Gap in Colorado, and the experiment showed that timber removal increased streamflow. [105] Later studies at the Davis County Experimental Watershed in what by that time had become Region 4 showed that the perception that extensive vegetation could prevent or reduce at least dry mantle floods was correct.

Wildlife Management

Another area of concern, related to grazing and silviculture, was that of wildlife management. In this field the Service inaugurated two policies. Foresters were urged to protect game animals like deer and elk, while they assisted in the attempts to destroy predators, like coyotes and bears that were believed to threaten domestic livestock. [106]

The situation was hardly uniform. Deterioration of the supply of game and fish in portions of the Intermountain West had become critical. In Utah, Nevada, and part of southeastern Idaho, the virtual eradication of some species like elk accompanied severe reduction of deer. In Nevada, antelope herds had dwindled to the point that the State prohibited hunting them. [107] In Jackson Hole, elk had multiplied to such an extent that winter starvation had become common. In a number of areas, the number of fish had declined, owing to extensive seining and other practices. [108]

In practice, the States and the Federal Government dealt with depletion and overabundance in the same way—control and regulation. In 1908, Utah prohibited deer hunting for 5 years. [109] Governments set aside game preserves like the Teton State Game Preserve in Wyoming to protect the Jackson Hole Elk and the Grand Canyon Game Preserve in Arizona on what later became the Kaibab National Forest, to protect mule deer. [110]

In an attempt to improve the stocking of streams and lakes, a number of States set up fish hatcheries. Most of the States established fish and game commissions to oversee general administration. [111]

Forest officers assisted in enforcement of State game regulations. In some cases no State game wardens had been appointed, and, in others, they were lax in prosecuting cases. In some areas, forest officers were deputized as game wardens. [112] Moreover, foresters tried to catch poachers who killed Teton elk for their valuable teeth. [113]

Forest officers also began to deal with the problem of predatory animals. Here, control if not eradication was the watchword, especially for bear and coyote, which preyed on livestock. Stockmen urged the Forest Service to eradicate these animals, and at times field employees were sent to hunt them. The Biological Survey, under its general mandate, did much of the work by hiring hunters and experimenting in the use of poisons. In 1909, the Forest Service indicated that one of its goals was to eliminate predatory animals on the Grand Canyon National Game Preserve. [114] The effort to accomplish this caused extreme difficulty for the Forest Service in a very unexpected way.

Timber Management

Even though the demands of range management on forest officers' time exceeded any other function in District 4, many in the Service considered timber management more important. In the Intermountain West, the demand for timber at that time was not great enough to place an inordinate demand on the supply. Only in Nevada, with its small timber supply and extensive demand for wood products in the mines, had a large percentage of the available timber been harvested by 1909. In no other State in District 4 had the cut represented even 1 percent of the stand. Although depletion had occurred near a number of urban and mining centers, most virgin stands remained virtually untouched. In Wyoming loggers had cut less than one-half of 1 percent of the timber, and, in Utah, less than two-tenths of 1 percent. [115] In Idaho, the Service found overripe and deteriorating timber it needed to sell before the forests became an economic loss. [116]

|

| Figure 16—Planting trees at the Flowers Ranger station, 1911. |

Nevertheless, in large part because of the training and attitudes adopted from European forestry practices, Forest Service employees tended to believe in the concept of potential timber famine. As a result, they tended to emphasize almost exclusively the concept of declining supply rather than to recognize that actual demand and accessibility determined both the cut and price of lumber. [117]

In managing the national forests the Service recognized that the total volume of timber cut from the national forests was only a small portion—one-eighth of 1 percent in 1907—of the total lumber produced in the United States. However, even that amount could have some effect on the price and supply of timber in certain localities. For that reason, the Forest Service established general principles for determining stumpage prices: 1. To not take advantage of local needs to exact a monopoly price: 2. To act as the public's trustee in preventing depletion of the forests in the interest of replenishing a renewable resource without undue delay: 3. To set a reasonable price for timber in light of general conditions with due allowance for local factors: and 4. To avoid overcutting, by setting an approximate annual sustained yield for each forest. [118]

The market for timber did not remain stable. Between 1896 and 1907 timber prices generally rose, though they varied widely between regions. Between 1907 and 1914 prices generally leveled off. [119]

By the 1890's the Lake States pineries had become depleted, and lumber interests looked westward for sources of timber. During the first decade of the twentieth century, several larger companies had begun to operate in District 4, particularly in western Idaho. [120]

|

| Figure 17—Small sawmill in operation. |

Still, at the time, most District 4 timber was sold to small operators or given free to settlers. In 1906, the largest sales were made in lodgepole pine forests in Wyoming principally for railroad ties. In Utah and Colorado most cutting was confined to fire-killed timber in the mineral districts and small sawmill operators supplying towns and ranches at some distance from the railroads. [121]

Within the Intermountain West, the greatest opportunities for sawtimber lay in the ponderosa pine of the Boise and Payette River drainages. The two most prominent companies in this area were the Barber and Payette lumber companies, both of which were organized in 1902. Both had acquired private timberland, often under the Timber and Stone Act: they also cut on the national forests. [122]

As they had with graziers, the Forest Service tried to promote good relations with lumber companies. In July 1908, the Service began to publish monthly wholesale price lists of lumber in 20 principal markets of the country. These lists, it was argued, would help prevent wasteful exploitation and potential timber famine. Most of the lumber companies were willing to work with the Forest Service, since they believed that the era of free timber was over and in the Intermountain West at least, much of their supply would eventually come from public lands. [123]

|

| Figure 18—Log scaler at work. |

Responding at first to the timber depletion argument Congress prohibited the sale of timber cut on the public lands in foreign markets or even in adjacent States. Revisions of the law in 1905 and 1906 changed this policy. [124]

In 1908, the Forest Service outlined a general sales policy for states in District 4. Nevada was said to have "the poorest growth of timber of any State in the Union." Its timber was largely confined to species, such as pinyon and juniper, used for firewood, charcoal, and mine props: and its main markets had been in the mining districts. As a matter of policy, the service preferred to encourage free use and to eliminate sales of fuel to manufacturing enterprises. [125] In western Wyoming, most forests were lodgepole pine. Insect infestation had become a problem on one national forest, so only dead, down, or insect-infested timber was to be sold there. On other forests commercial and local sales were possible. [126] As with other States in the Intermountain West, the bulk of the timber supply of Utah was on the national forests. Competition from California and Oregon had become significant. Of the forests in Utah, the service allowed ordinary sales on 6, only small local sales on 11, free use on 2, and no cutting on 1. With the exception of the Uinta National Forest, which was designated a lodgepole pine type the forests were considered Englemann spruce type. [127]

Successful forest management required an adequate working plan. Such plans were worked out under the direction of technical personnel, often forest assistants, assigned to the supervisor's office for this purpose. [128] General policy allowed the cutting of live timber for sale or free use only if careful study on the ground indicated to the satisfaction of the forest officers that cutting would not injure the forest or the water supply. Only marked trees were to be cut, and sales contracts stipulated slash disposal and methods of cutting to utilize all economic parts of the tree. Skidding was to be done in such a way as to prevent excessive destruction of young growth. [129]

Pinchot cited as a model a working plan prepared for the Henrys Lake National Forest in 1906. [130] Made by Forest Assistants J.G. Peters and A.T. Boison for Supervisor Homer E. Fenn, the object of the study "was to determine the actual amount of standing timber with a view to securing from it a sustained annual yield." [131] They found the merchantable timber on the forest, in widespread stands of lodgepole pine and less abundant Douglas-fir. Both types had been burned over, generally before Euro-American occupation. Because of this, the dense Douglas-fir forests and most of the lodgepole pine were found in even-aged stands. The trees had sustained some damage from ground fires, frost crack ("gum checks"), fungus, dwarf mistletoe, and pine beetle. For economic and silvicultural reasons, the report recommended clearcutting of the lodgepole and selective cutting of the Douglas-fir.

The trained forest assistants who conducted the survey pointed out that grazing was the largest source of revenue on the Henrys Lake National Forest. Nevertheless, they recommended that forest officers eliminate sheep grazing from certain areas to improve and expand the Douglas-fir stand because, the authors indicated, "as a source of revenue both actual and potential timber production is far superior to grazing." [132] They proposed also to restrict grazing from certain areas to protect watersheds. [133]

The major problem with their projection was that it anticipated an early and radical change in timber supply and demand patterns in the upper Snake River Valley. As the report indicated, better grade lumber from western Oregon could already be marketed in the area south of Idaho Falls, except in the towns immediately adjacent to the forest, for less than the inferior products of local lumber companies. In evaluating the proposed new railroad siding at Big Springs, the report did not take into consideration the possible reductions in price, owing to economies of scale, by the Oregon companies that operated in decidedly superior and more extensive timber stands. Although it was felt that in the long run timber values might well surpass grazing values, this change was certainly not imminent.

A detailed series of comparative statistics for income from timber sales and grazing on the Targhee National Forest (successor to the Henrys Lake) is not available; however, such a series is available for Region 4 from 1909 through 1941, and for the Targhee in selected years. In fact, considering the information now available, it is safe to say that revenues from timber sales never reached as much as half those of grazing for the region as a whole until after 1950. In 1950, the Targhee earned roughly three-eighths of its revenue from timber and forest product sales and more than half from grazing. [134]

Thus, the suggested immediate reduction in grazing for silvicultural purposes was quite premature. F.W. Reed made a similar premature projection for the Teton. [135] On the other hand, reports on the Fishlake, Aquarius (Powell), and Dixie were quite realistic for the time, recognizing that the Fishlake was deficient of timber, the Pine Valley Mountains had high-quality ponderosa pine stands on the Dixie, and that the extensive stands on the Aquarius were then virtually unmarketable. [136] With better transportation, high-quality stands of timber on the Aquarius Plateau and over other portions of the Dixie National Forest have sustained a healthy timber industry. [137]

Trespass

One of the least pleasant and at times most onerous duties of rangers was the investigation of trespass. The object generally was to recover for the Service the value of goods damaged or lost and in cases of flagrant trespass to levy punitive fines on the trespasser.

C.N. Woods reported on an investigation he undertook during the winter of 1905 while on the old Teton. [138] The supervisor, receiving a report that a coal company had cut mine props on Hams Fork without a permit, asked Woods to investigate. Woods went from Jackson over Teton Pass into Teton Basin, where his horses had wintered, and brought them back to Jackson.

He expected to ride his horse southerly via the Hoback River to Kemmerer, then up Hams Fork to the trespass area. Along the Hoback River, he found the snow so deep that he had to ride in the river through much of the canyon. He spent the night in lower Hoback Basin and started out the next day on crusted snow. By the time he reached the upper end of the basin, the crust was too soft to support his horse. Leaving it on a grassy south slope, he walked 10 miles to a ranch for dinner. He expected the snow would crust over during the night, so he went back for the horse. Unfortunately, the crust was still too weak, so he left his horse again and walked 18 miles to the Horse Creek Ranger Station, where he met with Ranger Dick Smith and the two decided to ski the remaining 60 miles to Kemmerer. After several days of travel, they lost the trail. Then they followed a drainage to a ranch, where they hired some horses and went on to Kemmerer.

At Kemmerer, they found an agent of the coal company that had allegedly committed the trespass and took him before a United States Commissioner for examination. Afterwards, the company owner agreed that his employees had indeed trespassed and agreed to pay the value of the timber. Woods sent Smith back with the rented horses, went with the agent to the Hams Fork trespass site, assessed the damages, and returned to Kemmerer.

Then, since he was without transportation, Woods walked for 2-1/2 days to the South Cottonwood Ranger Station, borrowed a horse from the ranger, and returned to Jackson by way of the Hoback Basin, where he picked up the horse he had left. In reporting on this adventure, he said that he "reached Jackson none the worse for the trip."

Forest Products Studies and Tree Planting

The Service undertook measures to improve the use of forest products and the condition of the forest. In 1907, the Service joined in a successful experiment with several railroad companies in the treatment of lodgepole pine for use as ties. In the experiment, dead fenceposts from the Henrys Lake National Forest were treated with creosote to discover the most efficient process at the lowest cost. [139] In 1905, studies were begun in the lodgepole pine stands of Utah, Montana, and Wyoming to collect information on silvics, commercial markets, and methods of lumbering in order to provide a basis for the correct management of the species. [140]

The Forest Service also tried to reestablish tree stands from nursery stock. By 1908, the Service had set up two major nurseries and a number of smaller operations in District 4. The two largest were in Little Cottonwood Canyon on the Wasatch National Forest near Salt Lake City and on Mink Creek about 12 miles from Pocatello, Smaller operations were established at such places as Blacksmith Fork on the Cache and on Poorman Creek on the Boise. At the time, the Little Cottonwood nursery was the largest in the Forest Service system and the Mink Creek tied for second place. [141]

Fire Protection

The one hazard feared perhaps more than any other in the forests was fire. Examination of existing timber stands revealed that many had been burned over in times past and that the destruction from a crown fire could be extensive. Even a ground fire could cause considerable damage, often leaving the thin barked species like lodgepole pine with "catfaces," scars that left the trees susceptible to fungus infection and insect infestation. Moreover, because of their reproductive and growth characteristics, lodgepole pine tended to replace the more valuable Douglas-fir in burned areas. Firefighting was often arduous and time-consuming work. Emil Grandjean remembered fighting a fire on the old Sawtooth near the headwaters of the Salmon River. He found himself in the saddle nearly all day and "part of the night," with little extra money to hire laborers and scant instruction. [142] Guy Mains remembered his men going out to a fire with a crew of settlers from Round Valley with inadequate mess facilities. [143]

|

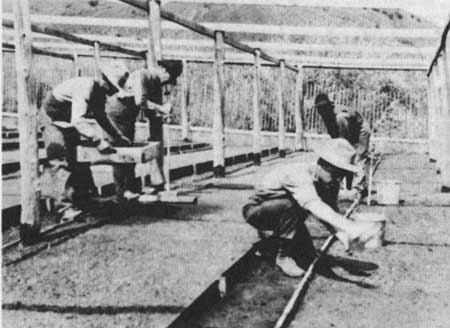

| Figure 19—Seedbed preparation, Bannock Creek Nursery, ca. 1908 or 1909. |

Carl Arentson outlined the technique they generally used. With axe, mattock, and shovel, they built a fire-line, burning out any vegetation by backfiring between the line and the fire. After establishing the fireline, they tried to hold the fire on the ground inside it to prevent "crowning" by lopping any flammable limbs as high as they could reach. [144]

Foresters also undertook presuppression measures. On the Cache, the rangers established fire patrols and posted fire warnings. [145] On the Boise they set up fire lookouts where observers kept watch during the daylight hours. Communication with the lookouts was a problem. They tried heliographs, but found that much less satisfactory than telephone. [146] Eventually, they built a telephone line system serving many lookouts and guard stations.

Engineering

When the ranger was not checking on permittees, working on timber reconnaissance, or investigating trespass, he might have been busy doing what today would generally be regarded as engineering. Rangers and guards did virtually all surveying and building—including surveying forest boundaries, constructing trails or bridges stringing telephone lines, and gauging stream flow. [147]

Special Uses

Though the Interior Department had previously allowed special uses on the forests free of charge, in 1906 the Forest Service asserted the right to charge for the use of resources. The charge was theoretically based on the value of the resource had it been used by the public, but in practice it was much less. [148] The basic principle followed in granting special uses was that since the forests were for public use no privileges were to be denied unless their exercise materially reduced resource values or threatened to harm the public.