|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 4

Forest Protection and Management: 1910 to 1929

Leadership

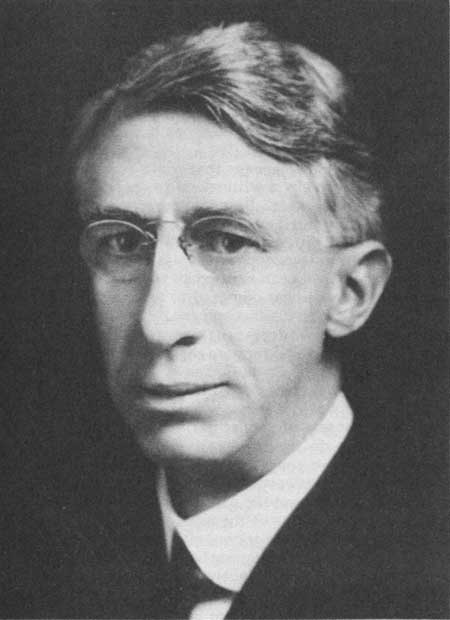

In 1910 both the Forest Service and Region 4 reached important benchmarks. [1] In March 1909, the Nation inaugurated William Howard Taft as president. Taft appointed Richard A. Ballinger of Washington as Interior Secretary, replacing Pinchot's and Theodore Roosevelt's friend James R. Garfield. Relations between Taft and Ballinger on the one side and Pinchot and Roosevelt on the other had deteriorated as Ballinger tied himself closer to large corporations, especially the Guggenheim interests. Highly critical of what he perceived as Ballinger's indifference to conservation and opposition to progressive policies favoring small business, Pinchot attacked the Secretary openly and Taft asked for and got Pinchot's resignation in January 1910. Henry S. Graves supplanted Pinchot as Chief Forester. [2]

In early 1910, Clyde Leavitt left Region 4, eventually landing with the Canadian Forestry Department. [3] Leon F. Kneipp suggested that although he had mastered technical skills he lacked administrative ability. Leavitt's successor, Edward A. Sherman, began his career as a newspaperman and had previously worked as a Forest Service inspector in Montana and Idaho. In the Bitterroot Mountains Sherman's political finesse earned him the nickname "Old Smoothie." He remained as Regional Forester until the spring of 1915 when he moved to Washington as assistant chief in charge of lands replacing William B. Greeley in the position. [4]

|

| Figure 22—Edward A. Sherman, Regional (District) Forester, 1910-15. |

Kneipp, then serving as assistant chief in the Branch of Grazing, replaced Sherman. An office boy from the Chicago waterfront, Kneipp had joined GLO Division R in Arizona as a political appointee. Kneipp's appointment aroused opposition from some technically trained foresters. Graves reportedly passed them over for Kneipp because of their "lack of knowledge of local mores, procedures, and practices." [5]

Kneipp remained until the fall of 1920, when he transferred again to Washington and Richard H. Rutledge replaced him. Rutledge, an expert in grazing administration and an excellent administrator, remained until the fall of 1938, when he moved to the Interior Department as Chief of the Division of Grazing. [6]

Headquarters Facilities

Throughout the entire period, the region operated out of the building Leavitt had selected on 24th Street and Lincoln Avenue in Ogden. Leavitt's expectation that the office might move into a Federal building to be constructed had not materialized, and the Forest Service continued to rent on annual leases. The supply depot used a three-room office and all the basement and ground floor of the building, while the regional forester's organization occupied 26 rooms—a total of 7,500 square feet—on the second and third floors. [7]

|

| Figure 23—Leon F. Kneipp, Regional (District) Forester, 1915-20. |

By the mid-1920's, however, the facility had begun to show considerable wear. The linoleum looked shabby and a number of the window blinds had broken. Meetings and correspondence between Rutledge and T.V. Pearson, administrative assistant in the division of operation, and W.H. Shearman, manager for the Kiesel estate, brought about some improvements, but did not solve as many problems as the regional administration thought necessary. Ogden City inspectors found some code violations, especially in the building's electrical system, which were only partly corrected. [8]

Personnel

By 1927, though the size of the regional office staff was smaller than it had been in 1920, it had expanded considerably since 1910. [9] An assistant regional forester headed each of the major divisions except Finance and Accounts, Engineering, Maintenance, and the Great Basin Experiment Station. To the Divisions of Operation, under Clarence N. Woods; [10] Forest Management under Chester B. "Chet" Morse; Grazing (renamed Range Management by the late 1920's), under Ernest Winkler: and Lands, under R.E. Gery, had been added Engineering, under Regional (District) Engineer J.P. Martin, and Public Relations, under the direction of Dana Parkinson. Lee Stratton served as fiscal agent, Manly Thompson was law officer, and H.C. Baker had been appointed maintenance clerk. The Great Basin Experiment Station under Clarence L. Forsling maintained an office in Ogden after 1916, but its headquarters was located in Ephraim Canyon on the Manti National Forest. Regional office staffs tended to be small by present standards, ranging from a high of 14 in Engineering and 8 in Finance to 2 each in Operations, Law, and Public Relations. Grazing and Forest Management had four each, and Lands and the Great Basin Station had three each. Baker maintained the building and equipment with a staff of four. [11]

By 1927, less change had taken place on the national forests themselves. The announced desire to decentralize not only from Washington to the regional offices, but to forests [12] brought about increases in staffs in the supervisors' offices of some of the larger forests, whereas others were not affected at all. Ranger districts were still usually one-person operations. The Boise, the Idaho, and the Payette National Forests each had two assistant supervisors and two clerks. The Cache, Powell, Uinta, and Wyoming had staff range examiners. A large number of forests (Ashley, Caribou, Challis, Dixie, Humboldt, Kaibab, La Sal, Manti, Minidoka, Nevada, Sawtooth, Teton, Toiyabe, and Wasatch) functioned with two or three persons in the supervisor's office, usually the supervisor and one or two clerks. [13]

Professionalism and Commitment

Nevertheless, the Forest Service's esprit de corps noted by Herbert Kaufman promoted a sense of professionalism among forest officers. [14] Whether the employees had come up through the ranks like Kneipp and Woods or had a technical education like Lyle F. Watts and Emil Grandjean, they exhibited pride in a professional organization. As Edwin Cazier put it, "I have always been proud of the United States Forest Service and sincerely hope that I never have cause to feel otherwise." [15] Wearing prescribed uniforms, they were touched by an almost religious sense of duty. [16]

The organization reinforced the sense of commitment and participation by periodic training sessions and meetings. These also provided a valuable exchange of ideas. [17] Rangers, supervisors, and staff joined with the region officers to discuss activities such as timber, grazing, lands, and recreation. The meetings helped the field force gain "a better understanding of the technical points of the regulations governing the management of the national forests." [18] Forest management training schools also were held in the field. [19]

Forest officers functioned under a great deal of pressure and inconvenience. The Forest Service demanded enormous commitment from its officers and got it from most of them. [20] Over a period of 7 years as an inspector, C.N. Woods spent an average of 200 days a year away from the regional office. [21] On the forest level, Leo E. Fest compared the operation of a ranger district to managing a large farm. With timber and livestock management, fire control, engineering, and maintenance, the ranger tried to "harvest a crop and still leave [the] area in a good . . . thrifty condition, where it will produce and keep producing the crops it is best suited for." [22]

Those who could not accept that sense of commitment, demonstrated by a willingness to sacrifice for the good of the Service, left. Based on current standards, turnover was quite high during the period before World War I. Supervisor William Hurst declined to move from his home and farm to accept a new assignment and resigned. Emil Grandjean refused to transfer from the Boise to the Nevada, was demoted to assistant supervisor, and resigned in disillusionment. [23] In 1915, when the Service prohibited forest officers from holding grazing permits, several rangers resigned to pursue their livestock interests. [24] Orrin C. Snow, who spent too much time in his livestock operations, was forced out. [25]

Shortly after World War I, a ranger caught embezzling money from the sale of timber permits was dismissed and sent to jail. He tried to justify himself by circumstances: "Many are going wrong since the war—I guess it's in the air." [26] However, this attitude was unusual. Both forest officers and the public tended to see Service employees as custodians of the public resources and recognized their scrupulous commitment to integrity. [27]

Supervisors concerned themselves particularly with securing competent and effective personnel. [28] One means was offering steady employment and a reasonable salary and creating a sense of belonging and security, so that employees perceived that they had the trust and confidence of their superiors. [29] Rangers had permanent appointments. Guards were seasonal, and some supervisors thought this arrangement created difficulties in finding and keeping competent men in these jobs.

Reporting and Inspection Systems

Most important, besides the sense of commitment, in maintaining the integrity of the Service were the reporting and inspection systems. Supervisors and rangers were required to keep and submit various detailed accounts. [30] Forest officers had to account for property under their control and to report on their activities through a daily diary that they summarized at the end of the month, assigning time to the various categories of forest administration. Regulations required the supervisor to review the diaries and reports before certifying the ranger for his monthly salary, unless the supervisor knew the ranger was on an assignment that would make it impossible for him to complete the report. In practice, the supervisors did not usually wait for the formal monthly reports before completing the certifications. [31]

Inspections and review of diaries and reports proved valuable. A thorough inspection of the Uinta by A.C. McCain in 1913 revealed a deplorable situation. Willard I. Pack supervised a number of rangers related to him by blood or marriage whose diaries showed a clear inattention to duty. Pack said he had paid little attention to their diaries and reports and was unaware of their ineffectiveness. Regional Forester Sherman offered Pack the alternative of demotion to ranger, but the supervisor chose to resign. Sherman furloughed two of the offending rangers; Robert Pack Supervisor Pack's brother, resigned under pressure. [32]

After Clarence Woods came to the regional office, he still found some employees whose attitudes needed changing. Some forest officers believed they could "get by" provided their morals were "pretty much above criticism," whether or not they were energetic or efficient. Woods did his part to change that attitude. On one inspection he rode with a ranger over his district. He found the trails poorly maintained, the wires on pasture fence loose, and paperwork deficient. When Woods suggested that the ranger ought to do something about the trails, he replied that they were "just as God Almighty made them." Woods responded that God "had favored some men with good muscles and strong backs" so they could do manual labor, and that He blessed others with good minds so they could do "constructive thinking," but as far as he had been able to observe, "the ranger had not been favored in either way." The ranger promised to do better, but later resigned. [33]

Although some supervisors, such as Guy Mains, received high marks for their ideas and field supervision, their paperwork left much to be desired. In 1916, Kneipp said that 2 years before he had found Mains's records in "disarranged attire," and indicated he was sorry to note that in the intervening "two hard winters" Mains appeared, "figuratively speaking," to be "pretty badly frost-bitten. Don't you think," he wrote, "it is time that you protected yourself against exposures of this character?" [34]

The character of the supervisor and the rangers made a great deal of difference in the administration of a national forest. During the late teens and early 20's, for instance, reports from the Toiyabe showed lax grazing administration. The appointment of James E. Gurr in 1925 reportedly "brought grazing administration up from . . . a pretty low standard to a fairly high" one. [35]

Women constituted the most mistreated group of employees. Arlene Burk, secretary in the region's division of operations, traveled on official duty to conduct inspections of filing systems and paperwork on the various forests. At first, under Service regulations, the region furnished transportation, but she had to pay her own board and room solely because she was a woman. After enduring second-class status for some time, she complained to Rutledge, who balked at first, saying that she lived at home. Later he backed down and arranged to pay her per diem expenses. [36]

Public Relations

Although the Division of Public Relations was not established until 1920, many successful forest officers were already promoting good relations with the public. [37] In 1914, E.C. Shepard of the Cache took photographs on the forest for displays at the Panama-Pacific exposition. [38] On the Caribou in the 1920's, Sterling Justice showed films to local groups and prepared exhibits for the Eastern Idaho State Fair. [39] Edwin Cazier managed to win over an antagonistic stockman and his son by cultivating an interest in the boy and helping him write an essay on range management. [40]

Timber Management

During the period from 1910 to 1929, as before, a number of the assumptions based on European precedents under which the Forest Service formulated general timber management policy were extremely difficult to apply in Region 4. First, the Service operated on the assumption that depletion constituted the major threat to the timber supply. [41] Second, the Washington Office expected to use timber disposal as a means of stand improvement, requiring cutting the poorest and most diseased timber as part of large sales. [42] In practice, the forests in Region 4 tended to be far too vast compared with consumer needs, far too distant from markets, and far too overmature to make such policies practicable.

The region had three major commercial markets: Boise, Salt Lake City, and Idaho Falls, none of which was very large (see table 5). The forests fell generally into three groups: (1) Forests with some commercial markets plus a moderate local market, (2) Forests with virtually no commercial market, but a moderate local market, and (3) Forests with virtually no commercial market and a very small local market.

Table 5—Timber sale receipts by forests Region 4, 1913, 1914 (ranked by value of sales to 1914)

| Forest | FY 1914 | FY 1913 |

| Category 1 | ||

| Wyoming | $8,083.70 | $7,331.12 |

| Manti | 7,808.57 | 10,790.49 |

| Fayette | 6,561.25 | 19,030.41 |

| Wasatch | 6,240.73 | 271.90 |

| Nevada | 5,569.33 | 5,097.89 |

| Uinta | 5,507.40 | 868.29 |

| Toiyabe | 4,437.20 | 5,899.03 |

| Targhee | 3,901.74 | 7,797.54 |

| Cache | 2,932.55 | 2,426.21 |

| Palisade | 2,799.36 | 3,273.54 |

| Weiser | 2,005.43 | 1.648.88 |

| Category 2 | ||

| Salmon | 1,754.44 | 4,823.23 |

| Sevier | 1,657.36 | 1,386.17 |

| Fishlake | 1,646.20 | 2,770.24 |

| Fillmore | 1,566.07 | 1,868.80 |

| Sawtooth | 1,424.34 | 1,909.84 |

| Lemhi | 1,411.36 | 2,216.31 |

| Boise | 1,282.17 | 2,841.82 |

| Minidoka | 1,253.18 | 1,118.15 |

| Caribou | 1,160.34 | 1,123.48 |

| La Sal | 1,108.25 | 1,449.75 |

| Challis | 1,090.66 | 1,209.44 |

| Teton | 1,049.00 | 732.50 |

| Dixie | 1,031.19 | 805.65 |

| Category 3 | ||

| Powell | 782.50 | 1,365.00 |

| Ashley | 637.31 | 1,040.46 |

| Pocatello | 623.35 | 648.15 |

| Kaibab | 417.00 | 314.80 |

| Humboldt | 395.61 | 355.69 |

| Santa Rosa | 158.75 | 43.00 |

| Nebo | 25.50 | 179.80 |

| Idaho | 6.00 | 40.75 |

| Ruby | 00 | 00 |

| Totals | 76,343.74 | 92,668.33 |

Source: A.C. McCain to Forest supervisor, July 22, 1914, File: S—Sales, General, 1912-1923, Box 601102, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC. For a description of the categories, see the accompanying text. | ||

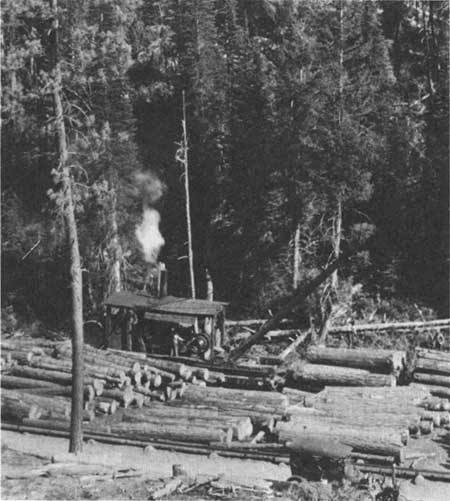

Peculiar conditions allowed some forests to fit in the first category between 1910 and World War I (table 5). [43] The Wyoming, Uinta, Wasatch, and Targhee sold ties extensively to the Union Pacific and its subsidiaries. The Manti, Nevada, and Toiyabe found ready markets in nearby mines. The accessibility of transportation and the good quality ponderosa pine lumber helped the Payette and the Weiser, and the Palisade and Cache were close to the major market centers in Idaho Falls and Salt Lake.

|

| Figure 24—Steam log jammer in operation, Boise National Forest, 1925. |

The second category included forests near moderate-sized settlements, but distant from the major commercial market centers. These included forests like the Sawtooth, Salmon, Challis, Lemhi, and Minidoka of south-central Idaho; the Caribou and Teton in eastern Idaho and west-central Wyoming; and the forests of southwestern Utah such as the Dixie, Fishlake, and the Fillmore. On some of these forests, for example, Fillmore, saw timber was extremely scarce, and the accessible pinyon-juniper and aspen stands were principally valuable for posts and poles. [44]

The third category, forests away from major commercial centers and transportation, near small settlements, or with large private timber stands nearby, could expect only a small market, These included the Powell and Ashley in Utah, the Kaibab in northern Arizona, the Idaho in Idaho, and the Humboldt, Santa Rosa, and Ruby in Nevada. Each had a local market, but some of these forests, particularly the three in Nevada, suffered from an absence of marketable timber. Most of their supply consisted of pinyon-juniper forests valuable principally for posts or firewood.

A survey by Assistant Regional Forester O.M. Butler of the forest and market conditions in Region 4 in 1912 indicated the futility of trying to impose the European model. The Boise block was quite typical as it contained all three kinds of forests. From that block, only 5 per cent of the 4.9 million board feed cut in 1911 "entered into the general competitive market." If the timber growing in western Idaho had been found closer to major market centers, its volume might have justified its transportation. Because of the disadvantage in the cost of transportation to the mill, these forests could not compete successfully with Oregon lumber operations. Butler believed that if the forests in the Boise block were able to operate on a sustained yield basis with a 140-year rotation, they could have produced 50 million board feet (MM) a year. This was, however, more than 10 times the current production, so such a basis was patently impossible (see table 5). [45]

As market conditions changed over time, forests moved from one category to another, usually depending upon their access to commercial markets. By 1919, for instance, Supervisor W.W. Blakeslee on the Toiyabe had seen a decline in fuel sales to mining companies, since by that time electricity had begun to supply most power for mining operations. [46] By the early 1920's, the expansion of mining in the Jarbidge district on the northern Humboldt increased the market for timber from that forest. [47] By the 1920's, the Uinta had cut into the Manti's mine prop business and moved it out of the first group. [48] (For data on the changing value of stumpage and logs nationally see table 6.)

Table 6—National stumpage, wholesale, and log and lumber prices, 1910-1930

| Wholesale price index (1947-49 = 100) |

Stumpage prices (dollars per 1,000 bd. ft.) |

Log and lumber prices (dollars per 1,000 bd. ft.) | ||||

| Year | BLS consumer | Lumber | Douglas- fire | Ponderosa pine |

Douglas-fir saw log | Douglas-fir lumber (whsle) |

| 1910 | 45.8 | 16.6 | $2.20 | $3.60 | $9.00 | $13.00 |

| 1911 | 42.2 | 16.3 | 2.30 | 2,50 | 8.00 | 11.00 |

| 1912 | 44.9 | 17.5 | 2.30 | 2.70 | 8.00 | 11.50 |

| 1913 | 45.4 | 18.5 | 1.70 | 2.20 | 8.50 | — |

| 1914 | 44.3 | 17.1 | 1.60 | 2.00 | 7.50 | — |

| 1915 | 45.2 | 16.7 | 2.90 | 2.50 | 7.00 | 10.60 |

| 1916 | 55.6 | 18.9 | 1.20 | 2.90 | 8.50 | 10.80 |

| 1917 | 76.4 | 24.7 | 1.60 | 2.20 | 11.00 | 16.20 |

| 1918 | 85.3 | 28.6 | 1.80 | 2.70 | 14.50 | 19.50 |

| 1919 | 90.1 | 38.7 | 2.40 | 3.00 | 17.00 | 24.90 |

| 1920 | 100.3 | 56.6 | 1.80 | 3.70 | 22.00 | 34.90 |

| 1921 | 63.4 | 30.5 | 1.90 | 3.20 | 14.50 | 18.00 |

| 1922 | 62.8 | 33.9 | 2.50 | 4.00 | 15.00 | 21.00 |

| 1923 | 65.4 | 38.3 | 2,50 | 3.00 | 18.50 | 27.30 |

| 1924 | 63.8 | 34.0 | 2.20 | 3.50 | 16.00 | 22.40 |

| 1925 | 67.3 | 34.5 | 2.10 | 3.60 | 15.00 | 21.10 |

| 1926 | 65.0 | 33.2 | 2.20 | 3.70 | 16.00 | 20.40 |

| 1927 | 62.0 | 30.9 | 2.50 | 3.40 | 15.00 | 19.80 |

| 1928 | 62.9 | 30.1 | 2.90 | 2.50 | 15.50 | 19.40 |

| 1929 | 61.9 | 31.2 | 2.70 | 3.60 | 16.00 | 20.60 |

| 1930 | 56.1 | 28.5 | 3.30 | 3.60 | 15.50 | 17.80 |

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1957 (Washington: GPO, 1960). | ||||||

In Region 4, the demand was so minuscule that some forest officers had difficulty justifying the amount of time required to administer the many small timber sales they had to conduct. [49] Because of the time invested in administering small free use permits for green timber, forest managers allowed free use of small amounts of dead timber, but gave away no green timber to local people for their personal or commercial use. [50] To minimize the time on small sales, L.L. White of the regional timber staff suggested that the supervisors consider giving year-long permits for the estimated amount small users would want. [51]

In the period before World War I, the region ran into some problems in sale administration. Problems ordinarily appeared during periods of market depression when timber purchasers wanted to get out of contracts they could not fulfill at an acceptable profit. In those cases, regulations required the regions to try to prevent the purchaser from breaking the contract and to recover the loss to the Federal Government from those who did. [52]

In the region as a whole, the Targhee might be considered the "average" timber forest among those favored both with some commercial market and a moderate-sized local market. The report of C.E. Dunston, based on his reconnaissance of the Targhee in 1910, reveals assumptions in accord with the general European model, including markets for products from timber stand improvement, and the idea of imminent forest depletion. [53] Dunston thought that the forest existed in a "depleted condition" largely because of primeval fires that had destroyed an ancient Douglas-fir forest. [54] The Targhee had been created because of the "inroads being made on merchantable stands." The Oregon Short Line Railroad had recently constructed a railroad through the forest to West Yellowstone, MT, and the settlements near St. Anthony and Ashton were growing rapidly. [55]

Dunston's proposed timber management plan was a mixture of the ideological and realistic, addressing actual conditions with European forestry prescriptions. He recognized that for some time, logging would continue "with portable, steam power sawmills" with a capacity of 3 to 10 thousand board feet (M) a day. The one attempt to introduce a larger mill near Island Park had failed. Dunston attributed the failure, quite realistically, to "an insufficient amount of sawtimber accessible to the sawmill setting," and a location "at too great a distance from the market at St. Anthony." [56]

On the ideological level, Dunston based his prescription for forest management at that time on the assumption of an extensive increase in cut that would allow timber stand improvement. In his view, "the chief aim" ought to be "the establishment of the best possible silvicultural conditions and consequent ultimate normality [by which he seems to have meant even-aged sustained-yield management] of timber stands on all parts of the Forest." [57] He concerned himself with protection against forest fires and diseases, particularly dwarf mistletoe and bark beetle. These diseases generally attacked trees "which have passed the period of maximum growth and are decadent." [58] He prescribed stand improvement and selection cutting for Douglas-fir and clearcutting in strips for lodgepole. In mixed stands of lodgepole and spruce, he hoped to reduce the number of lodgepole. Even though only 3.3 million board feet had been sold and only 1.8 million cut in 1910, his prescription required an annual cut of in excess of 8 million board feet including 4 million board feet of the Douglas-fir! [59]

The impossibility of such a silvicultural prescription in those days is evident from subsequent reports. In 1919, the forest consisted of "a large surplus of overmature timber." The supervisor said that "at least 75 percent of the timber that is used in the Upper Snake River Valley is imported from Oregon and Washington." He estimated that they were then cutting about 30 percent of the annual growth and no more than 2 percent of the mature and overmature timber. [60] In 1925, Chester B. Morse, assistant regional forester, estimated that on the Moose Creek plateau, "the annual loss due to decay, insect killing of overmature timber" and other causes "is greater than the annual growth." [61]

A reconnaissance of the Teton in 1912 revealed an essentially similar state of mind on the part of the investigators. Prescriptions were based on European precedents and the expectation of an immediate extensive market in southern Idaho. [62] By the early 1920's, the Teton timber stands still remained largely untapped except for local uses, although the investigators reconnaissance expected the tie market to open these stands up in the near future. [63]

Ironically, between 1910 and the mid-teens, largely inflexible Forest Service policy, including an unwillingness to set stumpage prices in accord with market conditions, increased the inability to achieve the objective of even-aged stands operated on a sustained-yield basis. [64] The Washington Office insisted that stumpage prices represent actual value of standing timber under "normal" market conditions, whereas the period between 1910 and the First World War witnessed a depression in the timber industry. [65] When the Federal Government created the forests of western Idaho the Service set stumpage rates at $1.00 to $2.00 per thousand board feet (M). Under those conditions, the forests made some sales to larger companies who could compete with Oregon operations. Shortly thereafter, the Washington Office set the rate at $3.00 per M and large companies stopped bidding. on the timber. Thereafter, sales went generally to small mills filling the local market, where low transportation costs and a willingness to accept lower quality offset the competitive advantage from the Oregon forests. [66]

Local forest supervisors complained that the required stumpage rates were too high, but the Washington Office paid little attention at the time. [67] Unfortunately, decentralization had not reached the timber market policy. [68] O.M. Butler argued that the Government ought to "appraise each species separately upon its value in the market." At that time, "the inferior species do not justify . . . stumpage rates much more than $1 per M if utilized as lumber." [69]

Two Service policies designed to help small users did open up more timber for acquisition and increase the probability of stand improvement. A 1912 law allowed farmers and settlers to purchase mature, dead, and down timber at cost. [70] (These were later referred to as S-22 sales after the regulation allowing the procedure.) In addition, settlers, local residents and prospectors were allowed free use of dead timber. [71]

By the mid-teens, some in the Washington Office, particularly William B. Greeley, had begun to recognize that their current pricing and cutting policies and silvicultural prescriptions were unworkable. This change in position seems to have come because of regional objections to various Washington Office decisions. Responding to a Washington Office statement issued in October 1914, Assistant Region Forester A.C. McCain suggested a number of revisions in lodgepole pine policy. [72] Arguing that railroad ties constituted the principal market, he objected to rules that set a maximum cut at 20 to 40 percent of the stand. He pointed out that in uneven-aged and often defective stands like those found in the region, it was often necessary to take as much as 50 percent to meet the quality and specifications of railroad companies.

Moreover, he opposed as futile the cutting prescriptions, aimed at controlling diseases and beetle infestations, that required loggers to remove snags and diseased and insect-infested trees as part of the sale. In the previous year, the region had discovered a major beetle infestation on the Palisade. They tried to remove it by cutting the infested trees, but subsequently the supervisor informed McCain that apparently the effort had failed. McCain believed that experience had shown they could not justify such control work on either economic or silvicultural grounds. This lack of justification was doubly true of trees with root rot, since felling them wasted the operator's money and added prematurely to debris on the ground.

McCain also called for a change in the slash disposal policy. Here, the prescription called for piling and burning. He wanted flexibility that would allow the region to decide whether to use piling and burning, piling and not burning, or lopping and scattering. [73]

He also wanted flexibility in determining stumpage prices. Regulations had required that, in calculating stumpage rates, the regions use a profit margin of 15 to 20 percent of presumed investment. McCain pointed out that subcontractors—"gypos"—did virtually all of the actual logging, so hypothetical investment did not reflect actual conditions. Moreover, the amount of usable material in uneven-aged and deteriorating stands was certainly not constant, a condition which made prediction of profit margins imprecise at best.

After considering McCain's views, Greeley accepted the proposals on marking, utilization prescriptions, and appraisal. He rejected the criticisms on diseased and infected trees since Agriculture Department scientists believed that the insects and diseases could be controlled through cutting. He allowed the region to use methods other than piling and burning on an experimental basis. [74]

By the early 1920's, the regional administration found that piling and burning of slash was the best method. Although lopping and scattering was less expensive, under the region's dry conditions the material did not deteriorate rapidly enough, hence it was a fire hazard. [75] Region 4 forest personnel also favored the establishment of cooperative funds from timber sales to allow slash piling and burning. [76]

In 1915, the regional administration pressed even harder to change its management techniques away from the European model in order to deal with actual conditions. Small sales averaging $12.00 in stumpage and based on users applications, rather than large sales based on reconnaissance and extensive silvicultural prescription, were the norm, so the region began to plan for sales of the size for which users were most likely to apply, rather than to plan large sales that no one would buy.

Under this concept, market conditions rather than ideologically based prescriptions governed sales prices. In a competitive market, timber was to be appraised at its assumed market value. In isolated regions, "the prices should be on a reasonable basis, corresponding to a great extent to rates in the competitive market." [77]

Under this policy, the region took a greater interest both for its own information and to help guide prospective timber purchasers in companies' logging and milling costs and profit margins. Representative figures were obtained in 1913 and 1914 from samples taken from each forest in the region. [78]

Thoughtful regional foresters, like Leon F. Kneipp of Region 4 and John F. Preston of Region 1, recognized that practical considerations had to play the dominant role in timber management. Both believed that no one had enough experience to know what the "best silvicultural treatment of a given mixed stand might be." In many cases, prescriptive ideological models made management difficult; in others, they gave away timber that ought to have been sold. The presumption, for instance, that Douglas-fir was not a valuable species in ponderosa pine stands had led to its treatment in appraisals as a negative value and thus, in effect the Service actually paid lumber companies to take it. [79]

After his appointment as Chief Forester in 1920, Greeley continued to shift policy in a more realistic direction. In a 1925 statement he commented that "refined and detailed schemes of regulation, following European precedents . . . never got off of paper and into practical operation in the woods." Although he clearly believed in depletion as a general concept, he recognized that the major problem in national forests was great overstocking of mature and overmature timber. For that reason, he proposed to prescribe management only in broad terms. The time for refined regulation on the European model, could come "only after we have worked over our forests into more like a normal [even-aged] distribution of age classes and also after much more comprehensive growth and yield figures have been secured." [80]

Under this concept, local conditions were allowed to dictate profit margins. This was particularly important in view of the often poor quality of timber and high logging costs incurred by small operations in Region 4. In figuring a small sale on the Ashley in 1921, for instance, the ranger used a presumed profit margin of 30 percent. He based the stumpage value on the average expected price of the types of lumber the operator could realistically hope to sell, minus the total conversion costs (including the profit margin, maintenance, depreciation, and other costs of operation). In that case, the stumpage value was figured at $2.17 per M. The ranger recommended that they offer the sale at $2.15 per M because of the poor quality of the stand. [81]

Though by the 1920's a practical acceptance of actual conditions by the Washington Office had replaced the attempt to adhere to theoretical concepts, the fear of depletion motivated much of the legislation and lobbying throughout the period. [82] In addition to the argument for flood prevention and watershed protection, supporters used depletion arguments in support of the Weeks Act of 1911, which allowed the Forest Service to purchase private lands in the watersheds of navigable rivers to add to the National Forest System. [83] The General Forest Land Exchange Act of 1922 authorized the Service to exchange federally owned lands or stumpage within a national forest for privately owned land. This allowed the Service to control and rehabilitate logged-over lands that had generally been neglected because market conditions did not warrant their replanting. The Clarke McNary Act of 1924 permitted the Federal Government to assist the States in fire prevention, the reforestation of denuded lands, and farm forestry. This act also amended the Weeks law to allow the purchase of lands suitable for timber in addition to those in major watersheds.

In general, although the rationale for such legislation had little immediate applicability to Region 4, its application had a salutary effect on the lumber industry, the States, and the Forest Service. It allowed the Service to increase the amount of land under its management and to expend Federal dollars in improvement of lands that, because of market considerations, other agencies or private companies would otherwise not have improved. It allowed the States to develop cooperative programs in fire prevention and forestry farming that would otherwise probably not have been feasible because of lack of funds and markets.

Even where there were few commercial sales, the regional personnel attempted to enforce silvicultural prescriptions for removing defective and diseased trees, leaving low stumps, and piling and burning slash. [84] On some of the forests like the Uinta, free use outweighed sales. [85] Many of the few large sales on the Fishlake were for derrick poles. Nevertheless, the working circles and sale areas were inspected and rangers graded on sales administration and stand improvement. [86]

Immediately after World War I, in 1919, prices rose rapidly, then declined in the early 1920's before stabilizing by 1923. [87] Stabilization helped improve markets in Region 4, as indicated by such developments as the Standard Timber Company's tie sale on the Wyoming, the activities of the Hoff and Brown lumber company on the Idaho, and sales to Boise-Payette on the Payette and Boise. [88]

Accompanying this improvement was the hope of introducing long-term stability and sustained-yield management to the forests of Region 4. [89] Meeting this goal required the development of timber management plans based on accurate assessments of timber volumes and values within each national forest. The Service attempted to achieve this through reconnaissance, intensive planning, and logging units established in working circles. Ordinarily, the working circle consisted of a topographic management unit tying timber to the nearest point of manufacture. [90]

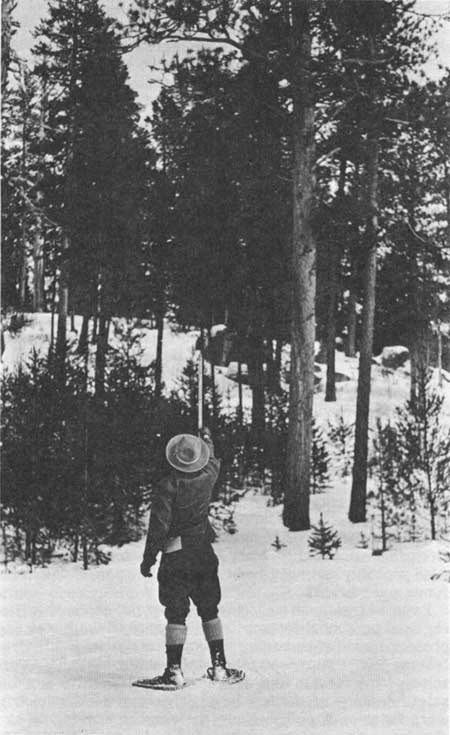

Forest reconnaissance efforts had begun in Region 4 in 1908. By 1910 they had been undertaken on the Kaibab, Manti, Minidoka, Pocatello, Salmon, Sawtooth, and Targhee. [91] Timber cruising included the establishment of survey control from a base line, the use of mapping techniques, and the determination of timber volume and types. [92]

|

| Figure 25—Winter timber cruising, ranger estimating tree height, 1927. |

As methods and assumptions changed, new cruises refined previous figures. On the Weiser, for instance, a reconnaissance of 1911 and 1912 was redone between 1927 and 1929. Because of a change in method, the new cruise showed a larger volume of merchantable timber than the previous estimates. [93] On the Provo River Working Circle of the Uinta and Wasatch, a cruise in 1925 updated and augmented work done in 1911, 1913, 1914-16, and 1923. [94] Recognition of the importance of pinyon-juniper forests on the Fillmore necessitated a reconnaissance of that type in 1922. [95]

Following the cruise, the forest officers drafted a timber management plan. It provided a description of the working circle and its subunits, a statement of the silvicultural objectives, and a plan for achieving these objectives through timber sales and silvicultural practices. [96]

Timber management plans where a large amount of private timberland was involved (especially in western Idaho and in the area along the Union Pacific Railroad in Utah and Wyoming) were sound theoretically but impossible to implement from a practical standpoint. On the Idaho National Forest, for instance, during the early teens, lumber companies bought virtually no timber from the forest because of the large private holdings by Boise-Payette. This condition placed the Idaho in the bottom rank of forests in volume logged, although its timber resources were comparatively large.

Some cruises showed that although the timber stands might be extensive, they were actually unmarketable. A 1915 cruise of the North Fork of the Duchesne on the Uinta National Forest showed that the only practicable method of getting the sizable timber volume out was either building an extensive road system or dredging and blasting to rechannel the river for driving. After considering costs of these alternatives, Daniel F. Seerey decided that logging was economically unfeasible at the time. [97]

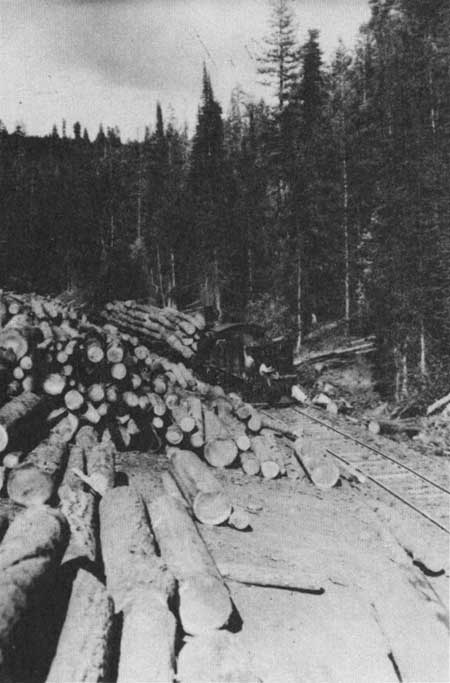

|

| Figure 26—Horse skidding of lodgepole pine to tie mill, Flat Creek, ID. |

Most sales, on forests as diverse as the Ashley, Weiser, and Uinta, were small—10 M to 15 M—and known variously as ranger, at cost, green card, or regulation S-22 sales to farmers and ranchers who manufactured the lumber at small mills. [98] Often, as on the Minidoka, the rangers would set aside one day a week when farmers could come to purchase timber. Joseph W. Stokes laid out small sales in isolated 5- to 10-acre patches, which he classified for thinnings, small poles, large poles, or large timber. [99]

During the 1920's, a major problem in implementing timber management plans stemmed from the lack of personnel. The ranger districts were mostly one-person operations. Shortly after his appointment as a ranger on the Weiser, Dewitt Russell was put to work on a large sale on Filley Creek. Assistant Supervisor Felix Koziol planned the sale and left after he got Russell started. The ranger did the marking, scaling, and woods supervision alone.

After several weeks, it became apparent to Russell that he had, and would have, no time to do anything on the district but run the sale. He tried in vain to get some help, then decided to bring matters to a head by applying for a week's annual leave. "No one in his right mind," he pointed out, "applies for annual leave in the middle of the summer on a fire forest." His application brought the desired result, as Supervisor John Raphael paid him a quick visit and demanded to know why he wanted annual leave. Possessed of a good sense of humor, Raphael got the point when Russell told him that "we had some high powered and very expensive Range Management Plans, and nobody to use them." The supervisor authorized Russell to hire a man to help with the scaling, which freed Russell for other duties. [100]

Although most Region 4 mill owners were small operators, a number of large companies operated there too. Perhaps the largest was the Boise-Payette Lumber Company, a Weyerhaeuser subsidiary, organized from the Barber and Payette lumber companies in 1913. By 1916, it operated two major mills at Boise and Emmett, in addition to a number of smaller establishments. The Emmett mill, built in 1916, had a capacity of 200 M per 10-hour shift. The company hauled logs to the mill from the Payette River valley over an Oregon Short Line branch completed in 1915. A large, integrated operation, the mill included three 9-foot single-cutting band saws and double and single edgers. After sawing, the lumber moved to the sorting and stacking sheds, the drying kilns, an unstacking building, and the planing mill. Steam and electricity generated by a steam turbine, presumably fired by lumber scrap, powered the operation. [101]

North of Cascade, the company built the town of Cabarton, named for C.A. Barton, vice president and general manager of Boise-Payette, as its operations center. Boise-Payette had a mill at Cascade as well.

Most logs for the Cascade and Emmett mills were skidded by horse. During the 1920's, the company constructed log chutes up the draws from the railroad and used grease monkeys to keep the chutes slick. [102]

Under the Timber Exchange Act, during the 1920's, the Service began a series of large exchanges of timber for land with the Boise-Payetete trading with Boise National Forest. [103]

|

| Figure 27—Starting down with a load aboard a Boise-Payette Lumber company logging train. |

Tie-hacking operations became especially important on the forests of southwestern Wyoming, particularly the Wyoming and Bridger; eastern Idaho, especially the Targhee; and northeastern Utah, mainly the Wasatch. The Standard Timber Company, organized in 1912 by D.M. Wilt, based in Omaha and closely associated with the Union Pacific railroad, did most of the logging. Tie hacks working for the company were generally Scandinavians and local farmers and ranchers who lived in camps. In the winter months, they hewed logs into ties, In the spring these were driven by stream or flume to loading points. The company paid hackers by the piece. Since they could average 20 ties per day, they cleared, after board, about 96 cents per day. [104] The ties were taken to Pocatello for preservative treatment. [105]

The log drives caused some conflict with ranchers and farmers along the Blacks Fork of the Green River in 1915. Supported by R.H. Fletcher of the U.S. Geological Survey, they alleged that the driving had damaged irrigation works and portions of the river channel. They pressed the Wyoming legislature unsuccessfully to prohibit the drives. In response to the complaints, Standard Timber expended over $15,000 in channel improvement. [106]

|

| Figure 28—Logging chute greaser at a Boise-Payette Lumber company sale, 1923. |

Because the ultimate aim of the forestry work during the early years was to achieve a "normal" forest of good-quality even-aged trees operated on a sustained yield basis, the region attempted considerable reforestation. [107] Greeley expressed his reservations in the mid-teens—in this case about reforestation work on the Manti. [108] The Service found that the plantings were extremely expensive, but the commitment to the European ideal promoted continuation for a number of years. [109] By the end of the First World War, the regional administration, realizing that it did not know how to plant trees successfully, closed its nurseries. [110] By 1923, reforestation had virtually come to a halt in Region 4. In 1927, the Washington Office acknowledged that it could not reforest at a reasonable cost. [111] Into the 1930's some work continued in the States under the cooperative provisions of the Clarke-McNary act. [112]

Fire Protection

Fire undoubtedly evoked more fear among forest officers than any other forest hazard, in part because of experiences in 1910 and 1919. [113] In both years, the extremely dry weather increased the fire hazard and led to fires with tremendous losses of resources, property, and human life in Region 1. [114] Some bad fires also took place in Region 4, although it was not hurt as severely. [115]

After 1910, the Service worked more diligently to develop fire protection plans for each forest. Agreements were reached with local settlers, lumber companies, mine operators, railroad companies, and livestock permittees, to help fight fires. [116]

In addition, the Service began to improve firefighting technology and presuppression. Forest supervisors like Clinton Smith on the Cache set up caches of fire tools, usually shovels, double-bitted axes, and grubbing hoes, throughout the forests with instructions for use in case of fire. [117] The Service pushed for improvements in transportation and communications facilities such as roads and trails and telephone lines and for the placement of lookout towers and fire breaks. [118]

Between 1914 and 1917 lookouts were set up on the Boise and fire guards located at various points. The lookouts had an Osborne fire-finder, based on a setup similar to a plane table and alidade. [119] The guard at Deer Park on the Boise modified saddlebags for use with hand pumps to deliver water on mules for firefighting. [120]

Firefighting techniques improved considerably during the 1920's. A central-dispatcher system originated on the Weiser in 1921 under Lyle F. Watts and Thomas V. Pearson. This system allowed a dispatcher in Council to receive reports from rangers and lookouts and to send fighters to respond. [121] Similar systems were instituted on the Payette in 1922 and in 1925 on the Boise. [122] By 1930, the region made up standard smokechaser outfits, including such equipment as the Koch tool (a handle that could be mounted on either a grubbing hoe or a shovel), and the pulaski, a handle with a head consisting of an axe on one side and a grubbing hoe on the other. Other fire fighting equipment, including a gas operated water pump, was introduced. [123] Some experimental use was made of airplanes for spotting large fires in Idaho, but this was not extensive in Region 4. [124]

Sources of fires varied, but lightning and sparks from railroad locomotives were two of the most common. The Service pressed railroad officials for clearing near tracks, for installing spark arresters, and eventually for the use of petroleum fuel in all locomotives. [125] Though lightning caused most fires in Region 4, these fires were generally not as serious as human-caused ones, since they were generally predictable, coming after thunderstorms. [126]

Not until the 1920's did the region develop standard techniques for fire control. [127] In 1926, the region prepared a fire control manual that it distributed to the forests. [128] By the mid-1920's, various forests, such as the Boise and Bridger, were holding fire training for employees. [129]

No matter what methods were used, firefighting was backbreaking work. In general, the fighters would walk in from the end of a road or from a lookout or guard station. Most were one-man fires where a ranger used "dirt and ambition," camping if necessary, near the fire until it was completely extinguished. [130]

The Service worked on developing cooperative fire prevention programs. By 1930, Idaho was the only State in Region 4 working with the Service in a cooperative program. [131] The 1925 Idaho Forestry Law required all owners of forest land to maintain adequate fire protection. If they did not, the State supplied it and charged the cost to the owners as a tax. [132] This strengthened cooperative organizations such as the Southern Idaho Timber Protective Association. [133]

In recognition of the pervasive danger of fire, insects, and diseases, a number of agencies organized the Regional Forest Protection Board in 1929. The board included representatives of the Forest Service, the Weather Bureau, the General Land Office, the National Park Service, the Bureau of Entomology, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Bureau of Plant Industry, and the Bureau of Animal Industry. [134]

|

| Figure 29—Peeling bark off trees at a tie sale near Evanston, WY, Wasatch National Forest in the 1920's. |

Insect and Disease Control

Although insects, diseases, and pests constituted as real a challenge as fires, they never generated the sort of all-out control responses that fire did. Nevertheless, because they were so unpredictable and devastating, these hazards threatened sustained-yield management. In the period before 1929 the outbreaks of bark beetles and spruce budworm were the worst. [135]

Between 1911 and 1915, an infestation of bark beetle started around Kalispell, MT, and spread down the Continental Divide through the lodgepole pine into the Targhee and Wyoming. [136] The infestation moved south and west from the Targhee. By the early 1920's, beetles had become a serious problem on the north slope of the Uintas, the Middle and South Forks of the Payette, and the South Fork of the Salmon. Infestations then spread through Utah to the Kaibab in northern Arizona. [137] Nevada was not seriously affected. [138]

The Service tried various methods of treatment. At first crews peeled the bark from infected trees like banana skins. When that failed to stem the epidemic, they felled, decked, and burned the trees. They also tried spraying with insecticide or spraying with fuel oil and then burning the oil.

Research on controlling the beetle infestation centered in the Bureau of Entomology field lab headed by James C. Evenden at Coeur d' Alene, ID. The major problems he and his team faced were the extreme expense and limited effectiveness of known treatment methods. More seriously, these treatments also destroyed the beetle's natural enemies. Research revealed a great deal about the beetles, but the team was unable to develop a method of eradication that was both economical and effective. [139] At the time, Evenden thought that treatments had succeeded in minimizing the infestation, but in retrospect, he believed that the infestations may have run their courses anyway. [140]

Evenden and his associates also researched other insects as well. Following the outbreak of the Douglas-fir tussock moth near Sun Valley, on the Sawtooth, they introduced gypsy moth parasites from the Eastern United States into the Idaho colony, with inconclusive results. They achieved some success with spraying the lodgepole pine sawfly on the Targhee, west of Yellowstone National Park. [141]

Forest users complained of other pests as well. Spruce budworms moved onto the Boise and Payette. White pine butterflies were evident on the Middle Fork of the Payette. [142] Foresters declared open season on porcupines, which girdled trees, especially young ones. [143]

Special Use

Special use permits for water power development increased in importance during this period. After 1896, firms that later formed the Utah Power and Light Company began the development of hydroelectric power facilities on various rivers in Utah and Idaho. Acts in 1901 and 1911 authorized special use permits for water power sites, Insisting that the water laws of the States, not those of the Federal Government, applied on Federal lands within a State, the power companies refused to pay fees for special use permits to occupy sites and divert water within the national forests. The Forest Service's challenge to this position took the case to the United States Supreme Court, which ruled in 1917 that the Forest Service had authority to charge for such uses. [144]

By the 1920's, the increase in occupancy of sites for power development had increased the related work of the Forest Service considerably. With the establishment of the Federal Power Commission in 1920, the Service also was burdened with the responsibility for the bulk of the engineering and technical work on sites within the forests. [145]

Other special uses also increased in importance. Many permits were issued for facilities adjunct to stock and lumber operations. Others covered recreation facilities. One burgeoning use was the summer home development. An act of March 4, 1915, permitting the lease of small tracts for summer homes, had extended a law of 1899 which, applying to the Interior Department, confirmed existing Forest Service policy. [146]

In some cases, summer homes conflicted with public recreation uses. On Fish Lake, for instance, the forest officers had considerable difficulty in keeping houses away from the shore so the general public could have access to the lake. Finally, a grandfather clause was established, allowing existing owners to keep their cabins near the lake, but requiring their successors to move. [147]

Recreation

Closely related to special uses were developments in the field of public outdoor recreation. Pinchot had been largely indifferent to recreation, but Graves favored it and in his report of 1912, he recognized recreation as an important forest purpose. [148] In 1915, the regional administration, following precedents in Region 6 and a recommendation from the Washington Office, began to reserve timber for scenic purposes along major highways. [149]

After World War I, as lifestyles changed and people had more leisure time, recreation assumed even more importance. In 1919, Graves called for management plans that provided for "an orderly development of all . . . [National Forest] resources for the use and benefit of the public" including wildlife and recreation. [150] Of particular significance was the increased mobility accompanying the growing use of automobiles. [151] The number of people seeking recreation in the national forests increased from an estimated 2.4 million in 1916 to 6.2 million in 1922.[152] Moreover, during the mid-1920's, the largest recreation increases came in picnicking, transient motoring, and hotel and resort guests rather than in camping, which actually decreased. [153]

Under these circumstances, the Service began even more systematic planning for recreation use. After the creation of the National Park Service, the Forest Service assigned Frank A. Waugh to make studies as a basis for determining policies for the development of national forest recreation facilities. [154] With the exception of Grand Canyon National Monument, then administered by the Forest Service, all of the examples in Waugh's 1918 report were outside Region 4. [155]

In 1922, Waugh came to Region 4 to examine its recreation problems. The study focused on proposals for the development of Bryce Canyon, Cedar Breaks, a Wasatch Mountain drive, the Kaibab Forest, Fish Lake, and what he called "communicating roads" to tie these sites together. Recognizing that most tourists came from local areas, his proposal gave preference to their needs. [156]

The Washington Office tried to meet recreational needs by allocating additional development funds during the 1920's. Beginning in 1923, the Service received small Federal appropriations for construction of camping facilities and, in addition, got money from municipalities and philanthropic organizations for recreation purposes. [157] In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge called a national conference on outdoor recreation, which Greeley supported. [158]

|

| Figure 30—Autos at top of Teton Pass, 1915. |

Even without a systematic national policy, the forests in Region 4 had hosted recreationists long before the 1920's, though specific monetary support was minimal. Perhaps the earliest recreation emphasized water and mountain scenery. Water attractions included lakes such as Fish Lake on the Fishlake National Forest, Payette Lakes on the Idaho, Redfish Lake on the Sawtooth, and Teton Lake on the Teton and rivers such as those in the Island Park country of the Targhee and those flowing from the canyons of the Wasatch front in Utah. In northern Arizona and southern Utah points of focus on the Kaibab, Powell, and Dixie included Grand Canyon, Cedar Breaks, and Bryce Canyon. [159]

Closely associated with recreation policy was the management of national monuments under Forest Service jurisdiction. In the teens, Region 4 operated Grand Canyon National Monument, and after its proclamation as a national park, the region continued to administer the area until the Park Service geared up to take it over. [160] In 1922, Timpanogos Cave in American Fork Canyon became a national monument under the Forest Service. [161] In June 1923, President Warren Harding proclaimed Bryce Canyon a national monument under Forest Service jurisdiction. Following the proclamation, Frank Waugh came to examine Bryce and Cedar Breaks for future recreational development. Waugh's emphasis, as in his earlier report, was on auto-related tourism. [162] A battle between the Forest Service and National Park Service over the creation of a proposed Cedar Breaks National Park occurred during the early 1920's and was settled temporarily in 1933 with the designation of a national monument in the Dixie National Forest. [163]

Another vigorous battle between the Forest Service and National Park Service developed over the Teton-Jackson Hole area. In 1918, Wyoming Congressman Frank Mondell introduced a bill to extend Yellowstone National Park to include the Teton Range, Jackson Lake, and a number of other lakes in the area, Publicly Graves approved the idea, but he had private reservations. Local livestock interests combined with dude ranchers to kill the Mondell bill. In July 1918, President Woodrow Wilson issued an executive order giving the National Park Service a veto over any Forest Service plans for the area. By mid-1923, the livestock-dude ranch coalition had broken down as the guest-ranchers pushed for the transformation of the Jackson Hole area into a frontier-oriented recreational district, a concept somewhat out of line with both the National Park Service mass recreational emphasis that required road and improvement construction and the Forest Service's increasing commitment to multiple use, including recreation. [164] The upshot was the creation of a relatively small Grand Teton National Park in 1929 with the remaining area under Teton National Forest administration. [165]

Wildlife Management

Forest Service policy emphasized proper management of wildlife within the national forests. By congressional mandate, the Service cooperated with local authorities in game protection, especially on game reserves such as those on the Kaibab, Teton, Targhee, Boise, and Fishlake. Until 1916, when the responsibility was turned over to the Biological Survey, the Service worked on the control of predators on the national forests. [166]

The combination of game protection, predator control, and the change in plant communities as a result of livestock overgrazing led to excessive wildlife in some areas. [167] Most notable were undoubtedly the Teton elk and the Kaibab deer herds. Both situations were extremely complex, involving a number of Federal and State agencies.

In the case of the Teton elk, for instance, the Biological Survey raised hay to feed the elk in the winter, but the game laws of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana applied to their management as did Forest Service, Biological Survey, and National Park Service regulations. [168] Eventually, coordination was achieved in part through the creation of an elk commission. Between 1913 and 1916, efforts to control the elk herds included relocation of some to forests in Utah and western Idaho. [169] Disputes developed over the Service's multiple use policy, because wildlife enthusiasts opposed continued livestock grazing within elk habitat areas. [170]

The situation with Kaibab deer was similar. Between 1908 and 1925, the number of deer in the Kaibab herds increased dramatically—from an estimated 8,000 to between 20,000 and 50,000. This situation was more complicated than others largely because Arizona State authorities refused to cooperate with the Forest Service in game management and because of fanciful plans they proposed for relocation of the animals. [171] The Service tried to relocate young fawns, but with only minimal success.

|

| Figure 31—Hunting bear in Mill Creek Canyon, Utah, 1921. |

In another attempt to find ways to control the numbers of deer, which were killing off their own food supply and dying of starvation, Agriculture Secretary Henry C. Wallace appointed the Kaibab Deer Investigating Committee, composed of representatives of wildlife and grazing interests. Some members charged that the livestock were competing too heavily with the deer, but analysis of deer stomach content showed that they ate brush almost exclusively and not the grass and weeds generally consumed by livestock. Walter G. Mann, long time supervisor of the Kaibab National Forest and a keen observer of deer activities on the forest, was a strong advocate of controlling deer numbers through more liberal hunting and other removal measures to keep them in balance with their native forage supply. George McCormick, said to be a knowledgeable old cow hand, and his supporters failed in an attempt to herd the deer across the Grand Canyon. His efforts eventually led to the realization that Supervisor Mann and his Forest Service wildlife specialists were right when they told him that he could not drive deer like cattle. [172]

With no reasonable alternatives left, the Agriculture Department issued an executive order permitting the harvest of excess deer. The Arizona authorities refused to cooperate in this venture and arrested the Service's hunters for violation of State game laws. The Service sought an injunction, which the Supreme Court upheld in Hunt v. United States (278 U.S. 96), affirming the right of the Federal Government to kill animals and ship them from the State to protect the land from injury. The decision, written by Utahan George Sutherland, rested in part on the Utah Power and Light case cited previously.

Land Jurisdiction

In addition to the changes associated with the creation of national parks and monuments, other alterations in forest boundaries came about for agricultural, mining, and urban purposes. Some small forests were consolidated into larger units. [173] The Pocatello, Moapa, Nebo, Palisade, and Fillmore became part of the Cache, Toiyabe, Uinta, Targhee, and Fishlake; and the Santa Rosa and Ruby were consolidated with the Humboldt. [174]

Some interforest transfers took place for more effective administration. One example was the transfer of more than 355,000 acres from the Uinta to the Wasatch in 1915. [175]

Some areas were added to national forests. The addition of the Vernon division to the Wasatch in 1924 under the Clarke-McNary Act is one example. [176] The addition of 1.12 million acres of unreserved Federal lands to the Idaho and Payette in 1919 was probably the largest addition. This addition was made principally to facilitate control of fires that threatened Federal and nearby private lands, to promote development of roads and bridges, and to protect wildlife. [177]

|

| Figure 32—Sublett Ranger Station, Minidoka National Forest. |

Engineering

Roads tended to be cooperative construction ventures. Roads constructed on the Manti and La Sal in 1910 were financed principally by counties and towns, with a small Forest Service contribution. [178] Some roads, such as that crossing Teton Pass from Jackson, WY, into the Teton Basin of eastern Idaho, were constructed in cooperation with the Office of Public Roads, then an Agriculture Department bureau. [179] Acts in 1912, 1916, 1919, and 1921 provided some funds for forest and near-forest roads, for Federal highways through forests, and for trail construction. [180]

In the first decades of the twentieth century, engineering work tended to be relatively simple. When Arval Anderson, later regional engineer, started as a junior engineer in the 1920's, engineers generally had little to do except to design trails and a few simple roads and do some mapping. [181] Sterling Justice indicated that the Caribou had only a horse-powered road grader in 1921. [182] George Kreizenbeck remembered that roads and trails were constructed to a very low standard. Generally the buildings on the forests were one- or two-room log cabins, with no inside plumbing. After World War I, the Payette National Forest had a couple of obsolete trucks and a tractor; by 1930, they had three tractors and a motorized road grader. [183]

During this period, the most extensive Forest Service improvements tended to be telephone lines, rather than roads or trails. In general, the lines were ground-return systems strung from tree to tree through the forest or on poles where trees were unavailable. These lines were generally built by the rangers themselves. [184] Rangers also constructed cabins, lookouts, bridges, fences, and other structures and improvements. [185]

Summary

By 1930, Region 4 was still far from achieving its goals in the fields of timber management and other functions. The adoption of silvicultural prescriptions on the European model seemed quite distant. The lack of adequate funds made difficult, if not impossible, the achievement of acceptable progress in watershed, recreation, or wildlife management. Moreover, the failure of the public to perceive that the Service had reached de facto multiple-use management, including recreation and wildlife management, brought about the transfer of national forest recreational areas to the National Park Service as soon as they achieved national prominence.

Nevertheless, some bright spots existed. Most important was the establishment of precedents facilitating proper stewardship in special uses and wildlife management through the Utah Power and Light and Kaibab deer cases. Unfortunately, the problems associated with range management were even more serious than those in timber management.

|

| Figure 33—Using a pitsaw at Cold Meadows Ranger Station, July 1925. |

Reference Notes

1. Hereinafter, in order to avoid confusion with ranger districts, the term "region" will be used in this study even though the change was not officially made until the late 1920's.

2. Harold K. Steen, The U.S. Forest Service: A History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1976), pp. 100-102; Lawrence W. Rakestraw, A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest (New York: Arno Press, 1979), p. 273. Perhaps the best study of the Ballinger-Pinchot affair is James Penick, Jr., Progressive Politics and Conservation: The Ballinger-Pinchot Affair (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968).

3. Alumni Bulletin: Intermountain District, 1930, File: Alumni Bulletin, Historical Files, Dixie.

4. Leon F. Kneipp, "Land Planning and Acquisition, U.S. Forest Service," interview by Amelia R. Fry, Edith Mexirow, and Fern Ingersoll, 1964-65 (University of California, Regional Oral History Office, 1976), pp. 18, 79-82.

5. Kneipp, "Land Planning and Acquisition," pp. 18, 20-31, 24, 82.

6. C.N. Woods, "Thirty-seven Years in the Forest Service," MS, n.d., File 1680, History, Historical Files, Regional Office, p. 36.

7. Certificate, August 14, 1929, File: O- Quarters, Regional Office Building, 1929-1930, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

8. R.H. Rutledge to W.H, Shearman, April 12, 1926, File: O-Quarters-Regional Office Building, 1926-1928, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC; T.V. Pearson, Memorandum for the Files, July 13, 1926, ibid.; T.V. Pearson, Memorandum for the Files, November 27, 1926, ibid; R.C. Beckstead, Memorandum for the Files, November 29, 1926, ibid.; Ed Jessop to Forest Service, February 11, 1927, ibid.; R.C. Beckstead, Memorandum for Operation, December 15, 1926, and November 30, 1926, ibid.; HCB, Memorandum for Mr. Pearson, June 14, 1927, ibid.; W.H, Shearman to Howard C. Baker, August 22, 1928, ibid.; T.V. Pearson, Memorandum for the Files, August 26, 1929, File: O- Quarters, Regional Office Building, 1929-1930, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

9. Alumni Bulletin District 4, 1927 (n.p. [Ogden]: [District 4], 1927), p. 1. The number of rangers had declined by 28 percent from 189 to 137. The number of clerks and auditors in the district office had declined from 29 to 17, a 41-percent drop.

10. Woods had previously served as an inspector in grazing, as chief of lands, and as chief of lands and grazing. See L.F. Kneipp to the Forester, April 16, 1919, and Albert F. Potter to L.F. Kneipp, April 23, 1919, File D- Organization-General, 1905-1929, Historical Files, Regional Office, and C.N. Woods, "Thirty-seven Years in the Forest Service," p. 35.

11. Alumni Bulletin District 4, 1927 (n.p. [Ogden]: [District Office], 1927). p. 32.

12. Forest Service Report in Agriculture Department Report, 1911, p. 345.

13. Alumni Bulletin, 1927, pp. 33-36.

14, See Herbert Kaufman, The Forest Ranger: A Study in Administrative Behavior Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1960).

15. S. Edwin Cazier, The Last Saddle Horse Ranger (Logan, UT; Educational Printing Service, 1971), p. 83.

16. Charles S. Peterson and Linda E. Speth, "A History of the Wasatch-Cache National Forest" (MS, Report for the Wasatch-Cache National Forest, 1980), p. 95.

17. District Four, "Minutes of Supervisors' Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests," 1910, pp. 281-83.

18. William Miller Hurst, Thinking Back: An Account of the Author's Forest Service Experience in Southern Utah (n.p., n.d.), p. 23. See also A.R. Standing, "Memorandum on Work in the Forest Service, " January 4, 1962, Historical Files, Fishlake.

19. W.E. Tangren, interview by Arnold R. Standing, April 21, 1965, pp. 3-4, Historical Files, Fishlake.

20. Emile Grandjean, "A Short History of the Boise National Forest" MS, Historical Files, Sawtooth, p. 10,

21. Woods, "Thirty-Seven Years in the Forest Service," p. 30.

22. Leo E. Fest, interview by Elizabeth Smith, Boise December, 1974, p. 7, Historical Files, Boise.

23. Elizabeth Leflang Sliger, "Emile Grandjean, One of the First Forest Supervisors," MS, Historical Files, Sawtooth, p. 3.

24. Victor K. Isbell, Historical Development of the Spanish Fork Ranger District, ([Spanish Fork, UT]: Spanish Fork Ranger District, 1974), p. 41.

25. J.W, Humphrey, interview by Arnold R. Standing, April 1965, p. 7, MS, Historical Files, Fishlake.

26. Woods, "Thirty-seven Years in the Forest Service," p. 34.

27. Harry H. (Rip) Van Winkle, interview by Arnold R. Standing, Jackson, WY, June 1965, p. 20, Historical Files, Regional Office. Tangren interview, p. 1.

28. The consideration of problems of personnel is based on: J.B. Lafferty, "Forest Personnel," and the discussion among supervisors which followed in District Four, "Minutes of Supervisors Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests, Boise, Idaho, January 2-4, 1910 [sic should be 1911]" (n.p., 1911), pp. 249-257. Historical Files, Boise.

29. On this point see: William M. Anderson, "Forest Personnel" in District Four, "Minutes of Supervisors' Meeting, Utah and Nevada Forests," 1911, pp. 215-217 and the discussion that followed.

30, District 4, "Minutes of Supervisors' Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests," 1911, pp. 273-79.

31. District Four, "Minutes of Supervisors' Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests," 1911, pp. 257-265, 268-273. Sterling R. Justice, The Forest Ranger on Horseback (n.p., 1967), p. 86.

32. File: D (0), Personnel, Pack, W.I., "Memorandum of Discussion of Above Case Held November 24, 1913," E.A. Sherman to W.I. Pack, November 25, 1913, Henry S. Graves to District Forester, December 4, 1913, and Sherman to Graves, December 28, 1913, File: 1658- Historical Data 15- Personnel, Uinta. In a 1908 inspection on the Uinta, F.W. Reed discovered that Deputy Supervisor Dan S. Marshall had been careless and ineffective in answering correspondence and submitting reports. He was reassigned as a ranger. Clyde Leavitt to Dan S. Marshall, December 18, 1908, File: 1658-Historical Data- 15, Personnel, Uinta,

33. Woods, "Thirty-seven Years in the Forest Service," pp. 30-33. In another case, by mapping a ranger s movement from diary entries, Woods showed that he was not covering his district, he was not inspecting the grazing allotments regularly, and he was spending too much time in town. The ranger was dismissed, but he gathered sufficient evidence of drinking to force his supervisor's resignation as well. After a 1915 inspection of the Santa Rosa, Woods found that the rangers were spending only a third of their time on the grazing allotments. He considered that far too little, since the forest had virtually no other activities. C.N. Woods, Memorandum for the District Forester, October 30, 1915, File: Inspection—Humboldt, 1909-1915, Humboldt.

34. L.F. Kneipp to Guy B. Mains, February 1, 1916, File: G- Inspection, Boise (Payette), 1904-1929, Lands and Recreation Library, Regional Office.

35. James O. Stewart, Memorandum for the District Forester, June 6, 1927, File: Regional Office, 1927, Box 4993, Toiyabe National Forest Records, RG 95, San Bruno FRC.

36. Arlene Burk, interview by Thomas G. Alexander, February 6, 1985, Historical Files, Regional Office.

37. On the establishment of the division see Jenks Cameron, The Development of Governmental Forest Control in the United States (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1928), p. 312.

38. Peterson, "Wasatch-Cache," p. 254.

39. Justice, The Forest Ranger on Horseback, pp. 47, 84.

40. Edwin Cazier, interview by Arnold R. Standing, Afton, WY, May 1965, p. 6. Historical Files, Regional Office.

41. Sherry H. Olson, The Depletion Myth: A History of the Railroad Use of Timber (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971), pp. 141-54, Forest Service Report in Agriculture Department Report, 1919, p. 178; 1920, p. 222; 1922, pp. 243-44; 1923, p. 290; I929, p. 3.

42. George P. McCabe to Henry S. Graves, April 19, 1912, File: S-Sales-General, 1912-1923, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

44. John Raphael to District Forester, March 24, 1919, File: S- Supervision, Fishlake, 1924-1950, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

45. O.M. Butler, "District Market Plan, District 4," pp. 1-13, File S-Supervision-General, 1912-1915, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC. For sales from each of the district's forests in 1913 and 1914 see Table 6.

46. W.W. Blakeslee to District Forester, February 26, 1919, File: S-Supervision, Toiyabe, 1919-1950, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

47. C.E. Favre to District Forester, March 4, 1919, and C.B. Morse to H. Wisener Hammond, October 29, 1921, File: S- Supervision, Humboldt, 1919-1920, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

48. J.W, Humphrey, "My Recollections of the Manti Forest," p. 6, Historical Files, Manti-LaSal.

49. "Minutes of Supervisor's Meeting, Utah and Nevada Forests, 1911," pp. 49, 236-37,

50. "Minutes of Supervisor's Meeting, Utah and Nevada Forests, 1911," pp. 47-49. "Minutes of Supervisor's Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests, 1911," pp. 161-65.

51. "Minutes of Supervisor's Meeting, Utah and Nevada Forests," pp. 52-53.

52. W.B. Greeley to L.F. Kneipp, June 23, 1915, File: S- Sales- General, 1912-1923, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

53. For a statement of general policy see: Forest Service Report in Agriculture Department Report, 1910, pp. 382-85.

54. C.E. Dunston, "Reconnaissance of the Targhee National Forest, Idaho-Wyoming, 1910," pp. 1-3, File: S-Plans, Timber Surveys—Targhee Report by C.E. Dunston, 1910—and Working Plan by Peters and Boison (1910), Targhee National Forest Records, RG 95, Seattle FRC.

55. Dunston, "Reconnaissance of the Targhee," pp. 3-4.

56. Dunston, "Reconnaissance of the Targhee," pp. 38-42.

57. Dunston, "Reconnaissance of the Targhee," p. 43.

58. Dunston, "Reconnaissance of the Targhee," p. 47.

59. Dunston, "Reconnaissance of the Targhee," pp. 52-53.

60. Samuel W. Stoddard to District Forester, March 6, 1919, File: S-Supervision, Targhee, 1906-1950, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC.

61. C.B. Morse, Memorandum, August 4, 1925, File: S-Supervision, Targhee, 1906-1950, Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver, FRC.

62. D.M. Lang, "Report on the Forest Resources and Logging Conditions, Teton National Forest, Wyoming, 1911," and H.B. Maris, "Supplement to the Report of D.M. Lang," MS 1912, File: S- Plans, Timber Surveys- Teton, 1908-1950, Regional Office Records, Denver FRC.