|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 5

Range Management and Research: 1910 to 1929

While various activities helped to promote a favorable image for the Forest Service, many resource management and public relations problems derived from range management, which was undoubtedly the most difficult and pervasive problem with which Region 4 officers had to work. Unlike timber where they managed an abundant resource with a small demand, in range management, demand far exceeded supply. Forest officers had to work against enormous pressure to reduce livestock numbers and seasons of use to the carrying capacity of the range. This required a continuation of the measures begun during the early years of forest administration, including working with stockmen's associations and individual permittees, monitoring the condition and trend of the range and of animals leaving it, subjecting the operations to periodic inspections, critiquing grazing methods, and striving for support through periodic meetings.

Region 4 managed the most range in the National Forest System. In 1927, the net land area was 28 per cent greater and the net usable national forest range (21.8 million acres) was 21 percent greater than any other region. Though lower in animal months for cattle and horses than Region 2 (Colorado and Wyoming) or Region 3 (Arizona and New Mexico), it grazed more of the two species at 386,553 than any other except Region 2. With 8.9 million animal months of sheep (at 4:1 sheep to cows, the figure then used), no other region even came close to the numbers in Region 4. [1]

In an attempt to provide more effective range management, between 1910 and 1929 the Intermountain Region passed through three phases. Between 1910 and America's entry into World War I in 1917, the Service began systematic evaluations of range conditions. This was done through range reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies. In addition, managers tried new techniques, such as bedding out sheep and rotation and deferred grazing, to improve range lands. In 1917 and 1918 the region slowed down these studies and tried to increase meat production through additional overstocking of the range, promoted by the Washington Office. [2]

A sharp depression followed an immediate postwar boom, and the period from 1919 through 1929 witnessed a number of changes in management. These included the inauguration of period studies, designed to determine the date at which stock should be allowed to enter and leave the range, and palatability studies to catalog preferred plants. In addition, the Service tried to revise fee schedules upward to place them more in line with the actual value of the range. During the same period, stockmen mounted the first of a number of attempts to gain control over national forest grazing lands.

Controlling Numbers of Stock

Perhaps the status of range management at the beginning of the period was best summarized in meetings held for supervisors at Boise and Ogden in January 1911. [3] In the Boise meeting a major part of the discussion concerned the extent of stocking that ought to be allowed. The opinions of the supervisors diverged greatly. A number of them, led by C.N. Woods of the Sawtooth and including Guy Mains of the Payette, J.B. Lafferty of the Weiser, J.E. Rothery of the Idaho, Emil Grandjean of the Boise, and Dan Pack of the Palisade, believed that foresters ought to pay particular attention to the condition of the grazing land itself. Woods argued that the range ought to be considered fully stocked when use reached three-fourths of presumed capacity. The most vocal opposition came from David Barnett of the Targhee and N.E. Snell of the Caribou. They thought forest officers ought to stock to the range's full presumed capacity, reduced only to mitigate potential damage to timber reproduction and watershed. Under this conception, herders would have to remove their animals after they ate all the forage whether this occurred early or late in the season. Several of the supervisors did not express themselves on the question, but Woods's proposition lost by an 8 to 9 vote. [4]

Although the Secretary of Agriculture nominally granted permission for the numbers of stock grazed on each forest, he based his decision on the recommendation of the supervisor, the approval of the regional forester, and whatever information previous inspections had revealed. Until the supervisors had access to the results of reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies to formulate plans they based most recommendations on precedent and user pressure.

In many ways, the situation in 1911 on the Caribou epitomized the problems in the region. Early in the 1911 grazing season, Forest Supervisor George G. Bentz had asked special approval for permittees to graze 322,000 sheep on the forest, since three former permittees had failed to submit their requests on time and he wanted to accommodate them. Sherman disapproved the request. [5] Later Bentz admitted that even "320,000 head is considerably in excess of the number the range will support without injury." Nevertheless, he said, "It is not deemed advisable . . . to recommend a reduction in the allotment at this time because of the 50,000 cut made last year, and because of the adverse [economic] conditions surrounding the sheep business of today." He proposed, instead to take "advantage" of "forfeitures, lapses of permits, and reductions made on transfers," where the reduced numbers were not needed for permittees below the protective limit and for new Class A permittees. Still, he believed that more cattle actually grazed on the forest than the 7,000 permitted, and apparently in response to user pressure, he recommended that if that proved to be the case, "an increase in the allowance of cattle will be necessary." [6]

The general trend of stocking on the Caribou was quite consistent with the pattern throughout Region 4. By 1916 numbers of sheep had been reduced to 290,000 and cattle had been increased to 13,200. Nominally, the grazing season could last as long as all year for cattle and horses and from May 15 to September 15 for sheep. [7]

Range Reconnaissance and Carrying Capacity Studies

Range reconnaissance began in the Forest Service in 1910 and in Region 4 on the Targhee in 1911, the Manti in 1912, and the Caribou in 1913. [8] Since these studies could proceed only with available limited funds, carrying capacity studies had been done on only five forests by 1915. [9] Many forests did not get them until the 1920's, and some not then.

The reconnaissance itself consisted of a survey resulting in a map and description of land and vegetation of the area studied, much like a timber cruise. Grazing examiners used the Geological Survey maps where possible, but where such maps were unavailable, they often made form line maps, using control points established by the Division of Engineering and a plane table, alidade, and Abney level. In addition, the examiners collected plants for a forest herbarium, estimated the percentage of each plant and the palatability of various species in the surveyed area. [10]

Carrying capacity studies followed the reconnaissance. Carrying capacity was defined as "the minimum acreage required to maintain a foraging animal in good, thrifty condition through the grazing season stipulated," and the studies proceeded in two phases. One consisted of various long-range sample plot measures of trend and the other secured immediate data by measuring the weight gains of animals. [11]

During the period to 1929, perhaps the most careful investigations in the entire national forest system took place on the Caribou. There, examiners intended "to conduct tests on every distinctly different and representative unit of the range." This required the cooperation of sheepmen to a greater extent than before, since they now had to graze in "accordance with a definite plan" rather than as they wished. Expecting each study to last over a 3- to 5-year period, Fenn said it would "be considered complete when sufficient data has been collected to serve, together with the reconnaissance data, as a basis of an intensive plan of grazing management for every part of the Caribou Forest and as much range on neighboring forests as similarity of conditions will permit." [12]

In general, the method of determining carrying capacity was worked out by Arthur W. Sampson of the Great Basin Experiment Station, James T. Jardine of the Washington Office, and Mark Anderson, grazing examiner. They incorporated the data gathered on the Caribou and other forests in published studies. Anderson began work on the Caribou in 1913, a forest ranger took over in 1914, and Clarence E. Favre and W. Vincent Evans, with the assistance of C.H. Shattuck of the University of California and R.E. Gordon, expanded the studies in 1915 and 1916. The 1913 and 1914 studies consisted of selecting a few test allotments and measuring the weight gain of lambs grazed under prescribed conditions. [13]

|

| Figure 34—Great Basin Experiment Station, winter 1913. |

The 1915 studies under Favre's direction and those in 1916 under Favre and Evans were much more extensive. These included animal weight measurements and the establishment and carefully controlled harvest of sample plots consisting of eight quadrats and two seasonal variation enclosures on each of five allotments. The quadrats were square divisions of various sizes, though for intensive studies meter square units were used. [14] Favre and Evans charted the plant types in each quadrat and photographed them. [15] They harvested the plants on the 10 enclosures twice during each year and weighed them, both green and dried. Sampson considered enclosures particularly important to determine the rate of revegetation.

Favre and Evans achieved essentially two results: they determined the forage area required to feed a sheep, and they reported on the method of grazing best adapted to Caribou conditions. In evaluating their work, Homer Fenn considered the "reconnaissance and supplemental studies conducted on the Caribou . . . the most intensive and systematic range inspection that has ever been made of a Forest."

By World War I, Shattuck could cite the Caribou as a model of range management. [16] During the mid-1920's, rangers were brought to the Caribou to "see how other rangers were handling problem's similar to those . . . on [their] own districts." [17]

With data from such reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies, Sampson, Jardine, and Anderson proposed a standard forage acre as the determinant of proper stocking. This measure took the total land area multiplied by the fraction of surface supporting vegetation, the fractional density of cover, and the percentage of palatable forage. Thus, an area of 80 acres covered with 70 percent vegetation, with a density of 80 percent, and with 80 percent of the area covered with palatable vegetation would equal 36 forage acres. [18] On the Caribou, Favre's experimental results determined that a mature sheep needed 0.78 forage acre for a grazing season. [19] This figure was close to the 0.79 figure that Jardine and Anderson found when averaging a number of similar studies for a season of 72 days. They reported that a mature cow needed 2.65 forage acres per season of 100 days. [20]

The weather played an important part in determining the carrying capacity of the range. After a period of abnormally wet years from 1905 through 1909, the climate from 1910 through 1920 was, on the average, much drier than normal. [21] The years 1910 and 1911 were two of the driest on record. [22] 1912 was quite wet and 1913 and 1914 were moderately so; the remainder of the decade was quite dry. The 1920's, on the other hand, tended to be generally wetter than normal.

Grazing Prescriptions

After their studies, Evans and Favre also tested suggestions Sampson had made, based on experiments in Utah and Oregon. Sampson proposed that stockmen defer grazing until the seed crop had ripened to produce a greater volume of feed and more vigorous plants. He had also found that when stockmen rotated animals from one portion of the allotment to another in different annual cycles, the plants generally grew better. [23]

Evans and Favre believed Caribou ranges to be unsuited for deferred and rotation grazing. "Where there is an extreme diversity of types and a considerable range of altitude on each allotment," they said, "it is particularly difficult to secure a division of allotments into rotation areas that will conform to the best use of the range and that will provide a uniform amount of forage per allotment each year." With regard to deferring, "with grasses," they agreed, "it appears to be true that there is no very rapid deterioration in food value for some time after physiological maturity, . . . the same [was] not true of most palatable weeds." On weed range like the Caribou, they noted "a rapid decay in food value after maturity, so much so that sheep will prefer" living browse "much inferior in mutton-producing qualities" to the weeds. On a practical level, they found both systems difficult to implement, since they required "an extra large amount of supervision," which was not available. Nevertheless, they recommended deferred grazing "in those cases where, through internal mismanagement of the range, areas are overgrazed." [24]

Conditions were not uniform throughout the region. On some of the less steep allotments on the Targhee, by contrast, deferred and rotation grazing had been put into practice by World War I. [25] On the Sawtooth deferred grazing could be practiced, but rotation seemed impracticable as late as 1928 because reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies had not been completed on the forest. [26] Charles DeMoisy used rotation grazing on the Ashley. [27]

Favre's objection to deferred and rotation grazing on the Caribou was practical rather than ideological. By the late teens he had been appointed supervisor of the Humboldt, with the largest grazing load of any forest in the entire Forest Service. There, with decidedly different conditions than the Caribou, he instituted deferred and rotation grazing. [28]

In the absence of grazing reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies, the forest officers based their decisions on hearsay and observations. Mark Anderson assumed 0.53 forage acre per sheep on the Sawtooth in 1914, and Clarence Woods estimated 5 forage acres per cow as a rule of thumb in an inspection of the Minidoka in 1915. [29] Moreover, in the absence of reliable data, stockmen were likely to overestimate the value of the range by relying on their memory of past conditions or to insist on counting oak-brush or other browse species in determining carrying capacity. [30]

Because assigning specialists to do reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies like those on the Caribou was relatively expensive, the regional office could not afford to have these studies done everywhere. In an attempt to provide data for range management, some forest supervisors provided their own studies or enlisted the help of regional personnel for limited periods. Supervisor Guy Mains had his rangers do a reconnaissance on the West Mountain district of the old Payette. [31] Forest officers undertook similar limited studies on the Santa Rosa and Toiyabe in 1915. [32] Fenn, however, vetoed a proposal by Woods and Wyoming Supervisor James Jewell to have forest personnel establish sample plots in 1914. [33] Fenn's attitude may have changed somewhat late in his administration.

Woods and his assistant, Ernest Winkler, definitely felt differently and approved local reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies. [34] In 1923, general instructions from the Washington Office placed primary responsibility on the forest supervisor, for such studies "to meet local needs." [35]

At times, supervisors expected scientific research to overcome problems that only reductions in stocking could solve. [36] On the Nevada, in 1915, Supervisor George Thompson increased the permits of Class B stockmen on overgrazed range. He apparently, but erroneously, believed that an extensive grazing reconnaissance could resolve many of his problems. [37]

Two seemingly contradictory conditions existed on many of the forests, both of which resulted from the conflict between efforts of forest officers to reduce numbers of livestock from the range and at the same time to provide range for new permittees and accommodate the pressures from stockmen for predictability of permitted numbers and seasons. Some ranchers grazed below their permitted numbers (usually of sheep), while others consistently put more stock (ordinarily cattle) on the range than permitted. In an inspection of the Sawtooth in 1916, C.N. Woods criticized Supervisor Miller S. Benedict for allowing up to 2 years nonuse of permitted numbers. At the same time, Woods found some permittees grazing more stock than permitted because of lax enforcement by forest officers. [38] Benedict said that this had happened because in trying to provide range for qualified applicants, he had allotted a smaller area to established permittees than "needed for the preference number with the understanding that the permittee concerned would have to utilize it as best he could by shorter grazing season or by running part of his sheep outside the Forest." [39] Inspections found similar patterns on a number of forests, including the Boise, Uinta, Wyoming, Santa Rosa, and Ashley. [40]

Nevertheless, in the interest of protecting the range or distributing it to new permittees, the supervisors pressed for reductions. These reductions bore most heavily on larger stockmen and often caused anguished outcries. [41] On the Cache in 1910, for instance, Clinton Smith had an authorization to permit 93,000 sheep. Even though he reduced the number of permittees above the 1,000 protective limit as much as 20 percent, he had 73 percent more applications than places to distribute to present and new permittees. [42] In another case, after an inspector had divided the range between two permittees, one became quite dissatisfied, and C.N. Woods came from the district office to investigate. "Your man divided the range between us," complained the stockman, "It's ridiculous. He didn't give me enough forage for a jack rabbit." After reviewing the situation, Woods thought the forest officer "had done a pretty fair job." [43]

The problem of distributing permits to stockmen was closely related to the issue of commensurability. On the Uinta in 1928, for instance, commensurability rules for cattle and horses required croplands capable of providing a ton of hay per head or "its equivalent in other forage crops," or privately owned pasture to feed stock for at least 90 days while they were off the forest. For sheep, the requirement was sufficient cropland or spring, fall, or winter range to provide forage for each sheep at least 75 days while off the forest. Pasture land was at such a premium that only those living in valleys immediately adjacent to the forest could hope for permits for their stock. [44]

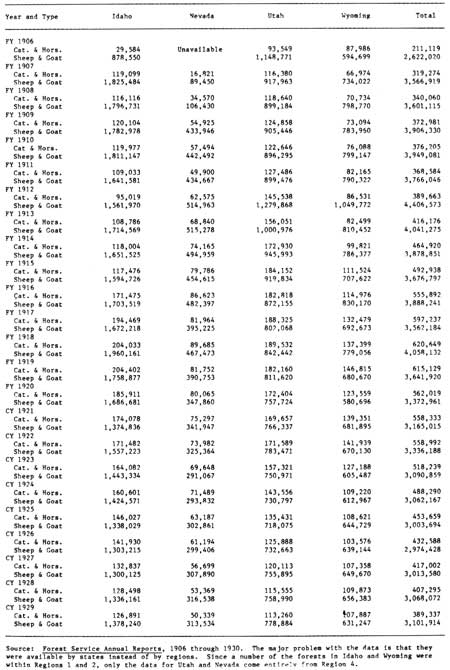

Table 7—Number of livestock under grazing in Idaho, Nevada,

Wyoming, and Utah, 1906-1929.

(click on image for a PDF version)

In 1910, because of the excessive overgrazing on the Manti, A.W. Jensen reduced the permits of old users and allowed virtually no new stockmen on the forest. In order to allow more graziers to keep sheep on the forest, he had set the protective limit at 500 (later reduced to 200), undoubtedly the lowest in Region 4. Even at that, many who owned sufficient base property to feed their stock during the winter could not obtain permits. Jensen had granted 5-year term permits in 1909, so the reductions caused considerable resentment. Though Jensen tried to protect small stockmen, the farmers interpreted his actions as an attempt to promote the interests of large owners, and they held several meetings to protest Forest Service policy. As late as 1912 Jensen had failed to satisfy the grazing advisory boards. [45]

Differences of opinion emerged over commensurability requirements. In 1911, W.I. Pack of the Uinta, Orrin C. Snow of the Sevier, and Henry A. Bergh of the La Sal argued against commensurability requirements, saying that they discriminated against small operations. [46]

E.A. Sherman disagreed quite strongly, believing that dropping the requirements would create a property right in the grazing privilege. Carl Arentson of the Fishlake and Clinton G. Smith of the Cache agreed with Sherman, arguing that the commensurability rules protected the small rancher from competition for permits with the large operator who might graze on the forest in the summer and the desert during the winter. [47] The dispute arose again in 1912 on the Ashley, and Sherman again ruled in favor of commensurate property qualification. [48]

In practice the presence of small or large stockmen was less a function of the commensurability rules than of grazing conditions and protective limits on and near the particular forest. [49] The Manti, for instance, contrary to the charges leveled at Jensen, hosted mostly small farmers, and Forest Service publications cited the forest as an example of the success of their social policy that promoted small holdings. [50] Most permittees on the north slope of the Uinta, on the other hand, were large operators. [51] On the Humboldt, C.S. Tremewan resigned in protest after Sherman followed what the supervisor perceived to be a policy of raising the preferences for larger operations and reducing the smaller units. [52] The evidence on Tremewan's allegations is somewhat mixed since by 1915 the protective limit for sheep had been reduced from 2,000 to 1,250, while the maximum limit had increased. [53] As regional forester, Kneipp was decidedly against control by large operators, and he warned Supervisor J.M. Ryan of the Ruby against granting permanent increases to larger permittees. [54] In 1919, Kneipp cautioned Toiyabe Supervisor Vernon Metcalf against continuing to allow a large permittee to graze double the forest's established maximum limit of stock. [55]

In an effort to help small permittees, the Sawtooth and some other forests created class A zones near the forest boundary and refused to allow anything but a B or C permit even to qualified stockmen who lived further away. In 1916, under pressure from Senator William E. Borah, in part because of complaints of conditions near the Sawtooth, the Chief abolished the class A zone so that any owner "of improved ranch property, who is willing to drive his cattle from the ranch to the Forest ranges and back again each season" could get a class A permit if range capacity permitted. [56]

To avoid loss of an allotment for distribution to other ranchers, some sheepmen believed that it was actually advantageous to overgraze. In his inspection of the Humboldt in 1911, A.C. McCain found some permittees who thought that "the only way to be sure of their allotment not being reduced in area is for them to graze it out to such an extent that is is, if anything, just a little over the line between a conservatively grazed range and an overgrazed one." They said that if they handled their stock properly and their allotment was found to be in good shape, they ran "a very great risk of . . . having a piece chopped off and given to some less careful man." [57]

On occasion, Forest Service officials themselves promoted overgrazing, by basing recommendations on dubious theories. A 1915 inspection of the Humboldt found "extensive" grass areas in some portions of the forest. Homer Fenn suggested that "a much higher carrying capacity and a more uniform production of forage plants may be secured [in such a case] by common use by both sheep and cattle." The reason, he said "is that weeds are more palatable to sheep and grass more palatable to cattle, with the result that the nongrass-like plants are not fully utilized by the latter class of stock, while the same is true of grasses on the sheep ranges." In defense of his argument for common use, he pointed out that on the Powell, "grass ranges have been converted into weed ranges and weed ranges into grass ranges by continuous heavy grazing by one class of stock." [58]

Some observers considered this "surplus" grass in northern Nevada a range conservation blessing rather than an opportunity for greater stocking. In retrospect, W.E. Tangren said that the large percentage of grass range was a major reason "for the less deterioration." [59]

Controlling Trespass

The forest supervisors experienced a greater problem in controlling grazing trespass than timber trespass in part because they had to handle it differently. In timber trespass cases, the ranger could estimate the damages, assess them on the spot, and, if the trespasser agreed to pay, transmit a proposition through the supervisor to the regional forester for approval. In the case of grazing trespass, the ranger had to collect affidavits adequate to allow successful prosecution by the United States Solicitor General.

In practice, this meant more time and paperwork for the forest officers and fewer payments for damage. When confronted by the ranger, the herder would generally offer to settle the matter, but after learning that the ranger had to supply affidavits and admissible testimony, the trespasser often reneged. Then for cases resting on hearsay or the unsupported testimony of the ranger, the solicitor would not approve prosecution. Consequently, the supervisors proposed that the Federal Government change the rules in grazing trespass cases to allow rangers to accept settlements with the approval of the regional forester in cases of less than $250 in damages. [60]

In general, permittees resented measures taken to secure compliance with trespass regulations, whether fines or revocation of permit privileges—even though they were infringing on the rights of other permittees or damaging the range. [61] The regional administration sent Chester J. Olsen to the Humboldt in the 1920's for an investigation that led to the successful prosecution of nine trespassers by the Justice Department. [62] The creation of the La Sal National Forest had had the support of smaller stockmen, but the larger ranchers, who controlled most of the range, did not like the restrictions on their operations and often disregarded the trespass regulations. [63] On the Fishlake, trespass became a problem in part because of large blocks of private land within the forest, which made it difficult to control drifting. [64] On the Cache during the mid-1920's, Carl Arentsen found that on-and-off permits contributed to trespassing. He dealt with this problem by fencing the boundaries and reducing the number of permits. [65] In attempting to control trespass, rangers conducted wintertime, feedlot, and ranch counts, rode the range, bushed the tails of unpermitted stock painted the excess stock, and tagged permitted stock. [66]

In some cases, the supervisors just gave in to the pressure. On the Minidoka, cattle trespass became such a difficult problem to solve that in 1915 stockmen were allowed to readjust their allowances to the average numbers they had actually been grazing on the forest. This did not solve the problem, however. On the Toiyabe trespass became so pervasive by the mid-teens that the supervisor required all permittees to sign affidavits stating the number of stock they actually grazed, then issued temporary permits for the stock in excess of regular permitted numbers. The regional administration prohibited temporary permits after 1919, so the practice had to stop. [67] Perhaps because of the vigorous efforts to deal with the problem, by 1926, the trespass situation in Region 4 was, on the whole, better than in other regions. [68]

Stock Driveways

A major difficulty on many of the forests came in the administration of stock driveways. Stockmen generally drove their sheep or cattle from the ranch to the forest over such routes. Overgrazing on and near the driveways was a concern, as was proper posting to ensure that stock moved across the driveways quickly with as little damage as possible. In an inspection on the Targhee in 1918, Ernest Winkler was surprised by the good condition of one driveway over which 70,000 to 80,000 sheep were driven each season. [69] In an inspection of the Sawtooth in 1918, Grazing Chief Homer Fenn found a particularly bad driveway along a ridge. [70]

The driveway situation in Idaho was also critical because of the practice of marketing lambs in the middle of the grazing season. This practice required driving the sheep along the route four times per year, instead of two as in most other areas, causing particular pressure on the driveways. [71]

In Utah, perhaps the worst situation existed on the Lakefork driveway on the Manti. There, the earth was so denuded that erosion had become endemic. Moreover, there seemed no alternative if grazing were to continue in the area, according to C.E. Rachford of the Washington Office's grazing division, who inspected conditions in 1926. [72]

By the late 1920's, some permittees were beginning on their own initiative to haul lambs to the railroad and to truck ewes and lambs to their grazing grounds. In 1928, J.W, Newman, a permittee on the Boise, Challis, and Sawtooth, used an REO speedwagon converted to a double-deck truck to carry as many as 68 lambs on each trip between the Middle Fork of the Salmon River and the railhead at Ketchum. [73]

Grazing Advisory Boards

At the 1911 supervisors" meetings, the participants discussed grazing advisory boards. [74] Speaking for the regional administration, Fenn pointed out that the Service had a great deal less trouble in Idaho than in Utah. He attributed the difference to "advisory boards entirely," and to "the mutual feeling that results from the cooperation and the understanding of the parties concerned." [75] With the exception of E.H. Clarke of the Wasatch and A.W. Jensen of the Manti, the Utah supervisors had not organized advisory boards, and most were decidedly against them. W.I. Pack of the Uinta feared that boards would interfere with his administration, and others discounted their value for similar reasons. After Pack's removal, Jensen organized advisory boards on the Uinta, but he ran into considerable difficulty in securing their cooperation. [76] Following the 1911 supervisors' meeting the La Sal stockmen organized a board. [77] As late as 1915, the regional administration was trying to convince the Humboldt supervisor of the utility of a grazing advisory board. [78] Because of domination by one permittee, Toiyabe Supervisor Vernon Metcalf found considerable difficulty in working with the forest's grazing associations until the forest was divided in two in 1915. [79]

Some observers thought that the advantages Fenn saw in the associations were, in fact, liabilities that undermined the social purposes of the Forest Service's program. Wyoming Congressman Frank Mondell claimed that because the Service tied the interests of members of the grazing associations to the forest, those who were rich and powerful were able to get permits while small operators with little influence could not, as the demand for space far exceeded the supply. [80]

Although the boards helped the supervisors, they also created more work for them since the forest office had to enforce the association's rules. On the Caribou and Uinta, for instance, the supervisors took action to deny permits to graziers who failed to pay their association fees or who refused to go along with association rulings on such matters as distribution of bulls. [81]

At times, the supervisors found large permittees who did, indeed, try to circumvent the social purposes of the Service. In the early 1920's, Senator Robert N. Stanfield of Oregon controlled permits for about 19,500 head of sheep on the Weiser and Idaho National Forests through hidden ownership in various sheep companies. Lyle F. Watts tried unsuccessfully to get sufficient evidence for a cancellation. After William B. Rice became supervisor, however, Stanfield's disgruntled former partner Mac Hand brought the evidence that led to the cancellation. Stanfield appealed Regional Forester Rutledge's decision upholding Rice, but the Secretary of Agriculture sustained the region's decision. [82]

Extent of Range Deterioration

Even though western Idaho was generally perceived as in better shape than Utah, range problems existed on many national forests there as well. In 1912, Idaho National Forest Supervisor Herbert Graff wrote that "when we have such a vast acreage of overgrazed territory on which even the grass roots are no longer in evidence, we cannot begin to make an estimate of the damage to reproduction." [83] In 1916, Graff said the forest consisted of readily accessible lands that were badly overgrazed and inaccessible back country into which no one wanted. By 1924, Watts had made "more progress . . . on the grazing job . . . than ever before," but "the range in the back country is for the most part a poor range." [84]

In part, the inattention to grazing problems on western Idaho forests like the Idaho and the Weiser resulted from the lower priority placed on grazing than on other functions. Ernest Winkler wrote after an inspection in 1919 that the "grazing business" was of such a nature "it can be put off until other pressing activities [such as repairs, timber sales, and fire suppression] had been attended to." [85]

In contrast with other forests in Region 4, the Salmon ranges at this time were in generally good shape, largely because of lack of demand. There, as late as 1916, managers could get away with somewhat more lax enforcement of salting and other regulations and with failure to implement recommendations based on reconnaissance. [86]

The Manti lay at the other end of the spectrum. Stockmen resisted every attempt to reduce numbers, and particularly fierce battles in 1917 and 1919 led to an appeal to the Secretary of Agriculture, who sustained Supervisor J.W. Humphrey's reductions. [87] Humphrey and his staff continued to work on the situation. Though they lost some battles, they drafted working plans based on extensive range reconnaissance and had improved some of the worst ranges by 1926 when C.E. Rachford conducted an inspection. [88] Still, conditions were bad enough that at some of the ranger meetings "the Manti was used as a horrible example so often" that it was finally agreed to fine anyone who mentioned it! [89]

Permittee Control of the Range

Because of intense pressure for permits on scarce grazing lands range managers in Nevada had more political problems than those in Idaho or Utah. In the Silver State, the demand for reductions led to counter-pressure from stockmen for control or ownership of the grazing lands. The leadership of the movement rested in the Nevada Land and Livestock Association whose executive secretary, Vernon Metcalf, had served as supervisor of the Toiyabe National Forest and chief of the division of operations for Region 4. [90] Meetings of stockmen at Tonopah, Reno, Winnemucca, and Salt Lake City in 1925 and 1926 called for the recognition of grazing on public lands as property right based on "priority and preference." [91]

The pressure for control over grazing permits also led to proposals for legislation to give stockmen more power. In late 1925, the Senate Public Lands and Surveys committee held hearings throughout the West on several bills, one of which was sponsored by Senator Stanfield and Senator Tasker L. Oddie of Nevada. Though it did not pass, the Stanfield-Oddie bill would have made the grazing advisory boards the final authority in disputes between the stockmen and the Forest Service. [92] In 1928, Oddie cosponsored with Senator Key Pittman a bill that would have redesignated the three Nevada forests as grazing reserves under the Interior Department, thus removing the ranges and stockmen from Forest Service jurisdiction. In their view, this change would have solved the problem of permit reductions and local control. [93]

Permits and Fees

In view of the pressure for autonomy and the depressed economic conditions in agriculture during the 1920's, the Service proposed a number of measures to provide stability. In 1923, it announced the awarding of 10-year permits, which were given the status of contracts in 1926. In addition, the Service permitted stockmen to pay fees in two installments instead of a month before the animals went on the range. It also set an exemption limit below which permittees would not be required to make reductions in favor of new applicants, so that stockmen would not be forced to reduce their herds to numbers below which they could expect to "maintain a reasonably profitable enterprise." [94]

From the beginning of Forest Service administration, the question of what fees ought to be charged for the use of the grazing privilege had faced the Forest Service and forest users. Three contradictory tendencies appeared over time. At first the Service wanted to subsidize small stockmen. Then, as budget deficits mounted, Pinchot and Graves promised that the Service would pay its own way from receipts from resource uses. Some congressmen applied pressure to raise grazing fees to the market level of private grazing lands. [95] Stock interests, on the other hand, argued that the Forest Service ought to keep fees stable or even reduce them to the cost of administration. [96] Annual fees in 1910 ranged from $0.35 to $0.60 for cattle and $0.10 to $0.18 per head for sheep. In 1915-16 and 1917-19, rates were raised somewhat. Thereafter, they remained essentially stable until the early 1920's. [97] By 1919, receipts from grazing exceeded the amount earned from timber for the Forest Service as a whole. [98]

The issue of grazing fees plagued Region 4 as well as the Service in general. In 1911, Supervisor Orrin Snow argued that grazing ought to be put on a competitive-bid basis instead of a preference basis. Supervisor C.S. Tremewan of the Humboldt believed that if the Forest Service offered rangeland on a competitive basis like timber it would create monopolies. Clinton G. Smith of the Cache said that a purely competitive system would tend to create instability, since the rancher would have to bid each time his permit ran out and if he did not get one, he would be forced to sell his livestock. [99] In 1913, Woods, then Sawtooth supervisor, argued unsuccessfully that because ranchers received high prices for livestock, the States took 35 percent of the gross forest receipts, and the forests were being pressured to be self-supporting, annual grazing fees for sheep ought to be increased to 25 cents per head. [100]

Regional Forester Sherman said that under current social policy, the Service was "selling five dollar gold pieces for one dollar and a quarter," and operating a different "machine" to help small stockmen. "Under the competitive system, the difference between the $1.25 and the $5 gold pieces, or $3.75 goes into the Treasury. Under the present system it goes into the hands of the permittees. The problem the Service had to solve was "what way can we best distribute these five dollar gold pieces in order to get the best results for the country?" The Service's answer was "to support the greatest number of homes." The Service chose to provide "cheap feed" to the small operator where the grazing privilege made "the difference between failure and success." [101] Supervisors Snow and William M. Anderson presented a resolution to the 1911 supervisors' meeting favoring a market system, but the majority voted to reject it. [102]

A major problem in determining the rate at which fees ought to be set was the absence of an appraisal of the comparative value of forest ranges and private range-lands. In an attempt to correct that problem, in 1921 Chief Greeley assigned C.E. Rachford of the Washington Office's grazing division to conduct a market-based appraisal. [103]

By the time Rachford completed his report in 1924, considerable opposition to increased fees had grown among stockmen and their congressional supporters. Opponents questioned the market assumptions upon which Rachford had done his work. The public lands, they argued, had become integral units of established ranching operations before the forests were created, and increases in grazing fees served only to upset the existing balance. Thus, the ranchers denied that forest grazing lands ought to be treated like property they might lease or purchase. [104]

The stockmen's negative response to the Rachford report led to the Agriculture Department's appointment in January 1926 of Dan D. Casement, a Kansas stockman, to review the report. Casement's review, submitted in June 1926, accepted Rachford's criteria, although it raised some questions about the method. In general, Casement found Rachford's work as it applied to the Intermountain Region to have been fairly, accurately, and exhaustively completed. The private land Rachford had selected for comparison was generally representative—in fact, the values were on the conservative side. Casement faulted Rachford's report only for its failure to consider and quantify the restrictions placed on permittees, in the public interest, that the would not have faced in the rental of private lands. [105]

Upon completion of the Casement review, the regional office prepared a summary, together with its own recommendations, which it passed on to the forest supervisors. The summary provided a tabulation of the current fees, the Rachford recommendations, the Casement revisions, and the proposed fees. In 1927, the average monthly fees stood at 10 cents a head for cattle and 2.8 cents for sheep. Rachford recommended an average of 17.5 cents for cattle and 4.7 cents for sheep; Casement revised the figures to 16 cents for cattle and 4.2 cents for sheep. These proposals were scaled down somewhat in negotiations between the Agriculture Department and the livestock associations. The final regional recommendation was 15.6 cents for cattle and 4 cents for sheep. [106] This amounted to a 56-percent increase over the old rates for cattle and a 43-percent increase for sheep. The Secretary of Agriculture agreed to phase them in by 25-per cent increments over 4 years beginning in 1928. [107]

One important feature of Forest Service decentralization that facilitated grazing administration by 1911 was a reform in the appeals procedure. The new regulations made it necessary for the appellant to present his entire case to the supervisors. No new evidence could be introduced later before the regional forester or the secretary. This strengthened the hand of the supervisor, because the only basis for an appeal became the allegation that the supervisor's decision had not been in accordance with the regulations. [108]

Grazing and Land Protection

Initially, foresters believed sheep generally injured tree growth. [109] Bryant S. Martineau reported on studies on the Old Payette between 1912 and 1914 that ought to have laid the attitude to rest. In conducting these investigations, methods of bedding out pioneered by Arthur Sampson on the Wallowa in Oregon were utilized. Instead of bringing the sheep back to a central camp each evening, the animals were allowed to bed down wherever they happened to be grazing. Moreover, dogs were used only to protect the flocks against predators and not to force the stock over the same ground. Martineau found that with this method "these areas may be fully stocked, provided they are properly handled, without injury to the reproduction of yellow pine or other conifers," [110] Old habits died hard, and as Jack Albano found on the Targhee, getting herders to adopt the bedding out system was difficult. [111] By 1926, however, 93 percent of all herders in Region 4 (the highest percentage in the Service) used the bedding out system. [112]

|

| Figure 35—weighing lamb at end of grazing season, experimental band, Deadwood Basin, Old Payette National Forest, 1913. |

Many familiar with the livestock industry argued that inadequate herd supervision and the grazing habits of cattle made them a potentially more serious threat than sheep. C.N. Woods pointed out that in spite of sufficient feed on the allotments, cattle tended to "remain too much on the lower, less steep country and along the water and among the willows." The remedy, as he pointed out, was driving and holding cattle "in rougher country and in putting salt higher in the mountains." Sheep, he indicated, "graze the range more evenly than either cattle or horses." [113]

In practice this meant that some areas of a cattle allotment could be badly overgrazed while others in the same allotment were hardly used at all. An inspection on the Diamond Fork in the Uinta National Forest in 1927, for instance, showed some areas as much as 90 per cent utilized and other portions "lightly grazed," largely because of inadequate herding by the permittees. [114] In the early 1920's, Charles DeMoisy secured some reductions on the La Sal for range improvement because cattle tended to congregate on the "high yellow pine ranges, " instead of grazing the allotments evenly. [115]

In general, supervisors indicated that getting cattlemen to cooperate in promoting uniform allotment use through salting was more difficult in Utah and Nevada than Idaho, The problem was, however, almost universal since stockmen "didn't want to take the fat off of them walking after salt." [116] Supervisor J.M. Ryan cited "poor distribution of salt and lack of handling" as the reason for overgrazing on some cattle ranges on the Ruby. Nevertheless, Ryan tended to favor cattle over sheep because of "the sentiment of the majority of the people." [117] Vernon Metcalf on the Toiyabe pointed to the difficulty in getting cattlemen to salt properly as a reason for overgrazing. [118]

A result of the overgrazing was the destruction of favored and most palatable species and the succession of less palatable and often poisonous plants. The problem with plant poisonings in Region 4 was among the worst in the National Forest System. A 1916 report indicated that 42 percent of all sheep and 25 percent of all cattle poisonings on forest lands took place in Region 4. [119] By 1926, the region retained its proportionately high place. [120] A major problem in determining the cause of livestock losses was the general habit of turning cattle onto the range and allowing them to forage unattended. [121] Even the Salmon with its relatively sparse livestock load reported problems with larkspur and death camas. [122] In his 1911 report, Guy Mains on the Old Payette pointed out that most losses came about in areas "closely fed and overgrazed." He said that "the best remedy seems to be to give an allotment large enough [for the number of livestock] to make close grazing unnecessary." [123] On the Lemhi and some other forests, employees reduced the incidence of larkspur by digging. [124] On the Humboldt, herders moved sheep into areas with larkspur to eat it down, since the plant was poisonous to cattle but not to sheep. [125] On some forests, such as the Toiyabe, poisonous plants were not perceived to be a particularly great problem. [126]

Quarantine Regulations

Throughout the period, the Service worked with the States and the Bureau of Animal Industry (BAI) in enforcing quarantine regulations on the forests. In 1912, for instance, because of an outbreak of lip and leg ulcerations, forest officers inspected animals on the Cache, Caribou, and Pocatello in Idaho and all forests in Nevada and Utah except the Ashley. [127] Where scab appeared, the Forest Service required herders to dip their sheep in a sulphur and lime solution. [128] The Chief Forester, however, would not approve requests such as the one made by Supervisor F.J. Ryder of the Palisade to control distemper or J.B. Lafferty's on the Weiser to require vaccination for blackleg, because there were no pertinent BAI or State regulations. [129]

Range Rehabilitation

Some forests tried experiments with range reseeding. On the Targhee in 1910, the experiment was "a total failure," owing to the "drouth of that season." [130] In 1912, after this and other such failures, Regional Forester Sherman told forest supervisors who requested permission to reseed ranges to wait until the Great Basin station completed experiments to determine "the plants that are most likely to succeed in soil and climatic conditions common to the Utah Mountain ranges." [131] His successor Kneipp and other forest officers, as well, believed that "range improvement by reseeding must be done largely by natural methods," particularly through careful management by bedding out and by deferred and rotation grazing. [132] On that basis, he rejected an initiative of the Mill Creek Grazing Association on the Wasatch to reseed its range. [133]

Stocking Trends and World War I

In the period between 1910 and the American entry into World War I in 1917, two trends in stocking were evident. [134] First, there was an increase of 59 percent from 376,000 to 597,000 in the number of cattle and horses. At the same time, there was an increase in sheep from 3.9 million in 1910 to 4.4 million in 1912 followed by a decrease to 3.5 million in 1917, for a net 10-percent decrease. In 1918, the number of cattle and horses, 620,000, reached its highest point since the Forest Service began administering the lands. The number of sheep increased to about the 1913 level. [135]

The net effect of these changes for cattle, horses, and sheep was to increase stocking dramatically. If one uses the forage acre estimates accepted at the time, with 0.8 forage acre per month for a cow and 0.3 for a sheep (a ratio of 2.6 to 1), animal units had actually increased from about 1,895,082 to 2,181,469 between 1910 and 1918, or about 15 percent, largely because of the increase in cattle. [136]

When he dictated his memoirs in 1964-65, Leon Kneipp believed that Region 4 had resisted the pressure to increase meat and wool production during the war. [137] If one were to measure only sheep, that would be true. The increase in cattle, however, more than offset the decrease in sheep and exacerbated an already serious situation.

At the time, Kneipp knew that overgrazing had been permitted. In 1919, he wrote to Supervisor Lafferty that "economic conditions and the labor situation incident to the war have led us during the past couple of years to tolerate conditions which obviously are not in accord with the purpose for which a particular forest was created, and the result has been in many instances detrimental to the interests of the Service and the purposes for which it stands." Such exceptional conditions had disappeared by 1919, and Kneipp urged the "vigorous application of proper principles of Forest administration, including grazing management, to enable us to regain lost ground and to make the progress in the improvement of the Forest lands which may reasonably be expected as a result of our expenditures of funds and effort." [138]

Clearly, in fact, the wartime pressure for increased stocking had come from both the regional administration and the Washington Office. Ernest Winkler for instance, recommended an increase on the Targhee. [139] The situation was undoubtedly the worst in Utah. In his annual report for 1917, William M. Anderson of the Ashley estimated a grazing capacity on the forest of 96,000 sheep and 10,300 cattle and horses. [140] The Secretary of Agriculture, however, approved 106,000 sheep and 11,400 cattle for 1918 as "a purely temporary emergency measure" to "be discontinued at the close of the war" or before that "if it becomes evident that the grazing of the additional number of stock may result in permanent injury to the Forest and range." [141]

In an apparent attempt to justify the action, Anderson reported that, except in a couple of unusual cases, he did not believe that the increased stocking had hurt the range. [142] With somewhat more detachment, Rachford, who conducted range appraisals in 1921, found the situation in Idaho better than in Nevada, where the range was improving, and worst in Utah, where land deterioration had become critical. [143]

Moreover, the wartime emergency necessitated the curtailing of range reconnaissance. Crews worked only on the Uinta in 1917 and the Salmon in 1918. The regional office had planned to complete work already begun on the Sevier and to initiate work on the Fillmore and Fishlake, but had to suspend all three projects. [144]

Postwar Grazing and Reconnaissance

During the war, increased stocking seemed patriotic. [145] Afterward, concern for the condition of grazing lands began to weigh more heavily. In 1920, the permitted number of sheep was lower than any year since 1906, when the number of forests and extent of acreage in the Intermountain Region were far lower. By 1921, even the level of cattle stocking was down to approximately that of 1916, and it continued to decline during the decade. [146]

After the war, the Service reinaugurated studies to determine proper stocking. First, it undertook reconnaissance on a number of forests where it had not been done before World War I. Second, on those where studies had been made, followup investigations on the quadrats and enclosures were undertaken; and, in some cases, new quadrats were established. Third, period studies were inaugurated to determine the proper time for stock to be allowed on and removed from the range. Fourth, additional palatability research was undertaken to determine what sorts of grass, forbs, and browse different classes of animals preferred. In some cases, as on the Uinta after 1925, these phases were combined in a single study. [147] Finally, these studies were followed with management plans in which forest officers tried to incorporate the research data.

Region 4 led the Forest Service in reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies during the 1920's. [148] In 1919, sample reconnaissance was undertaken on the Humboldt. [149] In 1922 reconnaissance was undertaken on the Fillmore and Minidoka and on a new addition to the Caribou. [150] In succeeding years, similar studies were undertaken on a number of other forests in the region including the Idaho, Payette, Weiser, Boise, Cache, and Wasatch. [151] By 1926, 41 percent of all Forest Service quadrats and more than half of all check enclosures were located on Region 4 ranges.

In retrospect, it is clear that in addition to excessive livestock numbers, a major part of the problem with overgrazing came because of the excessively early date when livestock were permitted to enter the allotments. After a 1915 inspection of the Santa Rosa, Woods and Kneipp both thought that a major reason for the overgrazing on the forest was that cattle were allowed to enter as early as April 15, "when the grass has barely started." Kneipp suggested that Supervisor W.W. Blakeslee consider delaying until May 1, which would be "more in keeping with natural conditions" on the forest. [152]

Something more than the range reconnaissance and carrying capacity studies was needed to provide information on when range plants were ready for grazing, since even though working plans were written on the basis of these studies, supervisors allowed animals on allotments before plants had begun to mature. [153] Following a drought in 1919, some of the cattle associations agreed to change the opening date on the Caribou to May 5 because of overgrazing in particular areas. By that time, Supervisor Earl C. Sanford had recognized the need for additional tests to "arrive at proper grazing seasons and generally to secure a proper adjustment of the grazing on these allotments." [154]

Period studies were begun in 1919 on the Uinta, on the Caribou in 1921, and the La Sal in 1922. [155] On the Caribou, after a survey of 4 allotments consisting of 12 cattle units, on which the current season began between April 20 and May 1, H.E. Malmsten recommended deferring the opening of grazing by 10 to 15 days during an average year. After a particularly severe winter, 1920-21, for example, snow still covered some north slopes and vegetation was not ready for grazing until May 20. In line with general Service policy, Ernest Winkler, Woods's assistant in the regional office, recommended that Sanford phase in the new dates over a period of time to minimize economic dislocations. [156]

Some supervisors had to work in the absence of a full reconnaissance of the forest. A partial reconnaissance of three allotments of the Humboldt in 1919 indicated that a reduction of at least 25 percent of both sheep and cattle numbers would have to be made in 1920 in addition to a cut of 25 percent that Favre had instituted in 1919. [157]

Since no full-scale studies had been undertaken on the Humboldt, Supervisor Favre had to work through trial and error. No other supervisor in Region 4 was as well suited to do that; Favre had been intimately connected with the Caribou reconnaissance. During the early 1920's, Favre began the annual closing of 40,000 to 50,000 acres of grazing land on the Santa Rosa division to allow reproduction of grazing lands and aspen. Will Barnes, Chief of Grazing in the Washington Office, questioned the practice, indicating that their studies had shown that "the same results in range revegetation can be accomplished by deferred grazing together with proper stocking and adequate distribution." Favre was already practicing deferred grazing, reducing number of stock, and insisting on adherence to working plans, and as the range continued to deteriorate, the closures were allowed. [158]

Unfortunately, the various studies and the new management plans did not solve the problems. Management plans completed on the basis of a reconnaissance (1923-27) on the Weiser had continued to result in some overgrazing. They proved unworkable, in part, because some of the range counted in the estimates had not been grazed and plant species differed in western Idaho from those on the Caribou where the forage-acre estimates had been formulated. A.R. Standing, who investigated the situation at the request of Supervisor John Raphael, believed the only solution was closer cooperation between the reconnaissance crew and the forest personnel along with adequate palatability tables and carrying capacity studies for each forest. [159]

On the Fishlake, a similar situation was apparent. Supervisor Ianmer Christensen and his rangers had used the studies to make range management plans and adjustments, in the face of considerable user resistance. [160] In the summer of 1927, Ernest Winkler and a large party inspected the range. While some improvement was evident, and "grass and other vegetation" now covered some "areas once almost bare," lack of satisfactory improvement on some ranges led Standing to comment that "grazing surveys cannot be criticized for estimating less stock on this range, for under present use and management, it is still being overgrazed." [161]

|

| Figure 36—Forest supervisors' meeting at Great Basin Experiment Station, July 1926, Manti-LaSal National Forest. |

In 1928, James O. Stewart, grazing inspector from the regional office, returned to the original Caribou quadrats and mapped those which had not been obliterated. The results were somewhat mixed, since a great many had been destroyed. On 12 sample plots Stewart found grasses had decreased on 8, increased on 2, and changed little on 2. Less palatable species had tended to increase. [162]

These and other examples of lack of improvement led range managers to question the standard forage-acre estimates. As early as 1921, in replying to Sanford's report, D.A. Shoemaker of the regional office wondered whether the estimates were representative, suggesting that the forage-acre standard for cattle might have been biased because cattle drifted onto sheep allotments and private land. [163]

By the late 1920's, the regional officers tended to reject the standard forage acre. In 1927 at a meeting of the Society of American Foresters, Charles DeMoisy argued that problems had resulted from the application of standard monthly forage-acre figures (0.8 and 0.3) to fallacious palatability estimates. He said further that only through intensive study of individual ranges could examiners determine the proper stocking. [164] In a report of 1927, Dean Phinney said that "the old forage acre estimates continue to be high. Palatability percentages used on the old reconnaissance are in the main responsible for the high forage acre figures." [165]

Moreover, more recent research in certain areas has shown other standards to have been faulty, something that range managers in the 1920's could not have known. Forest officers based forage volume estimates during the 1920's on the assumption that animals could eat 75 to 85 percent of the vegetation without damaging its reproduction. More recent studies have shown that there "should have been closer to 50 percent forage left at the end of the grazing season." [166] In carrying capacity weight gain estimates, lamb weights of 65 to 70 pounds were considered acceptable in the 1920's, whereas by the late 1960's, weights of more than 90 pounds were not unusual. Even the 70-pound animals were a considerable improvement on the 40-pound lambs produced on the Humboldt in 1909. [167]

What these figures seem to reveal is that even conscientious managers who stocked their ranges somewhat conservatively, on the basis of the research-produced and generally accepted standards, could cause over grazing. [168] This is not to disparage the value of research, since the questions raised about the previous forage-acre estimates came through additional research. It does, however, indicate that managers could have done well to have asked some hard questions about the considerable difference—as much as 89 percent—between the forage requirement estimates for cattle based on range reconnaissance and the higher estimates based on experience. [169]

Not surprisingly, reports from the forests indicate that supervisor's rule-of-thumb carrying capacity estimates generally followed quite closely the ideological trends and economic pressure. On the Boise, for instance, one notes an upward swing in carrying capacity estimates for both cattle and sheep during World War I, then a considerable decline in the late 1920's as the forests came under pressure to improve ranges. [170]

Some change there may have come about as the result of the appointment of Guy Mains as supervisor. Looking at the forest with a fresh eye in 1926, Mains said that he was "forced to the conclusion that past estimates of carrying capacity of the Boise will have to be revised before we can formulate a grazing management plan." [171] His predecessor, E.C. Shepard, had come from the Cache, and the Boise ranges must have looked good to someone from an overgrazed Utah forest. Mains, however, came from the Old Payette, which was then in relatively good shape.

In some cases, managers allowed prevailing economic conditions to bias the results of some of the "scientific" studies. In the case of the Minidoka, for instance, Grazing Assistant Milo H. Deming admitted that a potential economic dislocation "largely influenced" a number of his period study recommendations for excessively early grazing. In his view, stockmen had no place to put their cattle once spring work on the farms began, so he revised his results to allow them on the forest. He apparently did not consider using homegrown or purchased hay or more rigorous commensurability standards acceptable alternatives. [172] Similar grounds were given in period study reports on the Ashley. [173] Moreover, Forest Service policy dictated that reductions made on the basis of such research were to proceed gradually, so permittees "may adjust their business to meet the changes." [174]

In view of the depressed economic conditions in the livestock industry of the 1920's, such concern is quite understandable. Unfortunately, this approach did not help improve the condition of the ranges. [175]

This is not to say that some improvement did not take place. Reductions came about as a result both of reconnaissance figures, period studies, and horse sense. [176] On the Caribou, for instance, the number of cattle and horses approved declined from 22,900 in 1921 to 18,000 in 1929 and the number of sheep from 265,000 to 235,000. [177] The reductions in numbers were accompanied by reductions in the length of the season. By 1927, the longest grazing season on the lower country along the Snake River on the Caribou was from May 1 to October 31. Most seasons began on May 16 or 20, and one started as late as June 1. In 1929, the starting date for the Snake River allotment was set back to May 15. Similar changes were noted on the Wasatch, the Ashley, the Old Payette, and the Targhee. [178] As might be expected, the reductions in numbers of stock and length of seasons came about in the face of considerable "opposition and vigorous criticism." [179]

The Development of Forest Service Research

Implementation of research results contributed heavily to the success the Forest Service experienced in range management. [180] In providing research findings, Forest Service experiment stations served as the backbone of the research effort. The goal of these stations was to establish a scientific basis for management policy. [181] Even though the Great Basin Experiment Station was not the first station established, by 1913 the Service had made the conscious decision to center its intensive experiments in range management there. [182] Established in 1912 in Ephraim Canyon on the Manti National Forest, the station was first named the Utah Experiment Station. [183]

After the Forest Service had carried on research for more than two decades without specific statutory authority, Congress recognized the situation in the McSweeney-McNary Act of 1928 by authorizing the creation of experiment stations. On July 1, 1930, the Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station was established as an umbrella entity for all research and the Great Basin Station became a branch of the larger organization. [184]

The Great Basin Station was extremely fortunate for a number of reasons. Arthur W. Sampson became its first director. Already noted for his range and forest research, he brought recognized competence to the station. He and his successors drew in a number of bright and creative scientists who laid the groundwork for an understanding of the management of western grazing lands. Sampson himself and Frederick S. Baker of the station were later recruited by the University of California faculty. There, Sampson authored the standard texts on range management, which he based on research done under the auspices of the Great Basin Station. W.R. Chapline, who started his career as a student researcher at the station, ultimately became Chief of Range Research for the Forest Service. Clarence L. Forsling, who succeeded Sampson as director in 1922, eventually became head of the Forest Service Division of Forest Research and later Director of the Grazing Service in the Department of the Interior. [185]

Most important by 1929 were the watershed and range management studies. Sampson began his first research on two watersheds of 11 and 9 acres called A and B at the Great Basin Station. By manipulating the extent of grazing on them, the researchers demonstrated they could control water and sedimentary runoff, and they established beyond any reasonable doubt that proper management of vegetative cover could protect the land from excessive erosion. Other aspects of these studies included artificial revegetation; range readiness (when animals should be allowed on the range); plant vigor studies (how long and extensively the range could be grazed); methods to eradicate poisonous plants; the relation of grazing to aspen reproduction; the relationship between weather and plant development; and, perhaps least important at the station, revegetation with ponderosa pine. [186]

Significantly, the range and watershed studies had immediate application to range management in Region 4. The system of sample plots and quadrats that Sampson developed at the station beginning in 1913 became the basis for the range reconnaissance system introduced on the Caribou and elsewhere. [187] The range readiness and plant vigor studies provided the techniques for the period studies and the management plans designed to keep the animals from going on the range too early or staying too long. [188] The research on eradication of poisonous plants provided the rationale for grubbing and grazing the plants. Sampson's work in Utah and Oregon provided the justification for deferred and rotation grazing. [189] Because of the lack of success in revegetation studies, for many years artificial revegetation was largely curtailed in Region 4. [190] Research showed, however, that forest officers could achieve good results using hardy native species grown under conditions similar to those in the area to be seeded. [191] Research also showed that recovery of valuable vegetation was an extremely slow process. [192] Studies reported in 1920 showed that the removal of vegetation more than once or twice per year was detrimental to the plant community. [193]

Closely associated with the Great Basin Station was the work of the field station for research on poisonous plants at the Salina Experiment Station on the Fishlake National Forest. Set up in cooperation with the Bureau of Animal Industry, the station under C.D. Morse conducted research on toxicity of plants and on methods of larkspur eradication. [194] On the basis of this research, demonstration eradication projects were undertaken on the Fishlake, Sevier, Palisade, Minidoka, Lemhi, Targhee, Dixie, Kaibab, La Sal, and Weiser in 1917. [195]

Other research in Region 4 included studies on the Dixie of feeding sheep from browse as a substitute for grazing on grass and weeds. [196] The studies showed that the extent of feeding necessary to utilize the browse was detrimental to the total community of vegetation and resulted in increased erosion. [197]

Beginning in 1929, the Great Basin Station worked in cooperation with the Bureau of Animal Industry's Sheep Experiment Station at Dubois, ID. Tests there supplemented the range readiness research. [198]

Every effort was made to see that research addressed the Forest Service's management needs. In 1912, Chief Henry S. Graves set up a central investigating committee in the Washington Office with three divisions: silviculture, grazing, and products. Each district established similar committees. The original committee for Region 4 consisted of O.M. Butler, assistant regional forester for silviculture, Homer E. Fenn, assistant regional forester for grazing, and Clinton G. Smith, Cache forest supervisor. [199]

Although in June 1915 Graves nominally separated research from both the national and district administration, he expected to place field research under the regional foresters. [200] In fact, research in Region 4 was closely tied to administration. The regional investigative committee consisting of representatives of the regional administration, the Great Basin Experiment Station, forest supervisors, and, by 1926, representatives of Utah State Agricultural College (now Utah State University) planned the agenda of research. This committee sought to ensure that those studies most needed in the region would receive the highest priority. [201]

Moreover, the Agriculture Department intentionally linked research with the practical needs of the forest users. In the 1920's, Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace and his successor William M. Jardine secured the appointment of research advisory committees in the various regions to maintain a close relationship between the public and the Forest Service and to prevent duplication of work and waste of time on problems of no particular urgency. The committees consisted of 20 men representing the interests of the region such as lumbering, banking, grazing, and manufacturing. [202]

The regional administration consciously tried to implement research findings on the ranger district level. Various forest officers were brought to the Great Basin Station, the Fishlake poison plant project, and other research points to study the conditions. [203] The staff of the station reviewed some allotment management plans during the 1920's to see whether they met the standards set by research findings. [204]

Although much had been accomplished between 1910 and 1929, forest officers had to accomplish a great deal more before the ranges could be said to be in optimum condition. The problems remained essentially fourfold. First, the managers had to find and use techniques to measure range condition, trends, and extent of deterioration much more precisely than before. Second, in view of the resistance of stockmen to reductions in grazing, they had to continue to develop public relations skills to deal with range users and political allies and sidetrack the movement for user control of Federal grazing lands. Third, they had to develop management plans and techniques that they could realistically implement in the face of practical range conditions and user resistance. Fourth, they had to develop the skills necessary to implement needed range improvements at the cost of some economic dislocation. On their ability to accomplish these four tasks rested the future of the forest grazing lands in Region 4.

Reference Notes

1. Ernest Winkler to Forest Officer, November 25, 1927, Targhee National Forest Records, RG 95, Seattle FRC.

2. The Washington Office authorized this through a memorandum of April 17, 1917, copy personal papers of William D. Hurst, Bosque Farms, New Mexico.

3. See: District 4, "Minutes of Supervisor's Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests, Boise, Idaho, January 2-4, 1910 [actually 1911]" (n.p., 1911); and District 4, "Minutes of Supervisors" Meeting Utah and Nevada Forests, Ogden, Utah, January 23-25, 1911" (n.p., 1911), copies, Historical files, Boise.

4. "Minutes of Supervisor's Meeting, Idaho and Wyoming Forests," 1911, pp. 30-45. The vote was recorded on p. 45.

5. George G. Bentz to District Forester, June 10, 1911, and E.A. Sherman to Forest Supervisor, June 14, 1911, File: G-Management, Allowances, 1907-1916, Caribou National Forest Records, RG 95, Seattle, FRC.

6. Grazing Chapter Annual Forest Plan, Caribou National Forest, 1911, File: G-Management, Allowances, 1907-1916, Box 32115, Caribou National Forest Records, RG 95, Seattle, FRC. On the Sawtooth National Forest in 1911 it was usual to require a 20-percent transfer reduction. Ray Ivie, "Grazing on the Sawtooth National Forest and Some Forage Plants Thereon," File: O-Supervision, General, Historical Files, Sawtooth.

7. Grazing Chapter—Supervisor's Annual Working Plan, 1915, Caribou National Forest, November 5, 1915, File: G- Management, Allowances, 1907-1916, Box 32115, RG 95, Caribou National Forest Records, Seattle FRC. L.F. Kneipp to Forest Supervisor, April 5, 1915, ibid.

8. Forest Service Report in Agriculture Department Report, 1910, p. 402; 1911, p. 397; 1913, p. 185.

9. A.C. McCain to S.B. Arthur, February 12, 1915, File: G- Plans, Humboldt, General, 1912-1919, Grazing Records, Humboldt.

10. I am particularly indebted to Mont E. Lewis and Irwin H. "Hap" Johnson for information on systems of range investigation. See: Arnold R. Standing, Memorandum on Work in the Forest Service, January 4, 1962, Historical Files, Fish lake. In the case of a Minidoka survey in the early 1920's, the field party ran into considerable difficulty because they had no Division of Engineering Control points or available section corners. In addition, two different General Land Office surveys did not coincide. Milo H. Deming, "Minidoka Grazing Reconnaissance," 1923, File: G- Management Inventory, Sawtooth (Minidoka), 1922-23, Grazing Records, Sawtooth. U.S. Department of Agriculture—Forest Service, "Grazing Reconnaissance Section Plat, Form 765, Revised December 28, 1911 [and February 1913]," MS, Files of Mont E. Lewis, Regional Office. Albert F. Potter, ed., "Grazing Reconnaissance," MS, 1913, Historical Files, Regional Office. For a discussion of the method see Arthur W. Sampson, Range and Pasture Management (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1923), pp. 307-26. E.C. Sanford, "Caribou Grazing Reconnaissance Report For Field Season of 1915," MS, Caribou, 1916, File: CS- Studies, Reconnaissance, Caribou, 1916-1917, Caribou.

11. Sampson, Range and Pasture Management, p. 330; for a discussion of carrying capacity see pp. 328-33.

12. Homer E. Fenn to George G. Bentz, February 10, 1915, File: C- Studies, Carrying Capacity, 1914 and 1915, Historical Files, Caribou.

13. Mark Anderson, "Carrying Capacity Tests for Caribou National Forest, 1914," MS, 1914, File: C- Studies, Carrying Capacity, 1915 and 1914, Caribou; and "Carrying Capacity Working Plan," MS, 1915, ibid. Though Anderson's report might lead one to believe that the weight gain measurements were sufficient, his work on the Sawtooth the next year which included the establishment of sample plots indicates his recognition of the need to use other measures of trend to determine carrying capacity. Mark Anderson, "Report on Sawtooth Carrying Capacity Test, 1914," File: G- Studies, Carrying Capacity, Sawtooth, 1914, Grazing Records, Sawtooth. On the practical side, the forest supervisor coupled this examination with information on monthly changes in lamb prices in order to determine the relative economic advantage of leaving the sheep on the range or selling them early because of declining rate of weight gain later in the season. George G. Bentz to A.J. Knowllin, October 16, 1915, ibid.

14. For a description of the method see Sampson, Range and Pasture Management, pp. 339-55.

15. Clarence E. Favre, Memorandum for Grazing, August 3, 1916, File: Grazing History, Range History Files, Caribou. W. Vincent Evans, "Progress Report, Caribou Carrying Capacity, 1916," MS, 1916, p. 56, File: C- Studies, Carrying Capacity, 1916, Caribou. See the entire report for a discussion of the method and application and pp. 56-62 for a discussion of the enclosures.

16. C.H. Shattuck, "Value of Grazing Management on the Caribou National Forest," American Forester 23 (1917): 536-38.

17. Sterling R. Justice, The Forest Ranger on Horseback, (n.p. 1967), p. 82.

18. Sampson, Range and Pasture Management, p. 325.

19. Albert F. Potter to District Forester, February 18, 1916, File: G- Studies, Carrying Capacity, 1916, Caribou.

20. James T. Jardine and Mark Anderson, Range Management on the National Forests, USDA Bulletin No, 790 (Washington: GPO, 1919), pp. 27-29.