|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 6

Forest Management in a Depression Era: 1930 to 1941

In October 1929, the United States began to sink into the worst economic disaster in its history. National unemployment reached more than 25 percent of the labor force by the winter of 1932-33. Wages and property values dropped, and poverty became a way of life for numerous Americans. In general, the States of the Intermountain Region were harder hit by the depression than was the Nation as a whole. In Utah, for instance, nearly 36 percent of the labor force was unemployed in 1932. [1]

The impact of the depression on the Forest Service in Region 4 was essentially twofold. In the first place, because of the decline in markets, receipts from timber sales and grazing permits declined significantly. Second, because of additional public works funds, particularly those given to the Civilian Conservation Corps, and to a lesser extent to the Works Progress Administration and the Public Works Administration, the recreational and administrative facilities of the region were substantially improved. As early as 1932, Congress appropriated additional funds for forest highways and trails to assist the unemployed. [2]

Farm Resettlement

The situation was extremely serious, and as farming became increasingly unprofitable on marginal lands, the Service assisted the Resettlement Administration in relocating people. H.H. Van Winkle, for instance, was detailed from the Service to assist the Southeastern Idaho Project to purchase farms and make it possible for people to move. Most relocated in the Willamette Valley of Oregon or the northern panhandle of Idaho. [3]

With the Resettlement Administration (later the Farm Security Administration), the Forest Service also assisted in administering three projects in the Intermountain Region. These were the Southeastern Idaho Project (later the Curlew Grasslands) and two projects in Utah; the Widtsoe Project, situated in the Sevier River drainage near the Escalante Mountains; and the Central Utah Project, near the Vernon Division of the Wasatch National Forest. The Widtsoe project later became part of the Powell and later the Dixie National Forest, and the Central Utah Project later became the Intermountain Station's Benmore Experimental Range. [4]

Organization

Between 1929 and 1934, a number of other administrative and facilities changes affected the Intermountain Region. On May 1, 1929, the Secretary of Agriculture approved a change in the official designation of the nine Forest Service districts. Henceforth, they were to be called "regions," perhaps to avoid confusion with the increasingly important ranger districts. [5]

Several other administrative changes were made. In 1931, the Service began a shift to a cost accounting system that was designed to provide control of expenditures and accurate investment and depreciation records. By 1940, the system had been implemented in most regions. [6] At the same time, accounting and warehouse functions were decentralized to the regions and forests. [7] Moreover, correspondence during the 1930's indicates an attempt to cut costs by careful management in the use of telephones and travel funds. [8]

A number of changes of regional significance took place. In late 1930, as an economy measure, the Forest Service decided to transfer all purchasing and distribution functions, except stationery and office supplies, from the Ogden Supply Depot to Government Island at Alameda, CA. [9] Earlier in the year, the Service had moved the headquarters of the Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station to Ogden to facilitate closer cooperation with the regional office. The Ogden office functions were expanded to include supervision of all research in the region. The Service considered locating Intermountain Station headquarters at Logan or Salt Lake City, but decided on Ogden because of its proximity to the regional office. [10]

During the same period, the Service decided to construct a new regional office building in Ogden. Deficiencies previously noticed in the existing building had become more apparent, and new defects had appeared. [11] At first it appeared that the Service might purchase and renovate the existing building. Senator Reed Smoot seemed to favor this option, but Regional Forester Rutledge was definitely opposed, since he believed the asking price far too high and the cost of renovation excessive. [12] The regional officers favored fireproof brick and steel construction (rather than the existing brick and wood building) and a location in a "more respectable and cleaner part of town." [13] Also, while the space vacated by the Supply Depot was about the size the Intermountain Station needed, it was not suitable for their purposes.

These considerations led to the construction of a building on the corner of Adams Avenue and 25th Street. Owned by Julia Kiesel, the site was situated across from the Weber College campus, in a very desirable neighborhood. [14] Architects Leslie S. Hodgson and Myrl A. McClenahan of Ogden designed the lovely Art Deco structure, completed in February 1934. [15]

|

| Figure 37—Intermountain Regional Office Building at Adams Avenue and 25th street. Ogden, Utah, 1938. |

Over the period, facilities on the forests also changed. A number of forest offices, the Minidoka, for example, were housed in local Federal buildings. [16] In 1934, the old Assay Office in Boise was remodeled: the Payette National Forest moved upstairs, and the Boise National Forest used the main floor. [17] Some ranger district offices were located in facilities constructed during the period, as in the case of the Kamas Ranger District of the Wasatch National Forest. [18] In others, as in the case of the Spanish Fork Ranger District of the Uinta National Forest, officers were located in the basement of post office buildings. [19] As late as the 1930's, on the Stanley district of the Sawtooth, a ranger cabin was constructed of logs. [20]

Between 1933 and 1945, the Service made several changes in configuration of the region, rounding it out to approximately its present size. In 1933, since the construction of a bridge over the Colorado River above Lee's Ferry and the imminent completion of Hoover Dam established highway communication between the Arizona Strip north of the Grand Canyon and the remainder of the State, the decision was made to transfer administration of the Kaibab National Forest to Region 3 (New Mexico and Arizona). The Chief Forester believed that, even though most of the forest users were from Utah, the division of responsibility between the two regions for contact with Arizona State officials made the transfer advisable. [21]

Another important change consolidated jurisdiction over the national forests in Nevada in Region 4. During the 1930's, Region 4 made a number of changes in the forests in Nevada. In 1932 the three Nevada forests (the Nevada, Humboldt, and Toiyabe) were consolidated into two (the Nevada and Humboldt) eliminating the Toiyabe supervisor's office at Austin. In early 1938 the region redivided Nevada into three forests (Nevada, Humboldt, and Toiyabe) with headquarters at Ely, Elko, and Reno and subsequently transferred the Charleston Mountain division from the Dixie to the Toiyabe. [22]

In 1938, the headquarters of the Mono National Forest (in Region 5) was moved from Minden to Reno. [23] The Service recognized the problem of having two forest headquarters in one city each responsible to different regions. Even though Reno was much closer to San Francisco than to Ogden, the Service decided to consolidate its operations under Region 4 rather than Region 5 for a number of reasons. Most of Nevada was already in Region 4, so the same logic that dictated the transfer of the Kaibab to Arizona favored that decision. In addition, although, as the disputes over continued Federal regulation of grazing indicated, Nevadans tended to be antigovernment, ties within the livestock communities in Utah and Nevada were quite close. In the mid-1930's, Region 4 had begun cooperative research programs with the University of Nevada. Furthermore, the personality and experience of Alexander McQueen, Toiyabe National Forest supervisor, helped considerably. He had worked in Nevada for 20 years, serving on all three forests. By contrast, his Mono Forest counterpart, D.M. Traugh, had been transferred from California to Reno only in 1938. [24] McQueen had developed broad political and social friendships throughout the state. Consequently, in early 1939, the Chief designated him and thus Region 4 as Forest Service representative for state relations in Nevada.

|

| Figure 38—Old Boise Assay Office, headquarters of the Boise and Payette National Forests. Regional Forester Richard H. Rutledge and Boise Supervisor Guy B. Mains, September 1935. |

The Service considered the Toiyabe-Mono consolidation in 1939, but did not consummate it until 1945 when the Mono was abolished and its lands transferred to the Toiyabe and Inyo National Forests and lands on the Nevada side of the Tahoe Basin transferred from the Tahoe to the Toiyabe National Forest. In the exchange, Region 4 actually gained a foothold in California, since that portion of the Mono transferred to the Toiyabe stretched into the Golden State. [25]

One major change that did not materialize would have transferred the Forest Service to the Interior Department, which was to have been renamed the Department of Conservation. Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace, Gifford Pinchot, and conservation organizations like the Izaak Walton League opposed the move. Interior Secretary Harold Ickes pressed for the change at first, but by 1939, opposition was so great that even he declined to recommend continuing the battle. [26] Within the Agriculture Department, officers were ordered not to openly oppose the reorganization and to refer any questions dealing with the transfer to the regional forester. [27]

|

| Figure 39 Map of western regions, Forest Service, 1943. Note Region 4 in center. |

Land Acquisition

The national attitude favoring positive governmental action during the depression facilitated the expansion of Forest Service administered land within Region 4. A congressional resolution of March 1932 produced by March 1933 the "Copeland Report," named after Senator Royal Copeland of New York. [28] The report, written largely under the supervision of Earle H. Clapp, proposed that the Federal and State Governments purchase more of the Nation's forest land to prevent depletion of the lumber supply. The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 included a provision for carrying out this proposal. [29] Earlier, the Clarke-McNary Act of 1924 had authorized the Federal Government to accept donations of lands from the States, and by 1933 Idaho had donated 113,120 acres. [30]

Other legislative changes in the 1930's further facilitated Forest Service land acquisition. By late 1935, a number of States, including Idaho and Utah, had authorized the Service to purchase lands within their boundaries. [31] In that same year, Congress authorized the appropriation of receipts from the Wasatch and Uinta National Forests to acquire private lands within the forest boundaries. [32] Such acts were used principally to buy damaged and eroded watersheds in which floods had often occurred, such as those above Davis County towns and in the Spanish Fork, Hobble Creek, and Diamond Fork watersheds of Utah County in Utah and above Arrowrock Dam in the Boise River drainage in Idaho. [33] In addition, during the 1930's, the exchanges of private land for national forest timber were continued with the Boise-Payette lumber company. [34] In 1939, lands in Dog Valley on the Carson District of the Toiyabe National Forest were purchased largely for watershed rehabilitation. [35]

Personnel

During the 1930's, the backgrounds of staff members changed considerably. When James Jacobs started work on the Lemhi in 1929, there were very few college graduates he knew of in the region. Some college men worked in the regional office, but nearly all the supervisors and rangers were "horseback" field men who had passed the old ranger examination. [36] From about 1930, the Service required a degree in forestry or range management for appointment. [37] Appointment came after successful completion of the Junior Forester or Junior Range Examiner test. Forestry schools such as Utah State helped their graduates to prepare for Civil Service exams by keeping files of old tests and asking students to write down questions and submit them to the school as soon as they completed the exam. [38] Both the college-trained and horseback foresters took training courses in various aspects of forest and range management during the winter. When a horseback ranger had completed a certain number of courses he was given a certificate designating him a Practicing Forester. [39]

The makeup of office staffs remained much as before. As late as 1960, most rangers had no secretaries, and they did their own office work. [40] They had, however, field crews that worked during the summer on such functions as trail and building construction and maintenance and on fire control. [41]

Turnover and movement into and out of the Forest Service and region continued to be the norm for regional officials. In 1930, of 24 officials who had served either as regional forester or as head of a division within Region 4 (excluding incumbents), 15 (or 63 percent) were no longer with the Service. One was deceased, and six were serving elsewhere in the Service (including two—Sherman and Kneipp—in the Washington Office). Only two—A.C. McCain, Supervisor of the Teton National Forest, and Clarence N. Woods, then Chief of Operations—were serving in Region 4. [42]

|

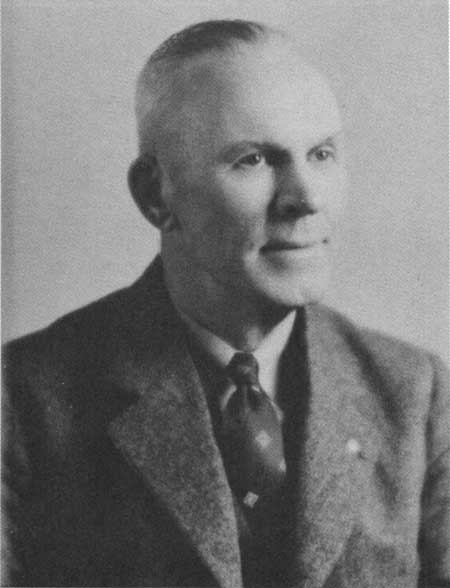

| Figure 40—Richard H. Rutledge, Regional Forester, 1920-38. |

In 1939, Woods became the first of three consecutive regional foresters who worked up through the ranks in Region 4. In 1935, Woods had moved from Operations to become Associate Regional Forester. After serving more than 36 years in other positions in the region, he became Regional Forester on January 11, 1939, replacing Rutledge, who was appointed Chief of the Grazing Service in the Interior Department. [43]

Inspection

The inspection system continued as an important means of regulating work in the region. Until the late 1930's, most inspections were of specific functions, such as grazing or office procedures, or they were general inspections in which the various functions were considered. [44] In 1939, the Service started what were called General Integrating Inspections of the regions by Washington Office personnel. In this type of inspection, in contrast to previous methods, inspectors made a conscious attempt to determine how the various functions fit together, how the regional officers related to the public, and how well their various styles of administration worked. [45]

|

| Figure 41—Clarence N. Woods, Regional Forester, 1939-43. |

Public Works and Civilian Conservation Corps Programs

Perhaps the most important changes during the 1930's came about because of the increased availability of labor on the forests, particularly through the introduction of public works programs, especially the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). The Intermountain Region benefited, on a per capita basis, from CCC expenditures more than any other area in the Union. Nevada ($213 per capita), Idaho ($127 per capita), and Wyoming ($108 per capita) ranked first, second, and third in the Nation. Utah (at $70 per capita) ranked seventh. Moreover, CCC enrollees constituted a sizable portion of the total labor force in these States. In Utah, where the enrollment was lower per capita than the other States in the Intermountain Region, 4.4 percent of the labor force in 1940 consisted of CCC enrollees, making the CCC the third largest source of employment, behind agriculture and metal mining. [46]

Moreover, the Forest Service benefited more than other conservation agencies from the work of the CCC enrollees. The program was designed principally to improve conservation of natural resources, and since the Forest Service already had a number of such programs underway and had drawn up plans for much more work, it surpassed other agencies in the allocation of camps. Though the Army actually administered the camps, the Forest Service planned and supervised the work. [47]

The situation in Utah was typical of the Intermountain Region. Of 116 CCC camps in Utah the Forest Service operated 47—nearly twice as many as the second-ranked U.S. Grazing Service, which operated 24. [48]

Watershed Protection and Improvement

Although the CCC benefited the region through the construction and improvement of a variety of facilities, its greatest importance was undoubtedly in building erosion control devices, roads and trails, and recreation facilities.

From the beginning, much of the research at the Great Basin Station consisted of work on the causes and prevention of flooding and watershed deterioration. This was extremely important in Region 4, where overgrazing had produced such devastating floods for so long.

Particularly severe were dry-mantle floods, following summer thunderstorms, which continued to be frequent occurrences for many communities. Floods from the Manti National Forest descended in August 1909 on Ephraim, [49] and in June 1918 on Mount Pleasant. [50] Between 1923 and 1936, floods from above Willard in Box Elder County near the Cache National Forest destroyed 40 homes, killed 2 people, washed out the municipal irrigation systems, and destroyed the municipal power-plant. [51] Floods that originated above Davis County towns north of Salt Lake City near the Wasatch National Forest wreaked havoc on farms and homes during the 1920's.

Similar flash floods in uninhabited areas caused considerable damage through sheet erosion on hillsides, digging gullies through forests and ranges, and washing out irrigation works. A report on the Powell National Forest in 1915 revealed a number of watersheds on which erosion had done considerable damage. [52] An investigation in 1927 of the LaSal National Forest by Regional Engineer J.P. Martin, Regional Forester Richard H. Rutledge, and Acting Forest Supervisor L.T. Quigley found erosion problems in a number of places throughout the forest. [53] A 1930 investigation of the Sawtooth by C.N. Woods, M.S. Benedict, and E.G. Renner discovered "widespread" sheet erosion. Gully erosion of the sort found on the LaSal had not yet become a serious problem, but the investigators recognized it as a threat which at the current rate of grazing would materialize within 5 years. [54]

The first steps in dealing with damage involved working with individual communities to stabilize damaged watersheds. The Manti forest watersheds had more serious problems than most, but the interests there were quite similar. Forest Examiner Robert V.R. Reynolds completed a study of flood conditions on watersheds in 1910. [55] Townspeople petitioned the forest supervisor, complaining of the destruction of their irrigation works and crops and urging restraint in granting of grazing privileges. [56] Stockmen, on the other hand, resisted the reductions, appealing to Senator Reed Smoot to help them. [57] Some reductions in numbers of sheep did take place, but by the early 1920's, conditions were still far from optimal. [58]

In some cases, people in the cities and towns petitioned to have damaged watersheds included within the forest. In the case of Hobble Creek above Springville, for instance, petitions from the mayor, the president of the Board of Trade, and people from Springville and nearby Mapleton asked that the drainage be included in the Uinta National Forest. [59] The situation remained critical, and in 1929, the Federal Government considered purchasing nonagricultural private lands in the Hobble Creek drainage. [60]

In other cases, the Service planned watershed treatment in addition to permit reductions. This was the case on the LaSal National Forest, where such measures as timber cribs and check dams were proposed for those watersheds that were above areas of expensive improvements. [61]

Flooding from watersheds above Davis County towns became so serious that in 1930 Utah Governor George H. Dern appointed a committee to investigate. Headed by Sylvester Q. Cannon, formerly Salt Lake City Engineer and then Presiding Bishop of the Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-Day Saints, it included engineers, geologists, foresters, and public representatives. [62] The committee's recommendations included acquisition by the State or Federal Government of the watersheds of Parrish, Ford, Davis, and Steed Canyons, prohibiting grazing in the area, reseeding, constructing check dams, and establishing fire prevention measures. On a more general level, the committee recommended that the State inaugurate a comprehensive watershed control policy. [63]

The major problem in developing erosion control projects was in conceptualizing the means of dealing with the problem. [64] During the 1920's, the State of Utah constructed catchment basins below some of the canyons subject to heavy mud and rock floods. This caught some of the runoff, but did not stop the flooding itself.

|

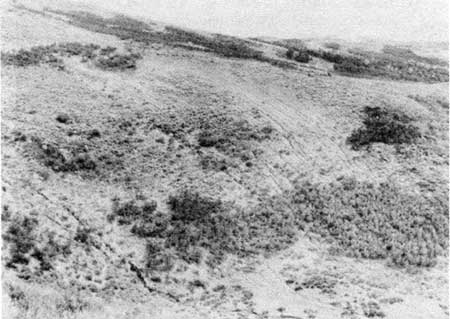

| Figure 42—Ford Creek sheep corral and water hole, Davis County experimental watershed, 1946. Note recovery of vegetation. |

After a mud and rock flood in Davis County in July 1930, Clarence L. Forsling of the Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station asked Reed W. Bailey, then professor of geology at Utah State, to investigate the situation. Bailey opined at first that the cause was simply runoff from cloudbursts dumping water on the mountaintops. Forsling suggested, however, that the runoff might have resulted from the denudation of watersheds. Bailey rethought the problem, and the two brought in others including Raymond J. Becraft, professor of range management at Utah State, and Milo H. Demming of the Forest Service. Working with a subcommittee from Davis County headed by Joseph Parish, Davis F. Smith, and Delore Nichols, they coordinated their efforts with Supervisor Chester J. Olsen of the Wasatch National Forest and Ranger Felix Koziol of the Farmington Ranger District.

Forsling, Bailey, and Becraft published the results of their research in 1934. They argued that the floods, rather than being common phenomena over a long period of geologic time, were of recent origin, starting from relatively small areas at the heads of canyons depleted of plant cover. [65] Their theories were not universally accepted. Opposition came from Frederick F. Hintze of the University of Utah, Ralph R. Wooley of the Geological Survey, and J. Cecil Alter of the Weather Bureau. They argued that such floods were prehistorically common and the natural results of geological conditions. Forsling and the others got support, however, from Walter P. Cottam of the University of Utah and George Stewart, then at the Desert Range Experiment Station, who argued that the contradictory data were faulty. General acceptance of Forsling committee views within the Forest Service allowed them to use their theories as a means of conceptualizing a solution. [66]

|

| Figure 43—Severe erosion at Ford Creek flood source, Davis County experimental watershed, 1930. |

However, carrying out the work required both money and labor, neither of which was available until the CCC was organized in 1933. [67] Five CCC camps in Utah were set up to deal with watershed control. Arnold Standing assumed general supervision for the Forest Service, and Forsling and Bailey (the latter on loan from Utah State) mapped out work on three projects—Willard Basin in Box Elder County, the mountains above Davis County towns, and Kolob Basin above Provo and Springville in Utah County.

During 1933 the CCC enrollees used methods adapted from those pioneered by Arthur Sampson at the Great Basin Station in 1916. Attempting to retain part of the water and reduce the speed of its flow high on the mountain, they constructed small outsloping trenches using horse-drawn plows and ditchers. In addition, they reseeded the hillsides and constructed rock and wire gabions and checkdams in the gullies. Significantly, they also succeeded in getting livestock removed from the watersheds. [68]

Unfortunately, the small trenches did not work as well under these large-scale conditions as they had on the micro-plots at the Great Basin Station. To improve their holding capacity, Forsling and Bailey revised the design to specify an outsloping contour trench of sufficient size to hold all the runoff from any anticipated summer storm. They also specified the use of bulldozers rather than horse-drawn equipment in the construction. Using this plan, the CCC constructed trenches above Davis County, in Willard Basin, above Provo, and in other areas throughout the region. [69]

In the meantime, A. Russell Croft, who emerged as a leader in watershed research in the west, and George W. Craddock, who became acting director of the Intermountain Station when Forsling transferred to the Appalachian Station in 1935, established the Davis County Experimental Watershed. On this project, they experimented further with methods of watershed control. Croft eventually designed the large-capacity insloping contour trench, which became the standard for use on projects throughout the region. [70]

CCC enrollees constructed other watershed and stream improvements on many forests throughout the region. In southern Nevada, they built dams, levees, ditches, and other structures. [71] On the La Sal, they did flood control work. [72] On the upper Provo River they improved fish culture by constructing small dams and shelters. [73]

|

| Figure 44—Ford Creek flood source rehabilitated, Davis County experimental watershed, 1945. |

CCC Recreation Facilities

As with watershed improvement, in the development of recreation facilities, the Forest Service provided planning, expertise, and supervision, and the CCC furnished the labor. Before the CCC was organized, the region had received very limited recreational funds—usually $4,000 to $7,000 per year. Thus, virtually all the region's recreational facilities were either constructed or reconstructed by the CCC. [74] At times the Service would furnish as many as three or four landscape architects to design the facilities. The engineering department worked out the plans and technical specifications for recreation area water and sewer systems, roads, and buildings. [75] On the Boise National Forest the CCC constructed such recreational facilities as tables, toilets, and bathhouses. [76] In Big Cottonwood and Mill Creek Canyons and at Aspen Grove on the Wasatch, they constructed a number of amphitheaters. [77] At Mirror Lake, they burned into plywood a large map of the High Uintas Primitive Area for the information of users. [78] The CCC constructed virtually all the campgrounds on the Payette, since there had been only two established campgrounds prior to the 1930's. [79] On the Wasatch and Cache they constructed ski lodges at Alta and Snow Basin. [80]

|

| Figure 45—Cars parked for recreation at Theatre-in-the-Pines, popular alpine loop recreation site built by the CCC. |

CCC Road and Trail Construction

CCC work on road and trail construction was of immense importance. In western Idaho, the CCC constructed roads in virtually all the major drainages including the Middle and South Forks of the Boise, South Fork of the Payette, and South Fork of the Salmon. [81] They constructed at least 13 trails on the Wasatch. [82] In some cases, the CCC reconstructed primitive roads to a higher standard, as on the South Fork of the Payette. [83] In southern Utah, they constructed a new road from Escalante to Boulder, providing the first road access for Boulder. [84] On the Humboldt, the CCC built a road in Lamoille Canyon. [85] A major project in Central Idaho was the construction of a road down the Salmon River from North Fork toward the Middlefork. [86] The CCC also constructed a landing field at Hoodoo Meadows on the Salmon. [87]

CCC Forestry Work

The CCC assisted in timber stand improvement, seed collection, reseeding, and insect detection and control. On the Uinta, they worked on thinning lodgepole pine stands. [88] On the Boise they gathered tree seeds and planted seedlings. In October 1940, they planted 80,000 ponderosa pine seedlings on the Elk Creek burn near Idaho City. [89] On the Spanish Fork district of the Uinta, the first artificial grass reseeding other than that done on sample plots was done by the CCC in October 1935. [90] In Utah, the CCC planted more than 100,000 trees during 1933-34. [91]

CCC Building Construction

CCC crews aided immensely in improving the physical facilities within the region. In 1938, the region realized it needed centrally located repair shops to maintain its equipment. George Kreizenbeck was assigned to supervise CCC labor constructing shops in Salt Lake City, Cedar City, Reno, and Boise. [92] Crews built warehouses, lookouts, barns, and ranger stations. [93] Dewitt Russell remembers that the number and condition of ranger stations on the Weiser were quite inadequate until the CCC constructed new stations or reconstructed old ones. [94] On the Fishlake they constructed a complex consisting of an office, three dwellings, a warehouse, a painthouse, and storage building at Twin Creeks. [95] On the Humboldt, crews constructed a ranger station at Lamoille. [96] In fact, administrative and living quarters were constructed by the CCC on most forests in the region.

As the Intermountain Station continued the expansion of its experimental work, the CCC assisted in the development of new research facilities. In 1933 the Chief approved establishment of the Boise Basin Experimental Forest for research on timber management, soil erosion, and range management problems. A great deal of the construction was done by CCC crews. [97] They also built about 100 miles of fence and 95 miles of roads on the Desert Experimental Range in Pine Valley. [98]

|

| Figure 46—CCC enrollees from Camp F-167 transplanting beaver from Terry Ranch on Panther Creek to Big Deer Creek, August 1938. |

CCC work in the region did not go forward without some difficulties. Controversy developed, for instance, over political intervention. Congressmen from districts containing CCC camps forwarded names of prospective appointees to Julian N. Friant, special assistant to the Secretary of Agriculture, who in turn expected Forest Service officials to select supervisors from a list he prepared. [99] In 1933, the regional office received a letter from a congressman asking them to fire a politically unacceptable camp superintendent. The regional office resisted and was saved from dealing with the problem when the camp was discontinued. [100]

Congressmen Abe Murdock of Utah and Thomas C. Coffin of Idaho were particularly insistent that the Service appoint deserving Democrats since in 1933 the majority of the camp supervisors were Republicans. Ernest Winkler from the Regional Office came to the Escalante Ranger District to ask Carl Haycock to remove the Republicans and hire Democrats. Haycock refused and was transferred to the Humboldt National Forest. [101] Whether this was an isolated case is not known.

CCC Engineering

The Forest Service benefited so much from the CCC work largely because the engineering division planned facilities effectively, forest officers implemented the plans with sensitivity, and forest officials conducted thorough inspections of the ongoing work. In 1935, for instance, the division revised its building construction manual, outlining specifications for everything from alteration of roof lines to yard development. [102] In routing a telephone line from Dubois, ID, across Togwotee Pass to Moran, WY, Teton Supervisor McCain insisted that the Mountain States Telephone Co. take scenic values into consideration. [103] Engineering inspections checked projects for compliance with specifications and to make sure that the job was done in a conscientious manner. [104]

Forest Service Improvement Work

CCC crews did not do all construction work, since some of it was still done by the rangers. Before CCC days, rangers on many forests were organized into improvement crews during nonfield seasons to build bridges, barns, and other improvements and to work on insect control and timber surveys. [105] John Raphael had two of his rangers build a log cabin in the high country for a late fall camp. After it was completed, Raphael went on an inspection trip. After looking over the cabin, he inspected the two-hole privy out back and was somewhat mystified to find one very large hole and one very small one. Posted by each were the instructions, "Rangers with $1.20 per diem, use the small hole" and "Supervisors and visiting inspectors with $2.40 per diem, use the large hole." [106]

|

| Figure 47—CCC enrollees from Redfish Lake Camp painting Stanley Ranger Station, 1933. |

As technology changed, the Service adopted those features that seemed most appropriate. Until the 1930's mapping generally was done with the traditional plane table and alidade: after that the Service began using aerial photography. [107]

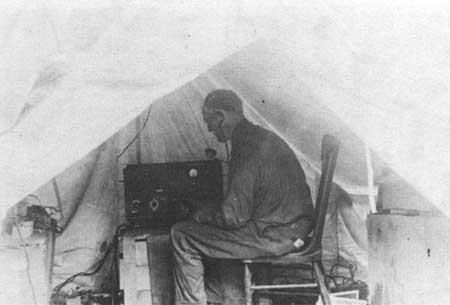

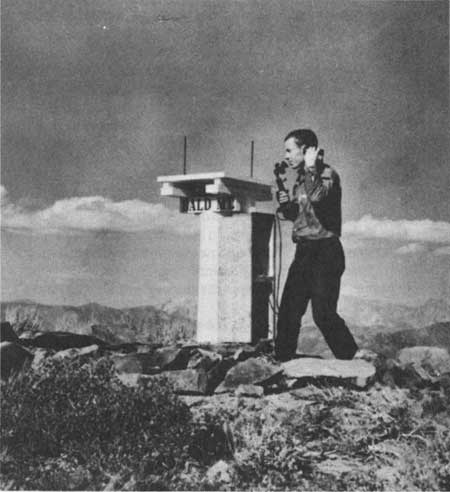

In the late 1930's, the regional forester assigned Francis W. Woods to improve the region's telephone system and to develop a radio system. [108] By then the region had perhaps 5,000 miles of telephone circuits, all of them of the ground-return type. Cross-talk with adjacent lines was often a problem. Woods concentrated on improving the telephone installations in Idaho, since in Utah and Nevada the systems were provided by local independent telephone companies.

In an attempt to improve one system, Woods put in a new phone at a ranch on Big Creek on the Idaho. They had trouble getting a good ground, so Woods went to the outhouse and drove a couple of rods into the pit. He then called Supervisor J.W. Farrell at McCall, who commented on how good the connection was. Woods told him they had used an old outhouse for the ground. Farrell replied that he had heard a lot of the stuff over the line before, but "this is the first time I've talked through it."

In addition to improving the telephone system Woods also began development of a regional radio network. He went to the Forest Service radio laboratory at Portland to learn about available equipment. Since none was available commercially, the Service designed its own. The Service developed three types of radios, the M set, an SPF semi-portable, and a smaller set. [109] After designing the equipment, the Service convinced General Electric and Motorola to build it for them. They picked the Lemhi to receive the first radio system, since it had such poor telephone service. Thereafter they assigned systems to other forests in the region with frequencies for both AM and FM reception.

|

| Figure 48—Telephone engineer R.B. Adams operating a portable wireless set in the field. |

Woods worked out an arrangement with Utah State Agricultural College to train operators. In return the Service allowed the college to use its equipment, which was superior to others on the market.

At times, Woods found it difficult to get operators to read and follow instructions. On one occasion he received a call at Ogden from the fire chief that the radio on Jackson Lake, WY, would not work. Woods drove all night and after arriving he asked the operator what was wrong. "I don't know," the employee replied. "It won't work." Woods checked the receiver and found it functioning normally. On the side of the unit were instructions on how to tune the transmitter. He asked the operator if he had read the instructions, which said to tune the radio below the "dip." The operator said "Yes, but I thought I would get more power if I tuned it above the dip." Woods then realized he had spent all night driving nearly 400 miles to teach the operator to follow instructions!

Watershed Management

The Service moved to improve its watershed management techniques. As early as 1915, the Service had begun to cooperate with the Weather Bureau in "snow stake" measurements. In 1930, snow surveys were established by the Utah Experiment Station in cooperation with the Forest Service and the Weather Bureau. As part of the agreement, the Service made surveys over 45 snow courses on national forests in Utah. As early as 1931, these snow surveys made possible annual planning of sugar beet contracts by the Amalgamated Sugar Company on the basis of anticipated runoff. [110] Similar snow courses were established and surveyed in the mountains of Nevada, Idaho, and Wyoming. [111]

The Service determined the dimensions of watershed problems through detailed studies of the various important drainages. In 1936, for instance, it published reports on the three major drainages in the region—Great Basin, Snake River, and Colorado River. [112] In 1940, the Forest Service, in cooperation with the Soil Conservation Service and the Bureau of Agricultural Economics, produced a detailed survey of the problems of runoff, water-flow retardation, and soil erosion prevention on the Boise River watershed in Idaho, where serious flooding, siltation, and erosion had occurred. [113]

Recreation Management

While some forest officers had begun to recognize the importance of recreation by the 1920's, it was not until the 1930's that it really achieved a significant place in the Service's overall planning. By then the Forest Service provided recreation for four times as many people as the National Park Service. Robert Marshall, who authored the recreation portion of the Copeland Report, recognized the importance of recreation to the increasingly multiple-use oriented philosophy of the Service. To address these concerns, the Washington Office organized the Division of Recreation and Lands in 1935. [114]

Conditions in Region 4 were similar to those in the Service in general. During the 1930's, visits to the national forests of the Intermountain Region increased considerably. Moreover, the emphasis of the visits changed from hunting and fishing to camping and picnicking. (See table 8.) [115]

Table 8——Trend of recreational use on some National Forests of Region 4, 1934-42

| No. of visits | ||||||

| Year | No. of visitors |

% of Change Since 1934 |

Campgrounds | Picnic Areas |

Resorts & Hotels |

Special Use |

| 1934 | 712,125 | 344,590 | 298,240 | 37,440 | 31,885 | |

| 1935 | 882,510 | 24 | ||||

| 1936 | 1,400,240 | 97 | ||||

| 1937 | 1,360,610 | 91 | ||||

| 1938 | 1,473,570 | 107 | 389,010 | 919,660 | 110,870 | 54,030 |

| 1939 | 2,260,598 | 217 | ||||

| 1940 | 2,520,947 | 254 | ||||

| 1941 | 2,295,072 | 222 | 519,579 | 989,826 | 167,429 | 39,209 |

| 1942 | 1,698,593 | 139 | ||||

Source: "Trend of Recreational Use, Within Some National Forests of the Intermountain Region. 1934-1942," File: 1650. Historical Library. Historical Items (General) Teton, 1940-1970, Bridger-Teton. Unfortunately, the data did not indicate which forests in Region 4 were included in the survey. | ||||||

Because of increasing use, planning for recreation became vital. Before Kenneth Maughan left to pursue a graduate degree in forestry at Syracuse, he told an assistant regional forester that he thought recreation had a big future and that he wanted to get additional training in the field. The officer discouraged him, saying that the future did not justify such a step. Nevertheless, T.G. Taylor, head of the forestry school, urged him to do so. [116] Maughan had the full cooperation of the Washing ton Office: L.F. Kneipp, by then assistant chief, approved the distribution of a recreation questionnaire, which Maughan developed, to all forest supervisors. [117]

As a result, Maughan wrote a master's thesis that included a nationwide sample of information on recreation. The results showed that although many supervisors did not believe that recreation development was important, those in California, the Pacific Northwest, and parts of Utah, Idaho, and Arizona considered it significant. [118]

After reviewing the literature and compiling the results, Maughan reached some important conclusions. By 1931 "recreation use was far in advance of recreational development." He predicted that such use might "cause destruction of many outstanding recreational areas unless plans are immediately made and executed." Maughan concluded that recreation was an important economic resource, with implications for a wide range of other forest uses and that the Service could not continue with little planning for such an increasingly important function. [119]

Between 1931, when Maughan finished his thesis, and the late 1930's, the region moved vigorously to develop recreational opportunities. The availability of emergency appropriations and CCC crews allowed this acceleration. In 1935, the region hired A.D. Taylor, a consulting landscape architect, to prepare a report on recreation facilities and needs. [120] In 1935, the Regional Office published a separate recreation handbook replacing the section in the previous lands handbook. [121] Regional officials concentrated on the development of recreational facilities in particularly significant areas such as the Sawtooth-Salmon river country. [122] The forests wrote and initiated action on recreation master plans. [123] By the late 1930's, inspections increasingly emphasized the condition of recreational facilities. [124]

|

| Figure 49—Custer campground, Yankee Fork, 1937. |

Public recognition of the importance of recreation was increasingly evident. At the national governors conference in October 1931, Governor George H. Dern of Utah, the chairman, rated the three great uses of the national forests as timber, grazing, and recreation, adding that "in some cases recreation is the highest use." [125] At its annual convention at Cody, WY, in October 1937, the dude ranch association passed resolutions urging the Forest Service to restrict tie hacking operations, permits for summer homes, and road construction to foster their businesses, which sought a solitary—if not a wilderness—experience for their customers. [126]

Even with such recognition of its importance, recreation did not receive as high priority as timber, range, or watershed management. James Jacobs remembers that while he was a ranger on the Caribou in the 1930's, when campground garbage cans needed emptying, his wife would drive the pickup truck, he would dump the cans, and the two of them did the campground cleanup. [127]

|

| Figure 50—Packing up at G.P. Bar Ranch, a guest ranch, 1935. |

Wilderness Management

The designation and protection of wilderness areas became an important facet of recreation, particularly as a result of the desire of many to recapture the feeling of outdoor life in times past. Evidence indicates that in the designation of primitive areas in Region 4, this nostalgic quest was a much more important consideration than the desire for solitude. Wilderness leadership in the Forest Service came from Arthur Carhart, Aldo Leopold, Robert Marshall, and William Greeley. Greeley thought that the National Park Service seemed most interested in developed recreation and that the Forest Service could provide an alternative. [128]

In 1924, Greeley had designated the first wilderness area in the Gila National Forest in New Mexico, and he urged the consideration of other areas. [129] In December 1926, Greeley had asked all regional foresters to review road development plans to make sure that they did not needlessly invade areas best adapted for wilderness and to safeguard such areas against summer homes, hotels, and commercial enterprises. [130] Under Greeley's policy, L.F. Kneipp had drawn up general regulations for wilderness designation in 1928. [131]

The concept of wilderness in the late 1920's and early 1930's differed from that generally understood today. Since a major purpose of the wilderness areas under that concept was to recapture a sense of past times, Robert Y. Stuart, Greeley's successor, could argue quite consistently in 1928 that wilderness designation would not unduly "curtail timber cutting, grazing, water development, mining, or other forms of economic utilization . . . but rather . . . guard against their unnecessary invasion by roads, resorts, summer-home communities, or other forms of use incompatible with the public enjoyment of their major values." [132] Thus, some forms of environmental change could be allowed, but economic activities and recreation involving technological development were excluded. Stuart envisioned areas "within which primitive conditions of subsistence, habitation, transportation, and environment will permanently be maintained to the fullest practicable degree." [133]

By 1937, the Service had set aside 72 primitive areas of 13.5 million acres in 10 Western States. [134] Within Region 4, the Chief designated the first primitive areas in 1931 after study and recommendation by the forest supervisors and the regional forester. These included the High Uintas Primitive Area in the Wasatch and Ashley National Forests, the Idaho Primitive Area in the Payette, Boise, Challis, and Salmon National Forests, [135] and the Bridger and Teton Wilderness areas in the Wyoming (later Bridger) and Teton National Forests. [136] The Hoover Wild Area was established in the Mono (later Toiyabe) National Forest in 1931, and the Sawtooth Primitive Area in the Boise, Challis, and Sawtooth National Forests was designated in 1937. The only other wilderness area designated before the Wilderness Act in 1964 was the Jarbidge Wild Area in the Humboldt National Forest in 1958. [137]

Region 4's rationale and conception of the primitive areas were essentially the same as throughout the Service. The High Uintas and Idaho Primitive Areas can serve as examples.

The High Uintas area was seen as offering an opportunity "to the public to observe the conditions which existed in the pioneer phases of the Nation's development, and to engage in the forms of outdoor recreation characteristic of that period, thus aiding to preserve national traditions, ideals, and characteristics, and promoting a true understanding of historical phases of national progress." Use of "timber, forage, or water resources" was not precluded, "since utilization of such resources, if properly regulated," was not perceived as "incompatible with the purpose for which the area is intended." [138]

The various considerations in primitive area designation also were apparent in the proposal for the Idaho Primitive Area. A committee of various interest groups appointed by Idaho's governor and chaired by Harry C. Shellworth of the Boise-Payette Lumber Company considered the proposal. In general, livestock, farming, timber, game, mercantile, and horticultural interests favored such an area. The opposition came from mining interests and some who feared control by bureaucracy or the creation of a playground for the wealthy at the expense of hard-working ranchers and miners. [139]

During the 1930's, some primitive areas, such as the Bridger, were not heavily used, whereas others, such as the High Uintas, had many visitors. On the latter, the principal problem was trail maintenance, particularly to prevent erosion. This was done by putting in cross-bars to direct the runoff into ground cover as soon as possible. [140]

Wildlife Management

By the 1930's, the problem of excessive wildlife, which had become such a burden on the Kaibab in the 1920's was apparent throughout the region. Most significant was the expansion of deer herds and, to a lesser extent, of wild horses and elk. Statistical evidence indicates that the populations of virtually all big game animals, with the exception of mountain goats, bighorn sheep, and bears, increased rapidly.

The increase in deer was most significant: they constituted 86 percent of all big game animals on the national forests in 1935. [141] The situation on some forests, especially those in southern Utah, was extremely serious. Hanmer Christensen said that during the 1930's all browse plants were highlined, and they could not find an aspen leaf within reach of a deer. [142]

Wildlife specialists and ranchers pressed the Service and the Utah Fish and Game Department to control populations of elk and deer to improve survivability and prevent excessive competition with livestock. Inadequately staffed with professional people, the Fish and Game Department seemed unable to deal with the conflicting pressures. Under the circumstances, the Forest Service officers were placed under enormous pressure to take action similar to that taken on the Kaibab.

The Utah State legislature tried to address the problem of big game overpopulation. [143] In 1927, the legislature created the Board of Elk Control with members representing sportsmen, wool growers, cattle and horse breeders, the Forest Service, the State Park Commission, and the commissioners of the county in which each game refuge was situated. Elk permits were granted by public drawing.

This did not, of course, address the problem of deer overpopulation, and the board itself was quite large and somewhat unwieldy. In March 1933, the legislature established the State Game Refuge Committee and Board of Big Game Control, usually called simply the Board of Big Game Control, consisting of five members to replace the Board of Elk Control. Members represented the cattle and horse breeders, wool growers, sportsmen, the Forest Service, and the State Fish and Game Director, who served as chairman. The board was empowered to conduct investigations, designate game refuges, set special hunting seasons, and designate the areas and number and sex of big game animals to be killed.

The board faced enormous resistance from the general public, particularly from hunters, to the idea of killing does. [144] In the fall of 1934, for instance, the board issued the first special doe hunting licenses. As Orange Olsen put it, one would have thought the doe hunter was killing "something holy, more so than the 'sacred cow' of India." While the board authorized antlerless deer permits in 1935 as well, they were not issued in 1936 or 1937, since hard winters had taken a heavy toll of animals. In 1937, the Utah legislature authorized the Fish and Game Commission to use license fees to protect the animals and commissioners expended the money to buy winter game ranges and to feed deer. These measures proved inadequate and a study by Everett R. Doman and D.I. Rasmussen of the Intermountain Region indicated the need to further reduce numbers. As a result, special doe hunts were reinstituted in 1938 and continued into the 1940's. [145]

|

| Figure 51—State deer checking station, Beaver Canyon, Fishlake National Forest, Utah, 1938. |

Range Management

Because big game and livestock fed in the same areas, their condition was closely related. In fact, the range deterioration attributed to deer in southern Utah was at least partly the result of livestock overgrazing. [146] In general, the problems encountered during the teens and twenties continued into the 1930's. A major obstacle to concerted action was in achieving a consensus within the Service on how far to go in reducing livestock numbers to protect the range resource, in the face of economic distress on the part of stockmen. This was a particularly pertinent question because of the drought during the years 1933 through 1935. [147]

The Service continued to have difficulty with grazing fees. On the basis of the negotiations following the Casement report, the Service increased grazing fees between 1928 and 1931. By 1933, however, livestock prices had declined so much that ranchers pressed again to relate grazing fees to market conditions. In May 1933, the Agriculture Department agreed to set grazing fees by using a ratio of the previous year's average livestock prices to prices during the 1920's using the 1931 grazing fee as the base. This established a sort of parity for grazing fees, comparable to the agriculture commodity parity ratio used in setting price supports. [148]

The generally depressed economic conditions caused a number of permittees on the forests to become delinquent in the payment of their grazing fees. In response, the regional officers resisted pressure to forgive the fees, but urged that forest officers continue to try to make collections without being offensive in pursuing the matter. [149]

Inspections during the early 1930's revealed that measures taken during the late 1920's had been insufficient to produce satisfactory improvement on the region's range. An inspection of the Minidoka in 1930 revealed that on many allotments little attempt had been made to use grazing survey recommendations to achieve proper stocking. [150] In his 1930 grazing report, Guy Mains on the Boise admitted that the stocking "allowance requested is not based upon a reasonable permanent carrying capacity of the range: it is based upon grazing preferences already established. The allowance for the next few years" he said, "will be downward since the range is overstocked and overgrazed." [151] Data from the Sawtooth indicated a general deterioration in forage conditions on charted quadrats between 1925 and 1931. [152]

The difficulties in arriving at a consensus on the methods for securing proper stocking were evident in two events during the mid-1930's. The first was a meeting in November 1934 of officers from various regions and the Washington Office on management of the range. The second was the publication in 1936 of the Norris report on ranges and their management in 1936.

The diversity of sentiment at the 1934 meeting indicated that range managers still lacked agreement on either the desirability of reductions for range improvement, if it might endanger the short-term economic well-being of the permittees, or on the extent of the problem of overgrazing.

At the meeting, Chester J. Olsen presented statistics that suggested that while allotments were overstocked in all regions except Region 6, overstocking was worst in Region 4. The participants deplored the decline in vegetative quality and the increase of erosion, but arrived at no consensus on investing the money and time to maintain the necessary sample plots and quadrats to provide comprehensive measurements of trend.

Perhaps the divisions among Region 4 personnel were as deep as anywhere. Some officers, such as Olsen, A.R. Standing, and Charles DeMoisy, favored action to study the problem and to take those measures necessary to reduce overgrazing. Others, like Ernest Winkler and James E. Gurr, urged more concern for the economic interests of the stockmen. A third group, including Dana Parkinson and Richard H. Rutledge, took a middle position supporting studies, but urging extreme caution in making reductions. [153] Those at the meeting did agree to reduce numbers about 10 percent in 1935 for range protection. [154]

By 1936 when the Norris report (named for Nebraska Senator George Norris and entitled The Western Range) was published, the internal differences apparent in the 1934 meeting seem to have vanished, at least in public. [155] Prepared under the editorship of Earle Clapp by representatives of the Washington Office, the various regions, and the forest and range experiment stations, the report revealed a consensus, that, despite range improvements under Forest Service administration, depletion caused by overgrazing was still a critical problem. The report recommended a broad range of legislative and administrative initiatives to deal with this problem. It specifically recognized the principle of "multiple use," and recommended that any action taken consider the broad implications for all forest uses. [156] The bulk of the report was written by officers from outside Region 4. Those prominently involved from the region included Arnold Standing, Reed Bailey, George Stewart, and Charles Connaughton.

The report evoked considerable negative comment from some sources. [157] Since it was written by Forest Service personnel and recommended transfer of Interior Department grazing districts to Agriculture Department jurisdiction, it raised opposition within Interior. [158] Because it set the virgin condition of the land as the basis for range rehabilitation, stockmen questioned its conclusions. In addition, critics challenged the statistical information on erosion, overstocking, and a number of other matters.

The extensive discussions in the 1934 meeting and the data collection in preparation for the Norris report seem to have galvanized internal Forest Service opinion in favor of action to further reduce stocking and improve the ranges. Total animal unit months (AUM's) grazed was about 3.2 million for the entire region in 1930, approximately the same level as 1927. Between 1930 and 1933, the number declined to 2.9 million. This likely was largely the result of non-use resulting from adverse market conditions: the numbers rose to about 3.3 million AUM's in 1934 as markets improved somewhat. There after, AUM's declined to about 2.7 million by 1938. [159] Reductions could be made more easily after 1935 because of the expiration of the first 10-year permits, with a new permit term beginning in 1936. [160]

A change in Forest Service policy in 1940 established regional responsibility for future reductions. In that year, the Service expanded the decentralization begun with the establishment of regions in 1908. Regional foresters were authorized to set their own livestock allowances without reference to the Washington Office. As Regional Forester C.N. Woods opined, this authority meant that "after 1940, there is no limit to the amount of reduction on established preferences we can make for protection." To capitalize on this opportunity, he called upon all forest supervisors to plan reductions to achieve the goal of proper stocking. [161] Supervisor I.M. Varner of the Caribou replied that "the protection program on the Caribou contemplates reaching proper use of each and every allotment through cooperative arrangements by the opening of the 1944 grazing season." [162] An inspection in October 1940 indicated that the expectation seemed realistic. [163]

Unfortunately, Varner was unable to implement the actual results of the studies made on his ranges. Regional office trainers showed rangers how to classify the watersheds which showed accelerated erosion into three classes according to degree of severity. [164] "Class I was light erosion: Class II, moderate: and Class III was severe. Erosion varied by forests, but in most cases involved only small isolated forest areas." After using techniques learned in the training, rangers sent their classifications to the supervisor's office, and the Caribou sent its combined report to the Regional Office. Since most of the forests in the region reported much less erosion than the Caribou, the Regional Office told Varner to move each classification up one level. According to James Jacobs, one of the participants in the study, the rangers nevertheless undertook substantial reductions on the Caribou and achieved good results.

Contemporary records indicate a rather mixed situation elsewhere in the region. An inspection of the Sawtooth in 1938 and Weiser in 1939 revealed some improving areas and others where overgrazing and improper trailing had allowed erosion. [165] When F.C. Koziol transferred to the Wasatch as supervisor in the mid-1940's, C.N. Woods told him he was going to a forest "where the grazing adjustments have been well carried out" and assured him that he would "have no overstocking problems." Koziol shortly found the situation was quite otherwise. [166]

Conditions in Nevada were of particular concern in the early 1930's because of the antagonistic attitude of State officials and the livestock association toward the Forest Service. The Nevada Land & Livestock Association worked to "prejudice grazing permittees against the Forest Service," and the movement continued to try to wrest control of grazing lands from the Service and transfer them to the State or the permittees. [167] After the passage of the Taylor Grazing Act, however, general sentiment tended to accept Forest Service regulation of the lands. [168]

The region's methods used in analyzing the condition and trend of the range during the 1930's changed only slightly from those developed earlier. The term "range survey" replaced "range reconnaissance" in about 1935. Procedures included the use of enclosures, palatability studies, and quadrats. [169] Some species plots were established in an attempt to determine the progress of plant depletion or improvement in critical areas. [170] Between 1932 and 1936 George Stewart and Selar S. Hutchings developed the point-observation-plot method of estimating vegetation density, which was adopted in 1937. [171] Some of their proposals derived from their work at the Desert Experimental Range, established by executive action in February 1933. [172]

Most important, perhaps, was the attempt during the late 1930's to improve forage-acre standards and palatability tables. The situation on the La Sal seems to have been typical. There, studies in 1938 and 1939 revealed that forage-acre requirements (FAR) and forage-acre allowances (FAA) varied considerably from allotment to allotment within the same forest. [173] By the late 1930's also, some forests like the Caribou realized that the palatability estimates made between 1929 and 1931 were too high and asked for their revision. [174] Research at the Intermountain Station published in 1939 indicated that utilization standards that had previously allowed forage cropping of 75 to 90 percent had to be reduced by 34 percent to bring about range improvement. [175]

Throughout the 1930's, Forest Service personnel worked with the available information and under the pressures at hand to accomplish some improvement of the ranges. To get the cooperation of stockmen, officers worked to help by allowing non-use, by agreeing to limit the reductions for distribution, and by considering distribution and protection reductions separately. [176]

With this sense of cooperation, trespass tended to decline in most areas, and both the Service and stockmen contributed to range improvements. [177] The Service continued to work on eradication of poisonous plants, construction of water developments and fences, and reseeding of ranges. [178] On the Dixie, for instance, experiments were tried (with indifferent success) in planting Kentucky bluegrass, smooth brome, and crested wheatgrass. [179] On some forests, such as the Caribou, Targhee and Nevada, water improvements were undertaken. [180] The Humboldt kept careful records of salting. [181]

Various methods were used to try to reduce stocking. The Fishlake and the Weiser and most other forests that relied on tagging had Service employees tag cattle because they found tagging by the permittees unsatisfactory. [182] Some forests, the Idaho, for example, reduced sheep breeding on the range. [183] On the Caribou, the Service established a system of individual allotment responsibility. Permittees agreed to take grazing cuts for improvement, and in return, the Service agreed to allow them to benefit from any capacity increases resulting from improved conditions, rather than distributing the increased capacity to new permittees. [184] On the Uinta, the rangers worked to reduce the length of grazing seasons. [185]

By the 1930's, allotment administration was generally more effective. Some supervisors, like Alexander McQueen on the Humboldt, resisted the development of individual allotment records and maps, but they seem to have been the exception. [186] Fishlake rangers expected reports from each permittee on actual use, including the number of animals grazed, length of season, weight of lambs on leaving the forest, number of losses, and reasons for losses. Each year the rangers furnished each permittee an allotment plan indicating the grazing rotation, a map of the allotment, and the general rules for grazing. [187] On the Caribou, allotment plans were rewritten to take the best available data into consideration. [188]

Timber Management

Comparable to the decline in grazing, a drop in timber cutting occurred in Region 4 during the 1930's because of depressed conditions. [189] In Region 4, the cut on national forest lands reached 69.9 million board feet in 1930, but did not get that high again until 1940. The low of 20 million board feet occurred in FY 1933 (table 9).

In part because of the lack of adequate markets and in part because of the fear of timber depletion, debate continued throughout the 1930's on the best means to achieve a balance between production and consumption. [190] During the late 1920's, battles had raged between the Service, which pressed for regulation, and the lumber industry, which feared Federal domination. [191] In 1930, President Hoover appointed a timber conservation board charged with developing a workable program of private and public effort. The board was deeply divided between those who favored Federal cooperation in sustained yield units consisting of national forest and private lands and those who wanted some sort of Federal control and regulation of private lands. [192]

Table 9—Quantity of National Forest timber cut under commercial and cost sales in Region 4, 1911-42 (in thousands of board feet)

| Year | Arizona | Idaho | Nevada | Utah | Wyoming | Total |

| 1911 | 183 | 18,707 | 2,539 | 12,468 | 3,137 | 37,035 |

| 1912 | 98 | 13,974 | 2,030 | 11,614 | 3,300 | 31,016 |

| 1913 | 329 | 13,311 | 3,122 | 11,396 | 4,043 | 32,201 |

| 1914 | S32 | 16,019 | 3,308 | 13,591 | 4,646 | 37,996 |

| 1915 | 399 | 17,678 | 2,803 | 24,850 | 3,032 | 48,762 |

| 1916 (FY) | 384 | 11,059 | 1,607 | 25,844 | 3,382 | 42,276 |

| 1917 (FY) | 395 | 8,415 | 1,391 | 16,869 | 1,546 | 28,616 |

| 1918 (FY) | 285 | 13,957 | 1,658 | 16,284 | 1,147 | 33,331 |

| 1919 (FY) | 225 | 12,935 | 1,565 | 14,674 | 1,807 | 31,206 |

| 1920 (FY) | 190 | 15,757 | 1,583 | 12,400 | 7,714 | 37,644 |

| 1921 (FY) | 263 | 18,448 | 1,232 | 11,368 | 12,959 | 44,270 |

| 1922 | 426 | 14,804 | 1,944 | 8,504 | 11,478 | 37,156 |

| 1923 | 468 | 26,093 | 1,711 | 7,658 | 10,648 | 46,578 |

| 1924 | 262 | 39,240 | 1,689 | 9,546 | 11,088 | 61,825 |

| 1925 | 140 | 51,338 | 1,667 | 7,154 | 15,289 | 75,588 |

| 1926 | 343 | 46,654 | 1,749 | 9,249 | 8,141 | 66,136 |

| 1927 | 373 | 40,435 | 1,142 | 6,192 | 2,628 | 50,770 |

| 1928 | 528 | 48,566 | 1,533 | 8,905 | 4,071 | 63,600 |

| 1929 | 597 | 42,465 | 1,080 | 11,056 | 9,324 | 64,522 |

| 1930 | 227 | 44,296 | 1,266 | 13,292 | 10,862 | 69,943 |

| 1931 | 54 | 23,007 | 995 | 8,130 | 4,492 | 36,678 |

| 1932 (Jan. to June) | 92 | 5,124 | 147 | 505 | 992 | 6,860 |

| 1933 (FY) | 47 | 12,424 | 631 | 5,296 | 1,592 | 19,990 |

| 1934 (FY) | * | 10,273 | 687 | 10,912 | 1,996 | 23,866 |

| 1935 (FY) | 21,143 | 660 | 14,242 | 1,471 | 37,516 | |

| 1936 (FY) | 24,222 | 807 | 13,776 | 14,135 | 52,940 | |

| 1937 (FY) | 31,466 | 800 | 10,977 | 7,571 | 50,814 | |

| 1938 (FY) | 37,861 | 958 | 11,556 | 8,885 | 59,260 | |

| 1939 (FY) | 37,689 | 1,319 | 11,715 | 10,361 | 61,084 | |

| 1940 (FY) | 48,292 | 795 | 15,300 | 6,207 | 70,594 | |

| 1941 (FY) | 38,627 | 589 | 17,809 | 4,871 | 61,896 | |

| 1942 (FY) | 69,706 | 522 | 21,605 | 5,079 | 96,912 | |

Source: Table TM—9 File: "Region Four statistics and Other Information, Part I, Historical Files, Regional Office. Cost sales would include those like S—22 sales at minimum prices. This would not include lumber given to farmers and others. *Kaibab National Forest transferred to Region 3 in 1933. | ||||||

As on the national level, the timber depletion theory governed analysis of conditions in southern Idaho. In 1938 a preliminary estimate showed 41,846 thousand board feet of timber (MFBM) in southern Idaho with an annual increment of 513 MMFBM. The Service estimated that 164 MMFBM were being cut each year (presumably on both public and private lands). At the same time, the Service argued that "there is a serious over-cutting that will probably cause the closing of the two largest operations within the next 10 years [by 1948] and reduce the present cut by two-thirds" (to 54,000 MFBM). Even though the estimated net increase in timber volume was thus 359,000 MFBM per year and the existing timber, with no new growth, could have lasted 255 years at the current rate of cutting, the Forest Service argued that "sustained yield for local use is not now possible except on a greatly reduced basis." The reason, it said, was the presence of "inferior species that have a very limited market and also inaccessible areas which cannot be economically logged." [193]

Most of this analysis reflected conditions on the Boise, Idaho, Payette, and Weiser National Forests and the private lands adjacent to them. Particularly important were ponderosa pine stands in the Boise Basin, Long Valley, Meadows Valley, and Council Valley. By the mid-1930's, the supply of accessible timber on many private lands had become exhausted. By 1935, for instance, private timber lands in the Boise Basin had become depleted and the Barber mill was abandoned and dismantled. Under these circumstances, the Service continued with its land-for-timber exchange program and in the late 1930's opened new areas of national forest timber through road construction in order to provide opportunities for mills to continue in business. [194]

|

| Figure 52—Ranger J.W. Farrell scaling logs at Brundage Mountain, August 1930. |

The regional office outlined objectives consistent with this point of view in a 1939 report. Objectives included, among other things, to keep forest lands productive, to "supply local [as opposed to export market] needs with local products;" to "maintain timber production on a sustained yield basis," which it said was possible only "for local use;" to consolidate forest holdings, through exchange or purchase to achieve sustained yield; and to determine "the most desirable ultimate ownership of all forest lands and the inauguration of a systematic acquisition program by the State and Federal Governments." [195]

In part, the perception of timber depletion derived from the state of logging technology, which by present standards was quite primitive. Only in the most accessible stands was logging economically viable. The usual methods of logging included horse logging, tractor logging, and donkey logging (with a donkey engine and cable). By far the most prevalent was horse logging; much of the intermountain forest was too steep and rough for tractor logging, and the timber was considered too small for donkey logging. In some cases where the land was too rough, hand logging was used. Timber was generally removed from the forest by railroad or river driving. [196]

|

| Figure 53—Hauling logs by horse, Ashley National Forest, August 1938. |

In spite of the depletion theory, in practice the region often paid more attention to keeping mills open than to potential stand diminution, Since the lumber business was so depressed during the 1930's, the Service acceded to the requests of the timber companies to engage in "high grading" or cutting only the choicest trees with butts of clear timber, especially in productive areas like the South Fork of the Payette River, then on the Old Payette, and on the Boise National Forest, Only the butt cuts without limbs were taken and the upper limby trunks were left to rot. [197] The Service was reluctant to open new areas, such as the South Fork of the Salmon River, for fear there would be no market for its timber or it would be costly and difficult to get out. [198]

The general practice—as opposed to the theoretical policy—was understandable, since lumbering was of extreme importance to the people of Idaho. Employing more than 12,000 people in 1929, lumber and other timber products ranked first among the manufacturing industries of Idaho in value of product and number of employees. [199] Lumbering and logging ranked second, and saw and planing mills ranked fourth among all industries in Idaho in 1930 in production of exports from the State and thus as a source of outside income. First and third were agriculture and lead and zinc mining. [200]

The most productive lumber businesses in southern Idaho were highly concentrated. In 1938, of 181 mills with an annual cut of about 164,000 MFBM, about 75 percent of the volume was cut by only two mills, largely for export. The other 179 mills produced small amounts for the local market. [201]

The only other extensive commercial lumbering was in the tie-hacking operations of the lodgepole pine belt of western Wyoming, northeastern Utah, and to a lesser extent extreme eastern Idaho.

|

| Figure 54—Loading ponderosa pine with Marion Loader, Boise-Payette Lumber Company, August 1930. |

In most of Utah, on the other hand, the lumbering tended to be almost exclusively for local markets. Estimates in 1940 fixed the State's total stand at 7.8 billion board feet of sawtimber and 7.4 million cords of wood, Most of the sawtimber (7.3 billion board feet) grew on national forest lands. On the average the Service sold 10,000 MFBM and gave away 20,000 MFBM of timber in free use each year. Since the Service estimated 80,000 MFBM could be cut in Utah on a sustained yield basis, the cut was only three-eighths of what could reasonably be harvested. [202]

In spite of the large volume of potentially harvestable timber, Utah continued to be a net importer of lumber during the 1930's. In the mid-30's, it produced only 12 percent of the timber it consumed and imported fully 75 percent from Oregon and Washington. The major reason for the absence of a viable local logging industry seems to have been the quality of the timber and the lack of technical knowledge of most operators, most of whom could produce only "native lumber"—usually unseasoned or poorly seasoned—for the local market. [203] As it was, most operations were very small. [204]

On some of Utah's national forests, the timber business was so small that management plans seemed superfluous. In 1939, for instance, neither the Dixie nor the Powell National Forests had written timber management plans and neither anticipated doing so. [205]

Still, the region tried to encourage both the continuation of old businesses and the expansion of new ones in Utah. The Western Wood Excelsior company of California, for instance, opened an excelsior operation in Cedar City in the 1930's to utilize quaking aspen. [206]

Under depressed conditions in the 1930's, both the region and the lumber operators had difficulty. Under Forest Service regulations, while the forest officers reappraised timber periodically, its selling price could not be reduced even if conditions worsened after the sale contract was signed. Thus, fewer companies were willing to bid on sales, and less timber was sold. Regional law officer Manly Thompson suggested that conditions might improve if timber sales were made for much shorter periods of 5 to 7 years rather than the 20 to 25 years then common. [207]

The cost of administering sales in less productive national forests in Region 4 was quite high. In FY 1931, the indirect administration cost in the LaSal forest of $3.03 per MFBM was higher than any other except the Lolo in Region 1. Indirect costs on the region's other forests (except the Lemhi) were generally in line with other regions except Regions 5 and 6, where the costs were lower. [208]

Still, the general integrating inspection made in 1940 found timber management practices in Region 4 to be quite realistic. Because many of the forests in the region, especially the Fishlake, Targhee, and Wasatch, conducted mostly small sales for local use, the inspectors approved the methods used to try to cut costs, particularly using sample tree measurements and cutters selection on small sales. The inspectors cautioned regional officials against overusing such practices, but complimented them for not trying to enforce practices generally suited to extensive timber stands in the relatively sparse and scattered intermountain timber. [209]

In spite of the minor role played by the lumber industry in Region 4 during this period as compared with Regions 5 and 6, regional officials were still concerned about proper management. In 1938, the region produced a revised timber management handbook designed to provide readily available information on policy and practices. [210]

|

| Figure 55—Railroad tie boom, Horse Creek near Daniel, WY, 1937. |

In addition, the region, in cooperation with the Intermountain Station, continued its experimental reforestation work. In 1932, the station tried to restore a burn in the Boise Basin by broadcasting ponderosa pine seed. Unfortunately, the experiment failed because birds ate the seed. In the early 1930's, the region planted 20,000 to 30,000 trees annually with volunteer labor—mostly in Utah. The region continued to monitor older plantations. [211] Research on sample plots in Idaho focused on logging techniques to promote maximum growth, natural restocking, and watershed protection; to improve immature stands by thinning and pruning; to reforest burned or denuded lands; and to protect against forest fires. [212]

In the mid-1930's, the region began to plant more extensively. In 1934, a cooperative planting was started on the Quartzburg burn in Idaho, and in 1935, the Boise Basin Branch Experimental Station planted about 10,000 seedlings on the Bannock Creek brush field, the Elk Creek burn, and the Quartzburg burn. [213] In 1936, the region opened the Tony Grove Nursery in Logan Canyon, designed to produce 2 million seedlings annually for use in Utah and Idaho. [214] In 1936, the Boise National Forest opened a small nursery on Bannock Creek. [215] By the early 1940's, a second major nursery had been opened at McCall, and despite some problems, it was expected to help significantly in supplying the region's needs. [216] Most stock planted in Region 4 during the 1930's, however, came from the Monument Nursery in Region 2. [217]