|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 10

Forest Planning and Management Under Pressure: 1970 to 1986

During the period from 1970 to the present, both the Forest Service in general and Region 4 in particular have survived extremely difficult times. Following the passage of the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act in 1960 the Service was involved in increasingly more complex planning in the attempt to manage the public resources under its jurisdiction so as to satisfy the public demand for commodities and services while protecting the land and resources for future generations.

Legislation passed during the 1970's radically changed the Service's relationship to the resources it manages. The laws passed between the enactment of the Organic Act of 1897 and the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act in 1960 were essentially permissive. Generally, these acts provided statutory authorization to do what the Service wanted to do or was already doing. Legislation like the Wilderness Act of 1964, the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970, the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974, and the National Forest Management Act of 1976, together with a number of court decisions, subjected the Service to a series of prescriptions that reduced its discretion in making resource management decisions. Such legislation, in addition, forced the Service to spend considerable time and energy in doing things it probably would not otherwise have done and doing them in ways that were inordinately disruptive of normal management practices.

These demands placed Forest Service employees in extremely difficult situations. As Reid Jackson, supervisor of the Bridger-Teton National Forest, said, it "is not as much fun as it used to be and I guess you can say that of about almost any Federal Agency position. I really think the Federal Agencies are becoming or have become 'whipping boys' for the politicians and for the environmentalists . . . . Still, there is a lot of pride in the outfit, . . . the outfit is pretty highly thought of. That is worth a lot to me and . . . to the others who work for the outfit." [1]

Administrative Problems and Budgetary Shortfalls

While the Service was subjected to increasingly disruptive demands, the pressure to carry on normal functions related to range, watershed, timber, minerals, recreation, wildlife, special uses, and wilderness intensified. This pressure led both line and staff officers—but most particularly line officers—to practice what Manti-LaSal Supervisor Reed Christensen called "selective neglect." That is, since they could not do everything to an equally high standard, they "tried to put [our] licks where they bought [us] the most." [2]

This meant that rangers would spend increasingly less time in the field and in contact with forest patrons and increasingly more time in the office. As Foyer Olsen put it in 1984, "the district ranger's job had changed to the point where he is primarily an administrative officer . . . . I've heard a lot of [people] . . . comment, 'We never see a ranger any more.'" [3] A recent study by the Forest Service's National Communications Task Force found a perception among commodity groups, environmentalists, and the general public that line officers should be involved more in "informal day-to-day contacts." [4]

In order to try to deal with cost-effective management, in 1984 Chief Forester R. Max Peterson appointed the National Business Management Study team. Caribou Forest Supervisor Charles Hendricks, a member of the team, said that the buildup necessitated by the increasing demands on forest officers' time had created substantial unnecessary costs. Consequently, the Service had to figure ways of doing "business cheaper than we have in the past," which would "probably" mean "some sacrifice of quality," and "taking a few risks that we have said we aren't willing to take," especially in internal management programs such as writing manuals and coordinating personnel relations. [5]

The Forest Service used other strategies to try to deal with the problems of increasing demands. One was through the use of the budgetary process to control the types of activities carried on. Each forest was given a foundation-level budget, which was not enough to operate on. Each forest then bid on additional funding for projects it wanted to do. The regional office and Washington Office made decisions on allocating increments of funding for various projects, to the degree congressional legislation gave them the discretion. [6] Contrary to previous Forest Service tradition, decision-making authority was considerably more centralized. Unfortunately, Congress was generally quite willing to provide funding for projects with tangible results, such as timber and grazing, but reluctant to fund adequately the intangibles such as recreation and watershed protection.

In addition, the region faced periodic budgetary reductions that resulted in staff shortages. The two most serious reductions were in the early 1970's during the latter part of the Nixon administration and in the period after the inauguration of the Reagan administration in 1981. During both periods, the crunch was accompanied by personnel reductions. [7]

The Reagan cutbacks had essentially three results. First, Forest Service officers were forced to learn "to do things a lot more efficiently." [8] Second, as one respondent indicated, "When you start playing with people's lives and money and livelihood, it does cause morale problems." For example, managers, reluctant to force employees with critical family responsibilities out of the Service, often applied subtle pressure on older employees to take early retirement. [9]

|

| Figure 97—Targhee National Forest management team studies ways of improving efficiency. |

Third, forest users were forced to accept lower levels of service or provide their own services. Between 1979 and 1984, for instance, the Fishlake National Forest's budget was reduced by 60 percent. This resulted in a 20-percent reduction in employees, and more significantly, on a forest with a large range work load like the Fishlake, the permittees were forced increasingly to pay a larger part of range improvement costs through cooperative projects. [10] Similar reductions took place on other forests, for example, the Targhee. [11] In the regional office, various functions were reduced as well. Sterling J. Wilcox, engineering staff director, indicated that the major problem was the reluctance to fund "programs that have long range returns," in preference to those with immediately visible outcomes. [12]

One response of the region to this budgetary pressure was to create zone positions and shared services. [13] The Uinta, Manti-LaSal, and Fishlake, for instance, shared a specialist to install the Data General MV/Series computer system that was designed to tie the forests and the regional office together in a computer network. [14] The Dixie, Manti-LaSal, and Fishlake shared contracting services. [15] The Uinta had several zone offices that provided service to other forests on such functions as watershed, timber inventory, and threatened and endangered plants. [16]

Another tactic for reducing costs was the even more extensive use of contracts rather than force account labor. Although the region tried to avoid contracting for jobs involving direct dealings with the public, it often did so for services for internal operations. Thus, since a district ranger had to represent the Forest Service and to interact with the public, the forests did not ordinarily contract for those responsibilities. [17] Instead, the forest would contract for construction, food services, reforestation, electrical work, and aircraft. [18]

Under these conditions, the region reemphasized the need both for training and for cooperative interaction to help personnel understand how to do their jobs more effectively and efficiently. In November 1979, Regional Forester Vern Hamre inaugurated a "Management Effectiveness for the 80's" (ME 80's) program designed to train rangers in such things as handling conflicts, using computers, and dealing with environmental pressures. "Based on the concept that changing the culture of an organization rather than concentrating on technological or structural change is the best way to encourage efficiency and effectiveness," ME 80's began at a workshop held for district rangers at Snowbird UT, and continued with two other regional workshops. [19]

When the region introduced new or particularly sensitive technology such as prescribed burning or the Data General system it mandated extensive training and certification of personnel. [20] The pressure for change also brought about the introduction of a management-by-objectives program that coordinated individuals' work and performance with the region's goals and objectives. [21]

One of the most creative methods of coping with change was the introduction in the early 1980's of the Delta Team. The term "Delta" derived from the three sides of the Greek letter Delta and represented: Anticipate, Excellence, and Action. Under the system, the region established special ad hoc teams consisting of regional office and national forest personnel to analyze and propose solutions to problems such as information management, education, civil rights, budgetary reduction, and future direction. A report by Deputy Regional Forester Tom Roederer in March 1986 indicated the effectiveness of the teams in dealing with change. [22]

Unit Consolidation

The budgetary pressure accelerated the consolidation of forests and ranger districts into units of optimum size that had begun during the 1960's. In Region 4, this ordinarily meant larger sizes. After his appointment as regional forester in 1970, Vern Hamre continued the studies of ranger district and national forest size and made changes both in number and boundaries of ranger districts in the various forests and in the number and boundaries of forests in the region. [23]

Though ranger district consolidations continued into the 1980's, most of the consolidations were undertaken between 1970 and 1973. Some ranger districts were combined as in the Dubois and Spencer and the Ashton and Porcupine on the Targhee. [24] In some cases, as in the Vernon unit on the Wasatch, portions of ranger districts were administratively reassigned to other national forests. [25] The number of ranger districts in the region was reduced from 120 in 1971 to 94 in 1973 and to 77 by 1983. [26] At the 1986 Ranger's Conference Regional Forester J.S. "Stan" Tixier announced that the region had been "advised we have gone as far as we should go in Ranger District consolidation." [27]

Most significant, perhaps, were the forest consolidations, also undertaken because of budgetary constraints and in the interest of efficiency. Following a study of conditions, the regional office consolidated the Cache and Wasatch National Forests early in 1973, assigning the former Cache districts north of the Idaho-Utah border to the Caribou. Headquarters for the Wasatch-Cache were located at Salt Lake City, and the former Cache headquarters at Logan became a ranger district office. At the same time the region assigned the Palisades Reservoir portion of the Caribou to the Targhee, perhaps to compensate for the expanded responsibilities at Pocatello. [28]

The region studied the possible consolidations of the Toiyabe and Humboldt and of the Bridger and Teton. [29] The first was not undertaken. In 1973, however, the Bridger and Teton were combined, with the supervisor's office at Jackson. The Kemmerer headquarters of the Bridger became a ranger district office. [30] Consolidation of the Bridger and Teton created a 3.4 million acre national forest—by far the largest in the lower 48 States, exceeded only by the Tongass and Chugach in Alaska. Although its budget of $6 million in 1983 exceeded that of the nearby Grand Teton National Park, some Forest Service officers believed that the demands created by its much larger size and more diverse resources left it shortchanged. [31]

Portions of some forests not affected by such consolidations were transferred for administrative purposes to adjacent forests or regions. In central Idaho, for instance, creation of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area placed parts of three national forests under Sawtooth administration. The Middle Fork of the Salmon River, because of its unified recreational program, was transferred for administrative purposes to the Challis. The Region 4 portions of the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area and the Tahoe Basin were administered respectively by Regions 6 and 5. [32]

Proposed Regional Changes

A number of proposals surfaced after 1970 that would have altered significantly the configuration of Region 4 or abolished it entirely. In 1972 the Nixon administration's Office of Management and Budget proposed a concept that would have abolished the regional office in Ogden, transferring Nevada to the San Francisco region, Idaho to Portland, and Utah and Wyoming to Denver. In addition, contrary to Forest Service tradition, the administrator in each standard region would have been a political appointee rather than a career professional. The proposal would have reduced services to forest users in the region by cutting down the number of employees. Although he could not officially oppose the transfer, Regional Forester Vern Hamre worked with the Utah congressional delegation, especially Congressman Gunn McKay and Senator Frank Moss. Former Regional Forester Floyd Iverson took an active role in opposing the change and was sent to Washington to work against the proposal. McKay and Moss together with Senators Mike Mansfield and Lee Metcalf of Montana and Joseph Montoya of New Mexico succeeded in attaching an amendment to an appropriation bill prohibiting the use of any Federal money to close the regional offices in Ogden, Missoula, and Albuquerque. [33]

The most recent proposal to try to save money by consolidating land management services involved a nationwide interchange of various national forest and Bureau of Land Management lands. Revealed first on January 30, 1985, and elaborated in public meetings during the summer, the interchange proposal would have left virtually the same number of acres in Region 4 in Utah, increased Forest Service acreage by about 2 million in Idaho, decreased the acreage by about 175,000 acres in Wyoming, and completely eliminated Region 4 from Nevada. [34] Lobbying by the Nevada congressional delegation and others succeeded in modifying the proposal to keep the Forest Service in the Silver State.

In its present form the interchange proposal would actually add more land to the national forests in Region 4. Advantages touted for the proposal include the transfer of control of the mineral estate under national forest lands to Forest Service administration and the transfer to the Forest Service of the heavily timbered Oregon and California Railroad Lands that reverted to the Federal Government after the railroad failed to fulfill its land grant agreement. The main selling point, however, was the approximately $12 million to $15 million savings expected, largely by reduction in personnel and other administrative costs. The interchange proposal received administrative approval and was transmitted to Congress for consideration early in 1986. [35]

If the 1985 hearings in Salt Lake City are any indication the proposal will undoubtedly have rough sledding in Congress. Utah Congressman James V. Hansen's office manager testified that the congressman had reservations about the proposal. Representatives of the Utah Farm Bureau Federation took a somewhat equivocal stand. Virtually everyone else in Utah opposed the proposal, including those from the environmental community, commodity interests, and former Forest Service officers. Provo interests expressed considerable opposition because the Uinta National Forest headquarters would be closed and the lands consolidated with the Wasatch, Manti-LaSal, and Ashley. [36]

A 1985 study conducted by Region 5 showed considerable opposition throughout the Intermountain Region and elsewhere in the West. In Idaho, opposition had grown to the transfer of portions of the Caribou and Sawtooth to the Bureau of Land Management; Nevada respondents indicated heavy opposition to transfer of Forest Service land. Former Nevada Governor Mike O'Callaghan writing in the Las Vegas Sun charged Chief Peterson with "selling out his agency and every outdoors lover" to BLM Director Robert Burford. In Utah, considerable opposition arose over the proposed transfer of Pine Valley to the Bureau of Land Management and the proposed closing of the Dixie supervisor's office. In Wyoming, opposition surfaced to the proposed transfer of parts of the Bridger. [37]

Another controversial proposal closely tied to the interchange was the creation of a department of natural resources, reminiscent of Harold Ickes's abortive proposal for a conservation department in the 1930's. The Forest Service and its constituents opposed the concept, which surfaced anew during the Carter administration and as an option in the Grace Commission Report. In general, the opposition came because of a fear that the philosophy of the new department might mirror the more centralized operation of the Department of the Interior rather than the decentralization of the Forest Service as supported by the Department of Agriculture. [38] In part, Chief Peterson's support for the interchange proposal came because of his concern that such a reorganization might be forthcoming if interchange failed, as a result of the administration's heavy pressure to save money. [39]

Organizational Changes

One major organizational change took place in 1973 that significantly altered the makeup of the regional office staff. For many years, the regional forester had functioned with a single deputy sharing his responsibilities, along with a number of assistant regional foresters carrying both line and staff responsibility. The new organization better differentiated between line and staff. Under the new setup, the regional forester appointed three deputy regional foresters. One had line responsibility for administration, one for resources, and one for State and private forestry. Each had concurrent staff responsibilities to the regional forester. [40] Under the deputies' jurisdictions, directors headed the various staffs such as timber, range management, and personnel. [41] Vern Hamre indicated that this change facilitated a great deal more cooperation in the allocation of resources than the previous assistant regional forester system. [42] Some former regional foresters, for example, William Hurst, disagreed. Hurst believed that the assistant regional forester system was more efficient and cost-effective because it had fewer officers between the regional forester and the principal staffs. [43]

Employment Patterns and Regional Administration

Major organizational changes in recent years continued to refine the use of the interdisciplinary team. After 1980, members of the teams tended to work together to produce compromises much more effectively than before. After a decision was made, specialists became more prone than in the past to say, in effect, "I do not like the decision but my job is to do the best I can to help them implement it." Under these conditions, specialists tended to recognize themselves as team members working within a multiple-use management system rather than diehard devotees of a particular professional interest. [44] Some specialists, however, have resigned in protest over decisions with which they did not agree. [45]

During the period after 1970, the emphasis on employee rights increased. In 1970, the Washington Office appointed a civil rights coordinator to oversee efforts to improve programs for minority groups, conduct civil rights compliance reviews, and promote the awarding of contracts to minority businesses. [46] Forests wrote and implemented affirmative action plans. [47] In his monthly message in August 1984, Regional Forester Tixier emphasized his commitment to civil rights and urged an emphasis on representing all the people and making services available "to the entire population." [48]

The region also has expended considerable effort in hiring and training women employees. In 1979, for instance, the Sawtooth National Forest set its goal to hire females as 33 percent of its seasonal workforce, a 7-percent increase over 1978. [49] By 1984, most women were in clerical, secretarial, intermediate, and specialist positions. In 1984, a visitor to the forest supervisor's and ranger district offices would most likely find women who were not in secretarial or clerical appointments either in specialist or support services positions rather than staff director or line officer positions. [50]

It is clear, however, that the region's commitment to equal employment opportunities for women and minorities continued under Tixier. At the district rangers conference in Boise in March 1986, one of the sessions focused on women and minorities in the Forest Service. The panel was made up of women who were currently serving as district rangers in other regions. At the same conference, the moderator for one of the sessions was Carol Lyle, Region 4's sole woman ranger. [51]

A major factor militating against the employment of women and minority employees has been the reduction in budgets after 1980. This reduction has meant that few new jobs have opened and the region has been hard pressed to replace existing employees who retire or resign. [52] During the Carter administration from 1977 through 1980, the region could retain employees and plan for new hires. Under the Reagan administration, however, the size of the staffs has decreased. [53] Between 1980 and 1982, the number of employees in the region declined from 2,467 to 2,307. As the average age of employees increased, the average GS grade rose from 8.17 to 8.46. [54]

The result was a void of younger employees with new skills. [55] This created a particularly serious problem in engineering. [56] By 1984, the region had very few engineers in GS grades 7 and 8—those in their late 20's and early 30's. The average age of engineers in Region 4 was 40 to 45 years. After the 1970's, the need to recruit specialists such as hydrologists, archeologists, and wildlife biologists placed most of the younger employees in those categories, not in the ranks of the engineers. Increasingly, also, the engineering staff experienced difficulty in finding desirable people. Generally the engineering division sought the broadly trained student who liked the outdoors and could integrate information from a large number of specialties in designing roads and structures to meet the demands of resource protection, rather than the narrowly trained graduate who might have a particular research specialty.

Another problem was finding employees willing to meet the demands for mobility the Forest Service expected of those who planned to advance. Continued emphasis on multiregion and Washington Office experience for promotions within the Service placed a burden on families and on budgets. In some cases, for instance, engineering was unable to hire desired employees because of the region's inability to pay enough to get the potential employee to make a move. As a result, in some cases, they hired engineers with promise, but with less training than preferred. [57]

Some employees still believed the frequent moves to be an advantage rather than a drawback to a family. David Blackner, director of the regional personnel management staff, said that the system of reimbursement for moving expenses and subsistence while relocating has helped. In addition, he argued that moving around could be an advantage to children, broadening their experiences. Some employees disagree, believing it is important for their children to experience continuity in their schooling and peer relations. [58]

In a presentation to rangers in March 1986, Blackner announced that a program to be implemented in mid-summer 1986 would allow General Services Administration to purchase the homes of transferred employees. This program was not expected to be a panacea, however, as the housing market had been depressed in recent years in some areas and the homes are to be purchased at fair market value. Since employees might have purchased the homes when prices were high, they may not recover their outlay in the sale.

With increased emphasis on fairness in employment, the Forest Service adopted a new vacancy filling and promotion system in the mid-1970's. [59] Before that time, vacancies were filled and promotions given based on evaluations and recommendations by supervisors rather than on employee initiative. On the basis of such recommendations, a review committee recommended to the line officer the nominee they thought best qualified. This system left a great deal of administrative discretion in the promotion process.

The new system differed by advertising vacant positions to all employees. All interested employees were encouraged to apply, though they had to submit an evaluation from their immediate supervisors. All applicants were then screened and evaluated by a committee in the regional personnel office, and, from that screening, the person was hired who seemed best qualified for the job. A superior could direct an employee to apply if it appeared the person needed the job for development or was qualified for it.

Although fairer, since it allowed employees to select themselves for consideration for vacancies and promotions rather than forcing them to wait for a manager to choose them, the system had some drawbacks for supervisors. Some employees, particularly those with scarce skills such as hydrologists, "job-hopped" from region to region and forest to forest. Some employees moved from one position to another without the forest supervisor even knowing they had applied for a transfer. These quick changes created problems as the consequently vacant positions often had to be filled on short notice.

Law Enforcement

Along with those problems, the region was faced with increasingly complex circumstances. Largely because of urban development in the areas adjacent to many of the forests in the region and the increased recreational interest in all forests, law enforcement problems intensified. Forest Service law enforcement officers linked their communications into local and State law enforcement nets. On an urban forest such as the Uinta, forest officers discovered marijuana plantations, faced cult practices, and dealt with motorcycle gangs. [60] A theft ring operated to cut and sell Christmas trees from the Fishlake National Forest. [61] Increasingly, the region sent employees who had to deal with such problems to the National Law Enforcement Training Center at Glynco Beach, GA, for a 9-week course used to train Border Patrol and Drug Enforcement agents. [62] By 1984, the region had six special agents with the full range of authority held by officers such as FBI agents except that the Forest Service agents helped to enforce the Secretary's regulations dealing with such matters as timber theft, arson, and illegal occupancy. [63]

The Problem of Conflict Resolution

After 1970, Congress forced the national forests to draw further away from some formal contacts with forest users. Even though (as indicated before) advisory committees had generally been used to support decisions already made by the Forest Service, such committees also had served to coordinate the interests of the Service with local communities. In December 1972, however, Congress passed the Federal Advisory Committee Act, which restricted the use of such advisory committees. Following the act's passage, an executive order required the abolition of the forest advisory committees. [64]

In practice, the abolition of these advisory committees had some disadvantages. The older constituencies of the Forest Service—city, county, and State officials; community, business, and professional leaders; and commodity interests—no longer represented even a sizable minority of forest users. [65] The growth of the environmental movement and the tendency for the environmentalists to represent constituencies at a considerable distance from the forests as well as nearby recreationists left a gap in conflict resolution procedures that a somewhat modified advisory committee structure might have filled. [66]

As a case in point, the National Task Force on Public Communications/Awareness (often called the Tixier Committee) headed by Regional Forester Tixier, identified a significant division in the attitudes of environmental and commodity interests. In general, non-commodity interests believed that the Service had placed a "growing emphasis on timber and other commodity resource production without a commensurate emphasis on noncommodity resources," and that this imbalance in emphasis was an extremely serious problem. Commodity interests did not agree. The noncommodity interests placed little emphasis on the philosophy of multiple use and sustained yield, whereas the commodity interests tended to think these concepts were important. [67] Some commodity interests and their allies tended to use the phrase "multiple use" as a code word for opposition to wilderness areas, arguing unfairly that environmentalists sought to eliminate everything but wilderness from national forests. [68]

Unfortunately, an erroneous perception of many environmentalists that Forest Service officials principally favor commodity production resulted in a number of confrontations between the environmental community and the Service. A good indication of this type of confrontation was an exchange in 1984 between Ed Marsden, editor of the High Country News, and Vern Hamre, former regional forester. In March, Marsden published an editorial entitled "Can the Forest Service Be Reformed?" arguing that the Forest Service refused to listen to environmentalists, that it had increased its office staff at the expense of field staff who really managed the land, and that it had accomplished very little of consequence. [69] Hamre's reply outlined a number of the Service's significant accomplishments, pointed out that the increase in the Service's bureaucracy had come largely because of the time demanded for responses to appeals, and asked for help from environmentalists rather than confrontation. Marsden had written that he would "reserve space for [discussion of these charges] . . . in the next couple of issues." He did so, but not until October 1984, some 7 months after the editorial. [70]

In 1984, James Lyons, resource policy director of the Society of American Foresters, expressed considerable opposition to what he perceived to be the Reagan administration's overemphasis on commodity management and production at the expense of recreation, wildlife, and watershed conservation values. [71]

Attitudes like those of Marsden and Lyons caused deep divisions within the Service and between the Service and its constituencies. This dissatisfaction both among constituents and within the Service created some anxiety for Regional Forester Tixier. He indicated particular frustration with the expressed perception of some environmentalists that coming in to talk with Forest Service officials "would be futile." [72]

This concern led in part to Tixier's appointment as chairman of the National Communications/Awareness Task Force, designed to determine the public perception of the Forest Service and to propose means of dealing with problems of negative perception. Regional foresters and directors discussed the Tixier Committee report at their annual meeting in Fort Collins, CO. in August 1985. The Service took the unprecedented step of holding a conference to discuss the same issues with forest supervisors from throughout the Nation at Utah's Snowbird resort in November 1985. The result of these deliberations was a decision to prepare a "vision statement" redefining the purposes of the Forest Service. [73]

Most significant, it was believed that the recommendations of the Tixier Committee could help in solving both problems of internal dissatisfaction and public opposition. Among the recommendations that seemed most critical were those calling for reduced paper work and increased time in the field for district rangers to get them back in touch with the public. Another suggestion that seemed likely to produce significant results consisted of enlisting "the service of a neutral third party conservation organization," such as the American Forestry Association or Resources for the Future, "to focus debate on the 'balanced program' issue" with a goal of "involving commodity and noncommodity interests, as well as other interested publics, in a meaningful dialog aimed at consensus." In addition, the Tixier Committee recommended strengthening "working relationships with conservation organizations, interpretive associations, and other public service oriented groups who have an interest in National Forest programs." [74]

Information Office

The abolition of advisory committees, the deep divisions within the region's constituencies, and the inability of line officers to spend adequate time in contact with the public placed a great deal more pressure on the regional information office than ever before. In 1972, in recognition of the increasing importance of the function, the information offices at both the regional and Washington levels were assigned directly to the regional foresters and the Chief. [75]

The information office had a number of functions, of which four seem most significant. First, it dealt with the news media in channeling information to the public. Second, it conducted an environmental education program in which it worked with educators on the community and State levels to encourage them to include environmental programs in their classes. Third, it coordinated with legislatures in the region on both State and Federal matters. Fourth, the office conducted an extensive interpretive services program, servicing visitor centers and providing displays and audiovisual information. [76]

In view of the legislative mandate to involve the public in decisionmaking, the region and the forests developed an "Inform and Involve" (I and I) program in the early 1970's. Under this program, information officers functioned at the regional level and either an information officer or an I and I coordinator operated on each forest. The Wasatch, Toiyabe, Boise, and Bridger-Teton forests each had a public information officer. [77]

The approach to the dissemination of information changed considerably during the early 1980's. In the early 1970's, the information office worked principally with key community leaders—congressmen, governors, and business and industrial leaders. By the late 1970's, because of the changing nature of the publics with which the Service had to deal and because of the emergence of groups that did not respond to the traditional political structure, it became necessary to open the information office to a larger public. [78] The HOST program initiated by the information office tried to involve all Service employees in public awareness. [79]

Legislative Mandates and Planning

Confrontations resulted, in part, from the application of various pieces of congressional legislation. In practice, such legislation required the Service to meet certain minimum procedural standards before it could undertake any substantial activity. Since its beginning, the Forest Service had written plans for its various operations, and even before the passage of the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, forest officers had been producing multiple-use surveys and management plans. By the early 1970's, the forests were writing unit plans, under regional guidelines, that divided planning units into blocks extending downward from the ranger district. [80] The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) imposed a further procedural requirement on the Service. After 1970, the Service was obliged to write environmental impact statements on all projects that required serious changes in the environment or might be controversial. On less controversial or minor projects, the line manager had to document the basis of the decision. [81]

Over time, the way in which the Service used the environmental assessment changed. According to Richard K. "Mike" Griswold, former director of the regional planning staff, the Service changed slowly, like a crew trying to turn a battleship with a canoe paddle. In his view, it took 3 or 4 years to "get around to the point" where forest officers complied with the NEPA process. The basic reason for the timelag was the extensive decentralization within the Service.

After the forest officers learned the NEPA system, until about 1980, the process seemed to work quite well. Then, around 1980, the Service found it had come to let NEPA dominate planning to such a degree that, when various interests challenged procedures, the courts ceased to recognize Forest Service employees as expert witnesses. The courts insisted, instead, that representatives of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ) or the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) appear as experts.

In order to achieve more control in such situations, the Service separated its NEPA environmental assessment (which documented the thought process) from its management plans (which indicated intended actions). Under those conditions, CEQ or EPA representatives might be the expert witnesses in court on the environmental assessment—the analysis that led to a decision—but Forest Service personnel were the expert witnesses on the management plans. [82]

Nevertheless, by 1984, the region had not done well in defending itself against appeals under NEPA. In general, the reason was that the region had not followed carefully the steps outlined by the act. In one case, the region decided to build a timber access road on one of the forests. In preparing the environmental assessment, the Service officers considered only the impact of the roadbed itself, not the effect of the road and timber harvest on the entire basin. It was, said Griswold, not malicious or preconceived, but "just a process goof." Fortunately that case did not go to court, a procedure the Service disliked because it was very expensive and could result in a decision extending far beyond the point at issue. The region would then be stuck with "new [judge-made] law," that could tie its hands. [83]

In practice, while forest officers griped about the NEPA, they generally supported it. The process often added additional costs because of the care with which plans had to be made, but resulted in a better product. [84] It was nevertheless extremely frustrating for Forest Service officers to face frequent challenges to their plans. Many believed that "for a twenty-cent stamp, [critics] . . . could stop just about anything." The level of frustration often rose because the various interests did not agree with one another and what pleased one side might well generate an appeal from an opposing faction. [85]

In 1974, Congress followed the NEPA with the passage of the National Resources Planning Act. This act required a nationwide assessment of all forest and range land each 10 years and development of a Forest Service management program each 5 years. As of early 1985, the region had been through two assessment and two program cycles. It made assessments in 1975 and 1980, since it wanted to put the assessments on decade anniversaries. In practice, Griswold argued the procedure was good for the Forest Service. In his view the unit plans were too fragmented, because they were based on ranger districts. [86]

This legislative action took place against the background of national appeals concerning forest management in West Virginia and Montana in the Monongahela and Bitterroot National Forests. Both cases involved timber management policy and especially clearcutting. The decision in the Monongahela case particularly invalidated the prevailing interpretation of harvesting provisions of the Organic Act of 1897. This decision forced Congress both to redefine the Forest Service's mandate and to require more detailed planning. The Bitterroot case raised serious questions about harvesting practices. [87] The resulting National Forest Management Act (NFMA) of 1976 placed major emphasis on the development of land management plans for each national forest detailing alternatives and proposals for the management of each type of resource under multiple-use management principles. It also provided for a committee of scientists to provide policy direction. In addition, the NFMA specifically overturned the Monongahela decision by allowing carefully controlled clearcutting. [88]

The process under the NFMA presented two basic problems to the Service, one concrete and one potential. On the concrete level, NFMA planning "really put pressure on the forest" since employees had to expend considerable time, labor, and resources in writing plans. Consequently, forest officers also found it considerably more difficult "to do a quality job of our routine work out on the ground." [89] Ed Marsden's complaint that employees were pulled from the field into the office was exactly right. A major reason for this shift was the demand for planning and for meeting procedural requirements in carrying out mandated activities.

The potential problem was that associated with any planning. Since the planners had to project from what they knew about the current situation, none could anticipate every contingency. "The law says that when you have an approved forest plan, all licenses, permits, practices, and activities that occur on that national forest henceforth will be in accordance with that plan." [90] Some specialists in environmental policy such as Sally Fairfax of the University of California at Berkeley reportedly said that no land management agency could possibly accomplish what the law demanded of the Forest Service. [91] Though the Service wanted to prove her wrong, part of the possibility of doing that was in fact out of its hands, since virtually anyone could demonstrate legal standing in order to file an appeal.

The entire planning process was strewn with roadblocks. A major obstacle appeared during the second review of roadless areas (RARE II). In the case of California vs. Block, the U.S. Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that the RARE II final environmental assessment was insufficient to base a decision for non-wilderness designation of roadless areas. As a result, the roadless area review was incorporated into the land management planning process and the forests were forced to go back to the drawing boards. [92] By then, the Targhee and Uinta had circulated draft forest plans to the public. The Caribou had sent its plan to the Washington Office for review and had been given approval to circulate the plan to the public. Under the circumstances, the three forests did not have to junk everything they had done, but they were forced to redo much of the previous work. [93] The Toiyabe estimated that the cost of including the reassessment of roadless areas in the land management plan added an additional $150,000 to $200,000 to the already staggering cost. [94]

Though it allowed discretion in management within multiple-use principles, the NFMA created what former regional forester Vern Hamre called "a real nightmare." By late 1984, although the region's forests had completed the drafting of a number of plans, none had been approved. Hamre believed that it would be "almost impossible to complete a forest management plan on a forest which has any significant environmental controversies." [95] The region drafted a plan—later called a "regional guide"—designed as a directive to the forests in the planning process. [96]

As might be expected, the supervisors most sanguine about planning were those who had completed or nearly completed their plans. Don Nebeker, supervisor of the Uinta National Forest, spoke with some justifiable pride about the fact that his forest was the first in the region to complete its plan. [97] The regional office placed the Fishlake National Forest's plan on a fast track, but it faced considerable difficulty because of reductions in staff between 1981 and 1984. Nevertheless Supervisor Kent Taylor expected to complete his plan on schedule. [98] Supervisor Jack Lavin on the Boise believed that his planner would make few drastic recommendations from the previously completed unit plans and RARE II proposals, but by early 1984 he thought it was still too soon to tell for sure. [99] Supervisor Art Carroll of the Wasatch-Cache recognized that the public might find his plan controversial and expressed concern that virtually anyone might qualify for the administrative appeal process. [100]

Diversity within the region created both problems and advantages for planning. Few forests in the system are as heavily used for recreation as those along the Wasatch Front; the region has mineral and range management loads second to none; concerns about scenic attractions and wildlife are particularly sensitive in western Wyoming and eastern Idaho. [101] But because the forests of the Intermountain Region are not as heavily timbered as those in Region 1 or Region 6, the region did not have as much money for planning. [102]

Because of the larger recreation load, however, the environmental interests have been easier to work with. Utah's wilderness bill, for instance, was the first in Region 4 to pass Congress. In addition, the region's national forests were very careful to involve the public in the decision process by holding public meetings with various groups and private meetings with particular interested parties. [103]

In spite of the obvious technical aspects, planning became in the final analysis a political process. The administration in Washington set policy for the Service, and changes in political philosophy made changes in planning and implementation of plans both imperative and disruptive. In the view of John Burns, the Reagan administration turned "almost a hundred and eighty degrees" from the direction of the Carter years. The situation was complicated since political pressure cut in a number of directions. Congress decided how much money the forests got for the various activities. Decisions on the amount of wilderness and timber harvesting were by their very nature political, as various interest groups inevitably wanted different mixes of these activities. [104] Hence, Forest Service officers were not free to implement all the proposals they might have preferred.

Basically, the forests tried to respond to the political realities through the four phases of each plan. Phase 1 consisted of issue identification, phase 2 was an analysis of the management situation, phase 3 involved the development and assessment of alternatives, and in phase 4 the forest officers selected the final plan. Extensive opportunities were provided in each phase for input through public meetings and comment. [105] In connection with the planning, the forests wrote draft environmental impact statements indicating the potential consequences of the various planning alternatives together with the preferred choices. [106] The final product was a draft forest plan that reviewed the various mixes of resource uses and proposed the preferred alternative. [107]

The public response to the plans has varied from support to virtually no comment to adverse comment. Joseph Bauman, Deseret News environmental specialist, commenting on the 11-pound Wasatch-Cache National Forest plan that emphasized recreation, reviewed the proposed alternative favorably. He pointed out, however, that "all the plan's activities will be controlled by budgetary considerations. If budgets are cut, some projects may be rescheduled." [108] Idaho Governor John Evans, however, in responding to the Challis National Forest plan, urged that the forest emphasize recreation rather than commodity use to a greater degree. [109]

By March 1986, the region had reason to be more optimistic than Vern Hamre was in 1984. Four of its plans were in final form, and ten had been issued in draft. Of seven appeals, four had been resolved. Both the Uinta and Wasatch-Cache plans had been cleared. In commenting on the land management planning process, Chief Peterson said that he would give the region an A+ for effort, a D for speed, and a B for overall quality. [110]

Recreation

After 1970, recreation within the entire national forest system took on greater importance. Traditionally, the national forests have experienced far more recreation visitor-days than the national parks. In 1970, recreation stood third behind timber and grazing as a principal revenue producer in Region 4. By 1983 it had moved into first place, eclipsing all other functions, a position it retained through 1985. [111] (See table 19.)

It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of recreation to the forests of Region 4. Recreation encompassed a great range of activities including water sports, camping, picnicking, sightseeing, hiking, skiing, hunting, fishing, rockhounding, and snowmobiling. Management of cultural resources also fell under recreation's domain. In 1984, the region had 783 campgrounds and picnic sites capable of accommodating 79,000 people at a time. The region supported 8.6 million to 9 million visitor-days per year during the early 1980's. [112]

The Wasatch Front in Utah and the Sierra Front in Nevada and California experienced the greatest recreation pressure. Pressure on the Wasatch was much the more intense because of the larger population in the Logan-Provo corridor than the Reno-Carson City area. [113] Until the early 1980's, the Wasatch National Forest was the number one recreation forest (based on visitor-days) in the entire system. By 1984, it had dropped to fourth or fifth behind several forests in California. [114] Some forests such as the Uinta were essentially backyard resorts for people living nearby. [115]

Outside the Wasatch Front area, recreationists tended to come from greater distances. On the Fishlake, for instance, approximately 50 percent of the visitors came from Nevada and California. [116] In spite of an accelerated timber harvest caused by an extensive pine beetle infestation, the Ashley considered recreation its biggest single responsibility, in large part because of the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area. [117] In Teton County, WY, 80 percent of the economy was geared to tourism, and local citizens demanded that the Teton and Targhee maintain those values attractive to tourists. [118]

A major problem in meeting the public demand for recreation was caused by the unwillingness of the administration and Congress to provide needed funding. During the 1970's, even the creation of the Sawtooth and Flaming Gorge National Recreation Areas provided little additional money. The region took funds from other forests and relied, to a limited extent, on private funding sources. Congressman Gunn McKay of Utah did succeed in getting some campground development money. [119] Supervisor Lavin of the Boise indicated that the main problem was to keep the campgrounds and picnic areas in good shape with increased use and declining funding. [120] Supervisor Richard Hauff of the Salmon said that budgetary shortages created a major problem for recreation on his forest, as well. [121]

Moreover, Congress was unwilling to approve funding for recreation improvements and administration through the collection of additional fees for recreational activities. It was suggested that Congress impose recreation user fees beyond the funds going to the Land and Water Conservation Fund, but Congress refused to authorize such charges. [122] The demand for a forest camping experience was so great that some forests had to limit stays to 16 days, though none used advance scheduling except for group areas. [123] Demand on some national forests became so great for group camping experiences that Uinta Supervisor Don Nebeker wondered whether they would be able to provide for the apparent demand. [124]

Under these conditions, some Forest Service officials rethought the purpose of forest camping facilities. Most wilderness advocates and forest officers favored solitude in camping facilities, and the Service built most campgrounds in an attempt to provide it. Many people with urban backgrounds, however, seemed to prefer their sylvan experience at closer quarters. During hunting season, the national forests sites filled with "camper cities," containing as many as 50 recreational vehicles parked close together. [125]

|

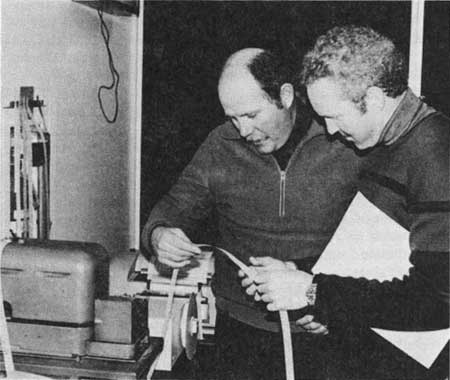

| Figure 98—Checking the tape at Avalanche Forecast Center, Old Salt Lake Airport, 1981. |

While camping was important, two types of experiences—dispersed recreation and skiing—increased most rapidly after 1970. The dispersed recreation, particularly by off-road vehicles, caused some difficulty because of the tendency of people to perceive the public lands as their own and to believe that they could do anything they wanted on the forests. [126] In an attempt to deal with problems caused by excessive noise and indiscriminate killing of wildlife, the forests wrote off-road vehicle travel plans for the use of motorcycles, trail bikes, snowmobiles, and similar vehicles. The Boise, for instance, completed its off-road travel plan in 1976 which restricted such vehicles to roads and trails on 70 percent of the forest. [127] In 1979, the region conducted a sample off-road vehicle management review on the Uinta and Fishlake in order to gauge the impact on an urban and a rural forest. The data were used in planning off-road vehicle management for the region. [128] The Wasatch found it necessary to ban off-road vehicles in the canyons east of Salt Lake City. The Humboldt banned such vehicles in the Ruby Mountain Scenic Area. [129]

As urban forests, the Toiyabe and Uinta put considerable effort into trail and road maintenance. Uinta supervisor Don Nebeker indicated that one reason for this effort was that dispersed recreation (hiking and driving) was less costly. In addition, since the Uinta was so close to an urban area, he recognized that the forest approached the condition where people will "saturate almost every opportunity that we've got to put facilities in without destroying the environment itself." [130]

As with other functions, there was little extra money for construction of new facilities on the forests. [131] Even rural forests like the Salmon emphasized dispersed recreation in part because of budgetary problems and also because many visitors "do not require conventional Forest Service campgrounds," with picnic tables, since they come in recreational vehicles. [132]

Region 4 retained its position as "the leader in winter sports management in the Forest Service." [133] By 1984, 26 ski areas operated with permits on the region's national forests. The most active areas tended to be concentrated along the Wasatch Front, near Jackson Hole, and at Sun Valley. Other ski resorts were located in areas ranging in geographical dispersion from Charleston Mountain near Las Vegas on the southern end of the region to Heavenly Valley near South Lake Tahoe in the Sierra on the west, and to Brundage Mountain near McCall on the northwest.

During the early years, the Forest Service and volunteers provided many of the safety services for ski areas. By the early 1980's, the Service had turned much of the responsibility over to the ski area operators. The operators then provided most of the workers for avalanche control. This change was facilitated by gas-charged tubes called avalaunchers replacing the more dangerous 105 mm howitzers in many areas. In some cases, to meet technical requirements, ski area personnel received temporary appointments in the Forest Service. [134] Professional ski patrol personnel tended to replace volunteers. Responsibility for lift inspection was turned over to many of the ski areas. This was possible particularly in States like Utah which provided Passenger Tramway Safety Board certification of private engineers to do the inspections. In many areas where qualified private inspectors were not available, the Forest Service continued to provide inspectors. [135] In perhaps no activity more than skiing was cooperation with other Federal and State agencies and with private industry so important.

|

| Figure 99—Loading a 75mm pack howitzer used to control avalanches, Little Cottonwood Canyon. |

The Service participated in land exchanges with some ski areas. [136] A proposal for the interconnection of ski areas on both sides of the Wasatch Mountains, between Big and Little Cottonwood Canyons and the Park City area, involved the Forest Service in considerable discussion with local governments, the State of Utah, and private industry. [137]

In the early 1980's public involvement in controversies over proposed ski area expansions and new developments became particularly significant. The ongoing development of the Snowbird ski area in Little Cottonwood Canyon on the Wasatch raised considerable public controversy. Conservationists opposed its proposed expansion into the White Pine drainage adjacent to its present runs. [138] The proposed Heritage Mountain Resort east of Provo generated considerable opposition because of the potential use of Forest Service land, the impact on the local community, and problems of financing. [139] By April 1986, it appeared that the special use permit for the resort would be canceled because of its inability to secure financing. [140]

River-running generated steadily increasing interest. Until a new program was instituted in 1984, the Forest Service received very little revenue for managing river operations. On the Middle Fork and Main Salmon River, for instance, outfitters generally charged between $100 and $200 per day for their services on a trip lasting 3 days, from which the Service got a modest $1.25. In 1984, however, the Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management instituted a new fee schedule that was designed to reach 3 percent of the customer charges after 3 years. In Salmon Supervisor Richard Hauff's view, the "new permit fees should produce a fair return and help us to manage that use." [141]

The Salmon allowed both unguided float trips and professionally guided groups on a fifty-fifty basis. The outfitter permits for such trips, even after 1984, were closely held monopolies. [142] In about 1982, potential outfitters who had no access to float the rivers secured approval from the Service for a program that would have advertised and granted these permits on a competitive basis. Established outfitters complained to their congressmen who applied pressure on the Chief to change the policy. The revised policy continued essentially the status quo. Thus, if outfitters holding a current permit perform satisfactorily they can continue to renew the permit annually. [143]

The South Fork of the Snake River in the Bridger-Teton also was particularly popular for float trips. In fact, the Snake experienced more day use than the Salmon, perhaps because of its relatively easy accessibility to major highways and to visitors to Grand Teton and Yellowstone National Parks. In 1979, the Bridger-Teton proposed designation of 50 miles of the upper Snake as a wild and scenic river. Considerable opposition emerged from private landowners in Jackson Hole to the designation of the upper 25 miles. The Bridger-Teton continued to press for the lower 25 miles, which is entirely within the forest. By 1984, the proposal rested in limbo because of opposition from the Office of Management and Budget, which feared that the Bridger-Teton would ask for funds to manage the river if the special status were approved. In 1984, Supervisor Reid Jackson of the Bridger-Teton said the Service would settle for designation of the lower 13 miles as a scenic river, to protect it from potential hydroelectric development. [144]

After the creation of the Sawtooth National Recreation Area in 1972, the region experienced some difficulty in its management. Under the enabling act, the Sawtooth was to maintain a western outdoors atmosphere with continued rural community life, ranching and grazing, and limited logging and mining. Sawtooth officials proceeded to purchase scenic easements on private lands, sharply regulating future use. [145] If an owner refused to sell the easement, the Service could acquire it under condemnation proceedings. The attempt to condemn such easements led to a suit that the Supreme Court decided in favor of the Forest Service in 1977. [146] In some cases where developers proposed subdivisions containing incompatible uses like A-frame houses and trailer courts within the recreation area, the Forest Service purchased the land. Regulations allowed some mining as long as it did not substantially impair the scenic beauty or damage fisheries and if the claim had been located prior to August 22, 1982. [147]

The Service encountered some difficulty in eliminating nonconforming uses. Some landowners, backed by Senator James McClure, wanted the Service to interpret the legislation as requiring an exchange for property within the Sawtooth at the option of the landowner. Regional Forester Vern Hamre disagreed, since he thought the legislative history did not support that view. He invited McClure to obtain a declaration from the Interior Committee chairman, Senator Henry Jackson of Washington, or to secure language in an appropriation bill, supporting his view. McClure could secure neither, and the region went ahead as before. [148]

Problems at the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area were less severe but similar to those at the Sawtooth. Owners of private land within the Flaming Gorge proposed to subdivide into one-tenth of an acre lots suitable for trailers. County commission chairman Albert Neff, who favored the subdivisions, became quite indignant when the Service suggested the county regulate such incompatible use through zoning. Neff carried enough political clout to get a congressional hearing on the matter. Vern Hamre went fishing with Senators Frank Moss and Alan Bible, who told him that they would stay out of the dispute. Later the commission denied the subdivision proposal, and the Forest Service purchased the land. [149]

In commenting on the proposed management plan for the Flaming Gorge, Joel Frykman, formerly assistant regional forester for timber management, thought the forest had been unduly strict in dealing with timber values and might have exceeded its authority in regulating private and State lands, but that it was insufficiently strict in wildlife management. Such views did not receive broad public support. [150]

Like the Sawtooth, the Flaming Gorge's management plan emphasized recreation and scenic values. The road layout conformed with these values. The Ashley recommended the designation of a section of the Green River as a wild and scenic river. The proposal was not acted upon. To enhance wildlife values, the Ashley transplanted a number of bighorn sheep to the Flaming Gorge. In cooperation with private developers, the forest encouraged conforming private development, including that of major resorts. The Flaming Gorge had two visitor information centers staffed full time by Ashley employees during the summer. [151]

In 1984, the Uinta National Forest accepted responsibility for recreation management at Strawberry Reservoir. Constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation, the reservoir is part of the Central Utah Project. On June 1, 1984, regional and forest officials joined State and Bureau of Reclamation representatives in dedicating a recreation complex at the site. Camping, boating, and fishing are the main activities at the reservoir. [152]

Forest Service management of archeological, historical, and geological functions—especially archeological—expanded considerably in Region 4 after the early 1970's. [153] As a result of a number of executive orders, all Federal Government agencies were required to conduct inventories of any land-disturbing activities to determine archeological values involved. If such values existed, the Service and region were committed to protecting them or taking mitigating action such as excavating and documenting the findings. The program was quite expensive, since each national forest had to have access to an archeologist and the sites were often quite isolated.

The region experienced a major problem when, as soon as the archeologists began work, the sites became public knowledge and often attracted opportunists who tried to profit from finding and selling artifacts, amateur collectors who disturbed the sites, and vandals who destroyed ancient artifacts. Robert Safran indicated that sites at Joes Valley on the Manti-LaSal and Wheeler Peak on the Humboldt were particularly difficult to manage because of such vandalism.

In some cases, the forests conducted cultural management programs themselves or secured the help of interested local historical associations. The Challis National Forest, for instance, managed a dredge and museum on the Yankee Fork at Custer. Through creative thinking, the forest succeeded in getting considerable private involvement by organizing a dredge society. The Sawtooth Interpretive Association, a private group organized in 1972, cooperated with the Sawtooth NRA in providing interpretive services at the Redfish Lake Visitor Center and at the Stanley Ranger Station. [154] At Johnny Sacks Cabin in Island Park, the Targhee succeeded in making an arrangement for the local historical society to manage the site. The Bridger-Teton operated a display cabin adjacent to their headquarters showing an early ranger station and its furnishings.

One important program was the development of archeological studies along Clear Creek on the Fishlake. Mitigation became necessary owing to archeological damage resulting from the construction of Interstate 70 through the area. The Fishlake cooperated with the State of Utah, Brigham Young University, and the Federal Highway Administration in conducting digs at the site. By early 1986, mitigation had proceeded well, and the State of Utah had planned a visitor center to explain the prehistoric Fremont culture. [155]

Wilderness

The Wilderness Act directed the Forest Service to consider the suitability of primitive areas for wilderness designation. In addition, in August 1971 the Service undertook the evaluation (called RARE I for the first Roadless Area Review and Evaluation) of all undeveloped areas of more than 5,000 acres. Completed by June 1972, findings were announced in January 1973. For the entire National Forest System, the report recommended 12.3 million acres for wilderness protection from the 56 million studied. In response to the review, the Sierra Club and other conservation organizations filed a suit in Federal court to force the Service to protect the entire 56 million acres. In August 1973, Federal Judge Samuel Conti granted a preliminary injunction supporting the appellants. The injunction led to a promise that the Service would prepare an environmental impact statement consistent with NEPA and reconsider wilderness preservation, before authorizing any development. [156]

As far as Region 4 was concerned, the Sierra Club suit seemed unnecessary. The Washington Office directive had forced the region to conduct the review in an impossibly short 11 months. Recognizing that development did not threaten most of the roadless area, the region passed over those tracts low in mineral and timber values. In the process, they disregarded a number of locations because they were not threatened. These included Wellsville Mountain, Mt. Olympus, Mt. Nebo, and Lone Peak on the Wasatch Front and Mt. Borah in Idaho. [157] In addition, some forest officers believed that the designation of wilderness had the effect of calling attention to an area and that the impact might be less with no designation. [158]

Some Region 4 officers such as Oliver Cliff resented the implication that any areas without roads ought to be designated as wilderness. For them, certain qualities of solitude and beauty were necessary to wilderness, and the absence of roads did not automatically invest an area with a wilderness character. [159]

In spite of the problems with RARE I, the Nixon and Ford administrations were reluctant to undertake a second review of roadless areas. With the inauguration of President Jimmy Carter in 1977 and particularly with the appointment of M. Rupert Cutler as Assistant Secretary of Agriculture, the climate changed. Between 1977 and 1979, the Service undertook the study called "RARE II" in which it evaluated 67 million acres of roadless tracts. The Forest Service expected that any lands not recommended for wilderness under RARE II would be released for multiple-use management at the same time Congress designated the new wildernesses. Under RARE II, 36 million acres nationally were to have been opened for multiple-use management, 15.4 million were recommended for wilderness and 10.6 million acres were reserved for future action. [160]

The whole process ground to a halt, however, with the California v. Block ruling in 1979 that the Service had failed to comply with the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) requirements of NEPA. This ruling prevented the release of roadless areas for multiple-use management and threw them into consideration with the forest plans. Under the Wilderness Act the ruling tossed them into the lap of Congress, since the Service no longer had the authority to designate wilderness by presidential proclamation.

In general, Region 4 officers believed that RARE II was quite well done. Vern Hamre pointed out that a number of areas were included that had not been included in RARE I. [161] Pat Sheehan of the regional information office argued that the public interaction generated by RARE II was "one of the most intensive public involvement efforts that . . . [Region 4] has undertaken." The RARE II recommendations of 1979 formed the basis for the wilderness bills considered from 1984 through 1986.

Until 1984, however, the only tangible result was the Central Idaho Wilderness Act that redesignated the Idaho Wilderness Area as the River of No Return Wilderness and had come about because of Idaho sentiment and the close cooperation between the Service and Senators McClure and Church. [162]

Some former employees were bitter about the results of the process. George Lafferty, for instance, said that while he "generally supported a Wilderness System throughout" his career, he was concerned to see "the Forest Service being hamstrung" in its attempt to manage national forest lands. He thought the court rulings had brought the Service "to a point where" it could not properly "manage the study area lands—and they are extensive." [163]

After the California ruling sidetracked RARE II, the Service began working with Congress in drafting wilderness legislation on a State-by-State basis. Working with political leaders, environmentalists, commodity interests, and the general public, the Service tried to shape each bill to fit the wilderness needs of each State. The bills under consideration for states in Region 4 were based essentially on the RARE II evaluations, but initially some of them contained either redundant or offensive features. The Utah bill, for instance, emphasized a right to graze on the forests. Regional Forester Tixier was concerned about this provision because he wanted to maintain the traditional status of grazing as a privilege as confirmed in the Wilderness Act rather than as a vested right. The original bill also contained what was called "hard release" language—essentially redundant, but potentially contentious provisions—ordering the Service not to reconsider the released areas for wilderness until the year 2000. [164]

Consideration of the wilderness bills for each of the States in Region 4 was extremely difficult and at times acrimonious. A compromise between House Public Lands Committee Chairman John Siberling and Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee Chairman James McClure revised the "hard release" language in the Idaho bill to allow consideration of released areas during development of the next forest plan, or roughly in 10 years. [165] Similar language was included in the Utah bill, passed in September 1984—the first from Region 4. The Utah bill, also the result of compromise, set aside 750,000 acres as wilderness, some parts without controversy, others after considerable, and at times heated, discussion. [166] By spring 1986, the Utah and Wyoming bills had passed, Congress was not actively considering the Idaho bill, and differences among members of the Nevada delegation, particularly over the potential Great Basin National Park in what is now the Wheeler Peak Scenic Area, had stalled that bill. [167]

Wildlife and Feral Animals

Several considerations dominated the disputes over wildlife and feral animals after 1970. These considerations included protection of threatened and endangered species: what to do with wild horses and burros, perceived by many as a nuisance but with fondness by others: the reintroduction of game species into areas they had formerly occupied; and the impact of change and development on wildlife habitat.

The management of wildlife habitat continued much as before, with stream improvement for various kinds of fish, prescribed burning, and planting of various browse species for larger wildlife. [168] Wildlife considerations assumed considerable importance, because, as Regional Forester Tixier put it, "hunting is almost a religion" in Utah, Idaho, and Wyoming and the fishing in the region is among the best in the United States. [169] Although a considerable misperception existed, because of the occasional shooting of elk in hayfields and refuges, the Teton Wilderness was one of the best places to hunt in the world. [170]

The best example of the region's problem with threatened and endangered species is undoubtedly the grizzly bear, which is on the threatened list. Within Region 4, the focus of this problem was the greater Yellowstone Park ecosystem, which included the Bridger-Teton and Targhee National Forests, forests in two other regions, and two national parks. [171] Representatives of the forests and parks together with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the State fish and game departments of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana formed an Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee (IGBC) and several subcommittees to investigate and recommend action for dealing with problems caused by the bears' threatened status. The committee received research support from the Fish and Wildlife Service.

After reviewing conditions, the IGBC designated Management Situation Zones, specifying grizzly treatment for various areas. [172] Situation 1 zone was primary grizzly habitat where the bears were given priority over other uses in the area, though commodity production was still allowed. In Situation 2 habitat, the bear was not perceived as the primary inhabitant and other use prevailed where conflicts occurred. Situation 3 included developed and inhabited areas with high human use. Bears were generally removed from those areas. Situation 4 zones were areas suitable for bears in which they did not live and in which they could be established. Situation 5 zones were habitats in which grizzly bears did not live and which were generally unsuitable for them.

The major difficulty in dealing with the grizzly was not the resolve of the Forest Service and other agencies to solve the problem, but rather the unwillingness of some in the public to support the regulations. In one case where an outfitter shot a bear in the Teton Wilderness, the Fish and Wildlife Service secured a grand jury indictment. During the trial, however, the judge allowed the offender to plead guilty to cruelty to animals, which allowed him to retain his outfitter's license. Then the judge suspended both the fine and the jail sentence.

In another case, however, Forest Service personnel, especially Supervisor John Burns of the Targhee, resolved a potentially explosive situation. In 1983 a grizzly sow designated number 38 moved with her cubs from the Gallatin National Forest to Two Top Mountain on the Targhee. Two Top had been designated as Situation 1 habitat, and under the guidelines sheep grazing had been allowed. Since bear had primary consideration in the area, after it started attacking the sheep, the rancher had to move them from the grazing allotment to private land. The bear followed the sheep, however, and began spending the day on the forest and the nights marauding in the herds on private land. After a week of consideration, the committee agreed to trap the bear and the cubs and relocate them in a remote area of Yellowstone Park.

Because of its location and resources, the Bridger-Teton was a particularly critical area in wildlife management. Wildlife values played a part in virtually everything that was done. When the forest conducted timber sales, for instance, officials coordinated their actions with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Park Service, and various preservation groups. Twenty-six thousand head of elk summered on the forest in addition to large herds of mule deer, moose, and bighorn sheep. Endangered species such as the bald eagle and the trumpeter swan also inhabited the forest. [173] On a number of other forests as well, roads were often closed after a timber sale so that easy access did not threaten the elk population with excessive hunting pressure. [174]

It took considerable time for the region to come to the position where wildlife considerations were generally recognized as being as important as commodity production. That change came about largely through reeducation of employees to convince them to understand how to consider wildlife in their decisions. As Mike Gaufin indicated, wildlife biologists helped with the reeducation by explaining how such measures as leaving a little litter after a timber harvest benefited the wildlife. Gaufin told of a discussion with one of the region's engineers, just before both retired, who said to him, "Mike, I used to hate to see you come in my door because I knew every time you came in, you were going to be standing in the way of progress, but thank God you did it." [175]

After careful studies, the region authorized State fish and game departments to reintroduce wildlife in certain suitable areas. Examples included mountain goats in the Lone Peak Wilderness area and bighorn sheep in the Mount Nebo area. [176]