|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 9

An Era of Intensive Multiple-Use Management: 1960 to 1969

By the late 1950's, the Forest Service, led by Chief Richard E. McArdle, wanted a congressional mandate authorizing its de facto policy of multiple use and sustained yield. Resistance to such legislation came from the two ends of the spectrum—those who favored use for commodities like timber and range and those who favored preservation of forests for recreational activities and wilderness. As Congress began considering the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, both the Sierra Club and the National Lumber Manufacturers Association expressed opposition. Sierra Club members believed the act placed wilderness in jeopardy; the lumbermen thought timber production and protection of water flows as authorized in the 1897 Organic Act should be given top priority. [1]

Some rural communities agreed with the lumber manufacturers. In a talk to a group of people in Vernal, Supervisor William D. Hurst said that the Forest Service was required to manage the national forests not just for timber, but also for watershed, grazing, recreation, and wildlife. "My audience," he said, "frowned on this. They thought the Forest Service was created to maintain a constant timber supply and maintain water yield." [2]

To diffuse opposition, the Forest Service undertook a successful lobbying campaign, and Congress passed the act on June 12, 1960. As passed, the act confirmed existing policy by authorizing the Service "to develop and administer the renewable surface resources of the national forests for multiple use and sustained yield of the several products and services obtained therefrom." [3]

With the passage of the act, officers in Region 4 could cite a congressional mandate for their policy of multiple-use management. Where, in the past, the Service had recognized various uses by regulation, the law specifically authorized the activities. Most important, it acknowledged recreation, wilderness, and wildlife as legitimate forest values, on par with the production of commercial commodities. This recognition dealt a lethal blow to the futile efforts of stockmen and lumbermen to have their interests acknowledged as preemptive. Most important, perhaps, the law recognized that the Service did not have to press for maximum commodity production, but rather could strive for the best combination of the diverse functions. [4]

Concerns over activities other than range and timber management emerged as major new challenges in the region. This expansion was particularly critical as the demand for recreational uses increased. Recreation emphasis intensified with the passage of the Wilderness Act in 1964, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act in 1968, and the National Environmental Policy Act in 1970, all of which placed additional burdens on the Service's resource management capabilities. Wildlife received increased emphasis with the passage of the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966.

Implementing Multiple-Use Planning

The increase in forest use intensified a primary concern for the fragile lands of Region 4. [5] As Regional Forester Floyd Iverson put it in a statement on long-range objectives in 1961, the "major water resources, the bulk of the timber, a significant amount of summer forage for domestic livestock, much of the big game habitat and a large majority of the outdoor recreation attractions in the Intermountain area are situated within the boundaries of the national forests." Overgrazing and improperly planned logging roads had already revealed the need for multiple-use management. Increased recreational use made this need even more imperative.

Planning for multiple-use management did not proceed in a vacuum, since with 55 years of experience the Forest Service recognized the conflicting demands on national forest resources. As Neal M. Rahm of the Washington Office put it at a regional foresters and directors meeting in November 1960, forest officers began, like urban planners, with a recognition that conflicting demands would exist, but instead of zoning to prevent conflict, they tried where possible to design "coordinating requirements for different kinds of uses or services within a particular area, unit, or zone." The Service "adopted [exclusive use] only when multiple use is impossible or impractical." Nevertheless, while striving for properly balanced use, the Service recognized that particular values might dictate dominant use in certain areas. [6] As Richard McArdle emphasized in a speech before the Fifth World Forestry Congress in Seattle in 1960, in planning for multiple-use, Forest Service officials were concerned particularly with limitations placed in planning for the proper use of resources by the diversion of national forest lands from potential multiple-use to nonforest purposes such as superhighways, transmission lines, and dams. [7]

Basic to all such multiple-use management considerations was concern for the land and thus for watershed management. In recognition of watershed condition as the limiting factor in all land use planning, the Service realigned its divisions, creating a Division of Watershed and Multiple-Use Management in each region and the Washington Office in 1960 to ensure watershed protection and coordinate multiple-use management. Initially headed by Leon R. Thomas, Region 4's division was directed by Gordon L. Watts in the mid-1960's. [8] In 1969, the region assigned P. Max Ross as Regional Planner-Coordinator, to facilitate cooperative efforts between line officers and study teams assigned to plan for activities in complex situations where potentially conflicting uses and interests might appear. [9]

Though the writing of multiple-use management plans had begun in the late 1950's, Region 4, with the largest national forest land area and greatest geographic diversity outside of Alaska, moved somewhat less rapidly than some other regions in completing its subregional multiple-use management guides. [10] These seven subregional guides were completed in 1960 and put into effect for planning in 1961. [11] Subsequently, the region's district rangers began writing multiple-use plans for their districts. [12] In 1965, the subregional guides were consolidated into a regional multiple-use management guide. [13]

In the early 1960's, when it became evident that planning and execution errors were being made, Regional Forester Iverson began to have rangers prepare multiple-use surveys whenever they intended to undertake an activity that might adversely affect the national forest. These were the forerunners of the Environmental Impact Statements required by the National Environmental Policy Act, but they were implemented voluntarily in accordance with a belief that such surveys would facilitate better management. Meeting resistance at first because of the additional paperwork required, they produced worthwhile results by reducing costly errors. [14]

|

| Figure 82—Ranger Robert Hoag and Deputy Supervisor William Deshler in planning session at Bridgeport Ranger Station, 1962. |

By the late 1960's, after more than a decade of multiple-use planning in one form or another, the regional officers recognized that the numerous competing interests and the relative complexity of writing plans for critical environmental areas created considerable difficulty in the efforts to implement the ranger district multiple-use management plans. [15] A major problem came in dealing with the public—both commodity interests and preservationists—who tended to interpret the term "multiple use" as synonymous with development. Trying to explain that the Service intended to manage the lands both for optimum resource development or use and for other nondevelopmental activities on a sustained-yield basis was difficult, particularly when the users did not understand that if the Service gave needed protection to certain critical watersheds they could not develop all such areas. This was especially true when Congress failed to provide sufficient funding to rehabilitate fully areas like those previously logged, or when the region had to deal with critical environments like the Tahoe Basin, the South Fork of the Salmon River, or the west slope of the Teton Range.

Because they were trained as generalists, many of the rangers who wrote the district multiple-use plans lacked "adequate knowledge of ecologic systems and their interaction," At first, the region tried to remedy this situation by hiring specialists such as landscape architects, soil scientists, archeologists, wildlife biologists, and hydrologists. Engineering staffs were assigned to the smaller forests in the region as they had to the larger forests in the 1950's. [16] Beginning with the Boise, forest level specialists in personnel management and contracting were added to the staffs. [17] Such specialization extended to the purchase of computer equipment for data processing. [18]

H.H. "Rip" Van Winkle remembered returning from a staff position in the regional office to the Teton as forest supervisor. It "had changed a whole lot," he said, "We were developing into specialists all along the line . . . . There were game biologists, engineers, and range experts . . . . So that the staff was becoming specialized instead of centralized the way it had before. When I first started out in the Service you did pretty near everything yourself the best you knew how without knowing very much about it." [19] By 1963, the Teton had a staff of about 60 permanent employees. [20]

Specialization became most evident at the regional level. Numerous specialists were brought into the various regional office divisions to meet growing needs. For instance, Robert Safran came to the regional office in 1962 as special use expert to develop the necessary contract provisions to manage the increasing number of permits. [21] In 1963, a reorganization at the regional office led to the assignment of Don Braegger as Regional Construction Contracting Officer, and subsequent studies by the Washington Office indicated considerable savings through the use of contracts rather than force accounts. [22]

The increasing complexity of Forest Service operations required considerable additional training for existing employees. Led by Assistant Regional Forester Lester Moncrief, the region carried on a great array of expanding and diverse training programs. Subjects included decentralized contracting; workshops for wage-board wage determination; and how to write better letters, clearer directives, and more readable manuals and handbooks. Such traditional training as range reseeding, watershed management, and timber management continued as well. [23]

By the late 1960's, the increasingly frequent use of interdisciplinary teams created problems, since specialists often pushed for the interests represented by their disciplines without adequately recognizing the needs of other interests. In reviewing this problem, Floyd Iverson recognized that someone on each team had to represent the general interest, and after considering the options, he assigned line officers—rangers and supervisors—to these teams to help "assure understanding and adequate coverage of multiple-use coordination." In other words, the regional administration expected the line officers to provide the general knowledge that would serve as a balance to unduly single-minded interests of specialists.

Budgetary limitations, along with the need for efficient and effective work, necessitated the continued measurement of productivity with a view to cost reduction. [24] The Washington Office mandated continued workload analysis of regional offices, forest supervisor offices, and district ranger offices, which was completed in 1969. [25] Under Washington Office direction, the region continued studies under the supervision of Assistant Regional Forester Tom Van Meter, to identify the optimum size for ranger districts. The studies gave particular consideration to the possible consolidation of districts with headquarters in the same community, with seasonal headquarters, and with small workloads. [26]

In 1969, the American Institute of Industrial Engineers published research by two Washington Office employees, Ernst S. Valfer and Gideon Schwarzbart, who summarized the criteria for district consolidation. Based on questionnaires sent to each forest supervisor, the study took various responsibilities into consideration. After reviewing the responses, the researchers concluded that three factors seemed most important in determining optimum size: budget, base workload, and acreage. Devising a formula for computing optimum size, the researchers cautioned that "an effective organization must be more than purely an efficient one in that it must satisfy both its economic requirements and the sociotechnical demands of the organization's sponsors, its own members, and its clients (customers) or the public." [27] Foresters recognized the importance of taking all factors into consideration. If units were too small, the Service could not make effective use of the ranger's time. When the units were too large, however, relationships with forest users suffered because the rangers were unable to meet the users and to deal personally with critical problems.

In spite of the demand for economy, the regional office and some of the national forests were forced to seek new quarters, largely because of the increased size of staffs and complexity of the work. In the summer of 1965, the regional office moved from the Forest Service building on 25th Street and Adams Avenue to share a newly completed Federal building on 25th Street between Kiesel and Grant Avenues. Various divisional headquarters, which by that time had occupied offices in several buildings around the downtown area, were consolidated in the new building. The Intermountain Station headquarters remained in the old building until 1985.

Excellent new offices for the Challis, Targhee, and Teton National Forests were opened in Challis, St. Anthony, and Jackson. [28] In Boise, the old Assay Building office became so crowded that the Boise National Forest Supervisor and most of his staff moved to the Belcher Building. The engineering staff, the soils specialist, and the staff for one of the ranger districts occupied the Assay Building. [29]

The increase in staffs and the added paperwork necessitated by interdisciplinary functions created changes within the system. The job of the ranger became much more complex. [30] Forest rangers who had previously functioned as "kings of their own domain" became members of interdisciplinary teams and often spent more time in the office preparing reports than on the ground making management decisions. As conditions changed, Carl Haycock, by then retired, expressed the view of quite a few oldtimers when he said he would not like to be a forest ranger anymore. "The Forest Ranger," he said, "is no longer an administrator; he's a pencil pusher . . . . So much preparation of reports and related paper work is demanded of him that he doesn't have the time to get out and really manage the resources on his Ranger District." [31]

These complexities created additional difficulty for the region as the legal adoption of the concept of multiple use coincided with a change in the nature of the public with which the Service had to work. In practice, this change required careful application of techniques for working with the conflicting interest groups. In the past, the region had used advisory councils, ad hoc committees, town hall meetings, and formal hearings principally "in formalized consideration of areas where the Forest Service . . . [had] established its position well ahead of time." Forest advisory councils particularly were used "most frequently" as a "means of communicating...[the Forest Service] viewpoints and positions to others." [32] Show-me tours and press releases were used to achieve the same purposes. [33]

Ranger Jack Wilcox put it succinctly. "Around the early sixties the public finally got interested in what was happening to Federal lands . . . . They didn't like what they saw, and they started to get legislation to correct what they thought was wrong. I think that is good that they took an interest . . . . We were getting complacent." [34]

By at least the late 1960's, the use of an advisory board as a ratifying council seemed out of date. The many groups and individuals interested in Forest Service decisions were simply too diverse and their interests often too conflicting. Under the circumstances, the Service had to find ways "to solicit and listen to the ideas of others, so these ideas . . . [could] be utilized in planning and management decisions," As part of the 1969 Assistant Regional Forester-Forest Supervisor meeting, the region's managers resolved to move as rapidly as possible to develop skills and techniques "before decisions are reached . . . [to] involve a greater cross section of the general public in planning and decision-guiding [procedures]."

During the 1960's, the region began a program of annual field trips for educators. Although this proved an excellent means of developing closer relationships with university faculties and administrations, by the end of the decade, the Service had not devised a means of solving the problem of reconciling the interests of competing constituencies. In fact, the problem was not solved with any degree of satisfaction until after the passage of the National Forest Management Act in 1976. In many ways, it has not been solved yet, though the 1985 decisions on wilderness areas seem to indicate that it might be solved through some sort of conflict-resolution procedure emphasizing compromises. The major problem with this example, however, is that the resolution required congressional action, which is far too unwieldy and time consuming a solution for all but the most serious problems.

Inspections

After his appointment as Chief in 1962, Edward P. Cliff raised some questions about the existing inspection system. In response to Cliff's suggestions at the Regional Foresters and Directors meeting in 1964, several proposals were made for modifying procedures. [35]

Cliff asked for staff input, and the region referred the question to the forest supervisors. Boise supervisor Howard E. Ahlskog replied that, while the inspections were important, he objected to the imposition on the forest staffs when inspectors evaluating similar functions came within a few weeks of each other. On the Boise, for instance, the General Accounting Office, Fiscal, and Operations General Functional Inspections and an Internal Audit all had come in one year. Servicing these inspections had required about 5 labor-weeks from the operations division. Ahlskog suggested combining future inspections of similar functions. [36] This had been done to some degree during FY 1964, and he believed similar combinations could be used more extensively in the future. [37]

|

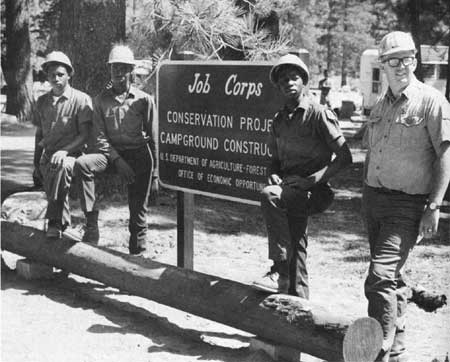

| Figure 83—Job Corps conservation project, Clear Creek Job Corps Center. |

Region 4 as Agent of Social Change

The roles played by the Forest Service became even more complex with the measures taken to relieve unemployment in the Kennedy administration and in the Johnson administration's War on Poverty. Programs such as the Accelerated Public Works Program, the Youth Conservation Corps, the Young Adult Conservation Corps, the Work Study program, and the Older Americans program contributed to the development of forest facilities, but also required considerable time and money to administer. [38]

In 1961, Kennedy sent to Congress a plan entitled "Development Program for the National Forests." Designed as a blueprint for action in meeting public needs, it was expected to provide the basis for Forest Service public works from 1962 to 1972. [39]

To implement this program, the Federal Government began an Accelerated Public Works program in 1963. Although the program was to have lasted 10 years, it was terminated in 1964 (though construction of forest facilities continued under the Operation Outdoors program). [40] Projects covered the full range of Forest Service activities and were undertaken on all forests. These projects included a warehouse on the Uinta, water improvements on the Fishlake, campground facilities on the Wasatch, riprapping and check dams on the Dixie, road construction on the Uinta, footbridges on the Bridger, and trail construction on the Payette. [41]

A good example of the region's role in the War on Poverty was its operation of the Clear Creek Job Corps Center south of Carson, NV, on the Toiyabe. The establishment of this camp created somewhat more local opposition than had the CCC camps of the 1930's. [42] A public hearing in Carson revealed that a considerable minority of the community opposed the center based on the low educational level of the trainees and the fear that boys at the camp might become involved with local girls. Those favoring the center thought it would help in educating deserving young people and preventing long-range welfare and criminal problems. [43]

Started in September 1965, the Clear Creek center had a number of advantages. These included its lovely forested location and the general support of local political leaders. Not the least of the advantages was the selection of Charles J. "Chuck" Hendricks as the first director. An engineer by profession, he was extremely capable and well liked by all. [44]

After arriving at the center, each enrollee was tested and assigned to classwork suited to his educational level. Training emphasized skills needed in jobs then available in the community. At the center, the trainees were expected to work 8 hours a day 5 days a week. Each spent part of the time in classwork and part in public service. [45]

The center achieved some degree of success between 1965 and its termination in May 1969. The average job corpsman was a school dropout. A 1968 study showed that the average enrollee entered with third-grade reading skills and second-grade math skills. On the average, a corpsman stayed in the program 5-1/2 months and during that time advanced an average of 2-1/3 grades. Although only 30 percent of those who entered the program completed their training, 93 percent of those who finished either entered the labor force, joined the armed forces, or returned to school. Although some corpsmen did have run-ins with the law, the crime rate at Clear Creek was lower than for others in the same age group throughout the Nation. In view of the disadvantaged background and low educational status of the trainees, this low crime rate in itself says much about the program. By the end of 1967, the corpsmen at Clear Creek had constructed for the Forest Service $497,000 worth of capital equipment that would probably not have been built without their labor. [46]

|

| Figure 84—Three enrollees welding at Clear Creek Job Corps Center. |

The Rural Area Development Program also affected the region. This program, designed to improve the well being of rural communities, required the cooperation of the regional office's State and Private Forestry Division, under H.S. "Hal" Coons, with other agencies of the Agriculture Department and the State foresters of the various States in the region. The program provided Forest Service technical assistance to rural communities seeking to improve employment opportunities for their citizens. [47]

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 also increased the responsibilities of the Forest Service. Executive orders required Service employees to work actively in hiring people from minority groups and in seeking contracts with minority businesses for various goods and services. Subsequent Service studies indicated general compliance, though integrating minority representatives into an organization dominated by white males was not always easy. [48]

Foyer Olsen, then a ranger on the Dixie National Forest, remembered an effort he had to make in this regard. He found it necessary to train his employees to help a youth hired from a poor neighborhood in Ogden understand how to fit into the working world. The effort proved successful for all concerned. [49]

|

| Figure 85—Bristlecone pine, Wheeler Peak Scenic Area, 1968. These trees are the oldest living things in the world. |

Recreation

Perhaps no field in Region 4 increased in complexity as much as did recreation management, headed by Assistant Regional Forester John M. Herbert during the 1960's. Gone were the days when picnic tables, garbage cans, water faucets, privies, and access roads were the extent of developed recreational facilities. While the region continued to construct such things, it also expanded in a number of other areas, including cultural resource management.

The region undertook a program of determining which so-called "Near-Natural" areas required special treatment because of their unusual interest. These included virgin, scenic, geologic, archeological, and historical sites. The regional office sent instructions to the forests giving criteria for inventorying and designating such areas. [50]

Some of these areas were among the most beautiful and interesting in the Intermountain Region. In 1959, for instance, the Service designated the Wheeler Peak Scenic Area, consisting of 28,000 acres within the Snake Range in the Humboldt National Forest. The home of the bristlecone pine, the area contained 13,000-foot Wheeler Peak, gorgeous alpine lakes, and magnificent vistas. The scenic area also contained a number of examples of Indian petroglyphs that the Humboldt tried to protect. [51] The Service undertook an extensive construction program to provide campgrounds and roads for visitors. Managed under the multiple-use philosophy, the area provided for grazing, watershed protection, wildlife, and mining in addition to recreation. [52]

The Humboldt also contained the Ruby Mountain Scenic Area designated in 1964. [53] It too has magnificent scenic and recreation values, and includes a number of other uses.

Another example of the diversity of cultural resources is Minnetonka Cave on the Caribou National Forest. [54] It is one of only two caves (the other is Blanchard Caverns in Arkansas) currently operated by the Forest Service. During the 1930's, public works programs provided some capital improvements. The ranger district tried to operate the cave for public enjoyment for some time with little success; in the late 1950's the ranger got the St. Charles, Idaho, Lions Club to take it over under a special use permit.

After running the cave for about 14 years, until 1963, the Lions found the project too burdensome to handle. They lobbied the Idaho congressional delegation, particularly Senator Frank Church and Congressman Ralph Harding, to get the Service to take over operation of the cave and to get the Federal Government to construct needed improvements. The Federal Government improved the road up St. Charles Canyon to the cave, and the Forest Service secured a surplus generator and installed new lights. The Service keeps the cave open, with tour guides, from early June until Labor Day each year. Operation of the cave has become a regular budget item for the Caribou.

Much of the work of cultural resource management has been done in cooperation with outside parties—often with university professors. Examples are numerous: research on and recommendations for management of the Lander Trail, an important nineteenth-century transportation route in the Bridger and Caribou National Forests, by Peter T. Harstad, historian from Idaho State University; [55] a cooperative dendrochronological study of bristlecone pines—the world's oldest living things—on the Humboldt National Forest by W.C. Ferguson and J.O. Klemmedson of the University of Arizona; [56] and archeological excavation at the Redfish Lake Creek Indian Shelter on the Sawtooth National Forest by Earl Swanson, an archeologist from Idaho State University. [57]

|

| Figure 86—Senator Frank E. Moss and Lady Bird Johnson at dedication of Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, August 1963. |

The Forest Service undertook numerous cooperative projects with other Federal agencies. Perhaps the most complex example involved the Forest Service, Bureau of Reclamation, and National Park Service, in the establishment of the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area. Since the Green River and a number of its tributaries flow through the Ashley National Forest, activities of the Bureau of Reclamation on the massive Colorado River Project designed to control the flow of the river at large dams also affected the Forest Service.

As the Bureau of Reclamation constructed the Flaming Gorge Dam near the Utah-Wyoming-Colorado borders in eastern Utah, both the Forest Service and Park Service proceeded with plans for recreation facilities in the area. Between October 1958 and March 1959, the two agencies carried on discussions and exchanged correspondence about administering the facilities at the lake that would be under both agencies. Proposing the creation of a national recreation area within the area of its jurisdiction, the Park Service wanted to control the lake and a 300-foot strip of shoreline around its perimeter. Under this concept, the Forest Service would have administered only the national forest land outside that perimeter. After discussions between regional officials from both the Park Service and Forest Service, the Park Service compromised, suggesting that it control facilities to the water line and that the Forest Service operate those on the shore. [58]

Emphasizing the problem of fragmented and overlapping jurisdictions, Floyd Iverson, in consultation with the Washington Office, proposed a different division. He pointed out that the Park Service plan would create a national recreation area administered by the Park Service within the boundaries of a national forest, which would produce inefficient administration and result in public confusion. He proposed instead that the Forest Service administer those facilities within the Ashley National Forest and that the Park Service supervise those outside. At the same time he offered to cooperate with the Park Service and the States of Utah and Wyoming in the adoption of uniform boating regulations. A 1963 agreement essentially confirmed Iverson's plan for joint administration of the national recreation area.

In its lobbying, the Forest Service had an advantage. Under its multiple-use management philosophy, it had already begun planning and constructing recreation facilities in the area whereas Park Service plans were still on the drawing board.

As the Forest Service began construction of its recreational facilities in 1960, Park Service activities remained in the planning stage. Although it kept the Bureau of Reclamation and Park Service officials apprised of its progress and shared its plans with them, the Forest Service resisted efforts by the Park Service to slow down the construction of the facilities and to fit Forest Service operations within the Park Service master plan. Three reasons seem to have been uppermost. First, the Forest Service resented dictation by the Park Service on the type and location of facilities because its installations were part of a larger multiple-use management plan for the Ashley. Second, the Forest Service could not afford to build the expensive and elaborate facilities contemplated by the Park Service. Third, the rapidity of Forest Service construction gave the agency greater recognition from Congress and the general public. [59]

|

| Figure 87—Aerial view of Flaming Gorge Reservoir and National Recreation Area. |

By 1968, joint administration of Flaming Gorge seemed unwieldy, and both the Agriculture and Interior Departments concluded that sole administration by the Forest Service would be preferable. In this connection, it seems probable that the perception of the general public and elected officials that the Forest Service would manage the area under multiple-use rather than single-use principles helped rally support for Forest Service management. [60] Both the Senate and House reports on Flaming Gorge emphasized the permission granted for hunting and mining. The Senate Report also specifically mentioned the continuation of grazing. Although recreation was to be the primary activity in the national recreation area, the 1968 act allowed multiple-use management to continue. In addition, the Federal Government expected to save money on operation costs by using the Ashley's administrative structure and by having only one agency involved. [61]

In Idaho, the Forest Service cooperated with the Park Service in the investigation of the Sawtooth Mountain area, a scenic and recreational jewel on the Sawtooth, Boise, and Challis National Forests, The Forest Service begin multiple-use studies in the Sawtooth Mountain region in December 1959. Since the area had long operated within the multiple-use management philosophy of the Forest Service, it included the Sawtooth Primitive Area and such diverse activities as logging, grazing, and mining. Recreation played an increasingly important role as visits to the area increased from about 65,000 in 1956 to 252,000 in 1960. [62]

Given the importance of the area and the interest in its recognition as a national park or a national recreation area, further study seemed warranted. [63] Under a January 1963 agreement between the Secretaries of Agriculture and the Interior, the Forest Service and Park Service undertook a joint study of the Sawtooth area. [64] The study involved Assistant Regional Foresters John M. Herbert and John A. Mattoon, Sawtooth Supervisor P. Max Rees, and many others in the Regional Office and the three national forests. The investigation included a joint historical report by Victor O. Goodwin, a forester assigned to the Humboldt River Basin Survey, and John A. Hussey, regional historian for the Western Region of the National Park Service. [65]

As the interagency study continued, Chief Cliff wrote Senator Church enclosing a draft bill which became the model for the future Sawtooth National Recreation Area. [66] Church introduced the Forest Service bill in April 1966, with the cosponsorship of his colleague, Senator Len Jordan. Reintroduced in subsequent congresses by Church and other members of the Idaho delegation, the Sawtooth National Recreation Area Act finally passed in modified form in 1972. [67]

The Forest Service was involved in the development of a number of other important recreation sites, some in collaboration with other agencies and others on its own. After the designation of City of Rocks as a national monument under Park Service jurisdiction in 1966, recreation visits to the adjacent portions of the Sawtooth increased. [68] Historic charcoal kilns south of Leadore on the Targhee drew 3,000 visitor-days of use during 1968. [69] The Challis withdrew the old mining town of Custer in 1966 for preservation as a historic site. [70] The Forest Service undertook the restoration of Tony Grove Ranger Station on the Cache to provide an example of the operation of a station during the 1930's—early in his career, Chief Cliff had been assigned to Tony Grove. [71]

Not surprisingly, demands for increasing recreation use conflicted with pressure to maintain relatively stable ecological conditions in the national forests. An example with long-range implications was the battle between the Forest Service and its allies in the environmental community on the one hand and the Utah State Highway Commission on the other over plans to reconstruct Highway 89 within the Cache National Forest in Logan Canyon. Initial construction, begun in 1959, destroyed considerable fish habitat and, in the opinion of many, lessened the esthetic quality of the canyon. Concerns about safety and speed motivated the highway department, but not everyone agreed with its priorities. [72] As planning for the road continued during the 1960's, Floyd Iverson spearheaded the region's insistence that the Bureau of Public Roads take values other than highways into consideration. Chief Cliff backed the region to the hilt. A considerable body of public opinion supported the region as well, which seems to have been decisive in forcing the Bureau of Public Roads to raise its standards.

Conflicts developed over the use of off-road vehicles. General policy of the Service was to prohibit cross-country or off-road vehicles such as jeeps, trail bikes, and motor scooters where they might "cause erosion, damage young timber and forage, impair recreation values, and adversely affect fish and wildlife resources," [73] Under these restrictions, such vehicles were not allowed in wilderness or primitive areas. Certain critical areas such as Alaska Basin on the Targhee and a number of trails on the Toiyabe were closed. In general, however, the Service believed that the forests had places for the backpacker, the horseman, and the off-road vehicle operator, to the extent that significant damage did not occur. [74]

Motorized vehicle restrictions were not universally popular, and some groups challenged the regulations by entering the Idaho Primitive Area with motorized vehicles. Arrested and fined $100, they appealed the conviction, arguing that existing laws did not authorize the Forest Service to do anything on the national forests except protect timber and secure favorable conditions for water flow. In upholding the regulations, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held that, while recreational considerations alone would not support the establishment of national forests, recreation activities were appropriate subjects for regulation therein. Citing the legislative history of the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, the court ruled that Congress had recognized this interpretation by authorizing recreation and wildlife resources as legitimate purposes for forest management. [75]

Another recreation problem resulted from the disturbances and damage caused in campgrounds by motorcycle riders. Most forests had regulations limiting such use, but some cyclists roared through the campgrounds disturbing people and chewing up the ground cover. Since Forest Service officers visited the camps infrequently, the offended campers had little recourse except discussions with the bikers, which were often fruitless, and the problem was never completely resolved. [76]

Off-road vehicles were not the only offenders in damaging fragile watersheds. In some cases, horses used by outfitters and guides grazed too heavily on critical areas. The Service tried to solve the problem on the Boise by bringing the outfitters into the grazing permit system, but some of them resisted. [77] On the Toiyabe in the mid-1960's, excessive garbage left by outfitters and their parties was a problem. [78] At least one outfitter on the Challis, in complaints similar to those voiced by the stockmen a decade earlier, charged that the ultimate aim of the Service was to drive them out of business. In response, the Forest Service emphasized the need to protect the land from excessive deterioration and damage.

The Idaho outfitters succeeded in securing the passage in 1965 of State legislation dividing national forest territory among various companies. Some national forest officers regarded this legislation as not binding on the Forest Service as it sought to dictate management policy without considering the other needs of multiple-use management. The forest officers did consult with State officials to try to work out satisfactory outfitter arrangements. [79]

It should not be thought that the forests conducted recreation management through ad hoc measures. In the early 1960's, each forest prepared a recreation management plan projecting expected short- and long-range recreational development needs through the year 2000. [80] Tn addition, the Federal Government provided general evaluation of recreation facilities through the activities of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission, which continued its activities into the 1960's. [81] On heavy recreation forests such as the Wasatch and Targhee, for instance, the position of recreation and lands staff officer was created to provide general supervision and coordination of these functions. [82]

At recreation sites with a large demand, the region provided visitor information services. These included interpretive trails, demonstration areas, vista overlooks, wayside exhibits, guided walks, campfire programs, and contacts by forest officers. By 1964, with leadership from Assistant Regional Forester Alex Smith (I & E) and Supervisors Jay Sevy and Max Rees (Sawtooth) and A.R. McConkie (Ashley), the region had a visitor center in operation at Redfish Lake on the Sawtooth, joint visitor information services (in cooperation with Bureau of Reclamation) at Flaming Gorge, and another visitor center under construction in the Flaming Gorge National Recreation Area, at Red Canyon on the Ashley. [83]

Congress moved in 1964 to try to alleviate the pressure for needed recreation funds through the passage of the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act. The fund derived from three main sources: a recreation user fee for designated areas, dedication of a 4-cent-per-gallon tax on pleasure boat fuel, and receipts from the sale of certain Federal and other property. Money from the fund was to be used to provide additional Federal recreational facilities as well as grants-in-aid to the States on a matching basis for recreational purposes. [84]

In 1965, the region, along with other Forest Service units, began to designate areas at which the recreation user fee would be collected. In the first year, the fee applied to a total of 430 sites in Region 4, including 58 percent of all campsites, and 84 percent of the family units. The region set the initial fee at 25 cents per adult per day. In addition, the region set group fees for larger areas and special charges for boat-launching ramps. [85] In lieu of the daily payments, patrons could purchase $7 Federal recreation stickers or Golden Eagle Passports that allowed unlimited entry to the fee areas for one year. [86] Congress allowed the authorization for the Golden Eagle to expire in 1970. [87]

The region noted some problems in operating the fee system. During the first year, on heavy recreation forests like the Toiyabe rangers noted some deterioration in campground maintenance because recreation officers had to spend additional time selling stickers and tickets. The large number of different tickets confused some patrons. Some dissatisfaction developed because officers visited camps only three times per week, allowing some patrons to use facilities without paying. [88] In several southern Utah communities, citizens resented paying the fees to use local Forest Service picnic areas that had been developed in large part by volunteers and local service clubs from the communities. [89]

|

| Figure 88—Skiing at Slide Mountain, December 1968. |

While camping and hiking continued to increase, the forests noted a particularly large jump in water-related recreation and in skiing. As a result, new boating and camping facilities were constructed at high-demand areas like Pineview Reservoir on the Cache, Island Park and Palisades Reservoirs on the Targhee and Caribou, and Nevada Beach on the Toiyabe. [90] Grand Targhee near Driggs, ID, and Teton Village in Jackson Hole, WY, became the sites of new ski resorts under special use permits, and many existing areas increased their lift capacities. [91] Avalanche studies continued at Alta. [92]

Special Use Permits

Perhaps the most controversial change in the administration of special use permits was in the development of national forest summer home areas. In 1961, the Caribou and Targhee advertised the availability of a limited number of summer home sites near Palisades reservoir. [93] In about 1962, the Intermountain Region published a booklet promoting summer home development and providing information on obtaining permits for lots and on the standards required for construction. [94]

By the late 1960's, the increasing demand for public recreational facilities such as picnic areas and campgrounds prompted the Forest Service to do an about-face on the promotion of summer home areas. Because of the public demand for recreational facilities, in 1969 the Service prohibited the opening of new summer home areas. [95]

Though such a blanket policy was a new departure, as early as 1934 the Service had begun to have homes moved from a few critically needed public recreation areas such as Fish Lake. Permittees who had to move were allowed to construct a new home away from the lake shore. The Fishlake National Forest gave current permittees life tenure with the understanding that, if they sold their homes or died, the new owner had to move the home from the lake shore. By 1984, only 7 of the original 60 homes remained. [96] Similar requirements were initiated for the Big Springs summer home area on the Targhee in 1959. Permittee appeals through channels reached the Chief, who sustained the forest supervisors' decision. Complaints are still being raised, however, through the Idaho congressional delegation. [97]

In 1964, under its multiple-use policy, the Forest Service began to raise fees for special use permits for recreational uses, on the ground that if alternative uses existed for such lands, permittees should pay fees reflecting the current market value of the property. This policy raised considerable opposition from summer home permittees, many of whom had occupied their lots for years and had come to consider them their own. Appeals resulted; permittees applied considerable pressure to the Service to rescind increases. In general, although fees were raised, they were not increased to the fair market value of the lots. [98]

While summer home permittees seem to have been most vocal in their opposition to fee increases, the policy also impacted group camps such as those for Boy Scouts, Campfire Girls, 4-H organizations, and church groups. The policy was not applied across the board, however; ski areas paid on a graduated rate system based on the income from the operations, rather than on the value of the land they occupied. [99]

Most significant, perhaps, as population grew and development in the Intermountain West became increasingly complex, the diversity of special use permits broadened. Groups, companies, and individuals secured permits for a great variety of uses including boat marinas, transmission lines, farming, beehives, radio transmitters, and even radar sites. [100]

Public Relations and Wilderness Areas

These various developments, particularly opening virgin timber stands for logging and use of range-watershed lands for livestock grazing, did not enjoy universal popularity. As the variety of groups interested in national forest use multiplied, the Service came under fire, especially from preservationists opposed to development on national forest lands. At the Fifth World Forestry Congress in Seattle in 1960, the Sierra Club distributed literature attacking the Forest Service. From the point of view of Sierra Club president David Brower and his successor J. Michael McCloskey, the concepts of multiple-use and sustained yield evoked images of unrestrained high-yield commodity production and use. [101] The Sierra Club officers were particularly concerned that the Forest Service, despite holding public hearings before designating new wilderness areas, based the designation of new timber sale areas on internally generated multiple-use management plans. In addition, in the Pacific Northwest—though not in Region 4—the Service at that time opposed study of some lands considered as potential national parks. [102] Some of the attacks may have been generated by internal dissent within the Sierra Club itself; the more militant wing under Brower eventually split off to form Friends of the Earth. [103]

Region 4 was able to work out many of these problems. [104] When Floyd Iverson became regional forester in 1957 he entered with a backlog of good will, which he generally maintained. Both the Salt Lake Tribune and the Deseret News, Utah's two major dailies, supported the Forest Service. Moreover, publishers John F. Fitzpatrick and John Gallivan and environmental editor Ernest Linford of the Tribune, together with editor William Smart of the News, were strong supporters.

In some cases, conflict resolution took place through informal meetings. For example, a conflict developed in 1968 between the Sierra Club and stockmen over use of the Bridger Wilderness. Regional officials solved the problem by bringing Ed Wayburn of the Sierra Club and Leonard Hay of the Wyoming Woolgrowers together for a pack trip in the wilderness. After meeting together and gaining mutual understanding, the two developed a liking for one another and were able to work out the disagreement.

In the early 1960's, Congress had under consideration a series of bills proposing the statutory establishment of wilderness areas. Written by Howard Zahniser, executive secretary of the Wilderness Society, and originally introduced by Hubert Humphrey and John Saylor in 1956, one of these bills finally passed as the Wilderness Act in September 1964. [105] The Forest Service opposed the proposed wilderness bill at first as an infringement upon the concept of multiple use. After the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act in 1960 gave specific recognition to wilderness as a multiple use, the Service provided strong support for the wilderness bill. After all, the bill basically confirmed existing administrative policy.

|

| Figure 89—Bridger Wilderness near South Fork of Boulder Creek Guard Station, 1966. |

Opposition to the bill centered in a group of western senators who objected on essentially two grounds. First, they considered it elitist legislation of benefit only to that minute proportion of the population with the strength and inclination to backpack or money to hire pack animals. Second, they feared that provisions of the act would retard growth by locking up resources needed for western development. [106]

After the passage of the Wilderness Act, the Service had little trouble accommodating itself to its provisions. The act provided that all national forest wilderness areas would remain under Forest Service jurisdiction. It converted to statutory wilderness all wilderness, wild, or canoe areas previously designated under Forest Service regulations. [107] It required the Agriculture Department to review all designated primitive areas within 10 years for possible inclusion in the wilderness system.

The major change inaugurated by the Wilderness Act was to give Congress the sole power to designate new wilderness areas. Under the law, the president might, however, add up to 1,280 acres to a primitive area at the time of his recommendation to Congress, provided it was part of an area of not more than 5,000 acres recommended for designation as wilderness. While the law required the Interior Department to review roadless areas within its jurisdiction for possible inclusion in the wilderness system, the same provision did not apply to the Agriculture Department. In effect, then, these provisions made it more difficult for the Forest Service to create wilderness areas within the national forests since their designation by administrative regulation as had been done as recently as the establishment of the Jarbidge during the 1950's and the reclassification of the Bridger, Hoover, and Sawtooth to wilderness in the early 1960's was no longer possible. [108]

This tightening may have come about because of opposition from a number of western legislators to such administrative discretion. During 1962 and 1963, the region had considered a number of de facto wilderness tracts for possible formal designation under administrative rulings. [109] In 1963, as Region 4 considered reclassification of the Sawtooth and Idaho primitive areas, the Idaho Legislature expressed to Congress its opposition to the creation of further wilderness areas in the State. [110]

|

| Figure 90—Utah Congressman Howard Nielson and Fishlake National Forest Supervisor Kent Taylor at Utah Wilderness dedication, Mirror Lake, August 1965. |

In addition, some features of the Wilderness Act have either been misunderstood or misrepresented in parts of the West. Although the act generally prohibited motorized vehicles in wilderness areas, it specifically authorized certain exceptions that might be perceived as nonconforming. Motorized vehicles could be used to control "fire, insects, and disease," grazing and hunting could continue, prospectors could still continue to hunt for minerals until 1984, and citizens might develop water resources and works including roads, reservoirs, and transmission lines, as "needed in the public interest."

Under provisions of the Wilderness Act, the Forest Service began a review of its primitive areas for possible inclusion in the wilderness system. A number, like the Idaho Primitive Area, were included, but the High Uintas Primitive area was excluded because of Utah officials' fear that it might inhibit the development of reservoirs or water transmission lines, despite specific provisions of the act that allowed such facilities. [111]

Wild and Scenic Rivers and National Trails System

In 1968, following the passage of the Wilderness Act, Congress passed the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act [112] and the National Trails System Act. [113] The Wild and Scenic Rivers Act designated 8 rivers, including the Middle Fork of the Salmon River, as part of the system and 27 rivers, including the Bruneau River and Main Salmon River below North Fork in Idaho, for study. The National Trail system designated four trails in Region 4 including the Continental Divide, Lewis and Clark, Oregon, and Mormon trails for study.

Wildlife

Much recreation in Region 4 both inside and outside the wilderness areas included big-game hunting. Three developments of importance in big game management during the 1960's are particularly worthy of note. First, the Forest Service and the State wildlife authorities finally reduced the deer herds to manageable size. [114] Second, the various forests began extensive programs of wildlife habitat improvement. [115] Third, close cooperation between the Forest Service and the State game authorities became a standard feature of wildlife management. [116]

Most notable, perhaps, were the habitat improvement projects, many of which were completed in cooperation with State game authorities. [117] A number of forests undertook successful experiments in eradicating and trimming mountain mahogany and aspen to eliminate the overgrazed and high-lined old growth and give the smaller plants a chance to establish themselves. [118]

Some of the techniques for habitat improvement resulted from research conducted under the auspices of the Intermountain Station. Observations of 225 species of shrubs and forbs over a 4-year period showed at least 30 to be useful for improving the quality of wildlife forage. Most promising seemed to be a natural hybrid of bitterbrush and cliffrose that retained the adaptability of bitterbrush and the evergreen habit of cliffrose. [119] On the Boise and Sawtooth, browse utilization transects were established on a number of districts, and other techniques were used for the analysis of forage utilization and mouse damage. [120]

|

| Figure 91—Running the Middle Fork of the Salmon River on a rubber raft. |

Another area of significant change came in the attitude toward certain types of wildlife that had previously been thought of as predators or had been given only minimal consideration in making decisions about wildlife management policy. In practice, these species had been subjected to near-eradication or habitat destruction. During the 1960's, Assistant Regional Forester D.M. "Mike" Gaufin was particularly concerned about bald eagle habitat, and the region together with national forests, particularly the Boise, cooperated with the National Audubon Society in studying the bird's habits. Part of the concern came from accumulations of pesticides, especially DDT, detected in the carcasses of dead eagles and in their eggs, which, it was believed, might have contributed to the decline in the population of these raptors. [121] Regional officers also were concerned about the endangered trumpeter swans that wintered in a number of places in the Intermountain Region, including Island Park, ID, in the Targhee and Jackson Hole, WY, in the Bridger-Teton. [122]

Though the Forest Service continued to cooperate with the Interior Department's Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife in the eradication of damaging predators including coyotes, bears, and cougars, some people became concerned that these programs had become too wide-spread and too indiscriminate. [123] To study the problem, Interior Secretary Stewart Udall appointed a committee headed by A. Starker Leopold of the University of California. The Leopold report, issued in 1964 and widely circulated in Region 4, focused particularly on coyote control, and especially the use of compound 1080 (sodium fluoroacetate) bait stations. The report indicated that, under proper management control, the 1080 stations had proved effective in coyote control. It cautioned, however, that the use of 1080 was entirely unjustified in programs of rodent control, because the carcasses of these animals were often eaten by birds and other animals including endangered species such as condors and grizzly bears. [124] Acceptance of the report by Secretary Udall led to the abolition of the Division of Predator and Rodent Control and its replacement with the Division of Wildlife Services headed by Jack H. Berryman, formerly a professor at Utah State University. [125] In conformity with the Leopold report, Region 4 prohibited its crews from using bait treated with 1080 for rodent control. [126]

Earlier, some Region 4 officers had had difficulty in controlling the indiscriminate use of 1080. In the early 1960's, for instance, Richard Leicht, opposed the establishment of 1080 stations on his ranger district on the Salmon National Forest. No sheep grazed on this district, and it bordered a wilderness area. Leicht said that Interior's Division of Predator and Rodent Control "fought us tooth and toenail" to keep the 1080 stations. "We had some real big rows with them," he said. "They even threatened to try to get me fired." Leicht finessed the threat by offering to give them the Chief's phone number and by working behind the scenes through a local wildlife club to secure public support. The predator division had the support of sheepmen on the eastern side of the Salmon in the Baker, Tendoy, and Leadore areas. Nevertheless, Leicht and his supporters succeeded in getting rid of the 1080 stations on two ranger districts. [127]

Moreover, forest officers came increasingly to realize that indiscriminate predator control could work at cross purposes with the desire to control the size of deer herds. Foyer Olsen indicated that personnel on the Dixie became particularly concerned about the decline in coyote and cougar populations, since research had shown that these two species helped keep the deer population in check. [128]

It was not long before it was decided that something had to be done to protect those species most in danger of destruction. The solution proposed came in the passage of the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966. This act confirmed Forest Service policy for the preservation of certain species such as bald eagles and trumpeter swans, and it also gave statutory protection to other listed animals, birds, reptiles, and fish threatened with extinction. [129]

Considerable concern also existed over destruction of anadromous fish habitat, especially on the Salmon River and its tributaries. The Salmon River was particularly critical, as it was estimated that nearly 30 percent of the salmon and steelhead entering the Columbia River originated in Idaho. [130] Moreover, studies had shown that dams constructed on the Columbia and its tributaries inhibited the movement of anadromous fish from the ocean to their spawning beds. [131] During the winter of 1964-65, a saturated soil mantle contributed to landslides, particularly on the South Fork of the Salmon River, Secesh River, Cow Creek, and Maverick Creek. These slides caused considerable damage to salmon spawning beds. As a result of the damage, Region 4 and the Idaho Department of Fish and Game undertook a cooperative study of the South Fork. [132]

These studies and others together with general concern about fish habitat led to stream improvement projects on the Salmon River and its tributaries and on a number of other rivers and streams in Region 4. Projects included spawn bed improvement and stream barrier removal and redesign. [133] Other projects to stabilize streambanks and make pools in the streams for the fish included the installation of structures such as gabions, deflectors, and anchor chains. [134] In some cases, the Service cooperated in poisoning trash fish to improve the habitat for trout and other favored game species. [135]

Watershed Management

Closely associated with stream damage and improvement was the broad concern over watershed management. Legislation culminating in the Water Quality Act of 1965 significantly impacted national forest administration in Region 4. Forest officers included hydrologic surveys and analysis, watershed surveys, and other measurement techniques in their multiple-use surveys. A number of the projects were carried out under special acts of Congress, particularly the Flood Control Act of 1944, the Pilot Watersheds Project Act of 1954, and the Small Watershed Program under Public Law 83-566 (often referred to as PL 566 or Small Watershed projects). [136]

In many of its watershed management activities, the Service coordinated its efforts with the Bureau of Reclamation. [137] Perhaps the best example of such coordination was on the central Utah Project, which affected the Ashley, Uinta, and Wasatch National Forests. The Central Utah Project involved impoundment of streams flowing into the Colorado River drainage and its trans-montane diversion via Diamond Fork and Provo River and into the Great Basin, for use in the urban area of the Wasatch Front and for central Utah agriculture. Since the flows of streams and conditions of watersheds within the boundaries of national forests were vitally affected, close coordination was necessary. [138]

As planning on the project had begun, the Forest Service prepared a preliminary report in 1951 analyzing anticipated impacts on the national forests. Though the Bureau of Reclamation began the project without first consulting the Forest Service, beginning in 1962 the Service worked closely with the Bureau, the Utah Department of Fish and Game, the Central Utah Water Conservancy District, and other agencies on planning and development of the project. Since the Central Utah Project office was located in Provo, after consultation with Uinta forest supervisor Clarence Thornock, the regional office transferred Elmer Boyle from the Sawtooth where he had headed the Sawtooth National Recreation Area to Provo to provide liaison between the Forest Service and Bureau of Reclamation.

In connection with the hydrologic and watershed surveys, soil surveys provided valuable information for future planning. [139] In 1964, the Service assigned a granitic soils study team made up of representatives of the Washington Office, Regions 4 and 1, and the Intermountain Station to investigate soil conditions of the Idaho batholith. [140] From this and other surveys, the Payette, Boise, and Sawtooth National Forests applied information to a wide variety of resource use and activity plans. [141]

Hydrologic surveys followed well-established forms. Based on the same principles as the timber reconnaissance or range allotment analysis, hydrologists surveyed a given area, estimating the amount of bare ground, litter, and vegetation. Using these surveys and weather records and basing prescriptions on the assumption of a hundred-year flood occurrence (flooding likely to be the worst in 100 years), they then estimated the potential runoff from particular areas based on soil types, slope, and other factors. [142]

As the soil and hydrologic surveys continued, regional officers factored results into planning. In 1965, Deputy Regional Forester William D. Hurst instructed personnel to revise subregional multiple-use management and other guides to include information from the surveys, to issue instructions on procedures for work on "proposed potential soil-disturbing projects," to call upon hydrologists or soil scientists where necessary, and to train personnel to deal with soil and watershed problems. [143]

In connection with watershed problems, the region provided technical assistance for various types of studies. In June 1963, for instance, James Jacobs and Robert Rowen accompanied Toiyabe forest personnel over critical parts of watersheds in the Reese River area, helping to formulate recommendations for watershed rehabilitation. [144] Salmon National Forest engineer A.R. Bevan produced a reconnaissance report on Dump Creek, which posed a particularly severe erosion hazard to the Salmon River. [145] Crews initiated stabilization projects like the one on the East Carson Road on the Toiyabe. [146] Specialists provided functional assistance, as in the work on various portions of the White Pine Ranger District of the Humboldt in 1969. [147] Crews worked on rehabilitating burns in the Truckee River Basin on the Toiyabe and on the Boise Front. [148] Erosion control projects were undertaken on a number of sites including the old Bridger sheep driveway on the Bridger and the Ferron Watershed and Joes Valley on the Manti. [149] Forest Service officers continued to work with the Weber County Protective Corporation and the Wellsville Mountain group in watershed rehabilitation on the Wasatch Front in Weber, Box Elder, and Cache counties in Utah. [150]

In 1960, the Service and other USDA agencies began river basin investigations. [151] One study team worked on the Humboldt River drainage in central Nevada. [152] A second team studied, on the Boise River, drainage of the Boise and Sawtooth forests above Arrowrock Dam in Idaho. [153] Another team, including representatives from four forests and the Soil Conservation Service, investigated the Sevier River in southern and central Utah.

Unfortunately, on the Sevier project, after a time it appeared to some of the Forest Service officers that Soil Conservation Service personnel were delaying the final report. Carl Haycock, who had headed the Forest Service group within the study team, retired rather than continue to face what he perceived as SCS intransigence. [154]

Many of the watershed rehabilitation projects produced positive results. Residents of Turnerville, WY, reported a large reduction of sediment in their culinary water after rehabilitation of Willow Creek on the Bridger. [155] Work on the West Fork of Elk Creek on the Targhee in Idaho reduced sediment in Palisades. [156] Most important, perhaps, the Davis County Experimental Watershed where Intermountain Station scientists had developed techniques for watershed rehabilitation and improvement, had proved its value in greatly reducing flood damage in Wasatch Front communities north of Salt Lake City. [157]

Nevertheless, watershed problems continued. Forest Service officials have indicated that while they "did an awful lot of watershed rehabilitation," they "made mistakes," largely because of a "lack of knowledge." [158] In southern Utah, they found that they could not contour trench the Mancos shales because they "would just slide away with you." The techniques developed on the Davis County Experimental Watershed did not work well in controlling wet-mantle or frozen-mantle floods. Under those conditions, the soil was already saturated or impervious so contour trenches and increased vegetation often would not prevent landslides or control runoff. [159] Shallow soils on top of bedrock did not respond well to treatment. [160] Fortunately, the techniques worked where they were most needed, in the relatively deep but overgrazed soils of the Wasatch Front and the granitic soils of the Idaho Batholith.

Timber Management and Watershed Damage

During the early 1960's, the Washington Office placed almost unbearable pressure on the region to meet the annual sustained yield allowable cut. Between 1956 and 1963 Forest Service researchers completed a comprehensive timber survey. The findings, published in 1965, indicated that the timber supply in the United States was probably adequate to meet public needs at least through the early 1990's. [161] By the early 1960's, the United States was actually growing 17 percent more timber than loggers were cutting. [162] As a result of supply exceeding demand, the actual cut on all national forest lands never reached the sustained yield allowable cut until a major push in 1966. [163] In Region 4 demand was so low that great expanses of timber—especially the lodgepole pine type—continued to deteriorate. In certain particularly vulnerable watershed areas, however, Region 4 experienced serious difficulty in controlling logging damage to the land and vegetation. The silting on the South Fork of the Salmon mentioned earlier had largely resulted from logging road construction as large trucks, each hauling 10,000 board feet of 34-foot logs, pounded the roads. In 1963, in response to Regional Forester Floyd Iverson's request, Chief Cliff appointed a team of Division Chiefs from Washington to look at severe problems on the Payette and Boise. Vern Hamre, later Regional Forester in Region 4, represented the Washington Office Division of Watershed Management on the team. After the report showed the almost unbelievably bad damage that Iverson had expected, he pressed for an immediate reduction in the allowable cut, but the Washington Office refused to grant permission. Instead, it issued "a minor cautionary report."

In the absence of Washington Office direction, under the circumstances, Region 4 moved ahead by appointing a team headed by soil scientist John F. Arnold to work out hazard classification, identify suitable locations for logging roads, indicate places where roads could not be built without unacceptable damage, and designate locations that "had to have specialized logging or no logging." [164]

Arnold, following the lead of Regional Engineer James Usher, indicated that cost-benefit relationships had to be considered in all road construction. Going beyond Usher, however, he argued that if the engineers could not assure the needed road stability under existing conditions, the project ought to be postponed until safe methods such as helicopter logging became economically feasible. Most particularly, engineers ought to locate and design any road for stability under the particular geologic conditions. [165]

In order to correct existing damage, engineers on the Boise and Payette, with regional office support, undertook a major road reconstruction project. To accomplish this they took out and improved drainage systems, put in silt filter traps on the downside of the roads, installed small debris basins and other structures to stabilize the still-eroding soil and to keep it from silting the river, and reseeded the fills with brome, orchardgrass, wheatgrasses, and timothy. [166]

As indicated previously, similar problems had developed on the Teton. [167] When Bob Safran returned to the Teton as supervisor in 1963, he found that the Service had increased the annual allowable cut from 5 million to 54 million board feet. Over the period between 1957 and 1960, the actual cut had averaged 3.7 MMFBM. In 1963, the cut was actually 12.8 MMFBM. [168] Both these figures were considerably below the allowable annual cut, but the 1963 cut was nearly 3-1/2 times the previous average.

Although ostensibly prepared according to multiple-use management principles, the allowances seemed to Safran to have been determined without reference to watershed, wildlife, range, and recreation values. Landslides and erosion had become serious problems, and outside consultants who were brought in to study the situation presented their findings on inadequacies to the Washington Office. Instead of offering to reduce the cut, however, Washington Office personnel thought both the consultants and Safran had overreacted to public sentiment.

Safran himself began to take action to resolve the problems, but ran into conflict with representatives from the regional timber management, particularly Assistant Regional Forester Joel L. Frykman. Recognizing the seriousness of the situation, Safran succeeded in going over Frykman's head to Floyd Iverson in his effort to reduce the allowable cut to protect other national forest values. [169]

Some have argued that Safran, Iverson, and others overemphasized these problems. Large areas of Region 4 continued to consist of overaged and deteriorating stands and patterns in timber management in Region 4 were not unlike those in other regions. As George A. Roether, currently staff director of timber management in Region 4 pointed out, cutting practices in Region 4 during the 1960's were "just about in step with the whole history of the country," in increased mill capacity, allowable cut, and other matters. "Clearcutting, for example, peaked in Region 4 in the 1960's, just like it did nationally." The changes, he believed, "can best be explained by the concerns that arose in the mid to late 1960's over the amount of clearcutting that the Forest Service was doing." [170]

While some might agree, the efforts on the part of Floyd Iverson and others to reduce the allowable cut in Region 4 generated internal displeasure and considerable conflict with representatives of the Washington Office. [171] In the Regional Office itself, Assistant Regional Forester Joel L. Frykman thought that the regional administration paid too much attention to watershed management. Somewhat dissatisfied, Frykman retired in the late 1960's to enter private practice as a consulting forester, and Marlin C. Galbraith, who replaced him, did not share Frykman's views.

By the late 1960's, conditions began to change. Fortunately for Floyd Iverson, many national and local conservation leaders strongly support the region's early attempts to put the brakes on timber harvest if other values stood in jeopardy. The timber industry was somewhat unhappy at the region's efforts to reduce the allowable cut, but they did not have the political clout of former years, perhaps because of the increased power of conservation organizations like the Sierra Club. Still, some public relations problems developed because of the inability of companies like Boise Cascade and Intermountain Lumber Company to get all the timber they wanted on the Boise and Salmon National Forests. [172]

Improving Technology and Timber Management

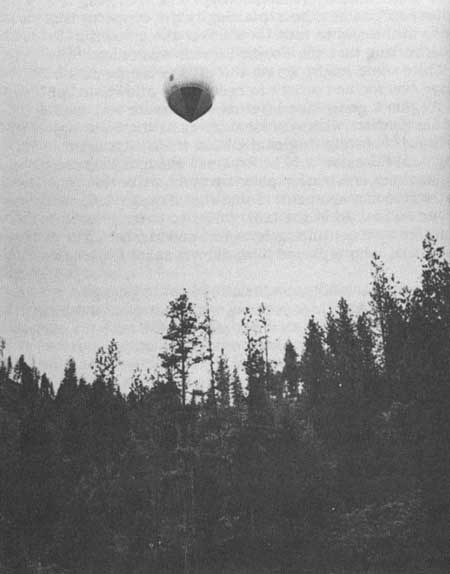

Given the revelations about unsatisfactory watershed conditions, it was almost inevitable that the Forest Service and the timber industry should attempt to help in reducing damage to the land by improving yarding technology. As early as 1959, the Sawtooth Lumber Company tried skyline yarding on the Boise. [173] By 1963, the Service reported that experiments in other regions had shown that helicopters could reach and remove otherwise inaccessible timber while at the same time substantially reducing damage to watershed and scenic values. Balloon logging in other regions permitted longer yarding distances and reduction of skidding damage and facilitated the protection of soil on steep and rough terrains. [174] Probably because of excessive cost, helicopter and balloon logging were not introduced on the Boise until the 1970's. [175]

As in the past, large areas of unlogged, overaged, and deteriorating stands remained in Region 4, especially lodgepole pine. Regional and forest officers wanted to step up logging in these areas and pushed for companies to buy such stands of timber. In 1962, the Idaho Stud Mill Company opened a million-dollar plant in St. Anthony to take advantage of Targhee lodgepole pine. Headed by Frances M. Gibbons of Salt Lake City and managed by William Semmler of St. Anthony, the company began logging operations with a 300 million board foot multiyear sale on the Moose Creek Plateau. The mill manufactured 2 by 4 studs and produced chips for shipment to a paper mill. The company achieved a high degree of efficiency in the woods by adopting various mechanized techniques. [176] By 1969, the company had begun to use a Beloit tree shear which debranched topped, and sheared off a tree in under 30 seconds. [177]

|

| Figure 92—Balloon logging on the Boise National Forest, late 1960's. |

Installation of the Idaho Stud Mill was one phase of a larger effort on the part of the regional administration and the forests to utilize overaged and deteriorating stands. Although the region was concerned over the abuse of areas like the South Fork of the Salmon River and the certain areas of the Teton National Forest, it was nevertheless committed to logging "safe" areas containing mature timber. Efforts to accomplish this goal included continued studies of aspen stands, publicity over the use of mountain mahogany in Nevada for charcoal, and consideration of the establishment of a pulp mill on the Green River in Wyoming.

Still, by the late 1960's, increasing lumber production for export led some leaders in the West to become concerned over what they perceived as a significant decline in the volume of available sawlogs, particularly from western national forests. In 1967, Idaho Governor Don Samuelson wrote Secretary of Agriculture Orville Freeman inquiring about the possible need for overcoming a log shortage in Idaho. In response, Freeman indicated that the volume of exports from some coastal areas had risen too fast to correct immediately, but that the Federal Government had already inaugurated talks with the Japanese. On the other hand, Freeman doubted that the problem would affect the Mountain West since large volumes of lodgepole pine and other species remained unharvested and deteriorating in southeastern Idaho and north Utah. [178]

Timber Regeneration and Timber Pests

As the demand for favored species like ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir accelerated, reforestation activities seemed increasingly essential. Reforestation activities in Region 4 centered in the Lucky Peak nursery on the Boise, which by 1965 had the capability of producing 11 million seedlings, with the potential of expanding to 30 million on adjacent land.