|

The Rise of Multiple-Use Management in the Intermountain West: A History of Region 4 of the Forest Service |

|

Chapter 8

Toward Stewardship and Multiple-Use Management: 1950 to 1959

Between 1950 and 1959, the administration in Region 4 built upon the patterns established earlier to try to gain better control over the resources under its stewardship. Perhaps Floyd Iverson best stated the goal in his commentary on the 1958 General Integrating Inspection of the Teton National Forest when he wrote that the program of the forest over the next few years "will be extremely important. It will set the stage for the transition of administration from a custodial status to planned integrated use of the forest's many resources . . . [through] multiple-use management planning." [1]

|

| Figure 69—Chester J. Olsen, Regional Forester, 1950-57. |

Personnel Changes and Management

With the death of William B. Rice in January 1950, Chester J. Olsen became Regional Forester. Born in Mayfield, UT, "Chet" Olsen graduated from Utah State Agricultural College. He served as a ranger and supervisor on forests in Nevada and Utah from 1919 to 1936, when he moved to the regional office to become assistant regional forester in operation, recreation and lands, and information and education (I and E). Known as an "able, persuasive conservationist," he concerned himself with such problems as destructive timber practices and grazing abuses. While maintaining a close friendship with nationally prominent conservationists like Bernard DeVoto, Olsen also ingratiated himself with many of the region's prominent civic and business leaders. An associate called him the "best I and E man in the Forest Service." In 1956, a panel of prominent citizens named him Utah's outstanding Federal employee. [2]

Olsen continued to serve until retirement in 1957 when Floyd Iverson replaced him. Born at Bieber, CA, Iverson grew up on a ranch. His father held a prior use grazing permit on the Modoc National Forest, and he had long been acquainted with the Forest Service. Iverson received a degree in forestry and plant ecology from the University of California at Berkeley. After serving as a ranger and forest supervisor in California, he moved to Region 6 as assistant regional forester in charge of range and wildlife activities. In 1952, he became assistant regional forester covering the same activities in Region 1. He came to Region 4 in 1955 as assistant regional forester in charge of range and wildlife management. [3] Iverson continued as regional forester until his retirement in 1970, earning a reputation as a quiet, resolute, and capable resource manager.

The selection of Floyd Iverson is consistent with a pattern in major Forest Service administrative appointments that has continued to the present time. Since the late 1950's, experience in more than one region and often in the Washington Office has generally been requisite to appointment as regional forester, and, in some cases, to major staff positions. Region 4 regional foresters before the late 1930's had all worked outside the region; thus, in a sense, Woods, Rice, and Olsen constituted a temporary anomaly. Both their predecessors and their successors spent large portions of their careers elsewhere. [4]

|

| Figure 70—Floyd Iverson, Regional Forester, 1957-70. |

Moreover, employees could cut themselves off from advancement in the Service by refusing to accept transfers, either because they preferred to live in a particular area or because they did not believe the transfers would help their careers. Ivan Sack, for instance, refused a transfer to become supervisor of the Boise National Forest because he wanted to live in Nevada. [5] Kenneth Maughan declined a transfer from a ranger's position to become assistant regional landscape architect, because he believed there would be little chance of advancement in the position. He was not offered another position and completed his career as a ranger. [6]

During the 1950's the operations of the Forest Service elicited some interest among outside observers. A good example is Herbert Kaufman's The Forest Ranger, [7] a study of the grass roots of national forest management. Kaufman identified the diversity of the rangers' management responsibilities that made them "executives, planners, and woodsmen." [8] With considerable insight, he argued that from the point of view of the ranger, Forest Service organization appeared "as an inverse pyramid with himself at the apex." [9] The ranger had to be a generalist who devised plans on the basis of prescriptions and instructions from line and staff officers in the regional and forest supervisors' offices and mediated the implementation of these plans with forest users. This position often led to conflicting demands on the ranger's time and abilities, particularly when forest users abused the lands or resources under permit. [10]

A number of conditions also militated against a uniform resource management policy. Each ranger carried a particular cultural baggage containing his individual beliefs and notions about resource protection, management, and use. Many rangers had considerable empathy with the problems of ranchers and loggers, among whom they often had spent their early years. The deliberate decentralization of Forest Service administration, which made the rangers "kings of their own domains," reinforced these attitudes. [11]

At the same time, other forces operating within the Service pressed for considerable uniformity of management practices. These forces included the statutes governing policy, the Forest Service Manual, which by 1960 consisted of seven looseleaf volumes, budgetary control by superiors, management plans which required their approval, and supervisor resolution of differences of opinion between his staff and the line officers. [12]

In addition, the Forest Service had means of detecting and discouraging deviation. These included reporting in various forms, keeping and analyzing official diaries, reprimands and sanctions, transfers, and, most important, inspections. Inspectors—ordinarily staff officers from one level above—were instructed not to "waste time on details already being accomplished to a satisfactory standard." Although inspectors were encouraged "to be alert to outstanding accomplishments," the reports were to be "frank and unvarnished." Forest officers were expected to respond to and correct deficiencies detected in these inspections. [13]

Most important, the Forest Service spent considerable time and energy in creating an atmosphere designed to help its personnel accomplish the Service mission. Like the Marine Corps, the Forest Service sought "a few good men," and it advertised for and selected those who could commit themselves to its ideals. Following entry into the Service, training programs helped in the initiation of employees and the building of an identification with the organization. Training included practical lessons in commitment to the interests of the agency, including a willingness to accept transfers for the good of the organization. The rewards of loyalty and hard work appeared in the respect shown employees at all levels: forest supervisors and regional foresters sought and seriously considered the advice of rangers and staffs in making policy decisions. [14]

Moreover, dedication to the agency was voluntary. During the 1950's, professional forestry schools produced many more foresters than the Forest Service could absorb. Since many positions were available at higher salaries in industry, the Service did not hire or keep a majority of the graduates. The evidence seems to indicate that ordinarily only the most dedicated joined and stayed in the Service. [15]

Although Kaufman does not say so, many of his generalizations about rangers could as well apply to other line officers, particularly forest supervisors and regional foresters. They, too, were subjected to the contradictory demands of public relations and resource management, their offices were inspected, and they participated in periodic meetings and training. If anything, their positions were even more difficult than the rangers'—they stood as if at the neck of an hourglass, with sand flowing first in one direction, then the other, as the glass was turned. In their positions they had to work to maintain equilibrium between the competing demands of Washington Office staffs, rangers, and the public.

Inspection

Inspections, especially General Integrating Inspections (GII's), provided an important means of checking on performance and conformity. This is evident from the GII of Region 4 in July 1955, the third GII for Region 4, succeeding those of 1939 and 1948. From July 13 through 30, Howard Hopkins and Lloyd Swift of the Washington Office inspected three of the region's forests in detail and eight others in a more cursory way. They also spent 3 days in the Regional Office and 2 days at the Intermountain Station. [16]

Most important, the Region 4 GII was a process rather than an event. The regional forester responded to and undertook correction of deficiencies noted in the report and provided information on the solution to problems. Correspondence specifically addressing the means of correcting problems noted in the 1955 report continued through the remainder of Chet Olsen's term and into that of Floyd Iverson, at least through 1961. [17]

Extremely thorough, the report covered all functions. Emphasizing what the inspectors perceived to be the major functions—watershed, range, wildlife, timber, and recreation—it included substantial sections on public relations, research, and inspection procedures. The report spent less time on protection, administration, safety, land management and ownership, engineering, quarters, the youth rehabilitation program, fiscal control, and mining. [18] Comments were both general and specific, addressing those areas in which the region was doing exceptionally well and those where improvement was needed.

Region 4 inspections, at 7- to 9-year intervals, came less frequently than the regional GII's of national forests, which were generally every 3 or 4 years. As in the regional GII's, followup was expected, and supervisors were required to report periodically on their success in solving problems noted in the inspections. [19]

Superior officers also conducted inspections of their specific areas of responsibility. Called "functional inspections," these provided thorough inspections of one function such as timber or fiscal management.

Planning

In addition to inspection, the Service gave considerable attention to adequate planning of work. The motivation for careful planning had at least two roots. Forest Service ideals had always emphasized careful planning based on scientific research. In addition, a congressional investigation in 1950 that faulted the Agriculture Department for poor planning on a number of projects led to instructions from Chief Lyle F. Watts calling specifically for preparation of careful forest management plans and for followup to see that the plans were implemented. [20]

This emphasis on planning led to the development of an annual regional program of work begun in 1953. A committee on the program of work consisting of selected regional staff officers and forest supervisors was appointed. Committee members assisted in establishing annual and long-range goals, planning, and reporting. [21] The program of work included sections dealing with each major division, in addition to a general statement from the regional forester. [22] Each forest was to cooperate by developing its own program of work and reporting progress at the end of the year. [23]

In line with instructions from the Washington Office, the annual report also emphasized cost-saving measures taken at the regional level and on the various national forests. In 1953, for instance, one forest saved $9.50 per cubic yard by having premixed concrete delivered to jobs rather than purchasing the materials and mixing it at the site. Another forest saved $175 by "rehabilitating" 25 used paint brushes. [24]

Multiple-Use Management and Increased Personnel Complexity

At the same time, Region 4 began to emphasize the need for multiple-use planning. Region 5 had moved ahead with multiple-use planning more rapidly than Region 4, and while Ivan Sack was supervisor of the Toiyabe in the early 1950's, he was invited to participate with Region 5 in the development of a Sierra Nevada subregional multiple-use plan. After that experience, Chet Olsen asked Sack to present the concept of subregional multiple-use plans to the forest supervisors at a meeting in Ogden in 1956. Some expressed skepticism about such plans, but, after Floyd Iverson became regional forester in 1957, the region moved ahead vigorously in preparing them. [25] In addition, following an approach adopted in Region 2, some of the Region 4 forest supervisors appointed multiple-use advisory boards representing a variety of interests, such as education, water, recreation, timber, livestock, business and industry, labor, the general public, women's organizations, and wildlife. [26]

By late 1959, the region had begun to publish multiple-use management guides for each of the major subregions. The guides provided essentially a context within which each forest was expected to prepare its multiple-use management plan. The guides outlined the general Forest Service missions, such as timber, grazing, water, and recreation management, as they related to each subregion. General comments were then provided on various altitude and influence zones. Zones defined were: crest, middle slope, lower slope, travel influence, and water influence. The subregional guides also provided for the inclusion of special zones, such as a wilderness area or research site peculiar to a particular forest. The basic objective of the guides was "to assist in correlating use and production of national forests for maximum over-all benefit to the public," and to provide direction which would result in "consistency in policy between units and successive administrators where similar situations exist." [27]

Reversing the trend apparent in World War II and afterward, the Service came under more pressure in the 1950's to pursue its work by contract with private businesses rather than force account. In 1951, Olsen indicated that they had been "getting considerable criticism, especially in connection with our reseeding, range fences, and other work, to the effect it is costing us more to do the job by force account than it could be done by contract." He suggested that various divisions might have overlooked the use of competitive bidding on insect control, slash disposal, forest rehabilitation, and road construction, and asked for the opinion of various staffs on that possibility. In general, the assistant regional foresters responding indicated that on most jobs force account seemed most desirable. The exceptions were large construction projects and other large undertakings where adequate information on appropriations was available to allow advertising for the 90 days required by regulations. [28]

In attempting to deal with budgetary problems, the region faced a number of conflicting pressures. At the same time that demand intensified to increase the sustained-yield cut, gain control of overgrazing on forest rangelands, and meet demands for recreation facilities, budgetary constraints and manpower limitations were putting enormous pressure on the service. The region stood in essentially a no-win situation. If it did not meet the demands for resource use, it came under censure, and if it spent too much money or tried to utilize current employees through overtime, it was in danger of exceeding its budget. [29]

The problem of meeting these conflicting demands and maintaining employee morale at the same time was the subject of considerable discussion in the region. The focus of the supervisors' and division chiefs' conference in 1951, for instance, was on human relations. In his cover letter sent with the preliminary material, Olsen wrote that "in our whole job of National Forest administration we are dependent for success on our abilities in human relations and the degree of our success is measured by the amount of those abilities we possess." [30] Some of the other conferences during the decade emphasized similar themes. The 1954 conference focused on "Executive Development," and the 1958 conference was entitled "Progress through Cooperation and Teamwork." [31]

Measures taken to deal with employee management included a continuation of the emphasis on work-load analysis begun during the late 1940's. On the Targhee National Forest in 1957, for instance, Supervisor Gordon L. Watts launched an investigation into correlated work-load standards of all ranger districts after the regional office raised questions about the load of three districts. Each district was intended to have a minimum 2,700-hour load; the review showed all at or above the standard. [32] Moreover, Watts recommended upgrading the Ashton district to a GS-11 position because, while the work loads in timber management and fire control were below the national average, those in range management, wildlife management, soil and water management, and recreation were above average, with range management and recreation 63 percent and 50 percent above the average. [33]

With the increasing demand for multiple-use management came concurrent pressure to provide a more professional approach to solving problems on the national forests. Robert Safran dates the change to 1957. Before that time the relatively large staffs on Boise and Payette had been exceptions. In 1953, when Safran went to the Teton, the forest had a supervisor, assistant supervisor, a roving forester, four rangers, an administrative officer, a typist, and a maintenance foreman. After 1957, however, the forest created staff positions for hydrologists, soil scientists, wildlife specialists, and others. [34] In 1959, when Don Braegger moved to the Cache National Forest, that forest had recreation, timber, and wildlife staff as well. [35] Other national forests expanded similarly.

Previously, when the agency hired a married ranger it actually got the services of two for the price of one as the ranger's wife generally did various jobs around the district. Ed Noble remembered his service in the late 1940's and early 1950's as a ranger on the Salmon and Minidoka: "If you couldn't type and your wife couldn't type, you were in trouble," Wives were "classed as collaborators, which entitled them to no pay," but since they "did have regular appointment papers" they could get a "driver's license so they could drive the government equipment." Noble's wife "would run the district, answer the phone and the radio," while he was out on week-long pack trips. If a fire broke out, she would "get some people to go fight the fire." Because he could not type very well, he would "go in and babysit while she did" his typing. [36]

By the mid-1950's, this situation had begun to change on ranger districts on some of the larger forests. Noble transferred to the Boise and felt he was "kind of in seventh heaven." Because of the large timber sales, clerks would be hired for the summer on ranger districts, to answer the phone and radio and do needed typing. The press of business, however, eventually necessitated hiring full-time clerks for the rangers. [37]

In the regional office the number and diversity of staff specialists increased materially as well. In 1956, Ollie C. Olsen came to the regional office as a soil scientist in the division of engineering. The following year A. Russell "Bus" Croft, who had transferred from the Davis County Experimental Watershed to the Regional Office in administration in 1951, was asked to head a new group in soil and water management; Olsen came into this group. [38] Before long, hydrologists joined the staff as well. The regional landscape architect's office expanded, and its duties were increased. [39]

Moreover, the emphasis in the supervisors' conferences shifted from personnel to resource management. With the increased concern over various functions, the 1956 conference emphasized "Making Multiple-Use Management Work!" While the 1958 meeting focused on cooperation and teamwork, considerable time was spent on range management, timber management, recreation, and relations with State and Federal agencies whose work affected the Forest Service. [40]

Interagency Cooperation and Public Relations

Successful resource management included inter-regional cooperation. By the 1950's, for instance, a number of people had become concerned about the protection of Lake Tahoe, which lay in Regions 4 and 5. As a result of the work of newspaperman Joe McDonald for the Fleischmann Foundation and the cooperation of people such as Supervisor Ivan Sack of the Toiyabe National Forest, casino owner Bill Harrah, and Barney Lowe of Sierra-Pacific Power and Nevada National Bank, the Lake Tahoe Area Council was organized. The council concerned itself with water quality, land use planning, and multiple-use management. With the creation of the Lake Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, in the 1960's, both Nevada and California appointed representatives, and Nevada Governor Paul Laxalt appointed Sack his representative on the agency. [41]

An important part of any successful program was the public relations aspect. Called I and E within the Service during the 1950's, this aspect of the program included working with local civic and business groups and concerned local, state, regional, and national political figures, finding and keeping friends in conservation organizations, and developing and maintaining good relations with various user groups. As the functions of the Service became more complex, interaction with various State and Federal agencies became increasingly important.

Chet Olsen was a master at public relations. During the 1950 election campaign he made it a point to meet with Wallace F. Bennett, Republican candidate for the Senate, who had been quite critical of Federal programs. Bennett admitted "a keen interest but lack of knowledge of many" of the Forest Service's problems. "He stated he would be very pleased to make a trip over some of the forests during the ensuing year." Bennett admitted "that he might have made some statements that were in error concerning the administration of the national forests, and that he was willing to learn more about them." [42] By July 1951, correspondence passing between the two, who had not known each other before October 1950, was addressed "Dear Wallace," and "Dear Chet," and Senator Bennett presented testimony supporting additional appropriations for the Forest Service, calling the forest "the poor man's playground." [43]

Forest Boundary Alteration and Consolidation

During the 1950's, alterations in national forest boundaries continued for essentially the same reasons as during the previous decade. That is, the work load on some of the forests simply was not great enough to justify national forest status and consolidations resulted. [44] Major forest dissolutions included the 1957 division of the Nevada in which southern Nevada went to the Toiyabe and central Nevada to the Humboldt. [45] In 1953, the Minidoka and Sawtooth National Forests were combined, with headquarters at Twin Falls. [46]

The major problems in such divisions and combinations were the public relations difficulties associated with the elimination of a supervisor's office. In the cases of the Sawtooth-Minidoka consolidation and the Nevada division, supervisors' offices at Halley and Burley, ID, and Ely, NV, were made into ranger district headquarters. In general, the regional and forest officers succeeded in preparing the public to such a degree that they accepted the changes with little difficulty. [47]

Other changes included several interforest transfers. These came about to adjust the work load between forests or for administrative rationalization. In 1952, for instance, the Santa Rosa division of the Toiyabe was transferred to the Humboldt. [48] In this case, the Toiyabe had a much larger work load than the Humboldt. [49]

Several other forest boundaries also were altered, including that between the Teton and Targhee, [50] and those separating the Uinta, Wasatch, and Ashley. At the time, Mount Timpanogos, which was within eyesight of the Uinta National Forest Headquarters at Provo, was in the Pleasant Grove district of the Wasatch. Moreover, the ranger district headquarters at Duchesne was much closer to the Vernal headquarters of the Ashley than to Provo, but was a division of the Uinta National Forest. James Jacobs, then Uinta National Forest supervisor, pushed for a boundary change, and the regional office adjusted the boundaries between the three forests, transferring the Pleasant Grove ranger district to the Uinta and the Duchesne district to the Ashley. [51] Other important land status actions included the completion of the land-for-timber exchanges with the Boise-Payette Lumber Company between 1956 and 1960, [52] the receipts act purchases of watershed lands, especially in the Wasatch and Sierra Fronts of Utah and Nevada, and the retention of the southern Idaho resettlement administration project.

Grazing Issues

The broadly based sentiment against single use that was evident in the derailing of Congressman Barrett's Wild West Show in 1947 continued during the 1950's. An early example was the passage of the Granger-Thye Act in 1950. The original bill was drafted by the Forest Service and sponsored by Congressman Walter K. Granger of Utah and Senator Edward Thye of Minnesota, at the request of Assistant Chief Forester Raymond Marsh. [53] During the Barrett and McCarran hearings considerable misinformation had surfaced about Forest Service policy, particularly the charges that the Service did not consult with permittees, that it was not interested in revegetating overgrazed lands, and that it wanted to eliminate grazing from the public lands.

The Granger-Thye Act basically contradicted such charges by codifying existing Forest Service policy. It specifically authorized cooperation between the Service and stockmen in improvements on grazing lands, the expenditure of portions of the receipts from grazing fees for range improvements, the issuance of 10-year grazing permits and the establishment of grazing advisory boards. [54]

The Forest Service had done all these things for years. A portion of the receipts from grazing fees had been used for range improvements as early as 1924. [55] The Anderson-Mansfield Act of 1949 had reinforced this practice by authorizing the reseeding of 4 million acres of range. Even though advisory boards had been in existence for decades, if the perception of the Humboldt supervisor in 1950 is any indication, the permittees were less than enthusiastic about the Granger-Thye authorization because it simply acknowledged the status quo. What they wanted, he said, was "authority to sue in court where the managing agency does not happen to see eye to eye with them." [56]

Through certain western congressmen, stockmen continued to press for legislation that would give them greater control over grazing permits. As before, principal opposition centered in those who favored Forest Service regulations to protect watersheds and manage big game. [57] At the time, the livestock interests seemed to have considerable power; but, in retrospect, it is clear that the combined opposition from cities and towns anxious to preserve their watersheds, from sportsmen's groups and their allies in the business community, and from conservation organizations was powerful enough to sidetrack such legislation.

The inability to assure their tenure as a right on the public lands did not set well with livestock interests, and they continued to press for increased stability by opposing reductions in numbers. In 1950, as a gesture of conciliation, Secretary of Agriculture Charles F. Brannan ordered the Service to abolish its policy statement allowing reductions for distribution to new settlers. In practice, this change was more cosmetic than substantive since reductions for distribution had been largely nonexistent since the 1930's. The policy had, however, remained on the books as a vestige of the economic democracy of the Progressive Era and had served to irritate permittees. [58]

|

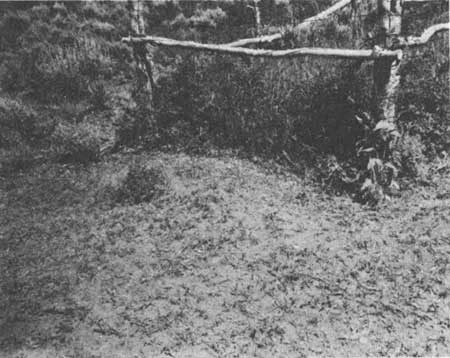

| Figure 71—Forage utilization basket on allotment in Upper Big Creek, 1958. |

More serious were stockmen's complaints about transfer reductions and reductions for range protection. After hearings in 1950, the Washington Office's National Forest Advisory Council, which had been reconstituted from the National Forest Review Board established in 1948, recommended retention of transfer adjustments, but suggested clarification of procedures. [59] This recommendation did not satisfy stockmen. After the inauguration of President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953, Montana Congressman Wesley D'Ewart introduced the Uniform Federal Grazing Bill, designed to provide continuity of grazing privileges, which would have effectively eliminated transfer reductions. Various conservation and business groups opposed the D'Ewart bill, and Congress killed it. Nevertheless, stockmen threatened to have the Forest Service budget slashed if transfer reductions continued. Chief Richard E. McArdle, who had replaced Lyle F. Watts in 1952, recognized that although Congress had not agreed to the D'Ewart bill, it might indeed reduce the budget, and agreed to eliminate transfer reductions, except when they were needed for range protection. [60]

With the elimination of transfer reductions for distribution, it seemed reasonable to adopt the policy of giving permittees the full benefit of improvements on their allotments. In 1953, the Service ruled that where carrying capacity improved through permittee cooperation in range improvement, the permittee was to be given the benefit of the increases. [61]

In 1953 the Service also recodified its appeals procedure. Appeals were taken from the ranger to the forest supervisor, through the regional forester to the Chief of the Forest Service, and finally to the Secretary of Agriculture. In lieu of the supervisor, the appeal might go to the grazing advisory board. If not satisfied with the board's recommendation, the appellant might continue through Forest Service channels. At the Agriculture Department level, a National Forest Advisory Board of Appeals was established of qualified Federal employees from outside the Forest Service to advise the Secretary on appeals from the Chief's decisions. From the Secretary, dissatisfied apellants could take their cases to the Federal courts. [62]

These changes were procedural, not substantive. They did not address such problems as numbers of livestock and seasons of use, grazing fees, and competition between big game and livestock. The grazing fees were not a source of general complaint during the 1950's. As we have seen, such fees were derived from a base put into effect in 1931 and determined by fluctuations in the market price of cattle and lambs. In 1953, the national forest grazing fee was substantially below that paid for comparable private range, but higher than BLM rangeland and most State-leased land. [63]

The oversupply of big game continued to rankle stockmen, but they were most concerned about reductions in numbers of livestock and in length of grazing season. [64] The basis of the dispute was the stockmen's demands that the Forest Service determine the condition of the range by the condition of the animals leaving it rather than by the condition and trend of the soil and the plants growing on it. Most important from the Service's point of view was the introduction of the Parker three-step method, which Region 4 had adopted by 1949. The three steps consisted of: (1) periodic collection of data at permanent benchmarks on representative sections of the range (the transects); (2) classification of, condition of, and estimation of trend on range units (analysis of data); and (3) establishment of permanent photopoints. [65]

Such systematic estimates of trend were necessary because of the conflicting perceptions of changing conditions of the ranges obvious in interviews collected to document trend. Memory tends to be highly subjective, and the Forest Service sought an objective measurement of trend under the assumption that condition of the soil and plants provided the best measurement of the quality of grazing lands. [66]

By the 1950's the Service had data that suggested changes over time in the composition of vegetation. On the Grantsville Division of the Wasatch, for instance, maps made in 1921 revealed a particular configuration of pinyon-juniper type. In 1941, aerial photographs showed that the pinyon-juniper had expanded. Aerial photographs in 1959 and 1960 showed continued pinyon-juniper encroachment on grass and brush lands. [67]

Involved in the process of allotment analysis were a number of systems for trend measurement. These included the 250-foot photoplots introduced in 1943 by Lincoln Ellison and Walter Cottam, with photopoints identified by iron pegs. The region stopped installing new photoplot transects in 1951, but asked rangers to continue to make followup measurements, since they were perceived as "effective in showing visible proof of trend in vegetation or soil." [68] Other earlier measures to determine trend included enclosures (called exclosures by the 1950's), quadrats, species plots, and browse study plots. The establishment of all of these methods had been discontinued by 1940, and line intercept transects were laid out as an experiment on the Teton and old LaSal between 1940 and 1943. [69]

The Parker transects were 100 feet in length. They were placed in key range areas to measure average range condition by charting the progress of key plant species over time. In measuring, the range conservationist would drop a 1-inch or 3/4-inch hoop every foot along the transect, and the plants hit were identified and recorded. A point near the beginning of the transect, at which photographs were taken, was marked with iron stakes. In addition, the conservationist would clip and weigh the vegetation at points along the transect and estimate forage production and the amount of grazed land. During the 1950's, another system of analysis was used in which similar transects were established and a hoop 13.27 inches in diameter was dropped at intervals with the hits on plants recorded. [70]

Results of such analyses were recorded, analyzed, and filed. The documents produced for each allotment included a "Range Condition and Trend Map," a "Range Allotment Record and Analysis" (which superseded in 1954 the "Grazing Allotment Analysis" (summary sheet)), and an "Allotment Action Plan" dated and signed by the forest supervisor and the district ranger. [71]

In implementing this program, the regional office conducted periodic range management inspections. In inspecting analytical procedures, range conservationists from the regional office went to the ranger districts and reviewed the transects and records to determine the validity of the studies and to provide further advice and training where necessary. [72]

After the inauguration of the Parker three-step method, the attitude of forest officers might best be summed up by a comment of Toiyabe Forest Supervisor Ivan Sack. In his 1951 annual report he said that "stocking to proper grazing capacity on each range is our objective, but material accomplishment will require several years and depends upon sufficient basic data." [73]

While the measurement of trend by charting the condition of the land and vegetation might have seemed threatening to stockmen, the service also offered those cooperating a portion of the income from grazing fees for range improvements. These improvements included projects such as fences, corrals, water developments, rodent control, weed eradication, and range reseeding.

By 1956, the region had been involved in reseeding projects for 15 years, and revegetation policy took the results of those years of experience into consideration. Reseeding was to be allowed only on allotments devoted to single use: common use allotments (those with sheep and cattle grazing together) were not eligible. Preference was given to those allotments with the best cooperation from permittees and where there was a "guarantee of . . . [permittees] resuming use not to exceed the carrying capacity of the treated unit or allotment." Large areas were to be treated first. Permittees were encouraged to participate financially if possible. Proper measures were required to prevent destruction of seedlings by rodents and big game. Spraying of herbicides was strictly controlled and allowed only where desirable species could not reestablish themselves through natural protection. Preference in reseeding was given to accidentally burned areas. [74]

With the passage of the Anderson-Mansfield Act in 1949 and the codification of the customary policy of using money from grazing fees for reseeding in the Granger-Thye Act in 1950, the Washington Office launched a projected 15-year range improvement program. Within that time, the Service expected the bulk of the work to have been completed. [75]

Service employees found the permittees and livestock associations generally cooperative. The Santaquin Association, for instance, "held all their cattle off the range for three years" while the reseeded area established itself. The largest project was under Supervisor Albert Albertson on the Dixie National Forest in John's Valley near Widtsoe, UT. A number of areas were seeded by airplane. Recent observers have indicated that the reseeding projects "materially increased forage production on many areas throughout the region." [76]

Success of the reseeding program depended upon research information available by the 1950's, which had demonstrated those species better suited to particular geographic and climatic conditions. As Ed Noble pointed out, in canyon bottoms they could use brome, orchard-grass, timothy, and bluegrass. Crested wheatgrass did well in dry areas. Although crested wheat was not the most desirable grass, since it grew in bunches and robbed the soil of moisture to such a degree that little could grow between the clumps, it was exceptionally hardy, its seed was readily available, and it produced palatable forage. [77]

Results of these efforts are evident from the annual range revegetation report for 1955, which seems to have been typical for the decade. During 1955, the region spent a total of $262,609, allocated in amounts ranging from $42,360 on the Dixie to $200 on the Wasatch. The appropriation allowed the region to rehabilitate 30,175 acres, bringing to nearly 396,000 acres the total treated to that time. Of the acres treated in 1955, 19,000 were reseeded. Competing plants were removed on 11,000 acres. This was only a drop in the bucket, however, since forest officers estimated that a total of 1.9 million acres needed to be rehabilitated. Between 1950 and 1955, the region had rehabilitated an average of 24,554 acres per year. To complete the work in the 15 years projected would have required treatment of 131,905 acres per year. The region would have needed an estimated $1.5 million per year. Clearly, at the 1955 rate of appropriation, it would have taken far more than 15 years to complete the projects. [78]

With the data gathered from systematic range allotment analysis, the region moved ahead on reductions in livestock numbers and grazing seasons to improve the condition of the ranges. In general, the procedure followed was for the ranger, supervisor, and their staffs to analyze the data, then arrive at a course of action. The ranger would then invite members of the stockmen's association to ride the allotment. At that time, he would point out the problems, listen to their point of view, tell them of the forest's proposal for dealing with the difficulties, and consider any counter proposals. Ordinarily, he would follow this meeting with a letter indicating his decision. [79]

|

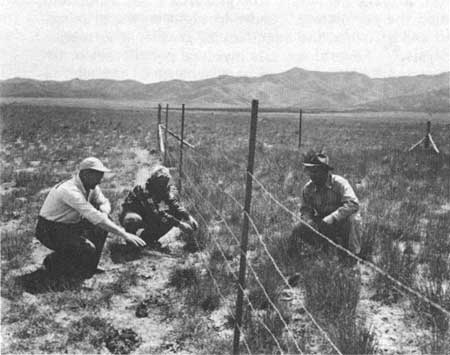

| Figure 72—Return of sagebrush to overgrazed North Ephraim common-use allotment, where fenced, 1958. Enclosure established in 1951. |

While the appeals from these decisions have gained considerable publicity, it should be understood that appeals were the exceptions rather than the rule. In perhaps 90 percent of the cases, the permittees accepted, however reluctantly, the decision of the district ranger. Ordinarily, the permittees did not like to have to reduce the numbers of stock, but they usually gave in. [80] Rangers on the Fishlake National Forest, for instance, made reductions as high as 70 percent without appeals. The success came in part because of the range improvements the Service was able to use as an incentive. [81] On the Ashley, Richard Leicht said that the program to eliminate common use initially appeared to be "like throwing Bengal tigers and elephants . . . in a big box," but that the Forest Service succeeded both in eliminating common use and reducing numbers. [82] By the mid-1950s, the Service had gotten "a good handle" on the range on the Humboldt. [83] The Payette had no appeals, and Foyer Olsen remembered none on the Dixie. [84] On the Manti-LaSal, between 1946 and 1956, the number of animal units of cattle and of sheep and goats combined were reduced, respectively, by 35,280 and 144,530. [85]

In some cases, dissatisfied stockmen would try to apply pressure on the Forest Service through their congressmen. Ordinarily, when a permittee wrote to a congressman, the letter would be sent through Forest Service channels, eventually reaching the forest supervisor, who was expected to respond with dispatch. [86]

The Payette provides a good example of a forest where appeals were the exception. In 1950, for instance, Supervisor J.G. Kooch reported that progress had been made on allotment analysis. On the basis of the analysis, a number of allotments—two, particularly, on the South Fork of the Salmon with steep slopes and loose granitic soils—were scheduled for retirement in 1951. [87]

As might be expected, the Payette received considerable flack from stockmen because of the intention to reduce the number of livestock. At a hearing held at Boise in January 1951, stockmen complained, saying that the best evidence of good range conditions was the 80- to 100-pound lambs coming off the ranges. Many were upset because they had paid a per head premium for the permits they held and consequently felt they were losing part of their investments, Some argued that the reductions would cut their herds below economically viable units. [88]

Despite these complaints, the forest reduced the number of livestock allowed. A General Functional Inspection (GFI) of Payette range management made by Oliver Cliff in 1959 pointed out that there were some deficiencies in proper training of personnel conducting the allotment analysis work, but that in general, the forest had proceeded, in spite of serious opposition from permittees, and had been generally successful. [89]

These efforts on the Payette were extremely difficult. In the 1940's, members of the Idaho congressional delegation had thwarted efforts to obtain corrective action on the Mann Creek allotment. During the late 1950's and early 1960's, forest and regional officers worked on the problem. As late as 1963, a difficult appeal case seemed in the offing. By then Edward Cliff was Chief of the Forest Service, and he told the regional officials that he would not back up any formal appeal if the region proceeded with a forced reduction program before making a large expenditure for range improvements. Through persistent efforts and successful negotiation, a formal appeal was avoided. Considerable progress was made on Mann Creek, but in many cases, progress was not rapid enough to stop deterioration, especially in the granitic soils of western and central Idaho. [90]

The GFI's helped by providing a stamp of approval on the allotment analysis and by monitoring progress on the forests. The Sawtooth National Forest Range Management GFI conducted by Oliver Cliff in 1957, for instance, recognized the progress the forest had made, but emphasized particularly the need to eliminate grazing from a number of steep, high-elevation areas, to correct problems caused by damage on stock driveways, and to improve planning of range rehabilitation projects. [91] A GFI of range management on the Boise by Floyd Iverson in 1956 indicated some deficiencies in allotment inspections and in installation of three-step transects. By 1960, some progress had been made, but the situation was far from ideal. [92] A major problem on the Boise continued to be the ability of well-placed stockmen to reach political leaders for support.

On some of the forests, grazing trespass continued to be a problem. On the Toiyabe, for instance, Ivan Sack reported in 1956 that the Austin and Tonopah districts had about 800 miles of unfenced boundary adjacent to BLM lands. Fencing could have controlled the trespass, but the cost of installation was prohibitive. Funds for boundary posting were not available either. [93] Forests often dealt with these problems by tagging regulations and impoundment procedures, as on the Minidoka. When range managers impounded trespassing livestock, the owners had to pay the impoundment costs to redeem them. [94]

At times, disputes between stockmen and Forest Service employees almost came to open warfare, Richard Leicht remembered going out with a ranger on the Payette to meet a permittee, George Speropulous, who planned to drive his sheep through a campground. The ranger told Speropulous, "You cannot go through the campground." Speropulous told the ranger he was going to drive his sheep through because it was the easiest way. "Okay," said the ranger, "only after the fight." Speropulous said, "What fight?" The ranger took off his coat and handed it to Leicht and said, "Now George, if you whip me, you can take them through the campground; if you cannot whip me, you go around." Finally Speropulous "just broke out in a big smile and said, I will go around." [95]

In some cases, several years after reductions had taken place, permittees would change their views. Some found that their calf crops increased as the grazing lands improved. One Minidoka permittee who had originally objected told Ed Noble, "You know, we thought you were a dirty guy, but you did us the biggest favor of any man we ever had in the country. You made us get control of the trespass and made us get down to managing that range. We developed a lot of forage of our own, and we are getting a lot better calf crops now, and fatter cattle. You made us money in the long run, by doing that." [96]

Whereas in Idaho most of the serious cases were dealt with in the political realm, the most serious disagreements in northern Utah forests led to appeals. On the Cache, the Logan Canyon Association appeal of a forest supervisor's decision that the regional forester, the Chief, and the Secretary of Agriculture had all upheld, denied the permittees' tenure by right on the grazing land and affirmed the adequacy of grazing allotment analysis. [97] Several appeals involved permittees in the Heber and Kamas areas, in part because of the aggressive attitudes of Don Clyde, president of the Utah Wool Growers Association, and Levi Montgomery, president of the Utah Cattlemen's Association, both of whom lived there. [98]

Most national publicity came from the Grantsville cattle permittees' appeal on the Wasatch National Forest because of the prominent figures involved and because the issues in the case addressed directly the rights to tenure of permittees and the question of the stewardship of the Forest Service for the land involved. The prevalent attitude among livestock interests, but probably not in the Grantsville community in general, seemed to be that by right of history, right of conquest, or right of continuous use, the Federal grazing lands really belonged to the permittees rather than to the Federal Government. This attitude found expression in the thoughts and actions of a number of members of the leading councils of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Strikingly, the opposite attitude—that the Federal Government had responsibility to exercise stewardship over the lands under its jurisdiction—also found expression among other members of the same governing bodies.

Incidents prior to the Grantsville appeal had made the Forest Service aware of the attitudes of some of the Mormon hierarchy. In January 1947, representatives of the Forest Service met with members of the LDS Church's First Presidency in Salt Lake City to discuss Forest Service policy. Then on February 12, 1950, at a stake conference in Mount Pleasant, UT, Elder Henry D. Moyle of the Council of the Twelve Apostles opened an attack on Forest Service management of grazing allotments and on proposed grazing reductions. He argued that the lands belonged to the permittees by right of prior settlement and that if they surrendered to Federal officials the right to make their own management decisions, they lost their freedom. [99]

Two days after the conference, Ivan L. Dyreng, ranger on the Ephraim District of the Manti-LaSal National Forest, wrote the First Presidency asking to meet with Elder Moyle. He requested also that Neil Frischknecht, a specialist in watershed management, Julian Thomas, assistant forest ranger from Monticello, and several others be allowed to attend. [100]

The meeting took place on February 21 in Moyle's office at the church office building in Salt Lake City. Dyreng and Thomas came as did Leslie L. Shelley, President of the Mount Pleasant Cattle Association and counselor in a local LDS bishopric, and D.A. Shelley, a permittee in the association and bishop who attended at Moyle's request. Dyreng and Thomas tried to explain the deteriorating condition of the watershed and invited Moyle or other church officials to come down and ride over the range. Moyle again called Forest Service management dictatorial, arguing that the people who lived near the lands ought to decide how to use them. Though he said he opposed destruction of the watersheds, he indicated that he would not trade the people's freedom for watershed protection, and he declined to ride the range. [101]

Following the meeting, Dyreng and Thomas submitted reports and the regional I and E office worked out a plan to deal with the problem. It was agreed that Thomas would maintain a contact with Moyle and that the region would initiate "an aggressive I&E program" with other church leaders to acquaint them with local problems. Officers were to contact more of the church leaders, especially Elder Ezra Taft Benson and President J. Reuben Clark, and to arrange show-me trips for members of the church welfare committee. [102]

As early as 1945, Elder Benson had shown considerable concern about the condition of the public lands. He declared in a conference address that Mormons should use information from the Forest Service and other sources to improve the range. [103] In 1953, Elder Benson became Secretary of Agriculture in the Eisenhower administration, and he continued the proconservationist policy. [104] In the mid-1950's, a committee in the Washington Office, including William D. Hurst, formerly with Region 4, recommended that the Service return the southern Idaho resettlement project to private ownership. Benson, who had grown up in the area near the project, wanted to keep the area in public ownership to demonstrate the benefits of sound grassland management. As a result, he overrode the committee recommendation and placed the project under Forest Service administration as the Curlew Grasslands. [105] While he generally opposed governmental interference in agricultural businesses, he felt quite strongly about the concept of stewardship over publicly owned resources.

Until about 1957, J. Reuben Clark, at the time second counselor in the First Presidency of the LDS Church, seems to have been concerned about good range management. When the Forest Service began to press for extensive grazing reductions among Grantsville permittees, however, he changed his position and began attacking the Service. [106] He laid out his views in a speech before the Utah Cattlemen's Association in December 1957. [107] For him, as for Moyle, the stockmen of Utah had "a moral right [to the federal grazing lands] by all considerations recognized in territorial acquisition," through exploration, conquest, and use. The contribution of Federal tax revenues to their management and improvement were, in his view, insignificant in comparison with the prior right. He argued, further, that it was the intention of some "fanatics" to transform the grazing lands into wilderness areas and eliminate grazing.

Although he admitted that the Forest Service gave lipservice to multiple use, Clark implied that the Service really favored an exclusively wilderness and recreational approach as embodied in a bill sponsored by Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota, which he misinterpreted as applying to all Federal grazing lands. Agreeing that some problems of overgrazing had existed in the past, he argued that these were the result of long-term moisture patterns that were currently shifting toward greater annual precipitation. For him, as for most stockmen, the measure of condition of the land was the condition of the animals leaving it.

He seems to have been unfamiliar with current Forest Service appeals procedure, because he proposed a system essentially similar to the one in use except that the initial decision on each allotment would have been made jointly by the ranger and two permittees, rather than by the ranger in consultation with the permittees. In any case, appeal could be taken by either the ranger or the permittees to the supervisor and higher officials as in the Service's system.

Clarke's address was prompted, in part, by his association with the Utah Cattlemens' Association and by the announcement of proposed reductions on the Grantsville allotment. [108] A permittee on the division, Clark opposed the reductions, even though range allotment analysis showed the range seriously overstocked. Ranger Mike Wright laid out the proposed reductions, which the association, represented by attorney Art Woolley, a relative of Clark's, appealed to Forest Supervisor Felix C. Koziol, Regional Forester Floyd Iverson, and Chief Richard E. McArdle. In line with Clark's views, Woolley argued that grazing was a right, not a privilege: that the reductions were not based on a realistic assessment of range condition; that any problems resulted from Forest Service management, not overgrazing; that deer, not cattle, were responsible for any range damage; and that the range could be improved without livestock reductions. After the permittees received adverse decisions at every stage of the appeal, they decided not to appeal to the Secretary of Agriculture. [109]

In dealing with the problems caused by such a prominent leader opposing its action, the Forest Service and Agriculture Department worked very carefully. President Clark traveled to Washington to meet with Secretary Benson to try to enlist his support. William D. Hurst, assistant regional forester for range management, and James L. Jacobs, assistant regional forester for information and education, met with Clark to try to explain the Forest Service policy. [110] In addition, the two assisted Secretary Benson in drafting a letter to Clark outlining the necessity for multiple-use management of the public lands and questioning the concept of their use by graziers as a right rather than a privilege. The letter emphasized that the lands belonged to all the people of the United States and that the Service ought to manage them in the public interest. [111] Clark and Benson exchanged similar views, in talks before the April 1958 Latter-day Saints' general welfare meeting. [112]

In spite of Clark's insistence on the doctrine of preemptive occupation, in view of Bean A. Gardner, general counsel for Region 4, the Grantsville case was hardly precedent setting. There was, he said, obviously "nothing legally at stake." Clark cited no legal precedents, but merely gave his own opinions, and Woolley's briefs showed no legal grounds for the permittees' views. Gardner thought that the Service's proper course of action was merely "to show that the Forest Service was the professional manager of this land" rather than to deal with the legal issues. [113] At the time, Gardner issued a legal opinion on the question of rights of the permittees in which he cited precedent showing that the permittees had no "rights" to the land, and that contrary to what J. Reuben Clark had insisted, both statutory and constitutional law supported the Service's position. [114]

|

| Figure 73—Rangers compare ungrazed check plot with moderately grazed area outside fence, Benmore Experimental Range, Utah. |

After the case had been settled, the Service began to reduce livestock numbers and improve the land. Supervisor Koziol indicated that positive results had begun to show up by 1965. [115]

During these negotiations, the regional office worked with the media and the stockmen to try to disarm criticisms. In December 1957, Regional Forester Iverson, assistant regional forester Jacobs, and Howard Foulger from the division of range management, met with officers of the Utah Cattlemen's Association and reporters for the Deseret News and Salt Lake Tribune. They had a frank exchange of views, and the meeting was quite peaceful; nevertheless, opinions remained unchanged. [116] Throughout the period, the presses fairly hummed with blast and counterblast on the question, but while the stories provided details of the dispute, little in the way of new interpretations appeared. [117]

Meanwhile, the stockmen tried to apply political pressure to get the grazing reductions rescinded. In mid-December 1957, Utah Senator Arthur V. Watkins called for a moratorium on all reductions. [118] The stockmen also pressed Governor George D. Clyde to back them. Clyde, however, who was an irrigation engineer by profession, agreed with Secretary Benson and supported the Forest Service. [119] While the Deseret News tended to favor conciliation, the Salt Lake Tribune editors, to the consternation of the stockmen, made it clear that in their view, "Watershed Stability Is Still [the] Main Issue." [120]

Although the Grantsville case engendered a great deal of controversy and raised again the question of the rights of the permittees and the Forest Service to the degree that Gardner felt it necessary to issue a legal opinion, it settled no new questions of law. The Hobble Creek Cattle Allotment case on the Uinta National Forest settled basic questions on Forest Service procedures. Instead of basing their appeal on dubious legal theories, the permittees raised a direct legal challenge to the adequacy of the Forest Service's grazing allotment analysis procedures and to the ways in which the concept of multiple use was interpreted. In addition, the permittees mounted a persuasive campaign emphasizing the adverse impact of the reductions on the local economy. [121]

The case followed a long train of events in which cooperative efforts eventually reached an impasse. When James Jacobs came to the Uinta as forest supervisor in 1950, many cattle allotments were nominally 6 months long, though the cattle actually entered the range when joint inspections determined they were ready. Since problems with overgrazing persisted, the Forest Service cut a month from the season to begin with. [122] Between 1955 and 1958, allotments with common use were divided, and some permittees took reductions of more than 20 percent. [123] The Forest Service had tried to work with the Springville Cattlemen's Association to rehabilitate the Hobble Creek allotment, but in 1955 the permittees refused to divide the allotment and refrain from use during range reseeding, and the Service refused to put any more money into what it perceived as a futile effort. [124]

By 1958 allotment analysis showed the need for drastic reductions. An analysis of the data led Merrill Nielson, ranger on the Spanish Fork District, to prescribe a stocking reduction of 84 percent—from 12,475 to 2,000 cow-months—by 20-percent increments over 4 years beginning in 1960, coupled with a $200,000 rehabilitation program. [125] By 1957, Clarence Thornock had replaced Jacobs as supervisor, so the job of implementing the prescription fell to him and Nielson. The permittees refused to accept Nielson's decision and appealed to Thornock who sustained it. [126]

Members of the association appealed immediately to Regional Forester Iverson. In a news release, Arthur W. Finley, president of the Springville Cattlemen's Association, charged that the Service had discounted the effectiveness of the rehabilitation work the cattlemen had done after the Service withdrew its assistance. Finley said that the transects misrepresented the condition of the range, arguing "that dropping the hoop a foot in either direction would completely change the picture." [127]

Unlike Woolley in the Grantsville appeal, Clair M. Aldrich from Provo, attorney for the Hobble Creek permittees, presented his appeals very effectively. [128] The regional hearing, conducted by Dean Gardner, was held in July 1959, but at the request of the permittees, Iverson did not render his decision until November 10. In making their appeal, the permittees called a number of experts in range management including John F. Valentine of the Extension Service, G. Wayne Cook, research professor in range management at Utah State, and L.A. Stoddard, head of the department of range management at Utah State in addition to local officials from Springville. [129]

Even though the appeal was well drafted, the permittees stood little chance of overturning Forest Service range management criteria. For the Service, "suitable range is defined by the Intermountain Region's livestock-game Range Allotment Analysis Instructions as forage-producing land which can be grazed on a sustained-yield basis under an attainable management system without damage to the basic soil resource of the area itself, or of adjacent areas." Under this definition, cattle could not graze on steep slopes like those on portions of the Hobble Creek allotment, because, unlike sheep, cattle tended to drift into the bottoms instead of remaining on the hillsides. Successive studies had shown significant increases in bare ground and soil disturbance. Iverson addressed the problem of the economic impact by pointing out that half the permittees were "only partially dependent upon the national forest grazing permits for their annual income," and that other economic values, including recreation and watershed destruction, had to be considered as well.

Permittees offered the animal weight improvement argument. In response, Iverson cited research of Lincoln Ellison that demonstrated that range could produce improving animals and still decline, because the animals would shift from preferred species to less palatable plants and even browse on twigs and branches to remain healthy. Under those conditions, however, soil erosion would occur. Ellison concluded that condition of the land rather than of the animals must be taken as the measure of proper stocking.

Following Iverson's adverse decision, the permittees appealed to Chief McArdle who rendered his decision in 1962. The appeal focused basically on two points: (1) the adequacy of range allotment analysis as a means of determining suitable stocking, and (2) the adverse economic impact of the reductions. In reviewing the chief's decision, it is clear that while the permittees' expert witnesses raised a number of questions about the analysis procedures, they could not demonstrate to his satisfaction that the methods used by the Service were unsound or that alternative criteria for measuring suitability of the range were superior. In the Forest Service's view, based on research by the Intermountain Station, about two-thirds of the vegetation should remain after grazing in order to protect the watershed from excessive erosion. In simple terms, the analysis in the Hobble Creek case showed that sufficient vegetation did not remain and that erosion had occurred at an excessive rate. [130]

By 1962, when the appeal went from McArdle to the Secretary of Agriculture, John F. Kennedy had replaced Dwight D. Eisenhower as President and Orville Freeman had supplanted Ezra Taft Benson as Secretary of Agriculture. In sustaining McArdle's decision, Freeman rejected the permittees "sacrifice area" doctrine (that some low-lying areas had to be overgrazed in order to provide adequate use of all range within the allotment) and their allegation that the forest officers had been arbitrary and capricious in their application of allotment procedures. [131]

In retrospect, it seems clear that the policies and practices of the Forest Service contributed to the difficulties on Wasatch Front allotments. [132] For some time after the inauguration of range management under the General Land Office then under the Forest Service, the optimistic attitudes of range managers and permittees led both to believe that prescribed reductions and range rehabilitation would improve the grazing allotments to an acceptable level.

Some improvement in animal forage production did occur, and weights of animals improved. However, in cattle allotments particularly, the livestock would tend to move into the improving range in the bottoms, and improvement would then be noted on the higher slopes. Cattlemen would cite the unused forage on the steep hillsides as evidence that the ranges were underutilized.

The level of improvement that produced such weight gains, however, did not restore the land to a satisfactory condition. In practice, forage could remain on the slopes, and excessive erosion still occur in the bottoms. Research at the Intermountain Station and the introduction of more precise measures of condition and trend through the Parker three-step method provided the data the Service needed to inaugurate the tougher corrective measures required. Ranger Merrill Nielson, for instance, found that only 13 percent of the forage on the steep Hobble Creek allotment could be utilized without excessive erosion.

These management prescriptions violated the expectations of the permittees, and they resisted. In most cases, the Service was able to work out accommodations and get the permittees to accept, however reluctantly, the prescribed reductions and range rehabilitation. Why specifically, then, did the allotments in northern Utah serve as the focus for permittee intransigence? To say that the permittees were independent is no answer as stockmen throughout the region shared that sense of independence. That they were predominantly Mormons does not explain the situation either; the majority of the other permittees in Utah and southeastern Idaho were Mormons as well. In addition, the permittees throughout the region shared the same attitudes about the allotments. In all portions of the region the Forest Service found both permittees who were cooperative and those who were not.

Two reasons seem most important for understanding the exceptionally high rate of appeals from northern Utah. First was the fact that the reductions on the northern Utah forests were announced ahead of many of the others in the region. In William Hurst's view, had substantial reductions on other forests of the region been announced ahead of those in northern Utah, the appeals would have come from the other areas instead. In fact, in Idaho, there was concerted, if less extensive, resistance on the Mann Creek allotment on the Payette and the Sixteen-to-One Allotment on the Boise.

A second factor was the rapidly changing conditions under which the northern Utah stockmen lived. They were predominantly residents of towns and cities, and although the same was true of permittees on the Manti-LaSal, Dixie, and Fishlake, northern Utah was different. Permittees in northern Utah lived not only in the oldest settlements in the region, but also in the most rapidly urbanizing area. They were keenly aware that the way of life they had known was under attack. These had been their allotments. Now recreationists, hunters, wilderness enthusiasts, and other townspeople who feared watershed deterioration more than loss of grazing land seemed to threaten not only the control of lands the stockmen perceived to be theirs, but their livelihood and their way of life. What besides this sort of fear would lead distinguished men like J. Reuben Clark, former solicitor of the State Department and legal advisor to national and international bodies, and Henry D. Moyle, with law degrees from Chicago and Harvard, to assert that land that was clearly the property of the entire United States belonged to and ought to be managed as a matter of right solely by the permittees who used it?

In retrospect, then, it may be most useful to see these northern Utah appeals as the last gasp of a dying way of life as well as the efforts of a group of powerful community leaders to promote their interests. However, the appellants lacked political support. The only major Utah political leader who backed them was Senator Arthur V. Watkins, and significantly, he came from a Wasatch Front city not far from Springville where most of the Hobble Creek permittees lived. Even Governor George D. Clyde, with family connections in Springville, failed to provide support. Secretary of Agriculture and Utah native Ezra Taft Benson insisted on the priority of Forest Service stewardship and multiple-use management (Table 16).

Table 16—Animal-months of livestock grazed in Region 4, 1950-69

| Cattle and horses (animal—months) |

Sheep and goats (animal—months) |

||||

| Year | Estimated grazing capacity | Actually grazed |

Estimated grazing capacity | Actually grazed |

Total paid permits |

| 1950 | 1,211,167 | 1,J79,479 | 4,031,758 | 3,532,673 | 6,699 |

| 1951 | 1,150,171 | 1,179,354 | 3,873,626 | 3,575,926 | 6,988 |

| 1952 | 1,066,890 | 1,195,362 | 3,453,885 | 3,623,847 | 6,875 |

| 1953 | 994,050 | 1,172,096 | 3,276,773 | 3,552,984 | 6,790 |

| 1954 | 956,497 | 1,180,363 | 3,142,834 | 3,559,608 | 6,702 |

| 1955 | 942,282 | 1,134,049 | 2,998,781 | 3,475,762 | 6,478 |

| 1956 | 920,378 | 1,125,869 | 2,891,510 | 3,321,323 | 6,343 |

| 1957 | 895,469 | 1,068,768 | 2,791,643 | 3,070,904 | 6,254 |

| 1958 | 877,218 | 1,052,445 | 2,762,189 | 3,166,354 | 5,979 |

| 1959 | 842,101 | 1,031,748 | 2,588,958 | 1,123,409 | 5,861 |

| 1960 | 827,265 | 1,062,109 | 2,549,886 | 1,135,498 | 5,691 |

| 1961 | 821,458 | 1,053,653 | 2,402,144 | 2,978,412 | 5,545 |

| 1962 | 817,618 | 1,050,326 | 2,348,085 | 2,881,073 | 5,468 |

| 1963 | 816,375 | 1,048,873 | 2,336,711 | 2,757,643 | 5,490 |

| 1964 | 813,568 | 1,046,325 | 2,327,704 | 2,611,286 | 5,276 |

| 1965 | 827,341 | 1,034,706 | 2,364,056 | 2,501,143 | 5,030 |

| 1966 | 828,774 | 1,017,546 | 2,340,597 | 2,555,806 | 4,637 |

| 1967 | 830,529 | 1,024,545 | 2,338,764 | 2,378,129 | 4,637 |

| 1968 | 858,170 | 1,019,467 | 2,353,802 | 2,387,361 | 4,636 |

| 1969 | 898,459 | 1,074,680 | 2,361,647 | 2,372,081 | 4,512 |

Source: USDA Forest Service, Annual Grazing Statistical Report, Region 4, Summary (Furnished by Philip B. Johnson, Interpretive Services and History, Regional Office.) | |||||

Research

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact of research at the Intermountain Station on the development of range allotment analysis and grazing management prescriptions. Perhaps as part of the movement for consolidation, in 1953, the Forest Service extended jurisdiction over what had been the Northern Rocky Mountain Station in Region 1. At the same time, the Eisenhower administration created the Agricultural Research Service in the Department of Agriculture. [133]

Of particular importance was research on range revegetation. Lincoln Ellison, who joined the staff of the Intermountain Station in 1938, led the station in important studies of range ecology and influenced the discipline long after his untimely death in an avalanche near Snow Basin in 1958. [134] Work at the Davis County Experimental Watershed particularly aided in the management of ranges and watersheds throughout the region. Research at the Desert Experimental Range, which had been established near Milford in 1933, showed that proper management could improve forage production and double net income from sheep grazing on salt desert shrub ranges. [135]

Research on timber management centered particularly at the Boise Basin Experimental Forest established in 1933 near Idaho City. Particularly concerned with the regeneration and management of ponderosa pine, its scientists also worked at other locations in the Boise, Payette, and Salmon National Forests. [136] The Town Creek Plantation on the Boise, for instance, was a pilot project in planting ponderosa pine. [137] Other studies published by the Intermountain Station included methods of managing lodgepole pine. [138]

In addition, the region cooperated with the California research station in studies on ponderosa pine. In 1955, Chet Olsen instructed supervisors at various Idaho and Utah forests where ponderosa pine grew to cooperate in collecting seeds for a genetic study to determine conditions under which the seed from various locations would generate and grow. [139]

Besides authorizing funds for range rehabilitation, the Anderson-Mansfield and Granger-Thye Acts authorized expenditures for tree seed, nursery stock, and forest rehabilitation. [140] In the 1950's, all tree seedlings for southwestern Idaho and western Nevada were furnished from outside the region. [141] In 1959, the region established the Lucky Peak Nursery on 296 acres near Lucky Peak Reservoir about 15 miles east of Boise. In 1960, Lucky Peak began receiving seeds for 10 tree species from throughout the region and producing seedlings that were returned to the place of origin for transplanting. By 1965 the nursery had become the chief supplier of seedlings for the region. [142]

Timber Operations

In managing timber operations in Region 4 during the 1950's, there were several conflicting pressures. First was the need to provide timber to maintain economic stability in the lumbering towns of southwestern Idaho. Second was the problem of erosion and ecological destruction from the construction of timber roads. Third was the need to rehabilitate and replant cutover areas.

|

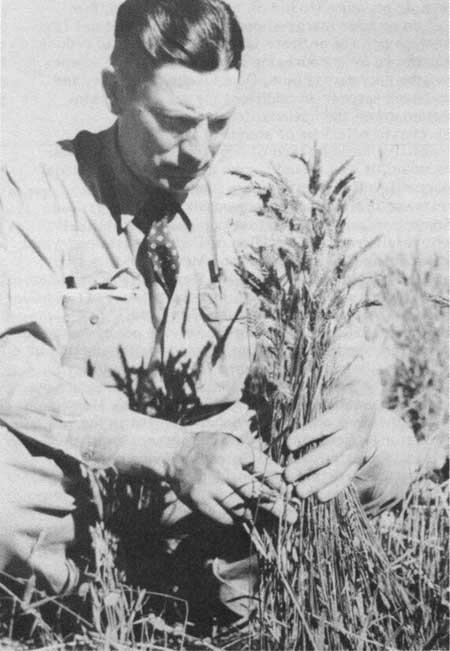

| Figure 74—Ranger with crested wheatgrass on Meadow Creek Project, 1950's. |

The scope of the first problem was quite apparent in a meeting in July 1950 between Regional Forester Olsen and W.L. Robb, assistant regional forester for timber management, and the supervisors and timber staffs of the Boise and Payette. [143] Seventy-six mills then operated adjacent to the two forests. The annual sustained yield cut for both national forests and the nearby private and state land stood at 60 million board feet. The capacity of those mills was far in excess of that volume. Robb thought they ought to "strive for fewer mills," and to place fewer, but relatively "larger units of national forest stumpage on the market periodically, rather than attempt to split available cut into a larger number of small offerings for the possible benefit of a greater number of mills."

Though the report of the meeting does not indicate this, it is apparent that such a policy would place great economic pressure (to bid on national forest timber sales) on smaller marginal operators who could not find timber on private or State land. Olsen hoped to reduce the pressure by encouraging companies to take species other than ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, white fir, and Engelmann spruce. In addition, the regional administration urged the national forests to reoffer unpurchased offerings of stands of timber on a competitive basis instead of negotiating private sales. This would, it was thought, give all companies an equal opportunity. Regional officers suggested that the forests use oral bidding where possible.

Some foresters thought that community stabilization might result from the creation of Federal sustained-yield units at Idaho City, Cascade, and McCall. After study, the only unit actually proposed in Region 4 was at Idaho City. The proposal was killed, largely because of opposition from outside the Idaho City area. [144]

Between 1950 and 1954, Forest Service policy began to shift as the Washington Office pressed for the cutting of a substantially increased volume of timber on the national forests. [145] (For the impact of this pressure on Region 4, see tables 17 and 18.) In 1950 Ira J. Mason, chief of the division of timber management in the Washington Office, made a detailed inspection of the Boise and Payette National Forests. Mason concluded that the two forests were considerably more important for timber production than had been previously acknowledged and that their "sustained yield capabilities appeared much greater than other ponderosa pine areas such as the Black Hills or Coconino Plateau, which had received a great deal more attention." [146] Mason recommended a timber management planning analysis covering the two forests and adjacent areas in the ponderosa pine belt. Also in 1952, Chief McArdle inaugurated a general timber resources review of all national forests. [147]

Table 17—Comparison of quota and actual timber cut in Region 4, selected years 1949-69

| Year | Quota (MMFBM) (Before 1951, estimated allowable cut) |

Actual cut (MMFBM) |

| 1949 | 169.2 | 134.4 |

| 1951 | 169.4 | 150.3 |

| 1952 | 160.0 | 138.5 |

| 1953 | 160.0 | 182.3 |

| 1954 | 239.2 | NA |

| 1955 | 225.0 | NA |

| 1967 | 457.0 | 434.6 |

| 1969 | 460.0 | NA |

Source: Regional Office Records, RG 95, Denver FRC | ||

Table 18—Commercial transactions of convertible forest products in Region 4, 1950-69

| Cut |

Sold |

|||

| FY | MFBM | Value ($) | MFBM | Value ($) |

| 1950 | 111,651 | 440,252 | 117,118 | 775,163 |

| 1951 | 147,075 | 860,243 | 175,822 | 1,033,571 |

| 1952 | 128,666 | 959,750 | 145,547 | 881,727 |

| 1953 | 141,737 | 922,117 | 113,952 | 788,341 |

| 1954 | 174,117 | 1,202,999 | 171,193 | 1,309,496 |

| 1955 | 251,638 | 1,699,572 | 272,585 | 2,155,613 |

| 1956 | 293,791 | 2,709,917 | 391,570 | 4,289,865 |

| 1957 | 324,819 | 3,210,105 | 289,324 | 2,258,957 |

| 1958 | 260,259 | 1,822,732 | 227,334 | 1,392,587 |

| 1959 | 314,108 | 2,116,219 | 503,968 | 3,914,795 |