|

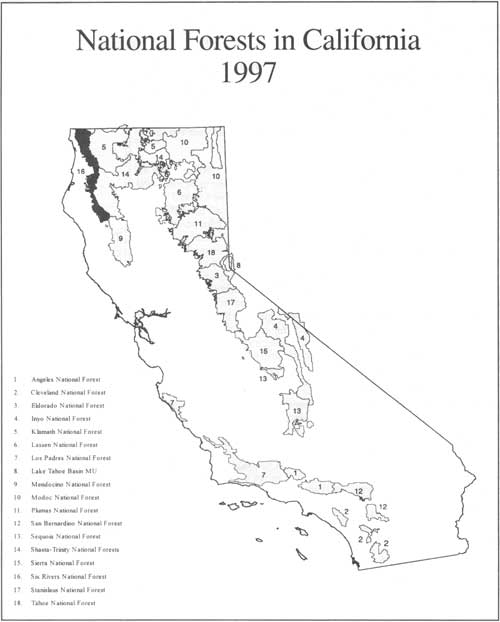

A History of the Six Rivers National Forest... Commemorating the First 50 Years |

|

"The Six Rivers is Now Officially on the Map"

"There Are A Lot Of Things Brewing..."

June 3, 1947 marked the official beginning of the Six Rivers National Forest. Presidential Proclamation 2733 formalized creation of this, the youngest of the Pacific Southwest Region's national forests:

WHEREAS it appears that it would be in the interest of administrative management to consolidate certain portions of the Siskiyou, Klamath, and Trinity National Forests, within the State of California, into a national-forest unit designated as the Six Rivers National Forest:

NOW, THEREFORE, I, HARRY S. TRUMAN, President of the United States, under and by virtue of the authority vested in me by section 24 of the act of March 3, 1891, 26 Stat. 1103 (16 U.S.C. 471), and section 1 of the act of June 4, 1897, 30 Stat. 11, 36 (16 U.S.C. 473) do proclaim that all lands within the exterior boundaries of those parts of the Siskiyou, Klamath, and Trinity National Forests lying west of the following-described line are hereby eliminated from those forests and are consolidated to form and shall hereafter constitute the Six Rivers National Forest: ... [US Presidential Proclamation 2733 1947].

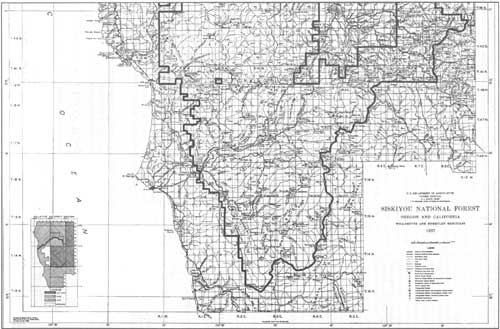

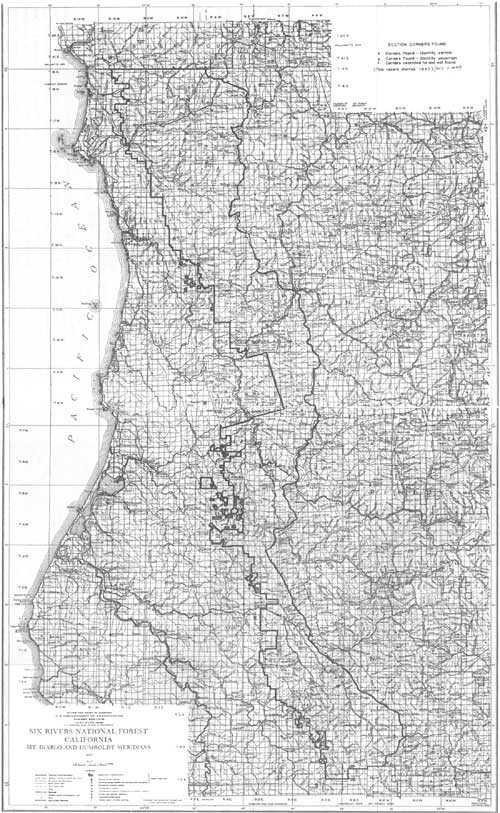

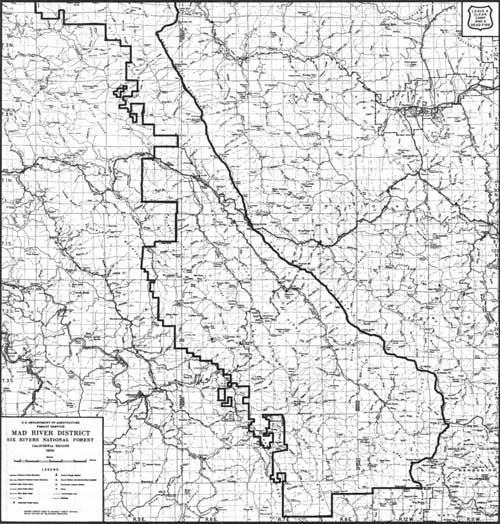

The proclamation continued by describing the boundaries of the new national forest. The Six Rivers' initial 900,000 acres was an amalgam of three, long-established national forests from two regions: the Siskiyou of Region 6, and the Klamath and Trinity national forests of Region 5. [2] Formerly part of the Siskiyou headquartered in Grants Pass, Oregon, a net of 308,138 acres was transferred from Region 6, being almost all of its Gasquet Ranger District. A net of 222,335 acres was transferred from the Klamath National Forest headquartered out of Yreka, California, and comprised about 75 percent of the old Orleans Ranger District. A net of 395,572 acres was transferred from the Trinity National Forest, headquartered in Weaverville, California, which encompassed about 75 percent of its Lower Trinity and all of its Mad River ranger districts. Subsequently, 14,492 acres comprising the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit (NRPU) were also transferred from the Trinity National Forest to the new Six Rivers (USDA, ES n.d.: 2). [3] In drawing the new lines, some district boundary adjustments were made to provide for "a logical inter-forest boundary" (Cronemiller and Kern 1950: 1). [4] With the addition of the NRPU, the Six Rivers embraced 1,108,368 acres; 940,537 acres of which were national forest system lands and the remainder being privately held lands within the forest boundary (HT 7-20-52). Without elaborating on the history and maneuverings behind establishment of the new national forest, the employee newsletter for Region 5, the California Ranger, succinctly announced that: "The Six Rivers Forest is now officially on the map. The proclamation was signed by President Truman on June 3" (CR 6-11-47).

Though the proclamation was not official until June 3, 1947, formation of a new national forest from pieces of the Siskiyou, Klamath, and Trinity had been bandied about for several years, and the notion had been a serious consideration at least since latter 1935. It was in that year that California's Regional Forester—then titled "District Forester—Stuart B. Show ordered preliminary surveys in the area and began to push for a separate national forest in the north coast of California [5] (HT 3-13-49).

The earliest piece of inter-regional correspondence found thus far referencing the potential transfer of Region 6's California lands to a Region 5 forest was November, 1942. Lyle F. Watts, Regional Forester for Region 6, was on the verge of becoming Chief Forester for the Forest Service. Watts was at a meeting in Denver when Region 5 Forester Stuart B. Show's letter, referencing the transfer, arrived in Portland. H. J. Andrews, acting in Watts stead and lacking background information on the topic, wrote to Show: "I have your letter of November 25 about the transfer of the Gasquet District to Region 5." Andrews promised to take a copy of Show's letter to Denver in order to discuss it with Watts (Watts 11-30-42). From the tone and content of this letter, it is obvious that Watts and Show had already discussed and were in agreement about the transfer of California lands from Region 6 to Region 5, even though there was no clearly defined new national forest to which it would be attached.

Between 1942 and the end of World War II, little was done regarding the inter-regional land transfer and creation of the new national forest; war considerations clearly took precedence. In fact, the only documentation found thus far on the subject, after 1942 and before 1946, is from a retrospective by Russell W. Bower. In 1944, while Bower was assigned to the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit, he was asked by Regional Forester Show to:

. . . make a study for the creation of a new National Forest in the North Coast area. The report was to be personal-confidential for his eyes only. I submitted the report, outlining the areas proposed for inclusion, a proposed organization and budget structure. Show then wrote to Lyle Watts, Regional Forester, Region 6, about the possibility of taking back the Gasquet District from Region 6.... [After approval of the idea by Watts,] Show then made arrangements for me to start negotiations with the Siskiyou Forest as to details of the proposed transfer. I made contact with the Siskiyou Forest Supervisor and received the finest kind of cooperation.... Soon after I was transferred to the Modoc and Show left for the F. A. O., so further action was deferred for a couple of years. I had the satisfaction of seeing the Six Rivers created almost exactly as first proposed [Bower 1978 vol. 5:110].

Regardless of the dearth of official correspondence about the transfer and a new national forest, there was undoubtedly a seasoning of the concept in the minds of Forest Service leadership during those three years. Moreover, tremendous wartime demands on the lumber industry and on the timber resources, as well as the anticipated post-war voracity for forest products and the fear of raging unemployment assured that the idea would not die on the vine. Adding Gasquet District to the Region 5 lands planned for the new national forest was key to creating a viable administrative unit... and forming a new national forest on California's north coast was key to utilizing the affected timberlands and to developing the north coast regional economy—providing critical raw materials and producing a huge number of jobs in a territory perennially plagued with unemployment.

By January 1946, H. J. Andrews was Regional Forester for Region 6 and Lyle Watts was Chief Forester in Washington, D. C.. Andrews wrote to Show:

We propose the transfer of the Gasquet District lock, stock, and barrel, including personnel, improvements, property, and such heavy equipment as rightfully belongs to that District.

Andrews letter outlined changes in the proposed boundary between Region 5 and Region 6 and suggested a series of coordinating meetings to iron-out financial adjustments and other details. He expressed conviction that the inter-regional agreements should and could be completed by early spring 1946, that recommendations for the transfer would be promptly forwarded to the Chief Forester for approval and, that upon the Chief's administrative approval, a presidential proclamation could be completed with an effective date of July 1, 1946. Regional Forester Andrews closed his letter to Show by noting:

It is with some reluctance that we offer you what has been for so long a part of Region 6, but we are consoled by the fact that the Gasquet District is going into good hands and that administration can be carried on more effectively by your Region than by ours [Andrews 1-15-46].

Work analyses were completed for financial and personnel planning, equipment and livestock were readied, and maps were re-drawn in preparation for the transfer. The skids for the transfer were undoubtedly greased when Lyle Watts was elevated from Region 6 Forester to Chief Forester; his intimate familiarity and support of the concept made agency administrative approval a shoo-in. Regional Forester Show received a telegram on February 26, 1946 that the Chief had approved the transfer of Gasquet from Region 6. [6]

On March 6, 1946, Representatives from both Regions met in Grants Pass to work out some of the details of the transfer. This was an extraordinary meeting of the minds, with many far-reaching recommendations made. One issue was whether the inter-regional boundary should follow the political boundary between Oregon and California or whether it should be defined by other administrative considerations. In the resulting memorandum of understanding (MOU), the parties recommended that the boundary be located "for economical administration, taking into account working circles, natural topographical features and community interest." Aware that this recommendation did nothing to simplify the problematic handling of Oregon and California funds, the signatories believed the advantages of using the "natural" opposed to the "political" boundary outweighed the funding inconveniences.

At that time, what was then the southeastern part of Region 6's Rogue River National Forest was administered by Region 5's Klamath National Forest under an agreement between the Rogue and the Klamath. Under the new agreement, this piece of the Rogue within the State of Oregon would be transferred to the Klamath. The signatories argued that it would not create additional problems for the Klamath, which already had some Oregon territory south of the Siskiyou Summit. On the Siskiyou National Forest, the State line was recommended as the Regional boundary except in the Illinois River country. As integral to the Siskiyou's Page Creek District and not to Gasquet Ranger District, they argued that the area was "part of a continuous timbered area that will be logged out to the North" and that the logical economic unit "should not be broken up by any artificial line just to use the State line." Interestingly, for the north-south boundary to the west, they believed the state line was okay as the regional division since the timber from the north end of the North Fork Smith River Working Circle "will no doubt go out to the East rather than to the South."

The inter-regional representatives also recommended that Gasquet District be attached to the Klamath rather than to the Trinity National Forest due to a pending change in forest supervisors on the Trinity. Seen as a temporary move in order to effect the transfer, the representatives also recommended that discussions be initiated with the Chief Forester about

. . . establishing the Redwood Forest [later named the Six Rivers] with headquarters in Eureka by July 1 [1946].... We feel we could start this unit with two overhead men and three clerks for perhaps $22,000 for the first year. This would be a four Ranger District Forest plus the [Northern] Redwood Purchase Unit which could no doubt be administered with the Gasquet District as one unit with the Eureka staff supervision of the broader features of the redwood program.... [7] There are a lot of things brewing in the area right now which we ought to get in on.

Finally, the signatories believed it best to keep a low public profile about the transfer and resolved that "no publicity will be given the proposed move until mutually agreed to by the Regions both as to time and subject matter" (Deering 3-8-46). Regional Forester Show wasted no time forwarding the MOU to Chief Forester Watts, asking that it be approved and that Watts allot the requested sum to set up the "new National Forest headquarters at Eureka. This is the most urgent finding of the work load and boundaries report from Region 5" [8] (Show 3-11-46). Within a couple weeks of receiving the proposed memorandum of understanding, Regional Forester Show traveled to Washington, D.C. and met with Chief Watts. Temporarily dubbing it the "Northern Redwood" forest, Watts promptly approved establishment of the new unit. He told Show, however, that he could not guarantee allotment in fiscal year 1947 of the full $22,000 requested and indicated that it would be better to transfer Gasquet after the end of fire season; by that time, the Northern Redwood National Forest will have been established (Show 3-20-46 and Watts 4-1-46).

Shortly after this correspondence, Gasquet's transfer was made contingent upon creating the Northern Redwood National Forest and attaching the district to that new unit (Horton 4-15-46). While Region 6 was set to make the transfer, Region 5 scrambled to work out more administrative kinks for the proposed national forest and to finalize adjustments in the forests from which pieces were to be lopped.

|

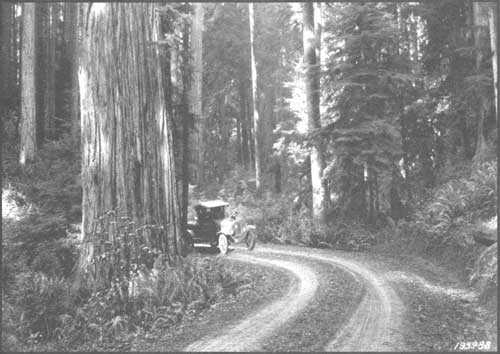

| Part of the Redwood Highway between Crescent City and Grants Pass, near the confluence of the Siskiyou Fork. Many of the soil types on the Six Rivers are prone to road slippage. US Forest Service photo |

The Brandeberry

Report

|

Ranger Quackenbush "appears to be mainly interested in maintaining

improvements rather than resource development which would be only

natural for a non-technical man in his position."

|

September 3 through 13, 1946, Region 5's J. K. Brandeberry visited the north coast at the behest of his boss, Assistant Regional Forester R. L. Deering. Brandeberry's report documented his objectives: to review the tentative boundaries for the new forest, to survey Eureka for office space and employee housing, and to inspect some of the operational functions on the Trinity. Brandeberry, a well-respected employee with wide-ranging experience, recommended minor adjustments from the "Recommended Reorganization of National Forest & Ranger District Boundaries and Calculated Load." These included using the divide between the South Fork Trinity River and the Mad River rather than the river channel of the South Fork Trinity River as the eastern boundary for Mad River District. Attention was also given to whether the New River drainage should stay with the Trinity or become part of the new forest; Brandeberry ultimately recommended it stay with the Trinity. Brandeberry agreed with the line advocated by the Klamath for its boundary—closely following the county demarcation between Chimney Rock and Salmon Mountain. Prophesying some of the plaguing administrative difficulties still experienced by the Six Rivers' Orleans and the Klamath's Ukanom ranger districts, Brandeberry noted that:

Increased use can be expected with the improvement of connecting roads to the Redwood Highway so that within the next few years either an extension of the Orleans District or a new district such as the Klamath forest has suggested [reactivating the old Seiad District and creating a new district with headquarters in the vicinity of Somes Bar] would seem in order. Administration of a new district should be a part of the new coast forest, however, rather than by the Klamath forest [Brandeberry 9-25-46; cf. James 8-29-46].

Brandeberry, too, thought that the new forest should be managed through four ranger districts, with the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit being administered by the Gasquet District. His analysis indicated that the existing professional workload at Orleans was the lightest of the four districts. Interestingly, Brandeberry was apparently asked to size-up Gasquet's Ranger Quackenbush—unlike the rangers who would head-up the other districts, he was an unknown quantity....

He is a man in his late 50s, having entered the Forest Service in 1927 with a 5-year Army service in World War I. He has been a ranger on the Gasquet District for periods 1927-1931 and 1940 to date. Appears to be mainly interested in maintaining improvements rather than resource development which would be only natural for a non-technical man in his position. Buildings around headquarters, especially warehouse, are kept immaculate. Fire suppression barracks, however, apparently are not often inspected as we found them the dirtiest crew quarters I've ever experienced anywhere. Ranger Quackenbush is not as well acquainted with prominent people in Del Norte County as one might expect with his years of service in that locality. Would consider him willing and cooperative in handling any assignment [Brandeberry 9-25-46].

| |

| This verse is about the life of a ranger during the custodial era of Forest Service land management; it is from The Forest Ranger, a 1919 compendium of poems collected by John D. Guthrie, a former Forest Supervisor Gifford Pinchot reviewed the draft of this book in 1917 and congratulated Guthrie on giving "the general reader a chance to understand something of what the work actually means to the men who are doing it on the National Forests." |

Brandeberry had also been asked to sniff-out the local attitude around Eureka regarding the Forest Service. His findings substantiated a previous report that:

Local antagonism has been accelerated with confusion created through the recent introduction of the Douglas Bill. Sharp shooters at some of our policies have advanced the belief that the Forest Service is establishing a new Supervisor's headquarters in this area for the primary purpose of getting a further foothold for future expansion and possible development of the entire Redwood region. Since the new forest is formed by the realignment of existing administrative units, I feel rather strongly that the name should not include any reference to the redwoods or local points of interest. A suggestion for consideration is the Silcox National Forest [Brandeberry 9-25-46].

|

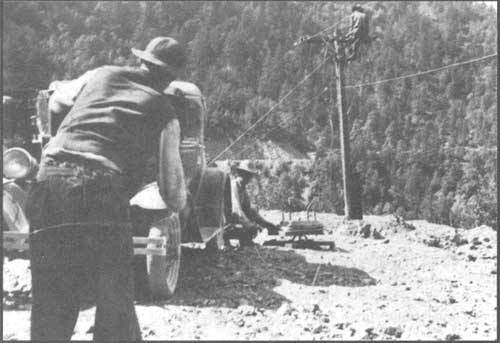

| The Forest Service was often the first to bring telephone connections to remote areas. This 1934 photo shows telephone line being strung between Orleans and Somes Bar. Fred Wilder is on the reel and Lee Morford is attaching the line to the pole; the third man is unidentified. US Forest Service photo |

Confusion with the Douglas Bill—about which more is written later in this history—was rather predictable given the secrecy in which the Forest Service purposefully enshrouded the transfer and proposal for a new national forest and given the unofficial name attached to the proposed forest.

|

Brandeberry reported on a knotty communications problem between Eureka

and three of the districts...

|

Brandeberry came up short when canvassing the Eureka area for suitable space for the supervisor's office. Until something better could be found, he recommended either two available rooms in the 4th and E streets Bank of America Building or "a street floor room in the new theater building." He had no better luck in locating adequate employee housing. . . .

Vacant houses for rent have disappeared and turn-over from sales are pyramiding. A federal housing project is located in southwestern part of town with a long waiting list of possible tenants.... With present demands, only veterans' applications are now being accepted. . . .[I]f any of our personnel are veterans, there is reasonable expectancy to be able to get in here within a month or so [Brandeberry 9-25-46].

Administratively, Brandeberry reported on a knotty communications problem between Eureka and three of the districts traced to the absence of good commercial telephone connections between Eureka and the forest lines from Orleans, Salyer, and Mad River. Installation of radios was not a complete solution since experience had indicated communications black zones around Eureka that could not be completely remedied even with more powerful equipment.

Opening the Doors at 4th and E

Streets. . . to the Anonymous National Forest

Meanwhile, as these preparations were being made, the new national forest remained anonymous. Presidential Proclamation 2733, establishing the new national forest, had been ready to issue for several months; all that was needed was a name. [9] The naming was a convoluted process and, ultimately, "Six Rivers" was chosen, having been suggested by San Francisco author, Peter B. Kyne. Kyne's suggestion stemmed from the new forest's encompassing the watersheds of six major north coast rivers: the Eel, Van Duzen, Mad, Trinity, Klamath, and Smith (RJ 12-16-46: 6).

But before the name "Six Rivers" was settled upon, a host of other possibilities had been promoted. After shying away from the name "Northern Redwood" because of the confusion over the Douglas Bill and because only a tiny fraction of the new forest encompassed redwood-growing land, the second name selected for the new unit was the "Yurok National Forest." Named for one of the major Indian groups in the north coast area, its use was never formalized due to a twist of fate. In mid-October 1946, Regional Forester Stuart B. Show responded to Chief Forester Lyle F. Watts' question of: "What does the name 'Yurok' signify? Our understanding was that this new Forest was to be named the "Northern Redwood:"

The name originally proposed for the new national Forest was 'Yurok', that of an Indian tribe which lived in the general locality. We have purposely avoided any reference to the redwoods since the acquired area in the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit which would be attached to this forest is too small to have material influence on the establishment of boundaries.

Since the selection of the name 'Yurok' we have been grieved to learn of the death of Gifford Pinchot and believe that it would be a fitting memorial to give his name to the first national forest created since his death [Show 10-17-46; cf. Watts 10-14-46]. [10]

Indeed, selection of "Yurok" National Forest had been a political hedge: "Redwood" National Forest had been the earlier front-runner as a name for the new national forest but as Regional Forester S. B. Show noted:

We were inclined to avoid any reference to the redwoods since it would tend to create a connection in the minds of some local people with the hotly discussed Douglas bill [Show 10-23-46].

More will be said later in this history about the contentious legislation to which Show referred. But briefly, the bill had been introduced during 1946 and reintroduced in 1947 and 1949 by Representative Helen Gahagan Douglas, Congresswoman from California. It proposed creation of a large federal forest of about 2.5 million acres comprising a narrow band between Sonoma County and California's border with Oregon. Even though the land bases for the Six Rivers and the proposed Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial Redwood Forest were entirely distinct, the politics were indirectly linked, and the controversy that swirled around the Douglas Bill caught what would soon be called the Six Rivers National Forest in its wake. [11]

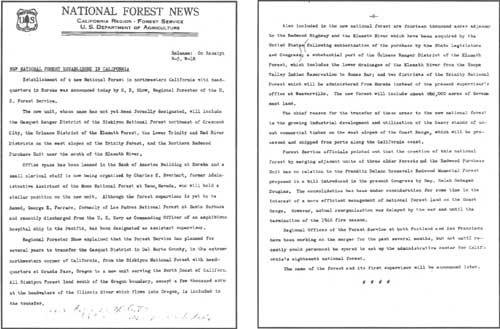

The Announcement is Finally

Made

Late in October 1946, an official press release was finally issued by Regional Forester Stuart B. Show formally announcing establishment of the new, still anonymous national forest with its headquarters in Eureka. [12] The Regional Office had actually wished to suspend this announcement even longer, but officials were forced to make a public statement to curb the rumor mill. Speculation had undoubtedly been further fueled by Brandeberry's Eureka inspection visit, where he had met with Chamber of Commerce people, telephone company officials, real estate owners and agents, and others. W. I. Hutchinson, Assistant Regional Forester for Information and Education (I & E) in Region 5 wrote a memo to Region 6's I & E Division, October 25, 1946:

We had hoped to delay issuance of the news release announcing the new Forest headquarters at Eureka until the name of the Forest and the Supervisor could be announced. However, several recent news stories such as the attached and the spread of rumors identifying the new headquarters with the proposed Roosevelt Memorial forest necessitate release of a formal statement as soon as possible [Hutchinson 10-25-46].

Shortly after Brandeberry's trip, office space was leased and staff were beginning to filter into their temporary headquarters on the third and fourth floors of the Bank of America building at 350 E Street, on the corner of 4th and E streets in downtown Eureka. Though the forest supervisor had not yet been selected, the Los Padres National Forest's Assistant Supervisor, George E. Ferrare, had been assigned as assistant supervisor. [13] In the press release, Show revealed that the Forest Service had, for several years, planned to transfer Gasquet Ranger District in Del Norte County from the Siskiyou to "a new unit serving the North Coast of California." This new unit would also include 14,000 acres adjacent to the Redwood Highway and the Klamath River, a large piece of the Klamath National Forest's Orleans Ranger District, and two of the Trinity National Forests' districts. Show reported that the primary reason for the new national forest was the "growing industrial development and utilization of the heavy stands of uncut commercial timber on the west slopes of the Coast Range, which will be processed and shipped from ports along the California coast." With a statement that would be come a familiar refrain, the press release stated that the reorganization "has no relation to the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial Redwood Forest proposed in a bill introduced in the present Congress by Rep. Helen Gahagan Douglas." It was repeated that the move had been planned for "some time" and it was purely in "the interest of a more efficient management of national forest land on the Coast Range;" only the onset of World War II and then the end of the 1946 fire season had delayed making the change a reality (USDA, FS 10-29-46).

Only a week after the initial press release, another announced the selection of William F. Fischer, then supervisor of the Cleveland National Forest headquartered in San Diego, as the first supervisor of the new national forest. Fischer was a graduate of the University of California's School of Forestry at Berkeley. He began his Forest Service career in 1933 as a field assistant for the California Forest and Range Experiment Station and later served on the Plumas, Tahoe, Mono, and Shasta national forests. Raised in the Russian River area, he had some familiarity with California's north coast forests; his new assignment was effective December 1 (USDA, FS 11-7-46).

|

| The original staff and rangers of the Six Rivers National Forest... this photo was taken in May 1947 on the steps of the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest Station, near Klamath. Front, left to right: Ferrare, Quackenbush, Hotelling, Smith, and West. Rear, left to right: Hallin, Fischer, Everhart, and St. John. US Forest Service photo |

|

. . . Supervisor Fischer and his skeleton crew did not have a forest

name to inscribe on their doors or their business cards.

|

In early February 1947, Supervisor Fischer and Administrative Assistant Everhart drove to Grants Pass to meet with officials there and "more or less formally [take] over the Gasquet District." They hauled back case records and files to the Eureka supervisor's office and made arrangements for Ranger Quackenbush to spend the following week in Grants Pass to "complete the segregation of the remaining material to be transferred." Equipment was transferred as well as four mules and a horse that had been pastured at Medford (Fischer 2-6-47). Supervisor Fischer made a public announcement in April 1947 that the Lower Trinity and Mad River ranger districts would be formally transferred to the new Six Rivers National Forest on May 1 along with their current rangers and staffs. Apparently, transfer of these puzzle pieces were the last ones needed to complete the new forest. William Fischer was quoted:

The transfer of these districts will complete the set up of the Six Rivers Forest. We are now in a position to handle their administration from the Eureka office. As these areas are 'West Slope' districts and used primarily by residents of the Humboldt Coastal area, this change of administrative headquarters should prove a great aid to the general public and users of the land [WTJ 5-15-47].

Thus, from disparate fragments of other national forests, the Six Rivers became a long, narrow strip, extending from the Oregon border to within about three miles of the Mendocino County line. This 135-mile long forest ranged from 2.5 to 25 miles wide, with its eastern boundary following the main divide of the Coast Range. With an average growing season of 289 days, the Six River's climate was characterized by summer fog that lessened evaporation on the slopes facing the coastal plain.

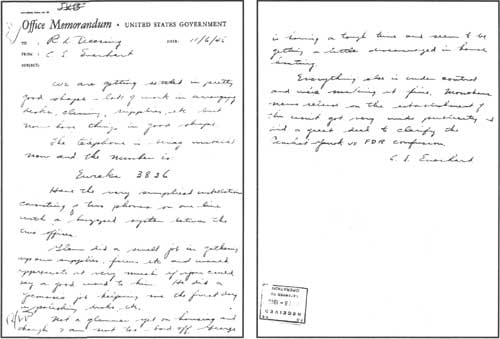

To date, the earliest piece of correspondence found from the new National Forest was an office memo dated November 6, 1946 to the Regional Office's R. L. Deering from the forest's Administrative Assistant, Charles L. Everhart. Passing along its first telephone number (Eureka 3836), Everhart relayed that the office was getting settled and that things were taking shape. He had no prospects on finding housing and noted that interim Supervisor George Ferrare was, likewise, "having a tough time...." He also reported that the "...news release on the establishment of this unit got very wide publicity and did a great deal to clarify the Pinchot - Yurok vs. FDR confusion" (Everhart 11-6-46). With the new forest having taken shape and the doors open for business, still, Supervisor Fischer and his skeleton crew did not have a forest name to inscribe on their doors or their business cards.

"Let's Limit Our Choice To A Good American Name..."

Replying to a request for suggestions in naming the new national forest, W. I. Hutchinson, the indefatigable Assistant Regional Forester for Information and Education, wrote a detailed office memorandum to the Assistant Regional Forester for Recreation and Lands. Hutchinson offered his opinion on several suggestions, but made it clear that his preference was to have the Eureka newspaper, the Humboldt Standard, sponsor a contest for deciding the name. He believed it would assure the higher ups in the Washington Office that "local and regional sentiment has been tested," and that it would engender a sense of ownership in the local populace.

According to Hutchinson, the three reigning principles for naming national forests and districts were that the name must be easy to spell, easy to write, and its significance should be easily understood. For all three reasons, he counseled against naming the place "Yurok." As for the "Redwood" suggestion, he thought it deceitful, since no significant stands of redwood were within the area that would ultimately comprise the national forest; moreover, it would get confused with the national forest unit being configured from the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit... the Forest and Range Experiment Station having already named its experimental substation there, the "Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest." Hutchinson thought the name "Humboldt" had merit, but discarded it because the neighboring region to the east already had a national forest named for this German naturalist. Though he thought it desirable to name a national forest for the recently deceased Gifford Pinchot, he agreed with Pinchot's widow, Cornelia, that the name "should be reserved for a more distinctive area, preferably one in which [Gifford] had a personal interest." [14] Though Hutchinson thought the name "Trinidad" had possibilities, he counseled that it could be confused with the "Trinity" National Forest. As for the name "Eureka," he strongly objected, saying that Crescent City residents and other "rival" communities along the north coast would be discommoded. Hutchinson endorsed considering the names "Bret Harte" and "Jed Smith," but believed other suggestions should be solicited either through the newspaper contest or by contacting key people outside of the Forest Service. His "key contact" list included the secretary of Save-the-Redwoods League, the California Historical Society, the Siskiyou and Shasta county historical societies, U.C. Berkeley School of Forestry, State senator and assemblymen, and historians Francis Farquhar, Erwin Gudde, and George Stewart (Hutchinson 11-12-46 and Kneipp 11-8-46).

|

| Charles Everhart's November 6, 1946 memo is the earliest piece of correspondence yet found from the new, Forest Supervisor's Office in Eureka. (click on image for a PDF version) |

With their correspondence obviously crossing in the mail, the Washington Office again pressed Region 5 officials to offer a name for the new national forest. Using what seems to be a specious argument, Hutchinson reported that the new forest did not embrace any "outstanding topographic feature or individual" and, therefore "the next best possibility is the name of a distinguished citizen of California." He, thus, proposed Starr King National Forest. "If the name of someone more intimately identified with the Coast Range is preferred," he alternatively suggested Josiah Gregg National Forest. [15] He again admonished to not name it "Yurok," underscoring that the Yurok homeland did not include the area to be embraced by the new national forest. Besides, R. S. Monahan, writing for L. F. Kneipp of the US Forest Service's Washington Office—after listing the names of the Indian groups that inhabited the territory of the new forest—intoned in his letter to the Regional Forester for California: "Let's limit our choice to a good American name associated with northern California!" (Hutchinson 11-18-46 and Kneipp 11-8-46).

It is apparent that Hutchinson communicated with at least a few of the people on his key contacts list in naming the new national forest. An undated letter from Erwin G. Gudde, editor of California Place Names, started his correspondence with:

I disapprove heartily of the conventional and unimaginative naming of our natural features by heaping one name on top of the other. I believe that it is our duty to transmit to future generations a California geographical nomenclature as diversified, interesting, euphonious, and historically justified as possible [Gudde 11-19-46].

Undoubtedly to Hutchinson's chagrin, of the names proposed, the one favored by Gudde was "Yurok;" his first and second choices were "Ehrenberg" or "Josiah Gregg" national forest. [16]

If nothing else, Gudde's suggestion that the new forest's name be "euphonious," became a buzz word. A November 19 office memo from Hutchinson documented his conversation with A. L. Kroeber, the eminent University of California at Berkeley authority on California's north coast Indians. Hutchinson relayed that Kroeber's suggestions of "Kotsaoo Weroi,""Perwer," "Kertser," "Chilula," or "Nongat" were "the most euphonious of the suitable Indian names" appropriate for the new forest. Euphonious, yes, but against the criteria of being easy to spell and generally understandable, they fell short (Hutchinson 11-19-46).

Regional Office officials were becoming impatient with the naming process because it was holding-up issuance of the official proclamation for the new national forest and, therefore, stalled its formal administration. As a stop-gap compromise, Regional officials proposed a list of tentative names with the right reserved "to propose a permanent name after a more thorough canvas has been completed." The Regional Office still favored a local contest to name the new forest which, they judged, "would do much to acquaint the people with the Forest. . . and to make them feel that the consolidated unit was their Forest." Their top three suggestions were Gregg, Smith-Gregg, and Gregg-Wood national forest. Other offered names were Six Rivers and Starr King (Thompson 11-19-46). The strongest local support was for Gregg or Gregg-Wood National Forest. Eminent Californians suggested the following: California Historical Society, Gregg; Francis Farquhar, Smith; Aubrey Drury, Smith-Gregg or Jed Smith; Kenneth Smith, Silcox; Peter Kyne, Six Rivers; Emanuel Fritz, Josiah Gregg, Pardee, or Jepson; Clyde Edmonson, Redwood Empire; and Phil Hanna, Josiah Gregg or Eureka (Thompson 11-19-46 and Tenare 11-20-46.)

Somewhat by default, Six Rivers became the name that stuck. Responding to the Region's November 19 letter, the Washington Office's L. F. Kneipp recorded that, if it was the Region's desire to adopt a temporary name, Six Rivers would be

...the most expedient. If the name of any individual or pair of individuals is initially adopted its subsequent abandonment almost certainly will provoke controversy and resistance. But nobody will go to war over the abandonment of Six Rivers.

Kneipp noted that, because of the importance of watershed protection and flood control to the area, the name Six Rivers had "much to commend it" and that "the connotations of such a name are pleasant and appealing" (Kneipp 11-26-46). In a follow-up letter, Kneipp wrote to the Regional Forester that the issue had been brought to the staff of the Washington Office and the consensus was to issue the proclamation or public land order with the name "Six Rivers" without reference to it being a temporary name. Kneipp noted that it would not preclude an eventual change in name if warranted (Kneipp 12-5-46). Thus, the name earlier posited by Peter Kyne, author of The Valley Of The Giants, Cappy Ricks, and other novels set in the north coast, became the official name of the new national forest. [17]

|

| Forest Service truck on the highway through the redwoods near Mill Creek. US Forest Service photo |

Redwood. . .

Redwood, though comprising only a sliver of the national lumber product, was a pivotal element of California's north coast economy. The stories of periodic and persistent surges to create a redwood national park, a redwood national forest, and a redwood experimental forest interwove with creation of the Six Rivers National Forest. Moreover, the special character of the redwood tree commanded world-wide interest in extraordinary ways that went well-beyond its qualities as lumber.

Redwood National Park

One of the earlier national park impulses was the 1920 "Redwood Resolution" (H.R. 159). The resolution directed the Secretary of Interior, under which the National Park Service is organized, to investigate...

as to the suitability, location, cost, if any, and advisability of securing a tract or tracts of land in the State of California containing a stand of typical redwood trees... with a view that such land be set apart and dedicated as a national park for the benefit and enjoyment of the people of the United States and for the purpose of preserving such trees from destruction and extinction....

Interestingly, the secretaries of Interior and Agriculture (the U.S. Forest Service is part of the Department of Agriculture) agreed that the Forest Service would make the investigation and complete the report required by H.R. 159, with final arrangements being made between District Forester Paul G. Redington and National Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather. Setting the tenor of the effort, final plans were made between Redington and Mather at a meeting of the Save-the-Redwoods League in San Francisco, October 4, 1920; field work began October 10. [18]

Having only one rainless day during the course of its fieldwork, the study team operated on a meager $400 provided by the Save-the-Redwoods League—Congress had neglected to earmark any funding for the task. After examining the lower Klamath River, South Fork Eel River, Prairie Creek, Redwood Creek and Big Lagoon areas, the committee recommended that the federal government acquire 64,000 acres in the lower Klamath River—8,600 acres of which were Indian Allotment lands. Additionally, an 1,800 acre administrative unit for the Redwoods National Park was to be established on the South Fork Eel River—land to be donated by the Save-the Redwoods League, private individuals, and perhaps, the State of California (Hammatt 1920:2, 4, 8) [19] Much of the land proposed for the Redwood National Park was owned by the Sage Land and Improvement Company and the Hammond Lumber Company. Contacted by the investigators, both companies indicated willingness to sell these lands to the federal government at "substantial reductions over actual values" (Hammatt 1920: 40).

Among the selling points of the lower Klamath were what the investigators termed the "dilapidated but exceedingly picturesque Indian rancherias" in the small openings along the river. Unwitting of their derrogatory language yet mindful of the cultural opportunities offered by the lower Klamath, they wrote: "In the smaller eddies one passes, now and then, Indian squaws (in their light and graceful redwood dug outs) pulling small salmon gill-nets." As another charm of the area, "Certain it is that the bucks are reliable guides and boatmen and good hunters and fishermen. The squaws are indefatigable basket makers, and both the territory and its native peoples offer exceptionally rich ground for those interested in Indian myths and customs." Moreover, the investigators reported that, in addition to the lands privately held by various timber and land companies, about 8,600 acres were composed of patented and unpatented Indian allotments, and that: "It is understood that the Department of the Interior has withheld issuing any further patents to these lands pending action by Congress on the question of establishing a park on the Klamath River. "Confident that they could acquire these patented lands for the park by repurchasing them at be low-market prices, they wrote that repurchases could be "at prices which, while making the Indian holders independent, will represent an extremely low price per M" (USDA, FS 1920: 14, 15, 18).

Another impulse to form a redwood national park was reported in a study completed in 1937. It quarreled with the 1920 report, contending that the recommendation to acquire the Eel River property was passeè—by then, it was largely part of California State Park's Humboldt Redwoods Park. Moreover, it argued that the lower Klamath River did not qualify as a Redwood National Park because it did not comprise "an outstanding and superlative stand" of redwood. Instead, the 1937 report recommended federal acquisition of the 17,760-acre Mill Creek Tract in Del Norte County (USDA, FS 1937: n.p.). Substantial expansions to this kernel of a park culminated a generation later.

|

| This steam donkey set at a redwood harvest operation graphically shows the aftermath of this destructive yarding method and of the effects of post-harvest intensive burning. This photograph was probably taken in the 1920s. US Forest Service photo |

A Redwood National Forest

|

. . . putting the timber land

under a sustained yield system would stabilize the area's lumber

industry without removing tax-paying lands from the county rolls.

|

Responding to the importance of redwood to the regional economy and grave concerns over the specie's long-term viability due to destructive logging and post-harvest practices, in August 1935, the National Forest Reservation Commission authorized land acquisitions for a northern and a southern redwood purchase unit (NRPU and SRPU) for the purpose of reserving coastal redwoods in their southern and northern range as a future national forest. The SRPU acquisition boundary encompassed about 600,000 acres; the smaller NRPU boundary embraced 263,000 acres. The first priority was on acquiring redwood lands within the northern purchase unit; and primarily because of the increased workloads created by the acquisition activity for the NRPU, a new Coast Ranger District, headquartered at Crescent City, was established on the Trinity National Forest.

Local opposition to the NRPU was most vociferous in Del Norte County, and much of the correspondence directed toward the Forest Service went to the Forest Supervisor of the Siskiyou National Forest, G. E. Mitchell. Mitchell was a strong supporter of the NRPU who believed it would be in the best interests of the county to have additional acreage under Forest Service management. Because the Forest Service focused on acquiring lands that were tax delinquent, he believed that putting the timber land under a sustained yield system would stabilize the area's lumber industry without removing tax-paying lands from the county rolls. Further, since back taxes had to be paid prior to the Federal purchase of the land, the county would garner that one-time benefit in addition to the payments to counties for schools and roads of 25 percent of Forest Service receipts. Nonetheless, mass meeting were held in Del Norte County to persuade taxpayers to oppose the NRPU. One of them, organized by the Del Norte Miners' Association, sponsored a February 1939 newspaper article that depicted a map of the acreage withdrawn by the government for national forest purposes within 50 miles of Crescent City, showing a ratio of 12 federal acres to each private acre.

|

. . . the Del Norte Central Labor

Council seemed generally supportive of the NRPU idea if. . .

|

In contrast, the Del Norte Central Labor Council seemed generally supportive of the NRPU idea—if the Forest Service could assure a reasonably prompt start of selective redwood logging on these lands in order to rapidly contribute to the county payroll (Coates 2-22-39). The agency hedged, saying that preparation of Forest Service timber sales was dependent upon the demand for the product....

To prosecute the industry of harvesting redwood timber on a plan that will mean the denuding of the lands and their reversion to brush and inferior species, is only a matter of destruction of a valuable resource.... We feel that if the business is put on a sustained yield basis it will stabilize not only labor but all the investments that are made in the County that are dependent on the timber resource. This will include stores, school, theaters, churches; homes, and recreational investments.... The best timber and the best timber lands in the county are now tax delinquent because they cannot pay a suitable profit to warrant the payment of their taxes.

Mitchell further explained that the federal government was seeking to "control a sufficient amount of [redwood growing] lands in order to deal with private interests." He offered the illustration of how the government had failed in its attempt to harvest Port Orford cedar on a sustained yield basis because it managed only about a fifth of the remaining stands. So, while loggers on private lands were over-cutting its sustained yield capacity by about three-fold, the Forest Service was powerless (Mitchell 2-24-39)

|

| Gasquet Ranger Station's satellite office in Crescent City, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. This photo was taken in 1955. After the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit lands were no longer being held for a potential redwood national forest, this building was donated to Del Norte County fairgrounds, where it still stands. US Forest Service photo |

Despite opposition, the Forest Service began its redwood land acquisition program and zeroed-in on the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit. The assiduous work of Forest Service lands examiners and negotiators had results: In 1941, the National Forest Reservation Commission reported acceptance of title to 10,704 acres of redwood lands; 4,666 additional acres of redwood timberland were approved for purchase by the commission for the NRPU:

This area, which lies north of the Klamath River in Del Norte County, Calif., is the nucleus of a national forest in the coastal redwood type. Although the area acquired is relatively small, the assets thereby accruing to the public are substantial, as the purchased lands bear an estimated mill-cut volume of 685,000,000 board feet, of which over 85 percent is redwood. Acquisition of these lands is gratifying, but if the minimum acreage necessary to form a desirable administration unit is to be assembled in a reasonable period of time an accelerated program must be made possible. A portion of the purchased redwood lands, with others to be acquired later, [sic.] have been designated as the Yurok Experimental Forest, and will be developed as a research area for the exploration of problems in silviculture and forest economics relative to the redwood type [US Congress 1941: 5-6].

In 1944, Vern Hallin transferred from the Lassen to the Trinity National Forest as the District Ranger of the NRPU [20] But World War II had interrupted the acquisitions program for the NRPU, and war's end brought new preoccupations and priorities in public land management. The post war economic upswing and its attendant skyrocketing demand for wood products made additional land purchases less likely and, when they could be negotiated, exceedingly costly (Conners 1995: 6, 12). After the war, a few more acquisitions were made, but the strong wind propelling the idea of a redwood national forest simply fizzled. Of approximately 46,000 acres under contract to the government for the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit, only 14,492 acres had actually been purchased by the close of 1946. As reported by Ranger Hallin in an acquisition report in January, 1947:

Options expired, and the vendors, no longer under obligation to sell to the government, but after consultation with Forest Service officials, took advantage of the opportunities offered them to dispose of their lands to operating concerns attracted to the redwood region through depletion of stands of timber in the Pacific Northwest and the great demand for timber occasioned by the war (Hallin 1947).

In 1948, when Hallin was transferred to the Six Rivers Supervisor's Office as its Resource Officer, Ted Hatzimanolis took the reins at the NRPU; ironically, these lands would later become trading pieces for coalescing lands for an expanded redwood national park. [21]

An Experimental Forest

Adding to this complex weave of events in the north coast redwoods, creation of the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit also entwined with establishing the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest as a substation of the California Forest and Range Experiment Station (CF&RES). For many years, the Forest Service's CF&RES sought a substantial tract of redwood where researchers could better unlock its silvicultural secrets and encourage the lumber industry to apply harvest and post-harvest practices that would insure healthy, productive, second-growth redwood stands for the long term.

|

In contrast to those who urged redwood preservation, the Forest

Service's official stance was an interesting combination of both

resignation and a call for action.

|

In contrast to those who urged redwood preservation, the Forest Service's official stance was an interesting combination of both resignation and a call for action. Early studies of the coastal redwood initiated by the CF&RES led to some eye-opening conclusions. For example, after inventorying the scant 1.5 million acres of coast redwoods that grew in a narrow swath between Oregon's Chetco Creek and California's Monterey County, it was discovered that a fully stocked cutover redwood stand at 50 years old annually produced a phenomenal 1,500 to 2,300 board feet per acre; however, it was demonstrated that such second growth stocking conditions were rare, with only 150,000 of the 550,000 acres of cutover land in "reasonable productive condition." Further, to sustain the annual redwood production rate at its 600 million board foot level, one-million acres of redwood lands would be needed to maintain the industry. To make the sustainability of redwood even more tricky, of the slightly over 1.5 million acres of redwood land, 1.4 million acres were privately owned (Person 1940: 2-5).

For researchers at CF&RES, the implications were crystal clear: the redwood industry was crucial to northern California's economy and, to assure its survival, the remaining 850,000 acres of virgin redwood lands must be harvested by means that maintained their productivity. To further investigate methods that assured productivity and to convincingly demonstrate research findings to industry, experimental forests in the two principal coastal redwood regions must be established and staffed with scientists...and it must be done with all due speed. As CF&RES Silviculturist Hubert Person wrote in his ground-breaking report: "It is believed that because the redwood operators are primarily interested in profitable liquidation, the development and demonstration of silviculturally adequate harvest cutting practices must depend on public agencies which at the present time means principally the California Forest and Range Experiment Station." Because the more general studies had largely been completed through the 1930s, the Redwood Management Division at CF&RES was ready to:

|

The California Forest and Range Experiment

Station's Redwood Management

Division was ready to undertake studies of a more intensive, long-range

character. . .

|

...undertake studies of a more intensive, long-range character, which can be prosecuted most effectively in an experimental forest... these experiments should take into consideration marking, logging, slash disposal, natural reproduction establishment, yield and fundamental ecological problems, all of which are affected by method of cutting [when converting virgin stands to productive cutover stands]. It is proposed to establish the northern experimental forest first because the results would be applicable to the area now supporting at least two-thirds of the present lumber production, and because the redwood acquisition program is at present limited to the northern unit [Person 1940: 2-5].

All The CF&RES Needed Was Its Own Redwood Experimental Forest. In contrast to movements pushing to create a redwood national park, for the CF&RES and Forest Service, the redwood question was not one of old-growth preservation for the sake of tourism, aesthetics, or even for the sake of study. Instead the redwood question was primarily one of the long-term survivability of a key California industry. For the Forest Service, disappearance of redwood old-growth stands was not the problem; maintaining productive redwood forests through successful conversion of virgin stands to highly productive second growth, was.

|

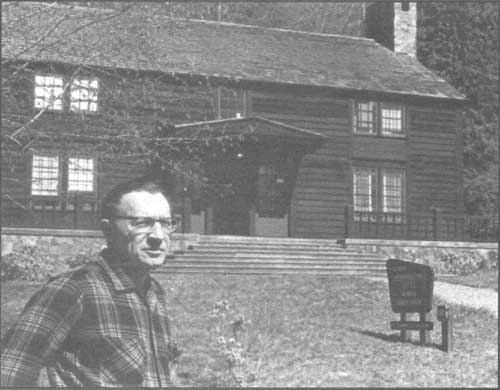

| Ken Boe, in 1969, at the CCC built Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest administrative building. Unusual for Forest Service architecture, this building references both Colonial Revival and Forest Service Rustic styles. Originally built as the YREF office and dormitory, it later became both the Experimental Forest and the Redwood Ranger Station offices. Even later, it was the office for the Redwood National Park. Currently the Yurok Tribe uses it for administrative purposes US Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station photo |

|

For the Forest Service, the redwood question was

primarily one of the

long-term survivability of a key California industry.

|

Initially, the CF&RES endeavored to establish its experimental forests independently, unfettered by creation of any national forest in California's coastal redwood belt. Ground work for these acquisitions was laid at least by September, 1933 through CF&RES Redwood Management Division. By late 1933, the station had forwarded three proposed acquisition areas to the Director of Research E. I. Kotok: Casper Experimental Forest, located 20 miles west of Willits; Van Duzen River Experimental Forest, located just southeast of Eureka; and the Weott Experimental Forest (Person 1940:1). Unable to cinch a deal on any of these lands—and seeing the growing support for a much larger redwood national forest—it was decided that one or more experimental forests could be carved from the impending redwood purchase unit acquisitions. But as early as March, 1935, CF&RES officials had become frustrated in their attempts to acquire a redwood experimental forest by riding the coat tails of the Redwood National Forest movement. Person complained in a letter to H. W. Cole of the Hammond & Little River Redwood Company of San Francisco, with whom he had been negotiating for lands in the Van Duzen and Eel River areas: "The delay in this acquisition [of a Redwood National Forest] may make it desirable to return to our original idea of acquiring an experimental forest independently." Person noted that: "Recent developments have convinced us that, because of the greater production in Humboldt County [compared with Mendocino County], as well as the much greater timber resources and the recent interest shown in improved methods of logging, the Humboldt area would be most favorable for the undertaking of long-term redwood management studies." Person also explained that: "From the standpoint of the administrative branch, there was an objection to the Van Duzen area because of the fear that the National Park Service might take over a large part of this area for purely park purposes. It is believed however, that an experimental forest could be selected from the Van Duzen area which would be free from this objection and otherwise the area is highly desirable" (USDA, FS Person 3-11-35).

When on August 29, 1935 the National Forest Reservation Commission established purchase area boundaries for a Northern Redwood Purchase unit of 263,000 acres and a Southern Redwood Purchase unit of 600,000 acres, Forest Service officials then focused their efforts within these broad zones with the ultimate aim of forming a manageable national forest unit. Out of these lands, CF&RES would be able to demarcate its experimental forests.

By September, 1935, Person at CF&RES had assembled data on four areas suitable for experimental forests: two proposals within each of the purchase units established by the Commission. The two proposals in the SRPU were Deer Creek, located 20 miles west of Ukiah, and Gualala River, about eight miles northeast of the town of Gualala. In the NRPU the proposals had been whittled down to what was called the Del Norte Experimental Forest, about five miles north of the town of Klamath, and the Prairie Creek Experimental Forest, located a few miles north of Orick on the lower stretches of Lost Man and Little Lost Man creeks and tributaries of Prairie Creek. The NRPU proposals, although they included "[e]xcellent virgin stands, representative of the various conditions found in the northern redwood region," Person found lacking as an experimental forest because they included very little second growth. He consequently developed yet another proposal, outside of the approved NRPU boundary, in the cutover stands in the Humboldt Bay vicinity (USDA, FS Person 9-25-1935).

|

The part of the High Prairie Creek watershed east

of Highway 101 was

approved as an experimental forest, to the extent that those lands had

been or might be acquired by the Forest Service.

|

Negotiations with various redwood timber land owners by Forest Service officials for the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit reaped acquisitions in Mynot, Hunter, and Turwar creek watersheds. Meanwhile, the experiment station pushed for a redwood experimental forest, and a direct proposal was forwarded in a September, 1939 "Memorandum for Director" (Person 1940: 1). Following-up on this memo, January 15, 1940 the Regional Forester, the Director of the CF&RES and other key parties in the regional office and experiment station met in San Francisco. As a result, the part of the High Prairie Creek watershed east of Highway 101 was approved as an experimental forest, to the extent that those lands had been or might be acquired by the Forest Service (Person 1940: 2-5).

Within a couple months after his January 15 meeting, Person reported on the "Proposed Northern Redwood Experimental Forest." By this date, 643 acres in the High Prairie Creek area had been acquired or was authorized and in the process of title transfer. There was an additional 1,552 acres of privately owned redwood land that was earmarked for the Redwood Experimental Forest and which was part of a 27,000-acre parcel under agreement to sell to the US Forest Service for an agreed upon price (Person 1940: 7). As noted above, in 1941, Congress approved the National Forest Reservation Commission's recommendation to accept title to 10,704 acres of redwood lands, and an additional 4,666 acres of redwood timberland were approved for purchase for the NRPU; from that, the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest was formed.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

5/six-rivers/history/sec1.htm Last Updated: 14-Dec-2009 |