|

A History of the Six Rivers National Forest... Commemorating the First 50 Years |

|

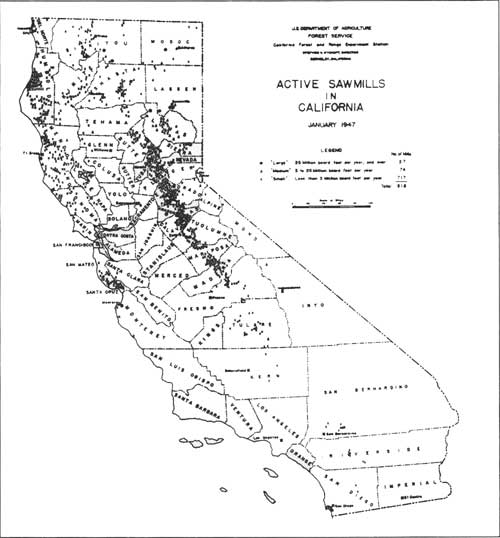

Gearing Up for Intensive Timber Management

A Bare Bones Organization

On January 30, 1947, prior to the official establishment of the Six Rivers, William F. Fischer wrote a memorandum to the Regional Forester outlining the organizational scheme he envisioned for the new forest. Fischer expressed a preference for smaller districts over large ones and staffing set at low levels with the flexibility to expand with the workload. The top three jobs he saw for the Six Rivers were securing and organizing the working tools necessary for administration, learning the forest, and running the business of operating the forest. Since all of these were entirely unknown quantities and all were formidable tasks, Fischer wrote that "[t]he organization must be set up to do the three jobs and to grow into the work over a fairly short period rather than all at once. The initial organization proposed is a skeleton one for the foreseeable job ahead and may be expected to expand..." But while Fischer had some influence over the shape and size of his organization at the supervisor's office in Eureka, staffing and organizational structure on the four districts was inherited from the three parent forests.

|

The top three jobs he saw for the Six Rivers were securing and

organizing the working tools necessary for administration learning the

forest and running the business of operating the forest.

|

In the Supervisor's Office, Fischer proposed three clerks and a warehouseman in addition to his staff officers. The timber management load was characterized as moderate to light, but with "considerable more business anticipated in the near future." The range management load was seen as light. Both the wildlife and recreation management programs were characterized as "probably high," while the fire job was perceived as moderate. Land use was seen as "comparatively light but building up very rapidly," while land acquisition posed a "big job on the Redwood Purchase Unit." The anticipated work load in watershed management was viewed as being potentially high, considering power proposals, relationships with fisheries, and the lack of reliable water-related information. While the engineering job was seen as "normal," the information and education load was seen as enormous and important but "so lightly touched by the Forest Service." Major staff assignments were divided among the administrative assistant, assistant supervisor and forest engineer (Fischer 1-30-47: 1-3).

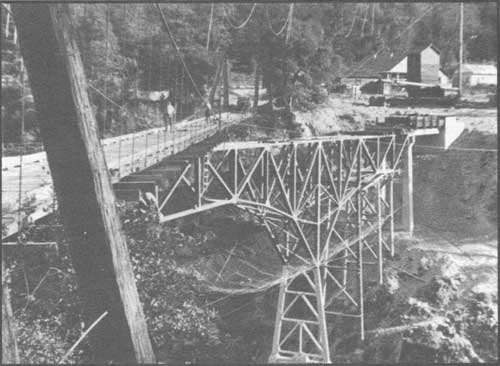

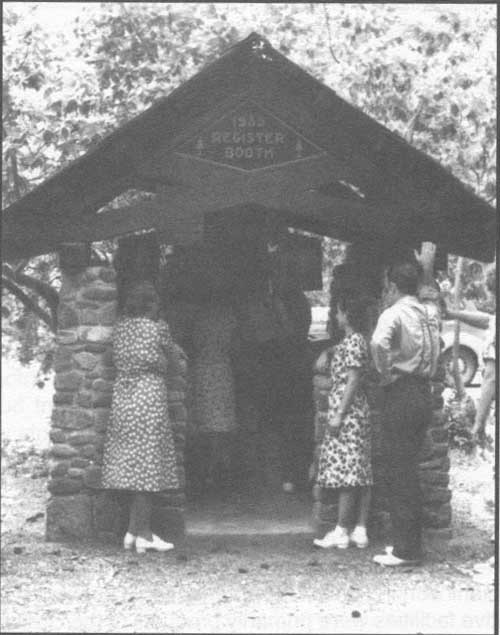

When the Six Rivers was created, it also inherited preexisting administrative sites—parts of other national forests—that needed to be remelded into an efficient working unit. Like other national forests in California, the administrative facilities were primarily products of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and other, related New Deal programs. Therefore, most were 10 to 14 years old. Programs such as the CCC were responsible for literally putting a new face on the Forest Service by replacing most of its old and highly individualistic structures, dating from the early years of the twentieth century, with a suite of buildings that used standard, regional, designs—many of which were constructed from "ready-cut" materials. As Ranger Wesley Hotelling put it: "During this period [the Great Depression, for] the next 5 or 6 years, there were young men available for all projects that we could think up" (Hotelling 1978: 91). The same held true for Region 6 to the north, from which Gasquet Ranger District was added to the Six Rivers. Like California, Region 6's building program exploded with the labor force and material support provided by the CCC and related programs. [22]

|

| This 1937 photograph shows the Civilian Conservation Corps' construction of the Salyer Bridge. Aimed south, note the old suspension bridge still in-place and the safety net below the new bridge. Courtesy of Robert Albrecht |

|

| The CCC-built Patrick Creek Campground was an elaborate development along the Redwood Highway. In addition to this 1935 Register Booth, the campground also included a developed swimming hole with a diving board, a bridge, extensive rock walls, a rock-walled bathhouse and restrooms, Klamath stoves, and a rock-lined semi-subterranean campfire area. Though many of these features have been destroyed by periodic, severe floods, the campground remains a testimonial to the CCC's accomplishments. This booth still stands. US Forest Service photo |

Though the infra-structure inherited from the depression-era construction programs was similar to that existing on other national forests in the far west, there was a crucial difference for the Six Rivers: it was not integrated on the basis of a single, national forest unit. Having come from three national forests in two regions, developments had no cohesive plan when looked at on a forest-wide basis. For example, the transportation system was not designed to cope with or promote movement toward the coast; instead, most of the forest roads were oriented to sawmills, transportation systems, and markets in Grants Pass and California's Central Valley. Similarly, there was a lack of cohesion in the trails system and in the placement of lookouts and guard stations for fire protection. Communications were similarly hampered by the nature of the Six Rivers' origin. Administratively, ways of conducting forest business were different and took time to reconcile. Fischer and officials in the Regional Office recognized most of these built-in difficulties, yet viewed them as inconsequential when compared with the greater good they envisioned. [23]

|

| The new Six Rivers National Forest struggled with its marginal and eastward-oriented infrastructure for many years. This 1934 photo shows the CCC enrollees from Camp Mad River taking a break from their road-building chores in the Van Duzen River Valley. Courtesy of John McGrath |

Forest Service Missionaries... Bringing the Word

of Forestry to the North Coast

Why create a new national forest from existing ones? No land was added or subtracted from the Forest Service land base by the transaction; no administrative sites were added or deleted; with few exceptions, personnel on the existing districts stayed put and simply transferred to the new national forest; no services were consolidated.

During the idea stage for creating this new national forest and during the early years of World War II, there was a renewed conviction and urgency that forestry was a key ingredient for the prosperity and security of the nation. Scores of publications pointed to renewed concerns about timber depletion and to the practice of forestry as the antidote. While serving as Acting Chief of the Forest Service, Earle H. Clapp wrote the foreword to a 1941 agency publication titled New Forest Frontiers for: Jobs, Permanent Communities, A Stronger Nation. A remarkable period piece, this illustrated booklet placed forestry in the context of war and national security:

Much of our rural poverty is within forest regions with large areas of poor soils.... Wretched living conditions mean abject people. With nothing to defend and morale gone, no people could fight long against an invading enemy.

Battles on the economic front never cease; they are more devastating during war, to be sure, but relentless even during peace. So a country should never be caught without a full measure of the services and products supplied from forest lands....

Somehow, sometime, this Nation will realize fully its dependence upon forests in both peace and war. It is already moving in the direction of forest conservation, dangerously slow to be sure, and the longer the delay the greater the cost... [USDA, Forest Service 1941:1].

|

| This page from the 1941 USDA, Forest Service publication, New Forest Frontiers for: Jobs, Permanent Communities [and] A Stronger Nation, shows how management of the nation's forests was defined as a choice between depletion or abundance. It is apparent from the caption that the memories of the Great Depression were fresh and that wartime defense was foremost. |

Though written a half dozen years before the Six Rivers' proclamation, this publication reflected the tenor of the Forest Service's fight to stay in the public and political eye as an agency that was deeply concerned about forces that threatened the nation's fundamental economic and social well-being and promoted an agenda to do something about it. Regarding rural communities, Clapp's comments would have had special meaning to those living on or adjacent to lands that would be subsumed by the Six Rivers. Even as late as the mid-1990s, the population in the counties directly influenced by the Six Rivers comprised less than 20 percent of the state average; 62 percent of the people lived in rural areas or small communities of 3,000 or fewer inhabitants (USDA, FS 1995:III 6-8).

|

Why create a new national forest?

|

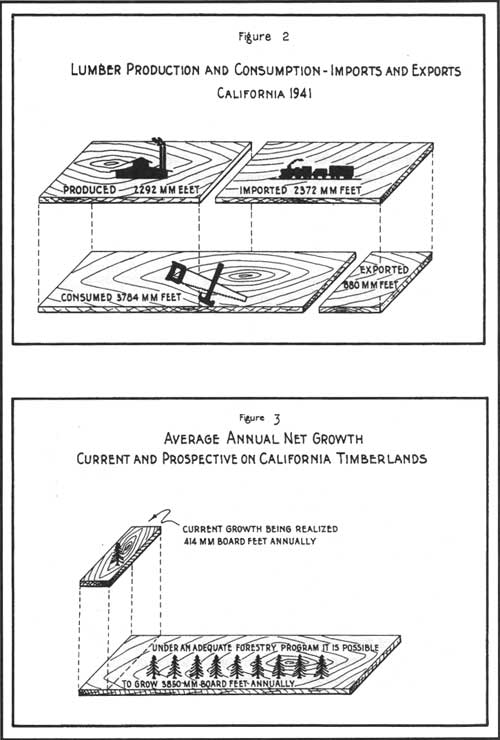

To the question: Why create a new national forest?, another facet of the answer—from a state-wide perspective—is reflected in a 1944 study completed by a consortium of government and educational entities, including the Forest Service, University of California, California State Farm Bureau, Soil Conservation Service, and Bureau of Agricultural Economics. The lengthy report stressed the imperative to anticipate and prepare for the post World War II demands for wood. It found that the demand for wood would be far greater, "both in scope and quantity, [than] anything that has occurred in the past." Despite the predicted application of wartime technology spin-offs to partially or wholly replace certain products traditionally made from wood—such as greater use of new plastics and synthetic replacements for wood alcohol and acetone—the researchers envisioned tremendous pressures on California's forested lands to produce wood. They worried over the figures showing that California had only 7,800,000 acres of stocked commercial timberland. Although 70 percent of this land was in government holdings, a large proportion of the timber on these lands was economically not feasible to harvest, either owing to stand composition or to lack of accessibility. The problem looked even more acute when the researchers compared the total area of cutover lands with the acres of cutover land that showed "some degree" of restocking: 11,900,000 to 5,200,000 acres. Further, 50 sawmills in California produced over 90 percent of the state's cut, but 20 of these mills, representing 25 percent of the annual cut, were forecast to either dissolve or move to less desirable locations within the coming decade due to exhaustion of their local timber supply. The researchers believed that, if immediate steps were taken toward intensive management, the state had sufficient timber lands to supply most of its local needs. Without implementing known silvicultural practices, they predicted that the remaining virgin stands would be cut over by 1979 (USDA, RICC 1944: Forest Lands Section 29-30).

This viewpoint was completely consonant with that advocated by the Chief Forester during the post-war period, Lyle Watts. An exhaustive report commissioned by him concluded that the nation had to develop productive forests...

to meet new international obligations and to help establish the peace. . . . One fact stands out clearly: this country needs to produce and to use in full measure the products and services of its forests as a part of the larger obligation to gain a stable, prosperous economy and hence a better hope for world security.... Development and intensified management of the national forests should be vigorously pushed [USDA, FS 1948:2, 11]. [24]

Unlocking the full timber resource potential of California's Northwest and providing for productive second growth forests were viewed as key links in this plan.

From a more local perspective, Region 5 officials articulated four main reasons for creating the Six Rivers National Forest. Topping the list was: "To bring forestry to an area long neglected - and where it was badly needed." This prime motivation was followed by:

2. To bring a knowledge of the Federal Forest Service to a large group of people whose livelihood and interest lay mostly in forests.

3. To tie a forest resource more closely to the population which depends or will eventually depend upon it.

4. To bring more effective administration to districts far remote from existing administrative centers [Cronemiller and Kern 1949: 2].

A local newspaper article provided a retrospective on why the Six Rivers was created from its existing neighbors to the north and east:

As early as 1938 it was recognized that the growth and development of the coastal area of Humboldt and Del Norte counties would create a demand and a need from this area for the development and use of the resources of these lands. The various units were then being administered from distant inland valleys difficult to reach from the coast. In line with the National Forest policy of decentralization and management on the ground, the move was started to establish an administrative center on the coast. About the time the preliminary job to accomplish this reorganization was completed, the war intervened and the matter was tabled in the interests of the war effort. However, the war accelerated the need and as soon as was possible, at the end of the conflict, the change was made. [25]

|

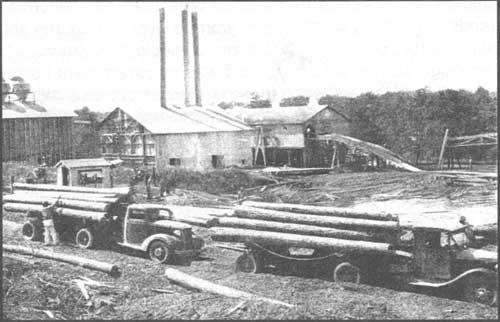

| This graphic from the Preliminary Report, Post War Program for Agriculture, California written in 1944 depicts the imbalance between the amount of lumber produced and consumed in California (Figure 2) and the disparity between the state's timber growth potential with its actual net growth (Figure 3). These realizations spurred the impulse to create the Six Rivers National Forest—a forest whose primary mission was to bring the practice of forestry to California's northwest. |

Forging an organization to accomplish this work was a daunting job. Although the lands comprising the Six Rivers had long been under the wing of the Forest Service, they had been neglected step-children: too far from the centers of activity to capture the sustained attention of their parent forests. Formation of the Six Rivers created a new orientation; the general flow of goods and services from the forest would be to the west rather than toward the Central Valley. The lands were no longer the outskirts of three other administrative units; instead, they had a new identity and a new core.

"The Forest Situation in Humboldt

and Del Norte Counties..." Timber

During this period of post-war expansion for the lumber industry and formative years for the Six Rivers, The Humboldt Times ran a weekly column called "Log and Saw." It highlighted new rules and technologies, introduced the industry's key players and their operations, and encouraged new product developments. The Six Rivers also appeared in the column and, most commonly, promoted new developments in logging and utilization that promoted sustained yield objectives. Fischer kept in the public eye by regular pieces in the column, addressing such subjects as the desirability and profitability of selective logging, lopping and scattering slash, and minimizing fire risk in logging operations (cf. HT 4-7-47, 10-10-47, 10-17-47). A prime subject in "Log and Saw" for two weeks running was the report: "The Forest Situation in Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, 1947." Released in late July, the report indicated that at the current rate of cutting, the old-growth would be consumed in 60 years in both counties and that the lumber industry would then shrink by as much as 50 percent. The report characterized the current logging practices as "poor to destructive," leaving 80 percent of the land in poor productive condition. A 1945 forest survey found a scant 1.5 percent of cutover land left in good condition, indicating good cutting practices; 19.6 per cent left in fair condition; 78.5 percent in poor, and 4 percent in destructive condition (HT 10-3-47, 10-10-47).

|

The Forest Situation report was undoubtedly

written with the purpose of

illuminating the potential of the north coast and promoting federal

forestry as the means of unlocking the area's potential

|

The "Forest Situation" report was a remarkable and wide-ranging work that seemed to have been influential. The report was undoubtedly written with the purpose of illuminating the potential of the north coast and promoting federal forestry as the means of unlocking the area's potential—particularly with regard to the timber industry and the social and economic windfall to be derived from a healthy, sustained enterprise. Clearly, timber was the major issue in this publication; it included sections and commentary titled: Timber Resources, Drain (on timber resources, i.e., harvest), Sawmill Situation, Commercial Timber Sales, Working Circles, Range Resources, Recreation, Wildlife, and Administration and Protection Improvements. Bullet statements from that report illuminate how the Six Rivers perceived the playing field in which it operated:

|

Highlights from the Forest Situation Report

illuminate how the Six

Rivers perceived the playing field in which it operated . . .

|

The Six Rivers was composed of 1,147,672 acres, exclusive of the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit (NRPU). Eighty-seven percent of this was government land and 13 percent was alienated. Forty-six percent of the forest was classified as operable commercial timber land; 19 percent classified as unusable range; 32 percent as "protection forest;" and three percent as private recreational, grazing, and other agricultural lands. The NRPU comprised an additional 14,492 acres (USDA, FS 1947: B 1).

Seventy-two percent of Humboldt and 63 percent of Del Norte County was timber land.

Since 1920, the average annual timber harvest for Humboldt County was 366,000,000; 16 mmbf for Del Norte County. [26]

1945 production, primarily from old-growth, was 455 mmbf in Humboldt County; 24 mmbf in Del Norte.

Inaccessibility was the chief factor in holding down past production.

At the current rate of harvest, old-growth stands will last about 60 years in both counties. Afterward, income from the lumber industry is expected to drop by 50 percent.

Referencing the 1939-'40 census, 48 percent of Humboldt County's working population was employed for, or in support of, the lumber industry; 16 percent of Del Norte's working population was timber-dependent.

In 1947, there were 11 sawmills in Del Norte County where only three had existed before 1945. As of October 1946, Humboldt County had 103 sawmills and 23 shingle mills. Of these mills, only 58 had existed prior to 1945. Most of the lumber companies that had moved into the area were from Oregon and Washington "where accessible private merchantable timber is becoming scarce."

If running at capacity, the largest mills could cut half of the total annual capacity. Those mills were: two Hammond Mills, Holmes, Eureka, Northern Redwood (at Korbel), two Pacific Lumber Mills, and Dolbeer-Carson (USDA, FS 1947: A 1-3).

There were 21 mills—plus three on the Hoopa Reservation—within two miles of the national forest boundary, with 14 cutting less than five mmbf per year; in 1947, none of them were cutting national forest timber (USDA, FS 1947: B2).

To change cutting practices in order to leave cutover lands in satisfactory productive condition and to improve utilization, the Six Rivers' general recommendations were:

-Major tractor and not major steam donkey use;

-Selection cutting rather than clear cutting;

-Partial slash disposal instead of broadcast burning, with intensified protection for the first few years after selective logging;

-Refuse to sell National Forest timber to companies that habitually use destructive logging practices on their own lands (USDA, FS 1947: A 4-5).

Rough inventories indicated that the bulk of the timber resource was old-growth with "Douglas fir composing 80 to 85 percent of the stand." Only 16 mmbf of government timber on 1,675 acres had been cut in past commercial sales from lands composing the Six Rivers. It was estimated that 50 mmbf were being cut on private land during the 1947 season by local mills. Therefore, the timber was estimated to last about 40 years, assuming current cutting practices and accessibility to the untapped timber (USDA, FS 1947: B 1).

The potential annual national forest timber harvest on the Six Rivers, under sustained yield, could be 1.5 percent of the gross volume for the entire area, or 125.5 mmbf per year. Overall, the prescription for the first 15 to 20 years was to selectively cut largely defective trees of high value (USDA, FS 1947: B 3).

|

| This pair of photos is from a manuscript by Hubert Person and William Hallin published in 1942 and titled "Possibilities in the Regeneration of Redwood Cut-Over Lands." The photo depicts slack-line yarding, a method in which the authors noted: "It is practically impossible to practice tree selection or [to] reserve seed trees" This newly-logged area shows the virgin redwood stands in the background and to the right, beyond the steam donkey. |

|

| This photo illustrates the virtues of tractor yarding compared with lands logged using powerful and destructive high-lead and slack-line yarders. The authors blamed part of the public's indifference to sustained timber production in redwood forests on faith in the tree's exceptional sprouting ability and the favorable soil and climate of the redwood region; a faith that encouraged a belief that scientific management was unnecessary to insure a sustained redwood supply, US Forest Service photo |

"The Forest Situation... Range"

The "Forest Situation Report" also addressed range management. Although grazing was a "relatively unimportant" activity on the Six Rivers, its regulation raised a disproportionate share of criticism and resistance from those who used the forest lands for range: primarily grazing cattle and sheep, but also horses and pigs. The 1947 report reflected that the new forest's usable range totaled 220,850 acres for an estimated 18,000 animal months. The majority of range land was on the Mad River Ranger District, having 155,000 acres providing a potential of 14,940 animal months. There were 28 allotments altogether on the forest, with 18 on Mad River, seven on Lower Trinity, one on Orleans, and two on Gasquet. There were 48 actual grazing permits issued for 2,791 cattle, totaling 15,280 animal months; Mad River had the lion's share, with 2,127 permits for 12,763 animal (cattle) months. Range improvements on the forest were confined to salt logs, drift fences, stock driveways, water developments, erosion control, range re-seeding, Klamath weed control, and Larkspur eradication (USDA, FS 1947: B 4).

|

Characteristically using timber as the qualifying factor, the definition

of "permanent range" was land that produced "grass or browse better

than anything else, and would yield, if used to grow timber, only a

marginal product at best."

|

While acknowledging that the Six Rivers' range program was small, there were some serious problems of over-grazing that needed attention. One was the allotment between Flint - Elk Valley and the Harrington Ranch on the Orleans Ranger District: "The area is in a delicate ecological balance and should not be grazed by livestock at all" (Cronemiller and Kern 1949: 22). A year after the forest's first General Integrating Inspection, Supervisor Fischer wrote that the forest's objective in range management was to "maintain range use in line with the capacity of the permanent range, and to develop and improve the permanent range to its highest potential." Characteristically using timber as the qualifying factor, the definition of "permanent range" was land that produced "grass or browse better than anything else, and would yield, if used to grow timber, only a marginal product at best." Permanent range was calculated at 108,080 acres, but about 240,486 acres were used for grazing in some form; 2,400 acres were classified as being overgrazed government range. Grazing permits were allowed on the basis of two factors: dependency of the home ranch on the forest range, and ability of the land to support livestock part of the year on owned or controlled lands.

In 1949, 29 range allotments, 45 paid permits and 10 free grazing permits were issued on the Six Rivers. Fischer cited "abusive range use" as the cause of some of the forest's "most critical watershed problems." The characteristically more shallow soils on range land tended to be more susceptible to disturbance and slower to recover. Fischer pointed out that this fact was the root of the disproportionate time and effort expended in range administration given the relatively low number of livestock grazed on the Six Rivers and that the expenditures were justified owing to the watershed values at stake (Fischer 1950: 11-12, appendix table XI). By 1956, Six Rivers officials issued 63 grazing permits covering 2,400 cattle. The object was to regulate how much forage was used such that no more than a half to two-thirds of a year's growth was removed by grazing. If grazing exceeded those limits, the degradation to plant cover put watersheds in jeopardy (USDA, FS 1957: 3).

|

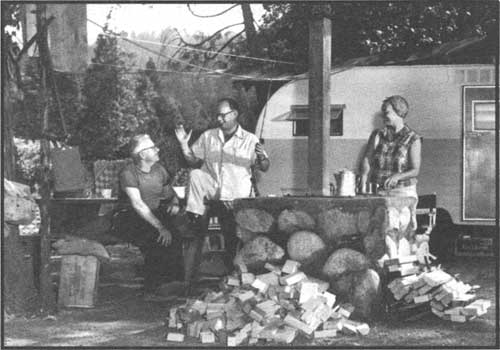

| This photo was staged to emphasize that California's national forests were places for recreation. As roads improved, trailer camping mushroomed and precipitated changes in campground design and amenities. US Forest Service photo |

"The Forest Situation... Recreation"

The "Forest Situation" report also underscored the importance of recreation on the Six Rivers—both existing and potential. Recreational use by tourists and local residents was characterized as "heavy." In 1947, there were 63 campgrounds having 405 units accommodating about 2,675 people. The writers of the situation report concluded that "demand far exceeded the existing facilities." By ranger district, the distribution of campgrounds was:

| campgrounds | units | est. daily capacity | |

| Mad River | 8 | 40 | 165 |

| Lower Trinity | 4 | 32 | 112 |

| Orleans | 2 | 38 | 113 |

| Gasquet | 49 | 295 | 2,265 |

The report deemed the "improvements on most campgrounds are in fair to poor condition due to inadequate maintenance funds." It estimated that 20 new campgrounds, with a capacity of an additional 500 people, were needed to meet normal demand, forest-wide.

In 1956, the Six Rivers hosted an estimated 109,000 recreational visitors. [27] By far, most were anglers, estimated at 58,000; the next highest number was an estimated 22,000 sightseers. After that came campers (7,590), hunters (6,000), picnickers (5,700), resort guests (4,500), winter sports enthusiasts (2,000), organization camp guests (2,000), and summer home users (1000) [28] Though these totals are small when compared with national forests in closer proximity to California's mega-urban areas—such as the Angeles, San Bernardino, and Eldorado (east of Sacramento)—they represented a 200 percent increase in recreational visits to the Six Rivers over the previous three years (USDA, FS 1957: 5). By 1958, a Six Rivers mimeographed handout listed only five developed campgrounds on Gasquet (Grassy Flat, Madrona, Patrick Creek, Shelly Creek, and Fish Lake), three on Lower Trinity (East Fork Willow Creek, Boise Creek, and Sawyers Bar), three on Orleans (Bluff Creek, Pearch Creek, and Happy Camp), and four on Mad River Ranger District (Mad River, Ruth, Watts Lake, and Van Duzen).

Likewise, pressure to define and lay out tracts for summer homes was on the increase since the end of World War II and "Rangers have been unable to meet this demand." [29] Alluding to the difficulties that arose from mining claims being used as the avenue to summer home ownership on national forest land, the report noted that: "Some parties have staked out mining claims primarily for the purpose of building a summer home or yearlong residence. On Orleans District alone, there are 28 mining claims, not considered bonafide, located on power withdrawals along the Klamath River and Red Cap Creek." [30] In 1947, the distribution of summer homes on a district basis was:

Summer Homes

| MR | LT | O | G | |

| tracts laid out | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| lots surveyed | 3 | 17 | 6 | 60 |

| lots occupied | 3 | 17 | 6 | 44 |

There was only one organization camp on the Six Rivers in 1947, but two new ones had recently been applied for. The Six Rivers had five recreation resorts under permit and demand for winter sports development was emerging—evidence the feasibility study for the Grouse Mountain Ski Area on Lower Trinity. Snow skiing was a burgeoning sport and national forests were experiencing phenomenal post-war growth in providing permittees with areas suitable for winter sports development; the closest to the north coast communities was at Mt. Shasta (USDA, FS 1947: B 5-6). The "Forest Situation" report provided recommendations about areas and capacities for new campground, picnic, hunter camp, and recreation residence tracts. While some of these plans materialized, others remain on the drawing boards.

|

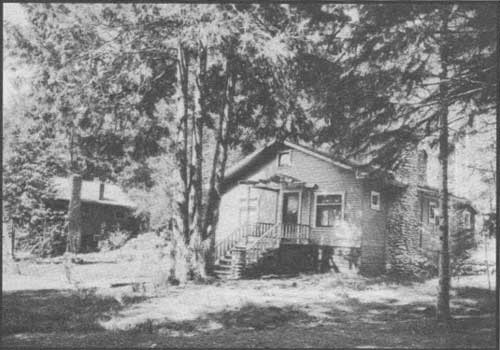

| Home 655 in the Gasquet summer home tract. This photo was taken in 1936, when Gasquet Ranger District was part of Region 6's Siskiyou National Forest. US Forest Service photo |

Of all the forest's districts, only Gasquet Ranger District had a recreation plan, with developments focused along the Redwood Highway. [31] Inherited from Region 6, the 1935 plan had only been deviated from when it "appeared desirable to issue a summer home permit in order to extinguish a mining claim" on land planned for a campground. Fully 75 percent of the existing campgrounds and all of the surveyed summer home lots on the Six Rivers were on Gasquet (Cronemiller and Kern 1949:15).

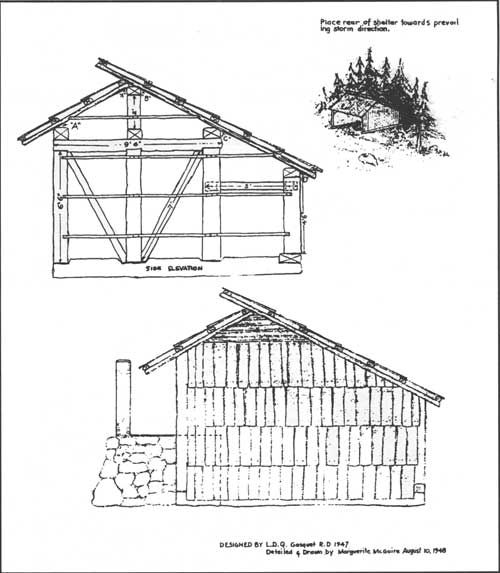

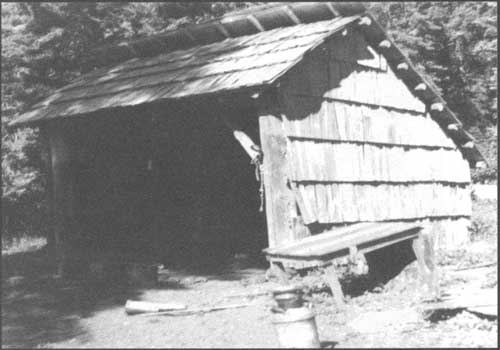

At hunter, angler, and hiker camps, Gasquet's Ranger Leo Quackenbush became well-known for his rustic trail shelters. His 1947 design reflected simplicity, utility, and ease of construction. At least four of them were built; three along the South Fork of the Smith River. [32] A less-known motivation for their construction was their service as "a barrier against mining claimants" (Cronemiller and Kern 1949:16).

Though development of campgrounds occurred on all the Six Rivers districts, they were most numerous on Gasquet and Lower Trinity, clustering along the main state highways, 199 and 299. The spurt of free campgrounds, or "public service sites," constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the depression-era met with stiff local opposition, primarily from owners of private campgrounds and resorts. The Forest Service countered complaints with the belief that private owners of such facilities would actually benefit from free public campgrounds in their vicinity; that a greater volume of tourists were brought into the area and, therefore, private businesses would realize additional patronage. Forest officials maintained that, generally, people who camped at free, public facilities were unable or unwilling to pay for camping. Moreover, the Forest Service's aim was to concentrate camping at sites where water and sanitation were provided and where the risk of forest fire could be minimized. Similar arguments against Forest Service campground construction would resurface when new developments were proposed in the 1960s.

|

| One of Ranger Quackenbush's trail shelters—this one at Summit Valley in 1955. Courtesy of the Charlie Brown family |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

5/six-rivers/history/sec2.htm Last Updated: 14-Dec-2009 |