|

A History of the Six Rivers National Forest... Commemorating the First 50 Years |

|

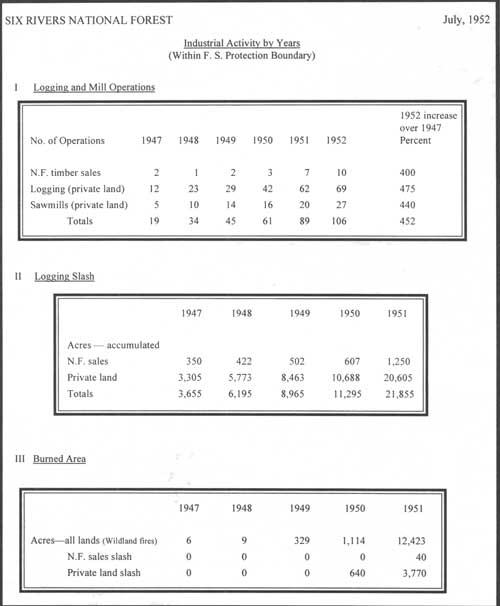

The First Three Years...

The Challenge, the Promise, and the Vexations

|

...the Six Rivers' potential for growing and harvesting timber was the

envy of every major timber-producing forest in Region 5.

|

Effective forestry was the broad, primary goal of the neonate forest, and the Six Rivers' potential for growing and harvesting timber was the envy of every major timber-producing forest in Region 5. The Six Rivers' commercial forest land area was composed of old-growth stands, generally 250 years old or older. About 20 percent of those "overmature" stands also had an understory of poles or young sawtimber (USDA, FS 1979: 8). The estimated board feet on the Six Rivers was 16,753,000,000 with about 80 percent being Douglas fir (HT 3-13-49).

There were major challenges to be met, however, before even a fraction of this potential could materialize. Prime was the job of getting the new national forest on a functional administrative footing. Regional Office inspectors who visited the Six Rivers just two years after its formal creation recounted what it was like:

Placing an area under a new form of administration in the manner of the Six Rivers was an onerous task. Starting with an empty office, supervisor and staff new to the area, there was the job of assembling files, atlases, statistics and other records from three forests. The resulting aggregation of knowledge was far less satisfactory than might be expected. Fortunately the rangers have seen fairly long service in their districts and only in their minds was much of the background needed for effective administration and the loss of knowledge that remains on the forests of origin. Administration is still slowed by gaps in the records and voids in the basic facts required for decisions and plans [Cronemiller and Kern 1949:1-2].

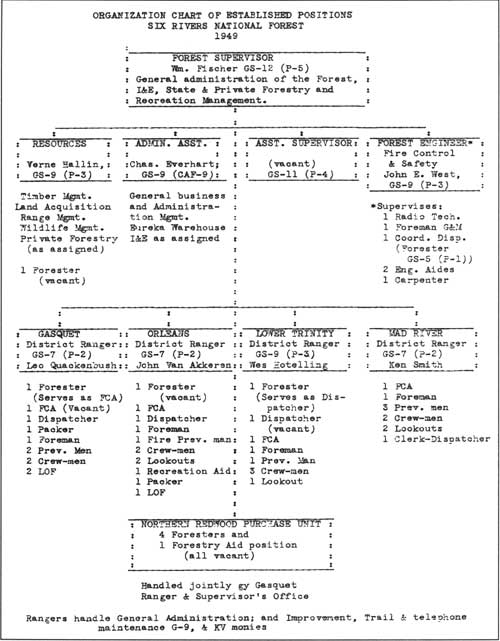

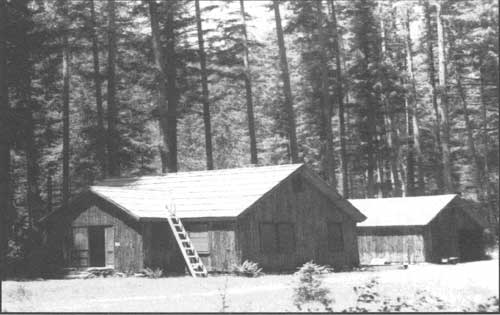

There were myriad details to attend to before the new national forest could function smoothly as a unit. For example, being composed of parts of three national forests in two regions, along with a completely new supervisor's office, the Six Rivers lacked anything resembling an integrated communication system. To begin to remedy the situation, in June 1947, the communications engineer from the Trinity National Forest was detailed to the Six Rivers to install a short wave radio network. Twenty-five watt transmitters were installed at the offices in Eureka, at Crescent City, Gasquet, Salyer, Mad River, and Orleans (WTJ 6-26-47). The Six Rivers' 1947 communication system consisted of 447 miles of ground telephone line plus 44 miles of metallic circuit pole line (USDA, FS 1947: n.p). The Six Rivers also inherited four ranger stations, eight guard stations [33], 20 lookout stations, and one work camp. In total, there were 119 administration and protection buildings to use and maintain. The Northern Redwood Purchase Unit also had its building and work camp and the California Forest and Range Experiment Station operated its sub-station at the Yurok Experimental Forest (USDA, FS 1947: n.p.).

|

|

Locations for the administrative buildings inherited by the Six

Rivers National Forest often made little sense when the new forest was

considered as an entity of its own. Some of the Six Rivers most distinctive administrative buildings were constructed during the depression-era. The CCC-constructed buildings comprising Big Flat Guard Station on the Gasquet Ranger District were clad with cedar slabs that had not been debarked. These photos of the station barracks and barn were taken in 1955. Courtesy of the Charlie Brown family |

In addition to communications and administrative facilities, the transportation system inherited from its parent forests made little sense for the new, westward-looking Six Rivers. The 1947 "Situation Report" listed 1,247 miles of approved roads: a total of 567 miles were built, with only 281 miles of that deemed to be in "satisfactory" condition. There were 43 bridges, few of which were capable of handling commercial log loads: 56 percent were log-constructed, 29 percent timber-constructed, and 15 percent made primarily of steel. There were 1,483 miles of approved trails, with 1,377 miles having been built by latter 1947. It was estimated that about half of the existing trails were not maintained to a satisfactory standard because of low use and inadequate funds for that purpose. [34]

The local newspaper's "Log and Saw" column reported regularly on the need for roads and bridges adequate for logging trucks. This shortcoming was a significant roadblock to full development of the area's timber resources. Certain bottlenecks were frequently mentioned, such as the Klamath Bridge at Weitchpec, then designed to carry only 12 tons; the narrowness and curveyness of US 299, especially between Willow Creek and Blue Lake; and the 23-ton limit on the Redway Bridge on US 101. All of these links in the transportation system were slated for improvements in the coming two years but, as noted by county surveyor Frank Kelly, the importance and weight requirements of logging meant that other key roads and bridges had to be rebuilt, "regardless of the frequency of use, in order that they may carry the heaviest loads safely" (HT 7-13-47).

|

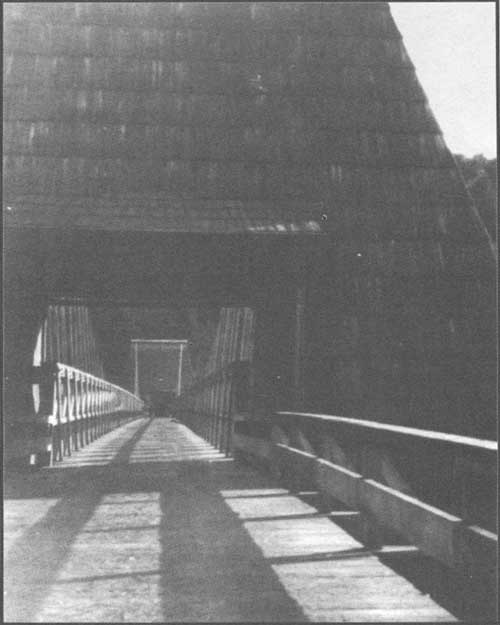

| This undated photo of the Orleans Bridge across the Klamath illustrates that, even some of the more well-built bridges on lands that served the Six Rivers National Forest, were inadequate for hauling commercial-sized loads of logs. The Klamath Highway was not completed until 1923; its dedication was a huge event, attracting a roster of dignitaries that included Congressman John E. Raker and Regional Forester Paul Redington (Bower 1978 vol. III: 53). US Forest Service photo |

Another gnarly difficulty that had to be worked through was the difference between Forest Service log scaling and commercial scaling. Commercial scalers dropped all fractions of inches in diameter measurements, while the Forest Service rounded fractions to the nearest inch. Moreover, peculiar to the north coast area, the Humboldt Log Rule was used for scaling redwood. The Humboldt Rule used Spaulding volume tables less 30 percent deduction due to the high amount of defect in redwood. The Forest Service did not use Humboldt Log Rule but, instead, used the Scribner Decimal C tag rule system and made deductions for defect based on local observation (Hallin 5-20-97: pers. comm.).

With all of the hurdles, roadblocks and frustrations, the forest supervisor and rangers were keenly mindful that, as the first administrators of a brand-new national forest, they were making history. Fire Control Assistant Lloyd Hayes suggested that the rangers take the time, at the close of their inaugural year, to narratively record events of the past 12 months. Supervisor Fischer endorsed the idea and asked them to write-up the highlights by major function: general administration, fire control, timber management, range, lands and recreation, and engineering:

. . . record personal reactions and feelings at the news of the creation of the Forest, wonderment at how it would work, the name, first contact with individuals in locating boundaries, etc. Be sure you have the bad as well as the good things of the first year [Fischer 1-9-48].

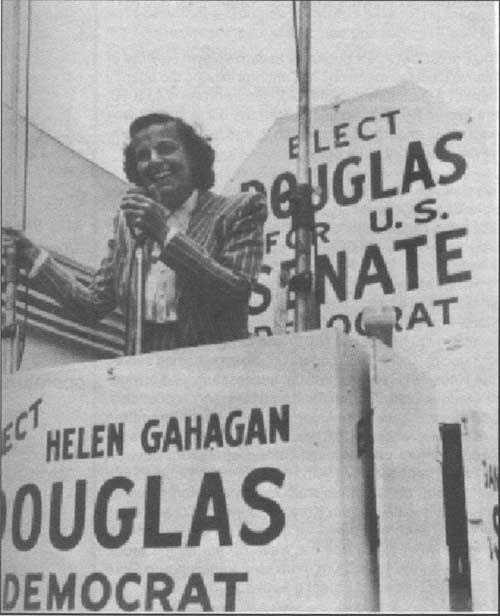

So far, three of these histories have been located: Lower Trinity, Mad River, and Gasquet. Long-time Lower Trinity District Ranger Wesley Hotelling's retrospective of his first year as part of the Six Rivers National Forest was the most lengthy. [35] Hotelling's district history implied that the Douglas Bill influenced the decision to create the Six Rivers and, moreover, that a significant segment of the public suspected that the move to create the new forest was a harbinger of a larger and more ominous threat: establishment of Douglas' Roosevelt Memorial Redwood Forest which, detractors warned, would deprive counties of direct tax and indirect payroll revenues. Because of the many first-hand insights it provides, Hotelling's colorfully-written history of the Lower Trinity's first year as part of the Six Rivers is quoted in its entirety.

|

| Orleans' first ranger headquarters with William Hotelling and Albert Wilder in 1910. This station was built in 1908. US Forest Service photo |

The most interesting phase of 'something new' is public reaction. People must have their say and rightly so; if they do not feel qualified to publicly denounce new ideas, plans, etc. they shout their criticism to their neighbor, the public official. The query 'Why establish another National Forest? - What's wrong with the present set-up? - Where does the economy come?' Many conclude 'just more regimentation.'

Following closely on the heels of the Helen Gahagan Douglas bill, the first wave of 'brass' made their appearance in the Coastal area. Their contacts, their statements somewhat confidential to key men spread like wild fire. These leading citizens rebelled and branded the plan as Communistic, inspired by labor groups. Word passed to groups, Stockmen Associations, Civic Organizations and to the Press, with full determination to stop the movement as a means of protection to 'Free Enterprise' - a system enjoyed by the residents of the Coastal area since the advent of the white man. Certain influential Governmental Agencies did not make matters any easier, particularly among stockmen who by this time appealed to the people for a united front [indeed, grazing was predicted by supporters of the Douglas Bill to be adversely affected by the bill, in contrast to other forest uses]. There were nods of approval by Gov't. men when public statements such as 'it's just another means of getting their toe into the door' were made. Summed up, it was nothing more than initial ground breaking for the Roosevelt Memorial Forest that spelled doom to 'Free Enterprise' and removal of taxable lands from the assessment roll.

The second wave of brass came in at the peak of the fight and adverse publicity was running rampant in the local papers. Key men and political bosses had made up their mind and warned that the fight was just commencing. A Local Druggist decided that something had to be done besides talk. He publicly declared a desire to be of service. This offer was accepted and it was the very Druggist who was responsible for the preparation of a resolution for passage by the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors against the Douglas Bill and indirectly against establishment of a Forest Headquarters in Humboldt County. Incidentally the druggist who prepared the resolution was and still is a key man and a darn good one.

It is true that all this took place prior to 1947. To be exact, the summer and fall of 1946. It is felt that these incidents all lead up to 1947. The Lower Trinity District played an important part even though for no other purpose than keeping finger tips on the pulse of public opinion. Many individual contacts were made and findings were extremely interesting. The layman, during the interim, analyzed the problem to his satisfaction and concluded that after all there were many advantages — more regulated use of our resources just had to come....

Beginning with 1947, January through May 1st, the Lower Trinity District tottered in the balance. The Trinity reminded us that we no longer were a part of their unit but that they would tolerate the personnel to the extent of accepting our 26's. During this period records were segregated and transferred to Big Bar District. Ties were still very close with the Trinity Headquarters, at least with the Clerical force. ...Key personnel transferred with the district and we were content to give the Trinity the New River protection force along with our pack string.

We gave up with considerable reluctance, our special use business, that had been developing in New River over the years, particularly the effort put into convincing the old miners of accepting a special use permit in lieu of a mining claim. [36] We never crowded these fellows. They took their time and in the end came to our side. Two hydroelectric power permits in that area, represented a lot of hard work and pride of the district.

In loss of the New River unit went not only a large area of the district (about 1/2 the total acreage) but also, a sizable part of the New River deer migration route, also a pride of the district and on which we had compiled a 12 year record of deer movement, deer kill and the pleasure of gathering annual data....

In grazing we lost two allotments and gained one A slight increase in animal months and receipts are up a little.

Mining was not a serious loss but we did have plans for development of the Pulp business in conjunction with by products of Copper, a combination of great possibilities for this area. Still is.

In timber, we have gained a lot in the Grouse Creek basin - South Fork Mt. districts, even though at some disadvantage to administer with our present transportation system. First inquiries from operators on possibilities in this basis came in 1947....

As expected, we, like all other districts, had to undergo many adjustments, in operation and fiscal procedures. With the same manuals as used on other forests, just the same there are those minor differences which all add up to something different . . . .

Fire control suffered somewhat by the complete absence of training, at least in fundamentals. . . . We want to emphasize the need for more and more fire prevention. As we see it, the surface is barely touched. Here again, resource work absorbs all available time. We are strong believers in the theory that good resource management is the very best Fire Prevention. The point is, we have not yet reached the point in perfection of resource management that it reflects in fire prevention, at least not materially. . . .

Lumbering is developing rapidly on the district. To date it has been confined to private timber, but has now reached a point where National Forest timber is going to be in increasing demand. The district, despite the fact that lumbering interest has been crowding on all the corners, did complete Timber Management Plans involving two working circles. Some of the details were completed in January and February but on the whole the job was pretty much done during 1947.

With approval of plans, we will be in a position to go into timber sale, and timber management on a businesslike basis.

This 1965 aerial photograph shows the Horse Mountain copper mine as it was being dismantled. US Forest Service photo We feel and urge that Government funds be made available for surveys and construction of major access roads on the planned system. The first leg of the system at least, should be a Government responsibility.

Playing for time in which to compile data and otherwise complete Timber Management Plans, the district adopted the practice of referring timber buyers to owners of private tracts. This resulted in the sale of timber by the small individual owners of tracts located near or adjacent to Highway #299. The destructive methods employed are, of course, very apparent. To the extent that some are holding out for better or improved forestry practice. Outstanding in this respect was Mrs. Clair Shore of Willow Creek, an ardent believer in conservation.

Present trends are unquestionably toward peeler stock at any price. Length of haul no longer a serious cost factor. Disposition locally of the lower grade logs at cost or at a figure less than cost appears well within the realm of good business. Salvage of a fairly high percentage of peeler stock is, very definitely the principal factor.

Range management plans are practically completed for the 8 range allotments. A forward step in compliance was made in 1947 with fairly good results. The principal goal for the present is proper seasonal use and check of unauthorized use, particularly on the Trinity Summit Allotment. More time for inspections and home ranch dependency surveys are necessary for more equitable distribution of grazing privileges. This is very important.

Demand for recreation areas, facilities and special use sites are developing rapidly. We were able to establish the Humboldt Country Council of Camp Fire Girls, an organizational camp, on the district this year. Preliminary work done on other sites for youth groups.

Recreation planning has been dragging as a whole this past year. Complete to date is a District wide map, constructed on a 4-inch [to the mile] scale, on which is shown all Government tracts of potential recreation value....

One U-3-b tract was submitted and approval granted. Forest Picnic Area.

The need for more camp grounds with adequate facilities are of paramount importance. Equally important are funds for proper maintenance and policing once constructed.

[Engineering] Surveys is the one outstanding problem in good land management. Present surveys (1880) are inadequate and an ever present problem. The district is sadly in need of an approved trails system (submitted 1947) as a starting point or basis of planning maintenance. The trend should be for less mileage and fairly low standards. Trails just do not serve as they did in years gone by. Preparation of and adoption of a road plan was a stride forward and can be chalked up for a 1947 accomplishment.

Public opinion at the close of 1947 is practically reversed to that of the fall of 1946. There is in general, good feeling toward the Six Rivers National Forest, the headquarters personnel and, most outstanding is the confidence that has come about in these few months... [Hotelling 2-11-48].

In an even later retrospective, Hotelling wrote:

|

"We were perplexed by many things. One was

uncertain land surveys and the location of timber tracts with

reference to these surveys."

|

The 1940 era brought many changes to our administration . . . . There was on the horizon timber cutting. With World War II coming to an end there appeared to be a demand for timber. We were perplexed by many things. One was uncertain land surveys and the location of timber tracts with reference to these surveys. We foresaw many problems that we had to face and they were coming soon.... We started our lumbering in a small way, limited because we were not experienced, though we believed we should have been assigned to Region 6 to observe timber cutting in the National Forest. It would have given us some knowledge of how to establish policy and cutting patterns here on the [Lower] Trinity. Without any encouragement or help from the Forest Service it was concluded that we were on our own. During these preliminaries the timber load kept increasing and this did cause the regional office to think in terms of assistants, at least technical [Hotelling 1978: 94-95].

The problem with land lines precipitated a greater than average workload and headache factor in timber trespass, at least for Lower Trinity (Hotelling 1978: 100). Wes Hotelling was an avid local historian. After his retirement, he continued to contact old-timers in the area and ply them for information that, in most cases, was otherwise undocumented. He was a regular contributor the The Kourier, published in Willow Creek, and many of his stories for the paper were intertwined with early Forest Service history. He also wrote a book, published in 1978, that chronicled his boyhood years living along the Klamath River and his long and varied Forest Service career: My Life With the Kar-ooks, Miners and Forestry.

The Mad River District Ranger, R. Kenneth Smith's, experience contrasted with that reported by Hotelling regarding the local public reaction to the transfer of administration. Ranger Smith noted that:

Transfer of the district from Trinity to Six Rivers National Forest did not create any particular stir among locals or users from outside. It had been expected that there would be more queries than there were as to the 'why' of it. The transfer seems appropriate for the timber resource especially, as the railroad and the higher standard roads are on the coast side, and the topography drains that way too.

|

"It would appear that purely educational efforts

are going to have to be reinforced by compulsion."

|

Written in a more matter-of-fact style than the conversational diaries of Rangers Hotelling and Quackenbush, Ranger Smith's diary showed that the district was gearing-up for the expected timber sale business. The district was divided into the Eel River and Mad River working circles and estimates of gross volumes were assigned to each. The ranger made an interesting comment regarding the new Forest Practice Act that had recently gone into effect. Noting that the new rules stipulated that care be taken to protect young growth up to 20 inches in diameter as well as slash disposal for timber harvests on private lands, his observation was that:

Actual practice on private land is generally to take out what will pay its way, exercise little care with young growth, and do little slash disposal. It would appear that purely educational efforts are going to have to be reinforced by compulsion.

It appears that the Mad River ranger's forte was range management. In his recounting of his district's first year, he noted that 1,700 cattle grazed under permit on Mad River District and that live beef prices for 1947 were 20 cents per pound. Klamath weed control was considered the primary work and 2,4-D weed killers were both "sprayed and dusted in areas too remote to pack in borax.... Klamath weed eating beetles were released through the Dept. of Agric., near Blocksburg..." Regarding recreation on the district, the ranger noted that such use increased as a result of lifting wartime travel restrictions, but that use was still light. An estimated 1,000 visitors used the improved campgrounds; there were also an estimated 900 hunters, taking 300 bucks and 30 bear, and there were 800 anglers. Reporting on the first fish plantings on the district since the war, 48,000 rainbow were planted in Mad River and 23,000 in the Van Duzen; all from the Prairie Creek Hatchery. [37] The ranger reported "considerable interest" in summer home sites on the district by Humboldt County residents; "thus far private lands have partly satisfied the demand" (Smith 1947: passim).

From another district ranger's perspective during the time of the transfer of land to the Six Rivers, Leo Quackenbush of Gasquet Ranger District wrote the following personal observations late in 1947:

Beginning in February of 1947, the Gasquet Ranger District of the Siskiyou N. F., slowly began to move from the ardent clutches of the Siskiyou N. F. in Region 6, into the open arms of the shiny, new, Six Rivers N. F. in Region 5. By early spring this move was complete and on June 3, 1947, President Truman signed the proclamation, officially establishing the Six Rivers N. F., which is comprised of the Gasquet District, the Orleans District of the Klamath Forest, the Lower Trinity District and the Mad River District of the Trinity Forest. For good measure the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit hung out a Six Rivers shingle also.

Immediately after the transfer the post man started groaning under the Gasquet mail load. At the Ranger Station, the letter openers were sharpened up and the new forms and instructions stocked up. Some of this stuff had a familiar look, but some of it was written in a 'foreign tongue,' with the result the light plant worked overtime while the District Ranger, Leo D. Quackenbush, better known as 'Quack,' toiled to all hours learning the meaning of the R-5 hieroglyphics. By the opening of Fire Season 'Quack' was bilingual in more ways than one.

. . . Only one timber sale was in operation on the District this year.... A timber management policy statement for the Middle Fork and South Fork Working Circles was started in August. This is expected to be completed in the early part of 1948. It is running into a job due to lack of timber survey data covering this area....

In cooperation with the State Game Commission, a plan was prepared whereby a sizable herd of elk, some 40 head, were to be planted in the upper reaches of the South Fork of the Smith River. This area, in the early days, was a natural elk habitat. With this in mind it is thought that elk should thrive in that area. The elk were to be obtained at the Prairie Creek Refuge and hauled by the State. Late in October the first shipment arrived, thirteen head. Ranger Quackenbush, [Morrison] James and [Robert] Steven, accompanied the load with a stake-body truck. It was necessary to tow the elk truck through several mud holes. The elk were released at the junction of the Bear Basin L.O. and Doe Flat road. Numerous pictures were taken of the operation. One bull elk lost its footing in the truck and was badly trampled, as a result, it died. [38]

Early in November, 5 more elk were released in the same vicinity. Due to shortage of personnel on the part of the State, the 17 head was all that were brought in this year....

As the year draws to a close, the District Personnel consists of Ranger Quackenbush, Packer Steven, and FCA [Fire Control Assistant] James. [39] We look back over the past and realize that the year 1947 has been a good one. The war is almost forgotten, the expected high cost of living is self-evident, and we are all a mite concerned with making ends meet, but it is better than sweating out Military Campaigns and we are thankful....

The idea of keeping a District Diary or History is new. We think it is a good one and hope that our successors will carry on where we leave off... [Quackenbush et al. 1947: 1-6].

"The Region of The Last Stand..."

By the time the Six Rivers was created, the threat of "timber famine," as a motivator to put forested lands under Forest Service stewardship, took a back seat to the idea that the Forest Service could help develop and sustain forest product-dependent communities. By opening new "logging chances" to the timber industry, roads for fire protection and recreation could be funded reaching ever-deeper logging opportunities. Logging on national forest land was to be designed for sustained yield, on the scale of working circles, thus avoiding the characteristic boom and bust of rural, timber-dependent communities under the "log it and leave it" pattern. Perhaps enough time had passed and enough scars of former logging methods had, at least superficially, healed that the cry of "timber famine" no longer had the same punch. Moreover, the industry had responded to laws and policies that curbed some of its former excesses. The call to arms that had motivated the previous generation did not exactly fall on deaf ears, but it did not have the resonance it once had.

|

"The devastation must be stayed if we are to

survive as a nation."

|

As late as the 1930s—and partly responsible for the thrust to create the redwood purchase units—former and first Chief of the Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, made a familiar pitch. In the foreword to what became Senate Document 216, Major George P. Ahern's Deforested America, Statement of the Present Forest Situation in the United States, Pinchot complained that deforestation had slipped from the fore of the public's consciousness, and much to its peril:

For the last decade and more the essential fact about the forest situation in America has been winked at or overlooked in most public discussions of the subject. The fact is that our forests are disappearing at a rate that involves most serious danger to the future prosperity of our country, and that little or nothing that counts is being done about it. Of 822,000,000 acres of virgin forest only about one-eighth remains. Half of that remainder, roughly speaking, is held by the Government and is safe from devastation. The rest is being cut and burned with terrible speed....

Major Ahern, a self-taught forester for whom Pinchot had utmost professional respect continued his introduction, saying:

The most serious phase of this appalling situation is that no alarm is shown at the Forest Service headquarters or by lumbermen. Although the principal facts here presented are acknowledged by the foresters at headquarters... the public has been kept in ignorance of the situation.... The devastation must be stayed if we are to survive as a nation [U.S. Congress 1929: v & viii].

Ahern also quoted forestry researcher T. T. Munger regarding the status of forestry in the Pacific Northwest by the close of the 1920s—a place referred to as "the region of the last stand:"

The industry has been following the same road for generations, the road of least resistance; perhaps they are going so fast down the smooth, straight road under the pressure to liquidate bonded indebtedness that they can not make the radical turn into the new road to timber farming. The road to timber farming turns off sharply from the well-tracked conventional route. Few have traveled it in Oregon. Timber mining looks like a better-paying business than timber farming.

|

Ahern pointed an accusing finger toward the Forest

Service for the lack of public outrage over deforestation.

|

Ahern pointed an accusing finger toward the Forest Service for the lack of public outrage over deforestation, noting that:

The rapidly increasing forest devastation so disturbed the Forest Service that some four years ago it quietly banned the use of the word 'devastated' and substituted therefor the milder word 'denuded....' [T]his appalling forest situation [has] been known to the Forest Service for many years. . . so menacing to our national prosperity, even involving our national defense.... The foresters [in the field], for more than 20 years. . . have duly reported the facts to headquarters at Washington, but there they lie. The foresters at headquarters... have fallen down on the job in failing to get the real facts to the people, not through the medium of dry Government bulletins, but on the front page of metropolitan dailies.

|

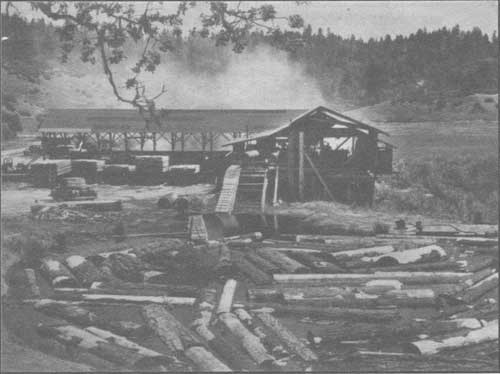

| The Hoaglin Valley Lumber Company sawmill in Kettenpom Valley was one of the many small mills that sprang-up in Humboldt and Del Norte counties during the post World War II decade. US Forest Service photo |

From the outset, the Six Rivers' overall mission was clear, and its officials expended a great deal of energy in getting the word of forestry and of sustained yield management into the ears of the local publics: they were committed to making a stand. Creation of the Six Rivers National Forest played a key role in the growth and the nature of change in the California north coast area's timber industry. In 1930, the forest products industry was responsible for the livelihood of 50 percent of Humboldt County's residents. In 1941, there were only 24 sawmills in Humboldt County, but by 1950, there were about 160 active mills representing a broad investment spectrum (Vaux 1955: 5). [40] Though there had been a steady, incremental increase in the number of sawmills during that range of years, the number leaped from 108 to 160 between 1947 and 1948, primarily representing an increase in the number of smaller mills. The county's lumber production in 1948 was 815,810,000 board feet, excluding the product of 14 shingle and shake mills. Its lumber industry directly employed 3,920 workers in 1940; a decade later, that figure was about 7,000 (USDA 1947: rev. pg. re. lumbering 1-1-50). Using a factor of one in five, about 48 percent of Humboldt County's working population was supported by the lumber industry according to the 1939-1940 census.

Below are some of the timber figures forest officials were looking at in 1947:

| County | Est. Board Ft./Total |

In N.F. Ownership | Yrly Avg. Lumber Production Since 1920 |

| Humboldt | 46 billion | 7 billion | 366 million |

| Del Norte | 11.5 billion | 3.5 billion | 16 million |

Officials in 1947 predicted that, for Humboldt County, the old growth stands would support a future average harvest of 500 million board feet; the upswing was already evident in the war year, 1945, when production reached 455 million. For Del Norte County, production was 24 million board feet, but officials predicted a future annual production figure of 85 million, given accessibility improvements that were on the horizon. At that rate, the old growth stands were predicted to last about 60 years in both counties and income from the industry was expected to plummet by 50 percent when the old growth was exhausted (USDA 1947: A-1, 2, 3).

The Forest Service had taken up the gauntlet of using its influence to substantially improve logging practices in old growth stands in order to leave the logged-out areas in good condition for second growth production.

|

The new forest's role in California's north coast

involved very high stakes.

|

A major factor in the spectacular growth of the north coast timber industry during the 1940s was the Douglas fir market. Earlier, Douglas fir had been virtually ignored as a commercial tree even though it accounted for 66 percent of the county's 1948 timber inventory. Totaling only 11 per cent of the county's cut before 1940, it accounted for more than 60 per cent of the cut after 1948. Different manufacturing techniques spawned new competitors on a playing field that had been dominated by redwood producers, and medium to small-sized mills became more important. In contrast to redwood mill owners who owned about five times as much old-growth timberland as the average Douglas fir mill owner, fir operators had to depend on purchasing logs or stumpage from other land owners, notably the Forest Service (Vaux 1955: 9, 10). Moreover, until the 1950s, Douglas fir from everywhere on the Six Rivers—with the possible exception of Gasquet—was considered almost a weed; it was "brashy". . . hard to work and splintery, whereas the Douglas fir from Oregon and Washington were finer grained and easier to work (Hallin 5-20-97: pers. comm.).

The new forest's role in California's north coast involved very high stakes. And in order to steer a true course toward forest sustainability—a course between resource protection and development—it was clear that the Six Rivers needed a reliable policy compass, oriented with a sound philosophy.

|

| This photograph, probably taken during the 1950s, shows a truck being loaded with old growth Douglas fir. A tractor is working, at the far left, by the log deck. US Forest Service photo |

The Six Rivers' First Timber Management Policy

In January 1948, as part of the "Brain Book," Supervisor Fischer provided historical perspective and guidance about the new forest's timber management program. [41] He wrote. . .

We on the Six Rivers National Forest have as one of our major jobs and objectives the management of lands for timber production. Heretofor [sic.] we have been holding these lands in a more or less custodial manner waiting for the time when economics and demand would make our product marketable. That time has come. At least we are on the threshold of doing a substantial timber business each year. We will become an asset rather than a liability to the American tax payer.

Fischer was concerned about the dearth of bidders for the forest's first few timber sales. Prospective buyers had openly expressed their fears about bureaucratic red tape and what they perceived as arbitrary requirements. Fischer underscored with his rangers and staff that:

In the management of these Federal lands for crops, whether they be forage or wood or services, we have several basic responsibilities.... Basically, I believe we have at least three of equal importance:

1. To see that crops are harvested on a sustaining basis without deterioration of the capacity to yield.

2. To our employers, the people, that their interests are protected and that they receive fair and just return for the products or the services of these lands.

3. To the contractor or the permittee to see that his interests are protected, that he has a fair opportunity to gain his objectives....

We have, in general, done a pretty good job of the first two. We have always recognized them. Too often we lose sight of the last in our zest to accomplish the others [USDA, FS Handbook 1-28-48: Resources].

Intended to be the forest's policy compass, by June 1948, the Six Rivers had completed its "Preliminary Timber Management Policy Statement." Prepared by George Ferrare, Assistant Forest Supervisor, the document stated that the major purpose of creating the new forest was "the sustained production of forest resources for the benefit of people." This opening statement summarized that shaping a new administrative unit in the form of the Six Rivers National Forest would promote sustained production of forest resources in a more beneficial way than if the area remained under the administration of its three parent forests.

The economic situation painted by Ferrare detailed the thinking that went into the impulse to create the Six Rivers. He noted that the coastal region of northwestern California contained one of the last remaining extensive virgin timber stands in the West and that about 70 percent of the territory served by the north coast area's transportation system was forested land capable of producing commercial timber. From 1920 until 1945, the average annual production of softwood lumber from the area that became the Six Rivers was estimated at only 384,000 board feet; in 1945, that figure jumped to 480,000. Since that year, production was in an upward spiral, particularly due to high demand for veneer and lumber, and production was expected to approach one billion board feet by the end of 1948. The embryonic Douglas fir industry was developing rapidly and there was an anticipated surge in utilization of hardwoods, particularly in furniture manufacturing. [42] Additionally, the market for Douglas fir stumpage commanded less than $1.50 per thousand board feet prior to 1944 but, by 1948, averaged $3.25 per thousand. The plywood industry did not gain a toehold in Humboldt County until 1947, but by 1954, there were four plants with an annual capacity of over 240 million square feet on a 3/8-inch basis. Additionally, five veneer plants accounted for about 360 million surface feet of green veneer annually. Douglas fir was the main source wood for both plywood and veneer (Vaux 1955: 11). Up to 1947, most of the logging in the area tributary to the northwest coast of California had been on private land, with only about 16,000,000 board feet being cut on what became the Six Rivers on 1,675 acres. Ferrare stated that private logging practices in old-growth stands generally employed relatively harsh methods followed by broadcast burning, leaving about 80 percent of the private cutover land in poor productive condition.

The objectives of Six Rivers National Forest timber management were a reflection of the Regional Timber Management Handbook which was essentially to bring existing and potential National Forest lands to their maximum timber production in as short a time as possible. By doing so, under sustained yield methods, it was believed that the national forest would contribute its fullest toward local dependent industries and communities. [43]

The primary transportation system for forest products on the Six Rivers led to the Eureka-Arcata area: the main manufacturing and shipping point by rail and sea. Lumber and logs were also trucked eastward to Redding for California markets, northeast to Grants Pass, Oregon for manufacture and rail shipment, and as improvements were made for Humboldt Bay and Crescent City harbors, westward for year-long shipment by sea.

Ferrare's timber management policy for the Six Rivers hinged on the premise that private, old-growth stands were predicted to last only between 40 and 60 years longer, that the absence of old-growth logging would precipitate a drop of about 50 percent in employment and income, and that this foreshadowed a "heavy blow to the local economy" considering that the industry supported about 48 percent of the local population. [44] The solution was instituting the practices that insured a sustained industry, including improved utilization and cutting practices. Ferrare took heart that some of the long-time lumber operators were beginning to plan production on a sustained basis, optimistically commenting that: "If this trend in private industry continues, coupled with a strengthened State Forest Practice Rules, the future of this area may be safeguarded against the serious economic and social problems associated with 'cut out and get out' exploitation....

By the end of the 1940s, the Six Rivers was experiencing strong competition for its stumpage, and available private timber within the administrative boundaries of the forest were the subject of "heavy timber speculation." Ferrare predicted hard times for smaller lumber industry concerns that were less and less able to successfully compete for more and more scarce private stumpage or for large blocks of offered government timber. Their limited capital and timberland ownership put them at a distinct disadvantage in light of the Forest Service's impetus to structure larger government timber sales. Larger sales tended to promote forest road system development and to assure adequate purchaser deposits for slash disposal and reforestation—all aimed at putting the Six Rivers on the path to sustained yield forestry. [45] Mills that had depended upon private timber were casting their gaze toward national forest timber to stabilize their futures. Importantly, however, Ferrare warned that the estimated annual harvest during the second cutting cycle would comprise only one-sixth of the total lumber production for the Six Rivers tributary area; a harvest insufficient to "materially cushion the economic effects of a heavy curtailment in lumbering on private lands at the end the 40- to 60-year period."

The policy statement included all the land on the Six Rivers, plus the portion of the Klamath National Forest that was included in the Orleans Working Circle, and minus the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit's Requa Working Circle. [46] Given these parameters, there were 994,161 acres of government and 169,296 acres of private land within the administrative boundary. Of this, there was an estimated 850,319 acres of "productive" land with reference to timber; 712,221 acres were Forest Service lands. The estimated total acreage of merchantable old-growth timber was 515,717; 433,436 acres of it was Forest Service land. There was an estimated volume of 22,277,936 mbf, with 18,576,011 mbf of it Forest Service volume. Old-growth trees constituted 90 percent of the total volume of the old-growth stands with a cull factor ranging from 25 to 35 percent. Growth rates after logging on productive land were estimated to average 300 board feet per acre for Douglas fir and redwood types and 200 board feet for mixed conifer and fir types. Since local yield tables were not yet available, the figures were estimated on the basis of local increment borings and observations and were considered conservative.

The recommended "cutting budget" on the Six Rivers for the first cycle was 174,500 mbf with the primary objective being removal of "high risk, decadent trees" in order to improve net growth of the residual stand and realize the value of the decadent stand. The second cutting cycle budget was 182,639 mbf on national forest land; after the first cut, the problem of regeneration was to be a major consideration. Ferrare pointed out that the "[t]imber sale business, which is practically starting from scratch at the beginning of this ten year period, will gradually expand and may approach 100-125,000 MBM annual cut in ten years. Consequently the actual annual cut for the first ten years is expected to fall considerably below the budgeted annual cut for the first cutting cycle. This anticipated sales situation would act as an additional safety factor to compensate for any possible over-estimation of timber volume and growth." Given the forest's generally favorable conditions for adequate natural regeneration, Ferrare did not foresee extensive planting programs for the Six Rivers. Up to the approved annual cut, the timber sale policy for the Six Rivers pivoted upon receiving applications to harvest specific areas from "established operators who qualify with respect to financial ability, experience in logging and manufacture, and in general efficiency of past mill and wood operations." To avoid high grading—that is, harvesting only the most profitable trees—timber sale planning required that all commercial species in a specific area be included in the proposed sale. The policy also directed foresters to consider the sustained yield capacity of adjacent Indian lands in planning for sustainability of mills within affected working circles.

|

The minimum scope and context of timber sale

planning was to be the

working circle and it was clear that sustained-yield timber production

was the engine that powered the structure and content of

alternatives.

|

Though shorted by today's yardstick, there was some consideration of resources other than timber offered in this, the Six Rivers' first timber management policy. For example, in locations where recreational use was a dominant or co-dominant value, cutting, logging, slash disposal, and road location were to be modified with the object of protecting these existing or proposed values. Moreover, watershed protection was a consideration, although Ferrare inaccurately stated that the forest's soils were "generally of such texture and structure as to make it stable and not subject to serious erosion." Vegetative cover along stream sides were to "be preserved as much as possible" and stream crossings of logging roads were to be minimized. Except for large open glades, grazing ranges were viewed as "temporary in nature, due to gradual encroachment of the timber species." Therefore permitted stock on the temporary ranges was to be gradually decreased. Selective harvest methods were viewed as having a positive affect on wildlife by improving their food sources. As for fish, the only words in the plan were that impediments to free migration of fish in streams as a result of timber operations were to be removed before withdrawal of logging equipment. The forest was divided into nine working circles in addition to the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit's Requa Working Circle: Middle Fork-Smith River, South Fork-Smith River, Orleans (Klamath and Orleans blocks), Blue Creek, Bluff Creek, Horse Linto, Lower Trinity (Willow and Grouse creek blocks), Eel River (Grizzly Mountain and Hoaglin blocks), and Mad River (Ruth and Pilot Creek blocks). The minimum scope and context of timber sale planning was to be the working circle and it was clear that sustained-yield timber production was the engine that powered the structure and content of alternatives.

|

The young Six Rivers National Forest was a fulcrum

point in California's timber industry...

|

Though there were a few glimmers of success, frustrations intensified among Six Rivers officials in their efforts to bring forestry to the north coast. While the impatience of Regional Office and other observers mounted, accomplishments toward the Six Rivers' primary objective were foiled by a seemingly unending procession of hurdles. Among them was the fact that there were "perhaps fewer proven principles in forestry [in California's north coast area] than for any other commercially timbered area in the United States." Using the example of fir forests that were predominantly mixed and in uneven aged stands, Region 6 to the north generally used a block clear cutting system while Region 5 preferred a selection system; private owners were "headed for a heavy selection cutting" system. On Gasquet Ranger District, it was noted there were old, even-aged stands that Region 6 would probably clear cut, but that the state of forestry in the area did not clearly "indicate the limitations" of clear cutting versus selection systems. For the redwood strip along the northwest fringe of the Six Rivers, the state of knowledge had even more gaps: "All of this indicates a more or less pioneering status in the development of silvicultural practices." The young Six Rivers National Forest was a fulcrum point in California's timber industry; having nearly half of the state's remaining virgin saw timber tributary to the Eureka railhead and given the rapid development of the area's re-manufacturing capacity, its role was pivotal (Cronemiller and Kern 1949: 1-3, 12).

By 1948, demand for timber sales on the Six Rivers was high and the forest was being criticized for being slow to make offerings available to prospective bidders. Fischer wrote in a cover letter for the forest's preliminary timber management plans and policy statements for its nine working circles, that: "The demand for timber sales continues very strong. We have been able to put off most of it under the plea of a lack of personnel. Operators are beginning to think we don't want to sell. The counties, too, are exerting pressure, and are beginning to wonder if we are just trying to hold out. You will note that we made special efforts to be conservative." The allowable annual cut estimate for 1949 was 109,600,000 board feet, including the Requa working circle (Fischer to RF 7-30-48). To the dismay and disappointment of Six Rivers Forest officials, none of the nine working circle policy statements passed muster at the Regional Office (Cronemiller and Kern 1949:19).

Huge frustrations were reported in administering timber sales on the Six Rivers during its first years of operation. Part of the problem could be traced to the marginality of the north coast lumber industry; a situation rooted in the facts that: 1. The fir and pine areas of the forest were not readily accessible and, therefore would be alternately economic and uneconomic with market fluctuations. 2. The fir was often exceedingly defective. 3. The "market is fickle," making "inferior" species, like fir, important in boom years and flatly uneconomic in off years, and 4. Redwood operations in the area were "geared to big stuff," making handling of smaller material uneconomical.

|

"Any time or effort spent in harvesting young

stands merely slows up progress in the more critical old

growth areas."

|

On the basis of this closer look, Six Rivers timber was, ironically, generally considered "marginal" and the resultant job of timber sale administration was, as a result, unusually vexing. For example, operators who failed to show a profit were, reportedly, "usually difficult to deal with." The high number of operators in the area, many of whom controlled little stumpage, resulted in a steady stream of requests for additional sales "requiring time-consuming preliminary appraisals." Paradoxically, responding to the inquiries and requests for additional sales seemed to have the effect of encouraging marginal operators (Cronemiller and Kern 1949:18-19).

In 1950, Supervisor Fischer stated that the forest's objective in timber management was "to convert the timber stands to a healthy growing condition as rapidly as possible and to bring all working circles to their full allowable operative capacity as rapidly as is economically wise and feasible." Fischer characterized the timber resources of the forest as "virtually untouched" with an estimated volume of old-growth commercial timber at 12,596 million board feet and an additional 750 million board feet on the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit. [47] Private lands within the forest boundary were estimated to contain 2,767 million board feet of commercial old-growth timber. The allowable annual net yield from the forest was conservatively calculated at 142 million board feet on a sustained yield basis, exclusive of yields from NRPU lands. [48] Fischer cited roads as the primary ingredient needed to develop the area's timber resource, underlining that "[t]he usefulness of the National Forest timber depends largely on the continuance of an adequate access road program. . . . Such expenditures [by the Federal government] are self-liquidating, returning the costs to the treasury through increased stumpage prices." Fischer, noting that the forest's stands were predominantly old-growth, characterized the key silvicultural challenge of the Six Rivers as "swing[ing] the growth-loss balance from zero, or a net loss, to a net gain in volume. Obviously then, the old-growth stands, on which net growth is at a minimum, need the first attention.... It is the program of the forest, therefore, to concentrate attention in harvesting... in the older components of the old-growth stands. Any time or effort spent in harvesting young stands merely slows up progress in the more critical old growth areas" (Fischer 1950: 7-10).

Hampering the timber harvest goals, as of 1950, the Six Rivers had 562.6 miles of existing system roads, with less than half of that mileage constructed to a satisfactory standard. To integrate forest transportation developments and to reach an acceptable cost-to-benefit ratio, the Six Rivers developed an "all purpose transportation plan." Supervisor Fischer stated that no new roads or trails were to be constructed on the Six Rivers without the proposal meeting plan requirements. He further commented that the plan was designed to develop road or trail access to inaccessible quarters of the Six Rivers primarily for the purposes of protection and for timber utilization (Fischer 1950: 23).

Making strides, as of 1952, the Six Rivers had about 1,535 miles in its planned forest road system of which 696 miles had been built. J. J. Byrne had remarked in his 1952 inspection report that: "This is one Forest where a large amount of federal [road] construction is necessary in order to open up difficult chances to timber." He urged the forest engineer to work closely with county, state, and federal road entities to upgrade or create transportation linkages to areas rich in timber resources (Byrne 10-27-52: 5).

|

The "main problem... is to get 'shoestring'

operators to build roads to satisfactory standard."

|

Nationally, larger Forest Service timber sales were also being promoted, with one of the effects being greater allowances for road developments connected with the sale. It was believed that larger sales would be more cost-effective and more lucrative and would chip away at the refusal of contract loggers to do more than the minimum road work necessary to fetch the logs. The Six Rivers did, however, persist in offering some smaller timber sales. Defending his forest's stance, Supervisor Fischer stated his belief that, although the small timber sale size had "affected road construction and maintenance allowances in appraisals a little," that regardless of the size of the sale, allowances for proper construction and maintenance should be "up where they belong." He commented that although larger sales will help, with large or small sales, "the biggest problem is the constant resistance of contract loggers to do any more than is absolutely necessary to do the logging." In a similar vein, Fischer also remarked on mineral access roads, that the "main problem... is to get 'shoestring' operators to build roads to satisfactory standard." He reported that the forest does not lessen its standards for mineral access roads, but it was "[s]ometimes very difficult to justify any but the lowest standards from standpoint of mineral alone."

". . . It is Timely for a Shift in Emphasis in

Administration. The Organizing Stage Should be Considered as Completed."

The Regional Office looked upon the Six Rivers with great interest and was intent on keeping a close eye on its newest progeny. One of the ways it monitored progress was through frequent inspections. These were typically conducted by experienced Regional Office people or individuals the Regional Office identified for the job; people who had the requisite breadth and depth of experience with the Forest Service to assess operations, pinpoint problem areas, and recommend changes that would increase efficiency and productivity. Inspectors sent from the Regional Office reported their findings directly to the Regional Forester. The overall purpose of the inspection program was to insure that policies and procedures made at higher levels in the organization—in line with presidential and legislative actions—were being executed at lower levels. Further, that execution was having the desired effect; that trends were heading in the intended directions.

There were two, basic kinds of inspections: functional and "general integrating." Functional inspections looked at individual program areas, such as fire, administrative management, or timber while general integrating inspections—or GIIs—examined how well all the component functions worked together to accomplish the forest's program of work. [49] As a historic, archival resource, reports from functional and general integrating inspections have tended to survive better than many classes of documents related to forest level operations, perhaps owing to the sense that inspections were taken seriously by both the inspector and inspected, and that multiple copies were made and maintained at various levels in the organization's structure. Whatever the reasons for their survival, there are several inspection reports and responses related to the early years of the Six Rivers that provide official snapshots of where the forest stood in relation to Regional expectations.

The first GII of the Six Rivers was conducted in 1949 by F. P. Cronemiller and J. C. Kern. It was their job to accurately assess and report to the Regional Forester "how the Six Rivers was doing" and to provide a document that would guide the Six Rivers Forest Supervisor and staff. A great deal of stock was put into this GII; the Regional Office viewed the Six Rivers as a linchpin in the vitality of California's timber supply and forest management.

Cronemiller and Kern's summary findings to the question: "How are we doing on the Six Rivers?" pointed to a fundamental insufficiency in "the organizing and management effort put forth by each member of the Six Rivers team and the leadership and help from this office [the Regional Office]." The inspectors believed that, in order for the Six Rivers team to exert the effort required to organize and manage, they first had to have a "live interest in the subject." With that interest clearly lacking, they framed the shortcoming as, at heart, a "training problem of highest priority—that of stepping up the interest and working knowledge in the basic principles of getting things done efficiently" (Cronemiller and Kern 1949: 38). The inspectors recognized that, "with only three years under its belt," some of the difficulties they observed on the Six Rivers were undoubtedly "lingering symptoms... [of] establishment and orientation problems." But the report admonished the forest and the regional office to fully diagnose the list of weak areas identified by the inspectors. The most gaping insufficiency area was the lack of "clear-cut objectives established and known to all concerned with their achievement." The second problem area was the need for "controls" to achieve "closer adherence to standards." In this vein, Cronemiller and Kern wrote:

|

"The Forest is not a series of crises and

projects, but a vehicle in need of ordinary and preventative maintenance. . ."

|

We feel it is timely for a shift in emphasis in administration. The organizing stage should be considered as completed, and the Forest now established as a part of the local province. The Forest is not a series of crises and projects, but a vehicle in need of ordinary and preventative maintenance, in this case applied to human and natural resources.

As a symptom of this ailment, they observed:

Although the CCC program has been extinct for practically 10 years there is still a marked tendency to visualize the administrative job as a series of projects.

Their recommendation? A regular program of general and functional inspections, with follow-up. The inspectors also cited the need for improved property, supplies, and equipment management and the imperative to cut the costs of automotive accidents on the Six Rivers (op. cit. 42). A third large problem area was in financial management and "the need for clear-cut priority selection of projects from the work project inventory." A symptom of this malady was that the forest had used $1,400 of "hard-earned" maintenance and improvement money to purchase paint that was often used unnecessarily. . . .

In all seriousness we believe the Six Rivers verges on being 'paint happy.' It is safe to assume that all the paint and brushes can soon be stowed for some time. The money and men therein saved will go a long way toward accomplishing other higher priority work. . . [op. cit. 43].

Regarding "morale and team spirit," Cronemiller and Kern perceived:

Basically the forest is not too closely knit. It was formed from three forests in two regions. It is strung out with no inter-district problems of major import. Radio has increased the sense of unity, yet restricting its use to pure business makes for formality rather than cohesiveness. Some effective efforts have been made to enhance esprit d' corps, [t]he manner of use of the pronouns, we, and they, indicated there was not always a good spirit of team play [op. cit. 47-48].

|

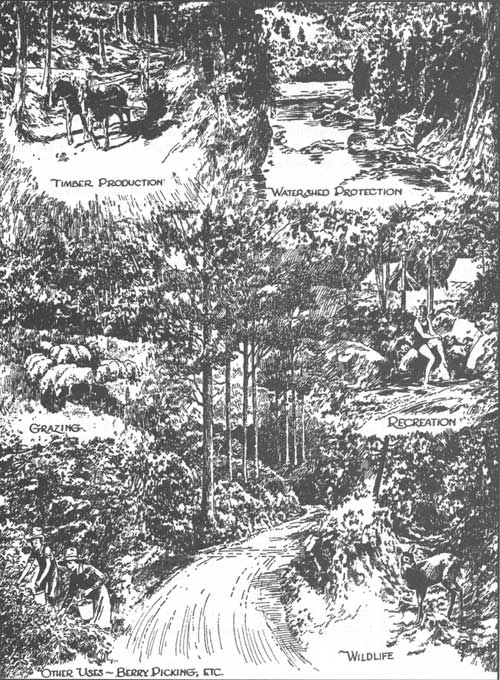

| This page from the 1941 USDA, Forest Service publication, New Forest Frontiers for: Jobs, Permanent Communities [and] A Stronger Nation, idylically illustrates the concept of multiple use. Multiple use was a cornerstone of the Forest Service from its inception, but it was not codified as legislative intent until the 1960 Multiple Use - Sustained Yield Act. |

One outcome of the 1949 GII and the strong encouragement to step-up the forest's Information and Education program was that, in June 1950, Forest Supervisor Fischer released his compilation titled: "A Prospectus of the Six Rivers National Forest." In it, Supervisor Fischer outlined the purposes for which the Six Rivers was established. He traced the lineage of reasoning to the famous letter to (and ghost-written by) Gifford Pinchot, signed by Secretary of Agriculture Wilson on the occasion of the 1905 Transfer Act that moved what is now the Forest Service from the Department of Interior to the Department of Agriculture. The three guiding principles in the letter were "the greatest good for the greatest number in the long run," "multiple use management," and "decentralization." [50] Aligning with those core tenets, Fischer gave the following purposes for creating the Six Rivers:

1) To effectively and efficiently administer and improve the public lands on the Six Rivers National Forest within the framework of existing policies and prescribed standards.

2) To integrate the resources of the National Forest more closely with the economy and with the people which depend on these resources, or will depend on them eventually.

3) To assist in bringing forestry and consciousness of forests as a crop to an area where they are badly needed and where it is not yet too late to provide for good management on a large proportion of the productive area, and to foster in the people of this area a sense of responsibility for the future.

4) To bring knowledge of the value of the national Forest lands and the U.S. Forest Service to a large group of people whose livelihood and interests lie mostly in forests and to secure their support in the American forestry enterprise [Fischer 1950: 5-6]. [51]

Fischer cited the push to create the Six Rivers as being philosophically in-step with the Forest Service's policies of decentralization. He also more succinctly identified the fundamental reason for creation of the Six Rivers: "This move merely recognized the administrative problem of managing these lands by setting the base of operations in the area served by them." This capsule statement was tied to much larger and more complex forces that were rooted in the rich and virtually untapped resource potentials of the area encompassed by the new national forest (Fischer 1950: 1).

The Formidable I & E Job

Working both to influence private forestry practices and to gain support from the general public regarding forestry affairs were colossal preoccupations on the Six Rivers during its early years. Given the private-to-government ratio of timber land in the north coast, practicing forestry on federal lands and ignoring private lands would ultimately prove futile in fostering the long-run well-being of the area. In terms of timber volumes, there were an estimated 60 billion board feet in and adjacent to the Six Rivers, while only 13 billion were publicly owned. [52] Precutting exchange agreements, demonstration areas, Forest Service and cooperative studies, and a substantial public relations campaign to regularly and visibly point out the advantages of forestry—particularly the federal brand of forestry—were all tools plied in the effort. The Forest Service believed that California's newly adopted Forest Practice Rules were insufficient and that "quietly, but firmly," the Six Rivers should "publicize our position that more than the Forest Practice Rules are needed for maximum timber production and sustained yield and employment." [53]

The "I & E" or "information and education" job to be done by the Six Rivers was staggering, especially in light of "the openly antagonistic attitudes of many people and groups toward the Forest organization at its inception." To give the new forest a face, a recording wire connection with radio station KIEM in Eureka was installed in the Supervisor's Office. An estimated 88,000 people were then able to tune-in for up-to-date information about the Six Rivers during its newscasts.

In contrast to the direct public involvement paradigm that developed later, in the 1960s and 1970s, Fischer metaphorically explained how the Forest Service and the early Six Rivers administration perceived its connection with the public:

The relationship of the public, the law makers in Congress, and the Forest Service may be likened to a corporation. The public at large are the stockholders in the enterprise, Congress is their board of directors whom they elect, and the Forest Service is the operating organization [that follows] the dictates of the board of directors. Therefore, [as] persons or people, the public do not have any direct authority over the forest organization any more than an ordinary stockholder does in a big corporation. They do have a direct responsibility to their board of directors, however, and should exercise that responsibility. It is felt that it is a duty of the forest organization, therefore, to inform the public so that they can exercise their responsibility. This is one of the major objectives in this field [information and education] for the Six Rivers organization [Fischer 1950: 25].

Inspectors Cronemiller and Kern had a penchant for characterature and, in their 1949 inspection report, they classified the publics served by the Six Rivers into five general groups:

The lumber industry group showing signs of emerging from a liquidation status to one with a semblance of forestry, perhaps even keeping its forest land productive and violently against any interference in its business by government.

The white collar group, the ladies and others without a direct interest, babes in the woods who are ready to be interested in keeping forest land productive, maintaining payrolls, game in the hills, fish in the streams; would hope the area would be a good place to live for their children and for grandchildren.

The agricultural group, reactionary in leadership, anti-public ownership, anti-government controls, subventions, etc., except it be for some of their own products. Thinks in terms of tax bases.

The labor group which is coming of age and will soon be taking a part in public affairs. Open to suggestions for programs.

The transient recreation group interested in fish and scenery, intelligent, well to do, leaders in their own communities, like to learn of our job and our problems [Cronemiller and Kern 1949: 10, 18, 33-34].

A job-load analysis, completed by the Six Rivers in January 1948, indicated the need for an additional resource staff position in order to allow the forest supervisor to give more emphasis to administrative management and for the person filling that job to work on priority, forest-wide "fact-finding and planning phases of key lands and resource management problems." Of the 18 professional positions established for the forest, only 10 of them were filled (Cronemiller and Kern 1949: 43-44).

The press was invited when Regional Forester Perry Thompson came to the Six Rivers in April 1947 and held a series of conferences with officials of the new forest. [54] Thompson stressed the mutual goals of federal forestry and private lumber operators noting that, although the parties do not always agree on methods to achieve continuous yield, the basic aims were identical: "We both want to keep forests producing and lumber mills in continued operation." Thompson also talked about the Forest Service's goal of being a stabilizing force to local communities: "It's part of our philosophy to prevent the boom and bust cycle that has left lumber ghost towns in parts of the state.... Here in the Northwestern California coastal area, I believe there is time to profit by the mistakes that have been made in other areas.... Eventually, the Six Rivers forest will be a center for large scale experimentation in logging practices in cooperation with state forestry." The primary task though, noted Thompson, was to complete a timber inventory before "the vast unused timber stands are opened." Thompson used the interview to, again, state the Forest Service's neutrality regarding re-introduction of Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas' Roosevelt Memorial Redwood bill (HT 4-13-47).

Congresswoman Douglas and the Roosevelt

Memorial Redwood National Forest

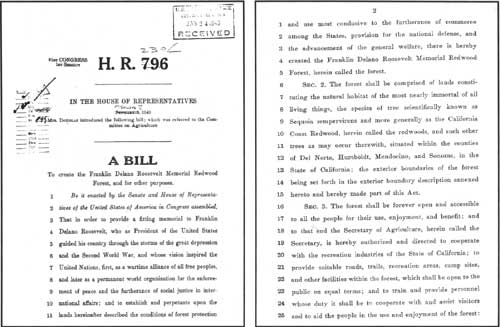

The Six Rivers' I & E job was made considerably more challenging by the confusion with and rancorous debate over the controversial Douglas Bill. Representative Douglas' bill proposed establishing a Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial Redwood Forest. Although there were several iterations of the bill that differed in important ways, the stated purposes of H.R. 6201 were:

1. To provide a fitting memorial to the late President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and

2. To establish and perpetuate upon the lands included therein the conditions of forest protection and use which will best serve the welfare of the people of the United States.

The forest was to be comprised of "lands constituting the natural habitat of California coast redwood." With the exception of four specified memorial units, the redwood memorial forest was to be managed under two modes: the Forest Service would administer most of the redwood forest's 2,385,000 acres under sustained yield management precepts while the National Park Service was to administer about 180,000 acres of land comprising the four memorial units for their "permanent preservation for scientific, educational, recreational, and inspirational purposes" (USDA, FS 1946: 6; U.S. Senate 1967: 2).

At Douglas' request, the Forest Service undertook a "brief survey to determine the economic effects of Bill H. R. 6201 on the industries within the Redwood Region should the Bill be enacted." This "brief survey" comprised about 150 pages and was, by Forest Service standards of the day, lavishly illustrated with charts and maps. [55] The report's conclusions were summarized in terms of "who would lose" and "who would gain;" the picture painted showed that the long-term gains to the region's timber and recreation resources clearly out-weighed the losses. The report predicted that the boom and bust cycle that had characterized the north coast timber industry, particularly the redwood industry, would be replaced by a far less volatile scenario under the Forest Service's sustained yield practices. In turn, that more stable economic context would provide a cornerstone of community and north coast regional stability. The study's summary stated:

. . creation of the Roosevelt Redwood Forest would cause a probable loss to certain individual interests within the Redwood region. This loss with the exception of excess profits and summer grazing of timberlands would be primarily an inconvenience based on disagreement with the philosophy of federal ownership and regulation which may change established practices and habits.

The study indicated that creation of the 'Forest' would enable the maintenance of a steady level of industrial development for present and future generations, and would prevent a slow decline of basic values and eventual collapse of the main industry of the area [USDA, FS 1946:16-20].

Interestingly, in her memoirs, Representative Helen Gahagan Douglas credited crafting of the redwood bill to Gifford Pinchot, the first Chief of the Forest Service and former Pennsylvania Governor. Noting that Pinchot drafted the bill just before his death, she also revealed that Walter Reuther's United Auto Workers Union had footed the bill's research costs (Douglas 1982: passim).

|

Leadership consistently went out of its way to

disassociate itself from the

Douglas Bill.

|

Even though the Forest Service study of Douglas' bill clearly supported creation of the redwood memorial forest, leadership within the Pacific Southwest Region did not wish to link its nascent national forest with contentiousness over Douglas and her bill. In fact, in any public forum, the new national forest's leadership consistently went out of its way to disassociate itself from the Douglas Bill which, in the fall of 1946, was pending in Congress. For example, as what would become the Six Rivers National Forest was being pulled together, an article in the Humboldt Standard noted:

. . In analyzing the significance of the move [to consolidate parts of three national forests into one], it is appropriate to point out that it has nothing to do with, nor any connection with, the so-called Helen Gahagan Douglas Act, now pending in Congress, which proposes the creation of a gigantic redwood national forest area.... Creation of the new national forest by merging adjacent units of three older forests and the redwood purchase unit has been under consideration for some time, in the interest of a more efficient management of national forest land on the coast range. The chief reason for the transfer of these areas to the new forest is the growing industrial development and utilization of the heavy stands of un-cut commercial timber on the west slopes of the Coast range, which will be processed and shipped from ports along the Pacific coast (HS 11-6-46). [56]

Though claiming neutral ground on the Douglas Bill, the Forest Service clearly played a significant role in providing congressional and public information on its economic and social ramifications. The proposed Roosevelt Memorial Redwood National Forest would include land in Del Norte, Humboldt, Mendocino, and Sonoma counties and would stretch for more than two hundred miles southward from the Oregon-California border. Its width would range from 6 to 30 miles, and the area was estimated to contain 52.5 billion board feet of timber, with 36 billion of it in redwood.

Writings in support of the new memorial forest were commonly zealous and tinged with Biblical allusions to destruction and redemption. One writer, for instance, noted that of all the redwood lands that have been cutover through the late 1940s, 56 percent now grow little to no timber.... "Yet for all this wasteful death, it is declared there could still be a resurrection day" (Powers 1949:145-146).

|

"Yet for all this wasteful death, it is declared

there could still be a resurrection day"

|

The Eureka Chamber of Commerce came down in solid opposition to the Douglas Bill. In stating its position, the chamber declared its "unqualified disapproval of, and its militant opposition to H. R. 6201 [because it would] remove from private enterprise and place under the control of the Federal Government practically the whole of the Coastal Redwood belt extending from the Oregon border to Bodega Bay [and] render impracticable the continued operation of many existing small individual mills [resulting in] immeasurable economic loss and the serious weakening of local government" (CR 11-13-46: 1).

California's legislature also opposed the measure and sent its Joint Resolution to Congress, protesting creation of the Roosevelt Memorial Redwood Forest, on May 22, 1947 (CR 5-28-47). In 1949, another Humboldt Times article underscored the Six Rivers' stance on the Douglas Bill, then in congressional committee:

While on the subject of redwoods, it is emphasized that the Six Rivers' personnel are not propagandizing for passage of the controversial Douglas bill....

[Quoting Administrative Officer Charles Everhart:] 'The Six Rivers National Forest was started before the Douglas bill was ever thought of. Its location is apart entirely, and its timber types are basically different. Also, we are a separate organization—although if the Douglas bill should pass, that area would be under the National Forest administration the same as ourselves, with the exception of that which would come under the National Park Service' (HT 3-13-49).

In mid-1949, having reintroduced her Roosevelt Memorial Redwood Forest bill earlier in the year as H. R. 2394, Representative Douglas asked the Forest Service to incorporate recommended changes to the bill that had been made by the Public Affairs Institute (Douglas 6-7-49). Perhaps dragging their feet or perhaps due to the complexity of the job, the two-week turn-around requested by Douglas stretched out into several months. By letter of January 3, 1950, the Secretary of Agriculture transmitted the re-crafted bill and exhorted Douglas that the draft was prepared. . .

as a legislative service to you. It constitutes no commitment as to the position which this Department can take with respect to the bill. . . . In all fairness, I should say that the prescription under which the bill was drafted does introduce some features which are not in accord with policies of this Department [Brannan 1-3-50].