|

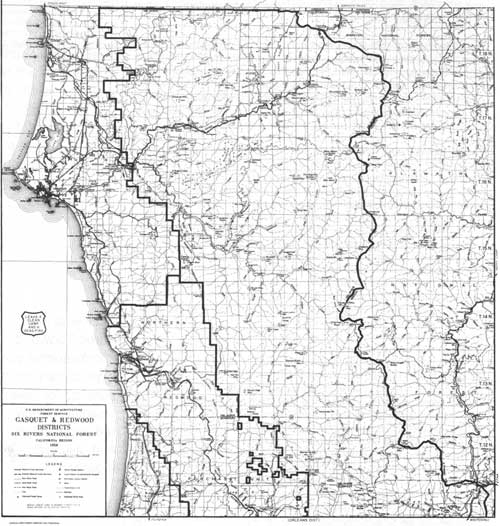

A History of the Six Rivers National Forest... Commemorating the First 50 Years |

|

The 1960s... Paradigm Lost

The Thousand Year Flood... An Agent of Change and Re-Consideration

|

. . . before the floods receded, accusations

abounded that forest land management practices were prime culprits in downstream destruction.

|

Called "The Thousand Year Flood," the catastrophic deluge that occurred on the Six Rivers and surrounding areas in December 1964 caused hundreds of millions of dollars worth of damage. The Six Rivers, by this time, had been established for 17 years and had powered an intensive land use program, relative to what the land base had sustained while it was on the fringes of the Klamath, Trinity, and Siskiyou national forests. Coupled with an awakening of environmentalism, before the floods receded, accusations abounded that forest land management practices were prime culprits in downstream destruction. The weight of the devastation—images of homes and dead, bloated cattle carried down the rivers, of families stranded on roof-tops, of mammoth log and debris jams dynamited to salvage remaining bridge spans, of landslides the size of small towns—triggered the human response to try to find a reason for the devastation in order to guard against its recurrence.

The direct cause was relentless, warm rain that started on December 18 and continued through Christmas. The higher elevations already had a snow pack which, in most areas, was melted by the rain. The foot of "Founders Tree" in the Southern Humboldt County redwoods is 50 feet above the Eel River's normal high water mark. The 1955 flood left a high water mark on the tree 16 feet above the base; the 1964 flood left its mark 31 feet above the base of the tree (USDA 1965: i).

|

| The dashed line penned on this photo of the engineering office at Orleans Ranger Station shows the water level at the height of the 1955 flood. Taken on December 22, three hours after the flood waters started to recede, the event prompted moving the offices to higher ground. US Forest Service photo |

|

| With the swollen Klamath River on the right, its flood waters severely damaged State Highway 96 during the December 1955 flood. This section of the highway is between Bluff Creek and Orleans, near Slate Creek. US Forest Service photo |

Orleans District Ranger, Joseph Church, recounted the scene that left the small community of Orleans with one death, the Orleans Klamath River Bridge destroyed, the elementary school burned down, State Highway 96 and other roads washed out in many places, and many homes and other improvements destroyed or damaged:

. . . it was obvious that a tremendous flood was occurring and that it was going to be worse before it got better. The rain was still falling very hard, it was still warm, and a powerful wind was blowing which blew spray off the waves the river was making. The noise of the river was overpowering and frightening, and its surface was a mass of racing debris, foam, great waves and noise. The water surface had erased all marks of the 1955 flood except for the number '1955', the sight of which came and went as the waves rose and fell.

|

"The noise of the river was overpowering and

frightening, and its surface was a mass of racing debris, foam, great waves and noise."

|

At about 4:00 p.m. the same day, December 22, Church went to a safe vantage point to check on the condition of the Orleans bridge over the roiling Klamath River. From behind the ranger district's fire warehouse he saw a...

line of heavy debris [that] rode down the river in what seemed like a continuous tumbling flexible raft. The crest of the waves seemed to move in cycles so that for awhile the trough would be at the bridge resulting in the free passage of water and debris under the bridge. But then the cycle would slowly change until finally a grim sight of leaping waves and crashing debris, all accompanied by the thunderous boom of the impact, would appear.... As I stood there and watched, the portion of a gold dredge, now a floating steel ram, rolled down against the bridge. The wave trough was under the bridge. The portion of it was gone and the unremitting mass of logs, trees, house parts, barrels, etc., supported by a river rolling about 25 - 30 MPH continued the battering. Now the booms were more regular, a grim sound (Church 1965).

About an hour after Ranger Church viewed this scene, the bridge collapsed, further cutting-off the community from outside help. Though the storm continued through Christmas, by the night of the twenty-third, it was subsiding and the rivers were slowly receding. At the Orleans Ranger Station, rainfall had been measured for the duration of the storm (Church 1965):

| Saturday | 19 December | 0.73 inches |

| Sunday | 20 | 0.90 |

| Monday | 21 | 2.24 |

| Tuesday | 22 | 5.10 |

| Wednesday | 23 | 5.52 |

| Thursday | 24 | 2.07 |

| Friday | 25 | 0.92 |

|

"Now the booms were more regular, a grim sound"

|

All Six Rivers National Forest ranger districts had similar experiences. Rivers swelled and undercut mountainsides, bridges were knocked-out, roads fell away, all manner of improvements were severely damaged or destroyed, and slides took a heavy toll on both natural and human-made resources. Forest Supervisor Wes Spinney surveyed the Six Rivers by Army helicopter and employees began tallying the damage. Preliminary estimates, published in a special flood edition of a Eureka newspaper, reported that the Six Rivers lost at least 50 miles of Forest Service roads which would require complete relocation and construction; 45 major stream crossings had to be rebuilt or significantly repaired; 65 million board feet of timber—45 mmbf of which were unsalvagable—were lost in landslides; most recreation improvements suffered severe damage or were destroyed; 1,400 miles of fishing streams suffered significant scouring, siltation, and debris jams. The question of whether streams could naturally regain their fish spawning capacity was up in the air.

|

| The 1964 flood reconfigured Bluff Creek, destroying the bridge near the creek's confluence with the Klamath River. This March 1966 photo shows the Bailey bridge across the Highway 96 crossing of Bluff Creek, looking upstream at the newly-cut channel. US Forest Service photo |

|

| This aerial view of Patrick Creek Lodge shows the aftermath of the 1964 flood. Note the log debris piled-up where the Highway 199 bridge crossed Patrick Creek. US Forest Service photo |

In its information to the press, it appeared that the Six Rivers was touchy about public criticism and was making an effort to address accusations that its forest management practices had significantly contributed to the flood's devastation. Images of damage supplied by the Six Rivers focused on and underscored the ruin and loss from huge landslides on virgin forest land: one example being a 45-acre slide at the forks of Harrington Creek and the South Fork of the Smith and another near Bear Basin Butte where seven million board feet of timber were destroyed by a slide two miles long and up to 700 feet wide (ENI 1965: n.p.). [82]

|

| Closed for the winter, indeed! Willow Creek Campground was inundated with eight to 12-feet of silt as a result of the 1964 flood. US Forest Service photo |

A Changing Context, and New Problem Definitions

Nationally, the 1960s were a decade of stepped-up construction on the forests, and the Six Rivers reflected that trend. The Forest Service outlined this initiative in its Development Program for the National Forests, published in 1960. With the emphasis on intensive management of water, timber, range, recreation, and wildlife habitat, hard targets were set for commodity production and developments. [83] For timber harvest, the program set the long-range goal for the national forest system at an annual harvest of 21.1 billion board feet of saw timber by the year 2000, on a sustained-yield basis. That number reflected the portion of the national need for saw timber which the national forests "could reasonably be expected to produce under intensified management." Similar increases in the amplitude of management were evident in other resource areas as well.

To support this program, a beefed-up construction and maintenance schedule was set in-motion. In addition to completing work on a backlog of housing needs for field officers and fire-related improvements, there was also a short-term program for new construction of dwellings and related improvements, service buildings, and lookout structures. The communication system, including radios and telephones was to be modernized; and aircraft landing fields, heliports, and helispots were to be constructed or refurbished (USDA, FS 1960: 7-10, 21).

One of the significant additions to the Six Rivers National Forest during the decade of the 1960s was the Humboldt Forest Tree Nursery, established in 1962. Being the "primary commercial species with which the National Forest lands are reforested," during its first decade, the nursery raised, from seed, mainly Douglas fir, ponderosa pine, and redwood. Other species were reared for testing and special plantings in campgrounds, Forest Service administrative sites, and other special areas. By 1965, between five and six million trees were grown annually, and it was estimated that production could be expanded to 30 million trees. Seed was collected from target areas on the forest with the source location and elevation recorded to insure returning the seedlings to comparable areas. At the end of the growing season, the six to eight inch seedlings were lifted, ready for planting or cold storage. Because good seed years were erratic, the nursery built up a large seed bank during those years to keep production stable.

Interestingly, a 1966 pamphlet about the nursery stipulated that: "Male machine operators do the heavy work in preparing the beds, seeding and lifting of the seedlings. Women do the job of weeding, sorting, culling, grading and packing of the seedlings in crates" [84] (Six Rivers National Forest Humboldt Nursery 1966). By 1976, Humboldt Nursery included 180 acres and had supplied 88 million seedlings to the Six Rivers, Klamath, Mendocino, Shasta-Trinity, Siskiyou, Siuslaw, Umpqua, and Willamette national forests as well as to the Bureau of Land Management in both Oregon and California.

[...text missing...] history during which fundamental institutions and beliefs were called into question. The 1960s read as a litany of protest; a sense of anarchy was in the air. The Civil Rights Movement that was beginning to bubble into the American consciousness in the mid- and latter-1950s burst into our living rooms in 1963 with the televised brutality of Birmingham, Alabama's public safety officer, Bull Connor, unleashing dogs and using electric cattle prods and high pressure hoses to break-up a non-violent, protest demonstration by African Americans. In June, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People activist, Medgar Evers, was murdered in Jackson, Mississippi; in September, a bomb was detonated in a Birmingham church, killing four black children; and still, Congress failed to pass the Civil Rights Bill. In August that year, the massive March on Washington was also televised; it was at this event that Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his compelling "I have a dream..." speech. In November, President Kennedy was assassinated, rocking the nation at its foundation. "Freedom Summer," in 1964, intensified voting registration drives in the American South, touching-off another wave of murder and brutality: 15 civil rights workers were murdered in the South during that single year.

|

| Trees being planted after a harvest on Lower Trinity Ranger District. Seedlings were grown at the Humboldt Nursery from locally-produced seed. US Forest Service photo |

Though President Johnson, as a memorial to former President Kennedy, was able to shepherd passage of the Civil Rights Act in June 1964, violence and protest continued to tear at the fabric of American life. To add to the turmoil, although American "military advisors" and other aid had been going to South Vietnam for a decade, in 1965 the first US combat troops were shipped there. Amid protests over the US involvement in Southeast Asia, racial violence burned on. In 1965, Black Muslim leader, Malcolm X, was assassinated. The Watts riot in Los Angeles was just one of over 30 major, urban, race riots that erupted during 1967 and 1968—hitting such cities as Portland and San Francisco in the West, Jackson and Tampa in the South, Detroit and Chicago in the Mid-West, and Newark and New Haven in the East. As the arrival of body bags escalated from the Tet Offensive in Vietnam, 1968 marked a year of numbing shock: Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered... and just two months later, Robert F. Kennedy was murdered while campaigning for the presidency. Later in the year, as Democratic candidates met at their national convention in Chicago, anti-war activists demonstrated outside; the ensuing, televised "police riot" had the effect of bolstering the growing "law and order" backlash and propelling the election of Republican, Richard M. Nixon, in November 1968.

This ground-floor re-examination of assumptions and core values stirred by events of the 1960s was reflected in the federal legislation of the 1960s and '70s: the Multiple Use-Sustained Yield Act, the Wilderness Act, the National Forest Roads and Trails Act, the National Historic Preservation Act, the Architectural Barriers Act, the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), the Environmental Quality Act, the Youth Conservation Crops Act, the Endangered Species Act, the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act, the National Forest Management Act, the American Indian Religious Freedom Act, and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act were all products of those turbulent times: reflecting reshaped values and an effort to foster a new order. All of these laws—and scores more—fundamentally engendered change in how the Forest Service perceived its basic mission and institutional values, what kinds of skills were required to fulfill its recast mission, and what its relationship would be with the public and with forest-reliant industries. These perceptions have been slow to take hold but, nonetheless, reflect immense change in how the National Forest System Lands are managed. This period also provides clues in answering the question of why today's Forest Service is perceived as being on the other side of the fence as "environmentalists" when the agency's institutional roots are as leaders in resource conservation.

|

| Specialized tractor in-use at the Humboldt Nursery in McKinleyville, 1964. US Forest Service photo |

The Northern Redwood Purchase Unit... Case Study of A Paradigm Lost

|

Within that mindset was the assumption that

old-growth redwood was inevitably—except for a few, small "museum" stands— a thing of

the past.

|

An illustration of the Six Rivers' difficulty in transitioning from the model of maximization to a model more reflective of contemporary values is within the story behind dissolution of the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit. First administered as part of the Trinity National Forest, when it became part of the Six Rivers, the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit was loosely administered through the Gasquet Ranger District. In January, 1958, a separate Redwood Ranger Station was formally established to manage the NRPU lands—lands from which the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest (YREF) had been sequestered. (See earlier chapter.)

To get a redwood research program underway at the YREF, in 1956, Russell LeBarron, Chief for Research in the California Forest and Range Experiment Station's Forest Management Division, negotiated an agreement with the redwood division of Simpson Lumber Company for experimental redwood logging. The operative research paradigm was timber harvest—to unlock the secrets of redwood in order to discover how best to manage stands for sustainable yield. Within that mindset was the assumption that old-growth redwood was inevitably—except for a few, small "museum" stands—a thing of the past. The focus, then, was how to most effectively convert old-growth to healthy, productive second-growth stands that would continue to contribute to a robust north coast economy.

Simpson was chosen as the partner in these experiments largely because the company owned 1,170 acres on the upper High Prairie Creek watershed, contiguous with the YREF's 935 acres on the lower reaches of that watershed. Simpson agreed to contribute $62,000 to a cooperative work fund and to log according to experimental plans in return for the YREF making 25 million board feet of merchantable redwood available exclusively to Simpson at Forest Service appraised stumpage values over the seven-year life of the agreement (Boe 1983: 2, 6 and USDA, FS 1970: appendix). LeBarron recruited Kenneth Boe from the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station at Missoula, Montana to develop the study plan and to perform the on-the-ground administration for the Simpson agreement (Boe 1983: 1).

Boe moved himself and his family into the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest headquarters in late 1956. In his struggle to come to grips with his new assignment—a forest where some of the tree limbs outsized the girth of an average tree in the managed lodgepole pine stands in which he'd most recently worked—Boe developed the YREF's first study plan. Boe's plan viewed the research and management problem much as it had been framed two decades earlier by Hubert Person: foresters needed sound information to "effectively convert unmanaged old-growth redwood forests to younger managed stands." Boe's plan was designed to test three reproduction methods within a harvest framework: selection, shelterwood, and patch clearcuts (Boe 1983: 9). In 1958, the first redwood harvest was initiated under Boe's study plan, designated Yurok-1958. It consisted of 62 acres of shelterwood cut, 52 acres of selection, and 60 acres in clear cut blocks; it was located in the southeast portion of the YREF (Boe 1983: 10). [85]

Simultaneously, the Six Rivers National Forest had established the Redwood Ranger District in January, 1958 to manage the NRPU lands out side of the experimental forest. The new ranger district personnel were co-located with the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest personnel. To meet critical housing needs for Redwood Ranger Station employees, two residences were built at the administrative site in 1958 and 1959. They were identical, wood-framed, three-bedroom, one-bath homes.

|

Activity at the Yurok/Redwood administrative site

skyrocketed and the demand for reliable scientific data on redwood forests and utilization

mounted.

|

Activity at the Yurok/Redwood administrative site skyrocketed and the demand for reliable scientific data on redwood forests and utilization mounted. The new district ranger at Redwood, Ted Hatzimanolis, initiated creation of a redwood library in the headquarters building and enlisted the Experiment Station's help in acquiring up-to-date literature to answer questions or help solve problems of forest managers, researchers and the public (USDA, FS Hatzimanolis 1959). In 1960, the second redwood block was harvested on the YREF by Simpson in accord with Boe's plan. Imaginatively dubbed "Yurok-1960," it consisted of 49 acres of shelterwood, 57 of selection and 56 in clearcuts of 8 to 16 acres located on the northwest side of High Prairie Creek. In addition, there were 43 acres placed in a reserve (Boe 1983:10). On the other side of the fence, at Redwood Ranger Station, timber harvests crescendoed in the first half of the 1960s yet, by the close of the 1963 logging season, activity at the experiment substation was in a decline. The seven-year agreement between the Division of Forest Management Research and Simpson Lumber Company was winding down, with the cumulative harvest totaling 413 acres with 47,004 mbf redwood, 5,544 mbf of white-wood and 29,134 mbf left in reserve. At this juncture, Boe set-up a project office on the Humboldt State University campus in Arcata (Boe 1983: 11). Significant windfall damage in 1964 within the Yurok-1958 block prompted a salvage harvest and a second cutting, notwithstanding that the 10-year entry schedule had not elapsed since the first harvest. A cooperative agreement was struck with Twin Parks Lumber Company of Arcata to carry out the harvest and conduct the additional harvest studies (Boe 1983: 12). Meanwhile, in May 1965, the cooperative agreement with Simpson lapsed. Harvest by patch clear cuts, averaging 14 acres and aggregating about 240 acres a year, became the norm for the old-growth redwood in the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit (USDA, FS Connaughton 1966).

But as logging activity settled-in with a sustained yield annual harvest target of 18 million board feet on the NRPU lands, other forces were in the wind. Through the early 1960s, pressure had been building behind the notion of a redwood national park. Scrambling for an alternative, the Forest Service sought to consolidate the lands in the NRPU—reducing the land base to 32,409 acres north of the Klamath River—and, at long last, to create the Redwood National Forest. But without the requisite acreage thought necessary to establish "an economic forest unit representative of the redwood forest type," Redwood National Forest never materialized (US Congress 1967: 20). In February 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson formally proposed creation of a redwood national park in northern California; the Department of Interior submitted legislation and introduced it to Congress. Senate hearings were held, but no further action was taken on the measure this time around. . . but it was clear that momentum for a new paradigm was building: a mindset that viewed the remaining old-growth redwood stands as something other than a timber and fiber commodity.

|

However, sustaining redwood lumber production was

not foremost in the

equation for the national park supporters.

|

An essentially identical bill was submitted in March, 1967 to the 90th Congress as S.B. 2515. In the Senate Report titled "Authorizing The Establishment of the Redwood National Park in the State of California, and For Other Purposes," the writers stingingly criticized the research paradigm that had guided Boe's and the Forest and Range Experimental Station's work at the Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest. The framers of the park strategy did not accept the necessity of the demise of old-growth redwood, and they believed the National Park Service and not the US Forest Service was the better bet in preserving the remaining old-growth stands under federal ownership. The report stated: "The research on the 935-acre Yurok experimental forest has been chiefly on the technology of logging old growth redwood. Obviously such findings are of limited utility as the last of the old growth nears" (US Congress 1967: 20).

Multiple use, with timber management holding the trump card, had been Boe's and the Forest Service's over-arching paradigm: to sustain the productivity and yield of redwood for the public through providing lumber, jobs, grazing, recreation, fisheries, and watershed benefits. This view is reflected in Boe's 1964 "Silvicultural Research Plans for Redwood and Douglas-fir Forests in California." In this nine-page publication, he noted the substantial dependence on wood products in the Pacific Northwest region of the state. He also noted that changes in demographics might "force some of these uses [i.e. grazing or recreation] to predominate over timber production in certain areas," but that the result is, again, a pressing need "for information basic to efficient timber production" (Boe 1964:1).

However, sustaining redwood lumber production was not foremost in the equation for the national park supporters. The framers of the park bill believed "that any initial adverse impact precipitated by creation of the park on the local economy will be temporary." Supporters argued that park creation would result in "substantial longrun benefits" through park development expenditures, new jobs, and addition of 950,000 visitors each year. Even though some redwood logging companies would be forced out of business and some workers dislocated, park supporters predicted that the conversion from "primarily a single industry economy based on timber" to a more diversified timber and tourism-based economy would have long run benefits for the north coast redwood region (US Congress 1967: 5, 7,10).

The bill to create the redwood park did not include subsuming the 935-acre YREF, but it did encompass nearly all the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit lands managed by the Redwood Ranger Station. This was a major bone of contention between the Forest Service and the State of California: Governor Reagan was convinced that NRPU lands should be exchanged in fee title for lands acquired for the park. To offset losses anticipated from buying-out substantial tracts of the land base of the major employer in Del Norte County, Rellim Redwood Company, the Forest Service agreed to accelerate timber harvests on the Six Rivers National Forest. But Governor Reagan argued that this increase should occur regardless of the formation of a redwood national park (US Congress 1967: 15). Ultimately, the idea of using NRPU lands as trading chips to exchange with redwood landowners within the boundaries of the new national park prevailed. The Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs concluded:

Exchange of the purchase unit holdings amounts to no more than shifting the Federal redwood holdings (which are now being cut by private operators) to a different location (containing magnificent stands now in danger of being cut) and changing management from cutting to preservation in a park. The grand plan [of the Forest Service] for an 860,000-acre Redwood National Forest was never realized. The small fragment which was acquired cannot bring sound management to the region, and research findings on old growth harvesting methods come too late in the history of redwood exploitation to be significant [US Congress 1967: 21].

|

| This early 1970s photo of a redwood log deck conveys the divergence of interest between environmental groups and the timber industry in California's northwest—often brokered by the Six Rivers National Forest. US Forest Service photo |

With signing of the Redwood National Park Act by President Johnson on October 2, 1968, the nearly 65,000 acres within the NRPU acquisition boundary shrank to 540 acres, as those lands were exchanged to private timber land owners for more desirable lands to form Redwood National Park (USDA, FS 1994: n.p.). Subsequently and ironically, the handsome Yurok Redwood Experimental Forest headquarters building was turned over to the National Park Service, though the experiment station retained work space there for some years under a cooperative agreement. The Forest Service no longer needed a ranger station there (Boe 1983:16). In 1976, a 150-acre Yurok Research Natural Area (RNA) was retained by the Forest Service from the remainder of the NRPU land to preserve old-growth redwood for observation and study. One-hundred twenty of these acres are mantled with "superlative old growth redwood;" volumes are well over 300,000 board feet per acre, and 30 percent of the stand is redwood. The remaining 30 acres is on alluvial flats. The RNA is administered by scientists at the Redwood Sciences Laboratory in Arcata (Boe 1983: 1 & 10). After the virtual abandonment of the Yurok/Redwood Station by the Forest Service, it was occupied partially and sporadically by a number of entities in addition to the National Park Service (USDA, FS 1995: 1). [86]

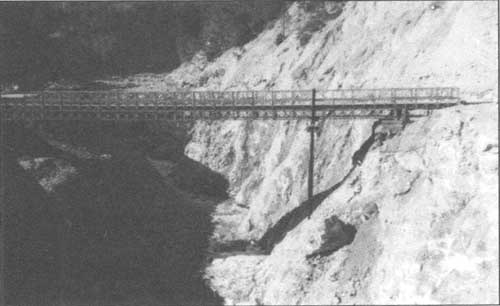

When Redwood National Park was established and the lands of the Northern Redwood Purchase Unit were used as trading stock, the allowable annual cut for the Six Rivers was reduced by 18 million board feet to compensate for the loss of timber land. But during Congressional hearings on the park bill, the Chief of the Forest Service offered to increase the annual allowable cut by 37 million board feet contingent on funding major access roads in Del Norte County. In 1969, the Six Rivers was, again, the subject of a General Integrating Inspection. In that GII, the inspectors expressed doubt that the funds for an accelerated road development program would be forthcoming from Congress and indicated that any increases in the allowable cut would probably come from the southern quadrant of the forest, not bringing many benefits to the economically hard-hit Del Norte County. The inspectors predicted that Del Norte County would more likely benefit from a predicted increased flow of timber over the Gasquet-Orleans Road, once that controversial road was completed (USDA, FS, RO 1969:16). The Gasquet-Orleans, or G-O Road is yet another story, best told in a history that focuses on the Six Rivers' second 25 years. [87]

|

| Construction work on the Gasquet to Orleans Road. US Forest Service photo |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

5/six-rivers/history/sec5.htm Last Updated: 14-Dec-2009 |