|

History of Tahoe National Forest: 1840-1940 A Cultural Resources Overview History |

|

CHAPTER II

The Environmental and Historical Context of the Tahoe National Forest Region

Physical Characteristics of the Area Encompassed by the Tahoe National Forest.

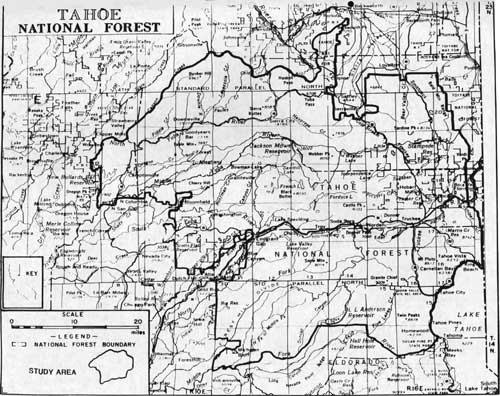

The area within the boundaries of Tahoe National Forest lies inside the geographical region of the Sierra Nevada and its foothills. On the western side of the forest the foothills are approximately 2,000 to 3,000 feet high, rising higher toward the east to the crest of the Sierra Nevada at approximately 8,000 feet. The forest straddles the crest, and takes in land as far east as the California-Nevada border. (Durrenberger 1959: 9; "The Irrigation of Nevada County" 1923: 1; USFS, Tahoe National Forest Map 1977). On the northeastern side of the Sierra Nevada within the Forest are broad, high valleys that have been the sites of extensive agricultural activities since the gold rush, while on the western side the valleys tend to be more narrow and rugged. (See below, Chapter III and IV.)

Both sides of the Sierra Nevada are drained by a system of rivers and creeks, those on the west draining into the Feather and Sacramento rivers and those on the east side into Pyramid Lake and the basins of Nevada. The formation of the Sierra Nevada, then, "has produced rather gentle slopes to the west which have been dissected by the copious streams of water coursing down its flanks to the Central Valley;" while the eastern side, in some areas "a precipitous wall," is more rugged. (Durrenberger 1959: 9)

The area within the Tahoe National Forest is drained by four major river systems: the Yuba, Bear and American on the west; the Truckee on the east. Of the four, the Yuba and American are the greatest, encompassing a far larger area than the Bear and Truckee.

The Yuba River can be divided into three sections — north, middle and south. The North Yuba basin is the largest, draining an area of approximately 304,530 acres (Leiberg 1902: 98). Its source is in the mountains east of the Sierra Buttes, and is fed by a number of important tributaries including the Downie River and Goodyear, Indian, and Slate creeks before joining the other branches of the system to form the main Yuba River (USFS Tahoe National Forest May 1977). The Middle Yuba Basin is the smallest in the Yuba system. It encompasses a drainage between two narrow parallel ridges three to six miles wide. Oregon Creek is its only major tributary (Leiberg 1902: 109). The Middle Yuba joins the North Fork west of the town of North San Juan. The South Fork system is nearly as large as the North Fork's, draining about 280,000 acres. The basin can be divided into two areas: east, near the crest of the mountains; and west, below the crest and into the foothills. The eastern portion is characterized by lakes and ponds of glacial origin, the west by two large ridges running in a generally east-west orientation. Of the two the southern ridge is the broadest, but is also cut by deep canyons, some of which are quite spectacular. Big Canyon Creek canyon has walls 1,000 to 1,300 feet high nearly its entire length (Leiberg 1902: 119).

|

|

TAHOE NATIONAL FOREST STUDY AREA (click on image for a PDF version) |

The Bear River basin within the forest consists of one major canyon and small tributary streams. The Bear arises near Yuba Gap and flows in a southwesterly direction toward Colfax before turning west and draining into the Sacramento River (Leiberg 1902; 138; USFS Tahoe National Forest Map 1977; Coy 1948: 34).

The basin of the American River, like that of the Yuba, can be divided into three sections: north, middle, and south. Only the north and middle sections are within the boundaries of the Tahoe National Forest; in fact the Middle Fork of the American is substantially the southern boundary of the forest. The basin of the American River is bordered on the east by the ridge of the Sierra Nevada west of Lake Tahoe, and on the north by the Bear River canyon (USFS, Tahoe National Forest Map 1977). The North Fork is "rocky and precipitous," drains an area of about 177,440 acres and is fed by a large number of tributary streams (Leiberg 1902: 145; USFS Tahoe National Forest Map 1977). The Middle Fork also drains a large area and collects water from a number of smaller streams within its drainage before flowing into the North Fork near Auburn (USFS Tahoe National Forest Map 1977; Coy 1948: 34).

The major river on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada within Tahoe National Forest is the Truckee. The Truckee flows out of the northwest corner of Lake Tahoe in a northerly direction for about twelve miles to a junction with Donner Creek, and then heads in a generally northeast direction into Nevada. It is fed by a number of lesser streams, including Squaw, Donner, Prosser, Alder and Martis creeks, and the Little Truckee River. (USFS Tahoe National Forest Map 1977)

The higher elevations of the Sierra Nevada also contains a large number of natural lakes. Most of these are small, but several have attained large dimensions. Among the largest are Tahoe, Donner, Webber, and Independence. Since 1850, Sierra Nevada streams have been dammed and reservoirs built. The forest has within its boundaries several large reservoirs, including New Bullards Bar, Bowman Lake, French Meadows, Stampede, and Prosser Creek, as well as many smaller dams and reservoirs. (USFS Tahoe National Forest Map 1977).

Mining and settlement of the area within the Tahoe National Forest began after the discovery of gold in 1848. The deposits that attracted miners to the area were of three types: river placers; Tertiary or "Blue" Gravels; and quartz lodes.

In geologic terms the youngest of these deposits are the river (or Quaternary) gravels. These were laid down as geological forces altered the slope of the Sierra Nevada. New stream channels were cut, eroding gold deposits laid down in earlier times into the modern river beds. These placers were small but rich, and were those worked early in the gold rush period (Durrenberger 1959: 155).

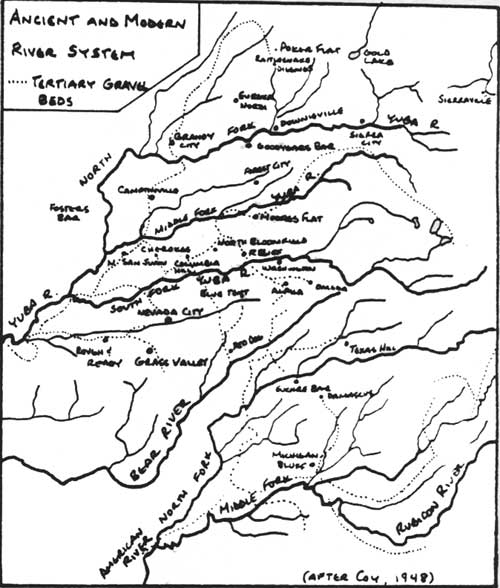

The other major form of placer gold in the Sierra Nevada was found in the Tertiary or "Blue" Gravels. The Tertiary Gravels were deposited by the ancient rivers of the young Sierra Nevada. The streams were slower and had more gradual slopes than the modern rivers, and thus laid down huge deposits of sedimentary material. When the Sierra Nevada were lifted higher, lava flows associated with the process filled some of the ancient channels and other canyons were blocked forcing new patterns of drainage. "The slope of the mountain range was tilted more to the southwest, so that the newer streams all had a decided tendency to follow a southwesterly direction." (Coy 1948; 4) The ancient Yuba River

was a mighty stream that drained the western slope of the Neocene Sierra through a territory now covered by Sierra, Nevada, Placer, and Yuba counties. Its debouche was near the site of present Marysville, not far from the channel of the present Yuba River. It soon forked, as does its later counterpart, its north fork rising as far as northern Sierra County, while its south fork took its rise near the crest of the ancient Sierra in what is now northern El Dorado County. It is to this great river that this district owes its rich auriferous gravels. (Coy 1948: 59)

|

| ANCIENT AND MODERN RIVER SYSTEM |

Thus the ancient Yuba, which drained much of what is now the western portion of the Tahoe National Forest, left behind large gravel deposits covering a wide area. The ancient American River was apparently not as large as . . . the Yuba; in fact, not much larger than the modern South Fork of the American. "No predessors in this period of the now existing Feather and Bear rivers have been found" (Coy 1948: 3,62). These Tertiary Gravels deposited by the ancient rivers were very rich. One estimate suggests that miners extracted $300,000 in gold from these deposits over the years (Durrenberger 1959: 155).

The "Mother Lode" is the popular name for the main quartz vein in the Sierra Nevada gold region. This name, given by the miners, is also applied to much of the gold mining area itself. The Mother Lode veins are generally considered to run from Coulterville in Mariposa County to Plymouth in Amador County. "North of the Middle Fork of the American River it splits up into a number of seams and cannot be described as one belt or lode." It is this system that underlies the quartz lode region within the National Forest (Coy 1948: 6). Quartz lode mines are scattered throughout the western portion of the forest. Among the famous quartz lode mining areas within the forest are the Alleghany and Sierra Buttes districts. (Clark 1970: 13)

The Tahoe National Forest covers a large forested area, much of which has valuable commercial timber. Within the boundaries of the forest are several woodland types of varying values.

In the foothill region of the forest, the western side is a zone called "foothill woodland," characterized by oak forest. Chief species include Live Oak and Blue Oak, as well as Digger Pines and California Buckeye. Typically fifteen to twenty percent of the ground is covered by trees. Higher up in the mountains is a zone of "Ponderosa Pine Forest." Within this zone are commercially valuable trees, including Ponderosa and Sugar pines Douglas Fir, White Fir, and Incense Cedar. This area usually spans the 3,000 to 6,000 foot region in the northern Sierra Nevada. Above the Ponderosa Pine forest are two zones: Red Fir forest in scattered areas above the Ponderosa zone from 5,500 to 7,500 feet; above the Red Fir forest is "Lodge-pole Sub-Alpine Forest," usually at an altitude of over 7,500 feet (Durrenberger, 1959: 59-61).

The land within the Tahoe National Forest is, in general, not extensively used for agricultural purposes, with the exception of grazing livestock. The mountainous terrain and cold winter weather limits the extent of cultivation. In 1902, John Leiberg estimated that of the 304,000 acres drained by the North Fork of the Yuba River, only 6,280 acres were cleared and in tillage. Most of these were in small patches adjacent to cabins, usually no larger than one or two acres. A similar situation existed on the Middle and South forks of the Yuba and on most of the American River drainage within the forest (Leiberg 1902; 98, 109, 119, 138, 145). These areas were located on valley floors or cleared areas on the lower elevations of the mountain ridges. Since that time cultivation in the region has not expanded very much. By 1900, agricultural production of many crops had reached their peak level. ("The Irrigation of Nevada County" 1923: 2)

Agriculture has centered on ranching of both sheep and cattle. "Farming in the mountain region is largely the production of hay and grain for wintering and feeding of range livestock." (Durrenberger 1959: 134) This pattern is true today, and was set early in the gold rush period (see below, Chapters III and IV). Livestock is grazed on lands within the forest in the high pastures during the summer months. The mountain valleys were also utilized very early for production of hay for winter feeding.

The area within the Tahoe National Forest is both varied in geography and the uses to which its natural resources have been put. Mountain rivers have provided valuable placer gravels and the water necessary for their utilization. Quartz veins have provided another source of gold. Mountain forests and valleys have sustained the commercial timber industry and livestock ranching. Much of the history of the forest revolves around the use, development and exploitation of these resources.

Pre-Gold Rush History of the Northern Sierra Nevada Region.

As was the case of most of the interior portions of California, the northern Sierra Nevada region was not settled until after gold was discovered in 1848. There was, however, some contact between whites and Native Americans, exploration by U. S. government expeditions, and transits of the area by pre-gold rush immigrants to California.

Exploration and settlement during the Spanish and Mexican periods was limited. During the Spanish period (1768-1822), a small number of expeditions were made into the interior of California, but these were largely aimed at locating runaway Mission Indians, chasing livestock, or examination of the terrain for possible future mission sites. Several of these expeditions, led by Lt. Gabriel Moraga and Lt. Luis Arguello between 1805 and 1817 skirted the foothills on the eastern side of the Central Valley as far as the Feather River. It is not thought that the Spanish expeditions entered the Sierra Nevada foothills within the Tahoe National Forest (Bean 1978: 43).

Activity increased during the Mexican period (1822-1846), but no permanent settlements were made east of the Central Valley. The ranchos granted to John Marsh near Mt. Diablo and John Sutter at the confluence of the American and Sacramento rivers were for a long period the only attempts at settlement within the Central Valley (Bean 1978: 66-67).

The growing American interest in the Trans-Mississippi West and California stimulated the U. S. government to dispatch expeditions to explore the region, produce accurate maps, and report back on the region's inhabitants and resources. The first of these that reached interior portions of California was that of Lt. Charles Wilkes, USN, who was sent into the eastern Pacific "in the interests of the American whaling industry" in 1841 After passing through the Pacific Northwest, a detachment of Wilkes' men traveled down the Sacramento River, rejoining the main body of the expedition in San Francisco Bay (Caughey 1970: 161-162). Wilkes' men apparently did not venture far into the Sierra Nevada foothills.

Perhaps the most famous of these explorers is John Charles Fremont, an ambitious and talented member of the Army Topographical Engineers. During his career as an explorer he undertook four expeditions into California. Fremont's expedition in 1845-1846 traversed the central portion of the Sierra Nevada over Donner Pass and down the mountains into the Central Valley. Fremont and his men moved up the Truckee River camping at Cold Creek south of Donner Lake on December 3, 1845. "All the way, they appear to have followed the traces of the Stevens-Townsend-Party of 1844, which had entered California via this route." (Egan 1977: 307) Fremont measured the altitude of Donner Pass as his men traversed it, and was within forty feet of its actual altitude. Fearing being caught by winter weather, the party moved quickly to the west and south, spending the night of December 4 in a mountain meadow.

Six days more was all it took for the men to work their way out of the mountains. But those six days were long and hard as they climbed in and out of canyons, along crests of ridges, through great stands of virgin timber, down the South Fork of the American River and through the foothill region . . . Tough going was putting it mildly, but once they broke into the open, they saw the rolling hills and valley oaks. (Egan 1977: 308)

The group arrived at Sutter's Fort a few days later.

While Wilkes and Fremont explored under orders from the U. S. government, private individuals were traveling overland from the U. S. into California. Beginning in 1841, overland immigrant groups entered California on foot or with wagons, crossing the Sierra Nevada as the last major obstacle on their journey. (Stewart 1962: passim) The first overland groups, however, did not cross the Sierra Nevada within what is now the Tahoe National Forest, but rather to the south at Sonora and Walker passes, or to the north along the Malheur and Pit rivers (Jackson 1967: 1).

The route up the Truckee River out of Nevada, up and over Donner Pass, and down the mountains into the Central Valley was discovered and opened by immigrants in 1844. The Stephens-Townsend-Murphy Party followed the Truckee River into the mountains. "The ascent of the Truckee River was a difficult route that involved interminable crossing from one bank of the stream to the other and at times it was necessary to follow a jolting passage up the stream bed itself." (IBID: 1) One member of the party, Moses Schallenberger, noted that "the river was so crooked that in one day they crossed it ten times in traveling a mile." (IBID: 1) Walking in water softened the hooves of the oxen; members of the party were forced to walk alongside the animals in the water and urge them on. Upon reaching the junction of Donner Creek and the Truckee, the party split into two groups: a pack train which would follow the Truckee; and the wagons which followed Donner Creek up to Donner Lake. The pack party followed the course of the Truckee to Lake Tahoe, and thus were the first white travelers to reach the shore of the lake. They moved south along the western side of the lake, and apparently ascended McKinney Creek to its headwaters, crossed over to the Rubicon River and descended into the Central Valley by way of the Rubicon, Middle and North forks of the American River (IBID 1967: 2-3). The wagons traveled west to Donner Lake. "They camped and spent several days exploring ahead in an effort to find a practical pass." (Stewart 1962: 71) The party decided to leave six of the eleven wagons at the lake, with a portion of their cargo to be retrieved in the spring, and attempted to cross the mountains with five wagons and all the remaining oxen. The party skirted the north shore of Donner Lake, and then camped in a meadow west of the lake. The laborious crossing of the pass was probably completed on November 25, 1844. Double teams of oxen hauled the wagons, which in several places were pulled up nearly vertical granite faces. Once over the pass, the remainder of the wagons were abandoned because of snow and a winter camp made near Big Bend (IBID: 72-73). The Stephens-Murphy-Townsend Party in 1844, then, deserves recognition for being the first to use the Donner Pass route and to take wagons across the mountains. It was the traces of this party that John C. Fremont and his men followed the next year.

Several members of this party returned east the next year, and the trouble they had had ascending the Truckee River canyon prompted them to look for another route that would avoid this stretch of the river. One of the members of the party described the new route they followed:

Leaving the lake (Donner), and the river which flows from it, to the right, we bore off to the northeast, for a wide, deep gap, through which we supposed that we could both pass, and leave the mountains. At ten miles, we crossed the North branch of Truckies River [sic] (Prosser Creek), a stream of considerable size. We traveled eight miles further, to the head of a stream, running to (from) the North West, which we called Snow River (Little Truckee River); as a heavy fall of snow, here obscuring our course, compelled us to halt. Snow continued to fall during this, and the succeeding day . . . when it ceased, we again proceeded on our journey, leaving the gap for which we had been steering, and bearing to the East, through a break in the mountain which follows this course of Truckies [sic] River . . . Having crossed this mountain, we came again, at five miles, to Truckies [sic] River, which we crossed and traveled down the south side . . . (Jackson 1967: 4)

The party traveled northeast from the area around Donner Lake and around the northern end of the Verdi Range before using Dog Canyon to rejoin the Truckee River below the rugged canyon area (IBID: 4-5). This part of the Donner route became widely used after 1845, and later fed other routes over Yuba, Henness, and Donner passes (Galloway, 1947: 30-31). One historian has asserted that no party after 1844 used the Truckee Canyon above Dog Creek (Jackson 1967: 13).

In the years that followed, until 1848 and the great overland migration of gold-seekers, this route was used by parties of immigrants. Once a party had reached Donner Summit, the route down the western slope was comparatively easy, with the ridge tops having only minor obstacles, providing paths down to the Central Valley. With the discovery of gold, the major route across the Sierra Nevada shifted to the Carson Pass and Johnson's Cutoff route south of Lake Tahoe. Nevertheless, the Donner Route was one of the most important pre-gold rush and gold rush era routes into California and was used by many. The most famous of these was the Donner Party in 1846, whose tragic story resulted in the pass being named after the leaders of the party (Stewart 1960: passim).

Before the discovery of gold, activity by the Spanish, Mexicans and Americans had little impact on the area of Tahoe National Forest, leaving no kind of permanent site or settlement. Largely ignored by the Spanish and Mexicans before 1848, the region was an obstacle to be overcome on the long and perilous journey to California. It was only with the discovery of gold in the Sierra Nevada that the mountains became a goal for immigrants. These "Argonauts" had the benefit of the earlier pathfinders' efforts in finding trans-Sierra Nevada routes, and it is these miners who first settled within the Tahoe National Forest.

Gold Rush California, 1848-1849: A Regional Overview.

Gold was discovered on January 24, 1848, at Coloma on the South Fork of the American River. An employee of Johann Sutter, John Marshall was supervising a crew of Mormons and Native Americans building a sawmill. After letting the the river water wash the trail race of the mill, Marshall noted some small nuggets and announced to his men, "Boys, I believe I've discovered a gold mine." (Bean 1978; 88; Caughey 1948: 8) News of the discovery, despite vain attempts to keep it quiet, spread from Sutter's Fort to San Francisco, and by May, 1848, gold fever became epidemic. "Within a short time nearly every town in California lost a majority of its population." (Bean 1978: 89-91) The San Francisco Californian of May 29, 1848, noted:

The whole country, from San Francisco to Los Angeles, and from sea shore to the base of the Sierra Nevada, resounds with the sordid cry of gold, GOLD, GOLD! while the field is left half-planted, the house half-built, and everything neglected but the manufacture of shovels and pickaxes.

The paper went on to announce it was folding up — its staff had left for the gold fields (Bean 1978: 91).

These "48ers" spread out in the foothills, usually after visiting Coloma and noting how similar it was to areas with which they were familiar. John Bidwell, early immigrant and founder of Chico, began mining on the Feather River near his ranch after a visit to the Coloma gold fields. By the summer of 1848, prospectors had begun to move up the American River and lower portions of its forks, and up the main channel of the Yuba as far as Foster's Bar (Coy 1948: 15). Early equipment was crude, but estimates of the year's production vary widely from as much as $48,000,000 to $245,301 (Clark 1970: 4; Coy 1948: 20-21). Actual output must have fallen somewhere in between, most likely at the lower end of the scale.

Word reached the eastern United States and Washington D. C. in September of 1848; President Polk excited the interest of prospective miners by announcing in December that "the accounts of the abundance of gold are of such an extraordinary character as would scarcely command belief were they not corroborated by the authentic reports of officers in the public service." (Bean 1978: 92) A tea caddy containing $3,000 worth of gold nuggets lent substance to the reports, which were judged to be high quality by the Treasury Department (Caughey 1970: 180).

There were three major routes to the mines taken by the flood of excited gold seekers starting in 1849; by sea, around Cape Horn or to Panama and across the Isthmus and on to San Francisco; or overland by way of the routes previously established by earlier immigrants. Routes were chosen by the Argonauts based on where they were starting from and how much money they possessed.

People on the eastern seaboard were most like to choose the ocean routes, because ships were available for the journey and because New England had years of experience in reaching California by sea. Merchant ships and whalers were refitted to carry passengers. "In nine months 549 vessels arrived at San Francisco, many of course from Europe, South American, Mexico and Hawaii but more than half from the Atlantic seaboard." (Caughey 1970: 180-181) The Cape Horn route was preferred in 1848, but because it took five to eight months for the trip, would-be miners focused on the Isthmus of Panama thereafter (Bean 1978: 93).

|

| MAIN ROUTES TO THE GOLD FIELDS |

The Panama route eventually became the fastest route to California before the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869, with scheduled runs from the east coast to the Atlantic side of Panama and from the Pacific side up to San Francisco. By 1850 the trip took six to eight weeks. However, the 49ers did not make the trip this fast — many got stuck in Panama awaiting passage on board passing ships. In 1848, "the average time from New York to San Francisco was three to five months" (Bean 1978: 93). It is estimated that 40,000 gold seekers used the Panama route during the height of the gold rush, 1849-1850 (Caughey 1970: 183).

The route taken by migrants from the midwest was overland. Those who came from Texas, Arkansas and other southern states usually chose the established routes to Santa Fe and then on through the Southwest, along the Gila River, across the Mojave Desert and on into southern California. Between 10,000 and 15,000 Argonauts chose this route (IBID: 183). Those leaving the northern portions of the midwest usually chose the California Trail, from St. Joseph, Independence, or Council Bluffs, up the Platte, through South Pass, and along the Humboldt River to the base of the Sierra Nevada, a route already well established by earlier immigrants and described by John C Fremont (Bean 1978: 94; Caughey 1970: 183; Egan 1977: 297-309). Once having reached the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada, immigrants had to choose either Carson Pass south of Lake Tahoe or Donner Pass. Many used Donner Pass, but a good number headed for Carson Pass because of settlements along the route and because Donner Pass had acquired a reputation of dangerousness after the experience of the Donner Party in 1846 (Bean 1978: 95). Independent traders located east of the crest sold goods at exhorbitant prices to exhausted and poorly supplied immigrants. One trader offered water to parched immigrants at $1.00 per gallon. In order to avert potential repetition of the Donner Party's tragedy, the state government sent out relief parties in 1849 under the command of Major Rucker and in 1850 under William Waldo of Sacramento (Caughey 1970: 186-187).

Immigrants traveling up the Truckee River and over Donner Pass noted some of the changes on the route. Journals described the conditions along the trail, difficult portions, and provided other information. E. Douglas Perkins, a 49er, made detailed notes on the leg of the trip from Donner Lake to Johnson's Ranch north of Sacramento:

The ascent of the pass from the Donner Cabins is about 5 miles, as the road was very winding in finding a passage through the trees and rocks. At 3 o'clock we arrived at the foot of a terrible passage over the backbone. The pass is through a slight depression in the mountains, about 1500 feet lower than the tops of the mountains in its immediate vicinity. As we came up to it, the appearance was like marching up to an immense wall, and the road goes up to its very base, before turning short to the right, and then ascends by a track in the side of the mountain, when about 1/3rd of the distance from the top, it turns left again, and goes directly over the summit. In the distance of about ½ mile, I judge this steep climb covers an elevation somewhere near 2000 feet. We rested ½ hour at the top, and went down into the valley to camp.

Once across Donner Pass, Perkins and his party passed a solitary peak ("Devil's Peak") and some small lakes, before turning down sharply into the valley of the South Fork of the Yuba. "Camp was down an almost perpendicular descent, where the wagons are let down with ropes, and the trees at the top are cut and marked deeply by the friction" (E. Douglas Perkins 1849: passim).

In 1852, Eliza Ann McCauley also described the route. Like earlier immigrants, crossing the pass and descending the western side required concerted effort:

September 16, 1852. This forenoon the road was very rough. In one place we had to let the wagons down by ropes over a smooth rock several yards long where cattle could not stand.

By 1852 there were trailside improvements:

September 18, 1852. We started down the valley (of the Bear River) passing a house on the way . . . it is three logs high, about six feet long, and four wide, one tier of clapboards, or shakes as they are called here, covering each side of the roof. Leaving this and passing through a gate we soon came to a cabin of larger dimensions.

This was the first house Eliza Ann saw in California.

September 19, 1852. We passed Mule Springs this morning. There are some mines at this place, also a tavern and a small ranch. About noon we arrived at Father's cabin . . . (McCauley 1852: 1)

Mule Springs was used in 1846 as a base of operations by rescuers of the Donner Party. East of Mule Springs travelers began to come upon mines, ranches, and other signs of permanent habitation.

The influx of gold seekers wrought great change in California. This is especially true for the gold mining areas. California's population climbed rapidly after 1848. It has been estimated that in February, 1848, there were 2,000 Americans in California; by December, 6,000; by July, 1849, 15,000; and by December, 1849, 53,000 (Shinn 1885: 125). In 1852 there were 100,000 miners in the gold country, and by spring of 1853 there were 300,000 people in the state (Shinn 1885: 125; Bean 1978: 100). Census records show that Nevada, Placer, and Sierra counties had a combined population of 35,107 in 1852 (U. S. Census 1850: 892).

Figure II - 1: Population by County.

| 1850* | 1860 | |

| Nevada | 20,583 | 10,933 |

| Placer | 10,783 | 5,670 |

| Sierra | 3,741 | 7,340 |

| *(Based on the State Census of 1852) (U. S. Census 1850: 982; U. S. Census 1860: 90) | ||

The population of the mining areas was quite mixed, and included U. S. citizens, Blacks, "mullattos," "Indians Domesticated," "Foreign Residents," and Chinese (U. S. Census 1850: 982); of these, white males made up by far the largest group; of the 35,107 counted in Placer, Nevada and Sierra counties, 22,680 (64.6%) were white males. There were comparatively few women, less than 4% in the three counties (U. S. Census 1850: 982). One observer noted that many of these were "neither maids, wives, or widows" (Paul 1947: 82). It has been estimated that four-fifths of the able-bodied men in California were in the gold fields or enroute to them in 1849 (Shinn 1885: 125).

The world-wide migration into California, as noted earlier, resulted in a diverse population within the area encompassed by the forest. There was a significant number of racial minorities; of these the Chinese were the most numerous within the region. Large numbers of Chinese were attracted to the gold fields of California with the same desires as the other gold seekers, the chance for wealth. In addition, the Tai-Ping Rebellion (1850-1864) in Kwantung Province provided a further impetus to migrants.

The announcement that gold had been discovered in California, that the passage was cheap, that indentured labor could be secured, and that Chinese merchants had already pioneered a settlement electrified the peasants and handicraftsmen who had begun to overcrowd the port cities of Canton, Macao, and Hong Kong. (Lyman 1974: 5)

The census lists 3,886 Chinese in Nevada County and 3,019 Chinese in Placer County in 1852 (U. S. Census 1850: 982).

Figure II - 2: Ethnicity ca. 1852*

| Whites | Chinese | Blacks | Foreign | Native Americans | |

| Nevada County | 13,368 | 3,886 | 103 | 782 | 3,226 |

| Placer County | 6,945 | 3,019 | 89 | 634 | 730 |

| Sierra County | 3,692 | ** | 49 | 1,067 | 0 |

| Totals | 24,005 | 6,905 | 241 | 2,483 | 3,956 |

| Statewide | 171,841 | ** | 2,206 | 54,803 | 31,266 |

| *Data from U. S. Census 1850: 982. **No figure given. | |||||

There were other minorities in the gold fields besides the Chinese. The census of 1852 listed 241 Blacks and "Mulattos," 3,956 "Indians Domesticated" and 2,483 "Foreign Residents" within Nevada, Placer, and Sierra counties (U. S. Census 1850: 982) Native Americans played an important and little acknowledged part in the earliest period of the gold rush. "To a remarkable extent California Indians participated in the gold rush as miners. One government report estimated in 1848 that more than half of the gold diggers in California mines were Indians" (Rawls 1976: 28). As the gold rush brought in ever increasing numbers of whites who resented Native American competition either as independent miners or as employees of whites, Native Americans were gradually forced out of the mines altogether in the early 1850s (Rawls 1976: 37-39).

In many cases foreigners received similar treatment. Anti-foreign feeling was common in 1849 and in the early 1850s, and focused on Latin Americans as well as the Chinese and Native Americans (Paul 1947: 111; Lyman 1974: 58). Taxes and intimidation were employed to drive out the foreign miners. In 1852, the state legislature enacted a "Foreign Miners' License Tax," largely as a means of forcing foreigners out of mining (Bean 1978: 141-143). This tax affected all foreign miners, but focused specifically on the Chinese. Anti-Chinese sentiment and propaganda dwelt on the "swarming" of Chinese miners over the gold fields. Chinese miners "were subjected to popular tribunals and mob violence" (Lyman 1974: 58-59). Early in the gold rush

at Marysville another miners' assembly declared that 'no Chinaman was thenceforth allowed to hold any mining claim in the neighborhood.' A movement to expel the Chinese from the area gained widespread support. Accompanied by a marching band and carnival atmosphere, white miner groups drove the Chinese from North Forks, Horseshoe Bar, and other neighboring camps. (IBID: 60)

With the increasing development of the mines arose the need for a commercial and transportation infrastructure to supply the mining areas. San Francisco, as a major port and point of disembarkation for those arriving in California via Cape Horn or Panama, rapidly grew into the state's largest and most important city (U. S. Census 1850: 982). Subsidiary centers like Sacramento, Stockton, and Marysville arose at convenient transshipment points for the mines on the major rivers.

Save for the overland caravans from Oregon, Mexico, and the Mississippi Valley, supplies and immigrants from the east and Europe usually were landed at San Francisco from ocean-going vessels, and there were transferred to river craft — light-draft steamboats and small sailing vessels — for reshipment to the three interior commercial cities of Sacramento, Stockton and Marysville. From those three points both goods and gold hunters had to travel overland for another fifteen to fifty miles before reaching their destination. (Paul 1947: 71)

From these cities people traveled by stagecoach, wagon, horse or one foot; goods were brought up to the mines by mule, ox team or packtrain (IBID: 71-72).

The Tahoe National Forest lies within the heart of the region many have called the "Northern Mines." "During the early days of the Gold Rush it became customary among miners to speak of districts tributary to Sacramento as the 'Northern Mines,' and those tributary to Stockton as the 'Southern Mines'" (IBID: 91). The former area included all or part of El Dorado, Amador, Placer, Nevada, Yuba, Sierra, Butte and Plumas counties (Paul 1947: 92; Bean 1978: map, 96). The Northern Mines differed from the Southern mines in several ways. First, the Northern Mines were rich in the Tertiary Gravels laid down by the ancient Sierra Nevada rivers and were sufficiently watered to be able to exploit them. The region also had extensive quartz lode deposits, and was more accessible to the commercial cities than the other mining regions. The Northern Mines had the largest population of any of California's mining areas, and had a high percentage of Americans because it was at the terminus of the overland trails and near Sutter's Fort. By contrast, the Southern Mines were drier, with shallow placers and some deep quartz deposits. Because they were located nearer the trail's end from Mexico, there was a higher concentration of Latino miners in the Southern Mines (Greever 1963: 45; Paul 1947: 108-109, 112-113). Of the two Sierra Nevada mining regions, the Northern Mines were the most productive, owing largely to the resources within the area and the fact that gold was available in large quantities in both placer and quartz deposits of great size.

The area that lies within the exterior boundaries of Tahoe National Forest is rich in natural resources and varied in topography. It contains foothills, mountain valleys, high peaks and deep canyons containing a variety of minerals, commercial lumber species, water resources, and agricultural areas. Largely ignored by the Spanish and Mexicans and an obstacle to pre-gold rush immigrants, the area quickly became a focus of population growth and mining industry after the discovery of gold in 1848. The development of resources within the Forest is the subject of the next chapters of this report.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/5/tahoe/history/chap2.htm Last Updated: 06-Aug-2010 |