|

History of Tahoe National Forest: 1840-1940 A Cultural Resources Overview History |

|

CHAPTER III

The Era of Individual Enterprise: Mining and Settlement on Tahoe National Forest Lands, 1848 - 1859

Introduction.

The decade 1848-1859 was a period of great change for California and for the lands within the Tahoe National Forest. During this interval between the discovery of gold in 1848 and the rush to the Washoe Mines in 1859, the California mining region was the focus of attention within the entire state, the United States, and around the world. Inrushing miners settled and mined on the lands within the Forest boundary, ending its isolation within the state and making it one of the most heavily populated of the mining areas.

Gold mining was the central economic enterprise within the state and Forest during this period. Other activities — logging, milling, agriculture, transportation — were adjuncts to mining and supported the mining industry. Non-mining enterprises usually depended upon miners as their customers.

The decade was also one of development within the mining industry. As readily available placers played out, miners developed new means to exploit less accessible deposits. Some of these changes were technological; others involved changing organizational and financial arrangements. New machinery and mining methods were introduced, most requiring greater capital outlay by miners and, eventually, by outside investors. While these investors were at first California residents, the changing nature and scale of mining soon began to attract capital from the eastern United States and Europe.

The period was also one of changing settlement patterns. The early years of the rush, typified by transitory mining camps and great fluidity of population, gave way to a much more settled and permanent pattern by 1858. The camps matured into towns, based on deep long lasting deposits or other resources, or location on a transportation link. By the end of the period virtually all of the major towns in the region that exist today had been established.

By 1859 most of the pieces of the more modern phase of development in the Forest were in place. New mining technology and investment of capital began to have a positive impact on production. The transportation system — roads, bridges, freight and express companies stagecoach lines, inns — was firmly established. Agriculture and logging, while still tied closely to mining, were beginning to find markets outside of the mining region. The result of the development was a change away from the "boom-bust" structure common to a mining frontier and the growth in its place of a more mature, stable economy and social structure not based on mining alone.

Gold Mining in Tahoe National Forest, 1848-1859.

Mining developed during this period from an individualistic, primitive form of industry into a system based increasingly on cooperation between groups of miners and finally to employment of miners by capitalists and mining companies. It was also during this period that mining-dependent industries like canal and flume organizations began their activities.

As noted above (Chapter II), miners began prospecting for gold away from Coloma soon after the discovery in January, 1848. Gold was found on other forks of the American River and into the hills around Iowa Hill and Yankee Jims that year (Coy 1948: 12-13). Through the summer of 1848 the forks and major tributaries of the American River were explored by a group of miners from Oregon. They found gold in varying amounts on almost every river bar they examined on the North and Middle forks (Thompson and West 1882: 68). The river bars were the focus of mining in the first years of the industry.

The word 'bar' in the camp's name was taken from the gravel deposit or gravel bar bank deposited on the sides of the river. These bars could be extensive in the case of a wide sweep of the river, but as a usual thing they were small and afforded the men of the gold days but little opportunity for city planning, if indeed there was enough room for the actual mining operations. Nevertheless, if a bar was sufficiently rich it quickly gathered its full share of miners with their hangers on, and an embryo city was soon started. (Coy 1948: 26)

Not only the bars on the forks of the American, but also along the Bear and Yuba rivers were being mined by 1850, and more were exploited as the population of the region grew.

The Yuba River, its forks and tributaries had a large number of active bars as early as 1849. On the North Fork of the Yuba bars near Downieville were mined in 1849, and on tributary streams such as Goodyears Creek, bars like Goodyears and Eureka North were located at the same time. "Along the North Fork were Monte Cristo, Fur-Cap Diggings, Rattlesnake Diggings, while on its eastern banks were Graycraft Diggings and the Empire Mine" (IBID: 67). Bars were also located and claims staked out on the Middle and South forks of the Yuba between 1849 and 1850. The Yuba system was dotted with bars; one source counted fifty-one between Marysville and Downieville alone (Wiltsee 1931: 2).

As the gold rush continued to grow, the American River system was an expanding area for mining of bars. One historian has stated that at least 1,500 men were mining river bars on the Middle Fork above the junction with the North Fork near Auburn in 1850. Over the years following:

The amount of gold taken from those river bars was very great. Estimates of returns from the leading bars on the Middle Fork of the American River place this amount at nearly $17,000,000. Among the chief contributors were American Bar, $3,000,000; Mud Canyon, $3,000,000; Horseshoe Bend, $2,500,000; Volcano Bar, $1,500,000; Greenhorn Slide and Yankee Slide, $1,000,000 each. (Coy 1948: 37)

Of these, Horseshoe Bar, Volcano Bar, and Mud Canyon were probably on or within the boundaries of Tahoe National Forest (USFS Tahoe National Forest Map, 1977). The North Fork of the American also had a great many bars, including "Calf, Kelley's, Rich, Jones, Barne's, Mineral, Pickering, Euchre, and a score of other(s)" (Coy 1948: 37). Euchre Bar is in the Forest.

Although the North Fork of the American was less productive of gold than the Middle Fork or South Fork, it is not safe to assume that the region north of the Middle Fork was not rich in gold. For here were to be found the very productive mines of which Forest Hill, Michigan Bluff, Yankee Jim's and Iowa Hill were representative names. These were not river mines but located upon the divides between the river channels. (IBID: 38)

Placer gold in river bars was the first form of gold exploited, yet early on miners noticed placer deposits away from the river canyons. One authority states: "While the earliest diggings had been river claims, the men of 1848 and 1849 soon discovered that gold bearing gravel was to be found in the ravines and other places removed from the present river channels" (Coy 1948: 29). Some early mining was done by crevassing — digging out nuggets caught in cracks in the bedrock. This was true along the Middle Fork of the American River (Thompson and West 1882: 69) Gold bearing claims away from available water supplies became known as "dry diggings" (Coy 1948: 29). One reason for increasing prospecting was the fact that as more miners arrived in 1849 and 1850, yields per miner decreased.

Another means of dealing with increased competition and decreasing returns was to improve mining methods (Paul 1947: 56-58). The earliest equipment used in placer mining in California was the pan, pick, and shovel (Wiltsee 1931: 3). Miners dug up gold bearing dirt and washed it in the pan in a swirling motion used to remove dirt and small rocks. Heavier than almost any other object in the dirt, gold particles would gradually be deposited on the bottom of the pan (Bean 1978: 97). This system was suited for the solitary miner; it was also physically demanding and tedious. A standard pan, if such existed, was

. . . about 10 inches in diameter at the bottom, 16 inches at the top with a depth of about 2-1/4 inches. Usually a heavy iron wire rim strengthened the top of the pan. In the rush to find equipment suitable for washing gold, any kind of bowl or basin was brought into use, even wooden bowls and Indian baskets found their place. (Coy 1948: 97)

Gold would be separated from the other heavy objects and "black sand" at first by drying and blowing away particles, and later by the introduction and use of mercury, to which gold adheres and forms an amalgam (Paul 1947: 58). Pans were used continuously throughout much of the gold mining era, often as the final step in washing gold after the pay dirt was processed by other systems.

Greater efficiency in washing gold bearing dirt would increase yields, and miners were quick to introduce new means of placering. In 1848 the "rocker" or "cradle" came into use; most likely it was first employed by miners with previous experience in Mexico or Georgia (IBID: 52-3; Coy 1948: 98). The rocker washed gravel on a perforated plate. Larger rocks and clumps of earth would be removed or broken, and the finer particles allowed to pass through and fall on a second level, where the heavier pieces of gold would be caught behind cleats on a board or cloth in the bottom. The water was allowed to pour out on the ground. The rocker was designed to be rocked from side to side in order to speed the washing process. Water would be dipped and poured into the hopper continuously to wash out the dirt. Pans would sometimes be used to wash the material caught in the rocker. The use of a rocker was possible by one man, but much greater efficiency was achieved if two or three miners were involved, one digging and one or two dipping and washing (Wiltsee 1931: 3-4). Examples of rockers are common in California museums. Some are quite elaborate.

The fact that the rocker was most efficient when used by teams of miners led to important changes in the organization of work. Each technological or methodological advance after the introduction of the rocker required greater cooperation by groups of miners. The lone miner with his pick and pan, then, employed the shortest-lived single mining method and occupies a disproportionally large place in the public image of the gold rush.

The invention of the rocker was followed by two innovations that were refinements on its basic principle, and were among the first "Californian" contributions to gold mining technologies in their modern form. The first of these was the "long tom," essentially a short washing sluice with a perforated iron plate at the lower end, and an undercurrent sluice to catch finer particles (Wiltsee 1931: 4). Most were shaped like an inverted funnel, so that when water and gravel were mixed at the narrow end a greater force of water could be employed; the wider lower end would reduce the force and catch smaller pieces of gold before the stream of water and dirt reached the under-current sluice (Paul 1947: 61-62). Like the rocker, usually three or more men used a long tom in concert. It differed from a rocker in that it remained stationary and water flowed through it continuously, replacing the rocking motion of the rocker. Mercury would be placed in the lower end and undercurrent sluice to adhere to fine gold particles (Wiltsee 1931: 4). The long tom allowed for a much greater amount of gravel to be processed per miner per day.

Another placer invention was the sluice box. These were similar to long toms in construction, except they did not flare widely at the end; rather they were usually built to uniform size so that they could be connected end to end in long strings. Some sluice systems were hundreds of feet long and required large groups of miners (Coy 1948: 100; Wiltsee 1931: 4).

Long toms and sluices required a plentiful and constant supply of water in order to operate. They were, naturally, used at first along rivers. It was clear, however, that gold bearing gravels were located in places throughout the gold country away from water supplies. It was this requirement for water to work "dry diggings" that brought another of the important changes in California placer mining after 1850.

The miners who arrived during the 1848-1850 rush shared a common experience in the mines. Most were inexperienced in gold mining, and were usually faced with learning how to mine and finding a claim to work at the same time (Coy 1948: 92). A 49er, James P. C. Allsopp, described his fellow Argonauts as

. . . almost to a man young and hearty, and they had the digestive power of the ostrich. A man of 30 was considered middle aged, and if he had attained the mature period of 35, why he was looked upon as a patriarch, a veritable Nestor among the young bloods. (Allsopp 1881: 45)

Miners usually worked with partners, or in small companies of three to six men in the early years of the rush. These early miners (1848-1850) erected crude shelters, often of brush with a canvas top, or of logs with a tent-like roof. In 1848 it was thought that mining would be a seasonal, summer activity; it soon became apparent that winter rains would provide more abundant supplies of water to work claims and thus cabins or somewhat more permanent accommodations would be necessary to protect miners from the elements (Wiltsee 1931: 7).

Miners usually worked six days a week, with Sunday off for rest and recuperation. Clothes were washed, cabins repaired, trading posts or stores in local camps visited and other domestic activities pursued. If available, newspapers, letters, and books were read. Friends in nearby camps might be visited. Of course, less wholesome diversions were also available, and drinking, gambling, horse racing and various sports were popular diversions. Miners might also attend meetings of their mining district (Wiltsee 1931: 8).

In an article looking back at the 49ers, the Nevada City Transcript discussed the "genuine article," the true California miner.

(He) . . . feels thoroughly equipped . . . if he possesses a slab of bacon, a few lbs of flour, a little sugar, coffee, tobacco, and an old pick and shovel. If he has a pack animal, all right; if he hasn't, all the same. And thus outfitted he scales the mountains, swims the rivers, and skims the plains for months, happy as a stuffed goat.

Among the other items in his baggage might be a frying pan, butcher knife, and some spirits (Nevada City Transcript 3-30-1882).

Prospecting for a claim was hard work and paid nothing, and the time and expense of prospecting was a major source of complaint among the early miners, especially as the process might take weeks (Wiltsee 1931: 12). Naturally then, word of a rich find might attract a large number of miners to an area overnight. At "Bird's Store" (Byrds Valley) just west of Michigan Bluff, two men began mining in the winter of 1849-1850. By February the word about their successful claim was out and "the men came in hundreds, making Bird's Store their place of rendezvous, until the number of men gathered there amounted to two or three thousand" by early spring (Thompson and West 1882: 68-69). Other areas in the Forest were first prospected and mined after similar early discoveries and "mini-rushes." The result was a highly mobile mining population and an extraordinarily large number of temporary settlements.

Fairly early in the mining era miners along the rivers began to exploit more than the riparian bars that attracted their initial interest. They began to mine the river bottoms themselves. Streams were diverted into flumes and the exposed bed mined with conventional placer equipment, crude "Chinese" pumps being used to keep the workings reasonably dry. Other miners built wing dams and mined the river one half at a time. Chinese miners were known for being adept at river mining and wing dam construction (Williams 1930: 56). River mining was responsible for a large portion of the state's output, and all rivers in the state were mined through the 1860s (Clark 1970: 7). A newspaper noted in August, 1853, that "the North Fork of the Middle Fork (of the American River) is flumed from the junction to El Dorado Canyon" (Thompson and West 1882: 226).

The changing placer technologies continued to expand the use of associated labor. River mining required a great deal of teamwork, as well as capital to develop such claims. River mining then, necessitated a change from individual mining or mining in partnership with others, to a more "capitalistic," investor oriented form of mining. To be sure, many of the river bed mines initially were built by groups of miners in partnership. Nevertheless, investors from mining towns, San Francisco and elsewhere began to enter the gold industry by investing in river mining (Paul 1947: 116).

|

| THE MINER'S SUNDAY. (Rotter: 1979, 13a) |

More and more interest was also expressed in claims located away from available water supplies. To work these claims water had to be brought to them. In addition, long toms and sluices required a continuous flow of water to operate; large delivery systems had to be built to supply water to these claims. "Water in many of the California diggings was scarce; 'fluming' companies were organized to bring water from a distance, and the cost was high" and when water "had to be brought a considerable distance only men with capital at their command could do it" (Rowe 1974: 110-111). The San Francisco Alta wrote about this transition in February, 1851.

. . . The real truth is, by far the largest part of the gold . . . (mined hitherto) was taken from the river banks, with comparatively little labor. There is gold still in those banks, but they will never yield as they have yielded. The cream of the gulches, whereever water could be got, has also been taken off. We now have the river bottoms and the quartz veins; but to get the gold from them we must employ gold. The man who lives upon his labor from day to day, must hereafter be employed by the man who has in his possession accumulated labor, or money, the representative of labor. (Quoted in Paul 1947: 116)

|

| A SUNDAY'S AMUSEMENTS (Rolle 1978: 204) |

Gold mining then was beginning its industrial phase, in which large scale engineering operations, machinery, and the skills to run them were needed (IBID: 116). The individual miner with his pick and shovel gave way to the miner as wage earner.

New sorts of mines were developed as conditions, exploitation and development of resources allowed. Among these were coyote holes and drift mines, which worked the Tertiary Gravels; ground sluicing and hydraulic mining, which also exploited the deep gravels; and quartz lode mines. All of these mining methods were used in the 1850s in the Forest, although some of the techniques were abandoned in favor of more efficient methods. To a greater or lesser extent, all required a more advanced industrial system to operate successfully.

Coyote holes and ground sluicing were the forerunners of the two important placer mining systems, drift mining and hydraulicking. A coyote hole was simply a shaft sunk into the ground to get at gold bearing gravels beneath the surface. "In 1849, the miners in the dry diggins at Nevada (City) would sink shafts to the depth of fifteen or twenty feet to the bedrock, and then, rather than throw off the whole surface, would 'coyote,' as it was called, from the bottom of their excavation, and this was the beginning of drift mining" (Thompson and West 1882: 192). Coyote hole diggings led to the discovery of the great Tertiary Gravel deposits (Pagenhart 1969: 86).

Drift mining was an outgrowth of coyote holes. Miners following the course of the gravels would tunnel into the hillsides. "When the gravel is thus reached it is mined out, the process being called 'drifting,' the superincumbant mass being held in place by timbers held beneath" (Thompson and West 1882: 192). Drift mines have been among the most productive in the state. In Placer County "this branch of mining is most extensively prosecuted in the region lying between the North and Middle Forks of the American River, commonly designated as the 'Divide,' the gravel or mining area comprising about 250 square miles." The area was prospected in 1849, and the exploitation of the deep gravel deposits by drift tunnels began in earnest in 1853. Drift mining went on it a variety of other locations within the Forest, including Damascus in Placer County and Monte Cristo, Forest City and Alleghany in Sierra County (Thompson and West 1882: 192, 377; Sinnott 1976: 190; Clark 1970: 19; Stevens 1969: 2) Water was required to wash the gravels once mined. This was sometimes available within the mine itself as aquifers were drained by tunneling; if not, water companies brought water to the mine (Thompson and West 1882: 192).

Coyote holes and drift mines exploited gravels that were either shallow and rich, or so deeply buried that other methods could not be used to reach them. Gravels located near the surface or overburdened by relatively loose material were exposed and developed by means of the direct application of water to the claim. In the first years of the gold industry "ground sluicing" was practiced. Simply stated, a ditch of water would be directed on to a placer deposit, thereby washing the gold from the gravel as the overburden was stripped away (Pagenhart 1969: 88).

. . . To make use of this technique, the miner dug a small gully down the hillside that he intended to wash. He then had a supply ditch or flume extended to the top of his hill, and presently he would send water cascading down the gully. Trusting rocks and other obstructions to serve as natural riffles, the miner would then stand on the bank of his artificial watercourse and shovel and thrust masses of earth down into it. At intervals of a few weeks or months he would use a long tom or board sluice to 'clean up' the fine debris that had accumulated behind the obstructions in the gully . . . The ground sluice undoubtedly lost a good proportion of the gold that passed through it. (Paul 1947: 151-152)

Miners quickly began to refine the ground sluicing method. In the spring of 1852, a miner named Anthony (sometimes Antoine) Chabot attached a canvas hose to the head of the flume bringing water to his claim on Buckeye Hill east of Nevada City to more efficiently apply the water to his ground sluicing site. In March a miner nearby on American Hill, Edward Matteson, attached a nozzle to the canvas hose to better direct the water and increase its force. These two men are credited with the invention of hydraulic mining. "Given water, ground, drainage, and the proper equipment, one man could do in a day what dozens could hardly do in weeks" (Kelley 1959: 26-28). Buckeye Ridge and Diggings are within the Forest (T16N/R10E, MDM, sections 16, 17, 18, 19, 12) (USFS Tahoe National Forest Map 1977).

During the years 1853-1859 hydraulic mining underwent a series of important innovations. Canvas hose was quickly replaced by iron pipe, and improved nozzles (monitors) allowed water to be diverted under great pressure. Pipes and monitors were manufactured in Marysville and San Francisco (Pagenhart 1969: 101-103). Other innovations after 1859 were of great importance to this kind of mining and will be discussed in Chapter IV. Hydraulic mining rapidly replaced coyote holing, ground sluicing and drift mining wherever it could be effectively applied, mostly because it required far fewer miners to develop very large claims. Drift mining continued in those places were the overburden was too dense or too deep for hydraulic operations. Hydraulicking was widespread within the Forest, and was often carried on alongside or nearby drift and quartz mines. Hydraulic mines were located from Michigan Bluff in the south of the Forest, to Alpha, Omega, and North Bloomfield in the central portion, to Brandy City, Eureka North, Poker Flat and Morristown in the northern portion. All of these hydraulic mining towns were located on the Tertiary Gravels of the Ancient Yuba River (Coy 1949: 38,63).

The major limitation to the spread of placer mining in general and hydraulic mining in particular was the availability of water to work the claims. Pans and cradles required relatively little water to operate, and were usually employed in riparian settings. Long toms, sluice boxes and hydraulic systems required ever-increasing amounts.

As early as the spring of 1850 ditches were dug along Deer Creek near Nevada City with the capacity to supply seventy to ninety gallons per minute to long toms used nearby (Pagenhart 1969: 85). Miners began to recognize that selling water could be as lucrative as mining. Such development proceeded rapidly during the 1850s.

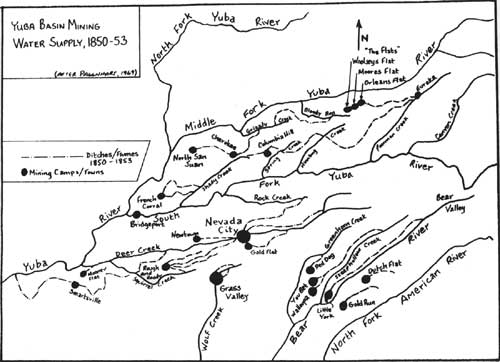

The early (water) companies had no storage facilities and tapped streams and ravines which had so little water in summer that mining had to be shut down. During the three-year period of 1850 to 1853, before the demands of hydraulicking were made, ditches and canals were dug to serve shallow placers which were not expected to be of more than short duration. Nevertheless, by 1853 the major outlines of the water conveyance system visible [in the Yuba Basin] today had already been indicated. The volume and head of water needed had led several of the early companies to build ditches far up into the rugged ridge and valley region, adjoining the Sierra crest. (Pagenhart 1969: 89)

|

|

YUBA BASIN MINING WATER SUPPLY, 1850-53 (click on image for a PDF version) |

The ditches mentioned here were built within or near the forest (see map, page 32). Between 1850 and 1853 ditches were built or being constructed for use by long toms and sluices from Eureka (Graniteville) on Poormans Creek to Orleans, Moores, and Woolsey's flats (later known as the "Flats"); from Bloody Run to Grizzly Creek and on to Cherokee; from Cherokee to North San Juan; from Humbug Creek to Columbia Hill; from Steephollow Creek to Walloupa and You Bet; and from Greenhorn Creek to Red Dog. These systems were in Nevada County. In 1852 Placer County listed $1,427,567 invested in ditches and mining equipment. Of this, $858,037 was invested in river mining; $556,000 was in ditches and water conveyance systems (Thompson and West 1882: 145). By 1854, water companies were serving claims in Placer, Sierra and other counties within the Forest. The Sacramento Daily Union of December 7, 1854 listed over seventeen ditch companies in Sierra County and described their ditches, located from Gibsonville to Eureka Diggings. The ditches varied in length from two to eleven miles. The Placer County Assessor's Report of 1855 listed a number of canal companies, including the El Dorado Water Company. This organization, with offices in Michigan City (Bluff), had offered $60,000 in capital stock and controlled canals and laterals totaling thirty miles in length (Thompson and West 1882: 151).

A large number of ditches served the area around Downieville in 1854. Havens and Cracroft [sic], whose water source was Pauley Creek, had an aqueduct over the North Fork of the North Fork of the Yuba sixty feet high which also served as a bridge for footmen and packtrains, and cost $9,000. The Wisconsin Ditch, which drew from the "Middle Fork" crossed the river to Natchez Flat by means of a suspended hose. It was two miles long, cost $4,000, and paid for itself in eight weeks. The Minnesota Ditch drew water from Wolf Creek and supplied Minnesota, a town of 2,000 in 1854. The ditch cost $75,000 and was eleven miles long. There were approximately fifty other small ditches and water companies in the area (Sacramento Daily Union 12-14-1854). Hydraulic mining was being utilized by this time, but was not yet fully developed. These ditches and flumes were built to supply long tom and sluice claims. While costly, the returns were sufficiently large to attract a large number of canal builders.

Miners who needed water organized the first water companies and built the initial delivery systems. They formed joint stock companies, to which local merchants often subscribed (Paul 1947: 64). As miners became more experienced in water system construction, some began to move away from mining itself and into the business of providing water to the mines. Three miners, Spencer, Rich, and Fordyce, combined to build a canal from Upper Deer Creek into Nevada City in 1853-54. Rich and Fordyce surveyed the upper reaches of the South Fork of the Yuba River looking for diversion sites and securing water rights. They merged in 1855 with other early Nevada City water companies and formed the "Rock Creek, Deer Creek, and South Yuba Water Company," which over a period of years became the South Yuba Canal Company. The last of the pre-hydraulic mining ditches built in the Nevada County portion of the forest were the Poorman Creek Ditch (from Poorman Creek to Eureka and Moores Flat), and the Irwin Ditch (from Poorman Creek to Relief Hill and Humbug Creek) under construction since 1851 (Pagenhart 1969: 99, 119).

Hydraulic mining became widespread after 1854-1855, and water companies within the hydraulic mining region quickly realized that the systems built for long toms and sluices would not be adequate for hydraulicking.

In the early mining days, operations were often completely suspended during unseasonal droughts The economics of later corporate enterprise, however, made intolerable such unreliable water supplies, and was the main reason for the early construction of headwaters storage dams. Storage facilities had to be planned for a possible extension of the regular summer drought well into winter. (IBID: 75)

While much of the development of large storage facilities occurred at a later period (after 1860), in the 1850s a number of ditch head diversion dams developed into storage dams. As early as 1850 rock and flashboard barriers were built across the outlets of White Rock and Upper Peak lakes. In 1855 several other small high Sierra Nevada lakes were enlarged this way. Between 1855 and 1865, twelve such enlargements took place. One of the most famous of these, Rudyard (or English) Dam, was built in 1858 at the headwaters of the Middle Yuba River, using dry-laid stones with a board facing (IBID: 113).

Such large projects were costly and required large amounts of capital for construction and operation. Common problems facing canal and ditch companies were high prices for labor, small gold deposits, strikes by miners over high water prices, and bankruptcies. The Sierra Nevada Lake Company built in 1858 a $1,000,000 ditch and dam system to supply Alleghany and Minnesota, only to discover that the deposits were too deeply overburdened to be effectively mined by hydraulicking. As hydraulic mining increased only those systems that had built the largest of canals could meet the demands placed on them by hydraulickers (IBID: 114-115).

The size and complexity of mining claims grew during the 1850s. The original system adopted ad hoc by the 48ers and 49ers allowed for one claim for each miner, normally thirty by thirty feet. Size of claims varied by district and were determined by local miner's associations. As mining became more advanced, and requirements for capital grew, the small claim rules were too inefficient. Thus during the 1850s the rules were relaxed to allow for larger claims able to support the expensive mining operations working them. In 1852, around North San Juan larger claims were voted in, and after 1854 rules were changed to allow one miner to own more than one claim (IBID: 109-110). By 1854, claims along the Downie River were increased to 100 feet along the river and 200 feet into the hillside; claims along Pauley Creek were 100 feet along the stream and extended to "30 feet above low water mark" (Sierra Citizen, 12/13/1854). Although larger, the 100 foot limit on these claims still allowed each mile of river to accommodate many miners.

To summarize, between 1848 and 1858, about ninety percent of the gold mined in California was from placers (Sinnott 1981: 7). The early forms — pans, rockers, and so on — gradually developed into more efficient sluicing systems used or adapted by all placer mining operations. By 1855-56 river mining reached its peak; white miners got out in 1859 and by 1863 Chinese miners were virtually the only ones left using that system (Paul 1947: 129-130). Water systems developed for long tom and sluice claims were slowly adapted in the mid-50s for the demands of hydraulic mines. Placer mining, by 1859, required capital, skills beyond those known by the 49ers, and enormous amounts of water.

In California, quartz lode mining was a less important mining technique than placer mining until after the discovery and development of the Washoe mines in Nevada in the late 1850s. Nevertheless, quartz lode mining began in California during this early period, and the techniques discovered were important to the industrial development of the quartz mines in northern California.

Quartz lode mining began in Mariposa in 1849, largely by "amateurs" with no knowledge of the requirements, techniques, or geology of the region. The system quickly attracted investors.

. . . The rush of capital into the gold diggings began. From speculating in grandiose trading schemes in California, the investing public began investing in quartz-mines, undeterred by the bruises and shocks it had sustained by over-sanguine ventures in previous schemes bearing the glittering name — California. Eager and gullible speculators were easily found by 'Californian' company promoters in London as well as in Boston and New York, although many of the concerns were genuine enough . . . The first quartz mining ventures in California met with very mixed success. Many early companies had far more capital than financial management or technical skill. (Rowe 1974: 112)

The failures in early quartz mining raised the suspicions of prospective investors and hindered quartz mining development for several years after 1853 (Paul 1947: 130-131).

Quartz mining required three separate steps. First, ore had to be mined from the earth. Next, it had to be separated and pulverized to release the gold ores. Last, gold had to be separated from the surrounding material and treated to remove impurities. Simple stamp mills were developed in 1849-1851 that could pulverize gold bearing quartz. Other mines continued to use the arrastre, a system by which ore was crushed by placing it beneath a series of moving rocks chained to an arm swung by a mule or other draft animal. Arrastres were used before stamp mills and alongside them after the mills were improved later in the period. By 1856 a complete mill could be purchased for six to ten thousand dollars (Paul 1947: 132-138). However, once gold ores were separated from the other material, a new problem was discovered. When mercury was added to form an amalgam, it failed to adhere to the gold. This was because the gold was in the quartz in a different form: sulphurets. A new process had to be developed to remove the gold from the sulphurets. This process, chlorination, was introduced into California in 1858, and the combination of improved mining skills, stamp mills, and chlorination led to a revival of interest in quartz mining. In 1854, there were thirty-nine successful quartz mines in the state. After 1856, the numbers increased so that by 1858 there were an estimated 279 (IBID: 141-144).

Within or near the area of the Forest were a number of early quartz mines. In 1852, Placer County listed $13,530 invested in quartz mining; by 1855, two quartz mills were described as operating in Humbug Canyon and Sarahville (near Michigan Bluff) operated by Strong and Company and Hancock and Watson, respectively. Strong's mill was the "first successful quartz mill" in the county (Thompson and West 1882: 145, 151). By 1856, quartz mining in the county developed further.

There are four quartz mills in successful operation in this county. One of them is situated at Grand Ledge on Humbug Canon, eight miles east of Iowa Hill. It has a sixty-horsepower engine, working twenty-four stamps, and capable of crushing fifty tons of quartz in twenty-four hours. This mill is under the management of Dr. McMurtry . . . the quartz mill of Watson and Co., situated at Sarahville . . . is paying handsomely. (IBID: 223-224)

Nevada County quartz mines were centered around Grass Valley and Nevada City, to the west of the Forest boundary. Sierra County had extensive quartz deposits. One of the most famous was located at the Sierra Buttes. The ledge was located in 1850 and worked continuously thereafter (Fariss and Smith 1882: 481). Quartz mines were also located at Forest City, Alleghany, and other areas within the county (Stevens 1969: 2; Clark 1970: 19).

The man responsible for much of the early development of the quartz mines at Sierra Buttes was Solomon Wood. He had placer mined at Downieville between 1848 and 1850; after a trip to the east he was part of a rush in the spring of 1852 to the quartz lodes at the Buttes. Wood secured an interest in the Ariel Mine and Plumas - Eureka Mine near Johnsville, and bought up all the available claims around the Ariel. By 1853, he was the sole owner of the ledge, and had Mexican laborers crushing ore in arrastres while waiting for his stamp mills to be built. He called the mine the Telegraph. In 1857 he sold it to the Reis Brothers who renamed it the Sierra Buttes Mine. This mine, along with the Plumas-Eureka, was one of the original important quartz mines in the state. Wood is interesting also because he was involved in a variety of other mines in the Forest, including the Live Yankee at Forest City, the Four Hills mine near Gold Valley, and the True Fissure near Gold Lake (Sinnott 1976: 217).

By 1858, there were seven quartz mills in Sierra County, worth $56,000 and which had crushed 12,500 tons of quartz. One of these was an eight-stamp mill near Chips Flat (Fariss and Smith 1882: 482-483). Clearly quartz mining did not rival placer mining operations in the 1850s, but the processes had been developed that would result in quartz mining becoming the most productive and longest lasting major gold mining industry later in the century.

Thus, California gold mining developed considerably during the period 1848-1859. The process went from an individual and cooperative enterprise to an industrial form requiring gold to mine gold. Primitive placer mining technologies had become greatly refined, and deep quartz deposits began to be exploited. The scene was set for the next phase in mining in California and the Forest, during which hydraulic mining and drift and quartz tunnels would become completely industrialized. Deep, extensive deposits would be exploited over a long period of time using the basic methods and techniques discovered during this earlier period. The more stable, mature mining system of the years after 1859 resulted in a more settled pattern of community development and an increased exploitation of timber and agricultural resources.

Mining Settlement and Community Development.

Settlement on the Tahoe National Forest was, during the years 1848-1859 tied closely to the advance and maturation of the mining industry. The early transitory settlements, characterized by impermanent mining camps, were replaced by towns whose existence was based on deep, long lasting gold deposits, or proximity to an important transportation route, or development and use of other resources needed by the mining industry. The pattern of settlement set down during this period has largely remained to the present day, with only the most important settlements lasting past 1859.

The Native Americans were among the first to feel the impact of the invasion of miners into their area. The initial affects of the gold rush on the Native American population resulted in changes in village sites and village extinction. Village locations were changed because of exploitation of the Indians and their lands; extinction was often the result of "wars" and homicide. After the United States claimed possession of California, Native Americans were often relocated so that their land could be made available to Anglo settlers (Heizer 1978: 65). The Anglo period in California was characterized by the introduction of whites seeking available land and the intense exploitation of natural resources. While the Spanish and, to an extent, the Mexicans tried to integrate Native Americans into their society and culture, Americans in general had no place for them except insofar as they performed as white men (IBID 1978: 107).

While some Native Americans mined early in the gold rush, they were gradually forced out of mining and the mining region (Rawls 1976: 37-39). The process of removal was often brutal. During and after 1849 the actions of whites against Native Americans consisted in general of widespread personal combat between individuals and small groups (Heizer 1978: 107).

The primary factor for genocidal activity toward Indians has always been the Indian land. The gold miners found the Indian to be an obstacle in his search for precious metal; much of the prime territory was on Indian land. The ranchers and farmers coveted this same land area, and timbermen recognized the value of Indian timberland. (Coffer 1977: 14)

The Native Americans living within the Tahoe National Forest west of the Sierra Nevada crest, and thus most impacted by the gold rush migration, were the Nisenan or Southern Maidu (Heizer 1978: 387). They apparently had had little contact with whites during the Spanish and Mexican periods, and received into their area escaped mission Indians and Miwoks from the area to the south. They apparently had some brief contact with Hudson's Bay trappers in the valley in the 1820s. In 1833, about seventy-five percent of the Nisenan in the Central Valley portion of their territory died during a malaria epidemic; those in the foothills were little affected by this or the immigrants passing through their lands in the 1840s (IBID: 396). Fremont's men hunted the Maidu mercilessly in 1846, and caused great destruction and death among the tribes living near the Sacramento River (Egan 1977: 339-340).

With the discovery of gold the fate of the Maidu in the foothills was sealed, and the area they lived in overrun. Widespread killing, destruction of villages, and persecution of the tribe quickly destroyed them as a viable culture. The surviving Nisenan lived at the margins of the foothill towns and found work in agriculture, logging, ranching, and domestic activities (Heizer 1978: 396).

The miners of 1848 and 1849 settled in the river valleys and along rich placer bars. Since the United States had just acquired the territory through war with Mexico, civil authority lagged behind the population explosion caused by the rush of miners.

Because the mining camps had sprung up beyond the reach of any established law, they had to adopt their own regulations. Practically none of the land had passed into private hands, and the rights of the Indians were ignored . . . there was no Federal mining law that would have been relevent to the California mining camps, because no precious metal had ever been discovered before on public lands in the United States. (Bean 1978: 99)

To fill the legal vacuum miners acted on their own to devise practical mining laws to provide a measure of law and order. Each camp, district, or mining area would hold a meeting to organize an "official mining district," elect officers, and write regulations. There were over 500 such districts in the Mother Lode region, and the laws and rules they produced drew heavily on the experience of Spanish, Cornish, Mexican, and English mining law as well as common sense. The size of claims was established as well as a rule that they be worked more or less continually for them to be held. Each district appointed a register of claims or secretary to keep a record of the use and location of claims to ajudicate disputes among miners. Less attractive were the provisions or clauses that sometimes excluded Asians, Latinos, or others (Bean 1978: 99). Miners formed districts within the National Forest around all the major early mining areas.

As elsewhere, mining camps in the Forest were, above all, temporary. Early structures were often of the rudest sort, sometimes nothing more than a brush wall with a canvas cover, or a simple tent. Early camps were built on hilly rather than mountainous terrain, but as mining spread into the mountains, camps were located at the bottom of steep canyons (Paul 1947: 79). Access was a problem for many camps.

At some (camps), the steepness of the surrounding ridges was so great that the rays of the sun never touched the community during the winter months. At others, access to the camps was possible only by roads so abrupt that the approaching traveler found himself beginning the last stage of his journey from a point almost directly above his destination. (IBID: 79)

Camps were often thrown up with no sense of a plan. However, most mining camps and later towns, shared some common features. Most had a similar spatial distribution and the structures in them spread out along a "Main" street, with laterals depending on the town and the length it survived. Most buildings had a wooden frame, plank floors and canvas serving as wall and roof. "Unfortunately for the safety of the populace, construction costs were so high and men's impatience so great that until late in the fifties the majority of houses, whether in city, town or camp, continued to be built chiefly of wood and canvas" (IBID: 75). After 1858, in Sierra County, frame buildings became common in larger towns (White 1961: 79). While most miners continued to live in "temporary" tents and "plank hovels," gradually log or plank sided cabins became more common in the 1850s. These usually had canvas roofs and a stone chimney (Paul 1947: 75). Examples of such structures are exceedingly rare.

Because of the materials and methods used in constructing these buildings, most camps were visited by devastating fires. Forest City, for example, was burned in 1858 (Stevens 1969: 1). In the modern towns that have survived to the present day only those buildings constructed of brick or stone date back to the 1850s. The others are gone and have been replaced by later structures.

|

| A DAILY PLEASURE (Rolle 1978: 206) |

Thus, a few if any, of the surviving towns have retained their original arrangement of buildings or architecture.

Mining camps contained a variety of businesses. Stores sold supplies to the miners and it became apparent to many that supplying the mines could be more lucrative than mining. Major William Downie, founder of Downieville, kept a store there (Sinnott I 1972: 6). Leland Stanford, who was later involved with the building of the Central Pacific Railroad and who became governor of California, owned a store in Michigan Bluff in 1855 where he sold oil and groceries (Kraus 1969: 14). Another common structure was the boarding house. These were often operated by the few miners' wives in the camps.

When a miner's wife arrived at a mining camp she found that she was one of several women in a camp of hundreds of men. Immediately she was compelled by popular demand to become an entrepeneur by running a boarding house . . . these hardy women . . . had to cook, serve, and clean up after crowds of men in the boarding houses. It was a profitable business, more reliable and renumerative, in many cases, than panning gold in the streams. (Woyski 1981: 45)

|

| OCCUPATION FOR RAINY DAYS (Rolle 1978: 204) |

The scarcity of women in the camps forced men to assume traditional female roles — cooking, washing clothes, and sewing. Gradually some boarding houses evolved into hotels, often ambitiously named "Empire," "Palace," or "Hotel De Paris" (Fatout 1969: 4).

Saloons were an important social center in mining camps.

Especially in the early days, the saloon was the frontier's most versatile social institution. It served as a place to sleep, a clearinghouse of communication, a location of limited banking facilities, and a site for church services and political discussion. Above all, the saloon was a place for entertainment and relaxation, with facilities for gambling, dancing, conversation, and companionship as well as drinking. (Blackburn 1980: 447)

Early saloons were nothing more than a tent with a rough bar, glasses and whiskey barrel. "As the town developed so did the saloon to perhaps a large tent or a structure with a false front and frame siding or an elaborate building with a second floor meeting room" (Blackburn 1979: 447). Among those who frequented saloons were miners, camp folk, "dancehall girls" and occasionally prostitutes. The latter group usually maintained separate fancy parlor houses in the mining towns. Downieville apparently had such a section in the 1850s (Woyski 1981: 42).

Sanitation in the camps was primitive. Streets and "were littered with empty bottles, old boots and oyster tins, hambones, wornout kettles, broken picks served as public dumps, hats, sardine cans, and shovels" (Fatout 1969: 14).

As earlier noted, mining camps grew and faded rapidly. At Goodyears Bar, mining began in late summer of 1849. The bar was first worked by Miles Goodyear, who died there in November 1849 (his remains were placed in an old rocker, covered with a buffalo robe shroud, and buried at Slaughter Bar across the creek,) By 1852, the bar and nearby flat was covered with houses; 600 votes were counted in the presidential election of 1852 (Drury 1969: 4-8). Similarly, the mining town of Alleghany grew up after 1853, as miners from nearby camps gravitated together to a better location (Sinnott 1981: 8). Other camps were established throughout the Forest during the decade of the 1850s; some, like Downieville, Alleghany, Camptonville and North San Juan, have survived to the present day. Others like Alpha, Omega, and Morristown have vanished as their available gold was mined out.

These mining camps and later towns in the Forest area, served as population centers for a variety of people. Among the many groups that arrived were the Chinese and Cornish. These two groups were exceptionally numerous in or near Tahoe National Forest.

As noted above, Chinese arrived in California as one of the earliest groups in the gold rush. The first were merchants who located largely in San Francisco; later Chinese came as miners (Mai 1979: 475). The Chinese brought supplies and equipment with them from China. "The (Chinese) immigrants always bring a chest of clothes and a bundle of bedding. But the amount of these articles is small, so that in a year or so you may notice inner parts, then shirts, then coats and caps or hats" (Quoted in Williams 1930: 25). A former miner, J. D. Borthwick, described the Chinese heading toward the mines in a fashion typical of many whites.

Crowds of Chinamen were also seen, bound for the diggings, under gigantic basket hats, each man with a bamboo laid across his shoulder, from each end of which was suspended a higgledy-piggledy collection of mining tools, Chinese baskets and boxes, immense boots and a variety of Chinese 'fixins' which no one but a Chinaman could tell the use of, all speaking at once, gabbling and chattering their horrid jargon, and producing a noise like that of a flock of geese. (Haskins 1890: 189)

The Chinese miners used the pan for some time after it was abandoned by white miners; and even after 1855, when whites had largely abandoned the rocker, the Chinese continued to employ it (Williams 1930: 56).

The Chinese mentioned by Borthwick were probably wise when they avoided direct competition with white miners, because when they did they were often treated roughly. Sir Henry Vere Huntley traveled through the mining region in 1852 and described an occurance on Deer Creek, a branch of the Yuba River.

The miners of Deer Creek . . . turned out last week and drove all the Chinese off that stream. The heathen had got to be impudent and agressive, taking up claims the same as white men and appropriating waters without asking leave . . . that afternoon about 50 miners gathered together, ran the Chinese out of the district, broke up their pumps and bores, tore out their dams, destroyed their ditches, burned up their cabins and warned them not to come back on penalty of being shot . . . (Huntley 1856: v. I, 222)

Chinese miners were also harrassed by Mexican bandits. State legislators gave official sanction to the anti-Chinese sentiment with the passage of a series of taxes and bills aimed specifically at the Chinese (Williams 1930: 67-69).

Faced with such opposition, many Chinese left mining and opened stores and restaurants in the mining camps and towns (IBID: 58-59). Chinese settlements in the mining region were of two kinds: camps located on or near mining claims along rivers, streams or in other areas; and Chinatowns within mining towns. Chinese mining camps housed Chinese only and usually consisted of a group of small tents and brush huts that served as shelter for the miners (Chinn 1969: 30). In contrast, Chinatowns were districts within a mining town separate from white areas. The Chinatowns functioned as supply centers for the Chinese camps and provided services (stores, laundries, restaurants) for the general population of the mining town, usually at a lower price from those charged by white owned businesses (Williams 1930: 39-41).

Much of the hostility felt by Chinese in California found its origin in a feeling that the Chinese were "swarming" in to take the mines from Americans. The Chinese did mine in groups and they tended to cluster about in a newly settled mining district, oftentimes for their personal protection. These migratory patterns intensified the fears of local miners who viewed the arrival of Chinese as "an invasion" of their territory. In some areas the Chinese population reached a significant percentage of the total population, however, in general they represented less than ten percent of the total population of the state. It was the rapid proportional increase and their obvious physical and cultural differences that led to the racist actions of white miners.

Another major ethnic group in the mining regions of the Forest were Cornish miners who were attracted to California mines in 1849 and thereafter from other mining areas in the United States and directly from Cornwall (Rowe 1974: 113). Most were concentrated around Grass Valley and Nevada City, but "more Cousin Jacks (Cornishmen) were located elsewhere in Nevada County" (Rowe 1974: 113). Their experience in mining, and especially in deep mining and tunneling made them particularly important as quartz mining developed after 1859.

Other ethnic groups, such as Latinos and Blacks were also present in the mining camps and towns within the Forest. In 1852, 241 Blacks were counted within Placer, Nevada, and Sierra counties (U. S. Census 1850: 982). These people, along with Latino miners, felt many of the same pressures that the Chinese did. Mexicans and other Latino miners left the diggings to take up other occupations like pack mule train wrangling. Blacks were heavily discriminated against, and many left the mines in California in 1858 when news of the discovery of gold on the Fraser River in British Columbia reached California (Rowe 1974: 137).

As the mining industry developed during the 1850s in terms of methods, equipment, and ability to reach deep deposits, only those camps that were located near highly productive mine sites or other important resources survived. During the 1850s many of the river bars were mined out; as deposits were exhausted, the occupants moved on. These camps disappeared because there was nothing besides the gold to keep people there. Camps like Goodyears Bar faded; towns like Downieville, Alleghany, Washington, North San Juan, Michigan Bluff and others survived because the mines were rich or other factors permitted development of diversified economic activities.

Compare the description of mining camps, with log and brush huts, tent buildings and saloons to two mining towns, Alleghany and North San Juan. Alleghany, located on extremely rich deposits, was established as a town when people in adjacent mining camps moved to its better geographic location. As the town grew, portions of the earlier camps were incorporated within its boundaries. Miners from Pennsylvania and the eastern states made up most of the population. North San Juan was described by the Hydraulic Press in April 1859. The town had a population of about 1,000; 100 families, some of whom had built small cottages and houses with planted gardens. The town had eight brick buildings on Main Street, testimony to the feeling of permanence felt by the inhabitants. The town also contained a public school, brewery, church, three hotels, four or five sawmills, two restaurants, an iron foundry, about sixty stores and shops of various kinds (of which twenty sold liquor) "and more houses of ill fame than we like to mention." The town had a library with 600 volumes, Masons and Oddfellows clubs, a "Mutual Relief Society," and a temperance association "consisting entirely of Welshmen." Of the 250 houses in or near town, forty "ramshackle affairs" were inhabited by Chinese. The number of miners' cabins in the surround territory was unknown (Hydraulic Press 4/2/1859). Clearly a town like North San Juan was much different than the early mining camps that were settled in the first years of the rush. While these towns were not immune to change, they had the fundamental structures representative of a more modern stable, mature society.

|

|

THE MOUNTAIN EXPRESSMAN From "Chips of the Old Block" by Alonzo Delano. Woodcut by Nahl. (Wiltsee 1931: frontispiece) |

Supplying the Mines, 1848-1859.

The growth of gold rush era camps and towns stimulated the development of an industry based on supplying mines and camps with needed mail, express and provisions. While at first the pack train system was primitive, providing only limited supplies and selection, throughout the fifties both the transportation system, and the goods and services it made available, became more varied and complex.

Goods heading for the mining region within the Forest normally came out of San Francisco and distribution points in the valley like Sacramento and Marysville. Because the area that Marysville served was so rugged, it became the major packing center in California. Freighting with wagons was not undertaken until hydraulic and quartz mining developed in the late 1850s and gave a greater aura of permanence to the settlements east of Marysville, justifying the heavy expenditures commonly required for road building (McGowan 1949: 209-218). These transshipment points were scenes of great activity during the period.

. . . Steamers and barges unloading, merchandise stacked all around, and the busy pack-mule trains, and afterwards, wagons loading for the arduous uphill journey to the foothills and the camps of the mines which dotted their broad expanse. (Wiltsee 1931:

The earliest transportation into the mines was done by the miners themselves, with crude wagons, pack animals, or backpacks. There were, at first, no stores or trading posts within the region (Wiltsee 1931: 3). One of the first Cornishmen to arrive in the mines, a Col. Collins, wrote his family from the North Fork of the American River in August 1849.

We had a hard time getting our baggage and provisions to this place distant from San Francisco about two hundred miles. We came within some forty-five miles of this place by water, and then purchased a wagon and a yoke of oxen between seven of us, which by packing them up the mountains, we brought about a hundred and twenty pounds to this place, and sent the team back and brought up nine hundred (pounds) more. The price of carrying this forty or forty-five miles is from twenty to twenty-five cents per pounds, and can scarcely be had for that. We were lucky in getting a yoke of cattle cheap that had been driven from Oregon. They were of small size, about such as you could get about twenty dollars for in Wisconsin, but we were glad to get them at one hundred and fifty dollars. — Our wagon — oh such a wagon! — why you would have to give a boy to [sic] bits to burn the tire off, and yet it was worth a hundred and fifteen dollars. (Quoted in Rowe 1974: 103)

Such high costs reflected the lack of facilities and equipment. In such a situation many avoided mining and went into some other business. Some bought and sold gold dust; others provided primitive banking services; others used what gold they had to begin farming, teaming or packing into the mines (Wiltsee 1931: 7).

One stimulus for the development of freighting and express companies was the desire of miners for news from home and the outside world. The miner's "thirst for tidings seemed increased in proportion to his remoteness" (Wiltsee 1931: 15). The mails would be delivered to "basetowns" like Marysville and Sacramento by national express companies, and then transferred to smaller express companies that served the mining camps within specific areas. Only after towns in the mining region proved their permanence (e.g. Downieville, Nevada City, Alleghany, etc.) did the major express companies begin to establish their own routes and offices (IBID: 22-23).

The topography of areas within the Forest was a major determinant in locating and constructing wagon roads. In the area drained by the American River, the somewhat less rugged nature of the hills and canyons allowed wagons to travel into the area early; in fact before roads as such were built (Rowe 1974: 103). Goods transported to Sacramento were taken up to Auburn, and then sent into the mining region by two trunk routes. The first led up the divide between the Middle and North Forks of the American River, to Grizzly Bear House, Butcher's Ranch and Yankee Jim's. From this point the road split, one heading to Forest Hill and Michigan Bluff and the other south to Todd Valley. The other road out of Auburn followed the divide between the North Fork of the American and Bear rivers through to Alder Grove (later Illinoistown) just below modern Colfax. Goods taken to this point were transferred to pack trains heading farther up into the mountains. Goods from Sacramento also supplied Rough and Ready, Grass Valley and Nevada City (McGowan 1949: 415).

The Yuba River basin, with more precipitous canyons and rugged terrain, was supplied until late in the 1850s largely by pack trains. By 1851, as many as one thousand mules a day left Marysville with 100 tons of goods for the mines (McGowan 1949: 209). The Marysville Herald (3/29/1851) reported that "all along the Yuba road at any hour of the day droves of pack mules can be seen on their way into the hills." Most of the early pack train owners and operators were Mexican; their profits stimulated Americans to invest in pack operations and hire Mexican drovers in 1850-51 (McGowan 1949: 209).

There were a number of trails out of Marysville, the most heavily used following creeks to the divide between the Yuba and Feather rivers, and then turning either toward Downieville or Onion Valley. There were also trails leading into the Yuba-American river basins, but these were not of major importance (IBID: 213). The main trail from Marysville to Downieville ran alongside the main Yuba to Hermitage, then up to Foster's Bar via Galena House, Stanfields, Dry Creek, Keystone and Oregon Creek. The road then crossed the North Fork of the Yuba and followed the ridge between Oregon and Willow creeks to the summit between the North and Middle forks of the Yuba, passing Camptonville and Oak Valley. In 1850 this trail continued up the ridge to Galloway's Ranch above Downieville before descending into town; later routes went by way of Mountain House and Goodyears Bar to avoid the steep grade. The road from Marysville to Downieville via Goodyears Bar was sixty-five miles long (Sacramento Union 6/17/1852; McGowan 1949: 214-15). Improvements on this pack trail allowed wagons to reach Fosters Bar by 1850, and by 1853-54 a road connected Camptonville and North San Juan. Trails leading into the Slate Range mines left the Marysville-Downieville trail at Keystone, passed Indian Ranch on Dry Creek, went up Dry Creek to Challenge, Woodville and Orleans, and then off the forest (McGowan 1949: 216, 218, 373).

|

| RESIDENCE & FARM OF A.P. CHAPMAN, 240 acres, 8 miles N.W. of Sierraville, Co. Cal. (Fariss & Smith 1882) |

Other smaller trails radiated out from mail trail destinations like Downieville, Auburn, Nevada City and so on. An early trail linked Downieville with Sierra City, built along the north side of the river. Pack mule trains extended this route into Sierra Valley in 1851, crossing the mountains by way of Bassett's to Chapman's Creek, through Chapman's Saddle and on into the Valley past Chapman's Ranch. Isaac Church, a Vermonter who arrived in California in 1850, established a pack mule service between Marysville and Sierra Valley in 1851. His service ran for ten years (Sinnott 1976: 32). Samuel W. Langton operated several express companies in the Yuba mines in the 1850s. His first, "Langton's Yuba River Express" ran in 1850 from Marysville up the Yuba and served Nevada City, smaller camps, and on to Downieville. He reorganized the company several times until 1855 when he established "Langton's Pioneer Express" which he ran until his death in 1864; by 1865 Wells Fargo purchased it from his heirs (Siltsee 1931: 53).

Pack trains operated before roadhouses, inns and way stations were built, and the packers would camp out in a clearing or meadow that had grazing, wood and water. These gradually became regular stopping points. Mules were unpacked and their loads arranged in a row or circle, with each pack saddle next to its load. Mules were put out to pasture nearby. The mountain trails were dangerous for the mules; some were only "as wide as our feet," with wall on one side and steep slope on the other. The mules hugged the wall, the packs grazing projections. Descending steep slopes was dangerous, hard work for the mules and drivers. From the ridge top to Goodyears Bar the slope descended 2,000 feet in four miles (McGowan 1949: 184-7)

By the mid-1850s, a road was established to Brandy City, northwest of Indian Valley. It had been connected to Oak Valley and Camptonville by a mule trail that descended the western ridge of Cherokee Creek, crossed the Yuba on a bridge near the creek mouth and then ascended the mountain into Camptonville (Sinnott 1972: 15). Part of this trail had a grade of forty percent (McGowan 1949: 182). Other towns like Forest City were served throughout the 1860s by pack train (Fariss and Smith 1882: 474).

The early pack train express companies carried a wide variety of goods into the mines. Mail was one of the most important items, and it was often the case that the express companies moved the mail faster than the post office (Wiltsee 1931: 71-73). Food included flour, jerked beef, salt pork, beans and coffee. After 1849, rice, sugar, and dried apples became available. Fresh vegetables were usually purchased and consumed in the Central Valley towns on the way to the mines before they reached the miners. In 1848-1849, only potatoes and onions were available, and were sold for $1.00 each to miners suffering from scurvy. Dairy products, green vegetables, butter and eggs were rare until after 1850. Selling food in the mines was highly speculative, heavily competitive and often quite lucrative (Margo 1947: 11-15, 26). Besides foodstuffs, dry goods, furniture, and even iced snow was packed in and out of the mountains. Daniel Dancer, a famous Marysville-Downieville packer, brought a grand piano into the mountains on mule back (McGowan 1949: 189, 191).

Some Sacramento and Marysville merchants opened branch stores in mining towns. The Stanford Brothers stores were an example of this system. Josiah Stanford, the first of the brothers to arrive in California (in 1850) began a store at Mormon Island on the American River, and as each brother came out he set them up in various mining towns. As mentioned earlier, his brother Leland ran the store in Michigan Bluff (Margo 1947: 44-45; Kraus 1969: 14). Some of the chain-store operators had their own pack teams or trains, but most hired packers to transport their goods by contract (Margo 1947: 45).

|

| "THE EXPRESS HAS ARRIVED." From "Chips of the Old Block" by Alonzo Delano. Woodcut by Nahl. (Wiltsee 1931: 13) |

As mining camps developed into more permanent towns, wagon roads, as distinct from pack trails, were built to connect them with valley supply centers. Roads were built first where topography allowed. As roads gradually were extended into the mining region, pack trains continued to operate from "terminals" at the head of "wagon navigation." Towns like Marysville became more and more stations for teamsters rather than muleteers. The packers loaded up their animals at the road terminals and operated between these points and remote camps (McGowan 1949: 225).

Interest in roads was great in all of the mining towns within the Forest, and roads were sometimes built to try to attract the freight business into an area. In 1852, an "Emigrant Road" was built from Yankee Jim's through the central Sierra Nevada to the Washoe Valley. It cost $13,000, was poorly made and virtually ignored by immigrants who used the Carson Route over the mountains (Thompson and West 1882: 283). Placer County was largely bypassed by the major wagon routes until the 1860s; this road represented an early attempt to pull immigrant traffic through the county.

By 1854, wagon roads extended into the Yuba basin mines. The Sacramento Union (11/28/1854) noted that where pack trains had been encountered in the past were now heavy wagons "at intervals of almost every ten minutes. . . . Teamsters and others are mainly indebted to individual enterprise for these changes which have cut down the hillsides and blasted through solid rock, to secure them one of the best and safest thorough-fares anywhere to be found in this region of the country." Robinson and Company's $12,000 wire-fastened bridge over the South Fork of the Yuba and seven miles of road were noted, as well as the efforts of Mr. Emory to extend the road across the high ridge beyond the Middle Yuba crossing, at a cost of $10,000. The Union also noted settlers and improvements along the route; sawmills were built and "houses by fifties." As government was unable or unwilling to finance road building, individuals or companies undertook the construction projects and operated the thoroughfares as toll roads. The Nevada County Recorder's Book of Corporations #1 listed nine men as shareholders in the Alpha and Washington Toll Road in November, 1855. Toll bridges were erected wherever rivers were too deep for fording. Toll bridges were built along the South Fork of the Yuba River above and below Washington in the early 1850s (Slyter 1972: 37, 45). The original toll bridge across the North Fork of the Yuba was built in 1859 as a part of the Sierra Turnpike. The piers of this bridge were still visible in the 1900s (Tahoe National Forest Historical File). Toll roads and bridges were also built in Placer County, including at least two on the forest. One, named the Volcano Canyon Turn-Pike, traversed Volcano Canyon from Baker's Ranch to Michigan Bluff. J. A. Matteson built this road in 1856. Two years later he constructed another road from Bath to Michigan Bluff at a cost of $12,000; obviously Matteson expected enough traffic to recoup his investment (Thompson and West 1882: 288).

Placer County continued to be interested in a road across the Sierra Nevada, especially as other areas began building or promoting such roads. In 1856, Thomas A. Young and a party of six surveyed a route from Forks House to Secret Spring, through Robinson's Flat to the crest, down Squaw Creek to the Truckee River and on to the Washoe. Young submitted a report on this route to the State Surveyor General, but other routes appeared more practical and the route was never developed (Thompson and West 1882: 284-285). Similar surveys were filed regarding the Henness Pass and Beckwourth routes (Surveyor General 1856: 191-192; 193-194). In contrast to the Placer County route, these were eventually built, largely to provide service to teamsters and miners heading toward the Washoe after the Comstock discovery in 1859 (Jackson 1967: 22-23).

The road that became known as the Sierra Turnpike, connecting Camptonville and Downieville via Goodyears Bar and Mountain House was completed on July 4, 1859. The day was one of great celebration:

. . . The stage came up from Camptonville, decorated profusely with flags and banners, and the horses decked out in proper colors. This was a great day of rejoicing in the mountains, for it meant the abandonment of the time-honored pack-mule, who had painfully threaded the narrow trails for so many years, and the establishment of a closer communication with the outside world on wheels greatly more indicative of a country civilized and prosperous. Praises went up from all sides to Colonel Platt of Forest City, to whose untiring efforts, with voice and brain, were largely due the successful issue of the enterprise. (Fariss and Smith 1882: 469)

|

| LODGINGS ABOUT 1855 (Cross 1934: 204) |

A road connected Forest City to the Sierra Turnpike in 1860, and a tri-weekly stage service was begun (IBID: 474).

Most of the early teamsters were former gold seekers who had crossed the plains and thus had wagons at their disposal (McGowan 1949: 279). The Sacramento Union (6/16/1858) estimated that seventy percent of the teamsters were from Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa and Missouri, with Ohio and Missouri supplying the majority. Many left the business as soon as they had enough money to buy a ranch, toll-bridge or ferry.

The earliest teamsters used any available cart or wagon, but by the mid-1850s wagons specially designed for mountain freighting came into general use. Wagons brought in from the east were usually too heavy, unable to carry heavy cargo or withstand the wear-and-tear of constant hard use. The mountain wagons were made of pine, "shaped very much like and old-fashioned bread trough." They carried 9,500 pounds, weighed 3,800 pounds empty, and required teams of eight mules to pull them (Margo 1947: 51).

Teamsters generally took lodging in roadside inns that had developed during the pack train era. As teaming became more important, the number of inns increased. Typically, there was an inn or way station about every three miles on the main routes. During 1849 and 1850 these were often nothing more than shanties or tents set up near water and grass. Such places usually furnished a meal and a place to sleep. After 1851, inns became more elaborate as competition between the growing number of stops forced proprietors to offer better fare. As a result, large, permanent structures replaced shanties and tents (McGowan 1949: 299-302).

Occasionally teamsters combined their freighting operations with other businesses. Daniel Cole, with his partners Warren Green and John Sharp, ran a daily stage from Marysville to Sierra City. Cole also owned a hotel, lumber company, and other businesses at Mountain House (White 1961: 70).

With the construction of permanent, improved roads after 1851, roadside buildings became "more substantial and pretentious," their architectural styles reflecting the builder's place of origin. Two story buildings with a complex of outbuildings appeared, and these depended more on travelers and teamsters than local miners for their clientele. The typical inn was located close to the road, and offered a barroom and dining room. "There were no tablecloths, and the individual's equipment consisted of a tin plate, a cup, knife and fork." Bedrooms were in an annex or on a second floor. The kitchen typically had a stove or fireplace. The inn often provided a barn or corral for animals, and occasionally had a range for grazing. Outbuildings included a roothouse, usually partially or totally underground with a thick sod roof; a milk house "built, whenever possible, over a running stream or spring" or in the inn's cellar; a smoke house with no openings but a small door, and a firepit and poles for hanging meat; and the inevitable pigsty and privy. "Apart from economic strategic considerations, the wayside inns were always located with an eye to water and fuel" (Cross 1954: 10-13). Inns also often cultivated kitchen gardens for fresh vegetables and fruits (McGowan 1949: 303).

Inns and hotels were described in a variety of terms. The Sacramento Union (11/28/1854) outlined the different conditions prevailing. "Nearly every stopping place is an inn of entertainment, some of them noted for keeping execrable beverages, which are partaken of at the imminent risk of a sick stomach; others offering the inducement of an excellent dinner or . . . a clean bed." These stations dotted the wagon roads and pack trails within Tahoe National Forest. Among the more famous of these were the Mountain House, located at the junction of the trail to Goodyear Bar and the trail to Henness Pass Road at the crest of the Mountain House Grade; Sleighville House two miles east of Camptonville (TNF Historical File); and Plum Valley Ranch, three miles from Forest City (Sacramento Union 11/28/1854).

The building of roads and bridges greatly aided the economic development of the mining region, and made possible much more convenient travel and communication. Roads were rough. However, despite rugged conditions, toll bridges and uncivilized inns, these roads provided the means to more easily supply the mining towns within the Forest, and resulted later in gradual development of industries not totally dependent on mining.

Logging and Agricultural Development.

Logging and agriculture within Tahoe National Forest during the decade 1849-1859 were tied closely to, and served primarily, the mining industry. Both found local markets for goods produced; little that was produced on the Forest left the area. It was not until transportation systems like railroads were built through the region that many of the products of the Sierra Nevada foothills and eastern Sierra Nevada valleys could be economically transported to distant markets.

The use of timber resources began in the Forest with the arrival of the first miners, who felled trees and used them to build crude cabins and other shelters. John Potter cut trees near Downieville to build a cabin in December, 1849; others soon followed (Fariss and Smith 1882: 456). The trees were apparently cut down by the miners themselves. Miners in other areas of the Forest availed themselves of trees and brush for early shelters as well.