|

History of Tahoe National Forest: 1840-1940 A Cultural Resources Overview History |

|

CHAPTER VI

Concluding Statements

During the gold rush decade the population density of the Tahoe National Forest area was far greater than in any subsequent period of history. Important towns such as Downieville, once inhabited by over 5,000 people, never again attained a size of more than a few hundred. With the exception of the decade of the 1870s, when hydraulic mining output increased rapidly, the regional population declined precipitously from the 1850s into the 1920s. According to census figures, the population estimate of the forest for 1920 can be set at a level of perhaps one-fifth that of 1850. The general decline in population for each of the three counties is clearly reflected in statistics from the U. S. Census Bureau for townships lying wholly or partially within the Tahoe National Forest boundaries. These figures are provided in the following table.

ESTIMATED POPULATION WITHIN TNF BOUNDARIES

() indicates decadal population change in percentages.

| COUNTY | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | ||||||||||

| Nevada | 20583 | 10933 | 10861 | 12571 | 9440 | 9670 | 7957 | 4656 | 4818 | 7350 | ||||||||||

| (-47) | (-1.0) | (+16) | (-25) | (+2.0) | (-18) | (-41) | (+3) | (+53) | ||||||||||||

| Placer | 10783 | 5670 | 5126 | 5420 | 4646 | 3508 | 2032 | 772 | 1516 | 2045 | ||||||||||

| (-46) | (-10) | (+6) | (-14) | (-24) | (-42) | (-62) | (+96) | (+35) | ||||||||||||

| Sierra | 3741 | 7340 | 5619 | 6623 | 5051 | 4017 | 4098 | 1783 | 2422 | 3025 | ||||||||||

| (+96) | (-23) | (+18) | (-24) | (-20) | (+2) | (-56) | (+36) | (+25) | ||||||||||||

| TOTAL | 35107 | 23943 | 21606 | 24614 | 19137 | 17195 | 14087 | 7211 | 8756 | 12420 | ||||||||||

| (-32) | (-10) | (+14) | (-22) | (-10) | (-18) | (-49) | (+21) | (+42) | ||||||||||||

Between 1920 and 1940 the Forest population almost doubled and can be explained largely by improved transportation access which stimulated permanent settlement, migration of urban unemployed to the region during the Depression, and the general prosperity of the mining districts.

One of the most marked characteristics of the Tahoe National Forest population has been its geographic mobility. Many miners arrived at the diggings without any intention of remaining there for a long period of time. Once in the gold fields they moved about at the slightest news of rich diggings elsewhere. They rushed from stream to stream throughout Northern California, into Nevada and Arizona; over the Inland Empire of Washington, Idaho, and Montana; to the Rocky Mountains and the Black Hills; even into Canada. Wherever they went, merchants and farmers, freighters and lawyers followed. Loggers moved their mills and camps whenever they finished cutting over a new area. Industrial practices in the lumber and mining industries helped stimulate a high level of geographic mobility since they attracted young unmarried men without roots in the region. William S. Eggleston who worked in the Alleghany mines during 1923 recalled how jobs were filled in construction, lumber and mining camps from the "Slave Market" in San Francisco:

The San Francisco office was nothing fancy. It was in the warehouse district and was just a single room on the ground floor of a rather ramshackle building. The room was rectangular, about 30 feet long and 20 wide. A rough wooden table with attached sitting benches occupied the center of the room. In the middle of the table was a large bowl of smoking tobacco with packets of brown cigarette papers scattered about the bowl. Miners and cow-punchers all rolled their own as did most other working men of that time.

On the walls were mounted blackboards, each section devoted to a particular industry that made a practice of hiring day labor. There were ranch jobs, construction jobs, jobs in the woods, and mining jobs. Each section listed jobs available and the daily or monthly wages paid. For instance, in the mining section were listed: Timberman — $5.00 per day; Mucker or Trammer — $4.00 per day; Miner-machine — $4.50 per day.

In one corner of the room was a small cubicle with a clerk sitting at a small desk. After looking over the board to see which job you could qualify for, you went to the door of the small office and told the man at the desk which job you wanted and, if the job was out of town, you were given a railroad ticket or a stage ticket to get to the job. If you stayed on the job a month, the fare was cancelled out. So, for one dollar, you could not only get a job, but you got your transportation. (Eggleston 1981: 49-50)

The proportion of the Forest population living this transient lifestyle was extremely high. Supervisor Bigelow's special population report for the Tahoe National Forest estimated that of the 8,860 persons living or working within the boundaries of the Forest in 1912, 4,101 or 46.3 percent were transients. These were not drifters, nor irresponsible loafers, but working men holding down jobs on the Forest. Almost one-half were employed in the lumber industry; seventeen percent were engaged in some form of prospecting or mining; less than seven percent were herders, packers, or otherwise employed by ranchers; miscellaneous "other occupations" and temporary Forest employees accounted for the balance (Bigelow 1913: 1).

Sometimes the movements of these people were seasonal. Circumstances that caused them to move from place to place were obviously in some cases related to the natural rhythms of nature. Forest employment in the construction lumber and ranching business was largely seasonal. Mining work was also often ended with the advent of winter.

|

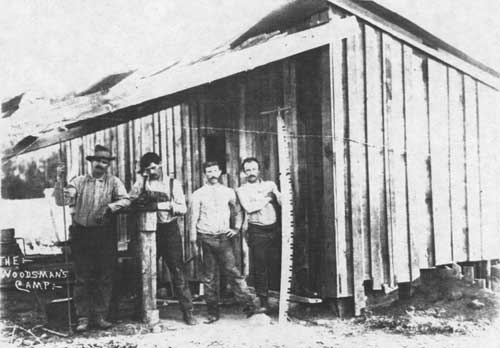

| TEMPORARY LOGGING STRUCTURE |

|

| FIR CAMP, FOREST HILL; 1924 FIRE FIGHTER'S PAYDAY |

What difference did it make that people on the Forest in earlier times moved from place to place and job to job with such frequency? Certainly it made difficult the formation of communities and worked against social integration of people into the places in which they worked and lived. Transiency introduced instability into the society of the region and makes problematical to the modern observer even the definition of the population of any one place. Needless to say, these factors make it much harder to study a community as a working organism over time. Did population estimates of a place, in the eyes of contemporary observers upon whom we rely so heavily for information comprise the people living there for any specified period of time, or all those present at any one moment even though they would be gone within hours, days, or weeks? As late as the 1930s, population statistics for towns within the Forest gathered by the U. S. Census, the Forest Supervisor, the Resettlement Administration, Rand-McNally and Hammond differ significantly. Hobart Mills' population was variously recorded as 400, 510 and 609; North Bloomfield's estimates ranged from 510 to only 50 persons; Sierra City recorded populations of 250, 510 and 189 (USFS 1937: 2).

The implications of transiency in understanding community development and the day-to-day lives of the common man on the Tahoe National Forest are clear enough. Answering such basic questions as how the historic communities were structured, how the parts of society worked together, what underlying forces eventually altered both structure and function will be a difficult task for future researchers. In the gold rush mining economy of the 1850s (and later), and in the logging towns and camps, transient laborers were every bit as important as agriculturalists, merchants, and corporate miners. If nothing else, they were producers and consumers. An assessment of how the economy functioned and how the society was structured must take into account all of these participants. Only through detailed historical analysis and synthesis together with archeological field work will be begin to understand and appreciate even the most rudimentary details of the lives and values of these predominantly anonymous people.

Answering questions about some of the key processual change that occurred on the Tahoe National Forest is a task far beyond the scope of this historical overview. We have here provided a basic outline of the major periods of economic and social development, discussed transportation improvements and methods, industrial technologies, land use patterns, resource development, conservation policies and have tried, where possible, to assess their impact on the region and its inhabitants. Our research raised many interesting challenges for the historical archeologist, cultural resources managers, and social and economic historians.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

region/5/tahoe/history/chap6.htm Last Updated: 06-Aug-2010 |