|

History of Tahoe National Forest: 1840-1940 A Cultural Resources Overview History |

|

CHAPTER V

Era of National Forest Management, 1906-1940

The post Civil War period was an expansive one. Americans rushed to settle vast tracts of hitherto uninhabited land in the west. In 1860 the western frontier of settlement lay near the Missouri River, and between eastern Kansas and the West Coast; there were hardly any white inhabitants except the Mormon settlement in Utah. The decade of the 60s brought homesteads for the farmer and land grants to railroads and institutions of higher learning. In the following decade, Congress offered further incentives to make western lands more appealing through passage of the Timber Culture Act (1873), the Desert Land Act (1877), and the Timber and Stone Act (1878) (Land Planning Committee of the National Resources Board 1935: 60-71). By the nineties, immigrants pushing west into the Great Plains and Rocky Mountain regions and east from California formed a virtually uninterrupted pattern of settlement across the continent. In 1890, the superintendent of the United States Census announced, perhaps prematurely, that the frontier was eliminated. "Up to and including 1880 the country had a frontier settlement but at present the unsettled area has been so broken into by isolated bodies of settlement that there can hardly be said to be a frontier line" (U. S. Census Bureau 1890).

By far, the most influential piece of writing about the west produced during the 19th century was the essay on "The Significance of the Frontier in American History" read by F. J. Turner at the 1893 meeting of the American Historical Association. Turner's "frontier thesis" that America's democratic institutions owed much of their identity to the presence of an area of free land on the western edge of the advancing settlements revolutionized American historiography and has remained provocative enough to generate controversy among historians for four generations. Turner predicted that with the end of a frontier would come major changes in national thought. Among the impacts would be a lessening of cheap resources that would force Americans to adjust their economic, political and daily lives to a new kind of world (Billington 1966: 1-31). In fact, the latter 19th century did bring important new themes to American environmental thought. Chief among these was the belief that science and scientific methods must become the chief foundation on which environmental plans would be built. The image of the land as holding inexhaustible economic opportunity gave way to the vision of technological abundance. New professional groups of conservationists, engineers, city planners, architects and scientists sought a new set of environmental ideals relating to urban, industrial society. Among their shared assumptions was that it was better for society, through the agency of experts, to design and direct the development of the landscape rather than leave the process in the hands of untrained, self-interested men. Coordinated public planning was viewed as necessary to curtail haphazard and exploitative practices common in the laissez-faire approach (Worster 1973: passim).

Establishment of Tahoe Forest Reserve.

The scientific community raised the issue of more efficient management of natural resources long before the progressive politicians made a popular crusade of it in the early twentieth century. Perhaps the single most influential work by an American was George Perkins Marsh's Man and Nature (1864). Marsh graphically illustrated the devastating impact man had exercised on the natural world. Over half of his book dealt with the function of forests as critical agents of soil and water conservation. He recommended that forests be managed scientifically, trees grown on farms, and only mature timber harvested. Marsh's treatise was widely read in America and Europe. He exercised great influence on a few important scientists and policymakers, but his insights and recommendations were only rarely applied in the United States during the nineteenth century.

As early as 1855, the Department of the Interior attempted to stop timber theft from public lands, but local land officers largely ignored timber trespass and local juries were reluctant to convict lumbermen brought to trial. In the 1870s the American Association for the Advancement of Science membership lobbied for Congressional action on forest protection and preservation, claiming that lumbering practices were illegal. No legislation came from the association's efforts, but in 1875 Congress created the Division of Forestry under the Commissioner of Agriculture asking it to prepare a report of United States forest production and consumption. The report, which drew heavily on Marsh's theoretical considerations, set off new interest in forests and led to the organization of the American Forestry Association in 1876 (Steen 1976: 4-19).

Concern for forest conservation and preservation of scenic beauty found expression in several forums in California by the mid-1870s. By that time lumbermen were already making sizable cuts into the giant redwood groves. In 1876 John Muir complained in several newspaper columns and national journals of government inertia in the face of wholesale destruction of the "Big Trees." Concern over clear-cutting Tahoe's forest led a local newspaper to cry out in opposition to the lumber barons who were destroying the "gem of the Sierras."

If in some cathedral there was a picture painted and framed by an angel, one such as mortal art never could approach in magnificance, the world would be shocked were some man to take off and sell the marvelous frame. But Tahoe is a picture rarer than ever glittered on cathedral walls; older, fresher and fairer than any work by the old masters, and yet they are cutting away her frame and bearing it away. Have we no state pride to stop the work? (Truckee Tribune 9/7/1878)

By the 1880s, writers, professionals and scientific groups began to threaten that the country would face a "timber famine" if steps were not taken to stop the plunder and destruction of the country's forests. During Grover Cleveland's first administration (1885-1889) some efforts were made to prosecute land law violations by timber and cattle companies. Denouncing timber frauds in Northern California, the General Lands Office launched investigations that found lumber companies openly using farmers, sailors, and laborers to file under the Timber and Stone Act of 1878, which allowed acquisition of 160 acres of timbered and stony land at a nominal price. The land conspirators would purchase a claim and then immediately re-sell it to the company at a modest profit and go about their other business. General Land Office agents investigating the cases claimed that perhaps three-fourths of the claims filed were fraudulent (USDI, Annual Report 1886: 95, 200-213).

In addition to investigating fraud on public forest lands, Cleveland appointed a professionally-trained forester, Bernhard E. Fernow as chief of the Division of Forestry. Fernow suggested professional management practices and introduced legislation proposed to create forest reserves and the means to administer them. He met with strong opposition in Congress. However, the Forest Reserve Act of 1891 authorizing the President to set aside forest reservations was finally passed as a little recognized rider to a bill whose main purpose was to revise a series of land laws. President Harrison duly created six forest reservations including over three million acres in 1891-92; later he added nine more timber reservations totalling an additional three million acres (Steen 1976: 22-30). Grover Cleveland added five million more acres during his second tern. Included in these early reservations were the San Gabriel and San Bernardino reserves in Southern California, as well as the vast four million acre Sierra Forest Reserve stretching from Yosemite National Park south beyond the Sequoia (Strong 1981: 81). Forest land in the Northern Sierra Nevada remained unprotected.

The 1891 act provided for withdrawal of the forested land but did not specifically deal with administration of the forest reserves. Until management provisions could be devised, the resources on reservations were essentially locked-up. On the other hand, since Congress provided no funds to protect the reserves from plunder, fire, mining or grazing, they probably fared no better than unreserved lands on the public domain.

In 1897, another major piece of legislation, the Sundry Civil Appropriations Bill, passed Congress with unexpectedly strong western backing. An amendment to the appropriations bill authorized the president to modify or suspend or revoke any forest reserve. It stipulated that no reserve should be established unless it would improve and protect the forest, the water flow, and furnish a continuous supply of timber. No lands were to be set aside as reserves if they were better suited for mining or agriculture. Perhaps most significant, the act also gave the Secretary of the Interior the authority to permit cutting and use of timber and stone for firewood, building, mining, milling and irrigation. The timber selected for sale had to be appraised, advertised, sold at or above appraised value, "marked and designated" prior to cutting and supervised during cutting (USDI, Annual Report 1897: CIX-CXIV). The act appealed to some western opponents of conservation because it reestablished commercial access to the national forests; it also paved the way for Gifford Pinchot's resource utilization policies on the national forests.

From 1891 to 1905 the responsibility of administering the forest reserves remained with the Department of the Interior, however, the department turned more and more to the Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture for technical recommendations and administrative planning.

Gifford Pinchot succeeded Bernhard Fernow as chief of the Division of Forestry in 1898. From a staff of 123 when he accepted the appointment, Pinchot gradually expanded the Forest Service to an organization of 1,500 people in charge of 150 million acres of forests in 1908. In 1902, E. T. Allen and Pinchot wrote a comprehensive manual issued by the Department of the Interior regarding administrative procedures and policies for the reserves. The two principle reasons for the reserves, the manual stated, were for protection of timber and regulation of water. However, regulations for many other forest-related activities were also addressed.

The manual explained that farming on reserve lands better suited for agriculture was desirable; that prospecting and mining were not prohibited; that roads, trails and irrigation canals could be built by permit only; and that schools and churches could be constructed on public land. Grazing, the rangers were reminded, could be forbidden if damage to the reserve was probable. Regulations prohibited grazing until after it had been shown that no damage would occur. (Steen 1977: 53)

Policies related to grazing and timber management demonstrated clearly that one of Pinchot's obligations was to manage the reserves to the benefit of those living on or near the reserves. Settlers in forest communities were eligible for permits allowing free use of timber. Timber sale procedures provided that "local demand will have first preference." Grazing permits were to be issued individually to cattlemen living in close proximity to the reserve (IBID 1977: 59-60).

On February 1, 1905, President Roosevelt gave final approval for transferral of the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture. Six months later the Bureau of Forestry was renamed the U. S. Forest Service with Pinchot heading up the agency as Chief Forester. Pinchot immediately began to write a policy blueprint for operation of the Forest Service that was published in a 4 by 7 inch, 142 page volume of regulations and instructions known as the Use Book, designed to fit in a ranger's shirt pocket. Use, the manual made clear, was not contrary to conservation. In Pinchot's perspective, three simple principles governed the management of forest lands: development rather than husbanding of resources; prevention of waste; and development and preservation for the common good (Pinchot 1910: 40-42). Wise use and scientific management for the nation's long-lived material prosperity were the hallmarks of the Chief Forester's philosophy, not preservation for aesthetic considerations or wildlife habitats.

Tahoe National Forest.

Concern over the denudation of timber lands in the Tahoe-Truckee basin had been vocal since the mid-1870s. The State of California took official notice in 1883 when Governor Robert W. Waterman appointed the Lake Bigler [Tahoe] Forestry Commission to investigate the situation in the basin. The three-man commission spent the summer at Lake Tahoe. They discovered that the Nevada side of the lake was largely stripped of its timber while the California side was less thoroughly logged. Of the land in California, roughly one-half belonged to the Central Pacific and the remainder still belonged to the federal government with the exception of selected state school lands and some lakeshore properties belonging to wealthy San Franciscans. The commission recommended that Congress exchange the railroad's lands for lieu lands of equal value outside the basin and then to deed all federal lands to the state "for the purpose of forever holding and preserving it as a State Park" (Report of the Lake Bigler Forestry Commission 1885: 12). The proposals met with opposition in the state senate perhaps because of popular perceptions that the railroads land transfer suggested a "deal" with the corporate interests (Pisani 1977: 12).

In the 1890s, interest in preserving properties in the Tahoe basin once again received considerable attention. Unfortunately by that date the Carson and Tahoe Lumber and Flume Company had completed cutting timber from its tracts at the south shore of the lake and by the end of the nineties large areas in California had been logged. One journalist in 1900 reported: "there has been a dunudation of nearly the entire original forest so far back as it has had a commercial value, from the shoreline of the lake back for 10 or 15 miles" (Bartlett 1900: 247). By the mid-90s, the recently organized Sierra Club, which had been influential in gaining support for the huge Sierra Forest reserve, began campaigning for protection of the forest range in the northern Sierra. The club won support for a 260,000 acre park on the California side of Lake Tahoe from California and Nevada top officials, university faculty, and the Secretary of Interior. The General Land Office sent B. F. Allen, a special forest agent and supervisor, to examine the proposed park. He strongly recommended creation of a National Park (Pisani 1977: 14).

Allen's report received wide publicity in the California press (San Francisco Call 12/24/1897) and the opposition forces quickly mobilized. Local residents and business interests were alarmed, especially vigorous was the protest from El Dorado County residents who petitioned the Commissioner of the General Land Office. The petitioners argued that the proposed reserve would reduce the taxable property of the community, be detrimental to the grazing rights of sheepherders and restrict the private development of fruits and potatoes on land suitable for agriculture. Lumbermen who operated in the Sierra region complained about the reserve as a threat to their jobs and investments (Strong 1981: 82). The Placerville Mountain Democrat (2/18/1898) agreed, noting in an editorial that the reserved land would serve no useful purpose except to become "a shady resort for Forest Comissioners and nonproducing loafers." The Placer Herald entered similar protests intimating that "a sporting organization of San Francisco" had no right to create a game preserve and recreational playground at the expense of the local economy (3/19/1898).

In part to placate local interests, the final proposal of the General Land Office was for a much smaller withdrawal of land, excluding much of the area outside the basin to the west. On April 13, 1899, President William McKinley signed a proclamation for a "forestry reserve and public park" setting aside 136,335 acres, or less than half the area proposed in 1896 by the Sierra Club. The Lake Tahoe Forest Reserve included 55 miles of shoreline and other land in the southwest part of the basin (Pisani 1977: 14). Creation of the reserve did not end the controversy. As events would soon show, concern for watershed protection in the northern Sierra overshadowed interest in protection of limited acreage within the basin. Farmers dependent on irrigation in the Central Valley, John Muir, Theodore P. Lukens and other wilderness preservationists joined forces as champions of watershed protection.

Throughout 1899, leaders of the California Water and Forest Association, the State Board of Trade, the Sierra Club, and other influential organizations pushed for expansion of the Lake Tahoe Forest Reserve (Strong 1981: 33-4). William Mills of the Central Pacific favored including the headwaters of the American River and the western slope of the Northern Sierra in the reserve to assure hydroelectric power and irrigation water to the Central Valley (San Francisco Post 6/21/1899). Charles Wolcott, director of the U.S.G.S., favored expansion. Senator William Stewart of Nevada lent his support for withdrawal of additional lands from public entry as part of a plan to deliver surplus water in the Tahoe-Truckee catchment basin to arid lands in Nevada and to provide hydroelectric power for homes and industries in Reno (Pisani 1975: 129-133, 147-151). Support also came from interests behind the nascant tourist industry at various Sierra alpine lakes who heartily welcomed the enhanced scenic beauty promised by establishment of forest reservations.

Several interest groups objected to the establishment of a Tahoe National Park. The most vociferous opposition initially came from county officials, dairy and stock raising interests, lumber companies and mining interests. These same interests opposed enlargement of the existing forest reserve. Forest Superintendent Charles S. Newhall tried to temper their hostility by explaining that unlike the "prohibitive" administration of a National Park, reserve status would allow for commercial development by regulating and protecting the resources under principles of scientific management. The confusion persisted. Other critics of the bill to enlarge the Tahoe reserve recognized other hidden dangers. Any enlargement would include thousands of acres of land owned by the Central Pacific Railroad, many of which were cut-over or rocky, barren and precipitous land. Lumber companies also owned vast tracts of logged-over land under the Lieu Land Act of 1897, those owning property within the boundaries of a national forest could exchange for land of equal size elsewhere on the public domain. The San Francisco Examiner, in a highly influential article, condemned expansion of the reserve, charging it would result "in the gift of thousands and tens of thousands of acres of the choicest public lands — timber, oil, mineral, agricultural and grazing — to private parties" (2/27/1900).

Forestry agents continued to study the issue of an expanded Tahoe Reserve. Charles H. Shinn inspected the area for the Bureau of Forestry in 1902, noting severe overgrazing and fire protection problems. He advocated expanding the reserve several times its existing size to more than 900,000 acres. The following year Albert Potter, the bureau's range expert, conducted an inspection tour of existing and proposed reserves in California (Strong 1981: 87-88).

The conservation movement of the early twentieth century is most closely identified with Theodore Roosevelt's brand of Progressivism and his shrewd appointments to key positions. The focal point of the Progressive conservationists was land — and the timber, water and grass upon it. The first conservation issues to which Roosevelt devoted himself was irrigation, or the "reclamation of arid lands." In Roosevelt's opinion, the interest of irrigation in California demanded an extension of the forest reserve system. Gifford Pinchot was of the same mind. In 1905 when Congress shifted administration of the forest reserves to the Department of Agriculture, the forests came under Pinchot's charge. With Pinchot as Chief Forester and a president in the White House who actively supported conservation measures, expansion of California's forest reserves seemed inevitable. When Congress repealed the lieu land law that same year, the last blockade to expansion was removed (Strong 1981: 87-89).

In 1905, Roosevelt established six new forest reserves in Northern California: Klamath, Lassen Peak, Plumas, Shasta, Trinity and Yuba. He also greatly enlarged the Tahoe Forest Reserve. Local newspapers did not voice opposition to the expansion. One paper noted that the enlarged Tahoe reserve would be beneficial to the mining interest by furnishing a permanent supply of timber (Mountain Messenger 10/04/05). Subsequently, the national forests underwent many name and boundary changes. In 1906, Roosevelt consolidated the Yuba forest reserve which included lands within the watershed of the forks of the Yuba River, with the Tahoe into the Tahoe National Forest.

Four years later, his successor President Taft, created the El Dorado National Forest from parts of the Stanislaus and the Tahoe National forests. Thus, after 1910 the southern boundary of the Tahoe forest extended to the Middle American and Rubicon rivers. After World War II, lands within Nevada were transferred to the Toiyabe National Forest (U.S.F.S., Proclamation Map Atlas, Tahoe National Forest).

Administration of Tahoe National Forest Lands, 1906-1940.

General administrative programs in office and field had to be set up once the National Forest was created. This task fell to Madison B. Elliott, the first supervisor of the Tahoe National Forest. Appointed as a district forester by Roosevelt in 1904, Elliott had assisted in setting up the basic administrative organization for the soon to be created forest reserves in Northern California. He was an educated man, a college graduate and former principal of the Lakeport School. As with most forest service appointees in those early days, his most important qualifications were his practical experience and strength of character. Elliott was a native Californian, born in 1869 to a ranching family who ran cattle in the foothill and mountain country north of Clear Lake, in Lake County. As a young man he established his own ranching business in the vicinity and for some years operated a sawmill. His major responsibilities in his three years as supervisor were to recruit rangers, explore and map the new forest lands, and initiate the routine business of implementing forest programs (Grass Valley Union 10/15/55).

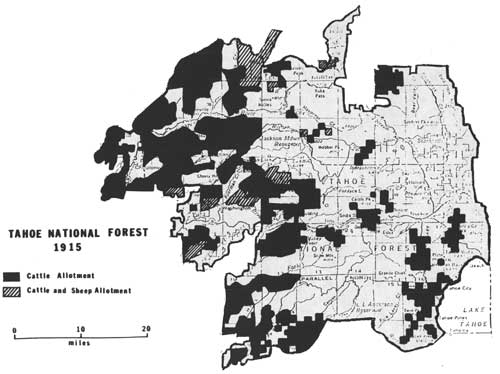

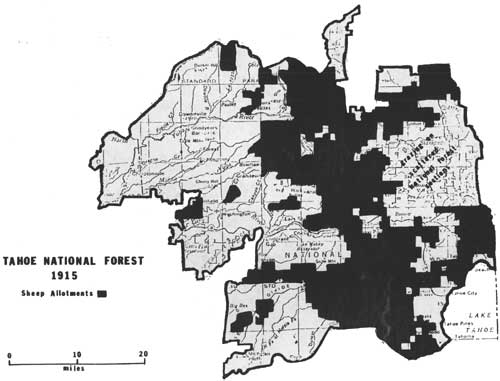

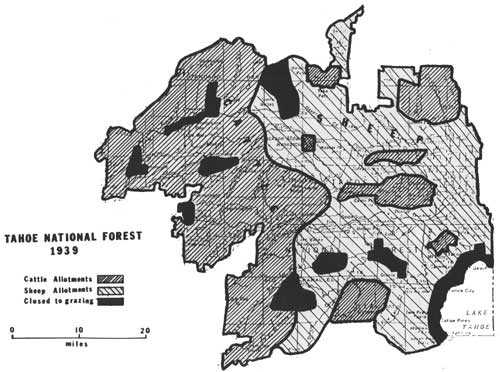

Mapping and bringing under even rudimentary management the over one million acres in the Tahoe National Forest was a great burden for a small staff. The forest officials dealt first with what they saw as the greatest problems. There were few timber sales in the first few years of Forest Service management. The range offered more pressing problems than the administration of timber resources and Elliott had much success in establishing a cooperative range program with local stockmen. Overgrazing had been a perennial problem in California's forest range so the concept of allotment itself was not debated seriously. Stockmen realized that open ranges required a quota system. Beginning in 1907, Elliott called together stock grazers in the Tahoe National Forest to an annual convention where permits were issued for the following season and general range problems were discussed. The Grass Valley Morning Union reported in 1908 that 230 stockmen attended the second convention, all seeking permits to graze on the National Forest (11/10/08). The interests of the stockraisers were various. Among the issues addressed by Elliott, who served as chairman of the meetings, were range improvements; handling of and caring for stock; building fences, corrals, cabins and roads on the forest; reseeding ranges; poisons and predatory animal reduction; and water development (Morning Union 11/11/08).

|

| GOLD LAKE RANGER STATION CA. 1922 |

|

| SIERRA VALLEY RANGER STATION, 1915 |

Overall, Forest Service range policy was favorably received among the stockmen who used the forest for summer pasture. Of sixty-four stockmen polled at the Nevada City convention in 1908, sixty responded that the method of grazing under government regulation was preferable to the old ways (Morning Union 11/22/08). In recognition of his valuable services on the Tahoe, Elliott received a promotion to the regional office in San Francisco as chief of grazing.

Elliott was somewhat less successful in his public relations with the press and local public officials who remained skeptical that the National Forests would accommodate homeseekers, prospectors, farmers and lumbermen. The controversy was touched off by Elliott's proposed western extension of the forest into an area within one mile of Nevada City on the north and two miles to the east. The Banner Hill, Blue Tent, Crystal Springs, Greenhorn Creek and Willow Valley mining districts, as well as the towns of Sweetland, Sebastapol, North San Juan, Cherokee, Badger Hill, Columbia, Lake City, Relief Hill, and North Bloomfield would have all fallen within the boundary of the expanded Forest (Morning Union 11/21/08). The mining interests of the region feared that the large number of unpatented mining claims in the affected territory and sizeable tracts of land open for mining locating would be hampered by governmental restriction. Others argued that a considerable amount of the land was suitable for growing fruit, and therefore unfit for inclusion in a National Forest. In spite of Pinchot's own reassurances published in the Daily Democrat that mining claims would not be affected adversely, Elliott was unable to convince local residents. Acting on his constituent's petitions against the western extension, Congressman Englebright successfully killed the proposal (Morning Union, 11/25/08).

During the long superintendency of Richard L. P. Bigelow (1908-1936), the concept of multiple-use management was introduced as forest officials tried to integrate the functions of watershed protection, grazing, mining and recreational development with timber management and sale. Bigelow began working for the Forest Service in 1902 under Charles S. Newhall, Superintendent of Forest Reserves in California. Bigelow was born in Oakland in 1874, son of a pioneer in the San Francisco fire insurance business. As a young man of eighteen, he left the city for Fresno County where he took up stockraising and ranching until his appointment as forest ranger in 1902 on the Sierra Reserve (Woolbridge 1931: 207-8), While there, he gained experience in fire fighting, boundary line surveys, trail work, timber cruising, issuing use permits, thinning out forests, and regulation of transient sheep grazing on the reserve. Bigelow served as Supervisor of the Trinity, Klamath, and Shasta National forests before accepting a similar appointment to the Tahoe (Grass Valley Union 10/22/55).

Several important personages in American forest history worked on the Tahoe National Forest during the Bigelow years. M.B. Pratt, State Forester, worked as his Forest Assistant; Evan W. Kelly, a world-renowned forester, was a ranger; W. B. Greely, Chief Forester of the USFS, was a scaler, as was DeWitt Nelson, the future Supervisor of the Tahoe National Forest and Director of the California State Department of Natural Resources (Grass Valley Union 10/22/55; Fry 1976). Although many of the management functions during the Bigelow years were custodial in nature, the staff had to delicately balance and develop policies for compatible uses and to deal with constant pressure by special-interest groups, mainly representing timber, water, grazing, and mining. Recreational demand and road improvements were substantially accelerated after use of the automobile became widespread in the 1920s.

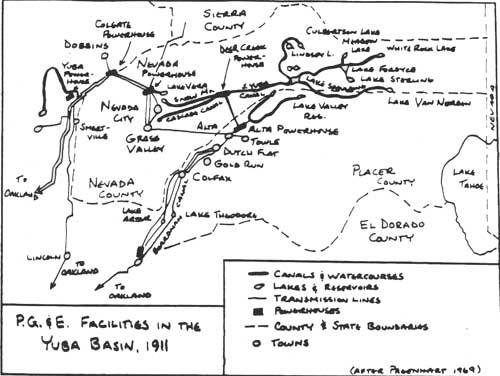

By the mid-1920s, power development was one of the chief resources on the Forest as the numerous sites on lakes, reservoirs, and rivers transmitted the hydroelectric power to San Francisco and other cities. Water from the forest also irrigated thousands of acres of orchard lands in the foothills and valley, and was transported to cities for domestic consumption. Commercial timber harvests hovered at about the ten million board foot per year level. Stockmen ran some 13,000 head of cattle and about 100,000 sheep on the forest range lands. With the completion of trans-Sierra state highways came summer home developments, roadside garages, stores, summer resorts, and private and public campsites (Woolbridge 1931: 207-209). During the early decades of Forest Service management receipts from timber sales, grazing permits, recreational leases, and special use permits regularly totaled less than expenditures. The forest was seriously understaffed with just twenty year-round employees and 30 seasonal men employed on the average in 1924. Not until the New Deal planning and programs were instituted were manpower and finances available in quantities large enough to tackle large-scale tasks in a comprehensive manner. Their availability would have a profound, positive effect on professionalism and resource planning within the Service.

To manage the many diverse resources on the Tahoe National Forest compatibly required careful planning, particularly when dealing with long-term ventures such as timber plans or expensive projects such as road building. On the other hand, plans had to be flexible to accommodate abrupt and unexpected shifts in priority. Under Bigelow's administration, plans had been laid out that would be implemented as New Deal monies became available during the 1930s. During this decade a wide variety of physical improvements were made on the forest: ranger stations, lookout towers, telephone lines, roads and trails, and campgrounds (Meggers/Nelson Interview 1982).

The task of implementing the Civilian Conservation Corp and other New Deal assignments on the Tahoe National Forest fell largely on DeWitt Nelson. Unlike the first two supervisors Nelson was a professionally trained forester, but he also worked his way up the ladder within the Forest Service step-by-step. He graduated from Iowa State College with a bachelor's degree in Forestry in 1924. In the spring of 1925 he passed the federal civil service examination for Junior Forester in the U S. Forest Service and was assigned to a position as scaler on a Hobart Mills timber sale in the Tahoe National Forest. The following season Supervisor Bigelow appointed him ranger on the Truckee District. Between 1927 and 1935, Nelson served as assistant supervisor and then supervisor in three different forests in California. He served two years (1935-36) as CCC liasion officer for the 9th Corps Area Military Command in San Francisco, representing all the technical services of the CCC program for the army in ten western states. In May of 1936, he left the liasion post and reported back to Nevada City, this time as Supervisor of the Tahoe National Forest (Nelson Interview 1982; Fry 1976: 15-68). A dramatic rise in the price of gold and the institution of CCC programs had immediate economic and social impacts that were felt in all the communities across the Tahoe National Forest. In addition to the young men from towns and cities who were transferred to working in the healthy forest environment came an equally large number of poverty-stricken victims of the Depression. They squatted on the public lands, took up residence in forest campgrounds, and tried their hand at prospecting for gold to eke out a living until World War II brought employment opportunities elsewhere.

Logging on the Tahoe National Forest, 1906-1940.

Forest Service policy required foresters to exercise balanced judgment in handling timber sales. Chief forester Pinchot set the tone for the conservationist policy of "wise use" and "scientific management" for the nation's long-lived material prosperity. His multiple use concept in the management of National Forests required the protection of watershed and grazing rights to be integrated with timber sales and management. Yet the sales program had to take into consideration local conditions and the structure of the lumber industry. Timber management was to be geared toward stabilizing local industry and benefitting it in the long-run through wise resource planning.

During the first few years of federal management, timber sales were sluggish in the Tahoe National Forest. In order to develop a suitable timber sales program, Supervisor Bigelow instructed his Assistant Forester, M.B. Pratt, to prepare a study of sawmills on the forest. His findings revealed significant changes had been occuring in the industry since the last decade of the nineteenth century. In general, the trend had been away from many small independent mills toward concentration of ownership and vertical integration of the industry.

The first sawmills in the region grew up in association with the gold rush mining camps. They were small mills producing timber for local demand. Pratt reported that on the Foresthill Divide there were eleven sawmills in the early 1850s. The number had fallen to five by 1876, the decrease largely being explained by the decline in mining activity. Only one mill operated on the divide by 1910; however, unlike the earlier mills this one was operated by a large lumber company that owned substantial timber lands and exported its products to outside markets (Pratt 1910: 169).

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, California lumbermen found themselves caught in a squeeze between rising operating costs and relatively stable prices paid by consumers of their products. Between the late 1890s and World War I, annual cut of pine trees in California nearly doubled. Under the Timber and Stone Act huge tracts of timberland had been fraudulently acquired by large investors who erected large sawmills of 50,000 or more board feet daily capacity. The increase in production prevented significant rise in prices. Meanwhile, the cost of production soared. Logging operations required increasingly complex machinery. Donkey engines replaced oxen in yarding felled trees. In the mills single and double-band saws replaced the old circular saws. These mechanical engineering improvements eventually increased profits, but the capital outlay was tremendous. The initial impact was detrimental as the innovations raised operating costs significantly. According to a 1915 report by forestry expert Swift Berry, the prices pine lumber companies received for their products barely covered the costs of production (Berry 1915: 226).

By 1910, on the Tahoe National Forest, there were only thirty-three mills cutting timber. Of these, twenty-nine were independent firms and the remaining four cut timber for the large mills. Nine mills had a capacity of 50,000 board feet or more. Twenty mills had a capacity ranging from 5,000 to 50,000 board feet, but averaged approximately 15,000 board feet. Of these twenty mills, one-half cut for local demand, five operated in conjunction with mines and ditch companies, and five competed in the marketplace with the nine large mills. In 1910. approximately sixty percent of the land lying within the exterior boundary of the Tahoe National Forest was patented land. Although the vast majority of the timber harvested was taken from private holdings, six of the smaller-sized mills depended wholly upon the National Forest for the timber they cut (Pratt 1910: 169-73).

The large lumber companies responded to narrowing profit margins by restructuring their firms. One response was vertical integration. The mills hired their own fallers and yarded their own logs. Independently operated flumes gave way to company-owned railroads as the chief means of carrying lumber to the mill. Firms that produced only unfinished timber expanded their operations. Large mills operated drying kilns, ran box factories, planing mills, and sash and door plants. Expanded operations allowed them to use poorer grades of pine and white fir. Waste products such as sawdust even found a profitable market. Company officials expanded the size of their firms to take advantage of economies of scale. During the 1910s, reduced profits had caused many small firms to merge or quit business altogether. On a statewide basis, small mills with circular or single band saws cut much of California's lumber in 1900; two decades later, large mills using double-band saws dominated the industry. The number of sawmills fell by twenty percent during this 20 year interval and by 1920 over eighty-five percent of the state's lumber was cut by mills with an annual output of more than ten million board feet (Blackford 1977: 60-73; Pratt 1910: 170).

The changing logging equipment, harvesting methods used by lumber companies, and scale of operations caused timber managers on the Tahoe National Forest to adjust their sale regulations. The Forest, in 1911, advertised for bids on a seventy-three million board feet saw timber sale, providing a ten year period for removal of the timber. It called for construction of twenty miles of railroad line and an adjustment in stumpage costs after a five year period (Pioneer Western Lumberman 1/15/12: 11). The announcement inaugurated an important departure from past policy. The National Forest had large quantities of timber, but it was not easily accessible. Timber purchasers had to make heavy capital investments in transportation facilities to take trees from the stump, to the rail line, and finally to the mill. Under these circumstances only large-scale timber sales requiring a number of years to complete, were attractive to the local lumber companies (Ayers 1958: 33-34).

Until 1911, Forest Service policy was to oppose long contracts. Sales of timber were proportional to existing supply and demand and were designed to encourage sales to small purchasers. The vast majority of the early sales were of this type. Since stumpage prices were rising, forest officials saw long contracts based on current prices as a danger for it might encourage speculation and give unfair advantages to large companies. Prior to 1911, no sales were let for a period extending over five years. Conditions in the lumber industry made the policy impractical. The new plan allowing longer operations with periodic revision of stumpage rates was a useful innovation that protected the public and small operators while opening the forests to the large concerns (Pioneer Western Lumberman 1/15/12: 11).

In 1926, Supervisor Bigelow estimated that in the first twenty years of timber management the Tahoe National Forest had sold and permitted cutting of approximately 185 million board feet of timber, an average of about 9.25 million annually. Timber sales ranged in amounts from a few thousand feet up to whatever amount was warranted considering the investment required for constructing rails or other means of transportation into comparatively inaccessible regions. The Tahoe forest permitted cutting on 14,000 acres of government land in 1925, containing an estimated seventeen million board feet. Bigelow estimated that there were seven billion board feet of saw timber remaining on federal lands. Following the Forest Service policy of marking trees to ensure a second cut within 30 to 40 years, reforestation of the cut-over land would provide timber for future generations (Bigelow 1926: 12).

On private holdings the rate of timber consumption far surpassed that on the National Forest properties. The forest supervisor estimated existing private timber stands at 6 billion board feet in 1925 with timber being cut at a rate of 65 million board feet annually (Bigelow 1926: 121). Except in times of high prices such as during World War I, there was little attempt on the part of lumbermen to engage in scientific forestry practices. "They were concerned with getting the timber out and producing the most profit they could," recalls a Forest Service scaler. By 1910 most of the timber in the Tahoe Truckee basin was stripped off; by then the focus of operating had shifted north into the region north and east of the Little Truckee River and into Sierra Valley. Within 25 years, the lumber companies had denuded their properties. They eventually sold much of their cut-over acreage to the USFS during the depression years as the companies could not afford to assume the heavy tax burden on non-harvestable timber lands (Nelson Interview 1982).

Prior to the 1890s in the pine regions of California, the typical logging operation used oxen to haul logs from the stump to the yard. From this temporary storage area lumbermen transported their timber by raft, river drive, chute, flume, wagon, or railroad to the mill site. Yarding with bull teams was a slow, cumbersome, expensive process. Animals were difficult to maneuver in tight places, or where footing was poor. Where ground conditions were rough or slopes steep, they could not operate at all. If steam power could be utilized for yarding, many problems could be overcome.

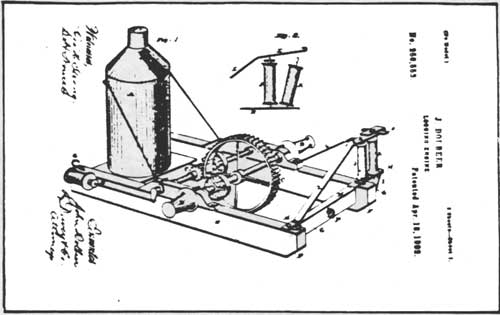

The invention of the steam skidder of the variety used on the West Coast may be found in the granting of a patent in 1882 to John Dolbeer for a "Logging Engine." A seafaring man turned logger, Dolbeer drew his inspiration for the logging engine from machinery commonly used along the waterfront to load and unload cargo between ship and wharf. The original steam donkey contained a small engine with upright boiler and contained no winching drums at all. The machine "featured a horizontal shaft with gypsies at both ends. It had a snatch block fairlead mounted at the head of the frame at one corner to guide the hauling line to the gypsy behind it" (Tooker 1970: 23-24). This side-spool construction proved impractical and the elaborate systems of pulleys required to yard logs reduced the pulling power of the machine. Dolbeer improved his machine in 1883, developing what became the Dolbeer Donkey. In contrast to his earlier machine, this was a capstan type with the vertical spindle-mounted drum driven by steam power (IBID: 24-25).

|

|

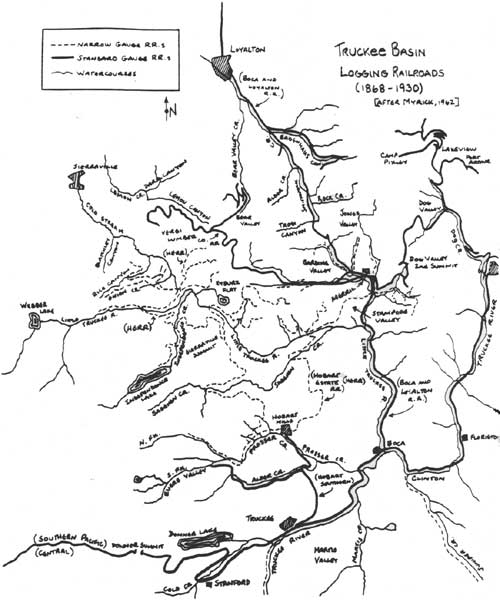

Truckee Basin Logging Railroads (1868-1930) (after Myrick, 1962) (click on image for a PDF version) |

|

| LOGGING ENGINE |

|

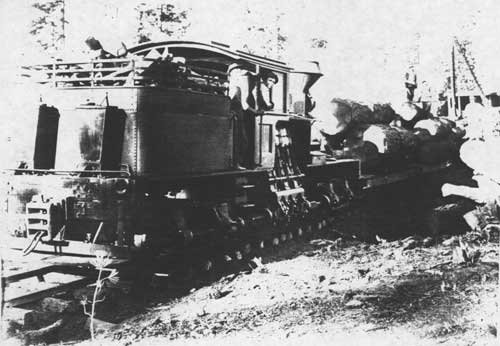

| STEAM DONKEY |

Two problems plagued Dolbeer's invention. First, in the early 1880s available steel rope could not stand up to the forces exerted on it in logging operations and snapped too easily. Hemp rope stretched a great deal under strain and manila rope's practical limit was 500 feet at best. Second, Dolbeer's engine still had no storage drum, so the rope had to be coiled and uncoiled manually during yarding. This slowed operations considerably. After 1890 the quality of steel cable improved steadily making it possible to skid logs at a distance of over 1,000 feet (IBID: 27-28). Also in the 1890s, David Evans of the Excelsior Redwood Company near Eureka put into operation the first bull donkey which had three storage drums around which the haul, trip and straw lines were wound (Rutledge 1970: 27).

More powerful machines followed Evan's donkey — all had drums and large vertical boilers. With more powerful engines and reliable wire rope, the donkeys could take over the skidding from the tree falling area to the landing where the logs were loaded on railroad cars. Gradually yarding as a separate operation distinct from skidding to the landing was eliminated.

In his History of Timber Management in the California National Forests (1958: 38), R. W. Ayers describes the typical donkey logging layout as it existed around 1907. The lumber company would start by laying cables along a main chute running up a gulch from one to four thousand feet. At the bottom of the chute would be a bull donkey or road engine. The bull donkey was different than the slack rope skidder (or yarding donkey) in that it did not go to the stump directly but simply hauled logs brought to it by other means. It was the main haul engine, and as such it took the place of trains, flumes, or sled roads. In a small logging operation the bull donkey might be at the mill itself; in operations distant from the mill it was placed at the main railroad with a loading engine.

At appropriate places along the main chute, yarding donkeys were placed to haul logs from the stump to the chute for a distance of 200 to 1,800 feet. The yarders varied in form from merely the bare engine with the necessary pulleys, cables and fittings to a completely portable model assembled on sled skids designed to allow the machine to pull itself along by winching onto stumps or trees (Williams 1908: 15) Close to the yarders would be a swing donkey to take logs from the yarder and drag them through a "frog" or switch into the main chute. Logs were collected in trains at each frog thereby providing a large load for the bull donkey to take down the chute to the railroad or mill site (Ayers 1958: 38).

High-lead yarding which used cables attached to spar trees was introduced to California from the Pacific Northwest. As the rigging was expensive and difficult to set up, only where timber was extremely valuable was this method employed. The high-lead method was not used extensively in California, but where it was found practical Forest Service regulations limited the height on the lead to a maximum of 35 feet so as to minimize scarring the ground. This technique became known as the "modified lead" method (Show 1926: 26-32).

Throughout the 1920s, almost all of the large-scale companies on the Tahoe National Forest logged with donkey engines and railroads. There were some exceptions. The Davies-Johnson, Calpine and Loyalton lumber companies experimented with tractor logging as early as 1924. Of course, the first gas tractors used in California were built for agricultural use in the Great Central Valley. It was not long, however, before they were adapted to the lumber industry. Ayers, in his forest timber management history, implies that tractors were probably adopted first by smaller-scale operators who were still using big wheels and horses in the early twenties. Fuel was cheap and gasoline powered engines cut log handling costs. Furthermore, tractors could log slopes as steep as 30 percent, whereas wheels and horses were limited to 12 percent grades. By the 1930s tractors came into more general use (Ayers 1958: 35-37; Meggers/Nelson Interview 1982).

On the west side of the Tahoe National Forest where sawmills tended to be smaller and produced for local consumption, the men who worked in the mill and Forest were generally settled members of the community in nearby towns. On the eastern side of the Forest where the majority of the logging took place from 1906 to 1940, the situation was quite different. Those who worked in the mills at Loyalton, Calpine, Hobart, Verdi, or Floriston were more likely to be year-round residents of those towns. However, those who labored in the forests, employed on a seasonal basis, constituted a substantially larger floating population. Supervisor Bigelow, in April of 1912, estimated the resident population of lumbermen and millmen within the Forest boundaries at only twenty-eight whereas the "nomadic" loggers almost reached 2,000 (Bigelow 1913: 1). These men lived in the logging camps, temporary forest communities established by lumber companies near the scene of each season's cutting operations. Oftentimes a logger would remain in a camp only long enough to earn a grubstake. "The local people had a saying," recalls ex-supervisor DeWitt Nelson, "any lumber camp had at least three people in it: one working, one coming and one going" (Nelson Interview 1982).

The most successful lumber companies of the twentieth century were those that expanded their operations to include all phases of production, from cutting the trees to producing finished products. Besides handling their own marketing, milling, and manufacturing, these firms took over the production — and often transportation — of their raw materials. This expanded form of industrial operations was necessary in an enterprise whose raw materials came from the ground and where limited resources could be controlled by a few firms. To gain an assured source of supply was essential to the manufacturer.

The three biggest lumber companies on the Tahoe National Forest were vertically integrated firms with substantial land holdings. The Verdi Lumber Company, in 1912, held 14,080 acres in eastern Sierra County. Northwest of its mill site, the Hobart Estate Company owned some 65,680 acres of timberland. The Floriston Pulp and Paper Company's holdings amounted to 32,380 acres (Knowles 1942: 43, 50). In common with the other large mills on the Tahoe National Forest, these manufacturing plants had direct connections to a transcontinental rail system that facilitated broad distribution of their finished products.

|

| STEAM DONKEY YARDING, CA. 1900 |

|

| RAILROAD LOGGING ENGINE, CARS; LOADER IN BACKGROUND. NOTE TEMPORARY NATURE OF ROADBED, TIES. |

For about a quarter century, Oliver Lonkey had been active in the Sierra lumber business before incorporating the Verdi Lumber Company in 1900. Since the 1880s, his mills and box factory at Verdi had been supplied with lumber from Dog Valley, first through a long winding flume and later by three-wheeled steam vehicles. About the time Lonkey decided to incorporate the Verdi Lumber Company undertook construction of a railroad into Dog Valley. By about 1905 the company had cut-over all of the Dog Valley drainage. In the final year of operations they cut nine million board feet from their chief camp, Port Arthur, at the north end of the valley (Knowles 1942: 44-45; Bigelow 1926: 10).

Once the timber was exhausted in Dog Valley, the company extended its railroad lines to Long Valley Canyon near Purdy and over Dog Valley Second Summit to Merrill in Sardine Valley. Here it crossed the trackage of the Boca and Loyalton Railroad and pushed on west along Davies Creek into the mountains. In a little over ten years, the Verdi Lumber Company had stripped its vast acreage of all timber:

By the summer of 1912 the company's standard gauge railroad . . . was extended to their timber tracts in eastern Sierra County which comprised an area of 14,080 acres, 9,440 of which they had denuded even to the seed trees during 1912. Two camps were then established to take off the remaining 4,640 acres: Camp No. 1, situated on the line between sections 2 and 3 Township 19 North, Range 17 East and Camp No. 2 in Section 1, Township 20 North, Range 17 East. The bulk of the remaining 4,640 acres lay between these two camps on the rugged land between Merrill Creek and Dog Valley. It had to be logged with donkey engines. The Company finished clearing this during 1913. (Knowles 1942: 45)

Faced with timber shortages, the Verdi Lumber Company purchased the first long-term timber contract from the Tahoe National Forest in 1911 and two years later absorbed the Tonopah Lumber Company and its 40,000 acre timber holdings in Sierra and Washoe counties. Lemon Canyon then became the major site of timber cutting. The company purchased property and timber rights in 1911 and began cutting four years later. Lemon Valley remained the chief cutting site of the Verdi Company through the 1926 season. The firm constructed a railroad spur line into the hills above Bear Valley in 1917. After this area was logged, the company timbermen and railroads branched out westward from Davies Creek into the hills on the south side of Lemon Canyon. Logging continued for five years there and then switched to the north slope of the canyon keeping the railroad supplied for several more years (Jackson 1967: 52-53; Bigelow 1929). On the rail lines laid after 1920 in the Lemon Valley area, the Verdi Company's roads possessed a unique feature, the "Revert Tie":

During 1920 the President of the Verdi Lumber Company, A. Revert, invented a new type of railroad tie, designed to effect considerable saving in timber. The 'Revert Tie' was built from a number of small pieces of timber all held firmly together by a series of wooden dowels. By the spring of 1920 the company was using these ties on its logging railroad. (Knowles 1942: 48)

The sawmill, storage yard, and roundhouse at Verdi burnt in 1926. The company abandoned its mill, sold its remaining timber lands, and tore up the tracks of its railroad. Nearly all the rails were removed and the roadbed abandoned in the summer of 1927 when the Hobart Estate bought the right-of-way to several miles of the old Verdi Company track (Jackson 1967: 62; Myrick 1962: 441).

By the mid-1890s, the Sierra Nevada Wood and Lumber Company had concluded operations at Lake Tahoe and moved its mill to the Hobart mill site seven miles north of Truckee. Equipped with two band-saws and a 52 inch circular saw, the mill had a capacity of about 175,000 feet per day. The new plant also boasted a box factory capable of turning out 9,000 boxes a day, a sash and door mill, a planing mill, and a modern machine shop. A boarding house, dwellings for employees, post office, and a company store were built adjacent to the plant in 1900. In subsequent years, the company added a hotel, school, and express office. Most of the 500 men employed at the mills in 1924 lived in the company town of Hobart Mills. The town remained intact until 1958 (Larder and Brock 1924: 437; Knowles 1942: 47-48).

The company built a standard gauge railroad from the mills to Truckee during 1896 and covered it with snow sheds to allow trains to operate during the winter months. Over this line finished products and sawed timber were shipped to the Southern Pacific main line. The Hobart company operated a small sawmill in Alder Creek in 1901; however, from the time of its establishment at Hobart Mills in 1896 until its winding up operations forty years later, most of the timber company's cutting was done in Sierra County. Demands for sugar pine doors, boxes to ship California's agricultural products, and construction timbers for the Southern Pacific Railroad kept the mills busy. The output of the mills during the period 1900-1920 varied from a high of over fifty million feet in 1906 to a low of twenty-two million in 1918. Annual cuts during the 1920s were somewhat lower ranging from 20-28 million feet (Knowles 1942: 48-49).

From 1909 when Bigelow made the first sale to Hobart Mills to 1936 the company cut some 29.5 million board feet from the Tahoe National Forest, or about three percent of the company's total cut. Most of the Forest's parcels were logged by Hobart after 1917 (Bigelow 1936: 3).

The first line of Hobart's narrow gauge railroad was built up Sagehen Creek to its junction with the Little Truckee River. A second line carried timber from Carpenter Valley down Prosser Creek. By 1917, the company had built twenty miles of track, extending lines into the Independence Creek and Onion Creek Valley. The narrow gauge line from Hobart to the confluence of Sagehen Creek and the Little Truckee was rebuilt to sturdier specifications around 1920. During the following decade, construction was extended to the northeast to Merrill, at Davis Creek, and on north to Sardine Valley, with branches extending in all directions to new timber areas (Jackson 1967a: 34). Ten miles of narrow gauge track were added to the system between 1917 and 1922 when some twelve donkey engines were working to keep the Hobart Mill saws supplied. Many of the roadbeds of the abandoned Boca and Loyalton (1916) and Verdi Lumber Company (1927) railroads were used again by the narrow gauge. Around 1928, Hobart began testing tractor logging. Each year caterpillars replaced some of the mill's Willamette donkeys. The company, in 1934, had six gasoline logging tractors operating on the Tahoe National Forest (Knowles 1942: 49; Myrick 1962: 441). Two years later, Hobart Mills ceased operations. During their forty years of operation they had cut about one billion board feet of lumber. The USFS purchased the cut-over lands of the Hobart Estate Company under provisions of the Weeks Act (Nelson Interview 1982).

In 1899, San Francisco capitalists, funded primarily by the Fleischacker interests, built a pulp and paper mill at Floriston. When the plant was completed the following year it was the second largest paper mill in the United States, and the only such mill in the state. The company owned a 14,000 acre tract of timberland surrounding the plant and controlled an additional 18,000 acres of timberland by 1914 in the region north and northeast of Lake Tahoe and south of the Southern Pacific Railroad. For use in the company's paper mill some 20,000 cords of red fir and white fir were cut annually from these lands (Mills 1914: 679; Knowles 1942: 50).

Whereas the Floriston mill used only fir in its operations, all of the other companies in the region cut pine trees. The paper company worked out agreements to acquire the fir species from the timberlands of other companies such as the Hobart Estates Company and the Loyalton Lumber Company. D. J. Smith cut some 50,000 cords of wood for the Floriston mill from his timberlands in Placer County on Coldstream Creek. The Roberts Lumber Company, in 1909-10, supplied the mill with 20,000 cords of fir from their Truckee and Anderson tracts that had been previously stripped of their pine trees (Knowles 1942: 50).

On the average, the company employed about 150 workers at its Floriston mill and produced from 7,000 to 8,500 tons of paper annually. An Oregon company, Crown-Columbia Paper, bought the mill and its timberlands. Within two years nearly all of its 32,000 acres of timberland were stripped of its fir trees. During an era when other companies were employing steam donkeys and railroads, the logging methods of the paper company appeared very outdated:

They began cutting the logs in October in order that they might season for 6 or 8 months. All trees were cut to a diameter of 12 inches and each tree was cut to a 4 to 6 inch top diameter. The system of winter cutting, however, made it necessary to leave stumps as high as 6 feet so that many cords were thus left in the woods in this form. In summer, or as early as the weather permitted, the cut logs, thoroughly seasoned, were packed on mules or by horse teams and wagons to the company's flume which conveyed them to the mill at Floriston. (IBID: 50)

In 1908, a cooperative agreement was worked out between the Crown-Columbia Paper Company and the USFS to control forest fires on the private and Forest lands being logged by the paper company north of Lake Tahoe and in the Duffy's Camp vicinity. Under the agreement, fire patrols were established on the company lands during the dry season. The headquarters for the patrolmen were in the woods where two-room log and shake cabins were built to provide housing. Between 1909 and 1914 five patrolmen's cabins were built and three fenced pastures set aside to provide feed for the patrolmen's horses. As part of the program, the company and the Forest Service cooperated in constructing fifty miles of telephone line and thirty-six miles of trail to facilitate easy communication with the patrolmen (Mills 1914: 679-83).

The paper company shifted its logging operations to Browns Camp near Soda Springs and to Truckee Lumber Company tracts in Placer County between 1914 and 1921. After exhausting these supplies, the company moved to Donner Lake where it operated a tramway on the south side of the lake to haul wood down the steep mountain slopes to the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks, where loggers loaded the cordwood for shipment by rail to Floriston. Later the company built a standard gauge line north of Donner on Alder Creek and into Evers Valley. The rail line was used in conjunction with the Hobart Estate Company, but was abandoned in the 1930s (Myrick 1962: 442-43; Knowles 1942: 50).

In the midst of Depression hard times, the Floriston mill folded up its operations. The company had exhausted its most readily available timber resources; the mill's efficiency, as well as its output, lagged behind the larger paper mills that had been built in the Pacific Northwest.

Several sawmills operated in the vicinity of Sierra Valley during the twentieth century. Up until 1928, seventeen different sawmills cut national forest timber from the Sierra Valley Working Circle (TNF: Management Plan 1928: 18). The Clover Lumber Company of Loyalton, a subsidiary of the Verdi Lumber Company, purchased the old Marsh mill in 1917. Its annual cut averaged about eight million feet, much of which came from the Badenoch Canyon region. Sardine Valley sawmills included those of Davies, on Davies Creek; Warren near the damsite on the Little Truckee; and Winnie Smith, on the Little Truckee just above Sagehen Creek. The Roberts Lumber Company, the Lewis Brothers California Lumber Company, and several other small sawmills logged along the line of the Boca and Loyalton Railroad, a road built to handle logging operations tributary to their right-of-way (Bigelow 1926: 10-11; Knowles 1942: 46). In 1907, the Boca and Loyalton had at least fifteen short spur lines into the forests where lumber camps had been located. Other spurs ran to the various mills. As the timberlands south of Loyalton were cut over, the Boca and Loyalton declined in importance. With the coming of the Western Pacific Railroad to Sierra Valley, competition for freight traffic accelerated the decline. The Boca and Loyalton operated at an annual loss of $41,000 to $52,000 between 1909 and 1912. Winter shipments were suspended in 1916 and soon thereafter all service on the line south of Loyalton was discontinued (Jackson 1967a: 50).

The sawmill at Calpine was perhaps the largest producer of the Sierra Valley region in the twenties and thirties. The community developed in 1919 or 1920 around the mill and yards of the Davies-Johnson Lumber Company, and was first known as McAlpine. The sawmill and box factory provided almost the entire economic support of the town. Approximately 150 men were employed at the mills in 1934 with an additional seventy-five on the payroll of the company performing other tasks. Much of the finished products from the mill were shipped to distant markets over a spur branch of the Western Pacific which terminated at Calpine. The lumber company closed its mill in 1939. It sold a portion of its property to J. J. Farrar who subdivided it and sold lots to people who incorporated the town of Calpine. The settlement became a vacation and retirement center (Mountain Messenger, Special Mining Edition, 7/29/34; Roth 1969: 8-9).

The logging history of the western side of the Tahoe National Forest continued to differ significantly from that of the Tahoe-Truckee and Sierra Valley regions. The sawmills produced for local consumption, providing lumber for town building, mining sites and other related mining developments. The Marsh sawmill which began production in the 1850s, was still running in 1926. Its logging operation and sawmill moved with the cutters, but its lumber yard remained in the same location near Nevada City where the first sawmill was constructed (Bigelow 1926: 11). The west-side sawmills usually operated on a seasonal basis, closing down with the winter snows each year (The Morning Union 11/25/08). Unlike east-side lumber operations, these companies did not build logging camps in the woods to house cutters. Loggers lived in nearby communities (Meggers Interview 1982).

After World War I, the local lumber business, dependent as it was on the strength of the mining industry, experienced a general state of decline. During the years 1918-1930, the output of gold mines dropped to their lowest point ever and people left the region in record numbers. Not until the mid-thirties did mining recover; when it did, huge orders for building materials arrived at the mills. The Grant and Heether Company of Camptonville for example, experienced sales ten times that of the previous years in the summer of 1934 after Roosevelt lifted the embargo on exportation of gold (Mountain Messenger 6/2/34). General prosperity continued through the war years.

Mining on the Tahoe National Forest, 1906-1940.

From the turn of the century to 1917, gold production statewide rose by about $4.2 million or approximately a twenty-five percent increase. Much of the increase can be attributed to the introduction of gold dredging in the late 1890s which accounted for ninety-one percent of the total amount recovered in 1922 from placer deposits. Since dredging took place in the lower foothill elevations, placer production within the Tahoe National Forest was fairly small. Exhaustion of river placers and stringent limitations placed on hydraulic debris left drift mining as the major form of exploiting the gravel deposits. Lode mining methods had improved significantly in the nineties with the introduction of new equipment; however, with other investment opportunities in California agriculture and Southern California real estate, little outside capital found its way into the deep mines in the early decades of this century (Clark 1970: 4-8).

Inflation following World War I reversed the rising trend of gold production and it continued to decline until the early 1930s. From 1933 to 1935, the price of gold was increased from $20.67 to $35 per fine ounce. The rise resulted in an immediate large increase in gold output and new exploration for the remainder of the decade. Economic conditions in the mining industry on the Tahoe National Forest tended to run, counter that of the rest of the state and nation. The post-World War I prosperity drew workers into California's urban-industrial centers. In agriculture, the war spurred expanded production. When peace came the economy of California had been lifted to a new plateau of production, distribution and consumption of both goods and services. With the price of gold fixed, inflation and high labor costs caused gold production to sink to its lowest level since 1849. Thus, in 1929 at the peak of the post-war boom, gold production had hit bottom (Jenkins 1948: 19).

From a production valued at $9.45 million statewide in 1930, gold output soared to nearly $51 million by the end of the decade. This was the most valuable annual output since 1856. Thousands of miners found new employment in the quartz mines at Grass Valley, Nevada City, Alleghany, and elsewhere (Clark 1970: 7-8). Still bearing millions of cubic feet of auriferous gravel-bearing hillsides, hydraulic mines closed since the mid-80s attracted mining engineers and investors. Thousands of urban unemployed rushed to the Sierra gold fields to prospect with pan and rocker along the various rivers and creeks. It was a movement reminiscent of the "days of '49." The resident population of the communities within the National Forest rose for the first time since the 1900 census. The rise was precipitous — some 42 percent during the 1930s (U. S. Census, Population 1900, 1930, 1940).

The revival of mining infused Forest communities with new life and stimulated non-mining industries such as logging and agriculture. Even a stable town such as Downieville, the county seat of Sierra County, barely survived the hard times of the twenties. Isolated from the outside world and faltering with the failure to attract capital investment in mining, the "somnolent mountain town" was "verging perilously toward the status of a 'ghost town'." With the revival of mining in 1934, the Mountain Messenger reported mining properties long idle were being examined by engineers and that the sleepy town "had suddenly been transformed into a bustling community" (7/29/34).

Under provisions of the 1897 act authorizing management of the reserves, vacant forest land was left open to mineral exploration and location under the general mining laws of the United States. The controlling legislation was the mining law of 1872 which permitted prospectors to enter public lands and stake a claim based on their discovery. The law did mandate that improvements be made on the claim, but did not require the mineral deposits to be actually mined, nor did the miner have to demonstrate the commercial viability of the proposed development. Claims with marginal or no value enabled miners to establish a surface right and with it the right to timber. Strategic mineral locations were sometimes used to control access to forest lands by preemption of the only site for road development (Steen 1976: 295-296).

The U. S. Forest Service permitted bonafide prospecting and mining on national forest lands with the exception of a few mineral resources which we not subject to location. Miners wishing to establish a claim had to file with the appropriate county agency; the Forest Service received no consistent report on the existence of locations in the Forest, nor notice as to whether they were being worked or abandoned. Ordinarily where claims were established, no mineral examination was made until application for a patent was filed. Miners were required to mark the corners of their claim and post a descriptive notice. An initial $500 investment work was required, with the Forest Service reserving the right to inspect the claim for the purposes of issuing a favorable or unfavorable report. If the finding was favorable a patent could be issued. The mining laws required a claimant to submit to county officials a yearly "proof of labor" affidavit stating that at least $100 was spent developing the claim (Friedhoff 1944: 4, 46; Steen 1976: 296).

There were several loopholes in the law which allowed for fraudulent mining claims. Proof of labor certificates were often not recorded, and failure to submit an annual report was not grounds for forfeiture. W. H. Friedhoff, a mineral examiner for the U. S. Forest Service in California with thirty-three years of experience in the field, estimated in 1944 that only about ten percent of mining claims on which proof of labor affidavits were recorded had $100 worth of work been done. Construction of houses, roads, trails, or other non-mining improvements were accepted as patent expenditures. Only in instances where claims were in material conflict with the public interest or interfered with Forest management and administration were they investigated. Where use and activities were not authorized by the mining laws, the validity of the claim was contested. In most cases, the Forest Service won its case against mining trespassers (Friedhoff 1944: 1-4, 9, 46).

Abuses of the mineral laws were common on the California national forests. From 1902 to 1918 lumber companies filed mining claims for no other purpose than to gain surface rights to the timberlands. The Forest Service contested a large number of these so called "sugar pine mining claims" which were particularly rampant in areas adjacent to railroad right-of-ways. After World War I, mountain road improvements provided enhanced opportunities for outdoor recreation. Some of the "gentlemen recreationists" filed mineral claims on which to build second home sites. This remained an on-going problem through the 1940s. During the Depression hordes of migratory small-scale placer miners descended on the forests. These "snipers" presented a major administrative problem, but given the pressing economic circumstances of the times their activities were tolerated. Throughout the period elderly persons and retirees have squatted on the public domain by taking up mining claims as a means of escaping the high cost of urban living (IBID: 34-5).

More than sixty-six square miles of national forest land in California between 1910 and 1938 was patented under the mining laws. Of the claims filed, 81.4 percent were approved. One hundred forty-four locations comprising 3,180 acres were contested. The Forest Service cancelled almost all of the contested claims for reasons ranging from fraudulent use as a homesite or commercial development, exclusive use for agriculture or logging, moonshing, blocking public campgrounds or highway development. Within the Tahoe National Forest the vast majority of the mineral patents on Forest lands were issued prior to 1910. Less than one-fifth of the roughly 30,000 acres of Tahoe mineral patents were issued after 1910. Of the patents granted from that year to 1937, subsequent Forest Service investigations determined forty-eight percent to be used primarily for purposes other than mining (IBID: 5-11).

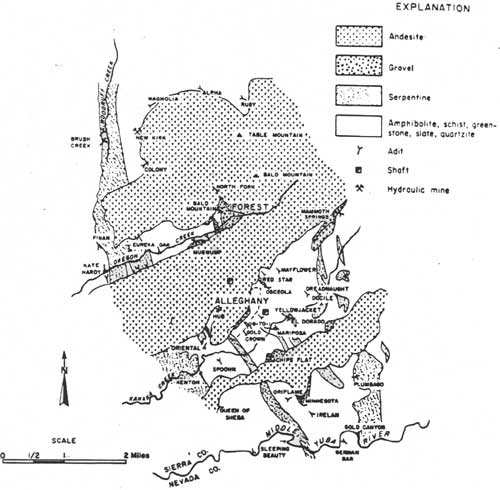

By the time Tahoe National Forest was established, the lode mining industry had reached a mature stage of development. The mineral areas containing gold bearing ores had already been discovered and more or less explored and exploited. Experienced mining engineers understood this, and instead of prospecting for new discoveries, mine operators and investors focused their talents on improving equipment, reducing operating costs, and improving their capacity to efficiently extract gold from the underground veins. With the rise in the price of gold during the 1930s, mining engineers and prospectors combed the countryside looking to patent claims. With a few exceptions, they directed their efforts to re-opening abandoned mines. Thus, even with the rise in the price of gold, lode production during the Depression was almost entirely from previously established mines.

The lode producing districts actively mining in the early 1900s were centered at Alleghany, Damascus, Downieville, English Mountain, Graniteville, Poker Flat, Sierra City, and Washington (Clark 1970: 19-131). Abandonment of mines in the nineties was forced by crude methods of extracting ore and failure to attract outside investors during that decade of depression. Local mining interests hoped that introducing modern equipment and electric power to the mines would make them once again paying propositions. By 1907, the Grass Valley Daily Morning Union expressed confidence in the resurgence of Sierra and Nevada county mines. People who had previously invested in Nevada's famed silver camps were beginning to look at California gold mines once again. The rejuvination of mining, the paper reported, "is the calm outgrowth of quiet and business-like investigation . . . Wealth is certainly here only awaiting the investment of capital and the application of scientific operation to uncover it" (10/2/07).

There did appear to be some reason for the Union's sanguine outlook in the fall of 1907. The Anchor mine near Graniteville opened for the first time in many years, and the new owners were erecting a ten mill stamp on the property. Eastern and San Francisco investors bought up the adjacent claims in several mining districts and consolidated the existing mines into single ownership. The Hayes brothers of San Jose, owners of the Sierra Buttes mines at Sierra City, organized the Sierra Buttes Water and Canal Company for the purpose of developing water power and generating electricity for their mining operations. Earlier that year the Alaska mine at Pike City was the first mine in Sierra County to obtain electrical power through hydroelectrical generation. The mines in that district were prospering. The Oriental mine, with a large body of paying ore, had plans to erect a new mill the following spring. At the Plumbago, Tightner, Red Star, and Sixteen-to-One the plants were running at full speed. In the entire Alleghany-Forest area, no miners were unemployed (Daily Morning Union 10/4/07, 10/5/07, 10/10/07, 10/11/07).

On a statewide basis peak production during the period from 1900-1929 came in 1915 when $22.4 million was produced by California gold mines (Clark 1970: 4). In Nevada County, the "War Years" from 1914-18 marked the peak of production. In each of these years the county's quartz mines produced over $3 million, a greater total than any year since 1880 (Report of the State Minerologist 1930: 96). By the early twenties adverse conditions were felt severely in these lode mining districts. Many quartz mines in Nevada County shut down completely. Unfavorable labor conditions, the continuing high cost of power and materials, and power shortages that curtailed milling and mining were the major reasons (Report of the State Minerologist 1921: 434-435).

Placer County mines produced little gold throughout the twenties. Only the largest mines weathered the storm. For the first time since 1900, the Nevada County quartz mines' output in 1928 dropped below the $2 million mark. Nearly two-thirds of the gold production came from mines either operated or acquired by the Empire Mines and Investment Company and the North Star Mines Company. Of the remainder, one-half came from the Idaho-Maryland Consolidated Mines, Inc. mines. In the Washington and Graniteville districts, investors made several efforts to rejuvinate former producing properties. Most of these efforts came from small, inadequately financed companies whose efforts in almost every case failed. In the Meadowlake District miners opened 24 claims between 1924 and 1929, but nothing more than perfunctory assessment work was accomplished. Of all the National Forest mining districts only Alleghany, where phenomenally rich ore pockets were being worked at depths of only a few hundred feet, seemed to prosper (Report of the State Minerologist 1930: 96-102; Clark and Fuller 1981: 57-58).

The price of gold on the world market began rising rapidly in 1932 stimulating activity in the California gold districts. Since the world price exceeded that paid by the U. S. mint by almost $10 per ounce, gold exports shot upward causing Roosevelt to institute an embargo in April of 1933. Later that year he relaxed the temporary embargo, allowing sales to foreign markets. Treasury officials foresaw a quickening of mining activity in the western states and predicted an increase in profits of $15 million per year (San Francisco Chronicle 8/30/33).

Within a month mining operators and engineers began appearing in northern Sierra gold towns. Stimulated by high gold prices, rehabilitation work on inoperative mines got underway and the Mountain Messenger (11/4/33) predicted a rebirth of activity in the mountain counties unlike anything seen since the gold rush.

. . . mining is the keystone to the whole situation, for with the influx of people as a natural consequence of the opening of our mines other things will follow. The abandoned hill ranches, with their orchards still intact, which supplied vegetables and produce to the miners would again be made to function; the lumber industry would be stimulated by the building activity that would follow the influx of a large number of people; the dairy and cattle industry would find an ample and ready market right at home, and the resort and campsite business would quickly develop to a degree where it would present a problem to care for visitors.