|

A History of Forest Conservation in the Pacific Northwest, 1891-1913

|

|

CHAPTER 1

BACKGROUND OF THE FOREST CONSERVATION MOVEMENT, 1860-91

I

Accordingly when later on in the nineties, the movement was in due course brought to success and signalized a victory, it should be remembered that it was a victory not of any one, but of many—a culminating victory—shared in by one and all alike, who, through the preceding years, had taken a part in the slow-moving process of molding popular thought along the lines of the movement. [1]

The history of forest conservation before 1890 can be divided into three periods. The first period, that from 1607-1776, was marked by rapid exploitation of the forest resources, accompanied by attempted crown regulation of forest use, and by flagrant breaking of the regulations. The second period, from 1776-1860, was that of almost unrestricted exploitation and waste of the forest resources by westward moving pioneers and by growing businesses. Forest resources were wasted, both because of inadequate land laws and a feeling that the supply was inexhaustible. The period 1860-90 was marked by a two-fold trend; first, an ever more rapid use and exploitation of the timber resources, caused by the rapid spread of population into the trans-Mississippi West, new developments making for larger business units, and technical developments in the lumber industry; and, second, the growing awareness of groups throughout the country that the process of wasting resources must come to an end, and the efforts of these groups to bring about a new and sane management of the nation's timber resources. The first two periods are, for our purposes, not necessary to the story; but the third must be touched on, as a necessary prologue to the main theme.

II

It should be remarked in the beginning that no single group or individual can be given full credit for the growth and success of the movement for forest conservation. This was rather the result of action and thought by several groups, working either independently or together, for a variety of things concerned with forest and forest influences. The movement involved a complex interaction of federal and state action; scientific and transcendental thinking; and rural and urban groups. Scholars writing on the subject have resembled the blind men viewing the elephant; each, in dealing with his particular segment of the beast, has imagined it to be the whole. [2]

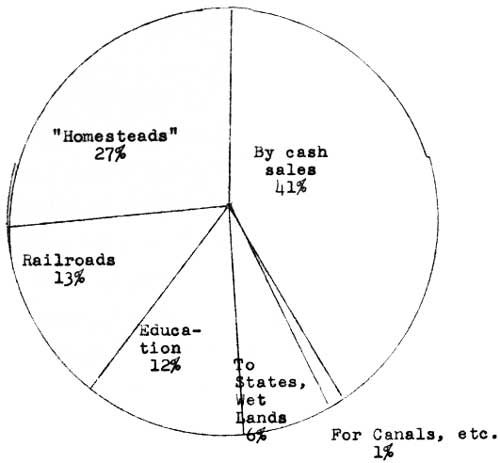

The process of disposal of the public domain increased after the Civil War at an increased rate. The Homestead Act and its numerous subsidiary acts were used widely by both bona fide settlers and by those who perverted the laws for their own purposes. Much land was donated through the public domain in the form of educational grants, at first in the form of two sections to each township, and later in separate liberal grants for education. In aid of transportation, 94 million acres were granted; for roads and canals, 10 million acres; and 65 million acres were given as swamp lands. [3]

TABLE 1

THE PUBLIC DOMAIN, HOW DISPOSED OF PERCENTAGES

The story of the public domain is a familiar one, and the phases of our primary concern are in regard to timber lands. There existed no good law in regard to timber lands, designed to get a land unit large enough for continuous logging operation into the hands of the operators. Land laws had been designed with the small owner in mind, and the homestead laws were primarily for agriculturalists. An exception was grants to railroads and to wagon road companies, many of them in timbered country.

Two laws passed to fill this need had little success. The Timber and Stone Act and the Timber Cutting Act were both passed in 1878. The Timber Cutting Act authorized citizens of the states of the Rocky Mountain West to cut timber without charge on the public domain for mining or domestic use; while the Timber and Stone Act provided that timber lands in the states of California, Oregon, Washington and Nevada might be sold in areas not to exceed 160 acres per person. In such sale, the entryman would make affidavit that the timber or stone was for personal use and that the entry was not made for speculation or any other commercial purpose. [4]

The new land laws did little to better the situation, and like the old laws, were the subject of abuse. There was wholesale abuse of the Timber Cutting Act by corporations and lumbermen. Land office agents concerned with timber trespass were few and inactive; and often the Registers and Receivers of the local land offices were in sympathy with the depredators. Trespass cases were often settled out of court after 1882, with minor amounts recovered in proportion to the losses. The Timber and Stone Act was used by large corporations rather than by bona fide settlers; often large corporations entered the land and required their laborers to make entries and convey over to the corporation their entries at $2.50 per acre. The value of a single large tree would pay for the entry, and many more entries besides.

Other laws were also abused. Much timber land was homesteaded, or commuted, in order to get the timber. Much of the best timber land in California was taken up as swamp land. The states, with a few exceptions, sold their school lands readily to operators; and many of the wagon road and railroad grants came into the hands of lumbermen. Under the Indemnity Act of 1874 railroads, when their grants conflicted with bona fide settlers' claims, were permitted to select in lieu other lands; and often valuable tracts of timber lands were substituted for lands of less value. Furthermore, railroads were permitted to cut timber for ties on their right of way; but often trespassed far beyond the limits of their right of way to cut timber for commercial use. Despite protests against this exploitation—coming from the west as well as the east—the Department of the Interior was either reluctant or impotent during much of this time to curb the exploitation. [5]

Though exploitation continued, there came also to be concern over the devastation of the public domain. The precise root of the feeling is difficult to arrive at; that is, the main current of thought can be arrived at, but the precise mixture of various strands of thought are hard to unravel. To some extent the conservation movement was aesthetic in nature, expressing a desire to preserve areas of unique scenic beauty from the herds of the flocksmen or the saws of the lumbermen. Of such origin was the efforts of interested groups to create Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Crater Lake National Parks, and the later desire to preserve park areas in the region of Grand Canyon and Mt. Rainier—the desire to have parks for the people as a whole, rather than private ones for use of wealthy landowners. Although suggested by George Catlin, and probably others, Henry David Thoreau gave the belief its most popular expression in The Maine Woods:

The kings of England formerly had their forests "to hold the king's game" for sport or food, sometimes destroying villages to create or extend them; and I think they were impelled by a true instinct. Why should not we, who have renounced the king's authority, have our national preserves, in which the bear and panther, and some even of the hunter race, may still exist, and not be "civilized off the face of the earth," our forests, not to hold the king's game merely, but to hold and preserve the king himself also, the lord of creation—not for idle sport or food, but for inspiration and our own true recreation? or shall we, like the villains, grub them all up, poaching on our own domains? [6]

Thoreau undoubtedly read Catlin's statement, but this does not necessarily imply he was indebted to Catlin for the thought; the idea was in the air at the time. See Hiram Martin Chittenden, History of Yellowstone National Park (Stanford, 1933), pp. 69-70.

Thomas G. Manning, in a paper read at the American Historical Association Meeting of 1952, stressed the national park movement as an expression of the nationalistic spirit of the country after the Civil War.

This feeling had long been latent in Americans, but was hastened by the rapid urbanization and development of industry in the post civil war period. The growth of cities, and the changes in the landscape occasioned by city growth and large scale exploitation of resources, led groups to seek means to preserve the wilderness values. One aspect of this search was the city park movement, which went hand in hand with the national park movement. Another was the movement for associations of sporting clubs, walking clubs, and fishing clubs, for organized activity in the lines of interest of its group. A third was the desire to protect the environs of the city itself, as a hinterland in which the city dwellers could seek recreation. [7]

The recreational spirit was not without its utilitarian aspect as well. The fact that scenic beauty helps to attract travelers and tourists was early realized by local boosters in the West. Such cities as Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Las Vegas, New Mexico, grew up largely because of their attraction to tourists, where they could enjoy the mountain scenery. Civic associations in Colorado, Oregon, and California, as well as in the east, boosted the tourist trade by bragging up the beauties of the country; and thus became interested in preserving the natural beauties that surrounded them. [8]

A record factor was the growing socialization of the country. Two aspects of this are of application here. On the part of agrarian groups, this was indicated in a growing desire to have revision of land laws, in order to prevent fraud and aid the settlers in the lands of the west. Probably of more importance for the cause of conservation was the growth of public ownership in cities. In most cities such utilities as water supply, public markets, city parks, and so on were originally operated by private individuals. But the privately owned utilities gave unsatisfactory service, and caused interruptions of service. In the face of these conditions, decisions were made for the city to build, own and operate their own services. These decisions were not made on the basis of any underlying social or economic philosophy, but solely a practical decision, recognizing the need for service. [9]

In the public land states most cities got their water supplies from the wooded districts, on the public lands. These lands might well be prey to the flocks of the herdsman, the saw of the lumbermen, or the fires of campers. Just as efforts to get a municipal water supply enhanced the power of the municipal government, so it enhanced the power of the federal government no qualms were felt as to federal encroachment if the end to be gained was justified.

Fundamentally, however, the movement was scientific in nature. The era was one dominated by interest in natural science, though often mingled, like the thinking of Thoreau, with a species of transcendentalism. There came a new appreciation of the value of the landscape, when love of soil replaced land hunger. The interest was not primarily aesthetic or romantic, though it had elements of these in them; it was scientific and realistic, the thinking of geographers, landscape planners and scientists.

The movement was that of a variety of people and groups. George Perkins Marsh was probably the first to sense the destruction that was going on, weigh the losses and point out an intelligent plan of action. Taking the rise and fall of kingdoms as his theme—a subject ever of interest to the American public—he argued the cause was a waste of natural resources. Other popular writers followed the same line of argument, such as Nathaniel Shaler, John Muir, and Frederick Law Olmsted. By 1890 the idea that there was an intricate and complex relationship between soils, water and forests was a matter of common knowledge among most of the American people. [10]

Of more importance in giving basis for the popular writers were the scientific reports made during this period. The period after the Civil War marked the establishment by government and states of bureaus for scientific study of land management—the Geological Survey, the Agricultural Experiment stations and the land grant colleges of the West. In addition there rose a large number of professional organizations on state and national level concerned with natural resources. Growing urbanization gave rise to recreational and scientific organizations concerned with preservation of wild life and of wilderness values, such as the Boone and Crockett Club, the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and the American Forestry Association. The organizations not only acted as propaganda bureaus for dissemination of their points of view, but also gathered in the field a considerable body of facts to support their generalizatons, and give a round basis for reform.

III

With these diverse bases, the movement gained headway during the period from 1860-1891. To trace a clear course is difficult, since the work involved work on three levels—the state, the federal, and the associational or guild. It may be well to trace these separately, bearing in mind their association and mutual interaction.

The federal government was committed to the disposal of the federal domain; therefore, it was logical that the first governmental group to take action should be the states. In these the western states led the way. In Colorado, Colonel Edgar Ensign, an Iowa lawyer who migrated to the state, and attended the state constitutional convention of 1876, succeeded in getting a provision written into the constitution for management of its forest lands. The constitution directed the legislature to provide for the protection and management of the state forest lands. The state did nothing to implement this proposal at the time, though it did petition Congress to vest possession of the federal forest lands in the state in state hands, for control of waters valuable in irrigation. In 1885 a state forestry commission was appointed, with Ensign in charge. Ensign did some work on the county level in controlling burning and educating the people as to the dangers of fire; but the commission lapsed for lack of funds.

In California in 1885 a forest commission was established, headed by Abbot Kinney, a fruit grower, business man and town promoter. In 1887 forest experiment stations were established in various parts of the state, and John Gill Lemmon, a botanist who had had training under Asa Grey, was appointed California State Forester. Like that of Colorado, however, the state ventures suffered from lack of finances. Other states, such as Ohio, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, followed suit in establishing forest commissions. [11]

Other action was taken as well. The Hatch Act, and the Morril Act, establishing agricultural colleges and experiment stations, exercised an educational influence in states where these were established. Working closely with the governmental forest agencies, they served a definite purpose in educating the people and breaking them from old, and destructive methods of land use. The universities made experiments in tree planting, and laid some little basis for the practice of forestry. In general, forestry men from universities had charge of forestry exhibits at the World Fairs. All these found popular interest.

Action began, too, on the level of voluntary associations concerned with forestry and forest preservation. The American Academy for the Advancement of Science, in 1873, appointed a committee "to memorialize Congress and the several state legislatures upon the importance of promoting the cultivation of timber and the preservation of forests and to recommend proper legislation for securing these objects." [12] They acted as a pressure group, working on both federal and state governments until 1880, but with little success. More important was the founding of the American Forestry Association in 1875, which became the chief professional organization of those interested in forestry. Its membership was nationwide, though its center of gravity remained in Washington, D. C., and in the midwest. Many local associations sprang up, the most important probably being the Colorado Forestry Association.

The associations worked on several levels. Their chief function was perhaps their role in educating the people, and acting as a clearing house for information. As with all learned societies, in their conclaves papers were read and ideas exchanged, so some nucleus of ideas as to forest conservation was gathered. They also served as a potent pressure group, on both state, federal, and local level. [13]

Most of the timbered states passed state fire laws during this time—though there is much evidence that they were largely unenforced. [14] Memorials and bills by the dozen poured into Congress from state legislatures, civic and professional groups, and friendly congressmen, requesting reform of the land laws governing timber or requesting creation of national forests. Here again, no single section of the country was predominent; such diverse states as Vermont, Ohio, Minnesota, South Dakota, New Mexico, Colorado, and California were represented. [15] Edgar Ensign, in his survey of mountain forest conditions in the West, found that there was wide-spread discontent in all the states of the Rocky Mountain west with administration of the timber land laws. [16] Yet the bills for the most part died in committee.

Nevertheless, as time went on some work was accomplished. Some of the administrative officers in charge of the public domain, notably Carl Schurz, James Williamson and Lucius LaMar, took steps to curb the worst abuses of the land laws, and instigated suits against some of the worst offenders. [17] More important than this was their printed reports, which did much to alarm the public over exploitation of the country. Within Congress itself, some congressmen became alarmed over the situation; such men as Pettigrew of North Dakota, Lacy of Arkansas, and Plant of Kansas sponsored bills calling for establishment of a rational timber policy. By 1876, through the work of the Smithsonian Institute, the New York State Agricultural Society and the Department of Agriculture, enough congressmen were convinced of its desirability to establish a commissioner of forestry for the nation. Appropriations were meagre, and authority small; but successive commissioners utilized the office for collecting statistical information on forests. In 1886, with the appointment of Bernhard Edouard Fernow to head of the division, new impetus was given to governmental work.

Fernow became the leader of the movement both on the governmental and the associational level. A Prussian by birth, educated as a forester, he came to the United States to visit an American girl to whom he had become engaged. The visit lasted thirty years, and he became a prime mover in the forestry movement, both in the United States and in Canada. He became associated as a mining engineer with Abram Hewitt and Rossiter Raymond; worked on their forested property in Pennsylvania; and joined the forestry associations which were springing up in the area. He rose to head the American Forestry Association, and in 1886 became head of the Division of Forestry in the Department of Agriculture. The Division had only an advisory and educative function, and no power of administration over forests; but Fernow made it something more than a supernumerary department. It became a clearing house for information of forest and forest statistics, and offered a means of correlating the activities of associations and federal activity.

As an administrator, Fernow had some great strengths and also some weaknesses. With teutonic thoroughness, he traveled over the United States—at his own expense—to view at first hand the forests of the nation. Quietly and unobtrusively, he got the numerous associations on national and state levels to working for a forest policy together; and on the national level, he got the support of a bloc of congressmen who would introduce bills looking toward such a policy. As an administrator, however, he aroused some antagonism. Though foreign born, he was acutely aware of the necessity of the democratic process, and desired to move no faster than the people would stand for and only in accustomed channels. To men like Pinchot, he seemed overly cautious. He had little taste for engaging in the inter-bureau rivalry of Washington, and against the more dynamic new administrators, such as Gannett of the Geological Survey, he appeared at a disadvantage. [18]

Action on the federal level was slow in coming. Both state and federal policies on land looked to disposal, as a means of economic development of the country. The emphasis of a century had been, not conserving the wealth of the country, but encouraging each generation to use and develop the riches available. There was, in the country, little exact knowledge of forest management; such principles as were known were, for the most part gained from European observation, and were not necessarily applicable to this country. So much timber was available that there seemed no need of restoration; and those who warned of a timber famine were regarded for the most part as prophets of doom. The states were jealous of their sovereign rights; the federal government was one of limited powers; private individuals insisted on the same rights that had been that of their ancestors; and a constructive forest program commensurate with these conflicting needs and opinions was hard to arrive at. Added to this was the general moral letdown and flabbiness of the government in the post-civil war era. Yet there is every evidence that the states and the people in general were far ahead of Congress in sensing the need for a forest policy. Congress, and especially the Senate, where the members were not popularly elected, were dominated by economic man, more interested in private gain than in public good. Many members had a personal and immediate interest in exploitation of the public domain, and were reluctant to brook any interference with this freedom. [19]

Congress yielded slowly to the pressure from those who favored forest legislation. Bill after bill was introduced in almost every congress years after 1876; some the product of members of Congress, some the result of petitions from state legislatures or municipalities or individuals, in Colorado, New Mexico, and California, some written by Fernow or other members of forestry associations and presented through friendly congressmen. Some of the bills looked to a comprehensive forest policy; others petitioned for withdrawal of specific areas in the mountains of Colorado, New Mexico, Montana, and California as forest reserves. Only one of the bills got out of committee. As one historian has written:

At the time the Western States were urging the reservation of public lands and when the Forestry Congress proposed their transfer to the states, the Federal Government made no move to withhold them from disposal and only occasional gestures to protect them from fires and depreciation. [20]

Almost by accident, the work of all these groups finally reached fruition in 1891. In that year a group of scientists, including Edgar Ensign, Edward Bowers, Fernow, and others, conferred with Secretary of the Interior Noble, on the matter of reserving and protecting the public forest lands. Against some formidable opposition on the part of John Wesley Powell, they managed to persuade Noble of the desirability of the legislation. On midnight of March 3, 1891, the Secretary managed to get a rider on a bill, then in conference committee, giving the President the power to set aside forest reservations. No record debate was made, and the bill became law on March 3, 1891. [21]

IV

In the early movement for forest conservation, from 1860 to 1890, the Pacific Northwest—Oregon and Washington—played but little part. Nevertheless, the changes that took place, both in the area itself and in its sub-regions, during this time had a significant effect on the fortunes of the movement there.

First, there were important changes in transportation and communication which affected the district. In the period from 1840 to 1880 the area had been isolated from the main area of the United States. There had developed over this time because of the isolation and because of certain common ideals and attitudes the immigrants had brought with them, a set of cultural and social attitudes that Lancaster Pollard describes as "area-kinship." The settled areas were small, and the region was dominated by Portland. This city dominated the social and cultural life in the Willamette Valley and to The Dalles on the east, and its hinterland extended over the area both east and west of the mountains.

During the 80's the railroads reached the west coast in this region, with terminals at Portland, Seattle, and Tacoma. The railroads ended the region's isolation, bringing in people of a different regional and cultural background than those already there. Oregon experienced a population increase of 80 per cent in the decade from 1880 to 1890; Washington, 380 per cent.

In Oregon the new population was rapidly assimilated and did not affect the cultural pattern a great deal. The bulk of the newcomers settled in the Willamette Valley among the old Oregonians and rapidly became a part of the community. Such was not the case in Washington. Not only was the increase greater, but within the Puget Sound area a great number were drifters and people on the move, with a much more confused political and social background than in the Willamette Valley. The Willamette Valley had a great deal of stability; the Puget Sound area a boom psychology. [22]

There were significant shifts in industry also during this time. Most important in regard to conservation were the changes in the lumber and the grazing industry. Passage of the first bill to establish a conservation policy in the United States, in 1891, coincided with the shift of the lumber industry from the lake states to the Puget Sound area. Several things brought about the shift; probably the two most important factors were cutting over of the pineries in the lake states and completion of transcontinental railroads. The chief cutting was in the State of Washington, in the Puget Sound area, where railroads, water transportation, and pure stands of old growth Douglas fir attracted loggers from the lake states. By 1889 lumber production in Washington equaled that of Minnesota, and by 1909 led that of the United States. [23]

The sheep industry also became important during this time. The sheep industry in Oregon had had an early start in the Willamette Valley. The sheep were of fine quality, and as early as the decade 1860-70 sheep were exported from Oregon to other areas, where they commanded a premium price. As farms grew in the valley, summer range was resorted to in the mountains, and sheep husbandry shifted from the farm variety to the range system. By the 1870's sheep grazing was well established in the Blue Mountains. About the same time the area in the foothills of the Cascades, in Wasco County near The Dalles, was utilized, and as settlement progressed further south on the east side, first the foothills, then the middle elevations, and finally the mountain meadows were utilized. Sheep grazing started on the east side of the Cascades in Washington about the same time, beginning in the Yakima Valley, and extending up along the east side of the Cascades to the Colville Indian Reservation. [24]

The period from 1870 to 1890 was the period of the great sheep trails, when the range lands of Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana were stocked with sheep from Oregon and Washington and California. Sheep were driven overland from the coast states to the new range land in the Rocky Mountain west in great numbers annually. Exact statistics are hard to arrive at; the figure of 3 to 4 million exported from Oregon alone during this period is probably a conservative one. [25]

Both states were plagued by the usual evasions and perversions of the land laws that were typical of most of the public land states. This story is a familiar one, and need not be elaborated on. Bearing in mind that the general tendency was the same, some specific circumstances peculiar to each state should be recounted, in regard to the school land.

Oregon was hampered by weak laws protecting her school lands—a circumstance which gave rise to one of the most publicized land scandals in the west. By a law passed in 1887, it became mandatory for the state to sell her unsurveyed school lands at $l.25 per acre. Other state land, such as swamp land, had also come into the hands of speculators at less than its real value through land rings in close touch with the state legislature, and by 1890 there was some sentiment opposing this tendency. [26]

In Washington the situation was somewhat different. This state profited by the work of William Henry Harrison Beadle, the Surveyor-General of Dakota Territory. Beadle had become alarmed at the waste of the school land in the older states, and had insisted that Dakota, and the other states included in the Omnibus Bill of 1889 as well, have in their state constitutions clauses protecting their state land. By the constitution of these states, the school land could not be sold for less than its appraised value, and for not less than $10 per acre. [27]

Although the Pacific Northwest was not among the prime movers for a program of forest conservation, it was not immune from the currents of intellectual life. Here the first influence to be felt came from the Willamette Valley urban centers. In this, the oldest settled part of the Northwest, the needs of a forest policy were evident. People here as elsewhere read the scientific reports dealing with the forests, and speculated pro and con the effects of grazing on the forests reported by Muir. With growing cities came the desire to protect the city water supplies against the axe of the woodsmen or the herds of the flockowner. And in Oregon, as elsewhere in the country, some elements in the population became tired of fraud in the administration of land laws.

The first movements in the northwest came from recreational groups. Blessed with an unequaled natural heritage, Oregonians took full advantage of their chief assets, the mountains and the sea. Summer excursions were made by road or steamboat to resort towns along the coast, where swank resorts of almost Newportian elegance catered to the Portlander society, and where others might rent summer cabins or camp in the dunes. [28] The mountains, too, had their share of devotees. In buckboards, on horseback or bicycles, or on foot, people headed for the hills in summer—fishing for trout or salmon in the Santiam or the Clackamas, the scene of Rudyard Kiplng's most famous fishing exploit; [29] camping in the wilds of the Cascades, or gathering huckleberries in old burns or mountain meadows. Summer hotels sprang up, where people might hike, fish, or rock on the front porch and enjoy the natural beauty around them. [30] For those to whom the heights called, Cloud Cap Inn was built in 1889, anchored to the rock on the very slopes of Mount Hood.

Of the mountain lovers, none was more enthusiastic than William Gladstone Steel, who had come to Portland from the treeless plains of Kansas. Combining the love of nature of a Thoreau with the booster spirit of a Babbit, he spent his spare time in boosting the mountain scenery of the Pacific Northwest. He took the lead in forming the Oregon Alpine Club, organized in 1887. This club and its successor, the Mazamas, played much the same role in the forest conservation movement and park movement in Oregon that the Sierra Club did in California. The Alpine Club's membership had its headquarters in Portland, and included among its members many important Portland business men, bankers, and city officials, such as Henry W. Corbett, Henry L. Pittock, William Ladd, and George Mitchell. The membership was not limited to Portland, however; Hood River, Salem, The Dalles, and other cities in the hinterland of Portland were represented among its members. Of especial importance were Malcolm Moody of The Dalles, the second man to ascend Mt. Adams and later to be Oregon's representative in Congress, and the Langille family of Hood River and Cloud Cap Inn, who were to play an important part in the movement for forest conservation.

Steel's chief claim to fame has come as a result of his activities in relation to Crater Lake. He visited the lake in 1885. Impressed by the natural beauty of the area, and encouraged by the success of Montana and California groups in reserving areas of unique scenic beauty from entry, Steel began a campaign for reservation of the lake and its surrounding country. Singlehanded, and at his own expense, he circulated a petition asking for the area to be made a public park. The petition was signed by a large share of Oregon's office-holders and wealthy men, and on January 30, 1886, the area was withdrawn from entry. No provision was yet made to make it a park, however; that campaign took another sixteen years. [31]

Two years after the reservation of the Crater Lake area, another attempt was made to withdraw an area of scenic beauty, this time by John B. Waldo. Waldo was the son of an Oregon pioneer, and a one-time state judge. He was a mountain lover, who spent his summers exploring the mountains and lakes in the Cascades. Each year he would leave the valley in early summer, and head for the wildest and remotest parts of the Cascades, either alone or with such friends as John Minto, the State Horticulturist, or William Gilbert, the Federal District Court Justice. A man of wide learning, and possessor of a large library, he had become concerned about the permanent losses to the country by the policy of land disposal.

In 1889 Waldo was elected to the Legislative Assembly of Oregon. Inspired by the writings of Thoreau, and probably by the examples of Colorado and of California, he introduced House Joint Memorial No. 8, "praying Congress to set aside and forever reserve, for the uses therein specified, all that portion of the Cascade Range throughout the State, extending twelve miles on each side, substantially, of the summit of the range."

The projected reserve had a variety of purposes. One clause in the memorial stated:

That the altitude of said strip of land, its wildness, game, fish, water and other fowl, its scenery, the beauty of its flora, the purity of its atmosphere, and healthfulness, and other attractions, render it most desirable that it be set aside and kept free and open forever as a public reserve, park, and resort for the people of Oregon and of the United States.

However, the memorial also cites the value of the forests, waterflow, the indirect effects of the forests on climate, and use of the area as a game preserve.

The projected management of the reserve was ingenious. It stands out as an early and unique attempt at federal-state partnership in managing resources, and was markedly in contrast to the prevalent manner of withdrawing areas without making provision for their administration. In addition to the reason already cited, the memorial cited the value of the forests in protecting the sources of streams, the indirect influences of the forests on climate, and use of the area as a game preserve. The management was to be in the hands of a board, headed by the governor of the state, and consisting of six men named by the governor, and six by the President of the United States. The commissioners would also serve as state game commissioners. They would guard the game, and could give leases of not over fifteen years duration, for resorts in the reserve, provided that no resort be over 40 acres in area or be closer than five miles to another. The commission would report to the legislature each session, making recommendations as to improvement of the area and recommend legislation to protect the fish, game and natural beauty. Grazing would be prohibited in the area except by stock in transit or by campers' saddle and pack stock. No market shooting or fishing would be permitted within the reserve. Mines could be worked, but claims would be declared void if assessment work ceased for a period of two years; and railroads crossing the area could take the timber and stone needed for construction of the line, and no more. The boundary was to be established by survey.

On introduction the memorial was referred to a special committee, consisting of one member from each of the counties on either side or the range bordering the proposed reservation. Amendments were made in committee, largely to please the grazing interests. The Jackson County delegation demanded that grazing land in that county in the extreme southern part of the state be withdrawn from the projected reserve, and the adjacent portions of Klamath County were withdrawn also. Also the prohibition of grazing was postponed for a period of ten years, allowing sheepmen to find new ranges. As amended, the memorial was recommended for passage, and passed by a unanimous vote.

In the Senate, however, the memorial met a different fate. The sheep interests had gathered their forces, and the measure, after being referred to the Committee on Public lands, was tabled. [32] It remained for William Gladstone Steel to revive the idea after the passing of the act of 1891.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

history/chap1.htm Last Updated: 15-Apr-2009 |