|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 1

The Wild Woods

The news came out on Sunday. The Arkansas Gazette, then in its 89th year, reviewed the current trivia and trauma in its skinny news columns.

Advertisements on the lower half of the front page offered banking reports and sundry goods, including, for men only, fine negligee shirts with detachable cuffs, white or colored. Sale price, one dollar. Inside the newspaper, the Gus Blass Dry Goods Company announced the arrival of "new flashy Red Knickerbocker" coats for girls eight to sixteen years of age. A nine-room house was available on easy terms for $6,250, including barn, fences, and servants' quarters.

Politically that Sunday, John H. Hinemon had just been endorsed as the prohibition candidate for governor, while the Anti-Saloon League of Arkansas had not come out with a candidate. The United States stood ready to mediate the Sino-Japanese crisis as Japan prepared for war. Theodore Roosevelt sat in the Oval Office of the White House.

It is he who is important to this story and to the Arkansans reading their newspapers on that mild Sunday, March 8, 1908.

Under a Washington dateline came the announcement of a new National Forest in the state of Arkansas. [1] Roosevelt, a president committed to conservation and to protecting the resources of America's timberlands, had on March 6, 1908 set aside by proclamation 917,944 acres of land that had been a part of the public domain lands in Arkansas. This forest, the Ozark National Forest, covered the rugged, mountainous lands north of the Arkansas River, and was made up of hardwood timber estimated to have a standing value of $1.5 million at the time of proclamation. This forest was the first protected stand of hardwoods in the country. With proper management the value of this timber might increase to $5 million. [2] It would take some of the citizens who read the announcement on March 8, 1908, many years to realize the ultimate value this National Forest would come to have—this forest which then spread over five counties in the Arkansas Ozarks.

A second proclamation was made on February 25, 1909, adding an other 608,537 acres to this original proclamation. [3]

|

| Old Indian hieroglyphics, supposedly near a Spanish gold deposit. According to legend, Indians are supposed to have ambushed a group of Spaniards and hid the gold in the side of the mountain near this spot. Photo No. 371130, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

The Ozarks.

Hand tools and other artifacts provide evidence that bluff dwellers once made their home in the Ozarks. No written accounts describe these people, but museum displays at the University of Arkansas in Fayetteville tell a history of sorts.

Later tribes inhabiting Arkansas were the Caddo people in the south and in parts of the Ouachita Mountains, the Osage in the Ozarks and also in the Ouachitas, the Quapaws along the eastern plains, and the Cherokee who received reservation land between the Arkansas and White Rivers in exchange for land given up in Tennessee.

The first white explorers came to the region in 1541 when Hernando DeSoto and his force of 400 men arrived near Helena, establishing Spanish influence in this part of the New World. [4] More than 100 years later, in May 1682, Rene Robert Cavelier Sieur de la Salle claimed all lands west of the Mississippi River for France. La Salle granted to one of his lieutenants, Henri de Tonti, land near the mouth of the Arkansas River, and here de Tonti established the settlement of Arkansas Post in 1686. During the next 75 years, further exploration of the Arkansas River continued, but there was not much in the way of land development or settlement. One French explorer of this period was Bernard de la Harpe, who is often credited for naming the site of the future state capital—Little Rock, la petite roche, referring to a small outcropping of green schist and sandstone. [5]

Until 1803, France and Spain alternately advanced claims on the lands of the Mississippi River Valley. In that year, however, the United States acquired all this land through the Louisiana Purchase at a cost of $15 million, or slightly over two and one-half cents an acre. [6]

Arkansas was first a part of the Louisiana Territory and after Louisiana achieved statehood in 1812, Arkansas became part of the Missouri Territory. By 1819, Arkansas itself achieved territorial status.

The state's population prior to territorial days had remained small. One reason the Ozark's population remained so small was the danger presented by the Osage Indians, in spite of various treaties. Following the New Madrid earthquakes in 1811 and 1812, however, people began moving into the northern portion of Arkansas. In addition, population figures rose when the soldiers who had received grants of land following the War of 1812 moved into the state. By 1819 land speculators were busy buying rights for $3 to $10 per acre and the population had reached 14,000. [7]

Early Settlement.

Jacob Wolf, the appointed Indian Agent, moved inside Indian Territory in 1810. He built a log house near Norfork, Arkansas, and established what is considered the first white settlement in Indian Territory. The White River at that time served as the dividing line: The Territory of Missouri lay east of the river, and Indian lands to the west.

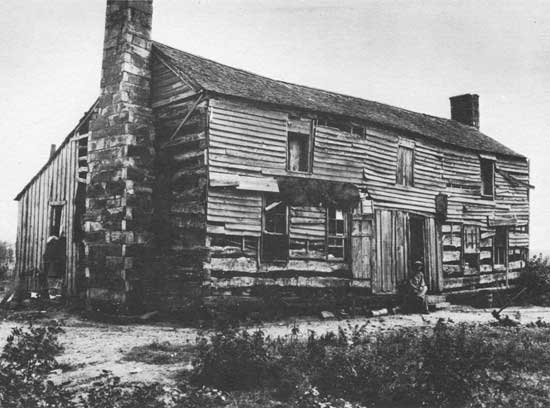

|

| The Wolf Museum and memorial at Norfork, Arkansas. Photo No. 371081, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

In July 1820, a group of missionaries under the leadership of the Reverend Cephas Washburn, reached the Illinois Bayou, two miles west of the city of Russellville. Washburn and his group built their mission in a wilderness, naming it "Dwight Mission" to honor Timothy Dwight, then president of Yale College. The first tree was felled August 25, 1820, and a mission report to the Secretary of War described the first clearings and structures. A schoolhouse, planned to accommodate up to 100 children, began its first term January 1, 1822. [8]

|

| The old home of Cephas Washburn, founder of Dwight Mission and the state's first school. Photo No. 250506, by J. M. Wait, 1930. |

|

| Placing a marker on site of Arkansas's first school, Dwight Mission. The school opened in January, 1822. Photo No. 2505506, by J. M. Wait, 1930. |

Following the removal of the Cherokee in 1828, the country opened for white settlement. [9] Norristown was established east of Dwight. Situated on the north bank of the Arkansas River, just opposite Dardanelle Rock, Norristown, at one time reached a population of 400. One story has it that the town just missed being named the territorial capital by two votes when the capital was moved from Arkansas Post. [10] Little Rock became the capital in 1820. As for Norristown, crops now grow on what remains of the townsite, leaving few traces of the original streets or buildings.

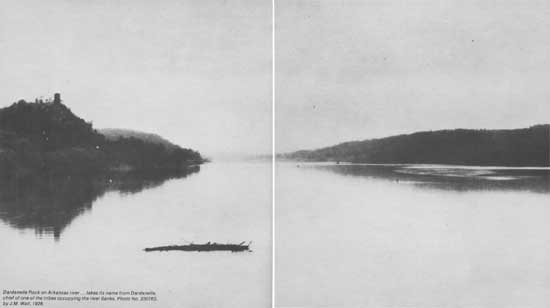

|

| Dardanelle Rock on Arkansas river...takes its name from Dardanelle, chief of one of the tribes occupying the river banks. Photo No. 230763, by J. M. Wait, 1928. |

By 1828, Arkansas essentially attained its present-day size and shape. The land along the western border became known as the Indian Territory and a land beyond order, a refuge for outlaws. By the time Arkansas became the 25th state of the Union in 1836, the population was well over 30,000, and by 1840 had more than trebled, reaching 97,574. Small isolated settlements developed first along the principal streams. In the Ozarks these were the productive lands of the Illinois Bayou, Richland Creek, Big Piney Creek, and along the Mulberry and White Rivers. By 1844, however, settlement extended to the higher plateau lands where the soil was thin and poor.

Transportation.

Except for De Soto's marches, early explorers came by waterway, using dugouts and keel boats. [11] Steamboats later brought immigrants. Trails connected even the earliest of settlements, and wagons and ox-carts marked the beginning of vehicular travel in the Arkansas Territory. The earlier settlers followed Indian trails and creekbeds. A journey to the nearest trading post for supplies was a task of no small proportion. Little could be grown on the remote Ozark farms that would pay the cost of hauling to market. Consequently, agricultural development was slow and industrial development was non-existent.

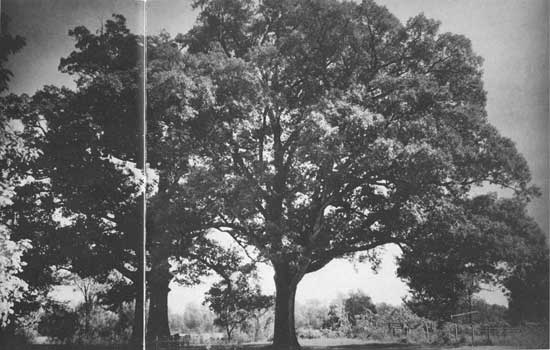

|

| View of famous Council Oaks under which Acting Governor Robert Crittendon made treaty with Chief Black Fox in April 1820 deeding the Cherokee land south of the Arkansas River to the State of Arkansas. Photo No. 426774, by Clint Davis, 1943. |

|

| Public road in a creekbed on the mail road to Mt. Levi. Photo No. 18924A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

| Sylamore Road—most expensive road in County prior to 1913. Photo No. 19496A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

The Forest.

Life in the Ozarks had its disadvantages, but the early settlers found the forest rich with the raw materials for living. Most of Arkansas' 34 million acres were heavily forested when the first explorers came. [12] Thomas Nuttall kept a botanical journal of his travels through Arkansas in 1819, describing "one vast trackless wilderness of trees," where "all is rude nature as it sprang into existence, still preserving its primeval type, its unreclaimed exuberance." [13] Frederick Gerstaecker, another Arkansas traveler who came to the state 20 years after Nuttall, noted jungle-like vegetation. Such travelers wrote about howling wolves and the roaring panther, about bear and the deer. Nuttall described the favorite food of the flocks of "screaming parrots" as the seed of the cocklebur, Xanthium strumarium. When Nuttall reached the mouth of the St. Francis River, he walked into the woods for two or three miles and listed the species found—black ash, elm, hickory, walnut, maple, hackberry, honey locust, coffeebean on the higher grounds; and in the riverlands, the platanu or buttonwood, the enormous cottonwood called yellow poplar, and holly. [14]

|

| Newton County Arkansas. Koen Experimental Forest. Photo No. 497027 by R. W. Neelands, 1960. |

The richness of the forests provided the settler with the necessities of life. He hewed logs for his home and farm buildings. Trees furnished the material for furniture, wagons, and tools. Game provided meat for the table. Gerstaecker described one rough-cut home. It consisted of "two ordinary houses under one roof, with a passage between them open to the north and south, a nice cool place to eat or sleep in during summer. Like all block houses of this sort, it was roofed with rough four-feet planks; there were no windows, but in each house a good fireplace of clay." [15]

Logging in the Ozarks had begun by 1879 although fewer than ten steam sawmills then operated within the Cherokee Reservation. Following construction of the railroads this number increased, and by 1890, the lumber industry was established.

Few persons in the 19th century thought the timber wealth of the United States, or the Ozarks, could be exhausted. But by the end of that century, cutting had progressed at a rapid rate with little thought given to future supply. In Arkansas, the timberlands at first were "high-graded." High-grading is a logging practice which takes only the biggest, the best, and the most accessible hardwood timber. Later, some areas were practically stripped; entire watersheds almost denuded. By the end of the 19th century, choice timber species, such as cherry and walnut, had become hard to find. Virgin white oak and pine were found only in the more inaccessible locations.

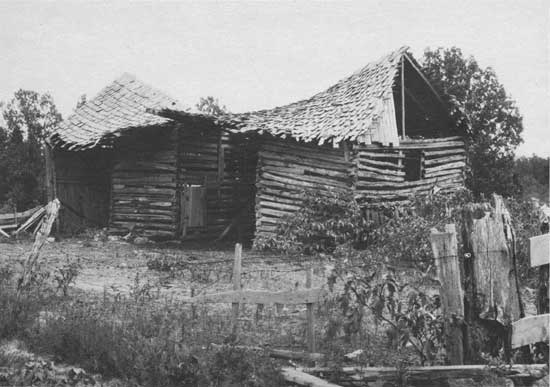

|

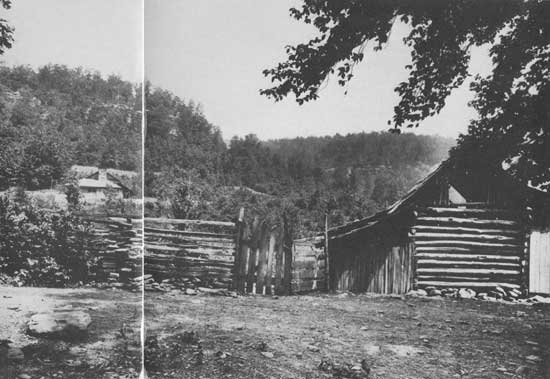

| Top: No, this home was not destroyed by a tornado. It was wrecked by poverty induced by an attempt to wrest from nature lands never designed by her for agriculture. Photo No. 224573, by J.M. Wait, 1928. The photograph at bottom shows a barn typical of many in the region. Photo No. 371075, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

When fire followed logging operations, young timber was destroyed, delaying renewal of the timber resource. The settler and mountain farmer considered fire a necessary tool, a time-honored farming practice. Nuttall observed this practice in his 1819 travels. He mentioned walking into the prairie near Fort Smith, finding it as "undulating as the nearby woodlands," but Nuttall could find no reason for the absence of trees, except "the annual conflagration." [16] Homesteaders used fire to clear land, to kill insects, and to open the woods for grazing and hunting. In the process, fire damaged many trees as it burned uncontrolled over large areas of timberland each year.

Rains then washed away the exposed topsoil, leaving the eroded land poorer and silting the downstream waters. Floods became more frequent. One-crop farming also contributed to the breakdown both of the land and the homesteader. When one place played out, the farmer just moved to a new one and began the same unproductive cycle. By 1930 and the Depression years, sub-marginal farms and abandoned homesteads had become the rule, not the exception. The thin mountain soils had become depleted. Game was less plentiful; life, more difficult.

|

| Top: Harvesting oats with homemade cradle along Big Piney Creek. Photo No. 18903A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. Middle: A bona fide homestead. Photo No. 96910. Photographer unknown. Date unknown. Bottom: Typical scene along many streams in the narrow valleys of the Boston Mountains. Photo No. 18922A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

| Old lady and spinning wheel on porch of first class typical cabin. Both essential factors in the mountain communities. Photo No. 18910A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

| Residence of John M. Sparks, Murray, Arkansas. Photo No. 19522A, probably by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

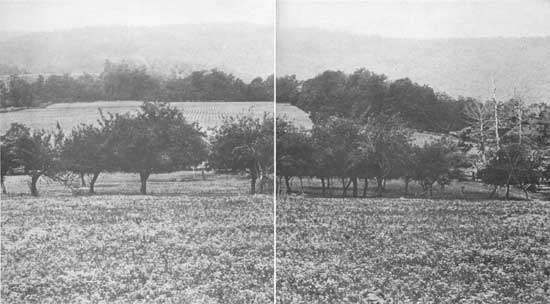

| George Gillian's farm with mountain orchard in foreground. Photo No. 18930A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

| Residence of George Gillian. Photo No. 19519A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

| Typical mountaineer family. Photo No. 18909A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

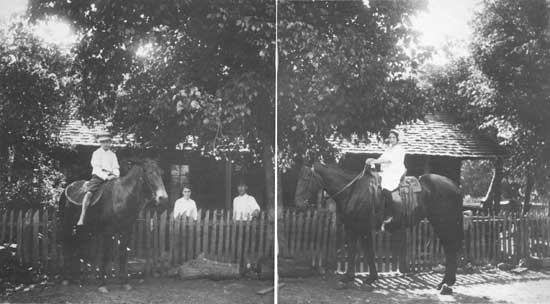

| Top: Early settlers, W. B. Malden and wife. Photo No. 195340, by J. A. Mason, 1925. Middle: Making Sorghum. Photo No. 527512. Photographer and date unknown. Bottom: Guard Elliot examines homestead entry of Allen Haley of Searcy County. Photo No. 57660, probably by C. L. Castle, ca. 1904. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap1.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |