|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 6

The St. Francis National Forest

This National Forest takes its name from the St. Francis River, one of the rivers forming its eastern boundary. Back in 1819, when Thomas Nuttall reached the mouth of this river he walked several miles into the woods. He found there a deserted settlement and came away disappointed that the vegetation had been so similar to that of the middle and northern states. Nuttall noted with eerie drama that the lack of habitation surrounded the place with "irksome silence and gloomy solitude, such as to inspire the mind with horror." [1]

Toward the end of the 19th century Gifford Pinchot himself came to this part of Arkansas. He accompanied Dr. Bernard Fernow who was then head of the Forestry Division of the Department of Agriculture. Pinchot wrote about this trip.

At Memphis I had my first glimpse of the Father of Waters, and in the Arkansas bottoms, which were then a refuge for criminals, my first contact with an outlaw community, my first look at the hardwoods of the Mississippi Valley, and my first taste of sowbelly and saleratus biscuit. The emblem of this civilization was the frying pan.

For miles on end Fernow and I rode our horses through the great flatwoods of superb Oak timber—miles of the richest alluvial soil, where there wasn't a stone to throw at a dog, and the cotton in the little clearings grew higher than I could reach from the saddle. Everything was new and strange. Every fence in the scanty settlements was plastered with signs of Ague Buster, and the people looked as if they needed it.

The Arkansas lumberjacks were tough, but very willing to talk. I got a new light on logging and sawing, learned some of the mysteries of whiskey staves and quartered Oak, collected a fine specimen of Hackberry (I have it yet), ate my first possum and found it good . . . [2]

|

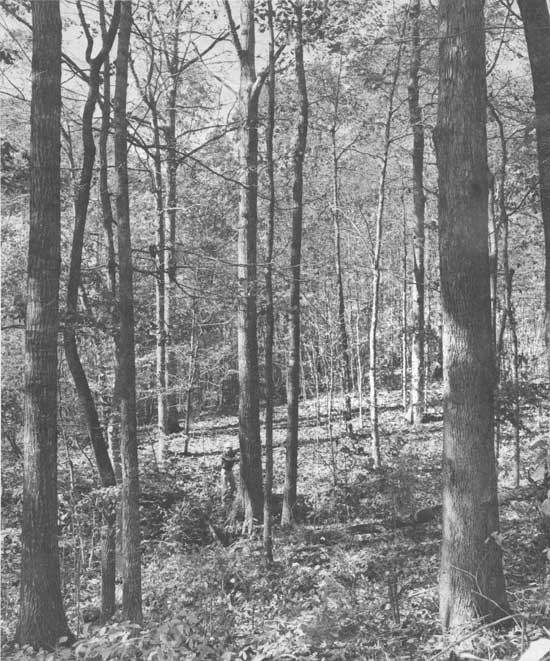

| District Ranger Bill Jackson checks tree diameter in a fine young stand of hardwood saw timber in the new St. Francis National Forest in eastern Arkansas. Photo No. 498335, by Daniel O. Todd, 1960. |

And when this land became a National Forest on November 8, 1960, there still was not a stone for miles to throw at a dog.

The St. Francis National Forest is located in Lee and Phillips Counties, between the towns of Marianna to the north and Helena-West Helena on the Mississippi River to the south. Three rivers—the L'Anguille, the St. Francis, and the Mississippi—form the eastern boundary of the forest.

Most of the forest is situated in the hilly Crowley's Ridge section of Arkansas, with some low and flat lands occurring along the rivers. Crowley's Ridge begins near Thebes, Illinois. At that point, the ridge section rises steeply 250 feet above the alluvial plain and is almost 12 miles wide. The ridge extends southward through Missouri and into Arkansas, a distance of almost 150 miles. Near Helena, the ridge rises approximately 100 feet above the delta lands and is only two or three miles wide. The sedimentary rock of the ridge is capped with loess, a wind-blown material. [3] The forest is, as Nuttall noted, more similar to the Tulip-tree-Oak forest of the Tennessee hills than to the Oak-Hickory forest of the Ozarks. [4]

The river bottomlands owe their existence and their richness to the deposits made by the river waters over thousands of years. The depth of this alluvial cover varies, but in places reaches depths of more than 200 feet.

The early Indians who lived in this area became known primarily as Mound Builders. The first mounds were used to bury the dead. Later, as the Indians became more technologically accomplished and more highly organized, the mounds became sites for worship. [5]

DeSoto is supposed to have crossed the Mississippi River at Sunflower Landing, near Helena, in June 1541. [6] Father Jacques Marquette, a Jesuit priest, and Louis Jolliet, a geographer and fur trader, visited Indian tribes at this place in 1673. [7] The first white settlement, near the mouth of the St. Francis River, was established in 1797. Sylvanus Phillips, for whom Phillips County is named, was born here, although his birthplace has since been taken by the changing route of the Mississippi River. Phillips Bayou was also named in his honor, and Helena was named for his daughter, Helen. [8]

Phillips Bayou, on the St. Francis River, was founded several years after the town of Sterling and became an important steamboat landing—even as late as the early 1900's. The town of Phillips Bayou had three large stores, three saloons, and two large sawmills. A tram road extended west into the hills for hauling logs on cars pulled by mules. Logging in the woods was done with the help of oxen. Until Helena became a river port, Phillips Bayou was the most important town and landing.

Small boats could go upriver from Phillips Bayou to other landings, but large boats could only do so if the waters were abnormally high. Today, the rivers have become silted to the degree that even small boats could not reach the town except at high water. [9]

As the hills became settled, small areas were cleared and cultivated—at least for a few years. Once the land became too gullied for use the area was abandoned. New areas were cleared for cultivation and farmed in the same manner. The hillsides that were too steep for a plow were left in timber. The merchantable trees, however, were cut and sold. The trees of small diameter, yet of desirable species, such as yellow poplar, were cut and used or sold for firewood. The cull trees were left standing. Wooded areas were used year round for grazing cattle, horses, hogs, and goats. Settlers brought their cattle to the hills for wintering on the native switch cane. Like their counterparts in the Ozarks, these settlers burned the woods in early spring to eliminate the undergrowth, the debris and the insects. The cumulative effect of these farming practices began to show in erosion and in the sedimentation of the streams. It showed in the lack of wildlife, wildlife that had once been abundant in this area. And it showed in the settlers themselves who became poorer and poorer.

|

| Cookstove used by sharecropper. Phillips County, Arkansas. Photo No. 423009, by W. K. Williams, 1942. |

Down in the bottomlands the situation was not much better. Considerable damage had occurred from overcropping and from flooding. Before levees were built, flooding was an annual occurrence, though damage to the soil was slight. The levees reduced flood occurrence to some extent, but when an overflow did occur, the resulting damage was greater. Not only did the topsoil wash away, buildings were also lost. After the major flood of 1927 few buildings remained, and by 1929, virtually all the land had been abandoned—left to go back to trees.

In an attempt to purchase and restore sub-marginal lands, the government began purchasing some of this land in 1935. The average annual income from farming, sale of livestock and timber, outside employment and pensions for people living in the area at that time came to $210 per family. Of the 74 families still living on the land, 30 percent owned land, 50 percent rented, and remainder were squatters. One-third of the lands were tax-delinquent and a considerable amount of land had gone back to the state for non-payment of taxes. [10]

In addition to purchasing and developing these lands, the Resettlement Administration had the responsibility for relocating the families affected by the land purchases. The Resettlement Administration also cooperated with other agencies to provide employment for almost 2,000 emergency relief workers in Lee and Phillips Counties.

Employment on these projects was limited to a specified number of hours in an effort to make the work go around. This part-time restriction generally required staggering work days, and necessitated a constant training program. Some of the work accomplished under the Resettlement Administration included planning and developing Bear Creek and Storm Creek Lakes; the excavation and construction of 22 miles of gravel road, winding from the northern end to the south and including the construction of five large wooden bridges. Emergency relief workers fenced 50 miles, built two fire lookout towers, strung 23 miles of telephone line and constructed almost 20 buildings for administration and recreational purposes.

|

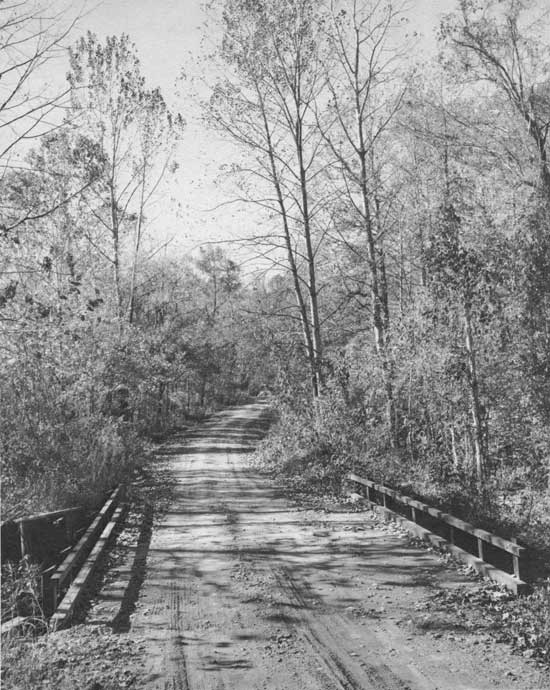

| Forest road through the St. Francis National Forest. Photo No. 498331, by Daniel O. Todd, 1960. |

The Storm Creek Lake dam was started in late 1936 and was well underway when a flood in the early months of 1937 backed the water from the Mississippi River and forced a shutdown in construction. The equipment was moved to the Bear Creek Lake site and construction began on that dam. This work was completed in 1938 and work then resumed on the Storm Creek dam.

During this period, 1935 to 1939, four agencies administered this area: The Resettlement Administration, from 1935 to September 1937; the Farm Security Administration, from September 1937 to July 1938; the Bureau of Agricultural Economics from July to November 1938; and, finally, the Soil Conservation Service. [11] On January 1, 1954 the administration of the project was transferred to the United States Forest Service. Soon after the transfer, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission applied to purchase the project. Several hundred citizens of Lee and Phillips Counties signed petitions protesting sale to the Game and Fish Commission, requesting instead that the land be given National Forest status. [12] This request was granted on November 8, 1960.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap6.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |