|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 5

World War II and Recovery

During the autumn of 1941 locations had been mapped and camera points established in the Ozark National Forest. These points would be used to compile a photographic record for scientific studies. Photographers—local and those assigned from the regional office—would make pictures from these stations on schedule each two years. [1] The comparative record of growth and land changes would be available to the public and would provide documentary evidence for forest planning and forest management, still a young science in this country

Deer season had been looked forward to all that fall. It was to open the next day. Already more than 2,000 hunters had been out in the woods in the Sylamore Ranger District, and hundreds more throughout the rest of the National Forest. [2] The season, the last one of the year, promised to be a good one.

The next day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, and deer season became lost in the shock and immediacy of a national call to arms.

During the war only food was in greater demand than wood. [3] The United States Army used more than two billion board feet of timber in 1941 to build new camps. This amount of timber would have filled a 500-mile freight train, according to the Arkansas Gazette. [4] By 1943 when the war effort required 100 million tons of steel, the country needed 120 million tons of wood. [5] The Army and Navy used lumber, plywood, and wood pulp products to construct patrol boats, decks for battleships, shipyards, laundries, recreation centers, hospitals, shipping crates, rifle stocks, and portable bridges. [6] It took wood to make the bobbins and shuttles in the textile mills to make clothing and parachutes. It took wood to make farm implements and machinery to feed the military forces. It took railway ties and timber for rolling stock to transport men and supplies. [7] And, to conserve aluminum and steel, war products that were once shipped in metal containers were shipped in wooden barrels. Oil, meat, beer, and chemicals were stored and shipped in white oak barrels. [8]

|

| Stand of white oak photographed at Camera Station #3, one of the established camera points to regularly document forest conditions. Photo No. 426418, by Clint Davis, 1941. |

|

| Barrels constructed from white oak cooperage stock. Shipping in wooden barrels helped conserve aluminum and steel for the war effort. Photo No. 426743, by Clint Davis, 1941. |

|

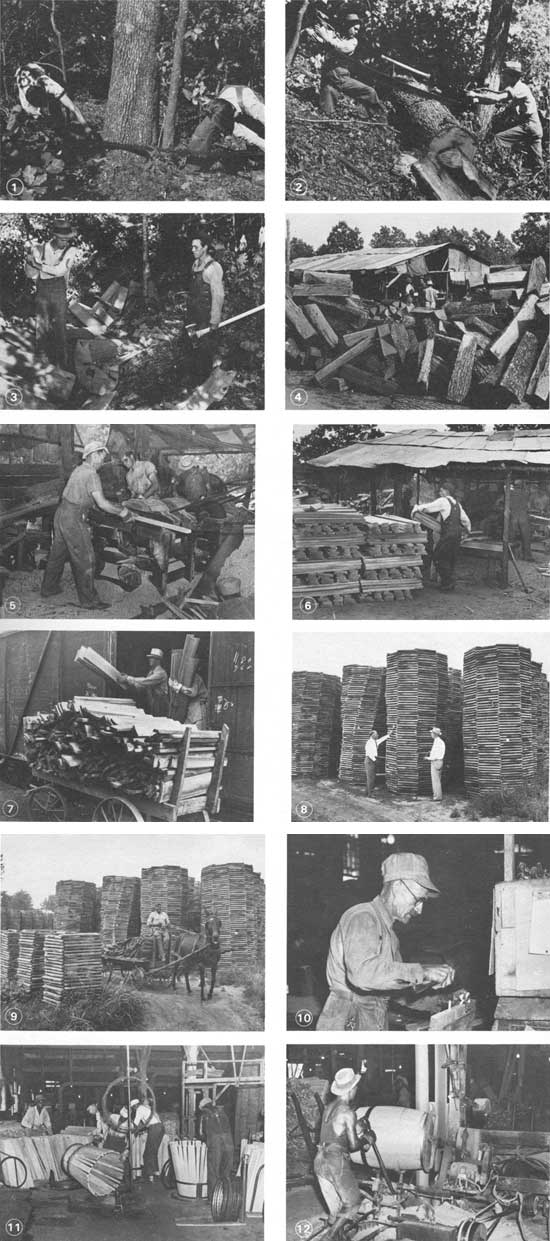

| The photographs in this series depicting the cooperage industry were made by Clint Davis in 1941. 1. Crew cutting a mature white oak. Photo No. 426716. 2. Logging crew sawing 38" bolts from white oak tree. Photo No. 426746. 3. Splitting timber into stave bolts. Photo No. 426747. 4. White oak bolts ready for sawing into rough bourbon staves at a small portable mill, called peckerwood mills. Photo No. 426719. 5. Edging cooperage staves from white oak bolts. Photo No. 426721. 6. Stacking the edged oak staves at a portable mill. Photo No. 426722. 7. Unloading white oak staves at the Chickasaw Wood Products Company in Memphis, Tennessee. Photo No. 426724. 8. Heading stock, stacked for air seasoning. Photo No. 426726. 9. Hauling heading stock to the barrel plant. Photo No. 426728. 10. Heading blanks from the Ozark National Forest. Photo No. 426728. 11. Barrell construction. Photo No. 426732. 12. First finishing operation for barrels at the Chickasaw plant. Photo No. 426733. |

Hickory sales in the Ozark National Forest in 1943 provided the skis for American and Allied alpine troops. [9] Oaks for great ship beams came from the Arkansas white oak. White oak became an important war resource because salt water would not penetrate white oak as much as other wood species. To provide the needs for each soldier took an average of five trees each year. It also took labor, and labor became a problem in Arkansas where there was plenty of the raw material, but few people. To meet the timber demands, the War Manpower Commission ordered the lumber industry to a 48-hour week. [10]

The Ozark National Forest was one of 12 National Forests in the Southern Region. The forests of the south had produced 40 per cent of the nation's timber between 1910 and 1942. [11] In that year the total stand of marketable timber in Arkansas was estimated to be 40 billion board feet, plus more than 150 million cords of younger growth with commercial value. [12] The war effort relied heavily on the nation's timber resource and on the National Forests.

Some of the needed manpower to get the timber from the forests came from German prisoners of war. Prisoners of war went to Fort Chaffee, just east of Fort Smith, Arkansas. Side camps, established in other locations, put the POW's to work. The Chickasaw Wood Products Company was one lumber outfit who used German prisoners at a camp set up in the Ozark National Forest. The camp was located on the West Fork of the Illinois Bayou, 38 miles north of Russellville. Chickasaw Wood Products Company paid for the prisoner labor, but the money went into the United States Treasury.

The camps allowed no visitors and all POW's wore the initials "PW" on all outer clothing. Area residents were notified when the Pelsor camp opened. [13] For the most part, the German POW's had been small shop or store keepers, not at all familiar with or trained for woods work. Few attempts at escape were reported at Fort Chaffee, but one Friday night, just after the camp had been established Erich Weimamnn disappeared. The Russellville Courier-Democrat reported on March 3, 1945, that the missing POW was a 30 year old blond, weighing 174 pounds and was 5 feet 8-1/2 inches tall. The prisoner was wearing the khaki uniform that had been issued. A uniform having no buttons or insignia, only "PW" stamped on the cloth. [14] The Army designated Wiemamnn as an escapee. The forest officers, however, believed he wandered off and simply lost his way back.

War priorities placed an intense demand on the Ozark National Forest for the timber resource. At the same time, the war had taken many of the men needed to manage the resource. As a result, everything took a back seat to logging activities. After the war, the men returning to work in the National Forest faced a backlog of work that had had to wait. Housing demands and the needs of the country as it recovered from war placed new pressures on the forest.

Three years after the war the Forest Service established an experimental forest for research purposes just north of Jasper, Arkansas on Highway 7. The Forest Service acquired 747 acres for the Koen Experimental Forest. In July 1950, the experimental forest was added to the Ozark National Forest. [15]

Other lands were transferred to the forest during this period. In 1954, five land utilization projects were transferred from the Soil Conservation Service. These projects had been Resettlement Administration projects under the New Deal originally. The land had been purchased under the authority granted by Title III of the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, legislation intended to correct "maladjustments in land use." The five projects transferred were the Lake Wedington and Lake Leatherwood projects in northwest Arkansas, the Marianna-Helena project, the Pine Tree project, and the Wattensaw project, all in east Arkansas.

The Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant act, authorized the Secretary of Agriculture to dispose of such lands, and the Forest Service adopted this same practice. Accordingly, all federal agencies were notified to determine if any of these lands could be used by any government agency. No federal agency made a request. Then the state of Arkansas was advised these lands were available for purchase by state agencies. One of the conditions of sale, however, was that these lands had to remain open for public use. Another condition was that the federal government retained mineral rights. Because of these restrictions, the price of the land was reduced by 30 percent of appraised value. State agencies were to be allowed to spread payment over 25 years. All five projects were applied for. The University of Arkansas applied for the Pine Tree and the Lake Wedington projects. The University eventually bought the Pine Tree project but failed to carry through on the purchase of the Lake Wedington project. The Arkansas Game and Fish Commission applied for both the Marianna-Helena and the Wattensaw projects. The Commission bought the Wattensaw project, and dropped negotiations on the Marianna-Helena project when local opposition developed. The city of Eureka Springs was granted the Lake Leatherwood project.

During the time of appraisal and negotiation, these projects were administered on a custodial basis by the Ozark National Forest. Special uses, such as grazing, recreation and the gravel operation, continued. After appraisal began, timber was not cut, except possibly in the Marianna-Helena project. The three units in east Arkansas were too far removed from the main part of the National Forest to be managed by regular forest personnel. Instead, Soil Conservation Service managers administered these lands.

In November 1960, President Dwight Eisenhower added the Lake Wedington Land Utilization Project, covering 14,395 acres, to the Ozark National Forest. At the same time, the Marianna-Helena project, covering 20,611 acres, received National Forest status and was designated the St. Francis National Forest. [16]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap5.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |