|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 4

New Directions and Hard Times

The changing attitudes and growing acceptance of the National Forests resulted in a directional shift—efforts which had formerly been channelled into custodial duties and into the defense of the woods from fire and trespass, began to go into resource development and improvement.

The country sat back and enjoyed a period of stability following World War I, then got to its feet to experience the heady exuberance of the last days of the "roaring 20's." It was a time for big plans and action, before the economy crashed and people became dazed by the desperation of the Depression.

In the Ozarks this period got underway with the establishment of four federal game refuges by the proclamation of President Calvin Coolidge. This action underscored the permanence of the Ozark National Forest, but this action, unlike other governmental pronouncements, had great popular appeal, especially to local hunters and sportsmen.

Hunting and fishing to the Ozark mountaineer, or would-be mountaineer, is more than sport. It is survival and it is ritual. Hunting might rate as the 11th article in an Ozark bill of rights. Hunting in Arkansas is perceived as a God-given right, a joy, a perennial call to the wild, with which neither man nor government dare interfere. Schools close—did then, and still do today. Hunting in Arkansas has drawn both the celebrated and the spectacular.

Frederick Gerstaecker, a German immigrant and one of the first men to come hunting in Arkansas, described his adventures in his 1859 book, Wild Sport in the Far West. The far west at that time was Arkansas. Gerstaecker wrote about the bear, elk, deer, mountain lion, wolf, fox, turkey, and the streams of fish. And as the word went out, the people moved in. By the 1920's the woods had taken on a peculiar silence. Few deer could be seen. Wild turkey and bear had become the stuff of mountain dreams and campfire stories. Legend became the final habitat of the wolf, so thoroughly had parts of the state been hunted and trapped.

The game refuges were the first steps taken to restore the balance of the local fauna. In the late 1920's and early 1930's the sighting of a single deer was enough to generate considerable local comment. The refuges succeeded and led to the eventual establishment of state and federal wildlife management areas within the National Forest lands of Arkansas. By the fall deer season of 1940, the Sylamore Ranger District alone counted 3,600 hunters. The deer herd in Stone and Baxter Counties had increased under intensive wildlife management from 24 deer in 1924 to more than 3,000 deer in 1942. [1]

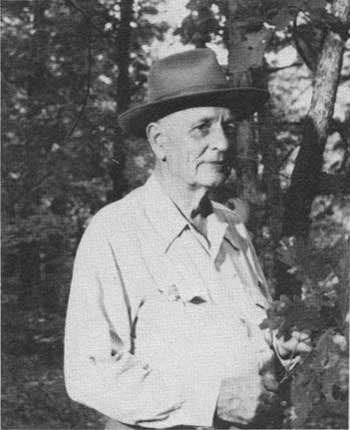

During this time Henry R. Koen served as the forest supervisor. He assumed this position in 1922 and held it until 1939, the longest period of administration by a single supervisor in the forest's history. Koen had grown up in Arkansas. He received his first Forest Service appointment in July 1913 as forest ranger in the Sylamore Ranger District. [2] He was there when they built the first forest road. To many men who worked for the Forest Service Koen was "Uncle Henry." To others, he was an exacting taskmaster, a rigid, almost humorless man, yet one to be respected. There can be little doubt of Koen's influence on the forest administration and on the people of the area. Hundreds of newspaper articles over the years of his employment and well into his retirement detail his activities and kept his name in the news. Most of Koen's forest career was spent in Arkansas. Only briefly did he work in Virginia, North Carolina,and in the regional office in Atlanta, Georgia. [3] He retired in 1943. Five years later an experimental forest north of Jasper was named in his honor. [4]

|

| H.R. Koen. From the files of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forest. Photographer and date unknown. |

|

| Top: Green Motorway through game refuge. Photo No. 385889, by W. C. Hadley, 1938. Top Middle: First day's kill of two bucks by one hunting party. Photo No. 385890, by W. C. Hadley, 1939. Bottom Middle: Planting fingerlings in stream. Photo No. 218559, by J. M. Wait, 1927. Bottom: The start to the Moccasin Gap Game Refuge with turkeys to be released. Photo No. 218548, J. M. Wait, 1927. |

Beginning also in the 1920's, forest employment and timber operator payrolls began increasing. The next thing, petitions began circulating asking for the forest to be enlarged. In 1928, a Presidential proclamation by Coolidge added 122,489 acres to the forest. [5] President Franklin D. Roosevelt increased the gross acreage by 389,935 acres in 1936; and, in 1940, Roosevelt transferred the Boston Mountain Land Utilization Project to the Ozark National Forest, adding another 31,681 acres. [6] One of the final land actions of this period came in 1941 when Roosevelt by executive order transferred the Magazine Mountain District from the Ouachita National Forest to the Ozark National Forest. This order added 131,697 acres to the Ozark National Forest. [7] Most of the land in the Magazine Mountain Ranger District had been acquired during the years of the Depression under the programs of the Rural Resettlement Administration.

The land acquisition program, which had begun as early as 1919, had brought large numbers of old fields into the forest. Most of these fields were not restocking themselves, and in the fall of 1928, plans were made to establish a small pine nursery to furnish plantings for some of these fields and marginal lands. A small nursery was started at Fairview in the Pleasant Hill Ranger District in the spring of 1929. Seed was sown for 100 million seedlings, but difficulties in securing an adequate source of water caused this site to be abandoned.

After investigating several sites within forest boundaries, the Forest Service leased land from Arkansas Polytechnic College (now Arkansas Tech University) in Russellville. An equipment building was completed and the first seed sown in March 1930. The late sowing, however, resulted in seedlings insufficiently developed for first year planting.

|

| The nursery at Russellville. Photo No. 276762, by J.M. Wait, 1933. |

|

| Photograph of nursery made from a negative found in the files of the Ozark National Forest. |

A survey conducted in 1930 showed more than 12,000 acres in need of planting. The capacity of the nursery was increased, a new water system installed, and the nursery was sown to capacity by the spring of 1932. It remained in operation into the 1940's at which time the buildings and other improvements were turned over to the college. [8]

|

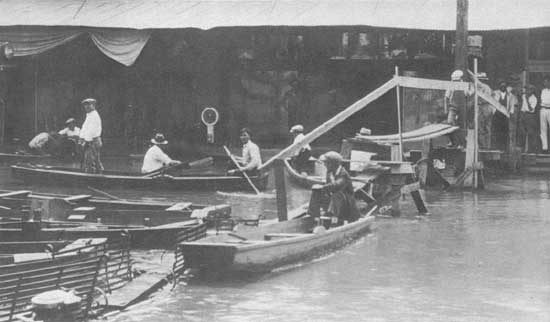

| Since the first settlement, the Arkansas River presented a formidable barrier to travel. Dardanelle became an important steamboat landing and crossing, but the ferry soon became inadequate. It was displaced by a pontoon bridge said to be the longest pontoon bridge in the world. This structure (2nd photo from top) rendered a somewhat interrupted but important service for a period of 35 years. The floods of 1927 and 1928 frequently rendered the old bridge useless. Photo No. 230786 by J.M. Wait. 1928. Top: Lake Village, Arkansas during flood of 1927. Middle Bottom: Flood waters over west end of the Dover, Arkansas bridge. Photo No. 230754, by J.M. Wait, 1928. Bottom: Overflowing streams on the skirts of Waldron in Scott County. Photo No. 218532, by J.M. Wait, 1927. |

|

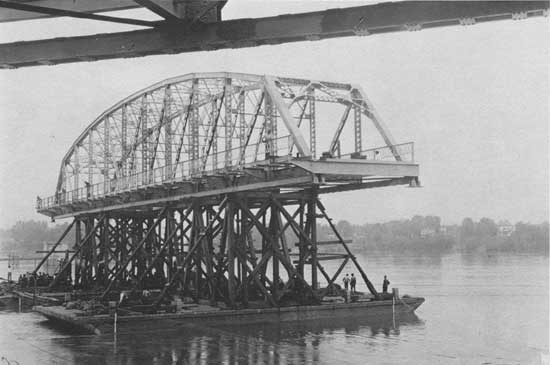

| Dardanelle Bridge. The first span after being raised (top) is turned in midstream. Once in place between piers, (bottom) the span is lowered to proper position. Both photographs by J. M. Wait, ca. 1928. Photo No. 230799 (top); Photo No. 230800 (bottom). |

The Civilian Conservation Corps

The creation of the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1933 as an emergency relief measure was, at first, considered a temporary measure, but one which the Forest Service hoped to use to advantage. Rangers, in fact, received instructions to get as much work done in the forest as possible during the six months the program was supposed to last. [9] The first camps were temporary affairs, but when it became apparent that the program would continue, permanent camps were constructed. In all, nine camps were located in the Ozark National Forest. The Magazine and Boston Mountain Ranger Districts had not yet come into the Ozark National Forest, but each of these units had a Civilian Conservation Corps camp. The Boston Mountain Camp was located at Devils Den State Park, and the Magazine Mountain camp was set up at Corley. At one time there were 37 camps established in Arkansas. In addition, some of the Ozark National Forest Ranger Districts had one or more Works Progress Administration projects. [10]

The large contributions of money and manpower provided by these programs made possible for the first time an adequate transportation and communication system for fire control and administration of the forest. These manpower programs also provided administrative improvements such as equipment depots, lookout towers, and ranger stations. Most forest recreational facilities were planned and constructed during this period.

Moreover, men, both local and from all over the country, found work to do while earning money for themselves and their families. More than 75,000 Arkansans enrolled in the Civilian Conservation Corps. The cost to maintain a junior enrollee for six months came to $500. Of this amount $90 went to the family or dependents, $48 went into savings, and $48 went to the enrollee in cash. The remaining $320 went to house and feed the enrollees and to operate the camps. [11] An additional benefit to the Forest Service came from having enrollees living and working in the forests, where they received, firsthand, an appreciation of the benefits of the forests and an understanding of the damage caused by uncontrolled fire.

|

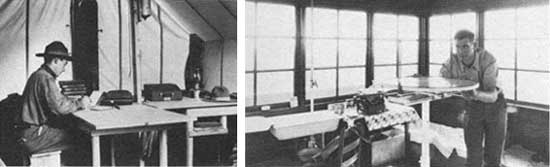

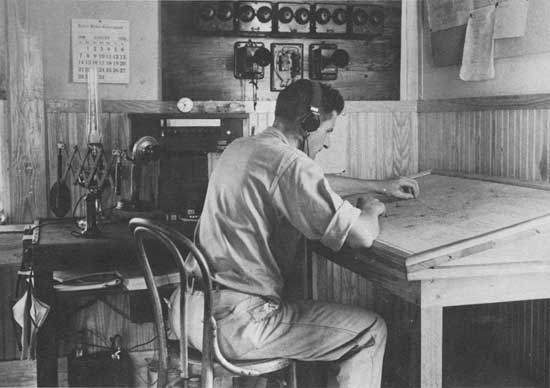

| Top: The District Ranger, if necessary to suppress the fire, calls the road crew into action. Photo No. 224566, by J.M. Wait, 1928. Middle, left: Office tent at planting camp. Photo No. 266111, by J.M. Wait, 1932. Middle, right: Lookout tower at Fairview. Interior view of cabin showing CCC enrollee on lookout duty. Photo No. 335365, by J.M. Wait, 1936. Bottom: Photo No. 371347, Sam Horne in the fire dispatch office, Ouachita National Forest, August 1938. Photo No. 371347. |

|

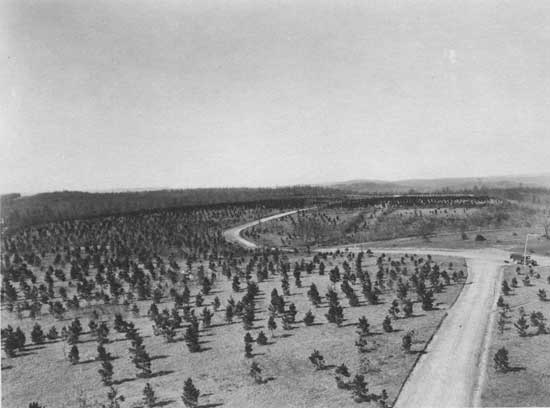

| Timber stand improvement took place over large areas of the National Forests, releasing commercial growing stock from the competition of cull or weed trees. Manpower and money reduced fire loss dramatically while an expanded prevention program aided in fire reduction efforts. The photograph to the left shows trees being planted. Photo No. 266114. The Fairview planting site is shown below as seen looking north from the lookout tower cabin in 1936. In Arkansas, more than 19 million trees were planted. Both photographs by J.M. Wait. |

|

| The Civilian Conservation Corps in Arkansas built 5,177 bridges of all kinds, strung 6,270 miles of telephone lines, and built 5,356 miles of truck trails and roads. The work began in April 1933 and ended in July 1942. [12] Top: Enrollees with back pumps putting out burning embers. Photo No. 371158, by Bluford Muir, 1938. Middle Top: Civilian Conservation Corps boys going to work. Camp Moore. Photo No. 335346, by J.M. Wait, 1936. Middle: Foot trail, Bayou Bluff Camp. Photo No. 357004, by J.M. Wait, 1937. Middle Bottom: Blanchard Springs Dam under construction. Photo No. 365693, by J.M. Wait, 1938. Bottom: Civilian Conservation Corps constructing first building at Camp Victor, a side camp for Camp Pelsor. Photo No. 335345, by J.M. Wait, 1933. |

|

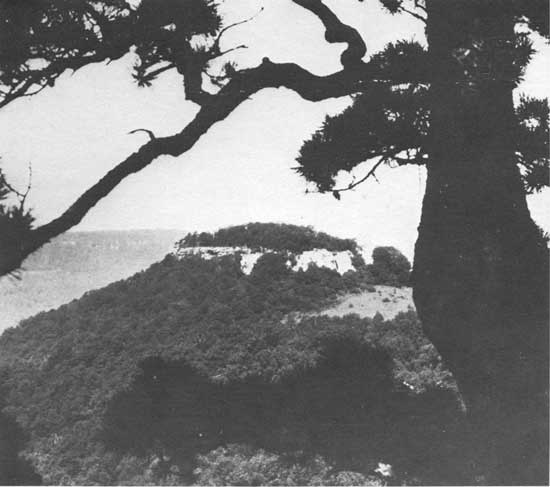

| Top: The Ozarks as seen in the 1930's. Scene along south boundary of the Ozark National Forest on Grape Vine Mountain Road. Photo No. 335367, by J. M. Wait, 1936. Bottom: Sam's Throne, famous through local legend as being the spot where a vast horde of gold has been deposited. Photo No. 371060, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

|

| Top: Arkansas mountaineers seated on the porch of their log cabin. Sylamore District. Photo No. 371218, by Fluford Muir, 938. Bottom: Old stage changing station and tavern. Old Wire Road between Fort Smith and Little Rock. Built prior to Civil War. Photo No. 371107, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

|

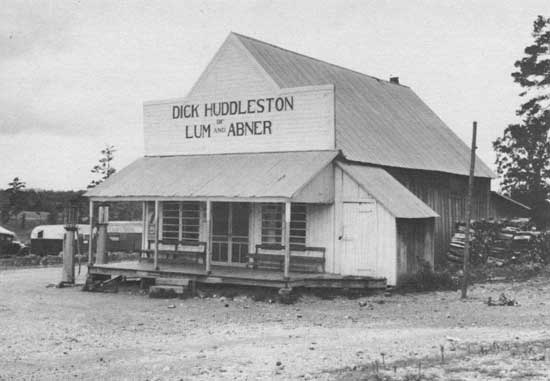

| Top: The drug store in Pettigrew, Arkansas. Favorite meeting place for Saturday night politicians. Photo No. 371253, by Bluford Muir, 1938. Bottom: Dick Huddleston's store at Pine Ridge, Arkansas, which was made famous by the Lum and Abner radio show. Photo No. 371476, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

|

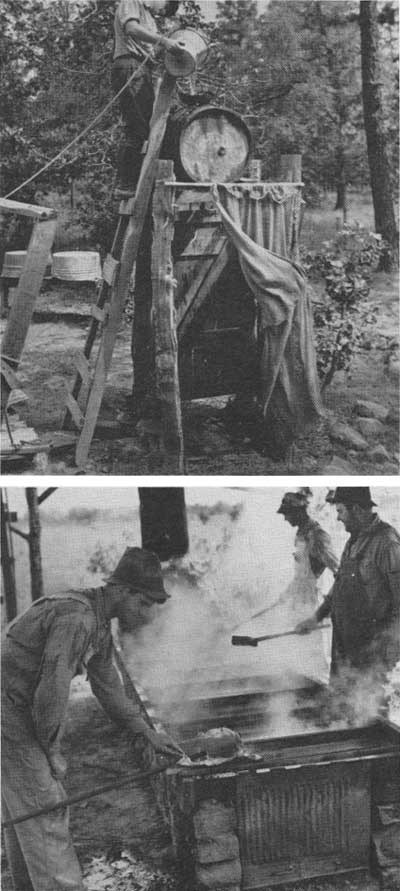

| Top: Homemade shower. Bottom: Making sorghum. No serial numbers. Photographer unknown. 1938. |

|

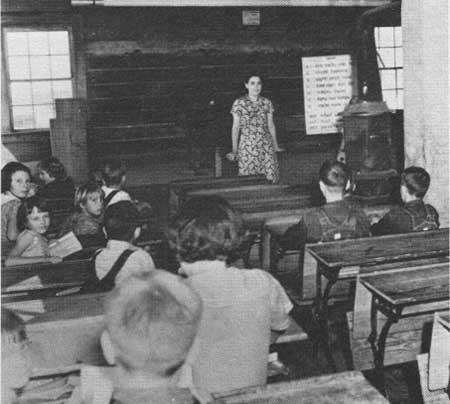

| Top: General view of ferry on White River near Calico Rock. Photo No. 371243, by Bluford Muir, 1938. Middle: School at Corley. No serial number. Photographer unknown, 1938. Bottom: The Cold Springs schoolhouse with the school children and teacher. Photo No. 371079, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

|

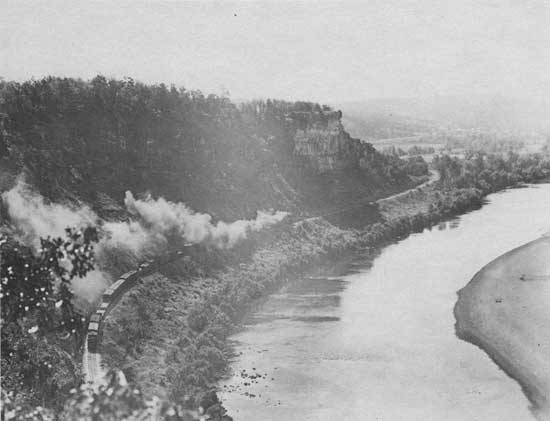

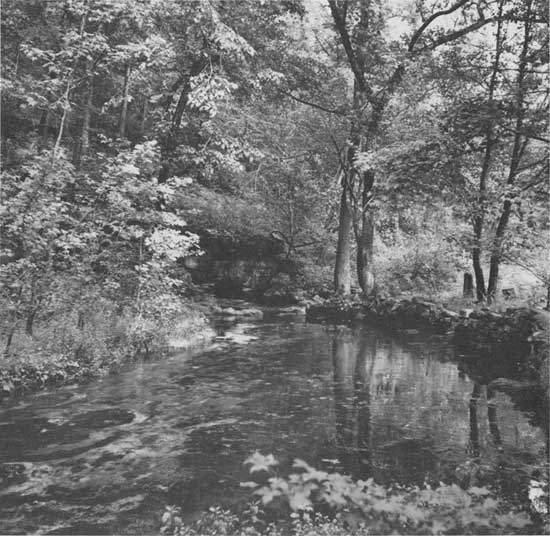

| Top: Scene on White River. Town of Norfork in distance. Photo No. 356978, by J. M. Wait, 1937. Bottom: Big Springs on Livingston Creek in Sylamore District, Photo No. 371230, by Bluford Muir, 1938. |

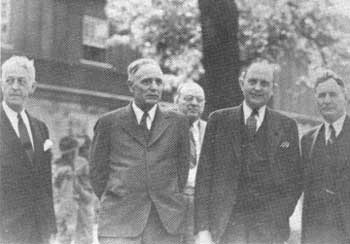

This period came to a close with the construction of a new headquarters facility in Russellville. The building, a departure from standard federal construction, won for the architect an award. The two-story building of native stone and timber contained 23 rooms and was one of the few buildings constructed by the Treasury Department for Forest Service use primarily. The money to pay for construction came from a special Congressional act. Congressman D. D. Terry helped secure passage of this legislation and was present for the dedication ceremonies on May 2, 1939. The region took pride in this new building and recognized Henry R. Koen as the man most responsible for seeing the project through. [13] The May issue of "The Dixie Ranger," the regional newsletter, commented:

...one couldn't see the town for the people. The whole state of Arkansas rejoiced with Mr. Koen and considered the new building a symbol of the dedication of Mr. Koen's services to a program to rebuild and promote the . . . resources of his native State.

This building housed the administrative staff of the Ozark National Forest, with the forest supervisor having charge of the building as well as the forest. During the remainder of the Civilian Conservation Corps program, the supervisor's staff filled the entire building. Later, when this program ended and the staff reduced considerably, the Forest Service shared the building with several other government agencies. In 1942, the custodial responsibility for the building was turned over to the Public Buildings Administration, which in 1948 became the General Services Administration.

|

| The dedication of the new federal building in Russellville, May 2, 1939. (L to R) Ferdinand A. Silcox, chief, U.S. Forest Service; Henry R. Koen, supervisor, Ozark National Forest; J. W. Hull, president, Arkansas Technological College; Congressman D. D. Terry. No. photo number. By J.M. Wait, 1939. |

|

| The Ozark National Forest's new headquarters. Construction completed in 1939. A departure from standard federal construction. No serial number. Photograph by J.M. Wait, 1939. |

This new headquarters building was the fourth home of the Russellville headquarters. Following the move from Harrison in 1918, the Forest Service opened offices in the Harkey Building on West Main Street. The headquarters then moved to the second floor of the Courier-Democrat Building on South Boulder, and later, moved to the second floor of the Elko Building on South Commerce. The Elko Building has been demolished to make way for a new bank.

In 1939, the construction plans did not include air conditioning, although the architect thought it wise to at least install the ducts so that future air conditioning could be added at considerable savings. Koen, reportedly, ruled against any possible air conditioning, ducts or whatever, fearing this might make the staff less inclined to get out in the field. The cost to install air conditioning in 1960 came to almost $150,000, just about the cost of the original construction.

The headquarters became known as the Henry R. Koen Building in April 1979, officially honoring the former forest supervisor. Koen family members and citizens of Russellville had petitioned the Forest Service to rededicate the building. Senator Dale Bumpers helped secure the legislation necessary to name a government building in honor of an individual, and 40 years after construction, the crowd gathered once more to pay tribute to Henry Koen.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap4.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |