|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 3

The Annual Conflagration

Fire. Fire prevention and fire fighting occupied the major portion of the forest officers' time and energy. Beginning in 1910, special efforts were made to detect and suppress all fires, forest???wide. Fire guards, lookout men, and supplemental firefighters were employed. Blanket protection remained in effect until 1913. Each year, however, a greater percentage of the forest burned.

The Forest Service came to the conclusion that the increase in fire stemmed from the practice of hiring local firefighters. The local people, with few sources of ready cash, turned this situation to advantage, setting "job fires"—fires deliberately started so that one might be hired to put the fire out. In addition to those people looking for a supplementary income, there were other folk who hoped the National Forests would be abolished altogether if the land could not be protected effectively from fire. This notion may have been more believable after 1910, when more than a half million acres of National Forest land were eliminated as a result of public and political pressure. Grudge fires, too, accounted for part of the growing number of fires. Grudge fires were set against neighbors, against the Forest Service, in general, or even against a particular forest officer, to retaliate for any sort of offense. In 1913, the fire condition reached its worst. In one small district more than 144 fires destroyed 50,000 acres. [1] And with the end of that fire season, the supervisor, Francis Kiefer, stopped forest-wide protection.

Francis Kiefer had replaced Fitton as forest supervisor. Kiefer, described in the records as a brilliant young man, had studied forestry in Michigan. [2] He came to the Arkansas National Forest as a forest assistant in July 1908, distinguishing himself by his executive talents and his ability to get along with the local people. Soon, Kiefer was recommended for the position of forest supervisor of the Ozark National Forest. Samuel Record, however, opposed the promotion because of Kiefer's age. Kiefer was 21. In October 1909 Kiefer received his promotion to supervisor, although he received no salary increase. [3]

|

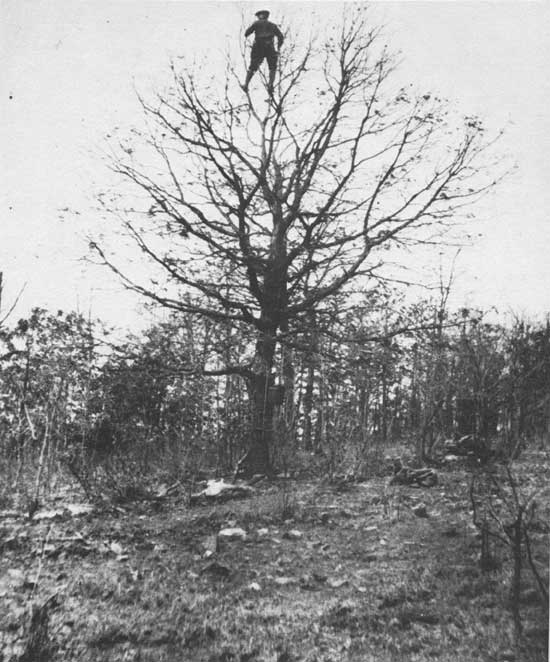

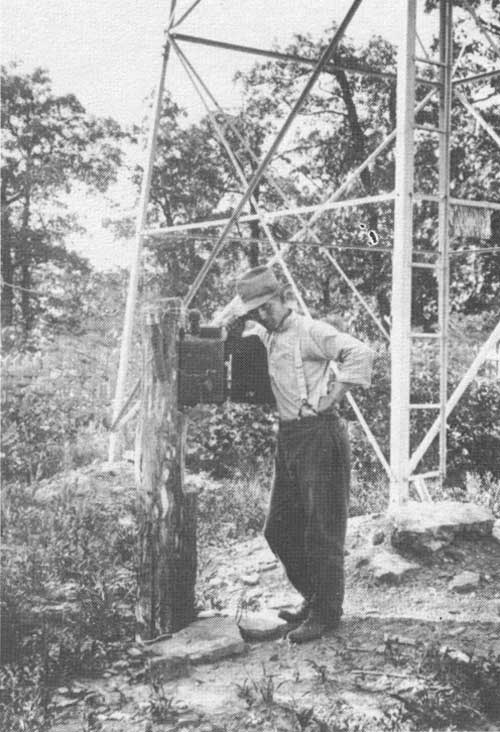

| Forest officer using tree as observation point. Telephone box attached to tree trunk to report if any fires are discovered. Photo No. 224561, by J.M. Wait, 1928. |

Frequent field trips kept Kiefer close to his rangers and also to the people who lived in and around the forest boundaries. On one of these trips in March, 1911, Kiefer ran into a series of fires. Frank C. W. Pooler, an assistant district forester, had accompanied Kiefer and described the fire situation, which might have been typical of that period. Their tour began the night of March 15. By Sunday, March 19, Kiefer and Pooler had reached the lookout tower at Pine Top Mountain. They saw several fires in one forest district and proceeded on horseback to the worst of the fires, located near Little Brushy Creek.

Kiefer and Pooler joined other firefighters. Together they worked through a terrain unpredictably cut by bluffs and ledges. They worked from 6 p.m. Sunday until just after one o'clock Monday morning. Pooler left the fire crew about midnight to search for water. He encountered high bluffs and returned empty-handed. When he reached the fire site, he found himself several hundred yards ahead of the fire crew. Pooler had reached a ledge, no wider than ten steps. He tried to establish a fire line at this point, beating out a fire in a long log. He walked along this burning log several times, stepping cautiously across and walking along the coals because he knew the edge of the bluff was not far from the fire, although not visible in the dark.

Shortly, Kiefer and the other crew members joined Pooler and helped him put out the fire. Kiefer and Pooler then stood alone at one end of the log. Kiefer, unaware of danger, took a step backwards. He fell, sliding on his belly, feet down, and went over the cliff.

|

| Francis Kiefer, looking at Black Oak timber at Mars Ranger Station, Searcy County, Arkansas, May 1910. Photo No. 91867. |

To reach Kiefer the fire crew had to work around the bluffs. The round-about route covered almost a quarter of a mile. They found Kiefer alive, but seriously wounded, with compound fractures of both bones of his lower leg. Ranger Ben Vaughan and Pooler stayed with Kiefer while two other men went to one of their homes for a cot and quilts. It took two hours to carry Kiefer out. By the time they reached the house, a doctor who lived eight miles away had arrived. The doctor gave Kiefer morphine and requested additional medical assistance. A second doctor arrived at 9 a.m. the next day. Kiefer's leg was then set and put in a plaster cast. The next day, one of the doctors and Pooler loaded Kiefer in his spring cot onto a wagon for the 35-mile drive to Morrilton, Arkansas, the nearest rail station. Kiefer was to go on to a hospital in Fort Smith. Seventeen hours later, the men arrived at Morrilton, only minutes before the train departed. Pooler had Kiefer and his cot placed in the baggage car for the trip. An ambulance met them in Fort Smith. The next morning, Kiefer's leg was re-set. Besides the broken bones of his compound fracture, he had badly wrenched his back, but fortunately, had sustained no internal injuries. Kiefer spent almost eight weeks in the hospital. In those days, Forest Service employees received no compensation for injuries incurred in the line of duty. Moreover, Kiefer did not even receive sick leave to cover his lengthy period of confinement. [4]

Kiefer, like many young foresters, had come to the Forest Service just after college. Such men came with idealism and dedication, and they needed it. Forest Service work was demanding, especially in the newly established forests of Arkansas. The conditions were harsh, the pay poor, and, as Kiefer learned, the fringe benefits almost non-existent. [5] Kiefer's first appointment paid $83 a month, and, as in most cases, the ranger had to furnish his own horse and saddle. [6] Even as late as 1920, rangers received, at best, inadequate accommodations. Only 45 of 210 ranger stations in the country had running water, and just three could boast of a bathtub. [7] To compound the difficulties, the work force in Arkansas was extremely small—a few men who faced an almost insurmountable amount of work to be accomplished on a pitiably meager budget. [8]

|

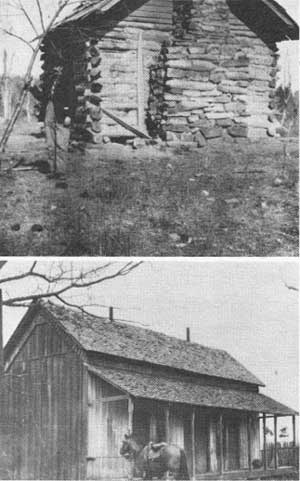

| Top photo: Showing improvements upon proposed Dennard Ranger Station near Dennard. Photo No. 74516, by D.P. Johnston, 1908. Fox Ranger Station purchased by the Forest Service in the summer of 1909. Unnumbered photo by Francis Kiefer, 1915. |

To compensate, there existed in those early years of federal forestry a recognizable sense of excitement, of importance in the work to be done. High standards of expectations had been established. Foresters closed ranks to prove practical forestry could and would work in this country. They worked to convert the skeptical citizen, as well as hostile vested interests. Farmers, ranchers, sheepmen, lumbermen, and politicians often saw no immediate value in long-range forest management practices. The Forest Service faced formidable opposition, nationally and locally.

In the Ozarks lived descendents of men once described by Davy Crockett as "the real half-horse, half-alligator breed such as grow nowhere else on the face of the universal earth but just around the backbone of North America." [9] Ozark attitudes about land use ran deep, particularly the annual practice of burning the woods. An inspection report prepared in 1909 noted that the Forest Service did have many friends in Arkansas—people who were law-abiding and who respected the rangers as men with a job to perform. These people wanted the law to be enforced equally and to see everyone treated alike. H. B. Jamison, in this report, also noted that there seemed to be many misunderstandings about Forest Service policy and practice. He recommended public circulars as one means of clearing the air; however, Jamison recommended that the circulars should not be written using long sentences and "words of whose existence the Arkansaser never dreamed." [10]

The forest ranger had to work with all the mountain people, and many rangers encountered less than law-abiding folk. For years, for generations, the Ozark people had used public lands without restraint. Stock ran at large; timber was cut with no regard for ownership; the woods were burned at will and whim; timber speculators acted with little regard for legal land titles. The establishment of the National Forest had brought regulation and control: a situation that did not always agree with the mountaineer way of life.

This was the organization and field situation Francis Kiefer and the early officers of the Ozark National Forest faced. The first two years of the Forest Service administration passed relatively peacefully though, with no increase in the number of forest fires. Forest officers travelled through their districts, working to advise people of the forest regulations and working to persuade the mountain people that it would be to their advantage to protect and manage the forests. Meanwhile other interests and politicians worked to have the forest abolished. Many residents seemed unsure about how many followers the Forest Service was winning to the side of conservation, and the calm of 1908 and 1909 might have reflected a wait-and-see attitude.

Wiley Hughes of Retta, Arkansas, near the Bayou Bluff Recreation Area, was an early convert. He admitted that he had burned the woods, but in March 1908, Ben Vaughan had been working his way up the bayou to Oak Mountain. Vaughan talked to Hughes about woods burning. Hughes said he never again burned the woods or used his influence to have the woods burned. "I told the boys woods burning must stop, for Vaughan would run down the guilty parties with his dogs." [11] Vaughan's dogs actually had limited success in tracking down fire starters, but by using his dogs Vaughan quickly convinced the public that the Forest Service at least meant business.

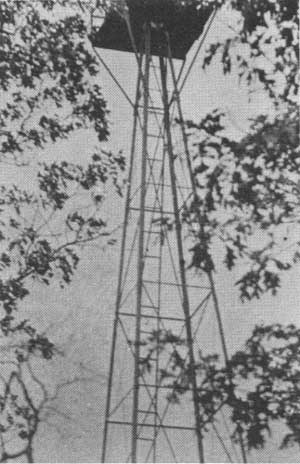

After the bad year in 1913 and after Kiefer discontinued forest-wide fire protection, one fire guard was assigned to each of two towers—McGowan Tower in the Sylamore Ranger District, and Turnpike Tower in the Bayou Ranger District. The guards received instructions in 1914 to use their best efforts, singlehandedly, to protect the eight to ten thousand acres surrounding each tower. From January until March 12 not a single fire burned in the McGowan area, but on that day, winds and low moisture contributed to three fires set in that district and burned almost 90 percent of the area. After that, the fire guard was removed and no further efforts were made at protection. The Turnpike Tower area also lost heavily to fire that year, although protection in that area was continued. The rest of the forest received no protection.

|

| Top: Using blood hounds as an aid in apprehending incendiary woodsburners. Photo No. 246332, by J. M. Wait, 1930. Top Middle: Just as the trail was picked up. The smoke of the fire can be seen in background. Photo No. 246334, by J. M. Wait, 1930. Bottom Middle photo: Distant view of Civilian Conservation Corps enrollees fighting fire. Photo No. 371166, by Bluford Muir, 1938. Bottom: Lookout at telephone at Devil's Knob Tower. Photo No. 18918A, by Ralph Huey, 1914. |

|

| Forest officer extinguishing fires with water bag equipment. Photo No. 527509. Photographer unknown, ca. 1911. |

|

| McGowan Point Lookout Tower. No serial number. Photographer unknown. |

By way of comparison, in 1913, when protection forces were larger, 52,452 acres burned. In 1914, when only two areas received token protection, the total acreage burned was not proportionally greater—approximately 12,500 acres more than in 1913. [12] Such figures might support the opinion that most of the fires from 1910 to 1913 had been job fires. Such statistics, however, might also reflect improvements in record keeping rather than revealing a cause and effect relationship or indicating levels of performance.

Beginning in January 1915, fire protection efforts became concentrated on areas where satisfactory reproduction of trees had become established. Each year the amount of land in these protective areas increased. By June 1922 the Forest Service began to believe they were winning the people over, and the next year plans were made once again for forest-wide fire surveillance.

|

| Self-portrait of J.M. Wait. Photograph through courtesy of Mrs. Lola Ross, Dover, Arkansas. Mrs. Ross is Wait's sister. |

Efforts at public education began in July 1925. James Maurice Wait, a ranger, began traveling as Fire Prevention Lecturer throughout Arkansas, conducting programs about the destructiveness of fire and the benefits of the National Forests. Wait used pictures to back his arguments. At community gatherings within the Ozark and the Ouachita National Forests, he showed glass lantern slides and moving pictures. Wait's programs drew audiences of varying sizes—sometimes a dozen, sometimes 500 persons. The movies which Wait took to the Ozarks were, in many instances, the first moving pictures seen by the mountain people. He recounted in a report an amusing incident in connection with one evening program.

I had arrived at a small school-house rather early in order to have time before my program began, to do some much needed work on my projector. I had just begun the work, about 4 o'clock in the afternoon, fully four hours before time for the program, when a lady with a large flock of young Americans 'bringing up the rear,' made her appearance and selected a position on a seat just in front of the projector. There they seemed to be immovably fixed. My work was completed and along about 7:00 P.M. the audience began to arrive. The lady and her children, the latter no doubt having been previously instructed as to how to proceed on this occasion, retained their position, but evidently were, about 30 minutes before the time for starting and as the house was by this time filling rapidly, ill at ease. Seemingly they experienced some anxiety about something. About this time Mrs. Hartman sat down in a seat just behind the lady and then the cause of her anxiety was learned. She wanted to know if it was not about time to turn the seats around. The lady was of the opinion that everyone in the audience would have to look through the small opening in the front of the projector, and for that reason that it would be necessary to turn the seats around. When Mrs. Hartman pointed to the screen on the wall and explained that the pictures would be seen there she exclaimed, 'Well, well. I've got a back seat ain't I.' [13]

Wait photographed the forests, the communities, and the activities within them as he travelled. Many of his slides were made from these photographs. Wait's photographs form a large part of the documentary collection of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests, one of the few such collections still in existence today.

|

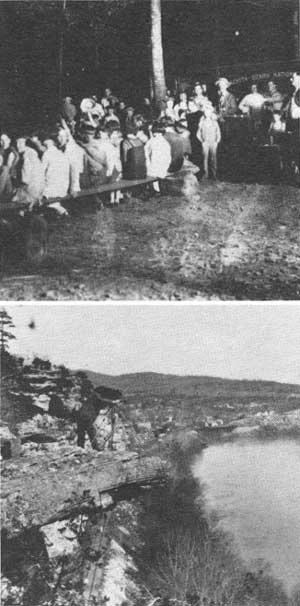

| An open air forests fire prevention program. Photo No. 211778, by J.M. Wait, 1926. The bottom photograph might possibly be one of Wait, as he worked in the Ozarks. |

Wait travelled in a specially rigged van. In the first year on the road, the rig proved too heavy for the truck frame. Maximum speed on a good road—and in Arkansas there were not many—was 15 miles an hour. He camped along the way, sometimes taking his wife Mollie and foster child with him. On some days in the field Wait spent many hours slogging through mud and trying to get the van loose from the mire. He crossed creeks even though the water was high enough to run through the cab. Occasionally he had to find mules to tow him across streams. Once, at Gravelly, Arkansas, an electrical storm frightened half of the audience away, yet more than 200 remained for the end of the program. And in 1928, an epidemic of mumps, measles, and influenza reached such proportions in the Ouachita National Forest districts that public meetings had to be cancelled. During his first full year on the road, Wait spent 288 days in the field. He travelled more than 5,000 miles, spoke at 216 engagements, and talked to more than 42,000 persons. [14]

|

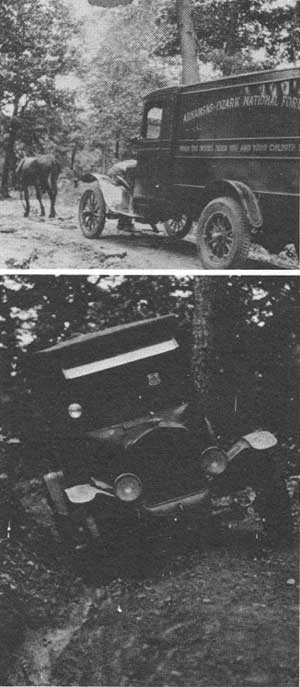

| At last! A Ford in society... at first this creature was unwelcome, but the steepness of this road required the society of this creature to get the Ford out of difficulty. On road between Mt. Judea and Bass. Photo No. 205003, by J.M. Wait, ca. 1925. Wait, in his journals, often reports difficulty on roads like the one shown in Photo No. 205006. J.M. Wait, 1926. |

Wait spoke eloquently for the trees and earned the respect of the mountaineer especially. Over the years these lectures brought about new attitudes, and today, few people would deliberately set fire to the National Forests.

|

| Top: High bluff on Little Piney Creek near Murry's Chappell. Photo No. 205002, by J. M. Wait, ca. 1925. Middle: Big Lick School, Indian Creek. The fire prevention truck arrived about 10:00 a.m. At that time there was a total attendance of two children at this school. The arrival created quite an interest which swelled the attendance to a total of six in the afternoon. Photo No. 205661, by J. M. Wait, ca. 1926. Bottom: In camp on Little Piney Creek at Murry's Chappell. Photo No. 205001, by J. M. Wait, 1925. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap3.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |