|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 8

Years of Challenge

Earth Day, April 22, 1970, may have served as the catalytic ingredient, providing the public a stronger voice in matters concerning ecology and world environment. This event became the occasion that brought many people to the point of demanding a wider role in resource planning. Eventually these demands trickled through the levels of governmental process and began to have an impact on many federal agencies, including the U.S. Forest Service. In fact, the workload of the forest ranger today perceptibly reflects the impact made by the concept of public involvement.

Because of the environmental legislation of the 1960's, and because of the focus brought to these concerns by Earth Day, the Forest Service found itself no longer operating unobserved in the backwoods corners of the country. Policies and practices came under scrutiny like never before. The public was different now too—better educated, more scientifically oriented, and more politically sophisticated. As the events of the 1970's unfolded in this country, the American public began to demand not only greater government responsiveness, but also more accountability. At the same time, resources and energy were no longer the unspoken causes of politics and power gambits. The unrelenting attention now focused on resource use and development placed additional pressures on the federal government and its agencies, especially an agency charged with the management of so vast and valuable a resource as the National Forests.

|

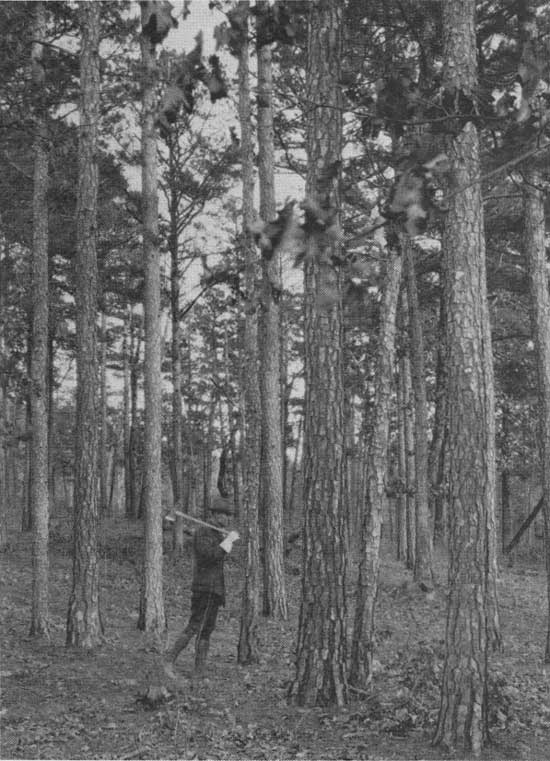

| Resource use in White Rock Ranger District. Man peeling pine posts. Photo No. 469347, by Dan Todd, 1951. |

Meanwhile the Ozark hills had begun to change visibly by Earth Day. An in-migration had begun, and Arkansas with her many isolated counties became the final outpost of the American frontier. People came to the state to enjoy retirement, to move back to the land, to get away from cities and traffic and pollution. Some people moved back home or to the home of their ancestors. They came in such numbers that a conference was held in Eureka Springs in 1976 to discuss the impact population growth would have on the state and region. [1] More people, more homes, more pressure on the state's and forest's resources.

Hundreds of acres of private woodland were converted to pastureland, altering the Ozark landscape. Even the steep slopes and hollows were put to pasture. Another smaller change altered the skyline of some Ozarks knobs and hills as the fire towers disappeared.

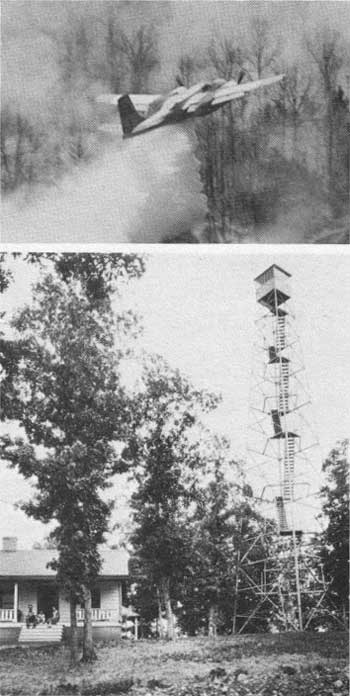

Until 1967 these fire towers had served as the first line of defense. [2] Fire wardens had recruited their own fire fighting crews, and in the early days the fight depended on these men and their hand tools. Beginning late in the 1950's, however, firefighting came to rely more on mechanized equipment. In the spring of 1964 an air tanker operation began at Fort Smith. Two aircraft—B-26's—were modified, each to carry a thousand gallons of fire retardant. These planes, and others that came later, served both National Forests in Arkansas. Aerial detection of fires in the Ozark National Forest began on December 1, 1970. Howard Graves, acting as observer and flying with a contracted pilot from Van Brooks Flying Service of Russellville, spotted the first fire from the air.

|

| Air tankers carry fire retardant to suppress forest fire. Other air planes serve as lookouts, replacing the forest tower lookout. No serial number. Photo No. 335394, by J.M. Wait, 1936. |

The people—newcomers and residenters—had changed too. Still part isolationist and part individualist—a great part—there had been some significant first efforts at group action and organization. When the Corps of Engineers in 1964 designed a dam to go on the Buffalo River, a grass-roots opposition formed to block any such construction. For the most part, this group supported a proposal to establish the Buffalo as a National River. The river rises in the mountains of the Ozark National Forest near Boxley, in Newton County, and runs 124 river miles through four counties before it joins the White River. [3] Some of the state's most spectacular scenery occurs along the alternating stretches of white and calm waters of the Buffalo River.

|

| View of Buffalo River on Highway 7 near Jasper. Photo No. 394633, by J.M. Wait, 1940. |

The group, the Ozark Society, organized in 1962 and pressed a six-year battle which left the river undammed. In 1968 Congress established the Buffalo National River. [4] More significant to this history, the Ozark Society did not close shop after achieving their immediate goal. The organization grew, extending into surrounding states, and served as a model, sometimes even a support group, for other environmentally concerned Arkansans. While the fight to save the Buffalo River did not involve the Ozark National Forest, the action stirred up many people who later became involved in issues more directly relating to the National Forest.

At this same time, nationally, forest practices seemed to be under fire. While the heat did not immediately affect the Ozark National Forest, the impact did appear later, in the mid-1970's. The controversy began over the forest practice of even-aged management—a practice adopted in the early 1960's, and a plan that provided for the growing of timber in stands of similar age and of similar general characteristics. Such trees were to be grown and managed together, from the time of planting (regeneration) to the time of final harvest. Such a silvicultural practice (whether in private or federal forestry) was considered by some to be more economical and efficient than managing timber stands of mixed age classifications and mixed species. Criticisms leveled by various interests groups, primarily the Sierra Club, focused mainly on the size of these stands. The problem presented itself awesomely when large areas were harvested and prepared for regeneration. One method used to implement even-aged management was clearcutting. While the debate and discussions occurred mostly in the far west and had less to do with the hills of Arkansas, the headlines did not go unnoticed in these parts. The size and scale of the timber stands left graphic, haunting impressions on many minds. Perhaps some of the newcomers to Arkansas brought these impressions with them.

Both these events—the organized effort to save the Buffalo River and the heat and fear stirred by the California clearcutting—had a significant impact on the degree and kind of public involvement the Forest Service began to witness in the Ozarks. Even as Earth Day was observed to a far greater degree outside the state of Arkansas, it took root and developed here as the years passed. Public involvement was becoming more than giving talks to school children. Public involvement was becoming more than an outlet for disgruntled citizens or a forum for special interest groups. Public involvement in the 1970's began to directly influence administrative planning at all levels—within the district, the forest, the region, and at national levels.

Admittedly the process has produced moments of conflict and discomfort. When the horseback riders asked one district ranger to ban motorcycles and jeeps from the forest, they created a frustrating situation. Hikers have, on their part, often complained about the horses, and have asked for their removal from forest trails and roads. To thicken the stew, the pro-wilderness contingent began pressing their case to have certain areas set aside and closed to any non-wilderness use. Meanwhile, nearby residents were all too ready to raise the roof at any proposed restriction of the land or the closure of any road. The hunters kept watchful lookout on the forest, considering it their private domain and sanctuary. As the wildlife populations became re-established in various parts of the National Forest, so did the number of hunters grow. At certain times of the year, the Ozark National Forest began to appear as a huge, well-armed camp. Increasingly, any forest practice or proposal affected larger segments of the public and often became the occasion to choose up sides.

One of the most heated periods occurred in 1965 when the Forest Service decided forest lands could no longer tolerate unrestricted grazing by livestock, especially hogs. Grazing permits had been issued in the forest since the early 1920's. Most livestock, however, grazed without permission. In 1965, more than 1,500 head of livestock, belonging to 79 permit holders, used the Ozark National Forest. In contrast, more than 8,000 head of cattle and 6,000 hogs grazed in trespass. A decision was reached to remove the hogs and limit the number of cattle then using forest lands to a number compatible with the carrying capacity of the land. Notice went out to local residents, and the following year, 1966, Forest Service personnel began trapping hogs grazing in trespass.

Both hog owners and cattlemen were angry. Tempers flared and so did the fires. The number of incendiary fires increased and it seems reasonable to assume some relationship between the two events. But it was more complicated. Neighbors also turned on one another, and fires set by one man or group were often blamed on another. Sometimes the Forest Service had prime suspects, but rarely did they have incontrovertible evidence. [5]

In the Boston Mountain Ranger District, one unfortunate fellow got caught between factions. The man was one who had given no trouble. He had always kept his own hogs fenced, and had carefully not sided with the Forest Service or with some of his aroused neighbors. In spite of his neutrality and his, own farming practices, his hogs happened to be the first trapped by the Forest Service. Some say he was set up and that his neighbors had torn down his fence to loose his hogs. He was outraged and somehow managed to get a Justice of the Peace to issue a personal summons for District Ranger Gene Jackson, citing Jackson for hog stealing. Although the case went through several courts, Jackson was never found guilty of the charge. [6]

Hog farming was a main source of income for many Ozarkers. Most people had no other jobs or source of in come. When the trespass hogs were trapped they were impounded and the owners could only get their animals back by claiming them and paying the costs incurred in the trapping, hauling, and feeding of the animals. Sometimes this cost amounted to more than the sale price of the animal. When owners would not or could not claim their hogs they were sold at auction.

Auctioneers did not much like handling such animals. It was not unusual for a man to put the word out warning off anyone who might be tempted to bid on his impounded hogs. In other instances people claimed animals not their own, taking advantage of an owner's reluctance to come forward and admit the impounded hogs were his in the first place. People were ill-tempered with one another and almost everyone was angry with the Forest Service. Little children thumbed their noses at the men whose job it was to trap the hogs. Many persons were ready to provide a sound cursing to Forest Service workers. Threats came by phone and by mail. Traps were tied down and sometimes shot-up—just to remind trappers of what could happen. One trapper, Ray Tackett, said it became impossible to get anyone to work with him, and that finally he gave it up and went about his job alone, even though Forest Service policy was to have a minimum of two men out in the woods trapping. [7]

There seemed no end to the threats and wild statements. One officer was warned that his truck tires would be shot out and then he too would be shot. An angered resident threatened darkly that a certain cove would "run red with government blood." Most of the passion was unleashed in such acrimonious statements: unpleasant to sustain, but not nearly as damaging as buckshot. Eventually the range came under control, and one of the most harrowing times receded into the dispassionate objectivity of history.

|

| The photographer J.M. Wait saw the many uses of wood products in many everyday activities. He captioned this photograph, "Daydreams of young America expressed in wood." Photo No. 238963, 1929. |

The hog removal program plumbed the residual depths of Ozark antipathy to government regulation of land. Friendly and seemingly law-abiding people became fierce in their opposition. Compared to the tradition of doing as they pleased with the land, the law-abiding nature of these people was just a veneer covering the mountain way of taking matters into one's own hands. This sort of public involvement, however, was just the sort the Forest Service had experienced in Arkansas ever since the earliest years.

Ten years later, in 1975, the people, now with a new environmental awareness managed to issue a different, but substantial, challenge to the administrative direction then being taken by the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests. The challenge issued by this new, educated, and politically smart citizenry brought about a sort of public involvement not common then to the Ozarks and which was to a large degree outside the experience of many foresters. This time the issue centered on the trees themselves, the core resource of the Nation Forests—the trees, how they were grown, harvested, regenerated, and just what sort of trees would be grown and harvested.

The trees of the Ozark National Forest can be grouped broadly by two types: the oak-hickory type and the shortleaf pine type. The oak-hickory forest dominates the upland regions, and develops best on the north and east facing slopes. This forest is made up of a variety of species which include the white, northern red, black, bur, and chinkapin oaks; the shagbark, mockernut, and bitternut hickories; sugar and red maples; American and slippery elms; white ash, black gum, basswood, hackberry, chinkapin, black walnut, black cherry, and beech. In the drier parts of this forest, usually the south and west slopes and along the ridgetops, another mixture of species appears: southern red oak, black oak, post oak, pin oak, and blackjack oak; along with hickory, maple, persimmon, and sassafras. The shortleaf pine is also found in this drier habitat. Pine is found, additionally, in areas that have formerly been farmed or disturbed in some way by man or nature. [8]

|

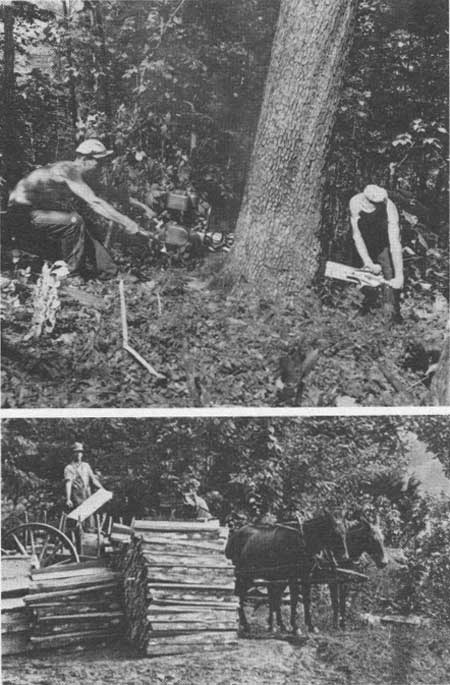

| Pine post yard of the H. C. Ormond Supply Company, near Clinton, Arkansas: Much of the raw material for these posts comes from pine thinnings in the Ozark National Forest. Photo No. 505690, Daniel O. Todd, 1963. |

Plans for managing the complicated mixture of a forest must take into consideration the demand for the timber resource—nationally and locally. At the same time this demand must be balanced against other forest resource needs. The demand for timber from the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests has varied during much of the period between 1961 and 1978. At first only a weak, sporadic market existed for pine pulpwood, and this was primarily confined to the Bayou and Magazine Ranger Districts. Frequently no one even bid for advertised sales of this forest product. In addition, those sales which did include pine pulpwood were often amended to grant more time in which to dispose of this product. Today, however, the demand for pine pulpwood is strong.

A limited market existed for hardwood poletimber, such as would be suitable for pulpwood or charcoal wood, and this is a situation which remains the same. Red and White oaks are the principal hardwood sawtimber species harvested in the forest. The demand for these and other hardwood species has increased steadily. The primary products coming from the forest today continue to be boards and railroad crossties. Recently, a demand for pallet material has provided a market for low-grade hardwood lumber. The white oak stave bolt market, once an important part of the forest's timber sales, had become drastically reduced in importance by 1967, when white oak barrels were no longer needed for the aging of whiskey. The demand for pine sawtimber, considered good in 1960, increased steadily and competition for sales of this product has become keen.

Bid prices for timber sales statistically bear out the market trends. Timber is sold by board feet. A board foot is a unit of measure. It indicates a quantity of lumber equal to the volume of one 12" x 12" x 1" board. A modest three-bedroom home would take approximately 11,000 board feet to build.

|

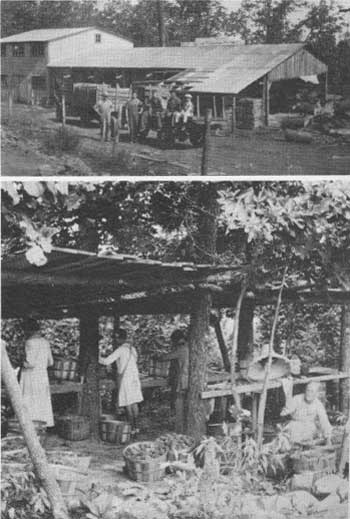

| This photograph is taken from an old postcard photo found in the Forest Service files and shows the Lurton Furniture Factory. The photographer and date are not known. Bottom: Scene near Dover, Arkansas. In the cultivation and marketing of Elberta peaches wood plays an important part. Photo No. 230830, by J.M. Wait, 1928. |

|

| Top: Marking Timber. Photo No. 527511. Photographer and date unknown. Middle: Felling white oak for bourbon staves. Bayou Ranger District. Photo No. 469355, by Daniel O. Todd, 1951. Bottom: Bolts for whiskey staves. White River at Sylamore. Photo No. 23608. Photographer, unknown. Date of photo is probably between 1911 and 1914. |

|

| Top: Sledding white oak stave bolts out to haul road. Bayou District. Photo No. 469358, by Daniel O. Todd, 1951. Bottom: A walnut tree loaded on motor truck and delivered on the railroad truck. Photo No. 238947, by J. M. Wait, 1929. |

The average price bid in 1963 for one thousand board feet of mixed red oak saw timber was $16.90; for white oak, $30 per thousand board feet; and, for pine sawtimber, $23.22. The average bid prices in 1977 came to $57.82 for mixed red oak, $58.37 for white oak, and $108.96 for pine sawtimber.

As the demand for timber products changes, so do the logging practices. As recently as 20 years ago practically all logging operations were carried out by mules, farm tractors, inefficient loading equipment, and trucks with load capacities of less than 2,000 board feet. Log lengths were normally less than l6 feet. Today, most logging operations use articulated skidders, better loading equipment, and trucks that haul up to 3,500 board feet. Pine timber is now logged tree length. Another change has been the phasing out of the peckerwood sawmills—the small portable mills that cut about 5,000 board feet a day. [9] Up until 1965 the peckerwood mill was common to the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests. Now, only a few remain in operation.

The increased mechanization of logging has required more careful administration of timber sales to adequately protect the watershed. Today's logging trucks require wider haul roads and these roads must be developed to higher standards. Articulated skidders can operate on steeper slopes and under wetter soil conditions, but when they do so there is more root damage and soil erosion.

In 1962 even-aged management began in the Magazine Ranger District, and by amending then current management plans in 1965, the rest of the Ozark National Forest was placed under this plan. The St. Francis National Forest amended its plan in 1968 when it was decided that the native hardwood species, most of which were intolerant of shade, would develop and reproduce best in even-aged stands, just as the southern pine did.

Timber stand improvement became concentrated on sites with designated high priority. A system of record keeping regulated regeneration to achieve a forest-wide balance of age classes, both in the pine and in the hardwood stands. At first, however, the size of regeneration areas was not restricted. Then, a 200-acre limit was applied in the late 1960's as an attempt to reduce the adverse effects caused by large regeneration areas. The size of these areas has been subsequently reduced. Current timber management plans limit regeneration areas to a size ranging from ten to seventy acres. [10]

Forest management in this country is still a relatively new practice. While forestry has been practiced for hundreds of years in Europe and Asia, the variations in climate and socio-economic factors make it impossible to manage the National Forests of the United States in the same manner. Recording forest practices is a relatively modern practice, and it takes generations to accumulate necessary data for management. In terms of trees, generations take a long time. Some of the trials and errors have become incorporated in the history of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests.

The current timber management plan reflects recent adjustments—the fine tuning of technology. One adjustment made under this plan is the implementation of a ten-year stand selection process. Regeneration stands, under this plan, are selected by an interdisciplinary team of foresters, wildlife biologists, landscape architects and other resource specialists. Stand selection takes into account the age, condition class, the need to break up over-sized stands, and the need to develop a dispersed pattern of age classes favorable for wildlife and other resources. Even the shape of the regeneration areas has been altered from the square or rectangle to irregularly shaped areas that blend into the landscape and that use natural features as boundaries as much as possible. [11]

Silvicultural practices in recent years have generated criticism and uneasiness. One practice in particular, the aerial spraying of an herbicide, landed in the courtroom.

Herbicides had been used particularly in areas selected for conversion (changing from one major type of timber to another). In the Ozark National Forest some areas stocked with low-quality and slow-growing hardwoods were converted to pine trees, which the site, as determined by the soil index, could better support, and for which there was a market. While this use of herbicides had some advantages—economics mostly—these areas created dramatically alarming scenes. Scenes of browned over acres of dying trees bothered local residents. Scenes of wild, jungle-thick vegetation during the first years when the full sunlight brought on a surge of new growth stimulated speculation about what exactly was going on in these areas.

But the main objection was not the unsightliness or even the issue of conversion. Objections were raised because of the nature of the herbicides themselves, especially the defoliant 2,4,5-T (2,4,5-Trichlorophenoxyacetic acid). The problem with this herbicide was a small but toxic impurity in the chemistry: 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenz-p-dioxin, sometimes called TCDD or simply dioxin.

The Ozark National Forest, complying with the Forest Service manual and with the National Environmental Policy Act, on April 18, 1975, filed a draft statement outlining the use of herbicides as a means of vegetation management. The statement served as a basis for public comment and described the herbicides 2,4,5-T, Silvex, and Picloram.

On June 9, 1975, a civil action suit was filed by the Newton County Wildlife Association. (This group was later joined by the Sierra Club who petitioned to intervene on behalf of the Newton County group.) The association sought a temporary restraining order and a preliminary injunction against the use of herbicides in the forest. A temporary restraining order was entered June 10, 1975, pending a hearing on the request for an injunction. A hearing was set for June 20. Following that hearing, the Forest Service was enjoined from the use of chemical herbicides until a legally sufficient environmental statement was filed. Following the period of public comment, which was extended until July 23, 1975, a final statement was prepared and filed on October 31, 1975.

The case remained in court awaiting a decision on the sufficiency of the environmental statement. Meanwhile all use of chemical herbicides stopped. Timber stand improvement was carried out by mechanical means or not at all. Before any ruling came from the court on the adequacy or inadequacy of the environmental statement, the Forest Service issued its timber management plan in September 1978. In this ten-year management plan the aerial use of herbicides was abandoned, as was the use of any herbicide containing the contaminant dioxin TCDD. This plan altered the situation to such degree that the case was dismissed by Judge Thomas Eisele on February 26, 1979.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap8.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |