|

For The Trees An Illustrated History of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests 1908-1978 |

|

Chapter 9

More Than Trees

The last twenty years of the forest's history may have been punctuated with periods of controversy and challenge and frustration—most of which has worked to strengthen and improve the forest and the relations of the National Forest with local residents. There was, however, one event in those years which generated both pride and excitement, and that was the development of Blanchard Springs Caverns.

Blanchard Springs has interested area spelunkers for years and local people and specialists had long known about Half-Mile Cave, as it has been called. The cave got this name because the natural entrance to the cave occurred one-half mile from Blanchard Springs. [1]

Forest Service recreation planner Willard Hadley had entered the cave in 1934 with the help of some Civilian Conservation Corps workers. The first recorded explorations of the Caverns, however, began late in 1955 by Roger Bottoms of West Helena, Arkansas. Bottoms was accompanied by Louis and Jimmy Grobmyer and by John Blake. [2] Over the next six years, this group explored the caverns many times, spending as long as 38 hours on a single visit. They were not the only visitors. By 1960 the cave had begun to show more and more the incriminating signs of human traffic—candy and gum wrappers, tin cans, used flash bulbs, and graffiti.

|

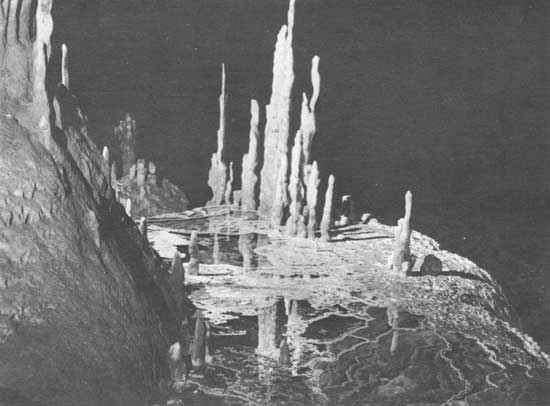

| Blanchard Springs Caverns. Photo No. 512984, by Robert E. Hintz, 1965. |

|

| Left: Blanchard Spring, Sylamore District. Scene on Falling Water Creek. Photo No. 356991, by J. M. Wait, 1937. |

|

| Above: Salamander pool with lace-like rock formations floating on top in Blanchard Springs Caverns. Photo No. 512983, by Robert E. Hintz, 1965. |

About this time, two spelunkers from Batesville, Arkansas, Hugh Shell and Hail Bryant, entered the caverns for the first time. They began the first of their many explorations. Shell and Bryant shared the knowledge they acquired in their 27 excursions into the caverns with the Forest Service, providing the Service with color slides, photographs, and maps. On February 11, 1963, Shell and Bryant took seven employees of the Forest Service into the caverns, including Alvis Owen, then the forest supervisor. [3] Later that year, on July 1, the cave was classified as a unique natural area and was set aside for recreational use. A Forest Service allocation of $5,000 in 1964 went for preliminary exploration and planning. The first appropriation for construction came in 1966, and since that time more than $12 million has gone into the development of the caverns and recreation area. [4]

To develop the caverns as a tourist attraction and to protect the living ecological system underground, the Forest Service determined it would be necessary to acquire some of the land around the caverns. Part of the peculiar quality of Blanchard Springs Caverns was that the cave, unlike some other large caves in the nation, was still living, and therefore vulnerable. In the end, the Forest Service acquired 48 tracts of land amounting to just over 1,771 acres. Part of this land came from willing sellers, but unhappily, some acquisitions came by means of condemnation proceedings.

What the Forest Service lacked in experience in underground construction, they made up for in enthusiasm over the project. When the caverns were dedicated on July 7, 1973, many Arkansans were on hand, having awaited eagerly this event. More than a million persons have marveled at the wonders of what in many ways seems to be an underground fantasyland, now accessible on two guided trails. (The second trail was completed and opened on July 7, 1977.)

Shortly after the Caverns opened, Mountain View, the nearby community, became an active center for native crafts and arts. It had long been known for its brand of music. The annual Mountain View Folk Festival began to draw unexpectedly large crowds. Many people came and camped on National Forest lands in the Sylamore Ranger District and at the Blanchard Springs Caverns recreation area. The large numbers, and in some instances the disruptive behavior of the participants, especially the use of drugs, made many county residents anxious. The numbers alone created problems for the limited commercial and recreational facilities. In the first years confrontations between those who attended the festival and the law enforcement community were commonplace, and sometimes hostile. Later, efforts were made to coordinate the event and to schedule the folk festival over consecutive weekends to reduce crowd levels to a more manageable size. [5] By 1976 the folk festival became an organized community endeavor and one with less adverse impact on the National Forest.

Blanchard Springs Caverns and its recreation area, is, however, only one of twenty-six such facilities in the Ozark St. Francis National Forests. Recreational use of the forest doubled in the years 1968 to 1974, and it is predicted that recreational use will quadruple by 1990. [6] Recreational areas are either developed sites or areas used for diverse activities with developed facilities. Another part of the recreational resource of the forest is its wilderness areas. Public Law 93-622 designated 10,542 acres as the Upper Buffalo Wilderness in January 1975. This area was one of sixteen areas in the eastern United States given wilderness status. The Upper Buffalo Wilderness Area generally included the headwaters of the Buffalo River, and it is joined on the north side by the Buffalo National River, a recreational resource administered by the National Park Service.

This same law, moreover, designated 17 other areas in the eastern United States as Wilderness Study Areas. One of these was the Richland Creek Study Area. Such areas were to be reviewed and examined to determine their suitability for wilderness designation. During the study period, the areas were to be managed to preserve the wilderness character and potential for inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. The Richland Creek Study Area is completely forested with scattered pockets of mature hardwood trees. Small clear streams bisect the area, while the rugged terrain is punctuated by steep bluffs.

|

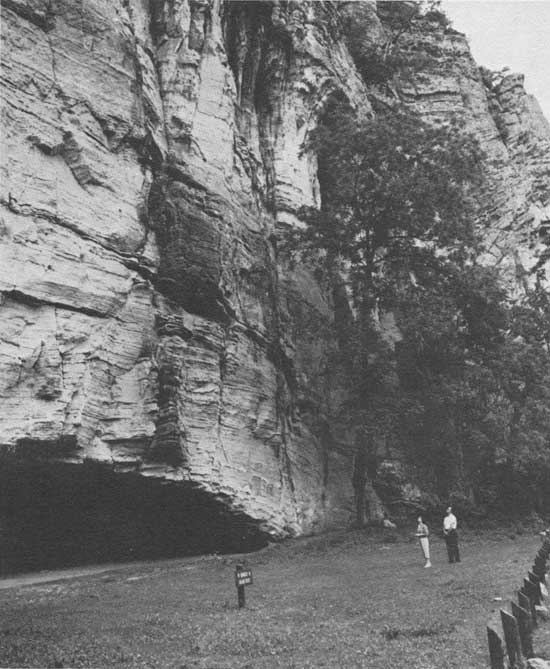

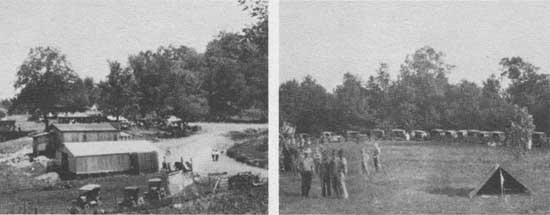

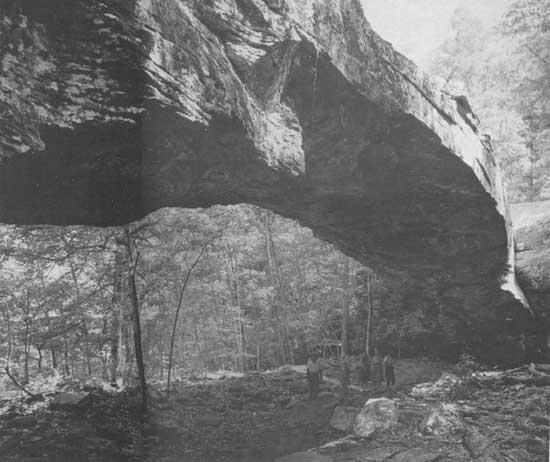

| Recreational use of the forest. The middle, left photo depicts a 1924 picnic gathering at Freeman Springs. Photo No. 196850, by J. M. Wait. The beginnings of a 4-H club campout appear to be under way, middle right photo. No. 230805, by J. M. Wait, 1928. Top, visitors at the Blanchard Springs Recreation Area limestone cliffs. Photo No. 505702, by Daniel O. Todd, 1963. Bottom: Other forest visitors examine the limestone arch in Alum Cove National Arch Recreation Area. Photo No. 504890, by Leland J. Prater, 1963. |

In the mid 1970's an inventory and review of roadless areas within the country's National Forests got underway. The purpose of the review (called RARE II—Roadless Area Review & Evaluation) was to recommend areas to Congress for inclusion in the wilderness system. The public was invited to nominate areas for evaluation and to participate in developing criteria and possible alternatives regarding the nominated areas. By 1978, the proposed areas within the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests numbered 13 and covered more than 125,000 acres. Following this nation-wide evaluation, the U.S. Forest Service submitted recommendations to the Secretary of Agriculture. The Forest Service recommendations for the Ozark National Forest included an addition of 1,504 acres to the Upper Buffalo Wilderness Area and the establishment of the Hurricane Creek Wilderness Area, covering 15,057 acres. The Forest Service also recommended an addition of 10,000 acres to the Richland Creek Study Area, an area with 2,100 acres already under examination.

The roadless area review generated its share of local reaction—both pro and con. As a result possibly of the recent land acquisitions through condemnation proceedings in the Blanchard Springs Caverns area and by the National Park Service along the Buffalo River, many people living in proposed wilderness areas felt uneasy, fearing the future status of their homes and land. Some of these people banded together opposing wilderness designation and appealed to their legislators. Others vented their anxiety by painting signs, such as the one on the back of a highway sign proclaiming, "RARE II Stinks." [7]

When Gifford Pinchot developed a public policy based on the notion that the water, wood, and forage of the National Forests would be conserved and used wisely for the homebuilder first of all, the concept probably seemed possible, straightforward, and simple. As the country grew, as the resources of the world became appreciably dearer in their diminishing quantities, the resources of the forests came under closer surveillance; the use of these resources had to be accounted for accurately, to all the people. And many people in the United States began to take a harder and longer look, especially at the bottom line.

The forest resources are significant—to the nation and to the counties in which National Forest land is situated. The National Forests contribute places for recreation; they feed and shelter large populations of wildlife, providing sport for some and food on the table for others. The National Forests protect watersheds and monitor streams to insure water quality for many communities. From the timber come jobs and raw materials that become digits in the country's gross national product. From the lands come other resources—shale, gravel, sand, minerals, oil and natural gas.

Minerals on public lands have remained a part of the public domain, and the Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 governs the leasing and extraction of oil and gas on public lands. Roy J. Anderson drilled the first well in the Ozark National Forest in 1954. It was dry. Between 1954 and 1970 eleven different companies drilled twenty-two wells. Only two produced. Many of these wells reported as dry were located in what is now the Batson field.

Drilling activity resumed in this area in 1973. One well, after treatment, produced four million cubic feet of gas daily, open flow. Encouraged, Arkansas Western Gas Company drilled another well just one mile north of the first. This well produced twenty million cubic feet daily. The company then began plans for a pipeline to serve the wells, and by September 1977, twenty-two wells were drilled on National Forest lands, with applications made for five more. Drilling activity has taken place in the Bayou, Buffalo, Pleasant Hill, Boston Mountain, and Magazine Ranger Districts, although more than ninety percent of the wells drilled since 1973 have been in the Pleasant Hill Ranger District.

Other mineral uses include permits for common variety minerals—surface rock, usually fieldstone for building material, and common shale, sand, and gravel for road surfacing. During 1977 the forest issued 105 common variety mineral materials permits. The Ozark-St. Francis National Forests rank second only to Mississippi in mineral collections in the Southern Region.

Each year a percentage of all National Forest collections—the receipts from timber, minerals, recreation, and grazing—is returned to counties in lieu of taxes. Each county receives its portion based on the number of National Forest acres inside the county. In 1906 this return was set at ten percent. The money was to be used for the benefit of public roads and schools. [8] Legislation changed this percentage two years later, on May 23, 1908, from ten to twenty-five percent of all moneys received during the fiscal year. [9]

Federal land ownership generates even more local heat when the issue is taxation. The question of taxation has been especially vexing for forestry. Should National Forest lands be taxed? Should they be taxed at the same rate as private lands? In the case of forestry, when the product is harvested so rarely and when the resource serves a national need, should there be other arrangements? Section 3 of the Clarke-McNary Act of 1924 authorized the first study of tax laws, methods, and practices with regard to their effect on forest perpetuation. This Act further authorized a cooperative effort to devise tax laws designed to encourage the conservation and growing of timber. This legislation and the resultant study contributed significantly to the resolution of tax problems in forestry, both private and federal forestry. [10]

The Ozark-St. Francis National Forests reach into 18 Arkansas counties. In some of these counties the high percentage of federal land ownership affects the county tax base. As Ozark land values have increased in the last ten years, and as the budgetary pressures and demands on local government have increased, county residents became concerned about the federal return in lieu of taxes. Until 1976, the twenty-five percent return to the counties had been calculated on the basis of revenues received, less the expenses incurred—as, for example, the construction of a road necessary to haul timber from the sale site. Costs for timber stand improvement and for timber planting were also subtracted before figuring the county return. This system, based as it was on percentage returns, is subject to market fluctuations and conceivably results in periodic inequities felt keenly by local governments. To alleviate such situations, Public Law 94-565, the Payment In Lieu of Taxes Act, passed October 20, 1976, guaranteed a minimum payment of seventy-five cents per acre to counties in which public lands are situated. This minimum payment guarantee is administered by the Bureau of Land Management in the Department of Interior rather than by the U.S. Forest Service. The way the guarantee works is that when the 25 percent return from forest receipts does not equal the minimum guarantee, the difference is made up in a separate check that goes to the state. Further more the National Forest Management Act of October 22, 1976 changed the formula from which payments were made to the states. Beginning in 1977, the returns were computed on the basis of gross National Forest receipts. The return in lieu of taxes payment does not go directly to the county, but goes to the state. The state legislature prescribes the allocation or formula by which the funds are used for public schools and for roads. In Arkansas, 80 percent of the county return goes to the schools and 20 percent is used for roads.

|

| A mountain school. Photographer unknown. Date, between 1912 and 1914. Photo No. 15525A. |

In addition to these returns to the state and counties, a 50 percent return is made on moneys received from mineral resources on public domain lands. The return from these receipts is managed also by the Bureau of Land Management and is for such uses as the state legislature may direct.

There are indirect benefits accruing to county residents and federal land users as well. Forest roads and trails provide access to public lands while also serving the transportation needs of residents living within the forest boundaries. Each year ten percent of the National Forest receipts is plowed back into road construction and maintenance appropriations. Moreover, some roads constructed during timber sales become a permanent part of the National Forest road system, again serving county residents and forest users.

The Federal Aid Highway Act of 1958 provided funds to states for highway construction and maintenance. Arkansas has received $430,000 a year recently from this fund. While the fund is administered by the Federal Highway Administration, decisions about the allocations in Arkansas are determined by a tripartite group: The Arkansas Highway and Transportation Department, the Federal Highway Administration, and the U.S. Forest Service. Most recently, the work on Highway 309, at Mount Magazine, was completed with these funds.

Another indirect benefit of Arkansas's National Forests comes from their contribution to the wood products industry, one of the state's biggest businesses. The forest products industry employs more than 49,000 Arkansans. [11] The demand for timber, as for other forest resources, is expected to increase. The Ozark National Forest is not now a large timber producer, primarily because markets do not yet exist for small poletimber and for the tree tops. Continued pressure on the nation's forest produce, however, may alter this situation. Nationally, the major thrust in forest management will be to employ methods and approaches that will get more out of the available resource. The goals and procedures for this sort of management have been outlined in the National Forest Management Act of 1976. The job of the forest ranger will continue to be one of juggling the multiple resources to insure long term yields for both local and national needs. The perspective of the forest ranger seems substantially more complicated than that faced by those first rangers surveying the forest from the vantage of the saddle.

|

| School children. Photo No. 85954, by Francis Kiefer, 1910. |

|

| Cass school. White Rock District. Photo No. 195338, by J. A. Mason, 1925. |

|

| Bidville School. White Rock District. Photo No. 195337. Probably by J. A. Mason, about 1925. |

|

| School children from Dover, Arkansas. Photo No. 242654, by J. M. Wait, 1930. |

Still, it's people who keep a forest productive; who protect it. The first foresters and the first rangers in the Ozarks, like their federal counterparts, were pioneers in forestry and many of them could have been described as both hard-headed pragmatists and crusading idealists. To a man, they were convinced sound management of the nation's forests would pay for itself and would insure forests for the future. Those pioneers worked, almost with a passion. The pay was poor. The eight-hour day had not yet been invented. Many foresters throughout the past seventy years in the Ozarks worked six and seven days a week, sometimes 12 and 16 hours a day. Most often they filed no claims for overtime, It was part of the work to be done. Carl Benson, former timber staff officer and forest ranger, filed a report in 1964 which stated, "Overtime? None claimed—it was all contributed for the good of the Forest Service." [12]

The Ozark-St. Francis National Forests have had many men like Benson—Francis Kiefer, Ben Vaughan, H.R. Koen, Jim Wait, Daniel Todd, Ralph Hunter, Dexter Curtis, Fred Emory, Von Ward, Dixie Carter. There were men like Ranger William Dale, who, to his men, seemed capable of performing both great and small miracles. So many men and women—the wives of rangers and forest workers have probably been grievously overlooked as to their considerable contributions here in the Ozarks—who believed in the Forest Service and gave of themselves generously. From the earliest days, the Forest Service was an outfit with a cause. This cause was the driving force that Pinchot described as permeating the fabric of the organization and that gave the Service its pride; that manifested itself as a belief in one's work and in the end accounted for the dedication and high morale of its men and women. [13] Personalities may have rubbed wrong from time to time; friction and factions developed. Yet, over the years, the sense of purpose and the sense of serving remained.

|

| Foresters in the field. Photo No. 92182. Photographer and date unknown. |

Of course there have been changes. The demands on the forest resources were not the only changes taking place. The Forest Service itself, like any organism, had been changing as well. Partially the changes came about because of the concept of multiple use, and partially because of the mandates laid down by the environmental legislation, and because resource management had simply become too critical and too complicated. As more was learned about ecological systems and the ways in which they inter related, the knowledge was put to use. The Forest Service soon became more than a group of timber experts.

The first soil scientist came to work in the Ozark National Forest in 1961. Before that time the forest relied on the Soil Conservation Service and other soil scientists. Information compiled by these specialists is used in land management planning and in most project planning and design. Soil surveys have now been completed on 80 percent of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests.

Likewise, before 1963 the forest had no fulltime hydrologist to manage the water and watersheds of the forest. Hydrologists analyze watersheds and inventory restoration needs of eroded areas. They also provide treatment for such places. The Watershed Protection and Flood Prevention Act of 1954 authorized the Department of Agriculture and consequently the Forest Service to co-operate with states, counties, and local public agencies to prevent watershed damage and to further the conservation, development, use, and disposal of water. One of the pilot projects carried out under this legislation was the work done on the Six-Mile Creek Watershed in Logan and Franklin counties. This project provided flood prevention, municipal water, and recreational opportunities for the community of Charleston, Arkansas. Similar projects have since been accomplished. Additionally, the forest hydrologists have completed or are in the process of completing river basin studies for the forest.

Other specialists now an integral part of the Forest Service include wildlife biologists who work with the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission to develop, maintain, and manage the wildlife resources. More than 700,000 acres of the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests are designated as wildlife management areas. Recreation specialists, engineers, landscape architects, archaeologists, even writers and photographers, fill the roster of today's Forest Service. Resource management and public involvement have placed new demands on the whole forest, and on every Forest Service worker.

The organization also changed because of a number of federal manpower programs. One especially has had a considerable impact on the Forest Service and on the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests. This particular program was the Job Corps. But first, to begin at the beginning.

The first manpower program in the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests was called the Accelerated Public Works program. It began in November 1962 and averaged 161 employees on its payroll. This program and other manpower programs served the forest in much the same way as had the Civilian Conservation Corps back in the 1930's. The manpower programs provided money and people to accomplish many tasks that the Forest Service alone could not perform. The Accelerated Public Works program built new work centers at Cass, Clarksville, Mountainburg, and in the St. Francis National Forest. They also constructed offices for three ranger districts and worked on forest recreation areas before the program ended in 1964.

|

| Water cooling basin at city power plant, Paris, Arkansas. This water is from the watershed in the Ozark National Forest. Photo No. 381543, by Daniel O. Todd, 1956. |

The next year, the Job Corps Center opened at Cass, Arkansas, on the site of the former Cass Civilian Conservation Corps camp. Job Corps is an intensive program of education, vocational training, work experience, and counseling. The purpose is to provide disadvantaged youth an opportunity to become responsible, employable, and productive citizens. Corpsmen came to Cass from many towns and cities of the region and nation. They live in dormitories, which, in some cases, have been constructed by the corpsmen themselves. By 1978, almost 5,000 young men had been enrolled at the Cass Job Corps Center.

The center is staffed primarily by Forest Service personnel. In fact, the only staff not part of the Forest Service are the teachers in trade union training programs—carpentry, heavy equipment operation, painting, and brick and stone work. The Forest Service, in agreement with the U.S. Department of Labor, operates 18 of the approximately 100 Job Corps centers in the country.

When the Forest Service began hiring people to staff these centers, they began hiring people with educational backgrounds and experiences different from those of the traditional forest ranger and forest technician. The Forest Service began hiring teachers, guidance counselors, and management specialists. Later, the President, Richard Nixon, cut Job Corps funding and many centers closed. Rather than discharging so many people, the Forest Service absorbed many Job Corps personnel and began developing career possibilities for them within the Service. This action in one manner broadened the Service, bringing in new men and women with different talents and areas of specialization. The legacy of the Job Corps has been not only one of significant work accomplishments and service to the young and often disadvantaged, but also one which altered the personnel profile of the Forest Service as a whole.

A forest needs people to protect it, to manage it, to appreciate it. A forest needs people to walk its trails, to fish its streams, to stop and admire the dogwood and hickory, the oak and the pine.

The decisions that have to be made today and in the future will require a broadened perspective and an interdisciplinary approach. The decisions will also require an informed and educated public. As the pressure on resources increases, the trade-offs will become more critical, less clean-cut, more difficult, possibly, to accept.

|

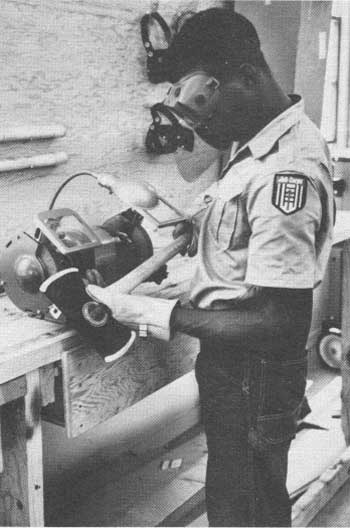

| Corpsman from Dendron, Virginia, sharpening axe at the Cass Job Corps Conservation Center. Photo No. 512578, by Robert E. Hintz, 1965. |

|

| Top: Scene in Mountain View, Arkansas, about the time the first automobile made an appearance in that town. Photo No. 230807, by J. M. Wait, 1914. Bottom: The first attempt to use tractors in road construction in the Ozark region. Photo No. 230773, by J. M. Wait, 1928. |

The noticeable changes in the Ozark-St. Francis National Forests can be seen in the people and in the Forest Service itself. Yet, even these changes retain so much tradition, the roots of their history. There is still within the Forest Service evidence of the idealism and dedication brought to that organization by Gifford Pinchot. And there is still within the Ozarks ineradicable strains of the mountain character—self-sufficient, suspicious of government, conservative by nature, and bound almost chemically, like molecules, to the land.

The changes in the woods have, in general, been subtle ones. To describe the forest today would not result in a radically different description than those made in 1908. The trees, for the most part, look the same. Indeed, many of them are—the same trees that shaded the ranger as he rode through his district on horseback; the same trees protected by the men of the Civilian Conservation Corps; the same trees cherished and delighted in each spring and fall by the tourists who gather at the ranger station in Jasper.

For the trees, change comes slowly, and history runs deep.

|

| Virgin stand of hardwoods near Sandy Flats Firebreak. Taken by B. W. Muir — 1938. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

8/ozark-st-francis/history/chap9.htm Last Updated: 01-Dec-2008 |