|

The Land We Cared For... A History of the Forest Service's Eastern Region |

|

CHAPTER V

THE LAKE STATES REGION, THE FIRST REGION NINE

Establishment

The history of Region 9 begins in 1928 when the Forester's office in Washington, having studied the forestry situation in the three Lake States of Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota, concluded that a new Region needed to be established there. The Forest Service planned to expend $6 million over the next 10 years in the Lake States. In the words of Assistant Forester Leon F. Kneipp, "careful coordination and constructive cooperation" was needed between the Forest Service, the lumber industry, and the three state governments. Michigan already had a state forestry program, Wisconsin was in the early stages of forming one and Minnesota had only begun planning. [1]

Recognizing the magnitude of the job ahead, the new type of work with state governments, and the need for a permanent Forest Service presence in the area, the Assistant Forester came to the conclusion that there needed to be a separate Region for the Lake States. He envisioned that there would be no great increase in overhead, only the salaries of a Regional Forester, an assistant, an executive assistant, and two or three well-qualified clerks. Kneipp noted that many people in the Lake States area were incredulous when they learned that the Forest Service administered the area from an office in Denver, Colorado. Having a Regional Office in one of the Lake States would remove this feeling of being under an "alien administration." [2]

Forester Robert Y. Stuart was in accord with the recommendations of his Assistant. On December 20, 1929, he wrote to his superior, the Secretary of Agriculture, justifying the decision to create a new Forest Service Region in the Lake States. "One of the outstanding problems of the forest economy of the nation," he wrote, "is presented by the Lake States of Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin, where acute need exists for the reclamation of large areas admirably adapted to timber production but at present denuded and unproductive of either economic resources or taxes." The Forester assured the Secretary that the situation was one where the "active participation by the federal government" was justified and desired by the state governments.

Forester Stuart explained that the National Forest Reservation Commission had already approved a program for the acquisition of 2.5 million acres of land for the establishment of nine purchase areas in the proposed District 9. In answer to the potential argument that no new Region was needed because the Lake States were currently a part of District 2, the Forester stated that this arrangement would not "adequately meet the new administrative requirements" of the already approved acquisition program because Denver was remote from the acquisition activities. The distance involved made it impossible for the Denver Office to devote the attention needed to the problems of the Lake States. Striking a political note, Stuart spoke of the resentment caused in the Lake States by the Forest Service trying to administer their area from an office which lacked contact and familiarity with local conditions and needs.

To remedy the situation in the Lake States, Forester Stuart proposed to create a new District in the Lake States. He admitted the new District would be small compared to others of the Forest Service, but it would contain 10 important forest units embracing a total of 1.2 million acres of government land, which compared favorably to the size of District 7 when it was created. Also included were the additional 2.5 million acres which had already been approved.

One distinctive feature about the Lake States area made "careful leadership and supervision indispensable"—the vast acreage of privately owned forest. For the general development of the regional economy to continue, the Forester believed that the Forest Service must take a large role in promoting state and private forestry. The proposed program alone would mean the expenditure of more than $6 million in the Lake States. That kind of spending, while it would certainly benefit the local economies, needed to be carefully monitored to guard against irregularities and assure that the greatest possible benefit was obtained.

Since the states of the Lake States area already had forestry programs, close cooperation with the appropriate state agencies and coordination with their plans and programs would be essential. Stuart cited this as another reason why a new District Office was needed in Milwaukee. "It might never be necessary," said Stuart, "to build up in the Lake States an organization so large as the first six Districts." The range of Forest Service activity in the new Region would be "narrower," and some of the positions might be consolidated as they had been in Districts 7 and 8 (the new Southern District). The Forester assuaged any fears the Secretary might have had about additional costs to the government from creating a new District by saying that these would not be great. All that would be involved was the salary of the District Forester and his assistants, their travel, and some clerical help. Even these small expenses would be partially offset by the savings generated by not having to send people from Denver to do the work. [3]

The man chosen to be District Regional Forester for the newly created District 9, Earl W. "Ted" Tinker, had been working for the past several years out of the Denver Office supervising land acquisition in the Lake States. He had been instrumental in developing the program by which acquisitions of the 2.5 million acres had recently been approved by the National Forest Reservation Commission. In the opinion of Forester Stuart, Tinker was "probably more familiar with the Lake States situation than any other member of the Forest Service." Tinker was a native of Michigan, a graduate of the Michigan State College School of Forestry, and had done graduate work at the Yale School of Forestry. After a long stint of forestry work for the Canadian Pacific Railroad, he had joined the Forest Service, serving first as a technical assistant and later as Supervisor of two important National Forests. In the Washington Office, he had been an Inspector and Assistant Chief of the Office of Forest Management. In the Denver Office, he had been Assistant District Forester in charge of the Office of Lands. The Forester was well pleased with Tinker's work, saying it had been "uniformly excellent, particularly in connection with the forestry program in the Lake States." [4] (See Appendix for complete list of Region 9 Regional Foresters.)

Setting Up the New District

The Secretary approved the creation of the new District (Region), and on December 22, 1928, Stuart wired the Regional Forester at Denver as follows: "Lake States Region has been established. Proceed to Madison, Wisconsin, and establish temporary office." [5]

The job of selecting the location for the permanent headquarters of the new Region fell to Earl Tinker, the new Regional Forester. Regional headquarters were usually placed in large cities in the Region. Tinker chose Milwaukee. In Washington, Forester Stuart approved Tinker's choice and also his plans to open the office with a very small staff and to handle the work of the office without creating a formal organization by branches. As soon as the Secretary of Agriculture released acquisition money, it was understood that Tinker was to submit definite recommendations for filling the positions which had already been approved. [6]

When Region 9 was established, it consisted of only three National Forests: the Michigan National Forest and two in Minnesota. Newly appointed Regional Forester Earl W. Tinker stopped in the Lake States Region en route to Washington to meet with the three Supervisors and hear their views on his plans for the Regional staff. He proposed that the staff at the Regional Office consist only of himself, a Deputy Forester, and a Fiscal Agent. All the other staff in timber management, lands, and other resources, would be placed on the Forests, "where the work was." Naturally, the three Supervisors endorsed the plan. But when Tinker learned in Washington that funding for the Region would depend on the amount needed by the District Office, he withdrew his idea. [7]

The new Lake States Region was to oversee the National Forest lands in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota as follows: the Flambeau Purchase Unit, the Moquah Purchase Unit, and the Oneida Purchase Unit in Wisconsin (a total of 409,000 acres gross [within boundaries] and net or actual holdings unknown); the Chippewa National Forest, the Superior National Forest and Purchase Unit, and the St. Croix Purchase Unit (abandoned in 1930) in Minnesota (a total of 2,150,200 gross and 1,034,800 net acres); and the Huron National Forest and Purchase Unit, the Keweenaw Purchase Unit, the Mackinac Purchase Unit, and the Marquette National Forest and Purchase Unit in Michigan (a total of 1,290,300 gross and 388,500 net acres). The grand totals were 3,849,500 gross and 1,423,300 net acres. [8]

These holdings would not seem to warrant the creation of a new Region, but Forester Stuart was looking ahead. The Clarke-McNary Act had passed in 1924, and purchases of timber lands authorized by it had begun. Earlier in 1928, the National Forest Reservation Commission had approved a program recommended by the Forest Service whereby approximately 1.1 million acres would come under federal ownership in Michigan and Minnesota, and a number of other purchases would be made in the Lake States. The declared purpose of these land purchases was to aid in timber production and demonstrate forestry practices. [9]

On January 1, 1929, temporary headquarters for Region 9 were established with the Forest Products Laboratory at Madison, Wisconsin. Meanwhile, Tinker looked for a suitable building in Milwaukee. The best he could find was the former rye whiskey testing laboratory in the Post Office Building. In March the tiny staff occupied its new quarters, equipped with hand-me-down furniture and a few battered file cabinets. [10] In 1932, the offices moved to the Post Office Building at 517 East Wisconsin Avenue in downtown Milwaukee. At that time, the entire staff, consisted of 19 people. One employee commented that the new office space was "what a real Forest Service office looks like—or should look like." [11] In 1935, after the Region assumed supervision over 15 million new acres and had been given responsibilities for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in the Region, the offices were moved to the Plankinton Arcade Building at 161 West Wisconsin Avenue. (See Appendix for list of Region 9 Regional Office locations.)

The organization of the Regional Office was in Divisions, each headed by an Assistant Regional Forester. In 1962, the divisions were: Engineering, Fiscal Control, Information and Education, Personnel, Operations and Fire Control, Recreation, Wildlife and Range Management, Lands, Minerals, and Water, State and Private Forestry, Timber Management, and Emergency Conservation Works (the CCC from 1933 to 1943). In 1930, the states of North Dakota, Iowa, Indiana, Illinois, Ohio, and Missouri were added to Region 9, all but North Dakota being transferred from Region 7. [12]

From the beginning, the Lake States Regional Office had been a sparse affair. By 1930, there were only 13 members of the staff, very few compared to other Regions. Regional Forester Earl Tinker was ready to say that perhaps the austerity had been "overdone." Tinker suggested this in a report to the Forester, but little note was taken. Nevertheless, the staff began to grow and the Regional Office had 166 employees by 1940.

The total number of permanent employees in the Region increased from 138 in 1928 to 207 in 1931. Some technical foresters had been added, a few clerks, and several District Rangers, but there was one less Supervisor. The Region had only three types of specialists: lecturers (a term no longer used), acquisition specialists, and surveyors. This indicates how much simpler the job of the Forest Service was in those days. [13]

After Earl W. Tinker, who served until 1936, the Regional Foresters were Lyle F. Watts (1936-1939), a forestry trained graduate of Iowa State College, formerly Director of the Northern Rocky Mountain Forest Experiment Station at Missoula, Montana and Jay H. Price (1939-1954), a forestry graduate of the University of California, whose previous position was Associate Regional Forester for Region 5. [14]

Throughout the 1930's, a major factor in communicating and bringing all of the different elements of Region 9 together was the Daily Contact, a daily and later biweekly newsletter published by the Regional Office in Milwaukee and distributed to all other offices. The purpose of the Daily Contact was not only to provide information and education but to give a feeling of unity to Region 9. [15]

Early History of Region 9

New Units

During the 1930's, Region 9 decided to complete plans for purchase units in the Lake States under an authorization from the Forester to purchase 2.5 million acres under the Clarke-McNary Act. After a reconnaissance, the Regional Forester and his staff developed a new purchase area of approximately 171,000 acres in Minnesota, to be called the Mesaba. The consent of local people was obtained by means of letters and petitions. The State Forester offered no objections. The unit was sent to the Forester in Washington for approval, and placed before the National Forest Reservation Commission, which authorized the purchase work to begin.

In Wisconsin, the planning was for a 1,674,450 acre purchase (the Oneida) in the northern part of the state. These two units put the Region over its 2.5 million limit by more than 250,000 acres. Meanwhile, the Region arranged land exchanges with the State of Michigan which would absorb all remaining public lands in that state. In such exchanges, the public lands were exchanged for state owned lands already within the boundaries of National Forests. [16]

Timber Management

By 1930 there were a few timber sales on the National Forests of the Lake States. Sales on the Superior Forest were approaching $100,000 per year. The principal task on the Huron Forest was timber cruising. There was a modest replanting program throughout the Region. The plants came from two nurseries at Cass Lake and Beal, Minnesota. The two nurseries were capable of producing 10 million tree seedlings per year. The Region had also made arrangements with the State of Wisconsin for the donation of a nursery site by Oneida County. The Kiwanis Clubs of Wisconsin had raised $10,000 for the construction of this site. [17]

Fire Protection

Throughout Region 9, some 60 miles of firelines were built in 1930 to protect new forest plantations. Most of the work was done by Forest Service personnel. Fire protection began on five new forest units that year. The new equipment included six fire trucks, 15 tool caches, and one power pump. The fire season that year was the most severe in many years. The new units, because their fire fighting teams were not yet well organized and trained, suffered heavy losses in timber and personal injuries. In the Region there were 49 Class A fires (less than 1/4 acre), 41 Class B (1/4 to 9.9 acres), and 42 Class C (10 to 99.99 acres), for a total of 132 fires; of these, 111 were man-caused and 21 were due to lightning. Hydroplanes were used for the first time for patrol purposes in the Region with positive results. Smoke and haze so obscured the vision from lookout towers that aircraft were an essential improvement. [18]

Public Relations Work

In the early years of Region 9, the big job in public relations for the Regional Office was establishing closer relations with state conservation agencies. The job of dealing directly with the public was left largely to the National Forests and Purchase Units. The Regional Office did have close contacts with such organizations as the Izaak Walton League, the Arrowhead Association, the Minnesota Federation of Women's Clubs, and the Kiwanis. The Regional Office also strove to interest the various Congressional delegations in the work of the Forest Service and in conservation. Six states had been added to the Region in 1930—North Dakota, Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Iowa, but little had been done to begin public relations work in those states because there were no Purchase Units there. [19]

Demonstration Forests

Forester William B. Greeley, (called Colonel Greeley) had much to do with determining the course taken in the Lake States Region. In a speech to the American Forestry Association, Greeley laid out his plans. There would be much Forest Service acquisition of cut-over forest lands which would be organized into large National Forests. The ultimate purpose was to restore the great pineries of the North Woods Country by good forestry and management.

By 1931 the large production forests had given way to a system of smaller forests to be used as demonstrations of good forestry practices. The idea was that private forestry and the profit motive rather than the Forest Service would be used to restore the great pineries. The demonstration forest concept had been heartily accepted in Region 7. The idea was generally attributed to Associate Forester Kneipp, although he once scribbled "credit not mine" on a letter that crossed his desk.

Region 9 Regional Forester Earl W. Tinker had doubts about the workability of demonstration forests. He was convinced it would never work in the Lower Peninsula of Michigan and Minnesota. He had come to believe that the system could work in the commercially profitable forests of Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan if given special attention and funding. In fact, he predicted that by 1935 there would be 2 million acres of privately owned land in Wisconsin producing timber crops. Tinker had even adjusted to the idea of having smaller forest units. He was convinced that timber interests would want to retain or even acquire new timber lands within National Forest boundaries because there would probably be a revival of the timber industry in the area.

One large drawback existed in the demonstration program—it meant the end of the plans for great National Forests in the Lake States Region. If Colonel Greeley's plan for the Lake States had been carried out, as many as 10 million acres of land might have been acquired. However, with the new emphasis on demonstration forests, Forest Service land acquisitions had been reduced drastically.

Tinker was clearly upset by this turn of events. He blamed it on the demonstration forest concept, but it was so widely accepted in high places in the Forest Service, he did not dare oppose it. Instead, on Christmas Eve, 1930, he wrote a long letter to Forester Robert Y. Stuart pointing out the serious complications Region 9 was having with the demonstration program. Demonstration forests required "especially intensive administration, protection, and development." There could be no more than two purchase units under each Supervisor, Ranger Districts would be no larger than 100,000 acres, planting programs would need to be much smaller, fire protection would have to be upgraded, and, in general, management costs per acre would be much higher than on a production type forest.

Tinker and his staff had developed a five-year plan to implement the demonstration forest concept. Tinker called for new policies and plans for the administration of units where it had been decided that demonstration was the primary objective. He asked the Chief Forester to recognize that Region 9 had special financial needs if it was to reach the desired objectives. He wrote, "This is, frankly, a plea for special consideration, based upon the plans for Region 9 as we conceive them." [20]

Tinker's letter caused quite a stir in the Washington Office. The most violent reaction came from Ed A. Sherman, Associate Forester and head of the Branch of Lands. Sherman suggested to Forester Stuart that Tinker needed to be "straightened out." The original plan, according to Sherman, had been to use the Clarke-McNary Act to purchase about 5 million acres of land for forest production in both the Lake States and Southern Regions, with the acreage equally divided between the two. That was what had been approved by the National Forest Reservation Commission. Sherman admitted that the figure of 2.5 million acres for each area was not necessarily final. He was confident that the public would eventually want more purchases. Anyone who attempted to commit the Forest Service to more than that was a "dreamer."

As for the issues Tinker had raised concerning demonstration forests, Sherman declared that demonstration was nothing new in the Forest Service. From the beginning the forests acquired under the Weeks Act had been demonstration forests. They required no different management, protection, or development from production forests. Sherman denied the validity of Tinker's suggestion that the forests of the Lake States were so different that they required the development of new procedures in demonstration work. He contested there were forests elsewhere which were similar. [21]

The whole matter raised by Tinker landed finally on Chief Stuart's desk. He wrote to Tinker that the change in plans regarding the Lake States from a system of large National Forests built up over extensive cut-over areas to a system of "smaller areas well distributed by types" had been necessary because Congress had placed acreage limitations on large-block land purchases in the East. Congress was reluctant to take whole counties or large parts of them off the tax rolls, and they refrained from placing obstacles in the way of states assuming responsibilities in forest land acquisition and administration.

Stuart recognized the significance of the Lake States National Forests as presenting an outstanding opportunity to demonstrate sound forest practices. But this did not mean that they should be given special management and more financial support. In his 1931 memo he stated, ". . . our National Forests are not to be thought of either as experimental forests where costs are subordinate to fundamental research, nor as examples of forest demonstrations which can not be practically followed by forest land owners because of cost consideration."

Stuart advised Tinker to administer the National Forests of the Lake States with no greater emphasis on demonstration work than would be made anywhere else. He was pleased with the progress being made in the Lake States—"You are getting at the fundamentals of the job splendidly and upon this base we shall build"—but he could not promise any special treatment for the Lake States District. [22]

The National Forests of Region 9

The original Region 9 National Forests were the Minnesota (Chippewa), Michigan and Marquette (Hiawatha), Superior and Huron. (See Appendix for Chronology of Establishment of Eastern National Forests.) A short history of each follows:

Minnesota (Chippewa) National Forest

The Chippewa National Forest, originally called the Minnesota National Forest, has the distinction of being the first Forest in Region 9, although at the time of its formation (1908), it was part of Region 1 with headquarters in Missoula, Montana.

The land on the headwaters of the Mississippi which now comprises the Chippewa National Forest was once the homeland of the Ojibwa Indians. For centuries the Ojibwa had lived along the Great Lakes, hunting, trapping, fishing, gathering wild rice, and making maple sugar. The Ojibwa were one of many tribes of the Algonquian language family. They lived in scattered groups in an immense area around the Great Lakes and northwest into Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, Canada. During the 17th century they developed a growing fur trade with the French. This trade required more intensified fur trapping and a broader hunting ground. Consequently, conflict ensued with the Iroquois, Sioux, and even with other Algonquian tribes of surrounding areas. [23]

The Ojibwa were caught in the middle of the European struggle for control of North America from 1754 until 1783 when a peace settlement was finally signed between England and the United States. The treaty divided the Ojibwa land between the two nations. England retained actual control of the Great Lakes region for another 30 years. In 1825 the United States government called a meeting of all upper Mississippi tribes at Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin. At this meeting the upper boundary of Ojibwa land was fixed. In the succeeding decades treaty upon treaty was proposed and then broken by the United States government. Finally, a "removal" policy was adopted in 1830 directing all Indian peoples to relocate west of the Mississippi River. In the 1850's a reservation policy began which concentrated the Ojibwa on land set aside for them in Minnesota. Promises were made to treat these peoples as citizens of autonomous nations. Nevertheless, by 1871 the practice of making agreements with Indian tribes or bands as though they were independent foreign nations was abandoned. [24]

In the face of the American 19th century forms of progress—lumbering, farming, and railroad—the United States government found it to be too much trouble to bother with separate Indian nations. The urgency of "white" manifest destiny pervaded the thinking of the frontiersmen and their government officials. Non-Indians became angry when they saw "undeveloped" Indian land.

The new philosophy toward the Indian was try to make him like the European settler. The means to this end would be ownership of land through allotments, many believed that "if Indians could have their own, ambition would overwhelm their tribal values and they would want to support themselves as many other Americans did by farming." U.S. government officials trusted that individual land ownership would be "the ultimate settlement of our Indian problem." [25] The Ojibwa were offered 160 acres of land per family and annuities of three dollars per person each year, paid in goods or cash as the government should choose. [26].

Some Ojibwa saw the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 as the best they might obtain since before this time the federal government had given away their reservation land to railroads and lumber companies. [27] They hoped that if they held the deeds to their land their tribe would fare better. But unfortunately, during the allotment period the best 80% of the land originally reserved for Indians passed into non-Indian ownership and Indians received no more than a tenth of its value. [28]

During these same years, there was a concentrated effort to destroy Indian culture by moving the Indian communities to reservations where an agent administered all aspects of their lives: their work, schools, housing and possessions, weekly food rations, travel, religion and conduct. All this was in the name of "education" and "civilization." [29]

When the allotment program was first implemented in 1887, all reservation land not divided among the tribesmen was to be sold at auction based on estimates made by timber cruisers. This led to fraud and collusion. In 1897, Congress passed a law permitting the sale and logging of "dead and down" timber on Ojibwa lands. However, once the operators started cutting, they took every green tree within reach, paying only for "dead and down" prices. Indians complained bitterly about this. [30] They also believed great injustices had been done to them by a government agent who was in the practice of arresting Indians on charges involving liquor, then transporting them to Duluth, Minnesota collecting mileage from them, and letting them walk back.

On September 15, 1898 two incarcerated Indians of the Bear Island Band were rescued by their tribesmen and warrants were issued for the rescuers' arrests. One hundred federal troops were brought in to control the Indians who were resisting arrest and tried to forcibly take them into custody. The Indians continued their armed resistance and on October 5, 1898 the Sugar Point battle began. Within a few weeks the Indians were tried, found guilty, sentenced and fined. Pardons were finally granted them on June 3, 1899, but in the end, little or nothing was done to stop the timber frauds on reservation land. [31]

The Morris Law in 1902 provided for the Ojibwa Indians to be paid the proceeds on the pine timber from their ceded lands, but the U.S. government would retain title to the land, which would become a Forest Reserve. This legislation promoted by General Christopher C. Andrews, two state medical societies and the State Federation of Women's Clubs had its opponents. In 1905 the legislature heard requests to open the Reserve to farms and settlement. The debate resulted in the establishment of the Minnesota National Forest on May 23, 1908. Within the boundaries were the peninsulas and islands previously reserved for the Indians who were to be compensated. Not until the amount of $14,091,976 was agreed upon in 1923 did the Minnesota National Forest come under the complete control of the Forest Service. [32]

In 1928 the name of the Forest was changed. Members of the Chief's office agreed to the validity of naming the Forest after the Native Americans of the Region, but most believed that "Ojibwa" was too difficult to pronounce. Thus, the name "Chippewa," a popular adaptation of "Ojibwa" was agreed upon. [33]

Michigan and Marquette (Hiawatha) National Forests

Located on Michigan's Upper Peninsula, the Hiawatha National Forest touches the shores of three of the Great Lakes—Lake Michigan, Lake Huron, and Lake Superior. This area remained unexplored by Europeans until the mid 1800's. Discovery of copper and iron deposits heralded decades of mining booms. The exploitation of the Upper Peninsula's forests followed. "Sawmills screamed and towns hustled and bustled in prosperity." But then the logging and lumber companies moved on, leaving the slash, debris, and consequent fires behind them. By the early 1900's the Upper Peninsula was almost entirely denuded of its forests. [34]

As early as April 1902 and February 1908, suitable lands in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan were withdrawn from public entry by the General Land Office for National Forest purposes. [35] The Michigan and Marquette National Forests were then established on February 11, 1909. It was decided during that year to place a Ranger on the Marquette. Gene Green of Traverse City was hired and arrived at Brimley to assume his duties, of which he admittedly knew very little. There were no roads through the woods, no telephones, and the first lookout towers were scaffolds built in the tops of tall trees. In 1912 the Ranger's cabin and office were built in a lovely Norway pine grove. Dubbed the Norway Ranger Station, it served as a gathering place for the logging crews. In 1914 the town of Raco was established by the Richards and Avery Lumbering Company. For a brief time, as long as there was lumber to buy, the town boomed. [36]

In 1915 the Michigan and Marquette National Forests were consolidated. In 1931, the entire area was renamed the Marquette National Forest [37] and the Hiawatha National Forest on the Upper Peninsula was established. Like other National Forests, the Hiawatha was part of a significant group of Forests created after the passage of the Clarke-McNary Act in 1924, which authorized the purchase of lands for timber production purposes. For several years after the passage of the Act, W. W. Ashe of the Chiefs Office did general reconnaissance work, looking for suitable areas in Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. The Michigan land which Ashe finally proposed was situated in Marquette, Delta, Schoolcraft and Alger counties. This proposed purchase unit, called the Mackinac, originally included a gross area of 641,860 acres. In 1926, Ashe's report was presented to the National Forest Reservation Commission. Action was not taken until the February meeting in 1926 when the Commission adopted a major acquisition program of 9.6 million acres. There were 1.1 million acres acquired in Michigan and Minnesota "both primarily to aid in timber production and demonstrate forestry practice." [38]

The Hiawatha National Forest was established out of this acreage of the Mackinac Purchase Unit. In 1930, when the Chief's Office asked the Region for suggestions for suitable names for each of the purchase units, seven Indian names were suggested. The name Hiawatha was chosen and approved by the Chief's Office because it was well known. Hiawatha was a Mohawk chief who brought about the confederation known as the Five Nations of the Iroquois Indians. He was also the hero of Longfellow's poem, "Hiawatha."

The headquarters of the original Mackinac Purchase Unit was established in 1928 at Munising, Michigan. The first officer in charge was William B. Barker. In 1933, additional land covering a gross area of 345,253 acres in Alger, Schoolcraft, and Delta counties was added to the Hiawatha National Forest. In 1935, a gross area of 118,000 acres were added; and in 1936, another 142,000 acres were added to the Hiawatha National Forest. The 640,000 acres Dukes Experimental Forest located in Marquette County, a donation from the Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company, was included within the boundaries of the Hiawatha National Forest in 1937. [39]

Under the supervision of the Munising office, a third purchase area was established in the western part of the state. The Keweenaw Purchase Unit was established as the Ottawa National Forest in 1931. Munising remained the headquarters of the Hiawatha until 1935 when the office was moved to Escanaba, Michigan.

Headquarters of the Ottawa National Forest was established in Ironwood, Michigan in 1935. In 1953, some outlying areas totaling 34,977 in the northwest part of the Hiawatha National Forest were eliminated by an Executive Order dated 1961. [40] In February 1962, lands of the Marquette National Forest were merged with the Hiawatha National Forest.

Superior National Forest

The creation of the Superior National Forest "climaxed a period of approximately 30 years of efforts by a few conservation minded Minnesotans seeking to preserve portions of Minnesota's magnificent virgin forest." It was also one result of the attempts of one great man to secure recognition of forestry practices in Minnesota. [41]

General Christopher C. Andrews, who was later to be characterized as "The Apostle of Forestry" in Minnesota, had served as the U.S. Minister to Sweden and Norway from 1869 to 1878. He was impressed with the different aged forests, managed in a checkerboard fashion by the Swedish forestry system. Upon his return to St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1880 he acted as chairman of a Chamber of Commerce committee whose purpose was to secure a donation of federal land for a School of Forestry. The committee prepared a report to Congress in which Andrews wrote of the land that had been wasted through legal fraud and careless timbering practices, but nothing came of these efforts. In 1882 Andrews continued the crusade by reading a paper to the National Forestry Congress on "The Necessity for a Forestry School in the United States." [42]

For the next 20 years Andrews published various articles on the prevention of forest fires and the need for the establishment of conservation practices. In 1895 Andrews was appointed the state's Chief Fire Warden, a position from which Andrews relentlessly appealed for a system of Forest Reserves in Minnesota. Finally, on June 27, 1902, a 225,000 acre Forest Reserve was established which eventually became the Chippewa National Forest. After this success in the upper Mississippi River country, Andrews turned his attention to promoting Forest Reserves in what is now largely the Boundary Waters Canoe Area of the Superior National Forest. [43]

Although Andrews had acquired a national reputation as a lecturer on forestry topics and as a promoter for state and federal forests, Minnesota lands were not being offered for ownership. The farmer oriented legislature were intent on clearing trees for more farms. "In most cases county commissioners would not even turn over long tax delinquent lands for forestry." [44] Consequently, Andrews appealed for 500,000 acres from the public lands which yet remained in Cook and Lake Counties. This withdrawal of land from private acquisition was approved in 1902. In 1905 a second withdrawal of land was accomplished, covering 141,000 acres in the Lac LaCroix-Crooked Lake area, on the Canadian border. Another 518,700 acres were withdrawn from land entry in 1908. [45]

Through the efforts of Andrews and a growing number of Minnesotans, the Superior National Forest, consisting of 1,018,638 acres was finally created by President Theodore Roosevelt on February 13, 1909. All of the lands were legally appropriated from public land. [46] Just prior to this National Forest proclamation, another 1.2 million acres along the International Border were established as a game refuge by the Minnesota Game and Fish Commission. Andrews had been promoting the idea of an international park along the border for several years. His efforts were to realize fruition very quickly. Within the next two months after the creation of the Superior National Forest and the Superior Refuge, the Quetico Forest Reserve in Canada was also established. All agreed to keep the entire area in "a state of nature as far as that is possible." [47]

The Superior National Forest acreage was expanded in 1912 and again in 1927. In 1936, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved the addition of 1,215,000 acres to the Superior and declared the Mesaba Purchase Unit a part of the Forest. In the early 1960's President John F. Kennedy approved the addition of another 136,777 acres and provided for a major retraction of purchase unit boundaries. In 1966 the total area administered by the Forest Service was 2,137,942 acres. [48]

Boundary Waters Canoe Area

Contrary to popular belief the Boundary Waters Canoe Area (BWCA), was not created from a natural wilderness. As early as World War I, much of the BWCA had been either burned or cut over. This resulted in a forest growth of jack pine, spruce, balsam, and aspen rather than the earlier stands of red and white pine and white spruce. [49]

The years after World War I saw a great increase in recreation visitors to the Superior National Forest. Automobile transportation, the development of highway systems, and a stimulated interest in outdoor life accounted for more than 12,000 visitors to the Superior in 1919. This marked the beginning, however, of two decades of controversy over the Forest's use and management. By 1922, it was apparent to many, including Arthur H. Carhart, a Forest Service landscape architect, that there would have to be balances struck between several Forest uses in the Superior: the production of timber, the generation of hydropower, and the aesthetic enjoyment of tourists and sports enthusiasts. As a consequence of such farsightedness, the shorelines of the BWCA have been legally guarded and kept in their natural state from as early as 1926.

The Boundary Waters Canoe Area has been the focus of many intense debates between a variety of interests: Congress, the state of Minnesota, the Forest Service, land developers, industrialists, conservationists, loggers, resort operators, outfitters, sportsmen, and most recently, snowmobilers to name just a few. The story of this area is one of the most lively and instructive of all in the history of the Eastern Region.

Huron National Forest

The forests which originally grew on the Michigan land now known as the Huron National Forest were also first inhabited by the Ojibwa Indians. One of the Forest Districts, Tawas, is named for a Ojibwa chief, O-Ta-Was, with whom some of the early fur traders bartered. The region was first settled by Europeans in the 1850's. In 1854, H.C. Whittemore settled his home in Tawas City, with an objective making lumber from the extensive forest of white pine. All of the earliest towns of the region, until the 1870's, originated as lumber camps. The largest mills operating were S. & C. D. Hale, C. H. Whittemore, East Tawas Mill Co., Iosco Mills, Adamas Swanery Co., and Orlando Newman Co. In 1890 each of these mills sawed between 1 million and 8.5 million board feet of lumber. In addition, vast cuttings of unsawn logs were floated down the rivers to mills at Tonawanda and Buffalo, N.Y. "It has been stated that half the houses in Buffalo are made of lumber from the Huron National Forest vicinity." [50] Railroads were built in the 1870's, which facilitated larger timber harvesting, until the 1920's when the supply of timber and agricultural products had nearly run out.

During the years of the most intensive logging, 1890-1905, the streams and rivers of the area were decimated by the log rafting. Fires destroyed many of the slash areas as well as uncut land. Furthermore, because of the soil and climate conditions, much of the farm land reverted to the State through delinquent taxes. Beginning in the early 1900's, efforts were begun by interested groups and citizens to protect the forests and to regenerate the barren lands. The Huron National Forest, which was first known as the Michigan National Forest, was created largely out of public domain land. [51]

On February 11, 1909 Theodore Roosevelt officially proclaimed the creation of the Michigan National Forest. During 1927 and 1928, about 60,000 acres were bought, another 15,000 secured by exchange, and still further blocks totaling 76,000 acres were in the process of being negotiated for acquisition from the state. On July 30, 1928, the name of the Forest was changed from Michigan to Huron. The Huron's headquarters were at Oscoda, Michigan until 1911 when a fire wiped out the office, and East Tawas became the home of the Supervisor's Office. [52]

On July 11 and 12, 1911 a fire began in brush just outside the towns of AuSable and Oscoda. A strong shifting wind carried the fire through the towns causing $10 million in property loss. According to Forest Service personnel, no records exist of any fires which destroyed much mature timber in the Huron vicinity. However, slash fires which followed the logging crews occurred repeatedly and are responsible for the scarcity of timber except jack pine. Between 1913 and 1927, an average of 5,396 acres of cut-over land burned annually. By 1945, eight fire towers had been built in the Huron. Organized fire control techniques greatly decreased the average number of fires per year. From 1928-1944 an average of only 915 acres of the Huron burned each year. [53]

The Huron had small tree nurseries on it as early as 1910 in accordance with the early policy of managing a nursery at each Ranger Station. [54] Jack pine proved to be the most suitable planting stock. Today the forests are covered by mostly 20 to 60 year old trees. The many acres of pine and other trees planted by the CCC are now productive forests. [55]

Economic and Demographic Effects of National

Forests

Most of the lands brought into the National Forest System of both Regions 7 and 9 during this period were severely abused and wasted. These once-forested areas were never prime agricultural land. After the forests were harvested, little was left to support an agricultural economy, and there were no other industries to sustain a growing population. The logging camps, mill towns, railroad towns, county seats, and trade centers declined steadily. The population declined, and permanent depression set in. A sparse population of hand loggers, marginal farmers, small merchants, and others who provided goods and services hung on, probably because they owned property and had no where else to go. [56]

An area such as the one just described was a suitable candidate to be a Forest Service Purchase Unit. Landowners who thought their land was worthless now had a buyer at a fair price. In the time-honored tradition of the American frontier and their grandfathers, they could now "pull up stakes," leave the land they had exhausted, and move on to new opportunities. Even though the purchase by the government of exhausted land in a given area might have been a blessing at the time, it was not a long-range cure for an ailing local economy. New jobs would be created by the Forest Service, but these people would be engaged in rebuilding the forests and the soils, and it would be a long time before the logging industry would again be viable in the area. Meantime, much of the land, up to half in some areas, would now be in government hands. It would be taken out of private production, off the tax rolls, and would no longer be available for people to live on.

In effect, the areas administered by the Forest Service were taken back in history. They were "de-developed," to coin a word, and although they might have an economic future, development would have to be more gradual and diverse than before. The role of the Forest Service and National Forest management in the redevelopment of local economies was a long term goal. The first job of the Service in such areas was to regenerate the forests and protect the land and wildlife. Certainly the Service wanted to help the local economies and people and, in the long run, it probably did, but the fundamental responsibility was to restore the lost forests of the entire nation.

Fire Control

Part of the motivation to establish the National Forests in Lake States Region had been to prevent the kind of forest fires which had occurred in 1910 and had cost many lives. The disaster was of such magnitude that action by the federal government was clearly indicated. Although the action would have to be taken with the cooperation of the states, the states would have to be helped in developing fire protection programs and provide minimum standards of operation. There was also the problem of fire prevention and suppression on the National Forests. This was clearly the job of the Forest Service. Over a period of decades a comprehensive program for fire control in the United States did emerge. Also emerging in 1950 was Smokey Bear, probably the most widely recognized program symbol in the country.

Region 9's Place in the National Forest System

From its earliest beginnings in 1908 with the creation of the Minnesota (Chippewa) National Forest, Region 9, had grown in size and importance. By the time of World War II, it was clear that the Region had taken its rightful place among the Regions of the Forest Service. It was leading the way in improving forestry and fire protection practices in the Lake States and in restoring cut-over and abandoned lands.

Reference Notes

1. Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary of Land Adjustment and Classification, Region 9, 1929-1962" (Eastern Region ca. 1962), Regional Office Files, p. 3.

2. Report of Leon F. Kneipp to the Chief, November 19, 1928, as quoted by Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," pp. 3-5.

3. Robert Y. Stuart to Secretary of Agriculture, December 20, 1929, Chiefs Office Correspondence, Region 9 File, NA RG 95.

5. Robert Y. Stuart to Regional Forester [telegram], December 22, 1928, as quoted by Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," p. 1.

6. Robert Y. Stuart to Earl W. Tinker, February 18, 1929, Chief's Office Correspondence, Region 9 File, NA RG 95.

7. Information From Howard Hopkins as Compiled by J. Wesley White, Historian, Superior National Forest, January 12, 1972, pp. 3-4.

8. Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," p. 6.

10. Region 9 Monthly Bulletin, September, 1929, as quoted by Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," p. 20.

11 Shelley E. Schoonover, Regional Bulletin, April 1932, as quoted by Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," p. 21.

13. The Courier, February 6, 1932, NA RG 95; and Earl W. Tinker, "Report to the Forester, Calendar Year 1930," December 23, 1930, Records of the Division of Recreation and Lands, Item 86, NA RG 95.

14. Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," pp. 25-27.

15. Daily Contact, passim 1938, 1939, 1940.

16. Earl W. Tinker, "Report to the Forester."

20. Earl W. Tinker to the Forester, December 24, 1930, Records of the Division of Timber Management, Item 72, NA RG 95.

21. Ed A. Sherman, Memorandum for the Forester, January 28, 1931, loc. cit.

22. Robert Y. Stuart to Regional Forester, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, January 27, 1931, loc. cit.

23. The Land of the Ojibwa, Ojibwa Curriculum Committee, American Indian Studies Department, University of Minnesota and the Educational Services Division, Minnesota Historical Society, pp. 1-5.

25. As quoted in Roots, a magazine published by the Minnesota Historical Society, Vol. 14, No. 3, Spring 1986, p. 6.

26. The Land of the Ojibwa, p. 30.

28. The Land of the Ojibwa, p. 36.

31. A History of the Chippewa National Forest, no date, pp. 3-5, and The Land of Ojibwa, p. 38.

32. Historical Classification and Land Adjustment of the Chippewa National Forest, 1908-1962, pp. 1-4, Regional Office Files.

34. Diane Y. Aaron, "A People's Legacy," compiled by Diane Y. Aaron, Hiawathaland (Hiawatha National Forest, 1981), p. 2.

35. Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary," p. 1.

36. Diane Y. Aaron, "A People's Legacy," pp. 2-3.

37. Chronology, pp. 28, 40, 62.

38. Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary, Hiawatha National Forest 1925-1962, 1963."

39. "A People's Legacy," p. 5.

40. Harold P. McConnell, "Historical Summary-Hiawatha."

41. J. Wesley White, "Historical Sketches of the Quetico-Superior" (May 1967), p. 1, Regional Office Files.

49. "The Boundary Waters Canoe Area, A Synopsis of Historical Events," n.d., Regional Office Files.

50. "Huron National Forest: An Historical Summary," n.d., pp. 2-5, Regional Office Files.

51. "Thoughts, Observations, and Suggestions," from Wayne K. Mann, Forest Supervisor, Huron-Manistee National Forest, September 4, 1986, Regional Office Files.

55. "Record of Decision for USDA-Forest Service, Final Environmental Impact Statement, Huron-Manistee National Forest's Land and Resource Management Plan," p. 5.

56. William E. Shands and Robert G. Healy, The Lands Nobody Wanted (Washington: The Conservation Foundation, 1977), p. 3.

|

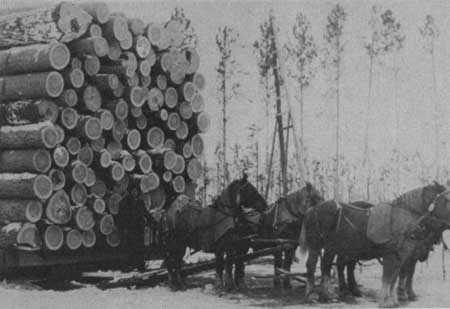

| Horse drawn sled, northern Minnesota, early 1900's. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

region/9/history/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 28-Jan-2008