|

Looking At History: Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 1600 to 1950 |

|

INTRODUCTION

This book explores three and one-half centuries of south central Indiana history. Our purpose is to bring to life our region's historic past by telling the story of its peoples and their lifeways. The context of our story is the Hoosier National Forest and its surrounding area, a unique geographic region.

The point of view we bring to our task is not the one many people may think of when the word "history" is used. We are most interested in presenting a picture of what life was like for "ordinary people" at different times in the past, rather than giving accounts of political happenings or descriptions of the careers of famous people.

Another goal of this publication is to expand interest in historical preservation and research in south central Indiana. There are standing historic structures and many historic archaeological sites located in the Hoosier National Forest and surrounding areas. The Forest Service is dedicated to preserving historic resources, and to interpreting them to the public, so that visitors to the Hoosier National Forest may learn about the region's past. Historic resources are not merely "relics" to be saved. They can provide a wealth of information on how former residents lived, played and worshipped, and how they interacted with the natural environment.

Our study looks at both the day-to-day living patterns and the material side of how people lived: where they built their houses, churches, stores and schools; how they made a living; what kind of houses they built; what kind of tools they made and used; how they farmed. We will also try to picture how people carried out their social and religious lives. What kind of households did people live in? Where did they worship? When and where did they gather for social occasions? In addition to discussing lifeways, we will note how everyday people were connected with events and culture changes that took place on a larger scale.

Culture history covers people, place, and time. Let's take a closer look at each of these elements.

People

Many people view the pioneers as being "the" people of history, but this is not an accurate picture. American Indians were the first people to tame the wilderness. These Native Americans not only preceded the pioneers in the area but occupied the region for thousands of years before written accounts began. A separate book in the "Windows on the Past" series covers the prehistory of the region.

Despite the thousands of years that various Native American groups had lived in our region, the period of time in which they interacted here with Europeans was limited. The most extensive contact between Europeans and Native Americans in what was to become Indiana occurred before the Revolutionary War. During this time, Native Americans associated with and sometimes settled near the French who established trading posts on the Wabash River at Vincennes and at Ouiatenon, near the present city of Lafayette.

European settlers came to the area in far greater numbers after the Revolutionary War. Most of these pioneers were not truly Europeans, but were European-Americans--people of European descent whose families had immigrated to this continent during the Colonial period. Historians recognize regional distinctions among cultures that developed in different sections of the original colonies. These differences in northern and southern cultures were reflected in our region in the lifestyles of the European American pioneers who settled here.

Other early settlers were true Europeans, immigrants who came almost directly to southern Indiana once land was available for purchase. African Americans were also among the pioneers: "free black" farmers and others who came to our area from southern states.

| |||

|

Figure 1: This log house was built about 1830 in the Crawford Upland

hill country of Greene County by the Bingham family. It was dismantled

in 1984 and now stands reconstructed in the Monroe County Historical

Museum, in Bloomington. The display includes pioneer era furnishings as

well as the house itself. Edmund Bingham died in 1852 at the age of 78. An appraised inventory of his belongings has been preserved and shows that the home was prosperous and comfortable. The following listing reproduces the original spelling and notes (*) those items that were selected by Bingham's widow as her share of his estate:

|

Despite the ethnic and cultural diversity of the people who lived here historically, the Hoosier National Forest region did not become much of a "melting pot." The earliest inhabitants, the Indians, were forced to leave. The European Americans and European immigrants brought in various cultural traditions and held on to some of them. Many of the African Americans stayed a relatively short time and left for reasons still not fully understood. Instead of a melting pot, an ever-changing cultural mosaic was created by the different peoples in our region. This is not to say that there was no socialization, including intermarriage and assimilation, among peoples of differing groups; genealogical research helps us to know that families today have ancestors from different cultures and races.

Place

The Hoosier National Forest is part of a distinctive nine-county region. The area is characterized by its hilly terrain, featuring rugged upland ridges separated by narrow valleys. Our geographic focus is this upland area of south central Indiana, though we look most closely at the tracts of land now managed by the U.S. Forest Service.

Until recent times the bulk of the population in our region lived outside of towns and cities, and so we focus on the rural sections of the hill country. Since pioneer days, however, rural life has been linked to towns, particularly to the centers of local government and commerce. Our picture of the rural past would be incomplete without some account of the small towns and cities in the area, and the connections among the different elements of our landscape.

Time

We divide the time span from 1600 to 1950 into four periods:

Cultures in Transition: Native Americans, 1600-1800.

Transplanted Cultures: Pioneer Settlement, 1800-1850.

Regional Distinctiveness: Tradition and Change, 1850-1915.

Twentieth Century Changes, 1915-1950.

Although no sharp breaks occur in our 350 year time-line, we think these periods best reflect culture changes and their pace.

|

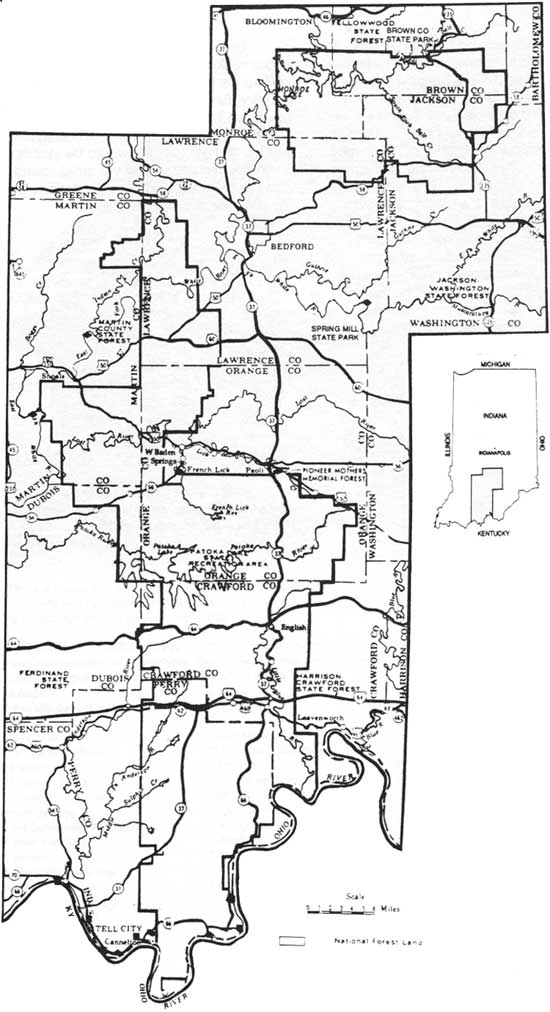

| Figure 2. Cities, towns, and modern highways in the nine-county Hoosier National Forest region. The Forest has two units, a northern one in Brown, Monroe, Jackson, and Lawrence Counties, and a larger southern sector in Lawrence, Martin, Orange, Dubois, Crawford, and Perry Counties. |

Sources for History

To provide a "window" on a past that includes ordinary men, women, and children, we have made use of a wide range of historical sources. And, just as ordinary people combined years ago to create the history of our region, people today are working to discover, preserve, and interpret new sources for historical knowledge.

Some of these sources are present on the landscape itself. The Hoosier National Forest has over 330 known historic archaeological sites and structures on its lands, and others are recorded for the surrounding area. Many more sites exist in areas that have not been checked. These sites, when properly preserved, protected, and studied, are a valuable source for history. They are especially important to the history of "ordinary" folk, whose accomplishments are generally bypassed in published books on local history.

|

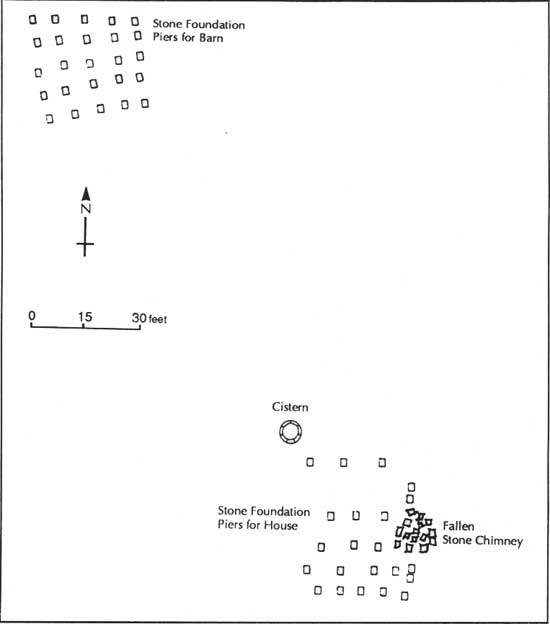

| Figure 3: Map of surface features at an historic archaeological site in Martin County. Based on the arrangement of stone piers, the house may have had an added room or porch on its north side. |

|

| Figure 4: William (Billy) Carter is listed in the 1850 census as a farmer and miller in Monroe County. |

Other sources are to be found in the homes of south central Indiana. Old photographs, diaries, receipt books, letters, family papers--all of these items can help shed light on lifeways of the past. Another information source lives on in the minds of people. Elderly residents of the region remember the early part of this century, and their memories vividly illustrate a way of life before electricity and automobiles were commonplace. Their accounts, whether taped as oral history or written down as memoirs, provide an eye-witness view of history. This information is valuable to us now, and will become even more valuable over time.

There are many, many more examples of these three types of information sources--historic, archaelogical sites and structures, family records, oral histories--still to be discovered, reported, and preserved. Only then can they be useful to historians, and appreciated by local residents and visitors.

At the back of this book, there is a list of local and state historical museums which preserve donated photos, documents, and material items. We also list historical organizations in the region which assist people who want to learn about or compile their own family histories.

Other historical sources used in compiling this book are available for further reading and study, including: state histories; county histories; topical studies (such as works on house types, or studies on regional immigration); government records (local, state, and federal); and maps and survey information.

We provide a short list of suggestions for supplemental reading at the back of this book. Also, wherever a direct quotation is used, or reference to a particular idea is made in this book, the source is cited in the end notes.

As you read this account of the history of our region, you may at times be struck by what is not known about a particular topic or time period. We believe it is important to let gaps in knowledge show, rather than to fill them with guesswork or to hide them. In our view, historical understanding is an ongoing process of discovery and interpretation. What we accept as historical truth today is bound to be added to and revised tomorrow. By making obvious the present limits of our knowledge, we hope to show how much is still to be learned about the past, perhaps with the help of readers like you. We provide a special section "History in the Making" at the back of the book, to guide readers interested in participating in the historical process.

Geographical Setting

The Hoosier National Forest is located in south central Indiana, and incorporates portions of nine counties: Monroe, Brown, Jackson, Lawrence, Martin, Orange, Dubois, Crawford, and Perry.

To best understand the history of the region, it is important to know something of the geography, plant and animal life, and climate of the area.

|

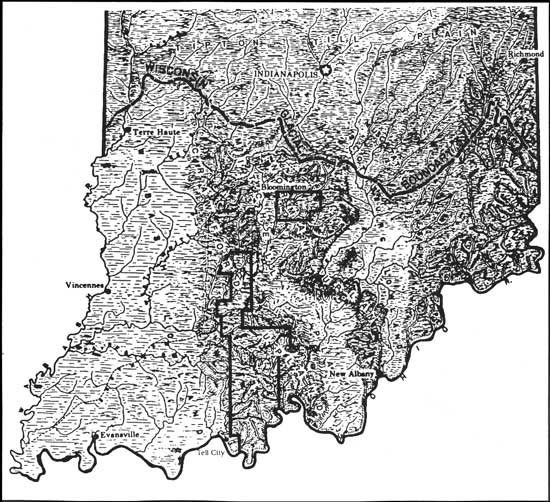

| Figure 5: The Hoosier National Forest is situated in the unglaciated hill country of southern Indiana. Note the southern limit of the Wisconsin glacier, which was reached about 20,000 years ago, and the extent of the Crawford and Norman Uplands. |

Geography and Geology

The most striking physical characteristic of our region is geological: Hoosier Forest lands lie almost entirely in rugged, hilly terrain. In fact two different physiographic zones make up these south central Indiana hills, the Norman Upland in the north of our nine-county region and the Crawford Upland in the center and the south. The terrain of these two hilly zones is the result of the type of bedrock present, and the pattern of glacial activity 125,000 to 20,000 years ago, before any humans came into the area.

Though the glaciers did not flatten our region and cover it with rich till soils, they did affect the landscape, as water from melting glaciers carved out stream and river beds. After the glaciers retreated, waterways in our region became slow-moving and meandering, their flow of water much less than during glacial melting. The gentle streams and shallow, small rivers in our region were suitable for flatboat navigation in historic times, and served as important routes for transporting goods, particularly in the early 1800s.

The principal waterway of our region is the Ohio River. Modern tugboats push barges up and down this river, following the same course as Native American dugout canoes centuries ago and the paddle-wheel boats of the last century. By connecting with this water "highway," settlers in our region had access to markets as far away as New Orleans.

The Norman Upland includes the northernmost parts of the region, in Monroe, Brown, northern Lawrence, and Jackson counties. This upland region consists of narrow ridges, steep slopes, and narrow, V-shaped valleys. The best places for building in this area are on the ridge tops, but even there flat expanses are not common.

The Crawford Upland includes lands in western Monroe, southern Lawrence, Martin, Dubois, Orange, Crawford, and Perry counties. Here the topography is more diverse, though similar to that of the Norman Upland. The land here includes wider ridge tops and many natural features of interest to historic residents of our region. Some of the caves common to the zone were used early in the historic period as sources for minerals. Wyandotte Cave is located near Hoosier National Forest lands; it was mined as a source for epsom salts at least as early as 1818. Other area caves were mined for their nitrate-rich deposits during the War of 1812 and later, to produce saltpeter used in making gunpowder. Saltpeter also had uses in food preservation and medicine. [1]

Mineral and freshwater springs are another feature of the Crawford Upland. Freshwater springs were a critical resource during historic pioneer days and through the 1800s; homes and farms were often established near larger springs. Mineral springs were also important in our region. Early on, salt springs were known to be attractive to game animals and thus were good hunting spots. Some also were the scene of commercial enterprise in the pioneer era, such as the salt manufacturing along Salt Creek in Monroe County. This business produced as much as 800 bushels of salt a year in the 1820s, when salt imported from elsewhere was "a scarce and costly article." Later, a popular tourist industry grew up around the Pluto Springs at French Lick and West Baden, in Orange County. [2]

Erosion between layers of different rock types - harder sandstones and softer limestones - created many cliffs and overhangs in the Crawford Upland. While these protected locations are most well known for their use by people in the prehistoric era, such rockshelter locations were also used during historic times for storage, as shelters for livestock, and as living sites.

Extensive limestone deposits are other geological features which had a great impact historically. The Norman and Crawford Uplands are separated by a physiographic zone called the Mitchell Plain, which has a flatter, more rolling terrain. It is in this zone that bedrock limestone deposits are most exposed, allowing quarrying to become an industry which had a marked economic effect during the late 1800s and on into the present day. The stone in our area is the highest quality construction limestone found in the country, resulting in national demand for this building material.

Climate

The climate in our region is temperate and rainy, featuring extreme seasonal variation in temperature. In the northern part of the region, the average summer (July) temperatures are 89° (high) and 64° F. (low); winter (January) averages are 42° (high) and 24° F. (low). In the southern part of the region, temperatures average two to three degrees higher.

The growing season also varies from the northern to the southern part of the region. The farming season is as much as 25 days--nearly a month--longer in the southern area, near the Ohio River. Local variations based on topography and elevation also affect the length of the agricultural season. [3]

Plant and Animal Life

The vegetation pattern in the Hoosier National Forest region has changed dramatically from what it was 200 years ago. Around 1800, the entire area was "old growth" forest, except for small open grassy areas over rocky outcrops in the southern part of the region. Both the Crawford and the Norman Uplands featured oak-hickory forests, with some beech-maple forest areas in stream valleys. A study made to reconstruct what the forest was like in the early 1800s suggests that ridge tops and south- and west-facing slopes of the Crawford Upland were dominated by oak and hickory trees, while north- and east-facing slopes had a more varied tree cover. This variety offered a range of plant foods for humans and their livestock, as well as for wild game animals. [4]

The forest cover was not an advantage to the settlers who began arriving after 1800, however. Those who wanted to farm, as most did, had to clear field areas before they could make a living from the land in the traditional manner. In addition, people used lumber extensively for building homes and other structures. The land that was so densely wooded in 1800 was cleared as quickly as the settlers could manage it. Land clearing continued into this century; the wooded land flat enough to farm or use as pasture was converted to new fields as older ones became too eroded or depleted to be productive. Although many farm families left wooded tracts on the steepest slopes and in wood lots, so they could have a supply of wood for building and heating, by the time the Forest Service began buying land in the 1930s, very little forest cover existed in the entire region. Most of the forest we now see on visiting the Hoosier National Forest and its environs is not the mature old growth forest encountered by the earliest settlers. Instead it is the result of systematic replanting accomplished since the 1930s. [5]

|

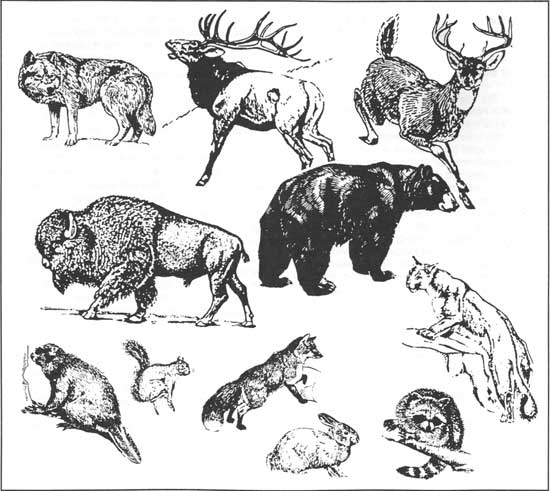

| Figure 6: Mammals common in the 1600s and 1700s. By the early 1800s beaver had been "trapped out," bison were very rare, and cougar, wolf, bear, and elk were fast disappearing from our region. Deer and smaller mammals were important sources of food to pioneers, though deer eventually became over-hunted and could not reproduce. |

The animal species which populated the area in the early 1800s and were hunted by early settlers included deer, bear, raccoon, squirrel, and turkey. Eastern bison had recently moved out of our region, though they had been present in great numbers in the 1600s and 1700s. These large beasts migrated through the heavy forests of the upland areas of our region, as they traveled between salt springs south of the Ohio River and the grasslands along the Wabash River. Moving in herds, the bison created the broad trail later known as the Buffalo Trace, a route used by historic era Indians and early European travelers and settlers. Passenger pigeons are another species that was extremely plentiful. A traveler in the early 1800s near Paoli described the effect these birds had on the environment:

Some of the trees ... exhibit a curious spectacle; a large piece of wood appears totally dead, all the leaves brown and the branches broken, from being roosted upon lately by an enormous multitude of pigeons. [6]

|

| Figure 7: Flocks of wild pigeons were once so large that hundreds of birds could be shot in a short time. |

This species was so over-hunted that, despite its vast numbers, it had disappeared from the wild by the late 1800s, and became extinct in 1914 when the last specimen in captivity died. [7]

Wild animal species were important food resources for the pioneers, especially in their first years of settlement, before they could support themselves by farming. Hunting of mammals also produced furs to sell and trade. An Englishman traveling through our region in the early 1820s described meeting with two young men near the town of Hindostan, in Martin County:

They had only been out two days; and not to mention a great number of turkeys, had killed sixteen deer and two bears, besides wounding several others. The bear is much more esteemed than the deer; first, because his flesh sells at a higher price; and secondly, because his skin, if a fine large black one, is worth two or three dollars. [8]

The passenger pigeon was not the only species to be hunted or crowded out by the European American settlers. Bear disappeared before 1850. Deer and wild turkey were gone or nearly absent in the state by the mid- to late 1890s; these two species were re-introduced to the state in the 1930s (deer) and the 1950s (turkey). Many other animals that once were plentiful are now rare or absent. [9] Judging by how they affected the plants and animals of the region, the early settlers were much more concerned with making their living off the land than they were with long-term conservation of the resources they used.

|

| Figure 8: Painting of Miami chief Francis Godfroy, by George Winter, ca. 1837-39. His dress and hair (in a "queue") followed the European style, like many of the Miami in the early 1800s. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

|

9/hoosier/history/intro.htm Last Updated: 21-Nov-2008 |