|

Looking At History: Indiana's Hoosier National Forest Region, 1600 to 1950 |

|

HISTORY OF SOUTH CENTRAL INDIANA

Cultures in Transition: Native Americans, 1600-1800

It is common to date the beginning of the historic era in the Hoosier National Forest region to the late 17th century, with the arrival in the area of the first European traders and explorers. In fact, dramatic changes had already taken place in the entire Great Lakes region before these traders and the later settlers arrived.

When Europeans began colonizing the Eastern coastal areas of the North American continent, Indian populations were displaced from that region. Many of these groups moved westward, and in turn displaced other Native Americans who had been living in our area. The Iroquois and allied groups also raided or threatened the villages of other tribes, causing Indians in the areas that later became Indiana, Illinois, and Ohio to seek refuge elsewhere. [10]

Thus, the Native American groups encountered by the first European American settlers in Indiana were not those groups, or "tribes", which had originally inhabited the area. Information about the original native inhabitants comes primarily from archaeological study of prehistoric sites.

It is difficult to determine which tribal groups were present in the 1600s, for several reasons. Very little historic (that is, written) evidence for the area exists from this period. Also, archaeological evidence is of only limited use in answering questions about tribal identity. The Native American material culture of that era changed rapidly, as soon as Indian peoples had access to European trade goods. And many Indians stopped only briefly in our region, before moving farther west. Despite our gaps in knowledge, Native American groups present in southern Indiana and adjacent areas in the decades just before the arrival of European American settlers include the Miami and Piankeshaw, and possibly the Shawnee and groups speaking Muskogean and Dhegiha Siouan languages.

Some scholars think that at least some of the Miami Indians can be traced back to certain late prehistoric (Upper Mississippian) archaeological cultures. Upper Mississippian groups are known from the archaeological record to have lived in northwestern Indiana and northern Illinois during the 1400s through the 1600s. [11] Similarly, the Shawnee may have been linked with the Fort Ancient culture, an archaeologically known culture of the 1600s in Ohio. However, not all Fort Ancient culture sites of that period are necessarily Shawnee, and various bands of the Shawnee may be archaeologically linked to other prehistoric cultures. [12]

|

| Figure 9: "Open Door" (Ten-squat-a-way), known as the Shawnee Prophet (brother of Tecumseh); 1830 painting by George Catlin. |

|

| Figure 10: Drawing of a Delaware Indian, about 1800. |

In southwestern Indiana and adjoining portions of Illinois and Kentucky, European trade goods have been found at prehistoric Mississippian villages known on the basis of radiocarbon dates to have been occupied in the 1600s. No historic records mention this regional population, and thus its ethnic identity is unknown. Neither the Miami nor the Shawnee are likely candidates. Of the more distant Native American groups recorded by early European travelers, this unknown group's identity might be linked to some of the Muskogean-speakers south of our region or some of the Dhegiha Siouan-speakers to the west. [13]

The information for the 1700s is more definite, but still sketchy. Three related groups, the Miami, Wea, and Piankeshaw, were present in northern and west central Indiana after 1680. Apparently, the Miami claimed they held all lands from northern Indiana and central Ohio to the Ohio River. Around 1770, the Miami and Piankeshaw allowed Delaware from Ohio to occupy southern and central Indiana between the White and the Ohio rivers. There are said to have been a few Delaware towns in this area after that date, though most Delaware and related Munsee settled farther north.

Some groups of Shawnee were briefly in southern Indiana, though their homeland is to the east and south of Indiana. By 1788 this group is reported to have settled temporarily at the confluence of the White and Wabash rivers south of Vincennes, and possibly passed through the Hoosier National Forest region. The Delaware, like some Shawnee groups, originated farther east. The Wyandotte, a Huron-speaking group from the Great Lakes area, also migrated into our region at about the same time. The Kickapoo, also from the north, came to the central Wabash Valley and established villages in the 1740s in the vicinity of a trading center at Ouiatenon, and moved in the 1780s to the Vincennes area. As further indication of large-scale population shifts, some of the Miami, Piankeshaw, Delaware, Shawnee, and Kickapoo had settled along the Mississippi River by 1790; about the same time some of the Potawatomi moved from the Lake Michigan area to the central Wabash. [14]

|

| Figure 11: Painting of Potawatomi chief Kaw-kaw-kay, by George Winter, ca. 1837-39. |

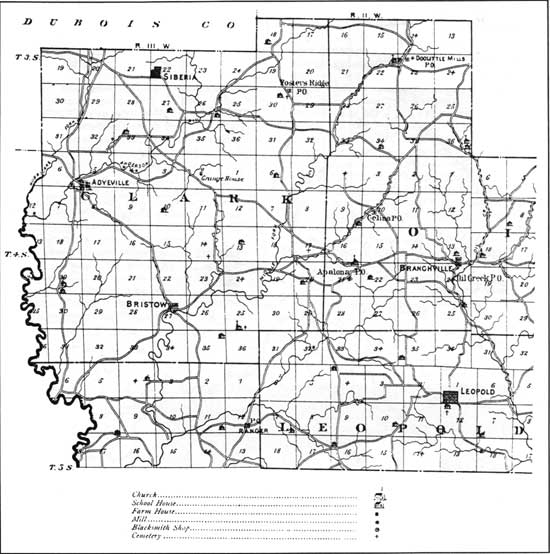

County histories for the Hoosier National Forest region mention several Indian groups present at the time of European American settlement in the early 1800s, or just prior to it. The county histories are not always reliable sources, and we do not know what information their authors used in listing the specific Native American groups. The Piankeshaw and Delaware are named in histories of Jackson, Lawrence, Monroe, and Orange counties; the Shawnee are listed for Jackson, Lawrence, and Orange counties; and the Miami are listed for Monroe and Perry counties. Wyandotte Indians are said to have been present in Jackson, Orange, Crawford, and Perry counties. Sources list Potawatomi among the groups present in Lawrence and Monroe County, though most of this group was situated farther north and west of our region. [15]

Historic Era Native American Lifestyles

There is little direct knowledge of the way of life of the historic Native Americans in southern Indiana. However, anthropological information gathered in northern Indiana and elsewhere gives some clues about the Native American groups which lived in--or passed through--our region. [16]

The Miami Indians had a pattern of alternating between summer villages and winter hunting camps. In the earlier part of the 17th century reports tell of villages comprised of oval lodges, constructed from pole frames. By the late 17th century or earlier, one-room rectangular log houses replaced the traditional house, due to European influence. Villages typically consisted of a number of houses scattered along a river bank; one large village was reported to have been three miles in length. A council house, larger than the dwelling houses, apparently was a feature of each village. The Miami lived along major rivers in northern Indiana and Ohio. Early settlers in our region report meeting Indian hunting parties, but the arrangement of their hunting camps is not recorded.

|

| Figure 12: Reconstructed wig-warn (or wicki-up) typical of the Miami traditional house. The Miami cut saplings of hickory, maple, and willow to build the interior frame of the house. The frame was covered by mats of cattail leaves, which were sewn together by cord made from the bark of basswood trees. The house had an earthen floor and could be large or small, depending on the size of the family. |

The Shawnee seem to have had a settlement pattern and house structure similar to those of the Miami. The Shawnee occupied semi-permanent towns in summer. Their traditional houses were bark covered lodges. By the late 18th century the traditional house form was abandoned in favor of one-room log houses. Shawnee villages had a central council meeting house. Some of these settlements were used as forts during wars with the U.S. in the late 18th century.

|

| Figure 13: Deafman's village, a Miami Indian farmstead, ca. 1837-39, painting by George Winter. This picture illustrates log buildings—cabin, barn, and granary—adopted by native inhabitants soon after contact with Europeans. |

The Delaware apparently used a different settlement strategy. They reportedly occupied semi-permanent settlements in winter, and were mobile in summer. They built their villages on hilltops, either as concentrations of dwellings surrounded by a stockade or as scattered dwellings. Houses consisted of large, multiple-family long houses, which were pole framed and bark covered.

|

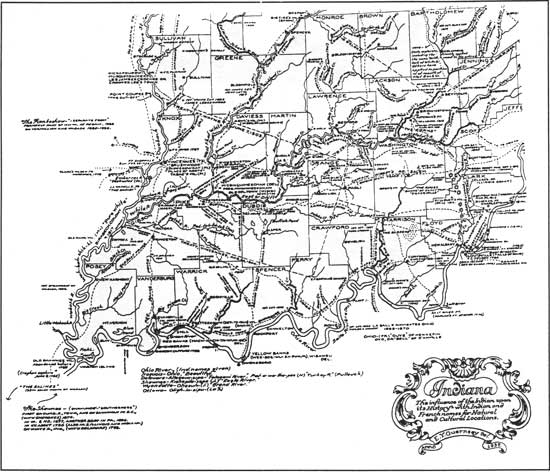

| Figure 14: Historic Indian sites and trails in the Hoosier National Forest region. |

Tools and utensils used by the earliest historic Indiana included: clay pots; pipes of clay and stone; arrowheads of stone and antler; shell beads; and ornaments of native copper. These items can survive through time at a site, and thus it may be possible to build our knowledge of the historic Native American presence in the region through identification and study of archaeological sites. Other more perishable items, which would be unlikely to last over time, include wooden mortars, gourd utensils, fiber baskets, wooden canoes, and leather clothing. Also, the Delaware and Miami are said to have dug storage pits to preserve food; these too can be preserved in the archaeological record if they have not been subjected to later disturbance.

Metal and glass items were obtained from European or European American traders, or from other Indians who had acquired these trade goods. Native Americans traded furs and hides for many types of European and American goods, including blankets and whiskey. Eventually, Indian groups adopted a wide array of new material items, as these became more readily available from traders. Brass and copper kettles replaced their earthenware pots, guns replaced bows and arrows, and European pipes and glass beads replaced traditional smoking and decorative items.

A map compiled in the 1930s shows historic Indian villages and trails in Indiana, including several sites in our region. Locating these or other historic Indian sites is difficult, however. The available material culture and settlement information suggests that early historic Native American sites appear very similar to prehistoric sites. Trade items originating in Europe, which would give a clear indication of dates of manufacture, occur rarely and probably were present at only some of the early historic sites. And, after Native American groups adopted the use of European goods and house styles to replace their own traditional material culture, their cultural remains appear much like early European American sites.

Another problem we face in identifying Indian sites from this period is the transitory nature of the historic Indian presence in the region. The scant documentation suggests that their presence spanned decades, not centuries, and was marked by nearly constant movement and adjustment between groups and territories. [17] Given these circumstances, it is not surprising that direct evidence for the early historic Native Americans in south central Indiana is still elusive.

There is one cultural feature dating from the period of historic Native American occupation known for the Hoosier National Forest. This is the segment of the Buffalo Trace, also called the Vincennes Trace, that runs through the Forest boundaries. This trail was sometimes called the "Lananzokimiwi Trace," a name which seems to be derived from a Miami language phrase, combining words translated to mean "cattle" and "road." It was the major land route across southern Indiana in early historic times, running from the Falls of the Ohio (near present-day Louisville) to Vincennes. The trail, created by buffalo during their migrations and used by Indians and later by Europeans and European Americans, was as wide as 20 feet. [18] It may still be possible to find and preserve sections of the trail in areas that have not been too disturbed. Thus far, the necessary research and field work to achieve this has not been done.

European American/Native American Interactions

The story of Indian and European American relations during the early historic era is a tale of conflict over territory. The land that now makes up our region is a small portion of a larger territory sought by several peoples: Native American groups, the French, and the British. The process by which the territory ultimately came into British, rather than French, dominion during the colonial period is recounted in a number of places. [19]

By the 1770s, British American settlers were living in present-day Kentucky very near our region, despite the Proclamation of 1763 which prohibited American settlement west of the Appalachians. These "squatter" settlements became vulnerable during the Revolutionary War, when the British supported Indian groups in attacks on American settlers in Kentucky and elsewhere. Attacks and counter-attacks established a pattern for the course of the war in the western territory: British and American forces each used the Indians in their fight against the other. Ultimately, the American side won the war, though the victory was based on battles east of the mountains. In our region and throughout the "west," neither side was able to dominate the other.

After the end of the Revolutionary War direct conflict between the Indians and European Americans increased in the Ohio River Valley region. The cause of the dispute was the land itself. The European Americans believed that they now had title to the territory, while Indian groups did not accept this claim of land ownership any more than they had accepted earlier French or British claims.

|

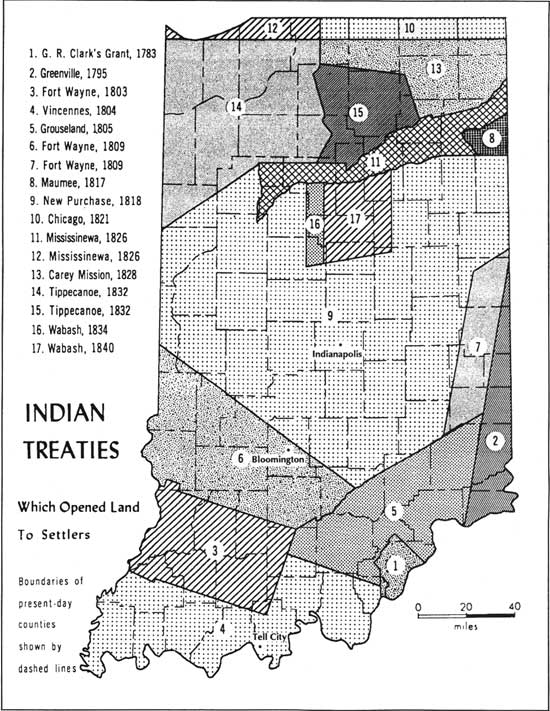

| Figure 15: Treaties between U.S. Government and various Indian tribes were soon followed by European American settlement. Most of the treaties in the Hoosier National Forest area were signed by William Henry Harrison, Governor of the Indiana Territory and Native American groups which included the Shawnee, Delaware, Potawatomi, and Miami. |

The conflict centered on European American expansion north across the Ohio River. Although only a few "squatters" had set up cabins along the north side of the Ohio River, there were already 70,000 settlers in Kentucky by 1790, and many were eager to acquire new lands in southern Indiana, Illinois and Ohio. The Native Americans were just as determined not to relinquish these lands. It took many years of scattered fighting to settle these conflicting claims. The years from 1790 to 1795 and from 1808 to 1814 were particularly marked by Indian/settler conflict in the region, but European Americans forced Indian communities to give up their claims to the land, and eventually most Native Americans signed treaties and moved farther west.

The movement of a European American population into our region was encouraged and organized by two important policy decisions on the part of the U.S. government. The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 provided for the system of government to be used in the area of Indiana and nearby states, then known as the Northwest Territory, including provisions for achieving statehood. The Land Act of 1800 allowed for relatively easy, legal land acquisition by private individuals from the federal government. This was partly accomplished by opening land sale offices within the Northwest Territory. The first office in what is now Indiana was established in 1807 at the former French trading settlement at Vincennes. Land was sold for $1.25 per acre.

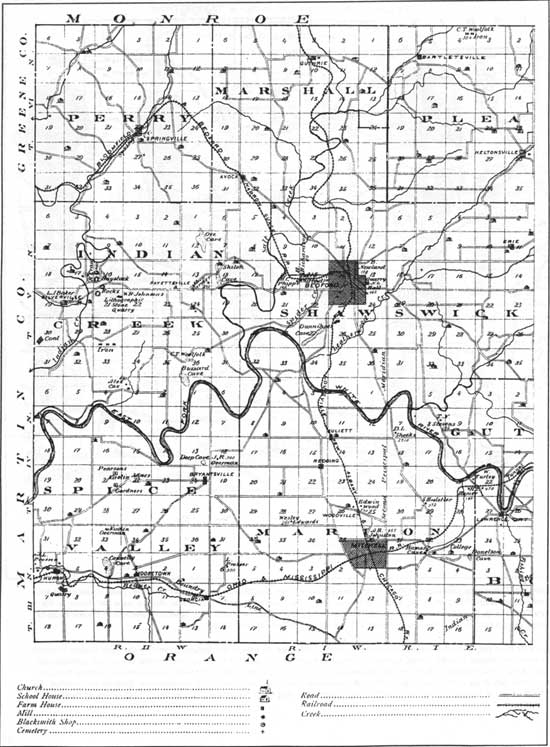

An earlier act, the Ordinance of 1785, had provided for the survey of land into six mile square townships, subdivided into 36 sections, each 640 acres in size. These land subdivisions remain the basis for legal description of land ownership. In fact, the grid of land sections is still clearly apparent in flatter areas, where roads often follow north-south and east-west section lines. In much of our region, roads tend to follow ridges and hollows, so the work of the earlier surveyors is not so visible on the landscape.

A monument and small park in the Hoosier National Forest is dedicated to the work of the early surveyors, The site is the "Initial Point" in the surveying system and the center of our scheme of sections and townships. It is located south of Pine Valley off of State Highway 37 in Orange County.

We know very little about the day-to-day relations between the earliest settlers and the Native Americans in our area. There are only a few clues in the county histories. In Dubois County, the first European Americans settled in 1802, some six miles west of the Hoosier National Forest boundary. According to the 19th century county history, the first settlers lived near some Native Americans. It is recorded that when a family of settlers built a second house near their original one, the first house was used by Indians. "Soon" afterward, however, for reasons not recorded, these Indians "became hostile" and the European Americans vacated their homes and retreated south. The settlers returned, though, and built a block house near their homes in order to protect themselves against Indian attack. Crawford County settlers also built a block house described as a two-story log structure. Other accounts confirm that early settlers were indeed subject to raids by Indians who did not accept the legality of the land treaties, particularly during the War of 1812. [20]

Some of the most extensive contact between Indians and European American settlers in our area appears to have taken place in Jackson County. One location, Vallonia, has long been reported to have been the site of a pre-1800 French settlement, based on the discovery of some abandoned dwellings by the first English-descended settlers in the early 1800s. It could be that these old houses were in fact Indian homes. Native Americans were still in the vicinity in the early 1800s, and we have reports of one marriage between a white, European American man and an Indian woman; the seizing and lengthy captivity of a white boy by Indians; and bloodshed on both sides during fighting. The European American settlers built at least two blockhouses or "forts" in the immediate area, where people, livestock, and valuables could be protected. The locale is reported to have been a fort during the War of 1812, and a reconstruction stands today in the town.

Fighting between Indians and whites was known in other counties, too, though there are also mentions of "friendly" Indians in several instances. In Monroe County, for example, a long-lived resident wrote about the period of the 1820s:

When we first moved here Delaware and Pottawattomie were plentiful. They had a trading house within a half mile of where I now live. They were quite friendly and often would come with their squaws and papooses to stay all night with us.

On the whole, though, references to contact between the two groups in our region are scarce, despite the fact our region became settled by European Americans--and counties were first organized--while a sizable population of Indians remained in central and northern Indiana. There are no known cases of prolonged peaceful European American/Native American interactions, such as occurred in east central Indiana and at the trading centers which existed in western and northern Indiana. [21]

|

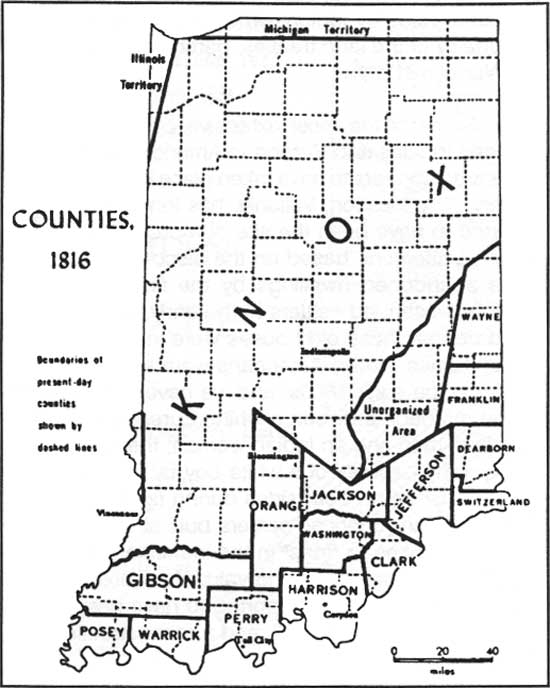

| Figure 16: The nine counties in our region were part of fewer but larger counties at the time of statehood. |

Transplanted Cultures: Pioneer Settlement, 1800-1850

The first decades of the 1800s in southern Indiana were remarkable in two ways. First, one population, the Native Americans, was nearly entirely replaced by another, the European American settlers. Second, the success of the U.S. government policies to encourage settlement meant that it took only a few years to meet the required number of settlers--60,000 residents--for application for statehood.

By 1816, when statehood was granted, the Hoosier National Forest region was populated by immigrants: persons who settled in a new area, bringing with them their own culture and means of livelihood. Who were these settlers? Where did they come from? How, and where, did they live?

Geographic Origins of the Settlers

Historical studies show that a high percentage of settlers came to our region from Kentucky, North Carolina, Virginia, and Tennessee. These southern migrants settled throughout the south central part of the state, including the Hoosier National Forest region. Pennsylvania, and later Ohio, contributed smaller, but significant, populations to the Hoosier National Forest counties. New York, Maryland, and the combined New England states contributed even fewer settlers.

The geographic and cultural origins of the region's most numerous settlers can be pinpointed even more specifically to the Upland South. The Upland South is a geographically and culturally unique area of the U.S. Stretching from western Virginia and North Carolina in the east to northern Mississippi in the west, this region is marked by its rugged, hilly terrain and by the particular character of its people, dialects, and lifestyles. [22]

Upland Southerners: Origins and Culture

Tracing the origins of the Upland Southerners reveals the roots of most of the pioneers in our region. The eastern areas of the Upland South were settled by British and continental Europeans in the 1700s; this population was comprised mainly of English and Scotch-Irish, with some German-speaking peoples. The hill country of the southern U.S. thus became an area in which a variety of cultures were brought together. A unique Upland South culture developed out of this combination of different European cultural traditions. For example, the particular style of log house that developed in the Upland South combined Germanic log building traditions with Scotch-Irish and English house plans. [23]

Upland Southerners for the most part belonged to a middle class of southerners. Often one encounters the stereotype that ante-bellum (pre-Civil War) southerners were divided into just three groups: black slaves, wealthy white slave holders, and poor whites. However, another large group of southerners existed, a middle class of white, land-owning "plain folk" who did not own slaves, but who were also not abjectly poor. The members of this "yeoman class' made their livings raising livestock and farming on their own land. [24]

The pioneer families in south central Indiana also lived by these means. Corn growing along with hog raising on their newly acquired lands was the main occupation of the early settlers. [25]

This basic economic mode was not the only practice brought to Indiana by the settlers from the south. Some of the values and customs described for the southern "plain folk" are echoed in descriptions of pioneer life in Indiana. Thus, in both regions a close-knit family was the core of the social structure, churches were central to community life, and community social and economic life was strengthened by cooperative efforts such as house-raisings and log-rollings. [26]

Settlement and Economy

What lands did these immigrants choose to settle in the Hoosier National Forest area? Steep and narrow stream valleys which abound in our region made the broader upland ridges a logical place of settlement. In our central section, the broader valleys of rivers and major streams offered better farm land and a nearby reliable source of water. Our county histories report that the upland ridges were the preferred terrain, and access to springs was important. It has been suggested that the uplands were preferred for health reasons; diseases such as malaria and "milk sickness" were associated with lowland areas. It could also be that the high ridges were chosen for their similarity to the regions left behind by the settlers. Both emotional ties, such as the comfort of familiar landscapes, and practical reasons, such as the benefits of knowing how to make a living on hilly lands, may have encouraged the immigrants to copy their previous settlement styles. As it stands we still know very little about which tracts of land were in fact the first selected for settlement. [27]

The basic economic pattern in the period of early settlement in our region was a combination of hog raising and corn growing, as mentioned above, with some reliance on hunting. Deer and wild turkey were especially important in the earliest years, though increasing numbers of settlers and the reduction in wild animal populations eventually made hunting unreliable as a means of putting meat on the table. Horses, mules, and sometimes oxen were important to farming, because these animals pulled plows and wagons. Even milk cows and chickens were brought here, or were later acquired through barter or purchase. Dogs--especially hounds--also came with the earliest settlers and were important for protection, companionship, and hunting.

Few records tell us about hunting in the earliest years of pioneer settlement, but one written account describes a bear hunt around 1819. Samuel Hazelett, an early Monroe County settler who was "... more a farmer than a hunter ...," and three other men "... who were called 'hunters' from the fact that they did little else but hunt for a living ...," tracked a bear into a local cave.

They prepared themselves with guns, shot pouches, knives, and two "sluts" (torches), and entered the cave. After squeezing around rocks, they located a bear, and while one man held a torch over it, another hunter shot it.

At the crack of the gun the concussion knocked the light out, and there they were with a wounded bear in darkness.... They had to grope their way back to where they had left their other slut burning.... [T]hey concluded best not to go back into the cave where there was a wounded bear, so they took the other branch of the cave ... and discovered another bear ..., fired on him and wounded him just enough to enrage him.

He came tearing at them, and they all broke for the outlet.... [One man] stepped into a hole and fell down. The bear ran over him, and as he did so gathered up [his] gun in his mouth.... [The other men] fired on him ..., but he had gotten too mad to die.... [One man] crept under the ledge of rock, pretending to be dead.... The bear came and put his nose to the back of [his] neck. He said he thought then that his turn had come, but the bear laid down against him without further molestation, only breathing his stinking breath.... [When] the bear saw proper to get up, ... they soon dispatched him. His head was shot into a jelly. They skinned and quartered him, each one taking a quarter, and left the cave forever. [28]

Early accounts of farm work are also rare, though one brief description includes a vivid picture of breaking the ground:

The farmer did his plowing with a jumping shovel, which had one long share. Nothing was more aggravating than such a plow. If the share caught behind a strong root the plow would either jerk a man severely or jump out of the ground and hit him in the ribs with the handles.... The grain was cut with a sickle or a cradle. Much later ... a reaper was used. [29]

Using both the evidence of reports from the early 1800s and examples drawn from studies of modern-day farmers in the Upland South, we can picture some of the methods used by pioneer farmers in our region. After clearing the land, building a house, and otherwise getting established, farmers probably followed a seasonal flow of activities timed to utilize their land efficiently. For instance, stock-raising and crop-tending could be synchronized so that livestock, particularly hogs, would feed in woodlands while the crops were growing, and then feed on field residue after the crops were harvested. To show ownership of hogs that ran free through the woods, farmers marked their ears with notches or slits; this practice contined as late as the 1880s, according to the a book of ear marks in the office of the Crawford County Recorder. The making of maple syrup in late winter fit into the sesonal cycle between harvest and planting. Reports of the amounts of syrup made show that "sugaring" was a significant part of the annual work cycle for early farm families. [30]

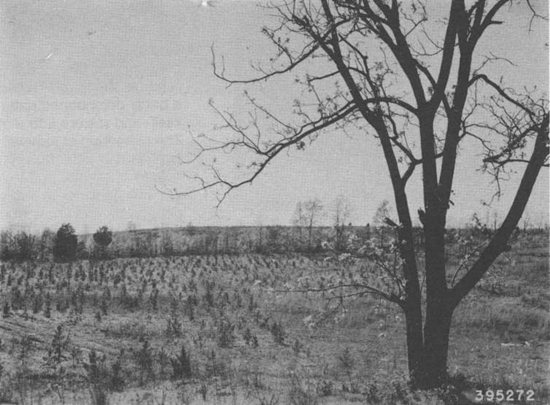

While such farming methods met the short-term requirements of year-to-year survival, the long-term effects on the environment were harmful. Though individual fields and pastures were small in comparison to today's standards, the early farmers soon damaged the shallow soils in the uplands. Later on we discuss the erosion caused by upland land-clearing and plowing, which devastated wide areas of our region.

Research on modern Upland South farmers indicates that they take pride in their ability to survive on their own skill, both in farming and in making and repairing houses, barns, fences, tools, and so on. It has been suggested that this cultural value system has contributed to the persistence of the lifestyle over time, and it is likely that this attitude of self-reliance and cultural conservatism was brought to our region by the early settlers from the Upland South. Though notions of self-reliance may have been a cultural ideal, in actuality cooperative labor--among families and neighbors--ensured the success of early farmers. [31]

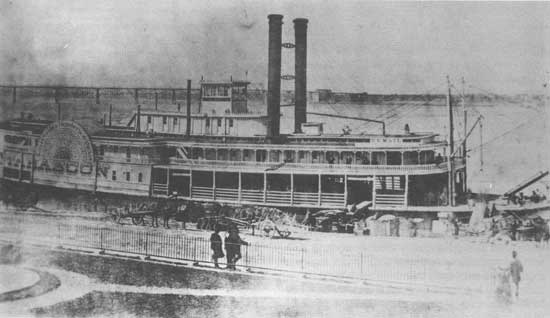

While subsistence farming may have been the pattern for the earliest settlers in our region, it was not long before settlers were able to produce surpluses of goods for export. Export of produce and goods was especially important for those areas nearest to the Ohio River, which was a major transportation route for flatboats and later steamboats. Domesticated animal products, agricultural produce, timber, and the furs, hides, and meat of wild game were exported from Crawford and Perry counties; the Ohio River linked these places with national and international markets via the Mississippi River and New Orleans. Boat building itself was a major trade along the Ohio River in the pioneer era, and other enterprises related to export--such as pork packing--were also present.

The picture of pioneer life shows a true "subsistence" farming pattern, in which the major goal is to satisfy one's own needs on a yearly basis, without attention to surplus production. One account describes part of the pioneer farming strategy:

Certain years the farmers did not plant much corn. They would climb the beech and oak trees in the early spring and see if the trees would have a crop of the mast or beechnuts and acorns.... In case of fruit being grown on the trees then there was not need for much corn. The mast would fatten the hogs well and the meat was thought to be better. [32]

|

|

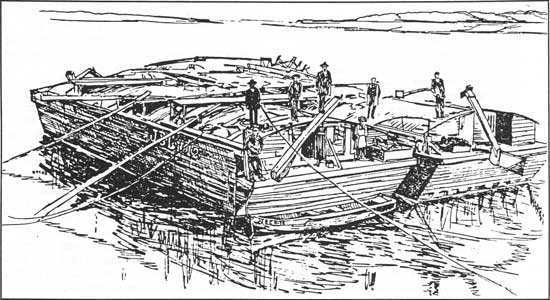

Figure 17: Drawing of early Ohio River shipping by flatboat. Ohio

River towns such as Leavenworth and Tell City were river ports in the

1800s for the export of lumber, line, pork, grain, whiskey, and hay.

Manufactures such as the making of line and barrels and the building of

flatboats and skiffs became important local industries. According to a Crawford County account: The boats were about the size of barges and were covered to protect the crew from the winds and the cargo from the rain and the snow. On the top of the boat and at each end was a steering oar by which the boat was guided.... There were about five men on the boat besides the cook. When the boat was loaded and ready to start the men guided it out into the river and let it drift gently down. Stops were made at most towns and the produce on the boat was sold and other cargoes taken on the boat too. By the time the boat arrived at New Orleans the cargo was sold and the boat was sold or the owner had some steamboat to tow it back. Yet he could hire a new one built cheaper than paying for the towing of the old one back, it was generally left. |

The hill country farther north also had access to the Ohio River through the use of small flatboats on tributary waterways. Farmers had to get their goods to waterways by primitive roads and trails, but once these smaller streams were reached they were navigable during high water in the springtime. One example is Clear Creek, which runs through southern Monroe County before flowing into Salt Creek, which in turn runs through north central Lawrence County to flow into the White River, the Wabash River, and then the Ohio. Lewis Brooks, later an officer during the Civil War, wrote this account of a flatboat trip to New Orleans:

[The trip] required eight weeks. Trips were sometimes made in six weeks in good weather and no intermediate landing.... The trip provisions were furnished and they did their own cooking and took deck or steerage passage back to nearest landing to point of departure and then walked home. The owners usually travelled [steamer] cabin passage home. I did that....

Brooks made the trip as part of his duties working at his father's Martin County store. He also told about the commerce carried out at the store:

The firm carried on a general merchandise business, you might say kept store. They could sell you a silk dress pattern or a fish hook, quinine [for treating fever] or a Webster spelling book, sugar or cream of tartar, sole or side leather or a pair of sewed high heeled boots. They would buy your fat hogs, dressed or alive, wheat, corn, furs, hides, or whiskey by the barrel. They sold merchandise on a January to January credit, and carried twelve hundred accounts. Almost all the cash received was from the sale of produce at New Orleans once a year. [33]

Thus, rather than being an isolated frontier area, the region had access to national markets, and took part in the national economy.

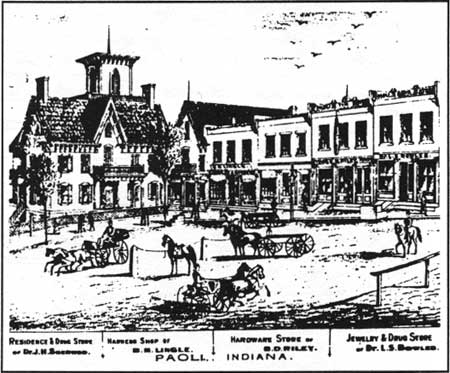

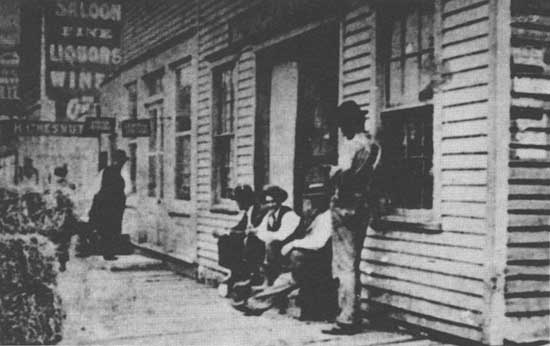

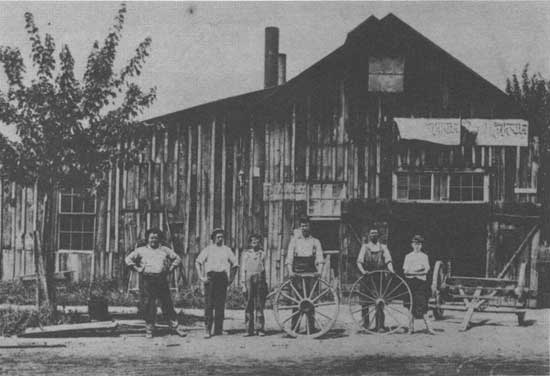

Economic endeavors in the region other than farming included milling (horse mills and water mills were both used, for grist [grain], and lumber); store keeping and inn keeping; blacksmithing; distilling; and tanning. Eventually towns and smaller rural communities dotted the landscape, providing these kinds of establishments for the rural populace.

It appears that some types of manufacturing began early in our region. Salt making was among the earliest; in Monroe County, for example, salt works date to the 1820s. The beginnings of sandstone quarrying and whetstone production occurred well before 1850, at least in Orange and Martin counties. Locally made whetstones, used for sharpening tools, were of high quality, and were exported to international markets. Another early enterprise was iron-making. An iron furnace is reported to have been operating in Vallonia, in Jackson County, in 1813. In Monroe County, an iron mine and furnace began operating in 1839. Pig iron bars were shipped out to Vincennes and Louisville in wagons, and cast-iron goods for domestic and farming use were produced for local sale. [34]

|

| Figure 18: A page from the 1837 daybook of the Stout's Mill, Paoli, illustrates some of the range of goods bought (cloth, screws, slate, steel yard scale, shirting, glass knobs, locks, back saw, calico, muslin, set of plates, and a cruet and mustard set). Stout's Mill also served for a period as a bank and a wool carding operation, as well as providing milling services. Another preserved daybook, from the H. M. Barbee store in 1845, lists goods brought in by local residents (hides, feathers, linen, tallow, eggs, butter, meat, and wood) to trade for goods available at the store (such as whiskey, sugar, spices, oil, tobacco, coffee, tea, shoes, cloth, yam, and spelling books). |

Social Patterns, Religion, and Education

The family was the core of pioneer society, with men, women, and children often traveling together to the newly acquired lands. Extended family ties, as well as relationships within the immediate or nuclear family, provided powerful social links. Often family members who had moved to our area would encourage their siblings or cousins "back home" to follow them to the Hoosier frontier. One example of this comes to us from the story of a Monroe County family, the Waldrips (we take a close look at a Waldrip family house later on). Genealogical research undertaken by family members reveals that the process of immigration occurred gradually, not all at once, with individuals moving to the area and sending word "home" to North Carolina encouraging others to make the move.

The nuclear family was also an economic unit, in which a set division of labor was determined by age and particularly gender. Children had chores, but there were also many children per family to spread out the work. Boys usually handled tasks that helped their fathers, and girls often worked together and with their mothers. Family groups came together and interacted with each other during cooperative activities such as house-building and other work gatherings; clearly, these occasions had both economic and social functions.

|

| Figure 19: The land for the Hickory Grove Church in Lawrence County was deeded in 1885, and the building was probably constructed shortly thereafter in a manner typical of early log churches. |

Churches were among the first group associations organized in the region. The church congregation was a focus of social activity as well as religious worship. The earliest church meetings took place in private homes, until separate church buildings were constructed. Churches were also important in pioneer education. Church buildings were often used for schools, and Bibles for teaching children to read, until public education was regularized in Indiana. A wide range of Christian denominations was present in our region during the pioneer years. Methodists and Baptists were most common, but Catholic, Lutheran, Presbyterian, Society of Friends, and African Episcopal Methodist organizations also existed. [35]

Religious life in the region during this period was marked by camp revivals, as well as regular church activities. Revivals were a common occurrence in the United States during the period. In rural areas they served as a unifying social force as well as providing spiritually uplifting occasions; apparently commercial activities were associated with the meetings as well. There are mentions of revivals in the Hoosier National Forest area in the county histories.

Schools, as well as churches, were established early but sporadically in each of the Hoosier National Forest counties. One provision of the Ordinance of 1785, which organized the survey and sale of lands in the Northwest Territory, was that the proceeds from the sale of one section of land (Section 16) in each township were to be set aside for the support of public education. Additionally, the first Indiana constitution, of 1816, stipulated that the state government create a free and open public education system for the state. However, the fulfillment of these constitutionally set goals was delayed by government inaction. The early schools tended to be small and irregularly attended, and were not always staffed by competent teachers. Also, pioneer period schools were not open equally to all students, and the education they offered was not free. Though it was not until much later in the 19th century that education in Indiana became more available and professionally conducted, the literacy figures for 1840 show that less than 15 percent of the children (ages 5 to 15) were unable to read and write. [36]

Social and political culture were closely mixed in the early period of European American settlement. The county histories give accounts of early county and township organization; these tend to give the impression that forming governments in the new counties was similar to forming a new club, charitable organization, or neighborhood association today. The few weekly newspapers in the region helped provide communication, commonly telling of political, social, and economic events, and advertised goods and services.

|

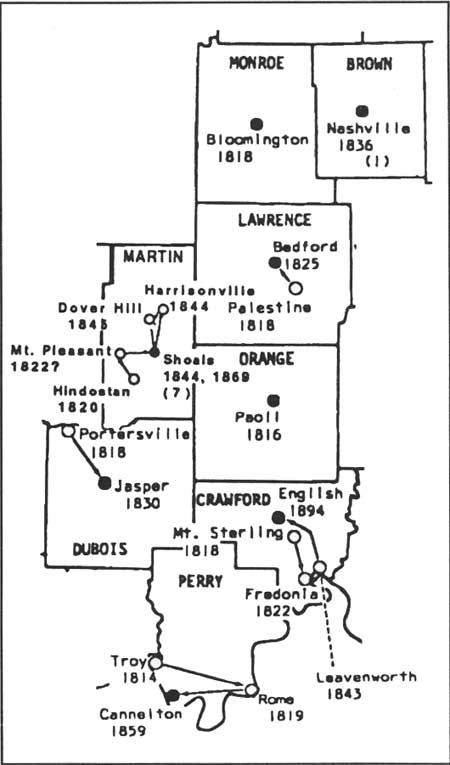

| Figure 20: Dates of organization of counties and county seats. In several of our counties, the county seat shifted as the distribution of population changed. |

Maintaining law and order was an important priority for the settlers. [37] The personal style of government may have contributed to the generally lawful behavior of the residents, by bringing a strong social element to the legal restrictions. Social, economic, legal, and political interactions were all relatively personal in nature. Pioneer society appears to have operated in almost all ways on an intimate basis.

|

| Figure 21: Early newspapers, such as those in Paoli, often reprinted articles from other newspapers and brought information on national and international events to the people of the region. These early papers also carried advertisements for locally available goods. Left: The Patriot, July 16, 1846; upper right: The Torch Light, November 24, 1838; lower right: The True American, December 18, 1841. |

Health

Most pioneers in the early years of the 1800s did not have access to professional health care, and relied on their own and their neighbors' knowledge to survive disease, injury, and childbirth. In particular, death in infancy or early childhood--often to diseases easily treated today--touched many families. Reports suggest that fevers, usually unspecified, sometimes called "ague" (malaria), were commonplace in the newly settled land, particularly in the fall. Residents of the frontier towns were at least as vulnerable as isolated settlers, for epidemics of diseases such as typhoid or diphtheria could spread in more densely populated areas and could devastate entire communities. Hindostan, the town noted for the processing and shipping of whetstones and the original county seat in Martin County, was swept by such an epidemic (perhaps cholera) in the mid-1820s. The result was that the town was abandoned and the county seat moved to another location. The same happened to Palestine, the original county seat of Lawrence County. [38]

Population Composition

While it is clear that Upland Southerners comprised the majority of pioneer settlers, and contributed significantly to the popular culture, several other groups were present in the region as well. We discuss three of these groups here--settlers from the northeastern U.S., European-born, German-speaking settlers, and African Americans--but our region was home to other groups, too, including French, English, and Russian immigrants.

Yankee Settlers

The northeastern "Yankees" came from a different cultural setting than did the Upland Southerners. The significance of the differences between these two groups, and the importance of their combined presence in the midwestern states, have been explored or noted in different historic accounts. The contrasting images of the two groups are almost stereotypic: the Yankees are portrayed as literate, industrious, and interfering, while the Upland Southerners are seen as unschooled, content to merely get by, and satisfied to mind their own business. [39]

This division is so sharply defined that one is tempted to ask whether the small percentage of settlers from the northeast contributed beyond their numbers to the economic and cultural vitality of our region. Certainly there are isolated mentions in the county histories of successful businesses run by Yankees. One 19th century county historian has written, concerning the early settlers of Brown County, that "a sprinkling of Yankees were among [the predominately southern settlers]--enough to give the Northern spirit to all public undertakings". [40] A neglected area of historical research in our region is the various roles the different cultural groups had in economic, social, and political life.

According to reports, Yankee settlers preferred to group themselves in communities with others from the Northeast. Whether Yankee immigrants had separate settlements in our region is not yet known, but architectural clues indicate that many New Englanders settled among Upland Southerners. This question might be answered by a study of census data and land transaction documents.

German Settlers

Germans were apparently the largest group of immigrants from Europe. Indeed, by 1850 half of all European immigrants to Indiana were German, or German-speaking Swiss and Austrians. Not all the Germanic settlers in the Hoosier National Forest region immigrated directly to the area from Europe. Individual and family biographies indicate that some German-born settlers lived, or stopped briefly, in other U.S. locations (such as Kentucky, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) before settling in Indiana. [41]

As with the settlers from the Upland South, the Germans came seeking a better life. Their commitment to this prospect had to be firm, for the crossing to this country was long and sometimes dangerous. One early German immigrant to Dubois County, while writing to his wife who was still in Europe, described an incident from his sea journey of 64 days:

Then we had a big storm with violent thunder and lightning ... Terriblel General confusion and misery reigned on board. It was horrible. Everyone thought that the last hour had come.... Imagine between heaven and water a ship full of shaking people tossed around like a leaf in the wind.... [42]

Despite the hardships of his crossing, he urged his wife to join him in America as soon as she could arrange it; he also suggested that others among their relations and friends consider the move. This was typical of the process by which German communities formed in this country:

... a small number of successful German immigrants on the land would attract others--often relatives or acquaintances from their hometowns in Europe--and slowly a rural cluster would develop, usually intermixed with native-born Americans or other immigrants, but sometimes almost exclusively German. [43]

In our region, some groups of German settlers clustered together in this way in the first half of the 19th century. One such concentration was the "German Ridge" area in southern Perry County. Here, place-names are critical evidence in defining their settlement area. Such names as Plock Knob, Krausch Hill, Anspaugh Flats, and Helwig Hollow appear on maps of the area. Another area of concentration of German peoples was in northern Perry County, and is also known as "German Ridge." The lack of German place-names in this area indicates that German-speaking people were probably not the first to settle in the vicinity, or that their settlement was not as extensive, exclusive, or long-lasting, as the southern "German Ridge." Each of these areas has a "German Ridge Cemetery."

German settlers are mentioned in the late 19th century county histories, particularly in the biographical sections, but their contribution to the region is not explored fully. Mention is made of preaching in German at the German Methodist Church in Tobin Township, Perry County, in the 1830s, and it is remembered for later county churches. The Swiss Colonization Society, which founded Perry County's Tell City, created a planned community in the wilderness for Swiss and German immigrants. It is not surprising then that Tell City's town records were originally kept in German. [44]

The highest concentration of settlers of Germanic origin in our area is in Dubois County, as is well known. In fact, according to the 1850 census, Dubois County had one of the highest percentages of foreign-born residents of all counties in the state, almost all of whom were immigrants from Germany. Though they began arriving before 1850, Germans were not the first settlers in the county. They were encouraged by the German Catholic church and various publications to come to Dubois County and buy land that was still available from the government, and they settled amongst already existing farms. It appears that these German immigrants were hospitably received by the earlier settlers, who taught them ways to cope with their new environment. Also, records indicate that German settlers were active in Dubois County politics. [45]

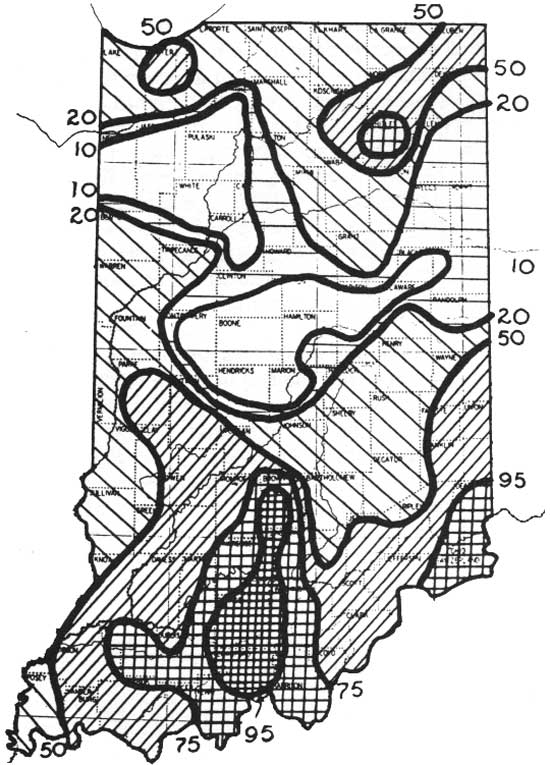

African American Settlers

The last group to be discussed, African Americans, are nearly invisible in the traditional county histories. The censuses and some of the county histories record the presence of a few blacks in Hoosier National Forest counties; their scarcity in most of the counties indicates that these individuals were probably isolated from larger black communities. In the early days, some African Americans were present as slaves, despite a ban on slavery in the Northwest Territory, and later in Indiana. Other blacks recorded in early censuses were free. [46]

Some blacks, especially many from North Carolina, are known to have immigrated to Jackson and Orange counties in connection with Society of Friends groups. In contrast to their experience in other counties, it appears that these African Americans were able to establish communities of their own. [47]

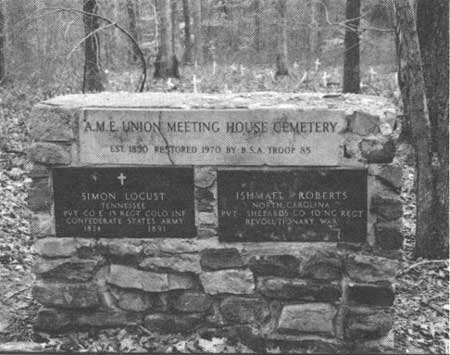

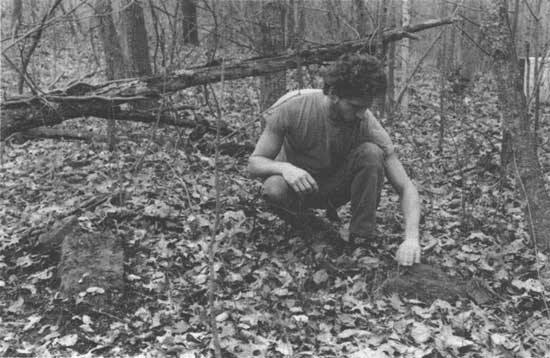

One such community of African Americans existed during the 19th century within what is now the boundary of the Hoosier National Forest. This was the Lick Creek community of Orange County. The settlement has in recent times been called "Little Africa," though this is certainly not the name the residents of Lick Creek used.

For a long time, little was known of this community, other than the bare fact of its former existence and the presence of an overgrown church cemetery in the woods south of Chambersburg. Though the graves at this cemetery date from the middle 1800s, neither a church nor the community are mentioned in the 1884 history of the county. Their omission is more an indication of the "mainstream" nature of the county histories published in the late 1800s than a reflection on the size or vitality of the community.

Over the past 20 years, private citizens, scholars, and Forest Service personnel have combined efforts in giving "Lick Creek" its place in history.

The first steps in this revival were taken in the early 1970s, when a local Boy Scout troop cleared the overgrown cemetery, reset fallen tombstones, and marked previously unmarked graves with wooden crosses. A memorial plaque was placed at the site, which is surrounded by Hoosier National Forest property. The cemetery can be visited by hiking an old road into this portion of the Forest. The cemetery is the final resting place of two veterans, Ishmael Roberts, who fought in the Revolutionary War, and Simon Locust, who was drafted from Orange County as a member of the Union Army, United States Colored Troops (Company E, 13th Infantry) in the Civil War.

|

| Figure 22: This photograph of the Lick Creek cemetery in Orange County was taken after the cemetery had been cleared and restored by local Boy Scouts. |

Documentary research has added much to our knowledge of the Lick Creek community. [48] The first black settlers in the area arrived prior to the 1820s. These first families moved from the south to Indiana to escape the increasingly restrictive laws and attitudes in their home states. Though a great majority of the Lick Creek settlers had been born free and had never been slaves in their home states, they were beginning to be legally denied many basic rights, limiting their abilities to preach, learn to read and write, own property, marry with whites, and vote.

Clearly these families had even more pressing reasons to re-settle in the new "western" states than did many of the white migrants to our region. The first black settlers were aided in their relocation by white Quaker families who had already moved into the Paoli area from North Carolina. Many of the black settlers carried certificates of freedom, sometimes known as "Freedom Papers," during their move. These were legal documents confirming their free status, signed by citizens of their former homes. These papers served as "passports," demonstrating their right to travel freely and not be seized as "runaway" slaves.

Some of the black settlers in Orange County established their own community around the area where the Lick Creek cemetery lies today. The community was not entirely exclusive--white landowners also settled within the area--and some clues exist suggesting the blacks had good relations with white neighbors. Some black youngsters under 14 years of age worked as apprentices to nearby white farmers until they reached adulthood, serving as laborers but also learning to farm. Their payment for the years of apprenticeship was a block of land, and sometimes other benefits, to be received on completion of the apprenticeship term.

We have little evidence as yet how the black families lived, what kind of houses they built, or where and how they educated their children. There was an African Methodist Episcopal church--the cemetery was associated with this church--established in the 1830s. Evidence from elsewhere suggests that the church may have been a vital center for the community, serving social, educational, and developmental needs, as well as religious functions. [49]

We will pick up the story of the Lick Creek settlement in the next section, when we look at its fate in the later part of the 1800s.

Note: Native Americans may be under-represented in early census tabulations. African Americans are listed in census tabulations as free, except as noted. European Americans include both European Americans and European immigrants. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Figure 23: African American history is a growing field of interest in southern Indiana. These figures, compiled from U.S. Census Information, show that the black pioneer population was not uniformly distributed in the Hoosier National Forest counties. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Lick Creek community may have been the only African-American pioneer community directly associated with Hoosier National Forest land, but population figures show that black pioneers were counted in all counties in our region. Though slavery was banned in Indiana, the state and the region did not generally welcome the settlement of free blacks. Crawford County, for instance, had a reputation of discouraging black settlers; it was an "unwritten law" that they were not allowed in the county, even temporarily. [50]

We have seen that our region attracted great numbers of immigrants from a variety of locations and cultural backgrounds. Often the process that brought them here was the same, even if the people were different: a small number of settlers would come to the new land and, if they found it suitable, would urge their kinsfolk, neighbors, and friends from their old home to join them. Much of what we have learned about the culture history of pioneer settlers dispels the popular romantic view that these people were self-sacrificing trail-blazers. One of Indiana's foremost historians, James Madison, tells us:

... most newcomers to Indiana acted out of no sense of uncommon valor or grand purpose. Their objectives were simpler and more straightforward--to create a slightly better life than the one that seemed possible in Virginia or Pennsylvania or Kentucky. And their methods were not heroic but quite commonsensical. They did what they had to do in that time and place to create a better life. Mostly they performed hard but repetitive and simple chores.... Their own feelings about such chores and about pioneer life were not romantic, not even accepting. For the pioneers' most important reaction to their frontier condition was not to preserve it but to attempt to change it, to move as soon as possible beyond log cabin, ax, and spinning wheel. [51]

|

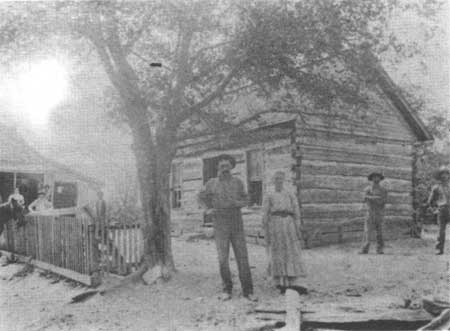

| Figure 24: Deckard family log house, built around the 1820s by "Quiet" John Deckard. This photo was taken after a later addition to the house had been removed, and so shows the original form of the house. |

Material Culture in the Pioneer Period

There are many sources in discovering what kinds of material goods were used or made by the early settlers in southern Indiana. Written accounts from the period, folklore studies of house forms and tool types, and comparison with other regions with similar lifestyles are all helpful. From these we know that the rifle, the ax, and the "spider"--an iron skillet with legs--were the essential material items brought in.

Material culture is much more than basic equipment, however. The study of material culture also takes into account the context of items: what place did these objects have in the lives of the people who made, bought, or used them? One potential source of knowledge about the context of material culture is the study of actual remains from living and working sites dating to the early 1800s. Unfortunately, other than cemeteries, very few historic sites in our region have been positively dated to the pioneer period. As more homestead and farmstead sites are discovered and then studied, archaeologists should be able to fill in information about the life contexts of material artifacts of the pioneer era.

Using the variety of sources currently available, in this section we review several forms of material culture, including houses and other buildings, cemeteries, and roads. Together, their placement on the landscape comprises the "settlement pattern," which we also discuss.

|

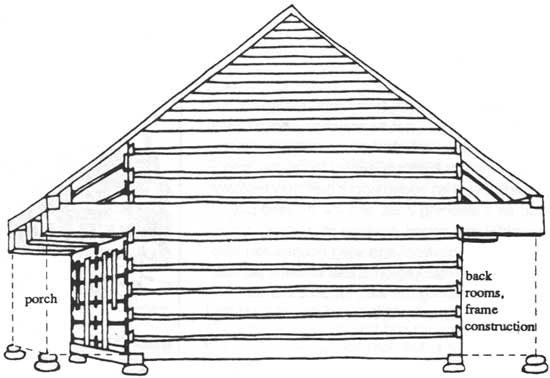

| Figure 25: The Midland log house form. These drawings show some of the variations and additions which were common to this folk house form. |

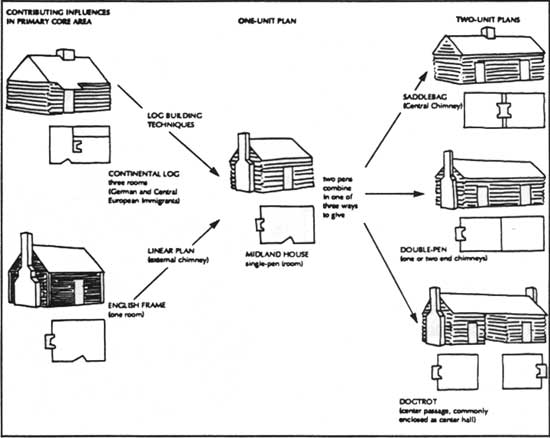

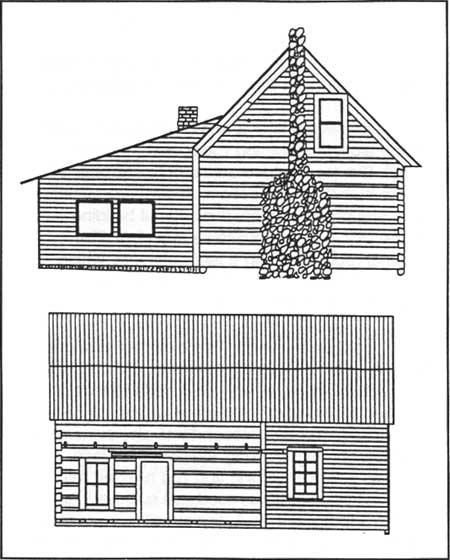

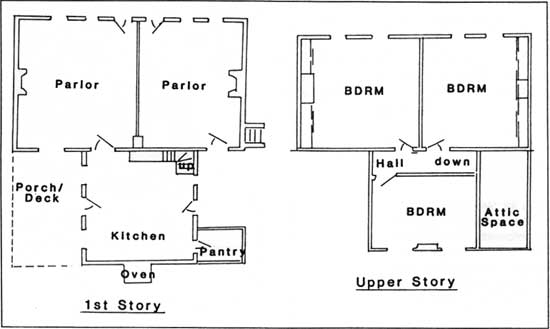

Houses

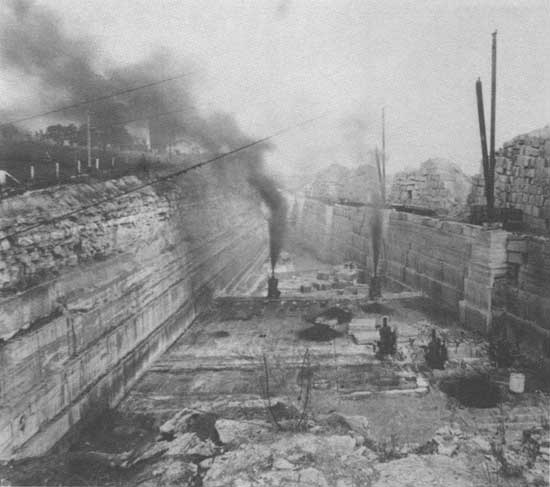

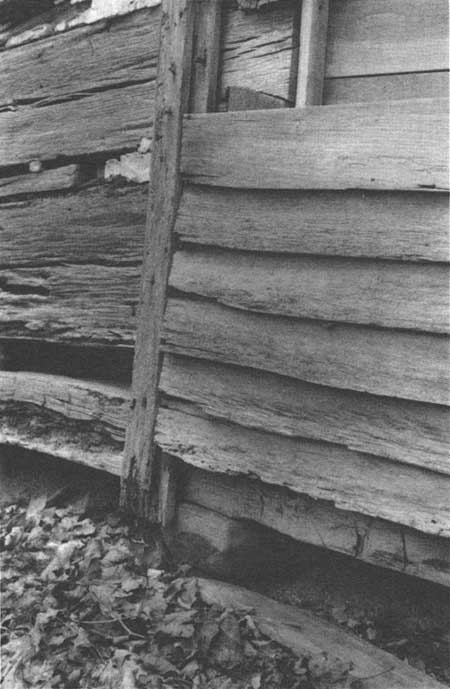

While some of the very earliest shelters used by the pioneer settlers were temporary lean-tos or cabins, the majority of pioneer settlers in south central Indiana lived in houses. We may think of their small houses as "cabins," but they were family residences, solidly constructed out of logs. Written sources from the early 1800s suggest that the residents distinguished between temporary, round-log "cabins" and more solidly built, squared-log "houses." British and Germanic influences were combined to produce the simple, rapidly built Midland Tradition log house, which originated along the Atlantic Seaboard states and then became the dominant folk house type for the interior, southern portion of the eastern United States before 1860. [52]

The form of the Midland log house was simple: the basic construction unit consisted of a "pen," or room-sized rectangular unit measuring around 16 to 20 feet on a side. The pen could stand on its own, or be joined with another pen in various ways. The single-pen type was the simplest form of the Midland log house, and represents the "classic" one-room, early frontier home. Variations employing two pens include saddlebag, double-pen, and dogtrot houses. The pens were constructed of squared "hewn" timbers stacked into walls that were joined at flush corners with notches. The use of roughly finished timber was suited to pioneer building conditions. Mud and rock chinking was used to fill the spaces between the logs.

Initially, these houses were not necessarily covered by exterior, overlapping "weather-boards"; the timber walls themselves had to resist the elements, and thus were tightly constructed. As sawmills became more common locally and cut lumber became more widely available, these houses could be more easily covered with protective weather-boards, to seal them better. Such siding also served a stylistic purpose. Local sawmills also allowed for framed additions and porches constructed from cut lumber rather than hand-hewn logs. Some scholars believe that even the earliest log houses were built with the intention of covering them immediately with boards or shingles. In such houses, the timbers for the walls could be more roughly hewn, as they were not required to be as weather-proof. [53] An example of uncovered log construction is the Waldrip house, discussed and illustrated later; an old photograph of this house shows one section built of bare logs, while the adjoining section is frame-built and covered by weather-boards.

Midland log houses had simple pitched roofs, featuring a long central ridge with front and back roof sections sloping down to the eaves. The roofs were covered by shakes (shingles hand-split made from short segments of logs), and external chimneys were placed at the gable ends of the houses. (A gable is the part of the house formed by the angle of a pitched roof).

The method of construction of log houses can be a clue to cultural affiliation, but for most of the house sites in our area, this information is no longer available, the logs having been removed or rotted long ago. One example of a log saddlebag house was still standing in the hills just north of the Hoosier National Forest until the early 1970s. This house, which was probably built around 1850, was constructed with half-dovetail corner-notching, which suggests a southern heritage. [54]

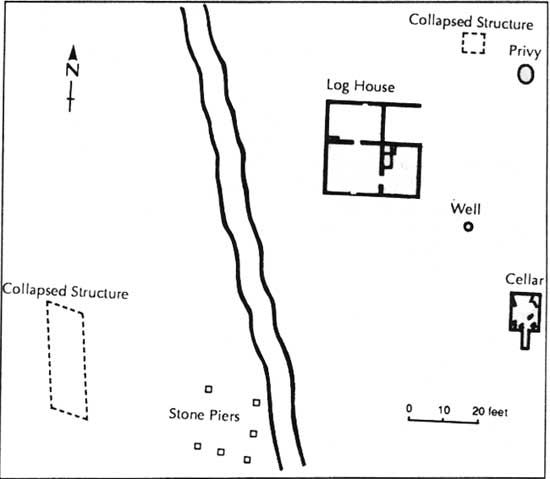

Considering that various sources tell us what to expect the typical house in the first half of the 19th century to have looked like, it may seem odd that there are no such house sites on record among the known archaeological sites in the Hoosier National Forest. Several reasons probably contribute to this situation.

1. They would have left no easily visible surface features, especially if chimneys were made out of perishable sticks, as sometimes occurred, or if more durable chimney materials were re-used on later structures. The scarcity of metal hardware or of glass for windows during early settlement also would contribute to the relatively invisible nature of such sites.

2. Early structures were often incorporated into later houses, or were dismantled and the materials re-used.

3. Later houses were built on the same sites, obscuring indications of the earlier occupation.

4. Population densities were lowest in the early years of settlement, so early sites are rarer than later house sites.

Other Structures

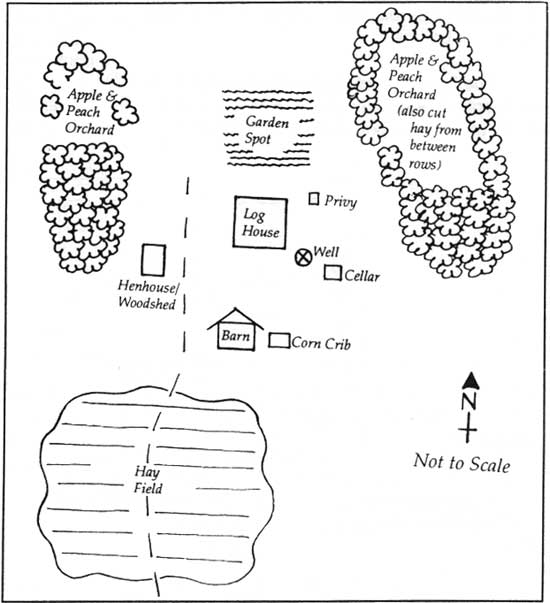

Other structures used during the pioneer era include barns and additional farm buildings, stores, government buildings, inns, churches, schools, and mills.

The earliest settlers may not have constructed extensive outbuildings, but it is reasonable to assume that by 1850 farms were becoming relatively complex. There is a tendency to picture the pioneer period in terms of isolated log houses in the woods, and to picture the later part of the 19th century in terms of full farmstead complexes complete with house, barns, sheds, root cellar, smokehouse, springhouse, cistern or wells, etc. While the isolated log house image may be valid for the beginning of the pioneer era, and the complete farmstead complex correct for the later period, these two "snapshots" in time fail to show what must be a long period of growth and development in the region. Excavation of archaeological sites is one of the best ways to learn how and when farm units gradually increased in complexity, but so far only one late historic house site in the region has had any excavation.

One type of structure that probably existed at all but the very earliest house sites was the privy. Privies are still recognizable on the landscape. In a region which did not feature underground house foundations, privies often provide one of the few "below ground" features on historic archaeological sites. The remains of privies can be an important source of information about everyday life, because when they became too full for use as latrines, the holes were often used to dispose of household trash.

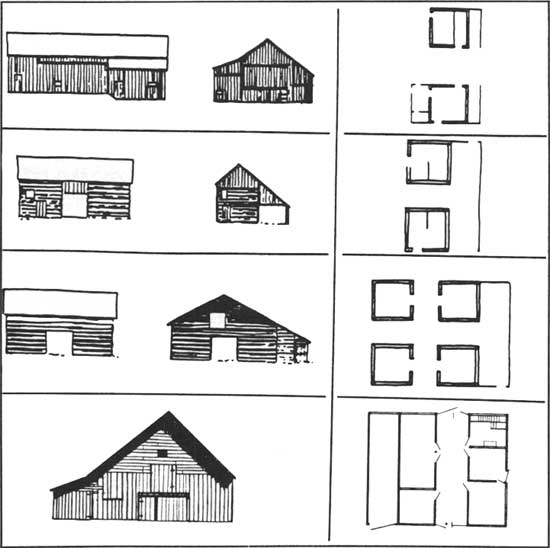

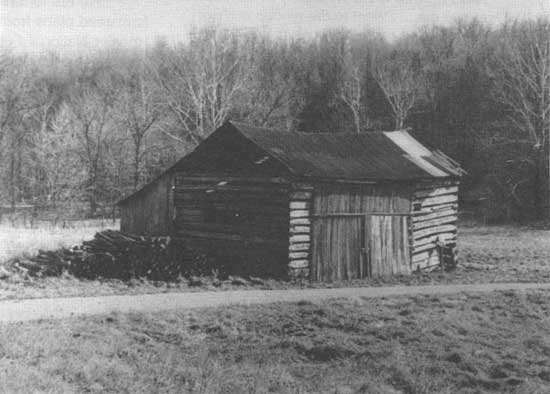

|

| Figure 26: Variation in log barns and the later, frame-built transverse-crib barn, unlike log houses, chinking was not used between the logs of barns, because ventilation was desired. |

In the Upland South core region, barns as well as houses were constructed of hewn logs. Barns were likely to have been less carefully made though, and chinking was not used because ventilation was desirable. Both single-crib and double-crib log barns are known for the Upland South. A larger log form in areas such as Tennessee and Kentucky was the four-crib barn, featuring four log pens separated by wide aisles for access and storage of equipment; the whole structure was covered by a common roof. Over time this type evolved into the frame-built transverse-crib barn, which has a single, wide central aisle with three bays on each side. In our area, the earliest barns were probably single- or double-crib log forms. Remaining examples of single-crib log barns in southern Indiana are usually surrounded by frame-built shed additions on all four sides. Double-crib log examples are also known, but no four-crib log barns have been recorded in our region. Larger barns, such as frame-built transverse-crib barns, appeared in the area as farmers began to prosper. [55]

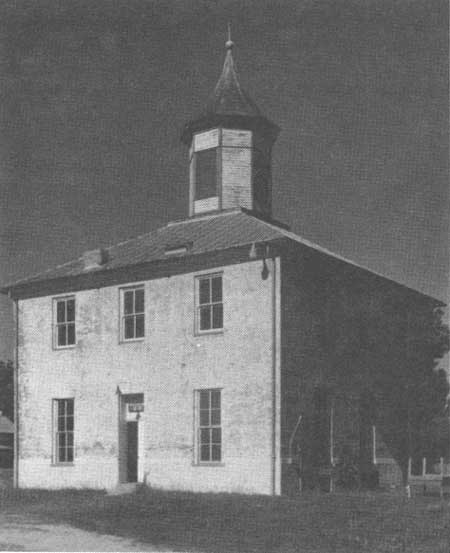

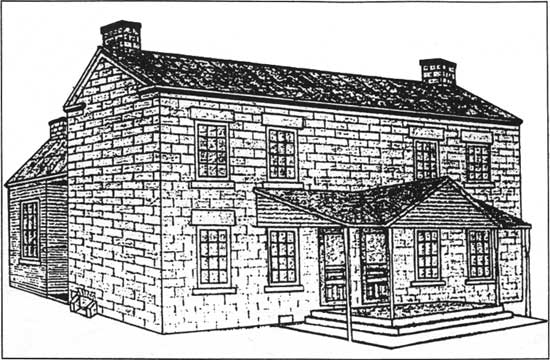

Less is known of the form of other buildings that once existed in the region. Some may have been similar, or identical, to the houses in their basic configuration. Stores, churches, schools, and businesses such as blacksmith shops and inns may have been built with similar construction plans and techniques. In fact, some buildings served multiple functions in the early years of settlement, with churches and schools operating in private homes. Government buildings were built using tax money; some of the earliest were log buildings, such as the first Monroe County courthouse, but others were grander structures, as was the case at Rome, the early Perry County seat. [56]

|

| Figure 27: Rome Court House in Perry County, built 1819-1820, is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The building was used as a school after the county seat moved to Cannelton in 1859, and it is now used as a community center. |

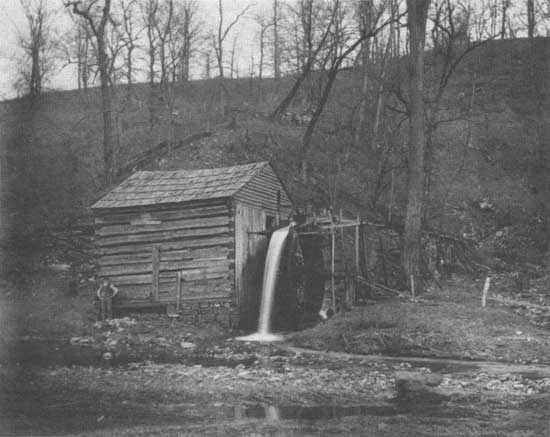

Mills were a vital economic enterprise in the pioneer days and later, even into the 1900s. We have a good description of a mill in our area, Carter's Mill in southeastern Monroe County, based on interviews with elderly residents.

... the mill was an overshot type which was spring fed into a pond on a bluff overlooking the mill.... From the pond the water flowed through a trough or chute or flume, to the top of the water wheel. The force and the weight of the water then drove the wheel forward. It could be run only one or two hours a day in dry weather, but in wet weather the old granite burrs [millstones] would take the shelled corn, oats, or wheat from the settlers from miles around. [57]

There is at least one water mill location (with some structural remains still present) on Hoosier National Forest property. This site is Carnes' Mill, on the Little Blue River in Crawford County. This unusual mill was built over a natural tunnel in the rock, with a dam over the main water stream forcing water to flow through the tunnel to provide the power to turn the mill stone. We do not yet know when this mill was built. It was operated by John Carnes, who was born in 1826 and who was active in business in our region from the 1840s into this century. He ran a post office from the mill location in the later 1800s, and had a store and a flatboat enterprise in Leavenworth. The Carnes' Mill site is being studied by the Forest Service and holds the promise of providing information on the important economic function of milling in the 1800s. [58]

Another mill site in our region is at Spring Mill State Park, where log homes and shops and a working grist mill have been restored or reconstructed at a Lawrence County settlement established in 1815. [59]

To close this section on early building, we quote Warren Roberts, a leading scholar of material culture in our region:

Those log buildings that were built in southern Indiana in the nineteenth century are a valuable testimony to a vanished way of life. They were built at a time when careful hand craftsmanship and cooperative labor were parts of daily life. The buildings survive into an era when neither is common. It is not surprising, therefore, that these log structures excite wonder, admiration and affection today. [60]

|

| Figure 28: Billy Carter mill (no longer standing) was located near the former settlement of Buena vista, Monroe County, and was powered by water from a spring above Little Indian Creek. |

Cemeteries

Small cemeteries are common in our region. As few systematic studies of cemeteries or grave markers in our region have been undertaken, it is difficult to generalize about the cemeteries of the pioneer era. [61] However, the location of these cemeteries, as well as information gleaned from their grave markers, can be used to help gain a better understanding of the period.

Traditional Upland South cemeteries were usually placed on high ground, and were often begun as family plots and later expanded; some were associated with churches. The graves at these cemeteries were not generally placed in regular rows, though they often faced toward the east. We do not know whether any of the cemeteries in and around the Hoosier National Forest show evidence for special grave-tending practices which are known to be associated with Upland South cemeteries, but most are located on prominent ridges and the headstones often show clusters of family names. And, as in the Upland South, annual "homecomings" or family reunions were held in small cemeteries associated with a particular family; such homecomings continue today. [62]

Many of the small cemeteries in our region were once associated with churches, and can serve as indications of former church locations if these are not otherwise known. Others were probably family cemeteries not connected with a church. The locations and affiliations of cemeteries can be useful in reconstructing rural social networks, if this information is used in conjunction with documentary records. The gravestones themselves are cultural artifacts: they offer evidence of cultural connections and economic or social status in their styles, forms, and materials, and also provide clues to family size, health, and marriage patterns in their inscriptions.

|

| Figure 29: Tombstones in a now abandoned cemetery in Perry County tell about life, death, and social status. The example on the left is hand-carved (Sarah J. Grant, 1860-1899), while the one on the right is commercially produced (Ella C. Grant, 1887-1891). |

Transportation

Transportation routes are important historic cultural features, but their locations can be elusive. In most cases, it is not the road (or trail) itself which is important, but the places that it connects, and the ease of travel along it. Identification of historic roads on the landscape is not easy. If roads consisted of cleared pathways, or were lain with timber logs or planks but not paved, their impression on the landscape probably will be transitory once they are abandoned. Alternatively, if such roadways continue to be used into later periods, they are generally improved, so evidence of their age will be indirect, such as through the associated presence of older sites or structures. Documentary evidence--maps or survey descriptions--can be vital in determining former road locations, but map sources generally show only principal routes. Clues to the presence of old roads could be supported by the presence of physical features, including bridge footers or abutments at stream crossings.

Some of our region's important early transportation routes are known. One is the previously mentioned Buffalo or Vincennes Trace, a wide path that went from the Falls of the Ohio to Vincennes. Settlers and travelers used the route extensively in the early historic era when it was the principal means of crossing southern Indiana. State Highway 56 and U.S. Highway 150 run roughly parallel to the trail along some stretches.

Another early historic road which passed through the Hoosier National Forest region was Kibbey's Road, or the Cincinnati Trace, which was laid out around 1800 and went from Cincinnati, to French Lick in our area, and on to Vincennes. A Cincinnati newspaper account of the making of this road shows how rugged the landscape was for the earliest travelers and settlers:

Captain E. Kibbey, who some time since undertook to cut a road from Vincennes to this place, returned on Monday, reduced to a perfect skeleton. He had cut the road 70 miles, when, by some means, he was separated from his men. After hunting them some days without success, he steered his course this way. He had undergone great hardships and was obliged to subsist upon roots, etc., which he picked up in the woods. [63]

A half-mile portion of an old trail on Forest Service property in Martin County has been identified tentatively as a segment of Kibbey's Road. [64]

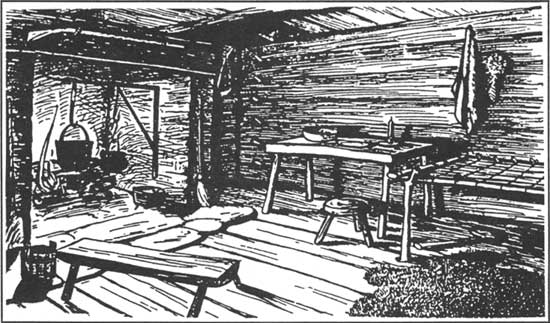

|

| Figure 30: Drawing ot the interior of a log house showing hand-made wooden furnishings (bed, table, three-legged stool, bench, and bucket) and iron kettles and "spider" (skillet on legs). |

Household Goods and Tools

It is difficult to locate household goods and tools dating from the pioneer era. For the very early years of historic settlement, it would appear that durable examples of material culture were rare. The early pioneers came to Indiana with few goods and probably took good care of those they possessed. The basic tools--axes, knives, iron cooking ware, and rifles--were essential to survival and difficult to replace. With these tools, many other utensils and goods--such as clothing, bedding, buckets, looms, kitchen and dining utensils, saddles, harnesses, and wagons--were fashioned out of wood, cloth, leather, and other perishable materials. [65] These would be unlikely to last into the 20th century, unless preserved carefully.

Over time, as settlement expanded and manufactured goods became more readily available, the types and varieties of material goods possessed by families in the region probably increased. A general national trend toward the use of manufactured goods may have been offset in the region by the cultural conservatism and the self-sufficiency associated with Upland Southerners. [66]

Articles such as window glass, ceramic and glass house wares, and even nails, horseshoes, and wagon wheels, were probably rare early on, but it is likely that by 1830 or so at least some households would have grown enough beyond the subsistence phase of settlement to acquire greater numbers of these "bought" goods. Also, some ceramic goods began to be produced within the region, with the opening of stoneware potteries in the middle 1800s. [67]

Settlement Pattern

The "settlement pattern" of a culture consists of the way in which houses, barns, churches, mills, stores, cemeteries, and roads are placed on the landscape in relation to each other and to natural features such as ridge tops, flood plains, springs, and streams. As the preceding account of the cultural settlement components must indicate, we are just beginning to collect the information needed to reliably reconstruct a settlement pattern for the pioneer era in south central Indiana. What is known about housing, material goods, and social and economic change suggests that the period should be divided into two sections, the early pioneer and the late pioneer phases, in order to examine developmental trends. As well as taking note of time variations, settlement pattern studies need to look for cultural variations between Upland Southerner, Yankee, German, and African American groups.

|

| Figure 31: An engraving from the 1870s, showing what must be an idealized portrait of rural life. Images such as this one helped to romanticize what was usually a very strenuous and demanding lifestyle. |

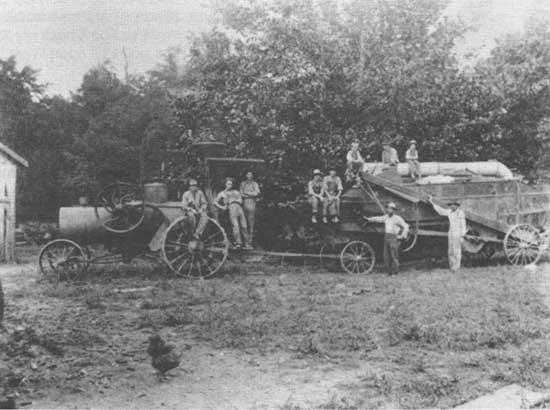

Regional Distinctiveness: Tradition and Change, 1850-1915

The period from 1850 to 1915 was one of major changes in the nation and the state, but the most significant aspect of the period for the Hoosier National Forest region was that most of these changes bypassed the region. While cities were growing and factories were being built in northern and central Indiana, in southern Indiana the lifestyle remained predominantly rural, and farming remained the principle vocation. While mechanized farm machinery was becoming the rule elsewhere in the state, south central Indiana farmers continued to rely on hand or animal powered farming tools. And, while railroads became the major form of freight transport elsewhere in the state, the steep terrain in our region made railway building difficult.

Our region thus became more isolated than other rural areas in the state. Consequently, the period is marked by a continuation of earlier modes of living, and only gradual change in the areas of economics, transportation, education, politics, and society. In overview, the region appears to have remained the same more than it changed. It is through this conservatism that south central Indiana became "an ever more distinct part of the state." [68]

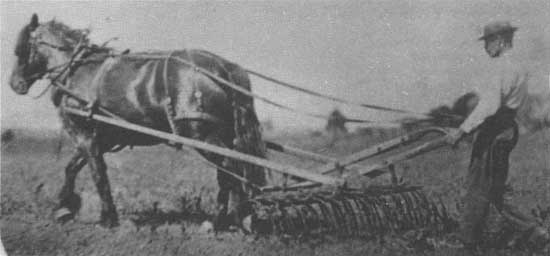

|

| Figure 32: In this photograph, taken shortly before World War I, a horse-pulled spring tooth harrow is in use. |

Economic Conditions

For much of America, the second half of the 19th century was a time of major transformation in farming technology and knowledge. Many of the improvements were not felt in the Hoosier National Forest region, for a practical reason: the rugged upland terrain was not suitable for large farm machinery. It has been suggested that the terrain was not the only reason new ways did not come into use in southern Indiana, though. Perhaps "a stronger attachment to traditional ways" may have been a factor, as James Madison suggests. This idea is in accord with the picture of the Southern Upland farmer as a conservative, self-reliant individual. [69]

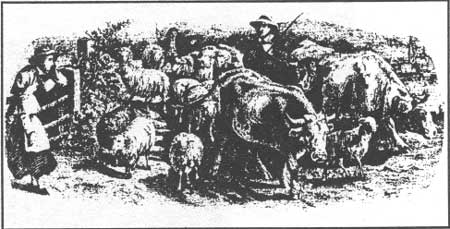

|

| Figure 33: Sorghum making, using oxen to power the extraction process, was another cooperative venture. |

Nonetheless, south central Indiana farmers were not without interest in new farming methods. As in areas of more extensive, rich farm lands elsewhere, agricultural fairs and societies were formed in the Hoosier National Forest counties during the later 1800s. County fairs represented a blending of economic and social activities; they featured displays of farm produce and home crafts, as well as mechanical equipment and manufactured goods. For the state, modern farming information was spread through publications such as The Indiana Farmer, which began printing in 1866. [70] It would be interesting to discover whether support for fairs and agricultural societies, and farm magazine readership, was differentially distributed between the various regions of the state.

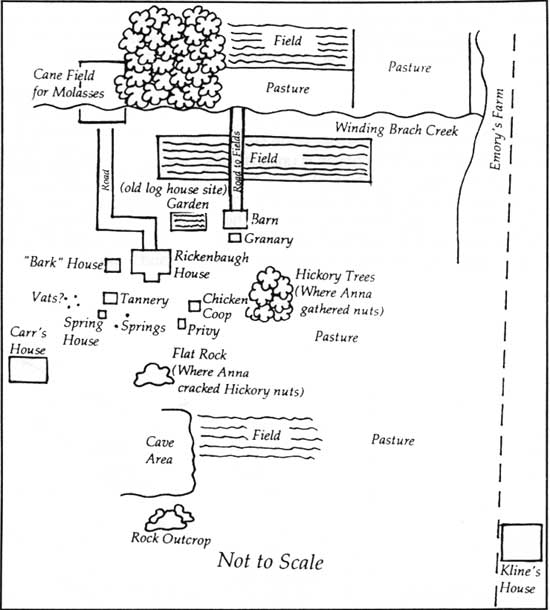

We are fortunate to have the recollections of an area resident telling what it was like to grow up on a farm in Orange County around 1900: